Abstract

Ubiquinone (Qn) functions as a mobile electron carrier in mitochondria. In humans, Q biosynthetic pathway mutations lead to Q10 deficiency, a life threatening disorder. We have used a Saccharomyces cerevisiae model of Q6 deficiency to screen for new modulators of ubiquinone biosynthesis. We generated several hypomorphic alleles of coq7/cat5 (clk-1 in Caenorhabditis elegans) encoding the penultimate enzyme in Q biosynthesis which converts 5-demethoxy Q6 (DMQ6) to 5-demethyl Q6, and screened for genes that, when overexpressed, suppressed their inability to grow on non-fermentable ethanol—implying recovery of lost mitochondrial function. Through this approach we identified Cardiolipin-specific Deacylase 1 (CLD1), a gene encoding a phospholipase A2 required for cardiolipin acyl remodeling. Interestingly, not all coq7 mutants were suppressed by Cld1p overexpression, and molecular modeling of the mutant Coq7p proteins that were suppressed showed they all contained disruptions in a hydrophobic α-helix that is predicted to mediate membrane-binding. CLD1 overexpression in the suppressible coq7 mutants restored the ratio of DMQ6 to Q6 toward wild type levels, suggesting recovery of lost Coq7p function. Identification of a spontaneous Cld1p loss-of-function mutation illustrated that Cld1p activity was required for coq7 suppression. This observation was further supported by HPLC-ESI-MS/MS profiling of monolysocardiolipin, the product of Cld1p. In summary, our results present a novel example of a lipid remodeling enzyme reversing a mitochondrial ubiquinone insufficiency by facilitating recovery of hypomorphic enzymatic function.

Introduction

Coenzyme Q, or ubiquinone (Q), is a redox-active biomolecule best known for its role as a mobile electron carrier in the mitochondrial electron transport chain (ETC). Q is comprised of a functionalized benzoquinone head group and a polyisoprenoid tail, the length of which is species-specific—ten isoprenoid units in humans (Q10), nine in Caenorhabditis elegans (Q9), and six in Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Q6). Primary Q10 deficiency manifests clinically as a collection of heterogeneous diseases that depend on the severity of Q10 loss, and include encephalomyopathy, severe infantile multisystemic disease, cerebellar ataxia, Leigh syndrome, and isolated myopathy [1–4]. Presently, disruption of nine genes has been linked to primary Q10 deficiency in humans: ADCK3/COQ and its paralog ADCK4, COQ2, COQ4, COQ6, COQ7, COQ9, PDSS1/COQ1 and PDSS2 [5, 6]. Genetic studies in mice show that complete removal of either Coq3, Coq4, Coq7 or Pdss2 results in embryonic lethality [7], and it is likely that complete loss of these genes in humans is also lethal.

Extensive work over the past two decades has shed light on the pathways involved in Q biosynthesis in cells [5]. Much of this work has exploited S. cerevisiae and there is considerable overlap with humans. Under aerobic conditions, S. cerevisiae preferentially ferments glucose to ethanol. When glucose becomes exhausted (at the diauxic shift), or when cells are cultured on a non-fermentable carbon source such as ethanol, S. cerevisiae becomes obliged to use its mitochondrial ETC machinery and hence Q production becomes essential. The ability of S. cerevisiae to shuttle between two metabolic states, coupled with the capacity to survive in either a haploid or a diploid form, has resulted in the identification of at least nine genes (COQ1 to COQ9) that are essential for the biosynthesis of Q in this species [8]. Orthologs of all nine genes are found in mammals [9]. Additional genes are also known to be involved in the manufacture of Q in S. cerevisiae: for example, a biosynthetic sub-pathway involving p-amino benzoic acid has been described [10, 11]. More genes likely await identification [5, 12].

In yeast, Q biosynthesis begins with Coq1p and Coq2p; these two enzymes co-operate to form 4-hydroxy-3-hexaprenyl benzoate (HHB). A 700 kDa ‘pre-complex’, comprised of Coq3p, Coq4p, Coq6p and Coq9p, which is bound to the inner mitochondrial membrane, next modifies the benzoate head group of HHB to form 5-demethoxy Q6 (DMQ6) [13, 14]. This compound is the penultimate intermediate in Q biosynthesis and completion of Q6 formation occurs when yeast transition toward the diauxic shift, at which point the 700 kDa pre-complex matures into a 1.3 MDa complex following the regulated recruitment of Coq7p [14, 15]. Coq7p directly binds to Coq9p [16, 17] and this event may be regulated by the Coq7p phosphatase, Ptc7p [18]. Clarke and colleagues have reported that complete removal of Coq7p in coq7 null mutants results only in HHB formation [19], while loss-of-function coq7 point mutants, such as G65D and E194K, accumulate DMQ6 [20]. This suggests that Coq7p may in fact be a constitutive component of the Q biosynthetic complex that is held in an inactive state until required. Modeling studies clearly show that Coq7p is a DMQ6 hydroxylase [21], and both modeling and experimental studies show Coq7p is a peripheral-membrane bound protein [22, 23]. Coq7p might therefore toggle between strongly- and weakly membrane-bound states which in turn determine both its final activity and its ability to be detected in the soluble 700 kDa pre-complex. Consistent with this notion, overexpression of the Coq7p kinase, Coq8p [24], stabilizes the 700kDa pre-complex in coq7 null mutants and re-permits Q6 assembly all the way to DMQ6 [14].

In the nematode C. elegans, clk-1/coq7 null mutants are unexpectedly viable [25]. Although respiration is impaired in these animals [26], and they are slow-growing and behaviorally-sluggish, more surprisingly they are long-lived [25]. Part of this ability to survive under circumstances when other species cannot is now known to be due to the ability of worms to extract Q8 from their E. coli food supply. Nonetheless, mutant clk-1 worms cultured for several generations on a bacterial food source that is unable to manufacture Q8 (GD1 E. coli) remain phenotypically long-lived [27]. Under these conditions, otherwise wild type worms also display life-extension. Expression profiling reveals that these animals elicit a transcriptional response similar to the retrograde response activated following mitochondrial ETC disruption in petite yeast, which are also long lived [28]. Moreover, clk-1 mutants reprogram their metabolism, similar to other long-lived mitochondrial electron transport chain mutants in C. elegans, including nuo-6(qm200) and isp-1(qm150)—which disrupt complex I and III, respectively [29, 30]. At least part of the clk-1 longevity response is now known to be due to a nuclear-targeted form of CLK-1 that unexpectedly binds chromatin [31].

Given the essential nature of COQ7 in humans, its centrality to Q production in cells, and its unexpected role in lifespan control of C. elegans, we sought to identify new genetic loci that could suppress the disruption of this gene in S. cerevisiae. To this end we identify the cardiolipin remodeling enzyme CardioLipin-specific Deacylase 1 (Cld1p) as a novel modulator of Coq7p activity.

Results

In an effort to identify genes that are able to overcome the essential requirement of Coq7p in yeast cultured on a non-fermentable carbon source, we transformed a coq7 null mutant (Δcoq7) with a library of genomic DNA fragments isolated from wild type yeast and contained on a high copy number vector. Transformants were directly selected for growth on ethanol (YEPE3%). We obtained no suppressors, which was unexpected since PCR confirmed that our library contained multiple copies of the wild type COQ7 locus. If Δcoq7 cells containing a bona fide copy of COQ7 were allowed to exhaust their supply of glucose prior to selection on ethanol, however, then could growth be rescued. This observation suggests that initiation of the diauxic shift in yeast is required to de-repress a genetic network permissive for COQ7 expression and activation. This idea is consistent with previous reports showing (i) Coq7p is dephosphorylated upon entry into the diauxic shift [18, 32], (ii) Q6 biosynthesis proceeds only to the level of DMQ6 prior to the diauxic shift [14], (iii) DMQ6 does not support respiration in yeast [33], and (iv) Coq7p is part of a ubiquinone-biosynthesis megacomplex, the stability of which is dependent upon full length Coq7p [14, 15]. We reasoned that many prior studies that searched for coq7 loss-of-function suppressor genes using a similar library-screening approach may have missed targets either because cultures had not been at the diauxic shift prior to transformation and selection, or because yeast cells have an absolute requirement for small amounts of Coq7p, or both. In an effort to identify novel coq7 suppressors, and to by-pass both of these potential limitations, we first generated a novel coq7 allelic series, comprised of multiple hypomorphic mutants, and then used it to undertake high-copy genomic DNA suppressor screens. We also made use of selection media comprised of non-fermentable ethanol supplemented with a small amount of dextrose (YEPE3% + 0.1% DEX.) in order to facilitate isolation of potential suppressors; our rational being that small amounts of glucose would provide a smooth transition into the diauxic shift after transformation.

Generation of a coq7 allelic series

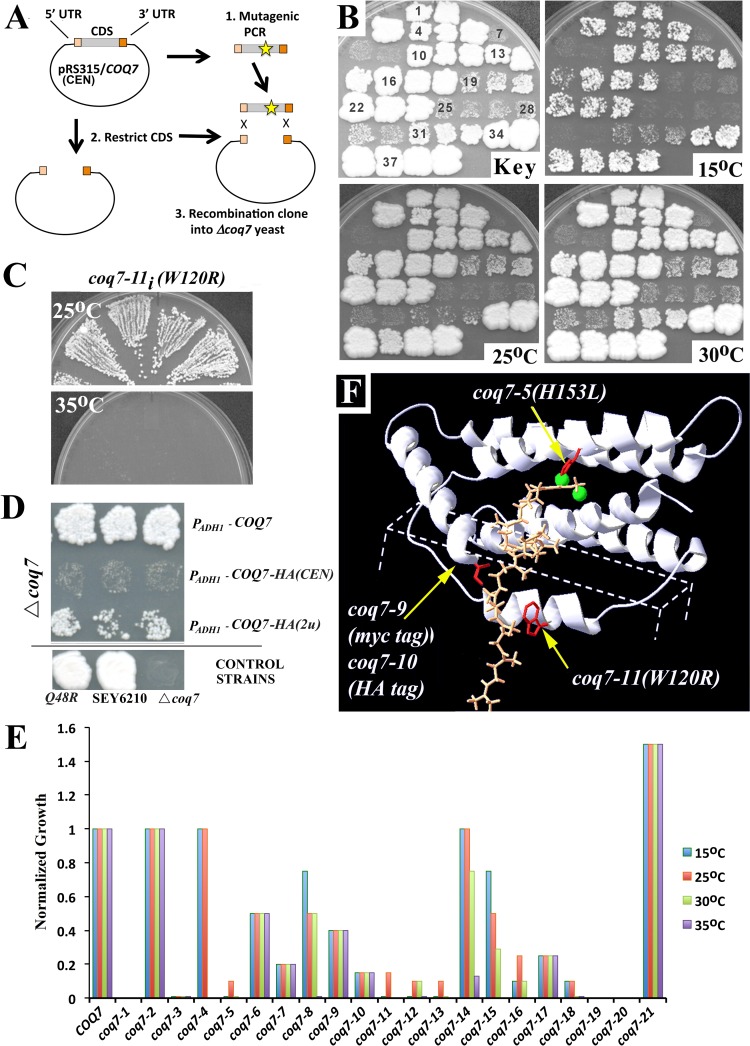

Mutagenic PCR was used to generate over seventy coq7 alleles that were hypomorphic for growth on YEPE3% (Fig 1A and 1B). All mutant alleles generated using this approach carried a Q48R point mutation that was present in the parent allele before mutagenesis. coq7-2(Q48R) yeast grow indistinguishably from wild type SEY6210 yeast between the biologically relevant temperatures of 15–35°C. We have named this allele coq7-2 to distinguish it from the COQ7 sequence of SEY6210. Alleles that were selected for further study are summarized in Table 1 and described in full in S1 Table. Most relevant are the single point mutations encoded by coq7-5(H153L) and coq7-11(W120R)—both of which severely limit growth on YEPE3% (Fig 1B) without affecting growth on 2% dextrose (YEPD2%). We re-integrated select alleles into the original COQ7 locus of SEY6210 (underlined in Table 1, and designated hereafter by subscript “i”), and found that coq7-11i(W120R) mutants displayed temperature-sensitive, hypomorphic growth (Fig 1C). During the course of our analyses we also observed that many of the epitope-tagged COQ7 alleles that have been used in prior studies [22], are also hypomorphic for growth on YEPE3% (Fig 1D). We have assigned allelic designations to some of these genes as well, since they vary in their degree of hypomorphism (Table 1 and S1 Table). Relevant to the current study is coq7-22(PADH-COQ7-HA) which, when carried on a low copy centromeric (CEN) plasmid, conferred only residual growth to coq7-19(Δcoq7) null mutants cultured on YEPE3% (Fig 1D). We also generated two new epitope-tagged coq7 alleles, coq7-9(myc tag) and coq7-10(HA tag), using the promoter, open reading frame (ORF) and terminator sequences from SEY6210 wild type COQ7, and we confirmed that the presence of a C-terminal tag alone results in hypomorphic growth on YEPE3% (Fig 1E), without disrupting growth on YEPD2%. Finally, we mapped all newly identified allelic mutations onto a previously published structural model of Coq7p [21], (Fig 1F), the reliability of which has since been supported by spectroscopic and kinetic analyses [34, 35]. coq7-5(H153L) disrupts the strictly conserved His153 residue and replaces it with a leucine. His153 chelates one of two iron atoms required for catalysis in the Coq7p active site. coq7-11(W120R) replaces the highly conserved Trp120 residue with positively charged arginine. Trp120 resides in a loop predicted to insert directly into the mitochondrial inner membrane. Trp120 also juxtaposes against the C-terminus and we have previously noted that Coq7p orthologs across multiple species all end abruptly with a bulky hydrophobic amino acid (F, I, or L) [21]. Presumably coq-7-11(W120R), as well as coq7-9(myc tag) and coq7-10(HA tag), disrupt this juxtaposition.

Fig 1. Generation and Characterization of a coq7 Hypomorphic Allelic Series.

(A) Strategy for generating mutant coq7 alleles: coq7-19(Δcoq7) yeast were transformed with a mix of PCR mutagenized coq7 constructs and then hypomorphic alleles identified by slow growth on 3% ethanol (YEPE3%). (B) Mutagenized clones were patched in triplicate, then replica plated onto YEPE3%, and monitored for growth at 15°C, 25°C and 30°C (top left panel shows patch numbering) relative to wild type SEY6210 yeast (patches #37–39). Alleles of interest are described in full in S1 Table and include: coq7-6 (patches # 13–15); coq7-11 (# 19–21); coq7-13 (# 25–27); coq7-5 (# 28–30); coq7-16 (# 31–33) and coq7-2(Q48R) (# 34–36). (C) The coq7-11 allele is temperature-sensitive and inviable at 35°C when integrated back into the wild type COQ7 locus. Shown are four independent re-integrants. (D) Addition of a HA or myc epitope tag to the C-terminus of wild type Coq7p results in hypomorphic growth on YEPE3%. Shown also is the effect of COQ7 copy number (CEN—low and 2μ- high) and promoter identity (ADH1 vs. native) on growth at 30°C YEPE3% (10 days). PADH1-COQ7-HA(CEN) was used for the library screen described in Fig 2. coq7-2(Q48R) grows indistinguishably from wild type at 30°C. (E) Relative growth rate of mutant coq7 alleles versus wild type yeast (SEY6210) cultured at four different temperatures– 15°C, 25°C, 30°C and 35°C (refer to Table 1 for allele identification, and S1 Table for raw data). Data is normalized to SEY6210 cell density at late log phase, for each respective temperature. Data for coq7-5, coq7-15 and coq7-16 at 35°C was not collected. (F) Location of relevant amino acid disruptions caused by various hypomorphic coq7 alleles (labeled). Changes affect highly conserved residues (red) and have been mapped onto a model of monomeric rat CLK-1/Coq7p [21]. Shown is the predicted position of the conserved C-terminus submerged in the mitochondrial inner membrane (dotted box), the di-iron-containing active site (green) and the DMQ6 substrate loaded into the active site (saffron). Coq7 dimerizes [35] and we have previously provided a model of dimeric rat CLK-1 [21].

Table 1. coq7 Allelic Series†.

| Allele | Key Mutations* | Other Mutations*** |

|---|---|---|

| COQ7 (wild type) | - | |

| coq7-1 | G65D | |

| coq7-2 | Q48R** | |

| coq7-3 | L198P | Q48R |

| coq7-4 | R159⦸ | Q48R, (I222V) |

| coq7-5 | H153L | Q48R |

| coq7-6 | F15L, V58A | Q48R |

| coq7-7 | Q42R, R57H | Q48R |

| coq7-8 | V55A, V111D | Q48R |

| coq7-9 | C-terminal Myc tag | |

| coq7-10 | C-terminal HA tag | |

| coq7-11 | W120R | Q48R |

| coq7-12 | W120R | Q48R, G65G (silent) |

| coq7-13 | T32S, S182P, L195P | Q48R |

| coq7-14 | V55D | Q48R |

| coq7-15 | S45P, P113S | Q48R |

| coq7-16 | V5A, R224⦸ | Q48R |

| coq7-17 | D59V, K174E | Q48R |

| coq7-18 | Q189⦸ | Q48R |

| coq7-19 | coq5Δ::GFP; HIS3 | |

| coq7-20 | coq7Δ::KanMX2 | |

| coq7-21 | E231⦸ | I91M, (C-terminal HA tag) |

| coq7-22 | PADH1-COQ7-HA | C-terminal HA tag |

| coq7-23 | PADH1-COQ7 |

† coq7-1, coq7-19 and coq7-20 are inviable on YEPE3%. coq7-3 to coq7-18, coq7-22 and coq7-23 are hypomorphic for growth on YEPE3%, while coq7-21 is a hypermorph. Refer to Fig 1E for the quantification of allele severity.

* Termination codon indicated by '⦸'. Mutant alleles that were moved back into the COQ7 locus of SEY62010 are underlined.

** Q48R mutants grow indistinguishably from wild type (from 15–35°C).

*** Mutations in brackets follow premature stop codon. See S1 Table for other silent mutations.

Identification of coq7 suppressor genes

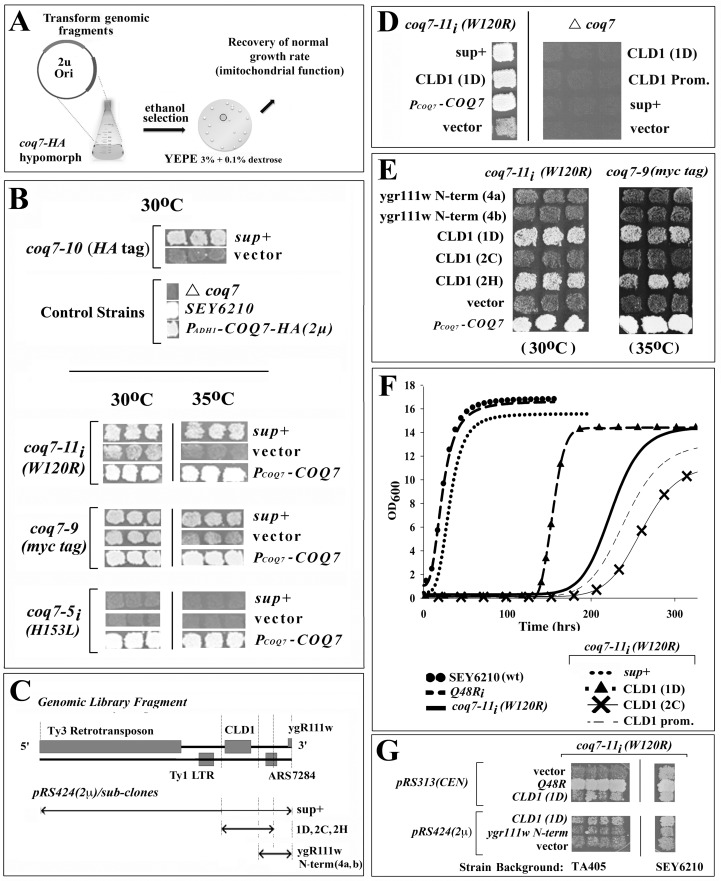

To identify new regulators of Coq7p function, we undertook a high copy suppressor screen using the severely hypomorphic coq7-22(PADH1-COQ7-HA) allele. Mutant yeast were transformed with a library of SEY6210 genomic fragments carried on a high copy number plasmid. Growth suppressors were isolated following selection on YEPE3% + 0.1% DEX. (Fig 2A). Using this approach we recovered multiple genomic fragments containing a wild type copy of COQ7—validating our screening strategy. In addition, a single library suppressor clone (sup+) was identified that, when isolated and transformed into other coq7 mutant backgrounds, conferred suppression to coq7-9[PCOQ7-COQ7-Myc (CEN)], coq7-10[PCOQ7-COQ7-HA(CEN)] and coq7-11i(W120R), but not coq7-5i(H183L) (Fig 2B). These findings confirm that suppression by this clone did not depend upon the HA epitope tag, the presence of a Q48R point mutation, or the ADH1 promoter, and was not simply due to alterations in the copy number of the plasmid upon which hypomorphic PADH1-COQ7-HA(CEN) resided. Intriguingly, this genomic suppressor restored activity to Coq7p in an allele-specific manner–specifically, only coq7 mutations predicted to affect the membrane association of Coq7p were rescued (Fig 1F).

Fig 2. CLD1 is an Allele-specific Suppressor of Hypomorphic COQ7.

(A) Schematic of genomic library screening protocol: coq7-19(Δcoq7) yeast carrying the hypomorphic coq7-22(PADH1-COQ7-HA) allele on a low copy number (CEN) plasmid were transformed with a library of genomic fragments cloned into high-copy plasmid pRS424 (2μ origin of replication). Suppressors of the ‘hypomorphic growth on 3% ethanol’ phenotype of the parent strain were then isolated. (B) One library suppressor clone (sup+) isolated conferred allele-specific suppression to coq7-9 (PCOQ7-COQ7-Myc (CEN)), coq7-10 (PCOQ7-COQ7-HA (CEN)), coq7-11i(W120R), but not coq7-5i(H183L); indicating suppression did not depend upon the HA epitope tag, the ADH1 promoter, or simply alter plasmid copy number of hypomorphic PADH1-COQ7-HA(CEN). Both the coq7-5 and coq7-11 alleles were re-integrated (subscript ‘i’) into the wild type COQ7 locus. Growth enhancement was more pronounced at 35°C for coq7-10 and coq7-11. [vector: pRS424 (2μ)] (C) Chromosomal map showing genetic landscape of library suppressor clone (sup+) and the fragment boundaries used for various plasmid constructs. 1D, 2C, 2G, 4a and 4b indicate independent PCR amplicons. (D) Growth suppression requires residual COQ7 activity to mediate enhanced growth on 3% ethanol (30°C). Strain genotype (top) and transformed plasmid identity (see panel C) are indicated. (Prom.—promoter). (E) The CLD1 locus is sufficient to confer growth enhancement on 3% ethanol to coq7-11 (30°C, left panel) and coq7-10 (35°C, right panel). Strain genotype (top) and transformed plasmid identity (refer to panel C) are indicated. (F) Quantification of coq7-11i(W120R) growth inhibition in 3% ethanol (30°C) and its suppression by overexpression of CLD1. Neither the CLD1 promoter nor the cld1 loss-of-function 2C amplicon are able to suppress the slow growth phenotype of coq7-11i(W120R). (wt, wild type). Part of the promoter of CLD1 was removed when constructing the 1D amplicon to avoid incorporation of the Ty1 LTR into the clone and we presume this is the reason we did not observe the same degree of suppression as the original library clone (sup+). Disruption of just CLD1 within the sup+ clone background did not confer any suppression (see later, main text). (G) The ability of CLD1 to suppress hypomorphic coq7-11i (W120R) is independent of strain background. TA405 [COQ7/coq7-11i(W120R)] heterozygous diploids were sporulated and four independent haploid coq7-11i(W120R) isolates retained (left). Plasmid DNA (both CEN and 2μ) containing various CLD1 derivatives were transformed into TA405[coq7-11i(W120R)] or control SEY6210[coq7-11i (W120R)] yeast (right) and then growth enhancement on 3% ethanol quantified at 30°C after 8 days.

Cld1p is a novel modulator of Coq7p function

Analysis of the genomic suppressor fragment revealed that overexpression of CardioLipin-specific Deacylase 1 (CLD1), a gene encoding a phospholipase A2 required for cardiolipin-specific acyl remodeling [36–38], was responsible for growth suppression in coq7-9[PCOQ7-COQ7-Myc (CEN)], coq7-11i(W120R), coq7-10[PCOQ7-COQ7-HA(CEN)] and coq7-22(PADH1-COQ7-HA) mutants (Fig 2D–2G, and see later). Consistent with our earlier observation that the suppressing genomic fragment was unable to rescue growth of the severe, coq7-5i(H183L) catalytic-site mutant on YEPE3% + 0.1% DEX., CLD1 overexpression was likewise unable to restore growth to coq7-19(Δcoq7) null mutants on this same media (Fig 2D, right panel). These data imply that CLD1 does not simply substitute for Coq7p activity, consistent with the different enzyme activities of the two proteins.

CLD1 suppression occurs independent of the pet56 mutation

Several yeast laboratory strains contain the his3-Δ200 mutation, including SEY6210—the parental background for our studies. The his3-Δ200 allele contains a 1036 base pair deletion that removes the entire HIS3 coding region and part of the neighboring promoter region of the PET56 gene [39]. As a consequence, PET56 expression is decreased by ~80% [40]. PET56 is responsible for formation of 2’-O-methylguanosine at position G2251 in the mitochondrial large ribosomal RNA (21S rRNA). This nucleotide sits in the peptidyl transferase center of the mitochondrial ribosome and it has been previously reported that his3-Δ200 mutants are respiration-deficient when grown at 18°C, and sluggish at 30°C [39]. TA405 yeast contain the his3-11,15 loss-of-function allele which contains two single base pair deletions and does not affect PET56 expression. We exchanged the COQ7 locus in TA405 with the coq7-11(W120R) mutant allele and observed severely retarded growth on YEPE3% which was suppressible by CLD1 overexpression (Fig 2G). These findings show that CLD1 is a bona fide suppressor of hypomorphic coq7 mutants.

Cld1p activity is required for coq7 suppression

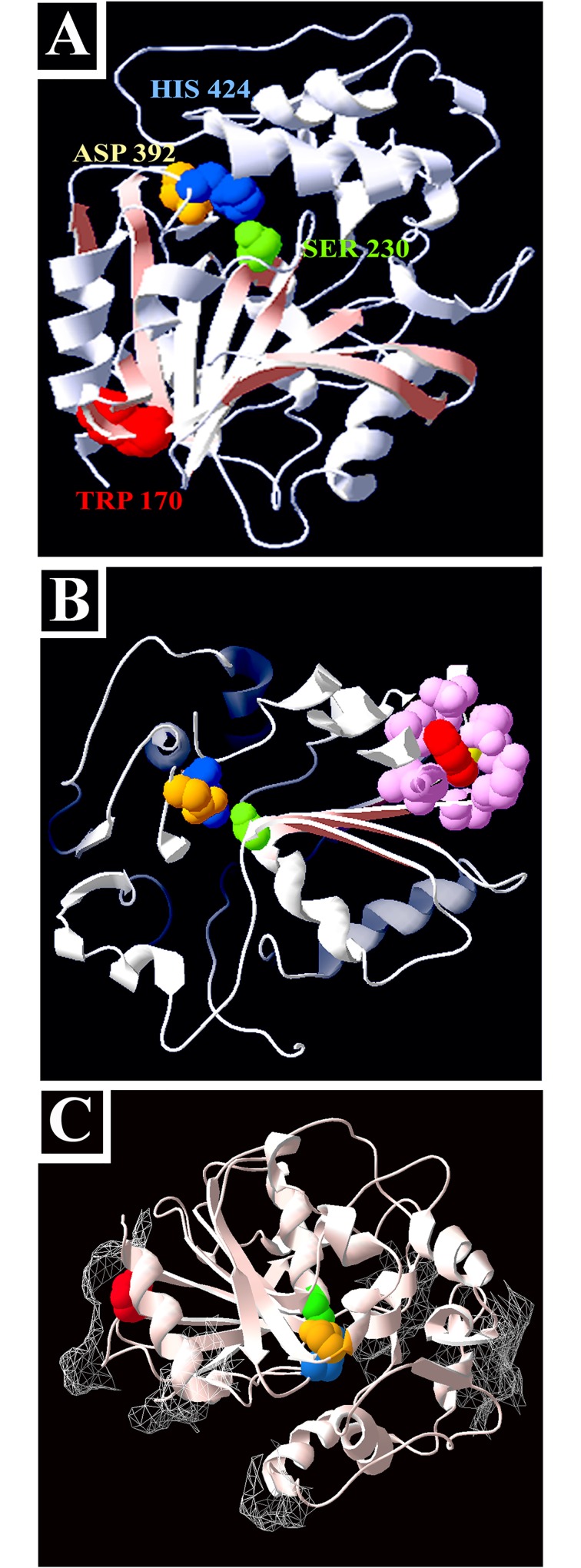

While examining the role of CLD1 in the recovery of coq7 function, we isolated a cld1 mutant that was completely blocked in its ability to rescue the growth of any hypomorphic coq7 allele (‘clone 2C’ in Fig 2E and 2F). Sequence analysis revealed a PCR-induced point mutation that converted Trp170 to arginine (W170R). It has been previously reported that Cld1p contains an α/β hydrolase fold [38]. As for other hydrolases belonging to this family, the fold acts as a scaffold to correctly position a catalytic triad of residues situated on the end of three distal loops. The α/β hydrolase family has evolved to accommodate a wide range of substrate specificities because only the triad and shape of the fold are essential to catalysis [41]. We generated a model of Cld1p based on the crystal structure of epoxide hydrolase 1 from Solanum tuberosum (Fig 3A–3C). We identified the active site residues as Ser230, Asp392 and His424. This model is in good agreement with the model constructed by Baile and colleagues [37] using the α/β hydrolase domain of CumD. These authors experimentally verified that Ser230, Asp392 and His424 were each essential for Cld1p activity. Surprisingly, Trp170 sits distal from the catalytic triad (Fig 3A), suggesting W170R must disrupt Cld1p function indirectly—possibly through destabilization of the α/β hydrolase fold (Fig 3B), or by disrupting membrane binding (Fig 3C). In regards to the latter, Cld1p is a membrane protein that faces the mitochondrial matrix [37]. Our model shows that Cld1p is surrounded by a skirt of surface-exposed hydrophobic patches, consistent with its function as a membrane lipid-modifying enzyme, and W170R sits directly below one of these regions (Fig 3C).

Fig 3. Cld1p contains an α/β hydrolase fold essential for coq7 suppression.

(A-C) Homology model of Cld1p, built using PDB structure 2CJP.A (Solanum tuberosum epoxide hydrolase 1). Highlighted features include–(A-C) the catalytic triad [Ser230 (green), Asp392 (yellow) His424 (blue)]; the W170R point mutation encoded by the non-suppressing cld1 ‘2C amplicon’ (red); (in B only) structural residues of the α/β hydrolase fold immediately surrounding Trp170 (pink); and (in C only) surface-exposed hydrophobic patches (mesh).

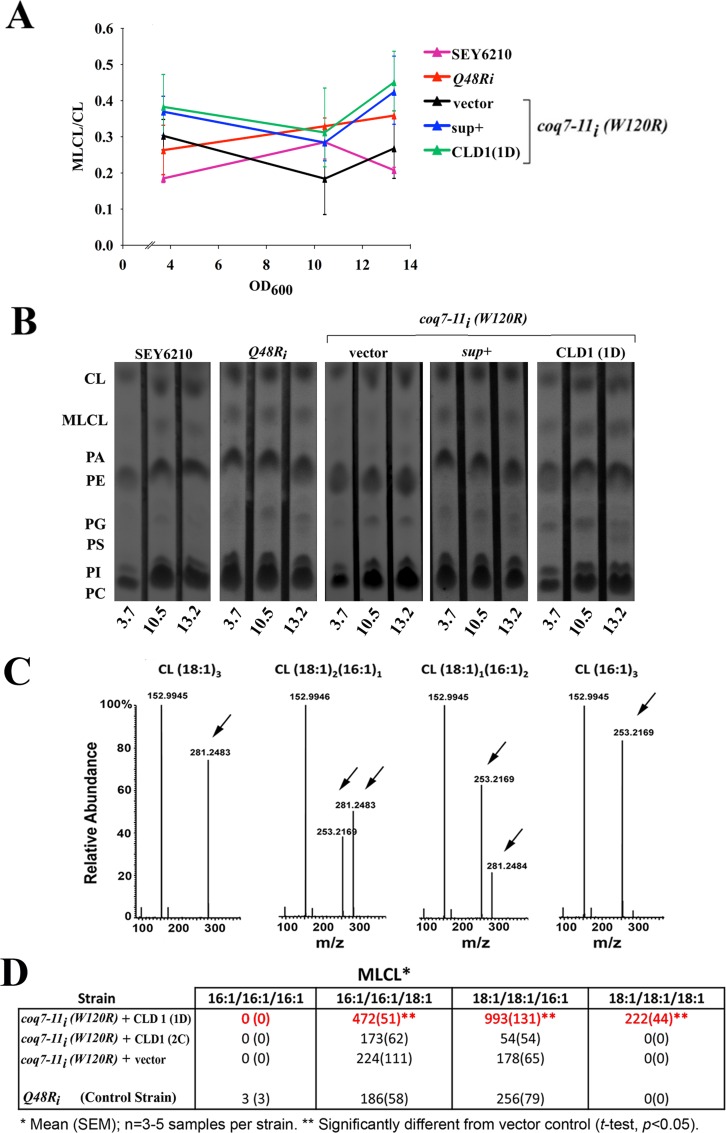

Overexpressing Cld1p re-models acyl composition of MLCL in coq7-11i(W120R) mutants

In yeast, Cld1p deacylates cardiolipin (CL) to generate monolysocardiolipin (MLCL) and this enzyme shows a preference for removing palmitic acid (C16:0) [38]. Once formed, MLCL can be re-acylated with longer (C18) unsaturated fatty acids by the Tafazzin ortholog, Taz1p [36]. When Taz1p is removed from cells MLCL accumulates to detectable levels, suggesting Cld1p is constitutively active [42]. Cld1p and Taz1p therefore work together to dynamically control cardiolipin remodeling in the mitochondria [38]. It has been previously reported that wild type cells overexpressing Cld1p display no detectable alteration in their relative ratio of MLCL to CL [38], suggesting Taz1p, and not Cld1p, is rate limiting for CL production in yeast. In contrast, when Cld1p was overexpressed in coq7-11i(W120R) cells we saw a significant increase in the relative ratio of MLCL to CL in whole-cell lipid extracts (Fig 4A and 4B, Multiple Regression Analysis, p<0.007). Cardiolipin contains four acyl chains, the composition of which influences CL functionality [43]. To examine the enzymatic activity of Cld1p further, we investigated how overexpressing Cld1p changed the acyl composition of CL in coq7-11i(W120R) cells. We used HPLC-ESI-MS/MS and focused specifically on the product of the Cld1p reaction, MLCL. Four dominant MLCL species have been previously described in S. cerevisiae [44]. We observed a marked shift in the acyl composition of the MLCL pool in coq7-11i(W120R) cells overexpressing CLD1 relative to control lines (Fig 4C and 4D). Notably, MLCL species containing C18:1 became significantly more abundant (t-test, p < 0.05). Interestingly, the appearance of MLCL(18:1)3 in these cells suggests Cld1p may have both phospholipase A2 and A1 activity, and that this enzyme might be more appropriately described as a phospholipase B [45]. In contrast, coq7-11i(W120R) cells overexpressing the cld1(W170R) mutation (‘clone 2C’) showed that the protein encoded by this allele was effectively enzymatically dead, which again emphasized the necessity of functional Cld1p for phenotypic rescue. Overall, our findings showing direct changes in the abundance of the MLCL product of the Cld1p reaction are in agreement with an earlier study that showed removal of CLD1 decreased the abundance of CL species containing unsaturated acyl chains [36].

Fig 4. CLD1 overexpression alters whole-cell monolysocardiolipin content of coq7 hypomorphs.

(A, B) Whole-cell lipid extracts were prepared from the indicated yeast strains following growth at 25°C in liquid YEPE3% to the indicated optical density (OD600). Lipids were analyzed by thin layer chromatography (TLC). In (A), average MLCL/CL ratios (+/- range) are plotted for duplicate independent experiments, with triplicate technical replicates assayed at each OD600, in each experiment. Multiple regression analysis (S2 Table) revealed a significant (p<0.007) increase in the MLCL/CL ratio in coq7-11i(W120R) yeast following overexpression of Cld1p (1D and sup+). In (B) representative, raw TLC data is shown. CL, cardiolipin; MLCL, monolysocardiolipin; PA, phosphatidic acid; PE, phosphatidylethanolamine; PG, phosphatidylglycerol; PS, phosphatidylserine; PI, phosphatidylinositol; PC, phosphatidylcholine. (C) MLCL derivatives were extracted from yeast cultured at 25°C to mid-log phase (OD600 ~7), then analyzed by HPLC-ESI-MS/MS. m/z for [M-H]- of CL(16:1/16:1/16:1), CL(16:1/16:1/18:1), CL(18:1/18:1/16:1) and CL(18:1/18:1/18:1) used for quantification are m/z 1107.6884, 1135.7196, 1163.7510 and 1191.7823, respectively. Arrows indicate C16:1 and C18:1 peaks used for MS1 identification. (D) Absolute quantitation of MLCL species in mid-log phase of the indicated yeast strains (pmole per 35ml culture volume, OD600 7.0). Data is presented as mean (+/- SEM), n = 4–5 independent replicates per strain. Significance testing was undertaken using Student’s t-test p<0.05). Overexpression of wild type CLD1 (amplicon 1D) in the coq7-11i(W120R) background leads to a shift in C18:1 enriched MLCL species. This shift was not observed when the non-suppressing cld1(W170R) point mutant (encoded by amplicon 2C) was overexpressed, suggesting this allele either directly or indirectly results in an enzymatic loss-of-function protein.

The Q6/DMQ6 ratio is normalized in coq7 mutants following CLD1 overexpression

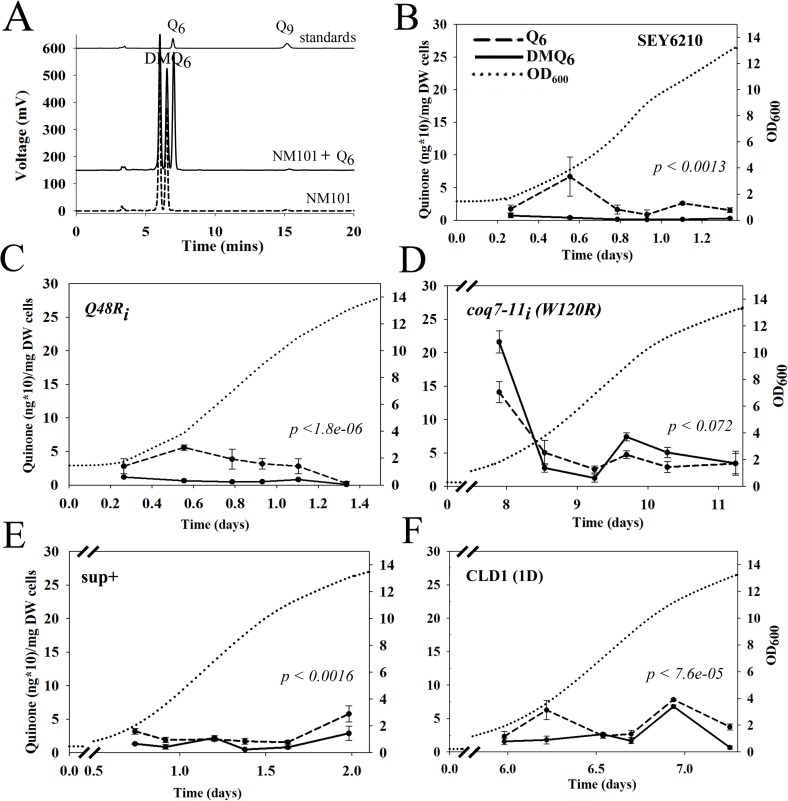

We next sought to determine how CLD1 overexpression suppressed the hypomorphic growth of mutant coq7 yeast. We observed by western analysis that hypomorphic coq7-22(PADH1-COQ7-HA) mutants overexpressing a genomic fragment containing wild type COQ7 produced less COQ7-HA protein. Overexpression of CLD1 induced the same effect, while overexpression of mutant cld1(W170R) did not (Fig 5). Q6 is known to feedback and regulate the stability of its biosynthetic complex [14], of which Coq7p is a component, so our findings suggest that CLD1 overexpression may be leading to direct recovery of Coq7p activity. We therefore quantified quinone amounts in CLD1 overexpressing cells during growth on YEPE3% + 0.1% DEX. (Fig 6A). We analyzed several strains and observed that SEY6210 (wild type) and coq7-2i(Q48R) cells both showed a burst of Q6 production shortly after entering log phase growth on ethanol (Fig 6B and 6C). We observed only small amounts of DMQ6 accumulate in both strains under these growth conditions. coq7-11i(W120R) cells exhibited a similar trend in Q6 production at the onset of log phase growth, but it was much more exaggerated in magnitude. Notably, coq7-11i(W120R) cells took 8 days to reach early log phase (25 times longer than wild type), and moreover, in contrast to the control lines, by this phase of growth DMQ6 levels were also overtly elevated in this strain (Fig 6D). Introduction of the original genomic DNA library suppressor clone (sup+) into coq7-11i(W120R) cells resulted in reversion of both the Q6 and growth phenotype toward that of the control coq7-2i(Q48R) line (Fig 6E and S3 Table). Introduction of just the CLD1 open reading frame showed partial rescue of both phenotypes (Fig 6F), and lack of full suppression was presumably because the flanking DNA control regions were not present in their entirety in this clone (Fig 2C and [37]). Together, these data strongly suggest that CLD1 overexpression overrides the predicted membrane interacting defects of hypomorphic Coq7p proteins to allow them access to their DMQ6 lipid substrate.

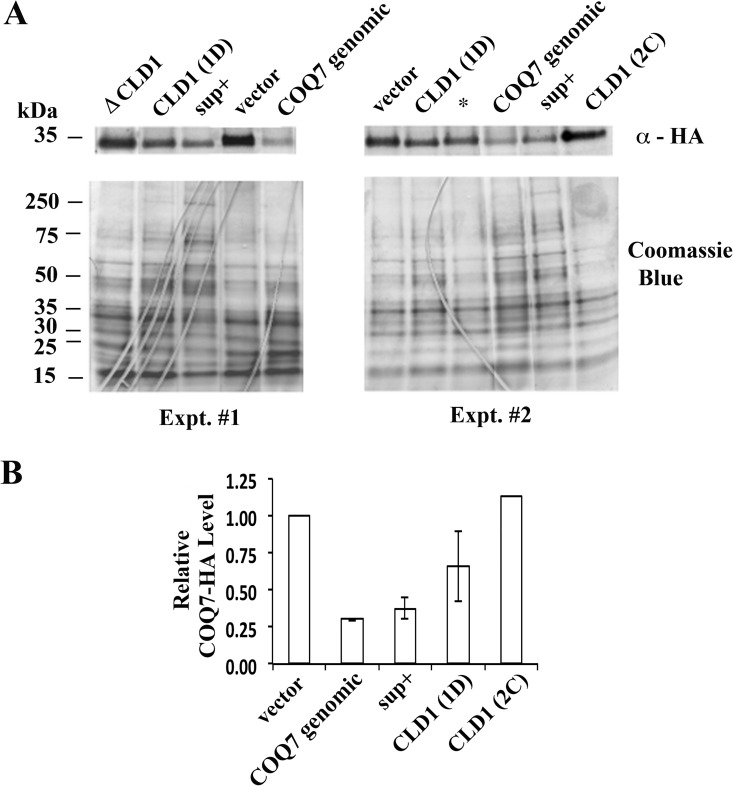

Fig 5. Effect of Cld1p over-expression on the protein level of Coq7p.

(A) A coq7 null mutant [coq7-19(coq7Δ::GFP; HIS3)] containing the hypomorphic coq7-22(PADH1-COQ7-HA) allele on a centromeric (CEN) plasmid, was transformed with the indicated genomic fragment contained on a high copy number (2-micron, 2μ) plasmid (pRS424). Cells were cultured at 25°C in YEPE3% until reaching stationary phase, then whole cell lysates collected and analyzed for Coq7p-HA expression by western analysis. Raw data from two independent experiments are shown. (B) Relevant lanes in (A) are quantified in panel B. Average and range are shown. In (A), ΔCLD1 is the original CLD1-containing genomic suppressor (sup+) library clone with the CLD1 open reading frame deleted. The asterisk in the right panel of (A) is a second library suppressor clone that was identified but which is not discussed further in this study.

Fig 6. Effect of CLD1 Overexpression on Cellular Quinone Levels.

(A) Quantitation of Q6 and DMQ6 levels in yeast whole-cell extracts using UV-HPLC. Three traces are offset on the vertical axis. Bottom trace: extract from loss-of-function NM101[coq7-1(G65D)] mutant containing DMQ6 (right peak); middle trace: extract from NM101 co-injected with Q6 standard; top trace: purified Q6 and Q9 standards. Q9 was added as an internal standard for all yeast quinone extractions. Peaks were detected using λ275nm. (B-F) UV-HPLC quantitation of Q6 (dashed line) and DMQ6 (solid line) in the indicated strains following growth in liquid YEPE3%. Quinone content is shown relative to culture density (OD600, dotted line). Broken axes highlight the temporal difference in growth rate between strains (abscissa). (E) and (F) represent coq7-11i(W120R) yeast containing the indicated construct (see Fig 2C for details). Each data point is the average of three independent biological replicates and represents total (reduced + oxidized) Q6 and DMQ6. Error bars indicate standard deviation (See S3 Table for statistical analyses). p-values indicate strength of significance for whether Q6 and DMQ6 profiles differ (significance threshold after Bonferroni correction = 0.0038)

CLD1 overexpression lengthens the replicative lifespan of coq7-11i(W120R) mutants

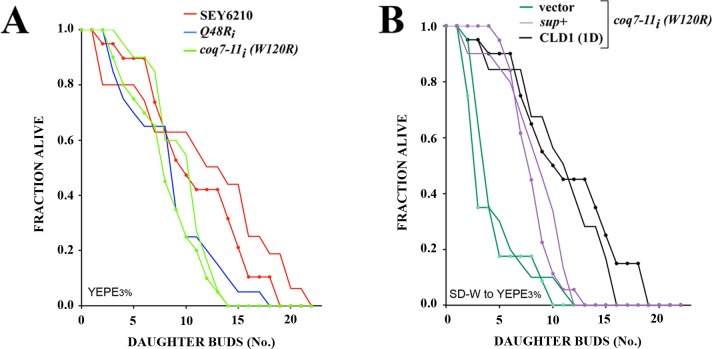

Mutations that reduce or remove clk-1/coq7 function in C. elegans result in life extension [25]. It has not been possible to determine the effect of complete coq7 removal on yeast cell survival because Coq7p is essential for growth on YEPE3%. With the identification of hypomorphic coq7 alleles we can now examine the effect of reduced coq7 function on yeast survival. We measured replicative lifespan, which monitors the ability of individual ‘mother’ cells to generate buds, and is generally considered the functional equivalent of lifespan studies in higher organisms [46]. coq7-11i(W120R) mutants showed no significant alteration in replicative lifespan when compared with coq7-2i(Q48R) cells, their relevant control (Fig 7A). Interestingly, coq7-2i(Q48R) cells, generated significantly fewer buds than SEY6210 yeast cells (Fig 7A and S4 Table). This is unexpected since, by all prior measures these two strains behaved indistinguishably (Figs 1E, 2F and 6). We next examined the effect of CLD1 overexpression on the replicative capacity of coq7-11i(W120R) cells. Under the specific assay conditions we employed (where cells were maintained on auxotrophic, plasmid-selection media immediately prior to analysis on 3% ethanol), the replicative lifespan of coq7-11i(W120R) cells was extended between 2- and 3-fold when overexpressing CLD1 (Fig 7B). These findings underscore the major finding of this work–that some forms of ubiquinone insufficiency can be fully reversed by cardiolipin remodeling in yeast.

Fig 7. CLD1 overexpression lengthens the replicative lifespan of coq7 hypomorphs.

(A, B) Replicative lifespan analyses of the indicated yeast strains cultured at 25°C on YEPE3%. Duplicate lifespan experiments for each line are provided (n = 20 virgin mother cells per strain per experiment). The following strain comparisons were significantly different (p<0.05) after pooling data across replicate experiments [mean replicative lifespan, p-value (log rank test)]. In panel (A), Q48Ri vs. SEY6210 (6.1 vs. 9.2, p<0.0009), coq7-11i(W120R) vs. SEY6210 (6.8 vs. 9.2, p<0.0008). In panel (B), vector (pRS424) vs. sup+ (2.4 vs. 6.3, p~0), vector vs. CLD1 (1D) (2.4 vs. 9.1, p~0), and CLD1 (1D) vs. sup+ (p < .002). coq7-11i(W120R) derivatives were cultured on synthetic selective media prior to transferal to YEPE3%. All other strains were maintained continuously on YEPE3%.

Discussion

In this study, we sought to identify genes that, when overexpressed, could suppress the ubiquinone insufficiency caused by hypomorphic disruption of the Q biosynthetic enzyme Coq7p. Using a newly-generated panel of coq7 mutants in the yeast S. cerevisiae, we discovered that overexpression of CLD1, encoding a cardiolipin-specific phospholipase A2 [38], was able to fully rescue the slow growing phenotype of several different coq7 mutants. We provide evidence that rescue by CLD1 overexpression is dependent on the enzymatic function of Cld1p, and requires residual Coq7 activity. We have found through structural modeling that the mutant Coq7p proteins that were suppressed by Cld1p all had mutations positioned in, or adjacent to, a predicted membrane-binding region. We therefore cautiously speculate that in the absence of Cld1p overexpression, these mutant Coq7p proteins were unable to insert into the mitochondrial inner membrane efficiently or, if they were, they were unable to adopt the correct depth or orientation in the membrane to permit DMQ6 access to the otherwise intact di-iron active site [21, 34, 35]. Consistent with this interpretation, Cld1p overexpression was incapable of suppressing the hypomorphic coq7-5(H153L) mutation which encodes a H153L lesion that directly disrupts the Coq7p catalytic site.

The most important finding of our present study is the identification of a functionally significant interaction between a cardiolipin remodeling enzyme and an enzyme of the Q biosynthetic machinery. We showed that enzymatically active Cld1p, when overexpressed, could normalize Q6 and DMQ6 levels in mutant coq7-11i(W120R) yeast. The extent and kinetics of this suppression is apparent in Fig 6: In control yeast grown in non-fermentable media (Fig 6B and 6C), Q6 levels reproducibly exhibit a spike upon entry into log-phase growth (refer to OD600 axis). A second, minor peak is also observed in SEY6210 cells just before cells reach stationary phase. This latter peak may reflect activation of a stress response as nutrients become limiting, or it may reflect a drop in Q6 levels below some critical threshold, in which case Q6 synthesis presumably becomes reactivated. In any case, in contrast to Q6 levels, DMQ6 is maintained at almost undetectable levels during the entire growth phase. The situation for hypomorphic coq7-11i(W120R) mutants is, however, very different. We recorded a remarkable elevation of both Q6 and DMQ6 in these cells as they entered log-phase growth. At first this appears counterintuitive for an allele that is obviously hypomorphic for growth. However, it is clear from Fig 6D that DMQ6 levels in this mutant almost always remain higher than those of Q6. Due to technical restrictions we were unable to collect sufficient cells to monitor earlier growth points than those shown, but we speculate that hypomorphic coq7-11i(W120R) mutants first accumulate massive amounts of DMQ6. At first, small amounts of Q6 would be synthesized by the mutant enzyme, however, once Q6 levels reach a critical threshold, cells enter log-phase and a much more rapid expansion of the mitochondrial network could then ensue. We speculate that either additional Coq7p is then synthesized, which would accelerate the conversion of the remaining DMQ6 to Q6, as observed, or perhaps Cld1p is naturally activated as part of the mitochondrial expansion, given it is a cardiolipin modifying enzyme and cardiolipin is the most abundant lipid in the mitochondria. Regardless, in the context of coq7-11i(W120R) mutants, both options would result in growth enhancement. In support of this idea we note there is a second spike in the quinone profile of coq7-11i(W120R) mutants, toward the beginning of stationary phase. Here, DMQ6 and Q6 are present in much greater amounts relative to the equivalent growth phase of controls cells; and DMQ6 levels are almost twice those of Q6. Again, this is consistent with a delay in DMQ6 processing. The original library clone containing CLD1 in its genomic context conveyed near perfect suppression of the coq7-11i(W120R) mutant in regard to its quinone profile (Fig 6E). Overexpression of the Cld1p open reading frame was also effective at suppressing the slow growth defect of coq7-11i(W120R) mutants, though with delayed temporal efficacy relative to the genomic clone (Fig 6F), likely because part of the CLD1 promoter region was removed (Fig 2 and [37]). Comparison of quinone levels between strains at various growth stages (compare OD600 axes) clearly reveals the extent to which CLD1 overexpression is able to normalize DMQ6 and Q6 levels in coq7-11i(W120R) mutants. In summary, while natural elevation of Cld1p during growth could provide a simple explanation for why CLD1 overexpression was identified in our screen, less easy to explain is how Cld1p acts to suppress hypermorphic Coq7p in order to recover enzyme functionality.

Our finding that overexpression of Cld1p did not change the MLCL/CL ratio (Fig 4A and 4B), but instead increased the average length and degree of unsaturation of the acyl chains in its enzymatic product, monolysocardiolipin (Fig 4C and 4D), suggests that a shift in the inner membrane lipid composition likely plays an important role in the rescue of hypomorphic coq7 mutants. To date, there has been no report of Coq7p directly binding either cardiolipin or MLCL. In S. cerevisiae, cardiolipin species fall into five prevalent sub-types: CL(16:1)4; CL(16:1)3(18:1)1; CL(18:1)2(16:1)2; CL(18:1)3(16:1)1 and CL (18:1)4 [44]. Even so, this amounts to 13 possible CL isomers, more when minor acyl species are included, and even more when 13C isotopomers are included; understandably the precise molecular profile of CL in yeast remains poorly uncharacterized. It has been reported, however, that by late log phase the relative abundance of C16:0, C16:1, C18:0 and C18:1 acyl groups is 30%, 30%, 5% and 35%, respectively [38]. Our MS data clearly showed that CLD1 overexpression increased the abundance of C18:1 in MLCL. We do not know if alterations to MLCL per se, or to CL were required for hypomorphic Coq7p functional recovery, but we believe the most simple interpretation of our data is that changes in the mitochondrial lipid environment allowed previously hypomorphic variants of Coq7p to assume full catalytic functionality. Phospholipids are known to provide a conducive environment for the activity of many membrane proteins by dictating their folding and assembly [47, 48]. The activity of many integral proteins is also dependent upon lipid bilayer thickness, which in turn is dependent upon acyl chain length [49, 50]. Lipid-specific binding sites on integral membrane proteins are also known [47, 51], and in this regard computational studies indicate that the side chains of hydrophobic residues such as isoleucine, leucine, valine and phenylalanine often interact with the acyl chains of phospholipids, while the more polar residues interact with lipid polar head groups and their glycerol backbones [47]. We found that the mutation in coq7-11i(W120R) replaces the highly hydrophobic tryptophan 120 residue with arginine. Since tryptophan does not generally tolerate substitution because of its structural uniqueness, in the absence of cardiolipin data, we cautiously speculate that arginine changed the hydrophobic surface of Coq7p enough to impair its interaction with the acyl chains of cardiolipin, and that Cld1p caused a compensatory change in the cardiolipin acyl profile that led to recovery of Coq7p activity in the mutant. Finally, it is possible that MLCL/CL substitution with C18:1 simply affected the thermal stability of mutant Coq7p proteins, a previous example of which is found in a site directed mutagenesis study involving interaction between a diacidic molecule of cardiolipin and the purple bacterial reaction center [48].

While alterations to the mitochondrial lipid environment that in turn directly affect Coq7p’s ability to insert into the mitochondrial inner membrane is our favored hypothesis for how CLD1 overexpression functions to suppress hypomorphic Coq7p mutants with predicted membrane-binding defects, alternate explanations do exist. All are less-strongly supported by our data. For example, one possibility is that mutant Coq7p proteins with reduced membrane-binding capacity are toxic to yeast cells and Cld1p overexpression somehow reduces their level. Although we showed that Cld1p overexpression decreased the level of mutant Coq7p protein in coq7-22(HA-tag) yeast, ubiquinone levels went up, not down, arguing against this hypothesis. Moreover, coq7-11(W120R) mutants, which are suppressible by CLD1 overexpression, exhibited no evidence of toxicity with respect to replicative lifespan when compared to control coq7-2i(Q48R) cells, further arguing against this idea. Another alternate explanation is that the shift in the acyl signature of MLCL (and presumably cardiolipin by extension) toward C18:1, led to enhanced mitochondrial electron transport chain activity in hypomorphic coq7 mutants, and this was the reason they recovered their ability to grow on ethanol. Consistent with this idea, it is well established that mitochondrial respiratory chain complexes require cardiolipin for their structural and functional integrity (reviewed in [43]). Against this hypothesis, however, is our observation that the catalytically-compromised coq7-5(H153L) hypomorph was not equally rescued by CLD1 overexpression. Also, we observed a marked recovery in Q production in suppressed cells, again suggesting that the suppressive effect of Cld1p overexpression was specific to the Coq7p protein and not due to supplemental enhancement of ETC activity.

Recently, Busso and colleagues [52] also made use of random PCR mutagenesis in an effort to probe the structure/function of Coq7p. They identified only a single and weakly hypomorphic allele of coq7, (D53G), which contrasts with the 78 that we identified in this study, highlighting the strength of our new screening approach. These authors turned to an automated server-generated structural model of Coq7p and, in conjunction with site-directed mutagenesis, tested the function of several amino acid changes in the vicinity of D53G. Using this approach, they discovered a novel coq7(S114E) mutant which accumulated DMQ6 at the expense of Q6, and which was severely hypomorphic for growth on ethanol/glycerol at 30°C, and lethal at 37°C. Overexpression of Coq8p partially rescued the growth defect. When coq7(S114E) cells were placed at the non-permissive temperature of 37°C, the stability of Coq3p and Coq4p halved. This was not observed at 30°C, even though these mutants remained severely hypomorphic for growth on ethanol/glycerol. This finding suggests that formation of the 700kDa Q biosynthetic pre-complex was not limiting in coq7(S114E) mutants at lower temperatures and that some other function of Coq7p was disrupted. S114E maps to the same region of Coq7p where all our Cld1p-suppressible mutations localize. As mentioned above, this region is predicted to be surface-exposed, hydrophobic, membrane-binding, interfacial with the Coq7p C-terminus, and sit directly underneath the active site where the DMQ6 tail extends [21].

Finally, Freyer and colleagues [6] recently reported the first known COQ7 mutation in a patient with primary Q10 deficiency. The Freyer study demonstrated that administration of 2,4-dihydroxybenzoic acid (2,4DHB), a quinone analogue containing the ring modification normally catalyzed by COQ7, rescued the biochemical defect in patient-derived fibroblasts. This same compound was shown in an earlier study to essentially cure a mouse model of Coq7 deficiency [53]. Both studies had their genesis in yeast work using coq6 mutants and related quinone analogues [54, 55]. Together, these findings highlight the non-linearity of Q biosynthesis and portend what will hopefully be a brighter future for patients with Q10 deficiency. These findings also underscore the exciting conclusion from our study, that not only is there potentially another way to treat Q10 deficiency in humans, albeit not as elegant as the solution above, but more importantly that we have broadened the field towards identifying alternate mechanisms for potentially reversing other deficiencies that result from alterations in the activity of critical membrane-bound enzymes.

Materials and Methods

Strains

Strain information for all lines generated in this study is provided in S1 Table. Stock lines, SEY6210 (MATα leu2-3,112 ura3-52 his3-Δ200 trp1-Δ901 suc2-Δ9 lys2-801; GAL) and TA405 (MATα/a his3-11,15/ his3-11,15 leu2-3,112/ leu2-3,112 can1/can1) were maintained on rich media [1% (w/v) yeast extract, 2% peptone, 2% dextrose (YEPD2%) + 2% agar]. Strains containing labile plasmids were maintained under constant selection using either 3% ethanol as carbon source (YEPE3%), or on synthetic dropout (SD) media supplemented with 2% glucose.

Generation of coq7 allelic series

A 1371 base pair (bp) fragment containing the COQ7 gene was PCR amplified from SEY6210 and cloned into the BamH1 and Sal1 sites of pRS315(CEN) using forward (5’-CGCGGATCCGCTAGATGATGGATCTAAC-3’) and reverse (5’-GGACGCGTCGACGTTCATTATCTTCGTTCGGCATTTCC-3’) primers to form pRS315/COQ7. Mutagenic PCR, using Taq DNA polymerase, 40 μM Mn2+, 20 rounds of thermal cycling and the same primer pair listed above, was then used to randomly introduce ~1 error/kbp along the entire 1371 bp COQ7 fragment. The resulting ensemble of PCR products was then directly transformed into strain SHM1 [SEY6210 Δcat5/coq7-19::GFP;HIS3] [56] along with an equal molar amount of purified pRS315/COQ7 previously cut with SnaB1 and HindIII. Both restriction sites reside within the COQ7 locus–approximately 50 bp from the 5’ and 3’ end, respectively. Homologous recombination occurred with high enough frequency to make this a viable alternative to cloning the PCR products manually. This and all subsequent transformations were undertaken using lithium acetate. Transformants containing the recombined plasmid were selected on glucose-containing minimal media lacking leucine (SD-L + 2% glucose) at either 25°C (2300 recombinants) or 30°C (1300 recombinants). Plasmid alone recombined with a frequency of <0.2% of the total number of positives. After 3 days, colonies were doubly replica plated onto YEPE3% + 0.1% DEX. and grown at 25°C and 37°C, or 30°C and 37°C, respectively, and hypomorphic or temperature-sensitive coq7 alleles isolated. Seventy-eight mutants in total were identified. Plasmids were recovered from a sub-collection of these yeast and their entire COQ7 insert sequenced bi-directionally. Several alleles were re-integrated back into the coq7Δ locus of SHM1 (S1 Table). To do this, mutant coq7 alleles were excised from their pRS315 vector backbone using BamH1 and SalI and cloned by homologous recombination into the SHM1 coq7Δ locus. Integrants were selected on YEPE3% at a temperature permissive for growth (S1 Table), and insertion at the coq7Δ locus was confirmed by PCR. The HA-epitope-tagged coq7 alleles in psHA71 and pmHA71 have been described previously [22]. Both alleles are under the expression of the ADH1 promoter. Sequence analysis revealed both constructs also differ from the COQ7 sequence present in SEY6210 at position 177 (M to I). This is a naturally-arising Coq7p polymorphism that confers resistance to petite formation [57]. NM101 (MATa coq7-1 leu2-3,112 ura3-52 his3-), which contains the previously described coq7-1(G65D) allele [15], was the original source of genomic DNA used for PCR generation of psHA71 and pmHA71.

COQ7-HA and COQ7-myc construction

Wild type COQ7 was tagged with a myc- or haemagglutinin- (HA) epitope as follows: Site-directed mutagenesis was used to introduce an EcoR1 site at the C-terminus of COQ7 in the plasmid pRS315/COQ7 using the following primer pair (EcoR1-5’): 5’-GGAGTGCCGAAAGAATTCAACCACCAGAAAGTGGC-3’ and (EcoR1-3’): 5’-GCCACTTTCTGGTGGTTGAATTCTTTCGGCACTCC-3’. Next, primer pairs encoding the myc- or HA- epitope were annealed, then directly ligated into the newly generated EcoR1 site to form pRS315/coq7-9 and pRS315/coq7-10 respectively: (myc5’): 5’-AATTGGGGGGGAGGAGCAGAAGCTGATCTCAGAGGAGGACCTGCATATGTAA-3’, (myc3’): 5’-AATTTTACATATGCAGGTCCTCCTCTGAGATCAGCTTCTGCTCCTCCCCCCC-3’; (HA5’): 5’-AATTGGGGGGTACCCATACGACGTACCAGATTACGCTCATATGTAA-3’, (HA3’): 5’-AATTTTACATATGAGCGTAATCTGGTACGTCGTATGGGTACCCCCC-3’.

PADH1-COQ7-HA (CEN) suppressor screen

Yeast strain SHM1, containing the coq7-19 (cat5Δ::GFP;HIS3) null allele, was transformed with psHA71 [22]. This plasmid carries the hypomorphic coq7-22(PADH1-COQ7-HA) allele on a pRS316 (CEN) vector backbone. Alone, coq7-22(PADH1-COQ7-HA) conferred only severely hypomorphic growth on YEPE3% at all tested temperatures (15–37°C). The resulting strain was grown to saturation in YEPD2% (10ml), collected by centrifugation, then transformed with a library of genomic fragments constructed from SEY6210 and cloned into the high copy number vector pRS424 (2μ). (This library was a gift from Dr. Howard Bussey, McGill University). Following a two hour recovery in YPD2%, the transformation mix was plated directly onto “petite media” [YEPE3% supplemented with 0.1% dextrose (YEPE3% + D0.1%)], and slow growth suppressors collected at a temperature of 30°C. In addition to obtaining multiple copies of COQ7, a single genomic fragment (28.57) containing CLD1 was isolated.

Cld1p homology model

A homology model of Cld1p was built remotely using the algorithm of Nielsen and colleagues [58] via the CPHmodels-3.0 server (www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/CPHmodels/). Epoxide hydrolase-1 from Solanum tuberosum, [59], (PDB structure 2CJP.A), served as the model-building template (alignment length 335 amino acids, double-sided Z-score 28.6). The catalytic triad of Cld1p (H424, D392, S230) was originally identified using STRAP [60], which facilitated the structure-guided alignment of several hundred α/β hydrolase fold-containing proteins, and the authenticity of this triad has now been confirmed experimentally [37].

Western blotting

Yeast strains were cultured in YEPE3% (3ml) at room temperature (RT, 25°C), with shaking (100 rpm). Cultures were harvested upon reaching stationary phase, the precise time depending on the particular strain. Cells were pelleted, resuspended in 200 μl boiling yeast lysis buffer (1% SDS, 62.5mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 8M urea, 4% β-mercaptoethanol, 0.0125% bromophenol blue), boiled for two minutes, vortexed in the presence of ½ volume glass beads (5 mins), boiled for a further two minutes, then 20 μl of solubilized protein loaded onto a 4–20% Novagen pre-cast SDS-PAGE gel. Coq7p-HA was detected using western analysis after transfer to nitrocellulose (18V, 14 hr., RT) and incubation with a mouse, anti-haemagglutinin (HA) antibody (Babco, monoclonal 16B12, 1:500 dilution). Protein loading was quantified using Coomassie Blue.

Total membrane lipid extraction

Total membrane lipids were isolated using a modification of the Bligh and Dyer method [61]. Briefly, relevant yeast strains were grown to an OD600 of 3.7, 10.5 and 13.2, then harvested by centrifugation (10 min at 624 × g, 4°C). A standardized cell-pellet wet weight of 1 gram was employed for all subsequent analyses. For spheroplasting, cell pellets were resuspended in ice cold water (20 ml), washed twice in the same volume of water, then resuspended in 1.4 ml/wet weight (g) pellet in pre-warmed spheroplast buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 9.3), 5 mM EDTA and 1% β-mercaptoethanol or 10 mM DTT), for 15 mins at 30°C. The cell suspension was then centrifuged at 4°C, washed thrice with 20 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.65), then the cell pellet resuspended in 20 mM potassium phosphate (pH 7.65) containing 1.2M sorbitol 4 ml/wet weight (g) pellet. Cells were then warmed to 40°C for 3–4 mins and Zymolyase (Fisher Scientific) added to a final concentration of 2.5 mg/g. The cell suspension was incubated at 30°C for 3 hours. At the end of the incubation, spheroplasts were pelleted by centrifugation, washed three times in 1.2M sorbitol (2 ml /wet weight (g)), then resuspended in 1 ml of the same solution. For each 1 ml sample, 3.75 ml of 1:2 (v/v) chloroform:methanol was added and samples vortexed for 2 minutes. Subsequently, 1.25 ml of chloroform and 1.25 ml of distilled water was also added. The bottom phase was recovered following centrifuging at 1500 x g for 5 mins. The extracted solvent was evaporated under air flow and then the lipid extract was re-dissolved in 50 μl of a 2:1 mix of chloroform/methanol (v/v). The lipids were then stored in glass vials with butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT) to prevent lipid oxidation, ready for separation by Thin Layer Chromatography (TLC).

Thin layer chromatography

Analysis of cardiolipin and monolysocardiolipin in lipid extracts from whole-cell lysates and mitochondrial fractions was undertaken using TLC. Briefly, lipids were separated using Whatman® Partisil™ LK5 TLC plates, following the methodology of Vaden and colleagues [62]. TLC plates were first wetted with 1.8% boric acid in ethanol, then dried at 110°C for 15 minutes to activate the silica. Next, equal volumes (10 μL) of test samples were spotted onto the relevant lane of a TLC plate then separated using a solvent phase consisting of 30:35:7:35 (v/v/v/v) chloroform/ethanol/water/triethylamine. When separation was complete, TLC plates were vacuum dried and spots developed using sulfuric acid charring. Spots were identified using purified lipid standards that included cardiolipin (Avanti polar lipids, # 840012P), phosphatidylserine (Avanti polar lipids, # 870336P), and a defined mixture of abundant eukaryotic lipids extracted from Soy (Avanti Polar Lipids, # 690050P). Developed spots were immediately photographed and then spot area and density quantified using Image J (http://imagej.nih.gov/ij/). For statistical testing, MLCL to CL ratios were calculated for samples measured in triplicate technical replicates, collected from duplicate independent experiments, at three separate OD600 values. Significance testing for strain- and growth phase-related differences was undertaken using multiple regression analysis (Real Statistics Resource Pack software, Release 4.3). Details provided in S2 Table).

Q6 and DMQ6 quantification

Yeast quinone levels were quantified using a modification of the procedure described by Schultz and colleagues [63]. Strains of interest were cultured in liquid YEPE3% at 25°C to the following optical densities (OD600, 1 cm pathlength): 1.7, 3.7, 6.7, 8.7, 10.5, 13.2. In total, three independent experimental replicates were collected for each OD600. Cells were collected by centrifugation (10 min at 624 × g, 4°C), washed once with H2O (10 ml), transferred to 50-ml pre-weighed glass tubes, then re-pelleted and again resuspended in H2O (12 ml). Three 1 ml aliquots were taken from each sample and cell pellet wet-weights determined. Cell pellets were dried for 1 hr. at 56°C and then their dry-weights determined. The average of the dry- to wet-weight ratio for the three 1 ml aliquots was then used to calculate the dry weight of the remaining sample. The remaining cell suspension was centrifuged, and the total wet weight of the cell pellet was determined. Glass beads (10 times the cell pellet wet weight), and 250 μl of Q9 internal standard (20 μg/ml) were added to the pellet and then the tubes were immediately flooded with nitrogen, capped, covered with foil, and kept on ice to prevent oxidation. Cells were lysed by vortexing for 2 min. Lipids were extracted by adding water/petroleum ether/methanol (1:4:6) and vortexing for an additional 30 sec. In some instances the water component was replace by 1M NaCl to enhance phase separation. Phases were separated by centrifugation (10 min at 624 × g and 4 °C). The upper petroleum ether layer was then transferred to a 10-ml glass tube. 4 ml of petroleum ether was added to the glass bead-aqueous phase, and the samples were re-vortexed for 30 sec. The petroleum ether layers from a total of three extractions were pooled and dried under nitrogen. Lipids were resuspended in a final volume of 1 ml isopropanol. Quinones (Q6, DMQ6 and Q9) were separated by reversed-phase high pressure liquid chromatography using a C18 column (Alltech Econosphere 5-μm, 4.6 × 250-mm, isocratic mode, mobile phase 72:20:8 (v/v/v) methanol/ethanol/propanol, 1 ml/min, 40°C) and quantitated using a Waters 600E UV detector at a wavelength of 275 nm. Peaks representing Q6 (Avanti polar lipids, # 900150O) and Q9 (Sigma, # 27597) were identified using purified standards. The peak representing DMQ6 was identified using a quinone extract from the yeast strain NM101, which is unable to manufacture Q6 and instead accumulates this intermediate [15]. Peak areas were normalized based on starting dry weight and then significance testing for quinone-, strain- and growth phase-related differences was undertaken using multiple regression analysis (Real Statistics Resource Pack software, Release 4.3). Details are provided in S3 Table.

Replicative lifespan analysis

Replicative lifespan assays were conducted at 25°C following the procedure of Steffen and colleagues [64], except YEPE3% + 2% agar was employed. Strains were coded to remove scoring bias. A total of 40 virgin cells (over replicate experiments) for each strain was analyzed using microdissection and the number of daughter cells that budded off from individual cells was recorded. Mother cells were monitored until no new buds were produced. Data was analyzed using a log rank test with significance (p<0.05) set against a chi square distribution using one degree of freedom (χ2 >3.84). Mother cells that were either damaged or could not be distinguished from daughter cells were censored from the analysis. Censored daughter cells were excluded from the calculation of mean RLS in Fig 7.

High performance liquid chromatography—electrospray ionization—tandem mass spectrometry (HPLC-ESI-MS/MS)

Four or five cultures of relevant yeast strains were cultured at 25°C in YEPE3% to mid log phase (OD600 6–10). Sample OD600 values were adjusted to 7.0 and a 35 ml volume was then processed for HPLC-ESI-MS/MS as follows. Cells were collected by centrifugation (10 min at 624 × g, 4°C), washed with MS-grade H2O (3 x 10 ml), then cardiolipins (CLs) and monolysocardiolipins (MLCL) extracted from yeast pellets with methanol, chloroform, and 0.1N HCl (1:1:0.9) following the procedure of Bazan and colleagues [44]. Briefly, cell pellets were homogenized with a Mini-Beadbeater-24 Homogenizer (BioSpec Products). CL (14:0)4 [1',3'-bis[1,2-dimyristoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho]-sn-glycerol] (Avanti Polar Lipids, #710332P) was added as the stable isotope-labeled standard prior to extraction. MS analyses were conducted on a Thermo Fisher Q Exactive (San Jose, CA) with on-line separation using a Thermo Fisher/Dionex RSLC nano HPLC system and Waters Atlantis dC18 column (150 μm x 105 mm; 3 μm) (Waters Corporation, Massachusetts). The gradient was started at 10% B and run from 10% B to 99% B over 40 min with the flow rate of 6 μl/min—where mobile phase A was acetonitrile/water (40:60) containing 10 mM ammonium acetate and mobile phase B was acetonitrile/isopropanol (10:90) containing 10 mM ammonium acetate. Data-dependent analyses were conducted using one full MS scan (70,000 resolution) followed by six tandem-MS scans with electrospray negative ion detection. Quantitative results were obtained by referencing experimental MLCL peak areas against a standard curve of CL(18:1)4 [1',3'-bis[1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho]-sn-glycerol] (Avanti Polar Lipids, #710335P), following CL(14:0)4 normalization. Significance testing for differences between strains was undertaken using Student’s t-test (p < 0.05), without correction for multiple testing.

Supporting Information

Detailed description of alleles comprising coq7 hypomorphic series. (Corresponds to Table 1).

(XLS)

Variable re-coding used for multiple regression analysis. (Corresponds to Fig 4A).

(XLSX)

Variable re-coding used for multiple regression analysis. (Corresponds to Fig 6A–6F).

(XLSX)

(Corresponds to replicative life span data shown in Fig 7A and7B).

(XLSX)

Acknowledgments

Dr. Rob Poyton (CU Boulder) for help with tetrad dissections. Mass spectrometry analyses were conducted in the Metabolomics Core Facility of the Mass Spectrometry Laboratory at the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, with instrumentation funded in part by NIH Grant 1S10RR031586-01. Additional financial support was provided by the Ellison Medical Foundation (http://www.ellisonfoundation.org/; AG-NS-051908; S.L.R.), the National Institute on Aging (https://www.nia.nih.gov/; AG-025207, AG-047561; S.L.R.), and the National Institute for General Medical Sciences (https://www.nigms.nih.gov,; K12-GM111726; M.B.B.). We thank Dr. Gian Paolo Littarru (Polytechnic University of The Marche, Ancona, Italy) for providing purified Q6, Dr. Randy Glickman (UTHSCSA, TX.) for access to HPLC instrumentation, and Oxana Radetskaya for critical comments on the manuscript. Funding sources had no role in study design, data collection or analysis, our decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. The authors declare there are no conflicting interests controlling the publication of this manuscript.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

Mass spectrometry analyses were conducted in the Metabolomics Core Facility of the Mass Spectrometry Laboratory at the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, with instrumentation funded in part by NIH Grant 1S10RR031586-01. Additional financial support was provided by the Ellison Medical Foundation (http://www.ellisonfoundation.org/; AG-NS-051908; S.L.R.), the National Institute on Aging (https://www.nia.nih.gov/; AG-025207, AG-047561; S.L.R.), and the National Institute for General Medical Sciences (https://www.nigms.nih.gov,; K12-GM111726; M.B.B.).

References

- 1.Quinzii CM, Hirano M, DiMauro S. CoQ10 deficiency diseases in adults. Mitochondrion. 2007;7 Suppl:S122–6. Epub 2007/05/09. 10.1016/j.mito.2007.03.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gironi M, Lamperti C, Nemni R, Moggio M, Comi G, Guerini FR, et al. Late-onset cerebellar ataxia with hypogonadism and muscle coenzyme Q10 deficiency. Neurology. 2004;62(5):818–20. Epub 2004/03/10. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.DiMauro S, Quinzii CM, Hirano M. Mutations in coenzyme Q10 biosynthetic genes. J Clin Invest. 2007;117(3):587–9. Epub 2007/03/03. 10.1172/JCI31423 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mollet J, Delahodde A, Serre V, Chretien D, Schlemmer D, Lombes A, et al. CABC1 gene mutations cause ubiquinone deficiency with cerebellar ataxia and seizures. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;82(3):623–30. Epub 2008/03/06. S0002-9297(08)00147-X [pii] 10.1016/j.ajhg.2007.12.022 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gonzalez-Mariscal I, Garcia-Teston E, Padilla S, Martin-Montalvo A, Pomares Viciana T, Vazquez-Fonseca L, et al. The regulation of coenzyme q biosynthesis in eukaryotic cells: all that yeast can tell us. Mol Syndromol. 2014;5(3–4):107–18. 10.1159/000362897 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Freyer C, Stranneheim H, Naess K, Mourier A, Felser A, Maffezzini C, et al. Rescue of primary ubiquinone deficiency due to a novel COQ7 defect using 2,4-dihydroxybensoic acid. J Med Genet. 2015;52(11):779–83. 10.1136/jmedgenet-2015-102986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Licitra F, Puccio H. An overview of current mouse models recapitulating coenzyme q10 deficiency syndrome. Mol Syndromol. 2014;5(3–4):180–6. 10.1159/000362942 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tzagoloff A, Dieckmann CL. PET genes of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microbiol Rev. 1990;54(3):211–25. Epub 1990/09/01. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tran UC, Clarke CF. Endogenous synthesis of coenzyme Q in eukaryotes. Mitochondrion. 2007;7(Supplement 1):S62–S71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marbois B, Xie LX, Choi S, Hirano K, Hyman K, Clarke CF. para-Aminobenzoic acid is a precursor in coenzyme Q6 biosynthesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(36):27827–38. Epub 2010/07/02. M110.151894 [pii] 10.1074/jbc.M110.151894 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pierrel F, Hamelin O, Douki T, Kieffer-Jaquinod S, Muhlenhoff U, Ozeir M, et al. Involvement of mitochondrial ferredoxin and para-aminobenzoic acid in yeast coenzyme Q biosynthesis. Chem Biol. 2010;17(5):449–59. Epub 2010/06/11. S1074-5521(10)00155-9 [pii] 10.1016/j.chembiol.2010.03.014 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Turunen M, Olsson J, Dallner G. Metabolism and function of coenzyme Q. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1660(1–2):171–99. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marbois B, Gin P, Gulmezian M, Clarke CF. The yeast Coq4 polypeptide organizes a mitochondrial protein complex essential for coenzyme Q biosynthesis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1791(1):69–75. Epub 2008/11/22. S1388-1981(08)00190-X [pii] 10.1016/j.bbalip.2008.10.006 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Padilla S, Tran UC, Jimenez-Hidalgo M, Lopez-Martin JM, Martin-Montalvo A, Clarke CF, et al. Hydroxylation of demethoxy-Q6 constitutes a control point in yeast coenzyme Q6 biosynthesis. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2009;66(1):173–86. Epub 2008/11/13. 10.1007/s00018-008-8547-7 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marbois BN, Clarke CF. The COQ7 gene encodes a protein in saccharomyces cerevisiae necessary for ubiquinone biosynthesis. J Biol Chem. 1996;271(6):2995–3004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hsieh EJ, Gin P, Gulmezian M, Tran UC, Saiki R, Marbois BN, et al. Saccharomyces cerevisiae Coq9 polypeptide is a subunit of the mitochondrial coenzyme Q biosynthetic complex. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2007;463(1):19–26. Epub 2007/03/30. S0003-9861(07)00090-2 [pii] 10.1016/j.abb.2007.02.016 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lohman DC, Forouhar F, Beebe ET, Stefely MS, Minogue CE, Ulbrich A, et al. Mitochondrial COQ9 is a lipid-binding protein that associates with COQ7 to enable coenzyme Q biosynthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111(44):E4697–705. 10.1073/pnas.1413128111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martin-Montalvo A, Gonzalez-Mariscal I, Pomares-Viciana T, Padilla-Lopez S, Ballesteros M, Vazquez-Fonseca L, et al. The phosphatase Ptc7 induces coenzyme Q biosynthesis by activating the hydroxylase Coq7 in yeast. J Biol Chem. 2013;288(39):28126–37. 10.1074/jbc.M113.474494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Poon WW, Do TQ, Marbois BN, Clarke CF. Sensitivity to treatment with polyunsaturated fatty acids is a general characteristic of the ubiquinone-deficient yeast coq mutants. Mol Aspects Med. 1997;18 Suppl:S121–7. Epub 1997/01/01. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tran UC, Marbois B, Gin P, Gulmezian M, Jonassen T, Clarke CF. Complementation of Saccharomyces cerevisiae coq7 mutants by mitochondrial targeting of the Escherichia coli UbiF polypeptide: two functions of yeast Coq7 polypeptide in coenzyme Q biosynthesis. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(24):16401–9. Epub 2006/04/21. M513267200 [pii] 10.1074/jbc.M513267200 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rea S. CLK-1/Coq7p is a DMQ mono-oxygenase and a new member of the di-iron carboxylate protein family. FEBS Lett. 2001;509(3):389–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jonassen T, Proft M, Randez-Gil F, Schultz JR, Marbois BN, Entian KD, et al. Yeast Clk-1 homologue (Coq7/Cat5) is a mitochondrial protein in coenzyme Q synthesis. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(6):3351–7. Epub 1998/03/07. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jiang N, Levavasseur F, McCright B, Shoubridge EA, Hekimi S. Mouse CLK-1 is imported into mitochondria by an unusual process that requires a leader sequence but no membrane potential. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(31):29218–25. 10.1074/jbc.M103686200 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xie LX, Hsieh EJ, Watanabe S, Allan CM, Chen JY, Tran UC, et al. Expression of the human atypical kinase ADCK3 rescues coenzyme Q biosynthesis and phosphorylation of Coq polypeptides in yeast coq8 mutants. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2011;1811(5):348–60. Epub 2011/02/08. 10.1016/j.bbalip.2011.01.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wong A, Boutis P, Hekimi S. Mutations in the clk-1 Gene of Caenorhabditis elegans Affect Developmental and Behavioral Timing. Genetics. 1995;139(3):1247–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kayser EB, Sedensky MM, Morgan PG, Hoppel CL. Mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation is defective in the long-lived mutant clk-1. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(52):54479–86. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Larsen PL, Clarke CF. Extension of life-span in Caenorhabditis elegans by a diet lacking coenzyme Q. Science. 2002;295(5552):120–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cristina D, Cary M, Lunceford A, Clarke C, Kenyon C. A Regulated Response to Impaired Respiration Slows Behavioral Rates and Increases Lifespan in <italic>Caenorhabditis elegans</italic>. PLoS Genet. 2009;5(4):e1000450 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Butler JA, Ventura N, Johnson TE, Rea SL. Long-lived mitochondrial (Mit) mutants of Caenorhabditis elegans utilize a novel metabolism. FASEB J. 2010;24(12):4977–88. Epub 2010/08/25. fj.10-162941 [pii] 10.1096/fj.10-162941 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Butler JA, Mishur RJ, Bhaskaran S, Rea SL. A metabolic signature for long life in the Caenorhabditis elegans Mit mutants. Aging Cell. 2013;12(1):130–8. Epub 2012/11/24. 10.1111/acel.12029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Monaghan RM, Barnes RG, Fisher K, Andreou T, Rooney N, Poulin GB, et al. A nuclear role for the respiratory enzyme CLK-1 in regulating mitochondrial stress responses and longevity. Nat Cell Biol. 2015;17(6):782–92. 10.1038/ncb3170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Martin-Montalvo A, Gonzalez-Mariscal I, Padilla S, Ballesteros M, Brautigan DL, Navas P, et al. Respiratory-induced coenzyme Q biosynthesis is regulated by a phosphorylation cycle of Cat5p/Coq7p. Biochem J. 2011;440(1):107–14. Epub 2011/08/05. 10.1042/BJ20101422 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Padilla S, Jonassen T, Jimenez-Hidalgo MA, Fernandez-Ayala DJ, Lopez-Lluch G, Marbois B, et al. Demethoxy-Q, an intermediate of coenzyme Q biosynthesis, fails to support respiration in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and lacks antioxidant activity. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(25):25995–6004. Epub 2004/04/14. 10.1074/jbc.M400001200 M400001200 [pii]. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Behan RK, Lippard SJ. The aging-associated enzyme CLK-1 is a member of the carboxylate-bridged diiron family of proteins. Biochemistry. 2010;49(45):9679–81. Epub 2010/10/07. 10.1021/bi101475z . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lu TT, Lee SJ, Apfel UP, Lippard SJ. Aging-associated enzyme human clock-1: substrate-mediated reduction of the diiron center for 5-demethoxyubiquinone hydroxylation. Biochemistry. 2013;52(13):2236–44. 10.1021/bi301674p [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ye C, Lou W, Li Y, Chatzispyrou IA, Huttemann M, Lee I, et al. Deletion of the cardiolipin-specific phospholipase Cld1 rescues growth and life span defects in the tafazzin mutant: implications for Barth syndrome. J Biol Chem. 2014;289(6):3114–25. 10.1074/jbc.M113.529487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Baile MG, Whited K, Claypool SM. Deacylation on the matrix side of the mitochondrial inner membrane regulates cardiolipin remodeling. Mol Biol Cell. 2013;24(12):2008–20. 10.1091/mbc.E13-03-0121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Beranek A, Rechberger G, Knauer H, Wolinski H, Kohlwein SD, Leber R. Identification of a Cardiolipin-specific Phospholipase Encoded by the Gene CLD1 (YGR110W) in Yeast. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(17):11572–8. 10.1074/jbc.M805511200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sirum-Connolly K, Mason TL. Functional Requirement of a Site-Specific Ribose Methylation in Ribosomal RNA. Science. 1993;262(5141):1886–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Struhl K. Naturally occurring poly(dA-dT) sequences are upstream promoter elements for constitutive transcription in yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1985;82(24):8419–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hotelier T, Renault L, Cousin X, Negre V, Marchot P, Chatonnet A. ESTHER, the database of the alpha/beta-hydrolase fold superfamily of proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32(Database issue):D145–7. Epub 2003/12/19. 10.1093/nar/gkh141 32/suppl_1/D145 [pii]. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bione S, D'Adamo P, Maestrini E, Gedeon AK, Bolhuis PA, Toniolo D. A novel X-linked gene, G4.5. is responsible for Barth syndrome. Nat Genet. 1996;12(4):385–9. Epub 1996/04/01. 10.1038/ng0496-385 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Paradies G, Paradies V, Ruggiero FM, Petrosillo G. Cardiolipin and mitochondrial function in health and disease. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2014;20(12):1925–53. Epub 2013/10/08. 10.1089/ars.2013.5280 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bazan S, Mileykovskaya E, Mallampalli VK, Heacock P, Sparagna GC, Dowhan W. Cardiolipin-dependent Reconstitution of Respiratory Supercomplexes from Purified Saccharomyces cerevisiae Complexes III and IV. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2013;288(1):401–11. Epub 2012/11/23. 10.1074/jbc.M112.425876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Metzler DE. Biochemistry: The chemical reaction of living cells New York: Academic Press; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wasko BM, Kaeberlein M. Yeast replicative aging: a paradigm for defining conserved longevity interventions. FEMS Yeast Res. 2014;14(1):148–59. Epub 2013/10/15. 10.1111/1567-1364.12104 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPmc4134429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Adamian L, Naveed H, Liang J. Lipid-binding surfaces of membrane proteins: evidence from evolutionary and structural analysis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1808(4):1092–102. Epub 2010/12/21. 10.1016/j.bbamem.2010.12.008 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPmc3381425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lee AG. How lipids affect the activities of integral membrane proteins. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1666(1–2):62–87. Epub 2004/11/03. 10.1016/j.bbamem.2004.05.012 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.de Kroon AI, Rijken PJ, De Smet CH. Checks and balances in membrane phospholipid class and acyl chain homeostasis, the yeast perspective. Progress in lipid research. 2013;52(4):374–94. Epub 2013/05/02. 10.1016/j.plipres.2013.04.006 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Killian JA. Hydrophobic mismatch between proteins and lipids in membranes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1376(3):401–15. Epub 1998/11/07. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schlame M, Horvath L, Vigh L. Relationship between lipid saturation and lipid-protein interaction in liver mitochondria modified by catalytic hydrogenation with reference to cardiolipin molecular species. Biochem J. 1990;265(1):79–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Busso C, Ferreira-Junior JR, Paulela JA, Bleicher L, Demasi M, Barros MH. Coq7p relevant residues for protein activity and stability. Biochimie. 2015;119:92–102. 10.1016/j.biochi.2015.10.016 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]