Abstract

Background

Many rectal cancer patients experience tumor downstaging and some are found to achieve a pathological complete response (pCR) after neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy (nCRT). Previous data suggest that there is an association between the time interval from nCRT completion to surgery and tumor response rates, including pCR. However, these studies have been primarily from single institutions with small sample sizes. The aim of this study was to examine the relationship between a longer interval after nCRT and pCR in a nationally representative cohort of rectal cancer patients.

Study Design

Clinical stage II–III rectal cancer patients undergoing nCRT with a documented surgical resection were selected from the 2006 – 2011 National Cancer Data Base. Multivariable logistic regression analysis was used to assess the association between nCRT-surgery interval time (<6 weeks, 6–8 weeks, >8 weeks) and the odds of pCR. The relationship between nCRT-surgery interval, surgical morbidity, and tumor downstaging was also examined.

Results

Overall, 17,255 patients met the inclusion criteria. A nCRT-surgery interval time >8 weeks was associated with higher odds of pCR (OR=1.12, 95%CI=1.01–1.25) and tumor downstaging (OR=1.11, 95%CI =1.02–1.25). The longer time delay was also associated with lower odds of 30-day readmission (OR=0.82, 95%CI: 0.70–0.92).

Conclusions

A nCRT-surgery interval time >8 weeks results in increased odds of pCR with no evidence of associated increased surgical complications compared to 6–8 weeks. This data supports the implementation of a lengthened interval after nCRT to optimize the chances of pCR and perhaps add to the possibility of ultimate organ preservation (non-operative management).

Colorectal cancer is the third most frequently diagnosed malignancy in the U.S. with approximately 40,000 new cases of rectal cancer annually.(1) Multimodal therapy, which consists of chemoradiation followed by surgery in the form of a total mesorectal excision, has become the standard of care for locally advanced rectal cancer (stage II and stage III disease). Neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy (nCRT) has been shown to significantly reduce the local recurrence rate and has been associated with an increase in the overall survival rate.(2) Despite this, a large percentage of patients in the US still undergo a total proctectomy (abdominoperineal resection) with permanent end colostomy. In contrast, few patients undergo rectal preserving treatments such as local excision or achieve complete tumor disappearance and thereby avoid any surgery whatsoever.(3, 4)

The traditional North American paradigm for the delivery of neoadjuvant therapy in rectal cancer consists of 45 to 50.4 Gray (Gy) delivered in 25–28 fractions with sensitizing continuous fluorouracil infusion or capecitabine administered throughout the radiation course. Patients then undergo surgical resection approximately 6–8 weeks after finishing nCRT.(5, 6) This recommendation is based primarily on the Lyon R90-01 trial, which found improved clinical tumor response and pathologic downstaging in patients undergoing surgery 6–8 weeks after radiation therapy compared to those with a two-week interval.(7) As a result of neoadjuvant therapy, many patients experience significant tumor downstaging and some are found to have a pathological complete response (pCR) on histologic examination of the resected specimen.(8, 9) There is a growing body of data to suggest that pCR is significantly associated with a reduction in both local and systemic recurrence and superior overall survival compared to patients with partial or no response.(10) While pCR may potentially be a marker for favorable tumor biology, it is still imperative in clinical practice to attempt to maximize our chances of attaining pCR. This is especially true if a non-operative or observational approach is to be considered.

Thus, there is great clinical interest in identifying factors that may increase tumor regression and enhance the pCR rate. This has prompted some researchers to examine the relationship between the length of time between nCRT completion and surgery (nCRT-surgery interval) and subsequent tumor response. These studies suggested a potential association between a longer nCRT-surgery interval and an increased rate of pathological complete response.(11) However, this work has been primarily from single institutions with small sample sizes (between 33–397 patients). Consequently, these studies lack sufficient power to adjust for the confounding impact of different radiotherapy (RT) dosages and variations in time to surgery after neoadjuvant therapy. The aim of this study was to examine the relationship between an increased nCRT-surgery interval compared to the current standard of care and pCR in a large, nationally representative cohort of rectal cancer patients who underwent neoadjuvant therapy prior to definitive surgical resection.

Methods

Study Population

Data for this study were retrieved retrospectively from the National Cancer Data Base (NCDB). This hospital-based cancer registry is sponsored by a joint program between the Commission on Cancer of the American College of Surgeons and the American Cancer Society. The database collects information on all types of cancer from more than 1,500 hospitals with Commission-accredited cancer programs in the United States and Puerto Rico. Available information includes patient demographics, treatment regiments, tumor histology, oncologic staging as well as other patient characteristics.(12) Participating NCDB institutions report information based in the Facility Oncology Data Standards manual.(13)

A total of 321,768 rectal cancer cases were identified in the NCDB Participant User File report. The analysis was limited to cases of adenocarcinoma, mucinous adenocarcinoma, and signet ring cell carcinoma diagnosed between 2006 and 2011. The sample was further restricted to cases with clinical stage II and III rectal cancer who underwent chemoradiotherapy before surgery and who had a documented surgical resection. Patients with incomplete information about time from diagnosis to surgery and radiation as well as pathological T and N status were excluded for a total sample size of 17,255. Figure 1 shows this inclusion process.

Figure 1.

Inclusion diagram.

Measurement of nCRT-Surgery Interval Time

The database does not contain an explicit variable for nCRT-surgery interval time, but does contain information on: number of days between the date of initial diagnosis and the date of the most definitive surgical procedure (A), number of days between the date of diagnosis and the date of radiation therapy initiation at any facility (B), and number of days of radiation therapy treatment (C). The nCRT-surgery interval time was calculated using the following formula: nCRT - surgery interval time = A – B – C. A priori, the nCRT-surgery interval time was categorized as <6 weeks, 6–8 weeks, and >8 weeks, based on current clinical practice of a 6–8 week interval. Patients with a short interval of <6 weeks were categorized separately in order to avoid artificially biasing the estimate for patients with an interval of >8 weeks. In a sensitivity analysis, patients in the <6 week group were excluded from the sample and the main analysis was repeated. Since these results were consistent with the first analysis, we present the results of the analysis that includes this group since they represented 25% of the cohort.

Measurement of pCR

The primary endpoint was pCR (ypT0N0). NCDB does not contain an explicit variable for pCR but contains individual variables for pathologically determined tumor size and/or extension (14) and pathologically determined absence, presence, or extent of regional lymph node metastasis (pN). Patients with pT0 and pN0 were defined as having a pCR and all others were defined as not having a pCR.

Main Analyses

Chi-square tests and ANOVA as appropriate to the data were used to compare covariate distributions between the two outcome groups and the three nCRT-surgery interval time groups. A priori, patient, hospital and treatment characteristics that achieved a p–value <0.20 in bivariate analyses were included in multivariable analyses. These characteristics include age, sex, race, insurance status, education, income, metro/urban residence, facility location, facility type, facility volume, clinical stage, histology type, radiation dose, treatment regimen, and tumor size. Logistic regression models were used to assess the association between nCRT-surgery interval time and the odds of having pCR. Interaction terms were added to the multivariable logistic model (nCRT-surgery interval time*dose and nCRT-surgery interval time*treatment regimen) to assess for heterogeneity of the effect of the nCRT-surgery interval time for different levels of radiation dosage and treatment regimen. The p–values for both of the interaction terms were not statistically significant and thus were left out of the final model. All multivariable models used the propensity score method in order to adjust for selection effects of the observational dataset. The propensity score is the probability of being in an interval group given the covariates in the model. It was estimated using a multivariable multinomial logistic regression model and included as a covariate in all models.

In an attempt to identify a more specific nCRT-surgery interval time associated with the highest odds of pCR, a separate analysis was conducted in which patients were categorized into weekly interval groups (<6 weeks, 6–8 weeks, 8–9 weeks, 9–10 weeks, etc.). A separate multivariable logistic regression model was used to assess the relationship between this new interval variable and odds of pCR.

Secondary Analyses

A series of analyses were conducted to determine if there was an association between nCRT-surgery interval time and several secondary outcomes. Multivariable logistic regression models were used to estimate the effect of nCRT-surgery interval time on 30-day mortality, 30-day unplanned readmission and tumor downstaging (pT<cT or pN <cN vs. no downstaging). An ordinal logistic regression model was used to assess the association between tumor regression grade (pCR, moderate response, minimal response, poor response) and nCRT-surgery interval time. All analyses were performed using SAS software, version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). The study was considered exempt by the University of Rochester institutional review board, as it did not involve human subjects according to federal regulations (IRB #00051935).

Results

Of the 17,255 patients with stage II or III rectal cancer, 6,629 (38%) included in this study had a nCRT-surgery interval time greater than 8 weeks. Table 1 presents bivariate associations between covariates and the three nCRT-surgery interval time exposure groups. The mean nCRT-surgery interval time was 56.8 days. The proportion of pCR was 13.2% for those with a nCRT-surgery interval time of >8 weeks, 11.7% for those with a nCRT-surgery interval time of 6–8 weeks, and 8.7% for those with a nCRT-surgery interval time of <6 weeks (p-value <0.001).

Table 1.

Patient, Hospital and Pathological Characteristics between Neoadjuvant Chemoradiotherapy-Surgery Interval Time Groups

| Characteristic | Interval 6 – 8 wk, n=6629 | Interval <6 wk, n=3786 | Interval >8 wk, n=6500 | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y, mean ± SD | 59.5 ± 12.2 | 59.1 ± 12.3 | 60.3 ± 12.4 | <0.001 |

| Sex, n (%) | 0.482 | |||

| Male | 4,129 (62.3) | 2,362 (62.4) | 3,991 (61.4) | |

| Female | 2,500 (37.7) | 1,424 (37.6) | 2,509 (38.6) | |

| Race/ethnicity, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| White | 5,818 (88.4) | 3,323 (88.3) | 5,540 (85.9) | |

| Black | 463 (7.0) | 286 (7.6) | 591 (9.2) | |

| Native American | 31 (0.5) | 19 (0.5) | 26 (0.4) | |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 224 (3.4) | 112 (3.0) | 261 (4.0) | |

| Other | 45 (0.7) | 23 (0.6) | 34 (0.5) | |

| Primary payer, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Private | 3,590 (54.7) | 2,060 (54.9) | 3,152 (49.1) | |

| Not Insured | 302 (4.6) | 161 (4.3) | 376 (5.9) | |

| Medicaid | 394 (6.0) | 208 (5.5) | 499 (7.8) | |

| Medicare | 2,201 (33.5) | 1,277 (34.0) | 2,307 (36.0) | |

| Veterans Affairs/military | 81 (1.2) | 44 (1.2) | 81 (1.3) | |

| Average income, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| <$30,000 | 755 (12.0) | 489 (13.6) | 776 (12.7) | |

| $30,000 – $35,000 | 1,216 (19.3) | 738 (20.5) | 1,100 (18.0) | |

| $35.000 – $46,000 | 1,777 (28.2) | 1,062 (29.5) | 1,746 (28.6) | |

| >$46,000 | 2,548 (40.5) | 1,311 (36.4) | 2,482 (40.7) | |

| Average education (not finishing high school), n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| ≥ 29% | 938 (14.9) | 623 (17.3) | 1016 (16.6) | |

| 20% – 28.9% | 1,473 (23.4) | 910 (25.3) | 1,365 (22.4) | |

| 14% – 19.9% | 1,638 (26.0) | 869 (24.1) | 1,547 (25.3) | |

| < 14% | 2,246 (35.7) | 1,198 (33.3) | 2,176 (35.6) | |

| Population density, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Metro/adjacent | 6,178 (93.2) | 3,488 (92.1) | 6,150 (94.6) | |

| Rural | 451 (6.8) | 298 (7.9) | 350 (5.4) | |

| Comorbidity, n (%) | 0.100 | |||

| 0 | 5,308 (80.1) | 3,002 (79.3) | 5,156 (79.3) | |

| 1 | 1,102 (16.6) | 629 (16.6) | 1,073 (16.5) | |

| ≥2 | 219 (3.3) | 155 (4.1) | 271 (4.2) | |

| Hospital type, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Academic | 2,540 (38.3) | 1,104 (29.2) | 2,698 (41.5) | |

| Community | 533 (8.0) | 431 (11.4) | 491 (7.5) | |

| Comprehensive | 3,519 (53.1) | 2,228 (58.9) | 3,282 (50.5) | |

| Other | 37 (0.6) | 23 (0.6) | 29 (0.4) | |

| Hospital location, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Northeast | 440 (6.6) | 252 (6.7) | 375 (5.8) | |

| Atlantic | 979 (14.8) | 420 (11.1) | 1,084 (16.7) | |

| Southeast | 1,379 (20.8) | 897 (23.7) | 1,334 (20.5) | |

| Great Lakes | 1,367 (20.6) | 738 (19.5) | 1,358 (20.9) | |

| South | 402 (6.1) | 272 (7.2) | 304 (4.7) | |

| Midwest | 772 (11.6) | 415 (11.0) | 629 (9.7) | |

| West | 384 (5.8) | 290 (7.7) | 378 (5.8) | |

| Mountain | 231 (3.5) | 182 (4.8) | 198 (3.0) | |

| Pacific | 675 (10.2) | 320 (8.4) | 840 (12.9) | |

| Rectal cancer cases/y, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| 0 – 10 | 779 (11.7) | 639 (16.9) | 782 (12.0) | |

| 11 – 30 | 2,922 (44.1) | 1,885 (49.8) | 2,722 (41.9) | |

| >30 | 2,928 (44.2) | 1,262 (33.3) | 2,996 (46.1) | |

| Clinical stage, n (%) | 0.010 | |||

| II | 3,156 (47.6) | 1,915 (50.6) | 3,122 (48.0) | |

| III | 3,473 (52.4) | 1,871 (49.4) | 3,378 (52.0) | |

| Histology, n (%) | 0.179 | |||

| Adenocarcinoma | 6,151 (92.8) | 3,477 (91.8) | 6,050 (93.1) | |

| Mucinous | 430 (6.5) | 281 (7.4) | 401 (6.2) | |

| Signet ring cell | 48 (0.7) | 28 (0.7) | 49 (0.7) | |

| Radiation dose, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| ≥45 Gy | 6,395 (96.5) | 3,570 (94.3) | 6,128 (94.3) | |

| <45 Gy | 234 (3.5) | 216 (5.7) | 372 (5.7) | |

| Chemo regimen, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| RT + 1 agent | 3,482 (56.6) | 1,817 (53.7) | 3,529 (60.1) | |

| RT + 2 agents | 2,664 (43.4) | 1,568 (46.3) | 2,339 (39.9) | |

| Tumor size, mm, n (%) | 0.03 | |||

| 0 – 25 | 2,915 (43.4) | 1,735 (44.2) | 2,840 (43.0) | |

| 25 – 40 | 1,736 (25.9) | 980 (24.9) | 1,592 (24.1) | |

| 40 – 50 | 860 (12.8) | 482 (12.3) | 934 (14.1) | |

| >50 | 1,203 (17.9) | 733 (18.7) | 1,245 (18.8) | |

| Year of diagnosis, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| 2006 | 757 (11.4) | 553 (14.6) | 538 (8.3) | |

| 2007 | 890 (13.4) | 613 (16.2) | 719 (11.1) | |

| 2008 | 1,103 (16.6) | 736 (19.4) | 880 (13.5) | |

| 2009 | 1,166 (17.6) | 628 (16.6) | 1,151 (17.7) | |

| 2010 | 1,357 (20.5) | 632 (16.7) | 1,542 (23.7) | |

| 2011 | 1,356 (20.5) | 624 (16.5) | 1,670 (25.7) |

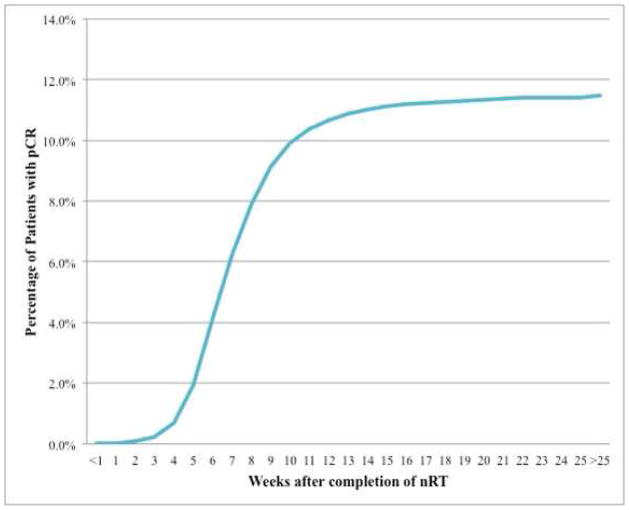

Tables 2 and 3 show bivariate associations between pCR and patient characteristics as well as tumor/treatment characteristics respectively. The proportion of patients experiencing pCR was then assessed by week following completion of neoadjuvant therapy and plotted against the cumulative proportion of pCR by week as seen in Figure 2. The cumulative pCR rate appeared to peak between 10–11 weeks (Figure 2).

Table 2.

Bivariate Analysis of Patient and Hospital Characteristics by Overall Pathological Complete Response Status

| Characteristic | pCR n=1,983 (11.5%) | No pCR n=15,272 (88.5%) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y, mean±SD | 60.2 ± 12.5 | 59.8 ± 12.4 | 0.11 |

| Sex, n (%) | 0.005 | ||

| Male | 1,169 (11.0) | 9,505 (89.0) | |

| Female | 814 (12.4) | 5,767 (87.6) | |

| Race/ethnicity, n (%) | 0.047 | ||

| White | 1,747 (11.7) | 13,231 (88.3) | |

| Black | 131 (9.6) | 1,230 (90.4) | |

| Native American | 11 (13.7) | 69 (86.3) | |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 78 (12.8) | 532 (87.2) | |

| Other | 6 (5.9) | 96 (94.1) | |

| Primary payer, n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| Private | 1,056 (11.8) | 7,863 (88.2) | |

| Not insured | 60 (7.0) | 792 (93.0) | |

| Medicaid | 91 (8.2) | 1,023 (91.8) | |

| Medicare | 726 (12.2) | 5,243 (87.8) | |

| Other government | 30(14.2) | 182 (85.8) | |

| Average income, n (%) | 0.073 | ||

| <$30,000 | 214 (10.4) | 1,853 (89.6) | |

| $30,000 – $35,000 | 348 (11.1) | 2,793 (88.9) | |

| $35,000 – $46,000 | 527 (11.3) | 4,133 (88.7) | |

| >$46,000 | 791 (12.3) | 5,665 (87.7) | |

| Average education (not finishing high school), n (%) | 0.005 | ||

| ≥29% | 259 (9.9) | 2,363 (90.1) | |

| 20% – 28.9% | 434 (11.3) | 3,395 (88.7) | |

| 14% – 19.9% | 469 (11.3) | 3,676 (88.7) | |

| <14% | 717 (12.5) | 5,010 (87.5) | |

| Population density, n (%) | 0.223 | ||

| Metro/adjacent | 1,865 (11.6) | 14,253 (88.4) | |

| Rural | 118 (10.4) | 1,019 (89.6) | |

| Comorbidity, n (%) | 0.819 | ||

| 0 | 1,565 (11.4) | 12,144 (88.6) | |

| 1 | 338 (11.8) | 2,537 (88.2) | |

| ≥2 | 80 (11.9) | 591 (88.1) | |

| Hospital type, n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| Academic | 814 (12.6) | 5,648 (87.4) | |

| Community | 118 (7.9) | 1,374 (92.1) | |

| Comprehensive | 1,043 (11.3) | 8,169 (88.7) | |

| Other | 8 (91.0) | 81 (9.0) | |

| Hospital location, n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| Northeast | 119 (10.9) | 976 (89.1) | |

| Atlantic | 311 (12.3) | 2,211 (87.7) | |

| Southeast | 374 (10.2) | 3,288 (89.8) | |

| Great Lakes | 431 (12.3) | 3,074 (87.7) | |

| South | 106 (10.6) | 897 (89.4) | |

| Midwest | 258 (13.7) | 1,631 (86.3) | |

| West | 100 (9.3) | 977 (90.7) | |

| Mountain | 55 (8.9) | 565 (8.9) | |

| Pacific | 229 (12.2) | 1,653 (12.2) |

pCR, pathological complete response.

Table 3.

Bivariate Analysis of Tumor/Treatment Characteristics by Overall Pathological Complete Response Status

| Characteristic | pCR, n=1,983 | No pCR, n=15,272 | p Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | ||

| nCRT to surgery interval, wk | <0.001 | ||||

| 6 – 8 | 775 | 11.7 | 5854 | 88.3 | |

| < 6 | 329 | 8.7 | 3457 | 91.3 | |

| > 8 | 855 | 13.2 | 5645 | 86.8 | |

| Annual rectal cancer cases, mean | <0.0001 | ||||

| 0 – 10 | 188 | 8.5 | 2012 | 91.5 | |

| 11 – 30 | 817 | 10.8 | 6712 | 89.2 | |

| > 30 | 954 | 13.3 | 6232 | 86.7 | |

| Clinical stage | 0.001 | ||||

| II | 1,037 | 12.3 | 7,364 | 87.7 | |

| III | 946 | 10.7 | 7,908 | 89.3 | |

| Histology | <0.001 | ||||

| Adenocarcinoma | 1,955 | 12.2 | 14,040 | 87.8 | |

| Mucinous | 16 | 1.4 | 1,114 | 98.6 | |

| Signet ring cell | 12 | 9.2 | 118 | 90.8 | |

| Radiation dose, Gy | 0.005 | ||||

| ≥ 45 | 1,904 | 11.6 | 14,433 | 88.4 | |

| < 45 | 79 | 8.6 | 839 | 91.4 | |

| Chemo regimen | <0.0001 | ||||

| RT + 1 agent | 1129 | 12.8 | 7699 | 87.2 | |

| RT + 2 agents | 672 | 10.) | 5899 | 89.8 | |

| Tumor size, mm | <0.0001 | ||||

| 0 – 25 | 962 | 12.8 | 6528 | 87.2 | |

| 25 – 40 | 494 | 11.5 | 3814 | 88.5 | |

| 40 – 50 | 246 | 10.8 | 2030 | 89.2 | |

| > 50 | 281 | 8.8 | 2900 | 91.2 | |

| Year of diagnosis | <0.0001 | ||||

| 2006 | 174 | 9.2 | 1709 | 90.8 | |

| 2007 | 234 | 10.3 | 2,028 | 89.7 | |

| 2008 | 276 | 9.9 | 2,506 | 90.1 | |

| 2009 | 357 | 11.9 | 2,654 | 88.1 | |

| 2010 | 429 | 11.9 | 3,165 | 88.1 | |

| 2011 | 513 | 13.8 | 3,210 | 86.2 | |

pCR, pathological complete response; nCRT, neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy; RT, radiotherapy.

Figure 2.

Cumulative proportion of pathological complete response by interval week.

Table 4 presents results from the multivariable logistic regression analyses. A nCRT-surgery interval time >8 weeks was associated with 12% higher odds of pCR as compared to those who had an interval time of 6–8 weeks (Odds Ratio (OR): 1.12 (95% Confidence Interval (CI): 1.01 – 1.25). An interval time of <6 weeks was associated with lower odds of pCR (OR = 0.77, 95% CI =0.66 – 0.89). Patients with no insurance (OR =0.60, 95% CI=0.44 – 0.80) and Medicare (OR = 0.67, 95% CI=0.52 – 0.85) had a lower odds of pCR. It is interesting to note that the odds of pCR increased over time. Furthermore, increasing tumor size was associated with a higher odds of pCR. In addition, high volume hospitals had a higher odds of pCR (OR = 1.42, 95%CI=1.12 – 1.80). In the comparison of weekly interval groups, results indicated that the optimal time window was 10–11 weeks as compared to 6–8 weeks (OR = 1.27, 95% CI=1.01 – 1.60).

Table 4.

Binary Logistic Regression, Factors Associated with Pathological Complete Response

| Characteristic | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | p Value |

|---|---|---|

| nCRT to surgery interval, wk | ||

| 6 – 8 | Reference | |

| < 6 | 0.79 (0.68–0.91) | 0.0009 |

| > 8 | 1.12 (1.02 – 1.28) | 0.04 |

| Rectal cancer resections annually, n | ||

| 1 – 10 | Reference | |

| 11 – 30 | 1.20 (0.95–1.51) | 0.12 |

| ≥ 30 | 1.42 (1.12–1.80) | 0.004 |

| Treatment regimen | ||

| RT, 1 chemo agent | Reference | |

| RT, ≥2 chemo agents | 0.76 (0.68–0.85) | <0.0001 |

| Radiation dose, Gy | ||

| <45 | Reference | |

| ≥ 45 | 1.28 (0.99. 1.65) | <0.06 |

| Histology | ||

| Adenocarcinoma | Reference | |

| Mucinous | 0.13 (0.08–0.22) | <0.001 |

| Signet ring cell | 0.78 (0.42–1.47) | 0.45 |

| Clinical stage | ||

| II | Reference | |

| III | 0.87 (0.78–0.96) | 0.008 |

| Tumor size, mm | ||

| 0 – 25 | Reference | |

| 25 – 40 | 1.14 (1.01, 1.28) | 0.04 |

| 40 – 50 | 1.18 (1.02, 1.38) | 0.03 |

| >50 | 1.43 (1.24, 1.66) | <0.0001 |

| Female sex | 1.22 (1.10–1.36) | 0.0002 |

| Primary payer | ||

| Private | Reference | |

| Not Insured | 0.60 (0.44–0.80) | 0.005 |

| Medicaid | 0.67 (0.52–0.85) | 0.001 |

| Medicare | 1.03 (0.89–1.19) | 0.74 |

| Other government | 1.22 (0.78–1.92) | 0.38 |

| Year of diagnosis | ||

| 2006 | Reference | |

| 2007 | 1.11 (0.88–1.39) | 0.40 |

| 2008 | 1.05 (0.84–1.31) | 0.66 |

| 2009 | 1.28 (1.04–1.59) | 0.02 |

| 2010 | 1.31 (1.07–1.62) | 0.01 |

| 2011 | 1.56 (1.28–1.92) | <0.001 |

Model also controlled for age, race, average income and education by zip code, hospital type and hospital location.

OR, odds ratio; nCRT, neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy; RT, radiotherapy.

Longer nCRT-surgery interval time was not associated with odds of 30-day mortality (OR: 1.13, 95% CI=0.76 – 1.69) or tumor regression grade (OR: 1.02, 95% CI=0.95 – 1.18), but was associated with higher odds of tumor downstaging (OR: 1.11, 95% CI= 1.02 – 1.25) and lower odds of unplanned 30-day readmission (OR: 0.82, 95% CI: 0.70 – 0.92).

Discussion

It is well established that neoadjuvant therapy should be deployed in appropriate patients with locally advanced rectal cancer. In the midst of significant practice variation in the timing between neoadjuvant radiotherapy and surgery, the 1999 Lyon R90-01 trial compared a 2-week vs. 6-week RT-surgery interval. This trial demonstrated improved clinical tumor response (72% vs. 53%) and more frequent histologic tumor regression (26% vs. 10%), effectively establishing six weeks as the standard RT-surgery interval.(7) However, recent literature has suggested a link between longer nCRT-surgery duration and increased proportion of patients experiencing pCR, but subsequent conclusions regarding the optimal length of time between nCRT completion and surgery have varied.(11) Kalady et al found that an interval ≥8 weeks between neoadjuvant treatment completion and surgical resection was associated with a higher rate of pCR. Additionally, this was correlated with decreased local recurrence and better overall survival.(15) Sloothaak et al showed that surgical resection 15–16 weeks after the start of neoadjuvant radiation (approximately 10 weeks after completion) was independently associated with a higher rate of pCR (18%). In contrast, although some studies have reported an increase in pCR with a longer nCRT-surgery interval, others have reported no effect of an increased interval on pCR.(16)

In the present study, several patient factors were associated with differences in pCR. Patients with Medicaid and no insurance coverage were noted to have a lower rate of pCR than patients with private insurance. This finding may indicate that patients with private health insurance receive more optimal care with fewer treatment interruptions, but this apparent disparity merits further inquiry as for example it may simply represent a surrogate marker for superior health performance status.(17, 18) While our analysis controlled for comorbidity index and clinical stage, one should not be too quick to draw direct conclusions from this finding given the observational nature of the data. Also, an increased odds of pCR was observed over time. However this may be driven largely by a more recent willingness of providers to recommend a longer nCRT-surgery interval as 46% of patients had a nCRT-surgery interval of >8 weeks in 2011 compared to just 29% of patients in 2006.

Perhaps not surprisingly, increased hospital volume of rectal cancer resections was associated with an independent increase in pCR. This association was similar in strength to that of a nCRT-surgery interval greater than eight weeks. To our knowledge, this is the first time such an effect has been described in relation to pCR. This result suggests that there may be a comprehensive effect from an institution in which various members of the treatment team such as surgery, medical and radiation oncology, nursing and other providers are familiar with the workup and treatment of this disease process. This finding may further support the implementation of a national accreditation program for the perioperative management of patients with rectal cancer.

The present study examined the relationship between a longer interval from neoadjuvant radiation to surgical resection and pCR in patients with clinical stage II and III rectal cancer. The overall proportion of patients with pCR was 11.5%, which is on the lower end of the range of the 8.4 – 22.0% previously reported.(11) It is not surprising to find lower unadjusted rates of pCR in this cohort, as it is comprised of patients with tumors or various histological subtypes that have undergone neoadjuvant therapy regimens that may be incomplete. This wide range of reported rates is likely reflective of heterogeneous patient populations receiving different treatment regimens including varying times between neoadjuvant therapy and surgical resection.

This study shows that patients with a nCRT-surgery interval greater than 8 weeks had a small but real increase in the odds of pCR compared to those with an interval between 6 and 8 weeks. To further explore this association, the effect of the nCRT-surgery interval by week was examined. When examining cumulative proportion of pCR by week, a consistent increase in pCR between four and eleven weeks was seen, followed by a leveling-off around ten to eleven weeks. This finding was in accordance with the work of Kalady et al.(15) In addition, patients who had a nCRT-surgery time of six to eight weeks were compared to each subsequent week in order to determine if there was an optimal waiting period. These results show that patients who had a nCRT-surgery interval of ten to eleven weeks had 27% greater odds of pCR than those with an interval of six to eight weeks, which was consistent with the unadjusted results.

However, one must recognize that the histological response of a tumor to neoadjuvant radiation is not all or nothing, but rather exists along a continuum from no response to pCR, although it is typically measured as a categorical measure. This study also found an increased number of patients with tumor downstaging in the longer interval group. This finding is potentially important for both short-term and long-term oncologic outcomes. Obviously, tumor downstaging increases the chances of an R0 resection. In addition, tumor response as measured by tumor regression grade and downstaging has also been shown to increase overall and recurrence-free survival in locally advanced rectal cancer.(19–23) However, despite the results of these prior studies, one should acknowledge the imprecision of clinical T and N staging and as a result, tumor downstaging should not be weighted as strongly as our other outcomes.

It is important to acknowledge the limitations of the current study. First, we have limited data about the exact treatment regimen of individual patients, such as specific chemotherapy agents, dose reductions, treatment breaks or incomplete regimens. Additionally, we have limited information about surgical complications and no long-term mortality information. Also, other factors, such as intolerance to neoadjuvant therapy or resulting treatment toxicity, could result in truncated treatment and potentially decreased pCR. Furthermore, we have no data on whether patients underwent reassessment at 6–8 weeks post completion of neoadjuvant therapy, which may have influenced the decision to increase the treatment interval. The higher proportion of patients with pCR in the >8 week group may be, at least in part, because of this. As we do not know the reason for surgeon decision-making regarding longer intervals, some selection bias may be affecting the results.

It is now the practice of some surgeons to extend the interval to surgery if the patient exhibits endoscopic and/or radiological evidence of a tumor response. Some centers are utilizing PET/CT as an additional tool for interval assessment of tumor response.(24) Such a policy of interval assessment may allow for the identification of patients who have demonstrated a mucosal response to neoadjuvant therapy based on endoscopy supplemented by radiological reassessment. Clearly, such patients are manifesting a good response to neoadjuvant therapy and could be allocated to a treatment path that involves a longer time period post neoadjuvant therapy to maximize tumor response. Ultimately, some of these patients may meet the criteria for a complete clinical response that at least allows the opportunity to consider an organ preservation strategy (so-called watch and wait strategy).(25) Conversely, patients who do not manifest any significant endoscopic or radiological response on interval assessment at 6–8 weeks post completion of neoadjuvant therapy are not going to benefit from a longer duration post completion and should be scheduled for surgical resection. Such a policy recognizes the heterogeneity in treatment response amongst patients following neoadjuvant therapy allowing responders to maximize the benefit from treatment while routing patients who have not responded to resection, as they will not benefit from a longer time interval.

When interpreting the encouraging data from this study, one must acknowledge that only a randomized trial can definitively answer whether a longer interval post neoadjuvant therapy results in improved tumor response and ultimately complete response. In addition, such a study will allow for a more thorough assessment of the safety of patients with extended intervals. A few trials pursuing this aim are currently accruing patients.(26–29) However it appears that clinical practice already appears to be shifting towards a longer duration to surgery, especially in high volume centers. This is of particular interest when considering the emerging role of non-operative observational strategies currently being offered to select patients with complete clinical response, and the randomized trial currently investigating the role of this strategy.(30) However, the issue of local recurrence is intimately tied to an observational strategy. Habr-Gama et al recently reported that local recurrence can occur in up to 31% of patients with initial cCR, but salvage therapy is possible in ≥90% of recurrences. The patients in that study ultimately had 94% disease control and 78% organ preservation.(31)

It is certainly important to note that increasing the nCRT-surgery interval will lead to a delay in systemic adjuvant therapy, which could have implications for systemic disease recurrence and overall survival. To this end, randomized trials are exploring the role of systemic chemotherapy in the neoadjuvant period.(32, 33) This is of particular importance since a large proportion of rectal cancer patients die of metastatic disease, so optimizing systemic therapy is key. Furthermore, the addition of systemic therapy or novel agents to the neoadjuvant period could increase pCR. In addition, follow-up from these trials will be useful in determining whether patients with longer nCRT-surgery interval experienced a higher incidence of distant recurrence.

Notwithstanding these limitations, our study does have a number of strengths. It is by far the largest study to date to address the relationship of nCRT-surgery interval and subsequent pCR. It is important to note that this database represents the majority of patients diagnosed and treated for rectal cancer in the US. Also, the robust level of oncologic and treatment information in this database overcomes some weaknesses of many administrative billing datasets.

Conclusions

In summary, with the largest and most direct examination of this topic to date, we have observed that a nCRT-surgery interval of greater than eight weeks is independently associated with an increased proportion of rectal cancer patients experiencing both pCR and tumor downstaging after neoadjuvant radiation. Our data suggest an optimal interval of 10–11 weeks with no observed impact on patient safety. This study also demonstrates that the association between longer intervals and increased pCR persists in a “real-world”, population-based sample of rectal cancer patients, not only in highly specialized centers with carefully defined patient cohorts. These data provide strong support for consideration of extending the duration to surgery following the completion of neoadjuvant therapy. Unquestionably, the issue of non-operative approach for patients with apparent complete clinical response remains controversial. It will clearly be some years before sufficient data are available to answer some of these questions with confidence. Having said that, this study strongly suggests that interval assessment of tumor response following neoadjuvant therapy to decide on an extended interval after neoadjuvant therapy should become the standard of care, allowing rational choices to be made between radical resection and potentially non-operative management.

Footnotes

Disclosure Information: Nothing to disclose.

Disclosures outside the scope of this work: Dr Wexner is a consultant for CareFusion, Edwards LifeSciences, GI View, Incontinence Devices Inc., Johnson & Johnson Medical, Karl Storz Endoscopy-America, Lexington Medical, LifeBond, Mederi Therapeutics, Medtronic, Novadaq, Precision Therapeutics, and Renew Medical. Dr Wexner holds patents and receives royalties from Covidien, Karl Storz Endoscopy-America, novoGI, and Unique Surgical Innovations. Dr Wexner has stock and stock options for Asana Medical, LifeBond, CRH Medical, EZ Surgical, Neatstitch, and novoGI. All other authors have nothing to disclose.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2013. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013 Jan;63(1):11–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fleming FJ, Pahlman L, Monson JR. Neoadjuvant therapy in rectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2011 Jul;54(7):901–12. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e31820eeb37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ricciardi R, Roberts PL, Read TE, et al. Who performs proctectomy for rectal cancer in the United States? Dis Colon Rectum. 2011 Oct;54(10):1210–5. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0b013e31822867a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stitzenberg KB, Sanoff HK, Penn DC, et al. Practice patterns and long-term survival for early-stage rectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2013 Dec 1;31(34):4276–82. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.49.1860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benson AB, 3rd, Bekaii-Saab T, Chan E, et al. Rectal cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2012 Dec 1;10(12):1528–64. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2012.0158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Monson JR, Weiser MR, Buie WD, et al. Practice parameters for the management of rectal cancer (revised) Dis Colon Rectum. 2013 May;56(5):535–50. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0b013e31828cb66c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Francois Y, Nemoz CJ, Baulieux J, et al. Influence of the interval between preoperative radiation therapy and surgery on downstaging and on the rate of sphincter-sparing surgery for rectal cancer: the Lyon R90-01 randomized trial. J Clin Oncol. 1999 Aug;17(8):2396. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.8.2396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bosset JF, Calais G, Mineur L, et al. Enhanced tumorocidal effect of chemotherapy with preoperative radiotherapy for rectal cancer: preliminary results--EORTC 22921. J Clin Oncol. 2005 Aug 20;23(24):5620–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gerard JP, Conroy T, Bonnetain F, et al. Preoperative radiotherapy with or without concurrent fluorouracil and leucovorin in T3-4 rectal cancers: results of FFCD 9203. J Clin Oncol. 2006 Oct 1;24(28):4620–5. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.7629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martin ST, Heneghan HM, Winter DC. Systematic review and meta-analysis of outcomes following pathological complete response to neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy for rectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2012 Jul;99(7):918–28. doi: 10.1002/bjs.8702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Foster JD, Jones EL, Falk S, et al. Timing of surgery after long-course neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy for rectal cancer: a systematic review of the literature. Dis Colon Rectum. 2013 Jul;56(7):921–30. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0b013e31828aedcb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bilimoria KY, Stewart AK, Winchester DP, Ko CY. The National Cancer Data Base: a powerful initiative to improve cancer care in the United States. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008 Mar;15(3):683–90. doi: 10.1245/s10434-007-9747-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Surgeons ACo. Facility Oncology Registry Data Standards. [Accessed January 7, 2014]. Available at. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abbas MA, Chang GJ, Read TE, et al. Optimizing rectal cancer management: analysis of current evidence. Dis Colon Rectum. 2014 Feb;57(2):252–9. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000000020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kalady MF, de Campos-Lobato LF, Stocchi L, et al. Predictive factors of pathologic complete response after neoadjuvant chemoradiation for rectal cancer. Ann Surg. 2009 Oct;250(4):582–9. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181b91e63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dolinsky CM, Mahmoud NN, Mick R, et al. Effect of time interval between surgery and preoperative chemoradiotherapy with 5-fluorouracil or 5-fluorouracil and oxaliplatin on outcomes in rectal cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2007 Sep 1;96(3):207–12. doi: 10.1002/jso.20815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim MJ, Park JS, Park SI, et al. Accuracy in differentiation of mucinous and nonmucinous rectal carcinoma on MR imaging. Journal of computer assisted tomography. 2003 Jan-Feb;27(1):48–55. doi: 10.1097/00004728-200301000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yu SK, Chand M, Tait DM, Brown G. Magnetic resonance imaging defined mucinous rectal carcinoma is an independent imaging biomarker for poor prognosis and poor response to preoperative chemoradiotherapy. European journal of cancer. 2014 Mar;50(5):920–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2013.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.de Campos-Lobato LF, Stocchi L, da Luz Moreira A, et al. Downstaging without complete pathologic response after neoadjuvant treatment improves cancer outcomes for cIII but not cII rectal cancers. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010 Jul;17(7):1758–66. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-0924-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Diaz-Gonzalez JA, Calvo FA, Cortes J, et al. Prognostic factors for disease-free survival in patients with T3-4 or N+ rectal cancer treated with preoperative chemoradiation therapy, surgery, and intraoperative irradiation. International journal of radiation oncology, biology, physics. 2006 Mar 15;64(4):1122–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Theodoropoulos G, Wise WE, Padmanabhan A, et al. T-level downstaging and complete pathologic response after preoperative chemoradiation for advanced rectal cancer result in decreased recurrence and improved disease-free survival. Dis Colon Rectum. 2002 Jul;45(7):895–903. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-6325-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Valentini V, Coco C, Picciocchi A, et al. Does downstaging predict improved outcome after preoperative chemoradiation for extraperitoneal locally advanced rectal cancer? A long-term analysis of 165 patients. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2002 Jul 1;53(3):664–74. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(02)02764-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wheeler JM, Dodds E, Warren BF, et al. Preoperative chemoradiotherapy and total mesorectal excision surgery for locally advanced rectal cancer: correlation with rectal cancer regression grade. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004 Dec;47(12):2025–31. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-0713-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Perez RO, Habr-Gama A, Sao Juliao GP, et al. Optimal timing for assessment of tumor response to neoadjuvant chemoradiation in patients with rectal cancer: do all patients benefit from waiting longer than 6 weeks? International journal of radiation oncology, biology, physics. 2012 Dec 1;84(5):1159–65. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2012.01.096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maas M, Beets-Tan RG, Lambregts DM, et al. Wait-and-see policy for clinical complete responders after chemoradiation for rectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011 Dec 10;29(35):4633–40. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.37.7176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. [Accessed July 13, 2014];The Stockholm III Trial on DIfferent Preoperative Radiotherapy Regimens in Rectal Cancer. Available at: http://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT00904813.

- 27.Cancer Research United Kingdom. [Accessed July 13, 2014];Treatment for rectal cancer. Available at: http://www.cancerresearchuk.org/cancer-help/trials/a-trial-looking-best-time-surgery-after-treatment-rectal-cancer.

- 28. [Accessed July 13, 2014];STARRCAT Trial: Surgical timing after radiotherapy for rectal cancer. Available at: http://www.controlled-trials.com/ISRCTN88843062.

- 29.Lefevre JH, Rousseau A, Svrcek M, et al. A multicentric randomized controlled trial on the impact of lengthening the interval between neoadjuvant radiochemotherapy and surgery on complete pathological response in rectal cancer (GRECCAR-6 trial): rationale and design. BMC cancer. 2013;13:417. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-13-417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Garcia-Aguilar J Center MSKC. Clinical Trials.gov. Bethesda (MD): National Library of Medicine (US); 2000. Trial Evaluating 3-year Disease Free Survival in Patients With Locally Advanced Rectal Cancer Treated With Chemoradiation Plus Induction or Consolidation Chemotherapy and Total Mesorectal Excision or Non-operative Management. [cited 2014 Nov 21]. Available from: http://www.cancer.gov/clinicaltrials/search/view?cdrid=755893&version=HealthProfessional NLM Identifier: NCT02008656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Habr-Gama A, Gama-Rodrigues J, Sao Juliao GP, et al. Local recurrence after complete clinical response and watch and wait in rectal cancer after neoadjuvant chemoradiation: impact of salvage therapy on local disease control. International journal of radiation oncology, biology, physics. 2014 Mar 15;88(4):822–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2013.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schrag D. Clinical Trials.gov. Bethesda (MD): National Library of Medicine (US); 2000. Oncology. AfCTi. Chemotherapy Alone or Chemotherapy Plus Radiation Therapy in Treating Patients With Locally Advanced Rectal Cancer Undergoing Surgery. [cited 2014 Nov 21]. Available from: http://www.cancer.gov/clinicaltrials/search/view?cdrid=715321&version=HealthProfessional NLM Identifier: NCT01515787. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schrag D, Weiser MR, Goodman KA, et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy without routine use of radiation therapy for patients with locally advanced rectal cancer: a pilot trial. J Clin Oncol. 2014 Feb 20;32(6):513–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.51.7904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]