Abstract

To investigate adolescent students' self-rated health status and to identify the influencing factors that affect students' health status. A stratified cluster sampling method and the Self-assessed General Health Questionnaires were used to enroll 503 adolescent students from Sichuan Province, Southwest part of China. Most adolescent students perceived their self-rated health as “Fair” (29.4%), “Good” (52.1%), or “Very Good” (16.3%). Regarding the sleep quality, most of them rated them as “Fair” (24.9%), “Good” (43.1%), or “Very Good” (19.7%), but 59.7% students reported to sleep less than 8 hours a day, even a few reported to sleep less than 6 hours (4.4%) or more than 9 hours (9.7%). A considerable number of students (41.1%) reported that they “Never” or just “Occasionally” participated in appropriate sports or exercises. As to the dietary habit, a significant number of students (15.7%) reported that they “Never” or “Occasionally” have breakfast. Students from different administrative levels of schools (municipal level, county level, and township level) rated differently (P < 0.05) in terms of their self-rated health, Health Behaviors, Sleeping, Dietary behaviors, Safety Awareness, and Drinking and Smoking behaviors. In general, Chinese teenage students perceived their own health status as fairly good. However, attention needs to be paid to health problems of some of the students, such as lack of sleep and exercise and inadequate dietary habits, etc. More concerns need to be addressed to students from different administrative levels of schools, and strategies should be put forward accordingly.

Keywords: adolescence, self-rated health, influencing factors

INTRODUCTION

One of the most intensively studied measures of health status is the self-rated health.1,2 Self-rated health has been commonly used for measuring physical health status, whereas the development of one's perception about self-rated health likely occurs during childhood and adolescence.3 Davies and Ware4 suggest that self-rated health is more likely a “state” than a “trait,” and they argue that person factors such as physical and mental health problems are the main determinants of the somewhat varying state of self-rated health. However, more scholars such as Bram & Claartje believe that self-rated health expresses how individuals view their health, taking into account physical, mental, and social aspects of health.5

Adolescence is a unique biological and psychosocial stage of human life cycle, distinct from both childhood and adulthood.6 Although adolescence is a relatively healthy time of life, it is also the time when behaviors can develop that may have long-term effects on adult health and well-being. The evolution of self-discovery in adolescence offers unique opportunities for them to access to life's possibilities. A good health is a necessary foundation for the future development for every adolescent.7 However, a significant proportion of adolescents experience some health-related issues such as tiredness and depression, and even long-term illnesses.8

The health status of adolescents has been highly recognized by different countries around the world and a considerable number of studies could be found in the literature. Studies carried out by the School Health Education Unit in the United Kingdom show that school-aged young people are likely to rate themselves as healthy. Approximately 81% of male and 71% of female students reported their health to be good in a Swedish High School, but these adolescents were considerably less physically active compared with those a decade ago.9 Most of them prefer to watch television and/or use the computer instead of participating in sports or physical activities.9 Taylor et al10 found that experiences related to participation in activity during childhood and adolescence may positively influence physical activity during adulthood.

In China, with the transformation of educational model from traditional examination-oriented education to quality-oriented education, the overall quality of youth, particularly their health condition is giving increased attention. Xiao Chen & Wang Qingyun did a survey study and the results showed a decline in the overall health and fitness of Chinese teenagers and demonstrates the need for more effective measures to help students develop healthy lifestyles.11 Approximately 51.0% and 9.8% of adolescents did not achieve optimal sleep duration (defined as <8.0 hours per day) on weekdays and on weekends in Chinese adolescents.12 The prevalence of overweight and obesity combined was 19.2% among children and adolescents aged 7–18 years in 2010, with a significant and continuous increase in the prevalence of obesity in children and adolescents in China.13 Physical inactivity is closely related to an increased risk of cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, osteoporosis, and certain types of cancer.14–17

It is the time for educators and health care professionals to address the health condition of adolescents in China today. It is particularly important in light of increasing recognition for their health status, which is crucial to their well-being later as an adult. This study addresses the issue by exploring the self-rated health of adolescent Chinese students and identifying some critical risk factors that may affect students' health status. In addition, the comparisons were also performed regarding adolescents' health status between different genders, ages, grades, and schools. Hopefully, the appropriate strategies could be developed to reduce the risk factors affecting health and to improve the self-rated health of adolescent students.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

The study was conducted in 6 junior and senior high schools from Sichuan province, the Southwest part of China. A stratified cluster sampling method was adopted to enroll 520 adolescent students from 6 middle schools, including 2 municipal, 2 county, and 2 township level schools. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) first-year and second-year students from junior and senior high schools, (2) students volunteered to participate the survey, (3) students were able to understand the content of questionnaire and willing to answer the listed questions. The exclusion criteria included the following: (1) the third-year students from either junior or senior high school are excluded because they were preparing for the high school or college entrance examinations and (2) students who were unwilling to participate the survey.

Survey questionnaires

The Self-assessed General Health Questionnaires (SAGHQ) were used as the study instruments. The SAGHQ was developed by a research team after an intensive review of the literature, and it aims to measure the self-rated health of adolescents for Chinese students and identifying some critical factors that may affect the students' assessment of their health status. The SAGHQ has 56 items, under 8 dimensions, including: Self-rated health, Health promoting behaviors, Sports and exercise, Sleeping, Dietary habit, Safety awareness, Drinking, Smoking, Internet, and Games. Students were asked to rate the degree of their agreement with each statement on a Likert scale, ranging from 1 = Never to 5 = Always. High scores on the scale illustrated a high level of compatibility. The scale was also pilot tested among 30 students and the final modifications were made based on experts' opinions and pilot-tested students' suggestions. The Cronbach alpha was 0.724 for the scales.

Data collection

All investigators in the survey have received unified training. A brief introduction to the questionnaire informed participates of the institution of the researchers, the purpose of the study, the confidentiality of information with no right or wrong answers, no consequences on their study results. They were asked to consider their responses based their own life. Data were collected from March to June 2014. All participates answered the questionnaires independently and anonymously at their own classrooms, and were encouraged to drop the questionnaires into a box at the back of their classroom. A total of 520 questionnaires were distributed, 503 of them were collected and checked to be valid questionnaires, accounting for 96.7% of the total.

Statistical analysis

The SPSS version 18.0 was used for data analysis in this study. The descriptive statistics were used to describe the characteristics of the study participants, and the analysis of variances was geared to analyze the self-rated health status among different ages, grades, and schools, etc.

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Committee, Sichuan University. Administrative supports were also granted from the headmasters of 6 middle schools. The students and their parents were informed about the study purposes and processes before the beginning of the study, and were assured of anonymity and confidentiality before verbally agreeing to take part. Verbal informed consent was obtained from each participant and their parents, because some of their adolescents' parents were immigrate workers outside the province. Students or their parents had the right to quit the study anytime without any comment or penalty.

RESULTS

Basic characteristics of the surveyed students

A total of 503 students were surveyed in this research. Among those, 228 were males (45.33%), 275 were females (54.67%); 186 (36.98%) were from junior high schools, and 317 (63.02%) from senior high schools. The average age for the surveyed students was 14.84 ± 2.023 years; the average age for students in junior high schools was 12.45 ± 0.900 years, and for students in senior high schools it was 16.24 ± 0.824 years. Regarding the administrative levels of school, 78 students (15.5%) were from municipal level schools, 144 were from county schools (28.6%), and 281 were from rural or township level schools (55.9%).

Self-rated health status

The students' average height (cm) was 160.25 ± 8.531 and body weight (kg), 48.59 ± 10.61. In terms of self-rated health, 1 (0.2%) rated “Very Poor,” 10 (2%) rated “Poor,” 148 (29.4%) rated “Fair,” 262 (52.1%) rated “Good,” and 82 (16.3%) believed that they had “Very Good” health.

Sleeping

In terms of the sleep quality, the numbers of students who reported as “Very Poor” to “Very Good” were as follows: 19 (3.8%), Very Poor; 43 (8.5%), Poor; 125 (24.9%), Fair; 217 (43.1%), Good; and 99 (19.7%), Very Good. Regarding the sleeping hours, 59.7% students reported to sleep less 8 hours a day, even a few reported to sleep less than 6 hours (4.4%) or more than 9 hours (9.7%).

Sports and exercise

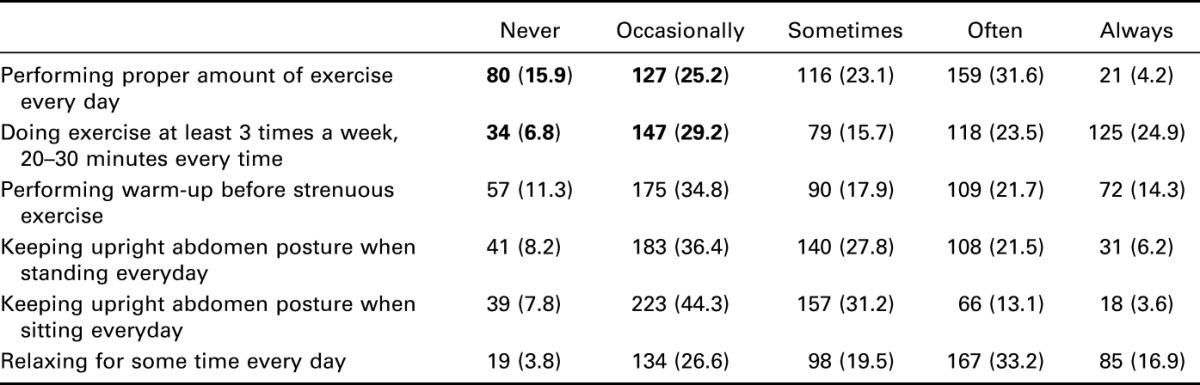

Exercising or participating in sports programs are keys to teenage students' health. Table 1 presents the data regarding the numbers of students who reported their engagement in sports and exercises. As listed, 80 students (15.9%) reported that they had “Never” performed proper amount of exercise every day, and 127 students (25.2%) reported that they had just “Occasionally” performed proper amount of exercise per day. A considerable numbers of students (181, 36%) reported that they had “Never” or just “Occasionally” taken exercises at least 3 times a week, 20–30 minutes every time (Table 1).

Table 1.

Engagement in sports and exercises of adolescent students (N = 503).

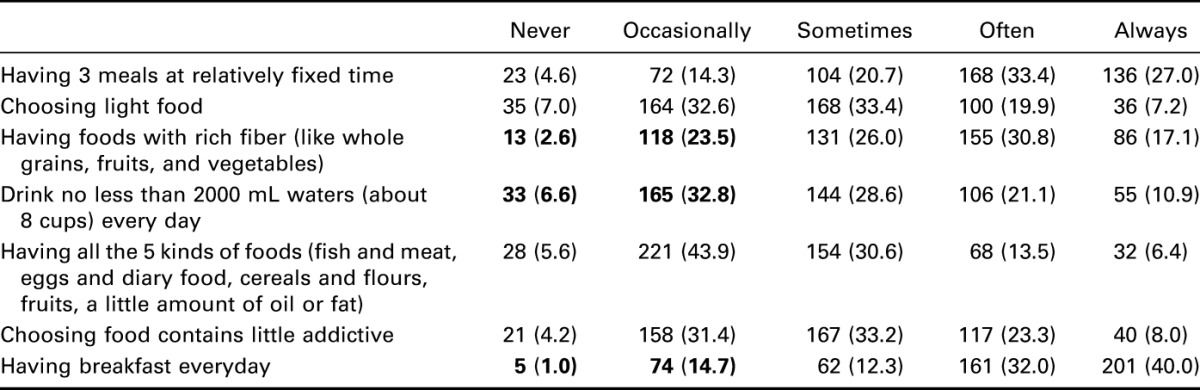

In term of dietary habit, nearly a quarter (131, 26.1%) of students reported “Never” or just “Occasionally” having foods with rich fibers; more than one-third (198, 39.4%) of students reported not drinking enough water per day, a significant number of students (79, 15.7%) reported that they “Never” or “Occasionally” have breakfast (Table 2).

Table 2.

Dietary habit of adolescent students (N = 503).

Health promotion behaviors

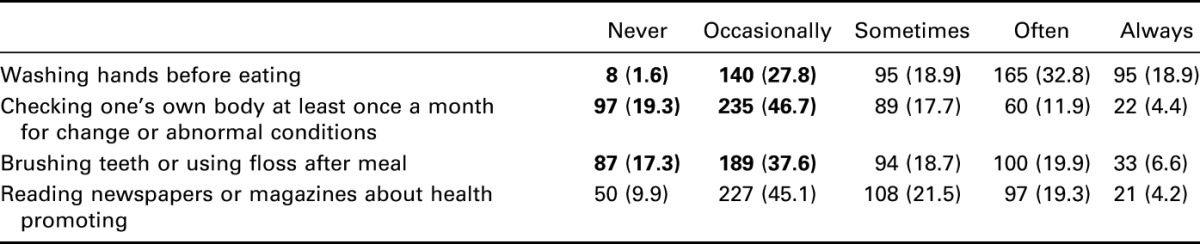

In terms of health promotion behaviors, nearly one-third of adolescent students (148, 29.4%) reported “Never” or just “Occasionally” washed hands before eating; almost two-third of students (332, 66.0%) reported “Never” or just “Occasionally” checked their body once a month for change or abnormal conditions; and more than half (296, 54.9%) stated that they had “Never” or just “occasionally” brushed teeth or used floss after meal (Table 3).

Table 3.

Health promotion behaviors of adolescent students (N = 503).

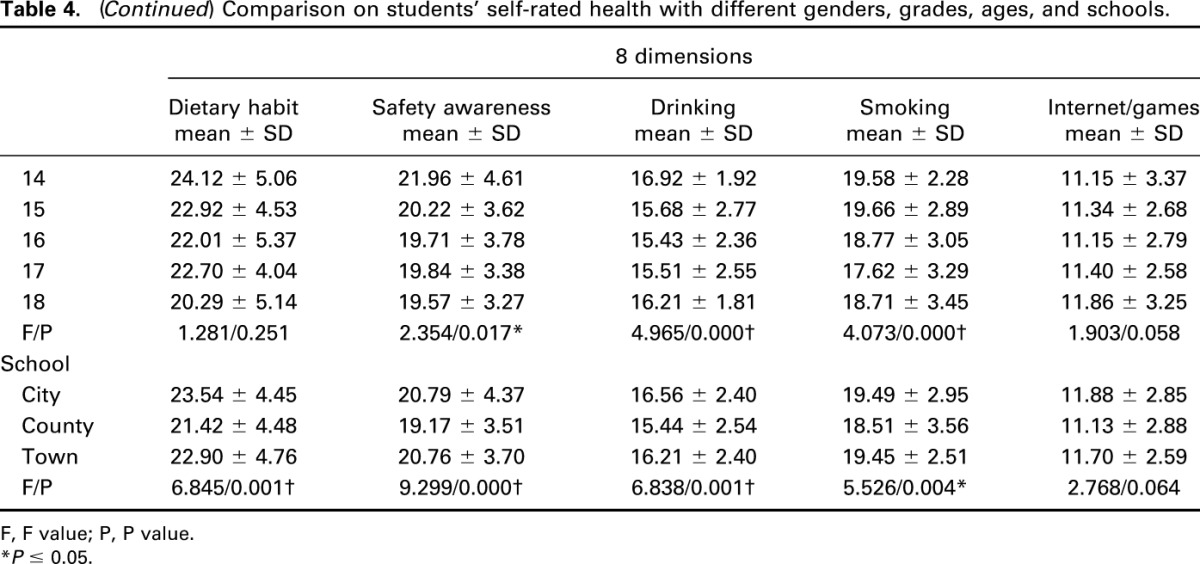

Comparison on students' health status with different genders, grades, ages, and schools

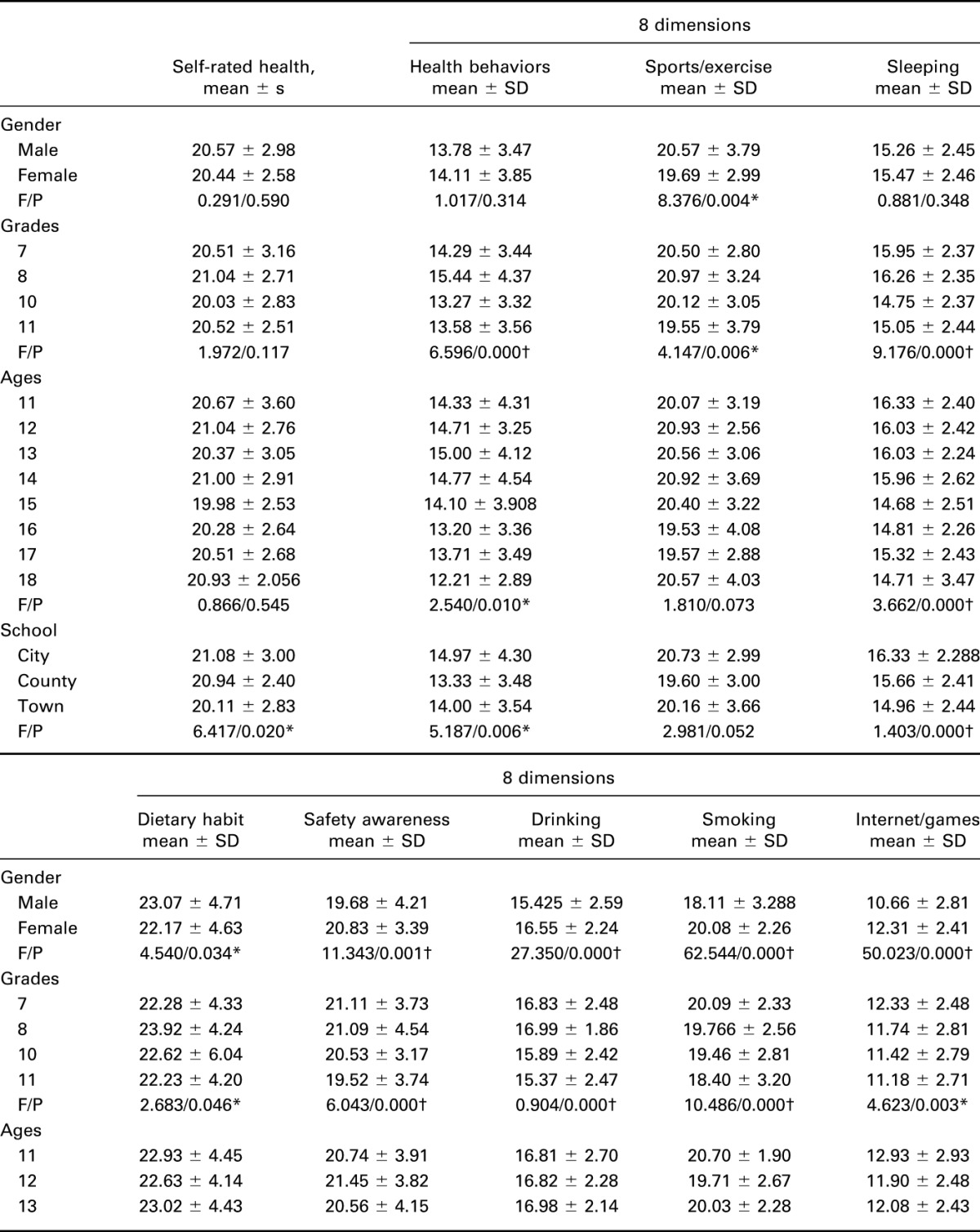

The students' self-rated health and the health conditions for 8 dimensions were compared between different genders, grades, ages, and levels of schools. The results showed that there were statistical significant differences between male and female students in terms of Sports/Exercise, Dietary habit, Safety Awareness, Drinking, Smoking, and Internet/Games, whereas there were statistical significant differences among grades and ages in terms of Health Behaviors, Sleeping, Safety Awareness, Drinking, and Smoking (Table 4).

Table 4.

Comparison on students' self-rated health with different genders, grades, ages, and schools.

In Table 4, significant main effects (P ≤ 0.05) were observed in terms of self-rated health for different schools, but not for gender, age, and grade. Using analysis of variance comparison of means test, self-rated health for town students was consistently lower than the county, county was lower than municipal students. Self-rated health declined significantly from municipal level to county level and to township level. The analysis indicates that the adolescence coming from different administrative levels of school show a significant difference in the 6 dimensions including Health Behaviors, Sleeping, Dietary habit, Safety Awareness, Drinking, and Smoking (P ≤ 0.05), but there is no significantly difference in the other 2 dimensions including Sports/Exercise and Internet/Games (P > 0.05). In term of Sports/Exercise and Dietary habit, the analysis show that female scores was lower than male scores (P ≤ 0.05), but in the dimension of Safety awareness, Drinking, Smoking, and Internet/Games, female student scores were higher than male student scores (P ≤ 0.05).

In addition, we included personal and proximal situation factors such as gender, age, and grade; school situation was an important predictor of perceived health in all adolescences. Students' health assessment was likely to be influenced by their overall awareness with their health, as indicated in Table 4, because school is regarded as an influencing factor of students' assessment for their health.

DISCUSSION

The concept of self-rated health implies a global assessment of one's own health, summarizing the way in which different aspects of health, physical as well as mental, are combined within one's perceptual framework.11 Adolescence is an important period for the people to form health awareness, which will help them to choose and improve their health behavior. Most health behaviors retained significant associations with attained educational level, even after controlling for school achievement and sociodemographic background.18

The status of sleeping

Sleeping is an important physiological need of adolescents and a basic, clinical criterion to evaluate their health condition. Primary and secondary school health education guidelines issued by the Ministry of Education in China indicated in 2008, that ample sleep is good for students' growth and health. Junior high school students should have 9 hours of sleep a day, whereas senior high school students should have 8 hours of sleep. This survey shows that only 40.3% of the students have sleep time more than 8 hours, and 4.4% students even have less than 6 hours. In the United States, only 20% of adolescents get their optimal 9 hours of sleep on school nights. Morrison reported that 10%–23% adolescents have sleep quality problems, like difficulty in falling asleep, and early wake-up problems at different degrees.19 Sun et al20 indicate that fifth-grade children in Shanghai have an excessive homework burden, which overwrites the benefit of sleep hygiene on sleep duration. Insufficient sleep in school-aged children is common in modern society, with homework burden being a potential risk factor.20–22 Better sleep hygiene was associated with earlier bedtimes and longer sleep duration. To analyze from the perspective of sleep and stress, all the 3 groups show differences. The municipal group result is better than the county group and county better than the town group. As for the 2 groups of the county and town, with accelerated urbanization and reform of industrial structure in China, some of the town adolescents students' parents are migrant workers, the result may be related to less family care. Establishing a regular, consistent sleep schedule early in adolescence may enhance healthier sleep schedule in the future. Both aspects from the family and school should pay enough attention to the quality of sleep of adolescent students by understanding the students' physical and psychological development and keeping the school homework in an appropriate manner to ensure students have enough time for sleep. It is the duty for both parents and educators to guarantee adolescents a fair schedule of work, enough rest time, and good sleep quality.

The dietary habit of adolescent students

Total nutrient and energy requirements are highest during adolescence to meet the needs for physical growth and development; however, adolescents often fail to meet these elevated dietary needs.23 The survey shows that adolescent students skip breakfast and have unreasonable nutrition composition. Approximately 1.0% of them never have breakfast and 14.7% occasionally have. The status sought by older adolescents consists of rites, which transition them toward adulthood.24 The various understandings of what healthy eating actually means are likely to have different implications for eating behavior.25 Respondents indicated that in early adolescence, they lacked interest or were unaware of the importance of diet.26 Diets abundant in fruits and vegetables are associated with reduced risk for chronic disease, but intakes by adolescents are often inadequate.27 In terms of dietary habit, county students' scores are lower than municipal group and town group; it may be related to the local dietary habit. School-based interventions that target health-related awareness, attitude, and behaviors among school teachers may help improve school-aged children's eating behaviors.28

The status of physical activity in adolescents

In adolescence, health-related behavioral patterns take shape, which form the core of the health-related lifestyle in adulthood and are associated with various dimensions of health.29 Such behaviors may be seen as inadequate or dysfunctional coping styles in the face of stress caused by educational demands.30 Physically active students reported better self-related health than less physically active students.9 The health benefits of leisure-time physical activity are widely recognized, as inactivity is associated with increased risk of coronary heart disease, various cancers, obesity, and other health problems.31 Investigation shows that students who never participate in appropriate sports or exercise accounted for 15.9% of the total and occasionally attending accounted for 25.2%. Those who participate at least 3 times a week, each time 20–30 minutes of exercise never insisted on joining accounted for 6.8% and occasionally attending accounted for 29.2%. Fortunately, adolescence is a critical time of great behavioral shaping and plasticity. Most adolescent health risks are the result of behavioral causes; much of this morbidity and mortality is preventable. Therefore, educators should encourage students to exercise more actively and make it easier for students to choose and take part in various kinds of sports, which will help their mental and physical development. And it is important to monitor trends in physical activity in young adults, and to understand factors such as attitudes and knowledge of health benefits that may be associated with activity levels.6 However, there are poor connections among data, research, programming, and policy.6 In China, everybody has to take a gratuitous compulsory education of 9 years and schools are supposed to organize students to have at least 1 hour of exercise, but most teachers and students cut the exercise time to study. Equality of educational opportunities among different levels of high school has been a central objective, and reforms of educational systems as well as increasing public investment to higher education are required to achieve this goal.

The differences among the different schools in self-related health

It indicates the differences in self-assessed health and health-related behaviors among the adolescent students from municipal, county, and township. Students from municipal have higher scores than students from county and town in self-related health. In terms of health promoting behaviors, students from municipal schools have higher scores than their counterparts from both county and town schools. The results can be explained by the health resources allocation and family investment in health differences between municipal, county, and town. Comparing the latter 2, municipal students have more information and resources related to health.

The study confirms that various person factors with different school are associated with self-rated health and related health behavior. However, the issue of determinants and variance in self-rated health among adolescents needs to be researched in greater depth including cross-sectional studies and longitudinal research design.

Footnotes

Supported by Science & Technology Department of Sichuan Province (Grant No.2012ZR0091).

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

REFERENCES

- 1.Niedhammer I, Tek ML, Starke D, et al. Effort-reward imbalance model and self-reported health: cross-sectional and prospective findings from the GAZEL cohort. Soc Sci Med. 2004;58:1531–1541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krause NM, Jay GM. What do global self-rated health items measure? Med Care. 1994;32:930–942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wade TJ, Vingilis E. The development of self-rated health during adolescence: an exploration of inter- and intra-cohort effects. Can J Public Health. 1999;90:90–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davies AR, Ware JE. Measuring health perceptions in the health insurance experiment[M]. Santa Monica, CA: Rand Corporation; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lancee B, Ter Hoeven CL. Self-rated health and sickness-related absence: the modifying role of civic participation. Soc Sci Med. 2010;70:570–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Irwin CE, Jr, Burg SJ, Uhler Cart C. America's adolescents: where have we been, where are we going? J Adolesc Health. 2002;31:91–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Koivusilta L, Rimpela A, Vikat A. Health behaviours and health in adolescence as predictors of educational level in adulthood: a follow-up study from Finland. Soc Sci Med. 2003;57:577–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Healy D, Mc Sharry P. Promoting self awareness in undergraduate nursing students in relation to their health status and personal behaviours. Nurse Educ Pract. 2011;11:228–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alricsson M, Landstad BJ, Romild U, et al. Self-related health, physical activity and complaints in Swedish high school students. ScientificWorldJournal. 2006;6:816–826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Taylor WC, Blair SN, Cummings SS, et al. Childhood and adolescent physical activity patterns and adult physical activity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1999;31:118–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang H, Fu J, Lu Q, Tao F, Hao J. Physical activity, Body Mass Index and mental health in Chinese adolescents: a population based study. J Sport Med Phys Fit. 2014;54:518–525. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen T, Wu Z, Shen Z, et al. Sleep duration in Chinese adolescents: biological, environmental, and behavioral predictors. Sleep Med. 2014;15:1345–1353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sun H, Ma Y, Han D, et al. Prevalence and trends in obesity among China's children and adolescents, 1985-2010. PLoS One. 2014;9:e105469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.United States. Department of Health, Human Services. Physical activity and health: a report of the Surgeon General[M]. Collingdale, PA: DIANE Publishing; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Anderson JJ. The important role of physical activity in skeletal development: how exercise may counter low calcium intake. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;71:1384–1386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hardman AE. Physical activity and health: current issues and research needs. Int J Epidemiol. 2001;30:1193–1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Paffenbarger RS, Jr, Blair SN, Lee IM. A history of physical activity, cardiovascular health and longevity: the scientific contributions of Jeremy N Morris, DSc, DPH, FRCP. Int J Epidemiol. 2001;30:1184–1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tilleczek KC, Hine DW. The meaning of smoking as health and social risk in adolescence. J Adolesc. 2006;29:273–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jenkins CD, Stanton BA, Niemcryk SJ, et al. A scale for the estimation of sleep problems in clinical research. J Clin Epidemiol. 1988;41:313–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sun WQ, Spruyt K, Chen WJ, et al. The relation among sleep duration, homework burden, and sleep hygiene in chinese school-aged children. Behav Sleep Med. 2014;12:398–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liang J. Self-reported physical health among aged adults. J Gerontol. 1986;41:248–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brook RH, Ware JE, Jr, Davies-Avery A, et al. Overview of adult health measures fielded in Rand's health insurance study. Med Care. 1979;17:iii–x. 1–131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Burgess-Champoux TL, Larson N, Neumark-Sztainer D, et al. Are family meal patterns associated with overall diet quality during the transition from early to middle adolescence? J Nutr Educ Behav. 2009;41:79–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haase A, Steptoe A, Sallis JF, et al. Leisure-time physical activity in university students from 23 countries: associations with health beliefs, risk awareness, and national economic development. Prev Med. 2004;39:182–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Darroch JE, Frost JJ, Singh S. Teenage sexual and reproductive behavior in developed countries. New York: Alan Guttmacher Institute; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brindis C. Advancing the adolescent reproductive health policy agenda: issues for the coming decade. J Adolesc Health. 2002;31:296–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Neumark-Sztainer D, Wall M, Eisenberg ME, et al. Overweight status and weight control behaviors in adolescents: longitudinal and secular trends from 1999 to 2004. Prev Med. 2006;43:52–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.He L, Zhai Y, Engelgau M, et al. Association of children's eating behaviors with parental education, and teachers' health awareness, attitudes and behaviors: a national school-based survey in China. Eur J Public Health. 2014;24:880–887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Feinstein JS. The relationship between socioeconomic status and health: a review of the literature. Milbank Q. 1993;71:279–322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rutter D, Quine L. Demographic Inputs and Health Outcomes: Psychological Processes as Mediators. Social Psychology and Health: European Perspectives. Aldershot, United Kingdom: Avebury; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kiess W, Blüher S, Kapellen T, et al. Physiology of obesity in childhood and adolescence. Curr Paediatrics. 2006;16:123–131. [Google Scholar]