Abstract

Firefly species (Lampyridae) vary in the color of their adult bioluminescence. It has been hypothesized that color is selected to enhance detection by conspecifics. One mechanism to improve visibility of the signal is to increase contrast against ambient light. High contrast implies that fireflies active early in the evening will emit yellower luminescence to contrast against ambient light reflected from green vegetation, especially in habitats with high vegetation cover. Another mechanism to improve visibility is to use reflection off the background to enhance the light signal. Reflectance predicts that sedentary females will produce greener light to maximize reflection off the green vegetation on which they signal. To test these predictions, we recorded over 7500 light emission spectra and determined peak emission wavelength for 675 males, representing 24 species, at 57 field sites across the Eastern United States. We found support for both hypotheses: males active early in more vegetated habitats produced yellower flashes in comparison to later-active males with greener flashes. Further, in 2 of the 8 species with female data, female light emissions were significantly greener as compared to males.

Keywords: contrast hypothesis, sensitivity hypothesis, reflectance hypothesis, emission spectrum, bioluminescence, Lampyridae

Introduction

Explaining the evolution of the diversity of visual signals in nature has been a long standing endeavor in evolutionary biology (Darwin 1872). In the early 1990s, Endler combined many previous hypotheses for signal system evolution under a single evolutionary framework termed “sensory drive” (Endler 1993). Sensory drive emphasizes that evolution favors signals that can be sent through the environment in a manner that minimizes signal degradation and maximizes the signal-to-noise ratio for the receiver. As a result, the biology of signal reception, and the characteristics of the environment will together drive the evolution of signals to improve detection by receivers in the context of their ecology. The sensory drive framework considers several factors acting on the evolution of signal characteristics including inherent signal conspicuousness in a given environment, effects of detection by non-target receivers such as predators, and properties of the targeted receivers’ sensors (Endler 1992, Boughman 2001). For visual signals, one hypothesized mechanism to enhance conspicuousness is to increase contrast with the background light environment. High signal contrast with the environment appears robustly supported in several groups. For example, in fish (poeciliids: Endler 1992, gasterosteids: Boughman 2001; and cichlids: Seehausen et al 2008) coloration in different environments is accurately predicted by the contrast hypothesis. Similarly, Anolis dewlap coloration in different habitats optimizes contrast and detection by conspecifics (Leal and Fleishman 2002, 2004).

Many species in the beetle family Lampyridae produce adult light signals to attract mates (Lloyd 1966, 1983, Lewis and Cratsley 2008, Stanger-Hall and Lloyd 2015). Light may be produced as a long glow or as a series of repeated flashes that vary in duration, repeat number, and/or repeat intervals (Barber 1951, Lloyd 1966, Stanger-Hall and Lloyd 2015). To the human observer they also clearly differ in the color of light that they produce (Lall et al. 1980). Interestingly, only the temporal pattern of light production, but not light color, has been demonstrated to have an effect on mate response (Lloyd 1966, Ohba 1981). This raises the question as to what explains the approximately 30 nm range, from green to orange/yellow, of peak wavelength in light emissions across North American firefly species (Biggley et al. 1967). Lall and coworkers (1980) suggested that this variation reflects adaptation to specific light environments to increase the likelihood of signal detection. This contrast hypothesis specifically states that light signal color (i.e. the light emission spectrum) in species active early in the evening is under selection to maximize contrast against ambient light reflected from green background foliage during twilight (Lall et al. 1980, Seliger et al. 1982a, b).

Lighted firefly species are active in low ambient light conditions, from one hour before until several hours after sunset. As the sun descends and sunset approaches, the ambient light spectrum becomes dominated by longer wavelengths (Endler 1993, Johnsen et al. 2006). Species with earlier activity times (while the sun is setting) experience ambient light that is a mix of long wavelength (orange-red) light from the sky and shorter wavelength (green) light reflected off the vegetation. After sunset, species experience reduced ambient light containing relatively more short (blue) wavelengths, but with increasing darkness the composition of the dim ambient light either goes to long-wave domination (without moon) or is spectrally neutral (full moon) (see Figure 1 of Johnsen et al. 2006). This whole process (sun moving from +10° to −10° relative to the horizon) lasts approximately 1.3–2 hours, depending on the distance from the equator (Johnsen et al. 2006). Thus, the light environment of early active species is dominated by short (<550nm: blue, green) and long (>600nm: orange-red) wavelengths, and a signal that is more yellow (550–600nm) is expected to increase the signal-to-noise ratio against the green vegetation background, improving signal detection and facilitating mating success (Seliger et al. 1982a, b, Endler 1992). For activity times later in the evening, ambient light wavelengths become longer and lower intensity, and so the contrast hypothesis predicts either greener or no optimal light emission color

Besides increasing contrast in certain ambient light environments, there are at least three other reasons why light emissions might be greener in some contexts. First, if the peak sensitivity of ancestral firefly eyes, and insect eyes in general, is in the green range (Lall et al. 1980, Eguchi et al. 1984), species with late activity may produce green light emissions to take advantage of this ancestral visual sensitivity in a dark environment, where contrast is no longer an issue. Second, greener light emissions are expected to increase signal conspicuousness when the signal can be reflected off a green background, resulting in an increased probability of signal detection in low-light environments (Endler, 1992). This reflectance hypothesis especially applies to firefly females, who typically produce their signal from the surface of vegetation. Third, larvae are thought to use their light signals to attract arthropod prey (Sivinski 1981), or to signal distastefulness to predators (Underwood et al. 1997, DeCock and Matthysen 2003). Both arthropod prey and arachnid predators are likely sensitive to green wavelengths (DeVoe et al. 1969, Briscoe and Chittka 2001), making green signals effective.

In their seminal paper on the ecology of colors of firefly bioluminescence, Lall and coworkers (1980) showed that 23 of 32 (71.9%) dark-active firefly species emitted green light (peak emission wavelength < 559nm), while 21 of 23 dusk-active species (91.3%) emitted yellow light (>560nm). While their evidence supports the role of increased contrast to enhance conspicuousness, this early analysis did not correct for shared evolutionary history of the species in the data set, which is one of the goals of the present study, nor did it consider within-species variation. Here, we expand the analysis to include the potential effect of open (field) versus closed (forested) habitats, with the closed habitat presenting an environment where the respective ambient light is filtered through green vegetation. We expect this to impact mostly early-active species with higher levels of ambient light (and visible vegetation), and predict the light spectra of the early species in the closed environment (more green-reflected ambient light) to be shifted more towards yellow than in the open environment (less green-reflected ambient light). Further, we investigate whether female and larval emissions are greener, as predicted by the reflectance hypothesis and the targeting of arthropod and arachnid receivers, respectively.

Methods

Field Measurements

For our large-scale testing of the predictions of the contrast and reflectance hypotheses, we undertook a survey of the light emission spectra of individual field-captured fireflies during three successive years across the Eastern United States. Most of our data are from adult males, because they are easier to find in large numbers than females, but we measured the light emissions of any females (and larvae) opportunistically when encountered. We analyzed male and female signals separately because signaling males tend to be airborne, searching for responding females, while signaling females are usually sedentary on vegetation, scanning the sky for signaling males. As a result, their signaling micro-environments are different, and, while the contrast hypothesis for signal evolution may be driven by both sexes, we expect the reflectance hypothesis to apply primarily to sedentary females.

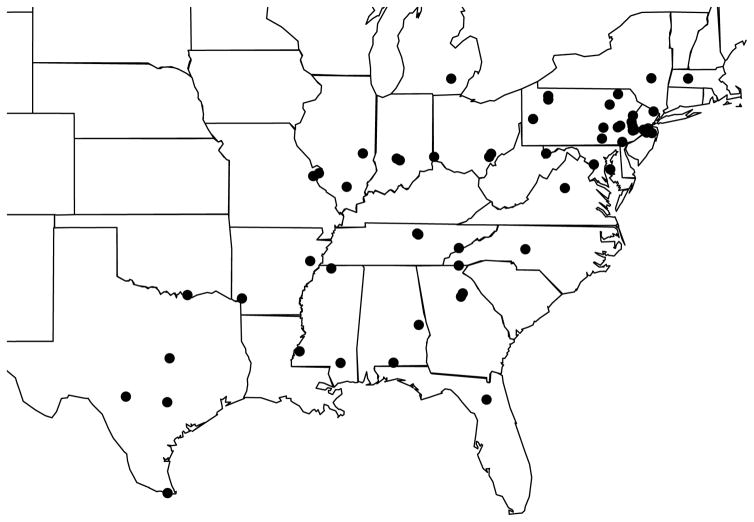

Specimens were collected at 57 field sites across the Eastern United States from April through August of 2012, 2013 and 2014 (Fig. 1). At each site, we attempted to collect emission spectra on a minimum of five male individuals of each species. Spectra were measured as soon after capture as possible, usually within an hour. In some cases, due to logistical challenges, spectra were measured on a different day, when fireflies were flashing voluntarily in their collection tubes. At time of capture, we also recorded temperature, elevation, longitude, latitude, time of initiation of flashing activity, and classified the habitat in which a species was active. In addition to the individuals collected by the authors, colleagues sent a few live specimens to us. We recorded emission spectra for these individuals but other variables, such as habitat and activity time were not recorded. Because females and larvae are difficult to find in large enough numbers the wild, only males for which we had spectra, activity time and habitat information, were used for testing the contrast hypothesis. The geographic locations and spectral data for all 786 measured individuals, including 675 males (666 with habitat and activity time data) have been deposited to Dryad Digital Repository (“Spectra data”, dx.doi.org/10.5061/dryad.pj51q). For collection permissions and permits, please see Table S1.

Figure 1.

Location in Eastern US of the 57 field sites at which individuals were collected and their emission spectra measured.

Activity time

At every field site, each collected species was assigned to an activity time category based on the start of its activity (i.e. when the first individuals of a species were caught) relative to sunset. The precise time of sunset was determined from the latitude, longitude, and date of collection using the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Solar Calculator (www.esrl.noaa.gov). Species were divided ordinally into early (score = 0) or late (score = 1) categories, following Lall and coworkers (Lall et al. 1980). Early species were defined as those that became active before and up to thirty minutes after sunset (civil twilight into early nautical twilight), while late species commenced activity more than thirty minutes after sunset (nautical and astronomical twilight and darkness). Each population of each species was assigned to an activity category based on local observations; the overall activity score for a species was calculated as the average of the ordinal scores across all of its populations. We utilized the onset of activity rather than peak activity for two reasons. First, activity tends to peak soon after onset (personal observations), and then declines over time, especially for females (presumably as they mate), implying that ambient light levels at or near the beginning of the activity period are the most appropriate. Second, the onset of activity has traditionally been used by other studies (e.g. Lall et al. 1980).

Habitat type

At each site, habitat classifications were performed independently by the same two observers (JCP and SES). Habitat was classified based on the density of vegetation in the area: fields and areas with minimal undergrowth were classified as open (score = 0), wooded areas or areas with thick vegetation were classified as closed (score = 2), and areas where activity occurred in both open and closed habitats, or on the edge between these two regions, were classified as mixed (score = 1). Each population was assigned to a habitat category based on the location where most flashing individuals were active. The overall habitat category for a species was the average across all populations. Regardless of species, usually all members of a population were active in the same habitat during the same activity time.

Emission spectra

Spectra for each individual were recorded in the field using an Ocean Optics Jaz EL-200 spectrometer, and processed with SpectraSuite software (v 12.2.0, Ocean Optics). Individual fireflies were held so that the unobstructed light organ was in line with the end of the fiber optic cable. During measurements, each flash was transmitted to the spectrometer, which recorded the emission spectrum to a laptop (Dell Inspiron Mini10v) as the intensity of the signal, measured in counts, which are proportional to the number of detected photons, versus the wavelength. The duration of signal integration was determined empirically by visual inspection of the first few recorded emission spectra for a species. Settings were chosen to capture sufficient signal to produce a detectable emission spectrum while not saturating the sensor (i.e. bright flashing species required shorter integration times). The SpectraSuite software trigger function was used to capture single flashes in real time. The trigger was set so that luminescence from a specimen would result in the automatic recording of a spectrum. For each individual, we attempted to record the emission spectra of at least five flashes (e.g. Fig. 2) and were able to do so for over 85% of individuals. Across all males, we recorded 1 – 52 flashes per individual (median = 10), and across females we recorded 1 – 34 flashes per individual (median = 8.5).

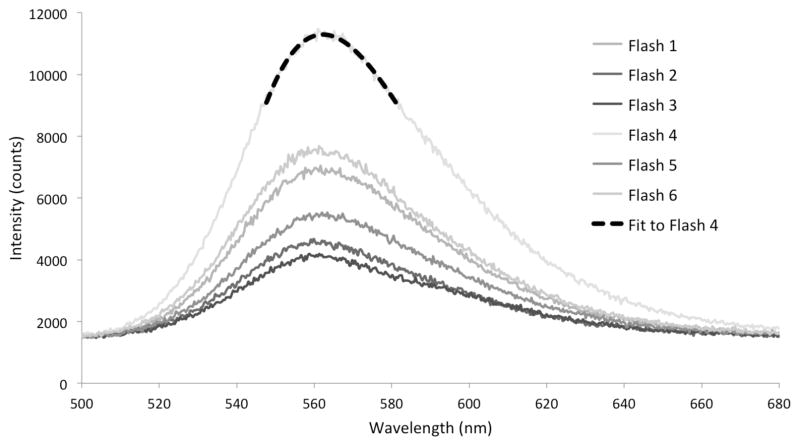

Figure 2.

Six spectra measured from a single Photinus pyralis individual (specimen KSH9314). Intensity in counts over a 100 ms integration time versus wavelength in nanometers. A count is proportional to the number of photons detected by the instrument at a particular wavelength during the integration period. Spectral intensity (counts) varies across emission spectra because of variation in the distance between the light organ and the detector. However, there is no affect of spectral intensity on peak emission wavelength. Also shown (black dotted line) is the fitted cubic for one flash (Flash 4) used to determine peak emission wavelength for that flash, as detailed in Methods.

Experimental Controls

To assess the reliability of the field spectrometer measurements, we routinely checked its precision using a 545nm LED at the beginning and end of each night. In the lab, we also examined the effect of running time (i.e. since being turned on) and optic cable aperture size. In no case did we find that readings were affected by the tested variables. Since we were planning to hold some of the smaller specimens cupped in our hand to record light emissions, we tested the effect of various holding methods on the emission spectrum. Reflections from the skin sometimes caused a small red shift (up to a few nm) in the readings. As a result, we took great care that all measurements were taken with an unobstructed light organ by holding the head and thorax of specimens, or by measuring them through a clear, conical collection tube, which we confirmed did not shift the wavelength, using a 545nm LED.

Spectra Analysis

Due to the measurement noise across individual spectra (the wiggle visible in the curves in Fig. 2), we could not simply use the highest value of the emission spectrum as the peak emission. Instead, a cubic polynomial was fit to the spectrum in the region of maximum intensity to estimate the peak emission wavelength, using a custom program in Mathematica (Wolfram Research, 2010). When the program was written, several different polynomials were evaluated, and the cubic fit was found to perform the best. We manually double-checked the maximum emission wavelength obtained by the program for over 100 spectra from several different species, and found that the estimated peak and the peak obtained by visual inspection were essentially indistinguishable (see Fig. 2 for an example fit). In some populations a few individuals, or a few spectra within individuals, appeared to be outliers. These were each manually checked. In no case did we find a peak wavelength that was incorrectly determined by the program, and so all spectra were included in the analyses. For several individuals we also verified that the peak wavelength was unaffected by the intensity of the spectrum. Variation in flash intensities within an individual (e.g. Fig. 2) primarily resulted from the distance between the light organ and the detector.

Specimen collection

Fireflies were collected opportunistically, resulting in 25 different species in our final dataset. Each species was collected at between 1 and 42 field sites. A particular species found at a particular field site was designated as a population; across all species we collected 139 populations. For three species, Photinus pyralis, P. scintillans and P. marginellus, we collected adult male spectra for ten or more populations, allowing us to test the contrast hypothesis within these species (Fig. S1–S3). P. pyralis and P. marginellus are widespread and commonly found in a variety of habitats across their ranges. Both males and females of these species are able flyers. In contrast, P. scintillans has a fairly narrow geographic range with less habitat variation, and only males of this species are able to fly. The peak wavelengths for P. pyralis, P. marginellus and P. scintillans have been previously reported as 562, 565 and 574 nm respectively (Biggley et al., 1967).

We collected and measured females of eight species, and in two species we captured sufficient numbers of females (n ≥ 10) to test the prediction of the reflectance hypothesis (i.e. females should be green-shifted relative to their males).

Species Identification

After spectra were measured, specimens were preserved in 95% ethanol and stored at −80°C. Species identity for males was initially established in the field using flash pattern and morphology and verified with genitalia extraction (Fender 1966, Green 1956, 1957, Lloyd 1966, 1969a, 1969b, Luk et al. 2011). In addition, one male per species from each population and any ambiguous females were confirmed molecularly. DNA was extracted from 1–3 legs using a DNeasy kit (QIAGEN Company) and ~647 bp of cytochrome c oxidase I (COI) was amplified and sequenced using primers designed for fireflies (HCO/LCO: Stanger-Hall et al. 2007). This mitochondrial gene is appropriate for species identification at this taxonomic level (Kim et al. 2001, Simon et al. 1994) and has been utilized previously (Stanger-Hall et al. 2007, Stanger-Hall and Lloyd 2015). Amplicons were sequenced at the Georgia Genomics Facility on an Applied Biosystems 3730xl 96-capillary DNA Analyzer.

Sequences were assembled in Sequencher (v. 5.0.1, Gene Codes Corporation) using default parameters and manually checked for ambiguities. Assembled contigs were then aligned to COI sequences from voucher specimens using MUSCLE (Edgar 2004) in Geneious (v. 7.0.6, Biomatters Limited) with default parameters. The resulting alignment was manually reviewed and used to build a neighbor-joining phylogeny with Tamura-Nei distance correction. Specimens that grouped with known vouchers were considered verified as that species. Due to the difficulties in defining species in Photuris (Lloyd 1969a, 1990), we did not classify individuals from this genus into species, except for individuals of Photuris frontalis, which is a definitive species based on the COI locus (unpublished data). We utilize “Unknown Photuris” in the remainder of the manuscript to indicate uncertainty regarding the actual number of species present. For our statistical analyses, we treat Unknown Photuris at a particular field site as a single species, and thus a single population. If this assumption is incorrect, and more than a single species is present within this group at a field site, the effect will be to lower our power for hypothesis testing. Morphology and COI data also identified an undescribed species of Phausis, which we refer to as “Phausis sp.”. In addition, we treat “P. macdermotti single flash” as a separate species from P. macdermotti, which typically has a 2-flash pattern (Lloyd 1984). All individuals of P. macdermotti single-flash were collected at a single field site (East Brunswick, NJ), and thus represent a single population. These individuals had a single, as opposed to the species-characteristic double-flash (see also Lloyd 1969b, Carlson et al. 1976), they differed in peak wavelength, and their divergence at the COI locus was comparable to other species.

Larval measurements

We obtained light measurements for four P. pyralis larvae that were offspring of two field-collected females, one from the Doylestown, PA field site and one from the Athens, GA site. We also obtained light measurements from nine Unknown Photuris larvae that were offspring of two field-collected females, one from Tate City, GA and one from Catskill, NY, a field site where no adult spectra were recorded. All four of the females were placed in separate containers with a male from the same population to guarantee mating. After egg hatching, the larvae were reared in the lab for 11 months to the fifth instar before spectral measurements were taken. In addition, larval light organ spectra were recorded from three adult individuals of two different species (P. pyralis and Lucidota atra), which had retained their larval light organs after eclosion (Fig. S4). This coexistence of both light organs is possible because the adult light organ develops on different abdominal segments (Branham and Wenzel 2003).

Data analysis and hypothesis testing

We used analysis of variance (ANOVA) in JMP (v. 11.0.0, SAS Institute Incorporated) of male data to investigate the relationships between spectra and activity or habitat, both across all species and within P. pyralis, P. marginellus, and P. scintillans. We specifically tested whether firefly populations that vary in activity time and habitat type exhibit differences in emission spectra in the direction predicted by the contrast hypothesis. In our ANOVA models, spectra was the dependent variable, activity time, habitat type and their interaction were independent variables, and population was included as a random effect. Within species, activity time was not included in the model because it did not vary across P. pyralis, P. marginellus, or P. scintillans populations. The across-population variance in peak wavelength was not significantly different across species, but the within-population residuals were not normally distributed, even after various transformations, violating an assumption of ANOVA (Sokal and Rolf 1995). We thus performed the ANOVAs with rank order data, in which all male individuals of all species were ranked by their peak wavelengths, and then ranks rather than wavelengths used in the analyses. Significance of results using raw data and ranked data were qualitatively identical except for one analysis (within-species analysis of P. marginellus populations). We present results for statistical significance using rank data but use raw data in figures for ease of interpretation. ANOVA results for both raw and rank data are given in Supplementary Information.

Phylogenetic corrections

When analyzing trait evolution across species, there is the potential problem of phylogenetic dependence and replicate (non-independent) sampling (Garland et al. 1999), which can bias results. Therefore we conducted a phylogenetically-independent contrast analysis. First, we expanded the most recent North American firefly phylogenies (Stanger-Hall and Lloyd 2015, Sander and Hall 2015), to include the additional species measured in our study. We sequenced one mitochondrial (COI: 1272 bp) and two nuclear (CAD: 594 bp, WG: 420 bp) gene fragments from 32 additional taxa (including P. macdermotti single-flash and 31 taxa outside of Photinus). The sequences were assembled using default parameters and manually aligned in Geneious (v. 7.0.6, Biomatters Limited). Subsequently the best substitution model for each gene was determined using jModeltest v. 2.1 (COI: GTR+I+G, CAD: TIM3+I+G, WG: K80+I+G; Dariba et al. 2012, Guindon and Gascuel 2003, Guindon et al. 2010). To account for rate variation among lineages, ultrametric phylogenies were constructed in BEAST v.1.8 (Drummond et al. 2012) using an uncorrelated lognormal clock model. BEAST was run twice for 30 million generations each with 25% burn-in, until the estimated sample size for all parameters was over 200. Independent runs were assessed for convergence using Tracer and the majority-rule consensus tree produced in TreeAnnotater. The final tree was trimmed to include only those taxa used in the present study. The Asian species Luciola cruciata (sister taxon to the North American taxa: Stanger-Hall et al. 2007) was used as the outgroup for all analyses. The topology of the resulting phylogeny (Fig. 3) was consistent with previously published molecular phylogenies (Stanger-Hall and Lloyd 2015; Stanger-Hall et al. 2007). The branch lengths for the trimmed phylogeny and the Genbank accession numbers for the DNA sequences of included, newly-sequenced taxa are reported in Table S2.

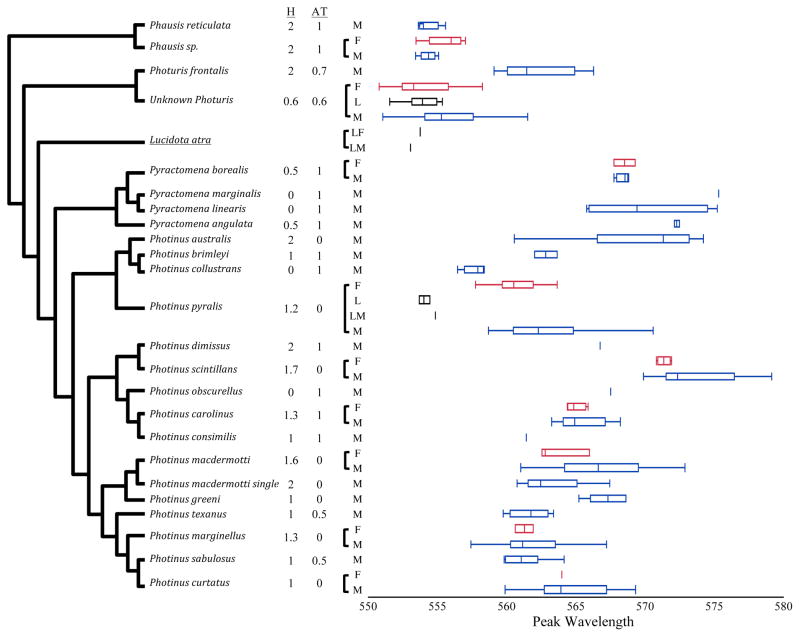

Figure 3.

Peak wavelengths of the emission spectra of North American firefly species. Whisker plots give mean, upper and lower quartiles and range of emission peaks for all individuals collected within a species. Male (M, blue boxes), female (F, red boxes) and larval (L, black boxes) data are shown when available. For three individuals, representing two species, larval light organs were present and measured in adult males (LM) or adult females (LF). Habitat (H) and activity time (AT) species averages are from the average of population ordinal assignments. Habitat was assigned as open (0), mixed (1) or closed (2). Activity was assigned as early (0) or late (1). The underlined species, Lucidota atra, is diurnal. Sample sizes for each species are in Dryad Digital Repository (“Individuals per Species”, dx.doi.org/10.5061/dryad.pj51q). “Unknown Photuris” represents the data from all individuals in the genus Photuris that were not Photuris frontalis. Phausis sp. represents a new species of Phausis based on COI sequences. Photinus macdermotti single is a group of individuals from East Bruswick, NJ (EBNJ) that is genetically close to Photinus macdermotti but has a single instead of a double male flash and may thus represent a cryptic species.

For the phylogenetically-corrected analysis with independent contrasts (PIC, Garland et al. 1999) we used activity time and habitat category for each species (averaged across populations) in the PDAP module of Mesquite v2.75 (Garland et al. 1999, Garland and Ives 2000, Garland et al. 1993, Maddison and Maddison 2011). We tested for statistical adequacy of branch lengths and found it was necessary to transform branch lengths (Garland et al. 1992, Garland et al. 2005), which we did using both Grafen’s (Grafen 1989) and Nee’s method (cited in Purvis 1995). Phylogenetically-independent contrasts were then performed to test whether changes in either habitat or activity were correlated with peak wavelength changes across the phylogeny.

Results

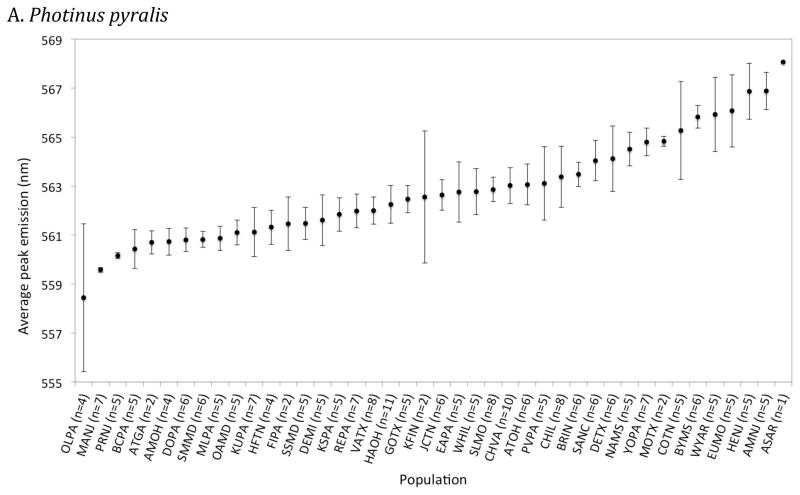

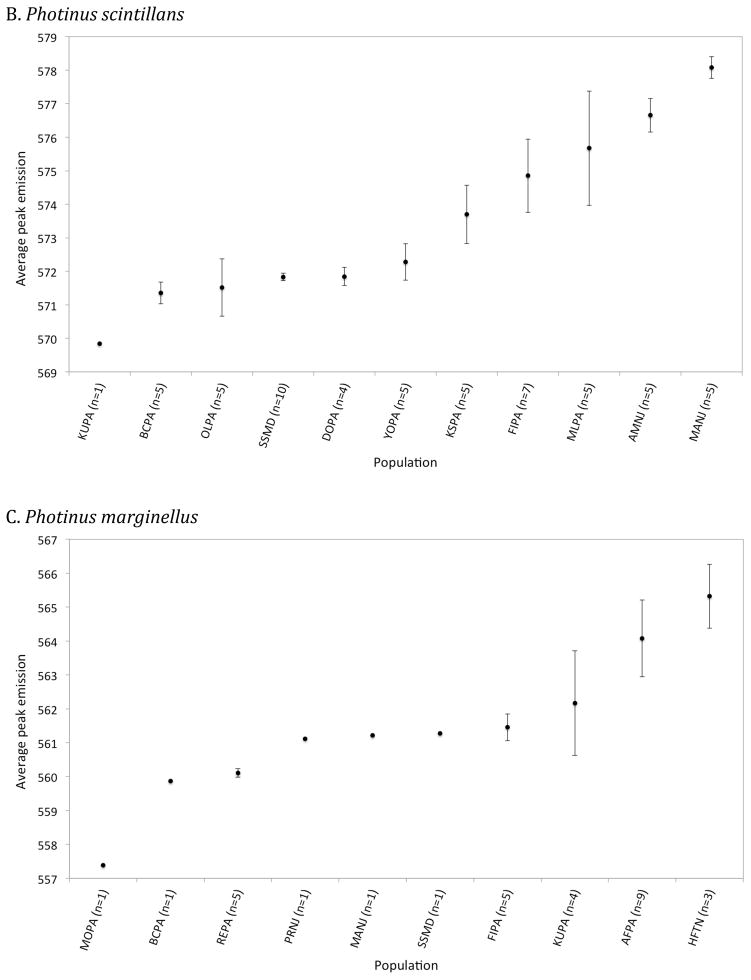

Across all species, within-male variation was generally low, usually less than 1 – 2nm (e.g. Fig. 2), but was higher in about one quarter of the individuals measured, and in one case an individual Photuris sp. (KSH_10821) produced subsequent emission spectra that varied by 10nm (Dryad Digital Repository: “Spectra data” dx.doi.org/10.5061/dryad.pj51q). Across species, there was substantial variation among males in peak wavelength (Fig. 3). In the three Photinus species with ten or more populations measured, there was also considerable variation within and across populations, with the average peak wavelength differing 8 – 10nm among populations (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Mean male peak emission wavelength (± standard error) across 42 Photinus pyralis (A), 11 Photinus scintillans (B) and 10 Photinus marginellus (C) populations arranged in order of increasing mean peak wavelengths. The population code and number of individual males (in parentheses) measured in each population is indicated along the x-axis. The population code and GPS coordinates are in Dryad Digital Repository (“Field site locations”, dx.doi.org/10.5061/dryad.pj51q).

Within species analysis: Testing the contrast hypothesis for firefly males

All three of the Photinus species with at least 10 populations showed early activity in all populations, precluding a test of the predictions of the contrast hypothesis for early versus late activity. However, populations varied in habitat usage, which allowed testing of the predictions of the contrast hypothesis for open versus closed habitats, which predicts yellower emissions in more closed habitats.

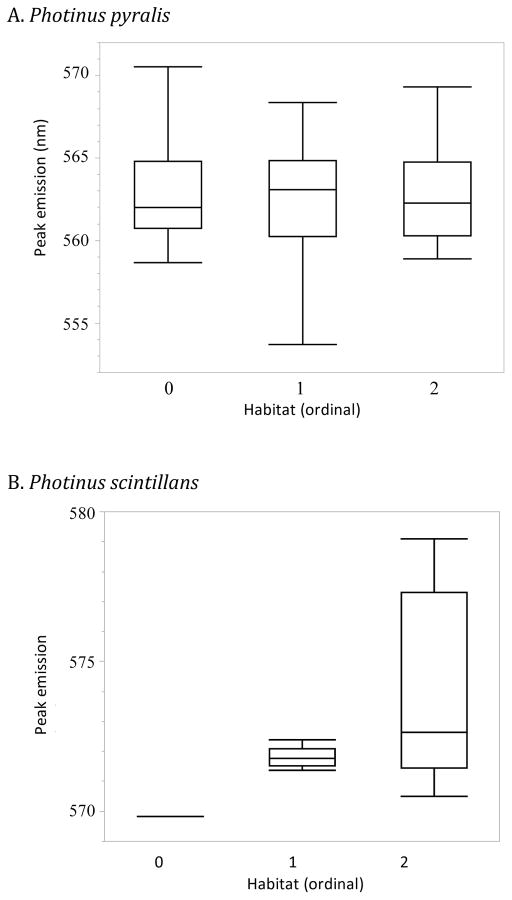

P. pyralis: 221 males were recorded at 42 sites (Fig. S1), with habitat categorized at 41 of them. The population-average ranged from 558.4 – 568.1nm, with a species average (± 1 standard error) of 562.80 ±0.33nm (Fig. 3 and 4A). There was no evidence for an effect of habitat type on male peak wavelength (Fig. 5A), using data for all individuals (ANOVA, p = 0.92) or only population averages (ANOVA, p = 0.98).

P. scintillans: 57 males were recorded at 11 sites (Fig. S2). The population average ranged from 569.8 – 578.1nm, with a species average of 573.42 ±0.78nm (Fig. 3 and 4B). For the data set including all individuals, there was a significant effect of habitat type (ANOVA, p = 0.0059) on male peak wavelengths, despite there being only a single population in each of the open and mixed habitat categories. This effect was not significant when only population averages were examined (ANOVA, p = 0.18). Populations in closed habitats were more yellow-shifted, i.e. had longer peak wavelengths, than populations in open or mixed habitats (Fig. 5B), while peak wavelengths of populations in open and mixed habitats did not differ significantly from each other.

P. marginellus: 31 males were recorded at 10 field sites (Fig. S3). The population average ranged from 557.4 – 565.3nm, with a species average of 561.40 ±0.69nm (Fig. 3 and 4C). Closed habitats were associated with more yellow spectral emissions (Fig. 5C), similar to P. scintillans, and this trend was significant for the full data set (ANOVA, p = 0.048), but not for the data set using only population averages (ANOVA, p = 0.27).

Figure 5.

Distribution of male peak emission wavelength versus habitat category in Photinus pyralis (panel A, 221 males in 41 populations), Photinus scintillans (panel B, 57 males in 11 populations) and Photinus marginellus (panel C, 31 males in 10 populations). There is no significant relationship between light emission spectra and habitat in P. pyralis (ANOVA, p = 0.92), but there is in both P. scintillans (ANOVA, p = 0.0059) and P. marginellus (p = 0.048). An outlier box plot is shown for all individuals in each habitat. Box lines correspond to 1st, 2nd and 3rd quartiles; whiskers correspond to furthest point within 1.5 times the inter-quartile range, and remaining points are outliers. Habitat was assigned as open (0), mixed (1) or closed (2).

Across species analysis: Testing the contrast hypothesis for firefly males

All 666 males with measurements for activity time and habitat category across the 57 different field sites were included in the across-species analyses. These 666 individuals represented 127 populations (defined as different species and field site combinations) and, assuming that P. macdermotti single flash is a bona fide species, at least 24 species (likely more, depending on the number of species in the Unknown Photuris group). The observed range in peak wavelengths across all these males was 551.4 – 579.1nm (ranging from green to yellow/orange to the human eye; Fig. 3).

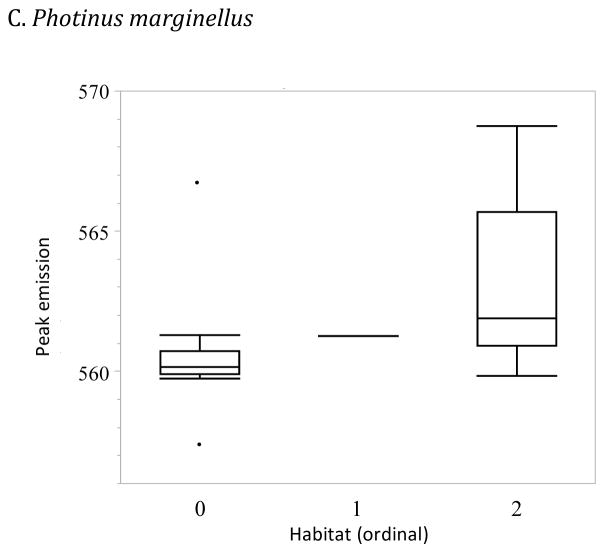

For a direct comparison with the findings of Lall and coworkers (1980) who documented a significant difference in emission spectra between early and late active species, we first tested the contrast hypothesis using a non-phylogenetic approach. In a model that included activity time and habitat as fixed effects and population as a random effect, there was a significant relationship between peak emission wavelength and both activity time (ANOVA: all data, p = 0.0075; population average data, p = 0.016) and habitat (ANOVA, all data: p = 0.036; population average data, p = 0.052; Fig. 6A and 6B). The interaction term between activity time and habitat was non-significant (p = 0.11) and was thus dropped from the model. The relationship between spectra and activity time was in the predicted direction: later active populations (darker environment with long-wavelength dominance) had greener light emissions. Similarly, the relationship between spectra and habitat category was in the predicted direction: populations in more closed habitats (ambient light filtered through green vegetation) had yellower light emissions. This finding is in agreement with the within-species analyses for P. scintillans and P. marginellus.

Figure 6.

The effect of habitat (A and C) and activity (B and D) on peak male emission wavelength in North American fireflies. In A and B each of the 127 populations are treated as independent data points. There is a significant positive relationship between spectra and habitat score (ANOVA, p = 0.048) and a significant negative relationship between spectra and activity time (ANOVA, p = 0.016) across populations. Habitat was assigned as open (0), mixed (1) or closed (2). Activity was assigned as early (0) or late (1). In C and D, populations of each of the 24 species are averaged to give species values for activity, habitat and emission color. There is no relationship between peak emission color and habitat or between peak emission color and activity time across the 24 species. Note that Phausis reticulata and Phausis sp. have the same activity and habitat values and are almost identical in emitted spectra, so they appear as a single point.

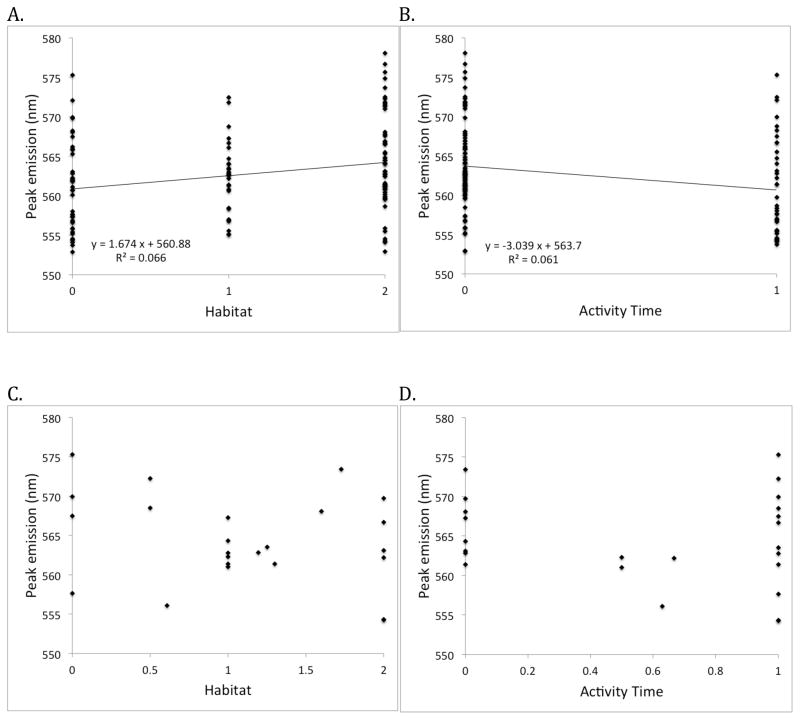

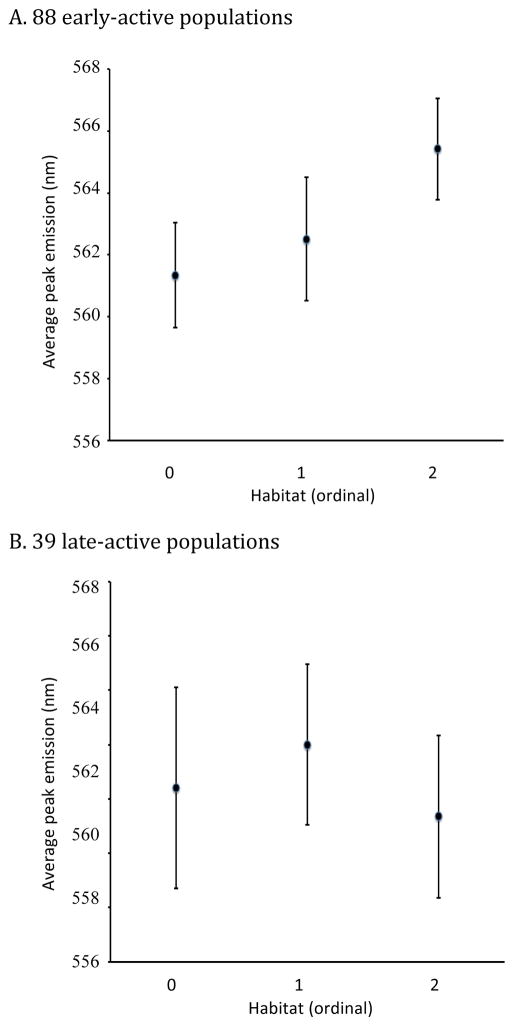

The prediction of the contrast hypothesis is that habitat is most likely to play a role in the evolution of peak spectral emittance when ambient light is not too low. We thus partitioned the data into early and late active populations and examined the relationship between spectral emission and habitat category for each activity period separately. Among the 39 late-active populations (16 in open, 13 in mixed and 10 in closed habitats), there was no relationship between emission spectra and habitat type (Fig. 7A; ANOVA: all data p = 0.51; population average data, p = 0.53). In contrast, among the 88 early-active populations (25 in open, 16 in mixed and 47 in closed habitats), there was a significant relationship between emission spectra and habitat type (Fig. 7B; ANOVA: all data, p = 0.0046; population average data, p = 0.0068), with populations in more closed habitats significantly yellow-shifted compared to those in more open habitats.

Figure 7.

Average peak male emission wavelength in each habitat category for early-active (A) and late-active (B) populations. Confidence intervals, calculated as the mean ± 2 standard errors, are also indicated. Habitat was assigned as open (0), mixed (1) or closed (2). There is a significant relationship between spectra and habitat in early-active (ANOVA, p = 0.0046) but not late-active (ANOVA, p = 0.51) populations.

For a species-level rather than population-level comparison, we then obtained 24 species-specific estimates of each variable by averaging across populations to test the contrast analysis at the species level. This required that we treat activity time and habitat as continuous variables. We found no significant (species-driven) association between spectra and activity time (ANOVA, p = 0.20), or habitat category (ANOVA, p = 0.13) (Fig. 6C and 6D). Inclusion of the Unknown Photuris populations (for a total of 25 species) did not qualitatively alter the results of this analysis.

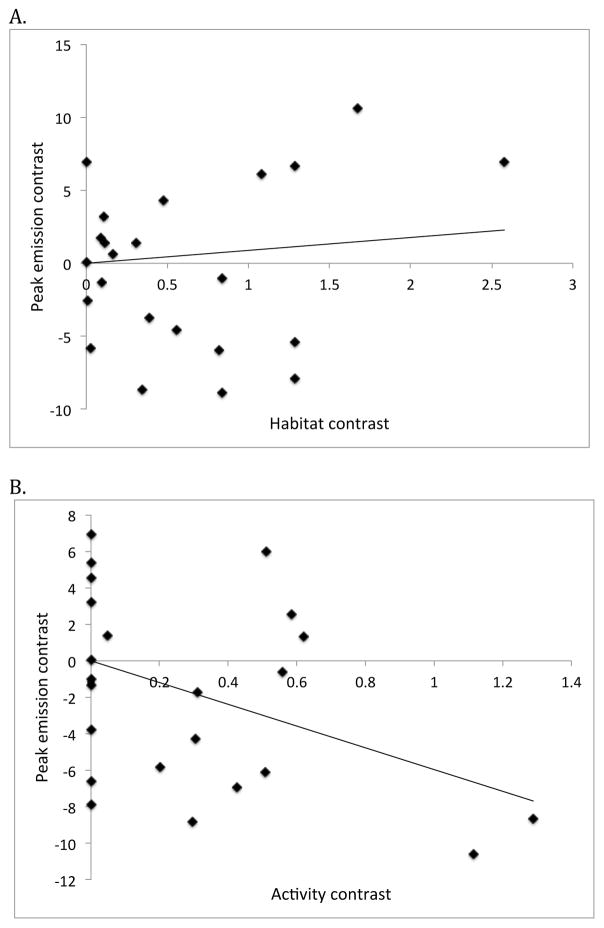

The population-averaged data from 23 species (omitting the Unknown Photuris category) were then used in a phylogenetically-corrected (independent contrast) analysis. There was a significant negative correlation (p = 0.01 for Nee transformation; p = 0.002 for Grafen transformation) between spectra and activity contrasts (Fig. 8B). This indicates that earlier activity is associated with yellow-shifted light emissions across the 23 firefly species, as predicted by the contrast hypothesis. There was no statistically significant correlation between peak wavelength and habitat type (p > 0.3 for both transformations), though the trend was in the same direction as observed in our other analyses (Fig. 8A). The correlation between peak wavelength and habitat type was also non-significant when only those species with early active populations (n = 11) were analyzed (data not shown).

Figure 8.

Phylogenetically independent contrast analysis: Peak emission contrast versus (A) habitat contrast and (B) activity contrast across 23 species of fireflies. Branch lengths of the original phylogeny were transformed using Nee transformation. The relationship between peak emission and habitat (A) is not significant (p = 0.5), but there is a significant negative relationship (p = 0.01) between peak emission and activity (B).

Variation in female and male light measurements: Testing the reflectance hypothesis

Most spectra were recorded in males, which are much easier to find in large numbers in the field. For those species where females were collected, we often observed differences in peak wavelengths between sexes (Fig. 3). In two of the eight species with both female and male data, wavelengths were significantly different between the sexes (P. scintillans: 54 males, 10 females, t-test, p = 0.0125; P. pyralis: 206 males, 28 females, t-test, p < 0.0001). Females and males were also significantly different in the collective Unknown Photuris sample (166 males, 37 females, t-test, p=0.0442), however it is very likely that this taxon includes more than one species. In all three instances of significant sex differences, the females were green-shifted (or less yellow-shifted: shorter peak wavelengths) compared to the males. Failure to detect significant differences in the other six species may be due to either to no difference between the sexes, or to insufficient statistical power given the lower number of females measured (n = 1 – 5).

Larval light measurements

The average peak wavelength of larval light emissions was 554.03 ±0.22nm (mean ± 1 standard deviation) for P. pyralis, and 553.86 ±0.39nm for Unknown Photuris larvae (Fig. 3). The peak wavelength of larval P. pyralis was significantly shorter than in adult P. pyralis (t-test, p < 0.0001; Fig. 3), but larval Unknown Photuris were within the adult range of Unknown Photuris. The single adult male P. pyralis that had retained a functional larval light organ gave us the unprecedented opportunity to compare the light emissions from retained larval and adult light organs in the same individual at the same time: there was an ~5nm difference (peak wavelength) between the light emissions from his retained larval (554.84 ±0.33nm) and adult (560.13 ±0.37nm) light organ. Two other adult individuals of Lucidota atra, a diurnal species, which lacks an adult light organ, retained paired larval light organs (photograph in Fig. S4). One of these individuals (specimen KSH_9216) was a male with a peak wavelength of 553.04 ± 0.13nm. The other (KSH_10086) was a female with peak wavelength of 553.71 ±0.36nm. For the female, we were also able to measure the peak wavelengths of her larval light organ during pupation (551.66 ±0.16nm).

Discussion

Fireflies produce a range of light color, and the present analysis documents variation in male light emissions at the individual, population, and species level, as well as variation between the sexes and between developmental stages.

Within species variation in adult light

Male peak wavelength showed extensive variation within species, which was surprising given that the literature often reports single values for a given species. Lall and colleagues (Lall et al. 1980) present data collected over 17 years that show essentially the same peak wavelengths within a species (but see Biggley et al. 1967). Our data clearly indicate that species vary across populations, across individuals within the same population, and sometimes even within individuals. These differences cannot be attributed to measurement error of the spectrometer, as we tested this exhaustively in the field and lab. In addition, we found no evidence that emission spectra are affected by the age of individuals in a population; daily spectral recordings on 9 P. australis and 4 P. pyralis males for 1 week (> 50% of adult life span) showed no shifts in peak wavelength for any individual (ANOVA, p = 0.26).

Male light color variation: the contrast hypothesis

We used peak wavelength data from 666 males representing 127 populations to test the contrast hypothesis, employing analyses that either ignored or phylogenetically-corrected for evolutionary relationships among species. The contrast hypothesis predicted that populations/species with early activity times should be yellow-shifted compared to populations/species with late activity times. Our data support this relationship both across populations of all species (Fig. 6B), and across species in the phylogenetically-corrected, independent contrast analysis (Fig. 8B). Thus, our results suggest that the predominantly yellow light signals of fireflies that are signaling during early twilight, while short wavelengths dominate the ambient light, are indeed the result of selection for increased contrast of their light signals against the blue-shifted ambient light from the sky and from ambient light reflected off the visible green vegetation. In closed habitats with an increased filtering of ambient light through green vegetation compared to open habitats at the same time, the contrast hypothesis predicts that selection should result in more yellow signals (away from the blue-green light filtered through the vegetation). This was supported by our population data within P. scintillans and P. marginellus (Fig. 5B. 5C), and the data across populations of all species (Fig. 6A) that showed that populations from more closed habitats indeed emit significantly yellower light than populations from open habitats. This trend is also apparent, but not significant, in our phylogenetically-corrected, contrast analysis based on the data for 23 species (Fig. 8A): species from more closed habitats tended to emit yellower light. The lack of significance in the phylogenetically corrected analysis was perhaps due to a combination of low sample size and the fact that some species have populations that are found in two or three habitat types.

The contrast hypothesis predicts yellower light for early active fireflies, but does not make a strong color prediction for late-active fireflies. As night sets in, the remaining ambient light is increasingly dominated by longer wavelengths, especially on moonless nights, which removes an advantage of yellow over green light emissions. On moonlit nights the ambient light spectrum resembles the neutral spectrum during daylight (at much lower light levels) and there is thus no selective advantage for yellow versus green light emission color (Johnsen et al. 2006) for late-active fireflies. So why do late-active male fireflies tend to produce greener light? There are at least three possible explanations. First, greener light may be the ancestral state for fireflies, which has not changed in late-active fireflies due to lack of selection for an alternate peak wavelength (e,g, Eguchi et al. 1984). Second, greener light may be most easily detected by conspecifics and is thus a result of sensory exploitation of potential mates. UV, blue and green photoreceptors evolved early in insect evolution, and most insects studied to date have green receptors maximally sensitive at ~530nm (Briscoe and Chittka 2001), suggesting sensitivity to this wavelength is an ancestral trait in insects. Third, greener light may be due to selection in females to maximize reflectance off the vegetation (see below) that causes a correlated response in males that is unopposed by selection.

Male versus female light spectra: the reflectance hypothesis

We found significant sex differences in the two species, P. pyralis, and P. scintillans, with sufficient data from both males and females. As predicted by the reflectance hypothesis for female signal evolution in fireflies, females of both species had greener (shorter peak wavelengths) light emissions compared to their males. In contrast to our findings, Biggley et al. (1967) reported no sex differences for these species, but Seliger and McElroy (1964) reported a small difference between males (575.1nm) and females (574.8nm) in P. scintillans. Two earlier studies reported a difference between male and female emission spectra for a species from Jamaica, Photinus xanthophotis, but their results are inconsistent. For example Buck (1941: cited in Seliger et al. 1964) reported a male peak wavelength at 585nm and females at 580nm, while Biggley et al. (1967) reported males at 568nm and females at 566nm. These within-species differences (17nm in males and 14nm in females) are greater than the variation we observed in the species we measured (Fig. 3), and it is unclear what caused this wide range. Sample sizes and levels of statistical significance were not reported in any of the previous studies, but in all instances female emissions were greener compared to their males, consistent with our findings. Our data suggest that female emission spectra are under a different selection regime than those of their males, as has been documented for other flash signal traits (Stanger-Hall and Lloyd 2015). One possibility is that the emissions of female fireflies are greener than their males because of the different microhabitat of signaling female fireflies, concordant with the reflectance hypothesis. Females tend to signal from vegetation and thus can use the reflectance of their light emissions off the green leaves to amplify their signal and increase their visibility to patrolling males. As a next step, this hypothesis should be tested in more depth by taking ambient light measurements and reflectance data of the signaling background for females and males of different species across different environments.

Larval light

Bioluminescence is omnipresent in all firefly larvae, uniting all species in Lampyridae. Larval light organ peak wavelengths in the three measured species were at the green end (below 555nm) of the range of emission spectra observed across firefly species (Fig. 3). Similar to our findings, the larvae of three species of European fireflies show little light color variation and produce green light, with peak wavelengths of 546nm (from the ventral surface: DeCock 2004), and Brazilian Cratomorphus larvae emit at 550nm (Viviani et al. 2004). Our data, coupled with previous work, suggest that firefly larvae emit green light across most, and perhaps all, species.

There are several explanations for why firefly larvae may all emit green light. Firefly larvae produce emission spectra with peak wavelengths within the hypothesized insect ancestral peak visual sensitivity (Lall et al. 1980, Eguchi et al, 1984). Larvae tend to be active late in the night (Dreisig 1974) when ambient light levels are too low for vegetation contrast to be relevant. As such, the green color of larval light emissions could also be the result of selection favoring a peak emission to which other species are especially sensitive. The larval stage of fireflies can last 1–2 years, and during this time, larvae would benefit from maximizing signal detection to either attract arthropod prey (Sivinski 1981), or to signal distastefulness to predators (Underwood et al. 1997, DeCock and Matthysen 2003), especially other arthropods, who show visual sensitivity peaks in the green and yellow range: (Briscoe and Chittka 2001).

Future directions

An obvious next step will be to measure ambient light directly in the field rather than using activity times and habitat classifications as proxies. Such a study will likely serve to strengthen the relationships found in this study. It would also be insightful to investigate the lack of a correlation between habitat and peak wavelength in P. pyralis (Fig. 5A). One possibility is that gene flow between populations swamps selection for population-specific spectral emissions (Supplementary Information Text S2, Fig. S5). Estimates of gene flow are needed in P. pyralis and other species to address this possibility. Finally, identifying the proximate mechanism(s) that generate the diversity of peak emissions observed within and between species, populations and individuals (Supplementary Materials, Text S1) is critical for understanding the target of natural selection that generates the observed variation.

Conclusion

Here we have presented evidence that the peak intensity wavelengths (i.e. bioluminescence colors) of firefly light signals are under selection to maximize signal contrast with ambient light. In populations that are active early in the evening, male fireflies generally emit yellower peak wavelengths, especially in more closed habitats. Females generally flash in darker habitats, lower in the vegetation, and (for the two species with female sample sizes n ≥ 10) their light signals are green-shifted relative to their males, which can be explained by selection to optimize reflection of their light emission off the green vegetation on which they rest (Endler 1993). Thus, both of the hypotheses generated from sensory drive (contrast and reflectance) appear to explain the evolution of the diversity in light colors emitted by adult fireflies. Larvae emit light in even darker environments and utilize green emissions, perhaps to maximize the probability of detection by heterospecific predators or prey.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the University of Georgia Research Foundation (DWH and KSH), the National Science Foundation (DEB-0074953 to KSH, graduate research fellowship to SES, and dissertation improvement grant DEB-1311315 to DWH and SES), the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the NIH (T32GM007103 to SES), and the University of Georgia center for undergraduate research (JCP). The authors would like to thank the following for permission and assistance in specimen collection: Allegheny National Forest, Gina Baucomb, Megan Behringer, Jim Bever, Tom Brightman (Longwood Gardens), Ashley Brown, the Cincinnati Center for Field Studies (University of Cincinnati), Raphael De Cock, the Entomological Society of Pennsylvania, Lynn Faust, Gordon and Doris Fisk, the David Fisk family, the Friehauf family, Great Smoky Mountains National Park, Indiana University, Paul Kissel (Eisenhower State Park, TX), Michael Marsh (Whitehall Experimental Forest, University of Georgia), Joel Martin (Dixon Center, Auburn University), Jerry McCollum (Wharton Conservation Center), David McNaughton (Fort Indiantown Gap), the Nature Conservancy (especially Jerry Skinner at the Woodbourne Preserve), Mike Quinn, David Queller, David Riskind (Texas permits), Willem Roosenburg, the Sander Family, Kevin Smith (Tyson Research Center), Tonya Saint John, Joan Strassman, Bill and Ann Thorpe, and Dorset Trapnell.

References

- Barber HS. North American fireflies of the genus Photuris. Smithson Misc Collect. 1951;117:1–58. [Google Scholar]

- Biggley WH, Lloyd JE, Seliger HH. Spectral Distribution of Firefly Light II. Journal of General Physiology. 1967;50(6 Part1):1661–1692. doi: 10.1085/jgp.50.6.1681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boughman JW. Divergent sexual selection enhances reproductive isolation in sticklebacks. Nature. 2001;411:944–948. doi: 10.1038/35082064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branham MA, Wenzel JW. The origin of photic behavior and the evolution of sexual communication in fireflies (Coleoptera: Lampyridae) Cladistics. 2003;19:1–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1096-0031.2003.tb00404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briscoe A, Chittka DL. The evolution of color vision in insects. Annual Reviews of Entomology. 2001;46:471–510. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ento.46.1.471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buck JB. Spectrometric data on firefly light. Proc Rochester Acad Sci. 1941;8:14–21. (cited in Seliger and McElroy 1964) [Google Scholar]

- Carlson AD, Coopeland J, Randerman R, Bulloch AGM. Role of interflash intervals in a firefly courtship (Photinus macdermotti) Animal Behavior. 1976;24:786–792. [Google Scholar]

- Dariba D, Taboada GL, Doallo R, Posada D. jModelTest 2: more models, new heuristics and parallel computing. Nature Methods. 2012;9:772. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darwin C. The expression of the emotions in man and animals. John Murray; London: 1872. [Google Scholar]

- De Cock R, Matthysen E. Glow-worm larvae bioluminescence (Coleoptera: Lampyridae) operates as an aposematic signal upon toads (Bufo bufo) Behavioral Ecology. 2003;14:103–108. [Google Scholar]

- DeCock R. Larval and adult emission spectra of bioluminescence in three European firefly species. Photochemistry and Photobiology. 2004;79(4):339–342. doi: 10.1562/2003-11-11-RA.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeVoe RD, Small RJW, Zvargulis JE. Spectral sensitivities of wolf-spider eyes. J Gen Physiol. 1969;54:1–32. doi: 10.1085/jgp.54.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dreisig H. Observations on the luminescence of the larval glowworm, Lampyris noctiluca L. (Col. Lampyridae) Insect Systematics & Evolution. 1974;5:103–109. [Google Scholar]

- Drummond AJ, Suchard MA, Xie D, Rambaut A. Bayesian phylogenetics with BEAUti and the BEAST 1.7. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 2012;29:1969–1973. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mss075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar RC. MUSCLE: a multiple sequence alignment method with reduced time and space complexity. BMC Bioinformatics. 2004;19:113. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-5-113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eguchi E, Nemoto A, Meyer-Rochow VB, Ohba N. A comparative study of spectral sensitivity curves in three diurnal and eight nocturnal species of Japanese fireflies. Journal of insect physiology. 1984;30(8):607–612. [Google Scholar]

- Endler JA. Natural selection on color patterns in Poecilia reticulata. Evolution. 1980;34:76–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1980.tb04790.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endler JA. Natural and sexual selection on color patterns in Poeciliid fishes. Environmental Biology of Fishes. 1983;9:173–190. [Google Scholar]

- Endler JA. Predation, light intensity, and courtship behaviour in Poecilia reticulata. Animal Behaviour. 1987;35:1376–1385. [Google Scholar]

- Endler JA. Variation in the appearance of guppy color patterns to guppies and their predators under different visual conditions. Vision Research. 1991;31:587–608. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(91)90109-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endler JA. Signals, signal conditions, and the direction of evolution. American Naturalist. 1992;139:S125–S153. [Google Scholar]

- Endler JA. The color of light in forests and its implications. Ecological Monographs. 1993;63:2–27. [Google Scholar]

- Fender KM. The genus Phausis in America north of Mexico (Coleoptera-Lampyridae) Northwest Science. 1966;40:83–95. [Google Scholar]

- Garland T, Jr, Harvey PH, Ives AR. Procedures for the analysis of comparative data using phylogenetically independent contrasts. Systematic Biology. 1992;41:18–32. doi: 10.2307/2992503. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Garland T, Jr, Midford PE, Ives AR. An introduction to phylogenetically based statistical methods, with a new method for confidence intervals on ancestral states. American Zoologist. 1999;39:374–388. [Google Scholar]

- Garland T, Jr, Ives AR. Using the past to predict the present: Confidence intervals for regression equations in phylogenetic comparative methods. American Naturalist. 2000;155:346–364. doi: 10.1086/303327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garland T, Jr, Dickerman AW, Janis CM, Jones JA. Phylogenetic analysis of covariance by computer simulation. Systematic Biology. 1993;42:265–292. [Google Scholar]

- Garland T, Bennett AF, Rezende EL. Phylogenetic approaches in comparative physiology. J Exp Biol. 2005;208:3015–3035. doi: 10.1242/jeb.01745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grafen A. The phylogenetic regression. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B. 1989;326:119–157. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1989.0106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green JW. Revisions of the nearctic species of Photinus (Lampyridae-Coleoptera) Proc Calif Acad Sci Ser. 1956;4:561–613. [Google Scholar]

- Green JW. Revision of the nearctic species of Pyractomena (Coleoptera: Lampyridae) Wasmann Journal of Biology. 1957;15:237–284. [Google Scholar]

- Guindon S, Gascuel O. A simple, fast and accurate method to estimate large phylogenies by maximum-likelihood. Syst Biol. 2003;52:696–704. doi: 10.1080/10635150390235520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guindon SJ, Dufayard F, Lefort V, Anisimova M, Hordijk W, Gascuel O. New algorithms and methods to estimate maximum-likelihood phylogenies: Assessing the performance of PhyML 3.0. Syst Biol. 2010;59:307–21. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/syq010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnsen S, Kelber A, Warrant EJ, Sweeney AM, Widder EA, Lee RL, Jr, Hernández-Andrés J. Crepuscular and nocturnal illumination and its effects on color perception by the nocturnal hawkmoth Deilephila elpenor. J Exp Biol. 2006;209:789–800. doi: 10.1242/jeb.02053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JG, Kim I, Bae JS, Jin BR, Kim KY, Kim SE, Choi JY, Choi YC, Lee KY, Sohn HD, Noh SK. Genetic subdivision of the firefly, Luciola lateralis (Coleoptera: Lampyridae), in Korea determined by mitochondrial COI gene sequences. Korean Journal of Genetics. 2001;23:203–219. [Google Scholar]

- Lall AB, Seliger HH, Biggley WH, Lloyd JE. Ecology of colors of firefly bioluminescence. Science. 1980;210:560–562. doi: 10.1126/science.210.4469.560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leal M, Fleishman LJ. Evidence for habitat partitioning based on adaptation to environmental light in a pair of sympatric lizard species. Proc R Soc Lond Ser. 2002;B269:351–359. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2001.1904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leal M, Fleishman LJ. Differences in visual signal design and detectability between allopatric populations of Anolis lizards. The American Naturalist. 2004;163:26–39. doi: 10.1086/379794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis SM, Cratsley CK. Flash signal evolution, mate choice, and predation in fireflies. Annu Rev Entomol. 2008;53:293–321. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ento.53.103106.093346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd JE. Studies on the Flash Communication System of Photinus Fireflies: Museum of Zoology, University of Michigan Misc. Publ. 1966;130:1–95. [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd JE. Flashes of Photuris fireflies: Their value and use in recognizing species. The Florida Entomologist. 1969a;52:29–35. [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd JE. Flashes, behavior and additional species of Nearctic Photinus fireflies (Coleoptera: Lampyridae) Colleopt Bull. 1969b;23:29–40. [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd JE. Bioluminescence and communication in insects. Annual review of Entomology. 1983;28:131–160. [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd JE. Evolution of a firefly flash code. Florida Entomologist. 1984;67(2):228–239. [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd JE. Firefly semiosystematics and predation: a history. Florida Entomologist. 1990;73:51–66. [Google Scholar]

- Luk SPL, Marshall SA, Branham MA. The fireflies of Ontario (Coleoptera: Lampyridae) Canadian Journal of Arthropod Identification. 2011;16:1–105. [Google Scholar]

- Maddison WP, Maddison DR. Mesquite: a modular system for evolutionary analysis. 2011 Version 2. 75. http://mesquiteproject.org.

- Ohba N. Flash communication of the firefly Hotaria parvula. Zool Mug Tokyo. 1981;90:702. [Google Scholar]

- Purvis A. A composite estimate of primate phylogeny. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B. 1995;348:405–421. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1995.0078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sander SE, Hall DW. Variation in opsin genes correlates with signalling ecology in North American fireflies. Molecular ecology. 2015;24:4679–4696. doi: 10.1111/mec.13346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seehausen O, Terai Y, Magalhaes IS, Carleton KL, Mrosso HD, Miyagi R, et al. Speciation through sensory drive in cichlid fish. Nature. 2008;455:620–626. doi: 10.1038/nature07285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seliger HH, Buck JB, Fastie WG, McElroy WD. The spectral distribution of firefly light. The Journal Of General Physiology. 1964;48:95–104. doi: 10.1085/jgp.48.1.95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seliger HH, McElroy WD. The colors of firefly bioluminescence: enzyme configuration and species-specifity. PNAS. 1964;52:75–81. doi: 10.1073/pnas.52.1.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seliger HH, Lall AB, Lloyd JE, Biggley WH. On the colors of firefly bioluminescence. I. An optimization model. Photochemistry and Photobiology. 1982a;36:673–680. [Google Scholar]

- Seliger HH, Lall AB, Lloyd JE, Biggley WH. The colors of firefly bioluminescence II. Experimental evidence for the optimization model. Photochemistry and Photobiology. 1982b;36:681–688. [Google Scholar]

- Simon C, Frati F, Beckenbach A, Crespi B, Liu H, Flook P. Evolution, weighting, and phylogenetic utility of mitochondrial gene-sequences and a compilation of conserved polymerase chain-reaction primers. Annals of the Entomological Society of America. 1994;87:651–701. [Google Scholar]

- Sivinski J. Arthropods Attracted to Luminous Fungi. Psyche. 1981;88:383–390. [Google Scholar]

- Sokal RR, Rohlf FJ. Biometry: the principles and practice of statistics in biological research. 3. W. H. Freeman and Co; New York: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Stanger-Hall KF, Lloyd JE, Hillis DM. Phylogeny of North American fireflies (Coleoptera: Lampyridae): Implications for the evolution of light signals. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 2007;45:33–49. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2007.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanger-Hall KF, Lloyd JE. Flash signal evolution in Photinus fireflies: Character displacement and signal exploitation in a visual communication system. Evolution. 2015;69:666–682. doi: 10.1111/evo.12606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Underwood TJ, Tallamy DW, Pesek JD. Bioluminescence in firefly larvae: a test of the aposematic display hypothesis (Coleoptera: Lampyridae) Journal of Insect Behavior. 1997;10:365–370. [Google Scholar]

- Viviani VR, Arnoldi FG, Brochetto-Braga M, Ohmiya Y. Cloning and characterization of the cDNA for the Brazilian Cratomorphus distinctus larval firefly luciferase: similarities with European Lampyris noctiluca and Asiatic Pyrocoelia luciferases. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part B: Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 2004;139:151–156. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpc.2004.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfram Research. Mathematica. Champaign, Illinois: Wolfram Research, Inc; 2010. Edition: Version 8.0. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.