Abstract

The vulnerability-stress-adaptation model guided this examination of the impact of daily fluctuations in the symptoms and co-occurring behavior problems of children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) on parents’ couple problem-solving interactions in natural settings and as these interactions spontaneously occur. A 14-day daily diary was completed by mothers and fathers in 176 families who had a child with ASD. On each day of the diary, parents separately reported on the child with ASD's daily level of symptoms and co-occurring behavior problems and the topic and level of negative affect in their most meaningful or important daily couple problem-solving interaction. Multilevel modeling was used to account for the within-person, within-couple nested structure of the data. Results indicated that many parents are resilient to experiencing a day with a high level of child ASD symptoms and co-occurring behavior problems and do not report more negative couple problem-solving interactions. However, household income, level of parental broader autism phenotype, and presence of multiple children with special care needs served as vulnerability factors in that they were related to a higher overall rating of negative affect in couple interactions and moderated the impact of reporting a day with a high level of child ASD symptoms and co-occurring behavior problems on next-day ratings of negative couple problem-solving interactions. The magnitude of these effects was small. Understanding mechanisms that support adaptive couple interactions in parents of children with ASD is critical for promoting best outcomes.

Keywords: autism, marital, couple, parenting stress, vulnerability-stress-adaptation, disability

There is theoretical and empirical evidence to suggest that child-related challenges associated with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) influence parents’ couple interactions. The vulnerability-stress-adaptation model theorizes that stressors originating outside of the marital relationship, along with vulnerabilities in one or both partners, contribute to negative couple interactions and the eventual dissolution of marriages (Karney & Bradbury, 1995). Children with ASD exhibit a stressful profile of impairments in social communication and repetitive behaviors and/or interests (American Psychiatric Association, 2013) and often engage in high levels of co-occurring behavior problems such as inattention, anxiety, and disruptive behaviors (Hartley, Sikora, & McCoy, 2008; Simonoff et al., 2006). Mothers and fathers of children with ASD report higher levels of parenting stress and poorer psychological well-being as compared to parents of children without disabilities, as well as parents of children with other types of disabilities (e.g. Ekas & Whitman, 2010; Hartley, Seltzer, Head, & Abbeduto, 2012). The level of the child's ASD symptoms and co-occurring behavior problems has been shown to account for a large part of these poor outcomes in the psychological well-being of individual parents (Abbeduto et al., 2004; Lecavalier et al., 2006). Virtually nothing is known about the extent to which child-related challenges associated with ASD also serve as a stressor at the couple-level for parents’ daily couple interactions.

The few studies that have examined marital quality in the context of having a child with ASD indicate that, on average, parents of children with ASD report a lower level of marital satisfaction (Gau, Chou, Lee, Wong, & Wu, 2012) and higher rate of divorce (Hartley et al., 2010) as compared to parents of children without disabilities. However, findings have varied (Freedman, Kalb, Zablotsky, & Stuart, 2012), and studies indicate wide variability in outcomes with many parents of children with ASD reporting longstanding and highly satisfying marriages (Gau et al., 2012; Hartley, Barker, Seltzer, Greenberg, & Floyd, 2011). In addition, there is evidence that differences in global levels of marital satisfaction are linked to differences in global levels of co-occurring behavior problems, as examined in grown children with ASD over relatively long study periods. Notably, in a sample of 199 married mothers of adolescents and adults with ASD, the son or daughter with ASD's severity of co-occurring behavior problems was found to negatively co-vary with the mother's level of marital satisfaction across 4 time points spanning 8.5 years (Hartley, Barker, Baker, Seltzer, & Greenberg, 2012). The present study builds on previous findings by using a daily-level diary approach and applying the vulnerability-stress-adaptation model to examine proximal mechanisms for the impact of child-related challenges on the day-to-day couple interactions of parents of children with ASD in natural settings and as they spontaneously occur.

The vulnerability-stress-adaptation model posits that two factors contribute to negative couple interactions (Karney & Bradbury, 1995). First, partners may have vulnerabilities (e.g., stable or longstanding characteristics such as personality traits) that reduce their ability to engage in adaptive couple interactions (e.g., positive, effective couple problem-solving). Second, stressors external to the marital relationship can impede partners from engaging in adaptive couple processes. In other words, couples who might normally demonstrate adaptive couple interactions will be less likely to exercise these processes under stressful conditions. For example, in a study of recently married couples, spouses who generated a high number of charitable explanations for their partner's negative behavior during times of low stress, generated a low number of such explanations during times of high stress, and instead were more likely to blame their partner for the negative behaviors (Neff & Karney, 2004). Finally, according to the vulnerability-stress-adaptation model, vulnerabilities and stressors interact; partners at greatest risk for negative couple interactions are those with vulnerabilities who also encounter stressors.

The vulnerability-stress-adaptation model has been used to examine the impact of several types of stressors on couple interactions including work stress, health, and life transitions (e.g., Cutrona at el., 2011; Doss, Rhoades, Stanley & Markman, 2009), and may provide a useful framework to elucidate the role of child-related challenges as potential stressors on the couple interactions of parents of children with ASD. Previous studies on the vulnerability-stress-adaptation model have focused on global measures collected at one time point or across years; yet this model may also be useful at a daily level. If child-related challenges associated with ASD act as a stressor for the daily couple interactions of parents, one implication may be that couples frequently interact about the child with ASD, as opposed to other topics, and these couple interactions are associated with a higher level of negative affect than interactions about other topics. Thus, in the current study, we examined the frequency and level of negative affect related to spontaneously-occurring daily couple problem-solving interactions (i.e., minor or major interaction in which something needed to be worked out and/or there was ‘give and take,’ a difference of opinion, or differing points of view; Cummings, Goeke-Morey, & Papp, 2003) about the child with ASD as compared to other topics across a 14-day period. Moreover, if child-related challenges associated with ASD serve as a stressor on daily couple interactions, then fluctuations in the level of child-related challenges from one day to the next may be associated with fluctuations in couple interactions. Thus, we also examined whether experiencing a day with a high level of symptoms and co-occurring behavior problems by the child with ASD resulted in a higher level of negative affect in parents’ couple problem-solving interactions the next-day.

Finally, in line with the vulnerability-stress-adaptation model, we sought to identify vulnerabilities that make some parents of children with ASD at risk for experiencing a higher level of negative affect in couple problem-solving interactions. In our daily-level approach, vulnerabilities were conceptualized as stable personality traits and longstanding family circumstances. Three potential vulnerability factors were considered: low household income, having multiple children with special care needs, and parental level of the broader autism phenotype (BAP). First, low household income is a risk factor for negative couple interactions in the general population (Bramlett & Mosher, 2002), as financial stress contributes to family and couple stress. Household income may be particularly important for fostering adaptive couple interactions in parents of children with ASD; due to the high out-of-pocket expenses of ASD services (Liptak et al., 2006), a higher household income translates into more access to ASD services and supports. Indeed, in a previous study, household income was positively related to level of marital satisfaction in a sample of 199 mothers of adolescents and adults with ASD (Hartley et al., 2012). Thus, parents of children with ASD with lower household incomes may be at risk for a higher level of negative affect in couple interactions broadly, and their couple interactions may be more sensitive to the effects of a day with a high level of child-related challenges than parents with higher household income.

Second, due to the genetic underpinnings of ASD, parents who have a child with ASD are more likely to have additional children with ASD or other types of disabilities or mental health conditions (e.g., Ozonoff et al., 2011; Petalas, Hastings, Ash, Lloyd, & Dowey, 2009; Ben-YIzhak et al., 2011). Due to heightened caregiving challenges, having multiple children with special care needs may put parents at risk for higher levels of negative affect in couple problem-solving interactions broadly, and in particular when faced with a day with a high level of challenges by their child with ASD. Third, the genetic underpinnings of ASD also mean that a subset of parents of children with ASD evidence their own ASD-like traits, often at milder levels, referred to as BAP, such as rigid or anxious/neurotic personality characteristics and difficulties with social communication (Constantino et al., 2006; Losh et al., 2008). Having a high level of BAP may be a risk factor for negative couple problem-solving interactions, independent of having a child with ASD. Moreover, these traits may make parents less able to cope with a day with a high level of challenges by their child with ASD.

The specific aims of the present study were to: 1) compare the frequency and level of negative affect in spontaneously-occurring couple problem-solving interactions about the child with ASD as compared to other topics in couples who had a child with ASD; 2) evaluate the impact of the child with ASD's symptoms and co-occurring behavior problems on the level of negative affect in parents’ couple problem-solving interactions the next-day; and 3) examine the extent to which household income, having multiple children with special health needs, and parental level of BAP serve as vulnerability factors for negative affect in couple problem-solving interactions broadly, and moderate the impact of experiencing a day with a high level of symptoms and co-occurring behavior problems by the child with ASD.

Descriptive statistics and repeated measure analysis of variance were used to compare the frequency and level of negative affect of the various topics of daily couple problem-solving interactions. Multilevel modeling (MLM) was used to examine the within-person association between previous-day level of the child with ASD's symptoms and co-occurring behavior problems on level of negative affect in couple problem-solving interactions, while accounting for mothers’ and fathers’ average ratings of the child ASD symptoms and co-occurring behavior problems, across a 14-day daily diary in a sample of 176 couples who have a child with ASD. Mothers and fathers separately reported on the child with ASD's daily level of symptoms and co-occurring behavior problems and the topic and level of negative affect in their most meaningful or important daily couple problem-solving interaction. We evaluated the between-parent effect of household income, having multiple children with special care needs, and parental level of BAP on the intercept of level of negative affect in couple problem-solving interactions. Finally, we examined the extent to which these variables moderated the association between previous-day level of the child with ASD's symptoms and co-occurring behavior problems and level of negative affect in the couple problem-solving interaction.

We hypothesized that parents’ couple problem-solving interaction would be about the child with ASD more often than other topics and that couple problem-solving interactions about the child with ASD would be associated with a higher level of negative affect than couple problem-solving interactions about other topics. At a within-person level, reporting a day with a higher level of symptoms and co-occurring behavior problems by the child with ASD was hypothesized to predict a higher level of negative affect in the couple problem-solving interaction the next-day. Parents with lower household income, multiple children with special care needs, and higher levels of BAP were hypothesized to report a higher overall level of negative affect in their couple problem-solving interactions. Moreover, these parents were expected to be most sensitive to the effects of a day with a higher level of symptoms and co-occurring behavior problems by the child with ASD.

Method

Participants in the present study completed Time 1 of an ongoing longitudinal study including 184 couples who had a child with ASD. Participants were recruited through mailings to families of children with an educational label of ASD in schools, fliers posted at ASD clinics and in community settings (e.g. libraries), and research registries. Study eligibility criteria included being the parent of a child aged 5-12 years with a diagnosis of ASD as documented by medical or educational records (had to include the Autism Diagnosis Observation Schedule [ADOS; Lord et al., 2000]), and in a long-term relationship in which both parents live together. In addition, all children met or exceeded the ASD cutoff on the Social Communication Questionnaire (SCQ; Rutter, Bailey, & Lord, 2003) as reported on by parents. From this larger sample, both partners from 176 couples took part in a 14-day daily diary and were included in the present analyses. Parents (n = 8) who opted out of the 14-day daily diary did not differ from the parents who completed diary entries in parent age, education, or race/ethnicity, child age, or household income. In our analytic sample (n = 176), the child with ASD had been adopted in 4 families; all adoptions had occurred at least 5 years prior. Two of the couples were not married but had lived together for at least 8 years. In 13 couples, one parent was a step-parent; these couples had been together for at least 3 years. Twelve of the families had more than one child with ASD aged 5-12 years; in these families, the oldest child was selected as the target child and reported on for the present study. The socio-demographics for the 176 families are displayed in Table 1. On average, the child with ASD was aged 8.81 years (SD = 1.53). The mean age of parents was 37.45 years (SD = 3.52) and the median household income was $70 to $79K.

Table 1.

Socio-demographic characteristics of Families of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder

| Couples (n = 176) | |

| Married (n,%) | 174 (98.9%) |

| Both biological parents (n,%) | 159 (90.3%) |

| Length of dating (M [SD]) | 14.56 (4.83) |

| Length of marriage (M [SD]) | 11.93 (4.81) |

| Household income (M [SD]) | $80-89,999 ($40,210) |

| Parents (n = 352) | |

| Mother age in yrs (M [SD]) | 38.69 (5.20) |

| Father age in yrs (M [SD]) | 40.93 (5.80) |

| Education (n,%) | |

| Less than high school degree | 13 (3.5%) |

| High school degree/GED | 33 (8.7%) |

| Some college | 60 (15.9%) |

| College Degree | 189 (50.0%) |

| Graduate/professional degree | 77 (19.0%) |

| Race/ethnicity (n[%]) | |

| Caucasian, Non-Hispanic | 336 (89.4%) |

| Hispanic | 26 (6.9%) |

| African-American | 4 (1.1%) |

| American Indian | 1 (0.3%) |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 9 (2.4%) |

| Child with autism spectrum disorder (N = 176) | |

| Age in yrs (M[SD]) | 7.97 (2.30) |

| Male (n[%]) | 156 (85.2%) |

| Intellectual disability (n[%]) | 64 (34.8%) |

| Age of diagnosis in yrs (M[SD]) | 4.02 (1.86) |

| Global Behavior Problems (M[SD]) | 65.44 (10.00) |

| Global ASD Symptoms (M[SD]) | 104.81 (29.71) |

Note. Global Behavior Problems assessed through the CBCL and global ASD symptoms assessed through the SRS.

During a 2.5 hour home or lab visit, parents were interviewed and independently completed questionnaires about family socio-demographics and a variety of family dynamics. Parents then independently completed a daily diary for 14 consecutive days in which they reported on daily couple problem-solving interactions and their child with ASD's symptoms and co-occurring behavior problems. The majority of parents completed the daily diary online (94%), while a minority completed via an IPod Touch that did not require internet access (6%). Parents were each paid $75 for completing the daily diary.

Measures

Family socio-demographics

Family socio-demographics were reported on by parents and included in models to control for any effect on the constructs of interest. The race/ethnicity of parents was coded as Caucasian, non-Hispanic (0) versus other (1). Parent educational level was coded: less than high school degree (0), high school diploma or General Equivalency Diploma (1), some college (2), college degree (3), some graduate school (4), and graduate/professional degree (5). The duration of the relationship was coded in years, as jointly reported on by mothers and fathers. Mothers and fathers reported their number of children and this information was used to calculate family size. The child with ASD's date of birth was used to calculate age (in years). The child with ASD was considered to have intellectual disability (ID) if they had a medical diagnosis of ID and/or met criteria for ID based on IQ and adaptive behavior testing, based on review of medical and/or educational records.

Vulnerabilities

Parents reported on their household income, which was coded from 0-13, starting at ≤$9,999 (0) and increasing by $20,000 intervals to ≥$160,000 (13). Parents reported on the presence of an additional child with a disability or mental health condition; this variable was dichotomously coded as absence (0) versus presence (1) of multiple children with special care needs. Parents independently completed the Broader Autism Phenotype Questionnaire (BAPQ; Hurley, Losh, Parlier, Reznick, & Piven, 2007) to assess their own level of BAP traits. The BAPQ was derived from a direct assessment measure of personality and language characteristics associated with ASD (Piven, et al., 1990). The measure includes 36 statements rated from 1 (very rarely) to 6 (very often) and has been found to have good internal consistency (Hurley et al., 2007).

Daily Child ASD Symptoms and Co-Occurring Behavior Problems

The level of the child's ASD symptoms and co-occurring behavior problems were independently reported on by mothers and fathers each day of the 14-day daily diary. Parents rated the severity of their child's ASD symptoms in the previous 24 hours from 1 (not at all ) to 7 (very severe) using 3 items capturing impairment in social reciprocity (“Did your child have problems not wanting to interact with others or problems interacting with others in inappropriate ways?”), communication (“Did your child have problems communicating with others [e.g., unusual or odd language or ways of communicating or not understanding others]?”), and restricted and/or repetitive behaviors (“Did your child display any repetitive behaviors [e.g., flapping arms or body rocking] or restricted interests [e.g., only wants to discuss one topic or play one activity]?”). These items were summed into a composite score. The mean of this composite score was positively correlated with the Social Responsiveness Scale – Second Edition (SRS-2; Constantino & Gruber, 2012) in mothers (r = .45, p < .01) and fathers (r = .53, p < .01) in the present sample.

The daily level of the child with ASD's co-occurring behavior problems during the previous 24 hours was reported on using a modified version of the Scales of Independent Behavior-Revised (SIBR; Bruininks, Woodcock, Weatherman, & Hill, 1996). On each day of the daily diary, parents separately rated the frequency (present vs. absent) and severity (5 point scale) of eight types of behavior problems. The daily frequency x severity summed across all 8 types of co-occurring behavior problems on each day of the daily diary was used in the present analyses. The SIB-R was developed for individuals with developmental disabilities and has been shown to have high concurrent validity (Bruininks et al., 1996). This modified version of the measure has been used in previous daily diary studies (Hartley et al., 2012b; Seltzer et al., 2010) and found to have adequate variability within- and between- mothers. The mean daily SIBR score was significantly positively correlated with the total score on the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach & Rescorla, 2000, 2001) for mothers (r = .55, p = .01) and fathers (r = .62, p < .01) in the present sample.

Daily Couple Problem-Solving Interaction

Parents independently reported on the most important or meaningful couple problem-solving interaction on each day of the 14-day daily diary. Couple problem-solving interactions were defined as interactions in which something had to be worked out and/or involved some ‘give and take’, a difference of opinion, or differing points of view (including misunderstandings). These interactions could be minor or major and mostly positive or mostly negative (Cummings et al., 2003). Parents reported on the topic(s) of this interaction with options: habits (habit of one or both partner such as leaving dishes on counter, etc.), child with ASD (behavior of child, parenting issues, etc.), relatives (in-laws, family, etc.), leisure (how to spend free time, preferred activities, etc.), money (spending, wages, bills, etc.), friends (friendships, time/activity with friends, etc.), work (jobs, time spent at work, etc.), personality (personality traits such as being insensitive or too outgoing, or strengths of character, etc.), intimacy (closeness, sex, too much/too little intimacy, etc.), commitment (commitment to relationship or expectations about relationship, etc.), communication (styles of communicating, feeling listened to or understood by each other, etc.), chores (household responsibilities, etc. ), and other. Parents rated their level of three negative emotions (sad, angry, and afraid) related to this interaction using a 10-point scale (1 = None and 10 = High). These three ratings were summed to create our measure of level of negative affect.

Data Analysis Plan

Overall, 8% of mothers and 12% of fathers had an individual item missing on a measure. In all but 4 cases, at least 90% of the items on the scale had been completed and thus the mean score on the scale for the person was imputed for the missing items. Histograms were conducted to ensure that data were normally distributed without skew. We then examined the frequency of the various topics of couple problem-solving interactions and compared the average within-person level of negative affect for each topic using repeated measure one-way analyses of variance (ANOVA) and follow-up paired sample t-tests (α ≤ .01).

To examine our second and third study questions, and account for the within-person and within-couple nested structure of the data, dyadic multilevel modeling (MLM) analyses (Bolger & Laurenceau, 2013) were conducted using the hierarchical linear modeling program (Raudenbush et al., 2011). Level of negative affect in the couple problem-solving interaction was the dependent measure. Level 1 variables included time (un-centered), mother (un-centered), father (un-centered), mother reported previous-day level of child ASD symptoms (group-mean centered), mother reported previous-day level of child co-occurring behavior problems (group-mean centered), father reported previous-day level of child ASD symptoms (group-mean centered), father reported previous-day level of child co-occurring behavior problems (group-mean centered), mother reported previous-day level of negative affect in the couple problem-solving interaction (group-mean centered), and father reported previous-day level of negative affect in the couple problem-solving interaction (group-mean centered). Level 2 variables included the potential vulnerability factors (household income, multiple children with special care needs, and parent level of BAP). Parent ethnicity, parent education, marital duration, family size, child age, and child ID status were included at Level 2 to account for their between-parent effects on the dependent measure. We also included the average previous-day level of the child with ASD's symptoms and co-occurring behavior problems in Level 2 to control for between-person effects of these variables on the dependent variable while assessing the within-person time-varying effects (Hoffman, 2015). The moderating effect of the potential vulnerability factors on the relation between previous-day level of child ASD symptoms and co-occurring behavior problems and level of negative affect in the couple problem-solving interaction was included in the models. Level 2 (between-person) continuous variables were grand-mean centered. Only consecutive day diary entries were included in the MLM model. In the MLM model, effect size r was calculated using the equation: r = sqrt [t2/(t2 + df)].

Results

Descriptive Statistics

On average, mothers completed 13.96 (SD = 2.04) and fathers completed 13.71 (SD = 2.74) days of the 14-day daily diary. Data for variables of interest (child ASD symptoms, child co-occurring behavior problems, and level of negative affect in the couple problem-solving interaction) were normally distributed without skew in mothers and fathers. Table 2 presents the means and standard deviations for the average daily level of child ASD symptoms, child co-occurring behavior problems, and level of negative affect in the couple problem-solving interaction for mothers and fathers. Paired sample t-tests comparing mother-father ratings within-couples, indicated that there was not a significant difference in the mean daily rating of level of child ASD symptoms (mothers: M = 8.87, SD = 4.10; fathers: M = 7.28, SD = 3.74; t (175) = 1.52, p = .31), child co-occurring behavior problems (mothers: M = 6.64, SD = 5.21; fathers: M = 4.56, SD = 4.21; t (175) = 0.67, p = .68), or negative affect in the couple problem-solving interaction (mothers: M = 7.24, SD = 3.46; fathers: M = 6.54, SD = 3.08; t (175) = 0.82, p = .55). Within-couples, mother-father mean daily ratings of child ASD symptoms (r = .57, p <.01), child co-occurring behavior problems (r = .56, p <.01), and level of negative affect in the couple problem-solving interaction (r = .45, p <.01) were significantly positively correlated.

Table 2.

Descriptive information on Topic of Most Meaningful or Important Daily Couple Problem-Solving Interaction

| Topic | % of days interaction about topic (M, [SD]) | % of Parents reporting at least one interaction about topic | Negative affect (M, [SD]) Possible Range: 0-30 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Habits | 10.76% (16.60) | 49.6% | 10.26 (9.19) |

| Leisure | 14.99% (19.81) | 57.7% | 5.50 (7.25) |

| Money | 16.06% (20.48) | 60.0% | 8.35 (8.81) |

| Personality | 10.56% (16.93) | 47.1% | 13.00 (9.71) |

| Child with ASD | 25.01% (25.62) | 71.7.% | 8.08 (7.70) |

| Other children* | 19.98% (21.53) | 59.5% | 7.92 (7.76) |

| Relatives | 9.67% (15.35) | 48.4% | 7.97 (0.64) |

| Friends | 4.67% (11.20) | 31.7% | 6.32 (9.09) |

| Work | 18.73% (21.14) | 70.1% | 7.42 (8.54) |

| Intimacy | 6.32% (11.22) | 38.4% | 7.69 (10.41) |

| Commitment | 4.04% (11.36) | 25.2% | 12.11 (10.44) |

| Communication | 15.07% (19.10) | 60.0% | 11.35 (9.78) |

| Chores | 20.33% (20.51) | 73.8% | 6.65 (7.55) |

| Other | 13.17% (18.40) | 54.8% | 7.21 (7.89) |

Note.

Other children only calculated for families with more than one child.

Table 2 displays the average within-person percentage of days that the most meaningful or important couple problem-solving interaction concerned each topic. The most common topic of the couple problem-solving interaction was the child with ASD (25%); although a subgroup of parents (29%) never reported a couple problem-solving interaction about the child with ASD. A repeated measure ANOVA indicated that there was a significant difference in the frequency of topics (F (13, 324) = 1343.41, p <.01). Follow-up paired sample-tests indicated that couple interactions about the child with ASD occurred more frequently than interactions about habits (t (357) = 9.71, p <.001), leisure (t (357) = 6.64, p < .001), money (t (357) = 5.41, p <.001), personality (t (357) = 9.43, p <.001), other children (t (312) = 2.53, p =.012), relatives (t (357) = 11.00, p <.001), friends (t (357) = 15.61, p <.001), work (t (357) = 4.04, p <.001), intimacy (t (357) = 12.44, p < .001), commitment (t (357) = 14.91, p < .001), communication (t (357) = 5.74, p < .001), chores (t (357) = 2.87, p =.005), and other (t (357) = 6.54, p < .001).

On average, at a within-person level, the mean level of negative affect for couple problem-solving interactions about the child with ASD, however, was mid-level in comparison to other topics. A repeated measure ANVOA indicated that there was a significant difference in the level of negative affect by topic (F (13, 324) = 192.24, p <.01). Follow-up paired sample t-tests indicated that couple problem-solving interactions about habits (t (357) = 4.12, p <.001), leisure (t (357) = 6.64, p < .001), personality (t (357) = 8.13, p < .001), commitment (t (357) = 7.73, p < .001), and communication (t (357) = 4.56, p < .001) had a higher level of negative affect than interactions about the child with ASD.

Previous-Day Level of Child ASD Symptoms and Co-Occurring Behavior Problems on Level of Negative affect in the Couple Problem-Solving Interaction

An intercept-only MLM model was first tested to examine variability in the association between previous-day level of child ASD symptoms and co-occurring behavior problems on level of negative affect in the couple problem-solving interaction for mothers and fathers. There was significant variability in the associations between previous-day level of child ASD symptoms and next-day level of negative affect in couple problem-solving interactions for mothers and fathers and in the association between previous-day level of child co-occurring behavior problems and level of negative affect in the couple problem-solving interaction for mothers. There was not significant variability in the association between previous-day level of child co-occurring behavior problems and level of negative affect in the couple problem-solving interaction for fathers and thus moderators were not examined for this association.

Table 3 presents the couple MLM model examining the extent to which previous-day level of child ASD symptoms and co-occurring behavior problems predicted level of negative affect in the couple problem-solving interaction, controlling for the autoregressive effect of the previous-day level of negative affect in the couple problem-solving interaction. There was a significant between-parent effect of the average level of previous-day child ASD symptoms on the intercept of level of negative affect in the couple problem-solving interactions in fathers. This same pattern occurred at a trend-level (p =.06) in mothers. For fathers, there was also a significant between-parent effect of household income and paternal level of BAP on the initial level of negative affect in the couple problem-solving interaction. Fathers with a lower household income and higher level of BAP reported a higher initial level of negative affect in the couple problem-solving interaction. In terms of control variables, ethnic minority fathers and those with a child without ID had a significantly higher initial level of negative affect in the couple problem-solving interaction. Effect sizes (rs = .16 -.26) were small for all associations.

Table 3.

Dyadic Multilevel Model of Previous-Day Level of Child with ASD's Symptoms and Co-Occurring Behavior Problems on Level of Negative Affect in Couple Problem-Solving in Mothers and Fathers

| Mother | Father | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unstandardized Coefficients (Standard Error) | Effect Size r | Unstandardized Coefficients (Standard Error) | Effect Size r | |

| Level 1 | ||||

| Intercept | 5.51 (0.90)** | .52 | 6.20 (0.71)** | .58 |

| Time | 0.008 (0.05) | .01 | −0.03 (0.04) | .06 |

| Previous Day Child ASD Symptoms | −0.04 (0.08) | .04 | −0.15 (0.09)+ | .14 |

| Previous Day Child Co-Occurring Behavior Problems | 0.11 (0.06)* | .16 | 0.08 (0.04) | .11 |

| Previous Day Negative Affect in Couple Problem-Solving | 0.01 (0.03) | .05 | 0.04 (0.03)+ | .14 |

| Level 2 | ||||

| Intercept | ||||

| Child Age | −0.30 (0.45) | .05 | −0.14 (0.41) | .03 |

| ID Status | −0.08 (0.51) | .01 | −0.88 (0.42)* | .16 |

| Family Size | −0.06 (0.12) | .04 | 0.18 (0.13) | .11 |

| Marital Duration | 0.41 (0.46) | .07 | 0.25 (0.40) | .05 |

| Parent Ethnicity | 0.94 (0.66) | .11 | 1.26 (0.49)* | .21 |

| Parent Education | −0.02 (0.11) | .02 | 0.19 (0.11) | .13 |

| Mean Previous Day Child ASD Symptoms | 0.17 (0.09)+ | .15 | 0.23 (0.08)** | .23 |

| Mean Previous Day Child Co-Occurring Behavior Problems | 0.02 (0.03) | .01 | 0.02 (0.06) | .03 |

| Household Income | −0.06 (0.07) | .07 | −0.15 (0.07)* | .19 |

| Multiple Children with Special Needs | 0.69 (0.71) | .08 | −0.70 (0.64) | .09 |

| Parent BAP | 0.01 (0.01) | .06 | 0.04 (0.01)** | .26 |

| Previous Day Child ASD Symptoms | ||||

| Household Income | −0.004 (0.01) | .03 | −0.005 (0.01) | .04 |

| Multiple Children Special Needs | 0.10 (0.13) | .06 | 0.25 (0.11)* | .19 |

| Parent BAP | 0.002 (0.003) | .05 | −0.001 (0.002) | .05 |

| Previous Day Child Co-Occurring Behavior Problems | ||||

| Household Income | −0.02 (0.009)* | .18 | ------ | |

| Multiple Children Special Needs | −0.09 (0.09) | .09 | ------ | |

| Parent BAP | −0.005 (0.002)* | .16 | ------ | |

| Random Effects Standard Deviation (Variance Estimates) | ||||

| Level 2 | ||||

| Intercept | 2.83 (8.03)* | 3.60 (12.97) | ||

| Time | 0.32 (0.10)** | 0.20 (0.04)* | ||

| Previous-Day Child ASD Symptoms | 0.38 (0.14)** | 0.34 (0.10)+ | ||

| Previous-Day Child Co-Occurring Behavior Problems | 0.27 (0.07)** | 0.16 (0.02) | ||

| Previous-Day Negative Affect in Couple Problem-Solving | 0.18 (0.03)** | 0.15 (0.02) | ||

Note.

p < .10

p < .05

p < .01.

Effect size r was calculated with the following equation: r = sqrt [t2/(t2 + df)].

When controlling for the between-parent effects of family socio-demographics, average level of child ASD symptoms and co-occurring behaviors, and moderating effects, previous-day level of the child's co-occurring behavior problems significantly positively predicted level of negative affect in the couple problem-solving interaction in mothers (effect size r = .16). Previous-day level of child ASD symptoms was not significantly related to level of negative affect in the couple problem-solving interaction in mothers. In fathers, there was a trend for previous-day level of child ASD symptoms to be related to level of negative affect in the couple problem-solving interaction but previous-day level of child co-occurring behavior problems was not significantly predictive of level of negative affect in the couple problem-solving interaction.

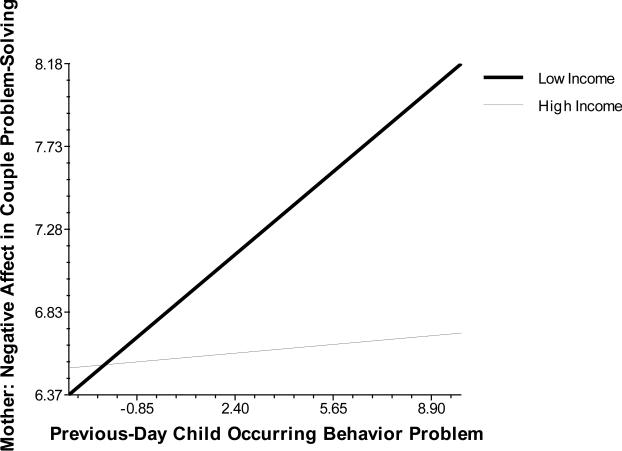

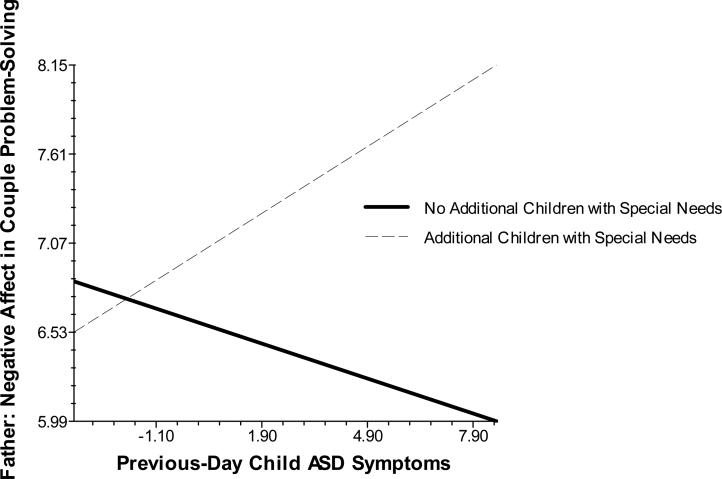

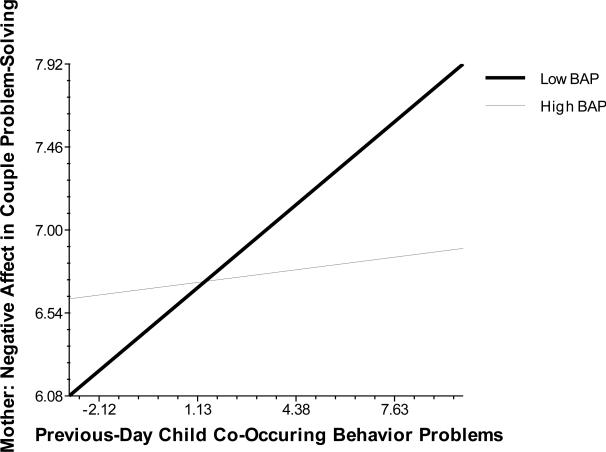

The moderating effect of the three potential vulnerability variables is also shown in Table 3. For mothers, there were significant moderating effects of household income and level of BAP on the association between the previous-day level of child co-occurring behavior problems and level of negative affect in the couple problem-solving interaction. As shown in Figure 1, in support of our prediction, there was only a positive association between previous-day level of child co-occurring behavior problems and level of negative affect in the couple problem-solving interaction for mothers with a lower household income. As shown in Figure 2, in contrast to our prediction, previous-day level of child co-occurring behavior problems had a stronger effect on level of negative affect in the couple problem-solving interaction for mothers with lower as opposed to higher level of BAP. There were no significant moderating effects associated with child ASD symptoms for the mothers. For the fathers, there were no significant moderating effects associated with behavior problems, but there was a moderating effect of presence of multiple children with special care needs on the association between previous-day level of child ASD symptoms and level of negative affect in the couple problem-solving interaction. As shown in Figure 3, in support of our hypothesis, there was a significant positive association between previous-day level of child ASD symptoms and level of negative affect in the couple problem-solving interaction for fathers with multiple children with special care needs. There was not a significant association between previous-day level of child ASD symptoms and level of negative affect in the couple problem-solving interaction for fathers who did not have additional children with special care needs. Significant effects for mothers and fathers were small in magnitude (rs = .16-.19)

Figure 1.

Moderating effect of household income on the association between previous-day level of the child with autism spectrum disorder's co-occurring behavior problems and level of negative affect in the couple problem-solving tasks in mothers.

Figure 2.

Moderating effect of presence of additional children with special care needs on the association between previous-day level of the child's autism symptoms and level of negative affect in the couple problem-solving tasks in fathers

Figure 3.

Moderating effect of level of broader autism phenotype on the association between previous-day level of the child with autism spectrum disorder's co-occurring behavior problems and level of negative affect in the couple problem-solving tasks in mothers

As a follow-up analysis, given the relatively high frequency of couple problem-solving interactions about the child with ASD, we wanted to know if couple problem-solving interactions about the child with ASD were more strongly influenced by a day with a high level of child-related challenges than couple problem-solving interactions about other topics. Thus, we re-ran our MLM model including interactions between the topic of the couple problem-solving interaction (i.e., child with ASD vs. other) and previous-day level of child ASD symptoms and co-occurring behavior problems. These interactions were not significantly (p > .05) predictive of level of negative affect in the couple problem-solving interaction in mothers (b = 0.003, SE = 0.003; b = 0.02, SE = 0.003) or fathers (b = 0.003, SE = 0.003; b = 0.02, SE = 0.003).

Discussion

The impact of child-related challenges associated with ASD on parents’ couple interactions has received little research attention, yet has important implications for understanding family support needs. Our findings indicate that, among parents of children with ASD, the most meaningful and important daily couple problem-solving interaction is frequently about the child with ASD (average of 25% of the days of the daily diary). However, couple problem-solving interactions about the child with ASD were not necessarily associated with high levels of negative affect. Couple problem-solving interactions related to closeness and connection in the couple relationship and partner behaviors (i.e., commitment, communication, personality, and habits) had a higher level of negative affect, at a within-person level, than interactions about the child with ASD for mothers and fathers. Moreover, there was no evidence that couple problem-solving interactions about the child with ASD were more strongly influenced by a day with a high level of child-related challenges than couple problem-solving interactions about other topics. Interestingly, the couple problem-solving interaction topics associated with the highest levels of negative affect (i.e., commitment, communication, personality, and habits) in parents of children with ASD overlap with the topics shown to be highly distressing for parents in the general population (Cummings, Goeke-Morey, & Papp, 2004); thus, in many ways, the couple problem-solving interactions of parents who have a child with ASD are no different from those of parents who have children without disabilities.

In support of our hypothesis, lower household income and higher level of BAP served as vulnerability factors for an overall higher level of negative affect in the couple problem-solving interaction in fathers of children with ASD, although the magnitude of these effects were small. Fathers of children with ASD with a lower household income may receive fewer supports and experience more financial stress, putting them at risk for negative couple interactions, and fathers who have a high level of BAP may behave in ways (e.g., more rigid and anxious) that contribute to negative couple problem-solving interactions. Household income and level of BAP were not related to the overall level of negative affect in the couple problem-solving interaction in mothers of children with ASD. Moreover, for both parents having multiple children with special care needs was not related to a higher overall level of negative affect in couple problem-solving interactions.

Several other family socio-characteristics were related to the overall level of negative affect in couple problem-solving interactions. Fathers of children with a higher level of ASD symptoms had a higher overall level of negative affect in couple problem-solving interactions and this was true at a trend-level for mothers. This pattern is consistent with our expectation that generally severe ASD symptoms are stressful for parents. Ethnic minority fathers had a higher overall level of negative affect in their couple problem-solving interactions than Caucasian, non-Hispanic fathers. This difference may be the result of limited access to and use of services and supports within some cultural groups (Mandell & Novak, 2011). Interestingly, fathers of children with ASD without ID had a higher overall level of negative affect in their couple problem-solving interactions than fathers of children with ASD and ID. Further research is needed to understand this effect. The types of challenges of children with ASD with average intellectual functioning differ from those of children with ASD and ID (e.g., Matson & Shoemaker, 2009), and this may influence stress spillover into couple interactions. Alternatively, earlier work hypothesized that couples may be more likely to attribute negative couple interactions to child-related stress if the child has ID (Floyd & Zmich, 1991).

Overall, our findings indicate that many parents of children with ASD successfully manage a day with a relatively high level of child ASD symptoms and/or co-occurring behavior problems such that there is no impact on next-day couple problem-solving interactions. This finding highlights within-group variability and the need to understand vulnerability versus resiliency in families of children with ASD. The present findings suggest that parental level of BAP, household income, and having multiple children with special health needs moderate the impact of experiencing a day with a high level of child-related challenges on couple problem-solving interactions, although the magnitude of these effects were also small. In support of our hypothesis, mothers with a lower household income experienced a higher level of negative affect in their couple problem-solving interaction following a day with a higher level of co-occurring behavior problems by their child with ASD. Intervention and supports related to ASD often require out-of-pocket expenses (Liptake et al., 2006), such that families with fewer financial resources may have fewer child or family services, and be less able to successfully cope with a day with high child-related challenges.

Mothers’ level of BAP also moderated the impact of reporting a day with a high level of co-occurring behavior problems by the child with ASD on level of negative affect in the couple problem-solving interaction. However, this finding was in contrast to our hypothesis. Mothers with a lower level of BAP were more sensitive to experiencing a day with a high level of co-occurring behavior problems by their child with ASD than were mothers with a higher level of BAP. As a result, at a within-person level, on days with a higher level of co-occurring behavior problems by the child with ASD, mothers with a lower level of BAP reported a higher level of negative affect in the couple problem-solving interaction than mothers with a lower level of BAP. Thus overall, it appears that BAP might be indexing a complex set of interpersonal behaviors that present unique challenges for parents, making fathers more likely to have negative couple interactions on average and mothers less responsive to child-related challenges. Future research to clarify the family effects of parental BAP.

Having additional children with special care needs moderated the impact of reporting a day with a high level of child-related challenges in fathers of children with ASD. Specifically, for fathers who had multiple children with special health care needs, experiencing a higher level of child ASD symptoms predicted a slightly higher level of negative affect in the couple problem-solving interaction the following day. In contrast, the couple problem-solving interactions of fathers who did not have additional children with special care needs were not impacted by previous-day level of child-related challenges. One hypothesis is that having multiple children with special care needs means that fathers take on higher levels of daily child caregiving responsibilities, and subsequently have fewer emotional reserves for managing the stress of a high level of challenges by the child with ASD.

Within-couples, mothers and fathers in the present study were largely in agreement in terms of the reported mean level of child ASD symptoms and co-occurring behavior problems, as well as mean level of negative affect in the couple problem-solving interaction, across the 14-day daily diary. This finding is consistent with previous reports that there are not marked mother-father differences in global reports of the child with ASD's behaviors (e.g., Davis & Carter, 2008) and/or in marital satisfaction (e.g., Hartley et al., 2011). Future studies should examine mother-father agreement at a daily level in couples who have a child with ASD and any impact on couple problem-solving interactions.

The present study has several strengths. Our daily diary approach allowed us to capture the spontaneous and natural fluctuations in daily level of child ASD symptoms and co-occurring behavior problems and level of negative affect in couple problem-solving interactions. Mothers and fathers separately completed the daily diary, allowing us to assess their unique parenting and couple experiences. We were able to account for couple-level dependency in the data by using MLM models. There were also limitations to the present study. We assessed negative affect in everyday couple problem-solving interactions which may involve relatively minor disagreement. In future studies, couple conflicts involving major disagreements should be assessed to understand their potentially unique association with child-related challenges in the context of ASD. The present sample was predominately Caucasian, non-Hispanic, which limits generalizability. However, this sample represents the Midwestern state from which the sample was recruited and reflects the population of children with ASD (Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 2014). The present sample also largely represents parents who remained married to the same partner until the child with ASD was aged 5-12 years; the couple problem-solving interactions of these parents may be healthier than those whose relationship did not remain intact. Using the vulnerability-stress-adaptation model, our stressor was daily level of child with ASD's symptoms and co-occurring behavior problems and vulnerability factors were stable personality traits (level of BAP) and longstanding family circumstances (household income and presence of additional children with special health needs). These longstanding family circumstances, however, could be considered as stressors in the context of global outcomes.

In summary, the present study focused on daily couple problem-solving interactions as a proximal mechanism that, overtime, may contribute to the erosion of marital satisfaction and put couples who have a child with ASD at risk for divorce. Our findings indicate that many parents are resilient to experiencing a day with a high level of child ASD symptoms and co-occurring behavior problems and do not report more negative couple problem-solving interactions. However, household income, level of parental BAP, and presence of multiple children with special care needs serve as double vulnerability factors, as they were associated with higher overall level of negative affect in couple interactions and they moderated the impact of experiencing a day with a high level of child ASD symptoms and co-occurring behavior problems on next-day couple problem-solving interactions in parents of children with ASD. Although the magnitude of associations was small, they still have meaningful implications for the well-being of families of children with ASD. Marital discord has considerable consequences for the psychological and physical health of both adults and children in the general population (e.g., El-Sheikh, Keiley, Erath, & Dyer, 2013; Whisman & Uebelacker, 2012). Thus, understanding mechanisms that hinder or facilitate adaptive everyday couple problem-solving interactions in parents of children with ASD has critical intervention implications. Marital education and therapies that discuss the role of child-related challenges as potential stressors on couple interactions and help couples learn effective problem-solving strategies may be important ways to improve couple interactions and should be aimed at vulnerable couples. Finally, the present study examined the effect of daily child ASD symptoms and co-occurring behavior problems on couple interactions. However, couple interactions may also influence the functioning of children with ASD, as has been shown in research on the general population (e.g., El-Sheikh, et al., 2013). Thus, further research is needed to examine these dynamic relations.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the National Institute on Mental Health (NIMH R01MH099190 to S. Hartley) and by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD; P30 HD03352 to A. Messing). We thank our team of collaborators and the families who generously participated in this study.

References

- Abbeduto L, Seltzer MM, Shattuck P, Krauss MW, Orsmond G, Murphy MM. Psychological well-being and coping in mothers of youths with autism, Down Syndrome, or Fragile X Syndrome. American Journal on Mental Retardation. 2004;109(3):237–254. doi: 10.1352/0895-8017(2004)109<237:PWACIM>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA. Manual for the ASEBA Preschool Forms & Profiles. University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, and Families; Burlington, VT: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA. Manual for the ASEBA School-Age Forms & Profiles. University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, and Families; Burlington, VT: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Publishing; Arlington, VA: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network Prevalence of Autism Spectrum Disorder among children aged 8 years – Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 11 sites, United States, 2010. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2014;63:1–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Yizhak N, Yirmiya n., Seidman I, ALon R, Lord C, Sigman M. Pragmatic language and school related linguistic abilities in siblings of children with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2011;41:750–760. doi: 10.1007/s10803-010-1096-6. doi: 10.1007/s10803-010-1096-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger N, Laurenceau JP. Intensive longitudinal methods: An introduction to diary and experience sampling research. Guilford Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bramlett MD, Mosher WD. Cohabitation, marriage, divorce, and remarriage in the United States (Vital and Health Statistics Series 23, No. 22) National Center for Health Statistics; Hyattsville, MD: 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruininks RH, Woodcock RW, Weatherman RF, Hill BK. Scales of independent behavior-revised. Riverside Publishing Company; Itasca, IL: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Constantino JN, Gruber CP. Social Responsiveness Scale, Second Edition (SRS-2) Western Psychological Services; Torrance, CA: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Constantino JN, Lajonchere C, Lutz M, Abbacchi TG, Singh KM, Todd RD. Autistic social impairment in the siblings of children with pervasive developmental disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;163:294–296. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.2.294. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.2.294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Goeke-Morey MC, Papp LM. A family-wide model for the role of emotion in family functioning. Marriage & Family Review. 2003;34(1-2):13–34. [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Goeke-Morey MC, Papp LM. Everyday marital conflict and child aggression. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2004;32:191–202. doi: 10.1023/b:jacp.0000019770.13216.be. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutrona CE, Russell DW, Burzette RG, Wesner KA, Bryant CM. Predicting relationship stability among midlifeAfrican American couples. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2011;79:814–825. doi: 10.1037/a0025874. doi: 10.1037/a0025874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis NO, Carter AS. Parenting stress in mothers and fathers of toddlers with autism spectrum disorders: Associations with child characteristics. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2008;38:1278–1291. doi: 10.1007/s10803-007-0512-z. doi: 10.1007/s10803-0512-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doss BD, Rhoades GK, Stanley SM, Markman HJ. The effect of the transition to parenthood on relationship quality: An 8-year prospective study. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2009;96:601–619. doi: 10.1037/a0013969. doi: 10.1037/a0013969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gau SS-F, Chou M-C, Chiang H-L, Lee J-C, Wong C-C, Wu Y-Y. Parental adjustment, marital relationship, and family function in families of children with autism. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders. 2012;6:263–270. doi 10.1016/j.rasd.2011.05.007. [Google Scholar]

- Ekas NV, Whitman TL. Autism symptom topography and maternal socioemotional functioning. American Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities. 2010;115:234–249. doi: 10.1352/1944-7558-115.3.234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Sheikh M, Keiley M, Erath S, Dyer J. Marital conflict and growth in children's internalizing symptoms: The role of autonomic system activity. Developmental Psychology. 2013;49:92–106. doi: 10.1037/a0027703. doi: 10.1037/a0027703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ennis-Cole D, Durodoye BA, Harris HL. The impact of culture on autism diagnosis and treatment: Considerations for counselors and other professionals. The Family Journal: Counseling and Therapy for Couples and Families. 2013 Published Online doi: 10.1177/1066480713376834. [Google Scholar]

- Floyd FJ, Zmich DE. Marriage and the parenting partnership: Perceptions and interactions of parents with mentally retarded and typically developing children. Child Development. 1991;62:1434–1448. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedman BH, Kalb LG, Zablotsky B, Stuart EA. Relationship status among parents of children with autism spectrum disorders: A population-based study. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2012;42:539–548. doi: 10.1007/s10803-011-1269-y. doi: 10/1007/s10803-011-1269-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartley SL, Barker ET, Baker JK, Seltzer MM, Greenberg JS. Marital satisfaction and life circumstances of grown children with autism across 7 years. Journal of Family Psychology. 2012a;26:688–697. doi: 10.1037/a0029354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartley SL, Barker ET, Seltzer MM, Greenberg JS, Floyd FJ. Marital satisfaction and parenting experiences of mothers and fathers of adolescents and adults with autism. American Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities. 2011;116(1):81–95. doi: 10.1352/1944-7558-116.1.81. doi:10.1352/1944-7558-116.1.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartley SL, Barker ET, Seltzer MM, Floyd FJ, Orsmond GI, Greenberg JS, et al. The relative risk and timing of divorce in families of children with an autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Family Psychology. 2010;24:449–457. doi: 10.1037/a0019847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartley SL, Seltzer MM, Head L, Abbeduto L. Psychological well-being in fathers of adolescents and young adults with Down syndrome, fragile X syndrome, and autism. Family Relations. 2012b;61:327–342. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3729.2011.00693.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartley SL, Sikora DS, McCoy R. Maladaptive behaviors in young children with Autistic Disorder. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 2008;52:819–829. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2008.01065.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurley RS, Losh M, Parlier M, Reznick JS, Piven J. The broad autism phenotype questionnaire. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2007;37:1679–1690. doi: 10.1007/s10803-006-0299-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karney BR, Bradbury TN. The longitudinal course of marital quality and stability: A review of theory, methods, and research. Psychological Bulletin. 1995;118:3–34. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.118.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lecavalier LL, Leone SS, Wiltz JJ. The impact of behaviour problems on caregiver stress in young people with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 2006;50(3):172–183. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2005.00732.x. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2788.2005.00732.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liptak GS, Stuart T, Auinger T. Health care utilization and expenditures for children with autism: Data from U.S. national samples. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2006;36:871–879. doi: 10.1007/s10803-006-0119-9. doi: 10.1007/s10803-006-0119-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lord C, Risi S, Lambrecht L, Cook EH, Leventhal BL, DiLavore P, et al. The Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule-Generic: A standard measure of social and communication deficits associated with the spectrum of autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2000;30:205–223. doi: 10.023/A:1005592401947. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Losh M, Childress D, Lam K, Piven J. Defining key features of the broad autism phenotype: A comparison across parents of multiple-and single-incidence autism families. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part B: Neuropsychiatric Genetics. 2008;147(4):424–433. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neff LA, Karney BR. How does context affect intimate relationships? Linking external stress and cognitive processes within marriage. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2004;30:134–148. doi: 10.1177/0146167203255984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozonoffi S, Young GS, Carter Al., Mesinger D, Yirmiya N, Zwaigenbaum L, et al. Recurrence Risk for Autism Spectrum Disorders: A Baby Siblings Research Consortium Study. Pediatrics. 2011;128:e488–495. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-2825. Doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-2825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petalas MA, Hastings RP, Nash S, Lloyd T, Dowey A. Emotional and behavioural adjustment in siblings of children with intellectual disability with and without autism. Autism. 2009;13(5):471–483. doi: 10.1177/1362361309335721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piven J, Gayle J, Chase GA, Fink B, Landa R, Wzorek MM, et al. A family history study of neuropsychiatric disorders in the adult siblings of autistic individuals. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1990;29:177–183. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199003000-00004. doi: 10.1097/00004583-19903000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS, Cheong AS, Fai YF, Congdon RT, du Toit M. HLM 7: Hierarchical linear and nonlinear modeling. Scientific Software International; Lincolnwood, IL: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M, Le Couteur A, Lord C. Autism diagnostic interview—revised manual. Western Psychological Services; Los Angeles: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Simonoff S, Pickles A, Charman T, Chandler S, Loucas T, Baird G. Psychiatric disorders in children with autism spectrum disorders: Prevalence, comorbidity, and associated factors in a population-derived sample. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2006;47:921–929. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e318179964f. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e318179964f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whisman MA, Uebelacker LA. A longitudinal investigation of marital adjustment as a risk factor for metabolic syndrome. Health Psychology. 2012;31:80–86. doi: 10.1037/a0025671. doi: 10.1037/a0025671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]