Abstract

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) has been associated with eating disorders (EDs) and addictive behaviors, including the relatively new construct food addiction. However, few studies have investigated mechanisms that account for these associations, and men are underrepresented in studies of EDs and food addiction. We examined whether lifetime PTSD symptoms were associated with current food addiction and ED symptoms, and whether emotion regulation (expressive suppression and cognitive reappraisal), which has been associated with both PTSD and EDs, mediated these relations, in a sample of trauma-exposed, male (n = 642) and female (n = 55) veterans. Participants were recruited from the Knowledge Networks-GfK Research Panel and completed an online questionnaire. Structural equation modeling revealed that PTSD was directly associated with ED symptoms, food addiction, expressive suppression, and cognitive reappraisal in the full sample and with all constructs except cognitive reappraisal in the male subsample. Expressive suppression was significantly associated with ED symptoms and mediated the PTSD—ED relation. These results highlight the importance of investigating PTSD as a risk factor for food addiction and ED symptoms and the potential mediating role of emotion regulation in the development of PTSD and EDs in order to identify targets for treatments.

Keywords: eating disorders, men, veterans

1. Introduction

Trauma exposure, in particular childhood sexual abuse, is considered a non-specific risk factor for the development of eating disorders (EDs) because it also precedes the onset of other psychiatric disorders (Jacobi et al., 2004). Research focused on posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) has suggested it may be the pathological response to trauma that is associated with increased risk for EDs, rather than trauma exposure per se (Brewerton, 2007; Mitchell et al., 2012). Further, a previous investigation of a US nationally representative sample found that 40% of women and 66% of men with lifetime bulimia nervosa (BN), and 26% of women and 24% of men with lifetime binge eating disorder (BED), had lifetime histories of PTSD (Mitchell et al., 2012). These findings underscore the need to investigate mechanisms responsible for the association of PTSD and EDs among men as well as women.

It is theorized that disordered eating, particularly bingeing and purging, may be used to cope with negative affect and PTSD symptoms, as these behaviors may serve as a means to blunt or avoid reminders of the trauma (Brewerton, 2007; Heatherton and Baumeister, 1991). Thus, one factor potentially linking PTSD and disordered eating is emotion regulation (Corstorphine et al., 2007; Svaldi et al., 2012, 2010). Emotion regulation is a multifaceted construct that generally refers to intrinsic and extrinsic processes by which individuals monitor, evaluate, and modify their emotional reactions (Gross, 2014). Difficulties with emotion regulation have been associated with PTSD (Ehlers and Clark, 2000; Kashdan et al., 2010; Litz and Gray, 2002), and Staiger and colleagues found that emotion regulation mediated the relation between PTSD and substance use (Staiger et al., 2009).

Emotion regulation deficits have been theoretically and empirically associated with disordered eating as well. For example, women with EDs may be more likely to engage in emotional avoidance than women without EDs. Svaldi et al. (2012) compared two forms of emotion regulation: cognitive reappraisal, an adaptive strategy defined as cognitively transforming a situation in order to modify its impact on one’s emotions (Gross and John, 2003), and expressive suppression, a maladaptive strategy defined as inhibiting emotion-expressive behavior (Gross and Levenson, 1993). They found that expressive suppression, but not cognitive reappraisal, predicted desire to binge among women with BED, suggesting that emotion regulation mediated the association between negative mood and binge eating. These results are consistent with a meta-analysis of emotion regulation and EDs that found stronger associations between expressive suppression and EDs than between cognitive appraisal and EDs (Aldao et al., 2010).

The theory that disordered eating is a maladaptive method of coping with PTSD symptoms is similar to the proposed association between PTSD and substance use disorders. Thus, food addiction is a construct that is relevant to investigations of PTSD, EDs, and emotion regulation, and potential links between PTSD and food addiction have recently gained the attention of investigators. Proposed criteria for food addiction were developed to parallel criteria for substance use disorders and include tolerance; withdrawal; consuming larger amounts or over a longer period than intended; persistent desire or unsuccessful efforts to reduce consumption; much time spent obtaining, using, or recovering from the effects of consumption; giving up or reducing important activities because of consumption; and clinically significant impairment or distress (Gearhardt et al., 2009a). Food addiction as currently conceptualized is similar to, but distinct from, BED, in that they share symptoms of consuming larger amounts or over a longer period than intended (i.e., binge eating) and loss of control (Corwin and Grigson, 2009). It is important to note that food addiction is a somewhat controversial topic. Although evidence for its construct validity is promising, with studies showing that consumption of high fat-high sugar foods activate neural pathways that are also salient to substances of abuse (Gearhardt et al., 2011), other investigators have questioned the use of the term “food addiction,” given the lack of research on addictive properties of specific nutrients/substances in food (Hebebrand et al., 2014). Nonetheless, extant evidence suggests that some individuals demonstrate behavioral addiction symptoms in relation to highly palatable foods (Corsica and Pelchat, 2010).

Given that PTSD has been associated with increased rates of substance use disorders (Jacobsen et al., 2001), it is quite plausible that food addiction also would be associated with PTSD. Only one study to date has investigated this hypothesis: Mason and colleagues found that women with more PTSD symptoms were more than twice as likely to meet criteria for food addiction than were women without trauma or PTSD (Mason et al., 2014). However, this association has not been examined among men. Interestingly, although rates of alcohol and substance use disorders are higher among men than women (Goldstein et al., 2012), preliminary evidence suggests that food addiction is more prevalent among women. For example, Pedram and colleagues (Pedram et al., 2013) found that 6.7% of women and 3% of men in a community sample met proposed criteria for food addiction. As with EDs in general, however, relatively few studies of food addiction have included male samples (Pursey et al., 2014).

We investigated associations among PTSD, emotion regulation, ED symptoms, and food addiction in a population-based sample of veterans. Veterans evidence disproportionately high rates of PTSD (Kulka et al., 1990; Tanielian, 2008). However, they remain understudied in the field of EDs, possibly due to the misperception that members of this traditionally male population are not affected by EDs. Although there have been no studies of EDs in nationally representative samples of veterans, extant studies among military samples suggest that the unique pressures of military life, including high rates of trauma exposure and strict weight and physical fitness requirements, may increase risk for the development of ED symptoms among male and female service members (Jacobson et al., 2009). Findings from clinical and community samples of veterans suggest that rates of EDs are comparable to, and possibly higher than, rates of EDs among women and men in the general population, underscoring the need for further investigation of ED-related constructs among veterans (Curry et al., 2014; Forman-Hoffman et al., 2012; Litwack et al., 2014). This study had several aims: 1) to report rates of PTSD, EDs, and food addiction; 2) to assess direct associations between PTSD and food addiction and ED symptoms, with a focus on the male subsample, as men remain understudied in these areas and comprise the majority of our sample; and 3) to examine the mediating role of emotion regulation in linking PTSD to ED symptoms and food addiction symptoms.

2. Method

2.1 Participants

In 2013, participants were recruited from a larger study of 3,156 veterans who participated in a GfK Knowledge Networks, Inc. study in 2011 (Pietrzak and Cook, 2013). Of the larger sample, 1126 veterans were randomly selected from the subsample of participants who had reported trauma exposure in the 2011 study and who remained on the research panel (n = 2365). The 1126 veterans were invited to participate in a survey of PTSD, dissociation, and disordered eating. We received a total of 860 responses, including 787 men and 73 women. The response rate was 85.9%, including 86.5% of men and 80.1% of women.

Participants were excluded from analyses if their responses to the survey were deemed invalid, based on their completion time (n = 142) or scores on the revised Infrequency Psychopathology (Fp-r) validity scale on the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory-2 Restructured Form (n = 23) (Tellegen and Ben-Porath, 2008). Two participants were excluded because they achieved an Fp-r T-score > 90 and took over 2 hours to complete the survey, resulting in a final sample of 697, including 642 men and 55 women.

2.2 Procedure

The GfK Research Panel is a government and academic research firm that maintains a probability-based research panel including over 80,000 households. Participants were recruited through probability, address-based sampling methods that cover approximately 98% of the US population. Computer hardware and internet access were provided as needed. Participating on the panel implies consent to be contacted about research studies; participants may be selected on the basis of a variety of variables. GfK participants were recruited to web-based studies via e-mail and provided with incentives for study completion in the form of points that could be redeemed for cash or prizes. Post-stratification weights were computed based on demographic characteristics (age, gender, race/ethnicity, education, census region, and metropolitan area) of US veterans in the GfK Knowledge Networks survey panel. A previous study found that the demographic characteristics of this cohort closely match those of the veterans in the 2013 US Census (Wisco et al., under review). In addition, the sample weight for the current study accounts for selection based on trauma exposure.

Data were drawn from a larger survey focused on an array of psychopathological experiences. The entire survey took an average of 36.5 minutes (SD = 17.7) minutes, and participants were awarded 50,000 points, or approximately $50. The local human subjects protection review board approved all study procedures and waived the need for informed consent due to the anonymous nature of the data.

2.3 Measures

Eating Disorder Diagnostic Scale (EDDS)

The EDDS is a 22-item self-report survey of anorexia nervosa (AN), BN, and BED symptomatology (Stice et al., 2000). This measure can be used to make probable DSM-IV diagnoses and also yields a composite symptom score. The EDDS was developed based on Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-IV (DSM-IV; American Psychiatric Association, 2000) criteria for EDs; however, we modified the diagnostic algorithms slightly to create DSM-5 diagnoses (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Specifically, we excluded the amenorrhea item from the AN diagnosis, as per the DSM-5; this item does not apply to men. We also excluded the item assessing amenorrhea from the composite score. Items assessing height and weight were used to calculate body mass index (BMI). The DSM-5 does not specify a threshold for low weight in AN. We therefore assessed AN based on a BMI of < 17.5 and also based on a BMI < 18.5, to reflect the World Health Organization categorization of underweight (World Health Organization, 2006). For BN, we used the binge and compensatory behavior frequency and duration criteria of once per week for 3 months from the DSM-5. These same criteria for frequency and duration of binges were applied to BED.

The developers of the EDDS reported that this measure yields stable and internally consistent scores and demonstrated convergent validity. Agreement between EDDS diagnoses and interview diagnoses was excellent in the original validation sample and ranged from 93% to 99%; mean kappa across EDs was .83 (Stice et al., 2000). Cronbach’s alpha in the development sample was .89 (Stice et al., 2000). In the current study, Cronbach’s alpha for the EDDS composite score was .86. EDDS items were assigned to parcels based on exploratory factor analysis, which revealed three underlying factors. However, the four items assessing compensatory behaviors cross-loaded onto two factors each. Therefore, self-induced vomiting and laxative/diuretic use were assigned to the first factor, along with items assessing fear of fat and the influence of weight and shape on one’s self-concept. Fasting and excessive exercise were assigned to the first factor, along with binge eating and binge characteristics. We created parcels based on these two factors, which served as indicators of the latent ED symptomatology construct. Cronbach’s alphas for the parcels were .83 and .78.

Yale Food Addiction Scale (YFAS)

The YFAS is a 25-item measure that assesses food addiction symptoms, based on DSM-IV criteria for substance use disorder and proposed behavioral addiction criteria (Gearhardt et al., 2009b). The YFAS questions are based on the past 12 months; this measure yields a “diagnostic” score as well as a continuous symptom count. The measure’s developers reported acceptable convergent (with the Eating Attitudes Test-26 and the Emotional Eating Scale) and discriminant validity (with the Behavioral Activation System scale, the Rutgers Alcohol Problem Index, and the Daily Drinking Questionnaire) as well as internal consistency (Kuder-Richardson alpha = .86). In the current study, the Kuder-Richardson alpha for the YFAS was .74. YFAS scores were used as a single indicator of the latent food addiction construct, as described below.

Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (ERQ)

The ERQ is a 10-item measure of cognitive reappraisal and expressive suppression. Higher subscale scores indicate greater reappraisal (less pathology) and greater suppression (more pathology), respectively. The ERQ demonstrated good convergent and discriminant validity and internal consistency in validation samples (Gross and John, 2003). In the development study, Cronbach’s alpha ranged from .75 to .82 for the cognitive reappraisal subscale (ERQ-R) and .68 to .76 for the expressive suppression subscale (ERQ-S) (Gross and John, 2003). In this study, Cronbach’s alphas were .87 for reappraisal and .76 for suppression. ERQ-S items were used as indicators of the latent construct expressive suppression, and ERQ-R items were used as indicators of the latent construct cognitive reappraisal in the models.

National Stressful Events Survey (NSES)

The NSES (Kilpatrick et al., 2011) was used to assess trauma exposure and lifetime and current DSM-5 PTSD symptoms. This measure yields probable diagnoses as well as continuous severity scores. Although relatively new, the NSES has been used in several studies of US veterans and civilian adults (e.g., Kilpatrick et al., 2013; Miller et al., 2013). Further, the NSES severity score has demonstrated convergent validity with an established self-report measure of DSM-IV PTSD (Miller et al., 2013). In the current study, Cronbach’s alpha for the lifetime PTSD subscale was .90. Subscales of items corresponding to DSM-5 symptom clusters (re-experiencing, avoidance, negative alterations in cognition/mood, and hyperarousal) were used as indicators of the latent construct PTSD.

Demographics

Covariates included age, gender, BMI, and race/ethnicity.

2.4 Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics, both weighted and unweighted, were calculated in SAS 9.4. As all of our participants were trauma-exposed, weighted results allow us to make inferences about the general population of male US veterans. In comparison, unweighted results are interpreted in the context of our trauma-exposed sample. We estimated structural equation models (SEMs) in Mplus 7.0 (Muthén and Muthén, 1998) to assess the impact of PTSD symptoms, cognitive reappraisal, and expressive suppression on ED symptoms and food addiction symptoms. We used full information maximum likelihood estimation to use all available data, rather than deleting cases listwise. Models were not weighted. The weights generalize to US veterans but not to trauma-exposed veterans, so we used them for prevalence estimates but not for analyses focusing on associations with PTSD, as PTSD only applies to trauma exposed individuals. As recommended, a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) model was first fit to the data (Anderson and Gerbing, 1988). After establishing goodness-of-fit, structural paths were added to the model. The comparative fit index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), standardized root mean square residual (SRMR), and root mean squared error of approximation (RMSEA) were used to examine model fit (Hu and Bentler, 1999).

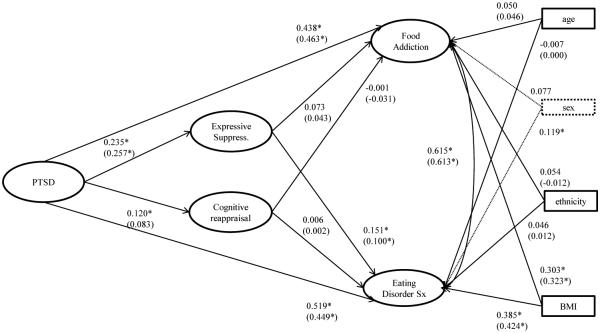

We used 5,000 95% bootstrap confidence intervals in order to test the significance of indirect effects, from PTSD to ED symptoms and food addiction symptoms, via cognitive reappraisal and expressive suppression (see Figure 1). All models were estimated in the full sample (controlling for sex) and in the male subsample separately, as the female subsample was too small for SEM. In addition to testing the significance of the indirect effect, the chi-square difference test was used to compare Models 1 (without direct paths from PTSD to ED symptoms and food addiction, respectively) and 2 (with direct paths from PTSD to ED symptoms and food addiction), in order to determine whether the direct paths contributed significantly to the fit of the model.

Figure 1.

The final model with direct paths from PTSD to food addiction and eating disorder symptoms

Note: PTSD=posttraumatic stress disorder. Expressive Suppress=expressive suppression. Eating Disorder Sx=eating disorder symptoms. All coefficients are standardized. Coefficients for the male subsample are presented in parentheses.

3. Results

3.1 Descriptives

Participants ranged in age from 22 to 96 (M = 62.99, SD = 12.03). The majority was Caucasian (84.6%), married (76.8%), and had at least some college education (87.0%). We evaluated several possible covariates of our main variables of interest, including age, BMI, race/ethnicity, marital status, and education. Age was negatively correlated with EDDS (r = −0.242) and YFAS scores (r = −0.148); BMI was positively correlated with EDDS (r = 0.380) and YFAS scores (r = 0.284). Hispanic ethnicity was associated with significantly higher mean EDDS (t = −2.520, df = 34.808, p = .016) and YFAS scores (t = −2.098, df = 35.833, p = .043) as well. Therefore, these covariates were included in the models. We also controlled for sex in models estimated in the full sample.

See Table 1 for means and SDs, as well as published norms, when available, for all study measures. Only one male participant (0.2%, 0.1 weighted %), and no female participants, met DSM-5 criteria for AN based on a BMI < 18.5. A total of 23 participants (3.3%; 2.8 weighted %), including 18 men (2.8%; 2.4 weighted %) and 5 women (9.1%; 6.6 weighted %), met criteria for BN; 20 participants (2.9%; 2.5 weighted %), including 16 men (2.5%, 2.2 weighted %) and 4 women (7.3%, 5.7 weighted %), met criteria for BED. A total of 16 participants (2.3%; 1.5 weighted %), including 12 men (1.9%; 1.2 weighted %) and 4 women (7.3%; 3.9 weighted %), met the proposed criteria for food addiction.

Table 1.

Means, standard deviations, and norms for study measures

| Normative Sample | Full Sample | Male Subsample | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Measure | Mean | SD | Range | Mean | SD | Range | Mean | SD |

| NSESa | -- | -- | 0.0-21.0 | 4.555 | 5.144 | 0.0-21.0 | 4.226 | 4.903 |

| ERQ-Sb | 3.64 | 1.11 | 4.0-28.0 | 15.465 | 4.335 | 4.0-28.0 | 15.510 | 4.283 |

| ERQ-Rb | 4.60 | 0.94 | 6.0-42.0 | 27.547 | 6.004 | 6.0-42.0 | 27.368 | 5.954 |

| EDDSc | 0.00 | 11.32 | −0.53-3.05 | 0.002 | 0.594 | −0.51-2.33 | 0.003 | 0.583 |

| YFASc | 1.7 | 0.4 | 0.0-7.0 | 1.332 | 1.184 | 0.0-7.0 | 1.281 | 1.140 |

Note: NSES=National Stressful Events Survey, ERQ-S=Emotion Regulation Questionnaire-expressive suppression subscale, ERQ-R= Emotion Regulation Questionnaire-cognitive reappraisal subscale, EDDS = Eating Disorder Diagnostic Scale, YFAS = Yale Food Addiction Scale, SD=standard deviation

The mean and standard deviation for the lifetime PTSD symptom severity score are not presented in the initial studies of the NSES (Kilpatrick et al., 2011). However, as expected, our prevalence estimate of lifetime PTSD (13.1%) fell between previous estimates in US civilian adults (8.3%; (Kilpatrick et al., 2013) and trauma-exposed Veterans Affairs patients (67.5%; (Miller et al., 2013).

ERQ-S and ERQ-R norms are reported for the male subsample only, as overall means and SDs are not presented in the development article (Gross and John, 2003).

The mean and standard deviation from the EDDS was based on an average of the summed standardized EDDS items. The measure’s developers reported in a later study that it was not necessary to standardize the items. We standardized the EDDS items in this table only for comparison to the development sample.

dMeans and SDs were not reported for the development sample of the YFAS. We report the mean and SD from a recent meta-analysis; these are meta-analyzed values from non-clinical samples (Pursey et al., 2014).

The traumatic experiences most commonly endorsed as participants’ worst traumas were sudden unexpected death of a loved one (17.5%), combat or its aftermath (13.6%), violent death of a loved one (7.3%), witnessed dead bodies or parts of bodies (6.3%), physical or sexual assault (5.5%), other stressful event in which the participant feared being killed/injured (7.9%), and some other extraordinarily stressful event (16.9%). In the full sample, 91 participants (13.1%; 15.2 weighted %) met criteria for lifetime PTSD, including 71 men (11.1%; 12.7 weighted %) and 20 women (36.4%; 40.6 weighted %).

3.2 Measurement model (CFA) results

We first fit the CFA model for all study measures. The initial model estimation produced an error regarding the YFAS indicators, and we discovered that the high correlations between the indicators prevented the model from converging. As the measure’s developers previously demonstrated that this measure is unidimensional, we used YFAS total scores as a single indicator of the latent construct food addiction. Accordingly, we set the factor loading equal to 1, and we set the error variance of this indicator equal to the variance of the scale*(1-the reliability) (Brown, 2006). All factor loadings were significant (see Table 2 for factor loadings, means, and standard deviations for all items). The CFA model fit the data well in the full sample and in the male subsample (see Table 3 for all model fit statistics).

Table 2.

Item factor loadings, means, and standard deviations

| Full Sample | Male Subsample | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Measure | FL | Mean | SD | FL | Mean | SD |

| NSES-B | 0.805 | 5.752 | 2.446 | 0.805 | 5.683 | 2.350 |

| NSES-C | 0.789 | 3.358 | 1.317 | 0.767 | 3.300 | 1.209 |

| NSES-D | 0.799 | 7.697 | 2.716 | 0.780 | 7.626 | 2.525 |

| NSES-E | 0.810 | 6.717 | 2.285 | 0.810 | 6.654 | 2.200 |

| ERQ1 | 0.754 | 4.523 | 1.406 | 0.748 | 4.476 | 1.399 |

| ERQ2 | 0.595 | 4.676 | 1.449 | 0.592 | 4.695 | 1.426 |

| ERQ3 | 0.754 | 4.599 | 1.346 | 0.747 | 4.550 | 1.342 |

| ERQ4 | 0.525 | 3.023 | 1.391 | 0.524 | 3.036 | 1.376 |

| ERQ5 | 0.451 | 4.741 | 1.329 | 0.457 | 4.741 | 1.328 |

| ERQ6 | 0.870 | 3.836 | 1.476 | 0.874 | 3.849 | 1.465 |

| ERQ7 | 0.879 | 4.623 | 1.183 | 0.872 | 4.598 | 1.179 |

| ERQ8 | 0.820 | 4.536 | 1.192 | 0.814 | 4.509 | 1.188 |

| ERQ9 | 0.663 | 3.932 | 1.372 | 0.660 | 3.933 | 1.357 |

| ERQ10 | 0.770 | 4.519 | 1.206 | 0.764 | 4.488 | 1.199 |

| EDDS1 | 0.741 | 7.993 | 7.062 | 0.743 | 7.423 | 6.728 |

| EDDS2 | 0.837 | 3.464 | 5.126 | 0.835 | 3.231 | 4.898 |

| YFAS | 0.845 | 1.332 | 1.184 | 0.845 | 1.281 | 1.140 |

Note: NSES-B=National Stressful Events Survey, re-experiencing symptom cluster; NSES-C= National Stressful Events Survey, avoidance symptom cluster; NSES-D= National Stressful Events Survey, negative alterations in cognition/mood symptom cluster; NSES-E=National Stressful Events Survey, hyperarousal symptom cluster; ERQ1=Emotion Regulation Questionnaire item 1 (“When I want to feel more positive emotion…I change what I’m thinking about”); ERQ2=Emotion Regulation Questionnaire item 2 (“I keep my emotions to myself”); ERQ3=Emotion Regulation Questionnaire item 3 (“When I want to feel less negative emotion…I change what I’m thinking about”); ERQ4=Emotion Regulation Questionnaire item 4 (“When I am feeling positive emotions, I am careful not to express them”); ERQ5=Emotion Regulation Questionnaire item 5 (“When I’m faced with a stressful situation, I make myself think about it in a way that helps me stay calm”); ERQ6=Emotion Regulation Questionnaire item 6 (“I control my emotions by not expressing them”); ERQ7=Emotion Regulation Questionnaire item 7 (“When I want to feel more positive emotion, I change the way I’m thinking about the situation”); ERQ8=Emotion Regulation Questionnaire item 8 (“I control my emotions by changing the way I think about the situation I’m in”); ERQ9=Emotion Regulation Questionnaire item 9 (“When I am feeling negative emotions, I make sure not to express them”); ERQ10=Emotion Regulation Questionnaire item 10 (“When I want to feel less negative emotion, I change the way I’m thinking about the situation”); EDDS1 = Eating Disorder Diagnostic Scale, parcel 1; EDDS2 = Eating Disorder Diagnostic Scale, parcel 2; YFAS = Yale Food Addiction Scale scores; FL=factor loading; SD=standard deviation.

Table 3.

Fit statistics for all models

| Model | χ 2 | df | CFI | TLI | SRMR | RMSEA | Δ χ 2 | Δdf | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||||||

| CFA (full sample) | 332.235 | 111 | 0.958 | 0.949 | 0.039 | 0.053 | -- | -- | -- |

| CFA (male subsample) | 323.789 | 111 | 0.955 | 0.945 | 0.041 | 0.055 | -- | -- | -- |

| Model 1 (full sample) | 738.025 | 175 | .899 | .883 | 0.090 | 0.068 | -- | -- | -- |

| Model 2 (full sample) | 585.250 | 173 | 0.926 | 0.913 | 0.064 | 0.058 | 152.775 | 2 | <0.001 |

| Model 1 (male subsample) | 588.304 | 158 | 0.913 | 0.897 | 0.085 | 0.065 | -- | -- | -- |

| Model 2 (male subsample) | 431.361 | 156 | 0.944 | 0.933 | 0.057 | 0.052 | 156.943 | 2 | <0.001 |

Note: CFA = confirmatory factor analysis, χ2 = chi-square, df = degrees of freedom, CFI = comparative fit index, TLI = Tucker-Lewis index, SRMR = standardized root mean square residual, RMSEA = root mean squared error of approximation, Δχ2 = change in chi-square, Δdf = change in degrees of freedom. Model 1 did not include direct paths from posttraumatic stress disorder to eating disorder symptoms and food addiction symptoms, respectively. Model 2 included direct paths from posttraumatic stress disorder to eating disorder symptoms and food addiction symptoms, respectively.

3.3 SEM results

We estimated Model 1 without direct paths from PTSD to ED and food addiction symptoms. The majority of the structural paths were significant in the full sample and in the male subsample, with the exception of the paths from cognitive reappraisal to both ED symptoms and food addiction, and the path from PTSD to cognitive reappraisal fell just above the threshold for significance in the male subsample (p = 0.056). However, this model produced somewhat sub-optimal fit, as shown in Table 3. We then estimated Model 2, which included the two direct paths (see Figure 1). With these paths included, the path from expressive suppression to food addiction became non-significant in the full sample as well as the male subsample. Of the covariates, only BMI was significantly associated with both ED symptoms and food addiction; sex also was significantly associated with ED symptoms in the full sample. Model 2 fit the data well. The chi-square difference test comparing Models 1 and 2 was significant, indicating that dropping the direct paths significantly worsened the fit of the model.

We also tested for evidence of mediation for the path between PTSD and ED symptoms, via expressive suppression, using the “model indirect” command, which tests the significance of the indirect effects. The indirect path from PTSD to expressive suppression to ED symptoms was significant in the full sample (b = 0.192, SE = 0.063, p = 0.002, 95% CI: 0.069, 0.314) and in the male subsample (b = 0.134, SE = 0.061, p = 0.029, 95% CI: 0.014, 0.255). In sum, PTSD was associated with cognitive reappraisal and expressive suppression, and expressive suppression was, in turn, associated with ED symptoms. PTSD was directly associated with food addiction and ED symptoms; PTSD also was indirectly associated with ED symptoms, via expressive suppression, in the full sample and in the male subsample.

4. Discussion

Previous studies have found that individuals with EDs have high rates of PTSD, and although the majority of these studies have focused on female samples, this association appears to hold true for men as well (Mitchell et al., 2012). We found that PTSD was significantly associated with ED symptoms as well as food addiction symptoms in this primarily male sample of older veterans. It is noteworthy that rates of food addiction and probable ED diagnoses in this sample were consistent with estimates from population-based samples (Hudson et al., 2007; Pedram et al., 2013). To date, only one previous study has examined the association between PTSD and food addiction (Mason et al., 2014) and was focused on women only; our results support this finding in a sample of men as well. As with EDs, rates of food addiction appear higher among women than men (Pedram et al., 2013; Pursey et al., 2014). However, PTSD may confer risk for food addiction among men as well as women, although these results require replication and extension in longitudinal samples. As PTSD has been associated with a higher BMI and risk for obesity in veterans (Vieweg et al., 2007) and women in the general population (Kubzansky et al., 2014; Mitchell et al., 2013), food addiction symptoms, as well as ED symptoms, may be an important target for intervention among individuals with PTSD. Further, previous studies of PTSD and trauma among individuals with EDs have focused largely on childhood sexual abuse, although more recent research has investigated adult-onset traumas, particularly those of an interpersonal nature (Brewerton, 2007). In our sample, the exposures most commonly described as participants’ worst traumas were sudden unexpected death of a loved one and combat or its aftermath, suggesting that PTSD resulting from a wide range of traumas may be associated with food addiction and ED symptoms.

Few studies have investigated mechanisms that account for the association between PTSD and disordered eating. Consistent with previous findings (Svaldi et al., 2010), our results suggested that expressive suppression, a maladaptive coping mechanism, but not cognitive reappraisal, an adaptive coping mechanism, was associated with ED symptoms. Interestingly, cognitive reappraisal was positively (if weakly) associated with PTSD in the full sample, suggesting that participants were engaging in positive coping strategies. As hypothesized, expressive suppression mediated the association between PTSD and ED symptoms, in the full sample and in the male subsample. Thus, a potential pathway from PTSD to EDs is through maladaptive suppression of emotion. Expressive suppression reflects attempts to reduce outward expression of emotion and may be adaptive in the short-term; however, this strategy becomes less effective over the long term. This finding aligns with previous theoretical and empirical work suggesting that in some individuals, ED symptoms may be used to cope with negative affect.

Contrary to our expectations, we found that neither cognitive reappraisal nor expressive suppression was significantly associated with food addiction scores in our final model. Emotion dysregulation, which has been associated with both PTSD and disordered eating (Corstorphine et al., 2007; Ehlers and Clark, 2000; Kashdan et al., 2010; Litz and Gray, 2002), is a multi-faceted trait (Gratz and Roemer, 2004); future research should explore whether additional emotion regulation constructs, such as acceptance of emotions, emotional avoidance, and impulsivity mediate the PTSD—food addiction/disordered eating association. For example, previous studies have found that individuals displaying greater impulsivity were more likely to use bingeing and purging to regulate negative affect (Fernandez-Aranda et al., 2008).

Findings should be interpreted in light of several limitations. Although our test of expressive suppression as a mediator was significant in the full sample, it is worth noting that the direct effects of PTSD on food addiction and ED symptoms were much stronger than the indirect effects via emotion regulation. Thus, our findings highlight the substantial direct impact of PTSD on disordered eating and also suggest that other variables not evaluated here may be mechanisms of this association. Further, longitudinal studies are needed to confirm the temporality of this model and if other aspects of emotion regulation may be more relevant to PTSD and disordered eating. Investigations of sex similarities and differences also are warranted. In addition, probable diagnoses were based on survey responses and not confirmed by an interview, a common limitation of population-based studies. It is important to note that validity of DSM-5 diagnoses using the EDDS and NSES has not yet been established. Finally, although our response rate of 76.4% was excellent, it is possible that response bias could have impacted our results. Strengths of the current study include the large sample of veterans and wide range of trauma exposures. Although this population remains understudied in EDs and food addiction, it is noteworthy that our sample’s mean scores on the EDDS and YFAS were consistent with previously published norms, as shown in Table 1. Our findings underscore the importance of examining EDs and food addiction in traditionally underserved populations, in this case, older veterans.

In addition to exploring sex similarities and differences in the associations between PTSD, emotion regulation, EDs, and food addiction, future research should further explore mechanisms accounting for these relations in order to identify targets for treatment. Further, PTSD has been most strongly associated with EDs characterized by bingeing and/or purging. Associations among PTSD, emotion regulation, and specific ED symptoms may be a promising area of investigation.

Highlights.

PTSD was associated with eating disorder symptoms and food addiction.

Expressive suppression was associated with eating disorder symptoms.

Expressive suppression mediated the PTSD—eating disorder sympotms association.

Acknowledgement

Karen Mitchell’s contribution was partly supported by K01 MH093750. This work was also supported by a Career Development Award to Erika J. Wolf from the United States (U.S.) Department of Veterans Affairs, Clinical Sciences Research and Development Program. The funding sources had no role in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the article for publication. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Aldao A, Nolen-Hoeksema S, Schweizer S. Emotion-regulation strategies across psychopathology: A meta-analytic review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2010;30:217–237. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.11.004. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2009.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th Author; Washington, DC: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. Revised 4th Author; Washington, D.C.: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson J, Gerbing D. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988;103:411–423. [Google Scholar]

- Brewerton TD. Eating disorders, trauma, and comorbidity: Focus on PTSD. Eat. Disord. J. Treat. Prev. 2007;15:285–304. doi: 10.1080/10640260701454311. doi:10.1080/10640260701454311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TA. Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research. Guilford Press; New York: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Corsica JA, Pelchat ML. Food addiction: True or false? Curr. Opin. Gastroenterol. 2010;26:165–169. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0b013e328336528d. doi:10.1097/MOG.0b013e328336528d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corstorphine E, Mountford V, Tomlinson S, Waller G, Meyer C. Distress tolerance in the eating disorders. Eat. Behav. 2007;8:91–97. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2006.02.003. doi:10.1016/j.eatbeh.2006.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corwin RL, Grigson PS. Symposium Overview—Food Addiction: Fact or Fiction? J. Nutr. 2009;139:617–619. doi: 10.3945/jn.108.097691. doi:10.3945/jn.108.097691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curry JF, Aubuchon-Endsley N, Brancu M, Runnals JJ, VA Mid-Atlantic Mirecc Women Veterans Research Workgroup, VA Mid-Atlantic Mirecc Registry Workgroup. Fairbank JA. Lifetime major depression and comorbid disorders among current-era women veterans. J. Affect. Disord. 2014;152-154:434–440. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.10.012. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2013.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehlers A, Clark DM. A cognitive model of posttraumatic stress disorder. Behav. Res. Ther. 2000;38:319–45. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(99)00123-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Aranda F, Pinheiro AP, Thornton LM, Berrettini WH, Crow S, Fichter MM, Halmi KA, Kaplan AS, Keel P, Mitchell J, Rotondo A, Strober M, Woodside DB, Kaye WH, Bulik CM. Impulse control disorders in women with eating disorders. Psychiatry Res. 2008;157:147–157. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2007.02.011. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2007.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forman-Hoffman VL, Mengeling M, Booth BM, Torner J, Sadler AG. Eating disorders, post-traumatic stress, and sexual trauma in women veterans. Mil. Med. 2012;177:1161–1168. doi: 10.7205/milmed-d-12-00041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gearhardt AN, Corbin WR, Brownell KD. Food addiction: An examination of the diagnostic criteria for dependence. J. Addict. Med. 2009a;3:1–7. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0b013e318193c993. doi:10.1097/ADM.0b013e318193c993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gearhardt AN, Corbin WR, Brownell KD. Preliminary validation of the Yale Food Addiction Scale. Appetite. 2009b;52:430–436. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2008.12.003. doi:10.1016/j.appet.2008.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gearhardt AN, Yokum S, Orr PT, Stice E, Corbin WR, Brownell KD. The neural correlates of “food addiction.” Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2011;68:808–816. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.32. doi:10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein RB, Dawson DA, Chou SP, Grant BF. Sex differences in prevalence and comorbidity of alcohol and drug use disorders: Results from wave 2 of the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs. 2012;73:938–950. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2012.73.938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratz K, Roemer L. Multidimensional Assessment of Emotion Regulation and Dysregulation: Development, Factor Structure, and Initial Validation of the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 2004;26:41–54. [Google Scholar]

- Gross JJ. Handbook of Emotion Regulation. Second Guilford Press; New York, NY: 2014. Emotion regulation: Conceptual and empirical foundations; pp. 3–20. [Google Scholar]

- Gross JJ, John OP. Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: Implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2003;85:348–362. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.85.2.348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross JJ, Levenson RW. Emotional suppression: Physiology, self-report, and expressive behavior. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1993;64:970–986. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.64.6.970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heatherton TF, Baumeister RF. Binge eating as escape from self-awareness. Psychol. Bull. 1991;110:86–108. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.110.1.86. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.110.1.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebebrand J, Albayrak Ö, Adan R, Antel J, Dieguez C, de Jong J, Leng G, Menzies J, Mercer JG, Murphy M, van der Plasse G, Dickson SL. “Eating addiction”, rather than “food addiction”, better captures addictive-like eating behavior. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2014;47:295–306. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2014.08.016. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2014.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson JI, Hiripi E, Pope HG, Jr, Kessler RC. The prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Biol. Psychiatry. 2007;61:348–358. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.03.040. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.03.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 1999;6:1–55. doi:10.1080/10705519909540118. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobi C, Hayward C, de Zwaan M, Kraemer HC, Agras WS. Coming to terms with risk factors for eating disorders: application of risk terminology and suggestions for a general taxonomy. Psychol. Bull. 2004;130:19–65. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.130.1.19. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.130.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen LK, Southwick SM, Kosten TR. Substance use disorders in patients with posttraumatic stress disorder: A review of the literature. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2001;158:1184–1190. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.8.1184. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.158.8.1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson IG, Smith TC, Smith B, Keel PK, Amoroso PJ, Wells TS, Bathalon GP, Boyko EJ, Ryan MAK. Disordered eating and weight changes after deployment: Longitudinal assessment of a large US military cohort. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2009;169:415–427. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn366. doi:10.1093/aje/kwn366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashdan TB, Breen WE, Julian T. Everyday strivings in war veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder: Suffering from a hyper-focus on avoidance and emotion regulation. Behav. Ther. 2010;41:350–63. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2009.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick DG, Fesnick HS, Baber B, Guille C, Gros K. The National Stressful Events Web Survey (NSES-W) Charlest. SC Med. Univ. S. C.; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick DG, Resnick HS, Milanak ME, Miller MW, Keyes KM, Friedman MJ. National estimates of exposure to traumatic events and PTSD prevalence using DSM-IV and DSM-5 criteria. J. Trauma. Stress. 2013;26:537–547. doi: 10.1002/jts.21848. doi:10.1002/jts.21848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubzansky LD, Bordelois P, Jun HJ, Roberts AL, Cerda M, Bluestone N, Koenen KC. The weight of traumatic stress: A prospective study of posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms and weight status in women. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71:44–51. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.2798. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.2798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulka RA, Schlenger WE, Fairbank JA, Hough RL, Jordan BK, Marmar CR, Weiss DS. Trauma and the Vietnam war generation: Report of findings from the National Vietnam Veterans Readjustment Study, Trauma and the Vietnam war generation: Report of findings from the National Vietnam Veterans Readjustment Study. Brunner/Mazel; Philadelphia, PA: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Litwack SD, Mitchell KS, Sloan DM, Reardon AF, Miller MW. Eating disorder symptoms and comorbid psychopathology among male and female veterans. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry. 2014;36:406–410. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2014.03.013. doi:10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2014.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litz BT, Gray MJ. Emotional numbing in posttraumatic stress disorder: Current and future research directions. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry. 2002;36:198–204. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1614.2002.01002.x. doi:10.1046/j.1440-1614.2002.01002.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason SM, Flint AJ, Roberts AL, Agnew-Blais J, Koenen KC, Rich-Edwards JW. Posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms and food addiction in women by timing and type of trauma exposure. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71:1271–1278. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.1208. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.1208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MW, Wolf EJ, Kilpatrick D, Resnick H, Marx BP, Holowka DW, Keane TM, Rosen RC, Friedman MJ. The prevalence and latent structure of proposed DSM-5 posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in U.S. national and veteran samples. Psychol. Trauma Theory Res. Pract. Policy. 2013;5:501–512. doi:10.1037/a0029730. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell KS, Aiello AE, Galea S, Uddin M, Wildman D, Koenen KC. PTSD and obesity in the Detroit neighborhood health study. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry. 2013;35:671–673. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2013.07.015. doi:10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2013.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell KS, Mazzeo SE, Schlesinger MR, Brewerton TD, Smith BN. Comorbidity of partial and subthreshold ptsd among men and women with eating disorders in the national comorbidity survey-replication study. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2012;45:307–315. doi: 10.1002/eat.20965. doi:10.1002/eat.20965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User’s Guide. Seventh Muthén & Muthén; Los Angeles, CA: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Pedram P, Wadden D, Amini P, Gulliver W, Randell E, Cahill F, Vasdev S, Goodridge A, Carter JC, Zhai G, Ji Y, Sun G. Food addiction: Its prevalence and significant association with obesity in the general population. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e74832. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0074832. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0074832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pietrzak RH, Cook JM. Psychological resilience in older U.S. veterans: Results from the national health and resilience in veterans study. Depress. Anxiety. 2013;30:432–443. doi: 10.1002/da.22083. doi:10.1002/da.22083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pursey KM, Stanwell P, Gearhardt AN, Collins CE, Burrows TL. The prevalence of food addiction as assessed by the Yale Food Addiction Scale: A systematic review. Nutrients. 2014;6:4552–4590. doi: 10.3390/nu6104552. doi:10.3390/nu6104552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staiger PK, Melville F, Hides L, Kambouropoulos N, Lubman DI. Can emotion-focused coping help explain the link between posttraumatic stress disorder severity and triggers for substance use in young adults? J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 2009;36:220–226. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2008.05.008. doi:10.1016/j.jsat.2008.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E, Telch CF, Rizvi SL. Development and validation of the Eating Disorder Diagnostic Scale: A brief self-report measure of anorexia, bulimia, and binge-eating disorder. Psychol. Assess. 2000;12:123–131. doi: 10.1037//1040-3590.12.2.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svaldi J, Caffier D, Tuschen-Caffier B. Emotion suppression but not reappraisal increases desire to binge in women with binge eating disorder. Psychother. Psychosom. 2010;79:188–190. doi: 10.1159/000296138. doi:10.1159/000296138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svaldi J, Griepenstroh J, Tuschen-Caffier B, Ehring T. Emotion regulation deficits in eating disorders: A marker of eating pathology or general psychopathology? Psychiatry Res. 2012;197:103–111. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2011.11.009. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2011.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanielian T. Invisible wounds of war: Psychological and cognitive injuries, their consequences, and services to assist recovery. Rand Monographs; Santa Monica, CA: 2008. L.H.J. [Google Scholar]

- Tellegen A, Ben-Porath YS. MMPI-2-RF (Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory-2 Restructured Form): Technical manual. University of Minnesota Press; Minneapolis, MN: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Vieweg WV, Julius DA, Bates J, Quinn JF, Fernandez A, Hasnain M, Pandurangi AK. Posttraumatic stress disorder as a risk factor for obesity among male military veterans. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2007;116:483–487. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2007.01071.x. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.2007.01071.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wisco BE, Miller MW, Wolf EJ, Kilpatrick D, Resnick HS, Badour CL, Marx BP, Keane TM, Rosen RC, Friedman M. The impact of proposed changes to ICD-11 on estimates of PTSD prevalence and comorbidity relative to DSM-5 and ICD-10 criteria. under review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization WHO :: Global Database on Body Mass Index [WWW Document] 2006 URL http://apps.who.int/bmi/index.jsp?introPage=intro_3.html& (accessed 4.8.16)