Abstract

Guidelines for implementing the World Health Organization’s Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) recommend prohibiting tobacco industry corporate social responsibility (CSR) initiatives, but few African countries have done so. We examined African media coverage of tobacco industry CSR initiatives to understand whether and how such initiatives were presented to the public and policymakers. We searched two online media databases (Lexis Nexis and Access World News) for all news items published from 1998 to 2013, coding retrieved items through a collaborative, iterative process. We analysed the volume, type, provenance, slant and content of coverage, including the presence of tobacco control or tobacco interest themes. We found 288 news items; most were news stories published in print newspapers. The majority of news stories relied solely on tobacco industry representatives as news sources, and portrayed tobacco industry CSR positively. When public health voices and tobacco control themes were included, news items were less likely to have a positive slant. This suggests that there is a foundation on which to build media advocacy efforts. Drawing links between implementing the FCTC and prohibiting or curtailing tobacco industry CSR programmes may result in more public dialogue in the media about the negative impacts of tobacco company CSR initiatives.

Keywords: Tobacco industry, corporate social responsibility, media, agenda setting, Africa

News coverage of tobacco issues reflects and shapes public attitudes towards smoking (Smith et al., 2008), and influences smoking behaviours (Niederdeppe, Farrelly, Thomas, Wenter, & Weitzenkamp, 2007; Pierce & Gilpin, 2001) and tobacco policy progress (Asbridge, 2004; Smith, McLeod, & Wakefield, 2005). The media perform two roles in the policymaking process: helping set the agenda, by singling out issues for discussion (Kingdon, 1984), and shaping public opinion about issues through framing (Dorfman, Wallack, & Woodruff, 2005). Agenda setting communicates to the public and policy-makers the relative importance of issues based on the amount of media attention they receive (McCombs & Shaw, 1972). Framing is a way of defining an issue so that it conveys a certain problem definition and offers an implied solution (Entman, 1993, p. 52).

Because of the media’s role in shaping policy agendas, researchers have examined media coverage of a range of tobacco topics (Ahuja, Kollath-Cattano, Valenzuela, & Thrasher, 2015; Champion & Chapman, 2005; Hilton et al., 2014). US and Australian media have been found to be supportive of many tobacco control objectives, and critical of the tobacco industry (Durrant, Wakefield, McLeod, Clegg-Smith, & Chapman, 2003; Smith, Wakefield, & Edsall, 2006). In US media, some criticism is conveyed through a ‘kids’ frame, which identifies children as tobacco industry victims (Menashe & Siegel, 1998).

Less attention has been paid to African media coverage of tobacco issues. Studies have explored youth exposure to tobacco advertisements in mass media (Agaku, Adisa, Akinyamoju, & Agboola, 2013) and the link between youth and adult consumption of mass media and risk of tobacco use (Achia, 2015). However, we are unaware of studies examining African media coverage of other tobacco issues. Although literacy rates vary (United Nations Development Program, 2011), African opinion leaders, who play key roles in health policymaking, read newspapers (Pratt, Ha, & Pratt, 2002), and African media perform an agenda setting function (Kwansah-Aidoo, 2001, 2003; Serino, 2010).

This paper explores African media coverage of tobacco industry corporate social responsibility (CSR) initiatives. Tobacco companies aggressively promote their products in African countries (Gilmore, Fooks, Drope, Bialous, & Jackson, 2015), and, in the coming decades, the African continent is expected to have the largest increase in smoking prevalence, absent intervention (Mendez, Alshanqeety, & Warner, 2013). As the tobacco industry expands into low and middle income countries, it adopts strategies that have been successful in thwarting public health and creating a tobacco-favorable policy environment in higher income countries, including CSR initiatives (Gilmore et al., 2015; Lee, Ling, & Glantz, 2012). By engaging in ‘responsible’ activities (such as corporate philanthropy), the tobacco industry enhances its image and counters negative publicity, frames the tobacco problem as one of ‘responsible’ consumption and marketing, and provides policymakers with reasons to engage with the industry (Fooks & Gilmore, 2013; Fooks et al., 2011; McDaniel & Malone, 2012). In low income countries with few public funding options, corporate philanthropy may be a particularly effective tactic to earn public and policymaker goodwill and foster a reluctance to adopt tobacco control policies.

The World Health Organization’s Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC), entered into force in 2005, addresses tobacco industry CSR via Article 5.3 and Article 13 (World Health Organization, 2011). Article 5.3 cautions treaty signatories to protect tobacco control policies from ‘commercial and other vested interests of the tobacco industry’ (World Health Organization, 2008a); implementation guidelines recommend denormalizing or regulating tobacco industry CSR by, for example, prohibiting public disclosure of tobacco industry CSR projects (World Health Organization, 2008a). Article 13 goes further, requiring parties to ban all forms of sponsorship and explicitly defining tobacco industry CSR as such (World Health Organization, 2008b). Although all but four African countries are Parties to the FCTC, only nine prohibit CSR-related sponsorship by the tobacco industry (Chad, Ghana, Guinea, Madagascar, Mauritius, Niger, Seychelles, Togo, and, despite not being a Party, Eritrea), with varying compliance levels (Tumwine, 2011; World Health Organization, 2015b).

We examined African media coverage of tobacco industry CSR initiatives. We sought to understand (1) whether tobacco industry CSR initiatives received media coverage, and therefore may potentially play a role in shaping the public and policymaker agenda; (2) if CSR initiatives were covered, whether they were covered positively or critically; (3) whether there was a change in coverage following countries’ ratification of the FCTC; and (4) whether media coverage of tobacco industry CSR ceased after countries placed restrictions on its use.

Methods

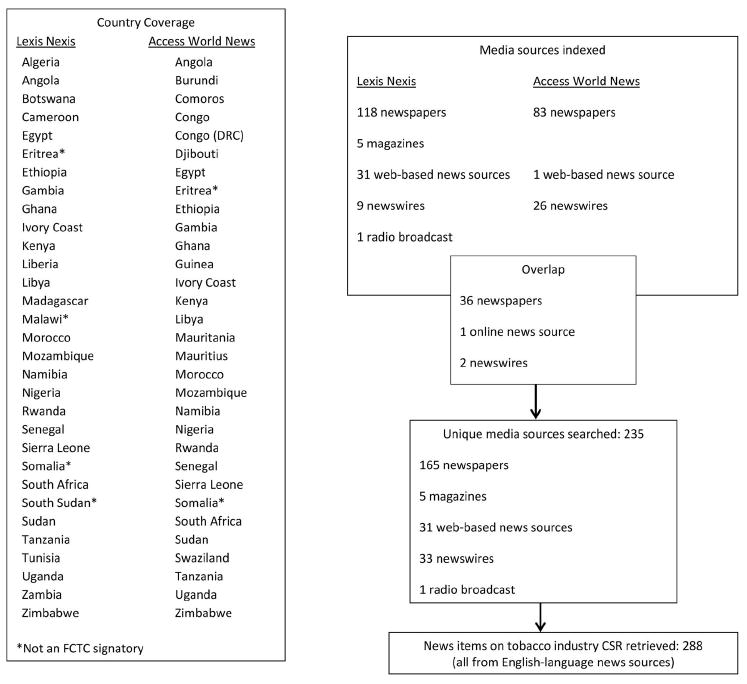

We searched two online media databases (Lexis Nexis and Access World News) for CSR-related news items published between 1998 (when several transnational tobacco companies added CSR to their initiatives) (Hirschhorn, 2004; McDaniel & Malone, 2012) and 2013 in African media concerning tobacco industry CSR. All but two African countries with English as an official language were represented in the databases (Figure 1). Most news sources were in English; however, Access World News indexed some translated material. We used a variety of search terms to locate items, starting with general terms (e.g. philanthropy and tobacco) and using retrieved items to identify more specific terms. We stopped searching once no new items were found.

Figure 1.

African countries included in media databases, and types of media sources indexed.

We coded news items through a collaborative, iterative process. We created an initial coding sheet and piloted it on 10 items. After discussion, we refined the coding sheet and drafted coding instructions. Next, two coders (the first and second authors) independently coded a randomly selected overlapping set of 24% (n = 69) of the items to establish inter-coder reliability. We assessed inter-coder reliability using Gwet’s AC1 statistic. It is an improvement on the kappa (κ) statistic, which becomes unreliable absent sufficient coding variety (Gwet, 2008). Like the κ statistic, AC1 has a value of 0–1, and is interpreted similarly. For all non-static variables, Gwet’s AC1 was .75–1.0, with an average value of 0.94.

After confirming inter-coder reliability, each coder independently coded one-half of the remaining (randomly assigned) news items. We also recoded the items coded early in the process to be consistent with the final version of the codebook. We coded story characteristics (i.e. news source, story type, date, etc.), overall slant (whether the news item was positive, negative, or neutral towards tobacco industry CSR or the tobacco industry more generally), and content. In determining the slant, we assessed the balance of positive and negative representations of the tobacco industry and tobacco industry CSR in each news item; thus, an item with a majority of supportive comments was coded as ‘positive’.

We classified some content into two categories, tobacco interest and tobacco control themes. Tobacco interest themes reflected support for the tobacco industry (e.g. references to the tobacco industry as a major taxpayer); tobacco control themes reflected support for tobacco control (e.g. references to tobacco’s economic toll). We did not conduct significance testing because the items collected were not a random sample, and we are not extrapolating from them. Rather, we report the findings from the entire population of items meeting the search criteria (Glantz, 2011).

When we found no media coverage of tobacco industry CSR, we searched the websites of three transnational tobacco companies operating in the region – British American Tobacco (BAT), Philip Morris International (PMI) and Japan Tobacco International (JTI) – for alternative evidence of any such initiatives.

This study has limitations. Although the news databases we searched covered a wide range of African news sources, they encompassed primarily print and web-based media, excluding television news broadcasts and indexing only one source of radio news (a popular form of mass media in several African countries) (Achia, 2015). In addition, for 23 countries, Access World News did not index all news items from all news sources covered; instead, it indexed selected news items, without specifying its selection criteria. Similarly, although we used a variety of search terms and searched until no new items were found, our search terms may not have been exhaustive. We may have thus failed to identify and include some relevant news items. In addition, the publication history of the news sources indexed varied, with some sources publishing continuously over the 16-year period, and others publishing only in some years. Changes in the number of items published per year may therefore reflect changes in the number of news sources available rather than growing or declining interest from existing news sources.

We also had limited knowledge of the sources of news items. American media rely heavily on press releases as sources, which often reflect positively on their organisational authors (Carpenter, 2008; Walters & Walters, 1992); the same may be true of African media. Thus, the content and slant of some news items may reflect tobacco company rather than journalist perspectives. Finally, language barriers may have introduced coding errors if news items contained vernacular with which coders were unfamiliar.

Results

Characteristics of news items and trends over time

We found 288 news items published in 48 unique sources from 1998 to 2013 regarding tobacco industry CSR in African countries. All came from English-language news sources. Most items (256) were news stories; the remainder consisted of editorials and opinion pieces (31) and 1 letter to the editor (Table 1). Five of the editorial and other opinion items were written by representatives of tobacco control or public health organisations, and four by BAT executives (three by the same author, BAT Nigeria’s press relations manager). Nearly all media items were published in newspapers (278) (Table 1).

Table 1.

English-language African media items on tobacco industry corporate social responsibility programmes, 1998–2013 (n = 288).

| Variable | No. | % |

|---|---|---|

| News source | ||

| Newspaper | 278 | 96.5 |

| News wire | 4 | 1.4 |

| Web site | 6 | 2.1 |

| Story type | ||

| News | 256 | 88.9 |

| Editorial or op-ed | 31 | 10.8 |

| Letter to the editor | 1 | 0.3 |

| Country or regiona | ||

| Africa | 1 | 0.3 |

| Cameroon | 2 | 0.7 |

| East Africa | 2 | 0.7 |

| Eritreab | 1 | 0.3 |

| Ghana | 11 | 3.8 |

| Kenya | 25 | 8.7 |

| Malawib | 5 | 1.7 |

| Namibia | 1 | 0.3 |

| Nigeria | 99 | 34.4 |

| Pan-Africa | 1 | 0.3 |

| Rwanda | 19 | 6.6 |

| South Africa | 30 | 10.4 |

| Tanzania | 29 | 10.1 |

| Uganda | 45 | 15.6 |

| Zambia | 3 | 1.0 |

| Zimbabwe | 14 | 4.9 |

| Tobacco company | ||

| British American Tobacco or subsidiary | 219 | 76.0 |

| Local tobacco company | 28 | 9.7 |

| Tobacco industry in general | 22 | 7.6 |

| Multiple companies | 17 | 5.9 |

| PMI | 1 | 0.3 |

| Imperial Tobacco | 1 | 0.3 |

| Types of CSR programmes mentioned | ||

| Environment | 76 | 26.4 |

| Education | 69 | 24.0 |

| Community development | 68 | 23.6 |

| CSR activities in general | 49 | 17.0 |

| Arts funding | 35 | 12.2 |

| Social/green reporting | 31 | 10.8 |

| Disease preventionc | 22 | 7.6 |

| Job creation | 21 | 7.3 |

| Combating child labour | 19 | 6.6 |

| Youth smoking prevention | 19 | 6.6 |

| CSR-related award/recognition | 16 | 5.6 |

| Combating illicit trade | 12 | 4.2 |

| Disaster relief | 6 | 2.1 |

| Harm reduction | 2 | 0.7 |

| Smoking cessation | 2 | 0.7 |

Indexed media in eight countries with English as an official language – Botswana, Gambia, Liberia, Mauritius (which banned tobacco industry CSR in 2008), Sierra Leone, Sudan, South Sudan (an independent country in 2011), and Swaziland – did not cover tobacco industry CSR initiatives.

Not an FCTC signatory.

Including HIV/AIDS programmes.

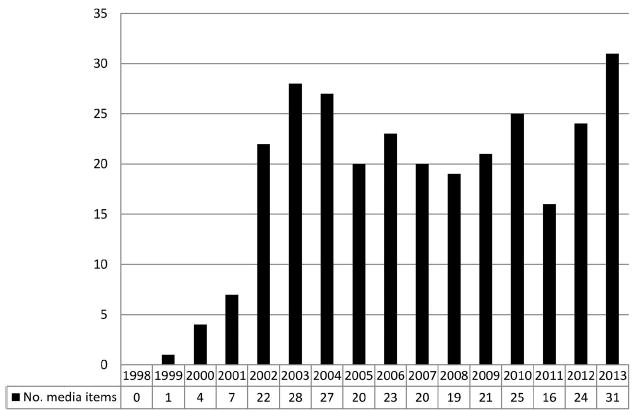

The volume of news coverage varied over the period (Figure 2). No news items were published in 1998 and fewer than 10 were published each year from 1999 to 2001, perhaps an indicator of the time lag between CSR development and implementation (Figure 2). From 2002 to 2013 the annual number of news items ranged from 16 to 31 (Figure 2). Items appeared in publications from 13 African countries, all with English as an official language, and all but two (Eritrea and Malawi) parties to the FCTC (United Nations, 2015) (Table 1). Indexed media in eight countries with English as an official language – Botswana, Gambia, Liberia, Mauritius (which restricted tobacco industry CSR in 2008), Sierra Leone, Sudan, South Sudan (an independent country in 2011), and Swaziland – did not cover tobacco industry CSR initiatives. To explore whether this lack of coverage reflected a lack of media interest in tobacco industry CSR initiatives or a lack of initiatives on which to report, we examined the BAT, PMI, and JTI websites for historical and current information on their CSR programmes in these eight countries, including any posted social or sustainability reports; we found no mention of any in these countries.

Figure 2.

Number of media items published on tobacco industry CSR initiatives in English-language African media, 1998–2013 (n = 288).

Country and company trends

Nigerian media produced the most news items over the 16-year period (99 or 34.4%), perhaps due to the country’s large population, large number of English-language newspapers (16; second only to South Africa’s 52), and strong BAT presence: in 2003, the company opened a manufacturing facility in Nigeria (Nigeria Tobacco Situational Analysis Coalition & Drope, 2011) and established the BAT Nigeria Foundation to oversee its CSR projects (British American Tobacco Nigeria, 2014). BAT’s regional dominance – it controls more than 90% of the market in 10 African countries (Action on Smoking and Health (UK), 2008) – was also evidenced by the media attention directed at BAT’s or its subsidiaries’ CSR initiatives, which were more frequently covered than those of all other tobacco companies (Table 1).

Types of CSR initiatives and recipients of aid

News items reported on a broad range of tobacco company CSR activities. Environmental programmes received the most coverage (76, 26.4%) (Table 2); more than half of these (43) were BAT-sponsored tree-planting initiatives in tobacco-growing countries with deforestation problems due to reliance on wood for tobacco curing. Education and community development programmes, including poverty alleviation and scholarships or donations to schools, were also commonly covered (69 and 68 news items each, respectively) (Table 2). Less commonly covered were youth smoking prevention programmes, ‘green reporting’ (e.g. disclosures regarding a company’s carbon footprint), arts funding, disaster relief, and harm reduction – tobacco industry CSR programmes that have been promoted by the industry in the USA and/or UK (Landman, Ling, & Glantz, 2002; Otanez & Glantz, 2011; Peeters & Gilmore, 2015; Tesler & Malone, 2008).

Table 2.

Content of English-language African media items concerning tobacco industry corporate social responsibility programmes, 1998–2013 (n = 288, except where noted).a

| Content | Total | % | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sources quoted | |||

| Tobacco industry representative | 201 | 69.8 | ‘It is our corporate social responsibility to give back part of the profits from the gains made in the tobacco industry by ploughing back to the community which we serve’ (Silumbu, 2013). |

| CSR initiative recipient | 64 | 22.2 | ‘Before this donation almost 50% of our children were sitting on the floor but we are now happy that there is no child who will be sitting on the floor’ (Jacob, 2013). |

| Government official | 110 | 38.2 | ‘The Minister of Information … lauded British American Tobacco Ghana for their sense of responsibility in reducing the harmful effects of smoking’ (‘BAT against youth smoking’ , 2001). |

| Public health or tobacco control organization | 46 | 16.0 | ‘What we need in Lagos State is a strong legislation … to make the tobacco industry accountable for the deaths, diseases, environmental, social and other costs associated with smoking’ (Haruna, 2013). |

| Overall impression (non-opinion items) | 256 | 88.9 | |

| Positive | 213 | 83.2 | ‘British American Tobacco is committed to supporting education development in Ghana’ (‘BAT gives c115 m to 3 institutions’ , 2001). |

| Negative | 22 | 8.6 | ‘The Federal Government should not allow tobacco companies to be using the old tobacco industry ploy to improve their image by contributing to a public concern’ (‘Ultimatum on tobacco advert unrealistic, says body’ , 2001). |

| Neutral/mixed | 21 | 8.2 | ‘British American Tobacco has brought to fore the implications of stifling a legal tobacco industry, as advocacy groups kick against all forms of tobacco advertising’ (Ekwujuru, 2013). |

| Overall impression (opinion items) | 32 | 11.1 | |

| Positive | 8 | 25.0 | ‘We are a legitimate company who conducts our business in a professional and responsible way … often going above and beyond our legal requirements’ (D’Souza, 2013). |

| Negative | 20 | 62.5 | ‘BAT uses hefty donations to poor governments as a way to deflect criticism, block tobacco regulation, and divert the public’s attention from the impact of tobacco’ (Tumwine, 2007). |

| Neutral/mixed or unclear | 4 | 12.5 | ‘As the tobacco control bill provokes debate between two major parties of stakeholders, it is apparent that the choice is between guaranteeing banal economic returns and closing the eyes to the negative toll of tobacco consumption on public health’ (Obi, 2009). |

| Tobacco control themes | |||

| Policies to regulate industry | 81 | 28.1 | ‘All packs shall have tar and nicotine levels displayed on the packs and the health warning clause will be in English and Swahili’ (‘BATU delivers 60% share issue’ , 2003). |

| Negative impacts of tobacco industry other than health | 72 | 25.0 | ‘The negative impact of tobacco growing includes the accumulation of chemical compounds in soils’ (‘Tobacco firms should be socially responsible’, 2008). |

| Tobacco-caused disease or death | 66 | 22.9 | ‘The African share of the global tobacco induced fatalities is an incredulous 870,000 deaths per annum’ (‘The campaign against tobacco’ , 2006). |

| Youth smoking | 46 | 16.0 | ‘In the North east, children start to smoke as early as 10 years of age’ (‘Tobacco … fresh challenges before healthcare givers’ , 2008). |

| Mention of CSR as image improvement | 43 | 14.9 | ‘The average reader knows all too well that the tobacco industry pumps more money into image laundering in the guise of corporate social responsibility than on actual CSR.’ (‘To smoke or not to smoke’ , 2007) |

| Advertising/targeting youth | 24 | 8.3 | ‘We now expect more reports on the tobacco industry tactics to undermine the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control in their bid to addict young smokers’ (Abah, 2013). |

| Tobacco’s economic toll | 14 | 4.9 | ‘The state had so far sunk N221.7 billion treating tobacco-related illnesses’ (‘To smoke or not to smoke’, 2007). |

| Tobacco interest themes | |||

| Tobacco industry as source of jobs | 70 | 24.0 | ‘If passed into law, the National Tobacco Bill … will lead to at least 400,000 Nigerians being thrown into the unemployment market’ (‘Anti-tobacco bill will lead to 400,000 job losses – Senator Abedibu’, 2009). |

| Taxes paid by company as economic benefit | 49 | 17.0 | ‘In 2012, BAT Uganda contributed 72 billion [shillings] in taxes to the government’ (D’Souza, 2013). |

| Tobacco farming as lucrative crop | 26 | 9.0 | ‘The company will pay out another 20 m [shillings] to the farmers as a bonus for a job well done’ (‘Farmers bag Sh3b’, 2003). |

| Legal/legitimate business | 19 | 6.6 | ‘Because we manufacture and distribute a legal, yet risky product, we believe it is all the more important that we do so responsibly and openly’ (‘Tobacco company spreads lies and deception – WHO’ , 2002). |

| Informed choice/adult consumers | 18 | 6.3 | ‘The reality is that adults that have made the conscious decision to smoke will continue to do so’ (D’Souza, 2013). |

News items were coded for multiple responses in each category; the percentages reported in each section reflect the percent of items coded as ‘yes’.

Within broad categories of tobacco industry CSR activities, we identified a range of specific initiatives or recipients of aid (e.g. the Social Responsibility in Tobacco Production Programme, the University of Ghana), with most mentioned in only 1–2 news items. However, there were several programmes or organisations repeatedly singled out by the media, including tree-planting programmes (43 mentions) and the BAT Nigeria Foundation (49 mentions).

Sources

In describing tobacco company CSR programmes, most news items relied on statements from tobacco industry representatives (201, 69.8%) (Table 2). A 2009 article in Nigeria’s Daily Champion on a BAT Nigeria scholarship programme, for example, included a statement from a BAT Nigeria executive that the programme reflected the company’s ‘commitment to continually add value to its host communities’ (‘Oyo government partners BATN on education’ , 2009). Government officials were another source of information or opinion about particular CSR programmes (110, 38.2%) (Table 2); most (90, 81.8%) supported them. In some cases, government officials were present alongside tobacco industry representatives at CSR-related events. For example, a 2002 article in Zimbabwe’s Daily News reported that the Minister of Health and Child Welfare presided over the opening of BAT’s new employee medical facility, commending the company for ‘focusing on the health and well-being of its employees’ (‘British American Tobacco builds $6 m staff clinic’ , 2002). News items infrequently included statements from public health or tobacco control organisations critical of the tobacco industry or tobacco industry CSR (46, 16.0%) (Table 3). Indeed, the majority (179, 62.2%) included one or more statements from tobacco industry representatives, none from public health or tobacco control organisations.

Table 3.

Negative slant towards tobacco industry CSR initiatives in news items from selected African countries, pre- and post-FCTC ratification.

| Country | Total news items | Pre-FCTC ratification, negative slant (%, n) | Post-FCTC ratification, negative slant (%, n) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kenya | 25 | 0% (0) | 29.4% (5) |

| Nigeria | 99 | 7.1% (2) | 19.7% (14) |

| Uganda | 45 | 9.1% (3) | 33.3% (4) |

| South Africa | 30 | 31.3% (5) | 35.7% (5) |

| Tanzania | 29 | 0% (0) | 0% (0) |

Slant of news items

Due to the preponderance of tobacco industry voices in media items, the majority of all non-opinion news items conveyed a positive impression of tobacco industry CSR initiatives (213/256, 83.2%) (Table 2). Non-opinion news items that conveyed a negative impression (22) were concentrated among Nigerian (6), South African (6) and Kenyan (5) media, with the remainder from Ugandan (2), Ghanaian (2) and regional (1) media. Typically, items with a negative slant included one or more statements by public health or tobacco control advocates critical of tobacco industry CSR, who labelled it, for example, an image-enhancement ‘ploy’ (‘Ultimatum on tobacco advert unrealistic, says body’, 2001) or an ‘empty public relations gesture’ (‘Twenty-five billion up in smoke’ , 2002). News items with a negative slant were also less likely than those with a positive slant to include quotes from tobacco industry representatives (36.4% vs. 78.8%).

Among the small number of opinion pieces, critical voices prevailed: 20 of the 32 items (62.5%) conveyed a negative impression of tobacco industry CSR (Table 2). Half of the negative opinion pieces (10) were published in Nigerian media, most (8) by unidentified authors; the remainder were published in Ugandan (5), South African (4) or Zambian (1) media. Several were prompted by World No Tobacco Day (4), the FCTC (3), or national tobacco control legislation (3), with the authors criticising the tobacco industry and/or tobacco industry CSR in the context of these larger efforts.

Tobacco control vs. tobacco industry themes

Although nearly half of news items (125, 43.4%) offered little information beyond a description of a CSR project and its alleged positive impact, the remainder (163, 56.6%) included additional information that we coded under the categories ‘tobacco control’ or ‘tobacco interest’ themes. One of the most common tobacco control themes was a reference to tobacco control policies (81, 28.1%) (Table 2) such as the FCTC, mentioned in 31 of these articles (38.3%). News items more commonly mentioned support for such policies (54, 66.7%) rather than opposition, describing the FCTC, for example, as ‘reaffirm[ing] the right of all people to the highest standard of health’ (Baafi, 2010). Other tobacco control themes that received more than minimal attention included mention of tobacco-caused death and disease (66, 22.9%) and other negative impacts of tobacco, such as environmental degradation in tobacco-growing areas (72, 25.0%) (Table 2). Youth-focused tobacco control themes were uncommon (Table 2).

The most common tobacco interest themes were those that focused on the tobacco industry’s economic benefits, including taxes paid by tobacco companies to governments (49, 17.0%), employment generated by the tobacco industry (70, 24.0%), and tobacco as a driver of economic development or source of foreign earnings (26, 9.0%) (Table 2). For example, in a 2006 article in Rwanda’s New Times, a government minister, receiving a BAT donation, stated that ‘there is no doubt that you are one of the leading taxpayers in the country and therefore leading players in the country’s economic growth’ (‘BAT donates Frw5 million computers’ , 2006). Tobacco interest themes used to defend the industry in the USA – references to smokers as (informed) adults and to tobacco products as ‘legal’ – were infrequently mentioned (Menashe & Siegel, 1998) (Table 2).

When tobacco control or tobacco interest themes were mentioned, both were most often mentioned in the same news item (75 of 163), and the slant was most often positive (50.7%) or neutral/mixed (18.7%) towards tobacco industry CSR. Among items that mentioned only tobacco control themes (53), the majority had a negative or neutral slant (27, 50.9%); among those that mentioned only tobacco industry themes (35), all (100%) had a positive slant.

Post-FCTC slant

In exploring whether there was more negative media coverage of tobacco industry CSR after countries ratified the FCTC, we limited our analysis to FCTC parties (as of 1 January 2014) with at least 25 news items on tobacco industry CSR (Kenya, Nigeria, South Africa, Tanzania, and Uganda). All ratified the FCTC between 2004 and 2007. For three countries (Nigeria, Kenya, and Uganda), there was more negative coverage post-ratification, while two (South Africa and Tanzania) had no change (Table 3). We also examined whether government officials quoted in news items expressed more negative views towards tobacco industry CSR post-FCTC ratification. We found no change: the majority supported such programmes regardless of time period.

Coverage in countries that have restricted tobacco industry CSR

Among the nine countries that have restricted CSR-related sponsorship, only two were represented in our population of news items: Eritrea and Ghana, a reflection, perhaps, of successful implementation of the restrictions. Eritrea had only one news item on tobacco industry CSR; however, it was published in 2006, after its law prohibiting tobacco industry CSR went into effect. It was a brief account of a BAT afforestation project in Eritrea. There were 11 news items from Ghana, none published after the restriction on CSR-related sponsorship came into effect.

Discussion

Since 1999, English-language African media have been covering tobacco industry CSR projects. Given our news databases’ coverage limitations, it is unknown if coverage has increased over time, as tobacco companies invest more resources (including, possibly, CSR) in the region. Although the topic received media attention in 13 African countries, coverage was uneven, due perhaps to national differences in views of the legitimacy and aggregate social value of the tobacco industry, journalists’ perceptions of what constitutes news, or the degree of tobacco company investment in CSR. The frequently-covered BAT Nigeria Foundation, for example, represents BAT’s only Africa-based charitable organisation, and claims to support seven focus areas (Ihugba, 2012); other tobacco companies may have fewer or smaller CSR programmes. Nonetheless, our study suggests that tobacco industry CSR plays a role in shaping the public agenda in some African countries.

Although there was some overlap between the type of CSR programmes covered in African media and those that have been promoted by tobacco companies elsewhere, there were notable differences that may reflect regional variations in tobacco industry reputational vulnerabilities. For example, the limited coverage of youth smoking prevention programmes suggests that the ‘kids’ frame, used to criticise tobacco companies in the USA, is not salient in African countries. The limited number of youth-related tobacco control themes in news items, including mention of youth smoking and of the tobacco industry targeting youth, offers further support for this view. On the other hand, environmental issues, particularly deforestation in African tobacco-growing countries, appear to represent more of a reputational threat, given the share of media attention directed towards tobacco industry environmental programmes.

The results suggest that tobacco companies enjoy a degree of success in shaping their corporate image through CSR-related stories in the news media: journalists relied largely (and often solely) on tobacco industry representatives as sources, resulting in a positive portrayal of tobacco industry CSR. Public health or tobacco control advocates, although mostly excluded, brought a more critical perspective, such that news items that included their voices were more likely to have a negative slant. These findings are consistent with the idea that African news media, like their American counterparts, rely at least partly on press releases as sources of news. It is also possible that the positive slant reflects journalists’ views. Given other public health challenges faced by African countries, including HIV/AIDS and lack of access to clean water and sanitation (World Health Organization, 2015a), journalists may not share tobacco control advocates’ perspective regarding CSR’s public health significance.

Despite the FCTC’s critical view of tobacco industry CSR, FCTC ratification was not consistently associated with more negative media portrayals of CSR; more data from additional media sources could provide clearer evidence. We found greater consistency when examining accounts of government officials’ support for CSR programmes, with no downturn following FCTC ratification. This may further reflect tobacco company authorship of news items, and/or tobacco companies’ ties to supportive government officials.

The association between restrictions on tobacco industry CSR-related sponsorship and media portrayals of CSR was unclear, due to limited data. It was unknown, for example, if a lack of reporting on tobacco industry CSR both pre- and post-restrictions was an indicator of missing data or of successful implementation of the restrictions. Eritrea’s example – one article on tobacco industry CSR published post-restrictions – suggested that restrictions were no guarantee of an absence of tobacco industry CSR programmes on which to report.

The concentration of negative perspectives on tobacco industry CSR among a handful of countries with active tobacco control communities (Drope, 2011) points to the potential role of community activism and media advocacy in influencing future media coverage. Nigerian media accounted for a large share of critical news items; Nigerian tobacco control organisations have conducted at least one media training session explaining the need for strong, FCTC-compliant tobacco control measures (Haruna, 2007). Media advocacy – including adopting the tobacco industry tactic of issuing press releases – in other African nations might play a similar role in shaping news coverage of the tobacco industry. Our finding that news coverage that included tobacco control themes was less likely to have a positive slant suggests that there is a solid foundation on which to build such efforts.

Directions for future research

Our study is but one component of a larger investigation of African media coverage of tobacco issues. Research assessing additional media sources, including social media and French language media, is also needed, to shed more light on the potential impact of FCTC ratification on media coverage of the industry. Research examining the newsmaking enterprise, including how news stories are selected, who is considered an appropriate source, and the influence of journalists’ perspectives, would also be valuable, particularly in terms of media advocacy applications.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute [R01 CA120138].

Footnotes

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Abah B. This Day journalist wins inaugural tobacco control journalism fellowship. This Day 2013 Oct 31; [Google Scholar]

- Achia TN. Tobacco use and mass media utilization in sub-Saharan Africa. PLoS One. 2015;10(2):e0117219. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0117219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Action on Smoking and Health (UK) BAT’s African footprint. 2008 Retrieved from http://www.ash.org.uk/files/documents/ASH_685.pdf.

- Agaku IT, Adisa AO, Akinyamoju AO, Agboola SO. A cross-country comparison of the prevalence of exposure to tobacco advertisements among adolescents aged 13–15 years in 20 low and middle income countries. Tobacco Induced Diseases. 2013;11(1):11. doi: 10.1186/1617-9625-11-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahuja RV, Kollath-Cattano CL, Valenzuela MT, Thrasher JF. Chilean news media coverage of proposed regulations on tobacco use in national entertainment media, May 2011-February 2013. Tobacco Control. 2015;24(5):521–522. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014-051861. doi:tobaccocontrol-2014-051861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anti-tobacco bill will lead to 400,000 job losses – Senator Abedibu. Leadership 2009 Mar 9; [Google Scholar]

- Asbridge M. Public place restrictions on smoking in Canada: Assessing the role of the state, media, science and public health advocacy. Social Science & Medicine. 2004;58:13–24. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(03)00154-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baafi AAA. Country behind schedule on aspects of tobacco control framework convention. Public Agenda 2010 Apr; [Google Scholar]

- BAT against youth smoking. Accra Mail 2001 Dec 20; [Google Scholar]

- BAT donates Frw5 million computers. The New Times 2006 Jun 26; [Google Scholar]

- BAT gives c115 m to 3 institutions. Ghanaian Chronicle 2001 Nov 8; [Google Scholar]

- BATU delivers 60% share issue. New Vision 2003 May 22; [Google Scholar]

- British American Tobacco builds $6 m staff clinic. The Daily News 2002 Oct 30; [Google Scholar]

- British American Tobacco Nigeria. 2014 The BATN Foundation. Retrieved from http://www.batnigeria.com/group/sites/BAT_7YKM7R.nsf/vwPagesWebLive/DO7YLFVN?opendocument.

- Carpenter S. How online citizen journalism publications and online newspapers utilize the objectivity standard and rely on external sources. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly. 2008;85(3):531–548. [Google Scholar]

- Champion D, Chapman S. Framing pub smoking bans: An analysis of Australian print news media coverage, March 1996-March 2003. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health. 2005;59(8):679–684. doi: 10.1136/jech.2005.035915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorfman L, Wallack L, Woodruff K. More than a message: Framing public health advocacy to change corporate practices. Health Education & Behavior. 2005;32(3):320–336. doi: 10.1177/1090198105275046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drope J, editor. Tobacco control in Africa: People, politics, and policies. New York, NY: Anthem Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- D’Souza J. Regulation of tobacco industry should be fair to all stakeholders. The Monitor 2013 Jun 5; [Google Scholar]

- Durrant R, Wakefield M, McLeod K, Clegg-Smith K, Chapman S. Tobacco in the news: An analysis of newspaper coverage of tobacco issues in Australia, 2001. Tobacco Control. 2003;12(Suppl. 2):ii75–8.1. doi: 10.1136/tc.12.suppl_2.ii75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekwujuru P. No tobacco day – BAT cautions on stifling legal tobacco industry. Vanguard. 2013 Jun 9; Retrieved from http://www.vanguardngr.com/2013/06/no-tobacco-day-bat-cautions-on-stifling-legal-tobacco-industry/

- Entman RM. Framing: Toward clarification of a fractured paradigm. Journal of Communication. 1993;43(4):51–58. [Google Scholar]

- Farmers bag Sh3b. New Vision 2003 May 10; [Google Scholar]

- Fooks GJ, Gilmore AB. Corporate philanthropy, political influence, and health policy. PLoS One. 2013;8(11):e80864. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0080864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fooks GJ, Gilmore AB, Smith KE, Collin J, Holden C, Lee K. Corporate social responsibility and access to policy elites: An analysis of tobacco industry documents. PLoS Medicine. 2011;8(8):e1001076. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmore AB, Fooks G, Drope J, Bialous SA, Jackson RR. Exposing and addressing tobacco industry conduct in low-income and middle-income countries. The Lancet. 2015;385(9972):1029–1043. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60312-9. doi: S0140-6736(15)60312-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glantz SA. Primer of biostatistics. 7. New York, NY: McGraw Hill Medical; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Gwet K. Computing inter-rater reliability and its variance in the presence of high agreement. British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology. 2008;61:29–48. doi: 10.1348/000711006X126600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haruna G. Tobacco’s harvest of evils to humans, economy. This Day 2007 Nov 5; [Google Scholar]

- Haruna G. ‘Tobacco money worse than blood diamonds’. This Day 2013 Sep 26; [Google Scholar]

- Hilton S, Wood K, Bain J, Patterson C, Duffy S, Semple S. Newsprint coverage of smoking in cars carrying children: A case study of public and scientific opinion driving the policy debate. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:1116. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-1116. doi:1471-2458-14-1116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirschhorn N. Corporate social responsibility and the tobacco industry: Hope or hype? Tobacco Control. 2004;13(4):447–453. doi: 10.1136/tc.2003.006676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ihugba BU. CSR stakeholder engagement and Nigerian tobacco manufacturing sub-sector. African Journal of Economic and Management Studies. 2012;3(1):42–63. [Google Scholar]

- Jacob M. Tobacco firm donates school desks. Tanzania Daily News 2013 Jul 15; [Google Scholar]

- Kingdon J. Agenda, alternatives, and public policies. Boston: Little, Brown, and Co; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Kwansah-Aidoo K. The appeal of qualitative methods to traditional agenda-setting research: An example from West Africa. International Communication Gazette. 2001;63(6):521–537. [Google Scholar]

- Kwansah-Aidoo K. Events that matter: Specific incidents, media coverage, and agenda-setting in a Ghanaian context. Canadian Journal of Communication. 2003;28:43–66. [Google Scholar]

- Landman A, Ling PM, Glantz SA. Tobacco industry youth smoking prevention programs: Protecting the industry and hurting tobacco control. American Journal of Public Health. 2002;92(6):917–930. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.6.917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Ling PM, Glantz SA. The vector of the tobacco epidemic: Tobacco industry practices in low and middle-income countries. Cancer Causes and Control. 2012;23(Suppl. 1):117–129. doi: 10.1007/s10552-012-9914-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCombs ME, Shaw DL. The agenda-setting function of mass media. Public Opinion Quarterly. 1972;36(2):176–187. [Google Scholar]

- McDaniel PA, Malone RE. British American Tobacco’s partnership with Earthwatch Europe and its implications for public health. Global Public Health. 2012;7(1):14–28. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2010.549832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menashe CL, Siegel M. The power of a frame: An analysis of newspaper coverage of tobacco issues – United States 1985–1996. Journal of Health Communication. 1998;3(4):307–325. doi: 10.1080/108107398127139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendez D, Alshanqeety O, Warner KE. The potential impact of smoking control policies on future global smoking trends. Tobacco Control. 2013;22(1):46–51. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050147. doi:tobaccocontrol-2011-050147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niederdeppe J, Farrelly MC, Thomas KY, Wenter D, Weitzenkamp D. Newspaper coverage as indirect effects of a health communication intervention: The Florida Tobacco Control Program and youth smoking. Communication Research. 2007;34(4):382–405. [Google Scholar]

- Drope J. Nigeria Tobacco Situational Analysis Coalition. Nigeria. In: Drope J, editor. Tobacco control in Africa: People, politics, and policies. New York, NY: Anthem Press; 2011. pp. 201–218. [Google Scholar]

- Obi I. Tobacco control bill: Making a choice between economy and citizen’s health. Business Day 2009 Aug 5; [Google Scholar]

- Otanez M, Glantz SA. Social responsibility in tobacco production? Tobacco companies’ use of green supply chains to obscure the real costs of tobacco farming. Tobacco Control. 2011;20(6):403–411. doi: 10.1136/tc.2010.039537. doi:tc.2010.039537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oyo government partners BATN on education. Daily Champion 2009 Dec 23; [Google Scholar]

- Peeters S, Gilmore AB. Understanding the emergence of the tobacco industry’s use of the term tobacco harm reduction in order to inform public health policy. Tobacco Control. 2015;24(2):182–189. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051502. doi:tobaccocontrol-2013-051502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce JP, Gilpin EA. News media coverage of smoking and health is associated with changes in population rates of smoking cessation but not initiation. Tobacco Control. 2001;10(2):145–153. doi: 10.1136/tc.10.2.145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratt CB, Ha L, Pratt CA. Setting the public health agenda on major diseases in sub-Saharan Africa: African popular magazines and medical journals, 1981–1997. Journal of Communication. 2002;52(4):889–904. [Google Scholar]

- Serino TK. ‘Setting the agenda’: The production of opinion at the Sunday Times. Social Dynamics. 2010;36(1):99–111. [Google Scholar]

- Silumbu A. Premium TAMA donates learning materials worth K1 million to Mangochi schools. Malawi News Agency 2013 Nov 15; [Google Scholar]

- Smith KC, McLeod K, Wakefield M. Australian letters to the editor on tobacco: Triggers, rhetoric, and claims to legitimate voice. Qualitative Health Research. 2005;15(9):1180–1198. doi: 10.1177/1049732305279145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith KC, Wakefield M, Edsall E. The good news about smoking: How do U.S. newspapers cover tobacco issues? Journal of Public Health Policy. 2006;27(2):166–181. doi: 10.1057/palgrave.jphp.3200079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith KC, Wakefield MA, Terry-McElrath Y, Chaloupka FJ, Flay B, Johnston L. Relation between newspaper coverage of tobacco issues and smoking attitudes and behaviour among American teens. Tobacco Control. 2008;17(1):17–24. doi: 10.1136/tc.2007.020495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tesler LE, Malone RE. Corporate philanthropy, lobbying, and public health policy. American Journal of Public Health. 2008;98(12):2123–2133. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.128231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The campaign against tobacco. This Day 2006 May 18; [Google Scholar]

- Tobacco company spreads lies and deception – WHO. South African Press Association; 2002. Mar 7, [Google Scholar]

- Tobacco firms should be socially responsible. New Vision 2008 Jun 18; [Google Scholar]

- Tobacco … fresh challenges before healthcare givers. This Day 2008 Jan 21; [Google Scholar]

- To smoke or not to smoke. Daily Trust 2007 Nov 20; [Google Scholar]

- Tumwine J. BAT sponsorship unacceptable. East African Business Week 2007 Aug 27; [Google Scholar]

- Tumwine J. Implementation of the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control in Africa: Current status of legislation. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2011;8(11):4312–4331. doi: 10.3390/ijerph8114312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Twenty-five billion up in smoke. South African Press Association; 2002. Jun 26, [Google Scholar]

- Ultimatum on tobacco advert unrealistic, says body. The Guardian 2001 Aug 21; [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. United Nations Treaty Collection. 2015 Retrieved from https://treaties.un.org/pages/ViewDetails.aspx?src=TREATY&mtdsg_no=IX-4&chapter=9&lang=en.

- United Nations Development Program. Adult literacy rate, both sexes (% aged 15 and above) 2011 Retrieved from http://hdrstats.undp.org/en/indicators/101406.html.

- Walters LM, Walters TN. Environment of confidence: Daily newspaper use of press releases. Public Relations Review. 1992;18(1):31–46. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Guidelines for implementation of Article 5.3 of the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. 2008a Retrieved from http://www.who.int/fctc/guidelines/article_5_3.pdf.

- World Health Organization. Guidelines for implementation of Article 13 of the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (Tobacco advertising, promotion, and sponsorship) 2008b Retrieved from http://www.who.int/fctc/guidelines/article_13.pdf?ua=1.

- World Health Organization. WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control: Guidelines for implementation. 2011 Retrieved from http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2011/9789241501316_eng.pdf.

- World Health Organization. The African regional health report: The health of the people. 2015a Retrieved from http://www.who.int/bulletin/africanhealth/en/

- World Health Organization. WHO report on the global tobacco epidemic, 2015: Raising taxes on tobacco. 2015b Retrieved from http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/178574/1/9789240694606_eng.pdf?ua=1.