Abstract

Members of the Rrf2 superfamily of transcription factors are widespread in bacteria but their functions are largely unexplored. The few that have been characterized in detail sense nitric oxide (NsrR), iron limitation (RirA), cysteine availability (CymR) and the iron sulfur (Fe-S) cluster status of the cell (IscR). In this study we combined ChIP- and dRNA-seq with in vitro biochemistry to characterize a putative NsrR homologue in Streptomyces venezuelae. ChIP-seq analysis revealed that rather than regulating the nitrosative stress response like Streptomyces coelicolor NsrR, Sven6563 binds to a conserved motif at a different, much larger set of genes with a diverse range of functions, including a number of regulators, genes required for glutamine synthesis, NADH/NAD(P)H metabolism, as well as general DNA/RNA and amino acid/protein turn over. Our biochemical experiments further show that Sven6563 has a [2Fe-2S] cluster and that the switch between oxidized and reduced cluster controls its DNA binding activity in vitro. To our knowledge, both the sensing domain and the putative target genes are novel for an Rrf2 protein, suggesting Sven6563 represents a new member of the Rrf2 superfamily. Given the redox sensitivity of its Fe-S cluster we have tentatively named the protein RsrR for Redox sensitive response Regulator.

Filamentous Streptomyces bacteria produce bioactive secondary metabolites that account for more than half of all known antibiotics as well as anticancer, anti-helminthic and immunosuppressant drugs1,2. More than 600 Streptomyces species are known and each encodes between 10 and 50 secondary metabolites but only 25% of these compounds are produced in vitro. As a result, there is huge potential for the discovery of new natural products from Streptomyces and their close relatives. This is revitalizing research into these bacteria and Streptomyces venezuelae has recently emerged as a new model for studying their complex life cycle, in part because of its unusual ability to sporulate to near completion when grown in submerged liquid culture. This means the different tissue types involved in the progression to sporulation can be easily separated and used for tissue specific analyses such as RNA sequencing and chromatin immunoprecipitation and sequencing (RNA- and ChIP-seq)3,4. Streptomyces species are complex bacteria that grow like fungi, forming a branching, feeding substrate mycelium in the soil that differentiates upon nutrient stress into reproductive aerial hyphae that undergo cell division to form spores5. Differentiation is closely linked to the production of antibiotics, which are presumed to offer a competitive advantage when nutrients become scarce in the soil.

Streptomyces bacteria are well adapted for life in the complex soil environment with more than a quarter of their ~9 Mbp genomes encoding one and two-component signaling pathways that allow them to rapidly sense and respond to changes in their environment6. They are facultative aerobes and have multiple systems for dealing with redox, oxidative and nitrosative stress. Most species can survive for long periods in the absence of O2, most likely by respiring nitrate, but the molecular details are not known7. They deal effectively with nitric oxide (NO) generated either endogenously through nitrate respiration7 or in some cases from dedicated bacterial NO synthase (bNOS) enzymes8 or by other NO generating organisms in the soil9. We recently characterized NsrR, which is the major bacterial NO stress sensor, in Streptomyces coelicolor (ScNsrR). NsrR is a dimeric Rrf2 family protein with one [4Fe-4S] cluster per monomer that reacts rapidly with up to eight molecules of NO10,11. Nitrosylation of the Fe-S cluster results in derepression of the nsrR, hmpA1 and hmpA2 genes11, which results in transient expression of HmpA NO dioxygenase enzymes that convert NO to nitrate12,13,14. The Rrf2 superfamily of bacterial transcription factors is still relatively poorly characterized, but many have C-terminal cysteine residues that are known or predicted to coordinate Fe-S clusters. Other characterized Rrf2 proteins include RirA which senses iron limitation most likely through an Fe-S cluster15 and IscR which senses the Fe-S cluster status of the cell16.

In this work we report the characterization of the S. venezuelae Rrf2 protein Sven6563 that is annotated as an NsrR homologue. In fact, it shares only 27% primary sequence identity with ScNsrR and is not genetically linked to an hmpA gene (Supplementary Figure S1). We purified the protein from E. coli under anaerobic conditions and found that it is a dimer with each monomer containing a reduced [2Fe-2S] cluster that is rapidly oxidized but not destroyed by oxygen. Thus, the [2Fe-2S] cofactor is different to the [4Fe-4S] cofactors in the S. coelicolor and Bacillus subtilis NsrR proteins. The [2Fe-2S] cluster of Sven6563 switches easily between oxidized and reduced states and we provide evidence that this switch controls its DNA binding activity, with holo-RsrR showing highest affinity for DNA in its oxidised state. We have tentatively named the protein RsrR for Redox sensitive response Regulator. ChIP-seq and ChIP-exo analysis allowed us to define the RsrR binding sites on the S. venezuelae genome with RsrR binding to class 1 target genes with an 11-3-11 bp inverted repeat motif and class 2 target genes with a single repeat or half site. Class 1 target genes suggest a primary role in regulating NADH/NAD(P)H and glutamate/glutamine metabolism rather than nitrosative stress. The sven6562 gene, which is divergent from rsrR, is the most highly induced transcript, up 5.41-fold (log2), in the ∆rsrR mutant and encodes a putative NAD(P)+ binding repressor in the NmrA family. Other class 1 target genes are not significantly affected by loss of RsrR suggesting additional levels of regulation, possibly including the divergently expressed Sven6562 (NmrA). Taken together our data suggest that RsrR is a new member of the Rrf2 family and extends the known functions of this superfamily, potentially sensing redox via a [2Fe-2S] cofactor in a mechanism that has only previously been observed in SoxR proteins.

Results

Identifying RsrR target genes in S. venezualae

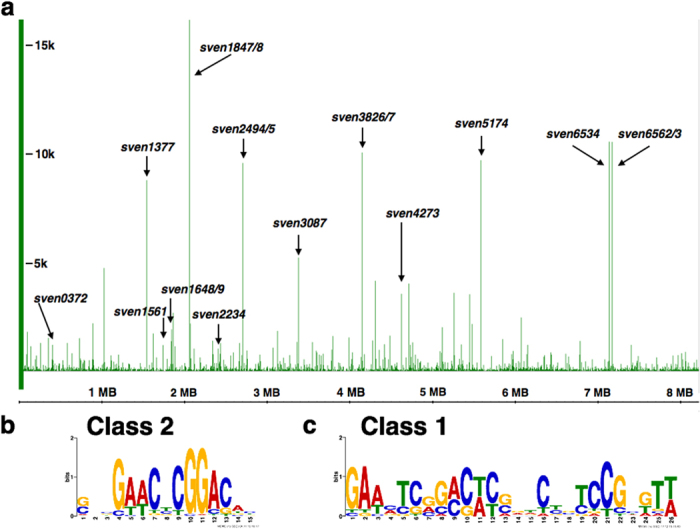

We previously reported a highly specialized function for the NO-sensing NsrR protein in S. coelicolor. ChIP-seq against a 3xFlag-ScNsrR protein showed that it only regulates three genes, two of which encode NO dioxygenase HmpA enzymes, and the nsrR gene itself11. To investigate the function of RsrR, the putative NsrR homologue in S. venezuelae, we constructed an S. venezualae ∆rsrR mutant expressing an N-terminally 3xFlag-tagged protein and performed ChIP-seq against this strain (accession number GSE81073). The sequencing reads from the wild-type (control) sample were subtracted from the experimental sample before ChIP peaks were called (Fig. 1a). Using an arbitrary cut-off of ≥500 sequencing reads we identified 117 enriched target sequences (Supplementary data S1). We confirmed these peaks by visual inspection of the data using Integrated Genome Browser17 and used MEME18 to identify a conserved motif in all 117 ChIP peaks (Fig. 1b). In 14 of the 117 peaks this motif is present as an inverted 11-3-11 bp repeat, which is characteristic of full-length Rrf2 binding sites16,19, and we called these class 1 targets (Fig. 1c). In the other 103 peaks it is present as a single motif or half site and we call these class 2 targets (Fig. 1b). The divergent genes sven3827/8 contain a single class 1 site and the 107 bp intergenic region between sven6562 and rsrR contains two class 1 binding sites separated by a single base pair. It seems likely that RsrR autoregulates and also regulates the divergent sven6562, which encodes a LysR family regulator with an NmrA-type ligand-binding domain. These domains are predicted to sense redox poise by binding NAD(P)+ but not NAD(P)H20. The positions of the two RsrR binding sites relative to the transcript start sites (TSS) of sven6562 and rsrR suggests that RsrR represses transcription of both genes by blocking the RNA polymerase binding site (Supplementary Figure S2). Following investigation of RNA-seq expression data (Supplementary data S1) comparing the wild-type and ∆rsrR strains the only ChIP-seq associated class 1 target with a significantly altered expression profile is sven6562 which is ~5.41-fold (log2) induced by loss of RsrR. We hypothesis that other class 1 targets for which we have RNA-seq data are not significantly affected because they are subject to additional levels of regulation, including perhaps by Sven6562 itself although this remains to be seen.

Figure 1. Defining the regulon and binding site for RsrR.

Top panel (a) shows the whole genome ChIP-seq analysis with class 1 sites labeled in black. The frequency of each base sequenced is plotted with genomic position on the x-axis and frequency of each base sequenced on the y-axis for S. venezualae (NC_018750). Bottom panel (b) shows the class 1 and 2 web logos generated following MEME analysis of the ChIP-seq data.

Other class 1 targets include the nuo (NADH dehydrogenase) operon sven4265-78 (nuoA-N) which contains an internal class 1 site upstream of nuoH, the putative NADP+ dependent dehydrogenase Sven1847 and the quinone oxidoreductase Sven5173 which converts quinone and NAD(P)H to hydroquinone and NAD(P)+ (Table 1). These data suggest a role for RsrR in regulating NAD(P)H metabolism. In addition to the genes involved directly in NADH/NAD(P)H metabolism, class 2 targets include 21 putative transcriptional regulators, genes involved in both primary and secondary metabolism, RNA/DNA replication and modification genes, transporters (mostly small molecule), proteases, amino acid (particularly glutamate and glutamine) metabolism, and a large number of genes with of unknown function (Supplementary data S1).

Table 1. Combined ChIP-Seq and RNA-Seq data for selected RsrR targets.

| Flanking genea |

Distanceb | Dist. TSSc | Fold changee | Annotation | Additional description | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Left (−1) | Right (+1) | |||||

| sven0372d | 7 | −99 | −0.73 | Two-component system histidine kinase | Involved in a two-component system signal transduction set | |

| sven0519d | −993 | 0.53 | Sulfate permease | Involved in sulfate uptake | ||

| sven0772 | −408 | N/A | Xaa-Pro aminopeptidase | Peptidase releasing N-terminal amino acid next to a proline | ||

| sven1561d | 103 | 36 | −0.11 | Glutamine synthase | Carries out the reaction: Glutamate + NH4 −> Glutamine | |

| sven1670 | 17 | −0.28 | Pyridoxamine 5′-phosphate oxidase | Involved in steps of the vitamin B6 metabolism pathway | ||

| sven1686 | −41 | N/A | Citrate lyase beta chain | — | ||

| sven1847d | 6 | −0.89 | 3-oxoacyl-[acyl-carrier protein] reductase | Carries out: NADP+ dependant reduction of 3-oxoacyl-[ACP] | ||

| sven1902 | −1643 | −1689 | −0.03 | Glutamine synthase adenylyltransferase | Regulates glutamine synthase activity by adenylation | |

| sven2494 | 90 | 0 | −1.69 | Hypothetical protein | — | |

| sven2540 | 221 | N/A | Glucose fructose oxidoreductase | D-glucose + D-fructose <> D-gluconolactone + D-glucitol | ||

| sven3087 | 51 | 51 | −0.02 | Acetyltransferase | Transfers an acetyl group | |

| sven3827d | 26 | −10 | 0.15 | SAICAR synthetase | Involved in purine metabolism | |

| sven3934 | 16 | −0.21 | Enhanced intracellular survival protein | — | ||

| sven4022 | −772 | −0.55 | Hypothetical protein | NAD(P)-binding Rossmann-like domain | ||

| sven4273 | 5 | 0.01 | NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase chain I | Involved in the electron transfer chain, binds a [4Fe-4S] | ||

| sven5088 | −77 | −0.15 | Epimerase/dehydratase | NADH dependant isomerase enzyme | ||

| sven5174d | −119 | −0.18 | Quinone oxidoreductase | H2 + menaquinone <>menaquinol | ||

| sven6227 | 73 | −5.21 | NADH-FMN oxidoreductase | FMNH2 + NAD+ <> FMN + NADH + H+ | ||

| sven6534 | −100 | 0.97 | Trypsin-like peptidase domain | A serine protease that hydrolyses proteins | ||

| sven6562d | sven6563d | 72, −35 | 36 | 5.41F, N/A | nmrA/rsrR | DNA binding proteins, NADP/[2Fe-2S] binding |

aGenes flanking the ChIP-seq peak.

bDistance to the translational start codon (bp).

cDistance to the transcriptional start site (bp).

dEMSA reactions have been carried out successfully and specifically on these targets.

eRelative expression (Log2) fold change WT vs. RsrR::apr mutant.

fExpression values defined for targets with >100 mapped reads.

Class 2 targets are highlighted in red.

Purified RsrR contains a redox active [2Fe-2S] cluster

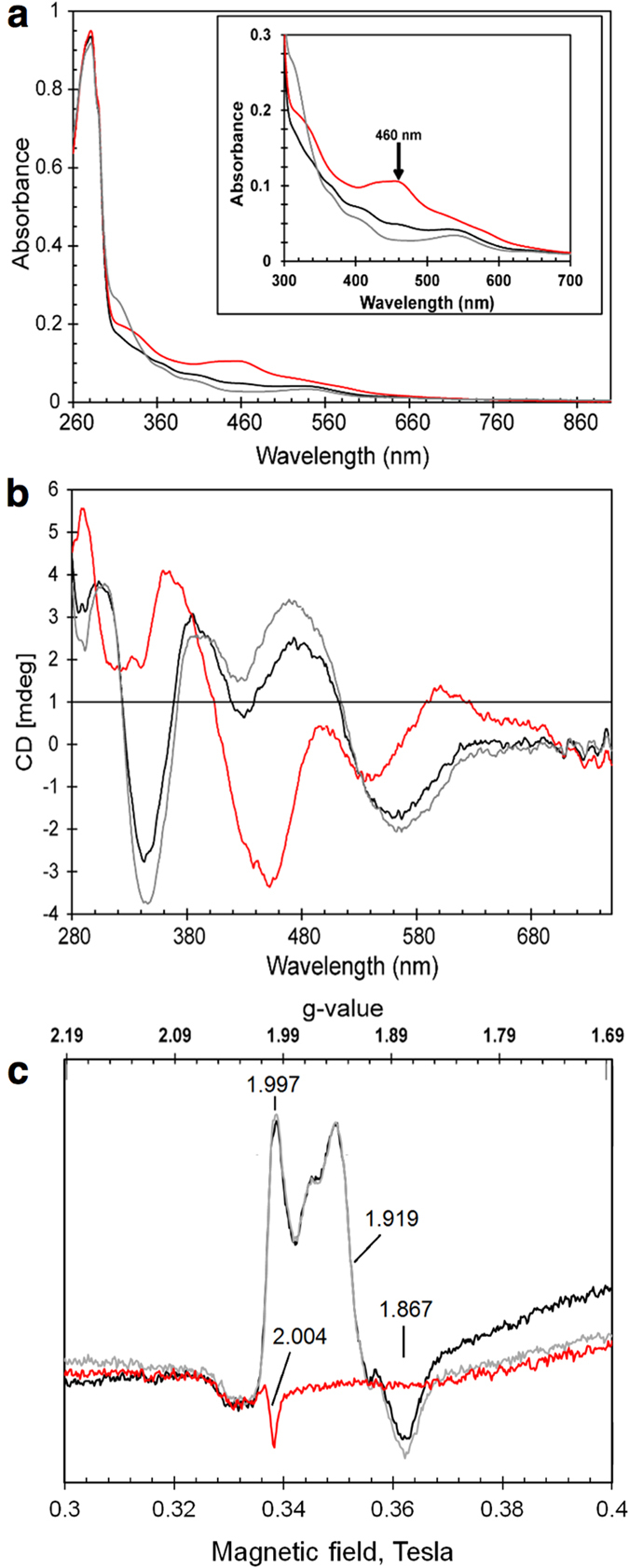

The genes bound by RsrR do not include any NO detoxification genes and this suggested it is not an NsrR homologue but instead has an alternative function. To learn more about the protein we purified it from E. coli under strictly anaerobic conditions. The anaerobic RsrR solution is pink in colour but rapidly turns brown when exposed to O2, suggesting the presence of a redox-active cofactor. Consistent with this, the UV-visible absorbance spectrum of the as-isolated protein revealed broad weak bands in the 300–640 nm region but following exposure to O2, the spectrum changed significantly, with a more intense absorbance band at 460 nm and a pronounced shoulder feature at 330 nm (Fig. 2a). The form of the reduced and oxidized spectra are similar to those previously reported for [2Fe-2S] clusters that are coordinated by three Cys residues and one His21,22. The anaerobic addition of dithionite to the previously air-exposed sample (at a 1:1 ratio with [2Fe-2S] cluster as determined by iron content) resulted in a spectrum very similar to that of the as-isolated protein (Fig. 2a), demonstrating that the cofactor undergoes redox cycling.

Figure 2. Spectroscopic characterization of RsrR.

UV-visible absorption (a), CD (b) and EPR spectra (c) of 309 μM [2Fe-2S] RsrR (~75% cluster-loaded). Black lines – as isolated, red lines – oxidised, grey lines reduced proteins. In (a,b), initial exposure to ambient O2 for 30 min was followed by 309 μM sodium dithionite treatment; in (c) – as isolated protein was first anaerobically reduced by 309 μM sodium dithionite and then exposed to ambient O2 for 50 min. A 1 mm pathlength cuvette was used for optical measurements. Inset in (a) shows details of the iron-sulfur cluster absorbance in the 300–700 nm region.

Because the electronic transitions of iron-sulfur clusters become optically active as a result of the fold of the protein in which they are bound, CD spectra reflect the cluster environment23. The near UV-visible CD spectrum of RsrR (Fig. 2b) for the as-isolated protein contained three positive (+) features at 303, 385 and 473 nm and negative (−) features at 343 and 559 nm. When the protein was exposed to ambient O2 for 30 min, significant changes in the CD spectrum were observed, with features at (+) 290, 365, 500, 600 nm and (−) 320, 450 and 534 nm (Fig. 2b). The CD spectra are similar to those reported for Rieske-type [2Fe-2S] clusters21,24,25, which are coordinated by two Cys and two His residues. Anaerobic addition of dithionite (1 equivalent of [2Fe-2S] cluster) resulted in reduction back to the original form (Fig. 2b) consistent with the stability of the cofactor to redox cycling.

The absorbance data above indicates that the cofactor is in the reduced state in the as-isolated RsrR protein. [2Fe-2S] clusters in their reduced state are paramagnetic (S = ½) and therefore should give rise to an EPR signal. The EPR spectrum for the as-isolated protein contained signals at g = 1.997, 1.919 and 1.867 (Fig. 2c). These g-values and the shape of the spectrum are characteristic of a [2Fe-2S]1+ cluster. The addition of excess sodium dithionite to the as-isolated protein did not cause any changes in the EPR spectrum (Fig. 2c) indicating that the cluster was fully reduced as isolated. Exposure of the as-isolated protein to ambient O2 resulted in an EPR-silent form, with only a small free radical signal typical for background spectra, consistent with the oxidation of the cluster to the [2Fe-2S]2+ form (Fig. 2c), and the same result was obtained upon addition of the oxidant potassium ferricyanide (data not shown).

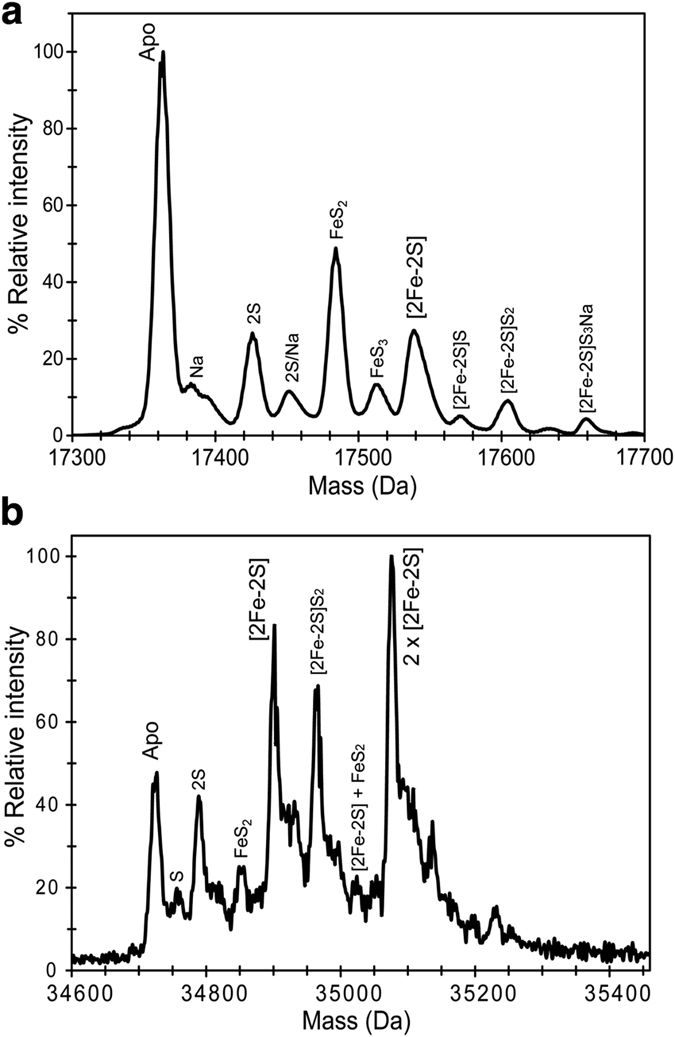

To further establish the cofactor that RsrR binds, native ESI-MS was employed. Here, a C-terminal His-tagged form of the protein was ionized in a volatile aqueous buffered solution that enabled it to remain folded with its cofactor bound. The deconvoluted mass spectrum contained several peaks in regions that corresponded to monomer and dimeric forms of the protein, (Supplementary Figure S3). In the monomer region (Fig. 3a), a peak was observed at 17,363 Da, which corresponds to the apo-protein (predicted mass 17363.99 Da), along with adduct peaks at +23 and +64 Da due to Na+ (commonly observed in native mass spectra) and most likely two additional sulfurs (Cys residues readily pick up additional sulfurs as persulfides, respectively26. A peak was also observed at +176 Da, corresponding to the protein containing a [2Fe-2S] cluster. As for the apo-protein, peaks corresponding to Na+ and sulfur adducts of the cluster species were also observed (Fig. 3a). A significant peak was also detected at +120 Da that corresponds to a break down product of the [2Fe-2S] cluster (from which one iron is missing, FeS2). In the dimer region, the signal to noise is significantly reduced but peaks are still clearly present (Fig. 3b). The peak at 34,726 Da corresponds to the RsrR homodimer (predicted mass 34727.98 Da), and the peak at +352 Da corresponds to the dimer with two [2Fe-2S] clusters. A peak at +176 Da is due to the dimer containing one [2Fe-2S] cluster. A range of cluster breakdown products similar to those detected in the monomer region were also observed (Fig. 3b). Taken together, the data reported here demonstrate that RsrR contains a [2Fe-2S] cluster that can be reversibly cycled between oxidised (+2) and reduced (+1) states.

Figure 3. Native mass spectrometry of RsrR.

(a,b) Positive ion mode ESI-TOF native mass spectrum of ~21 μM [2Fe-2S] RsrR in 250 mM ammonium acetate pH 8.0, in the RsrR monomer (a) and dimer (b) regions. Full m/z spectra were deconvoluted with Bruker Compass Data analysis with the Maximum Entropy plugin.

Cluster and oxidation state dependent binding of RsrR in vitro

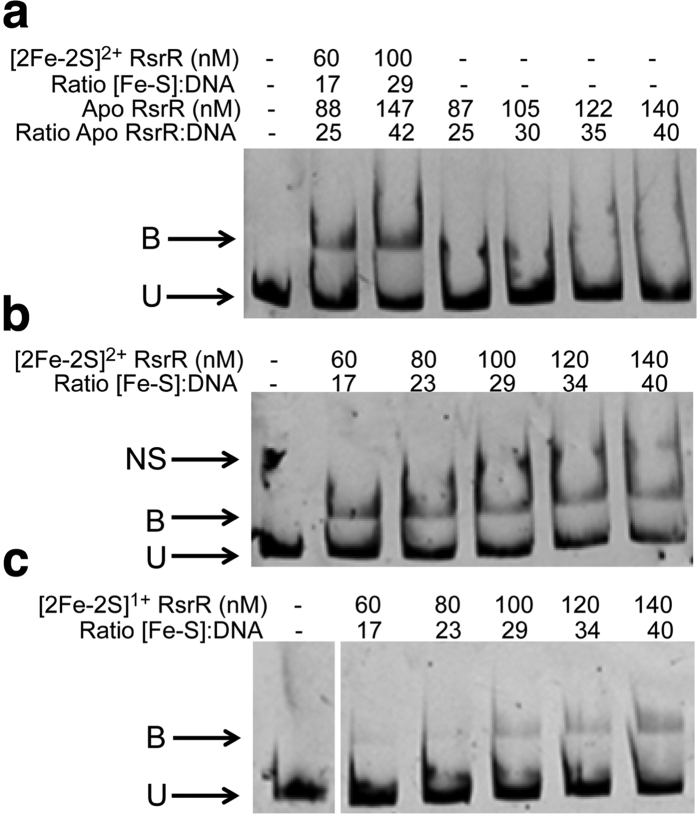

To determine which forms of RsrR are able to bind DNA, we performed EMSA experiments using the intergenic region between the highly enriched ChIP target sven1847/8 as a probe. Increasing ratios of [2Fe-2S] RsrR to DNA resulted in a clear shift in the mobility of the DNA from unbound to bound, see Fig. 4a. Equivalent experiments with cluster-free (apo) RsrR did not result in a mobility shift, demonstrating that the cluster is required for DNA-binding activity. These experiments were performed aerobically and so the [2Fe-2S] cofactor was in its oxidised state. To determine if oxidation state affects DNA binding activity, EMSA experiments were performed with [2Fe-2S]2+ and [2Fe-2S]1+ forms of RsrR. The oxidised cluster was generated by exposure to air and confirmed by UV-visible absorbance. The reduced cluster was obtained by reduction with sodium dithionite, confirmed by UV-visible absorbance, and the reduced state was maintained using EMSA running buffer containing an excess of dithionite. The resulting EMSAs, Fig. 4b,c, show that DNA-binding occurred in both cases but that the oxidised form bound significantly more tightly. Tight binding could be restored to the reduced RsrR samples by allowing it to re-oxidise in air (data not shown). We cannot rule out that the apparent low affinity DNA binding observed for the reduced sample results from partial re-oxidation of the cluster during the electrophoretic experiment. Nevertheless, the conclusion is unaffected: oxidised, [2Fe-2S]2+ RsrR is the high affinity DNA-binding form and these results suggest a change in the redox state of the [2Fe-2S] cluster controls the activity of RsrR, something which has only previously been observed for SoxR, a member of the MerR superfamily27.

Figure 4. Cluster- and oxidation state-dependent DNA binding by [2Fe-2S] RsrR.

EMSAs showing DNA probes unbound (U), bound (B), and non-specifically bound (NS) by (a) [2Fe-2S]2+ and apo-RsrR (b) [2Fe-2S]2+ RsrR and (c) [2Fe-2S]1+ RsrR. Ratios of [2Fe-2S] containing RsrR (Holo) and [RsrR] (apo) to DNA are indicated for (a) while the concentration of [2Fe-2S] RsrR only is reported in (b,c). DNA concentration was 3.5 nM for the [2Fe-2S]2+/1+ and apo-RsrR experiments. For (a,b) the reaction mixtures were separated at 30 mA for 50 min and the polyacrylamide gels were pre-run at 30 mA for 2 min prior to use. For (c) the reaction mixtures were separated at 30 mA for 1 h 45 min and the polyacrylamide gel was pre-run at 30 mA for 50 min prior to use using the de-gassed running buffer containing 5 mM sodium dithionite. For (a) both holo and apo protein concentrations are represented as the sample contained both forms due to incomplete cluster loading. The concentrations reported are of the [2Fe-2S] concentration.

Oxidised [2Fe-2S] RsrR binds strongly to class 1 and 2 binding sites in vitro

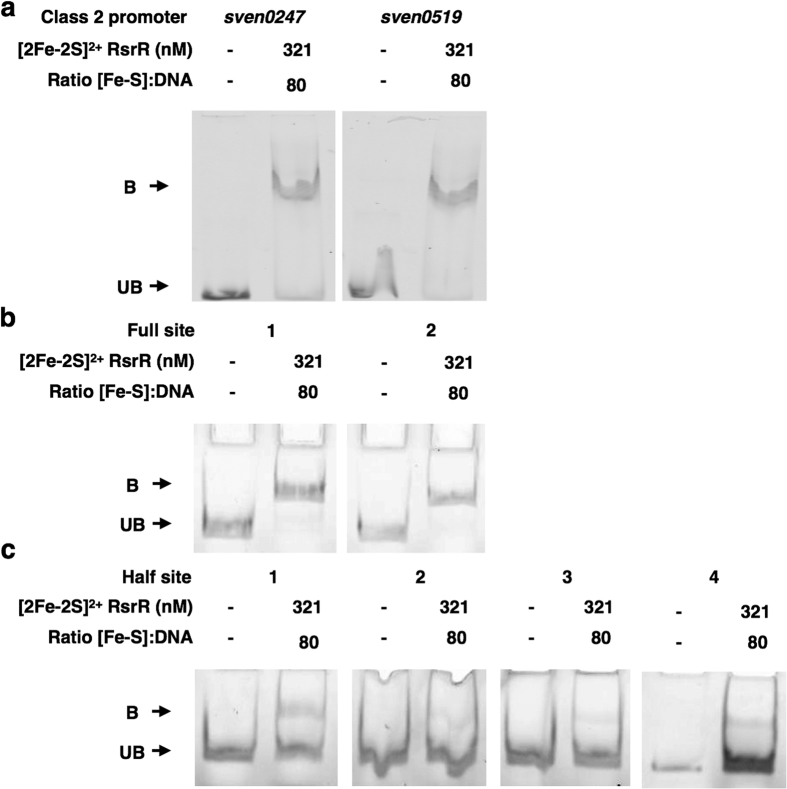

To further investigate the DNA binding activities of [2Fe-2S]2+ RsrR, EMSAs were performed on DNA probes containing the two class 2 RsrR binding sites at sven0247 and sven519 (Fig. 5a). Both probes were shifted by oxidized [2Fe-2S] RsrR showing that RsrR binds to both class 1 and 2 probes in vitro. To further test the idea of RsrR recognizing full and half sites, we constructed a series of probes based on the divergent nmrA-rsrR promoters carrying both or each individual natural class 1 sites (Fig. 5b) and artificial half sites (Fig. 5c). The combinations of artificial half sites are illustrated in Supplemental Figure S3 in regards to the original promoter region. The results show that RsrR binds strongly to both full class 1 binding sites at the nmrA-rsrR promoters (Fig. 5b) but only weakly to artificial half sites (Fig. 5c). This suggests that although MEME only calls half sites in most of the RsrR target genes identified by ChIP-seq these class 2 targets must contain sufficient sequence information in the other half to enable strong binding by RsrR.

Figure 5. Oxidised RsrR binding to full site (class 1) and half site (class 2) RsrR targets.

EMSAs showing DNA probes unbound (U) and bound (B) by [2Fe-2S]2+. Ratios of [2Fe-2S] RsrR and [RsrR] to DNA are indicated. DNA concentration was 4 nM for each probe. EMSA’s using class 2 DNA probes sven0247 and sven0519 (a), class 1 probes from the RsrR rsrR binding region (b) and the four possible half sites from the rsrR class 1 sites (c) were used. For (a) the reaction mixtures were separated at 30 mA for 1 h and the polyacrylamide gel was pre-run at 30 mA for 2 min prior to use. For (b,c) the reaction mixtures were separated at 30 mA for 30 min and the polyacrylamide gels were pre-run at 30 mA for 2 min prior to use. A representation of the rsrR promoter breakdown is also available in Supplementary Figure S3b.

Mapping RsrR binding sites in vivo using ChIP-exo and differential RNA-seq

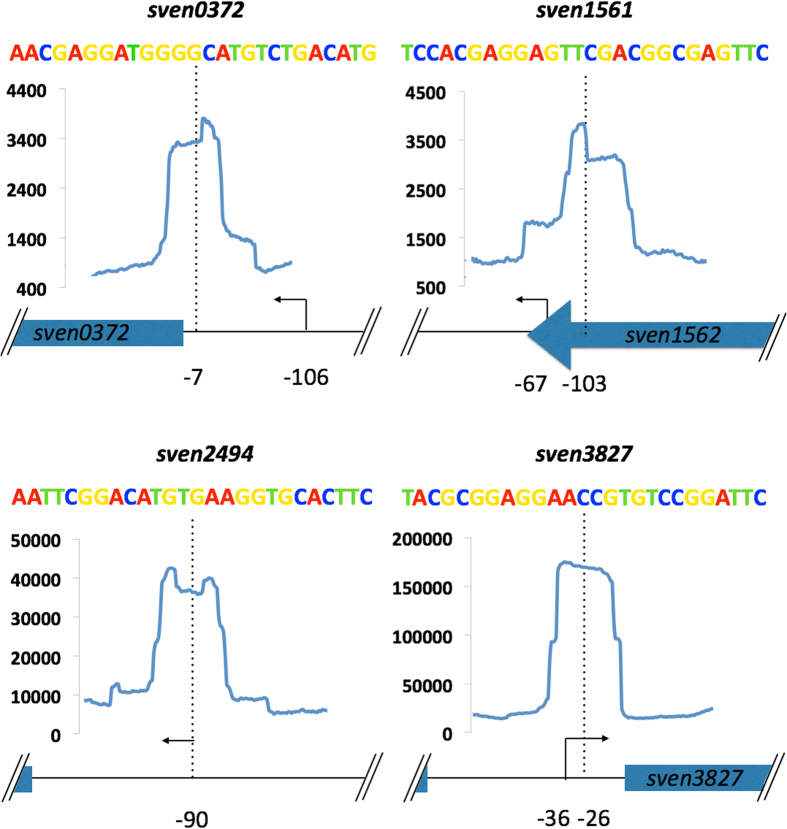

MEME analysis of the ChIP-seq data detected only 14 class 1 (11-3-11 bp inverted repeat) sites out of the 117 target sites bound by RsrR on the S. venezuelae chromosome. However, ChIP-Seq and EMSAs show that RsrR can bind to target genes whether they contain class 1 or class 2 sites. This differs from E. coli NsrR which binds only weakly to target sites containing putative half sites (class 2)28. To gain more information about RsrR recognition sequences and the positions of these binding sites at target promoters we combined differential RNA-seq (dRNA-seq, accession number GSE81104), which maps the start sites of all expressed transcripts, with ChIP-exo (accession number GSE80818) which uses Lambda exonuclease to trim excess DNA away from ChIP complexes leaving only the DNA which is actually bound and protected by RsrR. For dRNA-seq, total RNA was prepared from cultures of wild type S. venezuelae and for the ∆rsrR mutant grown for 16 hours. ChIP-exo was performed on the ∆rsrR strain producing Flag-tagged RsrR, also at 16 hours. ChIP-exo identified 630 binding sites which included the 117 targets identified previously using ChIP-seq. The ChIP-exo peaks are on average only ~50 bp wide giving much better resolution of the RsrR binding sites at each target. MEME analysis using all 630 ChIP-exo sequences identified the class 2 binding motif in every sequence and we identified transcript start sites (TSS) for 261 of the 630 RsrR target genes using our dRNA-seq data (Supplementary data S1). Figure 6 shows a graphical representation of class 1 targets that have clearly defined TSS, indicating the centre of the ChIP peak, the associated TSS and any genes within the ~200 bp frame. Based on the RsrR binding site position at putative target genes RsrR likely acts as both a transcriptional activator and repressor and we have shown that RsrR represses transcription of sven6562 which is a class 1 target with two 11-3-11 bp binding site in the intergenic region between sven6562 and rsrR. The functional significance of RsrR binding to the other class 1 and 2 target genes identified here by ChIP-seq and ChIP-exo remains to be seen but they are not significantly affected by loss of RsrR under the conditions used in our experiments.

Figure 6. Graphical representation of combined ChIP-Seq, ChIP-exo and dRNA-seq for four class 1 targets.

Each target has the relative position of ChIP-exo (blue line) peak centre (dotted line) and putative transcriptional start site (TSS - solid arrow) indicated with the distance in bp (black numbers) relative to the down stream start codon of target genes. The y-axis scale corresponds to number of reads for ChIP data with each window corresponding to 200 bp with each ChIP-peak being ~50 bp wide. Above each is the relative binding site sequence coloured following the weblogo scheme (A – red, T – green, C – blue and G – yellow) from the MEME results.

Discussion

In this work we have identified and characterized a new member of the Rrf2 protein family, which was mis-annotated as an NsrR homologue in the S. venezuelae genome. ChIP analyses show that RsrR binds to 630 sites on the S. venezuelae genome which compares to just three target sites for S. coelicolor NsrR and their DNA recognition sequences are very different. RNA-seq data shows a dramatic 5.3 fold (log2) change in the expression of the divergent gene from rsrR, sven6562, but under normal laboratory conditions no other direct RsrR targets are significantly induced or repressed by loss of RsrR. Approximately 2.7% of the RsrR targets contain class 1 binding sites which consist of a MEME identified 11-3-11 bp inverted repeat. Class 1 target genes include sven6562 and are involved in either signal transduction and/or NAD(P)H metabolism which perhaps points to a link to redox poise and recycling of NAD(P)H to NAD(P) in vivo. The >600 class 2 target genes contain only half sites with a single repeat but exhibit strong binding by RsrR in vitro. Our EMSA experiments show that RsrR binds weakly to artificial half sites and this suggests additional sequence information is present at class 2 binding sites that increases the strength of DNA binding by RsrR. Six of the class 2 targets are involved in glutamate and glutamine metabolism including: sven1561, encoding a Glutamine Synthase (GS) that carries out the ATP dependent conversion of glutamate and ammonium to glutamine29, sven1902, encoding a GS adenylyltransferase that carries out the adenylation and deadenylation of GS, reducing or increasing GS activity respectively30. sven3711, encoding a protein which results in the liberation of glutamate from glutamine31. sven4418, encoding a glutamine fructose-6-phosphate transaminase that carries out the reaction: L-glutamine and D-fructose 6-phosphate to L-glutamate and D-glucosamine 6-phosphate32. sven4888, encoding a glutamate-1-semialdehyde aminotransferase, which carries out the PLP dependent, reversible reaction of L-glutamate to 1-semialdehyde 5-aminolevulinate33. Finally, sven7195, encoding a glutamine-dependent asparagine synthase which carries out the ATP dependent transfer of NH3 from glutamine to aspartate, forming glutamate and asparagine34. Glutamate and glutamine are precursors for the production of mycothiol, the actinobacterial equivalent of glutathione, which acts as a cellular reducing agent. Mycothiol also acts as a cellular reserve of cysteine and in the detoxification of redox species and antibiotics35. Glutamate is important, as a non-essential amino acid, because it links nitrogen and carbon metabolism in bacteria36. Additionally, glutamate acts as a proton sink through its decarboxylation to GABA, which especially under acidic conditions, favorably removes protons from the intracellular milieu37.

Our data show that the purified RsrR protein contains a [2Fe-2S] cluster, which is stable in the presence of O2 and can be reversibly cycled between reduced (+1) and oxidized (+2) states. The oxidised [2Fe-2S]2+ form binds strongly to both class 1 and class 2 binding sequences in vitro, whereas the reduced [2Fe-2S]1+ form exhibits significantly weaker binding. The binding we did observed is likely due to partial oxidation of the RsrR Fe-S cluster during the EMSA electrophoresis. The cluster free form of RsrR does not bind to DNA at all. Given these observations and the stability of the Fe-S cluster to aerobic conditions, we propose that the activity of RsrR is modulated by the oxidation state of its cluster, becoming activated for DNA binding through oxidation and inactivated through reduction. Exposure to O2 is sufficient to cause oxidation, but other oxidants may also be important in vivo. The properties of RsrR described here are reminiscent of the E. coli [2Fe-2S] cluster containing transcription factor SoxR, which controls the regulation of another regulator, SoxS, through the oxidation state of its cluster38.

Due to the number of RsrR regulated transcription factors it is likely that its target genes are subject to multiple levels of regulation. For example, the sven6562 gene, which is divergent from rsrR, encodes a LysR family regulator with an N terminal NmrA-type NAD(P)+ binding domain. NmrA proteins are thought to control redox poise in fungi by sensing the levels of NAD(P), which they can bind, and NAD(P)H, which they cannot39. This is intriguing and we propose a model in which reduction of holo-RsrR induces expression of Sven6562 which in turn senses redox poise via the ratio of NAD(P)+/NAD(P)H/NAD(P)H and then modulates expression of its own regulon which likely overlaps with that of RsrR. Clearly there is much to learn about this system and it will be important to define the role of Sven6562 in S. venezuelae in the future. We did not observe any phenotype for the ∆rsrR mutant and it is no more sensitive to redox active compounds or oxidative stress than wild-type S. venezuelae (not shown). However, this is not surprising given the number of systems in bacteria that deal with reactive nitrogen and oxygen species and redox stress. In Streptomyces species these include catalases, peroxidases40 and superoxide dismutases41 and associated regulators such as OxyR42, SigR43, OhrR44, Rex20 and SoxR45. Thus, our data suggests Sven6563, tentatively renamed here as RsrR, is a new member of the Rrf2 family and this work extends our knowledge about this neglected but widespread superfamily of bacterial transcription factors.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial strains, plasmids, oligonucleotides and growth conditions

Bacterial strains and plasmids are listed in Table 2 and oligonucleotides are listed in Table 3. For ChIP-seq experiments, S. venezuelae strains were grown at 30 °C in MYM liquid sporulation medium46 made with 50% tap water and supplemented with 200 μl trace element solution47 per 100 ml and adjusted to a final pH of 7.3. Disruption of rsrR was carried out following the PCR-targeting method48 as described previously49,50. Primers JM0109 and JM0110 were used to PCR amplify the apramycin disruption cassette from pIJ773. Cosmid SV-5-F05 was used as the template cosmid. The disruption cosmid (pJM026) was checked by PCR using primers JM0111 and JM0112. Antibiotic marked, double crossover exconjugants, were identified as previously described and confirmed once more with JM0111 and JM0112. The 3x Flag tag copy of rsrR was synthesized by Genescript and subcloned into pMS82 using HindIII/KpnI and confirmed by PCR using primers JM0113 and JM0114.

Table 2. Strains and plasmids used during this study.

| Strain/plasmid | Description | Source |

|---|---|---|

|

E. coli | ||

| TOP10 | F- mcrA Δ(mrr-hsdRMS-mcrBC) φ80lacZΔM15 ΔlacX74 nupG recA1 araD139 Δ(ara-leu)7697 galE15 galK16 rpsL(StrR) endA1 λ− | Invitrogen |

| BW25113 (pIJ790) | E. coli BW25113 containing λRED recombination plasmid pIJ790 | 48,58 |

| ET12567 (pUZ8002) | E. coli Δdam dcm strain containing helper plasmid pUZ8002 | 59,60 |

| BL21 | F− ompT gal dcm lon hsdSB(rB− mB−) λ(DE3 [lacI lacUV5-T7 gene 1 ind1 sam7 nin5]) | 61 |

| Streptomyces | ||

| S. venezualae | S. venezuelae ATCC 10712 WT strain | 4 |

| rsrR::apr | S. venezuelae with a ReDirect disrupted sven6563::apr | |

| rsrR::apr 3xFlag RsrR | rsrR::apr with a pMS82 encoded N-terminal 3xFlag tagged rsrR with 300 bp of upstream flanking DNA (promoter) | This work |

| Plasmids | ||

| pIJ773 | pBluescript KS (+), aac(3)IV, oriT (RK2), FRT sites | 48 |

| SV-5-F05 | Supercos-1-cosmid with (a 52181 bp) fragment containing sven6562/3 | 4 |

| pMS82 | ori, pUC18, hyg, oriT, RK2, int ΦBT1 | 62 |

| pGS-21a | Genscript overexpression and purification vector (SD0121) | Genscript |

| pJM026 | SV-5-F05 containing sven6563::apr oriT | This work |

| pJM027 | pMS82, rsrR gene plus 300 bp upstream DNA with a c-terminal synthetic linker and 3xFLAG tag | This work |

| pJM028 | pGS-21a, full length rsrR cloned NdeI/XhoI | This work |

| pJM029 | pJM028 with a c-terminal 6xHis tag NdeI/XhoI | This work |

| pJM030 | pJM028 with a c-terminal synthetic linker as with (flag), 2xFLAG tag and a 6xHis tag, cloned NdeI/XhoI | This work |

Table 3. List of primers used in this study.

| Name | Description | Sequence |

|---|---|---|

| JM0062 | M13_Fwd sequence labelled with 6′Fam for EMSA reactions using M13Fam nested primers | CTAAAACGACGGCCAGT |

| JM0063 | M13_Rev sequence labelled with 6′Fam for EMSA reactions using M13Fam nested primers | CAGGAAACAGCTATGAC |

| JM0109 | RsrR (sven6563) forward disruption primer (Redirect) | CCAGTCCCCTCCCCCACGGACCTGCTGCGTCGCACCATGATTCCGGGGATCCGTCGACC |

| JM0110 | RsrR (sven6563) reverse disruption primer (Redirect) | CACCGAACAGCCAAGCCCCCCTCAGCAAGCCCTCCCTCATGTAGGCTGGAGCTGCTTC |

| JM0111 | RsrR (sven6563) forward test primer | ACGCGGCGACCACGTCGTGG |

| JM0112 | RsrR (sven6563) reverse test primer | GCCCGTACGGTAGACCGCCG |

| JM0113 | pMS82 cloning forward test primer | GCAACAGTGCCGTTGATCGTGCTATG |

| JM0114 | pMS82 cloning reverse test primer | GCCAGTGGTATTTATGTCAACACCGCC |

| JM0117 | M13Fam nested sven1847 for primer sequence for EMSA reactions | CTAAAACGACGGCCAGTTCTCCTCGCCCGCCCCGTCG |

| JM0118 | M13Fam nested sven1847 rev primer sequence for EMSA reactions | CAGGAAACAGCTATGACCCGTCCGGCGCCCCGGGTGG |

| JM0119 | M13Fam nested sven3827 for primer sequence for EMSA reactions | CTAAAACGACGGCCAGTCTCGCCCACTCGCCGTACCG |

| JM0120 | M13Fam nested sven3827 rev primer sequence for EMSA reactions | CAGGAAACAGCTATGACCATCACGAGATCGCCCGCCT |

| JM0121 | M13Fam nested sven4273 for primer sequence for EMSA reactions | CTAAAACGACGGCCAGTGAGAACATCGCCTTCGGCAA |

| JM0122 | M13Fam nested sven4273 rev primer sequence for EMSA reactions | CAGGAAACAGCTATGACGCGGGGCGCCGTCGTCTTCT |

| JM0123 | M13Fam nested sven5174 for primer sequence for EMSA reactions | CTAAAACGACGGCCAGTCGCGTTCCGGACCCGTACAAAGAAT |

| JM0124 | M13Fam nested sven5174 rev primer sequence for EMSA reactions | CAGGAAACAGCTATGACACCTGAATCTCGCATGACCCTCCGA |

| JM0125 | M13Fam nested sven0372 for primer sequence for EMSA reactions | CTAAAACGACGGCCAGTTGGTGACCGGGTCCGAACGGTCCGTAA |

| JM0126 | M13Fam nested sven0372 rev primer sequence for EMSA reactions | CAGGAAACAGCTATGACAACAGGGAGAGCTGGTCGACCATCC |

| JM0127 | M13Fam nested sven1561 for primer sequence for EMSA reactions | CTAAAACGACGGCCAGTCCCAGCTACGAGGTGGCGAAGCAGG |

| JM0128 | M13Fam nested sven1561 rev primer sequence for EMSA reactions | CAGGAAACAGCTATGACGGTCTGGGTGTCGAAGAAGGTGGTG |

| JM0129 | M13Fam nested sven6563 for primer sequence for EMSA reactions | CTAAAACGACGGCCAGTTCGTCGAAGGTCGGGGAGTT |

| JM0130 | M13Fam nested sven6563 rev primer sequence for EMSA reactions | CAGGAAACAGCTATGACCGTGCAGCTCAGCGAGCCGG |

| JM0131 | M13Fam nested sven0247 for primer sequence for EMSA reactions | CTAAAACGACGGCCAGTTCGTCATGATCGTGTGGCGGCTGCG |

| JM0132 | M13Fam nested sven0247 rev primer sequence for EMSA reactions | CAGGAAACAGCTATGACAGCACCAGCCGCTCGTCGAACGCGG |

| JM0133 | M13Fam nested sven0519 for primer sequence for EMSA reactions | CTAAAACGACGGCCAGTAGACGATGATCAACGTGAAGGTGTCCG |

| JM0134 | M13Fam nested sven0519 rev primer sequence for EMSA reactions | CAGGAAACAGCTATGACAAGGTCGCGACGCACACCATGATCAT |

| JM0141 | M13Fam nested sven6562/3 Site 1-4 primer sequence for EMSA reactions | CTAAAACGACGGCCAGTCAAACTCGGATACCCGATGTCCGAGATAATACTCGGATAGTCTGTGTCCGAGTCAAGTCATAGCTGTTTCCTG |

| JM0142 | M13Fam nested sven6562/3 Site 1-2 primer sequence for EMSA reactions | CTAAAACGACGGCCAGTGCAAACTCGGATACCCGATGTCCGAGATAATGTCATAGCTGTTTCCTG |

| JM0143 | M13Fam nested sven6562/3 Site 3-4 primer sequence for EMSA reactions | CTAAAACGACGGCCAGTTAATACTCGGATAGTCTGTGTCCGAGTCAAAGTCATAGCTGTTTCCTG |

| JM0144 | M13Fam nested sven6562/3 Site 1 primer sequence for EMSA reactions | CTAAAACGACGGCCAGTGCAAACTCGGATACCCGGTCATAGCTGTTTCCTG |

| JM0145 | M13Fam nested sven6562/3 Site 2 primer sequence for EMSA reactions | CTAAAACGACGGCCAGTCCGATGTCCGAGATAATGTCATAGCTGTTTCCTG |

| JM0146 | M13Fam nested sven6562/3 Site 3 primer sequence for EMSA reactions | CTAAAACGACGGCCAGTTAATACTCGGATAGTCTGTCATAGCTGTTTCCTG |

| JM0147 | M13Fam nested sven6562/3 Site 4 primer sequence for EMSA reactions | CTAAAACGACGGCCAGTTCTGTGTCCGAGTCAAAGTCATAGCTGTTTCCTG |

Primers JM0119-JM0134 were used to produce EMSA DNA templates that were successfully shifted using purified RsrR and mentioned in the text but the data is not shown as part of the work.

ChIP (chromatin immunoprecipitation) – seq and exo

ChIP-Seq was carried out as previously described51 with the below modifications. A 3xFlag tagged RsrR was used as with our previous work11. Following sonication and lysate clearing M2 affinity beads (Sigma-Aldrich #A2220) were prepared by washing in ½IP buffer following manufacturers instructions. The cleared lysate was incubated with 40 μl of washed M2 beads and incubated for 4 h at 4C in a vertical rotor. The lysate was removed and the beads pooled into one 1.5 microfuge tube and washed in 0.5 IP buffer. The beads were transferred to a fresh microfuge tube and washed a further 3 times removing as much buffer as possible without disturbing the beads. The DNA-protein complex was eluted from the beads with 100 μl elution buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH7.6, 10 mM EDTA, 1% SDS) by incubating at 65 °C overnight. Removing the ~100 μl elution buffer, an extra 50 μl of elution buffer was added and further incubated at 65 °C for 5 min. To extract the DNA 150 μl eluate, 2 μl proteinase K (10 mg/ml) was added and incubated 1.5 h at 55 °C. To the reaction 150 μl phenol-chloroform was added. Samples were vortexed and centrifuged at full speed for 10 min. The aqueous layer was extracted and purified using the Qiaquick column from Qiagen with a final elution using 50 μl EB buffer (Qiagen). The concentration of samples were determined using Quant-iT™ PicoGreen® dsDNA Reagent (Invitrogen) or equivalent kit or by nanodrop measurement. DNA sequencing of ChIP-Seq samples was carried out by GATC Biotech. ChIP-exo following sonication of lysates was carried out by Peconic LLC (State College, PA) adding an additional exonuclease treatment to the process as previously described52. Data analysis was carried out using CLC workbench 8 followed by a manual visual inspection of the data.

dRNA - seq

Mycelium was harvested at experimentally appropriate time points and immediately transferred to 2 ml round bottom tubes, flash frozen in liquid N2, stored at −80 °C or used immediately. All apparatus used was treated with RNaseZAP (Sigma) to remove RNases for a minimum of 1 h before use. RNaseZAP treated mortar and pestles were used, the pestle being placed and cooled on a mixture of dry ice and liquid N2 with liquid N2 being poured into the bowl and over the mortar. Once the bowl had cooled the mycelium samples were added directly to the liquid N2 and thoroughly crushed using the mortar leaving a fine powder of mycelium. Grindings were transferred to a pre-cooled 50 ml Falcon tube and stored on dry ice. Directly to the tube, 2 ml of TRI reagent (Sigma) was added to the grindings and mixed. Samples are then thawed while vortexing intermittently at room temperature for 5–10 min until the solution cleared. To 1 ml of TRI reagent resuspension, 200 μl of chloroform was added and vortexed for 15 seconds at room temperature then centrifuged for 10 min at 13,000 rpm. The upper, aqueous phase (clear colourless layer) was removed into a new 2 ml tube. The remainder of the isolation protocol follows the RNeazy Mini Kit (Qiagen) instructions carrying out both on and off column DNase treatments. On column treatments were carried out following the first RW1 column wash. DNaseI (Qiagen) was added (10 μl enzyme, 70 μl RDD buffer) to the column and stored at RT for 1 h. The column was washed again with RW1 then treated as described in the manufacturer’s instructions. Once eluted from the column, samples were treated using TURBO DNA-free Kit (Ambion) following manufacturer’s instructions to remove residual DNA contamination.

RNA-seq was carried out by vertis Biotechnologie. Data analysis was carried out using the Tuxedo protocol53 for analysis of gene expression and TSSAR webservice for dRNA transcription start site analysis54. In addition a manual visual processing approach was carried out for each.

Purification of RsrR

L Luria-Bertani medium (10 × 500 mL) was inoculated with freshly transformed BL21 (DE3) E. coli containing a pGS-21a vector with the prsrR-His insert. 100 μg/mL ampicillin and 20 μM ammonium ferric citrate were added and the cultures were grown at 37 °C, 200 rpm until OD600 nm was 0.6–0.9. To facilitate in vivo iron-sulfur cluster formation, the flasks were placed on ice for 18 min, then induced with 100 μM IPTG and incubated at 30 °C and 105 rpm. After 50 min, the cultures were supplemented with 200 μM ammonium ferric citrate and 25 μM L-Methionine and incubated for a further 3.5 h at 30 °C. The cells were harvested by centrifugation at 10000 × g for 15 min at 4 °C. Unless otherwise stated, all subsequent purification steps were performed under anaerobic conditions inside an anaerobic cabinet (O2 < 2 ppm). Cells pellets were resuspended in 70 mL of buffer A (50 mM TRIS, 50 mM CaCl2, 5% (v/v) glycerol, pH 8) and placed in a 100 mL beaker. 30 mg/mL of lysozyme and 30 mg/mL of PMSF were added and the cell suspension thoroughly homogenized by syringe, removed from the anaerobic cabinet, sonicated twice while on ice, and returned to the anaerobic cabinet. The cell suspension was transferred to O-ring sealed centrifuge tubes (Nalgene) and centrifuged outside of the cabinet at 40,000 × g for 45 min at 1 °C.

The supernatant was passed through a HiTrap IMAC HP (1 × 5 mL; GE Healthcare) column using an ÄKTA Prime system at 1 mL/min. The column was washed with Buffer A until A280 nm < 0.1. Bound proteins were eluted using a 100 mL linear gradient from 0 to 100% Buffer B (50 mM TRIS, 100 mM CaCl2, 200 mM L- Cysteine, 5% glycerol, pH 8). A HiTrap Heparin (1 × 1 mL; GE Healthcare) column was used to remove the L- Cysteine, using buffer C (50 mM TRIS, 2 M NaCl, 5% glycerol, pH 8) to elute the protein. Fractions containing RsrR-His were pooled and stored in an anaerobic freezer until needed. RsrR-His protein concentrations were determined using the method of Bradford (Bio-Rad Laboratories)55, with BSA as the standard. Cluster concentrations were determined by iron assay56, from which an extinction coefficient, ε, at 455 nm was determined as 3450 ± 25 M−1 cm−1, consistent with values reported for [2Fe-2S] clusters with His coordination21.

Preparation of Apo- RsrR

Apo-RsrR -His was prepared from as isolated holoprotein by aerobic incubation with 1 mM EDTA overnight.

Spectroscopy and mass spectrometry

UV-visible absorbance measurements were performed using a Jasco V500 spectrometer, and CD spectra were measured with a Jasco J810 spectropolarimeter. EPR measurements were performed at 10 K using a Bruker EMX EPR spectrometer (X-band) equipped with a liquid helium system (Oxford Instruments). Spin concentrations in the protein samples were estimated by double integration of EPR spectra with reference to a 1 mM Cu(II) in 10 mM EDTA standard. For native MS analysis, His-tagged RsrR was exchanged into 250 mM ammonium acetate, pH 8, using PD10 desalting columns (GE Life Sciences), diluted to ~21 μM cluster and infused directly (0.3 mL/h) into the ESI source of a Bruker micrOTOF-QIII mass spectrometer (Bruker Daltonics, Coventry, UK) operating in the positive ion mode. Full mass spectra (m/z 700–3500) were recorded for 5 min. Spectra were combined, processed using the ESI Compass version 1.3 Maximum Entropy deconvolution routine in Bruker Compass Data analysis version 4.1 (Bruker Daltonik, Bremen, Germany). The mass spectrometer was calibrated with ESI-L low concentration tuning mix in the positive ion mode (Agilent Technologies, San Diego, CA).

Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assays (EMSAs)

DNA fragments carrying the intergenic region between sven1847 and sven1848 of the S. venezualae chromosome were PCR amplified using S. venezualae genomic DNA with 5′ 6-FAM modified primers (Table 2). The PCR products were extracted and purified using a QIAquick gel extraction kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Probes were quantitated using a NanoDrop ND2000c. The molecular weights of the double stranded FAM labelled probes were calculated using OligoCalc57.

EMSA reactions (20 μl) were carried out on ice in 10 mM Tris, 60 mM KCl, pH 7.52. Briefly, 1 μL of DNA was titrated with varying aliquots of RsrR. 2 μL of loading dye (containing 0.01% (w/v) bromophenol blue), was added and the reaction mixtures were immediately separated at 30 mA on a 5% (w/v) polyacrylamide gel in 1 X TBE (89 mM Tris,89 mM boric acid, 2 mM EDTA), using a Mini Protean III system (Bio-Rad). Gels were visualized (excitation, 488 nm; emission, 530 nm) on a molecular imager FX Pro (Bio-Rad). Polyacrylamide gels were pre-run at 30 mA for 2 min prior to use. For investigations of [2Fe-2S]1+ RsrR DNA binding, in order to maintain the cluster in the reduced state, 5 mM of sodium dithionite was added to the isolated protein and the running buffer (de-gassed for 50 min prior to running the gel). Analysis by UV-visible spectroscopy confirmed that the cluster remained reduced under these conditions.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Munnoch, J. T. et al. Characterization of a putative NsrR homologue in Streptomyces venezuelae reveals a new member of the Rrf2 superfamily. Sci. Rep. 6, 31597; doi: 10.1038/srep31597 (2016).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the Natural Environment Research Council for a PhD studentship to John Munnoch, to the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council for the award of grant BB/J003247/1 (to NLB and MIH), to the UEA Science Faculty for a PhD studentship to Maria Teresa Pellicer Martinez. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication. We are grateful to Dr Govind Chandra at the John Innes Centre for advice about ChIP- and dRNA-seq data analysis and to UEA for supporting the mass spectrometry facility. The research presented in this paper was carried out on the High Performance Computing Cluster supported by the Research and Specialist Computing Support service at the University of East Anglia. All sequence data was deposited online with the Geo superSeries accession number GSE81105 (ChIP-Seq, ChP-exo and dRNA-seq all at a 16 h time point with accession numbers GSE81073, GSE80818, and GSE81104 respectively).

Footnotes

Author Contributions J.T.M. carried out all of the molecular microbiology experiments, some of the biochemical experiments, analysed the data and co-wrote the manuscript. M.T.P.C. carried out the bulk of the biochemical experiments, analysed the data and co-wrote the manuscript. J.C.C. analyzed data and co-wrote the manuscript. D.A.S. performed EPR experiments and analysed data. N.E.L.B. and M.I.H. conceived and coordinated the study, analyzed data and co-wrote the manuscript.

References

- Newman D. J. & Cragg G. M. Natural products as sources of new drugs over the 30 years from 1981 to 2010. J. Nat. Prod. 75, 311–335 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Challis G. L. & Hopwood D. a. Synergy and contingency as driving forces for the evolution of multiple secondary metabolite production by Streptomyces species. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100, 14555–14561 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glazebrook M. a, Doull J. L., Stuttard C. & Vining L. C. Sporulation of Streptomyces venezuelae in submerged cultures. J. Gen. Microbiol. 136, 581–588 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pullan S. T., Chandra G., Bibb M. J. & Merrick M. Genome-wide analysis of the role of GlnR in Streptomyces venezuelae provides new insights into global nitrogen regulation in actinomycetes. BMC Genomics 12, 175 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flärdh K. & Buttner M. J. Streptomyces morphogenetics: dissecting differentiation in a filamentous bacterium. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 7, 36–49 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez H., Rico S., Díaz M. & Santamaría R. I. Two-component systems in Streptomyces: key regulators of antibiotic complex pathways. Microb. Cell Fact. 12, 127 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Keulen G., Alderson J., White J. & Sawers R. G. The obligate aerobic actinomycete Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) survives extended periods of anaerobic stress. Environ. Microbiol. 9, 3143–3149 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson E. G. et al. Plant-pathogenic Streptomyces species produce nitric oxide synthase-derived nitric oxide in response to host signals. Chem. Biol. 15, 43–50 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki Y. et al. Nitrogen oxide cycle regulates nitric oxide levels and bacterial cell signaling. Sci. Rep. 6, 22038 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crack J. C. et al. Differentiated, promoter-specific response of [4Fe-4S] NsrR DNA-binding to reaction with nitric oxide. J. Biol. Chem. 291, 8663–8672 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crack J. et al. NsrR from Streptomyces coelicolor is a Nitric Oxide-Sensing [4Fe-4S] Cluster Protein with a Specialized Regulatory Function. J. Biol. Chem. 290, 12689–12704 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner P. R. et al. Hemoglobins dioxygenate nitric oxide with high fidelity. J. Inorg. Biochem. 100, 542–550 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poole R. K. & Hughes M. N. New functions for the ancient globin family: Bacterial responses to nitric oxide and nitrosative stress. Mol. Microbiol. 36, 775–783 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forrester M. T. & Foster M. W. Protection from nitrosative stress: a central role for microbial flavohemoglobin. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 52, 1620–1633 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibbing M. E. & Fuqua C. Antiparallel and interlinked control of cellular iron levels by the Irr and RirA regulators of Agrobacterium tumefaciens. J. Bacteriol. 193, 3461–3472 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos J. a., Pereira P. J. B. & Macedo-Ribeiro S. What a difference a cluster makes: The multifaceted roles of IscR in gene regulation and DNA recognition. Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Proteins Proteomics 1–12, doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2015.01.010 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicol J. W., Helt G. A., Blanchard S. G., Raja A. & Loraine A. E. The Integrated Genome Browser: Free software for distribution and exploration of genome-scale datasets. Bioinformatics 25, 2730–2731 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey T. L. et al. MEME SUITE: tools for motif discovery and searching. Nucleic Acids Res. 37, W202–W208 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Partridge J. D., Bodenmiller D. M., Humphrys M. S. & Spiro S. NsrR targets in the Escherichia coli genome: New insights into DNA sequence requirements for binding and a role for NsrR in the regulation of motility. Mol. Microbiol. 73, 680–694 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brekasis D. & Paget M. S. B. A novel sensor of NADH/NAD+ redox poise in Streptomyces coelicolor A3 (2). EMBO J. 22, 4856–4865 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura S., Kikuchi A., Senda T., Shiro Y. & Fukuda M. Tolerance of the Rieske-type [2Fe-2S] cluster in recombinant ferredoxin BphA3 from Pseudomonas sp. KKS102 to histidine ligand mutations. Biochem. J. 388, 869–878 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin J., Zhou T., Ye K. & Wang J. Crystal structure of human mitoNEET reveals distinct groups of iron sulfur proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104, 14640–14645 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens P. J. et al. Circular dichroism and magnetic circular dichroism of iron-sulfur proteins. Biochemistry 17, 4770–4778 (1978). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link T. A. et al. Comparison of the ‘Rieske’ [2Fe-2S] center in the bc1 complex and in bacterial dioxygenases by circular dichroism spectroscopy and cyclic voltammetry. Biochemistry 35, 7546–7552 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couture M. M. J. et al. Characterization of BphF, a Rieske-type ferredoxin with a low reduction potential. Biochemistry 40, 84–92 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang B. et al. Reversible cycling between cysteine persulfide-ligated [2Fe-2S] and cysteine-ligated [4Fe-4S] clusters in the FNR regulatory protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 109, 15734–15739 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujikawa M., Kobayashi K. & Kozawa T. Direct oxidation of the [2Fe-2S] cluster in SoxR protein by superoxide: Distinct differential sensitivity to superoxide-mediated signal transduction. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 35702–35708 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chhabra S. & Spiro S. Inefficient translation of nsrR constrains behavior of the NsrR regulon in Escherichia coli. Microbiology 161, 2029–2038 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill H. S. & Eisenberg D. The crystal structure of phosphinothricin in the active site of glutamine synthetase illuminates the mechanism of enzymatic inhibition. Biochemistry 40, 1903–1912 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang P., Mayo A. E. & Ninfa A. J. Escherichia coli glutamine synthetase adenylyltransferase (ATase, EC 2.7.7.49): Kinetic characterization of regulation by PII, PII-UMP, glutamine, and α-ketoglutarate. Biochemistry 46, 4133–4146 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y. T. et al. In vitro characterization of enzymes involved in the synthesis of nonproteinogenic residue (2S,3S)-B-methylphenylalanine in glycopeptide antibiotic mannopeptimycin. Chem Bio Chem 10, 2480–2487 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamazaki K. In Handb. Glycosyltransferases Relat. Genes 1465–1479 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Grimm B. Primary structure of a key enzyme in plant tetrapyrrole synthesis: glutamate 1-semialdehyde aminotransferase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87, 4169–4173 (1990). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tesson A. R., Soper T. S., Ciustea M. & Richards N. G. J. Revisiting the steady state kinetic mechanism of glutamine-dependent asparagine synthetase from Escherichia coli. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 413, 23–31 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newton G. L. & Fahey R. C. Regulation of mycothiol metabolism by sigma(R) and the thiol redox sensor anti-sigma factor RsrA. Mol. Microbiol. 68, 805–809 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg J., Tymocozko J. & Stryer L. Biochemistry (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Feehily C. & Karatzas K. A. G. Role of glutamate metabolism in bacterial responses towards acid and other stresses. J. Appl. Microbiol. 114, 11–24 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee K. L., Singh A. K., Heo L., Seok C. & Roe J. H. Factors affecting redox potential and differential sensitivity of SoxR to redox-active compounds. Mol. Microbiol., doi: 10.1111/mmi.13068 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb H. K. et al. The negative transcriptional regulator NmrA discriminates between oxidized and reduced dinucleotides. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 32107–32114 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra S. & Imlay J. Why do bacteria use so many enzymes to scavenge hydrogen peroxide? Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 525, 145–160 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youn H. D., Kim E. J., Roe J. H., Hah Y. C. & Kang S. O. A novel nickel-containing superoxide dismutase from Streptomyces spp. Biochem. J. 318 (Pt 3), 889–896 (1996). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn J., Oh S. & Roe J. Role of OxyR as a peroxide-sensing positive regulator in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2). J. Bacteriol. 184, 5214–5222 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim M. S. et al. Conservation of thiol-oxidative stress responses regulated by SigR orthologues in actinomycetes. Mol. Microbiol. 85, 326–344 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh S. Y., Shin J. H. & Roe J. H. Dual role of OhrR as a repressor and an activator in response to organic hydroperoxides in Streptomyces coelicolor. J. Bacteriol. 189, 6284–6292 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin J. H., Singh A. K., Cheon D. J. & Roe J. H. Activation of the SoxR regulon in Streptomyces coelicolor by the extracellular form of the pigmented antibiotic actinorhodin. J. Bacteriol. 193, 75–81 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuttard C. Temperate Phages of Streptomyces venezuelae: Lysogeny and Host Specificity Shown by Phages SV1 and SV2. Microbiology 128, 115–121 (1982). [Google Scholar]

- Kieser T., Bibb M. J., Buttner M. J., Chater K. F. & Hopwood D. A. Practical Streptomyces Genetics. John Innes Cent. Ltd. 529, doi: 10.4016/28481.01 (2000). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gust B., Challis G. L., Fowler K., Kieser T. & Chater K. F. PCR-targeted Streptomyces gene replacement identifies a protein domain needed for biosynthesis of the sesquiterpene soil odor geosmin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100, 1541–1546 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson B. J. et al. Investigating lipoprotein biogenesis and function in the model Gram-positive bacterium Streptomyces coelicolor. Mol. Microbiol. 77, 943–957 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchings M. I., Hong H.-J. & Buttner M. J. The vancomycin resistance VanRS two-component signal transduction system of Streptomyces coelicolor. Mol. Microbiol. 59, 923–935 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Bassam M. M., Bibb M. J., Bush M. J., Chandra G. & Buttner M. J. Response regulator heterodimer formation controls a key stage in Streptomyces development. PLos Genet. 10, e1004554 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reja R., Vinayachandran V., Ghosh S. & Pugh B. F. Molecular mechanisms of ribosomal protein gene coregulation. Genes Dev 29, 1942–1954 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trapnell C. et al. Differential gene and transcript expression analysis of RNA-seq experiments with TopHat and Cufflinks. Nat. Protoc. 7, 562–578 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amman F. et al. TSSAR: TSS annotation regime for dRNA-seq data. BMC Bioinformatics 15, 89 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford M. M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72, 248–254 (1976). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crack J., Green J., Le Brun N. & Thomson A. Detection of Sulfide Release from the Oxygen-sensing [4Fe-4S] Cluster of FNR. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 18909–18913 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kibbe W. A. OligoCalc: An online oligonucleotide properties calculator. Nucleic Acids Res. 35, 43–46 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datsenko K. a & Wanner B. L. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97, 6640–6645 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacNeil D. J. et al. Analysis of Streptomyces avermitilis genes required for avermectin biosynthesis utilizing a novel integration vector. Gene 111, 61–68 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang J. G. et al. RsrA, an anti-sigma factor regulated by redox change. EMBO J. 18, 4292–4298 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Studier F. W. & Moffatt B. A. Use of bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase to direct selective high-level expression of cloned genes. J. Mol. Biol. 189, 113–130 (1986). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory M. A., Till R. & Smith M. C. M. Integration Site for Streptomyces Phage φBT1 and Development of Site-Specific Integrating Vectors. Society 185, 5320–5323 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.