Abstract

Stunting is the best summary measure of chronic malnutrition in children. Approximately one-quarter of children under age 5 worldwide are stunted. Lipid-based or micronutrient supplementation has little to no impact in reducing stunting, which suggests that other critical dietary nutrients are missing. A dietary pattern of poor-quality protein is associated with stunting. Stunted children have significantly lower circulating essential amino acids than do nonstunted children. Inadequate dietary intakes of essential amino acids could adversely affect growth, because amino acids are required for synthesis of proteins. The master growth regulation pathway, the mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1) pathway, is exquisitely sensitive to amino acid availability. mTORC1 integrates cues such as nutrients, growth factors, oxygen, and energy to regulate growth of bone, skeletal muscle, nervous system, gastrointestinal tract, hematopoietic cells, immune effector cells, organ size, and whole-body energy balance. mTORC1 represses protein and lipid synthesis and cell and organismal growth when amino acids are deficient. Over the past 4 decades, the main paradigm for child nutrition in developing countries has been micronutrient malnutrition, with relatively less attention paid to protein. In this Perspective, we present the view that essential amino acids and the mTORC1 pathway play a key role in child growth. The current assumption that total dietary protein intake is adequate for growth among most children in developing countries needs re-evaluation.

Keywords: amino acids, children, diet, food, growth, mTORC1, proteins, stunting

Introduction

Linear growth failure is common among young children in low-income countries. Stunting, defined as a height-to-age z score <−2, affects one-quarter of children under the age of 5 y. Stunting is the best-available summary measure of chronic malnutrition in children. In 2014, there were an estimated 667 million children in the world <5 y of age, of whom 159 million were stunted (1). Stunting is associated with increased morbidity and mortality, impaired cognitive and motor development, reduced economic productivity, and a greater chance of being impoverished in adulthood (2–6). These are the main reasons why there is a high priority placed on preventing child stunting in the international health agenda. The World Health Assembly and the UN have a global target to reduce the number of stunted children <5 y of age by 40% by the year 2025 (7, 8).

Stunting is attributed to micronutrient deficiencies, lack of breastfeeding, poor hygiene, and infectious diseases (9). It has been widely assumed since the mid-1970s that children in developing countries have adequate dietary protein intakes (10, 11). Micronutrient malnutrition has been the major paradigm for the past 4 decades (12–16). Although micronutrient supplementation or fortification reduces morbidity and mortality in young children (12–14), micronutrient supplementation or lipid-based supplements with micronutrients have little to no effect on stunting (17–21), suggesting that some fundamental dietary nutrients are lacking.

In this Perspective, we present evidence for the argument that stunted children have an inadequate intake of essential amino acids and that this inadequate dietary intake of essential amino acids is likely to negatively affect growth through the master growth regulatory pathway, the mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR)9 complex 1 (mTORC1) pathway. We review specific growth processes relevant to child stunting that are regulated by mTORC1 and the effects of dietary restriction of essential amino acids in animal models. Finally, given the assumption that the dietary intake of essential amino acids plays an important role in linear growth, we examine the current recommendations and issues regarding amino acid intakes in children.

Deficiencies in Essential Amino Acids in Children with Stunting

Low dietary intakes of quality protein were strongly associated with child stunting in a study involving data from 116 countries (22). In more recent work in >300 children aged 12–59 mo in rural Malawi, serum amino acids were measured by using stable isotope–dilution LC-tandem MS. Stunted children had significantly lower serum concentrations of all 9 essential amino acids and significantly lower serum concentrations of 3 conditionally essential amino acids, other nonessential proteinogenic amino acids, biogenic amines, amino acid metabolites, and sphingolipids and alterations in glycerophospholipids (23). Tryptophan may be the limiting essential amino acid in much of sub-Saharan Africa, because the primary source of energy in the diet is maize (Zea mays), a poor source of tryptophan (24).

The mTORC1 Pathway

mTOR is a master regulator of cell and growth and metabolism for all eukaryotes (25, 26). The target of rapamycin (TOR) genes TOR1 and TOR2 were identified as targets of rapamycin, a macrolide that arrested growth (27). Rapamycin is produced by Streptomyces hygroscopicus, a bacterium isolated from Easter Island (Rapa Nui) (28). The mammalian ortholog of mTOR was subsequently identified and cloned (26).

mTOR, a serine/threonine protein kinase, is the core component of 2 large, distinct signaling complexes: mTORC1 and mTORC2 (26). mTORC1 integrates 5 major signals for cell growth: nutrients, growth factors, oxygen, energy, and stress. mTORC2 plays a role in cytoskeletal organization and cell survival (26). mTORC1, better characterized than mTORC2, is the focus of this review. mTORC1, when activated, promotes anabolic processes such as protein, lipid, and nucleotide synthesis and inhibits catabolic processes such as autophagy. mTORC1 is a ∼1-MDa homodimer that has the approximate shape of a doughnut (29). mTORC1 consists of mTOR, raptor, deptor, mLST8, pras40, and 2 scaffold proteins (tti1, tel2).

Upstream Regulation of mTORC1 by Nutrients and Other Factors

When amino acid concentrations are low, mTORC1 is diffusely distributed in the cytosol and is inactive (30). When amino acids are sufficient, mTORC1 translocates to the lysosomal membrane (30) (Figure 1). Ras homolog enriched in brain (Rheb) is required for mTORC1 activation (31). The Ras-related GTP-binding protein (Rag) family of Rag GTPases consists of RagA, RagB, RagC, RagD in humans. The Rag GTPases act as molecular switches: inactive, bound to GDP, and active, bound to GTP (30, 32). Under conditions of amino acid sufficiency, RagA/B are GTP-bound and capable of binding raptor. The Rag GTPases are activated or inactivated by guanine nucleotide exchange factors and GTPase-activating proteins, respectively. Rag proteins are anchored to the lysosomal surface by Ragulator, a scaffolding complex and guanine nucleotide exchange factor (32).

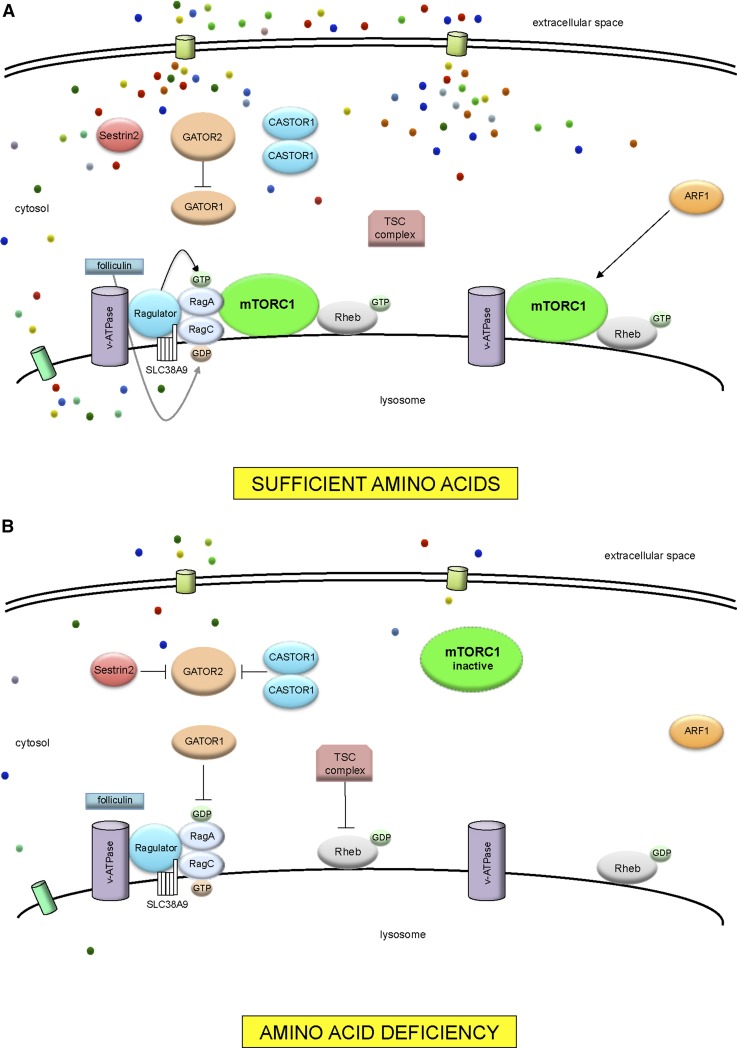

FIGURE 1.

The mTORC1 amino acid–sensing pathway. (A) With sufficient amino acids, GATOR1 is inhibited by GATOR2. Ragulator and v-ATPase undergo a conformation change. GEF activity is promoted by Ragulator toward RagA. Folliculin promotes GAP activity toward RagC, causing GTP hydrolysis. The active RagA/BGTP-RagC/DGDP heterodimers recruit mTORC1 to the lysosomal membrane. At the lysosomal surface, mTORC1 is activated by Rheb. ARF1 is involved in Rag GTPase-independent signaling to mTORC1. (B) With amino acid deficiency, GATOR1 inhibits RagA by exerting GAP activity. Both Sestrin2 and CASTOR1 interact with GATOR2, removing inhibition of GATOR2 on GATOR1. TSC inhibits Rheb through GAP activity. Ragulator is in an inhibitory state with v-ATPase. mTORC1 remains inactive in the cytoplasm. ARF1, ADP-ribosylation factor 1; GAP, GTPase-activating protein; GATOR, GAP activity towards Rags (Ras-related GTPases) GEF, guanine nucleotide exchange factor; mTORC1, mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1; Rag, Ras-related GTP-binding protein; Rheb, Ras homolog enriched in brain; SLC38A9, solute carrier family 38, member 9; TSC, tuberous sclerosis complex; v-ATPase, vacuolar H+-ATPase.

The vacuolar H+-ATPase (v-ATPase) is involved in extensive amino acid–dependent interactions with Ragulator (33). Ragulator is the guanine nucleotide exchange factor for RagA/B (32). Folliculin and folliculin interacting protein 1 function as GTPase-activating proteins for RagC/D (34). GTPase-activating protein activity towards Rags (GATOR), an octomeric complex consisting of subcomplexes GATOR1 and GATOR2, acts as a negative and positive regulator, respectively, of mTORC1 (35). When amino acids are low, GATOR1 causes RagA/B to switch to an inactive GDP-bound state, thus releasing mTORC1 from the lysosomal surface and rendering mTORC1 inactive in the cytoplasm (35).

Amino acids are essential for the activation of mTORC1. In their absence other signals, such as growth factors and energy, cannot overcome the lack of amino acids to activate mTORC1 (36). Amino acid transporters mediate the exchange of amino acids from extracellular to intracellular space as amino acid carriers, with some acting as amino acid sensors (37). Solute carriers (SLCs) that transport amino acids across the plasma membrane include SLC family 7, member 5 (SLC7A5); SLC3A2; and SLC1A5 (38). Amino acids can activate the Rag GTPases directly (26). Many proteins have been identified in cytosol as potential amino acid sensors and signaling transducers to mTORC1 (26, 36, 37). Sestrin2 is a leucine sensor in the cytosol that interacts with GATOR2 to inhibit mTORC1 (39). Amino acid signaling is also initiated in the lysosomal lumen via v-ATPase (33) and SLC38A9 (40). Differential regulation of mTORC1 occurs through leucine (26, 33, 39, 41, 42), glutamine (41, 43, 44), and arginine (40, 42, 45). Leucine and glutamine can stimulate mTORC1 by both Rag GTPase–dependent and –independent mechanisms (41). ADP-ribosylation factor 1 (ARF1) is involved in Rag GTPase-independent signaling to mTORC1 (41).

Cellular lipid sufficiency to mTORC1 is signaled by phosphatidic acid (PA), a key intermediate in lipid metabolism (46). PA is essential for the activity of mTORC1 (26, 47). Growth factors signal mTORC1 through class I phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) (48). After growth factors activate receptor kinases or G-protein–coupled receptors, PI3K is activated and inhibits tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) in a pathway involving protein kinase Akt. TSC inhibits mTORC1 (49). The effects of hypoxia (50), energy deficiency, such as glucose deprivation (51), and genotoxic stress induced by exposure to agents that damage genetic information (52) are mediated in mTORC1 through TSC. TSC is a GTPase-activating protein for Rheb (53).

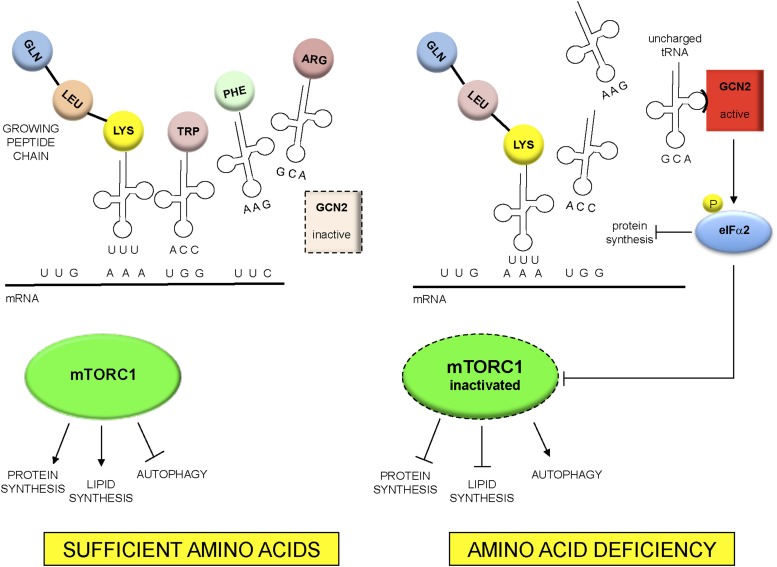

The general control non-derepressible 2 (GCN2) pathway senses the lack of amino acids during synthesis of peptides on the ribosome. The ribosome incorporates amino acids into a growing peptide by sequential binding of specific transfer RNAs (tRNAs) covalently bound to cognate amino acids. A tRNA that is bound with an amino acid is termed “charged.” With insufficiency of any free amino acids required for the synthesis of peptides, uncharged tRNAs accumulate. GCN2 binds with high affinity to all uncharged tRNAs (54). Upon binding with uncharged tRNA, GCN2 phosphorylates eukaryotic translation initiation factor (eIF) 2α (eIFα2), an early activator of translation initiation (Figure 2). As a result, mRNA translation slows, favoring gene-specific translation of mRNAs that contain an upstream open-reading frame in their 5′ untranslated region, such as activating transcription factor 4 (ATF4). ATF4 activates genes that are involved in amino acid metabolism in adaptation to amino acid deficiency (55). ATF4 upregulated by activated GCN2 will, in turn, induce the expression of Sestrin2 (56). A unifying model by which GCN2 and Sestrin2 regulate mTORC1 by different amino acids has been difficult to establish (57). It has been suggested that Sestrin2 inhibits mTORC1 through the modulation of the GATOR complex (58). However, upon leucine or arginine deprivation, GCN2 has been shown to provide input to mTORC1 signaling that does not require ATF4 expression or induction of Sestrin2 (57). Aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases catalyze the ligation of amino acids to their cognate tRNAs. Leucyl-tRNA synthetase, a component of the multi-tRNA synthetase complex that includes 9 tRNA synthetases (59), also serves as an intracellular leucine sensor for the mTORC1 pathway (59, 60).

FIGURE 2.

GCN2 pathway of amino–acid sensing and interaction with mTORC1. GCN2 specifically recognizes “uncharged” tRNAs not covalently bound to cognate amino acids. With amino acid deficiency, uncharged tRNAs accumulate and bind to GCN2. GCN2 then phosphorylates (P) and inhibits eIFα2 and protein synthesis. Studies have shown that amino acid deficiency can inhibit mTORC1, either through ATF4 and Sestrin2 or independent of these 2 mediators. Inhibition of mTORC1 represses protein and lipid synthesis and promotes autophagy. ATF4, activating transcription factor 4; eIFα2, eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2α GCN2, general control non-derepressible 2; mTORC1, mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1; tRNA, transfer RNA.

Downstream Regulation of Cell Growth and Metabolism by mTORC1

mTORC1 upregulates protein synthesis and cell growth by phosphorylating p70 ribosomal protein S6 kinase (S6K1) (61) and eIF 4E–binding protein 1 (4E-BPI) (62). Once activated, S6K1 phosphorylates proteins that promote protein synthesis, such as eIF4B (63), eukaryotic elongation factor 2 (eEF2) kinase (64), and programmed cell death protein 4 (PDCD4) (65). S6K1 phosphorylates ribosome protein S6 (rpS6), a component of the 40s ribosome (66) that plays a role in cell growth and size. Other substrates of S6K1 include S6K1 Aly/REF-like target (SKAR) (67) and 80-kDa nuclear cap binding protein (CBP80) (68), involved in mRNA processing.

Autophagy, an adaptation to nutrient starvation, is a process by which damaged or redundant proteins and other cell components are delivered to the lysosome and then degraded, releasing free amino acids into the cytoplasm. Proteins provide a reservoir of amino acids that are mobilized through autophagy when amino acids are scarce. mTORC1 promotes growth by negatively regulating autophagy through 2 kinase complexes, Unc-51 like kinase-1 (ULK1) complex and vacuolar protein sorting 34 (VPS34) complex (69). The ULK1 complex is required to initiate autophagy and is phosphorylated by mTORC1 in the presence of sufficient amino acids (69). mTORC1 also phosphorylates Autophagy/Beclin-1 regulator 1 (AMBRA1), which indirectly inhibits ULK1 (69). After amino acid starvation, ULK1 is activated and phosphorylates Beclin-1, enhancing the activity of the VPS34 complex (70). Autophagy thus makes amino acids, FAs, and ATP available for cell synthesis. The basic helix-loop-helix leucine zipper transcription factor EB (TFEB) is a master regulator of genes encoding proteins of the autophagy-lysosome pathway (71). TFEB plays a role in linking mTORC1 signaling to transcriptional control of lysosome homeostasis (71).

mTORC1 promotes lipogenesis by upregulating the expression of lipogenic genes (72). mTORC1 activates sterol regulatory element-binding protein (SREBP) 1, a transcription factor that controls FA synthesis (73). The effect of mTORC1 on SREBP1 is mediated by S6K1 (74) and lipin1 (75). mTORC1 also inhibits ketogenesis. In response to fasting, the liver produces ketone bodies to provide energy for peripheral tissues, including the brain. mTORC1 regulates the nuclear localization of nuclear receptor corepressor 1 (NCoR1), which interacts with PPARα (76) through S6 kinase 2 (S6K2) (77). PPARα promotes genes involved in FA oxidation and ketogenesis. With inactivation of mTORC1, lipin1 represses SREBP1 transcription of genes involved in adipogenesis and lipogenesis (75).

mTORC1 stimulates the synthesis of pyrimidines (78, 79) and phosphorylates carbamoyl-phosphate synthetase 2 (CAD), which promotes de novo pyrimidine synthesis (70). Signaling of mTORC1 to CAD is mediated by S6K1 (79). The regulation of pyrimidine synthesis by mTORC1 is a mechanism by which the pool of nucleotides for RNA and DNA synthesis is available for growth.

Role of the Master Growth Regulator mTORC1 in Child Growth

As the master growth regulator, mTORC1 plays a major role during the period of the most rapid growth in children. mTORC1 has attracted a great deal of attention because of its implications for obesity, diabetes (26), cancer (80), and longevity (81), but much less attention has been paid to its importance in child growth. The role of mTORC1 in human health during the fastest period of growth in childhood is likely to be very different than at the opposite end of the life span, where the focus has been on the inhibition of mTORC1 (81). mTORC1 controls growth and metabolism of all cells in the human body, including bone, skeletal muscle, central nervous system, gastrointestinal tract, blood cells, and other organs, which are relevant to child stunting and its associated morbidities such as anemia, impaired cognition, environmental enteric dysfunction, and immunity against infectious diseases (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Growth processes regulated by mTORC11

| Growth process |

| Chondral plate and bone growth |

| Skeletal muscle growth and homeostasis |

| Myelination of nervous system |

| Small intestine homeostasis |

| Iron metabolism and hematopoiesis |

| Immune function |

| Organ size |

mTORC1, mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1.

mTORC1 regulates growth in the chondral plate.

The elongation of tubular bones occurs at the growth plate through endochondral ossification, a process in which cartilage is replaced by bone tissue (82). The rate of chondrogenesis determines children’s height (83) and is regulated by mTORC1 (84, 85). In precartilaginous stem cells, the expression of chondrogenesis-related genes is induced by TGF-β through mTORC1 (86). mTORC1 stimulates both chondrocyte growth, synthesis of extracellular matrix, and transition of chondrocytes to a hypertrophic state (85). Leucine deficiency inhibits proliferation and differentiation of chondrocytes through mTORC1 (87). Direct inhibition of mTORC1 with rapamycin reduces the growth of long bones (88). mTORC1 regulates differentiation of osteoblasts from preosteoblasts (89). Control of osteoblast proliferation and bone formation by Wnt signaling is mediated by mTORC1 (90).

mTORC1 regulates skeletal muscle growth.

Bone and skeletal muscles have overlapping mechanisms in development because bone mass is regulated, in part, by muscle-derived mechanical forces (91). mTORC1 plays a role in skeletal muscle growth induced in response to mechanical stimuli (91). Mechanically induced mTORC1 signaling is mediated through PA synthesized by diacylglycerol kinases (92). Leucine upregulates mTORC1 in skeletal muscle in mice (93). Dietary lysine increases mTORC1 signaling in skeletal muscle of rats and suppresses autophagy (94). In mice, tryptophan supplementation stimulates mTORC1 signaling in skeletal muscle and upregulates the expression of myogenic genes (95). Manjarín et al. (96) studied the effects of leucine supplementation in the presence of inadequate protein and energy intakes. In 4-d–old piglets fed 70% of protein and energy requirements for 8 d, leucine supplementation increased mTOR activation in skeletal muscle but did not improve body weight or increase protein synthesis in skeletal muscle.

mTORC1 regulates myelination of the central and peripheral nervous system.

Myelin is a lipid-rich, multilamellar structure that encloses axons and facilitates rapid conduction of nerve impulses. Myelin is produced by oligodendrocytes and glial cells in the central nervous system by Schwann cells in the peripheral nervous system. Myelin is composed primarily of lipids, such as cholesterol, sphingolipids, and glycerophospholipids, and a small proportion of proteins. In the central nervous system, myelination is mainly dependent on kinase Akt signaling through mTORC1 (97, 98). In the peripheral nervous system, mTORC1 controls myelination and lipid synthesis by Schwann cells through nuclear receptor retinoic acid receptor γ (RXRγ) and SREBP (99).

mTORC1 regulates cellular growth and differentiation in the small intestine.

The intestinal mucosa undergoes a constant process of renewal in which multipotent stem cells in the crypts of Lieberkühn differentiate into 6 epithelial cell types: enterocytes, enteroendocrine cells, goblet cells, Paneth cells, tuft cells, and microfold cells (100). The turnover rate of the entire epithelial population of the intestine is ∼60 h (101). Absorptive enterocytes comprise most of the villi and after differentiation undergo apoptosis and extrusion into the gut lumen. Goblet and enteroendocrine cells secrete mucus and hormones. Paneth cells are located in the bottom of the crypt and are involved in mucosal immunity. Intestinal stem cells are maintained in a dormant state by phosphatase and tensin homolog, a negative regulator of the PI3K/Akt/mTORC1 pathway (102). Notch signaling plays a major role in the differentiation of intestinal stem cells (101). mTORC1 controls the differentiation of Paneth and goblet cells through the regulation of Notch signaling (103, 104). mTORC1 is involved in intestinal regeneration after inflammation or injury (105, 106). Tryptophan activates mTORC1 and the expression of tight junction proteins that maintain gut barrier function (107).

mTORC1 regulates hematopoiesis and iron metabolism.

mTORC1 regulates hematopoietic stem cell renewal and differentiation (108) and hematopoiesis through raptor (109). mTORC1 also regulates erythrocyte growth and proliferation (110) and hemoglobin synthesis (111). Cellular iron homeostasis is modulated by the iron-responsive element/iron-regulatory protein (IRE/IRP) regulatory network (112) and hepcidin (113). A third pathway involving mTOR, tristetraprolin, and transferrin receptor 1 may mediate iron homeostasis in parallel with the IRE/IRP and hepcidin systems (114, 115).

mTORC1 and immune function.

Both mTORC1 and mTORC2 are implicated in differentiation of T cell lineages into effector and regulatory T cells (116). In CD8+ T cells, differentiation to effector cells or memory cells is mediated by mTORC1 and mTORC2, respectively (117). Peripheral activation of NK cells by IL-15 is mediated by mTORC1 (118). B-cell development and function are controlled by both mTORC1 and mTORC2 (119, 120). mTORC1 controls antibody class switching in B lymphocytes (121).

mTORC1 regulates organ size through the Hippo pathway.

The Hippo pathway controls organ growth and size (122, 123). The pathway is a kinase cascade in which mammalian Ste20-like kinases 1/2 (MST1/2) phosphorylate and activate large tumor suppressor 1/2 (LATS1/2) and inhibit 2 transcriptional coactivators, Yes-associated protein (YAP) and transcriptional activator with a PDZ-binding domain (TAZ) (123). YAP and TAZ are transcriptional activators for genes that promote growth and proliferation. They potentiate mTORC1 activity by increasing the expression of l-type amino acid transporter (LAT1), a major high-affinity leucine transporter (124). Increased LAT1 expresion facilitates cellular uptake of leucine, thus linking amino acid availability to mTORC1 activity (124).

Limitation of Essential Amino Acids and Growth in Animal Models

Between 1906 and 1948, investigators identified 9 amino acids that, when excluded from food, resulted in profound growth failure and eventual death in rats (125). The essential amino acids were tryptophan, isoleucine, leucine, valine, methionine, threonine, histidine, phenylalanine, and lysine. These amino acids were considered essential amino acids, because they cannot be synthesized de novo in the body and can only be obtained through diet. Subsequent studies showed that the same 9 amino acids were essential in humans as well (126). The effects of dietary restriction of some of these essential amino acids, such as tryptophan, leucine, isoleucine, histidine, threonine, and lysine, have been studied in the past 5 decades by using controls or pair feeding. Some of these studies specifically addressed growth regulation through the mTORC1 and GCN2 pathways, whereas others provided additional empirical evidence for growth regulation by essential amino acids (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Experimental effects of essential amino acid restriction in young animals1

| Amino acid | Model | Effects of deficiency | References |

| Tryptophan | Rats; tryptophan-free diet during pregnancy | Newborn rats with dwarfism, skeletal muscle hypotrophy, low growth hormone concentrations | 127 |

| Rats; tryptophan-free diet during pregnancy and in pups | Newborn rats with dwarfism, impaired growth, low growth hormone concentrations | 128 | |

| Rats; lactating dams and pups; restriction until postnatal day 21 | Serotonin depletion in the brain, reduced developmental plasticity in the brain | 129, 130 | |

| Rats; 1 mo of restriction 30–60 d after birth | Decreased serotonin content in several brain regions, altered dendritic spine density in CA1 pyramidal cells and granule cells of the hippocampus, increased astrocyte cytoskeletal hypertrophy in the hippocampus and amygdala | 131, 132 | |

| Leucine | Mice; 4–6 wk old; leucine-free diet for 6 d | GCN2−/− mice lost skeletal muscle mass and had high mortality; wild-type mice lost body weight and liver mass | 133 |

| Mice; 8–10 wk old; leucine-free diet for 7 or 17 d | Repression of SREBP and downregulation of lipogenesis | 134 | |

| Mice; 8–10 wk old; leucine-free diet for 7 d | Decrease in fat mass, increased lipolysis, increased expression of β-oxidation genes, 15% decreased food intake, increased energy expenditure | 135 | |

| Mice; 8–10 wk old; leucine-free diet for 7 d | Increased insulin sensitivity, reduced mTOR signaling, activated GCN2 signaling | 136, 137 | |

| Isoleucine | Mice; 8–10 wk old; isoleucine-free diet for 7 d | Decrease in fat mass, increased lipolysis, 39% decreased food intake, increased energy expenditure, increased insulin sensitivity, downregulation of mTOR signaling, upregulation of AMPK signaling | 137, 138 |

| Valine | Mice; 8–10 wk old; valine-free diet for 7 d | Decrease in fat mass, increased lipolysis, 25% decreased food intake, increased energy expenditure, increased insulin sensitivity, downregulation of mTOR signaling, upregulation of AMPK signaling | 137, 138 |

| Histidine | Rats; histidine-free diet for 14 d | Impaired growth | 139 |

| Rats; young animals; histidine-free, low histidine, or histidine-adequate diet for 8–13 d; gastric tube feeding to provide equal amounts of diet | Impaired growth, decrease in hemoglobin and hematocrit, decrease in plasma and muscle histidine | 140 | |

| Mice; 7 and 17 wk old; histidine-free diet for 16–20 d | Impaired growth | 141 | |

| Threonine | Rats; threonine restriction for 14 d | Impaired growth, reduced synthesis of intestinal mucins | 142 |

| Piglets; 2 d old; intragastric feeding of threonine-restricted diet for 8 d | Impaired mucin production in the gut | 144 | |

| Piglets; 7 d old; low-threonine diet (70% of recommendation) for 2 wk | Villous atrophy in the ileum, no effect on protein metabolism in the small intestine, reduced amino acid and protein content in the liver, increased paracellular permeability in the ileum, alterations in gene expression of genes related to paracellular permeability | 144–146 | |

| Pigs; 21 d old; threonine-restricted diet for 14 d | Impaired growth; reduced protein synthesis in skeletal muscle, jejunal mucosa, and the liver; reduced synthesis of intestinal mucins | 147 | |

| Lysine | Pigs; ∼21 d old; lysine restriction for 2 wk | Impaired growth, lower expression of myostatin in skeletal muscle | 148 |

| Rats; 4 wk old; lysine restriction for 21 d | Impaired growth, reduced serum insulin-like growth factor I | 149 | |

| Pigs; 10 wk old; 70% lysine restriction for 8 wk | Impaired growth, increased intramuscular fat in skeletal muscle | 150 | |

| Rats; 52 d old; 50% or 75% lysine restriction for 25 d | Impaired growth, 75% lysine restriction, increased food intake, and increased liver and muscle lipids and abdominal fat, increased blood urea nitrogen | 151 |

Feeding studies with a control group are shown. AMPK, AMP kinase; GCN2, general control non-derepressible 2; mTOR, mechanistic target of rapamycin; mTORC1, mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1; SREBP, sterol regulatory element-binding protein.

Pregnant rats deprived of dietary tryptophan gave birth to newborn rats with dwarfism, impaired growth, and low plasma growth hormone concentrations (127, 128). Rat pups and lactating dams fed a tryptophan-restricted diet showed growth retardation accompanied by serotonin depletion and reduced developmental plasticity in the brain (129, 130). Young rats fed a tryptophan-restricted diet that was 80% lower in tryptophan than a control diet showed decreased serotonin content in brain and altered brain morphology (131, 132). GCN2−/− mice deprived of dietary leucine lost skeletal muscle mass and had high mortality (133). Young mice deprived of dietary leucine showed repression of the transcriptional factor SREBP1 and downregulation of lipid synthesis mediated via GCN2 (134). Increased lipolysis, greater expression of β-oxidation genes, and decreased expression of lipogenic genes were observed in young mice after feeding with a leucine-deficient diet for 7 d (135). Young mice fed a leucine-deficient diet showed increased insulin sensitivity, reduced mTOR signaling, and activated GCN2 signaling (136, 137). A decrease in fat mass, increased lipolysis, increased energy expenditure, increased insulin sensitivity, downregulation of mTOR signaling, and upregulation of AMP kinase (AMPK) signaling were found in young mice fed diets deficient in either isoleucine or valine (137, 138).

Rats fed a histidine-deficient diet had impaired growth and reduced hemoglobin (139–141). In rats or pigs fed a threonine-deficient diet, a consistent finding was a reduced synthesis of mucins in the gut (142–147). In addition, increased gut permeability was observed in piglets fed a diet with moderate threonine restriction (146). These findings suggest that an insufficient dietary intake of threonine could potentially contribute to the risk of environmental enteric dysfunction by compromising the protective mucin layer of the gut and increasing gut permeability. Dietary lysine restriction resulted in impaired growth in young rats and pigs (148–151).

In rats fed a diet lacking in glycine, tryptophan, leucine, or the BCAAs for 1 h, hepatic protein synthesis was reduced (152). This work suggested that global rates of protein synthesis in the liver are blocked by essential amino acid deficiency at the level of translation initiation (152).

Protein Intake of Children in Developing Countries—Time for a Reassessment?

Amino acid requirements in young children.

We have presented a hypothesis that essential amino acids and signaling through the mTORC1 pathway play a major role in the linear growth of children. If further work corroborates this idea, then it will be of paramount importance that children in developing countries regularly receive the dietary requirements for essential amino acids. Current WHO/FAO/United Nations University requirements for amino acids in children are based on a factorial computation (153–155). For children <6 mo of age, amino acid requirements are based on amino acid composition of breast milk. For children >6 mo old, requirements are based on age-dependent rates of growth, amino acid composition of whole-body protein, and efficiency of dietary protein utilization. These estimates are not based on actual data from assessments such as the indicator amino acid oxidation (IAAO) method for individual amino acids (154) and do not consider the added requirements of catch-up growth (156) or high infectious disease burden that is common among children in developing countries (157). The IAAO method has been used to assess the requirement of a single amino acid in humans (158). Acute feeding studies are conducted in subjects who have fasted overnight. On each study day, the subject consumes repeated small meals containing fixed intakes of amino acid mixtures at the approximate protein requirement that contains an indicator amino acid, usually 13C-labeled phenylalanine, with variable amounts of the test amino acid. During the feeding period, the oxidation of the indicator amino acid is measured. From the feedings on separate days, a dose-response relation of the indicator oxidation amino acid to the test amino acid is determined (158). The amount of test amino acid that allows efficient utilization of all of the other amino acids is identified by a breakpoint in the intake-oxidation curve from high to low and constant rates of oxidation (158). Thus, the IAAO method is based on the concept that when one indispensable amino acid is deficient for protein synthesis, then the indicator amino acid and all other indispensible amino acids will be oxidized (159).

The nitrogen balance technique, which is based on the idea that gain or loss of nitrogen from the body is synonymous with gain or loss of protein, has been a classic approach to determining protein and amino acid content (153, 160). However, the nitrogen balance technique has serious limitations due to the technical aspects of the accurate quantification of all routes of nitrogen intake and all routes of loss (153, 160). Whether estimations of nitrogen balance really answer the protein needs of children to achieve optimal growth during the critical period of birth to 2 y of age is unclear (156). Dietary requirements for lysine, with the use of the IAAO method, increased by ∼20% in undernourished children with intestinal parasites (157). The burden of infectious disease and metabolic needs for immune system activation, which requires high energy and amino acids (161), may partition limited essential amino acids to support immune function at the expense of growth (162).

Assessment of dietary protein quality.

The estimation of dietary protein quality is based on digestion of proteins and absorption of their constituent amino acids (digestibility) and utilization of absorbed amino acids to support whole-body protein synthesis (availability) (163). The most commonly used estimation of protein quality is the Protein Digestibility-Corrected Amino Acid Score (PDCAAS) (164), based on comparing the concentration of the first limiting essential amino acid of a test protein with the essential amino acid requirements of a preschool-aged child (165). The PDCAAS is limited in that assumptions about essential amino acid requirements in young children may be inaccurate, as noted above, especially for children in developing countries. In addition, the PDCAAS does not allocate additional nutritional value to high-quality proteins, overestimates the protein quality of products with antinutritional factors (i.e., tannins, phytates and phytic acid, trypsin inhibitors, glucosinolates, isothiocyanates), does not factor in the bioavailability of amino acids, and overestimates the quality of poorly digestible proteins supplemented with limited amino acids and of proteins limited in >1 amino acid (165). The FAO is now considering a new index, the Digestible Indispensable Amino Acid Score, or DIAAS, which is the percentage of digestible dietary indispensable amino acids in 1 g of a dietary protein divided by milligrams of the same dietary indispensable amino acid in 1 g of a reference protein (165). The DIAAS requires measurement of ileal digestibility for individual amino acids by using stable isotope–labeled proteins or IAAO (165).

Animal source protein and child growth.

The consumption of animal-source foods, the richest source of essential amino acids, is limited among children in developing countries (166). Animal-source foods provide <5% of total energy intakes in many countries in sub-Saharan Africa and 5–10% of total energy intakes in most other African countries and South Asia (166). By comparison, animal-source foods provide >20% of total energy intakes in Europe, the United States, Canada, and Australasia (166). The consumption of animal-source foods is associated with a lower risk of stunting (166, 167).

Stature in adulthood is closely linked to the linear growth that occurs in children in the first few years of life. The increase over time in height among Dutch children provides clues about nutrition on linear growth. The Dutch are now the tallest people on earth (168, 169). This is in remarkable contrast to the mid-18th century, when the height of Dutch men was well below average for other European populations and 5–8 cm shorter than men in the United States (168). Dutch men grew by ∼20 cm over the past 150 y (168), a stature attributed in part to the heavy consumption of dairy products (170, 171).

Research issues.

Further work is needed to characterize serum amino acid concentrations in infants and preschool children in different developing countries with contrasting dietary patterns. Normative data on serum amino acids are needed in healthy children. The essential amino acid requirements of children in developing countries need further evaluation, because these children are exposed to a high infectious disease burden and poor sanitation. A large proportion of children at risk of stunting have environmental enteric dysfunction, which could potentially affect amino acid metabolism (172). Most knowledge on the mTORC1 pathway is derived from in vitro studies and animal models. In humans, evidence for amino acid signaling through the mTORC1 pathway could be provided through future investigations that combine metabolomics with characterization of the proteome and transcriptome. Future work could also be done to explore the concept of a meal-based protein threshold for children (173).

Conclusions

Child stunting affects one-quarter of all children <5 y of age worldwide. The mTORC1 pathway is a master controller of cell and organismal growth and is exquisitely sensitive to the availability of amino acids for the synthesis of proteins. mTORC1 regulates growth of bone, skeletal muscle, nervous system, gastrointestinal tract, hematopoietic cells, immune effector cells, organ size, and whole-body energy balance. Stunted children in developing countries have an insufficient intake of essential amino acids. Future studies should address dietary intakes of essential amino acids in relation to growth in children in developing countries. Identified deficiencies can then be used to develop better nutritional guidance, food, and complementary feeding for children around the world.

Acknowledgments

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used: ATF4, activating transcription factor 4; eIF, eukaryotic translation initiation factor; GATOR, GTPase-activating protein activity towards Rags; GCN2, general control non-derepressible 2; IAAO, indicator amino acid oxidation; mTOR, mechanistic target of rapamycin; mTORC, mechanistic target of rapamycin complex; PA, phosphatidic acid; PDCAAS, Protein Digestibility-Corrected Amino Acid Score; PI3K, class I phosphoinositide 3-kinase; Rag, Ras-related GTP-binding protein; SLC, solute carrier; SREBP, sterol regulatory element-binding protein; S6K1, p70 ribosomal protein S6 kinase; TOR, target of rapamycin; tRNA, transfer RNA; TSC, tuberous sclerosis complex; ULK1, Unc-51 like kinase-1.

References

- 1.UNICEF/WHO/World Bank Group. Levels and trends in child malnutrition: key findings of the 2015 edition [cited 2016 Jan 7]. Available from: http://www.who.int/nutgrowthdb/jme_brochure2015.pdf?ua=1.

- 2.Grantham-McGregor S, Cheung YB, Cueto S, Glewwe P, Richter L, Strupp B; International Child Development Steering Group. Developmental potential in the first 5 years for children in developing countries. Lancet 2007;369:60–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Victora CG, Adair L, Fall C, Hallal PC, Martorell R, Richter L, Sachdev HS; Maternal and Child Undernutrition Study Group. Maternal and child undernutrition: consequences for adult health and human capital. Lancet 2008;371:340–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Olofin I, McDonald CM, Ezzati M, Flaxman S, Black RE, Fawzi WW, Caulfield LE, Danaei G. Nutrition Impact Model Study (anthropometry cohort pooling). Associations of suboptimal growth with all-cause and cause-specific mortality in children under five years: a pooled analysis of ten prospective studies. PLoS One 2013;8:e64636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hoddinott J, Behrman JR, Maluccio JA, Melgar P, Quisumbing AR, Ramirez-Zea M, Stein AD, Yount KM, Martorell R. Adult consequences of growth failure in early childhood. Am J Clin Nutr 2013;98:1170–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sudfeld CR, McCoy DC, Danaei G, Fink G, Ezzati M, Andrews KG, Fawzi WW. Linear growth and child development in low- and middle-income countries: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics 2015;135:e1266–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Onis M, Dewey KG, Borghi E, Onyango AW, Blössner M, Daelmans B, Piwoz E, Branca F. The World Health Organization’s global target for reducing childhood stunting by 2025: rationale and proposed actions. Matern Child Nutr 2013;9(Suppl 2):6–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Murray CJ. Shifting to Sustainable Development Goals—implications for global health. N Engl J Med 2015;373:1390–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Black RE, Victora CG, Walker SP, Bhutta ZA, Christian P, de Onis M, Ezzati M, Grantham-McGregor S, Katz J, Martorell R, et al. ; Maternal and Child Nutrition Study Group. Maternal and child undernutrition and overweight in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet 2013;382:427–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McLaren DS. The great protein fiasco. Lancet 1974;2:93–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Waterlow JC, Payne PR. The protein gap. Nature 1975;258:113–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maberly GF, Trowbridge FL, Yip R, Sullivan KM, West CE. Programs against micronutrient malnutrition: ending hidden hunger. Annu Rev Public Health 1994;15:277–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Semba RD. The vitamin A story: lifting the shadow of death. World Rev Nutr Diet 2012;104:i–xv. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bhutta ZA, Salam RA, Das JK. Meeting the challenges of micronutrient malnutrition in the developing world. Br Med Bull 2013;106:7–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. UNICEF. The UNICEF strategic plan, 2014–2017 [cited 2016 Feb 12]. Available from: http://www.unicef.org/strategicplan/. [Google Scholar]

- 16.World Health Organization. Micronutrients, 2010–2011. Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organization. 2011. Document No.: WHO/NMH/NHD/EPG/12.1. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ramakrishnan U, Nguyen P, Martorell R. Effects of micronutrients on growth of children under 5 y of age: meta-analyses of single and multiple nutrient interventions. Am J Clin Nutr 2009;89:191–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mayo-Wilson E, Junior JA, Imdad A, Dean S, Chan XH, Chan ES, Jaswal A, Bhutta ZA. Zinc supplementation for preventing mortality, morbidity, and growth failure in children aged 6 months to 12 years of age. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014;5:CD009384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stammers AL, Lowe NM, Medina MW, Patel S, Dykes F, Pérez-Rodrigo C, Serra-Majam L, Nissensohn M, Moran VH. The relationship between zinc intake and growth in children aged 1–8 years: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Clin Nutr 2015;69:147–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ashorn P, Alho L, Ashorn U, Cheung YB, Dewey KG, Gondwe A, Harjunmaa U, Lartey A, Phiri N, Phiri TE, et al. Supplementation of maternal diets during pregnancy and for 6 months postpartum and infant diets thereafter with small-quantity lipid-based nutrient supplements does not promote child growth by 18 months of age in rural Malawi: a randomized controlled trial. J Nutr 2015;145:1345–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van der Merwe LF, Moore SE, Fulford AJ, Halliday KE, Drammeh S, Young S, Prentice AM. Long-chain PUFA supplementation in rural African infants: a randomized controlled trial of effects on gut integrity, growth, and cognitive development. Am J Clin Nutr 2013;97:45–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ghosh S, Suri D, Uauy R. Assessment of protein adequacy in developing countries: quality matters. Br J Nutr 2012;108(Suppl 2):S77–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Semba RD, Shardell M, Sakr Ashour FA, Moaddel R, Trehan I, Maleta KM, Ordiz MI, Kraemer K, Khadeer MA, Ferrucci L, et al. Child stunting is associated with low circulating essential amino acids. EBioMedicine 2016;6:246–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nuss ET, Tanumihardjo SA. Quality protein maize for Africa: closing the protein inadequacy gap in vulnerable populations. Adv Nutr 2011;2:217–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van Dam TJ, Zwartkruis FJ, Bos JL, Snel B. Evolution of the TOR pathway. J Mol Evol 2011;73:209–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Laplante M, Sabatini DM. mTOR signaling in growth control and disease. Cell 2012;149:274–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Heitman J, Movva NR, Hall MN. Targets for cell cycle arrest by the immunosuppressant rapamycin in yeast. Science 1991;253:905–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vézina C, Kudelski A, Sehgal SN. Rapamycin (AY-22,989), a new antifungal antibiotic. I. Taxonomy of the producing streptomycete and isolation of the active principle. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 1975;28:721–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aylett CHS, Sauer E, Imseng S, Boehringer D, Hall MN, Ban N, Maier T. Architecture of human mTOR complex 1. Science 2016;351:48–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sancak Y, Bar-Peled L, Zoncu R, Markhard AL, Nada S, Sabatini DM. Ragulator-Rag complex targets mTORC1 to the lysosomal surface and is necessary for its activation by amino acids. Cell 2010;141:290–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Demetriades C, Doumpas N, Teleman AA. Regulation of TORC1 in response to amino acid starvation via lysosomal recruitment of TSC2. Cell 2014;156:786–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bar-Peled L, Schweitzer LD, Zoncu R, Sabatini DM. Ragulator is a GEF for the rag GTPases that signal amino acid levels to mTORC1. Cell 2012;150:1196–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zoncu R, Bar-Peled L, Efeyan A, Wang S, Sancak Y, Sabatini DM. mTORC1 senses lysosomal amino acids through an inside-out mechanism that requires the vacuolar H(+)-ATPase. Science 2011;334:678–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tsun ZY, Bar-Peled L, Chantranupong L, Zoncu R, Wang T, Kim C, Spooner E, Sabatini DM. The folliculin tumor suppressor is a GAP for the RagC/D GTPases that signal amino acid levels to mTORC1. Mol Cell 2013;52:495–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bar-Peled L, Chantranupong L, Cherniack AD, Chen WW, Ottina KA, Grabiner BC, Spear ED, Carter SL, Meyerson M, Sabatini DM. A tumor suppressor complex with GAP activity for the Rag GTPases that signal amino acid sufficiency to mTORC1. Science 2013;340:1100–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jewell JL, Russell RC, Guan KL. Amino acid signalling upstream of mTOR. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2013;14:133–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Taylor PM. Role of amino acid transporters in amino acid sensing. Am J Clin Nutr 2014;99(Suppl):223S–30S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shimobayashi M, Hall MN. Multiple amino acid sensing inputs to mTORC1. Cell Res 2016;26:7–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Saxton RA, Knockenhauer KE, Wolfson RL, Chantranupong L, Pacold ME, Wang T, Schwartz TU, Sabatini DM. Structural basis for leucine sensing by the Sestrin2-mTORC1 pathway. Science 2016;351:53–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang S, Tsun ZY, Wolfson RL, Shen K, Wyant GA, Plovanich ME, Yuan ED, Jones TD, Chantranupong L, Comb W, et al. Lysosomal amino acid transporter SLC38A9 signals arginine sufficiency to mTORC1. Science 2015;347:188–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jewell JL, Kim YC, Russell RC, Yu FX, Park HW, Plouffe SW, Tagliabracci VS, Guan KL. Differential regulation of mTORC1 by leucine and glutamine. Science 2015;347:194–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wolfson RL, Chantranupong L, Saxton RA, Shen K, Scaria SM, Cantor JR, Sabatini DM. Sestrin2 is a leucine sensor for the mTORC1 pathway. Science 2016;351:43–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Durán RV, Oppliger W, Robitaille AM, Heiserich L, Skendaj R, Gottlieb E, Hall MN. Glutaminolysis activates Rag-mTORC1 signaling. Mol Cell 2012;47:349–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kim SG, Hoffman GR, Poulogiannis G, Buel GR, Jang YJ, Lee KW, Kim BY, Erikson RL, Cantley LC, Choo AY, et al. Metabolic stress controls mTORC1 lysosomal localization and dimerization by regulating the TTT-RUVBL1/2 complex. Mol Cell 2013;49:172–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chantranupong L, Scaria SM, Saxton RA, Gygi MP, Shen K, Wyant GA, Wang T, Harper JW, Gygi SP, Sabatini DM. The CASTOR proteins are arginine sensors for the mTORC1 pathway. Cell 2016;165:153–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hara K, Yonezawa K, Weng QP, Kozlowski MT, Belham C, Avruch J. Amino acid sufficiency and mTOR regulate p70 S6 kinase and eIF-4E BP1 through a common effector mechanism. J Biol Chem 1998;273:14484–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fang Y, Vilella-Bach M, Bachmann R, Flanigan A, Chen J. Phosphatidic acid-mediated mitogenic activation of mTOR signaling. Science 2001;294:1942–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dibble CC, Cantley LC. Regulation of mTORC1 by PI3K signaling. Trends Cell Biol 2015;25:545–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tee AR, Fingar DC, Manning BD, Kwiatkowski DJ, Cantley LC, Blenis J. Tuberous sclerosis complex-1 and -2 gene products function together to inhibit mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR)-mediated downstream signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2002;99:13571–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.DeYoung MP, Horak P, Sofer A, Sgroi D, Ellisen LW. Hypoxia regulates TSC1/2-mTOR signaling and tumor suppression through REDD1-mediated 14–3-3 shuttling. Genes Dev 2008;22:239–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Inoki K, Ouyang H, Zhu T, Lindvall C, Wang Y, Zhang X, Yang Q, Bennett C, Harada Y, Stankunas K, et al. TSC2 integrates Wnt and energy signals via a coordinated phosphorylation by AMPK and GSK3 to regulate cell growth. Cell 2006;126:955–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Budanov AV, Karin M. p53 Target genes sestrin1 and sestrin2 connect genotoxic stress and mTOR signaling. Cell 2008;134:451–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dibble CC, Elis W, Menon S, Qin W, Klekota J, Asara JM, Finan PM, Kwiatkowski DJ, Murphy LO, Manning BD. TBC1D7 is a third subunit of the TSC1–TSC2 complex upstream of mTORC1. Mol Cell 2012;47:535–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dong J, Qiu H, Garcia-Barrio M, Anderson J, Hinnebusch AG. Uncharged tRNA activates GCN2 by displacing the protein kinase moiety from a bipartite tRNA-binding domain. Mol Cell 2000;6:269–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kilberg MS, Shan J, Su N. ATF4-dependent transcription mediates signaling of amino acid limitation. Trends Endocrinol Metab 2009;20:436–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ye J, Palm W, Peng M, King B, Lindsten T, Li MO, Koumenis C, Thompson CB. GCN2 sustains mTORC1 suppression upon amino acid deprivation by inducing Sestrin2. Genes Dev 2015;29:2331–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Averous J, Lambert-Langlais S, Mesclon F, Carraro V, Parry L, Jousse C, Bruhat A, Maurin AC, Pierre P, Proud CG, et al. GCN2 contributes to mTORC1 inhibition by leucine deprivation through an ATF4 independent mechanism. Sci Rep 2016;6:27698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kim JS, Ro SH, Kim M, Park HW, Semple IA, Park H, Cho US, Wang Guan KL, Karin M, Lee JH. Sestrin2 inhibits mTORC1 through modulation of GATOR complexes. Sci Rep 2015;5:9502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Han JM, Jeong SJ, Park MC, Kim G, Kwon NH, Kim HK, Ha SH, Ryu SH, Kim S. Leucyl-tRNA synthetase is an intracellular leucine sensor for the mTORC1-signaling pathway. Cell 2012;149:410–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bonfils G, Jaquenoud M, Bontron S, Ostrowicz C, Ungermann C, De Virgilio C. Leucyl-tRNA synthetase controls TORC1 via the EGO complex. Mol Cell 2012;46:105–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Magnuson B, Ekim B, Fingar DC. Regulation and function of ribosomal protein S6 kinase (S6K) within mTOR signalling networks. Biochem J 2012;441:1–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Merrick WC. eIF4F: a retrospective. J Biol Chem 2015;290:24091–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Holz MK, Ballif BA, Gygi SP, Blenis J. mTOR and S6K1 mediate assembly of the translation preinitiation complex through dynamic protein interchange and ordered phosphorylation events. Cell 2005;123:569–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wang X, Li W, Williams M, Terada N, Alessi DR, Proud CG. Regulation of elongation factor 2 kinase by p90(RSK1) and p70 S6 kinase. EMBO J 2001;20:4370–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Suzuki C, Garces RG, Edmonds KA, Hiller S, Hyberts SG, Marintchev A, Wagner G. PDCD4 inhibits translation initiation by binding to eIF4A using both its MA3 domains. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2008;105:3274–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chung J, Kuo CJ, Crabtree GR, Blenis J. Rapamycin-FKBP specifically blocks growth-dependent activation of and signaling by the 70 kd S6 protein kinases. Cell 1992;69:1227–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Richardson CJ, Bröenstrup M, Fingar DC, Jülich K, Ballif BA, Gygi S, Blenis J. SKAR is a specific target of S6 kinase 1 in cell growth control. Curr Biol 2004;14:1540–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wilson KF, Wu WJ, Cerione RA. Cdc42 stimulates RNA splicing via the S6 kinase and a novel S6 kinase target, the nuclear cap-binding complex. J Biol Chem 2000;275:37307–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Dunlop EA, Tee AR. mTOR and autophagy: a dynamic relationship governed by nutrients and energy. Semin Cell Dev Biol 2014;36:121–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Russell RC, Yuan HX, Guan KL. Autophagy regulation by nutrient signaling. Cell Res 2014;24:42–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Roczniak-Ferguson A, Petit CS, Froehlich F, Qian S, Ky J, Angarola B, Walther TC, Ferguson SM. The transcription factor TFEB links mTORC1 signaling to transcriptional control of lysosome homeostasis. Sci Signal 2012;5:ra42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lamming DW, Sabatini DM. A central role for mTOR in lipid homeostasis. Cell Metab 2013;18:465–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Porstmann T, Santos CR, Griffiths B, Cully M, Wu M, Leevers S, Griffiths JR, Chung YL, Schulze A. SREBP activity is regulated by mTORC1 and contributes to Akt-dependent cell growth. Cell Metab 2008;8:224–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Düvel K, Yecies JL, Menon S, Raman P, Lipovsky AI, Souza AL, Triantafellow E, Ma Q, Gorski R, Cleaver S, et al. Activation of a metabolic gene regulatory network downstream of mTOR complex 1. Mol Cell 2010;39:171–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Peterson TR, Sengupta SS, Harris TE, Carmack AE, Kang SA, Balderas E, Guertin DA, Madden KL, Carpenter AE, Finck BN, et al. mTOR complex 1 regulates lipin 1 localization to control the SREBP pathway. Cell 2011;146:408–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sengupta S, Peterson TR, Laplante M, Oh S, Sabatini DM. mTORC1 controls fasting-induced ketogenesis and its modulation by ageing. Nature 2010;468:1100–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kim K, Pyo S, Um SH. S6 kinase 2 deficiency enhances ketone body production and increases peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha activity in the liver. Hepatology 2012;55:1727–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Robitaille AM, Christen S, Shimobayashi M, Cornu M, Fava LL, Moes S, Prescianotto-Baschong C, Sauer U, Jenoe P, Hall MN. Quantitative phosphoproteomics reveal mTORC1 activates de novo pyrimidine synthesis. Science 2013;339:1320–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ben-Sahra I, Howell JJ, Asara JM, Manning BD. Stimulation of de novo pyrimidine synthesis by growth signaling through mTOR and S6K1. Science 2013;339:1323–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Cargnello M, Tcherkezian J, Roux PP. The expanding role of mTOR in cancer cell growth and proliferation. Mutagenesis 2015;30:169–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Mendelsohn AR, Larrick JW. Dissecting mammalian target of rapamycin to promote longevity. Rejuvenation Res 2012;15:334–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Mackie EJ, Tatarczuch L, Mirams M. The skeleton: a multi-functional complex organ: the growth plate chondrocyte and endochondral ossification. J Endocrinol 2011;211:109–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Baron J, Sävendahl L, De Luca F, Dauber A, Phillip M, Wit JM, Nilsson O. Short and tall stature: a new paradigm emerges. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2015;11:735–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Phornphutkul C, Wu KY, Auyeung V, Chen Q, Gruppuso PA. mTOR signaling contributes to chondrocyte differentiation. Dev Dyn 2008;237:702–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Chen J, Long F. mTORC1 signaling controls mammalian skeletal growth through stimulation of protein synthesis. Development 2014;141:2848–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Li C, Wang Q, Wang JF. Transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) induces the expression of chondrogenesis-related genes through TGF-β receptor II (TGFRII)-AKT-mTOR signaling in primary cultured mouse precartilaginous stem cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2014;450:646–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kim MS, Wu KY, Auyeung V, Chen Q, Gruppuso PA, Phornphutkul C. Leucine restriction inhibits chondrocyte proliferation and differentiation through mechanisms both dependent and independent of mTOR signaling. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2009;296:E1374–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Phornphutkul C, Lee M, Voigt C, Wu KY, Ehrlich MG, Gruppuso PA, Chen Q. The effect of rapamycin on bone growth in rabbits. J Orthop Res 2009;27:1157–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Chen J, Long F. mTORC1 signaling promotes osteoblast differentiation from preosteoblasts. PLoS One 2015;10:e0130627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Chen J, Tu X, Esen E, Joeng KS, Lin C, Arbeit JM, Rüegg MA, Hall MN, Ma L, Long F. WNT7B promotes bone formation in part through mTORC1. PLoS Genet 2014;10:e1004145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Goodman CA, Hornberger TA, Robling AG. Bone and skeletal muscle: key players in mechanotransduction and potential overlapping mechanisms. Bone 2015;80:24–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.You JS, Lincoln HC, Kim CR, Frey JW, Goodman CA, Zhong XP, Hornberger TA. The role of diacylglycerol kinase ζ and phosphatidic acid in the mechanical activation of mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling and skeletal muscle hypertrophy. J Biol Chem 2014;289:1551–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Ham DJ, Caldow MK, Lynch GS, Koopman R. Leucine as a treatment for muscle wasting: a critical review. Clin Nutr 2014;33:937–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Sato T, Ito Y, Nagasawa T. Dietary L-lysine suppresses autophagic proteolysis and stimulates Akt/mTOR signaling in the skeletal muscle of rats fed a low-protein diet. J Agric Food Chem 2015;63:8192–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Dukes A, Davis C, El Refaey M, Upadhyay S, Mork S, Arounleut P, Johnson MH, Hill WD, Isales CM, Hamrick MW. The aromatic amino acid tryptophan stimulates skeletal muscle IGF1/p70s6k/mTor signaling in vivo and the expression of myogenic genes in vitro. Nutrition 2015;31:1018–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Manjarín R, Columbus DA, Suryawan A, Nguyen HV, Hernandez-García AD, Hoang NM, Fiorotto ML, Davis T. Leucine supplementation of a chronically restricted protein and energy diet enhances mTOR pathway activation but not muscle protein synthesis in neonatal pigs. Amino Acids 2016;48:257–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Wahl SE, McLane LE, Bercury KK, Macklin WB, Wood TL. Mammalian target of rapamycin promotes oligodendrocyte differentiation, initiation and extent of CNS myelination. J Neurosci 2014;34:4453–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Lebrun-Julien F, Bachmann L, Norrmén C, Trötzmüller M, Köfeler H, Rüegg MA, Hall MN, Suter U. Balanced mTORC1 activity in oligodendrocytes is required for accurate CNS myelination. J Neurosci 2014;34:8432–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Norrmén C, Figlia G, Lebrun-Julien F, Pereira JA, Trötzmüller M, Köfeler HC, Rantanen V, Wessig C, van Deijk AL, Smit AB, et al. mTORC1 controls PNS myelination along the mTORC1-RXR -SREBP-lipid biosynthesis axis in Schwann cells. Cell Reports 2014;9:646–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Clevers H. The intestinal crypt, a prototype stem cell compartment. Cell 2013;154:274–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Vooijs M, Liu Z, Kopan R. Notch: architect, landscaper, and guardian of the intestine. Gastroenterology 2011;141:448–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Richmond CA, Shah MS, Deary LT, Trotier DC, Thomas H, Ambruzs DM, Jiang L, Whiles BB, Rickner HD, Montgomery RK, et al. Dormant intestinal stem cells are regulated by PTEN and nutritional status. Cell Reports 2015;13:2403–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Zhou Y, Wang Q, Weiss HL, Evers BM. Nuclear factor of activated T-cells 5 increases intestinal goblet cell differentiation through an mTOR/Notch signaling pathway. Mol Biol Cell 2014;25:2882–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Zhou Y, Rychahou P, Wang Q, Weiss HL, Evers BM. TSC2/mTORC1 signaling controls Paneth and goblet cell differentiation in the intestinal epithelium. Cell Death Dis 2015;6:e1631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Guan Y, Zhang L, Li X, Zhang X, Liu S, Gao N, Li L, Gao G, Wei G, Chen Z, et al. Repression of mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 inhibits intestinal regeneration in acute inflammatory bowel disease models. J Immunol 2015;195:339–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Sampson LL, Davis AK, Grogg MW, Zheng Y. mTOR disruption causes intestinal epithelial cell defects and intestinal atrophy postinjury in mice. FASEB J 2016;30:1263–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Wang H, Ji Y, Wu G, Sun K, Sun Y, Li W, Wang B, He B, Zhang Q, Dai Z, et al. L-tryptophan activates mammalian target of rapamycin and enhances expression of tight junction proteins in intestinal porcine epithelial cells. J Nutr 2015;145:1156–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Chen C, Liu Y, Liu R, Ikenoue T, Guan KL, Liu Y, Zheng P. TSC-mTOR maintains quiescence and function of hematopoietic stem cells by repressing mitochondrial biogenesis and reactive oxygen species. J Exp Med 2008;205:2397–408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Kalaitzidis D, Sykes SM, Wang Z, Punt N, Tang Y, Ragu C, Sinha AU, Lane SW, Souza AL, Clish CB, et al. mTOR complex 1 plays critical roles in hematopoiesis and Pten-loss-evoked leukemogenesis. Cell Stem Cell 2012;11:429–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Knight ZA, Schmidt SF, Birsoy K, Tan K, Friedman JM. A critical role for mTORC1 in erythropoiesis and anemia. eLife 2014;3:e01913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Chung J, Bauer DE, Ghamari A, Nizzi CP, Deck KM, Kingsley PD, Yien YY, Huston NC, Chen C, Schultz IJ, et al. The mTORC1/4E-BP pathway coordinates hemoglobin production with L-leucine availability. Sci Signal 2015;8:ra34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Muckenthaler MU, Galy B, Hentze MW. Systemic iron homeostasis and the iron-responsive element/iron-regulatory protein (IRE/IRP) regulatory network. Annu Rev Nutr 2008;28:197–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Ganz T, Nemeth E. Hepcidin and iron homeostasis. Biochim Biophys Acta 2012;1823:1434–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Bayeva M, Khechaduri A, Puig S, Chang HC, Patial S, Blackshear PJ, Ardehali H. mTOR regulates cellular iron homeostasis through tristetraprolin. Cell Metab 2012;16:645–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Guan P, Wang N. Mammalian target of rapamycin coordinates iron metabolism with iron-sulfur cluster assembly enzyme and tristetraprolin. Nutrition 2014;30:968–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Delgoffe GM, Pollizzi KN, Waickman AT, Heikamp E, Meyers DJ, Horton MR, Xiao B, Worley PF, Powell JD. The kinase mTOR regulates the differentiation of helper T cells through the selective activation of signaling by mTORC1 and mTORC2. Nat Immunol 2011;12:295–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Pollizzi KN, Patel CH, Sun IH, Oh MH, Waickman AT, Wen J, Delgoffe GM, Powell JD. mTORC1 and mTORC2 selectively regulate CD8+ T cell differentiation. J Clin Invest 2015;125:2090–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Marçais A, Cherfils-Vicini J, Viant C, Degouve S, Viel S, Fenis A, Rabilloud J, Mayol K, Tavares A, Bienvenu J, et al. The metabolic checkpoint kinase mTOR is essential for IL-15 signaling during the development and activation of NK cells. Nat Immunol 2014;15:749–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Lee K, Heffington L, Jellusova J, Nam KT, Raybuck A, Cho SH, Thomas JW, Rickert RC, Boothby M. Requirement for Rictor in homeostasis and function of mature B lymphoid cells. Blood 2013;122:2369–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Zhang Y, Hu T, Hua C, Gu J, Zhang L, Hao S, Liang H, Wang X, Wang W, Xu J, et al. Rictor is required for early B cell development in bone marrow. PLoS One 2014;9:e103970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Keating R, Hertz T, Wehenkel M, Harris TL, Edwards BA, McClaren JL, Brown SA, Surman S, Wilson ZS, Bradley P, et al. The kinase mTOR modulates the antibody response to provide cross-protective immunity to lethal infection with influenza virus. Nat Immunol 2013;14:1266–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Lui JC, Garrison P, Baron J. Regulation of body growth. Curr Opin Pediatr 2015;27:502–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Meng Z, Moroishi T, Guan KL. Mechanisms of Hippo pathway regulation. Genes Dev 2016;30:1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Hansen CG, Ng YL, Lam WL, Plouffe SW, Guan KL. The Hippo pathway effectors YAP and TAZ promote cell growth by modulating amino acid signaling to mTORC1. Cell Res 2015;25:1299–313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Rose WC, Oesterling MJ, Womack M. Comparative growth on diets containing ten and nineteen amino acids, with further observations upon the role of glutamic and aspartic acids. J Biol Chem 1948;176:753–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Irwin MI, Hegsted DM. A conspectus of research on amino acid requirements of man. J Nutr 1971;101:539–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Sanfilippo S, Imbesi RM, Sanfilippo S Jr. Effects of a tryptophan deficient diet on the morphology of skeletal muscle fibers of the rat: preliminary observations at neuroendocrinological and submicroscopical levels. Ital J Anat Embryol 1995;100(Suppl 1):131–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Imbesi R, Mazzone V, Castrogiovanni P. Is tryptophan ‘more’ essential than other essential amino acids in development? A morphologic study. Anat Histol Embryol 2009;38:361–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.González EM, Penedo LA, Oliveira-Silva P, Campello-Costa P, Guedes RC, Serfaty CA. Neonatal tryptophan dietary restriction alters development of retinotectal projections in rats. Exp Neurol 2008;211:441–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Penedo LA, Oliveira-Silva P, Gonzalez EM, Maciel R, Jurgilas PB, Melibeu Ada C, Campello-Costa P, Serfaty CA. Nutritional tryptophan restriction impairs plasticity of retinotectal axons during the critical period. Exp Neurol 2009;217:108–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Zhang L, Guadarrama L, Corona-Morales AA, Vega-Gonzalez A, Rocha L, Escobar A. Rats subjected to extended L-tryptophan restriction during early postnatal stage exhibit anxious-depressive features and structural changes. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 2006;65:562–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Zhang L, Corona-Morales AA, Vega-González A, García-Estrada J, Escobar A. Dietary tryptophan restriction in rats triggers astrocyte cytoskeletal hypertrophy in hippocampus and amygdala. Neurosci Lett 2009;450:242–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Anthony TG, McDaniel BJ, Byerley RL, McGrath BC, Cavener DR, McNurlan MA, Wek RC. Preservation of liver protein synthesis during dietary leucine deprivation occurs at the expense of skeletal muscle mass in mice deleted for eIF2 kinase GCN2. J Biol Chem 2004;279:36553–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Guo F, Cavener DR. The GCN2 eIF2alpha kinase regulates fatty-acid homeostasis in the liver during deprivation of an essential amino acid. Cell Metab 2007;5:103–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Cheng Y, Meng Q, Wang C, Li H, Huang Z, Chen S, Xiao F, Guo F. Leucine deprivation decreases fat mass by stimulation of lipolysis in white adipose tissue and upregulation of uncoupling protein 1 (UCP1) in brown adipose tissue. Diabetes 2010;59:17–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Xiao F, Huang Z, Li H, Yu J, Wang C, Chen S, Meng Q, Cheng Y, Gao X, Li J, et al. Leucine deprivation increases hepatic insulin sensitivity via GCN2/mTOR/S6K1 and AMPK pathways. Diabetes 2011;60:746–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Xiao F, Yu J, Guo Y, Deng J, Li K, Du Y, Chen S, Zhu J, Sheng H, Guo F. Effects of individual branched-chain amino acids deprivation on insulin sensitivity and glucose metabolism in mice. Metabolism 2014;63:841–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Du Y, Meng Q, Zhang Q, Guo F. Isoleucine or valine deprivation stimulates fat loss via increasing energy expenditure and regulating lipid metabolism in WAT. Amino Acids 2012;43:725–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Tamaki N, Tsunemori F, Wakabayashi M, Hama T. Effect of histidine-free and -excess diets on anserine and carnosine contents in rat gastrocnemius muscle. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol (Tokyo) 1977;23:331–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Clemens RA, Kopple JD, Swendseid ME. Metabolic effects of histidine-deficient diets fed to growing rats by gastric tube. J Nutr 1984;114:2138–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Parker CJ Jr, Riess GT, Sardesai VM. Essentiality of histidine in adult mice. J Nutr 1985;115:824–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Faure M, Moënnoz D, Montigon F, Mettraux C, Breuillé D, Ballèvre O. Dietary threonine restriction specifically reduces intestinal mucin synthesis in rats. J Nutr 2005;135:486–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Law GK, Bertolo RF, Adjiri-Awere A, Pencharz PB, Ball RO. Adequate oral threonine is critical for mucin production and gut function in neonatal piglets. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2007;292:G1293–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Hamard A, Sève B, Le Floc’h N. Intestinal development and growth performance of early-weaned piglets fed a low-threonine diet. Animal 2007;1:1134–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Hamard A, Sève B, Le Floc’h N. A moderate threonine deficiency differently affects protein metabolism in tissues of early-weaned piglets. Comp Biochem Physiol A Mol Integr Physiol 2009;152:491–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Hamard A, Mazurais D, Boudry G, Le Huërou-Luron I, Sève B, Le Floc’h N. A moderate threonine deficiency affects gene expression profile, paracellular permeability and glucose absorption capacity in the ileum of piglets. J Nutr Biochem 2010;21:914–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Wang X, Qiao S, Yin Y, Yue L, Wang Z, Wu G. A deficiency or excess of dietary threonine reduces protein synthesis in jejunum and skeletal muscle of young pigs. J Nutr 2007;137:1442–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Yang YX, Guo J, Jin Z, Yoon SY, Choi JY, Wang MH, Piao XS, Kim BW, Chae BJ. Lysine restriction and realimentation affected growth, blood profiles and expression of genes related to protein and fat metabolism in weaned pigs. J Anim Physiol Anim Nutr (Berl) 2009;93:732–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Ishida A, Kyoya T, Nakashima K, Katsumata M. Muscle protein metabolism during compensatory growth with changing dietary lysine levels from deficient to sufficient in growing rats. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol (Tokyo) 2011;57:401–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Kobayashi H, Ishida A, Ashihara A, Nakashima K, Katsumata M. Effects of dietary low level of threonine and lysine on the accumulation of intramuscular fat in porcine muscle. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 2012;76:2347–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Kim J, Lee KS, Kwon DH, Bong JJ, Jeong JY, Nam YS, Lee MS, Liu X, Baik M. Severe dietary lysine restriction affects growth and body composition and hepatic gene expression for nitrogen metabolism in growing rats. J Anim Physiol Anim Nutr (Berl) 2014;98:149–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Anthony TG, Reiter AK, Anthony JC, Kimball SR, Jefferson LS. Deficiency of dietary EAA preferentially inhibits mRNA translation of ribosomal proteins in liver of meal-fed rats. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2001;281:E430–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153. WHO/FAO/United Nations University. Protein and amino acid requirements in human nutrition. Report of a Joint WHO/FAO/UNU Expert Consultation. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser 2007;1–265. [PubMed]

- 154.Pillai RR, Kurpad AV. Amino acid requirements in children and the elderly population. Br J Nutr 2012;108(Suppl 2):S44–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Reeds PJ, Garlick PJ. Protein and amino acid requirements and the composition of complementary foods. J Nutr 2003;133:2953S–61S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Uauy R. Rethinking protein. Food Nutr Bull 2013;34:228–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Pillai RR, Elango R, Ball RO, Kurpad AV, Pencharz PB. Lysine requirements of moderately undernourished school-aged Indian children are reduced by treatment for intestinal parasites as measured by the indicator amino acid oxidation technique. J Nutr 2015;145:954–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Millward DJ, Jackson AA. Protein requirements and the indicator amino acid oxidation method. Am J Clin Nutr 2012;95:1498–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Elango R, Ball RO, Pencharz PB. Indicator amino acid oxidation: concept and application. J Nutr 2008;138:243–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Rand WM, Pellett PL, Young VR. Meta-analysis of nitrogen balance studies for estimating protein requirements in healthy adults. Am J Clin Nutr 2003;77:109–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161.Delgoffe GM, Powell JD. Feeding an army: the metabolism of T cells in activation, anergy, and exhaustion. Mol Immunol 2015;68(2 Pt C):492–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162.Kampman-van de Hoek E, Jansman AJ, van den Borne JJ, van der Peet-Schwering CM, van Beers-Schreurs H, Gerrits WJ. Dietary amino acid deficiency reduces the utilization of amino acids for growth in growing pigs after a period of poor health. J Nutr 2016;146:51–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 163.Tomé D, Jahoor F, Kurpad A, Michaelsen KF, Pencharz P, Slater C, Weisell R. Current issues in determining dietary protein quality and metabolic utilization. Eur J Clin Nutr 2014;68:537–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 164.Schaafsma G. The protein digestibility-corrected amino acid score. J Nutr 2000;130:1865S–7S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 165.Food and Agriculture Organization. Dietary protein quality evaluation in human nutrition: report of an FAO Expert Consultation. Rome (Italy): FAO; 2013. FAO Food and Nutrition Paper No.: 92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 166.Dror DK, Allen LH. The importance of milk and other animal-source foods for children in low-income countries. Food Nutr Bull 2011;32:227–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 167.Krebs NF, Mazariegos M, Tshefu A, Bose C, Sami N, Chomba E, Carlo W, Goco N, Kindem M, Wright LL, et al. ; Complementary Feeding Study Group. Meat consumption is associated with less stunting among toddlers in four diverse low-income settings. Food Nutr Bull 2011;32:185–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 168.Schönbeck Y, Talma H, van Dommelen P, Bakker B, Buitendijk SE, HiraSing RA, van Buuren S. The world’s tallest nation has stopped growing taller: the height of Dutch children from 1955 to 2009. Pediatr Res 2013;73:371–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 169.Stulp G, Barrett L, Tropf FC, Mills M. Does natural selection favour taller stature among the tallest people on earth? Proc Biol Sci 2015;282:20150211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]