Abstract

A 24-year-old otherwise healthy man presented with a 3-week history of malaise, headache, fever and rigors after he was treated with oral clindamycin for left parotitis and Gemella haemolysans bacteraemia. He developed G. haemolysans infective endocarditis, septic emboli and heart failure due to progressive bivalvular disease. He underwent urgent mechanical aortic valve replacement and mitral valve repair, which required venovenous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, to support severe respiratory failure. This is the first documented case of G. haemolysans infective endocarditis affecting native aortic and mitral valves in a healthy adult.

Background

Gemella haemolysans is a Gram-positive coccus related to the family Streptococcaceae. This usually commensal bacterium can be found in the human oral cavity as well as the respiratory, gastrointestinal and genitourinary tracts. Gemella has been detected in the oral cavity of up to 30% of young healthy people.1 Though rare, serious systemic infections such as infective endocarditis are reported. In fact, only 24 cases have been reported in the literature.2–6 Poor dentition, dental infection and dental manipulation are risk factors for infective endocarditis due to oral flora gaining access to the bloodstream. Our patient presented with acute parotitis caused by carious tooth abscess and necrosis, leading to Gemella bacteraemia and infective endocarditis. We report the first documented case of G. haemolysans infective endocarditis involving native mitral and aortic valves in an immunocompetent patient who required urgent aortic valve replacement, mitral valve repair and venovenous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (VV-ECMO).

Case presentation

The patient was a 24-year-old previously healthy Tongan American man who visited another hospital with a symptom of left jaw pain for 2 days. Initial workup revealed leucocytosis, 20×105/µL, and left parotitis on CT of the neck. He was treated and discharged from the emergency department (ED) with a 10-day course of oral clindamycin. Two days after the first visit, G. haemolysans was isolated from blood cultures. Consequently, he was asked to return to the ED for re-evaluation. At that time, he was found to have improved symptoms and more blood cultures were sent.

The repeat cultures returned in 2 days sterile. He was instructed by the ED to follow-up with his primary care physician in the next 1–2 days. Despite being born and raised in the USA, the patient lacked medical insurance coverage. As an adult, he never established primary medical care and was unable to do so when needed after his second ED encounter. Three weeks following his initial ED visit, the patient presented to our hospital with 10 days of progressive malaise, headache, fever and rigors. He denied the use of intravenous drugs. He also denied alcohol and tobacco use.

His vital signs were body temperature of 101.8°F (38.8°C), respiratory rate of 24 breaths/min, heart rate of 128 bpm and blood pressure of 144/51 mm Hg. Oxygen saturation was 97% while breathing room air. He was moderately distressed due to rigors. Head and neck examinations revealed conjunctival pallor and poor dentition. Cardiovascular examination showed jugular venous distension 5 cm above the sternal angle at 30°, an early systolic murmur at the apex, a soft decrescendo diastolic murmur throughout the precordium and an S3 sound. There was no peripheral oedema. Neurological examination revealed mild left-sided facial weakness, mild lower left extremity weakness and a left-sided neglect. There were no mucocutaneous lesions, Roth spots, petechiae, Osler nodes, Janeway lesions or subungual haemorrhages.

Investigations

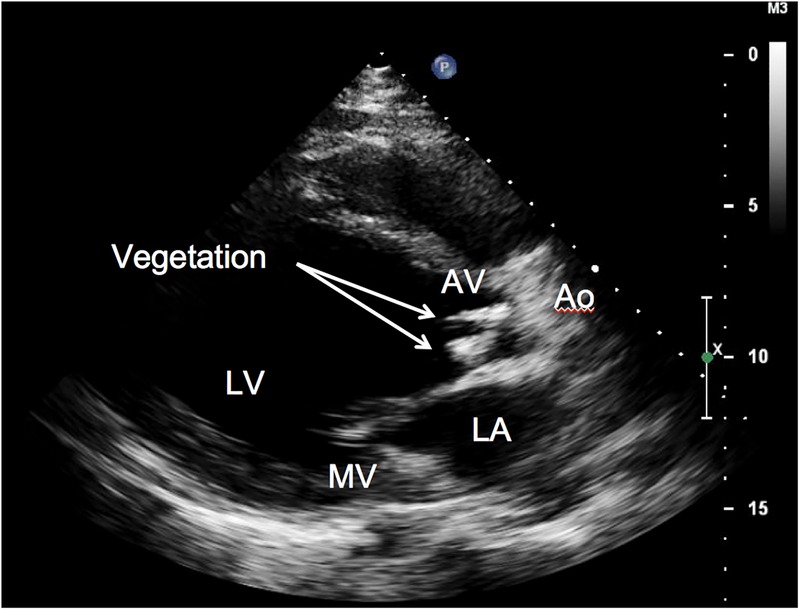

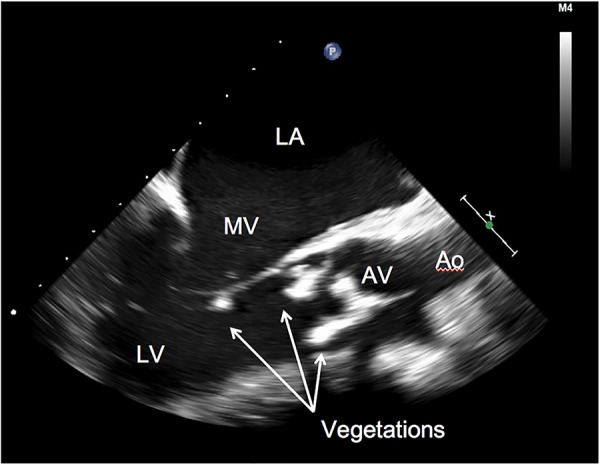

His white cell count was elevated at 15.5×103/µL. A chest radiograph revealed a markedly enlarged cardiac silhouette without lung infiltrates. An ECG showed sinus tachycardia at a rate of 133 bpm. No heart blocks were seen. A CT scan of the brain showed peripheral areas of enhancement along the posterior right temporal and parietal lobes with minimal mass effect. Dental radiographs revealed a carious fracture of tooth number 32 with pulpal necrosis and acute abscess. Within 24 hours, two sets of blood cultures were positive for G. haemolysans. An additional three sets of blood cultures were also positive for G. haemolysans. MRI of the brain showed moderate-to-large subacute infarcts in the right temporal and right parietal lobes, as well as tiny infarcts involving the right cerebellum and left high lateral frontal lobe. A transthoracic echocardiogram showed an ejection fraction of 25–30%, two large aortic valve vegetations resulting in severe aortic regurgitation and a prominent thickening of the posterior aspect of the mitral annulus causing mild-to-moderate mitral regurgitation (figure 1). A trans-oesophageal echocardiogram revealed a mitral valve vegetation on the posterior leaflet (figure 2).

Figure 1.

Transthoracic echocardiogram, parasternal long-axis view. The moderately dilated left atrium followed by the large left ventricle ejects into the ascending aorta. There are two thick, echodense linear strands (arrows) on the ventricular side of the aortic valve and thickened mitral valve with more prominent thickening on the posterior aspect of the annulus.

Figure 2.

Transoesophageal echocardiogram before surgical intervention. There are two elongated, echodense masses on the ventricular side of the aortic valve. Softer appearing density on the tip of the posterior leaflet of the mitral valve was also seen (arrows). Ao, ascending aorta; AV, aortic valve; LA, left atrium; LV, left ventricle; MV, mitral valve.

Treatment

The patient was admitted for presumed infective endocarditis, septic cerebral emboli and heart failure.

Intravenous penicillin G and vancomycin were administered. He underwent tooth extraction as source control of the infection. Given his progressive heart failure, he underwent urgent mechanical aortic valve replacement and mitral valve repair on the fifth day. Intraoperatively, he developed cardiac arrest secondary to cardiogenic shock with severe respiratory failure, requiring VV-ECMO. After VV-ECMO was started, he developed coagulopathy with a prothrombin time of 22.6 s, international normalised ratio of 2.1 and platelet count of 44×103/µL. There was no evidence of disseminated intravascular coagulation. A complication of the cardiac surgery was a right-sided haemothorax with uncontrolled bleeding. He required transfusion of 22 units of packed red cells within 24 hours. During exploratory surgery for the hemothorax, the bleeding source was identified as an oozing aortotomy suture, which was subsequently repaired. His course of treatment was also complicated by acute kidney injury and hyperkalemia requiring continuous venovenous haemodialysis. His condition improved and VV-ECMO was discontinued after 2 days.

Outcome and follow-up

After a prolonged hospitalisation, the patient was discharged with lifelong warfarin and intravenous ceftriaxone for a total of 7 weeks. At the time of discharge, his renal function recovered completely. He still had persistent left-sided neglect, but improved left-sided facial and left lower extremity weakness. He has been taking anticoagulants and following up with established primary care, infectious disease, cardiology and anticoagulation clinics since discharge.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first documented case of G. haemolysans infective endocarditis affecting native aortic and mitral valves in an otherwise healthy adult. We found a similar case requiring VV-ECMO, with an artificial heart as a bridge to transplantation, but it involved a prosthetic valve.6 We witnessed rapidly progressive infective endocarditis with septic emboli and heart failure due to G. haemolysans. According to the 2014 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines for the management of patients with valvular heart disease, progressive septic emboli and heart failure are surgical indications for infective endocarditis.7 However, in practice, the severity and frequency of complications while receiving intravenous antibiotics often dictate the procession to and timing of surgical intervention. His presentation required urgent aortic and mitral valve intervention. His course was also complicated by cardiogenic shock, cardiac arrest and severe respiratory failure, which required VV-ECMO, and uncontrolled hemothorax with coagulopathy requiring re-exploration and ligation of an oozing vascular suture.

In most cases of G. haemolysans infection, the host has an underlying condition such as an immunocompromised state, cancer, structural heart disease or autoimmune disease.5 Poor dentition, usually accompanying an additional risk factor such as a valvular disorder, is also considered a risk factor.8 Most cases of G. haemolysans endocarditis involve either the mitral or aortic valve and are found in patients with previous valve damage or those in an immunocompromised state. In this case, the patient developed a dental infection with tooth abscess, which led to parotitis, followed by bacteraemia and infective endocarditis. He was given a 10-day course of oral clindamycin when parotitis was diagnosed. The patient also lacked primary care follow-up and health insurance.

This case also illustrates the importance of a complete examination of the oral cavity and dental radiographs in a patient presenting with systemic symptoms of infection and reporting pain in the periodontal region. Although a rare pathogen to cause endocarditis, Gemella should be treated aggressively with early intravenous antibiotics to avoid serious complications. Adequate access to healthcare and appropriate follow-up is also of great importance.

Learning points.

Venovenous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, in the setting of surgical intervention for infective endocarditis with rapid multiorgan failure, successfully saved the life of our patient and should be considered in similar patients.

Always consider early surgical treatment for patients with infective endocarditis who present with overt heart failure.

Although rare, Gemella haemolysans infective endocarditis can be seen in healthy, immunocompetent patients, particularly those with dental infections.

Early infectious source control, such as dental extraction, and early intravenous antibiotic therapy for G. haemolysans bacteraemia may prevent the unfortunate deterioration to endocarditis, septic embolism and heart failure as seen in our patient.

Poor access to primary healthcare is a serious issue for uninsured patients in the USA and contributes to poor prognosis.

Acknowledgments

The authors sincerely thank Dr Leslie Ito, the cardiothoracic surgeon on the case, whose extraordinary surgical efforts led to a very good outcome.

Footnotes

Contributors: AA and JK wrote the article under the guidance of DTBJ who edited and revised the manuscript considerably. HC provided assistance and expertise with the infectious disease aspects of the case.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Berger U. Prevalence of Gemella haemolysans on the pharyngeal mucosa of man. Med Microbiol Immunol 1985;174:267–74. 10.1007/BF02124811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Avgoustidis N, Bourantas CV, Anastasiadis GP et al. Endocarditis due to Gemella haemolysans in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Heart Valve Dis 2011;20:107–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kovaleva J, Gerhards LG, Möller AV. Endocarditis caused by rare Gram-positive bacteria: investigate for gastrointestinal disorders. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd 2012;156:A4445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Quaesaet L, Jaffuel S, Garo B et al. Gemella haemolysans endocarditis in a patient with a bioprosthetic aortic valve. Med Mal Infect 2016;46:61–3. 10.1016/j.medmal.2015.11.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Khan R, Urban C, Rubin D et al. Subacute endocarditis caused by Gemella haemolysans and a review of the literature. Scand J Infect Dis 2004;36:885–8. 10.1080/00365540410024916 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ramchandani MS, Rakita RM, Freeman RV et al. Total artificial heart as bridge to transplantation for severe culture-negative prosthetic valve endocarditis due to Gemella haemolysans. ASAIO J 2014;60:479–81. 10.1097/MAT.0000000000000080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nishimura RA, Otto CM, Bonow RO. 2014 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. JACC 2014;148:e1–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wilson W, Taubert KA, Gewitz M et al. American Heart Association Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis, and Kawasaki Disease Committee; American Heart Association Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young; American Heart Association Council on Clinical Cardiology. Prevention of infective endocarditis guidelines from the American Heart Association: a guideline from the American Heart Association Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis, and Kawasaki Disease Committee, Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, and the Council on Clinical Cardiology, Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia, and the Quality of Care and Outcomes Research Interdisciplinary Working Group. Circulation 2007;116:1736–54. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.183095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]