Abstract

Use of the immune checkpoint inhibitors, ipilimumab and nivolumab, has revolutionised treatment in patients with metastatic melanoma. However, these drugs can cause an autoimmune enterocolitis, with diarrhoea as the presenting symptom. This is conventionally managed by prompt institution of corticosteroid therapy if moderate diarrhoea (3–6 times/day; grade 2) is present for >5 days or if diarrhoea is severe (>6 times/day; grade 3). We report a case of steroid-dependent ipilimumab-induced colitis successfully treated with vedolizumab (an inhibitor of memory T-cell trafficking to the gut), after which complete withdrawal of corticosteroid was achieved. Hence, vedolizumab warrants further evaluation as a potential novel treatment of ipilimumab-induced colitis.

Background

Ipilimumab, an anti-cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen 4 (anti-CTLA-4) inhibitor, and nivolumab, an anti-programmed death 1 (anti-PD-1) inhibitor, are immune checkpoint inhibitors with proven antitumour efficacy in advanced melanoma via enhancement of T-cell function.1–4 This enhanced T-cell activity can produce various organ-specific immune-related adverse events (irAEs), including enterocolitis, which is encountered in 18–44% of patients treated with ipilimumab and ≤18% with nivolumab.5 Severe diarrhoea (>6 times/day; grade 3) occurs in 10% and 1% of ipilimumab-treated and nivolumab-treated patients, respectively, and necessitates high-dose steroid therapy. When a patient is systemically unwell with colitis, has inadequate control of diarrhoea or becomes steroid dependent, infliximab (a tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) inhibitor is often used. However, infliximab is used with varying degrees of success, and colectomy and/or death have/has been reported.6 Notably, as infliximab has a systemic effect, it may add to the risk of infection in patients already receiving high-dose corticosteroid. Moreover, there is a theoretical risk of tumour progression as infliximab's systemic mechanism of action suppresses T-cell activation, perhaps negating the benefit of immune checkpoint inhibitors.

Case presentation

We report a 69-year-old man who is an ex-smoker. He has body mass index of 34. He was diagnosed with melanoma in 1989. This was resected. Since that time, he experienced multiple recurrences with repeated resections. Intercurrent medical history included gastro-oesophageal reflux disease, obstructive sleep apnoea, hypertension, hypercholesterolaemia and diverticular disease with no relevant family history of cancer. On routine review in June 2015, he was documented to have stage 3B resectable (pT2aN1bM0) K601E BRAF-mutant cutaneous melanoma with palpable nodal metastases in the left neck and axilla. His measurable disease was removed with left axillary node dissection and left parotidectomy. He was referred to the Royal Adelaide Hospital for consideration of the Checkmate-238 randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial (NCT02388906) of nivolumab versus ipilimumab for prevention of recurrence after complete resection of stage 3B/C or 4 melanoma.

The patient was started on study treatment on 28 August 2015. He had received the third dose of study treatment on 9 October (week 8) when he had an abrupt onset of mild (<3 times/day; grade 1) non-bloody diarrhoea. This progressed to grade 2 diarrhoea (3–6 times/day) by week 9. At the time of evident right-sided submental and biopsy-confirmed nodal recurrence of his melanoma, the patient's treatment allocation was unblinded. This revealed to be ipilimumab at 10 mg/kg intravenously, at three weekly intervals. Stool microscopy sent at the time was negative for enteric pathogens, including Clostridium difficile. The patient was, thus, diagnosed with ipilimumab-induced colitis, and ipilimumab was discontinued.

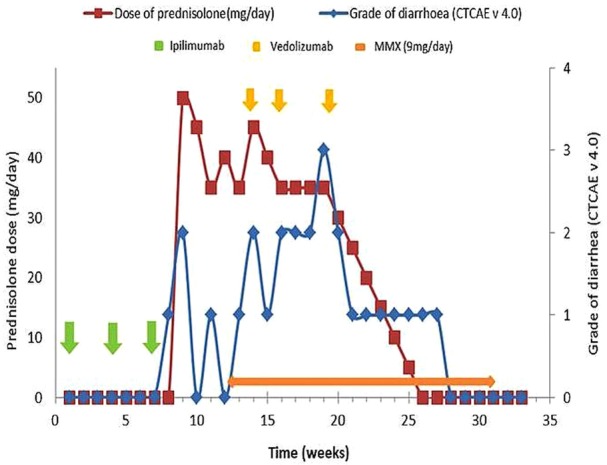

He was started on oral prednisolone 0.5 mg/kg/day on 23 October, with resolution of symptoms within 5 days (figure 1). It was planned to wean the prednisolone by 5 mg/day each week. Multiple attempts of steroid weaning failed, with recurrent problematic diarrhoea each time the dose went below 35 mg/day. On high-dose steroid, his faecal calprotectin was 34 µg/g (reference range: <50 µg/g) and serum C reactive protein was 14 mg/L (reference range: <8 mg/L). Oral budesonide (MMX), formulated to release the active drug in the colon, was added at a dose of 9 mg/day at week 12 in an attempt to wean and cease his prednisolone dose. However, despite this, no benefit was noted. Treatment escalation was therefore considered to maintain symptomatic control while allowing steroid withdrawal. During this same time period, isolated disease progression in a right-sided submental lymph node was clinically palpable and confirmed on a whole-body FDG-PET/CT scan and fine needle aspiration cytology. Since the systemic effects of infliximab were of major concern, we considered treatment with vedolizumab instead. Vedolizumab is documented to have efficacy in colitis and acts in a site-specific way to prevent memory T-cell trafficking into the gut.

Figure 1.

Diagram showing timing of treatment and severity of diarrhoea. MMX, oral budesonide.

Treatment

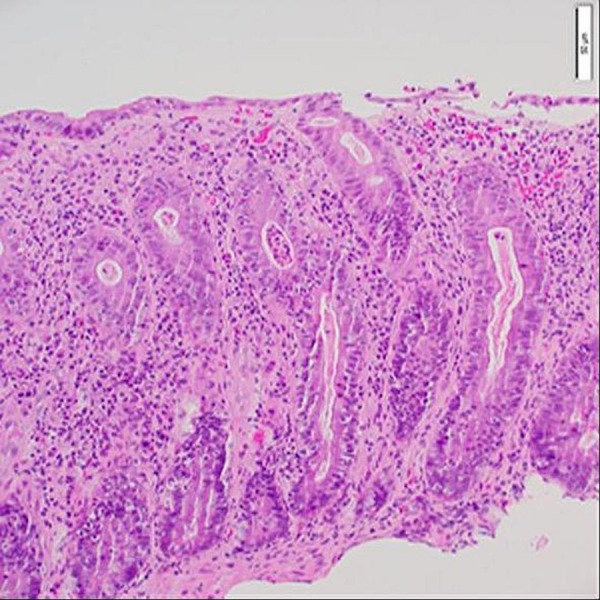

The patient was given standard induction therapy with vedolizumab, 300 mg intravenously at weeks 0, 2 and 6, which corresponded to weeks 14, 16 and 20 since study enrolment (figure 1). No further maintenance vedolizumab was given thereafter. Flexible sigmoidoscopy performed after the second dose of vedolizumab showed moderate mucosal inflammation with no ulceration and was consistent with a Mayo endoscopic subscore of 2 (figure 2). Histology confirmed moderate active colitis with a mixed inflammatory infiltrate (figure 3). At week 20, after his third dose of vedolizumab, his faecal calprotectin was 310 µg/g. From then, oral prednisolone was weaned and ceased by week 26 at which time he had grade 1 diarrhoea. Two weeks later, the diarrhoea had completely resolved, and he subsequently ceased MMX by week 31, with no rebound symptoms.

Figure 2.

Mild active colitis on flexible sigmoidoscopy.

Figure 3.

H&E image at ×20 objective magnification showing mucus depletion, increased cellularity of the lamina propria due to a mixed inflammatory infiltrate and crypt abscess.

Outcome and follow-up

At latest follow-up on 7 April 2016 (week 33), the patient remained in remission with no longer palpable submental lymphadenopathy. His faecal calprotectin was 74 µg/g and a repeat whole-body FDG-PET/CT scan showed no evidence of disease, which included the previously observed solitary right submental lymph nodal deposit of melanoma.

Discussion

The immune checkpoint inhibitors, ipilimumab and nivolumab, have a well-established role in the treatment of advanced melanoma. Recently, the combination of ipilimumab and nivolumab gained US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and European Medicines Evaluation Agency approval for the treatment of unresectable or metastatic melanoma. In addition, the US FDA approved ipilimumab as adjuvant monotherapy for resected high-risk stage 3 melanoma. From the pivotal phase III EORTC 18071 trial, the dose of ipilimumab in the adjuvant setting is 10 mg/kg and is significantly higher than the approved dose of 3 mg/kg used in the metastatic setting.7 At the higher ipilimumab dose of 10 mg/kg, the incidence of grade 3 or more diarrhoea is at 16%. At these grades of toxicity, prompt institution of 1–2 mg/kg/day of oral or intravenous corticosteroid is recommended.7 For grade 2 diarrhoea unresponsive to loperamide, 0.5 mg/kg/day of oral corticosteroid is recommended.

Here, we present a case of an isolated gastrointestinal irAE—immune-mediated colitis with steroid dependency, and multiple recurrences of grade 2 diarrhoea at prednisolone doses <35 mg/day. Vedolizumab was used to enable steroid withdrawal while preventing recurrent colitis. We used vedolizumab instead of infliximab because the patient remained systemically well with no evidence of severe colitis (endoscopically or as assessed by faecal calprotectin) and had a new metastatic deposit of melanoma.

Infliximab is a chimeric IgG1 monoclonal antibody that neutralises TNF-α. TNF-α is a cytokine product of the effector T cells, which is strongly implicated in colonic inflammation; thus, infliximab can be an effective agent to treat colitis. It appears especially effective when there is a large inflammatory burden.8 Based only on case-series reports, infliximab is often recommended to treat severe forms of colitis related to ipilimumab therapy if conventional corticosteroid therapy fails.9 The justification supporting use of infliximab in ipilimumab-induced colitis derived from the clinical experience of its efficacy in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) as reported in the ACCENT 1 and ACT 1 studies.10 In IBD, infliximab's highest efficacy is in the presence of severe disease or in the setting of rescue therapy for acute severe ulcerative colitis (where high-dose intravenous corticosteroid therapy has failed). In this setting, its response rate is >80%.11 For less severe colitis, however, the response rates are far less impressive.10 12

Vedolizumab is a humanised IgG1 monoclonal antibody, which binds to α4β7 integrin heterodimer, expressed on the surface of memory T cells primed to traffic to the gut. Upon activation, α4β7 integrin-expressing T cells preferentially adhere to endothelial surfaces within the gut via the adhesion molecule, MadCAM-1. Consequently, vedolizumab-mediated inhibition of the α4β7 integrin/MAdCAM-1 interaction blocks leucocyte adherence to the gut endothelium and prevents out migration of leucocytes and, thus, limits colitis.13 Vedolizumab is effective in IBD, and the thought that it may have efficacy in ipilimumab-induced colitis is extrapolated from this population.14

Vedolizumab was chosen to be the more attractive option in the case reported above over conventional infliximab because of its gut selectively. This allowed minimisation of the potential risk for melanoma progression in a patient already known to have metastasis involving the submental lymph node. Vedolizumab use in this setting was thought less likely to mitigate the antitumour effect of ipilimumab and to have the additional benefit of not heightening the risk of opportunistic infection or secondary malignancies in an already vulnerable patient as is possible with infliximab use. Moreover, our patient was systemically well and did not have severe colitis to necessitate the need for infliximab, which gives better clinical response rates in more severe forms of colitis.

Induction course of vedolizumab therapy for the treatment of ipilimumab-induced colitis is currently an off-label indication. At present, vedolizumab is only approved for the treatment of patients with active IBD of moderate to severe severity. Vedolizumab elicits minimal systemic effects and is relatively safe due to its gut selective mechanism of action. Common reported adverse events with vedolizumab include headache, nausea, abdominal pain, fatigue and nasopharyngitis, although these did not occur in the registration studies any more frequently than with placebo (except nasopharyngitis). There have been no reports of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy with vedolizumab unlike natalizumab, which was a less selective anti-integrin agent.13 14

In conclusion, this is the first case reported where vedolizumab successfully treated steroid-dependent immune-mediated colitis due to ipilimumab, resulting in a sustained complete steroid-free remission. Vedolizumab's gut selective mode of action is a theoretical advantage, especially in the presence of ongoing metastatic disease. This warrants evaluation as a treatment for checkpoint inhibitor-induced colitis in a larger cohort.

Learning points.

Immune-related adverse events (irAEs) occur with checkpoint inhibitors and colitis can be problematic.

Gastrointestinal irAEs of grade 2 and higher do not always respond to corticosteroid administration and steroid dependency can occur.

Vedolizumab, an anti-integrin leucocyte trafficking inhibitor, is a novel treatment for treating ipilimumab-induced colitis.

Footnotes

Contributors: AH-CH involved in planning, conduct, reporting, proof reading and finalisation of the case report. MF involved in conduct and reporting of the case report. MPB and JMA contributed to planning, proof reading and finalisation of the case report.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Robert C, Long G, Brady B et al. Nivolumab in previously untreated melanoma without BRAF mutation. N Engl J Med 2015;372:320–30. 10.1056/NEJMoa1412082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weber JS, De'Angelo SP, Minor D et al. Nivolumab versus chemotherapy in patients with advanced melanoma who progressed after anti-CTLA-4 treatment (CheckMate 037): a randomised, controlled, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2015;14:375–84. 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)70076-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hodi FS, O'Day SJ, Mcdermott DF et al. Improved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med 2010;363:711–23. 10.1056/NEJMoa1003466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Robert C, Thomas L, Bondarenko I et al. Ipilimumab plus dacarbazine for previously untreated metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med 2011;364:2517–25. 10.1056/NEJMoa1104621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Villadolid J, Amin A. Immune checkpoint inhibitors in clinical practice: update on management of immune-related toxicities. Transl Lung Cancer Res 2015;4:560–75. 10.3978/j.issn.2218-6751.2015.06.06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pagès C, Gornet JM, Monsel G et al. Ipilimumab-induced acute severe colitis treated by infliximab. Melanoma Res 2013;23:227–30. 10.1097/CMR.0b013e32835fb524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eggermont AM, Chiarion-Sileni V, Grob JJ et al. Adjuvant ipilimumab versus placebo after complete resection of high-risk stage III melanoma (EORTC 18071): a randomised, double-blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2015;16:522–30. 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)70122-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dean KE, Hikaka J, Huakau JT et al. Infliximab or cyclosporine for acute severe ulcerative colitis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2012;27:487–92. 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2011.06958.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weber JS, Kahler KC, Hauschild A. Management of immune-related adverse events and kinetic of response with ipilimumab. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:2691–7. 10.1200/JCO.2012.41.6750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yapali S, Hamzaoglu HO. Anti-TNF treatment in inflammatory bowel disease. Ann Gastroenterol 2007;21:48–53. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Laharie D, Bourreile A, Branche J et al. Ciclosporin versus infliximab in patients with severe ulcerative colitis refractory to intravenous steroids: a parallel, open-label randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2012;380:1909–15. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61084-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guo Y, Lu N, Bai A et al. Clinical use and mechanisms of infliximab treatment on inflammatory bowel disease: a recent update. Biomed Res Int 2013;2013:581631 10.1155/2013/581631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mclean LP, Shea-Donohue T, Cross RK. Vedolizumab for the treatment of ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease. Immunotherapy 2012;4:883–98. 10.2217/imt.12.85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lau MSY, Tsai HH. Review of vedolizumab for treatment of ulcerative colitis. World J Gastrointest Pharmacol Ther 2016;7:107–11. 10.4292/wjgpt.v7.i1.107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]