Abstract

Background

Favorable levels of all readily measurable major cardiovascular disease risk factors (ie, low risk [LR]) are associated with lower risks of cardiovascular disease morbidity and mortality. Data are not available on LR prevalence among Hispanic/Latino adults of diverse ethnic backgrounds. This study aimed to describe the prevalence of a low cardiovascular disease risk profile among Hispanic/Latino adults in the United States and to examine cross‐sectional associations of LR with measures of acculturation.

Methods and Results

The multicenter, prospective, population‐based Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos examined 16 415 men and women aged 18 to 74 years at baseline (2008–2011) with diverse Hispanic/Latino backgrounds. Analyses involved 14 757 adults (mean age 41.3 years; 60.6% women). LR was defined using national guidelines for favorable levels of serum cholesterol, blood pressure, and body mass index and by not having diabetes mellitus and not currently smoking. Age‐adjusted LR prevalence was low (8.4% overall; 5.1% for men, 11.2% for women) and varied by background (4.2% in men of Mexican heritage versus 15.0% in women of Cuban heritage). Lower acculturation (assessed using proxy measures) was significantly associated with higher odds of a LR profile among women only: Age‐adjusted odds ratios of having LR were 1.64 (95% CI 1.24–2.17) for foreign‐born versus US‐born women and 1.96 (95% CI 1.49–2.58) for women residing in the United States <10 versus ≥10 years.

Conclusions

Among diverse US Hispanic/Latino adults, the prevalence of a LR profile is low. Lower acculturation is associated with higher odds of a LR profile among women but not men. Comprehensive public health strategies are needed to improve the cardiovascular health of US Hispanic/Latino adults.

Keywords: cardiovascular disease prevention, cardiovascular disease risk factors, low risk

Subject Categories: Primary Prevention, Cardiovascular Disease, Race and Ethnicity, Risk Factors

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is a leading cause of mortality among Hispanic/Latino adults in the United States. Although recent reports from the landmark Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos (HCHS/SOL) documented the substantial and pervasive burden of readily measurable major adverse CVD risk factors, marked variations in adverse CVD risk profiles among diverse Hispanic/Latino persons have also been noted, potentially related to their heterogeneous lifestyles, exposures, and acculturation to US society.1

Large‐scale prospective cohort studies of non‐Hispanic/Latino young adult and middle‐aged men and women with decades of follow‐up have demonstrated multiple beneficial outcomes associated with favorable levels of all major CVD risk factors (ie, low risk [LR]).2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 LR status in young adulthood or middle age is associated with markedly lower age‐specific CVD and total mortality rates, higher life expectancies, lower health care costs, and better quality of life at older ages.2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 The importance of population‐wide LR status to overcome the CVD epidemic is now widely accepted, with LR status forming the basis of the ideal cardiovascular health construct described in the American Heart Association (AHA) 2020 Impact Goal.8 According to national data, the prevalence of LR was ≈8.2% among non‐Hispanic white US adults (and 7.5% overall) in 1999–2004.9

Previous studies included few Hispanic/Latino participants,2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 and existing estimates of prevalence of LR status among US Hispanics/Latino adults based on national survey data are limited mostly to those of Mexican American heritage.9 Furthermore, there are no data on associations of low CVD risk status with acculturation among Hispanic/Latino adults from diverse backgrounds. Comprehensive and current data on the cardiovascular health of diverse US Hispanic/Latino groups, including not only the well‐known burden of adverse risk but also the less‐documented prevalence of favorable risk status, is critically important for the development of tailored individual‐ and population‐level interventions to prevent future CVD in this rapidly growing segment of the US population.

This paper describes the age‐, sex‐, and Hispanic/Latino background–specific prevalence of LR profile among diverse US Hispanic/Latino adults free of clinical CVD and examines the associations of LR profile with measures of acculturation using data from HCHS/SOL.

Methods

Study Design and Population

HCHS/SOL is a population‐based cohort study designed to examine risk and protective factors for chronic diseases among US Hispanic/Latino adults and to quantify morbidity and mortality prospectively. Details of the sampling methods and design have been published.10, 11 Briefly, between March 2008 and June 2011, 16 415 self‐identified Hispanic/Latino adults aged 18 to 74 years were recruited from randomly selected households in 4 US communities (Bronx, NY; Chicago, IL; Miami, FL; San Diego, CA), using a stratified 2‐stage probability sample design.10 Participants included adults with Cuban, Dominican, Mexican, Puerto Rican, and Central and South American backgrounds. The study was approved by the institutional review board at each center, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Examination Methods

Participants were asked to fast and to refrain from smoking for 12 hours prior to the examination and to avoid vigorous physical activity the morning of the visit. Information was obtained using questionnaires on demographic factors, socioeconomic status, cigarette smoking, physical activity (moderate/heavy intensity work and leisure activities in a typical week), and medical history and the Short Acculturation Scale for Hispanics (SASH),12 which includes social and language subscales and proxy measures of acculturation (including nativity, duration of residence in the United States, generational status, language preference, and age at immigration). Participants were instructed to bring all medications they had taken in the past month.

Height was measured to the nearest centimeter and body weight to the nearest 0.1 kg. Body mass index (BMI) was computed as weight divided by height squared (kg/m2). Following a 5‐minute rest period, 3 seated blood pressure (BP) measurements were obtained using an automatic sphygmomanometer; the second and third readings were averaged. Blood samples were collected and shipped to a central laboratory for analysis according to standardized protocols. Blind replicate measurements were conducted for 5% of the samples. Details of the quality control procedures implemented have been described previously.11 Total serum cholesterol was measured using a cholesterol oxidase enzymatic method, and high‐density lipoprotein cholesterol was measured using a direct magnesium/dextran sulfate method. Plasma glucose was measured using a hexokinase enzymatic method (Roche Diagnostics Corp). Low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol was calculated using the Friedewald equation.13 Hemoglobin A1c was measured using the Tosoh G7 Automated HPLC Analyzer (Tosoh Bioscience Inc).

Definition of Risk Factors

Favorable levels of major CVD risk factors were defined based on national guidelines.14, 15, 16, 17 LR status was defined as having all of the following factors: serum total cholesterol <200 mg/dL and not taking cholesterol‐lowering medication; systolic BP <120 mm Hg, diastolic BP <80 mm Hg, and not taking antihypertensive medication; BMI <25; not currently smoking; and fasting glucose <100 mg/dL, hemoglobin A1c <5.7%, not taking medication for diabetes mellitus, and no history of diabetes mellitus.

Unfavorable or borderline risk factor levels were defined as total cholesterol 200 to 239 mg/dL and not taking cholesterol‐lowering medications; systolic BP 121 to 139 mm Hg or diastolic BP 81 to 89 mm Hg and not taking antihypertension medication; fasting glucose 100 to 125.9 mg/dL or hemoglobin A1c 5.7% to 6.4%, not taking medication for diabetes mellitus, and no history of diabetes mellitus; and BMI 25.0 to 29.9. Adverse CVD risk factors were defined as serum cholesterol ≥240 mg/dL or taking cholesterol‐lowering medication; systolic BP ≥140 mm Hg or diastolic BP ≥90 mm Hg or taking antihypertensive medication; BMI ≥30.0; fasting glucose ≥126 mg/dL, hemoglobin A1c ≥6.5%, or taking medication for diabetes mellitus; and current cigarette smoking. Participants not at LR were classified as having no adverse but ≥1 unfavorable or borderline risk factor, any single adverse risk factor, or ≥2 adverse risk factors. Of note, smoking status was dichotomized as not currently smoking (LR) versus current smoking (adverse), consistent with both previous research on low CVD risk profile3, 6 and the AHA's definition of cardiovascular health metrics8 included in the ideal cardiovascular health construct (designed to be simple and accessible by the public and by health practitioners and to represent actionable items to improve cardiovascular health). Participants classified as having no adverse but ≥1 unfavorable or borderline risk factor were, by definition, not current smokers.

Statistical Analyses

Reported values for mean, prevalence, and odds ratio were weighted to adjust for sampling probability and nonresponse.10, 11 All analyses were conducted for men and women separately. Age‐adjusted LR prevalence was calculated by Hispanic/Latino background for all participants and stratified by age groups (18–44 years that is young adults, and 45–74 years that is middle‐aged and older adults). Prevalence of LR age‐standardized to the 2010 US population was also calculated. Logistic regression analyses, adjusted for age and education, were used to examine associations of LR profile (compared with not LR) with SASH scores and proxy measures of acculturation. Analyses adjusted for family history of coronary heart disease, income, health insurance status, Hispanic/Latino background, and field center were also conducted. Additional sensitivity analyses were conducted to examine age‐adjusted association of LR status with measures of acculturation across strata of educational attainment. Odds ratios with 95% CIs were computed.

Age‐adjusted descriptive characteristics were computed for LR participants and compared with those with unfavorable or adverse CVD risk status. Differences between groups were tested using chi‐square tests for categorical variables and F tests for continuous variables. All analyses were performed using survey‐specific procedures to account for the multistage sampling design, stratification, and clustering in SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute) and SUDAAN release 10.0.0 (Research Triangle Institute).

Exclusions

Of the 16 415 HCHS/SOL participants, 1658 were excluded from these analyses for the following reasons: missing data on total cholesterol (n=134), BMI (n=53), cigarette smoking (n=35), or other covariates (n=481); electrocardiographic evidence of past myocardial infarction (n=360); baseline age ≥75 years (n=5); or lack of self‐identification as any of the 6 aforementioned Hispanic/Latino backgrounds (n=590). Consequently, these analyses included data from 14 757 participants (5810 men and 8947 women).

Results

Characteristics of the Study Cohort

The mean age of the participants was 41.3 years, and 60.6% were women. Overall, 32.7% of the sample had less than a high school education, 49.8% were married or living with a partner, and 71.2% had lived in the United States for ≥10 years. Spanish was the preferred language for the majority of participants (76.5%), and 49.7% had some health insurance (data not shown).

Prevalence of LR Status and Individual Favorable Risk Factors

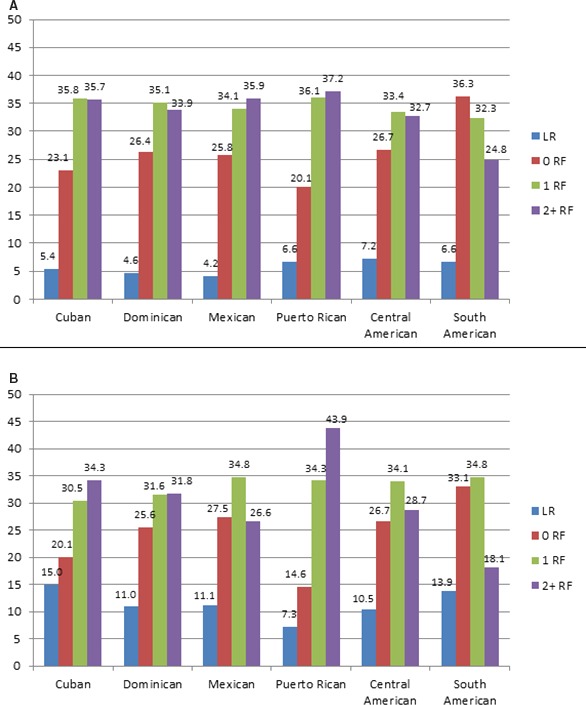

The prevalence of LR status by Hispanic/Latino background is depicted for all participants in Table 1 and for men and women in Figure — Panel A and B, respectively. Among HCHS/SOL participants, the overall age‐adjusted prevalence of LR status was 8.4%. Among both sexes and all Hispanic/Latino backgrounds, LR status was uniformly rare. Among men, overall age‐adjusted LR prevalence was 5.1%, whereas LR prevalence age‐standardized to the 2010 US population was 4.9% (Table 1); age‐adjusted LR prevalence ranged from 4.2% (Mexican men) to 7.2% (Central American men) (Table 1 and Figure — Panel A). Adjustment for educational attainment, duration of residence in the United States, health insurance status (Table 1), or language preference (data not shown) did not appreciably alter the findings. Among men aged 18 to 44 years, LR prevalence averaged 8.1% overall and ranged from 7.2% (Mexican) to 10.7% (South American); among men aged 45 to 74 years, LR prevalence averaged 1.4% (range 0.6–1.6%) (Table 2) (Table S1 provides the numbers of participants used to calculate weighted prevalence in Table 2).

Table 1.

Adjusted Prevalence of Low CVD Risk Status by Sex and Hispanic/Latino Background

| Prevalence of Low CVD Risk Statusa, b | Hispanic/Latino Background | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | Cuban | Dominican | Mexican | Puerto Rican | Central American | South American | P Value | |

| All participants | ||||||||

| Participants, n | 14 757 | 2238 | 1369 | 6035 | 2481 | 1624 | 1010 | — |

| Age‐standardizedc | 7.6 (6.8–8.3) | 9.5 (7.7–11.3) | 7.6 (6.0–9.2) | 7.4 (6.2–8.6) | 5.7 (4.3–7.1) | 7.9 (6.1–9.7) | 9.7 (7.0–12.3) | 0.0176 |

| Age‐adjusted | 8.4 (7.6–9.1) | 10.4 (8.9–11.8) | 8.0 (5.9–10.1) | 7.7 (6.2–9.1) | 6.8 (5.4–8.3) | 8.6 (6.5–10.7) | 10.2 (7.6–12.7) | 0.0111 |

| Men | ||||||||

| Participants, n | 5810 | 1040 | 473 | 2236 | 1019 | 629 | 413 | — |

| Age standardizedc | 4.9 (4.1–5.7) | 4.9 (3.1–6.8) | 4.3 (2.3–6.3) | 4.3 (3.0–5.6) | 6.0 (4.0–8.1) | 6.7 (3.7–9.7) | 6.1 (3.4–8.8) | 0.4741 |

| Adjusted for age | 5.1 (4.2–6.0) | 5.4 (3.8–7.0) | 4.6 (2.1–7.0) | 4.2 (2.7–5.8) | 6.6 (4.3–8.8) | 7.2 (3.6–10.7) | 6.6 (3.5–9.7) | 0.3853 |

| Adjusted for age, education | 5.1 (4.2–6.0) | 5.3 (3.7–6.9) | 4.6 (2.2–7.1) | 4.3 (2.7–5.8) | 6.6 (4.3–8.8) | 7.3 (3.7–10.9) | 6.5 (3.4–9.6) | 0.3911 |

| Adjusted for age, education, years in US | 5.1 (4.2–6.0) | 5.4 (3.6–7.1) | 4.5 (2.0–6.9) | 4.3 (2.7–5.8) | 6.5 (3.9–9.0) | 7.4 (3.8–11.0) | 6.2 (3.1–9.3) | 0.4355 |

| Adjusted for age, education, years in US, health insurance | 5.3 (4.4–6.2) | 5.8 (4.0–7.6) | 4.4 (1.7–7.0) | 4.5 (3.0–6.0) | 6.2 (3.6–8.9) | 7.8 (4.1–11.4) | 6.5 (3.3–9.7) | 0.4310 |

| Adjusted for age, education, years in US, health insurance, physical activity | 5.5 (4.6–6.4) | 5.8 (4.0–7.6) | 4.5 (1.9–7.2) | 4.7 (3.1–6.3) | 6.6 (3.8–9.3) | 7.6 (4.0–11.3) | 5.7 (2.8–8.7) | 0.5423 |

| Women | ||||||||

| Participants, n | 8947 | 1198 | 896 | 3799 | 1462 | 995 | 597 | — |

| Age standardizedc | 10.2 (9.1–11.2) | 14.4 (11.9–16.9) | 10.1 (7.6–12.6) | 10.3 (8.5–12.0) | 5.4 (3.7–7.1) | 9.5 (7.2–11.5) | 13.4 (9.5–17.4) | <0.001 |

| Adjusted for age | 11.2 (10.1–12.3) | 15.0 (12.7–17.3) | 11.0 (7.9–14.1) | 11.0 (9.0–13.1) | 7.3 (5.6–9.1) | 10.5 (8.0–12.9) | 14.0 (10.2–17.8) | <0.0001 |

| Adjusted for age, education | 11.3 (10.2–12.3) | 14.6 (12.3–17.0) | 11.0 (7.9–14.1) | 11.3 (9.2–13.4) | 7.3 (5.5–9.0) | 10.9 (8.4–13.4) | 13.6 (9.8–17.4) | <0.0001 |

| Adjusted for age, education, years in US | 11.2 (10.1–12.3) | 13.9 (11.5–16.4) | 10.7 (7.6–13.8) | 11.4 (9.3–13.5) | 8.4 (6.3–10.4) | 10.5 (7.9–13.0) | 13.0 (9.1–16.9) | 0.0225 |

| Adjusted for age, education, years in US, health insurance | 11.3 (10.2–12.4) | 14.0 (11.5–16.4) | 10.5 (7.3–13.7) | 11.5 (9.4–13.6) | 8.4 (6.2–10.6) | 10.7 (8.1–13.3) | 13.4 (9.4–17.3) | 0.0346 |

| Adjusted for age, education, years in US, health insurance, physical activity | 11.2 (10.1–12.3) | 13.9 (11.3–16.5) | 10.7 (7.5–13.9) | 11.5 (9.4–13.6) | 8.4 (6.2–10.6) | 10.7 (8.0–13.3) | 13.3 (9.3–17.3) | 0.0371 |

CVD indicates cardiovascular disease; US, United States.

All values (except n) were weighted for survey design and nonresponse.

Low‐risk status described under “Definition of Risk Factors.”

Age standardized to the 2010 US population.

Figure 1.

Age‐adjusted prevalence of cardiovascular disease risk profiles by Hispanic/Latino background in men (A) and in women (B). Risk profile details are described under “Definition of Risk Factors.” All values were weighted for survey design and nonresponse and adjusted for age. BMI indicates body mass index; BP, blood pressure; LR, low risk; RF, risk factor.

Table 2.

Age‐Stratified Prevalence of Low CVD Risk Status by Sex and Hispanic/Latino Background

| Age Group, y | Prevalence of Low‐Risk Statusa, b | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All, n (%) | Cuban, n (%) | Dominican, n (%) | Mexican, n (%) | Puerto Rican, n (%) | Central American, n (%) | South American, n (%) | |

| Men | |||||||

| 18–44 | 202 (8.1) | 26 (7.3) | 16 (8.0) | 73 (7.2) | 37 (10.2) | 30 (9.4) | 20 (10.7) |

| 45–74 | 34 (1.4) | 7 (0.6) | 2 (1.0) | 10 (1.5) | 7 (1.6) | 5 (1.3) | 3 (0.9) |

| Women | |||||||

| 18–44 | 550 (17.9) | 74 (23.3) | 67 (18.5) | 258 (17.9) | 44 (10.0) | 65 (17.2) | 42 (21.8) |

| 45–74 | 73 (1.2) | 7 (1.0) | 8 (1.5) | 38 (1.8) | 5 (0.3) | 7 (0.9) | 8 (1.5) |

CVD indicates cardiovascular disease.

All values (except n) were weighted for survey design and nonresponse.

Low‐risk status is described under “Definition of Risk Factors.”

Among women, age‐adjusted LR prevalence was also uniformly low overall (11.2%), whereas age‐standardized prevalence was 10.2% (Table 1). Age‐adjusted LR prevalence ranged from 7.3% (Puerto Rican women) to 15.0% (Cuban women). Adjustment for educational attainment did not alter the findings. LR prevalence among women aged 18 to 44 years ranged from 10.0% (Puerto Rican women) to 23.3% (Cuban women), whereas among those aged 45 to 74 years, LR prevalence ranged from 0.3% to 1.8% (Table 2).

Lack of current smoking was the most predominant favorable risk factor among both men (74.1%) and women (83.9%). Slightly more than half of men (51.3%) also had favorable serum cholesterol levels, and a sizeable proportion of women had ideal glucose levels (59.8%), ideal BP (58.9%), and ideal serum cholesterol levels (54.7%), with no medication use for any of these risk factors; however, less than a fourth of men and women had a favorable BMI. Men with Mexican backgrounds had the lowest rates of favorable levels of serum glucose, and BMI and those of Puerto Rican background the lowest rates of not currently smoking. Among women, those with Puerto Rican backgrounds had the lowest rates of favorable BP levels, BMI, and not currently smoking (Table 3).

Table 3.

Adjusted Prevalence of Low CVD Risk Status and Components of LR by Sex and Hispanic/Latino Background

| LR Statusa and Individual Favorable Risk Factors | Hispanic/Latino Background | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | Cuban | Dominican | Mexican | Puerto Rican | Central American | South American | P Value | |

| All | ||||||||

| Participants, n | 14 757 | 2238 | 1369 | 6035 | 2481 | 1624 | 1010 | |

| LR status | 8.4 (7.6–9.1) | 10.4 (8.9–11.8) | 8.0 (5.9–10.1) | 7.7 (6.2–9.1) | 6.8 (5.4–8.3) | 8.6 (6.5–10.7) | 10.2 (7.6–12.7) | 0.0111 |

| Serum total cholesterol <200 mg/dL and not taking cholesterol‐lowering medication | 41.6 (40.3–42.9) | 52.1 (50.2–54.1) | 56.1 (52.7–59.5) | 52.1 (50.2–54.0) | 57.9 (55.2–60.6) | 49.2 (46.3–52.1) | 50.1 (46.3–54.0) | 0.0001 |

| Systolic BP <120 mm Hg, diastolic BP <80 mm Hg, and not taking antihypertensive medication | 39.1 (37.7–40.5) | 45.8 (43.8–47.8) | 41.6 (38.1–45.1) | 54.5 (52.6–56.4) | 45.8 (43.2–48.5) | 49.0 (46.3–51.8) | 57.3 (53.5–61.1) | <0.0001 |

| BMI <25 | 18.5 (17.6–19.4) | 28.1 (25.9–30.3) | 20.6 (17.8–23.4) | 20.7 (19.0–22.4) | 21.8 (19.2–24.4) | 23.3 (20.3–26.4) | 29.4 (25.2–33.7) | <0.0001 |

| Not currently smoking | 71.8 (70.6–73.0) | 73.3 (70.6–75.9) | 88.3 (85.2–91.4) | 83.0 (81.3–84.8) | 67.0 (64.1–69.9) | 85.8 (83.6–88.1) | 86.1 (82.9–89.2) | <0.0001 |

| Fasting glucose <100 mg/dL, hemoglobin A1c <5.7%, not taking medication for diabetes mellitus, and no history of diabetes mellitus | 43.1 (41.7–44.5) | 60.1 (58.0–62.1) | 55.1 (51.8–58.5) | 51.7 (49.6–53.8) | 52.8 (50.2–55.4) | 55.2 (52.2–58.3) | 61.7 (58.4–65.1) | <0.0001 |

| Men | ||||||||

| Participants, n | 5810 | 1040 | 473 | 2236 | 1019 | 629 | 413 | |

| LR status | 5.1 (4.2–6.0) | 5.4 (3.8–7.0) | 4.6 (2.1–7.0) | 4.2 (2.7–5.8) | 6.6 (4.3–8.8) | 7.2 (3.6–10.7) | 6.6 (3.5–9.7) | 0.3853 |

| Serum total cholesterol <200 mg/dL and not taking cholesterol‐lowering medication | 51.3 (49.6–52.9) | 51.5 (48.0–55.1) | 53.3 (48.1–58.6) | 49.1 (46.3–52.0) | 59.1 (55.3–63.0) | 47.1 (41.9–52.3) | 46.3 (40.5–52.1) | 0.0004 |

| Systolic BP <120 mm Hg, diastolic BP <80 mm Hg, and not taking antihypertensive medication | 39.0 (37.3–40.7) | 36.3 (33.2–39.5) | 25.2 (20.1–30.3) | 42.4 (39.3–45.5) | 40.6 (36.6–44.6) | 41.1 (36.1–46.0) | 49.8 (43.3–56.2) | <0.0001 |

| BMI <25 | 22.1 (20.6–23.6) | 28.1 (24.6–31.5) | 17.9 (14.0–21.9) | 17.3 (14.9–19.6) | 25.2 (21.6–28.8) | 24.4 (19.6–29.1) | 24.3 (19.4–29.1) | <0.0001 |

| Not currently smoking | 74.1 (72.3–75.8) | 68.6 (65.2–72.0) | 89.2 (85.0–93.3) | 75.3 (72.2–78.4) | 66.0 (61.8–70.1) | 78.7 (74.5–82.8) | 85.4 (80.4–90.4) | <0.0001 |

| Fasting glucose <100 mg/dL, hemoglobin A1c <5.7%, not taking medication for diabetes mellitus, and no history of diabetes mellitus | 49.2 (47.5–50.9) | 52.2 (49.2–55.2) | 48.7 (44.2–53.2) | 46.7 (43.6–49.8) | 48.4 (44.7–52.1) | 50.9 (45.8–56.0) | 56.8 (51.4–62.2) | 0.0186 |

| Women | ||||||||

| Participants, n | 8947 | 1198 | 896 | 3799 | 1462 | 995 | 597 | |

| LR status | 11.2 (10.1–12.3) | 15.0 (12.7–17.3) | 11.0 (7.9–14.1) | 11.0 (9.0–13.1) | 7.3 (5.6–9.1) | 10.5 (8.0–12.9) | 14.0 (10.2–17.8) | <0.0001 |

| Serum total cholesterol <200 mg/dL and not taking cholesterol‐lowering medication | 54.7 (53.4–56.1) | 52.3 (49.8–54.8) | 58.3 (54.3–62.4) | 55.0 (52.6–57.4) | 57.1 (53.7–60.5) | 51.7 (47.7–55.6) | 54.3 (49.6–59.0) | 0.0489 |

| Systolic BP <120 mm Hg, diastolic BP <80 mm Hg, and not taking antihypertensive medication | 58.9 (57.4–60.3) | 53.8 (51.4–56.1) | 54.7 (50.5–58.8) | 65.8 (63.2–68.4) | 51.2 (48.1–54.2) | 57.2 (54.4–60.1) | 65.6 (61.3–69.8) | <0.0001 |

| BMI <25 | 24.0 (22.5–25.5) | 27.9 (24.8–30.9) | 22.6 (18.5–26.7) | 23.9 (21.3–26.5) | 18.5 (15.6–21.4) | 22.7 (19.1–26.2) | 34.1 (27.9–40.3) | <0.0001 |

| Not currently smoking | 83.9 (82.6–85.1) | 77.3 (74.3–80.3) | 88.8 (84.6–93.1) | 89.8 (87.9–91.7) | 67.6 (64.1–71.1) | 92.2 (90.4–94.1) | 86.9 (83.5–90.3) | <0.0001 |

| Fasting glucose <100 mg/dL, hemoglobin A1c <5.7%, not taking medication for diabetes mellitus, and no history of diabetes mellitus | 59.8 (58.4–61.1) | 67.3 (65.1–69.6) | 60.6 (56.5–64.7) | 56.4 (54.0–58.7) | 57.0 (53.6–60.4) | 59.4 (56.3–62.5) | 66.7 (62.6–70.7) | <0.0001 |

BMI indicates body mass index; BP, blood pressure; CVD, cardiovascular disease; LR, low risk.

LR status is described under “Definition of Risk Factors.”

Rates of individual favorable risk factors differed between men and women, although these sex differences varied across age strata. Prevalence of favorable serum cholesterol levels was 10.8 percentage points higher for women aged 18 to 44 years compared with men of the same age range. Conversely, among those aged 45 to 74 years, prevalence of favorable serum cholesterol levels was 9.14 percentage points lower in women compared with men. Findings were similar for favorable BMI levels, although the magnitudes of the sex differences in LR prevalence in each age strata were lower (4.79 percentage points higher for women versus men aged 18–44 years and 3.31 percentage points lower for women versus men aged 45–74 years). Rates of no current smoking, ideal glucose levels, and particularly ideal BP levels were markedly higher in women aged 18 to 44 years (about 11–28 percentage points higher) compared with men in the same age range. Although rates of these favorable risk factors were also higher among women (versus men) aged 45 to 74 years (by about 3–8 percentage points), the magnitude of differences was much lower (data not shown).

Association of LR Status With Measures of Acculturation

Among women, being less acculturated was positively associated with having a LR profile versus not (ie, all others) (Table 4). In age‐adjusted analyses, for example, women who were foreign born (versus US born), who had resided in the United States <10 years (versus ≥10 years; among all participants), and who preferred the use of Spanish to English had 1.64, 1.96, and 1.54 times higher odds, respectively, of being LR. Women with SASH language subscale scores <3 versus ≥3 (ie, lower versus higher acculturation) had 1.58 times higher odds of being LR compared with not LR. In contrast, the odds of being LR did not differ by levels of SASH social subscale scores. Among men, no significant associations were found between SASH scores or proxy measures of acculturation and LR prevalence (Table 4). Analyses adjusted for family history of coronary heart disease and for Hispanic/Latino background, health insurance status, and field center yielded similar results (data not shown). Additional sensitivity analyses examining the age‐adjusted association of LR status with measures of acculturation across educational attainment strata revealed no significant associations among men. Although associations between measures of acculturation and LR status differed across strata of educational attainment for women, effect estimates were unstable, given the small numbers in the cells (data not shown).

Table 4.

Adjusted Associations of LR Status With Measures of Acculturation by Sex

| Measure of Acculturationb | LR (Reference: Not LR)a | |

|---|---|---|

| Age‐Adjustedc OR (95% CI) | Age‐ and Education‐Adjustedc OR (95% CI) | |

| Men | ||

| Foreign born | 1.03 (0.73–1.46) | 1.09 (0.77–1.54) |

| Residence in US <10 years | 0.87 (0.61–1.23) | 0.88 (0.62–1.25) |

| Prefer Spanish | 0.84 (0.57–1.23) | 0.88 (0.61–1.29) |

| Age at immigration, y | 0.99 (0.96–1.01) | 0.99 (0.96–1.01) |

| Age ≥25 years at immigration | 1.19 (0.65–2.19) | 1.14 (0.62–2.09) |

| SASH language subscale (low; ie, <3) | 0.83 (0.57–1.21) | 0.87 (0.60–1.27) |

| SASH social subscale (low; ie, <3) | 0.77 (0.52–1.15) | 0.79 (0.53–1.19) |

| Women | ||

| Foreign born | 1.64 (1.24–2.17) | 1.69 (1.28–2.24) |

| Residence in US <10 years | 1.96 (1.49–2.58) | 2.01 (1.54–2.63) |

| Prefer Spanish | 1.54 (1.14–2.08) | 1.71 (1.27–2.30) |

| Age at immigration, y | 1.05 (1.02–1.07) | 1.05 (1.02–1.07) |

| Age ≥25 years at immigration | 2.04 (1.39–2.99) | 1.88 (1.27–2.78) |

| SASH language subscale (low; ie, <3) | 1.58 (1.19–2.11) | 1.71 (1.29–2.28) |

| SASH social subscale (low; ie, <3) | 1.27 (0.92–1.76) | 1.34 (0.98–1.83) |

LR indicates low risk; OR, odds ratio; SASH, Short Acculturation Scale for Hispanics; US, United States.

LR status is described under “Definition of Risk Factors.”

Models constructed comparing foreign‐born vs US‐born participants, residence in US <10 years vs ≥10 years, Spanish language preference vs English, and SASH scores <3 vs ≥3. Variables were entered into the model individually.

All values (except n) were weighted for survey design and nonresponse.

Characteristics of LR Participants Compared With Others

Tables 5 and 6 provide age‐adjusted demographic, socioeconomic, and sociocultural characteristics of Hispanic/Latino men and women across CVD risk groups. LR men and women were significantly younger than others. After adjustment for age, LR adults had the highest mean educational attainment, with differences across groups significant for women but not for men. In addition, the proportion of participants with an annual family income <$20 000 was lowest among LR men and women compared with others, with significant differences for women.

Table 5.

Descriptive Characteristics of HCHS/SOL Participants, All and by Risk Status—Men

| Characteristica | CVD Risk Status,b Mean or % (95% CI) | P Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | LR | 0 RF | 1 RF | 2+ RF | ||

| Participants, n | 5810 | 236 | 1347 | 1977 | 2250 | |

| Age | 40.4 (39.8–41.0) | 27.3 (25.8–28.7) | 35.6 (34.7–36.4) | 38.7 (37.8–39.7) | 47.9 (47.0–48.8) | <0.0001 |

| Education (%) | ||||||

| Less than high school | 32.6 (30.7–34.5) | 28.2 (21.9–34.5) | 30.6 (26.8–34.4) | 33.6 (30.7–36.5) | 33.5 (30.3–36.8) | 0.3674 |

| High school graduate | 30.5 (28.8–32.2) | 35.5 (27.9–43.2) | 30.2 (26.7–33.7) | 29.7 (26.7–32.7) | 30.5 (27.7–33.3) | 0.5770 |

| Beyond high school | 36.9 (34.8–39.0) | 36.3 (27.6–45.0) | 39.2 (35.4–42.9) | 36.7 (33.3–40.0) | 36.0 (32.8–39.1) | 0.5593 |

| Years of education | 11.8 (11.6–12.0) | 12.1 (11.6–12.7) | 12.0 (11.6–12.3) | 11.8 (11.6–12.0) | 11.6 (11.4–11.8) | 0.3059 |

| Annual family income (%) | ||||||

| <$20 000 | 38.4 (36.1–40.8) | 32.9 (24.8–40.9) | 35.7 (31.9–39.5) | 38.3 (35.1–41.5) | 41.5 (38.0–44.9) | 0.0568 |

| $20 000–50 000 | 39.5 (37.6–41.4) | 44.4 (35.7–53.1) | 38.9 (35.2–42.6) | 37.7 (34.6–40.8) | 41.2 (38.1–44.4) | 0.3123 |

| >$50 000 | 14.7 (12.6–16.9) | 10.9 (4.9–17.0) | 18.3 (13.7–22.9) | 16.1 (13.3–18.9) | 11.2 (9.0–13.5) | 0.0040 |

| Not reported | 7.3 (6.3–8.4) | 11.8 (6.9–16.7) | 7.1 (5.0–9.2) | 7.9 (6.3–9.5) | 6.1 (4.7–7.4) | 0.0738 |

| Marital status (%) | ||||||

| Single | 36.2 (34.4–37.9) | 46.1 (39.5–52.7) | 32.9 (29.4–36.4) | 36.2 (33.3–39.2) | 36.4 (33.7–39.0) | 0.0048 |

| Married/living with partner | 52.2 (50.1–54.2) | 42.8 (35.3–50.3) | 56.3 (52.5–60.0) | 52.0 (48.9–55.1) | 52.2 (49.1–55.2) | 0.0049 |

| Separated/divorced/widowed | 11.6 (10.6–12.7) | 11.1 (8.3–13.8) | 10.8 (9.1–12.6) | 11.8 (9.9–13.7) | 11.5 (9.6–13.4) | 0.8848 |

| US born (%) | 22.6 (20.7–24.6) | 24.3 (17.1–31.6) | 18.4 (14.6–22.3) | 23.1 (20.3–26.0) | 24.7 (22.0–27.5) | 0.0481 |

| Residence in US ≥10 years | 72.2 (69.9–74.4) | 75.0 (68.0–82.0) | 66.5 (62.9–70.2) | 71.3 (68.2–74.3) | 76.8 (73.5–80.0) | <0.0001 |

| Immigrant generation (%) | ||||||

| First | 75.7 (73.6–77.7) | 73.6 (66.2–80.9) | 80.6 (76.7–84.4) | 75.4 (72.5–78.2) | 73.0 (69.9–76.0) | 0.0140 |

| Second or higher | 24.3 (22.3–26.4) | 26.4 (19.1–33.8) | 19.4 (15.6–23.3) | 24.6 (21.8–27.5) | 27.0 (24.0–30.1) | 0.0140 |

| Age at immigration (%) | ||||||

| ≤10 years | 11.3 (10.0–12.5) | 21.4 (12.9–29.9) | 7.9 (5.5–10.2) | 10.6 (8.7–12.5) | 12.9 (10.6–15.2) | 0.0005 |

| 11–24 years | 41.6 (39.4–43.8) | 33.6 (23.9–43.3) | 41.5 (37.9–45.1) | 43.3 (40.0–46.7) | 41.4 (37.5–45.3) | 0.3107 |

| 25 years | 47.1 (44.7–49.5) | 44.9 (36.4–53.5) | 50.6 (46.9–54.3) | 46.1 (42.8–49.3) | 45.6 (41.7–49.6) | 0.1059 |

| Age at immigration, y | 25.4 (24.8–26.0) | 24.4 (22.7–26.1) | 26.9 (26.0–27.8) | 25.3 (24.5–26.0) | 24.7 (23.8–25.7) | 0.0001 |

| Language preference (%) | ||||||

| Spanish | 75.3 (73.2–77.5) | 69.8 (61.3–78.3) | 81.6 (78.3–84.8) | 75.6 (72.6–78.6) | 71.7 (68.6–74.8) | <0.0001 |

| English | 24.7 (22.5–26.8) | 30.2 (21.7–38.7) | 18.4 (15.2–21.7) | 24.4 (21.4–27.4) | 28.3 (25.2–31.4) | <0.0001 |

| SASH language subscale | ||||||

| Low (1 to <3) | 76.4 (74.5–78.3) | 71.0 (62.7–79.4) | 82.0 (78.6–85.3) | 76.6 (73.8–79.4) | 73.2 (70.1–76.2) | 0.0012 |

| High (≥3) | 23.6 (21.7–25.5) | 29.0 (20.6–37.3) | 18.0 (14.7–21.4) | 23.4 (20.6–26.2) | 26.8 (23.8–29.9) | 0.0012 |

| SASH language subscale score | 2.0 (2.0–2.1) | 2.2 (2.0–2.4) | 1.9 (1.8–2.0) | 2.0 (2.0–2.1) | 2.1 (2.0–2.2) | 0.0012 |

| SASH social subscale | ||||||

| Low (1 to <3) | 81.7 (80.1–83.2) | 76.7 (69.1–84.4) | 83.8 (81.1–86.6) | 81.4 (78.8–84.1) | 81.2 (78.7–83.8) | 0.2597 |

| High (≥3) | 18.3 (16.8–19.9) | 23.3 (15.6–30.9) | 16.2 (13.4–18.9) | 18.6 (15.9–21.2) | 18.8 (16.2–21.3) | 0.2597 |

| SASH social subscale score | 2.3 (2.2–2.3) | 2.3 (2.3–2.4) | 2.2 (2.2–2.3) | 2.3 (2.2–2.3) | 2.3 (2.2–2.3) | 0.1204 |

| Health insurance (%) | 47.3 (45.0–49.5) | 59.9 (51.8–68.0) | 47.1 (42.4–51.8) | 45.7 (42.5–49.0) | 47.2 (44.2–50.3) | 0.0102 |

| Total physical activity, MET‐min/day | 929.8 (879.6–979.9) | 836.5 (611.6–1061.5) | 972.1 (867.7–1076.6) | 907.1 (832.9–981.2) | 921.9 (844.8–999.0) | 0.5647 |

0 RF indicates, no adverse but ≥1 unfavorable risk factor; 1 RF, any single adverse risk factor; 2+ RF, ≥2 adverse risk factors; BMI, body mass index; BP, blood pressure; CVD, cardiovascular disease; LR, low risk; MET, metabolic equivalent; RF, risk factor; SASH, Short Acculturation Scale for Hispanics; US, United States.

All values (except n) were weighted for survey design and nonresponse. All variables (except age) were adjusted for age.

Risk status details are described under “Definition of Risk Factors.”

Table 6.

Descriptive Characteristics of HCHS/SOL Participants, All and by Risk Status—Women

| Characteristica | CVD Risk Status,b Mean or % (95% CI) | P Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | LR | 0 RF | 1 RF | 2+ RF | ||

| Participants, n | 8947 | 623 | 1851 | 3059 | 3414 | |

| Age | 42.1 (41.5–42.6) | 27.6 (26.7–28.5) | 37.0 (36.1–38.0) | 40.6 (39.8–41.3) | 52.1 (51.1–53.0) | <0.0001 |

| Education (%) | ||||||

| Less than high school | 32.8 (31.0–34.6) | 22.1 (17.9–26.3) | 31.3 (27.4–35.1) | 32.6 (30.1–35.1) | 37.9 (34.8–41.1) | <0.0001 |

| High school graduate | 27.1 (25.7–28.6) | 25.6 (20.5–30.8) | 24.2 (20.9–27.4) | 27.5 (25.1–29.9) | 29.4 (26.4–32.4) | 0.1763 |

| Beyond high school | 40.1 (38.1–42.1) | 52.3 (46.1–58.4) | 44.5 (40.6–48.5) | 39.9 (37.3–42.6) | 32.7 (29.8–35.5) | <0.0001 |

| Years of education | 11.7 (11.6–11.9) | 12.5 (12.1–12.9) | 12.0 (11.7–12.4) | 11.8 (11.6–12.0) | 11.1 (10.9–11.3) | <0.0001 |

| Annual family income (%) | ||||||

| <$20 000 | 45.8 (44.0–47.5) | 35.4 (30.0–40.8) | 43.2 (39.5–46.8) | 46.4 (43.7–49.1) | 51.1 (47.6–54.5) | <0.0001 |

| $20 000–50 000 | 34.3 (32.6–35.9) | 38.9 (33.9–43.9) | 35.1 (31.8–38.3) | 35.3 (32.7–37.8) | 31.0 (28.1–33.8) | 0.0373 |

| >$50 000 | 8.8 (7.5–10.0) | 10.0 (6.7–13.4) | 11.7 (8.6–14.8) | 9.6 (7.8–11.3) | 5.0 (3.4–6.6) | 0.0003 |

| Not reported | 11.2 (10.2–12.3) | 15.7 (11.8–19.6) | 10.1 (8.1–12.0) | 8.8 (7.4–10.2) | 12.9 (11.3–14.6) | <0.0001 |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Single | 31.9 (30.4–33.4) | 35.5 (30.5–40.4) | 25.5 (22.5–28.5) | 29.0 (26.6–31.4) | 38.2 (35.2–41.2) | <0.0001 |

| Married/living with partner | 47.7 (45.9–49.5) | 42.2 (36.3–48.1) | 54.9 (51.4–58.5) | 51.9 (49.0–54.8) | 40.8 (37.7–43.9) | <0.0001 |

| Separated/divorced/widowed | 20.4 (19.1–21.6) | 22.4 (19.2–25.5) | 19.5 (17.1–22.0) | 19.1 (17.1–21.1) | 21.0 (19.0–23.0) | 0.1745 |

| US born | 20.1 (18.6–21.7) | 13.5 (8.9–18.2) | 14.3 (11.7–16.9) | 19.5 (17.3–21.7) | 27.7 (24.9–30.4) | <0.0001 |

| Residence in US ≥10 years | 70.4 (68.2–72.6) | 57.6 (51.4–63.7) | 67.7 (64.2–71.2) | 72.7 (69.9–75.5) | 74.9 (71.8–78.0) | <0.0001 |

| Immigrant generation (%) | ||||||

| First | 78.6 (77.0–80.2) | 85.0 (80.2–89.7) | 84.7 (82.1–87.4) | 79.0 (76.7–81.3) | 71.2 (68.3–74.0) | <0.0001 |

| Second or higher | 21.4 (19.8–23.0) | 15.0 (10.3–19.8) | 15.3 (12.6–17.9) | 21.0 (18.7–23.3) | 28.8 (26.0–31.7) | <0.0001 |

| Age at immigration (%) | ||||||

| ≤10 years | 13.3 (11.8–14.7) | 10.7 (5.7–15.7) | 10.3 (7.6–13.0) | 13.2 (10.7–15.7) | 17.4 (14.5–20.3) | 0.0017 |

| 11–24 years | 37.8 (36.1–39.5) | 36.8 (30.9–42.6) | 35.1 (31.7–38.5) | 37.6 (34.8–40.4) | 40.5 (37.2–43.7) | 0.1229 |

| 25 years | 49.0 (47.0–50.9) | 52.6 (46.9–58.3) | 54.6 (51.1–58.2) | 49.2 (46.2–52.3) | 42.2 (38.7–45.6) | <0.0001 |

| Age at immigration | 25.7 (25.1–26.3) | 27.6 (26.3–28.9) | 26.5 (25.6–27.3) | 25.2 (24.3–26.1) | 24.5 (23.5–25.6) | 0.0003 |

| Language preference | ||||||

| Spanish | 77.4 (75.6–79.3) | 83.9 (78.6–89.2) | 84.9 (82.2–87.6) | 76.7 (73.8–79.6) | 70.3 (66.8–73.7) | <0.0001 |

| English | 22.6 (20.7–24.4) | 16.1 (10.8–21.4) | 15.1 (12.4–17.8) | 23.3 (20.4–26.2) | 29.7 (26.3–33.2) | <0.0001 |

| SASH language subscale | ||||||

| Low (1 to <3) | 78.7 (76.9–80.5) | 84.8 (80.0–89.6) | 85.4 (82.6–88.2) | 78.3 (75.5–81.0) | 71.8 (68.6–75.1) | <0.0001 |

| High (≥3) | 21.3 (19.5–23.1) | 15.2 (10.4–20.0) | 14.6 (11.8–17.4) | 21.7 (19.0–24.5) | 28.2 (24.9–31.4) | <0.0001 |

| SASH language subscale score | 1.9 (1.8–1.9) | 1.7 (1.6–1.9) | 1.8 (1.7–1.8) | 1.9 (1.8–2.0) | 2.1 (2.0–2.2) | <0.0001 |

| SASH social subscale | ||||||

| Low (1 to <3) | 84.0 (82.7–85.3) | 86.4 (82.2–90.5) | 86.6 (83.8–89.4) | 84.5 (82.4–86.5) | 80.7 (77.6–83.8) | 0.0695 |

| High (≥3) | 16.0 (14.7–17.3) | 13.6 (9.5–17.8) | 13.4 (10.6–16.2) | 15.5 (13.5–17.6) | 19.3 (16.2–22.4) | 0.0695 |

| SASH social subscale score | 2.2 (2.2–2.2) | 2.2 (2.1–2.2) | 2.2 (2.1–2.2) | 2.2 (2.1–2.2) | 2.2 (2.2–2.3) | 0.1815 |

| Health insurance (%) | 51.8 (49.8–53.9) | 50.9 (44.9–56.8) | 53.0 (49.4–56.7) | 47.8 (44.8–50.8) | 55.9 (52.6–59.2) | 0.0009 |

| Total physical activity, MET‐min/day | 437.5 (411.0–464.0) | 414.4 (329.9–498.9) | 401.6 (359.9–443.3) | 446.6 (402.9–490.3) | 447.1 (366.7–527.5) | 0.4932 |

0 RF indicates, no adverse but ≥1 unfavorable risk factor; 1 RF, any single adverse risk factor; 2+ RF, ≥2 adverse risk factors; BMI, body mass index; BP, blood pressure; CVD, cardiovascular disease; LR, low risk; MET, metabolic equivalent; RF, risk factor; SASH, Short Acculturation Scale for Hispanics; US, United States.

All values (except n) were weighted for survey design and nonresponse. All variables (except age) were adjusted for age.

Risk status details are described under “Definition of Risk Factors.”

Among women, those who were LR were, in general, less acculturated than others. LR women, for example, had the lowest age‐adjusted rates of being US born and of having resided in the United States for ≥10 years compared with others (P<0.0001). Foreign‐born LR women also had the highest mean age at immigration (27.6 versus 24.5 years for those with LR and with ≥2 adverse risk factors, respectively; P=0.0003). In contrast, among men, those who were LR were more acculturated; they were least likely to prefer the use of Spanish compared with others and had among the highest proportions of those who were US born or who had resided in the United States for ≥10 years in age‐adjusted analyses. Rates of health insurance were higher among LR men compared with others (59.9%; P=0.0102); conversely, among women, the highest rates of health insurance were reported by those who had ≥2 adverse risk factors (55.9%; P=0.0009).

Tables 7 and 8 provide the prevalence and mean levels of CVD risk factors by CVD risk status for men and women, respectively.

Table 7.

Prevalence and Mean Levels of CVD Risk Factors for Men by CVD Risk Profiles

| CVD Risk Factorsa | CVD Risk Status,b Mean or % (95% CI) | P Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LR | 0 RF | 1 RF | 2+ RF | ||

| Participants, n | 236 | 1347 | 1977 | 2250 | |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL | 159.4 (155.1–163.7) | 186.3 (184.0–188.7) | 194.1 (191.6–196.6) | 209.4 (206.1–212.8) | <0.0001 |

| LDL cholesterol, mg/dL | 93.0 (89.2–96.9) | 116.3 (114.2–118.4) | 122.2 (120.0–124.3) | 130.9 (127.8–134.1) | <0.0001 |

| HDL cholesterol, mg/dL | 49.2 (47.3–51.2) | 46.3 (45.5–47.0) | 44.8 (44.1–45.4) | 43.4 (42.6–44.1) | <0.0001 |

| Triglycerides, mg/dL | 86.5 (77.2–95.9) | 120.8 (114.3–127.3) | 141.0 (135.3–146.8) | 188.0 (177.7–198.2) | <0.0001 |

| Elevated triglycerides (%)c | 9.8 (5.2–14.4) | 22.3 (19.2–25.4) | 32.3 (29.7–34.9) | 50.6 (47.5–53.8) | <0.0001 |

| Systolic BP, mm Hg | 114.6 (113.5–115.7) | 120.6 (119.8–121.4) | 122.1 (121.5–122.8) | 129.1 (128.1–130.2) | <0.0001 |

| Diastolic BP, mm Hg | 63.7 (62.5–64.9) | 70.7 (70.0–71.4) | 73.2 (72.6–73.7) | 78.1 (77.3–78.9) | <0.0001 |

| BMI category (%) | |||||

| Underweight | 8.5 (4.5–12.5) | 0.6 (0.1–1.1) | 0.6 (0.2–1.0) | 0.3 (0.1–0.6) | 0.0001 |

| Normal | 91.5 (87.3–95.7) | 23.3 (20.4–26.2) | 22.4 (19.5–25.3) | 8.1 (6.6–9.5) | <0.0001 |

| Overweight | — | 80.2 (77.2–83.1) | 40.1 (37.4–42.8) | 20.6 (18.0–23.2) | <0.0001 |

| Obese | — | — | 36.9 (34.0–39.8) | 71.0 (68.3–73.8) | <0.0001 |

| BMI | 21.0 (20.6–21.5) | 26.0 (25.8–26.2) | 28.8 (28.5–29.2) | 32.1 (31.8–32.4) | <0.0001 |

| Fasting glucose, mg/dL | 93.7 (92.5–95.0) | 96.5 (95.8–97.2) | 98.8 (98.0–99.7) | 117.5 (114.7–120.3) | <0.0001 |

| Smoking status (%) | |||||

| Never smoker | 87.2 (82.6–91.8) | 73.9 (70.7–77.1) | 46.5 (43.3–49.7) | 35.1 (31.8–38.3) | <0.0001 |

| Former smoker | 21.5 (17.1–25.9) | 29.6 (26.6–32.7) | 21.3 (19.3–23.3) | 19.3 (16.8–21.8) | <0.0001 |

| Current smoker | — | — | 32.2 (29.3–35.1) | 45.7 (42.3–49.1) | <0.0001 |

| Waist/hip ratio | 0.88 (0.87–0.89) | 0.92 (0.92–0.93) | 0.94 (0.94–0.95) | 0.97 (0.97–0.98) | <0.0001 |

| Central obesity (%)d | 30.8 (25.0–36.6) | 63.4 (59.9–67.0) | 77.3 (74.6–80.0) | 87.2 (85.3–89.1) | <0.0001 |

| Waist circumference, cm | 80.2 (79.0–81.3) | 91.1 (90.6–91.7) | 98.1 (97.2–99.0) | 106.2 (105.5–107.0) | <0.0001 |

| Waist circumference >102 cm | — | 5.9 (4.3–7.5) | 34.5 (31.6–37.4) | 62.9 (59.7–66.0) | <0.0001 |

0 RF indicates, no adverse but ≥1 unfavorable risk factor; 1 RF, any single adverse risk factor; 2+ RF, ≥2 adverse risk factors; BMI, body mass index; BP, blood pressure; CVD, cardiovascular disease; HDL, high‐density lipoprotein; LDL, low‐density lipoprotein; LR, low risk; RF, risk factor; —, cannot be estimated.

All values (except n) were weighted for survey design and nonresponse.

Risk status details are described under “Definition of Risk Factors.” To convert total, LDL, and HDL cholesterol to mmol/L, multiply by 0.0259; to convert glucose to mmol/L, multiply by 0.0555.

Elevated triglyceride levels were defined as triglycerides ≥150 mg/dL.

Central obesity was defined as waist/hip ratio ≥0.85 for women, ≥0.90 for men.

Table 8.

Prevalence and Mean Levels of CVD Risk Factors for Women by CVD Risk Profiles

| CVD Risk Factorsa | CVD Risk Status,b Mean or % (95% CI) | P Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LR | 0 RF | 1 RF | 2+ RF | ||

| Participants, n | 623 | 1851 | 3059 | 3414 | |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL | 170.4 (168.0–172.9) | 190.4 (188.4–192.4) | 193.7 (191.9–195.6) | 205.0 (202.6–207.5) | <0.0001 |

| LDL cholesterol, mg/dL | 96.7 (94.5–98.9) | 115.2 (113.5–116.8) | 119.2 (117.6–120.8) | 128.1 (125.9–130.2) | <0.0001 |

| HDL cholesterol, mg/dL | 58.6 (57.2–60.0) | 54.5 (53.6–55.4) | 50.8 (50.1–51.5) | 48.3 (47.6–49.1) | <0.0001 |

| Triglycerides, mg/dL | 76.0 (72.7–79.3) | 103.9 (100.5–107.2) | 118.8 (115.3–122.3) | 144.6 (139.5–149.8) | <0.0001 |

| Elevated triglycerides (%)c | 6.2 (4.4–8.0) | 15.5 (13.2–17.9) | 22.6 (20.5–24.7) | 36.6 (33.8–39.3) | <0.0001 |

| Systolic BP, mm Hg | 110.9 (109.8–112.0) | 112.9 (112.2–113.7) | 114.3 (113.7–114.8) | 122.6 (121.6–123.6) | <0.0001 |

| Diastolic BP, mm Hg | 63.4 (62.6–64.1) | 67.8 (67.2–68.4) | 70.9 (70.4–71.4) | 75.5 (74.8–76.2) | <0.0001 |

| BMI category (%) | |||||

| Underweight | 7.9 (4.9–10.9) | 0.2 (0.0–0.5) | 1.2 (0.4–2.0) | 0.5 (0.1–0.9) | <0.0001 |

| Normal | 94.1 (90.9–97.4) | 22.5 (19.7–25.2) | 14.8 (12.9–16.7) | 5.1 (3.7–6.5) | <0.0001 |

| Overweight | — | 80.2 (77.4–82.9) | 27.6 (25.4–29.7) | 15.4 (13.3–17.5) | <0.0001 |

| Obese | — | — | 56.4 (53.9–59.0) | 79.0 (76.6–81.4) | <0.0001 |

| BMI | 20.9 (20.6–21.2) | 26.1 (25.9–26.3) | 30.9 (30.6–31.3) | 34.3 (33.8–34.7) | <0.0001 |

| Fasting glucose, mg/dL | 89.8 (88.8–90.9) | 91.2 (90.7–91.8) | 94.7 (93.5–96.0) | 113.2 (110.4–115.9) | <0.0001 |

| Smoking status (%) | |||||

| Never smoker | 96.1 (92.7–99.5) | 90.5 (88.2–92.7) | 68.1 (65.5–70.7) | 51.4 (48.3–54.4) | <0.0001 |

| Former smoker | 12.0 (8.9–15.1) | 12.0 (9.9–14.2) | 14.0 (12.4–15.6) | 11.3 (9.5–13.0) | 0.1196 |

| Current smoker | — | — | 17.9 (15.8–20.0) | 37.4 (34.3–40.4) | <0.0001 |

| Waist/hip ratio | 0.85 (0.84–0.85) | 0.87 (0.87–0.88) | 0.90 (0.90–0.90) | 0.92 (0.91–0.92) | <0.0001 |

| Central obesity (%)d | 43.4 (38.5–48.2) | 65.9 (62.6–69.2) | 77.4 (75.0–79.7) | 83.0 (80.6–85.4) | <0.0001 |

| Waist circumference, cm | 77.9 (77.2–78.7) | 88.8 (88.1–89.5) | 98.7 (98.0–99.4) | 106.0 (105.1–106.9) | <0.0001 |

| Waist circumference >88 cm | 13.2 (9.8–16.6) | 61.0 (57.7–64.2) | 81.3 (79.3–83.4) | 91.6 (89.6–93.6) | <0.0001 |

0 RF indicates, no adverse but ≥1 unfavorable risk factor; 1 RF, any single adverse risk factor; 2+ RF, ≥2 adverse risk factors; BMI, body mass index; BP, blood pressure; CVD, cardiovascular disease; HDL, high‐density lipoprotein; LDL, low‐density lipoprotein; LR, low risk; RF, risk factor; —, cannot be estimated.

All values (except n) were weighted for survey design and nonresponse.

Risk status details are described under “Definition of Risk Factors.” To convert total, LDL, and HDL cholesterol to mmol/L, multiply by 0.0259; to convert glucose to mmol/L, multiply by 0.0555.

Elevated triglyceride levels were defined as triglycerides ≥150 mg/dL.

Central obesity was defined as waist/hip ratio ≥0.85 for women, ≥0.90 for men.

Unfavorable or Borderline Risk Status

Age‐adjusted prevalence of unfavorable or borderline risk (ie, neither LR nor high risk) was 24.9% and 24.1% among men and women, respectively, and ranged from 20.1% (Puerto Rican background) to 36.3% (South American background) among men (Figure — Panel A) and from 14.6% (Puerto Rican background) to 33.1% (South American background) among women (Figure — Panel B). The majority of participants with unfavorable risk status were overweight (80.2% for both men and women). Furthermore, about 51.7% of men and 26.5% of women with unfavorable risk status had unfavorable BP levels; 38.2% and 40.6%, respectively, had unfavorable cholesterol levels; and 38.6% and 27.5%, respectively, had unfavorable glucose levels (data not shown).

Men characterized as being at unfavorable risk were, in general, less acculturated than other men. Overall, 81.6% of men at unfavorable risk reported preferring Spanish (versus English), and 66.5% had lived in the United States for ≥10 years compared with 71.7% and 76.8%, respectively, of men with ≥2 adverse risk factors (P<0.0001) (Table 5).

Discussion

Among the adult Hispanic/Latino men and women who participated in HCHS/SOL, age‐adjusted prevalence of LR status was low, especially among men (5.1% of men and 11.2% of women). LR prevalence varied by Hispanic/Latino background. Among men, LR prevalence was highest among those with Central American backgrounds and lowest among those with Mexican and Dominican backgrounds, although the magnitude of variation was small (ie, only a 3–percentage point difference between the highest‐ and lowest‐prevalence groups). Among women, LR prevalence showed somewhat greater variation and was highest among those with Cuban and South American backgrounds and lowest among those with Puerto Rican backgrounds. On average, LR adults were younger and more educated (particularly women) compared with others. Being less acculturated was consistently associated with a LR profile among women, but no significant associations were seen among men. Conversely, prevalence of unfavorable or borderline CVD risk was relatively high and correlated with less acculturation among men only.

Sex differences in both the prevalence of CVD risk factors and the timing of onset of CVD have been extensively described,18, 19, 20 and among women, worsening of CVD risk has been noted with menopause.20, 21 Consequently, it is not surprising that in the current study, differences in LR prevalence between men and women were observed primarily at younger ages (8.1% of men and 17.9% of women), with similar low prevalence of LR among those aged 45 to 74 years (1.4% of men and 1.2% of women). Examination of individual favorable risk factors across age–sex strata suggested that changes in lipid profiles (and, to a smaller extent, BMI) may underlie changes in patterns of sex differences in LR prevalence with age. These findings may be explained by the cardioprotective effects of endogenous estrogen prior to menopause and the unfavorable effect of menopause on lipid metabolism in women.21, 22

These findings on LR prevalence among diverse US Hispanic/Latino adults extend the findings of previous studies on adverse risk factors among US Hispanic/Latino adults23, 24, 25, 26, 27 and our earlier report on adverse CVD risk factors in the HCHS/SOL cohort.1 Previous large‐scale prospective studies have demonstrated multiple beneficial outcomes of low CVD risk status2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 that may exceed what would be expected from simply the absence of high CVD risk. Increasing the proportion of LR adults may yield additional health benefits beyond effective CVD prevention. Documentation of LR prevalence among this growing segment of US society is necessary to accurately estimate the magnitude of improvement in risk and future burden of disease among Hispanic/Latino adults with unfavorable or adverse levels of CVD risk factors.

National studies that have reported LR prevalence in the US Hispanic/Latino population included primarily Mexican American adults. Age‐adjusted LR prevalence (using a definition similar to ours) was 5.3% in 1999–2004 among Mexican American adults from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) compared with 8.2% for non‐Hispanic white adults (7.5% for the US population overall).9 An analysis of NHANES 2003–2008 data (using the AHA Life's Simple 7 definition) found that <1% of adults in each major US racial/ethnic group (including Mexican American adults) had ideal levels of all 7 cardiovascular health components (5 major CVD risk factors plus physical activity and healthy diet).28

The current findings of variation in LR prevalence across Hispanic/Latino backgrounds challenge the validity of extending findings based on data solely from Mexican American adults to the wider US Hispanic/Latino population. In the current study, men with Dominican and Mexican backgrounds had the lowest LR prevalence, whereas among women, those with Puerto Rican backgrounds had the lowest LR prevalence. Men with Mexican backgrounds and women with Puerto Rican backgrounds had the lowest rates of multiple favorable risk factors, explaining the particularly low prevalence of LR status in these groups; however, differences in LR prevalence by background were small, particularly among men, as was the prevalence of LR overall.

Although some previous studies have suggested that foreign‐born Mexican American adults may have more favorable risk status compared with those who were US born,29, 30 this finding has not been observed consistently.31 Kershaw et al reported that foreign‐born Mexican Americans adults had almost 3 times higher odds of being LR compared with US‐born Mexican American adults.29 Moreover, compared with US‐born Mexican American adults, the odds of being LR were >4 times higher among foreign‐born Mexican American adults who had resided in the United States for <10 years. In contrast, foreign‐born Mexican American adults with ≥10 years of residence in the United States had 1.61 times higher odds of being LR compared with US‐born Mexican American adults.29 The current findings on the association of measures of acculturation with LR status are consistent with the “healthy migrant hypothesis” (ie, that persons who choose to migrate to a different country are selectively healthier than nonmigrants),32 although some studies have found only weak evidence to support this hypothesis.31

Acculturation is a multifaceted process that has been shown to exert parallel effects that may be both detrimental (ie, adoption of Western lifestyles) and beneficial (improved socioeconomic status and access to care). The current findings also suggest that the complex effects of acculturation may differ by sex or that as yet unmeasured factors associated with retaining Hispanic culture may also be associated with health benefits among women only. In addition, it is possible that the relatively higher LR prevalence seen among some Hispanic/Latino backgrounds (eg, Cuban and South American women) in HCHS/SOL may, to some extent, be a reflection of the comparatively lower rates of acculturation experienced by these groups.1 For example, the proportion of HCHS/SOL participants who lived in the United States for >10 years was lowest among those with Cuban backgrounds (45.1%), followed by those with South American backgrounds (53.9%).1 Those with Cuban and South American backgrounds also included the highest proportions of adults who reported preferring the use of Spanish to English.1 Given the cross‐sectional nature of these analyses, it is also possible that variations seen across backgrounds are a reflection of differences in immigration patterns over time. Adjustment for proxy measures of acculturation such as duration of residence in the United States and language preference did not alter the findings. Adding to the complexity of these findings, although women with Cuban backgrounds had among the highest prevalence of LR status, they also had the highest rates of having ≥2 adverse risk factors. This result is consistent with our current findings that although this group had the highest rate of ideal BMI and among the highest rates of ideal glucose status, these participants also experienced high rates of adverse risk factors such as cigarette smoking, hypertension, and hypercholesterolemia.1 Further research is needed to shed light on specific aspects of diverse Hispanic/Latino cultures that may exert a health‐protective effect and to characterize the effects of acculturation by sex and ethnic background.

In light of the low rates of LR among Hispanic/Latino men and women overall, it is important to note the sizeable prevalence of unfavorable or borderline risk status: almost 1 in 4 Hispanic/Latino adult men and women overall (ranging from ≈15% of Puerto Rican women to ≈36% in South American men). These groups represent at‐risk (but not yet high‐risk) segments of the US Hispanic/Latino population that could benefit from primary preventive efforts without necessarily needing pharmaceutical intervention. These adults present an expedient and urgent opportunity to increase the proportion of the population at LR through timely implementation of interventions emphasizing overall healthy lifestyles and nutritional hygiene. In contrast, these findings on rates of LR and unfavorable risk status reveal a bleaker picture of CVD health among Hispanic/Latino adults than reported earlier. Among HCHS/SOL participants without any adverse CVD risk factors,1 for example, a sizeable proportion did not have favorable CVD risk profiles. Moreover, the current analyses show that among the participant groups with the highest prevalence of no adverse CVD risk factors, South American men (19.4%) and women (30.4%),1 only ≈7% and 14%, respectively, were LR. Consequently, the high prevalence of unfavorable risk is a sobering indication of the possibility that as the currently young Hispanic/Latino population ages, it may be burdened by even higher rates of adverse CVD risk profiles. The fact that almost half of men and more than half of women at unfavorable risk reported having no health insurance coverage underscores the importance of public health initiatives to identify persons who are at risk of developing adverse CVD risk factors.

The cross‐sectional nature of the analyses is a limitation of this study. Nevertheless, these findings are novel and of public health importance. Although the different countries in Central and South America have unique ethnic and cultural characteristics, adults with Central and South American backgrounds were grouped into these 2 broad categories. Nevertheless, HCHS/SOL data allow a level of granularity in examining the US Hispanic/Latino population by ethnic background and other characteristics that was unavailable previously. In addition, electrocardiograms may not always be accurate in evaluating a history of previous myocardial infarction because ECG changes may revert back to normal over time in a sizeable proportion of persons with a history of myocardial infarction.33, 34 Nevertheless, it is unlikely that this issue affected our estimates because adults with favorable levels of all major CVD risk factors (without use of medications to control risk factor levels) are unlikely to have had a previous myocardial infarction.

In conclusion, these findings demonstrate the low prevalence of favorable CVD risk profile among all major US Hispanic/Latino groups and the urgent need for comprehensive public health interventions and policies to lower CVD risk in this growing population. Further research is also needed to understand the mechanisms underlying the complex effects of acculturation on diverse Hispanic/Latino men and women.

Sources of Funding

The Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos was carried out as a collaborative study supported by contracts from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) to the University of North Carolina (N01‐HC65233), University of Miami (N01‐HC65234), Albert Einstein College of Medicine (N01‐HC65235), Northwestern University (N01‐HC65236), and San Diego State University (N01‐HC65237). The following Institutes/Centers/Offices contribute to the HCHS/SOL through a transfer of funds to the NHLBI: National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities, the National Institute of Deafness and Other Communications Disorders, the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, and the Office of Dietary Supplements.

Disclosures

None.

Supporting information

Table S1. Unweighted Cell Counts Corresponding to Weighted Prevalence in Table 2 (Age‐Stratified Prevalence of Low‐Risk Status by Sex and Hispanic/Latino Background)

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the staff and participants of HCHS/SOL for their contributions. A complete list of staff and investigators has been provided by Sorlie et al in Ann Epidemiol. 2010 Aug; 20:642–649 and is also available on the study website http://www.cscc.unc.edu/hchs/.

(J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5:e003929 doi: 10.1161/JAHA.116.003929)

References

- 1. Daviglus ML, Talavera GA, Aviles‐Santa ML, Allison M, Cai J, Criqui MH, Gellman M, Giachello AL, Gouskova N, Kaplan RC, LaVange L, Penedo F, Perreira K, Pirzada A, Schneiderman N, Wassertheil‐Smoller S, Sorlie PD, Stamler J. Prevalence of major cardiovascular risk factors and cardiovascular diseases among Hispanic/Latino individuals of diverse backgrounds in the United States. JAMA. 2012;308:1775–1784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Daviglus ML, Liu K, Greenland P, Dyer AR, Garside DB, Manheim L, Lowe LP, Rodin M, Lubitz J, Stamler J. Benefit of a favorable cardiovascular risk‐factor profile in middle age with respect to Medicare costs. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:1122–1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Daviglus ML, Liu K, Pirzada A, Yan LL, Garside DB, Feinglass J, Guralnik JM, Greenland P, Stamler J. Favorable cardiovascular risk profile in middle age and health‐related quality of life in older age. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:2460–2468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Daviglus ML, Liu K, Pirzada A, Yan LL, Garside DB, Greenland P, Manheim LM, Dyer AR, Wang R, Lubitz J, Manning WG, Fries JF, Stamler J. Cardiovascular risk profile earlier in life and Medicare costs in the last year of life. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:1028–1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Daviglus ML, Pirzada A, Liu K, Yan LL, Garside DB, Dyer AR, Hoff JA, Kondos GT, Greenland P, Stamler J. Comparison of low risk and higher risk profiles in middle age to frequency and quantity of coronary artery calcium years later. Am J Cardiol. 2004;94:367–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Daviglus ML, Stamler J, Pirzada A, Yan LL, Garside DB, Liu K, Wang R, Dyer AR, Lloyd‐Jones DM, Greenland P. Favorable cardiovascular risk profile in young women and long‐term risk of cardiovascular and all‐cause mortality. JAMA. 2004;292:1588–1592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Stamler J, Stamler R, Neaton JD, Wentworth D, Daviglus ML, Garside D, Dyer AR, Liu K, Greenland P. Low risk‐factor profile and long‐term cardiovascular and noncardiovascular mortality and life expectancy: findings for 5 large cohorts of young adult and middle‐aged men and women. JAMA. 1999;282:2012–2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lloyd‐Jones DM, Hong Y, Labarthe D, Mozaffarian D, Appel LJ, Van Horn L, Greenlund K, Daniels S, Nichol G, Tomaselli GF, Arnett DK, Fonarow GC, Ho PM, Lauer MS, Masoudi FA, Robertson RM, Roger V, Schwamm LH, Sorlie P, Yancy CW, Rosamond WD; on behalf of the American Heart Association Strategic Planning Task Force and Statistics Committee . Defining and setting national goals for cardiovascular health promotion and disease reduction. The American Heart Association's Strategic Impact Goal through 2020 and beyond. Circulation. 2010;121:586–612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ford ES, Li C, Zhao G, Pearson WS, Capewell S. Trends in the prevalence of low risk factor burden for cardiovascular disease among United States adults. Circulation. 2009;120:1181–1188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lavange LM, Kalsbeek WD, Sorlie PD, Aviles‐Santa LM, Kaplan RC, Barnhart J, Liu K, Giachello A, Lee DJ, Ryan J, Criqui MH, Elder JP. Sample design and cohort selection in the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos. Ann Epidemiol. 2010;20:642–649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sorlie PD, Aviles‐Santa LM, Wassertheil‐Smoller S, Kaplan RC, Daviglus ML, Giachello AL, Schneiderman N, Raij L, Talavera G, Allison M, Lavange L, Chambless LE, Heiss G. Design and implementation of the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos. Ann Epidemiol. 2010;20:629–641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Marin G, Sabogal F, Marin BV, Otero‐Sabogal R, Perez‐Stable EJ. Development of a short acculturation scale for Hispanics. Hisp J Behav Sci. 1987;9:183–205. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Friedewald WT, Levy RI, Fredrickson DS. Estimation of the concentration of low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol in plasma, without use of the preparative ultracentrifuge. Clin Chem. 1972;18:499–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, Cushman WC, Green LA, Izzo JL Jr, Jones DW, Materson BJ, Oparil S, Wright JT Jr, Roccella EJ. The seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure: the JNC 7 report. JAMA. 2003;289:2560–2572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults . Executive summary of the Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). JAMA. 2001;285:2486–2497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. NHLBI Obesity Education Initiative Expert Panel on the Identification, Evaluation, and Treatment of Overweight and Obesity in Adults . Clinical guidelines on the identification, evaluation, and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults—the evidence report. NIH Publication No. 98‐4083, Bethesda, MD, September 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 17. American Diabetes Association . Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:S62–S69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mosca L, Barrett‐Connor E, Kass Wenger N. Sex/gender differences in cardiovascular disease prevention: what a difference a decade makes. Circulation. 2011;124:2145–2154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Appelman Y, van Rijn BB, Ten Haaf ME, Boersma E, Peters SA. Sex differences in cardiovascular risk factors and disease prevention. Atherosclerosis. 2015;241:211–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Vaccarino V, Badimon L, Corti R, de Wit C, Dorobantu M, Hall A, Koller A, Marzilli M, Pries A, Bugiardini R. Ischaemic heart disease in women: are there sex differences in pathophysiology and risk factors? Position paper from the working group on coronary pathophysiology and microcirculation of the European Society of Cardiology. Cardiovasc Res. 2011;90:9–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Matthews KA, Meilahn E, Kuller LH, Kelsey SF, Caggiula AW, Wing RR. Menopause and risk factors for coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med. 1989;321:641–646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Epstein FH, Mendelsohn ME, Karas RH. The protective effects of estrogen on the cardiovascular system. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1801–1811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mitchell BD, Stern MP, Haffner SM, Hazuda HP, Patterson JK. Risk factors for cardiovascular mortality in Mexican American and non‐Hispanic Whites. The San Antonio Heart Study. Am J Epidemiol. 1990;131:423–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sundquist J, Winkleby MA. Cardiovascular risk factors in Mexican American adults: a transcultural analysis of NHANES III, 1988–1994. Am J Public Health. 1999;89:723–730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Crespo CJ, Loria CM, Burt VL. Hypertension and other cardiovascular disease risk factors among Mexican Americans, Cuban Americans, and Puerto Ricans from the Hispanic Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Public Health Rep. 1996;111:S7–S10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Stern MP, Gasken SP, Allen CR, Garza V, Gonzales JL, Waldrop RH. Cardiovascular risk factors in Mexican Americans in Laredo, Texas I. Prevalence of overweight and diabetes and distributions of serum lipids. Am J Epidemiol. 1981;113:546–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hanis CL, Ferrell RE, Barton SA, Aguilar L, Garzaibarra A, Tulloch BR, Garcia CA, Schull WJ. Diabetes among Mexican Americans in Starr County, Texas. Am J Epidemiol. 1983;118:659–672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Shay CM, Ning H, Allen NB, Carnethon MR, Chiuve SE, Greenlund KJ, Daviglus ML, Lloyd‐Jones DM. Status of cardiovascular health in US adults. Prevalence estimates from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES) 2003–2008. Circulation. 2012;125:45–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kershaw KN, Greenlund KJ, Stamler J, Shay CM, Daviglus ML. Understanding ethnic and nativity‐related differences in low cardiovascular risk status among Mexican‐Americans and non‐Hispanic Whites. Prev Med. 2012;55:597–602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Crimmins EM, Kim JK, Alley DE, Karlamangla A, Seeman T. Hispanic paradox in biological risk profiles. Am J Public Health. 2007;97:1305–1310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Rubalcava LN, Teruel GM, Thomas D, Goldman N. The healthy migrant effect: new findings from the Mexican Family Life Survey. Am J Public Health. 2008;98:78–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Abraido‐Lanza AF, Dohrenwend BP, Ng‐Mak DS, Turner JB. The Latino mortality paradox: a test of the “salmon bias” and healthy migrant hypotheses. Am J Public Health. 1999;89:1543–1548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Cox CB. Return to normal of the electrocardiogram after myocardial infarction. Lancet. 1967;289:1194–1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Karnegis JN, Matts J, Tuna N; Group P . Development and evolution of electrocardiographic Minnesota Q‐QS codes in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Am Heart J. 1985;110:452–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Unweighted Cell Counts Corresponding to Weighted Prevalence in Table 2 (Age‐Stratified Prevalence of Low‐Risk Status by Sex and Hispanic/Latino Background)