Abstract

A 68-year-old previously healthy man presented with increasing right hip pain of 6 months duration. On examination he was found to have a hard mass in the right hip arising from the pelvic bone. Imaging studies were in keeping with a sarcoma arising from the right iliac bone. However, biopsy of this bony lesion confirmed this to be a metastatic adenocarcinoma rather than a primary bone malignancy. Further imaging and a subsequent colonoscopy revealed the primary to be a colonic adenocarcinoma. The unique and unusual nature of this case was the presentation as a solitary bony metastasis from a colonic primary. There is no previously documented report in the literature of such a rare presentation of a colonic adenocarcinoma as a solitary bony lesion mimicking a primary sarcoma in the absence of other signs or symptoms.

Keywords: hip, metastasis, pelvic, adenocarcinoma, colon, solitary

INTRODUCTION

We present a rare and unique case of right hip pain which was secondary to a solitary bone metastasis from an asymptomatic primary colonic tumour.

CASE REPORT

A 68-year-old man with no significant medical problems was referred by his primary care physician with a 6-month history of a painful right hip. The pain was localized above the right hip joint and a mass with bony consistency was palpable just above the anterior superior iliac spine. On pelvic x-ray (Fig. 1) an exostosis overlying the lateral superior border of the right iliac bone was seen and radiological features on magnetic resonance imaging scan (Fig. 2) were in keeping with an osteosarcoma. Biochemical markers including a serum prostate specific antigen concentration was within normal limits. Subsequent biopsy and histopathological analysis of this lesion performed at the regional sarcoma centre showed this to be an adenocarcinoma of metastatic origin. On further staining there were features to suggest mucin production and it was positive for cytokeratin 20 (CK20) and caudal type homeobox transcription factor 2 (CDX2) suggesting a colorectal origin (Figs 3 and 4) thereby ruling out a sarcoma. CK20 is a marker of intestinal differentiation, and its expression is highly characteristic of colorectal primary. CDX2 protein is a member of the homeobox genes that encodes an intestine-specific transcription factor and it is an excellent marker for adenocarcinomas arising from the colon.

Figure 1:

X-ray pelvis showing exostosis of the right iliac bone

Figure 2:

MRI right hip showing an exophytic, septated, lobulated mass in the right iliac bone

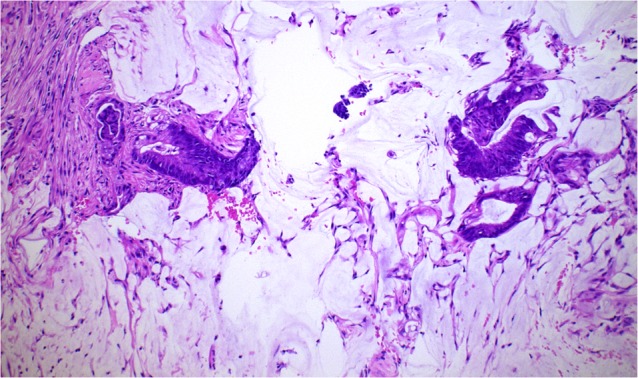

Figure 3:

Bone tumour biopsy haematoxylin and eosin staining, magnification ×200

Figure 4:

Bone tumour biopsy CDX2, magnification ×200

Staging computerized tomography scanning of the chest, abdomen and pelvis (Fig. 5) did not reveal a primary source but identified thickening of the ascending colon. A subsequent colonoscopy (Figs 6 and 7) identified this thickened area as a hepatic flexure adenocarcinoma with mucin production confirmed on histopathological analysis (Figs 8 and 9). Comparison with the histopathology from the bone biopsy confirmed that the bone lesion was a secondary deposit from the colonic adenocarcinoma. Our patient did not have any other clinical or radiological evidence of metastatic spread to other organs like liver, lung or indeed other bones. On further analysis of the colonic tumour it was found that there was no pathogenic mutation in the K-RAS and N-RAS gene.

Figure 5:

CT abdomen demonstrating thickening of the ascending colon

Figure 6:

Colonoscopy showing an ulcerated, fungating, circumferential tumour at the hepatic flexure

Figure 7:

Colonoscopy showing a partially obstructing oozing tumour at the hepatic flexure

Figure 8:

Colon tumour biopsy haematoxylin and eosin staining, magnification ×50

Figure 9:

Colon tumour biopsy haematoxylin and eosin staining with mucin, magnification ×100

This is a report of an unusual presentation of metastatic colonic cancer as a solitary bony lesion mimicking a sarcoma. The patient was subsequently referred to the local oncological services and has since been commenced on palliative chemotherapy. He has remained well, tolerated chemotherapy without undue side effects and is due a computed tomography scan to assess response to chemotherapy. Radiotherapy to the bony metastasis has been planned at a later stage.

DISCUSSION

In the United Kingdom colorectal cancer (CRC) is the fourth most common cancer in adult men and women [1]. Typical symptoms and signs associated with CRC such as hematochezia, malaena, abdominal pain, unexplained iron deficiency anaemia or change in bowel habits [2] are often rare in the majority of patients with early CRC. CRC can spread via lymphatics, haematogenous route, as well as by contiguous and transperitoneal routes. The most common metastatic sites are the regional lymph nodes, liver, lung and peritoneum[3]. Patients may present with signs or symptoms referable to any of these sites.

Metastatic bony lesions from a large bowel primary are usually multiple and occur late in the course of the disease. They usually involve the axial skeleton and the proximal segments of the limbs. In a large retrospective multicenter observational study by Santini et al. [4] about the natural history of bone metastasis in colorectal cancer, majority of patients had bone metastases primarily to the spinal column with vertebral involvement in 65%, 34% had metastatic disease to the hip or pelvis, 26% had metastatic disease to the long bones and 17% had osseous metastasis in other sites (hands, feet and skull). Osseous metastases to the vertebrae, pelvis, and sacrum are blood borne through the paravertebral venous plexus of Baston [5]. The direct spread of prostatic, mammary and gastrointestinal carcinoma to the vertebral venous plexus of Baston explains the high frequency of vertebral bony metastases in these primary tumours.

Incidence of bone metastasis in patients with CRC reported in the English literature is between 4.7% and 10.9% in clinical cases and upto 23.7% in autopsy cases [6].

Solitary skeletal metastases from a primary colonic carcinoma is a rare event. Kanthan et al. [7] in their retrospective review of 5352 patients with primary colorectal cancers found a very low incidence of solitary skeletal metastasis (1.1%). Even this may be an over estimation as the study used bone scans and plain radiography which have low specificity to detect bony lesions.

Roth et al. [8] found that bone metastasis was observed only in the presence of lung and liver metastasis. Isolated bony metastasis was not observed in their cohort of 242 patients with varying stages of colorectal cancer. Cancers which usually metastasize to bone are that arising from the breast, lung, kidney and prostate.

There are differences in metastatic pattern between histological subtypes of CRC. Mucinous adenocarcinomas metastasized to more than one location compared to non-mucin secreting adenocarcinomas. Signet ring cell carcinoma showed evidence of metastasis to rare sites like heart, bone, pancreas and skin [9]. Osteolytic lesions were more prevalent than mixed lesions (81% versus 13% of bone lesions, respectively), and mixed lesions were more prevalent than osteoblastic lesions (6%) in the study conducted by Santini et al. [4].

Other causes of pelvic bone tumours are chondrosarcoma, Ewing‘s sarcoma, osteogenic sarcoma (osteosarcoma of the ischial bone is very rare <1%), fibrosarcoma, Langhans cell histiocytosis, aneurysmal bone cyst, fibrous dysplasia, metastasis and multiple myeloma [10].

And hence histological analysis remains a crucial part of the diagnostic workup of patients with solitary bony lesions as reported in our patient.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None

PATIENT CONSENT

Obtained.

GUARANTOR

Dr Senthil Murugesan, Dr Sachin Bangera

REFERENCES

- 1.Cancer Research UK. Bowel cancer statistics, Cancer Research UK. 2013.

- 2.Hamilton W, Round A, Sharp D, Peters TJ.. Clinical features of colorectal cancer before diagnosis: a population based case control study. Br J Cancer 2005;93:399–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Disibio G, French SW. Metastatic patterns of cancers: results from a large autopsy study. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2008;132:931–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Santini D, Tampellini M, Vincenzi B, Ibrahim T, Ortega C, Virzi V, et al. Natural history of bone metastasis in colorectal cancer: final results of a large Italian bone metastases study. Ann Oncol 2012;23:2072–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baston OV. The function of the vertebral veins and their role in the spread of metastases. Ann Surg 1940;112:138–149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Katoh M, Unakami M, Hara M, Fukuchi S.. Bone metastasis from a colorectal cancer in autopsy cases. J Gastroenterol 1995;30:615–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kanthan R, Loewy J, Kanthan SC.. Skeletal metastases in colorectal carcinomas: a Saskatchewan profile. Dis Colon Rectum 1999;42:1592–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roth ES, Fetzer DT, Barron BJ, Joseph UA, Gayed IW, Wan DQ. Does colon cancer ever metastasize to bone first? a temporal analysis of colorectal cancer progression. BMC Cancer 2009;9:274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hugen N, van de Velde CJH, de Wilt JHW, Nagtegaal. ID.. Metastatic pattern in colorectal cancer is strongly influenced by histological subtype. Ann Oncol . 2014;25:651–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bloem JL, Reidsma II. Bone and soft tissue tumors of hip and pelvis. Eur J Radiol 2012;81:3793–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]