Abstract

Purpose

Recent advances in imaging, use of prognostic indices, and molecular profiling techniques have the potential to improve disease characterization and outcomes in lymphoma. International trials are under way to test image-based response–adapted treatment guided by early interim positron emission tomography (PET) –computed tomography (CT). Progress in imaging is influencing trial design and affecting clinical practice. In particular, a five-point scale to grade response using PET-CT, which can be adapted to suit requirements for early- and late-response assessment with good interobserver agreement, is becoming widely used both in practice- and response-adapted trials. A workshop held at the 11th International Conference on Malignant Lymphomas (ICML) in 2011 concluded that revision to current staging and response criteria was timely.

Methods

An imaging working group composed of representatives from major international cooperative groups was asked to review the literature, share knowledge about research in progress, and identify key areas for research pertaining to imaging and lymphoma.

Results

A working paper was circulated for comment and presented at the Fourth International Workshop on PET in Lymphoma in Menton, France, and the 12th ICML in Lugano, Switzerland, to update the International Harmonisation Project guidance regarding PET. Recommendations were made to optimize the use of PET-CT in staging and response assessment of lymphoma, including qualitative and quantitative methods.

Conclusion

This article comprises the consensus reached to update guidance on the use of PET-CT for staging and response assessment for [18F]fluorodeoxyglucose-avid lymphomas in clinical practice and late-phase trials.

INTRODUCTION

Advances in staging and response assessment of lymphomas have occurred with the introduction of prognostic indices,1–4 molecular profiling,5 and more accurate imaging,6 with the potential to improve disease characterization and treatment selection. The International Harmonisation Project (IHP) first published guidelines about the application of positron emission tomography (PET) using [18F]fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) in lymphoma7 in 2007, and PET was integrated in revised response criteria.8

The field has continued to evolve. PET combined with computed tomography (CT) has replaced PET alone. Mounting evidence supports the central role of PET-CT in staging9–18 and response assessment in Hodgkin (HL)19–27 and non-Hodgkin lymphomas (NHL).28–34 Multiple international studies are under way to investigate whether PET-CT response can be used to guide therapy to improve patient outcomes.35,36 Concerted efforts have been made to standardize PET-CT methods37–41 and interpretation in the context of trials.42 A five-point scale (5-PS), suited to assess differing degrees of response at mid- and end of treatment, has been developed to score images.43 This scale was recommended as the standard reporting tool at the First International Workshop on PET in Lymphoma in Deauville, France, in 2009, and these so-called Deauville criteria have been widely applied in trials in preference to earlier criteria.44–49 Quantitative applications of FDG-PET are also recognized as objective tools for response monitoring,50 although accurate measurement relies on consistent methods for acquisition and processing and rigorous quality assurance of equipment for widespread application.39,51–54

In response to changing requirements for PET-CT, to accommodate assessments at staging and during and after treatment, especially for response-adapted trials, a workshop was convened at the International Conference on Malignant Lymphoma (ICML) in 2011, attended by representatives from major cooperative groups. ICML working groups were established to update guidelines. The imaging group reported to colleagues at follow-up workshops at the Fourth International Workshop on PET in Lymphoma in Menton, France, in 2012 and the 12th ICML in Lugano, Switzerland, in 2013. This article represents the consensus reached regarding the use of PET-CT in lymphoma in clinical practice and late-phase trials.

METHODS

The following areas, pertinent to imaging, were identified as requiring updating at the 2011 workshop:

Relevance of existing imaging staging, including the influence of bulk and assessment of bone marrow involvement

Use of early or interim PET-CT and requirements for standardization of methods, including reporting

Potential prognostic value of quantitative analyses using PET and CT

Experts in nuclear medicine and radiology applied to lymphoma undertook a literature review and shared knowledge about research in progress. Recommendations were formulated as follows (Table 1):

Based on established current knowledge (type 1)

To identify emerging applications (type 2)

To highlight key areas requiring further research (type 3)

Recommendations were presented at the Fourth International Workshop on PET in Lymphoma, and a working paper was circulated for comment and updated after presentation at the 12th ICML.

Table 1.

Summary of Recommendations

| Recommendations |

|---|

Section 1: Interpretation of PET-CT scans

|

Section 2: Role of PET-CT for staging

|

Section 3: Role of interim PET

|

Section 4: Role of PET at end of treatment

|

Abbreviations: ASCT, autologous stem-cell transplantation; CMR, complete metabolic response; CT, computed tomography; DLBCL, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; FDG, [18F]fluorodeoxyglucose; FL, follicular lymphoma; HL, Hodgkin lymphoma; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; NHL, non-Hodgkin lymphoma; PET, positron emission tomography; SUV, standardized uptake value; δSUVmax, change in maximum SUV.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Interpretation of PET-CT Scans

PET-CT is increasingly used for staging and response assessment in lymphoma,6 both for early assessment during treatment,19,20,22–25,28,29,31,55–59 commonly referred to as interim PET-CT (iPET),43 and for remission assessment at the end of treatment.26,27,30,32–34,60,61 Almost all lymphomas are FDG avid62–64 (Table 2), but most published data are related to the use of PET in HL, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), and follicular lymphoma (FL). PET scans are usually reported using visual assessment,43 noting the location of increased focal uptake in nodal and extranodal sites, which is distinguished from physiologic uptake and other patterns of disease with increased FDG uptake including infection and inflammation,68,69 according to distribution and/or CT characteristics.

Table 2.

FDG Avidity According to WHO Classification

| Histology | No. of Patients | FDG Avid (%) |

|---|---|---|

| HL | 489 | 97-100 |

| DLBCL | 446 | 97-100 |

| FL | 622 | 91-100 |

| Mantle-cell lymphoma | 83 | 100 |

| Burkitt's lymphoma | 24 | 100 |

| Marginal zone lymphoma, nodal | 14 | 100 |

| Lymphoblastic lymphoma | 6 | 100 |

| Anaplastic large T-cell lymphoma | 37 | 94-100* |

| NK/T-cell lymphoma | 80 | 83-100 |

| Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma | 31 | 78-100 |

| Peripheral T-cell lymphoma | 93 | 86-98 |

| MALT marginal zone lymphoma | 227 | 54-81 |

| Small lymphocytic lymphoma | 49 | 47-83 |

| Enteropathy-type T-cell lymphoma | 20 | 67-100 |

| Marginal zone lymphoma, splenic | 13 | 53-67 |

| Marginal zone lymphoma, unspecified | 12 | 67 |

| Mycosis fungoides | 24 | 83-100 |

| Sezary syndrome | 8 | 100† |

| Primary cutaneous anaplastic large T-cell lymphoma | 14 | 40-60 |

| Lymphomatoid papulosis | 2 | 50 |

| Subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma | 7 | 71 |

| Cutaneous B-cell lymphoma | 2 | 0 |

Abbreviations: DLBCL, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; FDG, [18F]fluorodeoxyglucose; FL, follicular lymphoma; HL, Hodgkin lymphoma; MALT, mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue; NK, natural killer.

Only 27% of cutaneous sites.

Only 62% of cutaneous sites.

Focal FDG uptake within the bone or bone marrow, liver, and spleen is highly sensitive for involvement in HL70–73 and aggressive NHL74–77 and may obviate the need for bone marrow biopsy.70,78,79 Diffuse increased uptake may occur with abnormal focal uptake, but in HL, diffuse uptake without focal activity often represents reactive hyperplasia70,80 and should not be confused with lymphomatous involvement. PET-CT can miss low-volume involvement, typically < 20% of the marrow,79,80 and coexistent low-grade lymphoma77,81 in DLBCL, although this rarely affects management.79 The sensitivity of PET for diffuse marrow involvement is limited in FL,18 mantle-cell lymphoma, and most indolent lymphomas,77,82 where biopsy is required for staging.

High physiologic FDG uptake occurs in the brain, and although intracerebral lymphoma often shows intense uptake,83 leptomeningeal disease, which may be diffuse and of low volume, may be missed. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is preferred to assess suspected CNS involvement.

PET scans are best reported using a fixed display and color table scaled to the standardized uptake value (SUV)84 to assist with consistency of reporting, for serial scans, and to reduce the effect of patient size. The SUV is the radioactivity most commonly corrected for patient weight and administered activity.

Recommendation.

Staging of FDG-avid lymphomas is recommended using visual assessment, with PET-CT images scaled to a fixed SUV display and color table. Focal uptake in HL and aggressive NHL is sensitive for bone marrow involvement and may obviate the need for biopsy. MRI is the modality of choice for suspected CNS lymphoma (type 1).

Resolution of uptake at sites of initial disease indicates metabolic response.8 Reduction of uptake may also indicate satisfactory response, but the degree of uptake that is indicative of response43 is dependent on the timing of the scan during treatment85,86 and the clinical context, including prognosis, lymphoma subtype,21,30,60 and treatment regimen.22,56 The availability of a baseline scan is considered optimal for the accuracy of subsequent response assessment.40,43,87,88

The IHP criteria7 specified that uptake should be ≤ the mediastinal blood pool for lesions ≥ 2 cm or the adjacent background for smaller lesions to define metabolic response at the end of treatment. In early-response assessment, treatment is incomplete, so the emphasis is on the degree of response and a continuous or close-to-continuous scale is desirable rather than positive or negative response categories.43 Early attempts to address this used three response groups (ie, negative, minimal residual uptake, and positive).19,57,89,90 Further refinement led to the development of the 5-PS,42 which better represents different grades of uptake.

The 5-PS was intended as a simple, reproducible scoring method, with the flexibility to change the threshold between good or poor response according to the clinical context and/or treatment strategy.42 For example, a lower level of FDG uptake might be preferred to define a so-called negative result in a clinical trial exploring de-escalation to avoid undertreatment. A higher level of uptake might be preferred to define a so-called positive result in a trial exploring escalation to avoid overtreatment. The 5-PS has been validated for use at interim25,28,34,44,58,91–93 and the end of treatment34,94 and was adopted as the preferred reporting method at the First International Workshop on PET in Lymphoma in Deauville, France (ie, Deauville criteria),43 and in several international trials.42,44,46–49,95–97

The 5-PS scores the most intense uptake in a site of initial disease, if present, as follows:

1. No uptake

2. Uptake ≤ mediastinum

3. Uptake > mediastinum but ≤ liver

4. Uptake moderately higher than liver

5. Uptake markedly higher than liver and/or new lesions

X. New areas of uptake unlikely to be related to lymphoma

Good interobserver agreement has been reported in HL,42,92,98 DLBCL,93 and FL.34

The UK RAPID (Response Adapted Therapy Using Positron Emission Tomography in Early-Stage Hodgkin Lymphoma) study used the 5-PS in patients with early HL. iPET remained an independent predictor of 3-year progression-free survival (PFS) on multivariable analysis, despite use of a response-adapted design.44 Conservative scoring was used, with a score of 1 or 2 regarded as complete metabolic response (CMR); patients with CMR after three cycles of ABVD (doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine) were randomly assigned to radiotherapy (RT) or no further treatment. Retrospective analysis of an international cohort of 260 patients with advanced HL using scores 1, 2, and 3 to define CMR after two ABVD cycles reported a negative predictive value (NPV) of 94% and positive predictive value (PPV) of 73% for 3-year PFS.25 iPET and end-of-treatment PET using scores 1, 2, and 3 for CMR were both independent predictors of 2-year PFS in a recent prospective study in FL.34 Other studies in HL and NHL have reported that increasing the threshold to define CMR improved the PPV while maintaining a high NPV.28,34,91,92,94

Scores 1 and 2 are therefore considered to represent CMR. Score 3 also likely represents CMR at interim25 and good prognosis at completion of standard treatment.34,94,99 However, in trials where de-escalation is based on PET response, it may be preferable to consider score 3 as inadequate response to avoid undertreatment.42

Recommendation.

The 5-PS is recommended for reporting PET-CT. Results should be interpreted in the context of the anticipated prognosis, clinical findings, and other markers of response. Scores 1 and 2 represent CMR. Score 3 also probably represents CMR in patients receiving standard treatment (type 1).

The terms moderately and markedly were not defined initially, because there were insufficient data to define scores quantitatively.43 Meanwhile, it is suggested according to published data25,34,100 that score 4 be applied to uptake > the maximum SUV in a large region of normal liver and score 5 to uptake 2× to 3× > the maximum SUV in the liver. It is acknowledged that mean liver SUV may be less influenced by image noise than maximum SUV, but reproducibility is more dependent on standardizing the location and size of the region of interest.101 Work is ongoing to assess optimal tumor and liver metrics.102 The liver is also affected by insulin levels, and patient preparation is important with respect to fasting and timing of insulin administration in diabetics.103 It is recognized that in Waldeyer's ring or extranodal sites with high physiologic uptake or with activation within spleen or marrow (eg, with chemotherapy or granulocyte colony-stimulating factor [GCSF]), FDG uptake may be > normal mediastinum and/or liver. In this circumstance, CMR may be inferred if uptake at sites of initial involvement is < surrounding normal tissue, even if the tissue has high physiologic uptake.

Recommendation.

Scores 4 and 5 with reduced uptake from baseline likely represent partial metabolic response, but at the end of treatment, they represent residual metabolic disease. An increase in FDG uptake to a score of 5, score 5 with no decrease in uptake, and new FDG-avid foci consistent with lymphoma represent treatment failure and/or progression (type 2).

Nonspecific FDG uptake may occur with treatment-related inflammation. Patients should be scanned as long after the previous chemotherapy administration as possible for interim assessment. A minimum of 3 weeks, but preferably 6 to 8 weeks, after completion of the last chemotherapy cycle,7 2 weeks after GCSF treatment, or 3 months after RT is recommended.39

Role of PET-CT for Staging

Previous clinical trials have used the Ann Arbor staging system to select patients and report outcomes.104 Currently, prognostic indices are mostly used to risk stratify patients at diagnosis to inform therapy, but most include stage as a factor,1–3,105 so imaging-determined stage remains relevant.

PET-CT using FDG is more accurate than CT for staging in HL9,10,106–111 and NHL,11–13,18,112,113 with increased sensitivity, particularly for extranodal disease.6 Upstaging occurs more often than downstaging, with management alterations in some patients (Table 3). Management change after upstaging is more common in FL14,15 than other lymphomas, especially for patients with limited disease on CT.16,17

Table 3.

Studies Comparing PET or PET-CT With CT Alone for Staging of Lymphomas

| Study | Year | PET or PET-CT | No. of Patients | Disease | Upstaging (%) | Downstaging (%) | Management Change (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bangerter et al106 | 1998 | PET | 44 | HL | 12 | 2 | 14 |

| Partridge et al107 | 2000 | PET | 44 | HL | 41 | 7 | 25 |

| Jerusalem et al108 | 2001 | PET | 33 | HL | 10 | 10 | 3 |

| Weihrauch et al109 | 2002 | PET | 22 | HL | 18 | 0 | 5 |

| Munker et al110 | 2004 | PET | 73 | HL | 29 | 3 | NS |

| Naumann et al111 | 2004 | PET | 88 | HL | 13 | 8 | 20 |

| Hutchings et al9 | 2006 | Mostly PET-CT | 99 | HL | 19 | 5 | 9 |

| Rigacci et al10 | 2007 | Mostly PET | 186 | HL | 14 | 1 | 6 |

| Buchmann et al112 | 2001 | PET | 52 | HL (n = 27), NHL (n = 25) | 8 | 0 | 8 |

| Wirth et al113 | 2002 | PET | 50 | HL (n = 19), NHL (n = 31) | 14 | 0 | 18 |

| Raanani et al11 | 2006 | PET-CT | 103 | HL (n = 32), NHL (n = 68) | 31 | 1 | 25 |

| Elstrom et al12 | 2008 | PET-CT | 61 | HL and NHL | 18 | 0 | 5 |

| Pelosi et al13 | 2008 | PET | 65 | HL (n = 30), NHL (n = 35) | 11 | 5* | 8 |

| Karam et al14 | 2006 | PET | 17 | FL | 41 | 0 | 29 |

| Janikova et al15 | 2008 | Mostly PET | 82 | FL | NS | NS | 18 |

| Wirth et al16 | 2008 | PET | 42 | FL stages I-II on CT | 29 | 0 | 45 |

| Le Dortz et al17 | 2010 | PET-CT | 45 | FL | 8 | 0 | 18 |

| Luminari et al18 | 2013 | PET-CT | 142 | FL | 11 | 1 | NS |

Abbreviations: CT, computed tomography; FL, follicular lymphoma; HL, Hodgkin lymphoma; NHL, non-Hodgkin lymphoma; NS, not stated; PET, positron emission tomography.

False negative.

The intensity of FDG uptake is higher in aggressive than indolent lymphomas, and FDG PET-CT may be used to target biopsy in patients with suspected transformation.65,114,115

Recommendation.

PET-CT should be used for staging in clinical practice and clinical trials, but it is not routinely recommended in lymphomas with low FDG avidity. PET-CT may be used to select the best site to biopsy (type 1).

Role of Contrast-Enhanced CT

The CT part of a PET-CT scan may be performed with contrast enhancement (ceCT) at full dose to obtain a high-quality CT examination or without contrast using a lower dose. Lower-dose CT is used to correct for the attenuation of radioactivity within the patient and to localize abnormalities seen on PET, with less radiation than a full diagnostic examination.84 Whichever protocol is used, CT must be acquired during shallow breathing or end of expiration to avoid misregistration and artifacts.

Direct comparison of unenhanced lower-dose PET-CT and cePET-CT suggests management is rarely altered by ceCT, although ceCT may identify additional findings11,12,116–119 and improve detection of abdominal or pelvic disease.11,116,117 However, full-dose ceCT involves additional radiation, which should be considered when deciding which examination to perform. ceCT is desirable for RT planning performed in the treatment position120 and is required for accurate nodal measurements for trial purposes.

Small errors in the measurement of FDG uptake in tumor may occur with contrast media121 because of an effect on attenuation correction; these errors are unlikely to be clinically important.122 However, contrast may cause errors in comparison of uptake between tumor and reference sites by causing FDG uptake to be overestimated in the mediastinum and liver by 10% to 15%.121 Several organizations (eg, European Association Nuclear Medicine, Society Nuclear Medicine, and Radiological Society North America) recommend that a low-dose CT scan with normal breathing be performed before a PET scan, followed by full diagnostic high-dose ceCT with repositioning of the arms and breath hold, if quantitative measures and ceCT are required.

In practice, many patients undergo separate ceCT before PET-CT. If baseline ceCT demonstrates no additional relevant findings, lower-dose CT during PET-CT examination will be sufficient for response assessment.

Recommendation.

ceCT when used at staging or restaging should ideally occur during a single visit in combination with PET-CT, if not already performed. The baseline findings will determine whether cePET-CT or lower-dose unenhanced PET-CT will suffice for additional imaging examinations (type 2).

Relevance of Initial Disease Bulk

The presence of bulky disease is a negative prognostic factor in some lymphomas.1–3,105 Bulk is considered an adverse factor in early-stage HL123 but not in advanced HL.105 In DLBCL, bulk is predictive of inferior survival in favorable-prognosis disease124,125 but not in poor-prognosis disease, probably because its influence is superseded by other factors reflecting disease burden.126 The longest diameter of the largest involved node is included in the FL International Prognostic Index 2.127 Unidimensional measurements are used for bulk, but these do not assess total tumor burden. Newer methods of contouring are being developed for CT128,129 and PET130,131 to measure the total tumor volume. The prognostic value of these methods remains to be evaluated.

Recommendation.

Bulk remains an important prognostic factor in some lymphomas. Volumetric measurement of tumor bulk and total tumor burden, including methods combining metabolic activity and anatomic size or volume, should be explored as potential prognosticators (type 3).

Role of iPET

Interim imaging is frequently performed in clinical practice and trials and is recommended by some international guidelines.123 The purpose is to ensure the effectiveness of treatment and exclude the possibility of progression. PET-CT shows metabolic response earlier than anatomic response and has the potential to replace CT. Studies have shown that iPET is a strong prognostic indicator in HL19–25,132 and aggressive NHL,28,29,31,55,57,59,133 outperforming the International Prognostic Score22 and International Prognostic Index.57 These findings highlight the potential of using iPET to tailor treatment according to individual response. However, it is important to emphasize that there is no conclusive evidence that changing treatment according to iPET improves outcome,6,35 a question currently being addressed in clinical trials worldwide.35

There is a preponderance of data reporting the predictive value of iPET, most often after two cycles in HL20,22–25 (Appendix Table A1, online only). In DLBCL, early indication of poor response is especially important because salvage treatment of progressive or relapsed disease is less effective in the rituximab era.134 However, although early data favored iPET,55,57,59 more recent data have suggested iPET is less predictive for response with immunochemotherapy30–32,58,135,136 (Appendix Table A2, online only), and end-of-treatment PET is a better predictor.

Visual assessment with iPET in HL results in consistently high NPV, with ≥ 2-year PFS of approximately 95%, and acceptable PPV, with PFS between 13% and 27%,19,22,24,92 for advanced disease treated with ABVD. Initial reports using visual analysis for iPET in DLBCL were favorable,55,57,59 but more recent studies have demonstrated good NPV, with ≥ 2-year PFS rates of 73% to 86% for patients with so-called negative scans, but more variable PPV. PFS for PET-positive patients in recent studies has ranged from 18% to 74%.28–32,93,135–137 The drop in PPV may be related to improved outcomes with rituximab or better supportive care126,138 or may possibly occur because so-called false-positive metabolic activity is more frequent with immunotherapy.30 A different cutoff or combination of factors may be required for modern management of DLBCL.

Recommendation.

If midtherapy imaging is performed, PET-CT is superior to CT alone to assess early response. Trials are evaluating the role of PET response–adapted therapy. Currently, changing treatment solely on the basis of iPET-CT is not recommended, unless there is clear evidence of progression (type 1).

The use of quantitation to improve on visual assessment has been explored in DLBCL. Change in the maximum SUV (δSUVmax) in tumor before and after treatment has been evaluated as a measure of response. Receiver operator curve analysis in 92 patients with DLBCL scanned after two cycles and 80 patients scanned after four identified optimum thresholds for percentage change in SUVmax for predicting event-free survival (EFS).85,86 A retrospective analysis applied to a trial where treatment was adapted according to visual assessment with iPET reported that δSUVmax at two and four cycles was predictive of PFS, whereas visual analysis was not.139 Other groups have also reported that δSUVmax predicts response, but with thresholds ranging from 66% to 91%,58,91,137,139 suggesting that consistency in scanning protocols, matching conditions for serial scans, and proper calibration and scanner maintenance are mandatory for general application.38,39,41,51–53,121,140 The optimum cutoff is also likely influenced by timing, with a tendency for a higher cutoff later during treatment.86 Although the goal of quantitation is more objective assessment, it remains necessary to integrate with clinical information to exclude confounding variables.39

The δSUVmax analysis is being prospectively applied in the PETAL (Positron Emission Tomography Guided Therapy of Aggressive Non-Hodgkin's Lymphomas) and GAINED (GA in Newly Diagnosed Diffuse Large B Cell Lymphoma) studies exploring response-adapted treatment with immunochemotherapy.50 Combining δSUVmax with CT metrics in early nonbulky HL141 and with age-adjusted International Prognostic Index in DLBCL has been reported to improve response prediction.58 Another measure proposed is SUVpeak, a 1-cm3 volume containing the hottest area of tumor,102 which may be less sensitive to noise and resolution and possibly more reproducible. Changes in the metabolic tumor volume (MTV) and total lesion glycolysis (TLG) calculated as MTV × SUVmean are additional exploratory measures.102 However, preliminary reports have suggested changes in MTV and TLG are not predictive in DLBCL.131,142 The results of the UK National Cancer Research Institute PET R-CHOP (rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone) substudy measuring PFS in 200 patients with DLBCL where clinicians were blinded to iPET are awaited.40,143 This and other studies may provide insight into whether quantitation will improve the performance of iPET in DLBCL.139

Recommendation.

Standardization of PET methods is mandatory for the use of quantitative approaches and desirable for routine clinical practice (type 1). Data suggest that quantitative measures (eg, δSUVmax) could be used to improve on visual analysis for response assessment in DLBCL, but this requires further validation in clinical trials (type 2).

Role of PET at the End of Treatment

End-of-treatment remission assessment is more accurate with PET-CT than CT alone in patients with HL,26,60 DLBCL,30,32 and high–tumor burden FL33,34 (Appendix Table A3, online only). High accuracy for PET-CT has been reported in patients after treatment with ABVD26 and BEACOPP (bleomycin, etoposide, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, procarbazine, and prednisone)27 for advanced HL. In a study where PET was used to guide RT, patients treated with BEACOPP (but no RT) with a PET-negative positive response had PFS equivalent to that of patients with complete response (CR) or unconfirmed CR.27 In aggressive NHL, studies involving > 300 patients have reported consistently high NPV of 80% to 100% but more variable PPV of 50% to 100%.30,32,61,135,144,145 In the presence of residual metabolically active tissue, if salvage treatment is being considered, a biopsy may be required. If residual disease is considered unlikely, the scan could be repeated later.

Recommendation.

PET-CT is the standard of care for remission assessment in FDG-avid lymphoma. For HL and DLBCL, in the presence of residual metabolically active tissue, where salvage treatment is being considered, a biopsy is recommended (type 1).

The significance of a residual mass if CMR is achieved is unclear, with some reports suggesting improved outcomes when CMR is associated with a radiologic CR in HL and DLBCL,146–149 whereas others suggest outcomes are unaffected by the presence of a residual mass.23,27,150 It is proposed that the size of the residual mass be recorded where possible, and if relapse occurs, it should be documented whether this occurred within the residual mass.

Recommendation.

Investigation of the significance of PET-negative residual masses should be collected prospectively in clinical trials. Residual mass size and location should be recorded on end-of-treatment PET-CT reports where possible (type 3).

In FL, PET predicts inferior outcomes in patients with high tumor burden who remain PET positive after first-line immunochemotherapy.33,34 Post-treatment PET seems to be a better predictor than iPET.34 Currently, data are insufficient regarding assessment after maintenance therapy.151 This suggests a potential role for PET in evaluating new approaches in response-adapted studies in FL after first-line treatment with rituximab-containing chemotherapy.151

Recommendation.

Emerging data support the use of PET-CT after rituximab-containing chemotherapy in high–tumor burden FL. Studies are warranted to confirm this finding in patients receiving maintenance therapy (type 2).

Assessment Before High-Dose Chemotherapy and Autologous Stem-Cell Transplantation

Various studies have reported that PET-CT using FDG is prognostic in patients with relapsed or refractory HL or DLBCL after salvage chemotherapy before high-dose chemotherapy and autologous stem-cell transplantation (ASCT)152–157 and is superior to CT alone.158 Three-year PFS and EFS rates of 31% to 41% have been reported for patients with PET-positive scans, compared with 75% to 82% for patients with PET-negative scans.152–157

PET may have a role in selecting patients for high-dose chemotherapy and ASCT after salvage treatment159 and in identifying patients with poor prognosis who could benefit from alternative regimens or consolidation.160 PET could also be used as a surrogate end point to test the addition of novel therapies to current reinduction regimens.161

Recommendation.

Assessment with PET-CT could be used to guide decisions before high-dose chemotherapy and ASCT, but additional studies are warranted (type 3).

PET-CT in Subtypes Other Than HL, DLBCL, and FL

Small retrospective studies have suggested that post-treatment scans can predict survival in treatment of mantle-cell lymphoma.65 In primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma, a recent prospective study reported that 54 (47%) of 115 patients achieved CMR after first-line chemotherapy,94 and a PET response–adapted approach is currently being tested (IELSG-37 [International Extranodal Lymphoma Study Group]).48 However, another study involving 51 patients treated with dose-adjusted EPOCH (etoposide, prednisone, vincristine, cyclophosphamide, and doxorubicin) plus rituximab reported that 10 of 15 patients had FDG uptake 6 weeks after treatment, which later diminshed or stabilized, suggesting treatment-related inflammation with this regimen.162 There are limited data regarding T-cell lymphomas, with higher uptake reported in more aggressive subtypes and lower uptake in cutaneous lymphomas.163 In mycosis fungoides, higher uptake has been reported in the presence of large-cell transformation66,163 and extracutaneous disease, which adversely affects prognosis.66,164 There are few data on response assessment; one report in noncutaneous mature natural killer/T-cell lymphoma suggested iPET was predictive of response,165 whereas another found that neither interim nor end-of-treatment PET were predictive.67 Prospective studies are warranted.

DISCUSSION

In response to developments involving PET-CT, recommendations from the ICML imaging group have been made to update practice. These include guidance on reporting of PET-CT for staging and response assessment of HL, DLBCL, and aggressive FL using the 5-PS. PET-CT is recommended for midtreatment assessment in place of CT alone, if imaging is clinically indicated, and for remission assessment. Quantitative imaging parameters for assessing disease burden and response should be explored as potential prognosticators. The standardization of PET-CT methods is mandatory for quantitative analysis and desirable for best clinical practice.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

Presented in part at the Fourth International Workshop on Positron Emission Tomography in Lymphoma, Menton, France, October 3-5, 2012, and 12th International Conference on Malignant Lymphomas, Lugano, Switzerland, June 19-22, 2013.

We thank R. Boellaard, D. Caballero, L. Ceriani, M. Coronado, F. Cicone, A. Gallamini, M. Gregianin, E. Itti, T.A. Lister, C. Moskowitz, H. Schöder, and J. Zijlstra for their contributions to improve the manuscript; Paul Smith, tumor group lead (hematology and brain trials), Cancer Research United Kingdom and University College London Cancer Trials Centre, and the UK National Cancer Research Institute Lymphoma Clinical Study Group for assistance with funding the imaging task group meeting in London, United Kingdom, in 2012; and the European School of Oncology and European Society for Medical Oncology for their support of the workshops at the International Conference on Malignant Lymphoma in 2011 and 2013.

Appendix

Table A1.

Studies Including ≥ 50 Patients With HL Reporting Outcomes According to Visual Assessment With Interim PET

| Study | Year | No. of Patients | Disease Stage | Chemotherapy | No. of Cycles Before PET | No. PET Negative | PFS/EFS |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| At (years) | PET Negative (%) | PET Positive (%) | |||||||

| Hutchings et al19 | 2005 | 85 | I-IV | Mostly ABVD (n = 79) | 2-3 | 72 | 5 | 92 | 39 |

| Hutchings et al20* | 2006 | 77 | I-IV | Mostly ABVD (n = 70) | 2 | 61 | 2 | 96 | 0 |

| Gallamini et al22* | 2007 | 260 | IIB-IV | Mostly ABVD (n = 249) | 2 | 210 | 2 | 96 | 6 |

| Markova et al56 | 2009 | 50 | IIB-IV | BEACOPP | 4 | 36 | 2 | 97 | 86 |

| Cerci et al23* | 2010 | 104 | I-IV | ABVD | 2 | 74 | 3 | 90 | 53 |

| Barnes et al60 | 2011 | 96 | I-II (nonbulky) | ABVD | 2-4 | 79 | 4 | 91 | 87 |

| Zinzani et al24 | 2012 | 304 | I-IIA (n = 147) | ABVD | 2 | 128 | 9 | 95 | 31 |

| IIB-IV (n = 157) | 2 | 123 | 9 | 89 | 29 | ||||

| Biggi et al25 | 2013 | 260 | IIB-IV | ABVD | 2 | 215 | 3 | 95 | 28 |

Abbreviation: ABVD, doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine; BEACOPP, bleomycin, etoposide, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, procarbazine, and prednisone; EFS, event-free survival; HL, Hodgkin lymphoma; PET, positron emission tomography; PFS, progression-free survival.

Prospective study.

Table A2.

Studies Including ≥ 50 Patients With Aggressive NHL Reporting Outcomes According to Visual Assessment With Interim PET

| Study | Year | No. of Patients | Chemotherapy | No. of Cycles of Therapy | No. PET Negative | PFS/EFS |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| At (years) | PET Negative (%) | PET Positive (%) | ||||||

| Spaepen et al59 | 2002 | 70 | Mostly CHOP (n = 56) | 3-4 | 37 | 2 | 85 | 0 |

| Haioun et al55 | 2005 | 90 | CHOP or ACVBP/ACE (n = 53) plus rituximab (n = 37) | 2 | 54 | 2 | 82 | 43 |

| Mikhaeel et al57 | 2005 | 121 | Mostly CHOP (n = 97) | 2-3 | 69 | 5 | 89 | 16 |

| Cashen et al135* | 2011 | 50 | R-CHOP | 2-3 | 26 | 2 | 85 | 63 |

| Micallef et al32* | 2011 | 76 | ER-CHOP | 2 | 60 | 2 | 73 | 60 |

| Yang et al28* | 2011 | 159 | R-CHOP | 3-4 | 116 | 3 | 86 | 29 |

| Yoo et al136 | 2011 | 155 | R-CHOP | 2-4 | 100 | 3 | 84 | 66 |

| Zinzani et al29 | 2011 | 91 | Mostly R-CHOP (n = 66), rituximab (n = 91) | Midtreatment | 56 | 5 | 75 | 18 |

| Safar et al31 | 2012 | 112 | R-CHOP (n = 81), R-ACVBP (n = 31) | 2 | 70 | 3 | 84 | 47 |

| Pregno et al30 | 2012 | 88 | R-CHOP | 2-4 | 66 | 2 | 85 | 72 |

| Nols et al58 | 2013 | 73 | R-CHOP (n = 48), R-miniCHOP (n = 8), ACVBP (n = 17), CHOP (n = 1) | 3-4 | 53 | 2 | 84 | 47 |

Abbreviations: ACE, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, and etoposide; ACVBP, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, bleomycin, and prednisone; CHOP, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone; E, etoposide; EFS, event-free survival; NHL, non-Hodgkin lymphoma; PET, positron emission tomography; PFS, progression-free survival; R, rituximab.

Prospective study.

Table A3.

Studies, Including ≥ 50 With Homogenous Patient Populations With HL or Aggressive NHL or FL, Reporting Outcomes According to Visual Assessment With End-of-Treatment PET

| Study | Year | No. of Patients | Disease and Stage | No. PET Negative | NPV | PPV | FTF/PFS at (years) | PFS/EFS |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PET Negative (%) | PET Positive (%) | ||||||||

| Spaepen K et al: Br J Haematol 115:272-278, 2001 | 2001 | 60 | IIA-IVB HL | 55 | 100 | 91 | 2 | 91 | 0 |

| Cerci et al26* | 2010 | 50 | I-IV HL (patients in CRu/PR on CT) | 23 | 100 | 92 | — | NS | NS |

| Engert et al27*† | 2012 | 739 | IIB-IV HL | 548 | 95 | NA | 5 | 92 | 86† |

| Barnes et al60 | 2011 | 96 | I-II nonbulky HL | 83 | 94 | 46 | 4 | 94 | 54 |

| Spaepen et al61 | 2001 | 93 | Aggressive NHL | 50 | 100 | 70 | — | NS | NS |

| Micallef et al32* | 2011 | 69 | DLBCL | 61 | 90 | 50 | 2 | 78 | 50 |

| Pregno et al30 | 2012 | 88 | DLBCL | 77 | 100 | 82 | 2 | 83 | 64 |

| Trotman et al33 | 2011 | 122 | High–tumor burden FL | 90 | NS | NS | 3.5 | 71 | 33 |

| Dupuis et al34* | 2012 | 106 | High–tumor burden FL | 83 | NS | NS | 2 | 87 | 51 |

Abbreviations: CRu, unconfirmed complete response; CT, computed tomography; DLBCL, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; EFS, event-free survival; FL, follicular lymphoma; FTF, freedom from treatment failure; HL, Hodgkin lymphoma; NA, not applicable; NHL, non-Hodgkin lymphoma; NPV, negative predictive value; NS, not stated; PET, positron emission tomography; PFS, progression-free survival; PPV, positive predictive value; PR, partial response.

Prospective study.

Treatment guided by end-of-treatment PET.

Fig A1.

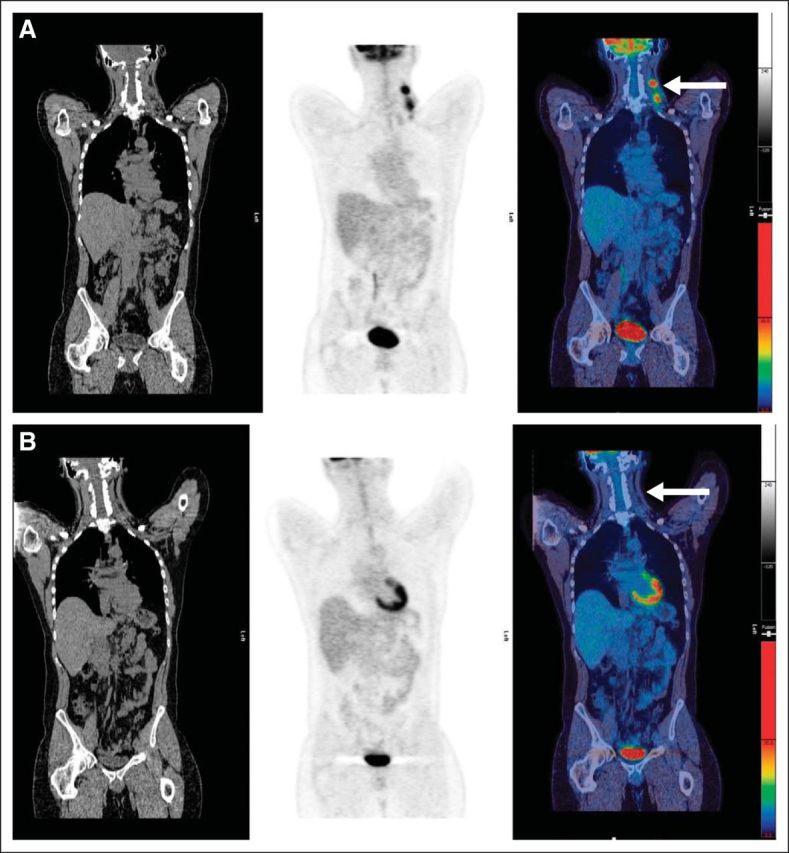

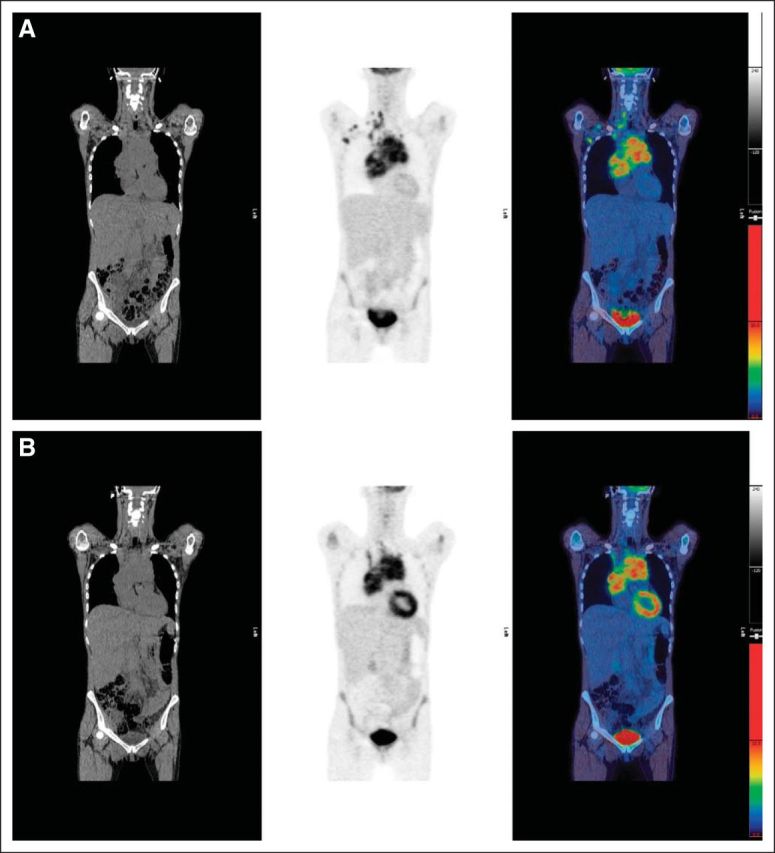

(A) Pretreatment scan: computed tomography, positron emission tomography, and fused images showing disease in left neck (arrow). (B) Example of score 1: complete metabolic response with no uptake in normal-size lymph nodes at site of initial disease in left neck (arrow).

Fig A2.

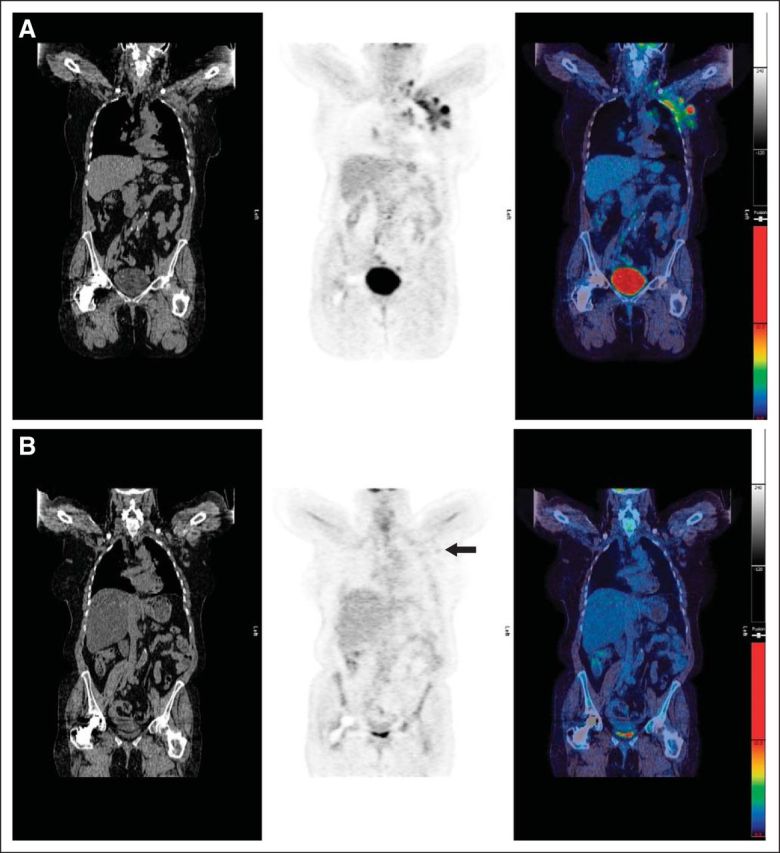

(A) Pretreatment scan: computed tomography, positron emission tomography, and fused images showing disease in left axilla. (B) Example of score 2: residual uptake of intensity < mediastinal blood pool in lymph nodes in left axilla (arrow). Maximum standardized uptake value (SUVmax) in lymph nodes was 1.2; SUVmax in mediastinal blood pool was 1.7.

Fig A3.

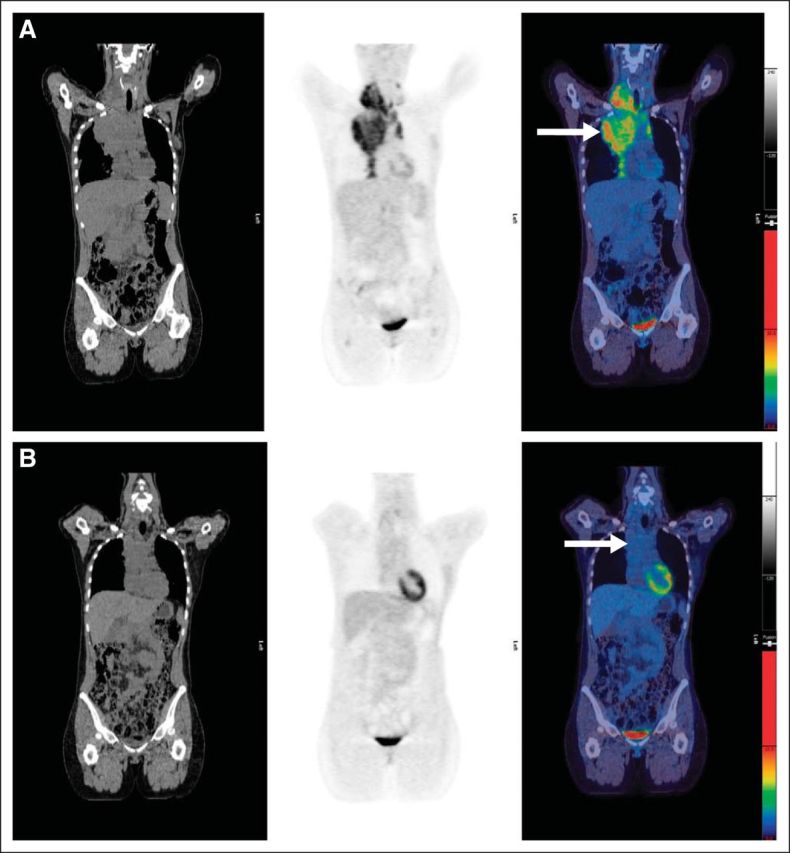

(A) Pretreatment scan: computed tomography, positron emission tomography, and fused images showing disease in right neck and mediastinum (arrow). (B) Example of score 3: residual uptake of intensity > mediastinal blood pool but < liver in residual mediastinal mass (arrow). Maximum standardized uptake value (SUVmax) in mass was 1.7; SUVmax in liver was 2.2.

Fig A4.

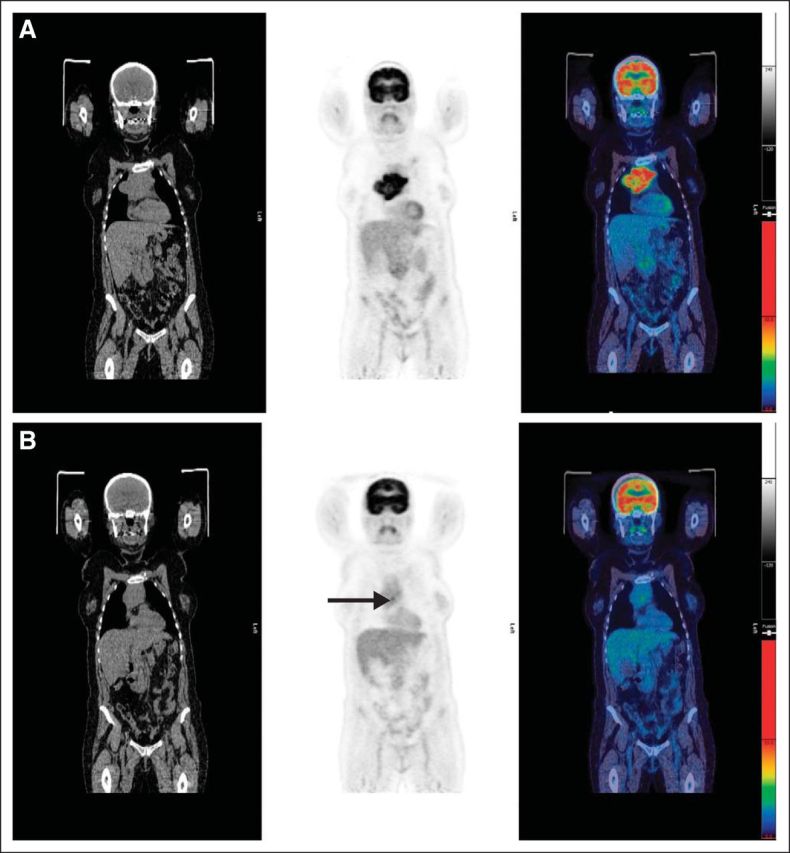

(A) Pretreatment scan: computed tomography, positron emission tomography, and fused images showing disease in mediastinum. (B) Example of score 4: residual uptake of intensity > liver in residual mediastinal mass (arrow). Maximum standardized uptake value (SUVmax) in mass was 4.5; SUVmax in liver was 3.2.

Fig A5.

(A) Pretreatment scan: computed tomography, positron emission tomography, and fused images showing disease in right neck, mediastinum, and right axilla. (B) Example of score 5: residual uptake in mediastinum with intensity markedly higher than normal liver. Maximum standardized uptake value (SUVmax) in mass was 13.0; SUVmax in liver was 2.3.

Footnotes

See accompanying article on page 3059

Processed as a Rapid Communications manuscript.

Authors' disclosures of potential conflicts of interest and author contributions are found at the end of this article.

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Although all authors completed the disclosure declaration, the following author(s) and/or an author's immediate family member(s) indicated a financial or other interest that is relevant to the subject matter under consideration in this article. Certain relationships marked with a “U” are those for which no compensation was received; those relationships marked with a “C” were compensated. For a detailed description of the disclosure categories, or for more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to the Author Disclosure Declaration and the Disclosures of Potential Conflicts of Interest section in Information for Contributors.

Employment or Leadership Position: None Consultant or Advisory Role: None Stock Ownership: None Honoraria: Lawrence H. Schwartz, Pfizer Research Funding: None Expert Testimony: None Patents, Royalties, and Licenses: None Other Remuneration: Lawrence H. Schwartz, Roche; Richard I. Fisher, Johnson & Johnson, Gilead Sciences, Coherus Bioscience

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Sally F. Barrington, N. George Mikhaeel, Lale Kostakoglu, Michel Meignan, Martin Hutchings, Stefan P. Müeller, Lawrence H. Schwartz, Emanuele Zucca, Richard I. Fisher, Rodney J. Hicks, Michael J. O'Doherty, Alberto Biggi, Bruce D. Cheson

Collection and assembly of data: Sally F. Barrington, N. George Mikhaeel, Lale Kostakoglu, Michel Meignan, Martin Hutchings, Stefan P. Müeller, Lawrence H. Schwartz

Data analysis and interpretation: Sally F. Barrington, N. George Mikhaeel, Lale Kostakoglu, Michel Meignan, Martin Hutchings, Stefan P. Müeller, Lawrence H. Schwartz, Judith Trotman, Otto S. Hoekstra, Roland Hustinx

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

REFERENCES

- 1.A predictive model for aggressive non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: The International Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma Prognostic Factors Project. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:987–994. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199309303291402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Solal-Céligny P, Roy P, Colombat P, et al. Follicular lymphoma international prognostic index. Blood. 2004;104:1258–1265. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-12-4434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hoster E, Dreyling M, Klapper W, et al. A new prognostic index (MIPI) for patients with advanced-stage mantle cell lymphoma. Blood. 2008;111:558–565. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-06-095331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Younes A. Early-stage Hodgkin's lymphoma: In pursuit of perfection. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:895–896. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.40.1661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rosenwald A, Wright G, Chan WC, et al. The use of molecular profiling to predict survival after chemotherapy for diffuse large-B-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1937–1947. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheson BD. Role of functional imaging in the management of lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:1844–1854. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.5225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Juweid ME, Stroobants S, Hoekstra OS, et al. Use of positron emission tomography for response assessment of lymphoma: Consensus of the Imaging Subcommittee of International Harmonization Project in Lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:571–578. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.2305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheson BD, Pfistner B, Juweid ME, et al. Revised response criteria for malignant lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:579–586. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.2403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hutchings M, Loft A, Hansen M, et al. Position emission tomography with or without computed tomography in the primary staging of Hodgkin's lymphoma. Haematologica. 2006;91:482–489. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rigacci L, Vitolo U, Nassi L, et al. Positron emission tomography in the staging of patients with Hodgkin's lymphoma: A prospective multicentric study by the Intergruppo Italiano Linfomi. Ann Hematol. 2007;86:897–903. doi: 10.1007/s00277-007-0356-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Raanani P, Shasha Y, Perry C, et al. Is CT scan still necessary for staging in Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma patients in the PET/CT era? Ann Oncol. 2006;17:117–122. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdj024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elstrom R, Leonard JP, Coleman M, et al. Combined PET and low-dose, noncontrast CT scanning obviates the need for additional diagnostic contrast-enhanced CT scans in patients undergoing staging or restaging for lymphoma. Ann Oncol. 2008;19:1770–1773. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pelosi E, Pregno P, Penna D, et al. Role of whole-body [18F] fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography (FDG-PET/CT) and conventional techniques in the staging of patients with Hodgkin and aggressive non Hodgkin lymphoma [in English, Italian] Radiol Med. 2008;113:578–590. doi: 10.1007/s11547-008-0264-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Karam M, Novak L, Cyriac J, et al. Role of fluorine-18 fluoro-deoxyglucose positron emission tomography scan in the evaluation and follow-up of patients with low-grade lymphomas. Cancer. 2006;107:175–183. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Janikova A, Bolcak K, Pavlik T, et al. Value of [18F]fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography in the management of follicular lymphoma: The end of a dilemma? Clin Lymphoma Myeloma. 2008;8:287–293. doi: 10.3816/CLM.2008.n.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wirth A, Foo M, Seymour JF, et al. Impact of [18f] fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography on staging and management of early-stage follicular non-hodgkin lymphoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;71:213–219. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.09.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Le Dortz L, De Guibert S, Bayat S, et al. Diagnostic and prognostic impact of 18F-FDG PET/CT in follicular lymphoma. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2010;37:2307–2314. doi: 10.1007/s00259-010-1539-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Luminari S, Biasoli I, Arcaini L, et al. The use of FDG-PET in the initial staging of 142 patients with follicular lymphoma: A retrospective study from the FOLL05 randomized trial of the Fondazione Italiana Linfomi. Ann Oncol. 2013;24:2108–2112. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hutchings M, Mikhaeel NG, Fields PA, et al. Prognostic value of interim FDG-PET after two or three cycles of chemotherapy in Hodgkin lymphoma. Ann Oncol. 2005;16:1160–1168. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdi200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hutchings M, Loft A, Hansen M, et al. FDG-PET after two cycles of chemotherapy predicts treatment failure and progression-free survival in Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood. 2006;107:52–59. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-06-2252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gallamini A, Rigacci L, Merli F, et al. The predictive value of positron emission tomography scanning performed after two courses of standard therapy on treatment outcome in advanced stage Hodgkin's disease. Haematologica. 2006;91:475–481. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gallamini A, Hutchings M, Rigacci L, et al. Early interim 2-[18F]fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose positron emission tomography is prognostically superior to international prognostic score in advanced-stage Hodgkin's lymphoma: A report from a joint Italian-Danish study. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:3746–3752. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.6525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cerci JJ, Pracchia LF, Linardi CC, et al. 18F-FDG PET after 2 cycles of ABVD predicts event-free survival in early and advanced Hodgkin lymphoma. J Nucl Med. 2010;51:1337–1343. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.109.073197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zinzani PL, Rigacci L, Stefoni V, et al. Early interim 18F-FDG PET in Hodgkin's lymphoma: Evaluation on 304 patients. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2012;39:4–12. doi: 10.1007/s00259-011-1916-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Biggi A, Gallamini A, Chauvie S, et al. International validation study for interim PET in ABVD-treated, advanced-stage Hodgkin lymphoma: Interpretation criteria and concordance rate among reviewers. J Nucl Med. 2013;54:683–690. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.112.110890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cerci JJ, Trindade E, Pracchia LF, et al. Cost effectiveness of positron emission tomography in patients with Hodgkin's lymphoma in unconfirmed complete remission or partial remission after first-line therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1415–1421. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.4367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Engert A, Haverkamp H, Kobe C, et al. Reduced-intensity chemotherapy and PET-guided radiotherapy in patients with advanced stage Hodgkin's lymphoma (HD15 trial): A randomised, open-label, phase 3 non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2012;379:1791–1799. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61940-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang DH, Min JJ, Song HC, et al. Prognostic significance of interim (18)F-FDG PET/CT after three or four cycles of R-CHOP chemotherapy in the treatment of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Eur J Cancer. 2011;47:1312–1318. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zinzani PL, Gandolfi L, Broccoli A, et al. Midtreatment 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron-emission tomography in aggressive non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Cancer. 2011;117:1010–1018. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pregno P, Chiappella A, Bello M, et al. Interim 18-FDG-PET/CT failed to predict the outcome in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma patients treated at the diagnosis with rituximab-CHOP. Blood. 2012;119:2066–2073. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-06-359943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Safar V, Dupuis J, Itti E, et al. Interim [18F]fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography scan in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated with anthracycline-based chemotherapy plus rituximab. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:184–190. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.2648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Micallef IN, Maurer MJ, Wiseman GA, et al. Epratuzumab with rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone chemotherapy in patients with previously untreated diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2011;118:4053–4061. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-02-336990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Trotman J, Fournier M, Lamy T, et al. Positron emission tomography–computed tomography (PET-CT) after induction therapy is highly predictive of patient outcome in follicular lymphoma: Analysis of PET-CT in a subset of PRIMA trial participants. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:3194–3200. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.35.0736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dupuis J, Berriolo-Riedinger A, Julian A, et al. Impact of [18F]fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography response evaluation in patients with high-tumor burden follicular lymphoma treated with immunochemotherapy: A prospective study from the Groupe d'Etudes des Lymphomes de l'Adulte and GOELAMS. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:4317–4322. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.43.0934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hutchings M, Barrington SF. PET/CT for therapy response assessment in lymphoma. J Nucl Med. 2009;50(suppl 1):21S–30S. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.108.057190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kostakoglu L, Gallamini A. Interim 18F-FDG PET in Hodgkin lymphoma: Would PET-adapted clinical trials lead to a paradigm shift? J Nucl Med. 2013;54:1082–1093. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.113.120451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shankar LK, Hoffman JM, Bacharach S, et al. Consensus recommendations for the use of F-18-FDG PET as an indicator of therapeutic response in patients in national cancer institute trials. J Nucl Med. 2006;47:1059–1066. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Scheuermann JS, Saffer JR, Karp JS, et al. Qualification of PET scanners for use in multicenter cancer clinical trials: The American College of Radiology Imaging Network experience. J Nucl Med. 2009;50:1187–1193. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.108.057455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Boellaard R, O'Doherty MJ, Weber WA, et al. FDG PET and PET/CT: EANM procedure guidelines for tumour PET imaging: Version 1.0. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2010;37:181–200. doi: 10.1007/s00259-009-1297-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Barrington SF, MacKewn JE, Schleyer P, et al. Establishment of a UK-wide network to facilitate the acquisition of quality assured FDG-PET data for clinical trials in lymphoma. Ann Oncol. 2011;22:739–745. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Boellaard R, Oyen WJ, Hoekstra CJ, et al. The Netherlands protocol for standardisation and quantification of FDG whole body PET studies in multi-centre trials. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2008;35:2320–2333. doi: 10.1007/s00259-008-0874-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Barrington SF, Qian W, Somer EJ, et al. Concordance between four European centres of PET reporting criteria designed for use in multicentre trials in Hodgkin lymphoma. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2010;37:1824–1833. doi: 10.1007/s00259-010-1490-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Meignan M, Gallamini A, Haioun C. Report on the First International Workshop on Interim-PET-Scan in Lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma. 2009;50:1257–1260. doi: 10.1080/10428190903040048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Radford J, Barrington S, Counsell N, et al. Involved field radiotherapy versus no further treatment in patients with clinical stages IA and IIA Hodgkin lymphoma and a “negative” PET scan after 3 cycles ABVD: Results of the UK NCRI RAPID trial. Blood. 2012:120. (abstr 547) [Google Scholar]

- 45.Johnson P, Federico M, Fossa A, et al. Responses and chemotherapy dose adjustment determined by PET-CT imaging: First results from the International Response Adapted Therapy in Advanced Hodgkin Lymphoma (RATHL) study. Hematol Oncol. 2013;31:96–150. (abstr 126) [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gallamini A, Rossi A, Patti C, et al. Early treatment intensification in advanced-stage high-risk Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) patients with a positive FDG-PET scan after two ABVD courses: First interim analysis of the GITIL/FIL HD0607 clinical trial. Blood. 2012:120. (abstr 550) [Google Scholar]

- 47.Southwest Oncology Group. Fluorodeoxyglucose F 18-PET/CT imaging and combination chemotherapy with or without additional chemotherapy and G-CSF in treating patients with stage III or stage IV Hodgkin lymphoma: 02/12 update. http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00822120.

- 48.International Extranodal Lymphoma Study Group (IELSG) A randomized, open-label two-arm phase III comparative study assessing the role of involved mediastinal radiotherapy after rituximab containing chemotherapy regimens to patients with newly diagnosed primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma: 03/2013. http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01599559.

- 49.Millennium Pharmaceuticals. A randomized, open-label, phase 3 trial of A + AVD versus ABVD as frontline therapy in patients with advanced classical Hodgkin lymphoma: 08/13 update. http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01712490.

- 50.Dührsen U, Hüttmann A, Jöckel KH, et al. Positron emission tomography guided therapy of aggressive non-Hodgkin lymphomas: The PETAL trial. Leuk Lymphoma. 2009;50:1757–1760. doi: 10.3109/10428190903308031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Young H, Baum R, Cremerius U, et al. Measurement of clinical and subclinical tumour response using [18F]-fluorodeoxyglucose and positron emission tomography: Review and 1999 EORTC recommendations—European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) PET Study Group. Eur J Cancer. 1999;35:1773–1782. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(99)00229-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bourguet P, Blanc-Vincent MP, Boneu A, et al. Summary of the standards, options and recommendations for the use of positron emission tomography with 2-[18F]fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose (FDG-PET scanning) in oncology. Br J Cancer. 2003;89(suppl 1):S84–S91. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Coleman RE, Delbeke D, Guiberteau MJ, et al. Concurrent PET/CT with an integrated imaging system: Intersociety dialogue from the joint working group of the American College of Radiology, the Society of Nuclear Medicine, and the Society of Computed Body Tomography and Magnetic Resonance. J Nucl Med. 2005;46:1225–1239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Boellaard R. Standards for PET image acquisition and quantitative data analysis. J Nucl Med. 2009;50(suppl 1):11S–20S. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.108.057182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Haioun C, Itti E, Rahmouni A, et al. F-18 fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) in aggressive lymphoma: An early prognostic tool for predicting patient outcome. Blood. 2005;106:1376–1381. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-01-0272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Markova J, Kobe C, Skopalova M, et al. FDG-PET for assessment of early treatment response after four cycles of chemotherapy in patients with advanced-stage Hodgkin's lymphoma has a high negative predictive value. Ann Oncol. 2009;20:1270–1274. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mikhaeel NG, Hutchings M, Fields PA, et al. FDG-PET after two to three cycles of chemotherapy predicts progression-free and overall survival in high-grade non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Ann Oncol. 2005;16:1514–1523. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdi272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nols N, Mounier N, Bouazza S, et al. Quantitative and qualitative analysis of metabolic response at interim PET-scan combined with IPI is highly predictive of outcome in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma. 2014;55:773–780. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2013.831848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Spaepen K, Stroobants S, Dupont P, et al. Early restaging positron emission tomography with (18)F-fluorodeoxyglucose predicts outcome in patients with aggressive non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Ann Oncol. 2002;13:1356–1363. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdf256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Barnes JA, LaCasce AS, Zukotynski K, et al. End-of-treatment but not interim PET scan predicts outcome in nonbulky limited-stage Hodgkin's lymphoma. Ann Oncol. 2011;22:910–915. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Spaepen K, Stroobants S, Dupont P, et al. Prognostic value of positron emission tomography (PET) with fluorine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose ([18F]FDG) after first-line chemotherapy in non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: Is [18F]FDG-PET a valid alternative to conventional diagnostic methods? J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:414–419. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.2.414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Elstrom R, Guan L, Baker G, et al. Utility of FDG-PET scanning in lymphoma by WHO classification. Blood. 2003;101:3875–3876. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-09-2778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tsukamoto N, Kojima M, Hasegawa M, et al. The usefulness of (18)F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography ((18)F-FDG-PET) and a comparison of (18)F-FDG-pet with (67)gallium scintigraphy in the evaluation of lymphoma: Relation to histologic subtypes based on the World Health Organization classification. Cancer. 2007;110:652–659. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Weiler-Sagie M, Bushelev O, Epelbaum R, et al. (18)F-FDG avidity in lymphoma readdressed: A study of 766 patients. J Nucl Med. 2010;51:25–30. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.109.067892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bodet-Milin C, Touzeau C, Leux C, et al. Prognostic impact of 18F-fluoro-deoxyglucose positron emission tomography in untreated mantle cell lymphoma: A retrospective study from the GOELAMS group. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2010;37:1633–1642. doi: 10.1007/s00259-010-1469-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Feeney J, Horwitz S, Gönen M, et al. Characterization of T-cell lymphomas by FDG PET/CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2010;195:333–340. doi: 10.2214/AJR.09.3665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cahu X, Bodet-Milin C, Brissot E, et al. 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography before, during and after treatment in mature T/NK lymphomas: A study from the GOELAMS group. Ann Oncol. 2011;22:705–711. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Barrington SF, O'Doherty MJ. Limitations of PET for imaging lymphoma. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2003;30(suppl 1):S117–S127. doi: 10.1007/s00259-003-1169-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cook GJ, Wegner EA, Fogelman I. Pitfalls and artifacts in 18FDG PET and PET/CT oncologic imaging. Semin Nucl Med. 2004;34:122–133. doi: 10.1053/j.semnuclmed.2003.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.El-Galaly TC, d'Amore F, Mylam KJ, et al. Routine bone marrow biopsy has little or no therapeutic consequence for positron emission tomography/computed tomography–staged treatment-naive patients with Hodgkin lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:4508–4514. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.42.4036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Moulin-Romsee G, Hindié E, Cuenca X, et al. (18)F-FDG PET/CT bone/bone marrow findings in Hodgkin's lymphoma may circumvent the use of bone marrow trephine biopsy at diagnosis staging. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2010;37:1095–1105. doi: 10.1007/s00259-009-1377-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Richardson SE, Sudak J, Warbey V, et al. Routine bone marrow biopsy is not necessary in the staging of patients with classical Hodgkin lymphoma in the 18F-fluoro-2-deoxyglucose positron emission tomography era. Leuk Lymphoma. 2012;53:381–385. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2011.616613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Schaefer NG, Strobel K, Taverna C, et al. Bone involvement in patients with lymphoma: The role of FDG-PET/CT. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2007;34:60–67. doi: 10.1007/s00259-006-0238-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Berthet L, Cochet A, Kanoun S, et al. In newly diagnosed diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, determination of bone marrow involvement with 18F-FDG PET/CT provides better diagnostic performance and prognostic stratification than does biopsy. J Nucl Med. 2013;54:1244–1250. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.112.114710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Mittal BR, Manohar K, Malhotra P, et al. Can fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography avoid negative iliac crest biopsies in evaluation of marrow involvement by lymphoma at time of initial staging? Leuk Lymphoma. 2011;52:2111–2116. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2011.593273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ngeow JY, Quek RH, Ng DC, et al. High SUV uptake on FDG-PET/CT predicts for an aggressive B-cell lymphoma in a prospective study of primary FDG-PET/CT staging in lymphoma. Ann Oncol. 2009;20:1543–1547. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Pelosi E, Penna D, Douroukas A, et al. Bone marrow disease detection with FDG-PET/CT and bone marrow biopsy during the staging of malignant lymphoma: Results from a large multicentre study. Q J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2011;55:469–475. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Cheson BD. Hodgkin lymphoma: Protecting the victims of our success. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:4456–4457. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.45.5402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Khan AB, Barrington SF, Mikhaeel NG, et al. PET-CT staging of DLBCL accurately identifies and provides new insight into the clinical significance of bone marrow involvement. Blood. 2013;122:61–67. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-12-473389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Carr R, Barrington SF, Madan B, et al. Detection of lymphoma in bone marrow by whole-body positron emission tomography. Blood. 1998;91:3340–3346. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Paone G, Itti E, Haioun C, et al. Bone marrow involvement in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: Correlation between FDG-PET uptake and type of cellular infiltrate. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2009;36:745–750. doi: 10.1007/s00259-008-1021-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Chen YK, Yeh CL, Tsui CC, et al. F-18 FDG PET for evaluation of bone marrow involvement in non-Hodgkin lymphoma: A meta-analysis. Clin Nucl Med. 2011;36:553–559. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0b013e318217aeff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.O'Doherty MJ, Barrington SF, Campbell M, et al. PET scanning and the human immunodeficiency virus-positive patient. J Nucl Med. 1997;38:1575–1583. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Barrington SF, Mikhaeel NG. When should FDG-PET be used in the modern management of lymphoma? Br J Haematol. 2014;164:315–328. doi: 10.1111/bjh.12601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lin C, Itti E, Haioun C, et al. Early 18F-FDG PET for prediction of prognosis in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: SUV-based assessment versus visual analysis. J Nucl Med. 2007;48:1626–1632. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.107.042093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Itti E, Lin C, Dupuis J, et al. Prognostic value of interim 18F-FDG PET in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: SUV-based assessment at 4 cycles of chemotherapy. J Nucl Med. 2009;50:527–533. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.108.057703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Quarles van Ufford H, Hoekstra O, de Haas M, et al. On the added value of baseline FDG-PET in malignant lymphoma. Mol Imaging Biol. 2010;12:225–232. doi: 10.1007/s11307-009-0259-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Meignan M, Itti E, Bardet S, et al. Development and application of a real-time on-line blinded independent central review of interim PET scans to determine treatment allocation in lymphoma trials. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2739–2741. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.4089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Mikhaeel NG, Timothy AR, O'Doherty MJ, et al. 18-FDG-PET as a prognostic indicator in the treatment of aggressive Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma-comparison with CT. Leuk Lymphoma. 2000;39:543–553. doi: 10.3109/10428190009113384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Mikhaeel NG. Interim fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography for early response assessment in diffuse large B cell lymphoma: Where are we now? Leuk Lymphoma. 2009;50:1931–1936. doi: 10.3109/10428190903275610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Fuertes S, Setoain X, Lopez-Guillermo A, et al. Interim FDG PET/CT as a prognostic factor in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2013;40:496–504. doi: 10.1007/s00259-012-2320-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Le Roux PY, Gastinne T, Le Gouill S, et al. Prognostic value of interim FDG PET/CT in Hodgkin's lymphoma patients treated with interim response-adapted strategy: Comparison of International Harmonization Project (IHP), Gallamini and London criteria. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2011;38:1064–1071. doi: 10.1007/s00259-011-1741-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Itti E, Meignan M, Berriolo-Riedinger A, et al. An international confirmatory study of the prognostic value of early PET/CT in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: Comparison between Deauville criteria and δSUVmax. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2013;40:1312–1320. doi: 10.1007/s00259-013-2435-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Martelli M, Ceriani L, Zucca E, et al. [18F]Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography predicts survival after chemoimmunotherapy for primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma: Results of the International Extranodal Lymphoma Study Group IELSG-26 Study. J Clin Oncol. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.51.7524. [epub ahead of print on May 5, 2014] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Fondazione Italiana Linfomi. A multicenter, phase III, randomized study to evaluate the efficacy of a response-adapted strategy to define maintenance after standard chemoimmunotherapy in patients with advanced-stage follicular lymphoma: FIL FOLL12—Update 07/13. https://www.clinicaltrialsregister.eu/ctr-search/search?query=eudract_number:2012-003170-60.

- 96.Spectrum Pharmaceuticals. Study of zevalin versus observation in patients at least 60 yrs old with newly diagnosed diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in PET-negative complete remission after R-CHOP or R-CHOP-like therapy: 11/13 update. http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01510184.

- 97.Lymphoma Academic Research Organisation. Study evaluating the non-inferiority of a treatment adapted to the early response evaluated with 18F-FDG PET compared to a standard treatment, for patients aged from 18 to 80 years with low risk (aa IPI = 0) diffuse large B-cells non Hodgkin's lymphoma CD 20+: Update 10/13. http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01285765.

- 98.Furth C, Amthauer H, Hautzel H, et al. Evaluation of interim PET response criteria in paediatric Hodgkin's lymphoma-results for dedicated assessment criteria in a blinded dual-centre read. Ann Oncol. 2011;22:1198–1203. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Mamot C, Klingbiel D, Renner C, et al. Final results of a prospective evaluation of the predictive value of interim PET in patients with DLBCL under R-CHOP-14 (SAKK 38/07) Hematol Oncol. 2013;31(suppl 1):100–101. abst 15. [Google Scholar]

- 100.Itti E, M M, Berriolo-Riedinger A, Biggi A, et al. An international validation study of the prognostic role of interim FDG PET/CT in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2013;40:1312–1320. doi: 10.1007/s00259-013-2435-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.de Langen AJ, Vincent A, Velasquez LM, et al. Repeatability of 18F-FDG uptake measurements in tumors: A metaanalysis. J Nucl Med. 2012;53:701–708. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.111.095299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Wahl RL, Jacene H, Kasamon Y, et al. From RECIST to PERCIST: Evolving considerations for PET response criteria in solid tumors. J Nucl Med. 2009;50(suppl 1):122S–150S. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.108.057307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Roy FN, Beaulieu S, Boucher L, et al. Impact of intravenous insulin on 18F-FDG PET in diabetic cancer patients. J Nucl Med. 2009;50:178–183. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.108.056283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Lister TA, Crowther D, Sutcliffe SB, et al. Report of a committee convened to discuss the evaluation and staging of patients with Hodgkin's disease: Cotswolds meeting. J Clin Oncol. 1989;7:1630–1636. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1989.7.11.1630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Hasenclever D, Diehl V. A prognostic score for advanced Hodgkin's disease: International Prognostic Factors Project on advanced Hodgkin's disease. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:1506–1514. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199811193392104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Bangerter M, Moog F, Buchmann I, et al. Whole-body 2-[18F]-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) for accurate staging of Hodgkin's disease. Ann Oncol. 1998;9:1117–1122. doi: 10.1023/a:1008486928190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Partridge S, Timothy A, O'Doherty MJ, et al. 2-Fluorine-18-fluoro-2-deoxy-D glucose positron emission tomography in the pretreatment staging of Hodgkin's disease: Influence on patient management in a single institution. Ann Oncol. 2000;11:1273–1279. doi: 10.1023/a:1008368330519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Jerusalem G, Beguin Y, Fassotte MF, et al. Whole-body positron emission tomography using 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose compared to standard procedures for staging patients with Hodgkin's disease. Haematologica. 2001;86:266–273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Weihrauch MR, Re D, Bischoff S, et al. Whole-body positron emission tomography using 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose for initial staging of patients with Hodgkin's disease. Ann Hematol. 2002;81:20–25. doi: 10.1007/s00277-001-0390-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Munker R, Glass J, Griffeth LK, et al. Contribution of PET imaging to the initial staging and prognosis of patients with Hodgkin's disease. Ann Oncol. 2004;15:1699–1704. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdh426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Naumann R, Beuthien-Baumann B, Reiss A, et al. Substantial impact of FDG PET imaging on the therapy decision in patients with early-stage Hodgkin's lymphoma. Br J Cancer. 2004;90:620–625. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Buchmann I, Reinhardt M, Elsner K, et al. 2-(fluorine-18)fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose positron emission tomography in the detection and staging of malignant lymphoma: A bicenter trial. Cancer. 2001;91:889–899. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Wirth A, Seymour JF, Hicks RJ, et al. Fluorine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography, gallium-67 scintigraphy, and conventional staging for Hodgkin's disease and non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Am J Med. 2002;112:262–268. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(01)01117-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Schöder H, Noy A, Gönen M, et al. Intensity of [18F]fluorodeoxyglucose uptake in positron emission tomography distinguishes between indolent and aggressive non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:4643–4651. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.12.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Watanabe R, Tomita N, Takeuchi K, et al. SUVmax in FDG-PET at the biopsy site correlates with the proliferation potential of tumor cells in non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma. 2010;51:279–283. doi: 10.3109/10428190903440953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Schaefer NG, Hany TF, Taverna C, et al. Non-Hodgkin lymphoma and Hodgkin disease: Coregistered FDG PET and CT at staging and restaging—Do we need contrast-enhanced CT? Radiology. 2004;232:823–829. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2323030985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Gollub MJ, Hong R, Sarasohn DM, et al. Limitations of CT during PET/CT. J Nucl Med. 2007;48:1583–1591. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.107.043109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Pinilla I, Gómez-León N, Del Campo-Del Val L, et al. Diagnostic value of CT, PET and combined PET/CT performed with low-dose unenhanced CT and full-dose enhanced CT in the initial staging of lymphoma. Q J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2011;55:567–575. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Chalaye J, Luciani A, Enache C, et al. Clinical impact of contrast-enhanced computed tomography combined with low-dose 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography on routine lymphoma patient management. Leuk Lymphoma. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2014.900761. [epub ahead of print on April 3, 2014] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Hoskin PJ, Díez P, Williams M, et al. Recommendations for the use of radiotherapy in nodal lymphoma. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2013;25:49–58. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2012.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Vriens D, Visser EP, de Geus-Oei LF, et al. Methodological considerations in quantification of oncological FDG PET studies. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2010;37:1408–1425. doi: 10.1007/s00259-009-1306-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Berthelsen AK, Holm S, Loft A, et al. PET/CT with intravenous contrast can be used for PET attenuation correction in cancer patients. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2005;32:1167–1175. doi: 10.1007/s00259-005-1784-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Eichenauer DA, Engert A, Dreyling M. Hodgkin's lymphoma: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2011;22(suppl 6):vi55–vi58. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdr378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Pfreundschuh M, Kuhnt E, Trümper L, et al. CHOP-like chemotherapy with or without rituximab in young patients with good-prognosis diffuse large-B-cell lymphoma: 6-year results of an open-label randomised study of the MabThera International Trial (MInT) Group. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:1013–1022. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70235-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Miller TP. The limits of limited stage lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:2982–2984. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.05.926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Coiffier B, Lepage E, Briere J, et al. CHOP chemotherapy plus rituximab compared with CHOP alone in elderly patients with diffuse large-B-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:235–242. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Federico M, Bellei M, Marcheselli L, et al. Follicular Lymphoma International Prognostic Index 2: A new prognostic index for follicular lymphoma developed by the International Follicular Lymphoma Prognostic Factor Project. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:4555–4562. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.3991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Yan J, Zhao B, Wang L, et al. Marker-controlled watershed for lymphoma segmentation in sequential CT images. Med Phys. 2006;33:2452–2460. doi: 10.1118/1.2207133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Yan J, Zhuang TG, Zhao B, et al. Lymph node segmentation from CT images using fast marching method. Comput Med Imaging Graph. 2004;28:33–38. doi: 10.1016/j.compmedimag.2003.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Manohar K, Mittal BR, Bhattacharya A, et al. Prognostic value of quantitative parameters derived on initial staging 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography in patients with high-grade non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Nucl Med Commun. 2012;33:974–981. doi: 10.1097/MNM.0b013e32835673ec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Kim TM, Paeng JC, Chun IK, et al. Total lesion glycolysis in positron emission tomography is a better predictor of outcome than the International Prognostic Index for patients with diffuse large B cell lymphoma. Cancer. 2013;119:1195–1202. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Kostakoglu L, Goldsmith SJ, Leonard JP, et al. FDG-PET after 1 cycle of therapy predicts outcome in diffuse large cell lymphoma and classic Hodgkin disease. Cancer. 2006;107:2678–2687. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]