EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Cancer care in the United States remained a mixed picture in 2015. Declining mortality rates, growing numbers of survivors, and exciting progress in treatment were set against the backdrop of increasingly unsustainable costs and a volatile practice environment. In this third annual State of Cancer Care in America report, the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) describes both challenges and opportunities facing the US cancer care system.

Balancing Progress and Challenges

In 2015, the US cancer care system developed new, more sophisticated therapies, expanded screening capabilities, and improved mortality for many types of cancer. However, there remains much room for improvement.

Progress in cancer care. This year, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) added 15 new drugs and biologic therapies to its list of more than 180 approved anticancer agents and expanded use for 12 previously approved treatments.1 2015 also marked introduction into the US market of the first product deemed biosimilar to an existing biologic product, paving the way for nonbrand products in the biologic drug sphere. Precision medicine was highlighted by President Obama as an important strategy for improving patient outcomes, and immunotherapy gained momentum within the cancer community. Thanks to these and other developments, patients with cancer face better treatment prospects than ever before.

Growing demand, stubborn mortality, and persistent inequities. An estimated 589,430 Americans died as a result of cancer in 2015.2 Mortality rates for some cancers, such as bladder cancer, brain cancer, and melanoma, have remained steady over the past decade, and pancreatic and liver cancer mortality rates have increased.3 Cancer incidence and mortality rates continue to vary substantially by race and ethnicity. For the first time in 2015, breast cancer incidence rates were higher for African American women than for any other racial group—a troubling development, because African American women with breast cancer are diagnosed at a younger age and have higher mortality rates than other women.4 These trends serve as a reminder that more effort is needed to improve outcomes for all patients with cancer.

Increasing complexity of care. This year’s report focuses on three areas that affect the complexity of cancer and its treatment: (1) cancer screening, (2) implementing precision medicine treatments, and (3) the aging of the US population. Screening programs have been successful in reducing morbidity and mortality in certain types of cancer, such as breast, colorectal, and cervical cancers. For many other cancers, the risk–benefit considerations are not so straightforward. The complexity involved in implementing cancer screening is based on the need to avoid over- and underscreening, as well as to make appropriate screening decisions when the evidence is ambiguous as to the potential health benefits for the patient. Precision medicine offers notable advantages to patients in need of expanded treatment options. However, physicians and patients are struggling to manage overwhelming amounts of information about risks and benefits of genetic testing—and its role in selecting treatment. Finally, an aging population means there will be an increasing number of patients whose cancer will be complicated by other chronic diseases.

Continued commitment to research funding and innovation needed. Advances in the scientific understanding and treatment of cancer have led to improved patient outcomes and quality of life. However, federal investment in research has not kept pace with this increasingly complex disease. Additionally, health information technology infrastructure must evolve to support innovative research designs, such as those using big data to gain rapid insight into patient outcomes and experiences.

Cancer Care Access and Affordability: Ensuring All Patients Can Receive Current and Developing Therapies

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) has expanded access to health insurance for millions of Americans, but many remain un- or underinsured. However, the cost of drugs, uneven implementation of the law, and other access barriers have placed care out of reach for many.

Insurance coverage. The ACA has extended insurance coverage to millions of Americans, and evidence suggests that this coverage is improving access to affordable care and having a positive impact on health.5,6

Variations in enrollment and coverage. Although the ACA has increased millions of people’s access to health insurance, approximately 35 million nonelderly adults remained uninsured in 2015.7 An additional 31 million individuals are underinsured because their deductible and/or out-of-pocket costs are high relative to their household income.8 Coverage across insurers and plans also remains inconsistent.

Rising drug prices and increasing burden for patients. Although the rate of growth in cost slowed temporarily during the recent economic downturn, health care spending has once again picked up speed—and costs associated with cancer care are rising more rapidly than costs in other medical sectors.9,10 For patients with cancer, two issues of critical importance are: (1) cost of cancer drugs and (2) increased patient burden associated with rising deductibles and cost shifting. A recent survey found that 24% of Americans say they have a hard time paying for prescription drugs, and 72% view the prices of prescription drugs as unreasonable.11

Oncology Practice and Workforce Trends: Engines for Discovery and Care Delivery Are at Risk

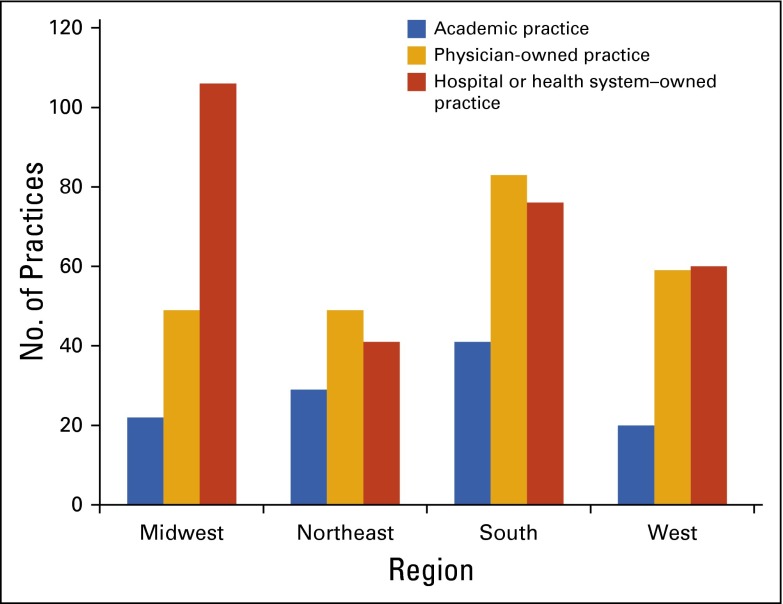

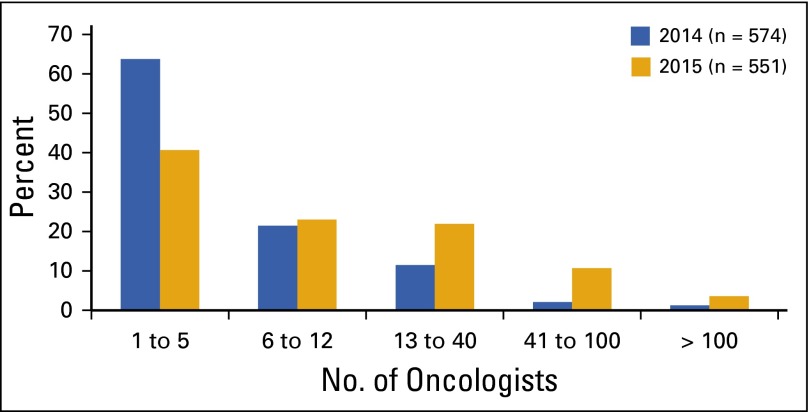

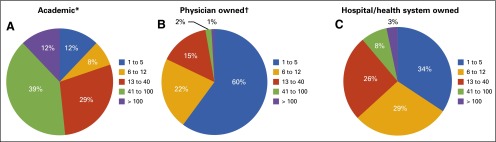

The 2016 ASCO Census and ASCO Practice Trends surveys suggest no abatement of volatility in the oncology practice environment. Economic pressures, market dynamics, and shifts in payment policy have combined to place many independent community practices in jeopardy. These trends and an increasingly constrained workforce raise concerns about how the US cancer care system will be able to respond to the projected surge in demand for cancer care in the coming years.

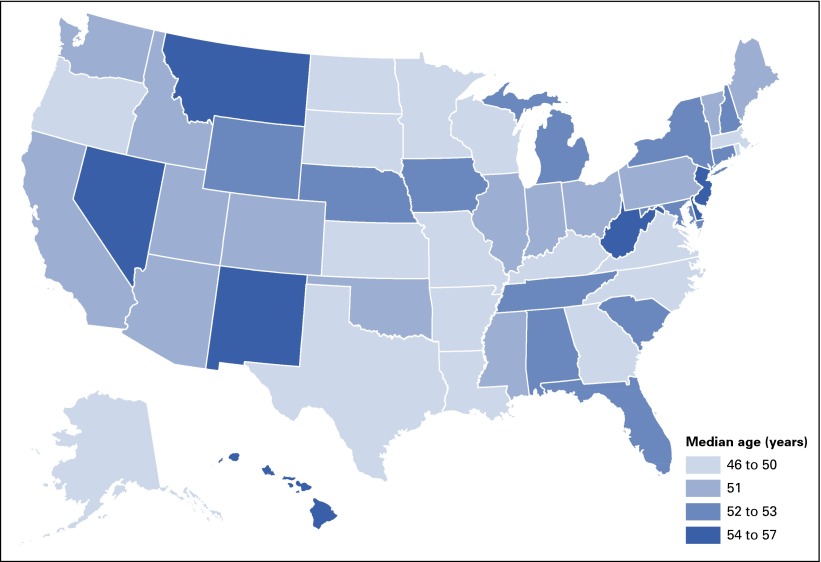

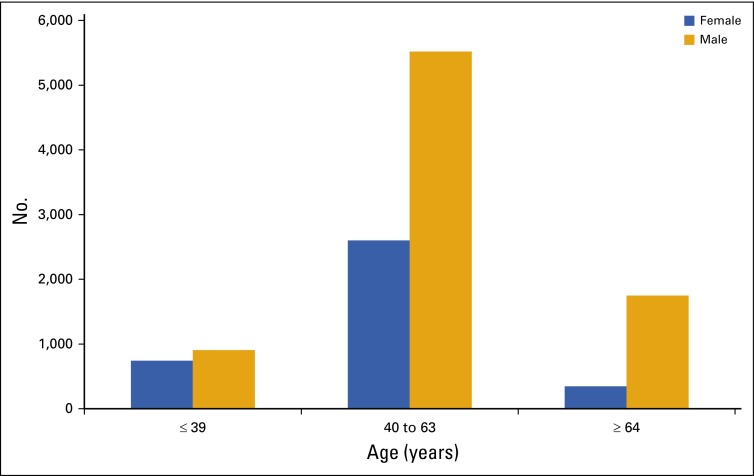

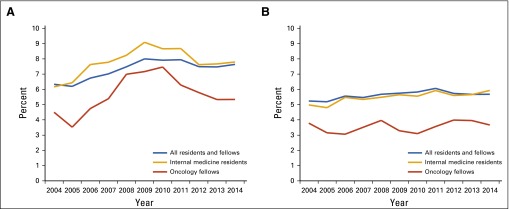

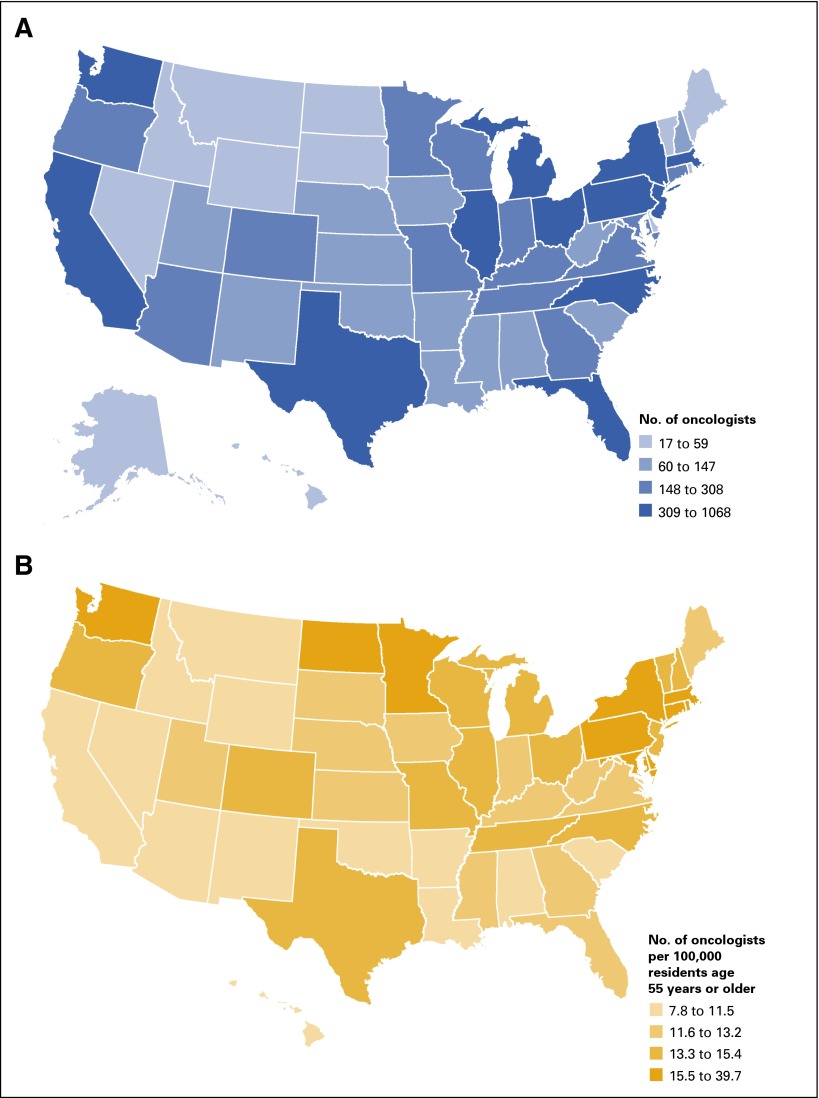

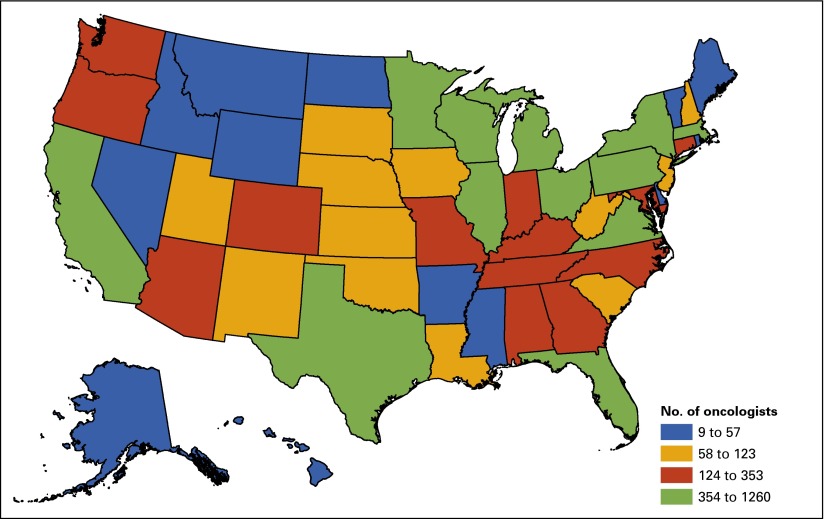

Oncologist workforce remains stable despite growth in demand. The size of the overall oncology workforce has remained relatively stable, with more than 11,700 hematologists and/or medical oncologists providing cancer care in the United States. However, specialists continue to age and largely practice in metropolitan areas, trends that could adversely affect the ability to meet demand for cancer services across the country.

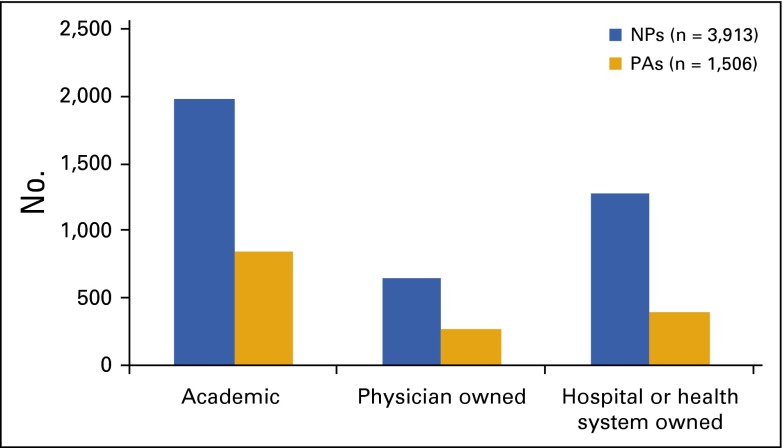

The cancer care team. Increasing emphasis on use of the medical home model for delivery of care is driving greater emphasis on team-based care by health providers from a variety of backgrounds and specialties, including—but not limited to—primary care physicians, urologists, gynecologists, pathologists, pharmacists, genetic counselors, mental health specialists, pain and palliative care specialists, and advanced practice providers.

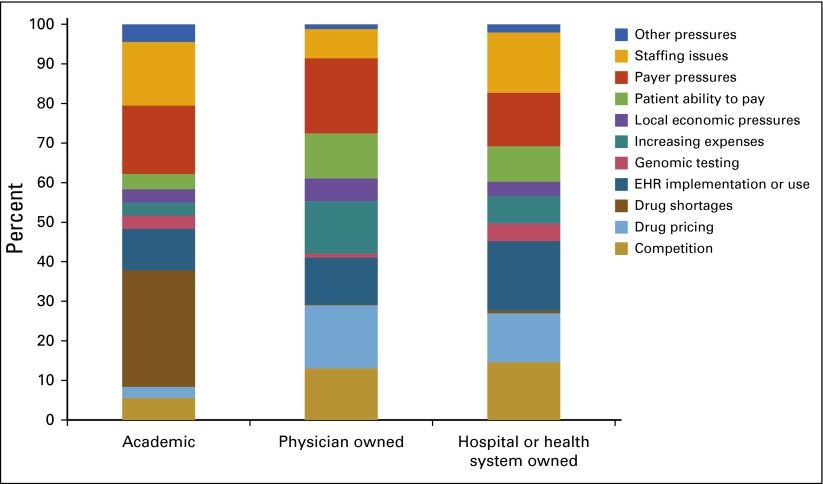

Census and Practice Trends surveys. ASCO surveyed a representative sample of academic, physician-owned, and hospital or health system–owned census respondents to gain further insight into high-priority and emerging topics of concern, including practice pressures, alternative payment models, clinical pathways, electronic health records (EHRs), and cost of care.

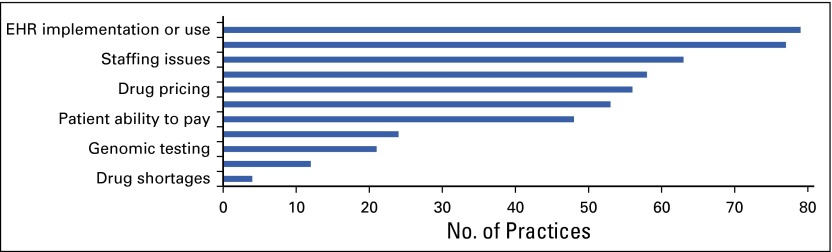

EHR implementation a top practice pressure. Nearly half (45%) of ASCO Practice Trends survey respondents cited EHR implementation or use as a priority practice pressure, surpassing all other pressures in 2015.

New Strategies for Delivering High-Quality, High-Value Cancer Care

As pressures to control costs escalate, payers and other stakeholders are pursuing new payment and care delivery models that lower spending while preserving quality. This report provides an overview of initiatives proposed and ongoing in 2015 to help relieve these pressures, namely in the areas of payment reform, value optimization, and performance improvement.

Payment reform; increased financial flexibility, high-quality care expected. A historic development for the US health care system was the April 2015 decision by the US Congress to repeal the sustainable growth rate (SGR) formula. The decision, part of the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 (MACRA), effectively reversed required payment cuts and replaced the SGR with a plan to return stability to the reimbursement of physician services by the Medicare program. MACRA also encourages physicians to participate in new payment models that provide more flexible options for reimbursing physician services in exchange for increased accountability in delivering high-quality care.

New payment and care models under evaluation. A number of alternative payment models have been developed to improve care and reduce costs. These models move away from fee-for-service payments to other payment approaches that increase accountability for both quality and total cost of care and that emphasize population health management, as opposed to payment for specific services. This report highlights specific alternative payment models being explored or currently in development for cancer care, including the new Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) Oncology Care Model (OCM), the ASCO Patient-Centered Oncology Payment (PCOP) model, and many efforts undertaken by private and public institutions. It also explores the implications of clinical pathway use in oncology practices.

Initiatives targeting high-value cancer care. The topic of health care costs is being incorporated into many medical education programs in the United States. In addition, many organizations, practices, and researchers are launching initiatives intended to address rising health care costs by making the value of various treatment choices more transparent to patients and their clinicians.

Strategies to measure and improve performance in cancer care. As payment systems shift incentives from volume to value, quality-monitoring programs are increasingly important mechanisms to protect from over- or underuse and to distinguish performance among practices and providers. New emphasis on performance measurement and reporting ushered in with MACRA also put new pressure on EHRs and other health information technologies to support compliance.

Conclusions and Recommendations

In 2016, the collective wisdom of stakeholders throughout the oncology community will be needed to overcome challenges and ensure every patient with cancer receives high-value, high-quality care. ASCO recommends prioritizing the following as means of addressing the challenges described in this report:

Ensure all publicly funded insurance programs offer consistent and appropriate benefits and services for patients with cancer.

Congress should mandate that private and public health insurance plans provide parity in benefits and coverage for intravenous cancer drugs and orally administered or self-injectable cancer drugs.

Congress should address ongoing disparities in Medicaid by modifying Medicaid coverage requirements to include coverage of clinical trials and removing disparities in benefits between Medicaid programs established before and after the ACA.

Professional organizations should remain engaged with their members to track ACA implementation effects and trends and work with policymakers to address issues preventing access to high-quality, high-value care for patients with cancer.

Test multiple innovative payment and care delivery models to identify feasible solutions that promote high-quality, high-value cancer care.

Professional organizations should develop innovative care models that can be tested by the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation (CMMI) and private payers as they seek better ways to incentivize and support high-quality, high-value patient care.

Congress should aggressively monitor implementation of MACRA to ensure (1) that the Administration works with professional organizations to test multiple payment models of care and (2) the Administration provides a clear path for implementation of payment models shown to provide positive results for patients, providers, and payers.

Advance health information technology that supports efficient, coordinated care across the cancer care continuum.

Congress should require that health information technology vendors create products that promote interoperability.

Policymakers should ensure that patients with cancer, oncologists, and other oncology providers do not bear the cost of achieving interoperable EHRs and that companies refrain from information blocking.

Professional organizations and other stakeholders should work with federal officials to ensure that health care providers have the information necessary to be prudent purchasers and users of health information technology systems.

Recognize and address the unsustainable trend in the cost of cancer care.

Congress should work with stakeholders to pursue solutions that will curb unsustainable costs for patients, providers, and the health care system.

Payers should design payment systems that incentivize patient-centered, high-value care and invest in infrastructure that supports a viable care delivery system.

Professional organizations should develop and disseminate clinical guidelines, tools, and resources such as Choosing Wisely to optimize patient care, reduce waste, and avoid inappropriate treatment.

Professional organizations should promote shared decision making between patients and physicians and the development of high-value treatment plans consistent with patients’ needs, values, and preferences.

ASCO will continue to: (1) track and evaluate the ever-shifting landscape in cancer care over the coming year, (2) support cancer care providers as they negotiate these growing pressures, and (3) work with policymakers to ensure that changes in the system support access to high-quality, high-value care for all patients.

INTRODUCTION

In March 2014, ASCO published its inaugural State of Cancer Care in America report, with the goal of increasing awareness among policymakers and the larger cancer community about improvements and current challenges in the delivery of high-quality cancer care, as well as about emerging issues that are likely to require future attention. This report is now an annual publication. It provides a comprehensive look at demographic, economic, and oncology practice trends that will affect cancer care in the United States each year.

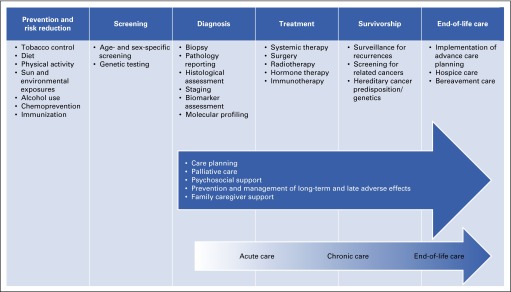

There were more than 14 million cancer survivors in 2014, and 1.7 million new diagnoses were expected in 2015.2,12 The impact of the disease is much broader than patients with cancer; friends and family members are also deeply affected. Many individuals serve as caregivers and provide social support to patients with cancer. In addition, people who have not been diagnosed with cancer participate in screening and prevention programs. The quality of cancer care across the care continuum must meet the needs of patients, families, and healthy individuals (Fig 1).

FIG 1.

Domains of the cancer care continuum. NOTE. Blue arrow identifies components of high-quality cancer care that span the cancer care continuum from diagnosis through end-of-life care. Graded arrow is another way of conceptualizing the time from diagnosis through end-of-life care. Data adapted.13

This year’s analysis of the state of cancer care reveals many promising advances. There are improvements in the development of precision medicine and immunotherapies, the ability to use big data to answer pressing research questions, and alternative payment models that have the potential to enhance the quality and value of cancer care. In addition, many patients with cancer have better access to care with the ongoing implementation of the ACA.

The 2016 State of Cancer Care in America report also describes ongoing concerns about the cancer care delivery system and its ability to take advantage of advances in treatment and care delivery. Additional efforts are needed to ensure that the results of research are translated into practice; that the reimbursement system rewards high-quality, high-value care; that patients have access to affordable care; and that disparities in patients’ access to care are reduced.

To organize the 2016 State of Cancer Care in America report, ASCO adapted the conceptual framework of the Institute of Medicine (IOM) for improving the quality of cancer care (Box 1).13 Chapter 1 focuses on trends in cancer research and the delivery of evidence-based care. Chapter 2 reviews the accessibility and affordability of cancer care, primarily from the perspective of patients. Chapter 3 explores the current landscape in the oncology workforce and oncology practices. Chapter 4 provides an overview of alternate payment models and efforts to improve the value of cancer care. The report concludes with a set of policy recommendations for the coming year.

Box 1. Framework for Organization of State of Cancer Care in America Report.

ASCO builds on the Institute of Medicine framework for “patient-centered, evidence-based, high-quality cancer care.”13 The components of the modified ASCO framework include:

Engaged patients: A system that supports all patients in making informed medical decisions consistent with their needs, values, and preferences in consultation with their clinicians who have expertise in patient-centered communication and shared decision making.

Adequately staffed, trained, and coordinated workforce: A system that provides competent, trusted, interprofessional cancer care teams that are aligned with patients’ needs, values, and preferences and coordinated with patients’ care teams and their caregivers.

Research to develop new therapies and evidence of effectiveness: A system that provides a robust infrastructure to support clinical research, such as clinical trials and comparative-effectiveness research, and uses evidence-based scientific research to inform medical decisions.

Learning health care information technology system for cancer: A system that uses advances in information technology to enhance the quality and delivery of cancer care, patient outcomes, innovative research, quality measurement, and performance improvement.

Translation of evidence into clinical practice, quality measurement, and performance improvement: A system that rapidly and efficiently incorporates new medical knowledge into clinical practice guidelines and clinical pathways, measures and assesses progress in improving the delivery of cancer care and publicly reports performance information, and develops innovative strategies for further improvement.

Accessible, equitable, and affordable cancer care: A system that is accessible to all patients and treats them equitably and that uses new payment models to align reimbursement to reward care teams for providing patient-centered, high-quality, high-value care and eliminating wasteful interventions.

High-value cancer care: A system that allows patients and their care teams to assess the value of various treatment options based on a transparent process; collective understanding; patient needs, values, and preferences; and accepted definition of what value in cancer care means.

New this year is the focus on a particular cancer treatment—immunotherapy—as a means of illustrating many of the themes of the report, their inter-relationship, and their impact on both outcomes of care and the overall patient experience. Advances in immunotherapy illustrate the importance of resolving issues in the health care delivery system (Box 2).

Box 2. Immunotherapy in Cancer.

Immunotherapies present an exciting opportunity to deliver a new, highly effective treatment to patients with cancer. These treatments are helping patients with many types of cancer, including cancers that previously have had no effective interventions. In fact, ASCO identified immunotherapy as the advancement of the year in its Clinical Cancer Advances 2016 report. This class of cancer treatment works by boosting the body’s natural defenses against cancerous cells.

However, the path toward achieving the full clinical benefit of immunotherapies faces many challenges. These challenges are indicative of the general obstacles facing the provision of high-quality care by the cancer care delivery system more broadly. The challenges to the cancer care delivery system—as highlighted in this report—are reviewed in the context of immunotherapy as follows:

Innovation Challenges

US investments in biomedical research have led to exciting and potentially transformative discoveries of many immunotherapies, including a new class of therapeutic agents called immune checkpoint inhibitors. Three drugs in this class—pembrolizumab, nivolumab, and ipilimumab—have now been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for a total of three indications. Promising approaches to immunotherapy, including cellular and vaccine therapies, require further research investment to bring them to fruition. Immunotherapy research requires collaboration across several scientific and medical disciplines and new approaches to clinical trial design. The focus on individual response to disease and treatment means that immunotherapy research must be conducted in many subgroups of patients (ie, patients with different races and ethnicities, ages, and comorbidities); there is also a need for ongoing monitoring of use after approval in real-world populations.

Like many precision medicine treatments, immunotherapy can be optimized by providing clinicians with better tools for identifying and delivering treatments to the right patients—and for avoiding treatments when patients are unlikely to benefit. However, realizing this valuable benefit requires research to identify biologic molecules in tissues, cells, or blood that signal tumor susceptibility to attack by the immune system. Research is also needed to develop laboratory tests that can detect these molecules. The relatively low participation by patients with cancer in clinical trials and the continuing challenges with reimbursement make the rapid development of this promising field an ongoing challenge.

Clinical Challenges

It is difficult for clinicians to remain up to date on the huge volume of new information emerging from research on immunotherapy, especially given the differences among immunotherapies in toxicity profiles and modes of administration when compared with other kinds of cancer treatments. For example, patients may experience autoimmune reactions that are unfamiliar to clinical oncologists, and progression of their cancer might seem to occur before a therapeutic response. Without knowledge of the unique features of immunotherapy, clinicians and patients may prematurely abandon the therapy before achieving benefit. Additional clinician education will be necessary to fill this knowledge gap. The novelty and significant cost of immunotherapies raise particular concerns regarding quality and access to care. Special focus will be needed to ensure they are available equitably, regardless of geography, practice type, or patient characteristic (eg, race or ethnicity or insurance status) and according to prevailing standards of care.

Value and Quality Challenges

High unit cost and inconsistent reimbursement policies across payers hinder patients’ access to immunotherapies. Emerging data suggest that using drugs in combination and at higher doses increases efficacy, making the prospect of an unsustainable financial burden—for both individual patients and the system—more likely.14,15 For example, a combination of nivolumab and ipilimumab was approved for melanoma in October 2015, with an annual cost of more than $250,000 per patient.16 Former President Jimmy Carter, who was diagnosed with advanced melanoma in August 2015, announced in December that he is cancer free after immunotherapy with pembrolizumab, which costs $150,000 per year.17 It is unclear if patients or payers can afford these treatments or whether the health system is able to offer them and remain financially sound. Efforts to reform payment and identify high-value treatments will be essential to integrating immunotherapies into routine practice in a thoughtful manner.

1. BALANCING PROGRESS AND CHALLENGES

The demand for cancer services continues to grow as the US population ages and grows. At the same time, new drugs, technologies, and clinical advancements are improving quality of care and survival for those diagnosed with cancer—noteworthy successes that themselves influence demand. This chapter reviews major areas where the United States has made progress in improving quality of cancer care in the past year and identifies ongoing challenges that will require attention moving forward.

PROGRESS IN CANCER CARE

In 2015, the United States made significant improvements in cancer care, as evidenced by declining incidence and mortality rates for many types of cancer, the growing number of new drugs and technologies available to patients, and advancements in precision medicine.

Declining Cancer Incidence and Mortality Rates

The overall number of newly diagnosed patients with cancer in the United States continues to increase, in large part because of a growing and aging population. However, cancer incidence (the rate of cancer per 100,000 individuals) has dropped significantly in the past decade.3 For all cancers combined, the incidence rate declined between 2003 and 2012, with an annual percent change of 0.7%. Over this period, incidence rates for many common cancers declined even more, including rates for prostate, lung, colorectal, cervical, and stomach cancers.3 Prevention efforts, including smoking cessation, infection control, and refined cancer screening processes, have contributed to these rate reductions.18

Cancer mortality has declined an average of 1.5% annually over the past decade, with even greater annual declines in mortality rates for the four most common cancers—breast, prostate, lung, and colorectal cancers.3 Many factors have contributed to these reductions, including expanded treatment options, improved therapeutic outcomes, and prevention efforts.19 As a result, the number of cancer survivors in the United States is expected to grow from 14.5 million in 2014 to 19 million by 2024.12

Growing Number of New Drugs and Technologies

People with cancer have access to a wider array of treatment options than ever before. In 2015, the FDA added 15 new drugs and biologic therapies to its list of more than 180 approved anticancer agents (Table 1) and expanded use for 12 previously approved treatments.1

Table 1.

| Generic Name | Brand Name | Cancer Type | Precision Therapy† | Target | Oral or Injection |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alectinib | Alecensa | NSCLC | Yes | ALK | Oral |

| Elotuzumab | Empliciti | Multiple myeloma | Yes | SLAMF7 (CS1/CD319/CRACC) | Injection |

| Necitumumab | Portrazza | Squamous NSCLC | Yes | EGFR (HER1/ERBB1) | Injection |

| Ixazomib | Ninlaro | Multiple myeloma | Yes | Proteasome | Oral |

| Daratumumab | Darzalex | Multiple myeloma | Yes | CD38 | Injection |

| Osimertinib | Tagrisso | NSCLC | Yes | EGFR | Oral |

| Cobimetinib | Cotellic | Melanoma | Yes | MEK | Oral |

| Trabectedin | Yondelis | Liposarcoma or leiomyosarcoma | No | Injection | |

| Irinotecan liposome | Onivyde | Pancreatic adenocarcinoma | No | Injection | |

| Trifluridine/tipiracil | Lonsurf | Colorectal cancer | No | Oral | |

| Sonidegib | Odomzo | Basal cell carcinoma | Yes | Smoothened (SMO) | Oral |

| Dinutuximab | Unituxin | Neuroblastoma | Yes | B4GALNT1 (GD2) | Injection |

| Panobinostat | Farydak | Multiple myeloma | Yes | HDAC | Oral |

| Lenvatinib | Lenvima | Thyroid cancer | Yes | VEGFR2 | Oral |

| Palbociclib | Ibrance | Breast cancer, ER positive, HER2 negative | Yes | CDK4, CDK6 | Oral |

Abbreviations: ALK, anaplastic lymphoma kinase; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; ER, estrogen receptor; FDA, US Food and Drug Administration; HDAC, histone deacetylase; HER, human epidermal growth factor receptor; NSCLC, non–small-cell lung cancer; VEGFR2, vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2.

Listed in chronologic order, from most recent to least recent.

Refers to therapies that are directed at discrete molecular targets.

An important development for 2015 came with FDA approval of filgrastim-sndz, the first biosimilar product licensed in the United States. Filgrastim-sndz and its reference product filgrastim help generate WBCs that fight infection in patients receiving chemotherapy. The ACA established a process in 2010 for the FDA to approve products as either biosimilar or interchangeable with biologic reference products, similar to generic versions of drugs. Biologic products are complex molecules that are created within living material, so the process to demonstrate similarity of the products is challenging. Manufacturers of biosimilar products must submit data to the FDA demonstrating that a product is “highly similar” to the reference product, with “no clinically meaningful differences in terms of safety and effectiveness.”20(p1) An interchangeable product has to meet additional standards and may be substituted for the reference product by a pharmacist without prescriber consultation.

The naming convention for biosimilar and interchangeable products has yet to be determined. In draft guidance published in August 2015, the FDA proposed adding a suffix of four randomly generated letters to the nonproprietary biologic as a means of identifying its biosimilar status.21 The FDA used as an example filgrastim-sndz (which has a suffix that corresponds to its manufacturer, Sandoz [Holzkirchen, Germany]). The biosimilar would be named filgrastim-bflm (a nonmeaningful suffix). In addition, the FDA asked for public comment on whether interchangeable products should have a unique suffix or should match the reference product. ASCO submitted a letter opposing the use of nonmeaningful suffixes,22 encouraging the FDA to use a naming convention that ensures safety and does not add any administrative burden for physicians and pharmacists. The WHO opposes the FDA mixing nonproprietary names and proprietary claims. Pharmacists, insurers, and group purchasing organizations are also opposed to the FDA proposal because of confusion that may deter use of biosimilar products. The trade group for brand manufacturers supports the use of suffixes but urged the FDA to make them meaningful.

The FDA has also approved screening and diagnostic tests that have the potential to improve outcomes for patients with cancer. In 2015, three new molecular diagnostic tests were approved: (1) the ALK (D5F3) CDx Assay (Ventana Medical Systems, Tucson, AZ), which identifies the anaplastic lymphoma kinase protein in non–small-cell lung cancer tissue specimens to determine whether crizotinib treatment will be beneficial; (2) the cobas KRAS Mutation Test (Roche Molecular Diagnostics, Pleasanton, CA), which detects KRAS gene mutations to ascertain effectiveness of colorectal cancer treatments cetuximab and panitumumab; and (3) the PD-L1 IHC 28-8 pharmDx test (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark), which measures programmed death-ligand 1 protein in nonsquamous non–small-cell lung cancer tissue samples to assess the potential benefit of nivolumab.25 In addition, a newly approved screening test, MAMMOMAT inspiration with tomosynthesis (Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany), uses cross-sectional images along with conventional two-dimensional mammography to enhance the accuracy of breast cancer detection and diagnosis.

Achieving the Promise of Precision Medicine

Scientific and medical communities continue to prioritize precision medicine as a means to significantly improve patient outcomes. This priority was highlighted by President Obama in his 2015 State of the Union address and further strengthened by his $215 million commitment to increase research funding with the Precision Medicine Initiative.26 In cancer care, precision or targeted therapies work by exploiting the molecular underpinnings of cancer. The precision of cancer treatments has become more sophisticated with each passing year. Therapies that attack multiple genetic drivers of cancer in combination or harness the body’s own immune system to attack tumor cells have improved outcomes for patients with difficult-to-treat cancers. Of all the newly FDA-approved cancer therapies listed in Table 1, 12 (62.5%) are classified as precision therapies. With the aid of evidence-driven diagnostic testing, physicians can often identify targeted treatments most likely to work for individual patients with cancer—and avoid treatments that are unlikely to help, thereby saving time and sparing patients and families from potential toxicities and costs.

Immunotherapy has been a particularly fruitful application of precision medicine and has garnered momentum within the cancer community. One method of activating the immune system to fight cancer is to prevent brakes or checkpoints from suppressing immune response. Three immunotherapy drugs that work in this manner, so-called immune checkpoint inhibitors—pembrolizumab, nivolumab, and ipilimumab—were approved in recent years for treating melanoma and are showing promise in other cancers. In 2015, nivolumab and pembrolizumab both received FDA approval for treatment of non–small-cell lung cancer based on compelling clinical research findings.1,27 Other clinical trials have shown notable benefits for patients with liver cancer, head and neck cancer, stomach cancer, bladder cancer, and Hodgkin lymphoma. In 2015, data were also released showing that some patients with melanoma benefit from use of immune checkpoint inhibitors in combination.28 Immunotherapy holds great promise to improve the care and quality of life for patients with cancer, but it also illustrates many of the challenges that persist in today’s cancer care delivery system (Box 2).

CHALLENGES IN CANCER CARE

Despite significant progress made in 2015 toward improving the quality of cancer care, many ongoing challenges persist. These include the rising demand for and complexity of cancer care, immovable mortality rates for some cancers, ongoing health disparities, and static funding for cancer research.

Rising Rates for Some Types of Cancer

Nearly 1.7 million new cancer cases were diagnosed in 2015, bringing the total number of Americans living with cancer to 14.5 million.2 The overall number of newly diagnosed patients with cancer is expected to grow by 45% between 2010 and 2030.29

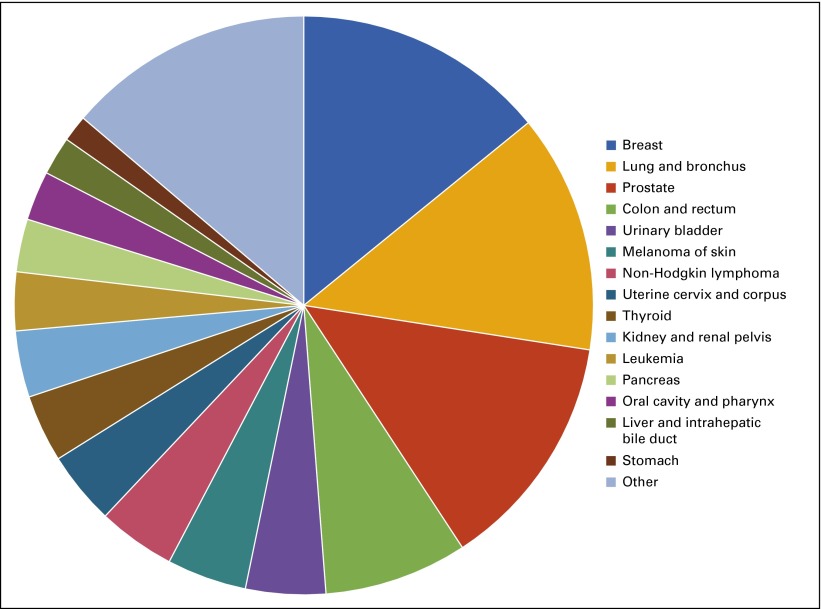

Among new cancer cases, nearly half (46%) are diagnosed as one of the four most common cancers: (1) breast, (2) prostate, (3) lung, or (4) colon cancer (Fig 2).2,3 A recent analysis shows that cases of breast cancer—the most commonly occurring cancer—will increase by 50% between 2011 and 2030.30

FIG 2.

Distribution of common cancer diagnoses, 2015.

Between 2003 and 2012, melanoma, thyroid cancer, kidney cancer, liver cancer, and pancreatic cancer incidence rates significantly increased.3 By one recent projection, thyroid cancer will replace colon cancer as the fourth leading cancer diagnosis by 2030, in large part because of better thyroid cancer detection.19 As overall cancer incidence increases and shifts between cancer types in the coming years, demand for screening and treatment services will change, challenging the cancer care delivery system. In addition, the millions of Americans who develop and survive cancer will require long-term care and monitoring to detect and treat recurrence or new cancers. They may also require support for long-term physical, emotional, psychosocial, and financial adverse effects as a result of their treatment.

Because patients with cancer are living longer, an increasing proportion of new cancer cases occur in patients with a previous history of cancer. Approximately 19% of cancers diagnosed from 2005 to 2009 were not first cancers, compared with only 9% diagnosed from 1975 to 1979.31 Patients diagnosed with second cancers may experience heightened distress and may face new barriers to treatment, including lifetime tolerability limits for particular radiotherapy and chemotherapy regimens.

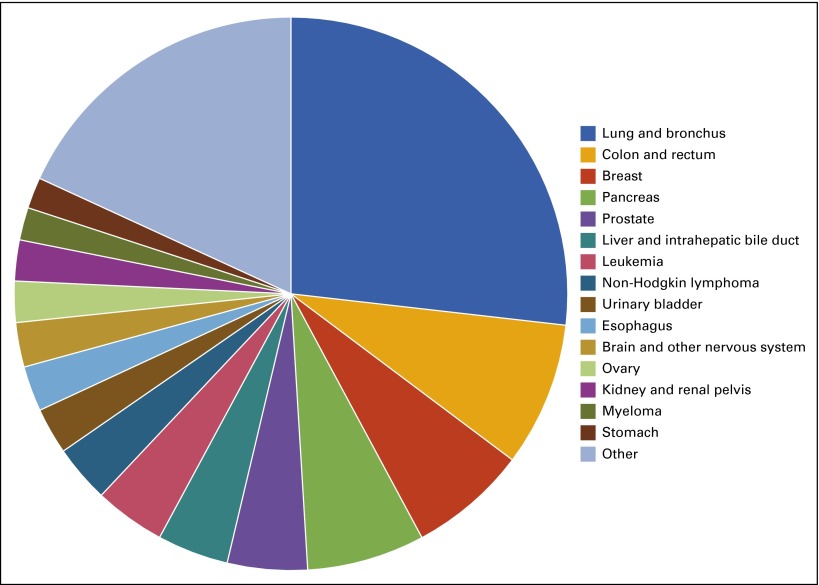

Despite the progress made toward reducing mortality for many types of cancer, cancer remains the second leading cause of death in the United States, accounting for nearly a quarter of deaths. An estimated 589,430 Americans died as a result of cancer in 2015, with lung cancer causing more than a quarter (27%) of these deaths (Fig 3).2 Mortality rates for some cancers, such as bladder cancer, brain cancer, and melanoma, have remained steady over the past decade, and pancreatic and liver cancer mortality rates have increased.3 These trends serve as a reminder that more effort is needed to improve outcomes for all patients with cancer.

FIG 3.

Distribution of common cancer deaths, 2015.

Ongoing Health Disparities

Substantial disparities in cancer incidence and mortality remain a feature of the current health care system. In particular, there are striking differences in cancer incidence and mortality rates across racial and ethnic groups. According to recent data from the National Cancer Institute (NCI), African Americans are 3% more likely to develop cancer than whites and are 18% more likely to die as a result of cancer.3 These discrepancies can be more pronounced for certain cancers and between men and women.

An October 2015 report from the American Cancer Society (ACS) found that racial disparities in breast cancer are on the rise.4 According to this analysis, although breast cancer incidence has remained relatively stable among white women, the rate among African American women—historically lower than that of whites—has risen this year to surpass those of all other racial groups. Because African American women with breast cancer are diagnosed at a younger age and have higher mortality rates than white women, these new data are concerning—especially in light of recent progress made in breast cancer outcomes.

Racial and ethnic health disparities arise from a complex set of factors that include education, socioeconomic status, health insurance status, health behaviors, and presence of environmental and behavioral risk factors. It is difficult to tease apart racial or ethnic differences that are biologically based from differences related to interactions between race or ethnicity and environmental and social variables that limit access to care. The ACS breast cancer study hypothesizes that increases in breast cancer rates in African American women may be a result of rising obesity and changing reproductive behaviors, but it also notes that black women are more likely to have an aggressive type of cancer that may have a genetic basis.4

Geographic location also plays a role in cancer incidence and survival.32 Some geographic disparities in cancer incidence and outcomes may be exacerbated by state decisions on Medicaid expansion and differing levels of care available to poor and minority residents, as well as environmental risk factors. Distribution of oncologists across the United States, relative to where patients reside, may present access issues that further affect disparities in outcome. In the face of continuing barriers to access, especially for vulnerable populations, ASCO has continued its efforts to provide the oncology workforce with resources that increase awareness of cancer disparities and actions to address these disparities. Visit www.asco.org/healthdisparities for more information.

Increasing Complexity of Cancer Care

A major challenge to improving quality of cancer care is its complexity. Patients differ in personal characteristics (eg, age, genetic makeup, and physical health), cancer diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment preferences. This section of the report focuses on three examples of cancer care complexity that have received recent public attention: (1) cancer screening, (2) implementing precision medicine treatments, and (3) the aging of the US population, resulting in patients with cancer who are older and have more comorbidities than younger cohorts.

Cancer screening

Cancer screening programs are aimed at detecting cancer early, before symptoms are present. Early detection can help patients avoid the need for aggressive treatment and improve overall outcomes. The complexity involved in implementing cancer screening is based on the need to avoid over- and underscreening, as well as to make appropriate screening decisions when the evidence is ambiguous as to the potential health benefits to the patient. Furthermore, because screening tools are not perfectly sensitive or specific, they can lead to false-positive or false-negative results.

Screening capabilities and subsequent intervention options vary tremendously by cancer type. For breast, colorectal, and cervical cancers, there is clear evidence that routine screening among appropriate age groups, followed by intervention, significantly improves survival. A recent systematic review found that colorectal cancer screening (colonoscopy and sigmoidoscopy) programs reduced cancer mortality by 46% to 66% in observational studies analyzed.33

For many other cancers, the risk–benefit considerations are not so straightforward. For instance, the ACS, which has taken an aggressive stance on mammography screening for breast cancer in past years, updated its guidelines in October 2015 to recommend screening at later ages and with less frequency than previously recommended. Also in 2015, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) released draft updates to its breast cancer screening guidelines, reaffirming that screening before age 50 years for women at average risk is not supported by current clinical evidence.34

The USPSTF has also reviewed evidence on prostate, bladder, skin, and oral cancer screening and decided not to publish screening recommendations for these cancers because of inconclusive findings.35 Inconsistencies in guidelines and inconclusive data make it difficult for patients and physicians to make appropriate screening decisions. Furthermore, because the ACA hinges preventive services coverage on USPSTF guidelines, some stakeholders have expressed concern that screening will not be offered to all individuals who could potentially benefit.36

In addition, there are risks to patients’ health from both over- and underscreening. Patients who are underscreened risk the possibility of a cancer not being detected early in its disease trajectory, thus potentially experiencing worse outcomes. Current guidelines recommend screening for breast, colon, and colorectal cancers in susceptible populations. However, a recent analysis of 2013 national survey data conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention uncovered the following age-adjusted findings, which are lower than the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Healthy People 2020 national targets for screening in these three areas—suggesting many patients may be underscreened37:

72.6% of women age 50 to 74 years reported recent mammography.

80.7% of women age 21 to 65 years reported a recent Pap test.

58.2% of respondents age 50 to 75 years reported recent colorectal screening tests.

Conversely, one of the major risks of overscreening is that a test may detect benign tumors and malignant tumors unlikely to become clinically significant during a patient’s natural lifespan. Patients who undergo these screening procedures can experience nontrivial health consequences, including emotional distress and unnecessary or detrimental treatment, as well as financial burden.

Implementing precision medicine

Precision medicine has enormous potential to improve the quality of cancer care. However, there are some challenges to achieving these benefits in clinical practice. Testing for specific individual genetic mutations such as EGFR in lung cancer and BRAF V600E in melanoma has become commonplace in oncology practice. There is also growing interest in multiplex genetic testing, where tumors are evaluated for changes in several cancer-related genes at once. Little is known about how multiplex genetic information is used by physicians and patients.

A recent survey found that 22% of physicians at a major cancer center had low confidence in their own knowledge of genomics; however, 42% were willing to disclose uncertain findings of genetic testing to patients.38 Some institutions have implemented molecular tumor boards to provide education and clinical guidance, but guidelines or other decision support will be important as the practice of multiplex genetic testing becomes more widespread.39 In addition, as more practices begin providing immunotherapies, clinicians will need information about safety concerns associated with this class of drugs and the appropriate management of serious adverse effects.

Changing demographics

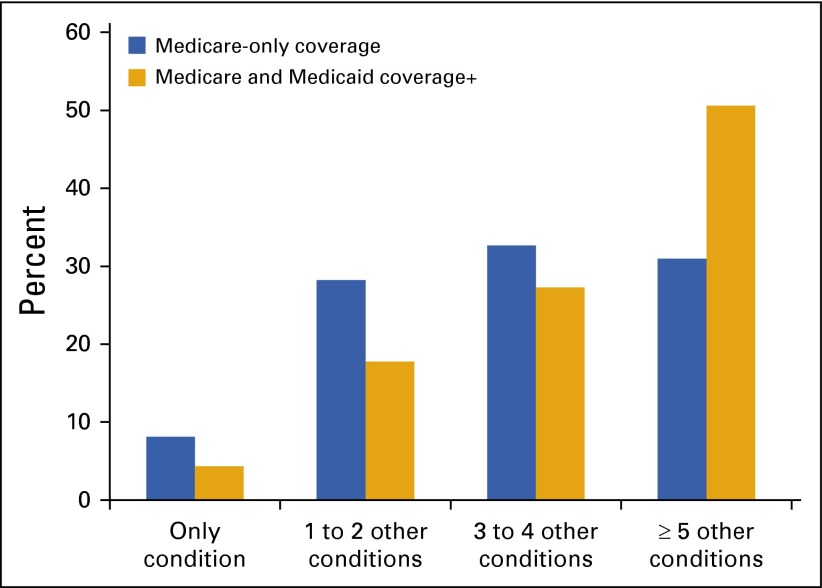

An important and growing demographic in cancer is the number of elderly Americans. The majority of new cancer cases are diagnosed among those age 65 years or older.40 This population is also susceptible to other chronic diseases, such as diabetes, heart disease, and Alzheimer’s. Chemotherapy and other cancer treatments can further increase the risk of developing chronic disease symptoms, especially those related to cardiovascular health. Among Medicare beneficiaries with breast, colorectal, lung, or prostate cancer, 91.9% had one or more other chronic conditions (Fig 4).41 Medicare–Medicaid dual eligible beneficiaries have an even higher prevalence of comorbidities (95.7%; Fig 4).

FIG 4.

Distribution of chronic disease comorbidities among Medicare beneficiaries with cancer. (*) Other conditions include: Alzheimer’s disease, related disorders, or senile dementia; arthritis (including rheumatoid and osteoarthritis); asthma or atrial fibrillation; autism spectrum disorders; chronic kidney disease; chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; depression; diabetes (excluding diabetic conditions related to pregnancy); heart failure; hyperlipidemia (high cholesterol); hypertension (high blood pressure); ischemic heart disease; osteoporosis; schizophrenia or other psychotic disorders; and stroke or transient ischemic attack.

The growing number of patients with cancer and serious chronic conditions presents new challenges, because providers must assess and manage comorbidities in treatment planning, medication prescribing and adherence (eg, awareness of contraindications), and coordination of care with primary care physicians or other chronic disease specialists. With so many patients with cancer having multiple conditions, it will be essential to consider this complexity in assessing workforce and practice needs.

The difficulties of caring for an aging population are further complicated by the fact that the elderly are often under-represented in cancer clinical trials. In general, only approximately 3% of US patients with cancer participate in clinical trials—and these patients tend to be younger, healthier, and less racially and ethnically diverse than the overall population of patients with cancer.42 Thus, our evidence base for treating older patients with cancer is quite limited. In 2015, ASCO released a policy statement advocating for increased research on older adults with cancer, a population disproportionately affected by cancer (Box 3).

Box 3. Statement on Improving Evidence Base for Treating Older Adults With Cancer.

ASCO convened a subcommittee of experts to consider the role for and engagement of older adults in clinical research. The following recommendations were issued43:

Use clinical trials to improve the evidence base for treating older adults with cancer.

Leverage research designs and infrastructure for generating evidence on older adults with cancer.

Increase US Food and Drug Administration authority to incentivize and require research involving older adults with cancer.

Increase clinicians’ recruitment of older adults with cancer to clinical trials.

Use journal policies to improve researchers’ reporting on the age distribution and health risk profiles of research participants.

The full statement is available online at http://www.asco.org/sites/www.asco.org/files/older_adults_asco_statement_2015.pdf.

Funding for Cancer Research

The progress in immunotherapy and other areas of cancer research highlighted in this chapter was made possible by research investments from previous decades. Sustained funding of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the NCI is critical to continuing progress against cancer through the development and delivery of new cancer therapies to patients. However, as cancer care demand and complexity increase, research funding at the federal level has failed to keep pace.

The need for increased research funding was recognized in a rare instance of bipartisan agreement within the US Congress. In July 2015, the House of Representatives passed the 21st Century Cures Act (H.R. 6) by a wide margin. The bill included $10 billion ($2 billion per year for fiscal years 2016 to 2020) in mandatory spending for the NIH to focus on precision medicine and young investigators and $550 million ($110 million per year for fiscal years 2016 to 2020) in mandatory spending for the FDA. ASCO supports H.R. 6 and is working collaboratively with the Senate to achieve passage of the legislative initiatives.

In late 2015, the House and Senate approved funding increases for 2016 for the NIH, including $200 million for the new Precision Medicine Initiative and an increase of $264 million (5.3%) for the NCI. This increase in appropriations came after a decade-long decline in NIH funding in real dollars, potentially signifying a regenerated commitment to medical research.

The cancer community also makes more out of available funding by leveraging clinical data to study outcomes of patients receiving treatment in practice. There is a growing recognition that much can be learned from the experiences of the millions of patients receiving cancer care throughout the United States. The availability of EHR data, combined with the computing capability of informatics and big data systems, presents an invaluable opportunity for rapid-learning systems, in which real-world clinical data are collected and analyzed to help guide clinical decision making. However, the current interoperability of many EHRs poses a significant barrier to realizing the vision of using big data to its full potential.

In the era of precision medicine, only small subsets of patients may have the appropriate molecular targets for specific targeted therapies. Clinical trials testing such new therapies have to be designed to accrue sufficient numbers of patients to assess treatment efficacy and safety. There have also been accounts of exceptional responders to cancer therapies—patients who respond uncharacteristically well to treatments.44 Cataloging and studying these responses may lead to new uses of drugs currently available on the market.

CONCLUSION

Advances in science and technology, including great promise and tangible advances in precision medicine (which includes targeted and immunotherapies), have contributed to substantial progress in cancer detection and treatment. However, patients with certain tumor types and from some demographic groups are not benefiting fully from the advances in cancer care. In addition, although precision medicine is offering promising new avenues for cancer treatment, it is also challenged by a vast array of unanswered questions. Sustained research funding and infrastructure are required to seize opportunities to improve treatment options for patients. This should include support for research using informatics and big data systems that can talk to one another and provide clinical decision support to ensure rapid learning and optimal patient care.

2. CANCER CARE ACCESS AND AFFORDABILITY: ENSURING ALL PATIENTS CAN RECEIVE CURRENT AND DEVELOPING THERAPIES

Nationwide efforts to expand the accessibility and affordability of health care have benefited millions of Americans—but not all patients have benefited equally. This chapter discusses recent changes in access and affordability in cancer care, highlighting both positive trends and ongoing concerns for the oncology community. The chapter begins with a brief overview of the state of health insurance in the United States, followed by a summary of the benefits of the ACA as it applies to access to treatment of current and future patients with cancer. The chapter also details ongoing problems with design and implementation of the law, as well as implications of these concerns for cancer care. The final section examines the cost of cancer care, with an emphasis on financial burdens to patients.

HEALTH INSURANCE AND ACCESS TO CANCER CARE

For the past 50 years, the federal government has engaged in efforts to improve accessibility and affordability of health care for US patients, mainly through its three landmark insurance programs: (1) Medicare, (2) Medicaid, and (3) the ACA.45 As 2015 marked the 50th anniversary for Medicare and Medicaid, the ACA reached its fifth anniversary and continues toward full implementation. These laws have had profound effects on the US health care system and the state of cancer care. Although progress is incomplete, the programs provide health insurance for millions of Americans and have a profound impact on how patient care is organized and delivered.

Medicare and Medicaid, the oldest and largest government-run health care programs in the nation, were established in 1965 to address the high rate of uninsured among the most vulnerable populations in the nation: older adults and low-income individuals. Today, they cover 111 million people (one in three Americans) and account for 39% of national health care spending, including a large proportion of the cost of cancer care.45

Medicare, the federal insurance program for the elderly and permanently disabled, is widely credited with achieving almost universal access to health care for older adults while making it affordable for enrollees.45 Current enrollment includes 45 million older adults and 9 million adults with permanent disabilities. The Medicare Payment Advisory Commission projects an increase from today’s current 54 million to more than 80 million beneficiaries by 2030 as the baby-boom generation ages into the program.46 Because the majority of patients with cancer and cancer survivors are older adults, Medicare provides a critical support system for cancer care.

Medicaid is administered through a federal partnership with individual states and has historically provided coverage to low-income children and adults. The program has undergone considerable changes since first implemented, including a recent expansion of coverage related to provisions in the ACA. Medicaid now enrolls approximately 70 million people annually and provides the majority of insurance coverage for people with limited incomes, including pregnant women and children, elderly adults, and people who are disabled.45 It is also an important source of coverage for patients with cancer.47

The ACA is the most recent federal health care program, aiming to reach the millions of uninsured Americans who are not eligible for Medicare and/or Medicaid and who do not receive health insurance through employers. The remainder of this section discusses important 2015 developments in cancer care related to ACA implementation, including areas of progress and areas of concern.

ACA: Ongoing Progress

The ACA is now in its fifth year of operation. It has completed three open-enrollment periods for Medicaid and marketplace coverage. The following sections discuss two important changes related to the law: (1) expanded insurance coverage and (2) expanded benefits for cancer services.

Expanded insurance coverage

The ACA has extended insurance coverage to millions of Americans, and evidence suggests that this coverage is improving access to affordable care and having a positive impact on health.5,6 Recent data show the number of uninsured has decreased by approximately 17 million people since implementation.48 In 2015, uninsured rates fell in all states, with the largest declines occurring in states with expanded Medicaid programs.6 Families with incomes at or below 138% of the federal poverty level experienced the biggest increase in insurance coverage. Hispanics and African Americans experienced greater declines in uninsured rates than whites.6 These findings suggest that the ACA is fulfilling its goal of increasing access to health insurance for people who were previously uninsured, with important coverage gains in minority and poor populations.

One of the major assumptions underlying the ACA was that expanding people’s access to insurance would affect their health behaviors, use of health care services, and health outcomes. New data indicate that people who obtained coverage through the ACA marketplace and Medicaid expansion are using their plans to access care that was previously unaffordable, are increasingly accessing medicine and providers, and are largely satisfied with their coverage regardless of insurance type.45,47,48

These findings suggest that the ACA has increased patients’ access to a spectrum of health care services, which may eventually improve overall health. A recent study comparing pre-ACA and early 2015 national survey responses found that self-reported health status had improved over time, with 3.5% fewer respondents citing poor to fair health.6 As more time passes, it will be important to examine the impact of the law on health outcomes, including cancer.

The law may also help to decrease long-standing health disparities related to lack of insurance, because Medicaid enrollees have better access to care and fewer unmet health needs than the uninsured. However, not all insurance plans are equally likely to reduce disparities (as described under the section on areas of concern).

Benefits for patients with cancer

The ACA includes a number of provisions that benefit patients with cancer, including:

Prohibition against coverage exclusions based on pre-existing conditions. This means that insurers cannot deny health insurance to individuals because they have a history of cancer.

Elimination of lifetime caps and annual spending limits. This provision is designed to prevent insurance companies from stopping payment for services once a specified dollar amount has been reached. Because treatment of cancer may involve both high annual costs and health care costs that extend over many years, this benefit is likely to reduce cancer-related bankruptcies for patients with cancer and their families.

Expansion of required coverage for routine health care services and basic levels of care, including ambulatory services, mental health services, and rehabilitative services that become critical once the acute stage of cancer treatment has been completed. Coverage also includes chronic disease care, an important benefit for cancer survivors, and palliative and hospice services for care at the end of life.

Coverage of routine costs associated with clinical trial participation. Most insurance policies are required to allow patients with cancer to enroll in clinical trials as a basic covered service.

Coverage of essential screenings, including tests used to detect cancer, at no cost to the patient. Because people without insurance are likely to forgo routine health screenings, this coverage is likely to promote earlier detection of cancer.

Coverage for wellness and preventive care, such as weight loss and smoking cessation—two strategies critical for reducing the risk of cancer onset or progression.

Provision allowing young adults to remain on their parents’ insurance policies until age 26 years. This provision provides continuity of services for individuals diagnosed with cancer as children and helps to decrease the number of uninsured young adults who are not eligible for employer-sponsored insurance.

An estimated 160,000 people with cancer will be part of the 16 million Americans who gain coverage through Medicaid and CHIP by 2019.47 Data on the direct impact of these benefits on cancer care are limited. However, the expansion of access through the ACA to a wide spectrum of health care services should expand access to critical services for patients with cancer and their families. In one recent study, researchers observed an increase in early-stage cervical cancer diagnoses among women age 25 years or younger after the ACA insurance expansion began, suggesting that newly insured women were taking advantage of preventive services.49

ACA: Ongoing Concerns

Although the ACA has increased millions of people’s access to health insurance, serious policy concerns about limitations of the law continue to drive the health care debate. This section highlights four broad areas of ongoing concern: (1) persistent gaps in health care coverage, (2) incomplete Medicaid expansion, (3) marketplace coverage gaps, and (4) clinical trial coverage.

Persistent gaps in health care coverage

Although millions of individuals have gained access to insurance through the ACA, coverage expansion is slowing, and millions of Americans remain uninsured or underinsured.5,48,50 The Congressional Budget Office estimates that approximately 35 million nonelderly adults were without health insurance in 2015.7 The uninsured include low-income people living in states that did not expand Medicaid, people without employer-based health coverage who chose not to purchase health insurance in the marketplaces, and undocumented immigrants who are not addressed by the law.5,51 An additional 31 million individuals were deemed underinsured because their deductible and/or out-of-pocket costs were high relative to their household income.8 Slightly more than 50% of underinsured adults had insurance through their employers, with the remainder having marketplace, Medicare, or Medicaid policies.8

Without health insurance, patients with cancer face tremendous obstacles to receiving the care they need, from prevention through treatment and survivorship and care at the end of life. Insured patients with cancer are diagnosed earlier, have a better chance of survival, enjoy greater financial stability, and experience a higher quality of life. For these reasons, expanding access to health insurance to more Americans remains a critical issue in cancer care, even after passage of the ACA.52

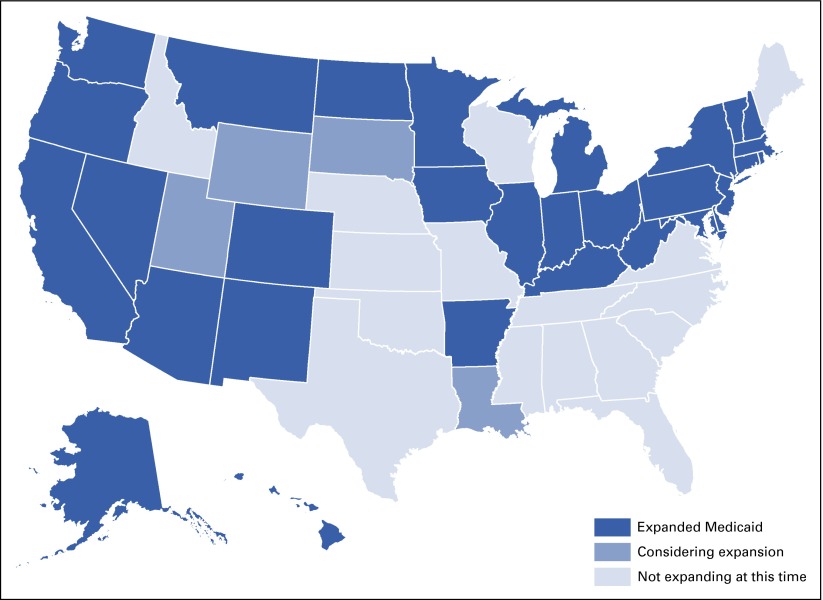

Incomplete Medicaid expansion

The US Supreme Court ruled in 2012 that states did not have to expand Medicaid, and this decision may have contributed to the continuing high rates of uninsured. Only 30 states and Washington, DC, had expanded Medicaid by the end of 2015 (Fig 5).53 In states that did not expand Medicaid, the rates of uninsured are more than twice those of the states that did expand. Differing decisions on Medicaid expansion have also created significant inequities in health coverage among the states and will likely exacerbate regional disparities in cancer detection rates, quality of care, and outcomes.47

FIG 5.

Status of state Medicaid expansion decisions.

Even within expansion states, there are issues of differences in benefits for individuals who enrolled in plans created before the ACA and those who enrolled under ACA policies. Many of the poorest, most vulnerable recipients receiving coverage through state-run programs may be in plans that do not meet ACA standards for prevention and screening, treatment, or survivorship care.

Policymakers are also concerned about the quality of care offered to Medicaid recipients compared with privately insured patients. Low physician and hospital reimbursement rates in many states limit the pool of providers who are willing to accept Medicaid patients or limit the range of services offered to beneficiaries.45 For example, a recent study found that women with Medicaid were less likely than women with private insurance to be referred for preventive services, such as breast examinations and Pap tests.54 High drug copays are also common in many pre-expansion Medicaid programs. In addition, lack of mandated access to clinical trials also limits the range of treatment options for Medicaid recipients in some states (as discussed in the section on clinical trial coverage).47

To address these concerns, ASCO has made Medicaid reform a high priority and, in 2014, published an extensive list of policy recommendations, with the goal of ensuring access to high-quality, high-value cancer care for Medicaid beneficiaries. Visit www.asco.org/Medicaid for details.

Marketplace coverage gaps

In 2015, the Supreme Court ruling in King v Burwell upheld federal subsidies for marketplace plans, preserving subsidies for more than 6 million Americans.55 However, recent reports that marketplace cooperatives in many states are in financial difficulty or closing raise concern that potential enrollees will face a limited selection of more expensive private insurance plans.56 Individuals without coverage may continue to delay recommended health screenings that detect cancer, decide to forego needed treatments, or face financial hardship while living with cancer.

Clinical trial coverage

The ACA created the first federal law requiring private insurers to cover routine care costs for patients participating in clinical trials. The law applies to a wide range of private and federal insurance plans, including Medicare but excluding Medicaid and some private insurance companies. Although the coverage mandate is now in statute, the federal government has not yet issued regulations to guide implementation, and coverage may remain problematic for patients currently enrolling in trials.57 A 2014 survey of sites conducting clinical trials found that 63% experienced denial of coverage for patients with cancer, even in states that had laws in place mandating coverage.57 These findings reinforce concerns that patients seeking treatment in clinical trials may be denied mandated coverage of state-of-the-art treatment programs until federal guidelines for implementation and enforcement are in place.

Patients with cancer who are covered under Medicaid policies also are likely to be denied coverage for clinical trial participation. Because Medicaid was excluded from the clinical trial mandate, states are not required to include this coverage in their Medicaid policies, and not all states provide such coverage for their Medicaid beneficiaries.58 This creates a significant coverage disparity among states, affecting the most vulnerable poor and minority residents who form the majority of Medicaid recipients.47 To ensure that all Medicaid enrollees have access to the treatment options offered by clinical trials, ASCO has included clinical trial coverage in its list of policy suggestions for Medicaid reform.59 Certain other policies were also excluded from the mandate, and people who are insured under these grandfathered policies also have no guaranteed coverage for the costs associated with clinical trial participation.60

A final concern surrounding clinical trial participation is related to coverage for phase I clinical trials. These trials often represent the first-in-human studies of new treatments and are used to both determine dosage and schedule and obtain evidence of benefit for new treatments.60 In today’s trials of targeted therapy, phase I trials often provide great benefit. Private insurance companies are required to cover participation in phase I to IV trials under the ACA, but participation is limited under Medicaid, Medicare, and some grandfathered health plans. ASCO recently updated its policy statement on the importance of phase I trials in cancer treatment and research to ensure patients have the option of participating in these trials (Box 4).

Box 4. Statement on Phase I Clinical Trial Coverage.

In December 2014, ASCO updated its position on the conduct of phase I clinical trials based on input from the Cancer Research Committee, a panel of experts with various roles in clinical research—including patient advocacy. Concerning insurance coverage of phase I clinical trials, ASCO makes the following recommendations:

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services should recognize that phase I cancer clinical trials meet the therapeutic intent requirement of the National Coverage Determination for routine patient costs in clinical trials.

State Medicaid programs should reimburse for routine patient costs associated with clinical trials, including phase I trials.

Visit http://www.asco.org/sites/www.asco.org/files/phase_1_trials_in_cancer_research-_asco_policy_statement.pdf for the full statement.

RISING COST OF CANCER CARE

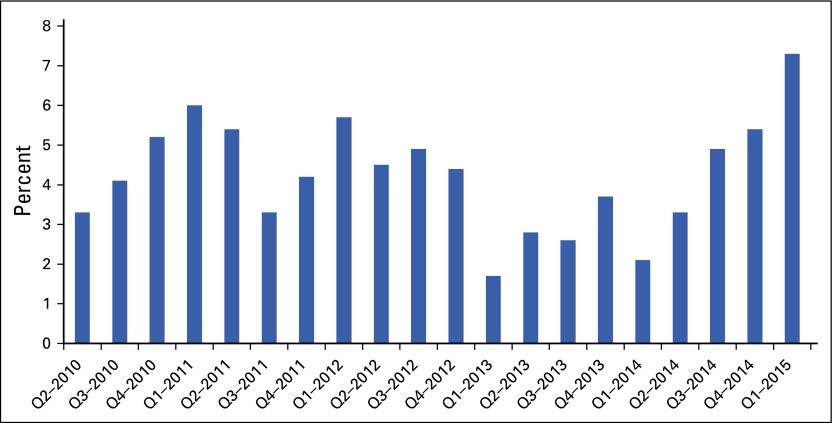

The rising cost of health care presents a fiscal challenge to the United States. Although the rate of growth in cost temporarily slowed during the recent economic downturn, health care spending has once again picked up speed.9 As seen in Figure 6, health service expenditures grew from 2.1% in the first quarter of 2014 to 7.3% in the first quarter of 2015.61 The reasons for this upturn seem to be higher overall rates of use of health services and a greater number of individuals insured by the ACA.

FIG 6.

Health services spending growth in recent quarters (Qs).

Costs associated with cancer care are rising more rapidly than costs in other medical sectors. Given current rates of growth, cancer-related costs may reach as high as $173 billion by 2020.10 The reasons for the high cost of cancer care are varied, including development of new technologies and treatments, consolidation of oncology practices into hospital-based practices where care costs more, and rising drug prices. Costs associated with newly insured patients, expanded prevention and screening programs, and growing populations of new patients with cancer and survivors will also likely contribute to future cost increases.

Despite spending far less on cancer care, many countries achieve similar or better cancer outcomes than the United States.62 Furthermore, health care costs in the United States have severe financial implications for patients with cancer and survivors and may place care out of the financial reach of many patients, despite the gains in insurance access discussed previously. Affordability of cancer care remains a significant policy concern for ASCO in 2016. Two issues of critical importance for patients with cancer are: (1) cost of cancer drugs and (2) increased patient burden associated with rising deductibles and cost shifting.

Cost of Cancer Drugs

Although drug costs represent only a small portion of overall cancer care costs in the United States, they receive outsized attention because of their alarming price tags and substantial price increases in recent years. A single cancer drug can cost nearly $300,000 per year.63 Cancer drugs account for seven of the 10 most expensive drugs reimbursed through Medicare Part B (Table 2). For the Medicare Part D prescription program, CMS paid a total of $1.35 billion for the cancer drug lenalidomide in 2013—making it one of the 10 most expensive drugs that year despite being used by many fewer beneficiaries than competing drugs on list.65

Table 2.

Ten Most Expensive Medicare Part B Payments for Drugs Delivered in Physician Office and at Home

| HCPCS | Name | Dose (mg) | Average Sales Price per Dose | Total Medicare Annual Payment | FDA-Approved Indication |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| J2778 | Ranibizumab injection | 0.1 | $396.43 | $1,310,751,832 | Macular degeneration, macular edema, diabetic macular edema |

| J0178 | Aflibercept injection (ophthalmic) | 1 | $980.50 | $1,239,918,536 | Macular degeneration, macular edema, diabetic macular edema, diabetic retinopathy |

| J9310 | Rituximab injection | 100 | $708.68 | $852,588,010 | Non-Hodgkin lymphoma, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, rheumatoid arthritis, Wegener’s granulomatosis and microscopic polyangiitis |

| J1745 | Infliximab injection | 10 | $74.34 | $785,929,255 | Crohn’s disease, pediatric Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, pediatric ulcerative colitis, rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic arthritis |

| J2505 | Injection, pegfilgrastim | 6 | $3,387.93 | $641,285,763 | Febrile neutropenia |

| J9035 | Bevacizumab injection | 10 | $66.65 | $593,988,145 | Metastatic colorectal cancer; NSCLC; glioblastoma; renal cell carcinoma; cervical cancer; epithelial ovarian, fallopian tube, or primary peritoneal cancer |

| J0897 | Denosumab injection | 1 | $14.45 | $505,871,083 | Skeletal-related events, giant cell tumor of bone, hypercalcemia of malignancy |

| J9355 | Trastuzumab injection | 10 | $82.49 | $289,275,777 | Breast cancer, gastric or gastroesophageal junction adenocarcinoma |

| J9305 | Pemetrexed injection | 10 | $60.27 | $287,737,319 | NSCLC, mesothelioma |

| J9041 | Bortezomib injection | 0.1 | $46.08 | $283,007,272 | Multiple myeloma, mantle cell lymphoma |

NOTE. Drugs in bold font are used to treat patients with cancer. Pricing data reflect fourth quarter 2014 payment rates, which corresponding to second quarter 2014 manufacturer reports. Final column lists FDA-approved indications, but Medicare may also provide reimbursement for additional, so-called off-label, uses. Data adapted.64

Abbreviations: FDA, US Food and Drug Administration; HCPCS, Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System; NSCLC, non–small-cell lung cancer.

Precision therapies are particularly expensive and are being used by an increasing number and proportion of patients with cancer. As noted during a plenary session at the 2015 ASCO Annual Meeting, the immunotherapy treatment ipilimumab is “approximately 4,000 times the cost of gold.”66,67

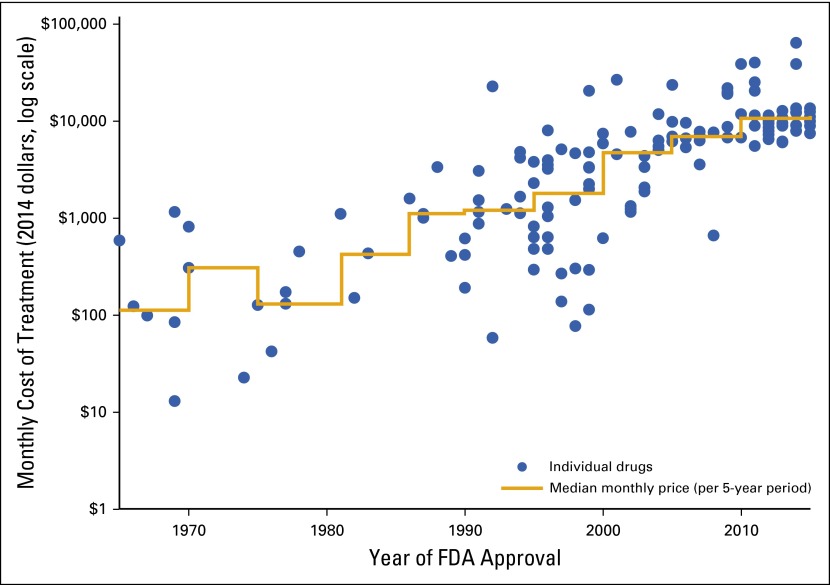

Rising drug costs are a concern for both the health care system and patients with cancer and their families. Figure 7 illustrates the growth in the monthly cost of drugs over time. Even more concerning, studies are beginning to show that many of these drugs provide greater benefit when delivered at higher doses or in combination, which could result in annual price tags into the millions.28,66 Escalation in individual unit cost of new drugs—along with the growth in the number of such drugs introduced to the market—raises serious concerns about sustainability for patients and the overall health care system.

FIG 7.

Median monthly costs for new cancer drugs at time of US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval, 1965 to 2015 (data from Peter Bach, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY).

Drug manufacturers attribute high drug costs to the cost of drug development and the limited markets for specialty drugs, but they do not publicly disclose their margins of profit—making it difficult for payers and patients to assess their return on investment. Moreover, US prices are much higher than prices charged for the same medications in other countries.68 For example, an independent academic study presented at the 2015 European Cancer Congress found that those in the United States pay more than twice the price paid by Europeans for one class of cancer drugs.68

Costs for some generic and first-generation therapy drugs have also increased over time, despite lack of any further investment after widespread adoption. One recent analysis found that more than half of all retail generic drugs increased in price between 2013 and 2014.69 In August 2015, Turing Pharmaceuticals (New York, NY) stirred controversy when it purchased daraprim—a 62-year-old drug used to fight complications in patients whose immune systems have been weakened by HIV, pregnancy, or chemotherapy—and changed its price from $13.50 to $750 per pill—a 5,000% increase.70 The move generated outcry from Congress, along with several presidential candidates, and triggered the rapid development of an affordable alternative.71,72

In cancer care, creation of a market for biosimilar products was expected to help lower drug prices by increasing patient access to lower-cost biologic therapies. Economic analysis by the RAND Corporation (Santa Monica, CA) projected $44.2 billion in savings from 2014 to 2024 as a result of biosimilar products across all therapeutic classes but noted the savings could range from $13 billion to $66 billion, largely depending on the amount of competition.73 However, filgrastim-sndz, the first biosimilar approved in the United States, was introduced to market in 2015 at a 15% discount from the reference product—a decrease much smaller than expected from generic drugs.74 Although additional biosimilar products are in development, it is unclear how many biosimilar products will come to market and whether they will result in the dramatic price decreases brought by generic drugs. The price of a cancer drug may have little to do with its demonstrated efficacy—and newly approved cancer drugs that have not been shown to improve long-term survival continue to be marketed with high price tags.75

The price of many cancer drugs also forces patients and families to make difficult financial choices about whether to forego or curtail needed treatments. Some estimates suggest that 10% to 20% of patients with cancer may not take prescribed treatments because of the cost and that they are more likely to declare bankruptcy than those without cancer.63,76 Patients without health insurance are especially vulnerable to high drug costs, but costs can be unaffordable even for those with insurance when high deductibles transfer more of the cost of treatment to the insured. The result is that out-of-pocket drug expenses for patients with health insurance can run $25,000 or more per year.63

Not surprisingly, drug prices are unpalatable to patients and providers, and consumers are increasingly focused on escalating drug prices in the United States. A recent survey found that 24% of Americans say that they have a hard time paying for prescription drugs, 72% view the prices of prescription drugs as unreasonable, and 74% believe that Americans pay more for drugs than their European, Canadian, and Mexican counterparts.11 Concerned for their patients and for the solvency of the US cancer care system, physicians are becoming more vocal about the issue of drug costs. In October 2015, 118 oncologists published a commentary underscoring the need to prioritize high-value cancer care, proposing the following actions as possible solutions63:

Creating a post-FDA drug approval review mechanism to propose a fair price for new treatments based on the value to patients and heath care.

Allowing Medicare to negotiate drug prices.