Abstract

Objective:

To date, a paradox in the social epidemiology of alcohol use disorders (AUDs) remains unresolved: non-Hispanic Blacks experience higher socioeconomic disadvantage, stressor exposures, and individual stress—prominent AUD risk factors, yet have lower than expected AUD risk compared with non-Hispanic Whites. Religious involvement is associated with lower AUD risk. Non-Hispanic Blacks are highly religiously involved. Together, those facts may account for Black–White differences in AUD risk.

Method:

We used Wave 2 of the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC) (N = 26,784) to examine whether (a) religious involvement accounts for Black–White differences in AUD risk, and (b) race moderates the association between religious involvement and AUD. Religious involvement indicators were service attendance, social interaction, and subjective religiosity and spirituality. Twelve-month AUD prevalence as defined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, was the outcome. Covariates were age, education, income, marital status, and U.S.-born versus foreign-born nativity.

Results:

Blacks were significantly less likely than Whites to have an AUD (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] for men = 0.70, 95% CI [0.59, 0.83]; aOR for women = 0.71, 95% CI [0.57, 0.89]). An adjusted model with all three religious involvement indicators explained 17% of race differences among men (OR = 0.82) and 45% among women (OR = 1.03). There was no evidence that the association between religious involvement and AUD differed between Blacks and Whites.

Conclusions:

Religious service attendance, subjective religiosity, and spirituality account for a meaningful share of the Black–White differences in AUD. Future research is needed to conduct more fine-grained analyses of the aspects of religious involvement that are potentially protective against AUD, ideally differentiating between social norms associated with religious involvement, social support offered by religious participation, and deeply personal aspects of spirituality.

Alcohol use disorders (auds) are characterized by harmful or compulsive alcohol consumption despite causing harm to oneself or others (Dawson, 2011; Peterson et al., 2003). AUD accounts for 4% of deaths and 4.5% of the global burden of disease (World Health Organization, 2011). Approximately 30% of all adults in the United States will have an AUD during their lifetime (Hasin et al., 2007). The effects of alcohol consumption comprise the third leading preventable cause of death in the United States, attributed to approximately 88,000 deaths annually (National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, 2016). AUDs are also attributed to 3.5% of all cancer deaths (Nelson et al., 2013). AUD costs the economy more than $200 million annually in lost productivity (Bouchery et al., 2011).

There are two features of the social epidemiology of AUD that are not well understood (i.e., and that researchers view as “paradoxes”) (Herd, 1994; Zapolski et al., 2014). The first paradox is that, despite experiencing greater socioeconomic disadvantage, higher exposure to environmental stressors, and greater levels of individual stress (Boardman & Alexander, 2011; Roberts et al., 2011)—three prominent AUD risk factors (Pearlin & Radabaugh, 1976; Wilkinson & Marmot, 2003)—Blacks have lower 12-month and lifetime risks of AUD than Whites (Caetano et al., 2011; Grant et al., 2009; Hasin et al., 2007).

The second paradox is that, despite lower risks of AUD, the severity and health impact of AUD are worse for Blacks than for Whites (Caetano et al., 1998; Chartier & Caetano, 2010). For instance, in a clinical sample, the prevalence of hospital admissions for drinking and other outcomes among those with AUD was twice as high for Blacks as compared with Whites (Smothers et al., 2003). A recent population study found that at equivalent levels of alcohol consumption, Black men had higher mortality risk than White men (Jackson et al., 2015).

In this article, we investigate the first paradox—Black–White differences in experiencing an AUD during the preceding 12 months. Considering theory and evidence on racial inequalities in health broadly alongside the epidemiology of AUD among Blacks and Whites, we hypothesize the presence of race-specific protective factors for AUD. Religious involvement is one such protective factor (Levin, 1996), and AUD (Borders et al., 2010; Ghandour et al., 2009; Lambert et al., 2010) has been shown to be particularly salient among Blacks (Drevenstedt, 1998; Levin et al., 2005; Tabak & Mickelson, 2009). Whether religious involvement is a factor that can account for Black–White differences in AUD is not resolved.

Religious involvement and alcohol use disorders

The risk of alcohol and other drug abuse among religious people is 30%–40% less than among nonreligious people (Nelson, 2009). In a review of 86 studies that examined the association between levels of religious involvement and alcohol use and abuse, 76 studies (88%) reported significantly less alcohol abuse among religious persons (Koenig, 2001). Cultural systems of groups and societies shape the norms of alcohol consumption and the consequent likelihood of AUD through moral codes that govern patterns of alcohol consumption, the functions of alcohol consumption, who may consume alcohol, and what sanctions and consequences should be associated with alcohol consumption beyond the accepted norms (i.e., consumption that increases AUD) (Patrick, 1952). Religion is a cultural system/institution (Geertz, 2008; Hamilton, 1995) considered more influential than secular institutions on individuals’ alcohol consumption behavior. This is because theology/doctrines are “ideas which become legitimated by being religiously attached and interpreted, so that they influence the world views of large groups of people” (Spika & Bridges, 1992, p. 22).

Religion is organized into beliefs, lifestyles, rituals, and symbols that can be understood through institutional and internalized dimensions. Religious service attendance and social interaction with other religious adherents are institutionalized dimensions of religious involvement (Levin et al., 1995). Frequently attending services is associated with a lower likelihood of AUD among individuals through greater access to social support networks that help individuals cope with stress (Chatters et al., 2008), which is a risk factor for AUD. Frequent attendance may also increase exposure to religious norms about alcohol consumption. Although alcohol consumption norms vary within religious institutions/traditions (e.g., Protestantism) (Belcher, 2006; Linsky, 1965), all traditions stigmatize alcohol use to the extent that it increases risk of AUD (McGrath, 2004; Miller, 1998). Religiosity could promote a culture of moderation with regard to alcohol consumption (Mechanic, 1990). Therefore, “even in faith groups that allow alcohol consumption, adherents are taught to be self-disciplined … —an orientation that discourages consumption of alcohol” (Clarke et al., 1990, p. 206) that may result in AUD. Social interaction can increase the network of individuals with whom one can engage in pro-social religious activities and healthy behaviors (Ellison & Levin, 1998).

Religious involvement that is individually experienced and subjectively interpreted characterizes the internalized dimension. Spirituality is one common indicator of this dimension (Levin & Preston, 1987). Spirituality is associated with a lower likelihood of AUD in ways that are different from service attendance and social interaction. Because AUD is considered both a mental health disease and spiritual outcome (Nelson, 2009), individuals with high spirituality may have a lower likelihood of AUD through higher available spiritual and cognitive resources (Hathaway & Pargament, 1991; Pargament, 1990) to cope with and regulate emotions that arise from dealing with stressful situations (Nelson, 2009).

The role of religious involvement in race differences in alcohol use disorder

Variations in the levels of religious involvement and potential differences in strength of protection provided by religious involvement between Blacks and Whites may account for racial differences in AUD risk. First, Blacks have higher levels of religious involvement than Whites (Taylor et al., 1996), with the elderly and women often having the highest levels (Taylor et al., 1996; Thomas et al., 1994). Therefore, with all else equal, Blacks may have a lower likelihood of AUD simply because they are more religiously involved than Whites (Taylor et al., 2003). This reasoning has been called the “differential involvement perspective” (Krause, 2002). Our first hypothesis is that race differences in religious involvement account for Black–White differences in AUD. The differential impact perspective posits that the gains of religion on health vary across racial groups (Krause, 2005). Religious involvement has been central to preserving the cultural identity among Blacks in America and an organizing feature of their lives during key historical periods such as slavery and the Civil Rights Movement (Fallin, 2007; Lincoln & Mamiya, 1990). Religious involvement has consistently remained salient for Blacks beyond the Civil Rights era (Brown et al., 2015). Our second hypothesis, therefore, is that Black–White differences in AUD are attributable in part to the greater protective effect of religious involvement on AUD among Blacks than Whites.

The current study investigates the role of religious involvement in elucidating Blacks’ lower odds of 12-month AUD relative to Whites. This work extends the efforts of prior studies by examining, through two theoretical perspectives, the extent to which multiple dimensions of religious involvement attenuate Black–White differences among a population-based sample.

Method

Sample

Data were from Wave 2 of the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC), conducted in 2004–2005. NESARC is a population-based survey that captured health outcomes, behavioral factors, and psychiatric disorders among civilian non-institutionalized adults in the United States (National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, 2010). NESARC oversampled non-Hispanic blacks, Hispanics, and persons ages 18–24 years. Further details of sampling methodology and institutional review board approval are published (Grant & Dawson, 2006; Grant et al., 2009). Wave 2 consisted of 34,653 interviews with a response rate of 87%. The current sample was restricted to Black and White respondents only (n = 26,784). Study protocols for analysis with NESARC were also reviewed by Harvard (IRB15-0099) and determined nonhuman subjects research.

Measures

Alcohol use disorders.

AUDs were defined as the 12-month prevalence of alcohol abuse and/or dependence according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV; American Psychiatric Association, 1994). AUDs were measured by the Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule-DSM-IV (AUDADIS-IV). Test-retest reliability ranges for AUD using the AUDADIS are high (k = .76, SE = .05) (Grant et al., 1995; Hasin et al., 1997).

Religious involvement.

We used NESARC’s four religious involvement questions to derive three measures: religious service attendance, social interaction, and subjective religiosity and spirituality. Religious service attendance was ascertained with two questions. One question asked respondents whether they currently attend religious services at a church, mosque, synagogue, or other religious place. Responses were yes or no. The other question asked about frequency of service attendance. Responses ranged from 1 (once a year) to 5 (twice a week or more). Because frequency of service attendance is only recorded among those who attend services, we derived a new variable by adding another category: 0 (do not attend), 1 (once a year/a few times a year) (collapsed because of small cell size in once a year), 2 (one to three times a month), 3 (once a week), and 4 (twice a week or more). Social interaction corresponded to the question, “How many members of your religious group do you see or talk to socially every 2 weeks?” We recoded it into four equal groups that resulted in the following categories: 1 (≤8 members), 2 (9–16 members), 3 (17–24 members), and 4 (≥25 members). Subjective religiosity and spirituality was ascertained from the question, “How important is religious or spiritual beliefs in your daily life?” Responses ranged from 0 (not at all important) to 3 (very important) and were reverse coded to match the direction of religious service attendance.

Covariates

We included as controls in our analyses age (in years), educational attainment (0 [less than high school], 1 [completed high school], and 2 [some college or higher]), and personal income (0 [$0-$19,999], 1 [$20,000–$34,999], and 2 [$35,000 and higher]). We also included marital status (coded 0 [married and cohabitating], 1 [widowed, separated, and divorced], and 2 [never married]) and nativity (coded 0 [U.S. born] vs. 1 [foreign born]). To examine the specificity of the religious involvement association on AUD, we conducted supplementary analyses by additionally controlling for mood and anxiety disorders, substance use disorders, and nicotine dependence in the past year. These disorders are associated with both AUD and race, and may also influence or be influenced by religious participation (Chatters et al., 2008; Falk et al., 2006; Hasin et al., 2007; Huang et al., 2006).

Analytic strategy

Given gender (Maselko & Kubzansky, 2006) and racial differences in religious involvement (Levin et al., 1994) and gender differences in AUD (Wagner et al., 2002), all analyses were conducted separately for men and women. We conducted bivariate statistics for Black men (n = 2,326) and women (n = 4,261) and White men (n = 8,853) and women (n = 11,308). Unweighted sample sizes are reported with weighted percentages for categorical variables, and weighted means and standard errors are reported for continuous variables.

To examine the first hypothesis, we used multivariable logistic regression to estimate the risk of AUD for Blacks relative to Whites, adjusting for age, education, income, marital status, and nativity (Model 1). We then sequentially adjusted for service attendance, social interaction, and subjective religiosity and spirituality (Models 2–4). Next, we adjusted for all three religion variables simultaneously (Model 5). We examined how well each religious involvement model fit the data using goodness of fit (Archer et al., 2007).

Our second hypothesis is that the protective association between religious involvement and AUD is stronger for Blacks than for Whites. We derived race-specific estimates of the association between each religious involvement indicator and AUD as well as the three indicators simultaneously. Then, we tested for differences on the odds ratio (OR) scale between Blacks and Whites using the Adjusted Wald Test and confirmed the results by performing interaction contrasts (Schwartz, 2006) of race differences on the probability scale (i.e., margins) in pooled data.

Because NESARC is weighted to adjust for nonresponse at the household and individual levels, selection of one person per household, and oversampling of the demographic subgroups, all analyses were weighted and performed in STATA 13.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX) using the suite of “svy” and “subpop” survey commands. These procedures account for the complex survey design of NESARC and obtain correct standard errors when analyzing subgroups within a larger survey (Heeringa et al., 2010).

Results

Demographic characteristics of the sample, 12-month prevalence of AUD, and levels of religious involvement are presented in Table 1. Within gender, Blacks had lower prevalence of 12-month AUD than Whites. Black women had the highest proportion of attending services twice or more weekly (21%), followed by Black men (13.6%), White women (9.8%), and White men (7.9%). White men had the highest number of other religious members they interacted with socially (9.9), followed by Black men (8.1) (interquartile range: 1–10) (Table 1). Whites on average were older and had a higher proportion of persons who were married, who had incomes $35,000 and greater, and who had completed college than did Blacks.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics by race and gender

| Variable | Black men (n = 2,326) | Black women (n = 4,261) | White men (n = 8,853) | White women (n = 11,308) |

| DSM-IV alcohol use disorder, yes, n (%) | 276 (13.16) | 213 (05.44) | 1,357 (15.09) | 655 (05.63) |

| Religious involvement | ||||

| Religious service attendance, range (0–5), M (SE) | 1.56 (0.05) | 2.08 (0.05) | 1.21 (0.02) | 1.48 (0.02) |

| Do not attend, n (%) | 851 (38.29) | 1,030 (25.15) | 4,848 (53.19) | 5,171 (44.91) |

| Once a year/a few times a year, n (%) | 286 (12.56) | 354 (07.86) | 641 (07.36) | 780 (06.74) |

| One to three times a month, n (%) | 413 (16.81) | 885 (21.14) | 1,027 (11.90) | 1,520 (13.91) |

| Once a week, n (%) | 449 (18.70) | 1,049 (25.42) | 1,662 (19.63) | 2,746 (24.63) |

| Twice a week or more, n (%) | 319 (13.64) | 993 (21.02) | 654 (07.93) | 1,056 (09.81) |

| Social interaction, IQRa (1-10), M (SE) | 8.05 (0.48) | 7.0 (0.29) | 9.85 (0.37) | 7.35 (0.21) |

| ≤8 members, n (%) | 1,092 (75.75) | 2,493 (77.63) | 2,751 (68.75) | 4,535 (74.22) |

| 9–16 members, n (%) | 195 (12.48) | 432 (17.78) | 636 (16.65) | 863 (14.70) |

| 17–24 members, n (%) | 58 (04.19) | 1 10 (03.37) | 198 (05.05) | 276 (04.59) |

| ≥25 members, n (%) | 107 (06.58) | 176 (05.23) | 363 (09.55) | 369 (06.49) |

| Subjective religiosity and spirituality, range (1–4), M (SE) | 3.67 (0.02) | 3.80 (0.01) | 3.15 (0.02) | 3.48 (0.01) |

| Not important at all, n (%) | 43 (01.86) | 34 (00.92) | 746 (07.17) | 409 (03.40) |

| Not very important, n (%) | 69 (03.24) | 54 (01.60) | 1,178 (12.95) | 757 (06.57) |

| Somewhat important, n (%) | 486 (21.15) | 545 (13.59) | 3,118 (35.39) | 3,261 (28.95) |

| Very important, n (%) | 1,715 (73.75) | 3,618 (83.89) | 3,772 (43.95) | 6,831 (61.08) |

| Socioeconomic status Education, n (%) | ||||

| Less than high school | 479 (19.16) | 779 (16.40) | 877 (09.82) | 1,181 (10.29) |

| Completed high school | 711 (31.09) | 1,266 (29.34) | 2,382 (27.67) | 3,197 (28.71) |

| Some college or higher | 1,136 (49.75) | 2,216 (54.25) | 5,594 (62.51) | 6,930 (61.01) |

| Personal income, n (%) | ||||

| $0-$ 19,999 | 922 (39.74) | 2,315 (53.85) | 2,172 (24.21) | 5,841 (53.71) |

| $20,000–534,999 | 587 (25.95) | 1,057 (26.01) | 2,047 (23.31) | 2,531 (21.71) |

| ≥$35,000 | 817 (34.31) | 889 (20.13) | 4,634 (52.48) | 2,936 (24.58) |

| Covariates | ||||

| Age, M(SE) | 44.64 (0.43) | 46.03 (0.32) | 49.01 (0.22) | 50.73 (0.23) |

| Marital status, n (%) | ||||

| Married/cohabiting | 1,108 (51.89) | 1,268 (35.82) | 5,535 (69.45) | 6,221 (63.87) |

| Widowed/separated/divorced | 563 (17.04) | 1,677 (31.94) | 1,657 (13.13) | 3,653 (24.37) |

| Never married | 655 (31.07) | 1,316 (32.24) | 1,661 (17.43) | 1,434 (11.85) |

| Nativity, n (%) | ||||

| Born outside the United States | 197 (10.07) | 306 (09.52) | 376 (04.07) | 539 (04.63) |

Notes: DSM-IV = Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition.

Interquartile range (IQR) among the sample; n = unweighted sample size with weighted column %.

Table 2 presents the results of the analyses evaluating Hypothesis 1 among men, specifically that religious involvement would account for Black–White differences in AUD. First, the odds of AUD were 30% lower among Blackcompared with White men (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] = 0.70, 95% CI [0.59, 0.83]) adjusted for covariates (Model 1). Attending services twice a week or more relative to not attending (aOR = 0.27, 95% CI [0.17, 0.39], Model 2), socially interacting with 25 or more members relative to 8 and fewer (aOR = 0.55, 95% CI [0.35, 0.85], Model 3), and subjective religiosity and spirituality (aOR = 0.78, 95% CI [0.73, 0.84], Model 4) were associated with lower odds of 12-month AUD. Independently, each religious involvement indicator partially attenuated Black–White differences in odds of 12-month AUD. Simultaneous adjustment for all three indicators brought the adjusted OR for Black–White differences in AUD to 0.82 (95% CI [0.62, 1.07], Model 5). That model accounted for 17% of race differences in Model 1 (i.e., [aOR = {0.70 – 0.82} / 0.70] × 100).

Table 2.

Multivariable analyses of religious involvement and Black–White differences in DSM-IV alcohol use disorders, men

| Variable | Model 1 aOR [95% CI] | Model 2 aOR [95% CI] | Model 3 aOR [95% CI] | Model 4 aOR [95% CI] | Model 5d aOR [95% CI] |

| Race | |||||

| Blacka | 0.70*** [0.59, 0.83] | 0.77*** [0.65, 0.92] | 0.72* [0.55, 0.94] | 0.82* [0.68, 0.98] | 0.82 [0.62, 1.07] |

| Religious involvement | |||||

| Service attendanceb | 0.27*** [0.17, 0.39] | 0.40** [0.24, 0.68] | |||

| Social interactionc | 0.55** [0.35, 0.85] | 0.91 [0.55, 1.49] | |||

| Subjective religiosity and spirituality | 0.78*** [0.73, 0.84] | 0.68*** [0.57, 0.82] | |||

| Covariates | |||||

| Age | 0.96*** [0.96, 0.97] | 0.96*** [0.96, 0.97] | 0.96*** [0.95, 0.97] | 0.96*** [0.96, 0.97] | 0.96*** [0.96, 0.97] |

| Education | 0.92 [0.84, 1.01] | 0.93 [0.86, 1.01] | 0.94 [0.81, 1.09] | 0.92 [0.84, 1.01] | 0.94 [0.81, 1.09] |

| Income | 1.07* [1.01, 1.14] | 1.09* [1.02, 1.17] | 1.13* [1.00, 1.28] | 1.07* [1.00, 1.14] | 1.09 [0.96, 1.23] |

| Never marriede | 1.51*** [1.27, 1.80] | 1.37*** [1.15, 1.63] | 1.46** [1.10, 1.95] | 1.41*** [1.18, 1.68] | 1.39* [1.03, 1.86] |

| Born outside the United States | 0.60* [0.40, 0.90] | 0.61* [0.40, 0.92] | 0.54 [0.28, 1.02] | 0.58* [0.38, 0.88] | 0.53 [0.27, 1.03] |

| Goodness of fit | F(9, 57) = 35.46, | F(9, 57) = 31.48, | F(9, 57) = 20.36, | F(9, 57) = 31.28, | F(9, 57) = 20.16, |

| p < .0001 | p < .0001 | p < .0001 | p < .0001 | p < .0001 |

Notes: DSM-IV = Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition.

Reference group is non-Hispanic White;

the odds of attending services “twice per week” compared with the odds of “do not attend” (reference group);

the odds of “ ≥25 members” compared with the odds of “≤8 members”(reference group);

in analyses with multiple religion variables, the reference group for service attendance is “once/twice per year” because the sample for the other religious variables becomes limited to people who currently attend religious services;

reference group is married. aOR = adjusted odds ratio, CI = confidence interval.

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

In the supplemental analyses among men, race differences in AUD remained after adjusting for mood, anxiety, substance use disorders, and nicotine dependence in the past 12 months (Supplemental Table S1) (aOR = 0.75, CI [0.63, 0.89]). (Supplemental Tables S1 and S2 are presented as compendiums to this article online.) These differences in AUD were attenuated after we adjusted for religious involvement: adjustment for all measures of religious involvement accounted for 14% of race differences in AUD (vs. 17% in the primary analyses).

Table 3 shows the results among women. Blacks had 0.71 lower odds of AUD than Whites (95% CI [0.57, 0.89], Model 1). Religious service attendance (aOR = 0.27, 95% CI [0.16, 0.44], Model 2), social interaction (aOR = 0.22, 95% CI [0.10, 0.50], Model 3), and subjective religiosity and spirituality (aOR = 0.78, 95% CI [0.72, 0.85], Model 4) were associated with lower odds of 12-month AUD. Adjustment for any of the religious involvement indicators in Models 2–4 attenuated the OR for race. In Model 5, including all measures of religious involvement accounted for 45% of race differences (i.e., [aOR = {0.71 – 1.03} / 0.71] × 100).

Table 3.

Multivariable analyses of religious involvement and Black–White differences in DSM-IV alcohol use disorders, women

| Variable | Model 1 aOR [95% CI] | Model 2 aOR [95% CI] | Model 3 aOR [95% CI] | Model 4 aOR [95% CI] | Model 5d aOR [95% CI] |

| Race | |||||

| Blacka | 0.71** [0.57, 0.89] | 0.86 [0.69, 1.09] | 0.91 [0.68, 1.22] | 0.80 [0.64, 1.00] | 1.03 [0.75, 1.40] |

| Religious involvement | |||||

| Service attendanceb | 0.27*** [0.16, 0.44] | 0.39** [0.21, 0.71] | |||

| Social interactionc | 0.22*** [0.10, 0.50] | 0.31* [0.13, 0.75] | |||

| Subjective religiosity and spirituality | 0.78** [0.72, 0.85] | 0.76 [0.57, 1.01] | |||

| Covariates | |||||

| Age | 0.95*** [0.94, 0.95] | 0.95*** [0.94, 0.96] | 0.95*** [0.94, 0.96] | 0.95 [0.99, 1.17] | 0.96*** [0.94, 0.96] |

| Education | 1.22* [1.04, 1.43] | 1.20*** [1.05, 1.35] | 1.07 [0.85, 1.33] | 1.22* [1.04, 1.43] | 1.05 [0.85, 1.31] |

| Income | 1.09* [1.05, 1.43] | 1.07 [0.98, 1.18] | 1.16* [1.01, 1.33] | 1.08** [1.04, 1.23] | 1.13 [0.98, 1.30] |

| Never marriede | 1.71*** [1.38, 2.13] | 1.56*** [1.25, 1.94] | 1.26 [0.88, 1.80] | 1.65*** [1.33, 2.04] | 1.12 [0.95, 1.33] |

| Born outside the United States | 0.45** [0.28, 0.71] | 0.42** [0.26, 0.67] | 0.35* [0.15, 0.85] | 0.43** [0.27, 0.68] | 0.32* [0.13, 0.79] |

| Goodness of fit | F(9, 57) = 26.12, | F(9, 57) = 25.16, | F(9, 57)= 11.53, | F(9, 57) = 23.76, | F(9, 57) = 10.26, |

| p < .0001 | p < .0001 | p < .0001 | p < .0001 | p < .0001 |

Notes: DSM-IV = Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition.

Reference group is non-Hispanic White;

the odds of attending services “twice per week” compared with the odds of “do not attend” (reference group);

the odds of “ ≥25 members” compared with the odds of “≤8 members”(reference group);

in analyses with multiple religion variables, the reference group for service attendance is “once/twice per year” because the sample for the other religious variables becomes limited to people who currently attend religious services;

reference group is married. aOR = adjusted odds ratio; CI = confidence interval.

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

In the supplemental analyses adjusting for psychiatric and substance disorders (Supplemental Table S2), race differences in AUD among women were not quite statistically significant before introducing religious involvement into the analyses (aOR = 0.82, 95% CI [0.66, 1.02], Model 1). However, the OR for Black–White differences in the supplemental analyses was attenuated by 28% after adjusting (vs. 45% in the primary analyses).

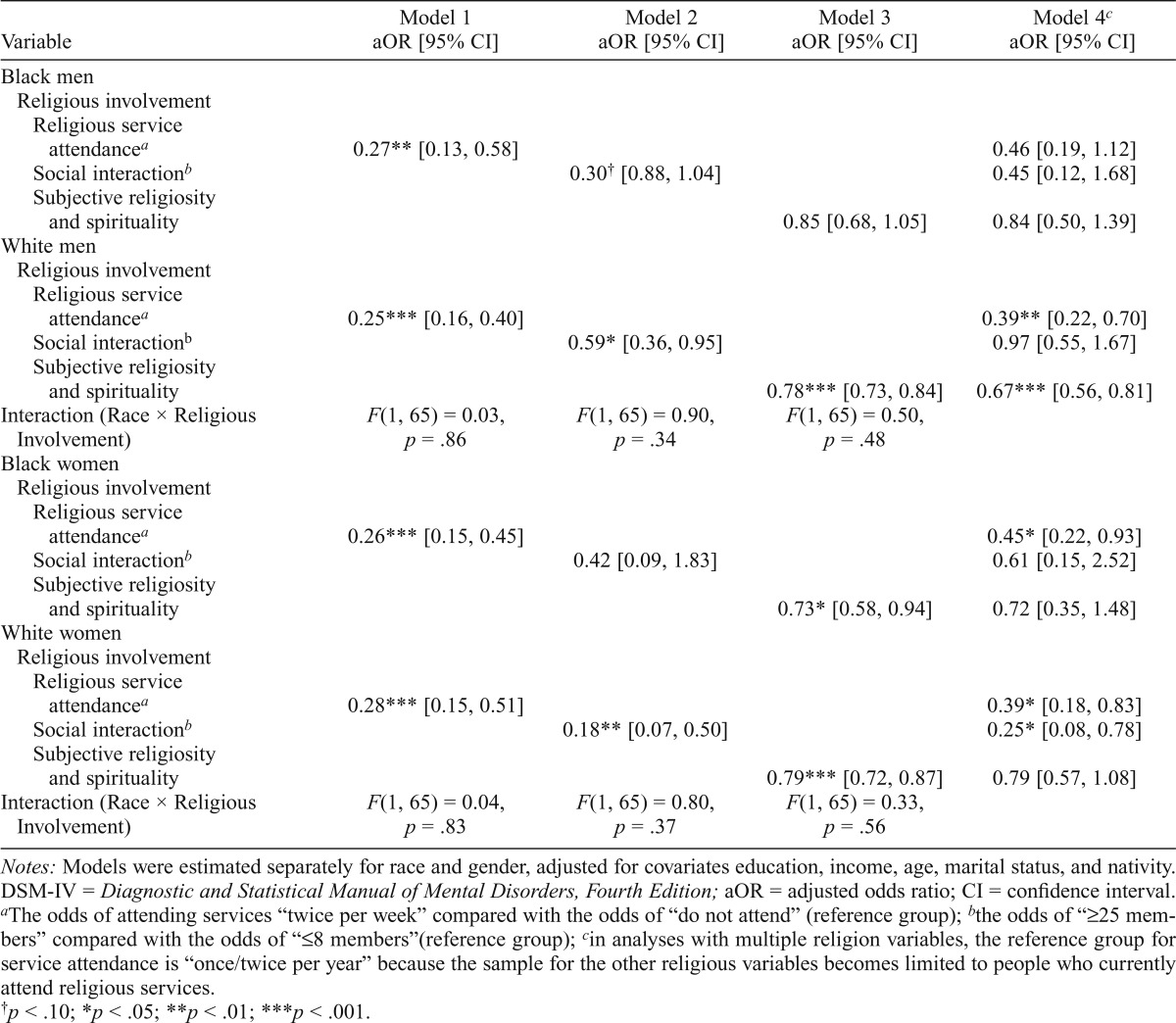

Table 4 shows that our second hypothesis was not supported. The aOR for the association between religious involvement and AUD did not differ significantly between Blacks and Whites.

Table 4.

Association between religious involvement and DSM-IV alcohol use disorders by race and gender

| Variable | Model 1 aOR [95% CI] | Model 2 aOR [95% CI] | Model 3 aOR [95% CI] | Model 4c aOR [95% CI] |

| Black men | ||||

| Religious involvement | ||||

| Religious service attendancea | 0.27** [0.13, 0.58] | 0.46 [0.19, 1.12] | ||

| Social interactionb | 0.30† [0.88, 1.04] | 0.45 [0.12, 1.68] | ||

| Subjective religiosity and spirituality | 0.85 [0.68, 1.05] | 0.84 [0.50, 1.39] | ||

| White men | ||||

| Religious involvement | ||||

| Religious service attendancea | 0.25*** [0.16, 0.40] | 0.39** [0.22, 0.70] | ||

| Social interactionb | 0.59* [0.36, 0.95] | 0.97 [0.55, 1.67] | ||

| Subjective religiosity and spirituality | 0.78*** [0.73, 0.84] | 0.67*** [0.56, 0.81] | ||

| Interaction (Race × Religious Involvement) | F(1, 65) = 0.03, p = .86 | F(1, 65) = 0.90, p = .34 | F(1, 65) = 0.50, p = .48 | |

| Black women | ||||

| Religious involvement | ||||

| Religious service attendancea | 0.26*** [0.15, 0.45] | 0.45* [0.22, 0.93] | ||

| Social interactionb | 0.42 [0.09, 1.83] | 0.61 [0.15, 2.52] | ||

| Subjective religiosity and spirituality | 0.73* [0.58, 0.94] | 0.72 [0.35, 1.48] | ||

| White women | ||||

| Religious involvement | ||||

| Religious service attendancea | 0.28*** [0.15, 0.51] | 0.39* [0.18, 0.83] | ||

| Social interactionb | 0.18** [0.07, 0.50] | 0.25* [0.08, 0.78] | ||

| Subjective religiosity and spirituality | 0.79*** [0.72, 0.87] | 0.79 [0.57, 1.08] | ||

| Interaction (Race × Religious Involvement) | F(1, 65) = 0.04, p = .83 | F(1, 65) = 0.80, p = .37 | F(1, 65) = 0.33, p = .56 |

Notes: Models were estimated separately for race and gender, adjusted for covariates education, income, age, marital status, and nativity. DSM-IV = Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition; aOR = adjusted odds ratio; CI = confidence interval.

The odds of attending services “twice per week” compared with the odds of “do not attend” (reference group);

the odds of “≥25 members” compared with the odds of “≤8 members”(reference group);

in analyses with multiple religion variables, the reference group for service attendance is “once/twice per year” because the sample for the other religious variables becomes limited to people who currently attend religious services.

p < .10;

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

Discussion

We extended prior research (Herd, 1994, 1997) by investigating the role of multiple indicators of religious involvement in the Black–White AUD paradox. We found that religious involvement accounted for part of the association between race and AUD. Our results are consistent with findings on race differences in alcohol use and abstinence among adolescents and abstinence from alcohol use, which showed that controlling for religiosity substantially reduces race differences (Wallace et al., 2003). In our study, among men, the religious involvement indicators combined accounted for about one fifth of the lower odds of AUD among Blacks. Among women, religious involvement accounted for nearly half of the lower odds of AUD among Blacks. These gender differences could reflect the different quality of social support Black women receive from religious involvement in relation to men (van Olphen et al., 2003).

The results of supplemental analyses adjusting for co-occurring psychiatric and substance disorders suggest that the role of religious involvement in accounting for Black–White differences in AUD is potentially independent of other forms of psychopathology. However, it is important to note that the NESARC cannot discern the temporality between episodes of AUD and these other disorders during the past year. To the extent that religious involvement is associated with a lower odds of other disorders, which in turn have a protective effect on AUD, these analyses are “overcontrolling” for factors in the causal pathway. These models are also misspecified to the extent that other comorbidities occur after AUD. Evidence from prospective studies indicates that psychiatric disorders often precede AUD (e.g., anxiety leading to alcohol problems) (Buckner & Schmidt, 2009), although the association can also be bi-directional (e.g., nicotine dependence preceding AUD in short term but following AUD in the long term) (Jackson et al., 2003).

Our study has the following limitations. Religious denomination was not available in NESARC, which could potentially affect associations between religious involvement and attenuation of Black–White differences. For instance, one study showed that a higher proportion of predominantly Black denominations (i.e., churches in which >80% of parishioners are Black) proscribe alcohol use and impose negative sanctions for alcohol use (e.g., excluding members from participating in choir or other positions) than predominantly White denominations (Ransome, 2014). In contrast, Krause reported that religious denomination did not moderate the association between religious meaning and alcohol abstinence, concluding that “people who find meaning in religion are more likely to avoid the use of alcohol regardless of whether they affiliate with a fundamentalist congregation” (Krause, 2003, p. 527).

Religious involvement was only measured in Wave 2 of NESARC; therefore, we could not establish its temporality with AUD. However, results from several prospective studies suggest that religious involvement is a predictor of later substance use disorders (Good & Willoughby, 2011; Idler & Kasl, 1997; Lambert et al., 2010; Miller et al., 2012). For example, one prospective study showed that among persons with no AUD at baseline, a higher frequency of organized religious attendance was associated with a lower risk of 6-month AUD incidence (Borders et al., 2010). Finally, it is important to consider the extent of causal inferences that can be sustained by our study design. It is unlikely that there were unmeasured confounders of the association between race and AUD per se (VanderWeele & Robinson, 2014). However, our analyses cannot sustain inferences regarding causal mediation (i.e., that race differences in AUD were caused by religious involvement). Race differences could be attributable to other cultural factors not measured by NESARC that are associated with religious involvement and also predict AUD (Brown et al., 2001). Therefore, our conclusions are in reference to the observational association between race and AUD. Both religious involvement and AUD were measured in adulthood, but there could be protective factors in childhood (Breslau et al., 2006) that shape religiosity in adulthood that in turn affect current AUD. There could also be race differences in childhood influences (e.g., parental religious involvement) that are related to religiosity in adulthood (Perkins, 1987) and subsequently manifest as differences in AUD.

Some strengths of this study include examining multiple indicators of religious involvement separately in a nationally representative sample of Black and White men and women. Although we did not consider potential ethnic heterogeneity among Blacks (or Whites), our key findings may have been similar. For instance, Caribbean-born Blacks—a major Black ethnic group—have slightly lower rates of AUD than U.S.- born Blacks (Broman et al., 2008) but almost no differences in religious involvement across a range of indicators (Taylor et al., 2011). Both Caribbean-born and U.S.-born Blacks had lower lifetime risk of AUD compared with Whites (Gibbs et al., 2013).

The study also used a reliable measure of AUDs, which has been validated across race and ethnic groups in diagnosing AUD (Volk et al., 1997).

Conclusion

This study advances our understanding of the social epidemiology of AUD. We show that core religious involvement indicators, including religious service attendance and subjective religiosity and spirituality, account for a meaningful share of the Black–White difference in AUD. Future research is needed to conduct more fine-grained analyses of the aspects of religious involvement that are potentially protective against AUD, ideally differentiating between social norms associated with religious involvement, social support offered by religious participation, and deeply personal aspects of spirituality.

Footnotes

This work was supported in part by the Alonzo Smythe Yerby Fellow-ship at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, and the Intramural Research Program of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: Author; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Archer K. J., Lemeshow S., Hosmer D. W. Goodness-of-fit tests for logistic regression models when data are collected using a complex sampling design. Computational Statistics & Data Analysis. 2007;51:4450–4464. doi:10.1016/j.csda.2006.07.006. [Google Scholar]

- Belcher J. R. Protestantism and alcoholism. Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly. 2006;24:21–32. doi:10.1300/J020v24n01_03. [Google Scholar]

- Boardman J. D., Alexander K. B. Stress trajectories, health behaviors, and the mental health of black and white young adults. Social Science & Medicine. 2011;72:1659–1666. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.03.024. doi:10.1016/j. socscimed.2011.03.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borders T. F., Curran G. M., Mattox R., Booth B. M. Religiousness among at-risk drinkers: Is it prospectively associated with the development or maintenance of an alcohol-use disorder? Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2010;71:136–142. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2010.71.136. doi:10.15288/jsad.2010.71.136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouchery E. E., Harwood H. J., Sacks J. J., Simon C. J., Brewer R. D. Economic costs of excessive alcohol consumption in the U.S., 2006. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2011;41:516–524. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.06.045. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2011.06.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslau J., Aguilar-Gaxiola S., Kendler K. S., Su M., Williams D., Kessler R. C. Specifying race-ethnic differences in risk for psychiatric disorder in a USA national sample. Psychological Medicine. 2006;36:57–68. doi: 10.1017/S0033291705006161. doi:10.1017/S0033291705006161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broman C. L., Neighbors H. W., Delva J., Torres M., Jackson J. S. Prevalence of substance use disorders among African Americans and Caribbean Blacks in the National Survey of American Life. American Journal of Public Health. 2008;98:1107–1114. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.100727. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2006.100727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown R. K., Taylor R. J., Chatters L. M. Race/ethnic and social-demographic correlates of religious non-involvement in America: Findings from three national surveys. Journal of Black Studies. 2015;46:335–362. doi:10.1177/0021934715573168. [Google Scholar]

- Brown T. L., Parks G. S., Zimmerman R. S., Phillips C. M. The role of religion in predicting adolescent alcohol use and problem drinking. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2001;62:696–705. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2001.62.696. doi:10.15288/jsa.2001.62.696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner J. D., Schmidt N. B. Understanding social anxiety as a risk for alcohol use disorders: Fear of scrutiny, not social interaction fears, prospectively predicts alcohol use disorders. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2009;43:477–483. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2008.04.012. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2008.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caetano R., Baruah J., Chartier K. G. Ten-year trends (1992 to 2002) in sociodemographic predictors and indicators of alcohol abuse and dependence among whites, blacks, and Hispanics in the United States. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2011;35:1458–1466. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01482.x. doi:10.1111/j.15300277.2011.01482.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caetano R., Clark C. L., Tam T. Alcohol consumption among racial/ethnic minorities: Theory and research. Alcohol Health and Research World. 1998;22:233–241. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chartier K., Caetano R. Ethnicity and health disparities in alcohol research. Alcohol Research & Health. 2010;33:152–160. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatters L. M., Bullard K. M., Taylor R. J., Woodward A. T., Neighbors H. W., Jackson J. S. Religious participation and DSM-IV disorders among older African Americans: Findings from the National Survey of American Life. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2008;16:957–965. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181898081. doi:10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181898081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke L., Beeghley L., Cochran J. K. Religiosity, social class, and alcohol use: An application of reference group theory. Sociological Perspectives. 1990;33:201–218. doi:10.2307/1389043. [Google Scholar]

- Dawson D. A. Defining risk drinking. Alcohol Research & Health. 2011;34:144–156. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drevenstedt G. L. Race and ethnic differences in the effects of religious attendance on subjective health. Review of Religious Research. 1998;39:245–263. doi:10.2307/3512591. [Google Scholar]

- Ellison C. G., Levin J. S. The religion-health connection: Evidence, theory, and future directions. Health Education & Behavior. 1998;25:700–720. doi: 10.1177/109019819802500603. doi:10.1177/109019819802500603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falk D. E., Yi H. Y., Hiller-Sturmhofel S. An epidemiologic analysis of co-occurring alcohol and tobacco use and disorders: Findings from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Alcohol Research & Health. 2006;29:162–171. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fallin W. Uplifting the people: Three centuries of black Baptists in Alabama. Tuscaloosa, AL: University of Alabama Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Geertz C. Religion as a cultural system. In: Lambek M., editor. A reader in the anthropology of religion. 2nd edition. Malden, MA: Blackwell Pub Ldt; 2008. pp. 57–76. [Google Scholar]

- Ghandour L. A., Karam E. G., Maalouf W. E. Lifetime alcohol use, abuse and dependence among university students in Lebanon: Exploring the role of religiosity in different religious faiths. Addiction. 2009;104:940–948. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02575.x. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02575.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs T. A., Okuda M., Oquendo M. A., Lawson W. B., Wang S., Thomas Y. F., Blanco C. Mental health of African Americans and Caribbean blacks in the United States: Results from the National Epidemiological Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. American Journal of Public Health. 2013;103:330–338. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300891. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2012.300891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Good M., Willoughby T. Evaluating the direction of effects in the relationship between religious versus non-religious activities, academic success, and substance use. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2011;40:680–693. doi: 10.1007/s10964-010-9581-y. doi:10.1007/s10964-010-9581-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant B. F., Dawson D. A. Introduction to the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Alcohol Health and Research World. 2006;29:74–78. [Google Scholar]

- Grant B. F., Goldstein R. B., Chou S. P., Huang B., Stinson F. S., Dawson D. A., Compton W. M. Sociodemographic and psychopathologic predictors of first incidence of DSM-IV substance use, mood and anxiety disorders: Results from the Wave 2 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Molecular Psychiatry. 2009;14:1051–1066. doi: 10.1038/mp.2008.41. doi:10.1038/mp.2008.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant B. F., Harford T. C., Dawson D. A., Chou P. S., Pickering R. P. The Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule (AUDADIS): Reliability of alcohol and drug modules in a general population sample. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1995;39:37–44. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(95)01134-k. doi:10.1016/03768716(95)01134-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton M. The sociology of religion: Theoretical and comparative perspectives. 2nd ed. London, UK: Routledge; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Hasin D., Carpenter K. M., McCloud S., Smith M., Grant B. F. The Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule (AUDADIS): Reliability of alcohol and drug modules in a clinical sample. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1997;44:133–141. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(97)01332-x. doi:10.1016/S0376-8716(97)01332-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin D. S., Stinson F. S., Ogburn E., Grant B. F. Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence in the United States: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2007;64:830–842. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.7.830. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.64.7.830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hathaway W. L., Pargament K. I. The religious dimensions of coping: Implications for prevention and promotion. Prevention in Human Services. 1991;9:65–92. doi:10.1300/J293v09n02_04. [Google Scholar]

- Heeringa S. G., West B. T., Berglund P. A. Applied survey data analysis. Boca Raton, FL: Chapman & Hall/CRC; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Herd D. Predicting drinking problems among black and white men: Results from a national survey. Journal ofStudies on Alcohol. 1994;55:61–71. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1994.55.61. doi:10.15288/jsa.1994.55.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herd D. Racial differences in women’s drinking norms and drinking patterns: A national study. Journal of Substance Use. 1997;9:137–149. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(97)90012-2. doi:10.1016/S0899-3289(97)90012-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang B., Grant B. F., Dawson D. A., Stinson F. S., Chou S. P., Saha T. D., Pickering R. P. Race-ethnicity and the prevalence and co-occurrence of Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, alcohol and drug use disorders and axis I and II disorders: United States, 2001 to 2002. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2006;47:252–257. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2005.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Idler E. L., Kasl S. V. Religion among disabled and nondisabled persons. II: Attendance at religious services as a predictor of the course of disability. Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 1997;52B:S306–S316. doi: 10.1093/geronb/52b.6.s306. doi:10.1093/geronb/52B.6.S306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson C. L., Hu F. B., Kawachi I., Williams D. R., Mukamal K. J., Rimm E. B. Black–White differences in the relationship between alcohol drinking patterns and mortality among US men and women. American Journal of Public Health, 105, Supplement. 2015;3:S534–S543. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302615. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2015.302615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson K. M., Sher K. J., Wood P. K., Bucholz K. K. Alcohol and tobacco use disorders in a general population: Short-term and long-term associations from the St. Louis epidemiological catchment area study. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2003;71:239–253. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(03)00136-4. doi:10.1016/S0376-8716(03)00136-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig H. G. Religion and medicine. II: Religion, mental health, and related behaviors. International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine. 2001;31:97–109. doi: 10.2190/BK1B-18TR-X1NN-36GG. doi:10.2190/BK1B-18TR-X1NN-36GG. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause N. Church-based social support and health in old age: Exploring variations by race. Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2002;57B:S332–S347. doi: 10.1093/geronb/57.6.s332. doi:10.1093/geronb/57.6.S332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause N. Race, religion, and abstinence from alcohol in late life. Journal of Aging and Health. 2003;15:508–533. doi: 10.1177/0898264303253505. doi:10.1177/0898264303253505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause N. Aging. In: Ebaugh H. R., editor. Handbook of religion and social institutions. NewYork, NY: Springer Science and Business Media; 2005. pp. 139–163. [Google Scholar]

- Lambert N. M., Fincham F. D., Marks L. D., Stillman T. F. Invocations and intoxication: Does prayer decrease alcohol consumption? Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2010;24:209–219. doi: 10.1037/a0018746. doi:10.1037/a0018746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin J., Chatters L. M., Taylor R. J. Religion, health and medicine in African Americans: Implications for physicians. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2005;97:237–249. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin J. S. How religion influences morbidity and health: Reflections on natural history, salutogenesis and host resistance. Social Science & Medicine. 1996;43:849–864. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(96)00150-5. doi:10.1016/0277-9536(96)00150-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin J. S., Preston L. S. Is there a religious factor in health? Journal of Religion and Health. 1987;26:9–36. doi: 10.1007/BF01533291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin J. S., Taylor R. J., Chatters L. M. Race and gender differences in religiosity among older adults: Findings from four national surveys. Journal of Gerontology. 1994;49:S137–S145. doi: 10.1093/geronj/49.3.s137. doi:10.1093/geronj/49.3.S137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin J. S., Taylor R. J., Chatters L. M. A multidimensional measure of religious involvement for African Americans. Sociological Quarterly. 1995;36:157–173. doi:10.1111/j.1533-8525.1995.tb02325.x. [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln E. C., Mamiya L. H. The Black Church in the African American experience. Durham, NC: Duke University Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Linsky A. S. Religious differences in lay attitudes and knowledge on alcoholism and its treatment. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 1965;5:41–50. doi:10.2307/1384253. [Google Scholar]

- Maselko J., Kubzansky L. D. Gender differences in religious practices, spiritual experiences and health: Results from the US General Social Survey. Social Science & Medicine. 2006;62:2848–2860. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.11.008. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrath J. A glutton and a drunkard: What would Jesus drink? In: Robertson C. K., editor. Religion and alcohol: Sobering thoughts. New York, NY: Pete; 2004. pp. 11–44. r Lang Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Mechanic D. Promoting health. Society. 1990;27:16–22. [Google Scholar]

- Miller L., Wickramaratne P., Gameroff M. J., Sage M., Tenke C. E., Weissman M. M. Religiosity and major depression in adults at high risk: A ten-year prospective study. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2012;169:89–94. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.10121823. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.10121823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller W. R. Researching the spiritual dimensions of alcohol and other drug problems. Addiction. 1998;93:979–990. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1998.9379793.x. doi:10.1046/j.1360-0443.1998.9379793.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Alcohol use and alcohol use disorders in the United States, a 3-year follow-up: Main findings from the 2004-2005 Wave 2 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC) 2010. U.S. Alcohol Epidemiologic Data Reference Manual (Vol. 8, No. 2). Bethesda, MD: Author. Retrieved from http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/NESARC_DRM2/NESARC2DRM.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Alcohol facts and statistics. Alcohol and your health. 2016. Retrieved from http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/AlcoholFacts&Stats/AlcoholFacts&Stats.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson D. E., Jarman D. W., Rehm J., Greenfield T. K., Rey G., Kerr W. C., Naimi T. S. Alcohol-attributable cancer deaths and years of potential life lost in the United States. American Journal of Public Health. 2013;103:641–648. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301199. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2012.301199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson J. M. Religion, spirituality, and mental health. In: Nelson J. M., editor. Psychology, religion and spirituality. New York, NY: Springer Science and Business Media LLC; 2009. pp. 347–390. [Google Scholar]

- Pargament K. I. God help me: Toward a theoretical framework of coping for the psychology of religion. Research in the Social Scientific Study of Religion. 1990;3:195–224. [Google Scholar]

- Patrick C. H. Alcohol, culture, and society. Durham, NC: Duke University Press; 1952. [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin L. I., Radabaugh C. W. Economic strains and the coping functions of alcohol. American Journal of Sociology. 1976;82:652–663. doi: 10.1086/226357. doi:10.1086/226357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins H. W. Parental religion and alcohol use problems as intergenerational predictors of problem drinking among college youth. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 1987;26:340–357. doi:10.2307/1386436. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson V. J., Nisenholz B., Robinson G. A nation under the influence: America’s addiction to alcohol. New York, NY: Pearson Education; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Ransome Y. Can religion and socioeconomic status explain Black–White differences in alcohol abuse? (DrPH doctoral dissertation). Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health; New York, NY: 2014. 3642257. [Google Scholar]

- Rehm J., Dawson D., Frick U., Gmel G., Roerecke M., Shield K. D., Grant B. Burden of disease associated with alcohol use disorders in the United States. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2014;38:1068–1077. doi: 10.1111/acer.12331. doi:10.1111/acer.12331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts A. L., Gilman S. E., Breslau J., Breslau N., Koenen K. C. Race/ethnic differences in exposure to traumatic events, development of post-traumatic stress disorder, and treatment-seeking for post-traumatic stress disorder in the United States. Psychological Medicine. 2011;41:71–83. doi: 10.1017/S0033291710000401. doi:10.1017/S0033291710000401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz S. Modern epidemiologic approaches to interaction: Applications to the study of genetic interactions. In: Hernandez L. M., Blazer D. G., editors. Genes, behavior, and the social environment: Moving beyond the nature/nurture debate. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2006. pp. 310–336. [Google Scholar]

- Smothers B. A., Yahr H. T., Sinclair M. D. Prevalence of current DSM-IV alcohol use disorders in short-stay, general hospital admissions, United States, 1994. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2003;163:713–719. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.6.713. doi:10.1001/archinte.163.6.713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spika B., Bridges R. A. Religious perspectives on prevention: The role of theology. In: Pargament K. I., Maton K. I., Hess R. E., editors. Religion and prevention in mental health: Research, vision, and action. NewYork, NY: Haworth Press; 1992. pp. 19–36. [Google Scholar]

- Tabak M. A., Mickelson K. D. Religious service attendance and distress: The moderating role of stressful life events and race/ethnicity. Sociology of Religion. 2009;70:49–64. doi:10.1093/socrel/srp001. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor R. J., Chatters L. M., Jayakody R., Levin J. S. Black and white differences in religious participation: A multisample comparison. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 1996;35:403–410. doi:10.2307/1386415. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor R. J., Chatters L. M., Joe S. Non-organizational religious participation, subjective religiosity, and spirituality among older African Americans and Black Caribbeans. Journal of Religion and Health. 2011;50:623–645. doi: 10.1007/s10943-009-9292-4. doi:10.1007/s10943–009-9292-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor R. J., Chatters L. M., Levin J. Religion in the lives of African Americans: Social, psychological, and health perspectives. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas S. B., Quinn S. C., Billingsley A., Caldwell C. The characteristics of northern black churches with community health outreach programs. American Journal of Public Health. 1994;84:575–579. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.4.575. doi:10.2105/AJPH.84.4.575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Olphen J., Schulz A., Israel B., Chatters L., Klem L., Parker E., Williams D. Religious involvement, social support, and health among African-American women on the east side of Detroit. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2003;18:549–557. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.21031.x. doi:10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.21031.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VanderWeele T. J., Robinson W. R. On the causal interpretation of race in regressions adjusting for confounding and mediating variables. Epidemiology. 2014;25:473–484. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000105. doi:10.1097/EDE.0000000000000105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volk R. J., Steinbauer J. R., Cantor S. B., Holzer C. E., III The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) as a screen for at-risk drinking in primary care patients of different racial/ethnic backgrounds. Addiction. 1997;92:197–206. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.1997. tb03652.x. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner E. F., Lloyd D. A., Gil A. G. Racial/ethnic and gender differences in the incidence and onset age of DSM-IV alcohol use disorder symptoms among adolescents. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;63:609–619. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2002.63.609. doi:10.15288/jsa.2002.63.609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace J. M., Jr., Brown T. N., Bachman J. G., LaVeist T. A. The influence of race and religion on abstinence from alcohol, cigarettes and marijuana among adolescents. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2003;64:843–848. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.843. doi:10.15288/jsa.2003.64.843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson R. G., Marmot M. G. Social determinants of health: The solid facts. 2nd ed. Copenhagen, Denmark: World Health Organization; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Global status report on alcohol and health. Geneva, Switzerland: Author; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Zapolski T. C., Pedersen S. L., McCarthy D. M., Smith G. T. Less drinking, yet more problems: Understanding African American drinking and related problems. Psychological Bulletin. 2014;140:188–223. doi: 10.1037/a0032113. doi:10.1037/a0032113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]