Abstract

The interaction between α-synuclein (αS) protein and lipid membranes is key to its role in synaptic vesicle homeostasis and plays a role in initiating fibril formation, which is implicated in Parkinson’s disease. The natural state of αS inside the cell is generally believed to be intrinsically disordered, but chemical cross-linking experiments provided evidence of a tetrameric arrangement, which was reported to be rich in α-helical secondary structure based on circular dichroism (CD). Cross-linking relies on chemical modification of the protein’s Lys Cε amino groups, commonly by glutaraldehyde, or by disuccinimidyl glutarate (DSG), with the latter agent preferred for cellular assays. We used ultra-high-resolution homonuclear decoupled nuclear magnetic resonance experiments to probe the reactivity of the 15 αS Lys residues toward N-succinimidyl acetate, effectively half the DSG cross-linker, which results in acetylation of Lys. The intensities of both side chain and backbone amide signals of acetylated Lys residues provide direct information about the reactivity, showing a difference of a factor of 2.5 between the most reactive (K6) and the least reactive (K102) residue. The presence of phospholipid vesicles decreases reactivity of most Lys residues by up to an order of magnitude at high lipid:protein stoichiometries (500:1), but only weakly at low ratios. The decrease in Lys reactivity is found to be impacted by lipid composition, even for vesicles that yield similar αS CD signatures. Our data provide new insight into the αS–bilayer interaction, including the pivotal state in which the available lipid surface is limited. Protection of Lys Cε amino groups by αS–bilayer interaction will strongly impact quantitative interpretation of DSG cross-linking experiments.

Use of cross-linking agents of variable length, in combination with mass spectrometry, can provide valuable structural information about the spatial separation between cross-linked residues, either in protein–protein complexes or for individual proteins.1 At a more qualitative level, cross-linking is one of the most widely used technologies for probing protein–protein interactions. Many of the most common bifunctional cross-linking reagents, including the widely used glutaraldehyde cross-linker, target the side chain Cε amino groups of Lys residues.2 For improved cellular uptake, DSG was previously chosen to cross-link cytosolic α-synuclein (αS, 14.5 kDa monomer) in a range of different cell types, including primary neurons, human erythroleukemia cells, and neuroblastoma cells overexpressing αS.3 The observation of a major band at ∼60 kDa and weaker bands at ∼80 and ∼100 kDa provided support for earlier conclusions by the same group that the protein natively exists mostly as a folded tetramer inside the cytosol, and that the unfolded, intrinsic disordered protein (IDP) state seen in all prior work4 results from the harsh purification protocols.5,6 Remarkably, however, even cell lysis was found to destabilize the tetrameric state in the cross-linking studies, with partial recovery of the tetramer if the αS concentration was kept high.3 The presence of a cofactor, putatively a small lipid, is now proposed to be responsible for the tetrameric state.7 On the other hand, an NMR and pulsed EPR study of αS, introduced into a set of five different types of mammalian cells by electroporation, showed that the protein remained highly disordered inside these cells,8 which remained healthy as judged by their intact enzymatic machinery, including N-terminal acetylation of αS and enzymatic reduction of both the R and S isomers of oxidized Met residues in αS.9 Importantly, the NMR results could quantitatively account for nearly all of the αS loaded into these cells, thereby excluding the possibility that the majority was converted into a folded tetrameric species.

Distinct, mostly even-numbered oligomeric assemblies of αS were also identified in vitro by glutaraldehyde cross-linking in the presence of negatively charged liposomes,10 and a recent study details the observation of nanodisc-like particles, containing 8–10 synuclein molecules surrounding a lipid disc, qualitatively similar to observations made by EPR spectroscopy,11 with some evidence that such discs may exist in vivo, too.12

Interestingly, in vitro, the NMR signals of the ∼100 N-terminal residues of αS are rendered invisible in the presence of even very small amounts of lipid vesicles,13,14 and at higher lipid:protein stoichiometries, a strong α-helical CD signal indicates that the protein adopts an α-helical state when it is bound to membranes,13,15−18 a conclusion also supported by NMR and pulsed EPR experiments.11,18,19

When Burre et al. performed cross-linking experiments on a brain homogenate, formation of higher-order covalently linked oligomers, containing eight or more αS subunits, was observed, but no oligomerization was seen for the cytosolic fraction, lacking membranes.10 Similarly, covalently linked oligomers were obtained when cross-linking experiments were performed with a fresh murine brain homogenate, containing membranes.10

It is well recognized that chemical cross-linking experiments need to be carefully tuned with respect to the amount of cross-linker used. An overly high concentration can result in large networks of covalently linked proteins, effectively forming a gel, which is used for tissue fixation. Insufficient amounts of cross-linker will result in the natural decay of the cross-linking agent prior to the formation of covalent linkages. Moreover, for intrinsically disordered proteins, such as αS, the pairwise distance between the reactive Cε amino groups of Lys residues is highly time-dependent and generally will sample many distances shorter than the length of the cross-linker, meaning that formation of intramolecular cross-links in the disordered state is highly favored over intermolecular linkages. In fact, with the radius of hydration of αS being ∼27 Å,14,20 the effective local concentration of the 14 remaining Lys Cε amino groups after a single Lys has reacted with the cross-linker, seen by the second reactive site of the cross-linking agent, is ∼150 mM, i.e., greatly favoring intramolecular over intermolecular linkages. In the presence of membranes, cross-linking can occur between protein Lys Cε amino groups and phospholipids, in particular those containing amino groups (e.g., lipids with phosphoethanolamine or phosphatidylserine headgroups) that can interfere with the intended measurement.

The study presented here aimed to evaluate the reactivity of the αS Lys residues with N-succinimidyl acetate, a molecule that comprises effectively half the widely used DSG cross-linker (Figure 1). By using half the cross-linker, reaction of N-succinimidyl acetate with a given Lys amino group results in a unique product, acetylation of the side chain, rather than a distribution of 14 different intraprotein cross-links plus possible interprotein linkages, thereby simplifying the analysis. Acetylation of Lys residues is a modification that, at least in principle, can easily be followed by monitoring the perturbation of the backbone chemical shift of the modified Lys residue.21,22 Quantitative measurement of small degrees of acetylation can be challenging, however, as the weak resonances of modified Lys residues resonate typically in the immediate vicinity of the far more intense unmodified amide groups. Alternatively, acetylation can be monitored by observation of the newly generated side chain amide groups, which resonate in a distinct spectral region somewhat outside of the crowded backbone amide region.21,22 However, in practice, the 15 Lys side chains of disordered αS resonate in a very narrow spectral window, and recently introduced technical innovations combined with high magnetic fields were needed to individually resolve and assign the side chain amides of the acetylated Lys residues.

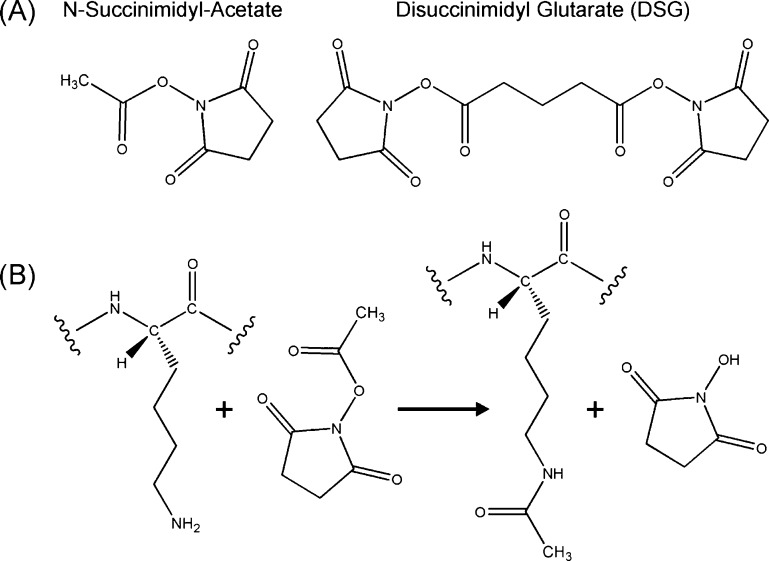

Figure 1.

Chemicals used and their reaction with lysine side chains. (A) N-Succinimidyl acetate acetylates one Lys, while DSG can cross-link two Lys side chains. (B) Chemistry of Lys side chain acetylation reaction by N-succinimidyl acetate.

Modulation of the αS Lys side chain reactivity associated with binding of the protein to lipid vesicles offers a novel avenue for probing protein membrane interaction. Although the protein itself is NMR-invisible when bound to lipid vesicles, the chemical reaction can be quenched, followed by removal of lipids and measurement of the high-resolution solution NMR spectrum of the partially modified αS. This mode of analysis can be applied to the entire range of protein–lipid stoichiometries without significant restrictions on the types of lipids that can be used. Because membrane binding by αS is considerably stronger for the N-terminally acetylated form of the protein,23,24 a post-translational modification present in all mammalian systems,5,25,26 all of our measurements were taken on this form of the protein.

Experimental Procedures

Protein Preparation

N-Terminally acetylated αS was obtained by co-expression of a plasmid containing the wild-type αS gene as well as a plasmid carrying the components of the NatB complex, using the expression protocol of Johnson et al.27 As noted previously,23 the restrictive conditions of M9 media have a strong effect on the acetylation reaction, and complete acetylation (≥98%) required supplementation of the protonated M9 medium with 1 g/L protonated IsoGro (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). IsoGro is a protein hydrolysate that approximately mimics liquid broth (LB) medium. Perdeuteration of the protein, by using fully deuterated M9 medium and 99% D2O solvent, supplemented with 1 g/L [2H,15N]IsoGro, yielded <50% N-terminal acetylation and therefore was not used in this study. Therefore, all NMR experiments were performed on either 15N-labeled or doubly 15N- and 13C-labeled αS samples, all dissolved in 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer, 10 mM NaCl, and a 95% H2O/5% D2O mixture at pH 6.0 and 283 K. Nonisotopically labeled N-terminally acetylated αS was prepared by using LB instead of M9 medium, using otherwise the same purification method. The unlabeled protein was used for CD and DSG cross-linking experiments.

Preparation of SUVs

The 5:3:2 DOPE/DOPS/DOPC lipid mixture (ESC, product no. 790304), porcine brain l-α-phosphatidylserine (PS, product no. 840032), porcine brain l-α-phosphatidylcholine (PC, product no. 840053), and 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-l-serine (POPS, product no. 840034) were all purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL). ESC, a 7:3 (w:w) porcine brain PC/PS mixture, and synthetic POPS lipid molecules were dissolved in chloroform by vortexing and dried under a N2 stream, followed by exposure to vacuum for 1 h. Lipid films were resuspended in PBS buffer by vortexing to a final lipid concentration of 30 mM. Small unilamellar vesicles (SUVs) were then generated by sonicating the resuspended lipids in a bath sonicator (P30H, Elma, Singen, Germany) at 37 kHz and 50% power for ∼2 h at room temperature to reach optical transparency.

Reaction of αS Lys Side Chains and Removal of Lipids

All Lys modification experiments were performed by diluting a 1 M stock solution of N-succinimidyl acetate (product no. S0878 from TCI America, Portland, OR), dissolved in DMSO, to a final concentration of 250 μM in PBS buffer in the presence of 50 μM αS and different concentrations of SUVs, all at room temperature. The reaction was terminated after 5 min by adding an equal volume of a 50 mM lysine (product no. 62930 from Sigma) stock solution in PBS. For cross-linking experiments followed by NMR detection, a 200 mM disuccinimidyl glutarate (DSG, product no. 20593, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL) stock solution in DMSO was diluted to a final concentration of 125 μM in PBS buffer, using otherwise the same reaction conditions described above. To remove SUVs, unreacted lysine, lysine-reacted N-succinimidyl acetate, and salt from the reaction mixture, a 10-fold volume excess of methanol was added to the mixture in which the reaction had been terminated, vortexed, and kept at −30 °C for 30 min. After centrifugation to pellet the methanol-precipitated αS, the supernatant was discarded and the pellet was washed again with 50 mL of methanol and recentrifuged. The washed pellet was dried under vacuum for ≥1 h and kept at −30 °C prior to being dissolved in NMR buffer.

Monitoring the Reactivity of N-Succinimidyl Acetate

The decay of N-succinimidyl acetate was monitored in the presence of PBS, two types of SUVs, and αS protein, as a function of the time following mixing of the reactants. Mixing was accomplished by rapid two-step dilution of a concentrated (1 M) stock solution of N-succinimidyl acetate in DMSO. The first step is 10-fold dilution of N-succinimidyl acetate in PBS buffer to a final concentration of 100 mM, and the second step is additional 400-fold dilution in PBS buffer or a protein/SUV-containing solution in an Eppendorf tube to reach a final N-succinimidyl acetate concentration of 250 μM. Each step was immediately followed by repetitive pipetting to obtain complete mixing, followed by transfer to the NMR tube. The reaction was assumed to start at the beginning of the second dilution step. The acetyl methyl peak intensity of the N-succinimidyl acetate and the methylene peak intensity of its reaction product were convenient and sensitive markers for observing the reaction process, using a time series of one-dimensional NMR spectra that included a short transverse relaxation Hahn-echo filter (total duration of 60 ms) to suppress background NMR signals from the protein and SUVs. Measurements were taken in PBS buffer and 5% D2O at 20 °C, and no addition of lysine was used to quench the reaction.

Ultra-High-Resolution Two-Dimensional (2D) 1H–15N NMR

For recording the highest-resolution 2D NMR spectra of the acetylated Lys side chain amide groups, data were collected using ∼0.2 mM 15N-enriched methanol-precipitated αS samples at 283 K on a Bruker Avance III 900 MHz spectrometer equipped with a z-axis gradient TCI cryogenic probe. The standard 2D 1H–15N HSQC pulse scheme was modified by adding homonuclear BASH decoupling28 in the 1H direct dimension (t2) with the BASH pair of 180° decoupling pulses applied every 24 ms, and 1H composite pulse decoupling in the 15N indirect (t1) dimension.29 The 15N radiofrequency carrier was set at 125.7 ppm, close to the side chain 15N amide resonances, to reduce 15N decoupling power requirements (0.7 kHz RF field) during the acquisition of t2 data. The 1H carrier was set at 4.92 ppm, and 15N WALTZ16 decoupling with a 2.5 kHz RF field was applied during the acquisition of 1H data. A RF heat compensation scheme30 was integrated in the 2 s relaxation delay to account for the increased 15N WALTZ decoupling durations at longer t1 evolution periods. For (t1, 15N) and (t2, 1H) dimensions, 1700* and 2703* complex data points were sampled, corresponding to acquisition times of 830 and 300 ms, respectively.

NMR Assignment of Acetylated Lys Side Chains

Assignment of the side chain amide signals of the acetylated Lys residues was conducted in two stages. First, the backbone assignments of acetylated Lys residues and their neighbors were established using three-dimensional (3D) triple-resonance experiments. In the second step, the backbone amide signal of each acetylated Lys residue was connected to its side chain amide signal by using high-resolution 1H–1H TOCSY mixing, as described below.

For assigning the backbone resonances of acetylated Lys residues and their neighbors, a 1.0 mM 13C- and 15N-enriched methanol-precipitated αS sample was used [prepared by reaction of 50 μM αS with 0.5 mM N-succinimidyl acetate in PBS buffer at room temperature, followed by l-lysine quenching after 5 min, lipid removal, and resuspension in 10 mM phosphate buffer (pH 6.0)] and nonuniformly sampled (NUS)31 3D HNCO, HNCA, and HN(COCO)NH spectra were recorded at either 700 or 600 MHz using Bruker Avance III spectrometers equipped with z-axis gradient TCI cryogenic probes. For HNCO, NUS with 7.5% sparsity was employed with a total data acquisition time of 1 day. The (t1, 13C), (t2, 15N), and (t3, 1H) dimensions of the time domain matrix are composed of 128* × 400* × 1024* complex data points, with acquisition times of 113, 251, and 104 ms, respectively. For HN(COCO)NH,32 NUS with 4.3% sparsity was employed, corresponding to a data acquisition time of 2 days. The time domain matrix consisted of 350* × 350* × 1024* complex data points, corresponding to acquisition times of 220 (15N), 220 (15N), and 128 (1H) ms, respectively. For HNCA, NUS with 12.0% sparsity was used, requiring 2 days of data acquisition. The time domain matrix of 136* × 400* × 1024* complex data points corresponded to acquisition times of 52 (t1, 13C), 251 (t2, 15N), and 128 ms (t3, 1H), respectively. For HN(CO)CA, a time domain matrix of 60* × 250* × 1024* complex data points was used, corresponding to acquisition times of 27 (t1, 13C), 185 (t2, 15N), and 102 ms (t3, 1H), respectively, and a total measurement time of 3 days.

The backbone amides of acetylated Lys residues were connected to their corresponding side chain amides by means of a 3D 15N-separated 1H–1H TOCSY experiment, using a 120 ms DIPSI-3 mixing scheme33 (10 kHz RF field strength). The TOCSY spectrum was recorded using a 1.5 mM 15N-enriched methanol-precipitated αS sample (prepared like the 1.0 mM 13C- and 15N-enriched αS sample). Measurements were taken at 700 MHz under the same sample conditions that were used for the ultra-high-resolution 2D NMR HSQC spectra. The time domain matrix consisted of 350* (t1, 1H) × 1250* (t2, 15N) × 2048* (t3, 1H) complex data points, with acquisition times of 50, 800, and 300 ms, respectively. The 15N and 1H carriers were set at 125.2 and 4.92 ppm, respectively. To resolve acetylated side chain resonances, composite pulse decoupling was applied in the (t2, 15N) dimension and homonuclear BASH decoupling was applied in the (t3, 1H) dimension, using the same parameters that were used for the 900 MHz ultra-high-resolution 2D 1H–15N NMR spectra mentioned above. NUS with a 2.2% sparsity was employed yielding a total measuring time of 3 days. Spectral reconstruction was conducted with the in-house written SMILE program (J. Ying, unpublished), to yield a digital resolution of 6.9 Hz (F1, 1H), 0.4 Hz (F2, 15N), and 1.7 Hz (F3, 1H) for the processed spectrum.

Circular Dichroism

All CD measurements (model J-810, JASCO, Tokyo, Japan) were performed at 20 °C using a 0.2 mm path length cuvette (20/C-Q-0.2, Starna Cells, Atascadero, CA). The αS protein concentration was kept at 50 μM while the amounts of ESC or PC/PS SUVs in PBS buffer at pH 7.4 were varied.

Mass Spectrometry

Data from liquid chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry (LC–MS) of intact proteins were obtained using a Waters (Waltham, MA) LCT Premiere time-of-flight mass spectrometer coupled to a Waters model 1525 LC unit. The MS instrument was operated in the positive ion electrospray ionization (ESI) mode, and the ESI capillary was operated at 3400 V. The HPLC instrument used a Thermo (Milford, MA) ProSwift RP-4H monolithic column with an inner diameter of 1.0 mm and a length of 250 mm. The flow rate was 100 μL/min. Solvent A was 100% water with 0.2% formic acid and 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid. Solvent B was 80% methanol and 20% acetonitrile with 0.2% formic acid and 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid. Samples were injected onto the LC column using a 10 μL PEEK loop. The LC method started at 100% A and was held for 5 min. The gradient was stepped to a 50:50 A:B ratio and held for an additional 5 min. The gradient was then stepped to 100% B and held for 10 min. The ESI charge distribution envelope was deconvoluted to molecular weight data with the MaxENT I program of the Waters MassLynx 4.1 software package.

DSG Cross-Linking Followed by Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate–Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (SDS–PAGE) Analysis

N-Terminally acetylated 100 μM solutions of αS were reacted with either 0.2 or 1.0 mM DSG cross-linker for 10 min at room temperature in PBS buffer, followed by SDS–PAGE analysis. The reaction was quenched by adding an equal volume of 50 mM lysine to the reaction mixture. The reaction was also performed in the presence of different concentrations of ESC, PC/PS, and POPS SUVs under otherwise identical conditions.

Results and Discussion

Reactivity of N-Succinimidyl Acetate

Cross-linking agents are generally unstable in aqueous solution, and the same applies to N-succinimidyl acetate. We measured its decay rate in the absence and presence of amine groups, specifically by adding 50 μM αS, effectively comprising 0.75 mM Lys Cε amine groups, or lipid vesicles consisting of either ESC lipids or POPC/POPS (7:3) lipids at a concentration of 10 mM. The vesicles carry amines on the phosphatidylethanolamine and phosphatidylserine headgroups at concentrations that correspond to ∼8 mM (ESC) and 3 mM (POPC/POPS). However, as it is unclear whether N-succinimidyl acetate can fully diffuse to the interior of the SUVs on the time scale on which our measurements were taken, the actual concentration of accessible lipid amine groups could be lower. The decay of N-succinimidyl acetate was monitored by observing the time dependence of its acetate CH3 NMR signal, as well as by the appearance of new “product”, the equivalent methylene NMR signals of free N-hydroxysuccinimide (Figure 2). As one can see, the decay is strongly enhanced by the presence of αS, and to a lesser extent by the lipid vesicles, indicating that the Lys amino groups have higher reactivity toward the cross-linkers than the phospholipid amine groups by ∼1 order of magnitude. For technical reasons (transfer of the sample, temperature equilibration, and shimming of the magnetic field), the first time point of NMR intensities can be collected only ∼5 min after mixing of the reactants. When simply using PBS buffer, the buildup of product and decrease of the succinimidyl acetate CH3 signal follow the expected pattern, extrapolating to zero product and no CH3 decay at time zero, where the DMSO succinimidyl acetate solution was added to the buffer. However, in the presence of proteins or lipid vesicles, we observe a “burst phase”, followed by the regular decay and buildup of product (Figure 2). This burst phase results in the presence of a non-negligible amount of product when extrapolating to time zero, an amount approximately equivalent to extending the actual reaction time by ∼5 min. The reason for the initial rapid reaction of a small fraction of the reactants is unknown, but the observation itself is highly reproducible and was taken into account during the quantitative analysis. Regardless, the extent of decay of succinimidyl acetate is small, less than ∼15%, within 5 min of the materials being mixed. As discussed below, the reactions between succinimidyl acetate and αS in the absence and presence of SUVs are quenched 5 min after mixing. The rates at which the succinimidyl acetate NMR signals decay (after the burst phase) correspond to the total reaction rate, i.e., the sum of its natural decay rate, its reaction with lipid amine groups, and α-synuclein, and to a good approximation can be derived from fitting the decaying methyl group intensity to an exponential function. The sharp methylene protons of the free N-hydroxysuccinimide serve as a useful complement for measuring the total amount of reacted material at any given time (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Reaction kinetics of 0.25 mM N-succinimidyl acetate monitored by the intensity decay of its methyl NMR resonance and the intensity increase of the product’s methylene NMR resonance (red arrows), in samples consisting of PBS buffer (circles), 10 mM PC/PS SUVs (triangles), 50 μM αS (diamonds), or 10 mM ESC SUVs (squares), all at 20 °C in PBS buffer.

NMR Assignment of Fractionally Acetylated αS

Acetylation of any given Lys side chain by reaction with N-succinimidyl acetate causes substantial changes in resonance frequency for the modified Lys residue and its immediate neighbors but also causes very small chemical shift changes in more remote residues. As a result, αS molecules that have been acetylated, for example, at an average level of 33%, contain approximately five acetylated residues at positions that are, to first order, randomly distributed among its 15 Lys. Such a high level of random acetylation results in very extensive heterogeneous line broadening of the NMR spectrum, making its detailed analysis virtually impossible. We therefore resorted to a much lower level (≤∼7%) of acetylation, such that the effect of multiple acetylations in a single protein remains weak and spectral resolution remains high. Clearly, however, the new resonances resulting from the partial acetylation remain >1 order of magnitude weaker than those of residues that are not impacted by acetylation. Their assignment therefore becomes challenging, in particular considering that many of these weak resonances fall very close to the much stronger resonances of the nonacetylated chain (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Assignment of acetylated αS lysine side chains, illustrated for K6. Initially, backbone 15N–1H chemical shifts of acetylated Lys residues and their neighbors were assigned using conventional triple-resonance experiments at very high resolution, using NUS data acquisition. The bottom left panel shows backbone 15N–1H correlations of unmodified and acetylated K6. The backbone chemical shifts of αS containing acetylated Lys at position i progressively converge to that of unmodified αS beyond position i ± 1. Next, a high-resolution 3D NUS 1H(t1)–TOCSY–15N(t2)–1H(t3) experiment permits the connection of backbone (red) and side chain (blue) amides to the aliphatic protons. By matching the chemical shifts of these aliphatic protons, we linked amide chemical shifts of the backbone and side chain for acetylated Lys residues. The TOCSY spectrum (120 ms mixing time) was recorded at 700 MHz using 1.5 mM αS.

A standard triple-resonance assignment strategy was used to assign the weak resonances of acetylated chains, relying primarily on HNCO, HNCA, HNCOCA, and HN(COCO)NH32 triple-resonance spectra that had been recorded at very high resolution by using NUS of the time domain data.31 The analysis was aided by prior complete assignments of the nonacetylated protein14 and the N-terminally acetylated protein,23 and using the consideration that resonances of nuclei that are separated by more than one residue from an acetylated residue essentially merge with the much stronger resonances of the nonacetylated protein. Moreover, to first order, the effect of Lys side chain acetylation on the backbone resonances is rather similar among the different acetylated sites. For example, Lys acetylation results in chemical shift changes of its own backbone 1HN, 15N, 13Cα, and 13C′ of approximately −0.07, 0.13, 0.23, and 0.22 ppm, respectively, and smaller chemical shift changes for its neighboring residues (Figure 4). In principle, the level of acetylation for each Lys residue can be extracted from the intensity ratio of the minor component in the HNCO spectrum, corresponding to the acetylated side chain, and that of the corresponding main resonance of the nonacetylated residue. However, even at the very high spectral resolution of the NUS-recorded spectra, for a number of residues this ratio could not be determined accurately because of partial resonance overlap. Instead, therefore, we resorted to measurement of the new amide resonances that resulted from acetylation of the Lys side chain.

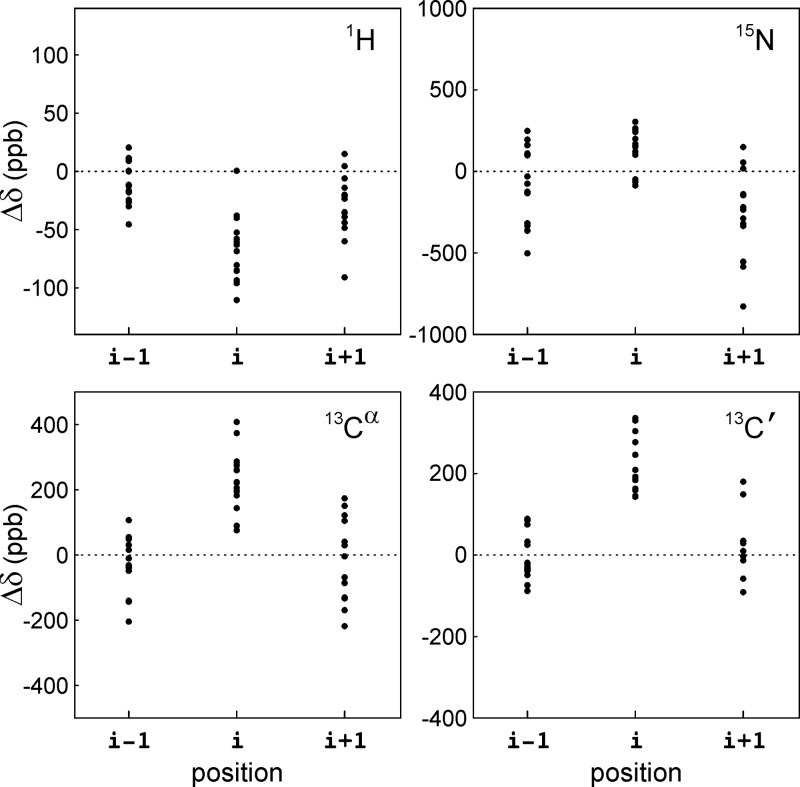

Figure 4.

Distribution of backbone chemical shift perturbations caused by Lys acetylation. Differences between the 1H, 15N, 13Cα, and 13C′ chemical shifts of acetylated Lys residues and corresponding values of the unmodified counterpart, for the 15 Lys residues in αS (i) and their flanking residues (i – 1 and i + 1).

The acetylated side chains of Lys residues give rise to correlations in the 15N–1H HSQC spectrum, all located in a very small region centered at ∼127.4/8.0 ppm (Figure 5). Even when this spectrum was recorded at the highest attainable resolution with a conventional HSQC experiment, this spectral region could not be fully resolved (Figure 5A). In part, this is caused by the two 3J(Hε2,Hζ) and 3J(Hε3,Hζ) couplings, which are a necessary consequence of the difficulty of obtaining full N-terminal acetylation for perdeuterated αS, forcing us to work with protonated protein.23 Second, the effect of relatively short T1 relaxation times of protons with a long-range coupling to Nζ adversely impacts the attainable 15N resolution. For this reason, we resorted to the recently introduced 1H–1H BASH-decoupled version of the HSQC experiment28 and additionally used composite pulse 1H decoupling in the 15N dimension rather than the conventional single 1H 180° pulse.29 The much higher resolution that can be attained with this BASH-decoupled experiment yielded resolved resonances for all of the 15 side chain amides (Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

Small regions of the 2D 1H–15N HSQC NMR spectra, showing the Lys side chain amide signals of chemically acetylated αS. To obtain a low level (≤∼7%) of side chain acetylation, reactions with 0.25 mM N-succinimidyl acetate were quenched after 5 min by addition of an equal volume of 50 mM l-lysine. Spectra were recorded at 900 MHz and 10 °C in 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer and 10 mM NaCl (pH 6.0), with an αS concentration of 0.2 mM. Spectra were acquired using (A) a standard 15N–1H HSQC pulse scheme, utilizing a single 1H pulse for t1 decoupling and no homonuclear decoupling during detection, and (B) 1H composite pulse decoupling in the t1 dimension29 and 1H-BASH homonuclear decoupling during t2.28 Acquisition times were 830 ms for 15N and 200 ms for 1H in panel A and 830 ms for 15N and 300 ms for 1H in panel B.

Assignment of the side chain amide resonances was accomplished by linking them to the assigned backbone amide groups of the acetylated Lys residues described above, using a long-mixing-time 3D 15N-separated 1H–1H TOCSY experiment. Small differences in the side chain 1H resonance frequencies among the different acetylated Lys residues proved to be crucial for establishing unique linkages between backbone and side chain amides (Figure 3).

Impact of Lipid Vesicles on αS Acetylation Rates

With the exception of the C-terminal residues, in the presence of lipid vesicles, NMR signals of αS are invisible by solution NMR,13,14 making it impossible to directly observe the degree of Lys acetylation in the presence of SUVs from the NMR spectrum. Instead, we therefore removed the lipids after an initial 5 min reaction with 0.25 mM N-succinimidyl acetate, which was quenched by the addition of an equal volume containing 50 mM lysine. In passing, we note that quenching with Tris buffer, often used as the quenching agent of choice in such reactions, caused a brief increase in the actual protein acetylation rate, interfering with quantitative analysis. The protein was separated from the reaction product by methanol precipitation and methanol washing steps, completely dried, and then dissolved to a concentration of 0.2 mM in 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 6.0), 10 mM NaCl, 95% H2O, and 5% D2O, with NMR spectra recorded at 10 °C.

Intensities of the side chain amide groups were readily measured from such spectra and normalized to the average intensity of resonances not visibly impacted by Lys acetylation, as applies for many of the C-terminal residues. All side chain Lys amide groups are sharp and fairly well resolved, and peak picking confirmed that they had essentially indistinguishable line widths of 4.9 ± 0.3 Hz (1H) and 1.1 ± 0.1 Hz (15N). However, rather than integrating each individual resonance, which adversely impacts the signal-to-noise ratio, we determined relative side chain intensities from peak heights. The total intensity of all side chain amides, however, was obtained by integrating the small spectral region containing these side chain amides and normalizing this integrated intensity to that of the unaffected backbone amide resonances in the same sample. The result shows a strong attenuation of side chain acetylation with increasing vesicle concentration for nearly all Lys residues (Figure 6). The only exception is Lys-102, which previously was identified as being outside the lipid-binding region of the protein.13,14,34,35 This residue, which shows the weakest acetylation in the absence of lipids (Figure 6A), is little protected by lipid binding of the protein and becomes the most acetylated residue in the presence of ESC SUVs (Figure 6B).

Figure 6.

Reaction of αS Lys residues (50 μM protein) with 250 μM N-succinimidyl acetate in the presence of different ESC (5:3:2 DOPE:DOPS:DOPC) SUV concentrations. (A) High-resolution 2D 1H–15N NMR spectra of the acetylated side chain region in the absence (top) and presence (bottom) of a 200-fold molar excess of ESC SUVs. Lower contour levels were used for the bottom panel for better visibility. (B) Change of the second-order rate constants with increasing lipid:αS ratio, L, illustrated for K6, K32, and K102. Dashed lines correspond to Kn(L) = Ane–BnL + Cn, where Kn is the second-order rate constant for the reaction of N-succinimidyl acetate with any given Lys in αS, L is the lipid:αS molar ratio, and An, Bn, and Cn are the fitted parameters. (C) Designation of different regions in the primary structure of αS. At low lipid:αS ratios, two binding modes are believed to exist, SL1 and SL2, where the first ∼25 and ∼100 N-terminal residues are NMR-invisible, respectively.14 αS consists of a positively charged N-terminal region, a hydrophobic NAC (non-amyloid-β component, residues 61–95) region, and an acidic C-terminal region. (D) Reaction rate, An + Cn, as a function of residue number in the absence of lipids. (E) Bn as a function of residue number, which reflects the sensitivity of the reaction rate constant to lipid concentration, at a low lipid:αS ratio. (F) Cn/(An + Cn) as a function of Lys residue number, n, which is a measure for the attenuation of Lys reactivity in the high lipid/αS limit.

The lipid dependence of the residue-specific acetylation rate of residue n, Kn, in the presence of lipids can be fit to the following empirical equation

| 1 |

where Cn corresponds to the acetylation rate of residue n extrapolated to a very large excess of lipids, i.e., all αS in the lipid-bound state; L is the lipid:protein ratio; Bn is a fitted constant that reflects the degree of protection from acetylation caused by lipid binding; and An= Kn(0) – Cn. We also define a reactivity attenuation factor

| 2 |

which corresponds to the fractional acetylation reactivity of residue n in the lipid-saturated state, compared to a lipid-free αS sample. Attenuation factors, αn, are found to be rather homogeneous for the different Lys residues in αS (Figure 6F), but as expected, the protection becomes progressively weaker for the C-terminal residues, K96, K97, and K102, the latter one previously identified as being outside of the actual lipid-binding region. Small variations among the other Lys residues presumably reflect the strength of the salt bridge between the positively charged Lys Cε amino group and the negatively charged phospholipid headgroup.

Coefficient Bn in eq 2 reflects the degree of protection against acetylation of the Lys-n side chain in the presence of small amounts of lipid vesicles, i.e., the limit at which insufficient SUV surface is available to accommodate all αS molecules. Clearly, B6 and B10 of residues K6 and K10 are ∼50% higher than the other B coefficients, consistent with the previously proposed initiation–elongation mode for binding of the N-acetylated protein to SUVs.23 Remarkably, all 13 remaining Lys residues show rather homogeneous Bn values, even though at high lipid:protein ratios the most C-terminal Lys residues are less protected from acetylation (high αn values). This result indicates that residues in the region from Lys-15 to Lys-102 share the same dependence on lipid concentration, i.e., that binding modes at which only the ∼25 N-terminal residues are bound to the vesicle (SL1 mode in the nomenclature of Bodner et al.14) are rare. The apparent discrepancy may be resolved if the SL1 mode resonance attenuation is attributed to lipid binding by the dozen N-terminal residues of αS, which through restricted motion of nearby residues in the disordered protein chain also attenuates amide signals up to approximately residue 30.

Reactivity of Lys with DSG and N-Succinimidyl Acetate

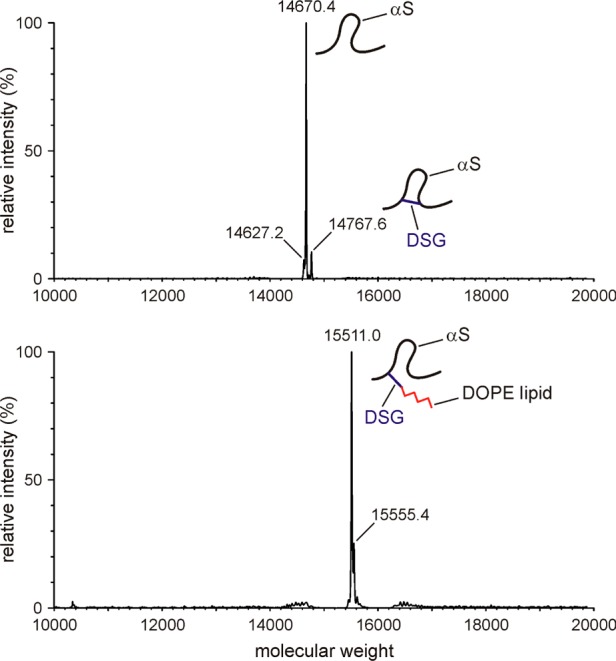

Although the chemistry underlying reaction of DSG with the Lys Cε amine group is very similar to the acetylation reaction with N-succinimidyl acetate (Figure 1), NMR analysis of the reaction product is much more complex for two reasons. First, after one of the reactive sites of DSG becomes covalently attached to a Lys residue, the effective “local concentration” of its second reactive site for nearby Lys residues will be very high, greatly increasing the chances that this second site will react, too, effectively forming an intramolecular cross-link. A total of 105 different intramolecular links can be generated among the 15 Lys residues of the protein, resulting in considerable heterogeneity and small chemical shift perturbations throughout the protein chain. Second, when the reaction is performed in the presence of SUVs, after one DSG site has reacted with the Lys amine group, the second reactive site can covalently link to a phospholipid amine group, adding a large hydrophobic tag to the protein that will favor clustering of the many hydrophobic αS residues in its vicinity after the protein has been methanol-extracted and dissolved in water, again perturbing backbone chemical shifts. Indeed, a substantial but not dominant fraction of such lipid-linked αS is observed by liquid chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry [LC–MS (Figure 7)]. Additionally, the LC–MS data provide evidence of the presence of intramolecularly linked Lys residues (+97 Da). Interestingly, no detectable amount of DSG-modified αS is observed where the second DSG site has reacted with the quencher molecule, free lysine (+242 Da) (Figure 7). This result indicates that after a given DSG molecule has reacted with a protein Lys residue, its second reactive site rapidly reacts with a second amine because of the high local concentration of both phospholipid amines and other αS Lys amine groups, keeping the concentration of “half-reacted” and subsequently quenched DSG molecules very low.

Figure 7.

Mass characterization of αS/SUV samples after DSG cross-linking. A mixture of 50 μM 15N-enriched N-terminally acetylated αS with 2.5 mM ESC SUV (1:50 αS:ESC SUV) in PBS buffer was reacted with 125 μM DSG for 5 min at room temperature, followed by LC–MS to characterize the mass. The main peaks with molecular masses of 14670, 14768, and 15511 correspond to αS, intramolecularly cross-linked αS, and αS–DOPE cross-linked species, respectively. No separate peaks for αS–DOPS or αS–Lys cross-linked species were observed. Top and bottom panels represent different LC fractions. Note that all measurements were taken on NMR samples containing uniformly 15N-enriched αS, increasing its mass by ∼168 Da over that of the natural abundance protein.

Despite the high degree of heterogeneity in the reaction products of αS and DSG, the new amide groups of the derivatized αS Lys side chains all resonate in a narrow spectral region, slightly upfield in the 15N chemical shift dimension from the acetylated Lys side chain amide groups (Figure 8). Although the high complexity of the αS–DSG reaction product is evident from the spectrum, the total number of αS Lys side chains that have undergone a reaction with DSG can readily be quantified by integrating the region where the new peaks resonate.

Figure 8.

Overlay of the 2D BASH-decoupled 1H–15N HSQC NMR spectra of αS Lys side chains reacted with 250 μM N-succinimidyl acetate (black) or 125 μM disuccinimidyl glutarate (DSG) cross-linker (orange). The reaction conditions are the same as those described in the legend of Figure 6 (1:50 αS:ESC SUV). The DSG-reacted spectrum (orange) is displayed at a 2-fold lower contour level compared with that of the black spectrum for better visibility of the broad heterogeneous resonances.

For lipid-free reactions between αS and DSG, we find that the fraction of reacted Lys residues is ∼60% higher upon comparison of the reactions between 50 μM αS and either 125 μM DSG or 250 μM N-succinimidyl acetate (where the 50% lower concentration of DSG accounts for the fact that it contains a linked pair of N-succinimidyl groups). This result is consistent with the increase in the “effective local concentration” of succinimidyl groups once the first DSG site has become linked to an αS Lys residue mentioned above.

Lipid Dependence of Reactivity Attenuation

The binding of αS for lipid vesicles depends strongly on the composition of the lipids, as well as on the size of vesicles. Lipids with negatively charged headgroups, such as POPG and POPS, are known to increase the affinity of αS for the bilayer, and strong curvature (i.e., small size of the SUV) also promotes binding.15−17,36−38 Although a full analysis of the impact of the membrane parameters known to modulate αS binding on protection against reaction with N-succinimidyl acetate goes beyond the scope of this study, we briefly evaluated whether vesicles that show a very similar affinity for αS also show the same degree of protection. For this purpose, we compare the results obtained with ESC SUVs, chosen to approximately mimic the lipid composition of presynaptic vesicles,14 with those obtained with PC/PS SUVs (7:3 POPC:POPS), used by Burre et al. when studying the effect of αS on SNARE complex formation.10,39

Binding of αS as judged by the induced transition from random coil for the lipid-free form to the α-helical CD signature upon lipid binding shows a virtually indistinguishable dependence on lipid concentration (Figure S1). Nevertheless, the degree of protection against acetylation is rather different for the two types of vesicles and shows a systematically lower level of protection for the PC/PS vesicles compared to the ESC vesicles, both at intermediate (200:1) and at near-saturating (500:1) lipid:protein ratios (Figure 9). If the difference in protection were caused by a difference in lipid affinity for the protein, a difference in slope between the apparent rate constants would have been expected. Instead, the nearly uniform offset between the rates observed in the presence of the two different types of vesicles points to a different degree of amine group protection in the lipid-bound state. Considering that for both types of vesicles phosphatidylserines are the only negatively charged headgroups expected to make a salt bridge with the Lys amino groups, and that they are present at the same molar fraction for both types of vesicles, this suggests that other factors modulate the strength of such interactions. This latter observation is perhaps not surprising, considering the strong dependence of αS membrane affinity on a wide range of parameters, including fluidity, charge, curvature, packing, and alkyl chain composition.15,36−38,40,41 We also point out that at 6.4 M–1 s–1, the bimolecular reaction rate between N-succinimidyl acetate and αS (summed over all 15 Lys residues) is far higher than for PS (0.080 M–1 s–1) in the PC/PS SUVs or for PE in the ESC SUVs (0.038 M–1 s–1) (assuming the PS reactivity is the same in ESC and PC/PS SUVs). These reaction rates are more than 8 orders of magnitude below the diffusion-controlled reaction rate limit, and therefore, no significant spatial gradient in N-succinimidyl acetate concentration in the vicinity of the vesicles occurs. This means that the difference in reactivity of synuclein’s Lys residues when bound to ESC SUVs or PC/PS SUVs indeed must be attributed to differences in Lys amine group protection and cannot result from the higher total reactivity of the ESC lipids.

Figure 9.

Comparison of αS Lys reactivity with N-succinimidyl acetate in the presence of (A) moderate (200:1) and (B) near-saturating (500:1) quantities of different SUVs. Shown are the apparent second-order rate constants in the presence of ESC SUVs (5:3:2 DOPE:DOPS:DOPC) and PC/PS SUVs (7:3 POPC:POPS). Note that the acetylation rate of K102 is minimally impacted by the amount or type of lipids, whereas for all other residues, the ESC SUVs are more protective than PC/PS SUVs.

Concluding Remarks

Protection of Lys amino groups against acetylation by N-succinimidyl acetate provides a convenient quantitative probe for detecting intermolecular interactions. The side chain amide groups of acetylated Lys groups can readily be detected by NMR spectroscopy, yielding a straightforward method for quantitative analysis. However, even though the protection against acetylation will be controlled by the accessibility of the amino group to the reactant, it may also be impacted even by a small shift in its pKa value when a protein is engaged in an intermolecular interaction. The different degrees of protection when αS interacts with ESC or PC/PS vesicles (Figure 9), for which it has comparable affinity, highlight these factors.

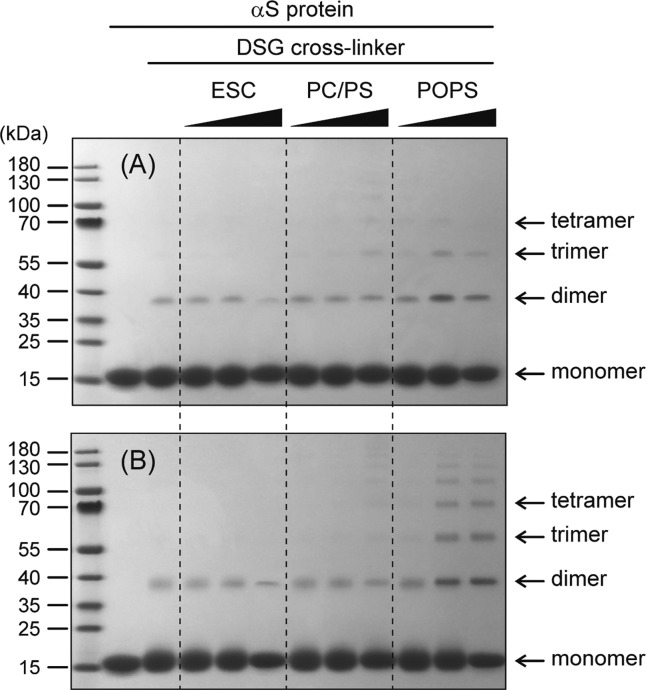

The degree of reactivity attenuation upon lipid binding is also an important consideration when interpreting conventional protein cross-linking experiments. For example, glutaraldehyde cross-linking experiments conducted on membrane-bound αS provided evidence of mostly even-numbered oligomers on the surface of PC/PS vesicles.42 However, in the presence of ESC vesicles, intermolecular cross-linking by DSG is actually reduced, despite the increase in local concentration on the surface of the SUV. In particular, for a 500:1 lipid:αS ratio, less smearing of the monomer band is observed, an indication that less intramolecular cross-linking is observed than for the free protein, or at lower 50:1 lipid:αS ratios (Figure 10). The level of protection of the Lys amine groups is lower when the protein is bound to PC/PS vesicles (Figure 9), and weak oligomeric bands are observed at the 500:1 lipid:αS ratio (Figure 10), indicating that the increased local concentration more than compensates for the decreased reactivity of the side chains. When using SUVs that solely contain POPS, an actual increase in the level of cross-linking, including trimers, tetramers, and even higher-order oligomers, is observed, indicating that the reactivity of αS Lys residues is less attenuated when they are bound to these vesicles and no longer fully compensates for the high local concentration of the protein on the SUV surface.

Figure 10.

Effect of lipid vesicle composition on αS oligomerization analyzed by DSG cross-linking. N-Terminally acetylated 100 μM αS was reacted with (A) 0.2 and (B) 1.0 mM DSG cross-linker for 10 min at room temperature in the presence of increasing amounts (1:5, 1:50, and 1:500 αS:SUV) of ESC, PC/PS, and POPS SUVs. The gels were stained with Coomassie blue.

Chemical cross-linking experiments are a widely used and very powerful tool for probing both weak and strong protein–protein interactions, even in a cellular environment. However, results are strongly modulated by the reactivity of the reactive groups on the protein surface. As we have shown here for the most widely used cross-linking measurements, involving Lys Cε amino groups, this reactivity can readily and quantitatively be probed by NMR spectroscopy, providing a possible avenue to a more quantitative analysis of cross-linking data observed by mass spectrometry.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge use of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Advanced Mass Spectrometry Core Facility and particularly John Lloyd for his extensive assistance with LC–MS measurements and interpretation, and we thank Hee-Yong Kim and Bill Huang (National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism) for helpful discussions about chemical cross-linking.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- 2D

two-dimensional

- 3D

three-dimensional

- αS

α-synuclein

- CD

circular dichroism

- DSG

disuccinimidyl glutarate

- EPR

electron paramagnetic resonance

- ESC

5:3:2 molar mixture of DOPE (dioleoylphosphatidylethanolamine), DOPS (1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-l-serine), and DOPC (1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine)

- HSQC

heteronuclear single-quantum coherence

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- NMR

nuclear magnetic resonance

- NUS

nonuniformly sampled

- PC

porcine brain l-α-phosphatidylcholine

- PS

porcine brain l-α-phosphatidylserine

- SUV

small unilamellar vesicle

- TOCSY

total correlation spectroscopy.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acs.biochem.6b00637.

Supplemental figure, showing CD spectra, and two supplemental tables containing chemical shift perturbations and residue-specific second-order rate constants (PDF)

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases and by the Intramural Antiviral Target Program of the Office of the Director, National Institutes of Health.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Sinz A. (2006) Chemical cross-linking and mass spectrometry to map three-dimensional protein structures and protein-protein interactions. Mass Spectrom. Rev. 25, 663–682. 10.1002/mas.20082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avrameas S.; Ternynck T. (1969) Cross-Linking of Proteins with Glutaraldehyde and Its Use for Preparation of Immunoadsorbents. Immunochemistry 6, 53–66. 10.1016/0019-2791(69)90178-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dettmer U.; Newman A. J.; Luth E. S.; Bartels T.; Selkoe D. (2013) In Vivo Cross-linking Reveals Principally Oligomeric Forms of alpha-Synuclein and beta-Synuclein in Neurons and Non-neural Cells. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 6371–6385. 10.1074/jbc.M112.403311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fauvet B.; Mbefo M. K.; Fares M.-B.; Desobry C.; Michael S.; Ardah M. T.; Tsika E.; Coune P.; Prudent M.; Lion N.; Eliezer D.; Moore D. J.; Schneider B.; Aebischer P.; El-Agnaf O. M.; Masliah E.; Lashuel H. A. (2012) alpha-Synuclein in Central Nervous System and from Erythrocytes, Mammalian Cells, and Escherichia coli Exists Predominantly as Disordered Monomer. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 15345–15364. 10.1074/jbc.M111.318949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartels T.; Choi J. G.; Selkoe D. J. (2011) alpha-Synuclein occurs physiologically as a helically folded tetramer that resists aggregation. Nature 477, 107–U123. 10.1038/nature10324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dettmer U.; Newman A. J.; Soldner F.; Luth E. S.; Kim N. C.; von Saucken V. E.; Sanderson J. B.; Jaenisch R.; Bartels T.; Selkoe D. (2015) Parkinson-causing alpha-synuclein missense mutations shift native tetramers to monomers as a mechanism for disease initiation. Nat. Commun. 6, 7314. 10.1038/ncomms8314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luth E. S.; Bartels T.; Dettmer U.; Kim N. C.; Selkoe D. J. (2015) Purification of alpha-Synuclein from Human Brain Reveals an Instability of Endogenous Multimers as the Protein Approaches Purity. Biochemistry 54, 279–292. 10.1021/bi501188a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theillet F.-X.; Binolfi A.; Bekei B.; Martorana A.; Rose H. M.; Stuiver M.; Verzini S.; Lorenz D.; van Rossum M.; Goldfarb D.; Selenko P. (2016) Structural disorder of monomeric alpha-synuclein persists in mammalian cells. Nature 530, 45–50. 10.1038/nature16531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binolfi A.; Limatola A.; Verzini S.; Kosten J.; Theillet F.-X.; May Rose H.; Bekei B.; Stuiver M.; van Rossum M.; Selenko P. (2016) Intracellular repair of oxidation-damaged alpha-synuclein fails to target C-terminal modification sites. Nat. Commun. 7, 10251. 10.1038/ncomms10251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burre J.; Sharma M.; Suedhof T. C. (2014) alpha-Synuclein assembles into higher-order multimers upon membrane binding to promote SNARE complex formation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 111, E4274–E4283. 10.1073/pnas.1416598111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varkey J.; Mizuno N.; Hegde B. G.; Cheng N.; Steven A. C.; Langen R. (2013) alpha-Synuclein Oligomers with Broken Helical Conformation Form Lipoprotein Nanoparticles. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 17620–17630. 10.1074/jbc.M113.476697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eichmann C.; Campioni S.; Kowal J.; Maslennikov I.; Gerez J.; Liu X.; Verasdonck J.; Nespovitaya N.; Choe S.; Meier B. H.; Picotti P.; Rizo J.; Stahlberg H.; Riek R. (2016) Preparation and Characterization of Stable -Synuclein Lipoprotein Particles. J. Biol. Chem. 291, 8516–8527. 10.1074/jbc.M115.707968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eliezer D.; Kutluay E.; Bussell R.; Browne G. (2001) Conformational properties of alpha-synuclein in its free and lipid-associated states. J. Mol. Biol. 307, 1061–1073. 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodner C. R.; Dobson C. M.; Bax A. (2009) Multiple Tight Phospholipid-Binding Modes of alpha-Synuclein Revealed by Solution NMR Spectroscopy. J. Mol. Biol. 390, 775–790. 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.05.066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson W. S.; Jonas A.; Clayton D. F.; George J. M. (1998) Stabilization of alpha-synuclein secondary structure upon binding to synthetic membranes. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 9443–9449. 10.1074/jbc.273.16.9443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandra S.; Chen X. C.; Rizo J.; Jahn R.; Sudhof T. C. (2003) A broken alpha-helix in folded alpha-synuclein. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 15313–15318. 10.1074/jbc.M213128200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuscher B.; Kamp F.; Mehnert T.; Odoy S.; Haass C.; Kahle P. J.; Beyer K. (2004) alpha-synuclein has a high affinity for packing defects in a bilayer membrane - A thermodynamics study. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 21966–21975. 10.1074/jbc.M401076200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bussell R.; Ramlall T. F.; Eliezer D. (2005) Helix periodicity, topology, and dynamics of membrane-associated alpha-Synuclein. Protein Sci. 14, 862–872. 10.1110/ps.041255905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robotta M.; Braun P.; van Rooijen B.; Subramaniam V.; Huber M.; Drescher M. (2011) Direct Evidence of Coexisting Horseshoe and Extended Helix Conformations of Membrane-Bound Alpha-Synuclein. ChemPhysChem 12, 267–269. 10.1002/cphc.201000815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morar A. S.; Olteanu A.; Young G. B.; Pielak G. J. (2001) Solvent-induced collapse of alpha-synuclein and acid-denatured cytochrome c. Protein Sci. 10, 2195–2199. 10.1110/ps.24301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liokatis S.; Dose A.; Schwarzer D.; Selenko P. (2010) Simultaneous Detection of Protein Phosphorylation and Acetylation by High-Resolution NMR Spectroscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 14704–14705. 10.1021/ja106764y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theillet F.-X.; Smet-Nocca C.; Liokatis S.; Thongwichian R.; Kosten J.; Yoon M.-K.; Kriwacki R. W.; Landrieu I.; Lippens G.; Selenko P. (2012) Cell signaling, post-translational protein modifications and NMR spectroscopy. J. Biomol. NMR 54, 217–236. 10.1007/s10858-012-9674-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maltsev A. S.; Ying J. F.; Bax A. (2012) Impact of N-Terminal Acetylation of α-Synuclein on Its Random Coil and Lipid Binding Properties. Biochemistry 51, 5004–5013. 10.1021/bi300642h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartels T.; Kim N. C.; Luth E. S.; Selkoe D. J. (2014) N-Alpha-Acetylation of alpha-Synuclein Increases Its Helical Folding Propensity, GM1 Binding Specificity and Resistance to Aggregation. PLoS One 9, e103727. 10.1371/journal.pone.0103727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson J. P.; Walker D. E.; Goldstein J. M.; de laat R.; Banducci K.; Caccavello R. J.; Barbour R.; Huang J.; Kling K.; Lee M.; Diep L.; Keim P. S.; Shen X.; Chataway T.; Schlossmacher M. G.; Seubert P.; Schenk D.; Sinha S.; Gai W. P.; Chilcote T. J. (2006) Phosphorylation of Ser-129 is the dominant pathological modification of alpha-synuclein in familial and sporadic Lewy body disease. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 29739–29752. 10.1074/jbc.M600933200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theillet F.-X.; Binolfi A.; Frembgen-Kesner T.; Hingorani K.; Sarkar M.; Kyne C.; Li C.; Crowley P. B.; Gierasch L.; Pielak G. J.; Elcock A. H.; Gershenson A.; Selenko P. (2014) Physicochemical Properties of Cells and Their Effects on Intrinsically Disordered Proteins (IDPs). Chem. Rev. 114, 6661–6714. 10.1021/cr400695p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson M.; Coulton A. T.; Geeves M. A.; Mulvihill D. P. (2010) Targeted Amino-Terminal Acetylation of Recombinant Proteins in E. coli. PLoS One 5, e15801. 10.1371/journal.pone.0015801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ying J.; Roche J.; Bax A. (2014) Homonuclear decoupling for enhancing resolution and sensitivity in NOE and RDC measurements of peptides and proteins. J. Magn. Reson. 241, 97–102. 10.1016/j.jmr.2013.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bax A.; Ikura M.; Kay L. E.; Torchia D. A.; Tschudin R. (1990) Comparison of different modes of two-dimensional reverse-correlation NMR for the study of proteins. J. Magn. Reson. 86, 304–318. 10.1016/0022-2364(90)90262-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang A. C.; Bax A. (1993) Minimizing the Effects of Radiofrequency Heating in Multidimensional NMR Experiments. J. Biomol. NMR 3, 715–720. 10.1007/BF00198374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orekhov V. Y.; Jaravine V. A. (2011) Analysis of non-uniformly sampled spectra with multi-dimensional decomposition. Prog. Nucl. Magn. Reson. Spectrosc. 59, 271–292. 10.1016/j.pnmrs.2011.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li F.; Lee J. H.; Grishaev A.; Ying J.; Bax A. (2015) High Accuracy of Karplus Equations for Relating Three-Bond J Couplings to Protein Backbone Torsion Angles. ChemPhysChem 16, 572–578. 10.1002/cphc.201402704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaka A. J.; Lee C. J.; Pines A. (1988) Iterative Schemes for Bilinear Operators; Application to Spin Decoupling. J. Magn. Reson. 77, 274–293. 10.1016/0022-2364(88)90178-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lokappa S. B.; Suk J.-E.; Balasubramanian A.; Samanta S.; Situ A. J.; Ulmer T. S. (2014) Sequence and Membrane Determinants of the Random Coil-Helix Transition of alpha-Synuclein. J. Mol. Biol. 426, 2130–2144. 10.1016/j.jmb.2014.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fusco G.; De Simone A.; Gopinath T.; Vostrikov V.; Vendruscolo M.; Dobson C. M.; Veglia G. (2014) Direct observation of the three regions in alpha-synuclein that determine its membrane-bound behaviour. Nat. Commun. 5, 3827. 10.1038/ncomms4827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Rooijen B. D.; Claessens M. M. A. E.; Subramaniam V. (2008) Membrane binding of oligomeric alpha-synuclein depends on bilayer charge and packing. FEBS Lett. 582, 3788–3792. 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghio S.; Kamp F.; Cauchi R.; Giese A.; Vassallo N. (2016) Interaction of alpha-synuclein with biomembranes in Parkinson’s disease -role of cardiolipin. Prog. Lipid Res. 61, 73–82. 10.1016/j.plipres.2015.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhoades E.; Ramlall T. F.; Webb W. W.; Eliezer D. (2006) Quantification of alpha-synuclein binding to lipid vesicles using fluorescence correlation spectroscopy. Biophys. J. 90, 4692–4700. 10.1529/biophysj.105.079251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burre J.; Sharma M.; Tsetsenis T.; Buchman V.; Etherton M. R.; Suedhof T. C. (2010) alpha-Synuclein Promotes SNARE-Complex Assembly in Vivo and in Vitro. Science 329, 1663–1667. 10.1126/science.1195227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stockl M.; Fischer P.; Wanker E.; Herrmann A. (2008) alpha-Synuclein selectively binds to anionic phospholipids embedded in liquid-disordered domains. J. Mol. Biol. 375, 1394–1404. 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.11.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beyer K. (2007) Mechanistic aspects of Parkinson’s disease: alpha-synuclein and the biomembrane. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 47, 285–299. 10.1007/s12013-007-0014-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burre J.; Sharma M.; Suedhof T. C. (2015) Definition of a Molecular Pathway Mediating alpha-Synuclein Neurotoxicity. J. Neurosci. 35, 5221–5232. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4650-14.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.