Abstract

Photodynamic therapy (PDT) is an established treatment modality for non–small cell lung cancer. Phototoxicity, the primary adverse event, is expected to be minimized with the introduction of new photosensitizers that have shown promising results in phase I and II clinical studies. Early-stage and superficial endobronchial lesions less than 1 cm in thickness can be effectively treated with external light sources. Thicker lesions and peripheral lesions may be amenable to interstitial PDT, where the light is delivered intratumorally. The addition of PDT to standard-of-care surgery and chemotherapy can improve survival and outcomes in patients with pleural disease. Intraoperative PDT has shown promise in the treatment of non–small cell lung cancer with pleural spread. Recent preclinical and clinical data suggest that PDT can increase antitumor immunity. Crosslinking of signal transducer and activator of transcription-3 molecules is a reliable biomarker to quantify the photoreaction induced by PDT. Randomized studies are required to test the prognosis value of this biomarker, obtain approval for the new photosensitizers, and test the potential efficacy of interstitial and intraoperative PDT in the treatment of patients with non–small cell lung cancer.

Keywords: photodynamic therapy, non–small cell lung cancer, intraoperative photodynamic therapy, interstitial photodynamic therapy

Photodynamic therapy (PDT) has been approved for the treatment of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) for more than 15 years (1, 2). In PDT, systemic administration of a light-sensitive drug (i.e., photosensitizer), is followed by illumination of the target tissue with visible light that leads to the generation of reactive oxygen species, notably singlet oxygen (3). This results in the destruction of the tumor by a combination of direct cellular and secondary vascular effects (4). In addition to local tumor ablation, PDT has been shown to enhance antitumor immunity in both preclinical and clinical settings (5–7). PDT can be used as solo therapy or in combination with surgery, chemotherapy, or standard radiation therapy (8–10). The primary indications are for obstructive disease and symptom palliation in patients with tumors that are not eligible for standard surgery and radiation therapy.

Currently, the most commonly used photosensitizer is porfimer sodium (Photofrin; Pinnacle Biologics Inc., Bannockburn, IL). After intravenous injection, porfimer sodium is retained in tumor and to a lesser degree in normal tissue (11). The therapeutic effect is obtained by illuminating the target tumor tissue and margins with activating laser light with 630 ± 3 nm wavelength, about 48 hours after photosensitizer administration (12–14). The light is transmitted through optical fibers with either a lens or a cylindrical diffuser (CD) end for superficial or circumferential illumination, respectively. The procedure is usually performed with flexible bronchoscopy under moderate sedation and topical anesthesia to prevent coughing. Rigid bronchoscopy under general anesthesia is reserved for patients with marginal lung function to prevent hypoxia or in those requiring a prolonged procedure. This is followed by a repeat bronchoscopy in 2 days to remove any tissue debris and retained secretions distal to the lesion, which is often inflamed as a consequence of the cytotoxic reaction.

In the case of porfimer sodium illumination, additional illumination can be performed within 6 to 7 days for any residual tumor, when the photosensitizer concentration is still in the therapeutic range. It should be emphasized that when PDT is used to achieve complete pathological response, the extent of the tumor should be mapped and any synchronous airway lesion should be confirmed or excluded before the procedure. This is done by endobronchial ultrasonography and bronchoscopy (13, 14).

The major complications of PDT with porfimer sodium are photosensitivity and hypoxia. The photosensitivity usually lasts for 4 to 6 weeks. During that time, the patients are instructed to use sunglasses and cover the skin when exposed to direct sunlight or bright indoor light. Patients are also instructed to expose their skin to ambient indoor light, to allow for a slow and controlled photobleaching of the porfimer sodium. After PDT treatment, hypoxia may result from tissue debris and retained secretions within the first 24 to 48 hours after illumination, when the airway narrowing or obstruction caused by inflammation and associated edema is greatest (12, 13). A follow-up bronchoscopy is performed as soon as manifestations of bronchial obstruction emerge.

Several groups reviewed the use of PDT in the treatment of lung cancer. Recently, Simone and Cengel published a review paper on the mechanism of and rationale for using PDT to treat lung cancer and malignant pleural mesothelioma (15). An earlier review by Simone and colleagues focused on the use of PDT in the treatment of roentgenographically occult, early-stage, and endobronchial NSCLC (16). Ernst and LoCicero published a review paper that provides a short summary on the use of PDT in the treatment of lung cancer (14). Kato reported the experience of a single center in the use of PDT and photodiagnosis in Japan (17). Allison and colleagues described the mechanism of action of PDT and different photosensitizers and light sources in the treatment of head and neck, lung, gynecological, gastrointestinal, and genitourinary cancer (18). Chen and colleagues reviewed the use of PDT in unresectable esophageal and lung cancer (19). Loewen and colleagues reviewed the use of porfimer sodium and 2-[1-hexyloxyethyl]-2 devinyl pyropheophorbide-a (HPPH) in the treatment of early-stage lung cancer and reported early results with HPPH (20). Banerjee and George reviewed the use of bronchoscopy in photodynamic diagnosis and therapy in lung cancer (21).

This review is tightly focused on palliative and curative PDT in lung cancer. It highlights a new technique for interstitial PDT, examines a new approach for targeted PDT in lung cancer, and includes a description of a promising biomarker for quantifying PDT-induced photoreaction. It presents the principles that can allow the use of PDT in combination with new immunotherapies. The overall objective of this focused review paper is to offer new perspectives for the use of PDT in the treatment of NSCLC.

Current Indications for PDT

In palliative settings, PDT effectively reduces airway obstruction and improves respiratory function (22–26). One retrospective study that included 529 operations on 133 patients reported that PDT is safe and effective in the treatment of bleeding tumors that block the tracheobronchial tree, in particular (22). These researchers reported that PDT was effective even in severely debilitated patients with profound shortness of breath from advanced malignancy who failed conventional core-out or laser treatments. A pilot study, using PDT with hyperbaric oxygen for enhanced oxygen-dependent tumor lysis, demonstrated a significant improvement in controlling bleeding and obstructive symptoms (27, 28).

In the last 10 years, several clinical studies yielded encouraging results in the treatment of locally advanced NSCLC with airway obstruction. Weinberg and colleagues combined porfimer sodium–mediated PDT with high-dose-rate brachytherapy and obtained local tumor control in 78% (29). Ross and colleagues performed porfimer sodium–mediated PDT as additional induction modality alone or in combination with chemotherapy and/or radiation. They achieved partial response in 100%, and down-staging for surgery was possible in 54% (30). No specific explanation was provided for the rationale and sequence of this multimodality approach. Akopov and his team demonstrated that preoperative induction PDT combined with neoadjuvant chemotherapy and additional intraoperative PDT of the resection margins can be beneficial in the treatment of advanced stages of NSCLC using Radachlorin as photosensitizer (31, 32). Ji and colleagues reported that PDT with Radachlorin as solo therapy can induce complete response in 20% of the cases and partial response in 70% of the cases (33).

Other studies reported that PDT can effectively reduce tumor size of inoperable tumors to make them operable or allow the treating physician to change the intended pneumonectomies to lesser anatomical lung resections (34–36). In a prospective randomized study in 42 patients with stage IIIA and IIIB disease, the efficacy and safety of PDT with chlorin e6 in combination with standard chemotherapy was compared with that of chemotherapy alone (37). The results of this study suggest that neoadjuvant PDT is safe and effective in converting inoperable into operable tumors and that neoadjuvant PDT can improve the completion of surgical resection in patients with stage III NSCLC.

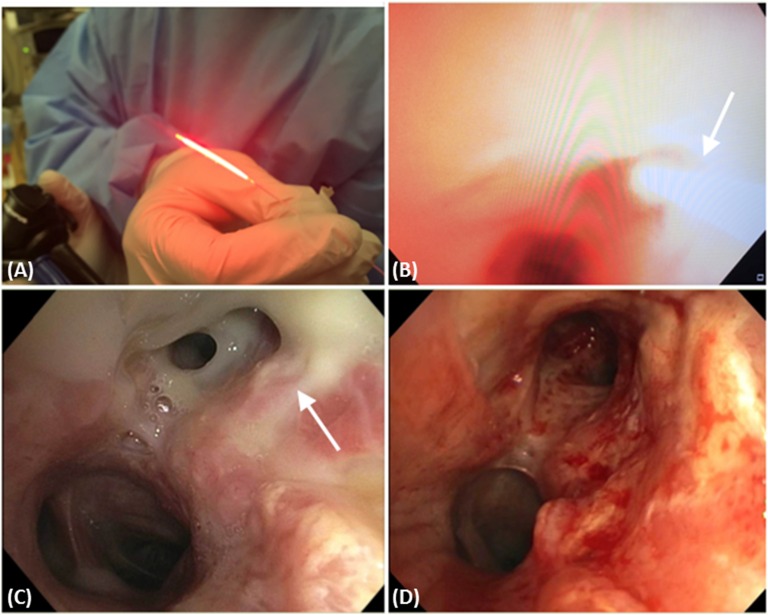

Although surgical resection remains the standard treatment in early-stage NSCLC, PDT is also used with curative intent in patients with centrally located early-stage NSCLC (without cartilage involvement), either occult or overt on currently available imaging (15). The occult lesions are usually detected on screening sputum cytology in high-risk groups and subsequently confirmed by bronchoscopy. In Figure 1 we show typical bronchoscopic images during and after PDT of carcinoma in situ in the left upper lobe and distal left main stem. This patient was successfully treated with PDT using 1 mg/kg porfimer sodium and 630-nm laser light delivered through CD at 400 mW/cm for 500 seconds to administer 200 J/cm.

Figure 1.

(A) An optical fiber with 20-mm cylindrical diffuser end (Optiguide Fiber Optic; CuraScript/Pinnacle Biologics, Chicago, IL). (B) This bronchoscopic image shows the photodynamic therapy (PDT) catheter (arrow) during illumination of the left upper lobe and distal left main stem to treat the carcinoma in situ. (C) Bronchoscopic image showing the mucus sloughing of the distal left main stem and the left upper lobe (arrow) 2 days post PDT. (D) Bronchoscopic image showing the distal left main stem and left upper lobe 4 weeks post PDT.

PDT was also used in the treatment of early-stage NSCLC in patients who were otherwise fit enough for surgical resection (13). Ono and colleagues demonstrated an impressive safety profile of PDT in 30 patients with roentgenographically occult lung cancer who did not experience any major treatment complications (38). In another study, a complete response was seen in 100% of 33 patients with roentgenographically occult lesions 1 cm or smaller, whereas only 38% of lesions with larger than 1 cm diameter had complete remission (39). Imamura and colleagues used PDT with porfimer sodium to treat 29 patients with 39 roentgenographically occult lesions of less than 1 cm (40). Complete response was much higher in superficially infiltrative lesions (76%) than in nodular lesions (43%). Disease recurrence was seen in 23% of patients, and the 5-year survival rate was 56%. In a very similar later study by Endo and colleagues, with 48 patients, the complete response was as high as 94%, and the 5-year and 10-year survival rates were 81 and 71%, respectively (41).

The response to PDT of more infiltrative and larger early-stage lesions is not as impressive as that of roentgenographically occult lesions less than or equal to 1 cm. A Mayo Clinic study on 10 patients achieved complete response only in the lesions with invasion depth of less than 5 mm (42). Later, as an expansion of the same study, complete response was seen only in 48% of lesions with surface area of 3 cm2 or less (43). In another study from the Mayo Clinic, PDT was used in 21 patients with early-stage lung cancer who had declined surgical resection. Complete response was observed in 70% of lesions, and 48% of patients required subsequent surgery for incomplete response, recurrence, or second primary (44). A number of other studies have demonstrated similar pathological response and safety profile for PDT in early-stage lesions larger than 1 cm (45–48).

PDT for centrally located early lung cancer has shown promise in several clinical studies. Furukawa and colleagues reported complete response in 92.8% for lesions that were less than 1 cm in thickness and 58.1% response in thicker lesions, in a study that included 93 patients (49). Moghissi and colleagues reported complete response in 100% of their patients treated with porfimer sodium PDT (50). Corti and colleagues, in 40 patients, used two different photosensitizers, porfimer sodium II and hematoporphyrin derivative, and reported complete and partial response of 72 and 20%, respectively (51). Usuda and colleagues conducted three studies using talaporfin sodium as sole photosensitizer. They obtained complete response rates ranging from 90.4 to 100% (52–54).

In the past 10 years, a total of 493 patients participated in prospective clinical studies that evaluated and validated the benefit of PDT, with different photosensitizers, in the treatment of early-stage (n = 370) and advanced (n=123) NSCLC as detailed in Tables 1 and 2. The complete response for early-stage disease ranged from 72% to an impressive 94% and 100% (Table 1). In the case of advanced disease, the range of local control and partial response was reported to vary from 78 to 100%, respectively (Table 2).

Table 1.

Photodynamic therapy studies for early-stage non-small cell lung cancer in the last 10 years

| Publication | Indication | Photosensitizer | No. of Patients | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Furukawa et al., 2005 (49) | CLELC | Porfimer sodium | 93 | CR: 92.8%/58.1% (less/greater than 1-cm lesion) |

| Corti et al., 2007 (51) | CLELC | Porfimer sodium II (50%), hematoporphyrin derivative (50%) | 40 | CR: 72%, PR: 20%, NR: 6% |

| Usuda et al., 2007 (52) | CLELC | Talaporfin sodium | 29 | CR: 92.1%, PR: 7.9% |

| Moghissi et al., 2007 (50) | CLELC | Porfimer sodium | 21 | CR: 100% |

| Endo et al., 2009 (41) | CLELC | Porfimer sodium | 48 | CR: 94% |

| Usuda et al., 2010 (54) | CLELC | Talaporfin sodium | 75 | CR: 94%/90.4% (less/greater than 1-cm lesion) |

| Usuda et al., 2010 (53) | CLELC | Talaporfin sodium | 64 | CR: 100% |

Definition of abbreviations: CLELC = centrally located early lung cancer; CR = complete response; NR = no response; PR = partial response.

Table 2.

Photodynamic therapy studies for advanced non-small cell lung cancer in the last 10 years

| Publication | Indication | Photosensitizer | No. of Patients | Outcome | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ross et al., 2006 (30) | IIA–IIIB | Porfimer sodium | 41 | PR: 100% | Induction PDT: PDT alone, PDT with Chemo and/or RT followed by surgery |

| Weinberg et al., 2010 (29) | IA, IIA, III, IV | Porfimer sodium | 9 | Local tumor control: 78% | Combined PDT and HDR |

| Ji et al., 2013 (33) | IIIA | Radachlorin | 10 | CR: 20%, PR: 70% | PDT as unique treatment modality |

| Akopov et al., 2013 (32) | IIIA and IIIB | Radachlorin | 20 | PR: 100% | Induction PDT with Chemo, followed by surgery and intraoperative PDT of the resection margins |

| Akopov et al., 2013 (31) | II–III | Radachlorin | 22 | PR: 95% | Induction PDT with Chemo, followed by surgery and intraoperative PDT of the resection margins |

| Akopov et al., 2014 (37) | IIIA and IIIB | Radachlorin | 21 | PR: 90%/76% (with/without PDT) | Prospective randomized study: Induction Chemo with PDT compared with Chemo alone, followed by surgery |

Definition of abbreviations: CR = complete response; Chemo = chemotherapy; HDR = high-dose-rate brachytherapy; PDT = photodynamic therapy; PR = partial response; RT = radiotherapy.

Targeted and Low-Phototoxicity Photosensitizers

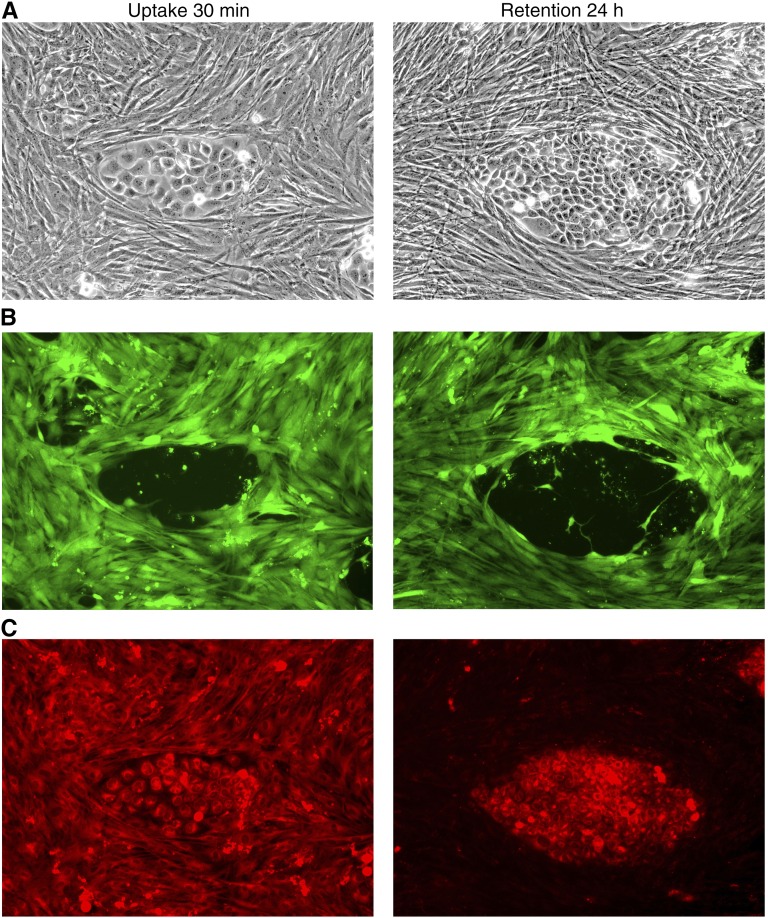

Although PDT with the approved drug porfimer sodium is highly effective, the persistence of the photosensitizer in skin and the associated photosensitization necessitates prolonged complete protection from bright light. HPPH was identified as a photosensitizer with reduced phototoxicity and promising clinical outcomes (20, 55–57). HPPH has been shown to be specifically retained by tumor cells as compared with stromal fibroblastic cells. This feature is demonstrated in Figure 2, by the example of a reconstituted coculture of cells derived from lung squamous carcinoma (58). The enhanced loss of HPPH from stromal cells is probably the main reason for the relatively short-time photosensitivity (7–14 d) of HPPH, in comparison to porfimer sodium.

Figure 2.

Tumor epithelial cells were isolated and enriched by proliferation under selective culture conditions in vitro. (A) Phase contrast image of tumor cell and fibroblast (×100). (B) Fluorescence image of the fibroblast stained with carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester dye. (C) Fluorescence image of the 2-[1-hexyloxyethyl]-2 devinyl pyropheophorbide-a. The image on the right shows preferential retention of this photosensitizer 24 hours after the initial exposure.

Other second-generation photosensitizers, like temoporfin (Foscan), talaporfin sodium, and chlorin e6, have been explored for PDT of NSCLC (37, 54, 59, 60). All of these are associated with short-time photosensitivity (2–14 d). In two phase II studies involving 41 and 75 patients, respectively, talaporfin sodium was used to treat early-stage central superficial tumors 2 cm or smaller, with promising results. In the first study, 85% of patients achieved complete response, and in the second study, complete response rates were 94% for lesions 1 cm or smaller and 90% for lesions larger than 1 cm (54, 60).

Intraoperative PDT

Local recurrence of NSCLC remains a significant problem despite modest improvement in survival from adjuvant chemotherapy (61). The rate of recurrence increases with higher tumor, nodal, or overall pathologic stage (62–64). It has been postulated that the presence of microscopic residual disease after surgical resections is a significant cause for local recurrence that will decrease survival of patients (65–67). One possible solution is the use of intraoperative PDT, where the margins in the surgical bed are illuminated before wound closure to treat undetected viable cancer cells, which could lead to a reduction in local recurrence (68, 69). Several studies reported that intraoperative PDT with porfimer sodium or temoporfin (Foscan) can potentially improve survival of patients with malignant pleural mesothelioma (59, 68, 69).

Outcomes from small phase I and II studies demonstrated that intraoperative PDT can result in median survival of 31.7 to 41.2 months in patients with malignant mesothelioma, who typically have median survival of about 12 months (15, 70). In a phase II study on 22 patients with cT4 NSCLC and pleural spread, intraoperative hemithoracic pleural PDT using porfimer sodium was used after partial or complete tumor debulking. Statistical analysis revealed a 73.3% local control rate at 6 months and overall median survival of 21.7 months (69). A very recent retrospective study evaluated the benefit of adding intraoperative PDT in the treatment of patients with thymoma and those with pleural spread of NSCLC (71). This study compared the mean survival of 51 patients who underwent surgery and chemotherapy to 18 who received intraoperative PDT with porfimer sodium, in addition to these standard therapies. It was found that the mean survival of the PDT group was 39 versus 17.6 months of the standard therapy group. Thus, intraoperative PDT has shown promise in improving survival in patients who can undergo a macroscopically complete resection in a lung-sparing procedure.

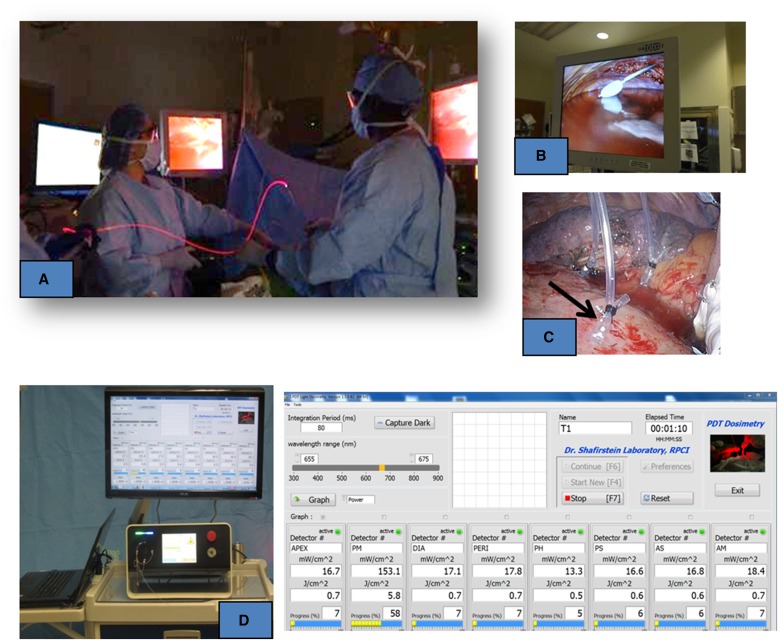

Our research group is currently evaluating the potential benefit of intraoperative temoporfin PDT in patients with resectable primary NSCLC with ipsilateral thoracic nodal (N1 or N2) or T3/T4 disease (NCT 01854684). In this pilot study, after the surgical removal of the primary tumor and immediately before PDT, detection fibers are placed within the cavity (Figure 3). Before illumination, warm saline is poured into the pleural cavity, to match the refractive index of the optical fiber and tissue. A therapeutic red light is delivered to the thoracic cavity with an optical fiber sheathed within a balloon device (CDB-30; Medlight SA, Ecublens, Switzerland) inflated with sterile saline (Figure 3B). The light dose is measured with isotropic detectors that are placed in the thoracic cavity (Figures 3C and 3D). A total of five subjects were treated with low-dose temoporfin (0.04 mg/kg) at 10 J/cm2 with no serious adverse events.

Figure 3.

(A) Procedure involving light illumination of the thoracic cavity during intraoperative photodynamic therapy (PDT). (B) Balloon device used to deliver diffused laser light within the cavity. Although this is a therapeutic red light, the high intensity is shown as bright white light. (C) The isotropic probes (arrow) in a transparent tube secured with a suture within the cavity, before PDT. (D) Portable laser and light dosimetry system. Each detector is marked with its location, in this exemplary case (from left to right): Apex, posterior mediastinum (PM), pericardium (PERI), diaphragm (DIA), pulmonary hilum (PH), posterior diaphragmatic sulcus (PS), anterior diaphragmatic sulcus (AS), anterior mediastinum (AM).

Interstitial PDT

If PDT is to be used for deep-seated and large tumors (>1 cm), interstitial PDT (I-PDT) is necessary (72). The laser fiber is inserted into the tumor through a needle or a catheter that was placed under computed tomography (CT) or ultrasound imaging guidance. The light is delivered from the diffuse tip of a CD. Typically, multiple CD fibers are used to illuminate the target tumor (72). The number and location of the CDs depends on the tumor size and location. Image-based pretreatment planning is often used to determine how many CDs are needed for complete and safe illumination of the clinical target volume (73–75). Recent advancements in computer simulations enable near real-time planning and dosimetry (74–79).

It is conceivable that I-PDT would be suitable for the treatment of locally advanced and large NSCLC. One pilot study in Japan included nine patients with peripheral lung tumors treated with I-PDT through catheters placed percutaneously under CT guidance (80). Depending on tumor size, up to six catheters were placed into the tumor. In large tumors, more than one I-PDT session was conducted. All patients underwent histological assessment at 1 and 4 weeks post therapy using CT-guided needle biopsy and/or brush cytology. Seven of the nine patients (78%) demonstrated partial response, and no patient had progressive disease at 4 weeks. Two of the nine patients developed pneumothorax, with one patient requiring chest tube placement.

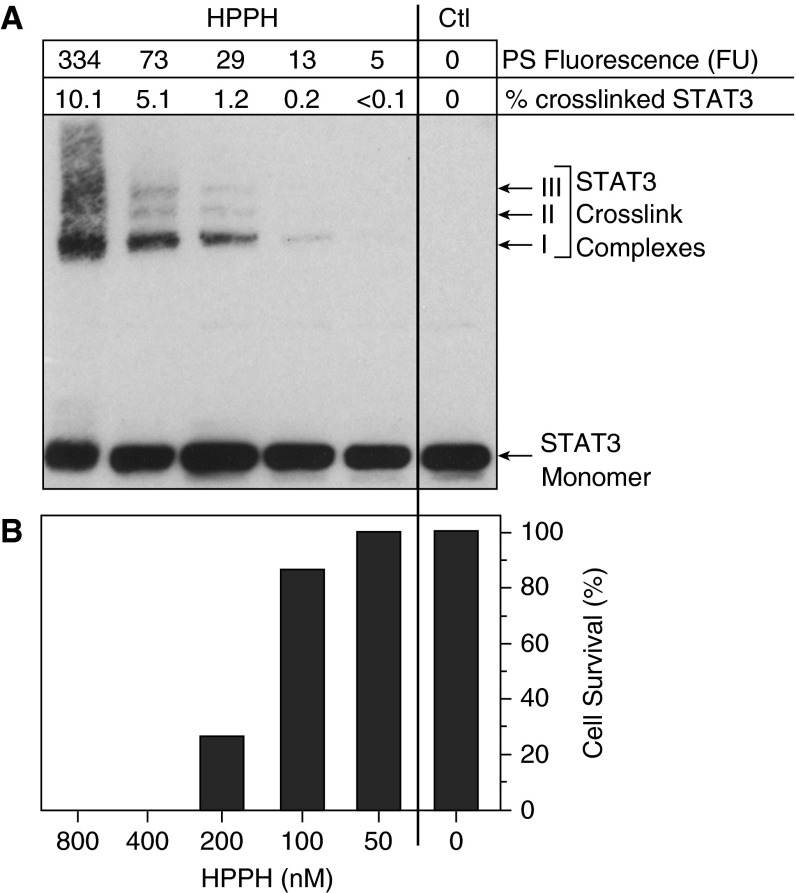

Biomarkers for Quantifying Photoreaction

Significant efforts have been made to find a biomarker for the early PDT response. Several preclinical and clinical studies, at our institution, have shown that covalent homodimeric crosslinking of signal transducer and activator of transcription-3 (STAT3) is highly sensitive and proportional to the photosensitizer-mediated photoreaction (56, 81, 82). The photosensitizer-dependent photoreaction produces singlet oxygen and other reactive oxygen species, which oxidize cellular substrates such as lipids and proteins. The photoreaction results in a proportional formation of cross-linked proteins with a particularly high specificity for STAT3 (82). The fact that all cells of the body contain approximately the same amount of STAT3 renders its PDT-dependent crosslinking to be a universal marker for the photoreaction achieved during PDT. The assay must be performed on tissue collected from the treatment site immediately after PDT. The tissue can be fresh or snap frozen. This rather standard assay can be completed within 24 hours post PDT. It has the potential to assist physicians in evaluating the response to PDT early enough to consider other options. However, more prospective studies are required to test the prognosis value of this biomarker.

In a recent clinical study in using PDT to treat early-stage oral cancer, we detected STAT3 dimers only in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma biopsies collected immediately after PDT (56). A threshold level of 10% STAT3 crosslinking appeared to be associated with an effective and durable response of SCC to HPPH-PDT (56). In Figure 4 we present preliminarily results for the degree of STAT3 crosslink as a function of HPPH-mediated PDT in lung cancer cells. These data are in agreement with a report from another group (83), and demonstrate that STAT3 crosslinking may be used to detect photoreaction and the response to PDT treatment within 24 hours (56, 82).

Figure 4.

Response of TEC-1-2 lung tumor epithelial cells to 2-[1-hexyloxyethyl]-2 devinyl pyropheophorbide-a (HPPH) photodynamic therapy by (A) crosslinking signal transducer and activator of transcription-3 (STAT3), and (B) inducing cell death as measured 24 hours later. Ctl = control; PS = photosensitizer.

PDT and Immune Response

Several studies have demonstrated that PDT can enhance antitumor immunity (5, 6, 84). Early studies conducted by Canti and colleagues (85) and Korbelik and colleagues (86) in murine models showed that mice whose tumors had been ablated by PDT were able to resist subsequent tumor challenge and possessed immunologic memory. Clinical PDT also increases antitumor immunity. PDT of multifocal angiosarcoma of the head and neck resulted in increased immune cell infiltration into distant untreated tumors that was accompanied by tumor regression (87). PDT of basal cell carcinoma increased immune cell reactivity against a basal cell carcinoma–associated antigen (7). Finally, a recent study combining radical lung-sparing pleurectomy with PDT for treatment of malignant mesothelioma indicated that disease recurrence in these patients was more indolent and occurred locally rather than at distant sites (70), leading investigators to speculate on the possibility of PDT-enhanced antitumor immunity.

PDT can activate both humoral and cell-mediated adaptive antitumor immunity (88); however, most studies have shown that enhanced antitumor immunity after PDT is dependent on CD8+ T cells (86). Therefore, the importance of the humoral arm of antitumor immunity after PDT remains unclear, and most mechanistic studies to date have focused on PDT modulation of cell-mediated antitumor immunity. Activation of CD8+ T cells is primarily dependent on dendritic cell maturation and activation. Activated dendritic cells stimulate the differentiation and activation of T cells through expression of antigenic peptide: MHC complexes, costimulatory molecules, and cytokines, resulting in induction of antitumor immunity. PDT results in the maturation and activation of dendritic cells (89) and migration to the draining lymph nodes, where they are believed to stimulate T-cell activation (89, 90). Dendritic cell maturation after PDT is believed to be due in part to recognition of PDT-induced immunologic tumor cell death (88, 91–94).

Interestingly, several studies have suggested that PDT efficacy is dependent, in part, on the presence of an active immune response. Long-term tumor response is diminished or absent in immunocompromised mice (86, 95). Reconstitution of these mouse strains with bone marrow or T cells from immunocompetent mice resulted in increased PDT efficacy. Clinical PDT efficacy also appears to depend on antitumor immunity. Patients with vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia who did not respond to aminolevulinic acid were more likely to have tumors that lacked major histocompatibility complex class I molecules (MHC-I) than patients who responded to aminolevulinic acid (96). MHC-I recognition is critical for activation of CD8+ T cells, and tumors that lack MHC-I are resistant to cell-mediated antitumor immune reactions (97). Patients with vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia who responded to PDT had increased CD8+ T cell infiltration into the treated tumors as compared with nonresponders. Immunosuppressed and immunocompetent patients with actinic keratoses and Bowen disease had similar initial response rates to PDT; however, immunosuppressed patients exhibited greater persistence of disease or appearance of new lesions (98). These studies suggest that combination therapies of PDT and immune-modulating agents could lead to improved overall responses. This hypothesis is supported by recent work showing that epigenetic agents that increase MHC-I expression on tumor cells increase PDT efficacy (99).

In addition to epigenetic mechanisms, antitumor immunity is frequently inhibited in patients with cancer as a result of local immune suppression mediated by suppressive cells and immune checkpoints (100). Suppressive cells include regulatory T cells; preclinical studies have shown that inhibition of regulatory T cells can enhance PDT-induced antitumor immunity and overall efficacy (101). Importantly, blockade of the immune checkpoint (anti–programmed death-1 and one of its ligands) axis has proven to be effective in clinical trials of NSCLC (102–105). Given that checkpoint blockade cannot create tumor-specific T-cell responses in the absence of an existing response, it is logical to assume that therapies that increase tumor-specific T cells will benefit/synergize with checkpoint blockade therapies. The proven ability of PDT to enhance antitumor immunity makes it an ideal therapy to combine with checkpoint blockade therapy. A future challenge will be demonstrating to what extent the PDT of NSCLC will engage the adaptive immune system to control cancer recurrence and whether combination therapies that include PDT and therapeutics targeting immune suppression enhance overall survival of patients.

Summary

Multiple clinical studies have demonstrated that PDT is an effective palliative therapy for relieving airway obstruction from NSCLC. It is effective for eradication of thin (<1 cm) noninvasive endobronchial lesions that are accessible to conventional bronchoscopes. Thicker and deeper lesions will not respond well because of limited light penetration (<1 cm). In these lesions, I-PDT may hold promise. This technique allows delivering light intratumorally; thus, it can be used to treat large tumors. Although feasible, more studies are required to test its safety and efficacy. Pretreatment planning and real-time dosimetry could further improve the administration of I-PDT that can also be used for the treatment of peripheral lung tumors.

PDT can be used in combination with other therapeutic modalities, such as chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and surgery, in the treatment of lung cancer (15). Many clinical studies have shown that PDT may also have a role as a neoadjuvant therapy to reduce the proximal extent of tumors and the management of malignant pleural effusions from NSCLC. Therefore, the key indications for the use of PDT in clinical care for palliation of NSCLC are: locally advanced and peripheral tumors, pleural disease, and margins control. The key indications for the use of PDT for definitive treatment of NSCLC include: early stage, superficial, and centrally located endobronchial tumors. The palliative and definitive indications are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Key indications of photodynamic therapy in the treatment of lung cancer

| Indication | Suggested PDT Procedure |

|---|---|

| Palliative | |

| Locally advanced and peripheral tumors | Interstitial PDT using image guidance and treatment planning. |

| Pleural disease and margin control | Intraoperative PDT by transthoracic or thoracoscopic irradiation after tumor resection and complete removal of the macroscopic disease. |

| Definitive | |

| Early stage, superficial, and centrally located endobronchial NSCLC tumors | Bronchoscopic irradiation with lesser phototoxicity using new efficient photosensitizers |

Definition of abbreviations: NSCLC non-small cell lung cancer; PDT = photodynamic therapy.

Phototoxicity is the main side effect limiting the widespread clinical acceptability of PDT. Introduction of second-generation photosensitizers, such as temoporfin, HPPH, and chlorin e6, has decreased the duration of light avoidance for patients light from 40 to 60 days to 14, 7, or 1 to 2 days, respectively. Another limiting factor in the use of PDT is the need to wait 24 to 96 hours from the time of the photosensitizer administration to the laser light illumination, also known as drug–light interval. This obstacle may be minimized with the use of vascular-targeted photosensitizer (e.g., chlorin e6) that reduces the drug–light interval to 3 hours, which has shown promise in the treatment of NSCLC.

Recent preclinical and clinical data suggest that PDT effectively triggers the immune response to obtain distant control of a metastatic cancer. It has been postulated that the immune response may be responsible for the improved outcomes of patients with mesothelioma after intraoperative PDT (15). This approach could be used to develop new PDT regimens in the treatment of metastatic lung cancer in combination with checkpoint blockade (such as the PD-1 axis), which have shown promise in patients with advanced-stage NSCLC (106).

Preclinical and clinical studies demonstrated that the degree of crosslinking of STAT3 molecules is a reliable biomarker to quantify the PDT-induced photoreaction. Additional prospective studies will have to confirm that STAT3 crosslinking is a reliable marker for the early PDT response. Multicenter randomized clinical studies are required to support new indications for the use of these new photosensitizers in the treatment of lung cancer.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Dr. Barbara Henderson for her critical review of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Supported in part by National Cancer Institute grants PO1CA55791 and P30CA16056.

The views expressed in this article do not communicate an official position of Roswell Park Cancer Institute or the Medical University Graz.

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Dougherty TJ, Gomer CJ, Henderson BW, Jori G, Kessel D, Korbelik M, Moan J, Peng Q. Photodynamic therapy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998;90:889–905. doi: 10.1093/jnci/90.12.889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kato H, Harada M, Ichinose S, Usuda J, Tsuchida T, Okunaka T. Photodynamic therapy (PDT) of lung cancer: experience of the Tokyo Medical University. Photodiagn Photodyn Ther. 2004;1:49–55. doi: 10.1016/S1572-1000(04)00008-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Henderson BW, Dougherty TJ. How does photodynamic therapy work? Photochem Photobiol. 1992;55:145–157. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1992.tb04222.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krammer B. Vascular effects of photodynamic therapy. Anticancer Res. 2001;21:4271–4277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Agostinis P, Berg K, Cengel KA, Foster TH, Girotti AW, Gollnick SO, Hahn SM, Hamblin MR, Juzeniene A, Kessel D, et al. Photodynamic therapy of cancer: an update. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:250–281. doi: 10.3322/caac.20114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brackett CM, Gollnick SO. Photodynamic therapy enhancement of anti-tumor immunity. Photochem Photobiol Sci. 2011;10:649–652. doi: 10.1039/c0pp00354a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kabingu E, Oseroff AR, Wilding GE, Gollnick SO. Enhanced systemic immune reactivity to a Basal cell carcinoma associated antigen following photodynamic therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:4460–4466. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bown SG, Rogowska AZ, Whitelaw DE, Lees WR, Lovat LB, Ripley P, Jones L, Wyld P, Gillams A, Hatfield AW. Photodynamic therapy for cancer of the pancreas. Gut. 2002;50:549–557. doi: 10.1136/gut.50.4.549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zimmermann A, Ritsch-Marte M, Kostron H. mTHPC-mediated photodynamic diagnosis of malignant brain tumors. Photochem Photobiol. 2001;74:611–616. doi: 10.1562/0031-8655(2001)074<0611:MMPDOM>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rigual NR, Shafirstein G, Frustino J, Seshadri M, Cooper M, Wilding G, Sullivan MA, Henderson B. Adjuvant intraoperative photodynamic therapy in head and neck cancer. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;139:706–711. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2013.3387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Doiron DR, Profio E, Vincent RG, Dougherty TJ. Fluorescence bronchoscopy for detection of lung cancer. Chest. 1979;76:27–32. doi: 10.1378/chest.76.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee P, Kupeli E, Mehta AC. Therapeutic bronchoscopy in lung cancer: laser therapy, electrocautery, brachytherapy, stents, and photodynamic therapy. Clin Chest Med. 2002;23:241–256. doi: 10.1016/s0272-5231(03)00075-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vergnon JM, Huber RM, Moghissi K. Place of cryotherapy, brachytherapy and photodynamic therapy in therapeutic bronchoscopy of lung cancers. Eur Respir J. 2006;28:200–218. doi: 10.1183/09031936.06.00014006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ernst A, LoCicero J III. UpToDate. 2014. Photodynamic therapy of lung cancer. [accessed 2016 Jan 15; updated 2014 Jan 9]. Available from: http://www.uptodate.com/contents/photodynamic-therapy-of-lung-cancer. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Simone CB, II, Cengel KA. Photodynamic therapy for lung cancer and malignant pleural mesothelioma. Semin Oncol. 2014;41:820–830. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2014.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Simone CB, II, Friedberg JS, Glatstein E, Stevenson JP, Sterman DH, Hahn SM, Cengel KA. Photodynamic therapy for the treatment of non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Dis. 2012;4:63–75. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2011.11.05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kato H. Our experience with photodynamic diagnosis and photodynamic therapy for lung cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2012;10:S3–S8. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2012.0170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Allison R, Moghissi K, Downie G, Dixon K. Photodynamic therapy (PDT) for lung cancer. Photodiagn Photodyn Ther. 2011;8:231–239. doi: 10.1016/j.pdpdt.2011.03.342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen M, Pennathur A, Luketich JD. Role of photodynamic therapy in unresectable esophageal and lung cancer. Lasers Surg Med. 2006;38:396–402. doi: 10.1002/lsm.20364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Loewen GM, Pandey R, Bellnier D, Henderson B, Dougherty T. Endobronchial photodynamic therapy for lung cancer. Lasers Surg Med. 2006;38:364–370. doi: 10.1002/lsm.20354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Banerjee A, George J. Bronchoscopic photodynamic diagnosis and therapy for lung cancer. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2000;6:378–383. doi: 10.1097/00063198-200007000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Minnich DJ, Bryant AS, Dooley A, Cerfolio RJ.Photodynamic laser therapy for lesions in the airway Ann Thorac Surg 2010891744–1748.[Discussion pp. 1748–1749.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jones BU, Helmy M, Brenner M, Serna DL, Williams J, Chen JC, Milliken JC. Photodynamic therapy for patients with advanced non-small-cell carcinoma of the lung. Clin Lung Cancer. 2001;3:37–41, discussion 42. doi: 10.3816/clc.2001.n.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Iaitskiĭ NA, Gerasin VA, Orlov SV, Butenko AB, Molodtsova VP, Derevianko AV, Stel’makh LV, Urtenova MA, Gerasin AV. Photodynamic therapy in treatment of lung cancer [in Russian] Vestn Khir Im I I Grek. 2010;169:31–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moghissi K, Dixon K, Stringer M, Freeman T, Thorpe A, Brown S. The place of bronchoscopic photodynamic therapy in advanced unresectable lung cancer: experience of 100 cases. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 1999;15:1–6. doi: 10.1016/s1010-7940(98)00295-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.LoCicero J, III, Metzdorff M, Almgren C. Photodynamic therapy in the palliation of late stage obstructing non-small cell lung cancer. Chest. 1990;98:97–100. doi: 10.1378/chest.98.1.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tomaselli F, Maier A, Pinter H, Stranzl H, Smolle-Jüttner FM. Photodynamic therapy enhanced by hyperbaric oxygen in acute endoluminal palliation of malignant bronchial stenosis (clinical pilot study in 40 patients) Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2001;19:549–554. doi: 10.1016/s1010-7940(01)00635-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tomaselli F, Maier A, Sankin O, Anegg U, Stranzl U, Pinter H, Kapp K, Smolle-Jüttner FM. Acute effects of combined photodynamic therapy and hyperbaric oxygenation in lung cancer: a clinical pilot study. Lasers Surg Med. 2001;28:399–403. doi: 10.1002/lsm.1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weinberg BD, Allison RR, Sibata C, Parent T, Downie G. Results of combined photodynamic therapy (PDT) and high dose rate brachytherapy (HDR) in treatment of obstructive endobronchial non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) Photodiagn Photodyn Ther. 2010;7:50–58. doi: 10.1016/j.pdpdt.2009.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ross P, Jr, Grecula J, Bekaii-Saab T, Villalona-Calero M, Otterson G, Magro C. Incorporation of photodynamic therapy as an induction modality in non-small cell lung cancer. Lasers Surg Med. 2006;38:881–889. doi: 10.1002/lsm.20444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Akopov AL, Rusanov AA, Chistiakov IV, Urtenova MA, Kazakov NV, Gerasin AV, Papaian GV. Application of photodynamic therapy to reduce the amount of resection for non-small cell lung cancer [in Russian] Vopr Onkol. 2013;59:740–744. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Akopov AL, Rusanov AA, Molodtsova VP, Chistiakov IV, Kazakov NV, Urtenova MA, Rait M, Papaian GV. Photodynamic therapy in combined treatment of stage III non-small cell lung carcinoma [in Russian] Khirurgiia (Mosk) 2013;3:17–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ji W, Yoo JW, Bae EK, Lee JH, Choi CM. The effect of Radachlorin® PDT in advanced NSCLC: a pilot study. Photodiagn Photodyn Ther. 2013;10:120–126. doi: 10.1016/j.pdpdt.2013.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Okunaka T, Hiyoshi T, Furukawa K, Yamamoto H, Tsuchida T, Usuda J, Kumasaka H, Ishida J, Konaka C, Kato H. Lung cancers treated with photodynamic therapy and surgery. Diagn Ther Endosc. 1999;5:155–160. doi: 10.1155/DTE.5.155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Arsen’ev AI, Kanaev SV, Barchuk AS, Vedenin IaO, Klitenko VN, Gel’fond ML, Shulenov AV, Morozova IuA, Barchuk AA, Tarkov SA. Use of endotracheobronchial surgery in conjunction with radiochemotherapy for advanced non-small lung cancer [in Russian] Vopr Onkol. 2007;53:461–467. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Konaka C, Usuda J, Kato H. Preoperative photodynamic therapy for lung cancer [in Japanese] Nippon Geka Gakkai Zasshi. 2000;101:486–489. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Akopov A, Rusanov A, Gerasin A, Kazakov N, Urtenova M, Chistyakov I. Preoperative endobronchial photodynamic therapy improves resectability in initially irresectable (inoperable) locally advanced non small cell lung cancer. Photodiagn Photodyn Ther. 2014;11:259–264. doi: 10.1016/j.pdpdt.2014.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ono R, Ikeda S, Suemasu K. Hematoporphyrin derivative photodynamic therapy in roentgenographically occult carcinoma of the tracheobronchial tree. Cancer. 1992;69:1696–1701. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19920401)69:7<1696::aid-cncr2820690709>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Furuse K, Okunaka T, Sakai H, Konaka C, Kato H, Aoki M, Wada H, Nakamura S, Horai T, Kubota K, et al. Photodynamic therapy (PDT) in roentgenographically occult lung cancer by photofrin II and excimer dye laser [in Japanese] Gan To Kagaku Ryoho. 1993;20:1369–1374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Imamura S, Kusunoki Y, Takifuji N, Kudo S, Matsui K, Masuda N, Takada M, Negoro S, Ryu S, Fukuoka M. Photodynamic therapy and/or external beam radiation therapy for roentgenologically occult lung cancer. Cancer. 1994;73:1608–1614. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19940315)73:6<1608::aid-cncr2820730611>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Endo C, Miyamoto A, Sakurada A, Aikawa H, Sagawa M, Sato M, Saito Y, Kondo T. Results of long-term follow-up of photodynamic therapy for roentgenographically occult bronchogenic squamous cell carcinoma. Chest. 2009;136:369–375. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-2237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cortese DA, Kinsey JH. Hematoporphyrin-derivative phototherapy for local treatment of cancer of the tracheobronchial tree. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1982;91:652–655. doi: 10.1177/000348948209100628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Edell ES, Cortese DA. Bronchoscopic phototherapy with hematoporphyrin derivative for treatment of localized bronchogenic carcinoma: a 5-year experience. Mayo Clin Proc. 1987;62:8–14. doi: 10.1016/s0025-6196(12)61520-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cortese DA, Edell ES, Kinsey JH. Photodynamic therapy for early stage squamous cell carcinoma of the lung. Mayo Clin Proc. 1997;72:595–602. doi: 10.1016/S0025-6196(11)63563-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McCaughan JS, Jr, Williams TE. Photodynamic therapy for endobronchial malignant disease: a prospective fourteen-year study. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1997;114:940–946. [Discussion pp. 946–947.]. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5223(97)70008-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li JH, Chen YP, Zhao SD, Zhang LT, Song SZ. Application of hematoporphyrin derivative and laser-induced photodynamical reaction in the treatment of lung cancer: a preliminary report on 21 cases. Lasers Surg Med. 1984;4:31–37. doi: 10.1002/lsm.1900040105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Furuse K, Fukuoka M, Kato H, Horai T, Kubota K, Kodama N, Kusunoki Y, Takifuji N, Okunaka T, Konaka C, et al. The Japan Lung Cancer Photodynamic Therapy Study Group. A prospective phase II study on photodynamic therapy with photofrin II for centrally located early-stage lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1993;11:1852–1857. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1993.11.10.1852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liang YM, Tu QX, Liu GY, Zhang XS. Short term result of lung cancer treated by photodynamic therapy (PDT) [in Chinese] Zhonghua Zhong Liu Za Zhi. 1987;9:50–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Furukawa K, Kato H, Konaka C, Okunaka T, Usuda J, Ebihara Y. Locally recurrent central-type early stage lung cancer < 1.0 cm in diameter after complete remission by photodynamic therapy. Chest. 2005;128:3269–3275. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.5.3269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Moghissi K, Dixon K, Thorpe JA, Stringer M, Oxtoby C. Photodynamic therapy (PDT) in early central lung cancer: a treatment option for patients ineligible for surgical resection. Thorax. 2007;62:391–395. doi: 10.1136/thx.2006.061143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Corti L, Toniolo L, Boso C, Colaut F, Fiore D, Muzzio PC, Koukourakis MI, Mazzarotto R, Pignataro M, Loreggian L, et al. Long-term survival of patients treated with photodynamic therapy for carcinoma in situ and early non-small-cell lung carcinoma. Lasers Surg Med. 2007;39:394–402. doi: 10.1002/lsm.20513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Usuda J, Tsutsui H, Honda H, Ichinose S, Ishizumi T, Hirata T, Inoue T, Ohtani K, Maehara S, Imai K, et al. Photodynamic therapy for lung cancers based on novel photodynamic diagnosis using talaporfin sodium (NPe6) and autofluorescence bronchoscopy. Lung Cancer. 2007;58:317–323. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2007.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Usuda J, Ichinose S, Ishizumi T, Hayashi H, Ohtani K, Maehara S, Ono S, Kajiwara N, Uchida O, Tsutsui H, et al. Management of multiple primary lung cancer in patients with centrally located early cancer lesions. J Thorac Oncol. 2010;5:62–68. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181c42287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Usuda J, Ichinose S, Ishizumi T, Hayashi H, Ohtani K, Maehara S, Ono S, Honda H, Kajiwara N, Uchida O, et al. Outcome of photodynamic therapy using NPe6 for bronchogenic carcinomas in central airways >1.0 cm in diameter. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:2198–2204. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Henderson BW, Bellnier DA, Greco WR, Sharma A, Pandey RK, Vaughan LA, Weishaupt KR, Dougherty TJ. An in vivo quantitative structure-activity relationship for a congeneric series of pyropheophorbide derivatives as photosensitizers for photodynamic therapy. Cancer Res. 1997;57:4000–4007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rigual N, Shafirstein G, Cooper MT, Baumann H, Bellnier DA, Sunar U, Tracy EC, Rohrbach DJ, Wilding G, Tan W, et al. Photodynamic therapy with 3-(1′-hexyloxyethyl) pyropheophorbide a for cancer of the oral cavity. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:6605–6613. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-1735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bellnier DA, Greco WR, Nava H, Loewen GM, Oseroff AR, Dougherty TJ. Mild skin photosensitivity in cancer patients following injection of Photochlor (2-[1-hexyloxyethyl]-2-devinyl pyropheophorbide-a; HPPH) for photodynamic therapy. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2006;57:40–45. doi: 10.1007/s00280-005-0015-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tracy EC, Bowman MJ, Pandey RK, Henderson BW, Baumann H. Cell-type selective phototoxicity achieved with chlorophyll-a derived photosensitizers in a co-culture system of primary human tumor and normal lung cells. Photochem Photobiol. 2011;87:1405–1418. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.2011.00992.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Friedberg JS, Mick R, Stevenson J, Metz J, Zhu T, Buyske J, Sterman DH, Pass HI, Glatstein E, Hahn SM. A phase I study of Foscan-mediated photodynamic therapy and surgery in patients with mesothelioma. Ann Thorac Surg. 2003;75:952–959. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(02)04474-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kato H, Furukawa K, Sato M, Okunaka T, Kusunoki Y, Kawahara M, Fukuoka M, Miyazawa T, Yana T, Matsui K, et al. Phase II clinical study of photodynamic therapy using mono-L-aspartyl chlorin e6 and diode laser for early superficial squamous cell carcinoma of the lung. Lung Cancer. 2003;42:103–111. doi: 10.1016/s0169-5002(03)00242-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Uramoto H, Tanaka F. Recurrence after surgery in patients with NSCLC. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2014;3:242–249. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2218-6751.2013.12.05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Varlotto JM, Recht A, Flickinger JC, Medford-Davis LN, Dyer AM, Decamp MM. Factors associated with local and distant recurrence and survival in patients with resected nonsmall cell lung cancer. Cancer. 2009;115:1059–1069. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Taylor MD, Nagji AS, Bhamidipati CM, Theodosakis N, Kozower BD, Lau CL, Jones DR. Tumor recurrence after complete resection for non-small cell lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 2012;93:1813–1820. [Discussion pp. 1820–1811.]. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2012.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jang KM, Lee KS, Shim YM, Han D, Kim H, Kwon OJ, Kim J, Kim TS. The rates and CT patterns of locoregional recurrence after resection surgery of lung cancer: correlation with histopathology and tumor staging. J Thorac Imaging. 2003;18:225–230. doi: 10.1097/00005382-200310000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rusch VW, Hawes D, Decker PA, Martin SE, Abati A, Landreneau RJ, Patterson GA, Inculet RI, Jones DR, Malthaner RA, et al. Occult metastases in lymph nodes predict survival in resectable non-small-cell lung cancer: report of the ACOSOG Z0040 trial. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:4313–4319. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.35.2500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Riquet M, Achour K, Foucault C, Le Pimpec Barthes F, Dujon A, Cazes A. Microscopic residual disease after resection for lung cancer: a multifaceted but poor factor of prognosis. Ann Thorac Surg. 2010;89:870–875. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2009.11.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lim E, Clough R, Goldstraw P, Edmonds L, Aokage K, Yoshida J, Nagai K, Shintani Y, Ohta M, Okumura M, et al. International Pleural Lavage Cytology Collaborators. Impact of positive pleural lavage cytology on survival in patients having lung resection for non-small-cell lung cancer: an international individual patient data meta-analysis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010;139:1441–1446. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2009.05.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Baas P, Murrer L, Zoetmulder FA, Stewart FA, Ris HB, van Zandwijk N, Peterse JL, Rutgers EJ. Photodynamic therapy as adjuvant therapy in surgically treated pleural malignancies. Br J Cancer. 1997;76:819–826. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1997.468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Friedberg JS, Mick R, Stevenson JP, Zhu T, Busch TM, Shin D, Smith D, Culligan M, Dimofte A, Glatstein E, et al. Phase II trial of pleural photodynamic therapy and surgery for patients with non-small-cell lung cancer with pleural spread. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:2192–2201. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.07.097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Friedberg JS. Radical pleurectomy and photodynamic therapy for malignant pleural mesothelioma. Ann Cardiothorac Surg. 2012;1:472–480. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2225-319X.2012.11.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chen KC, Hsieh YS, Tseng YF, Shieh MJ, Chen JS, Lai HS, Lee JM. Pleural photodynamic therapy and surgery in lung cancer and thymoma patients with pleural spread. Plos One. 2015;10:e0133230. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0133230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wilson BC, Patterson MS. The physics, biophysics and technology of photodynamic therapy. Phys Med Biol. 2008;53:R61–R109. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/53/9/R01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Karakullukcu B, van Veen RL, Aans JB, Hamming-Vrieze O, Navran A, Teertstra HJ, van den Boom F, Niatsetski Y, Sterenborg HJ, Tan IB. MR and CT based treatment planning for mTHPC mediated interstitial photodynamic therapy of head and neck cancer: description of the method. Lasers Surg Med. 2013;45:517–523. doi: 10.1002/lsm.22174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Swartling J, Axelsson J, Ahlgren G, Kälkner KM, Nilsson S, Svanberg S, Svanberg K, Andersson-Engels S. System for interstitial photodynamic therapy with online dosimetry: first clinical experiences of prostate cancer. J Biomed Opt. 2010;15:058003. doi: 10.1117/1.3495720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Oakley E, Wrazen B, Bellnier DA, Syed Y, Arshad H, Shafirstein G. A new finite element approach for near real-time simulation of light propagation in locally advanced head and neck tumors. Lasers Surg Med. 2015;47:60–67. doi: 10.1002/lsm.22313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Du KL, Mick R, Busch TM, Zhu TC, Finlay JC, Yu G, Yodh AG, Malkowicz SB, Smith D, Whittington R, et al. Preliminary results of interstitial motexafin lutetium-mediated PDT for prostate cancer. Lasers Surg Med. 2006;38:427–434. doi: 10.1002/lsm.20341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Axelsson J, Swartling J, Andersson-Engels S. In vivo photosensitizer tomography inside the human prostate. Opt Lett. 2009;34:232–234. doi: 10.1364/ol.34.000232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Davidson SR, Weersink RA, Haider MA, Gertner MR, Bogaards A, Giewercer D, Scherz A, Sherar MD, Elhilali M, Chin JL, et al. Treatment planning and dose analysis for interstitial photodynamic therapy of prostate cancer. Phys Med Biol. 2009;54:2293–2313. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/54/8/003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Johansson A, Axelsson J, Andersson-Engels S, Swartling J. Realtime light dosimetry software tools for interstitial photodynamic therapy of the human prostate. Med Phys. 2007;34:4309–4321. doi: 10.1118/1.2790585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Okunaka T, Kato H, Tsutsui H, Ishizumi T, Ichinose S, Kuroiwa Y. Photodynamic therapy for peripheral lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2004;43:77–82. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2003.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Liu W, Oseroff AR, Baumann H. Photodynamic therapy causes cross-linking of signal transducer and activator of transcription proteins and attenuation of interleukin-6 cytokine responsiveness in epithelial cells. Cancer Res. 2004;64:6579–6587. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Henderson BW, Daroqui C, Tracy E, Vaughan LA, Loewen GM, Cooper MT, Baumann H. Cross-linking of signal transducer and activator of transcription 3: a molecular marker for the photodynamic reaction in cells and tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:3156–3163. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Edmonds C, Hagan S, Gallagher-Colombo SM, Busch TM, Cengel KA. Photodynamic therapy activated signaling from epidermal growth factor receptor and STAT3: targeting survival pathways to increase PDT efficacy in ovarian and lung cancer. Cancer Biol Ther. 2012;13:1463–1470. doi: 10.4161/cbt.22256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Mroz P, Hashmi JT, Huang YY, Lange N, Hamblin MR. Stimulation of anti-tumor immunity by photodynamic therapy. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2011;7:75–91. doi: 10.1586/eci.10.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Canti G, Lattuada D, Nicolin A, Taroni P, Valentini G, Cubeddu R. Immunopharmacology studies on photosensitizers used in photodynamic therapy (PDT) Proc SPIE 2078, Photodynamic Therapy of Cancer, 268 (March 1, 1994). [Google Scholar]

- 86.Korbelik M, Krosl G, Krosl J, Dougherty GJ. The role of host lymphoid populations in the response of mouse EMT6 tumor to photodynamic therapy. Cancer Res. 1996;56:5647–5652. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Thong PS, Ong KW, Goh NS, Kho KW, Manivasager V, Bhuvaneswari R, Olivo M, Soo KC. Photodynamic-therapy-activated immune response against distant untreated tumours in recurrent angiosarcoma. Lancet Oncol. 2007;8:950–952. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(07)70318-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Preise D, Oren R, Glinert I, Kalchenko V, Jung S, Scherz A, Salomon Y. Systemic antitumor protection by vascular-targeted photodynamic therapy involves cellular and humoral immunity. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2009;58:71–84. doi: 10.1007/s00262-008-0527-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Gollnick SO, Owczarczak B, Maier P. Photodynamic therapy and anti-tumor immunity. Lasers Surg Med. 2006;38:509–515. doi: 10.1002/lsm.20362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Sur BW, Nguyen P, Sun CH, Tromberg BJ, Nelson EL. Immunophototherapy using PDT combined with rapid intratumoral dendritic cell injection. Photochem Photobiol. 2008;84:1257–1264. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.2008.00356.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Garg AD, Krysko DV, Verfaillie T, Kaczmarek A, Ferreira GB, Marysael T, Rubio N, Firczuk M, Mathieu C, Roebroek AJ, et al. A novel pathway combining calreticulin exposure and ATP secretion in immunogenic cancer cell death. EMBO J. 2012;31:1062–1079. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Garg AD, Krysko DV, Vandenabeele P, Agostinis P. Hypericin-based photodynamic therapy induces surface exposure of damage-associated molecular patterns like HSP70 and calreticulin. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2012;61:215–221. doi: 10.1007/s00262-011-1184-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Garg AD, Agostinis P. ER stress, autophagy and immunogenic cell death in photodynamic therapy-induced anti-cancer immune responses. Photochem Photobiol Sci. 2014;13:474–487. doi: 10.1039/c3pp50333j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Jalili A, Makowski M, Switaj T, Nowis D, Wilczynski GM, Wilczek E, Chorazy-Massalska M, Radzikowska A, Maslinski W, Biały L, et al. Effective photoimmunotherapy of murine colon carcinoma induced by the combination of photodynamic therapy and dendritic cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:4498–4508. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Korbelik M, Cecic I. Contribution of myeloid and lymphoid host cells to the curative outcome of mouse sarcoma treatment by photodynamic therapy. Cancer Lett. 1999;137:91–98. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(98)00349-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Abdel-Hady ES, Martin-Hirsch P, Duggan-Keen M, Stern PL, Moore JV, Corbitt G, Kitchener HC, Hampson IN. Immunological and viral factors associated with the response of vulval intraepithelial neoplasia to photodynamic therapy. Cancer Res. 2001;61:192–196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Maeurer MJ, Gollin SM, Storkus WJ, Swaney W, Karbach J, Martin D, Castelli C, Salter R, Knuth A, Lotze MT. Tumor escape from immune recognition: loss of HLA-A2 melanoma cell surface expression is associated with a complex rearrangement of the short arm of chromosome 6. Clin Cancer Res. 1996;2:641–652. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Dragieva G, Hafner J, Dummer R, Schmid-Grendelmeier P, Roos M, Prinz BM, Burg G, Binswanger U, Kempf W. Topical photodynamic therapy in the treatment of actinic keratoses and Bowen’s disease in transplant recipients. Transplantation. 2004;77:115–121. doi: 10.1097/01.TP.0000107284.04969.5C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Wachowska M, Muchowicz A, Golab J. Targeting epigenetic processes in photodynamic therapy-induced anticancer immunity. Front Oncol. 2015;5:176. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2015.00176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Vesely MD, Kershaw MH, Schreiber RD, Smyth MJ. Natural innate and adaptive immunity to cancer. Annu Rev Immunol. 2011;29:235–271. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-031210-101324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Reginato E, Mroz P, Chung H, Kawakubo M, Wolf P, Hamblin MR. Photodynamic therapy plus regulatory T-cell depletion produces immunity against a mouse tumour that expresses a self-antigen. Br J Cancer. 2013;109:2167–2174. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Soria JC, Marabelle A, Brahmer JR, Gettinger S. Immune checkpoint modulation for non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21:2256–2262. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-2959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Brahmer JR, Tykodi SS, Chow LQ, Hwu WJ, Topalian SL, Hwu P, Drake CG, Camacho LH, Kauh J, Odunsi K, et al. Safety and activity of anti-PD-L1 antibody in patients with advanced cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2455–2465. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Lipson EJ, Sharfman WH, Drake CG, Wollner I, Taube JM, Anders RA, Xu H, Yao S, Pons A, Chen L, et al. Durable cancer regression off-treatment and effective reinduction therapy with an anti-PD-1 antibody. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:462–468. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-2625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Topalian SL, Hodi FS, Brahmer JR, Gettinger SN, Smith DC, McDermott DF, Powderly JD, Carvajal RD, Sosman JA, Atkins MB, et al. Safety, activity, and immune correlates of anti-PD-1 antibody in cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2443–2454. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Rizvi NA, Mazières J, Planchard D, Stinchcombe TE, Dy GK, Antonia SJ, Horn L, Lena H, Minenza E, Mennecier B, et al. Activity and safety of nivolumab, an anti-PD-1 immune checkpoint inhibitor, for patients with advanced, refractory squamous non-small-cell lung cancer (CheckMate 063): a phase 2, single-arm trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:257–265. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)70054-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]