Abstract

In this article, we compare predictors of mothers’ differentiation among their adult children regarding emotional closeness, pride, conflict, and disappointment. We distinguish between predictors of relational (closeness, conflict) and evaluative (pride, disappointment) dimensions of favoritism and disfavoritism. Multilevel modeling using data collected from 381 older mothers regarding their relationships with 1,421 adult children indicated that adult children’s similarity of values played the most prominent role in predicting mothers’ favoritism and disfavoritism, followed by children’s gender. Children’s deviant behaviors in adulthood predicted both pride and disappointment but neither relational dimension. Contrary to expectations, the quantitative analysis indicated that children’s normative adult achievements were poor predictors of both relational and evaluative dimensions of mothers’ differentiation. Qualitative data shed additional light on mothers’ evaluations by revealing that disappointment was shaped by children’s achievements relative to their mothers’ values and expectations, rather than by the achievement of specific societal, educational, career, and marital milestones.

Keywords: Adult children, parental favoritism, parent–child relations, older adults

Background

The role of within-family differences in the relationship between parents and their young children has been of substantial interest to developmental psychologists since the early 1980s (Jenkins, Rasbash, Leckie, Gass, & Dunn, 2012; McHale, Updegraff, Jackson-Newsom, Tucker, & Crouter, 2000; Shanahan, McHale, Crouter, & Osgood, 2008; Suitor, Sechrist, Plikuhn, Pardo, & Pillemer, 2008). This literature has revealed substantial differences among parent–adult child dyads within the same family. In particular, the overwhelming majority of both mothers and fathers have been found to differentiate among their children across a wide range of relational dimensions, including parental closeness and investment of time and resources, as well as control and discipline (Feinberg & Hetherington, 2001; McHale, Updegraff, Tucker, & Crouter, 2000; Richmond, Stocker, & Rienks, 2005; Shanahan et al., 2008).

This line of research has documented that children’s perceptions of parental differential treatment (PDT), particularly negative differential treatment, are associated with decreased well-being (Feinberg & Hetherington, 2001; McHale, Updegraff, Tucker, & Crouter, 2000; Richmond et al., 2005; Shanahan et al., 2008). Research on young adults has revealed similarly negative effects of perceptions of parental favoritism and disfavoritism on psychological well-being (Jensen, Whiteman, Fingerman, & Birditt, 2013; Young & Ehrenberg, 2007).

Research over the past decade has revealed that such within-family differentiation also occurs in later-life families and has important consequences for adult children’s psychological well-being and for the quality of sibling relations. Specifically, the perception that parents favor one child over another in adulthood is associated with higher depressive symptoms among adult children (Pillemer, Suitor, Pardo, & Henderson, 2010; Suitor, Gilligan, Peng, Jung, & Pillemer, 2015), as well as greater conflict and less closeness among siblings (Boll, Ferring, & Filipp, 2005; Gilligan, Suitor, Kim, & Pillemer, 2013; Suitor et al., 2009; Suitor, Gilligan, Johnson, & Pillemer, 2014). Further, there is evidence that perceptions of disfavoritism, such as some offspring being perceived as having greater conflict with parents, or being the children in whom mothers are most disappointed, is also associated with higher depressive symptoms (Pillemer et al., 2010; Suitor et al., 2015). Data collected from both mothers and adult children have shown that such patterns of mothers’ reported favoritism and adult children’s perceptions of favoritism tend to be relatively stable over time (Suitor, Gilligan, & Pillemer, 2013), which suggests that maternal differential treatment in adulthood may play an important role in relational and psychological well-being. It appears that recollections of favoritism and disfavoritism from childhood also affect both psychological well-being (Davey, Tucker, Fingerman, & Savla, 2009) and sibling relations (Suitor et al., 2009). Taken together, this body of research shows that parental favoritism is a salient factor in adult children’s well-being and sibling relations in adulthood.

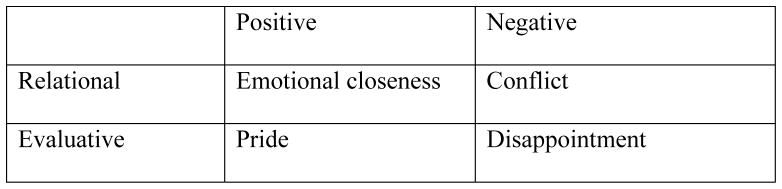

The purpose of this article is to expand the study of parental differentiation in the later years by comparing predictors of mothers’ reports of favoritism and disfavoritism regarding their adult children. In particular, we compare predictors of mothers’ reports of offspring to whom they are most emotionally close and in whom they have the most pride to those with whom they have the greatest conflict and in whom they are most disappointed. Beyond distinguishing between favoritism and disfavoritism, we also distinguish between what we define as relational and evaluative dimensions of favoritism and disfavoritism.

As Figure 1 shows, we conceptualize emotional closeness and conflict to be socioemotional characteristics of the parent–adult child relationship. Thus, when mothers differentiate on these dimensions, they are considering the quality of the relationship. Therefore, we designate these as “relational” dimensions of favoritism and disfavoritism. In contrast, we conceptualize pride and disappointment to be assessments of mothers’ satisfaction and dissatisfaction with their children’s progress toward goals held to be important by their mothers (Lazarus, 2006; Ryff, Schmutte, & Lee, 1996). Thus, we designate these as “evaluative” dimensions of favoritism and disfavoritism. We consider the distinction between relational and evaluative dimensions of parental favoritism and disfavoritism to be important in attempts to understand both the predictors and the consequences of parental differentiation.

Figure 1.

Conceptualization of Dimensions of Maternal Differentiation.

To explore these issues, we use a combination of quantitative and qualitative data collected from 381 older mothers regarding their relationships with 1,417 adult children, collected as part of the second wave of the Within-Family Differences Study. Our rationale for this approach is that although quantitative analyses can identify patterns of associations among constructs, qualitative data are more useful for understanding the processes underlying statistical relationships (Creswell & Clark, 2010). Inclusion of both methods is especially the case when the focus is on complex patterns, as in the case of multigenerational ties within families (Neal, Hammer, & Morgan, 2006; Plano Clark, Huddleston-Casas, Churchill, O’Neil Green, & Garrett, 2008).

Predicting Maternal Favoritism and Disfavoritism

Three key concepts of the life course perspective have been found to play important roles in the quality of relations between parents and adult children in the middle and later years: (a) children’s attainment of adult social structural positions, which include education, marital, parental, and employment status, as well as avoidance of deviant behaviors; (b) similarity between mothers and children, particularly regarding gender and values; and (c) exchanges of support (Suitor, Sechrist, Gilligan, & Pillemer, 2011). We hypothesize that all three factors predict both relational and evaluative dimensions of mothers’ favoritism and disfavoritism; however, the importance of these factors will vary depending on whether the dimensions of differentiation are relational or evaluative.

Predicting Relational Dimensions of Maternal Favoritism and Disfavoritism

As Figure 1 shows, the two relational dimensions of favoritism and disfavoritism we consider in this article are emotional closeness and conflict. Consistent with the broader literature on intergenerational relations (Birditt & Fingerman, 2013; Silverstein & Giarrusso, 2010), previous research has reported that mothers’ favoritism regarding emotional closeness is predicted by a combination of similarity between mothers and children, support processes, birth order, and—to a much lesser extent—children’s social structural positions (Suitor & Pillemer, 2007; Suitor et al., 2013). Specifically, mothers have been found to prefer daughters, children who share their values, last-borns, and those with whom they have an established history of supportive exchanges (Suitor & Pillemer, 2006; Suitor et al., 2013). In contrast, studies of within-family differences in closeness have not found social structural positions to be consistent predictors of mothers’ differentiation (Suitor & Pillemer, 2006; Suitor et al., 2013); thus, we do not anticipate that they will play a role in which children mothers name as those to whom they are most emotionally close.

Although previous studies have examined the role of parental disfavoritism in adulthood in psychological well-being (Jensen et al., 2013; Pillemer et al., 2010; Suitor et al., 2015), to date the predictors of mothers’ disfavoritism toward their children in adulthood have not been investigated. We propose that the predictors of mothers’ relational disfavoritism—measured by conflict in the present study—will be similar to those predicting emotional closeness. However, we also propose that the achievement and maintenance of adult social structural positions, particularly regarding educational attainment and employment, will predict conflict. Studies of parent–adult child relations have revealed both that children’s failure to achieve adult social structural positions and that their engagement in deviant behaviors results in conflict between mothers and their offspring (Gilligan, Suitor, & Pillemer, 2013; Fingerman, Cheng, Birditt, & Zarit, 2012; Greenfield & Marks, 2006). We therefore anticipate that these factors will also predict with which offspring mothers have the greatest conflict. Finally, although the literature consistently shows stronger positive ties between mothers and their daughters than mothers and their sons (Birditt, Tighe, Fingerman, & Zarit, 2012; Suitor & Pillemer, 2006; Suitor et al., 2013), recent research has suggested that mothers may also have more conflictual relationships with their daughters than sons (Birditt et al., 2012). Thus, we anticipate that mothers will identify daughters as those with whom they have the greatest conflict.

In summary, we hypothesize that mothers’ differentiation regarding the relational dimensions of favoritism and disfavoritism will be shaped by similarity of values and gender, children’s patterns of support to their mothers, children’s deviant behaviors, and—to a lesser extent—children’s social structural positions. Specifically, we anticipate that mothers will report being most emotionally close to children who are daughters, who share their values, and who have provided support. We anticipate that mothers will report the greatest conflict with children who do not share their values, are daughters, have not provided support, continue to engage in deviant behaviors, and have not achieved or maintained adult social structural positions.

Predicting Evaluative Dimensions of Maternal Favoritism and Disfavoritism

As Figure 1 shows, the two evaluative dimensions of favoritism and disfavoritism we consider in this article are mothers’ pride and disappointment in their children. Unlike the two relational dimensions of mothers’ differentiation, we anticipate that all three key concepts of the life course perspective highlighted already (children’s attainment of adult social structural positions, similarity between mothers and children, and exchanges of support) will play important roles in predicting both evaluative dimensions of mothers’ differentiation.

Few studies have investigated parents’ pride and disappointment in their children in adulthood (see Carr, 2005; Cichy, Lefkowitz, Davis, & Fingerman, 2013; Ryff et al., 1996). On the basis of this research, we hypothesize that mothers’ differentiation among their children regarding pride and disappointment will be influenced by which of their adult children has best adhered to normative expectations for adult development. The importance of normative adult transitions regarding education, employment, and establishing families for parent–adult child relations has been demonstrated by numerous studies (Cichy et al., 2013; Fingerman et al., 2012; Greenfield & Marks, 2006; Ryff et al., 1996). Thus, we anticipate that the achievement of adult statuses will predict which offspring mothers identify when differentiating among their children regarding both pride and disappointment.

We also anticipate that children’s deviant behaviors, such as substance abuse and illegal activities, will shape mothers’ differentiation regarding both pride and disappointment. Studies have shown that adult children’s engagement in such behaviors causes parents to question their parenting skills (Green, Ensminger, Robertson, & Juon, 2006; Ryff et al., 1996) and may be a source of embarrassment and shame (Condry, 2007; Green et al., 2006). Therefore, we hypothesize that engaging in deviant behaviors will predict mothers’ favoritism regarding both pride and disappointment.

We propose that similarity of values will also predict pride and disappointment. Theories of child development hold that a primary goal of parental socialization is transmitting the values that mothers and fathers believe are necessary to be a “good adult” (Grusec, 2002). Because parents typically attempt to socialize their children to hold the values that they hold themselves, adherence to this expectation would be expected to create feelings of pride, whereas deviation from this expectation would likely create feelings of disappointment. In fact, Aldous, Klaus, and Klein’s (1985) early study of maternal differentiation found that disparity of values was a strong predictor of the children in which mothers were most disappointed.

Studies of intergenerational relations have found that parents and adult children generally express better relationship quality when there is a flow of support between the generations (Merz, Schuengel, & Schulze, 2009; Schenk & Dykstra, 2012; Sechrist, Suitor, Howard, & Pillemer, 2014; Suitor et al., 2013). Further, continuity in adult children’s provision of instrumental support across time has been found to predict mothers’ favoritism regarding emotional closeness (Suitor et al., 2013). We suggest that support processes may also shape mothers’ differentiation among their offspring regarding both pride and disappointment. Norms of filial responsibility have weakened across the past few decades (Gans & Silverstein, 2006); thus, mothers might be particularly proud of adult children’s provision of support and disappointed in the absence of support, because such support reflects children’s choices rather than adherence to strict normative expectations. On the basis of this argument, we hypothesize that mothers will report that they are the most proud of children who provided support and most disappointed in those who did not.

Finally, unlike relational dimensions of maternal differentiation, in which we anticipate that gender and birth order will be important predictors of favoritism and disfavoritism, we do not expect that they will play a role in evaluative dimensions of differentiation because, in most cases, the characteristics do not reflect adult children’s behavioral or attitudinal choices.

In summary, we hypothesize that mothers will report being the most proud of adult children who have achieved or maintained adult social structural positions, who share the mother’s values, and who have provided them with instrumental and expressive support. We hypothesize that mothers will report the greatest disappointment in adult children who have not achieved or maintained adult social structural positions, do not share their values, have not provided them with support, and continue to engage in deviant behaviors.

Other Factors That May Affect Maternal Favoritism and Disfavoritism

On the basis of the literature, the quality of parent–adult child relations is also shaped by several family-level characteristics, including family size, race, gender composition of the family, and residential proximity (Birditt & Fingerman, 2013; Silverstein & Giarrusso, 2010; Suitor et al., 2011). These factors have also been found to predict some dimensions of maternal favoritism in adulthood (Suitor et al., 2011; Suitor et al., 2013). Thus, it is important to take these factors into consideration to reduce the likelihood that any apparent effects of child-level characteristics on favoritism and disfavoritism could be accounted for by the association among these factors.

Method

The data used in the present analyses were collected as part of the Within-Family Differences Study (WFDS). The design of the WFDS involved selecting a sample of mothers 65–75 years of age with at least two living adult children and collecting data from mothers regarding each of their children. The first wave of interviews in the WFDS took place with 566 women between 2001 and 2003; the original study was expanded to include a second wave of data collection from 2008 to 2011. In this article we have used data collected from 381 mothers who were interviewed at both T1 and T2 regarding 1,421 of their children. (Portions of the description of the methods have been published previously; see Suitor & Pillemer, 2006; Suitor et al., 2013).

Procedures

Massachusetts city and town lists were used as the source of the original WFDS sample. With the assistance of the Center for Survey Research (CSR) at the University of Massachusetts, Boston, Suitor and Pillemer drew a probability sample of women ages 65–75 with two or more children from the greater Boston area. The T1 sample consisted of 566 mothers, which represented 61% of those who were eligible for participation, a rate comparable to that of similar surveys in the past decade (Wright & Marsden, 2010).

For the follow-up study, the survey team attempted to contact each mother who participated in the original study. At T2, 420 mothers were interviewed. Of the 146 mothers who participated at only T1, 78 had died between waves, 19 were too ill to be interviewed, 33 refused, and 16 could not be reached. Thus, the 420 represent 86% of mothers who were living at T2. Comparison of the T1 and T2 samples revealed that the respondents differed on subjective health, educational attainment, marital status, and race. Mothers who were not interviewed at T2 were less healthy, less educated, and less likely to have been married at T1; they were also more likely to be Black. There were no consistent differences in their likelihood of having differentiated among their children at T1; in fact, these analyses revealed that with the exception of Black mothers being less likely to name a child as a confidant, mothers’ likelihood of differentiation was driven by children’s rather than mothers’ characteristics (Suitor, Sechrist, & Pillemer, 2007). Comparisons between the mothers alive at T2 who did and did not participate revealed that they differed only on education and subjective health.

We omitted six mothers from the present analysis because they lost one of their only two children between waves. To be included in the analytic sample, mothers must have differentiated among their children for at least one of the four dimensions of favoritism or disfavoritism at T2. Thirty-three mothers did not differentiate among their adult children across any of these four relational contexts at T2 and were therefore omitted from the analyses. The final analytic sample consisted of 381 mothers who reported on their relationships with a total of 1,421 living adult children at T2. Because the percentage of mothers who favored a child varied across domains, the number of children included in each analysis also varied. For the analysis of emotional closeness, the analytic sample included 1,077 children; for the analysis of conflict, it included 1,038; for pride, it included 903; and for disappointment, the analytic sample included 856 adult children.

Table 1 presents the demographic characteristics of the 381 mothers and 1,421 adult children on whom mothers reported.

Table 1.

Demographics on Mothers and Adult Children

| Means, SD, % | |

|---|---|

| Mothers | (n = 381) |

| Age in years (SD) | 77.8 (3.1) |

| Race (in %) | |

| White | 72.1 |

| Non-White | 27.9 |

| Marital status (in %) | |

| Married | 39.3 |

| Cohabiting | .7 |

| Divorced/separated | 14.6 |

| Widowed | 44.8 |

| Never married | .7 |

| Education (in %) | |

| Less than high school | 19.1 |

| High school graduate | 44.1 |

| Some college | 12.9 |

| College graduate | 24.0 |

| Number of children (SD) | 3.7 (1.7) |

| Adult children | (n = 1,421) |

| Age in years (SD) | 49.5 (5.8) |

| Daughters (in %) | 51.0 |

| Education (in %) | |

| Less than high school | 7.0 |

| High school graduate | 32.2 |

| Some college | 12.5 |

| College graduate | 48.4 |

Measures

Dependent variables

To measure maternal differentiation, mothers were asked a series of questions that required them to select from among all their adult children. Each mother was asked to select (a) to which of her children she felt the most emotionally close; (b) of which of her children she felt the most proud; (c) with which of her children she experienced the most disagreements or arguments; and (d) in which of her children she was the most disappointed. Each child was coded as 0 for each of the items for which he or she was not chosen and 1 for each item for which he or she was chosen. Mothers rarely named more than one child (less than 1% for disappointment, 2% for emotional closeness and conflict, and 6% for pride). When mothers named two children, both of the children were considered favored or disfavored because they were identified from a larger group of offspring. In cases in which mothers of only two children named both, the mother was considered as not having made a choice. The analytic approach we used allowed more than one “positive case” per family.

In cases in which mothers were initially unwilling to differentiate among their children, the interviewers were instructed to prompt the mothers with a follow-up question (e.g., “But is there one child to whom you feel the most emotionally close?”). Fewer than 5% of mothers were moved by the prompt to select a child, and there were no sociodemographic differences between mothers who did and did not respond to the prompt. Further, separate examination revealed that none of the findings was affected by the inclusion of these women.

Independent variables

Perceived value similarity was measured by the item “Parents and children are sometimes similar to each other in their views and opinions and sometimes different from each other. Would you say that you and [child’s name] share very similar views (4), similar views (3), different views (2), or very different views (1) in terms of general outlook on life?” Examination of the reasons mothers provided to explain their choices indicated that they chose on the basis of similarity of values, interests, life experiences, and approaches to life, consistent with Bengtson and colleagues’ conceptualization of normative solidarity (Bengtson, 2001; Silverstein & Bengtson, 1997).

To assess support processes, mothers were asked about the support they received from each of their adult children. For expressive support, mothers were asked, “In the past year, has [child’s name] given you: (a) comfort during a personal crisis or (b) advice.” Each item was coded 0 or 1. We combined the two items into one measure of expressive support (0 = no support provided by child to mother in past year; 1 = support provided by child to mother in the past year). To assess instrumental support, mothers were asked whether, in the past, the child had provided (a) help with household chores and/or (b) help when ill. We then created a measure of provision of instrumental support using the same procedures used to create the measure of expressive support.

To measure children’s deviant behaviors, mothers were asked whether each of their adult children had experienced any of a series of problems. For the present analysis we used substance abuse or problems with the law. At T1 the mothers were asked to specify whether the child had experienced these problems at any point in adulthood; at T2 they were asked whether the child had experienced these problems in the previous five years. Children were then assigned to one of the three following categories: (a) never engaged in deviant behaviors in adulthood (86.1%), (b) engaged in deviant behaviors in adulthood before T1 but disengaged in them by (6.6%), and (c) engaged in deviant behaviors at T1 and T2 or began engaging in these behaviors between T1 and T2 (7.3%). Ideally, we would have liked to have created a separate category, “beginning deviant behaviors between T1 and T2”; however, there were few cases that fit this criterion (n = 40; 2.7%), as would be expected given the average age of the adult children at T2 (49.5 years).

Child’s marital status was reported by mothers at T2. Using mothers’ reports from T1 and T2, we transformed marital status into (0) unmarried at both T1 and T2 (27.4%), (1) married at T1 only (6.8%), (2) married at T2 only (9.5%), and (3) married at both T1 and T2 (56.3%). A few children had divorced and remarried between waves; we coded these children as married at T1 and T2. Similarly, the few who had been unmarried at T1 but married and divorced between waves were coded as unmarried at T1 and T2. Unmarried at T1 and T2 was the referent category.

To measure children’s parental status, mothers reported how many offspring each child had at T1; at T2 they were asked whether each child had given birth to or adopted children between waves. Each child was categorized as a parent (1) or childless (0) at T2.

We asked mothers about their children’s current employment at T1 but not at T2. Instead, we collected information on children’s recent unemployment at T2. Mothers were asked whether each child had “not had a job when he/she wanted to work” in the previous year (no = 0; 1 = yes). We controlled for child’s employment at T1 (1 = employed). Eighty-two percent of the adult children were employed at T1; 5.4% were unemployed and seeking work within in the year prior to T2.

Residential proximity was measured in travel time by ground transportation at T2. Categories were (a) same house, (b) same neighborhood, (c) less than 15 minutes away, (d) 15–30 minutes away, (e) 30–60 minutes away, (f) more than 1 hour but less than 2 hours, (g) and 2 or more hours away.

To measure birth order, each child was coded as first, middle, or last-born, on the basis of age. Previous research has shown that last-borns are favored by their mothers with respect to emotional closeness, whereas firstborns are not (Suitor et al., 2013)—for this reason we dichotomized into last born (1) and not last born (0).

Gender was coded 0 = son, and 1 = daughter.

Family size was measured using the number of living adult children in the family at T2.

Race was measured by asking the mothers to select from a card listing several races and ethnicities (e.g., White, Black or African American, Hispanic or Latina, Native American, Asian). Following the literature on later-life families, which has shown greater filial responsibility in Black, Asian, and Hispanic than in White families, we coded race as 1 = White, and 0 = not White.

Analytic Plan for the Quantitative Analysis

Throughout the multivariate analyses, the parent–child relationship, rather than the parent, was the unit of analysis. In other words, the 1,421 children who were the units of analysis were nested within the 381 mothers on whose reports the present analysis is based; thus, the observations were not independent. To take this factor into account, we used multilevel binomial logistic regression. This technique also allowed us to address our specific question: “What factors differentiate between children whom mothers favored or disfavored, relative to those whom she did not?” Further, multilevel binomial modeling permitted us to control family size and race. Listwise deletion was used to handle missing data on the independent variables because there were fewer than 1% missing on any variable in the analysis (see Allison, 2010). The analyses were conducted using SPSS22.

Using Qualitative Data to Explain Mothers’ Favoritism and Disfavoritism

Semistructured interviews with the mothers were conducted in person and, in almost all cases, were fully audiotaped. For many of the closed items mothers were given the opportunity to discuss their responses more fully. For each of the favoritism and disfavoritism items, mothers were asked to discuss why they had selected those particular offspring. For the items included in this article, mothers were not asked specifically to compare chosen to unchosen offspring in their open-ended comments; nevertheless, mothers often provided detailed comparisons among their children in their responses.

Codes were developed for the open-ended items as data preparation continued rather than being established prior to the coding process. A research team of six students transcribed the interviews, coded the open-ended items, and prepared detailed case summaries of each family. In contrast to having coders working independently and calculating kappas from coders’ consistency, we used a consensus approach based on the group interactive analysis component of Borkan’s (1999) immersion/crystallization method for analyzing qualitative data. Each week the principal investigator (PI) surveyed all of the open-ended coding that had been completed during the previous week. Approximately 90% of the coders’ original decisions were in agreement with those of the PI; any coding that was not in agreement with the PI’s assessment was discussed by the entire group at weekly team meetings until consensus could be reached. All names used in the qualitative section are pseudonyms.

Results

Descriptive Results

Distribution of mothers’ favoritism and disfavoritism

The majority of mothers identified children whom they favored and children whom they disfavored. In terms of relational dimensions of differentiation, approximately three-quarters of the mothers identified a particular child to whom they were most emotionally close (75.3%) and a particular child with whom they experienced the greatest conflict (74.3%). In terms of evaluative dimensions, approximately six in 10 mothers identified a child of whom they were the most proud (59.2%) and a child in whom they were the most disappointed (58.0%).

Following Bengtson’s classic work on the generational stake (Bengtson & Kuypers, 1971), we anticipated that mothers would be more willing to differentiate regarding favoritism than disfavoritism. However, this was not the characteristic that distinguished the dimensions on which mothers were willing to identify particular offspring. What was particularly striking was the discrepancy between mothers’ likelihood of naming a child for the relational as opposed to the evaluative dimensions of differentiation. Specifically, mothers were approximately 25% more likely to identify a child for the relational than the evaluative dimensions of both favoritism and disfavoritism. These findings suggest that although mothers are willing to report both favoritism and disfavoritism regarding their adult children, they are much less likely to do so when they are asked about evaluations of their offspring than when they are asked about their socioemotional relationships with them.

Multiplexity in mothers’ favoritism and disfavoritism

One question that cannot be answered by examining the distribution of mothers’ favoritism and disfavoritism is the degree of multiplexity in mothers’ differentiation—in other words, the degree to which mothers name the same child for more than one dimension. It might be expected that mothers’ differentiation might “cluster” on the basis of favoritism, in which mothers would name the same children for both emotional closeness and pride, and the same children for conflict and disappointment. Alternatively, choices might cluster according to the relational versus evaluative nature of the dimensions of differentiation. However, as Table 2 shows, there is remarkably little multiplexity in mothers’ choices. Most notably, there are only negative correlations between the favoritism and disfavoritism items (ranging from −.03 to −.29), which indicates that it is rare that the same offspring are chosen for closeness or pride and either conflict or disappointment. Further, the correlation between the two dimensions of favoritism (emotional closeness and pride) are only moderate (r = .11). In fact, the only strong indicator of multiplexity among the correlations is between disappointment and conflict (r = .29).

Table 2.

Correlation Matrix of Dimensions of Favoritism and Disfavoritism

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Most emotionally close | — | |||

| 2. Most disagreements | −.03 | — | ||

| 3. Most proud | .11** | −.14** | — | |

| 4. Most disappointed | −.14** | .29** | −.29** | — |

p < .01.

Taken together, these findings indicate that mothers typically do not name the same child across dimensions of favoritism and disfavoritism, and they are especially unlikely to do so in the case of naming the same children for both favoritism and disfavoritism. Finally, even in the case of the two negative dimensions of differentiation, mothers generally named different children.

Explaining Mothers’ Favoritism and Disfavoritism

We began the multivariate analyses by examining the variance explained by the mother-level characteristics. We ran an intercept-only model, which provided the variance components to calculate the interclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) (Heck, Thomas, & Tabata, 2012). The ICCs ranged from .01 to .02, indicating that the mother-level factors accounted for only 1%–2% of the variance in mothers’ choices. Although the amount of mother-level variance is small, we conducted subsequent analyses to determine whether we could identify any particular mother-level characteristics that accounted for this explained variance. This analysis revealed that of the mother-level characteristics, only family size and race predicted patterns of favoritism for any of the dimensions under consideration.

Explaining Relational Dimensions of Favoritism and Disfavoritism

As shown in the first column of Table 3, mothers reported being the most emotionally close to daughters (OR = 2.96), last-borns (OR = 1.70), and to offspring who shared the mothers’ values (OR = 1.50). However, contrary to our hypotheses, children’s provision of support did not predict which offspring mothers chose for emotional closeness. The odds of a mother naming a particular child to whom they were most emotionally close were lower in larger families (odds ratio, OR = .73) and when mothers had a higher proportion of daughters than sons (OR = .44).

Table 3.

Binomial Multilevel Regression Predicting Mother’s Favoritism and Disfavoritism (Odds Ratios)

| Relational Dimensions | Evaluative Dimensions | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Most Emotionally Close (n = 1,077 dyads) | Most Conflict (n = 1,038 dyads) | Most Proud (n = 903 dyads) | Most Disappointed (n = 856 dyads) | |

| Mother-level characteristics | ||||

| Family size | .73** | .77** | .82** | .71** |

| Race (Black = 1) | 1.05 | .78 | 2.01** | .59* |

| Proportion daughters | .44* | .58 | .99 | 1.48 |

| Children’s characteristics | ||||

| Daughter | 2.96** | 1.96** | 1.14 | .53** |

| Child marital statusa | ||||

| Ended marriage between T1 and T2 | .65 | .93 | 1.28 | .94 |

| Entered marriage between T1 and T2 | .57 | .66 | .87 | .67 |

| Remained married from T1 and T2 | .84 | .56** | 1.50 | .54** |

| Parent | .73 | 1.43 | .85 | .94 |

| Educational attainment | .96 | .98 | 1.26** | .90 |

| Employment | ||||

| Employed at T1 | .96 | 1.18 | 1.34 | 1.02 |

| Looking for work year before T2 | 1.36 | 1.56 | .62 | .94 |

| Child engaged in deviant behaviors in adulthood b | ||||

| Reported T1 only | 1.40 | 1.52 | .86 | .84 |

| Reported T2 only or both T1&T2 | .81 | 1.01 | .36* | 2.03* |

| Last-born | 1.70** | 1.26 | 1.17 | .93 |

| Characteristics of parent–child dyad | ||||

| Child provided support to mother | ||||

| Provided instrumental support at T2 | 1.28 | 1.25 | 1.16 | .88 |

| Provided expressive support at T2 | 1.24 | .83 | 1.75** | .79 |

| Value similarity | 1.50** | .52** | 1.46** | .51** |

| Distance lived from mother | .93 | .88** | 1.02 | .95 |

| Log likelihood | 1,115.627 | 1,083.865 | 1,001.126 | 823.827 |

| Akaike information criterion | 1,154.346 | 1,122.611 | 1,039.987 | 862.736 |

| Bayesian information criterion | 1,248.284 | 1,215.821 | 1,130.435 | 952.120 |

Referent is child unmarried at both T1 and T2.

Referent is child did not engage in deviant behaviors in adulthood.

p < .05.

p < .01.

The findings regarding mothers’ choices for the children with whom they experienced the most conflict are shown in the second column in Table 3. As expected, mothers were more likely to report the greatest conflict with daughters (OR = 1.96). Also consistent with our hypotheses, mothers were less likely to report the greatest conflict with those who shared their values (OR = .52). Our expectations regarding the role of social structural positions were only partially supported; mothers were less likely to report the greatest conflict with children who remained married across the two waves of data (OR = .56). However, mothers’ choices were not predicted by educational attainment, employment or parental status, or engagement in deviant behaviors. The odds of naming any specific child as the greatest source of conflict were lower in larger families (OR = .77).

Explaining Evaluative Dimensions of Favoritism and Disfavoritism

The findings for mothers’ reports of the children of whom they were most proud are shown in the third column in Table 3. As we hypothesized, mothers’ choices for children in whom they had the greatest pride were predicted by educational attainment (OR = 1.26); however, contrary to expectations, none of the other normative adult status achievements, such as employment, marital, or parental status, shaped mothers’ choices. However, continued engagement from T1 to T2 or new engagement in deviant behaviors since T1 substantially reduced the likelihood that those offspring would be named as those in whom mothers had the most pride (OR = .36). Also consistent with our expectations, both value similarity (OR = 1.46) and the provision of expressive support (OR = 1.75) predicted mothers’ choices for pride. Finally, although mothers’ race has not been found previously to shape mothers’ favoritism or disfavoritism regarding relational dimensions, it played a role in mother’s likelihood of differentiating among their offspring with respect to pride; specifically, the odds of choosing any particular child as the one in whom they had greater pride were greater for Black than White mothers (OR = 2.01).

The findings regarding mothers’ choices for disappointment are shown in the far right column of Table 3. As was the case for pride, adult children’s normative adult achievements played a much smaller role than anticipated in which children mothers were the most disappointed. Although mothers were only about half as likely to be disappointed in children who had remained married from T1 to T2 (OR = .54), mothers’ disappointment was not predicted by employment, educational attainment, or parental status. Consistent with our expectations, continuing to engage in deviant behaviors or beginning to engage in such behaviors more than doubled the odds of being named as the children in whom mothers were most disappointed (OR = 2.03). Also consistent with our hypotheses, value similarity greatly reduced the odds of being named as the children in whom mothers were the most disappointed (OR = .51). Although we did not anticipate that gender would play a role in mothers’ disappointment, mothers were substantially less likely to name daughters than sons as those in whom they were the most disappointed (OR = .53). Given that daughters are less likely to engage in substance abuse and illegal behaviors (Condry, 2007), this factor might explain the effects of gender on mothers’ disappointment. However, the odds ratio for gender remained unchanged when deviant behaviors were removed from the model (table not shown). Finally, race predicted the likelihood that mothers would differentiate among their offspring, with Black mothers less likely to report that they were disappointed in any particular child (OR = .59).

In a separate set of analyses we examined whether the predictors of any of the four dimensions of favoritism and disfavoritism differed by child’s gender. These analyses revealed no consistent or statistically significant differences by gender for any of the four dimensions of mothers’ differentiation under consideration (tables not shown).

Qualitative Analysis of Mothers’ Favoritism and Disfavoritism

Our goal in taking a mixed-methods approach to studying predictors of mothers’ favoritism and disfavoritism was to reveal patterns that could not be identified by quantitative analyses alone. Thus, in this discussion, we emphasize the additional insights provided by the mothers’ explanations for their choices. The most interesting patterns involved mothers’ reasons for being especially disappointed in some of their offspring relative to their other children. These explanations brought together factors that the quantitative analysis highlighted as shaping disappointment (gender and marital stability) and factors that the quantitative analysis suggested did not play a role in disappointment—specifically, educational attainment and employment.

As we noted in the presentation of the quantitative analyses, we found no consistent gender differences in the predictors of mothers’ choices for any of the four dimensions of favoritism or disfavoritism. However, the mothers’ discussions of choosing children in whom they were the most disappointed revealed differences in the bases on which they were particularly disappointed in sons compared to daughters. The most common basis of disappointment, voiced by 99 mothers, was their children’s failure to meet the mothers’ expectations regarding normative adult status achievement. However, despite the absence of gender differences in predictors of disappointment in the quantitative analysis, there were clear gender differences in the expectations that the mothers felt their children had violated.

Sixty-nine of the 99 mothers explained that their feelings were fueled by concerns about their children’s educational and career success—in two-thirds of these cases, mothers focused on sons. In contrast, 30 of the 99 mothers cited concerns about their children’s marriages—in more than three-quarters of these cases, mothers focused on daughters. Thus, in contrast to the quantitative analysis, the mothers’ own explanations for their disappointment in their offspring suggest clear gender differences in the basis for their disappointment. The gender differences in these patterns are particularly salient because violations of mothers’ expectations regarding careers and marriage were the two most commonly voiced criteria shaping mothers’ differentiation regarding disappointment.

Examination of the mothers’ explanations for their disappointment in particular children revealed a second important pattern: the striking contrast between the salience of children’s educational and occupational achievements in the quantitative and qualitative analyses. This discrepancy lies in mothers’ concerns with their children’s success relative to their potential rather than whether they had reached particular societal educational and career benchmarks.

For example, Gerry, a mother of four, explained that although her son, John, had completed college and was employed in a position of responsibility, she was disappointed that he did not achieve more occupationally:

I’ll have to say John because he went through college. [But] he skipped the scene in what he graduated with and he’s not doing what he should be doing…. [H]e could be doing more than what he is doing.

Gerry’s choice for the child in which she is most disappointed is a striking example of the role of unmet expectations in mothers’ disappointment; John is the only one of her children who does not have a history of substance abuse. However, she does not hold the same expectations for her other children, they are not her greatest disappointment.

In some cases, mothers were the most disappointed in children whose educational attainment and job experiences would lead us to expect that those children would be chosen as those in whom the mothers are most proud. For example, Jeanne, a mother of three, voiced her disappointment in her son Jason because he continued to pursue new educational and occupational opportunities rather than being content with his current level of achievement:

Because he has all these certifications and degrees and everything like that and he keeps changing jobs all the time. And can’t seem to settle down where he is. And why doesn’t he do it? Every time he gets another certifications, he does it for a while and then he does something else…. He has the skills, he utilizes them for a little bit and then he wants to go onto something else and then just continually changing from one thing to the next.

In contrast, Jeanne is the most proud of her other son, who has continued to pursue the same job since graduating from college.

For other mothers, their disappointment lay in their children’s unwillingness to seek opportunities to better their lot. Jackie, a mother of four, identified her daughter Shirley as the child in whom she is most disappointed, despite the fact that Shirley is the child with the most stable employment history:

Well, she [moved to another state 25 years ago] and she must be doing good for herself but … she had a job at this hospital and she been there ever since…. [N]obody [stays with] the first job they get. You always try to grow. You always try to get something better but she is just so complacent.

Thus, disappointment in children’s educational and occupational choices could not be captured simply by whether the offspring had reached societal benchmarks, but by which of their children had met the expectations that their mothers held for them as individuals, based on the combination of the mothers’ hopes and their perceptions of their children’s potential.

Similarly, mothers disappointed in their children’s marriages rarely voiced concerns about their children’s actual marital status but instead emphasized the choices the children had made that had created difficult and sometimes untenable relationships. Linda, a mother of four, reported that she was the most disappointed in her eldest daughter, Katherine, who divorced and remarried between T1 and T2. Despite being a Catholic who attended Mass at least weekly and reported that her religious beliefs were very important to her, Linda’s explanation made clear that her concern was not whether her daughter had divorced and remarried, but the men she had chosen as her partners:

Disappointed? I would say Katherine. Well, she had a divorce and I never said anything. But I felt she was choosing the wrong person [laughs]. [Oh, you mean at the beginning?] At the beginning. And she’s remarried, and I feel that she’s made the same mistake even though I wouldn’t say a thing.

Similarly, Margaret’s concern regarding Joyce, the eldest of her three daughters, was Joyce’s choice of a poor partner. Joyce’s partner choice was especially vexing to Margaret because she had advised her daughter against marrying this man:

Well because, it’s her fault she married this drinker. And they divorced. I told her, you know how mothers tell, you know? She wouldn’t listen. She met him very younger, she was about 18, and he was [already] a loser.

As Margaret’s comments make clear, even Joyce’s termination of the marriage was not sufficient to fully alleviate her mothers’ disappointment in the partner choice that Joyce had made almost three decades earlier.

Theresa, a mother of one son and one daughter, also explained her disappointment in her daughter, Lisa, as resulting from poor marital choices. However, although she disliked Lisa’s husband, Theresa was ambivalent about her daughter’s later divorce. However, despite being a Catholic who said that her religious beliefs were very important to her, the ambivalence emanated from her concern that her daughter, who divorced in her late 40s, might have waited too long and lost other opportunities, and thus should have fought harder to remain together:

Lisa was married to somebody who really did a job on her, and she stuck it out. And she would never had left had he’d been willing to stay…. [I]t was very difficult for her to go through this divorce…. Looking back, I wish she hadn’t. I felt like she wasted many good years of her life staying with him…. Actually at the time I was proud of her stamina and her attitude, but I just wish for her sake she hadn’t [made it] so easy [for him to leave her].

Taken together, the mothers’ explanations for their disappointment in their daughters revealed their concerns with the decisions their daughters had made, most often in choosing poor partners, but sometimes even in the choices they made about terminating those marriages, despite their poor choices. Thus, although the quantitative findings suggest only that remaining in marriage reduced the likelihood of adult children being identified as those in whom their mothers are the most disappointed, analysis of the qualitative data revealed a more complex pattern, both in the greater concern about daughters’ than sons’ marriages and in the greater salience of the type of marriages their daughters had rather than their simply being married.

Discussion

The central aim of this article was to expand the study of parental differentiation in later-life families in two new directions. First, we compared predictors of mothers’ reports of favoritism and disfavoritism regarding their adult children. Second, we proposed a conceptual distinction between relational and evaluative dimensions of favoritism and disfavoritism and tested the degree to which this distinction shaped the bases on which mothers differentiated among their children. The four dimensions of differentiation considered were (a) to which child the mother felt the most emotional closeness (relational favoritism), (b) with which child she experienced the greatest conflict (relational disfavoritism), (c) of which child she felt the most proud (evaluative favoritism), and (d) in which child she was the most disappointed (evaluative disfavoritism). For all four dimensions, differentiation was measured by the mother’s responses to questions asking her to name a particular child from among all of her offspring.

We framed our research questions drawing from key concepts of the life course perspective. These concepts included children’s attainment of adult social structural positions, similarity between mothers and children, and exchanges of support (Suitor et al., 2011). On the basis of this framework, as well as the literature on intergenerational relations and within-family differences in adulthood, we hypothesized that mothers’ differentiation regarding both relational dimensions would be predicted by a combination of gender value similarity and children’s provision of support. In the case of conflict, we also expected differentiation would also be shaped by normative adult achievements and deviant behaviors. We proposed that mothers’ differentiation regarding both evaluative dimensions of the relationship would be predicted by normative adult achievements, the avoidance of deviant behaviors, value similarity, and children’s support.

The pattern of findings from the quantitative analyses provided only partial support for the hypotheses for relational dimensions of mothers’ favoritism and disfavoritism. As expected, mothers reported being most emotionally close to daughters and to children who shared their values; however, neither provision of instrumental nor expressive support predicted mothers’ choices. Also as hypothesized, mothers reported experiencing the greatest conflict with daughters, and they were unlikely to name children who shared their values. Mothers also reported the least conflict with children who remained married across the study. But contrary to expectations, mothers’ choices of greatest conflict were not predicted by achievement of any other adult statuses, deviant behaviors, or provision of support. Thus, hypotheses regarding similarity of values and gender were supported, whereas those for other predictors were not.

The findings from these analyses also provided only partial support for the hypotheses regarding evaluative dimensions of favoritism and disfavoritism. As was the case for relational dimensions, value similarity predicted both evaluative dimensions, with mothers reporting the greatest pride in children who shared their values and the greatest disappointment in children who did not. Also consistent with our hypotheses, recent deviant behaviors increased the likelihood of children being named as those in whom the mothers were most disappointed and decreased the likelihood of their being those in whom the mothers were most proud. However, contrary to expectations, only one of the normative adult achievements—remaining married—predicted either evaluative dimension, and then only in the case of reducing disappointment.

Thus, consistent with previous research on both between- and within-family studies (Suitor et al., 2011; Suitor & Pillemer, 2006; Suitor et al., 2013), value similarity emerged as the most salient factor shaping mothers’ differentiation across all four dimensions of favoritism and disfavoritism—a pattern reflecting the prominence given to this factor in Bengtson’s classic model of intergenerational solidarity (Silverstein & Bengtson, 1997).

Gender also played an important role across three of the four dimensions of favoritism and disfavoritism in the present study, increasing the likelihood of being named for emotional closeness as well as for conflict, as expected, and decreasing the likelihood of being named for disappointment, which we did not anticipate. The finding for disappointment was surprising, given that the few studies that included disappointment found no difference by gender (Aldous et al., 1985; Cichy et al., 2013). Further, this finding could not be explained simply by the fact that daughters are less likely to engage in deviant behaviors. Classic theories of gender and interpersonal relations, particularly those developed by Chodorow (1978), suggest that this pattern may be because daughters are more likely to emulate their mothers, thus resulting in mothers feeling that their daughters are fulfilling their expectations.

Another pattern particularly worthy of note involves children’s deviant behaviors in adulthood. Although it might be expected that deviant behaviors in adulthood would shape mothers’ differentiation for both relational and evaluative dimensions, such does not appear to be the case. The finding that mothers were substantially less likely to name deviant offspring as those in whom they had the greatest pride and more likely to name those in whom they were disappointed is not surprising. Nevertheless, documenting this pattern is important, given that evaluative dimensions, especially disappointment, predict adult children’s depressive symptoms (Suitor et al., 2015). The more counterintuitive finding is that recent deviant behaviors did not predict which offspring mothers chose for emotional closeness or conflict. This result is consistent with findings that mothers are no more likely to be estranged from children who engaged in these behaviors than from other offspring (Gilligan, Suitor, & Pillemer, 2015). In that work, as in the present findings, violation of mothers’ values, rather than specific behaviors, fueled mothers’ negative sentiments toward their adult children.

A unique contribution of the present study to the literature on within-family differences in adulthood are the findings revealed by the qualitative analysis. Examination of the mothers’ explanations for why they selected particular offspring reinforced the findings of the quantitative analyses in some regards and shed new light on these processes in others. In the case of mothers’ explanations for favoring and disfavoring particular offspring for emotional closeness, conflict, and pride, the qualitative data reflected the patterns shown by the quantitative analyses. However, in the case of disappointment, the qualitative data revealed two intriguing patterns.

The first of these patterns involved educational and occupational achievements. Although neither educational attainment nor employment status predicted which children mothers named as those in whom they were most disappointed, examination of the mothers’ explanations for their choices revealed that they were very concerned with whether children had reached the benchmarks they had set for them, regardless of whether benchmarks were consistent with those set by societal norms. For example, in some cases, mothers were disappointed in children who had achieved high levels of education but did not “make good use” of their education. Further, in some cases, mothers were disappointed that their children did not seek better opportunities, whereas in others, mothers were disappointed that their children had not achieved the occupational stability that the mothers valued.

The other pattern focused on mothers’ concerns regarding the role of marriage in their daughters’ lives. Although separate multivariate analyses by gender showed no consistent differences in predictors for sons and daughters, the qualitative data revealed that when mothers reported daughters as the offspring in whom they were most disappointed, they expressed concern regarding their daughters’ marital and partner choices. As in the case of educational and occupational achievements, the discrepancy between the quantitative and qualitative findings regarding marriage for daughters lay in the mothers’ concern with their daughters’ marital or partner choices, rather than their marital statuses. Although some mothers were concerned with whether their daughters were married, the majority who were most disappointed in daughters expressed dismay regarding the daughters’ choices in selecting problematic partners, engaging in affairs, or being the ones to initiate dissolutions.

Taken together, the combination of quantitative and qualitative data point to the high salience of mothers’ values in explaining mothers’ differentiation, regardless of whether the mothers are considering relational of evaluative dimensions of favoritism or disfavoritism. Sharing mothers’ values not only increases the likelihood of being favored and decreases the likelihood of being disfavored, but the violation of mothers’ values plays a role in the conditions under which normative adult achievements, such as education, employment, and marriage, shape favoritism and disfavoritism.

A second contribution of the present analysis to the study of parental differentiation in adulthood is the distinction between favoritism and disfavoritism. Previous research on within-family differences in adulthood has generally involved creating measures in which favoritism and disfavoritism are both conceptualized and operationalized as opposite ends of the same continuum. For example, adult children are often asked to rate themselves relative to a target sibling on dimensions such as closeness, recognition, or provision of support (Boll, Ferring, & Fillipp, 2003, 2005; Boll, Michels, Ferring, & Filipp, 2010; Jensen et al., 2013). Difference scores are then created and used to identify which sibling is “favored,” that is, has a higher score than his or her sibling, or is “disfavored,” that is, has a lower score than his or her sibling. The approach used in the present study differs from these approaches in that respondents were asked separately about favoritism and disfavoritism, and comparisons were made among all offspring rather than only between two particular siblings.

An implication of asking separately about favoritism and disfavoritism, as well as allowing for the selection of any member of the sibship, is that these procedures allow for the possibility that the same child could be both favored and disfavored. However, as shown by the findings we presented on overlap between dimensions, such multiplexity is relatively low, especially for the combination of positive and negative dimensions.

The focus of this article is investigating which characteristics of children and of the parent–adult child dyad predict mothers’ favoritism and disfavoritism; however, it is worth noting that some family-level characteristics played a role in these processes. Although family-level characteristics, such a family size, race, and proportion of daughters, cannot predict which offspring mothers were more likely to favor or disfavor, these characteristics can shed light on the conditions under which mothers differentiate. The multivariate analyses revealed that mothers were less likely to name any specific child in larger families across all four dimensions of favoritism and disfavoritism. This might suggest that mothers are less sensitive to differences among their offspring in larger families, or it might simply reflect the decreased probability of choosing any particular child when there are more to choose among. Although assessing the validity of these competing arguments is beyond the scope of the present article, separate analyses have shown that the predictors of favoritism and disfavoritism do not vary by family size (Suitor & Pillemer, 2007). Both race and the proportion of daughters predicted whether mothers chose any specific offspring for some dimensions; however, only in the case of family size was there any consistent pattern of favoritism and disfavoritism, which makes it difficult to interpret the inconsistent findings for the other family-level characteristics.

The present study has extended our understanding of the predictors of mothers’ favoritism and disfavoritism in later-life families; nevertheless, we recommend that future research will pursue questions that we could not address. First, studies should explore whether the patterns reported here are found when studying fathers’ differentiation among their offspring. Previous research focusing on only emotional closeness and confiding has found that although mothers and fathers are equally likely to differentiate among their offspring, the predictors of such differentiation vary by parents’ gender, with mothers placing much greater emphasis on similarity of values and gender (Suitor & Pillemer, 2013). Such differences by parents’ gender may also play a role in fathers’ conflict, pride, and disappointment.

We also hope that future research will examine patterns of favoritism and disfavoritism across time. Thus far, the stability of mothers’ differentiation in the later years has been investigated only in the case of emotional closeness and preferences for care (Suitor et al., 2013). Given the role of mothers’ differentiation in adult children relational and psychological well-being (Davey et al., 2009; Jensen et al., 2013; Pillemer et al., 2010; Suitor et al., 2009; Suitor et al., 2015), studying the stability of parental differentiation across a wider range of dimensions may shed important light on life course variations in well-being as children move across the adult life course. Because the WFDS includes mothers’ differentiation regarding evaluative dimensions of favoritism and disfavoritism only at T2, addressing this question was beyond the scope of the present article. We hope that future research will investigate these patterns.

Taken together, the findings we have presented provide further evidence of the importance of considering the variations in parent–child ties within the family. We hope that family scholars will continue to extend the study of parents’ differentiation among their children in later life. Understanding the complex patterns underlying mothers’ favoritism and disfavoritism is likely to shed new light on children’s relational and psychological well-being across the life course.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by grants from the National Institute on Aging (2RO1 AG18869-04), J. J. Suitor and K. Pillemer (co-PIs). J. Suitor, S. Peng, G. Con, and M. Rurka also wish to acknowledge support from the Center on Aging and the Life Course at Purdue. K. Pillemer acknowledges support from an Edward R. Roybal Center grant from the National Institute on Aging (1 P50 AG11711-01). We would like to thank Paul Allison for his helpful suggestions regarding the data analysis, and Mary Ellen Colten and her colleagues at the University of Massachusetts, Boston, for collecting the data for the project.

Contributor Information

J. Jill Suitor, Purdue University.

Megan Gilligan, Iowa State University*.

Siyun Peng, Purdue University**.

Gulcin Con, Purdue University**.

Marissa Rurka, Purdue University**.

Karl Pillemer, Cornell University***.

References

- Aldous J, Klaus E, Klein DM. The understanding heart: Aging parents and their favorite children. Child Development. 1985;56(2):303–316. doi: 10.2307/1129721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allison PD. Missing data. In: Wright J, Marsden P, editors. Handbook of survey research. Bingley, UK: Emerald; 2010. pp. 631–658. [Google Scholar]

- Bengtson VL. Beyond the nuclear family: The increasing importance of multigenerational bonds. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2001;63(1):1–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2001.00001.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bengtson VL, Kuypers JA. Generational difference and the developmental stake. Aging & Human Development. 1971;2(4):249–260. doi: 10.2190/AG.2.4.b. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Birditt KS, Fingerman KL. Parent–child and intergenerational relationships in adulthood. In: Fine MA, Fincham FD, editors. Handbook of family theories: A content-based approach. New York, NY: Routledge; 2013. pp. 71–86. [Google Scholar]

- Birditt KS, Tighe LA, Fingerman KL, Zarit SH. Intergenerational relationship quality across three generations. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2012;67(5):627–638. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbs050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boll T, Ferring D, Filipp SH. Perceived parental differential treatment in middle adulthood: Curvilinear relations with individuals’ experienced relationship quality to sibling and parents. Journal of Family Psychology. 2003;17(4):472–487. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.17.4.472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boll T, Ferring D, Filipp SH. Effects of parental differential treatment on relationship quality with siblings and parents: Justice evaluations as mediators. Social Justice Research. 2005;18(2):155–182. doi: 10.1007/s11211-005-7367-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boll T, Michels T, Ferring D, Filipp SH. Trait and state components of perceived parental differential treatment in middle adulthood: A longitudinal study. Journal of Individual Differences. 2010;31(3):158–165. doi: 10.1027/1614-0001/a000024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Borkan J. Immersion/crystallization. In: Crabtree B, Miller W, editors. Doing qualitative research. Vol. 2. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1999. pp. 179–194. [Google Scholar]

- Carr D. The psychological consequences of midlife men’s social comparisons with their young adult sons. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2005;67:240–50. [Google Scholar]

- Chodorow N. The reproduction of mothering. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Cichy KE, Lefkowitz ES, Davis EM, Fingerman KL. “You are such a disappointment!”: Negative emotions and parents’ perceptions of adult children’s lack of success. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2013;68(6):893–901. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbt053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Condry R. Families shamed: The consequences of crime for relatives of serious offenders. Cullompton, UK: Willan; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell JW, Clark VLP. Designing and conducting mixed methods research. 2. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Davey A, Tucker CJ, Fingerman K, Savla J. Within-family variability in representations of past relationships with parents. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2009;64B(1):125–136. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbn001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg M, Hetherington EM. Differential parenting as a within-family variable. Journal of Family Psychology. 2001;15(1):22–37. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.15.1.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fingerman KL, Cheng YP, Birditt K, Zarit S. Only as happy as the least happy child: Multiple grown children’s problems and successes and middle-aged parents’ well-being. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2012;67B(2):184–193. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbr086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gans D, Silverstein M. Norms of filial responsibility for aging parents across time and generations. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2006;68(4):961–976. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2006.00307.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gilligan M, Suitor JJ, Kim S, Pillemer K. Differential effects of perceptions of mothers’ and fathers’ favoritism on sibling tension in adulthood. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2013;68(4):593–598. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbt039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilligan M, Suitor JJ, Pillemer K. Recent economic distress in midlife: Consequences for adult children’s relationships with their mothers. In: Claster PN, Blair SL, editors. Contemporary perspectives in family research: Visions of the 21st century family—transforming structures and identities. Vol. 7. Bingley, UK: Emerald; 2013. pp. 159–184. [Google Scholar]

- Gilligan M, Suitor JJ, Pillemer K. Estrangement between mothers and adult children: The roles of norms and values. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2015;77:908–920. doi: 10.1111/jomf.12207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green KM, Ensminger ME, Robertson JA, Juon HS. Impact of adult sons’ incarceration on African American mothers’ psychological distress. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2006;68(2):430–441. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2006.00262.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield EA, Marks NF. Linked lives: Adult children’s problems and their parents’ psychological and relational well-being. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2006;68(2):442–454. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2006.00263.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grusec JE. Parental socialization and children’s acquisition of values. In: Bornstein MH, editor. Handbook of parenting: Vol. 5. Practical issues in parenting. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Heck RH, Thomas S, Tabata L. Multilevel modeling of categorical outcomes using IBM SPSS. London, UK: Routledge Academic; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins J, Rasbash J, Leckie G, Gass K, Dunn J. The role of maternal factors in sibling relationship quality: A multilevel study of multiple dyads per family. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2012;53(6):622–629. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2011.02484.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen AC, Whiteman SD, Fingerman KL, Birditt KS. “Life still isn’t fair”: Parental differential treatment of young adult siblings. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2013;75(2):438–452. doi: 10.1111/jomf.12002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RS. Emotions and interpersonal relationships: Toward a person-centered conceptualization of emotions and coping. Journal of Personality. 2006;74(1):9–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2005.00368.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHale SM, Updegraff KA, Jackson-Newsom J, Tucker CJ, Crouter AC. When does parents’ differential treatment have negative implications for siblings? Social Development. 2000;9(2):149–172. doi: 10.1111/1467-9507.00117. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McHale SM, Updegraff KA, Tucker CJ, Crouter AC. Step in or stay out? Parents’ roles in adolescent siblings’ relationships. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2000;62(3):746–760. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2000.00746.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Merz EM, Schuengel C, Schulze HJ. Intergenerational relations across 4 years: Well-being is affected by quality, not by support exchange. Gerontologist. 2009;49(4):536–548. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnp043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neal MB, Hammer LB, Morgan DL. Using mixed methods in research related to work and family. In: Pitt-Catsouphes M, Kossek EE, Sweet S, editors. The work and family handbook: Multidisciplinary perspectives and approaches. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2006. pp. 587–606. [Google Scholar]

- Pillemer K, Suitor JJ, Pardo S, Henderson C. Mothers’ differentiation and depressive symptoms among adult children. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2010;72(2):333–345. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00703.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plano Clark VL, Huddleston-Casas CA, Churchill SL, O’Neil Green D, Garrett AL. Mixed methods approaches in family science research. Journal of Family Issues. 2008;29(11):1543–1566. doi: 10.1177/0192513x08318251. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Richmond MK, Stocker CM, Rienks SL. Longitudinal associations between sibling relationship quality, parental differential treatment, and children’s adjustment. Journal of Family Psychology. 2005;19(4):550–559. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.19.4.550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryff CD, Schmutte PS, Lee YH. How children turn out: Implications for parental self-evaluation. In: Ryff CD, Seltzer MM, editors. The parental experience in midlife. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1996. pp. 383–422. [Google Scholar]

- Schenk N, Dykstra PA. Continuity and change in intergenerational family relationships: An examination of shifts in relationship type over a three-year period. Advances in Life Course Research. 2012;17(3):121–132. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.alcr.2012.01.004. [Google Scholar]

- Sechrist J, Suitor JJ, Howard AR, Pillemer K. Perceptions of equity, balance of support exchange, and mother–adult child relations. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2014;76(2):285–299. doi: 10.1111/jomf.12102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shanahan L, McHale SM, Crouter AC, Osgood DW. Linkages between parents’ differential treatment, youth depressive symptoms, and sibling relationships. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2008;70(2):480–494. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2008.00495.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Silverstein M, Bengtson VL. Intergenerational solidarity and the structure of adult child–parent relationships in American families. American Journal of Sociology. 1997;103(2):429–460. [Google Scholar]

- Silverstein M, Giarrusso R. Aging and family life: A decade review. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2010;72(5):1039–1058. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00749.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suitor JJ, Gilligan M, Johnson K, Pillemer K. Caregiving, perceptions of maternal favoritism, and tension among siblings. Gerontologist. 2014;54(4):580–588. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnt065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suitor JJ, Gilligan M, Peng S, Jung JH, Pillemer K. Role of perceived maternal favoritism and disfavoritism in adult children’s psychological well-being. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 2015 doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbv089. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suitor JJ, Gilligan M, Pillemer K. Continuity and change in mothers’ favoritism toward offspring in adulthood. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2013;75(5):1229–1247. doi: 10.1111/jomf.12067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suitor JJ, Pillemer K. Choosing daughters: Exploring why mothers favor adult daughters over sons. Sociological Perspectives. 2006;49(2):139–161. doi: 10.1525/sop.2006.49.2.139. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Suitor JJ, Pillemer K. Mothers’ favoritism in later life: The role of children’s birth order. Research on Aging. 2007;29(1):32–55. doi: 10.1177/0164027506291750. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Suitor JJ, Pillemer K. Differences in mothers’ and fathers’ parental favoritism in later-life: A within-family analysis. In: Silverstein M, Giarrusso R, editors. Kinship and cohort in an aging society: From generation to generation. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2013. pp. 11–31. [Google Scholar]

- Suitor JJ, Sechrist J, Gilligan M, Pillemer K. Intergenerational relations in later-life families. In: Settersten RA, Angel JL, editors. Handbook of sociology of aging. New York, NY: Springer; 2011. pp. 161–178. [Google Scholar]

- Suitor JJ, Sechrist J, Pillemer K. When mothers have favorites: Conditions under which mothers differentiate among their adult children. Canadian Journal on Aging. 2007;26:85–99. doi: 10.3138/cja.26.2.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suitor JJ, Sechrist J, Plikuhn M, Pardo ST, Gilligan M, Pillemer K. The role of perceived maternal favoritism in sibling relations in midlife. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2009;71(4):1026–1038. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2009.00650.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suitor JJ, Sechrist J, Plikuhn M, Pardo S, Pillemer K. Within-family differences in parent–child relations across the life course. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2008;17:334–338. [Google Scholar]