Abstract

Purpose

South Asians (Indians, Pakistanis, Bangladeshis, Sri Lankans, Nepalis, and Bhutanese) in the United States have a very high prevalence of type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM). This pilot study evaluated a culturally-tailored exercise intervention among South Asian immigrant mothers with DM risk factors.

Methods

Through an academic-community partnership, South Asian women with risk factors for DM and who had at least one child between 6-14 years were enrolled into this single-arm study. The intervention for the mothers included 16-weeks of twice weekly exercise classes, self-monitoring with activity trackers, goal-setting, and classes on healthy eating. Based on prior community-based participatory research, children were offered exercise classes during the mothers' classes. The primary efficacy outcomes were change in mothers' moderate/vigorous physical activity and body weight pre- and post-intervention (16-weeks). Program adherence, clinical, and psychosocial outcomes were measured. A qualitative process evaluation was conducted to understand participant perspectives.

Results

Participants' (n=30) average age was 40 (SD=5) years., 57% had a high school education or less, and all were overweight/obese.. At baseline, women were not meeting recommended physical activity guidelines. Overall, participants attended 75% of exercise classes. Compared to baseline, participants' weight decreased by 3.2 lbs. (95% CI: −5.5, −1.0) post-intervention. Among women who attended at least 80% of classes (n=17), weight change was −4.8 lbs, (95% CI: −7.7, −1.9). Change in accelerometer-measured physical activity was not significant; however exercise-related confidence increased from baseline (p-value <0.01). Women described multiple physical and psychosocial benefits from the intervention.

Conclusion

This pilot study suggests that a culturally-tailored exercise intervention that included exercise classes for children was feasible and had physical and psychosocial benefits in South Asian mothers with risk factors for DM.

Keywords: Physical activity, cultural-tailoring, South Asian, diabetes, cardiovascular disease

Introduction

South Asians (individuals from India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Nepal, Sri Lanka and Bhutan) are the fastest growing racial/ethnic minority group in the United States (U.S.).(31) Studies show that South Asians have a significantly higher prevalence of type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM) than non-Hispanic Whites, Blacks, and Hispanics.(15, 23, 36) Although genetics may play a role, reducing the burden of DM in South Asians requires addressing lifestyle risk factors such as poor diet, physical inactivity, and overweight/obesity.(15) Importantly, South Asians are some of the least physically active adults in the U.S. (36) Further, they are prone to developing DM even with a small amount of weight gain.(3) Clearly, targeted public health efforts are needed to prevent DM in the 3.8 million South Asians living in the U.S.

Although physical inactivity is common in the U.S., South Asians may require special considerations when designing and implementing physical activity programs. The vast majority of South Asians are immigrants, and studies show a mismatch between South Asian immigrants' sociocultural context and mainstream approaches to physical activity promotion.(8, 11) South Asian women, in particular, report little physical activity and have difficulty defining exercise.(11) Our prior community-based participatory research (CBPR) found that social and cultural norms, rigid gender roles, and lack of social and family support strongly influenced South Asian women's proclivity for physical inactivity.(11) Despite these barriers, South Asian women were willing to participate in exercise if it could be done in women-only classes and in a trusted community setting. Women also said that their children often encouraged them to do more exercise and that exercising with their children was a motivating factor. Exercise interventions that incorporate this larger sociocultural context are needed to maximize reach and effectiveness in the high risk and rapidly growing South Asian population.

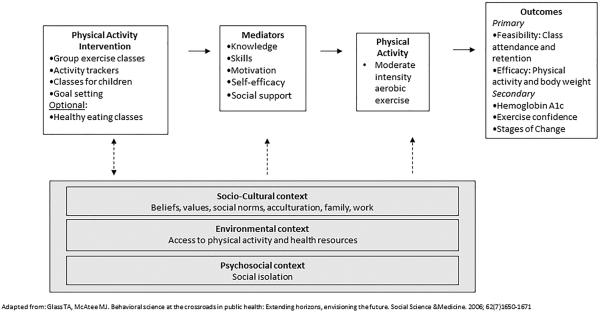

In partnership with the community partner (Metropolitan Asian Family Services-MAFS), we adapted and applied evidence-based behavior change principles to develop a culturally-tailored exercise intervention for South Asian mothers that would include their children. Although regular physical activity is an evidence-based DM prevention strategy,(18, 35) translating this evidence across diverse populations and settings is a major challenge. This study directly addresses the challenge by using CBPR methods and a social determinants framework (Figure 1) to engage South Asian women in regular, structured physical activity.

Figure 1.

Conceptual Model for Intervention Development

Methods

Primary research goals

The primary research goal was to pilot-test the 16-week exercise intervention using a non-randomized design to examine feasibility and intial efficacy among South Asian mothers with risk factors for DM. The primary efficacy outcomes were pre-post intervention change in mothers' physical activity and weight. Secondary outcomes included pre-post intervention change in clinical risk factors and exercise-related stages of change and self-efficacy. A qualitative evaluation was used post-intervention to understand participants' experiences and perceptions of the intervention.

Study framework

This study builds on CBPR principles which contributed to the feasibility and sustainability of the intervention.(7) MAFS and academic partner (Northwestern University-NWU) collaboratively chose the focus of this research because it was relevant and responsive to the needs of this South Asian community. MAFS is a not-for-profit, community-based organization that provides comprehensive and integrated social services to immigrants. The organization serves about 1300 South Asian families, and all fall below 100% of the federal poverty level. MAFS and NWU had previously worked together on formative research to understand community needs and the sociocultural context of physical activity in this community.(12, 16, 32) A third community partner, Ultimate Martial Arts (UMA), was also involved in this study. UMA is a fully equipped fitness facility with certified exercise instructors and was primarily involved to help deliver the exercise classes for mothers and children.

MAFS, UMA, and NWU developed a memorandum of understanding and all partners engaged in formal capacity building activities (e.g., trainings on human subjects research and study protocols and cultural competency training for exercise instructors). MAFS was also involved in study design, review of study materials and questionnaires to ensure cultural equivalence, implementation, recruitment and retention of participants, and evaluation. The study protocol and procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board at Northwestern University.

Participants and setting

The majority of participants in this study were from India (77%) and Pakistan (20%). Indians and Pakistanis comprise 90% of South Asians in the U.S. and in the Rogers Park neighborhood of Chicago, IL,(25, 30) where the study took place. Rogers Park is a major entry hub for South Asian immigrants,(25) many of whom are medically underserved, meaning that they face economic, linguistic, and cultural barriers to health care.(5) The study was conducted at MAFS, which has an office in the Rogers Park neighborhood, and UMA which is an exercise facility located approximately 3 miles away from Rogers Park.

Eligibility and recruitment procedures

South Asian women with children between the ages of 6 and 14 years and who had 1 or more risk factors for developing future DM (body mass index ≥25kg/m2, and/or a personal history of gestational DM, and/or first-degree relative with DM) were eligible to participate in the study.(2) Only women who spoke Hindi or English were included in the study because these are two of the most common languages spoken by South Asians in Chicago. In addition, the study team had the capacity and knowledge to translate documents for this pilot study into Hindi, but not multiple South Asian languages. Women who had a self-reported diagnosis of DM and/or were on DM medications, had a BMI ≥35kg/m2, blood pressure over 160/100 mm Hg, or were currently pregnant were excluded from participating. In addition, we used the Exercise Assessment and Screening for You (EASY) Tool to screen women for conditions that might impact safe exercise, such as cardiac disease, uncontrolled blood pressure, or musculoskeletal conditions that could be exacerbated by exercise.(26) Three women had comorbidities that prevented moderate intensity physical activity and were excluded.

MAFS staff conducted outreach and recruitment at community sites and events. Participants who regularly use services at MAFS were also contacted for recruitment. Interested and eligible participants were invited to participate in the baseline assesments where written informed consent was obtained.

Intervention design and class content

The study partners developed the exercise intervention by integrating evidence-based behavioral strategies(4) with unique culturally-specific strategies based on formative CBPR(11) (Table 1). A conceptual model, relating individual, social and environmental factors to physical activity was also used to guide intervention planning and development (Figure 1). The primary evidence-based goals of the intervention were for women to achieve 150 minutes of moderate intensity physical activity/week and weight loss.(18)

Table 1.

Development of Exercise Intervention for South Asian Women

| Culturally specific strategies | Evidence-based behavioral strategies |

|---|---|

|

| |

| 1. Women's only exercise classes | 1. Group exercise classes for social support and role modeling |

| 2. Exercise classes for children | 2. Self-monitoring with Fitbit© wireless activity tracker |

| 3. Community partnerships | 3. Goal-setting for physical activity outside the class |

| 4. Classes at a convenient location in the community | 4. Feedback and reinforcement from study staff using reports generated from Fitbit© data |

| 5. Sensitivity to cultural values, i.e. modesty and gender roles | |

| 6. Classes advertised as fitness and exercise, not dance classes | |

| 7. Music during classes had no inappropriate content | |

| 8. Culturally appropriate dietary advice | |

| 9. Bilingual, culturally concordant study staff | |

Every week, participants were required to attend a minimum of two exercise classes (classes were held three times per week to accommodate schedules). Certified exercise instructors conducted classes at MAFS and UMA. Instructors led participants in 45 minutes of moderate intensity exercise drawing on Zumba® and aerobics. Classes began with a warm-up and ended with a cool-down period. To accommodate previously sedentary women, the intervention used a discontinuous protocol,(13) meaning that participants could rest as needed during class and rejoin the class once ready. Participants were instructed on how to gradually increase the amount and intensity of physical activity to achieve the 150 minutes of moderate intensity physical activity/week. Study staff also participated in the exercises classes to help with translation into Hindi because one instructor did not speak Hindi.

To increase group cohesion and social support, weekly exercise classes began with one participant sharing her reasons for participating and perceived benefits. In addition, the study team held biweekly contests where the top three participants were recognized during the exercise classwith a certificate for achieving the contest goal. Examples include: “most improved step count,” “best 2-minutes exercise routine,” and “best attendance.”

In this study, children were not a target of the intervention. The exercise classes for the children were used as a culturally-tailored strategy to increase mothers' engagement and participation in the exercise intervention. All participants were given the option to enroll their children between ages 6-14 years in a free exercise class at UMA which was at the same time as the mother's exercise classes. The children's classes included 12 weeks of martial arts and 4 weeks of yoga. Mothers were required to attend the women's exercise class if their child was participating in the children's class.

Other intervention components

Participation in other intervention components was optional, but encouraged. Participants were given a Fitbit Zip™ wireless activity tracker and were taught how to use it to self-monitor daily step counts. Study staff provided participants with a bi-weekly report of their steps counts. Reports included a motivational message and recommended an individually tailored step goal, based on the prior weeks' step counts, for increasing the number of daily steps.

As part of the study, women were given the option of attending two group classes about healthy eating where study staff provided culturally-tailored information on portion control, reducing saturated fat and salt in diet, and a healthy South Asian dietary pattern. These classes were conducted in Hindi and English by the bilingual project staff. Forty percent of women attended these classes.

Transportation to and from the exercise classes was provided by MAFS, and class attendance was also incentivized. At the end of the 16 weeks, women who attended at least 75% of the exercises classes (24/32)were given a $50 prize and those who attended 90% (29/32) received a $75 prize. The amount of the incentive and potential for coercion was discussed by study partners, MAFS and NWU; both agreed it was important to incentivize a high level of attendance and agreed on an appropriate amount.

Study measurements

We assessed all outcomes of mothers at baseline (pre-intervention) and within 2 weeks post-intervention (i.e., at week 17 to 18). At baseline, we obtained demographic information and a brief medical history. Trained, bilingual research assistants administered questionnaires and performed blood pressure and anthropometric (height and weight) measurements using standardized protocols (17, 24) and calibrated equipment.

Physical activity was assessed using accelerometers and self-report.(1) Accelerometers (Actigraph, model 7164) were worn by study participants at baseline and post-intervention for 7 consecutive days. We examined change in bout-corrected moderate-vigorous physical activity. For comparison with national physical activity recommendations, 10-min activity bouts were defined as 10 or more consecutive minutes above the relevant threshold, with allowance for interruptions of 1 or 2 min below threshold. This is referred to as a modified 10-min bout. In order for a day of accelerometry to be used in our analyses, the participant had to wear the Actigraph for at least 10 hours. The Fitabase platform was used to collect, aggregate, and export data on daily step counts from the Fitbit Zip™ activity trackers. Forty percent of women had smart phones, and study staff assisted them with downloading the Fitbit™ application to their phones to self-monitor activity. Women who did not have smartphones were provided instructions on how to sync their Fitbit™ on their personal computers; however, none of them used their personal computers to sync their Fitbit™.

Participants underwent a venous blood draw to measure hemoglobin A1C at baseline and post-intervention. We used established questionnaires to measure exercise-related confidence(28) and readiness to exercise.(20) All study questionnaires were translated into Hindi by study staff and reviewed and discussed by the study team to ensure cultural equivalency. Participants received a total of $45 after returning the accelerometers at the pre- and post-assessments. Study staff tracked attendance. Children's attendance in exercise classes was tracked, but no other measurements were performed on the children.

Statistical Analysis

Adherence was measured as class attendance and data were analyzed using SAS version 9.4. For all the pre- and post-intervention measures, descriptive statistics were used to summarize the variable. To test for differences in physical activity, we used mixed-effects models for pre- and post-intervention accelerometer data. In these models, the outcome was daily minutes of bout-corrected moderate-vigourous physical activity. Time (pre/post-intervention) was treated as a binary variable in order to measure changes in physical activity. Models controlled for accelerometer wear time and weekend day. Changes in clinical and psychosocial outcomes and self-reported physical activity were also compared by pre-and post-intervention using t-tests. Tests were considered significant if the 2-sided p value was <0.05.

Qualitative Process Evaluation

Bilingual staff not involved in intervention delivery or outcome assessment conducted qualitative interviews with a random sample of participants (n=6), stratified by attendance, to understand participants' perceptions of intervention components and the barriers and facilitators to exercise. A semi-structured interview guide was used and interviews were conducted in the participants' preferred language. All interviews were digitally recorded, translated and transcribed, and the content was analyzed for emerging themes. Two team members independently read the transcripts and compiled themes using thematic analysis. Any areas of disagreement were discussed and resolved with the study principal investigator and other study staff.

Results

Participants were enrolled into the study from November 2014 to February 2015. Participant outreach and recruitment is illustrated in Figure 2. Of the 200 women who were screened for eligibility, 55 met inclusion criteria and 30 were enrolled into the study. The intervention was conducted between February-June 2015 with follow-up assessments in June 2015.

Figure 2.

Flow of participants from outreach to completion, Chicago, IL. November 2014–June 2015

Overall, the participants' average age was 40 (SD±5) years, 57% had a high school education or less, and slightly more than one-third were limited English proficient (Table 2). The majority of women in this study were Muslim, married, and had been living in the U.S. an average of 11(SD±8) years. All women had at least 1 child enrolled in the exercise classes. At baseline, the average BMI of women in the study was 30 kg/m2 (SD±3). Based on our requirement of 10 hours of accelerometer wear time, at baseline only 1 participant wore the accelerometer for less than 4 days. All participants wore the device for 4 or more days at follow-up. Accelerometer data showed that participants were not meeting national physical activity recommendations at baseline (Table 3).

Table 2.

Baseline Characteristics of Women in Exercise Intervention (N=30)

| Participant Demographics | Mean (SD) or % |

|---|---|

| Age, years | 40 (5.0) |

| Muslim | 60% |

| Born outside the United States | 100.0 % |

| Country of Origin: India | 77% |

| Years in the United States | 10 (7.6) |

| Educational Achievement: High school or less | 57% |

| Marital Status: Married | 97% |

| No health insurance | 27% |

| Language of Interview: Hindi | 57% |

| Limited English Proficiency | 37% |

| Family history of diabetes | |

| Parent | 73% |

| Sibling | 13% |

| History of gestational diabetes | 33% |

Table 3.

Change in Outcomes, Pre- and Post-intervention (N=30)

| Primary Outcomes | Baseline | 4 Months | Change | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean Change (95% CI) | P-value* | |

| Weight, lbs | 158.2 (17.8) | 154.5 (17.1) | −3.2 (−5.5, −1.0) | <0.01 |

| Bout-corrected moderate-vigorous physical activity, min/week activity+ | 42 (104) | 58 (117) | 16 (−16, 47) | 0.33 |

| Secondary Outcomes | ||||

| Weight among women who attended at least 80% of classes, lbs (n=17) | 163.3 (19.1) | 158.5 (18.9) | −4.8 (−7.7, −1.9) | <0.01 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 29.5 (2.5) | 28.9 (2.7) | −0.6 (−1.2, −0.1) | 0.03 |

| Self-reported exercise, MET hour/week | 2 (3) | 35 (26) | 32 (23,42) | <0.01 |

| SBP, mmHg | 117 (15) | 118 (16) | 1 (−3, 6) | 0.52 |

| DBP, mmHg | 78 (12) | 76 (11) | −2 (−5, 1) | 0.16 |

| Hemoglobin Alc, % | 5.7 (0.3) | 5.8 (0.3) | 0.1 (0.00, 0.12) | 0.03 |

| Exercise-related confidence | 19 (6) | 23 (4) | 4 (2,6) | <0.01 |

| Readiness to exercise, median (Range 1–5) | 2 | 3 | - | 0.11 |

| 1=Pre-contemplation % | 0 | 3 (10.3) | - | - |

| 2=Contemplation % | 17 (56.7) | 6 (20.7) | - | - |

| 3=Preparation % | 8 (26.7) | 7 (24.1) | - | - |

| 4=Decision/Action % | 0 | 5 (17.2) | - | - |

| 5=Maintenance % | 5 (16.7) | 8 (27.6) | - | - |

P-value was calculated for all variables using a Paired t-test, except for Physical activity stages where a Signed Rank test was used.

Adjusted for wear time and weekend day

Overall, class attendance was 75%, and 57% of the women attended at least 80% of the classes. Thirty-eight children (17 girls and 21 boys) were enrolled in the exercise classes. Sixty-five percent of children attended at least 75% of the exercise classes. Study retention was 100%.

Participants' weight decreased significantly by 3.2 lbs. (95% CI= −5.5, −1.0) post-intervention (Table 3). We observed no significant changes in accelerometer-measured physical activity; however self-reported exercise and exercise-related confidence increased significantly post-intervention (95% CI= 23, 42)). There was a small statistically significant increase in hemoglobin A1c and no change in blood pressure (Table 3). At baseline, the majority of women were in the contemplation stage (57%) of the readiness to exercise scale and 17% were in the action/maintenance stage; post-intervention the percentage of women in the action/maintenance stages increased to 45%, but the difference did not reach statistical significance (p-value=0.11).

In a secondary analysis, we examined change in outcomes among women who attended at least 80% of the classes (n=17), and observed significant weight loss post-intervention (−4.8lbs, 95% CI=−7.7, −1.9) (Table 3). Differences in weight change between women who attended at least 80% of classes and those who attended less than 80% of classes did not achieve significance.. The Fitbit™ activity trackers showed that the average number of steps at the end of first week of the intervention was 3161 per day which doubled to 6700 per day by the last week of the intervention (data not shown).

Process evaluation

The process evaluation revealed themes about participant-centered benefits and considerations for intervention development and implementation in South Asian communities (Table 4).

Table 4.

Participant Experiences and Perceptions of the Intervention

| 1. Physical and psychosocial benefits from intervention |

| 1a. “My body became slimmer, and now I can wear good clothes, I look good. Also my sugar and blood pressure was lowered. Even when I sit down and mop the floor my legs do not hurt.” |

| 1b. “I can do the work that I could not do before, and I am less stressed now and feel happy.” |

| 1c “We get enjoyment. After coming to class, my stress is relieved by talking to each other.” |

| 1d. “I remember the friends more, we were running together and I enjoyed it very much.” |

| 2. Effective intervention components |

| 2a. “I liked the weekly reports, it was encouraging, and if I would see someone else doing better than me, I would try harder and be better than others.” |

| 2b. “The best thing was fitbit steps. My target would be to do 10,000 steps every day.” |

| 2c. “Well, I learned stuff like using less oil and which whole wheat flour to pick. Now we are using all those tips. |

| 3. Facilitators |

| 3a. “Having mother and kids together is a wonderful thing because you know, when I was exercising upstairs; my daughter was downstairs in the karate class. She talked to her doctor and she also told people in her school.” |

| 3b. “I don't think men and women classes should be together, we cannot even jump together.” |

| 3c. “If you say it is a dance class, then they won't come. For our family, our husbands would say,`no don't do it if it is a dance class.” |

| 4. Barriers |

| 4a. “ I missed a lot of classes because my other daughter was just 12 months old, and sometimes she had doctor's appointment or something else was happening.” |

| 4b. “Yes, children were invited, but the instructor for karate was a man, therefore my daughter did not attend.” |

Physical and psychosocial benefits from intervention

Women perceived multiple health benefits from the intervention, encompassing physical, psychological, and social benefits. Women reported that regular exercise increased energy levels and endurance at work and for household chores, “I am a quality inspector, so I have to walk 5 hours. I used to complain to my boss that I am very tired, but now after exercise, my boss says I do not get tired.” They also talked about the benefits of weight loss and feeling more confident physically (Table 4, Quote 1a). Another very common theme was that exercise helped with stress (Table 4, Quotes 1b and 1c).

Effective intervention components

Participants liked group exercise for the social support and encouragement (Table 4, Quotes 1c, 1d). They specifically mentioned group sharing to be motivating, “I liked how every week, everyone used to share experiences and how they benefitted from the program.” Other helpful components that were mentioned included self-monitoring with the activity trackers, receiving feedback on step counts and goals, and learning about healthy eating in conjunction with exercise (Table 4, Quotes 2a–2c).

Facilitators and Barriers

Women said that the exercises classes for their children facilitated their own participation (Table 4, Quote 3a.) and had benefits for their children, “Having your kid together is the most important thing. We cannot take time out and go for exercise when we want. We can go because of the children. Also children get their exercise.” Women were also very clear that they felt comfortable participating in the exercise classes because of sensitivity to cultural values and gender norms (Table 4, Quotes 3b, 3c). Some women said they were unable to attend classes and continue exercising because of competing family priorities (Table 4, Quote 4a). One participant, who attended over 90% of the exercise classes, mentioned that she could not enroll her 14 year-old daughter in the children's class because the martial arts instructors were male (Table 4, Quote 4b).

Discussion

In partnership with community organizations, we used community input, formative data, and a CBPR framework to develop, implement, and pilot-test a culturally-tailored exercise intervention for South Asian mothers with DM risk factors that also included exercise classes for their children. We found that the intervention was feasible for community delivery and that program attendance was high. The participants had a significant increase in self-reported exercise and lost a small amount of weight over the course of the intervention. Although we did not observe a significant change in accelerometer- measured physical activity levels or clinical measures, the intervention effect on physical activity appeared to be in the hypothesized direction with improvements seen from baseline to post-intervention. Importantly, the intervention improved exercise-related confidence significantly, which in prior qualitative research has been identified as a barrier to South Asian women's participation in exercise.(9) Women also perceived multiple physical and psychosocial benefits to the intervention.

One possible explanation for the lack of increase in acceleromoter-measured physical activity is that women may have exercised less once the exercise classes ended. Data from the Fitbit Zip™ activity trackers, which were worn during the intervention period, showed a significant increase in the number of daily steps from the first to the last week of the intervention. In contrast, acceleromters were worn after the exercise classes ended when women no longer had Fitbit Zip™ for self-monitoring or access to a structured physical activity opportunity. The requirement of sustained behavior change is a major challenge in physical activity promotion research.(10) However, this study's process evaluation helped the study team to understand participants' perspectives about which intervention components may have been effective and will be used to inform the next phase of research. The process evaluation themes suggest that potential avenues to increase and sustain physical activity among South Asian women might include: increasing the availability of community exercise programs that meet the cultural values of South Asian women (.e.g., modesty, offering classes for children at the same time); investigating the longer-term efficacy of self-monitoring with activity trackers; and creating virtual social support groups through the use of activity trackers and smartphones to provide the support and motivation that women in this study said was helpful. Sustaining increased physical activity in all segments of the U.S. population will require multimodal behavioral, social, environmental, and policy approaches that are scalable and sustainable.

It is unclear why hemoglobin A1c increased slightly in our study participants, despite weight loss. At baseline, the average hemoglobin A1c among women in this study was 5.7 %, which is the lower limit for a diagnosis of prediabetes. This slight increase reached statistical significance, but would not be considered clinically meaningful.(19) Adding a more intensive dietary component to this intervention may enhance weight loss and promote greater reductions in hemoglobin A1c among South Asian women with risk factors for future development of DM. Another promising area for research is to examine the effect of different types of exercise (aerobic versus resistance versus a combination) on body composition and glycemic outcomes in South Asians. Pilot studies suggest that resistance exercise may confer a greater metabolic benefit in South Asians, who have less muscle mass and more adiposity at a lower BMI than other racial/ethnic groups.(21)

A recent meta-analysis found a dearth of interventions addressing diet, physical activity and overweight/obesity in migrant and native South Asian populations.(6) Two recent studies evaluated the effects of Bollywood dance exercise interventions in South Asian women in the U.S.(22) and Canada.(33) In both studies, the interventions were of shorter duration (12 and 6 weeks respectively) and included mostly Asian Indian women with higher education levels than the women in our study. Both studies demonstrated feasibility and acceptability of Bollywood dance exercise programs for South Asian women and overall, had high participation rates.

Interestingly, during the intervention planning for our study, the community partner and some community members were hesitant to incorporate Bollywood dance into an exercise intervention for South Asian women because of religious and cultural issues related to dance and modesty. The exercise intervention in our study was not advertised as a dance exercise class, but instructors did use South Asian music and Zumba® during the classes. Study staff reviewed the content of the music and activities with the instructors prior to the start of the intervention to ensure that activities were sensitive to the religious and cultural values that had been raised during the CBPR process.(11) The different approaches used in these three studies highlight the cultural, religious, and socioeconomic heterogeneity of the South Asian community and the importance of CBPR when planning lifestyle interventions for South Asian populations.

Strengths and Limitations

There are several strengths of this study. First, the CBPR approach helped to engage and retain underserved South Asian immigrants in a 16-week exercise intervention study; others have reported that recruitment and retention of South Asian immigrants into research studies has been a challenge. (14, 27, 29, 34) In addition, the study team included multilingual and culturally-concordant staff who helped to engage and retain participants throughout the study. We implemented an exercise intervention in a real-world community setting which increased external validity and provided information on strategies needed for future translation of lifestyle intervention research into community settings.

Limitations of this pilot study are inclusion of a single site in Chicago, lack of a control arm, and that we were only able to recruit and enroll 20% of the individuals we approached. Although some participants said they changed their eating habits after attending the optional healthy eating classes, diet was not measured in this study, and it is unclear how diet may have affected outcomes. It is also unlikely that we reached theme saturation in the process evaluation because we only interviewed a subset of participants. All of these factors limit interpretation and generalizability of results and should be addressed when conducting a larger confirmatory trial.

Conclusion

A culturally-tailored multicomponent exercise intervention was an effective model for engaging South Asian mothers in structured physical activity. The results of this study will be used to refine the intervention and to plan a future trial to evaluate efficacy and to determine which intervention components are the most effective for increasing and sustaining physical activity among South Asian women.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the National Institutes of Health R56DK099680. We thank Ruchi Gupta, MD and Ashley Dyer for input on the exercise classes for the children, and David Conroy, PhD for input on measurement. We thank our exercise instructors, Adenia Linker, Manjari Patil, Carolina Escrich, Roberto Luna, Muhammed Javed and Dante Peña. We would like to acknowledge Meraj Baig, Madhuri Pydisetty, Ankita Puri and Vrati Parikh for assistance with data collection. Results of the present study do not constitute endorsement by the American College of Sports Medicine.

Footnotes

Disclosures The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose

References

- 1.Ainsworth BE, Irwin ML, Addy CL, Whitt MC, Stolarczyk LM. Moderate physical activity patterns of minority women: the Cross-Cultural Activity Participation Study. Journal of women's health & gender-based medicine. 1999;8(6):805–13. doi: 10.1089/152460999319129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Diabetes Association 2. Classification and diagnosis of diabetes. Diabetes care. 2015;38(Supplement 1):S8–S16. doi: 10.2337/dc15-S005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Araneta MR, Kanaya AM, Hsu WC, Chang HK, Grandinetti A, Boyko EJ, et al. Optimum BMI cut points to screen asian americans for type 2 diabetes. Diabetes care. 2015;38(5):814–20. doi: 10.2337/dc14-2071. doi: 10.2337/dc14-2071. PubMed PMID: 25665815; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC4407753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Artinian NT, Fletcher GF, Mozaffarian D, Kris-Etherton P, Van Horn L, Lichtenstein AH, et al. Interventions to promote physical activity and dietary lifestyle changes for cardiovascular risk factor reduction in adults: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2010;122(4):406–41. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3181e8edf1. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3181e8edf1. PubMed PMID: 20625115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.A Community of Contrasts: Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders in the United States 2012. Asian American Justice Center and Asian Pacific American Legal Center. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown T, Smith S, Bhopal R, Kasim A, Summerbell C. Diet and physical activity interventions to prevent or treat obesity in South Asian children and adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. International journal of environmental research and public health. 2015;12(1):566–94. doi: 10.3390/ijerph120100566. doi: 10.3390/ijerph120100566. PubMed PMID: 25584423; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC4306880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cashman SB, Adeky S, Allen AJ, 3rd, Corburn J, Israel BA, Montano J, et al. The power and the promise: working with communities to analyze data, interpret findings, and get to outcomes. American journal of public health. 2008;98(8):1407–17. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.113571. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.113571. PubMed PMID: 18556617; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC2446454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cross-Bardell L, George T, Bhoday M, Tuomainen H, Qureshi N, Kai J. Perspectives on enhancing physical activity and diet for health promotion among at-risk urban UK South Asian communities: a qualitative study. BMJ open. 2015;5(2):e007317. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-007317. Epub 2015/03/01. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-007317. PubMed PMID: 25724983; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPmc4346672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Daniel M, Wilbur J, Fogg LF, Miller AM. Correlates of lifestyle: physical activity among South Asian Indian immigrants. Journal of community health nursing. 2013;30(4):185–200. doi: 10.1080/07370016.2013.838482. Epub 2013/11/14. doi: 10.1080/07370016.2013.838482. PubMed PMID: 24219639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Das P, Horton R. Rethinking our approach to physical activity. Lancet. 2012;380(9838):189–90. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61024-1. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61024-1. PubMed PMID: 22818931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dave SS, Craft LL, Mehta P, Naval S, Kumar S, Kandula NR. Life Stage Influences on U.S. South Asian Women's Physical Activity. American journal of health promotion : AJHP. 2014 doi: 10.4278/ajhp.130415-QUAL-175. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.130415-QUAL-175. PubMed PMID: 24717067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dave SS, Craft LL, Mehta P, Naval S, Kumar S, Kandula NR. Life stage influences on U.S. South Asian women's physical activity. American journal of health promotion : AJHP. 2015;29(3):e100–8. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.130415-QUAL-175. Epub 2014/04/11. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.130415-QUAL-175. PubMed PMID: 24717067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gillett PA, White AT, Caserta MS. Effect of exercise and/or fitness education on fitness in older, sedentary, obese women. Journal of aging and physical activity. 1996;4(1):42–55. PubMed PMID: WOS:A1996TN39100004. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hussain-Gambles M, Leese B, Atkin K, Brown J, Mason S, Tovey P. Involving South Asian patients in clinical trials. Health Technol Assess. 2004;8(42):iii, 1–109. doi: 10.3310/hta8420. Epub 2004/10/19. doi: 98-23-19 [pii]. PubMed PMID: 15488164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kanaya AM, Herrington D, Vittinghoff E, Ewing SK, Liu K, Blaha MJ, et al. Understanding the high prevalence of diabetes in U.S. south Asians compared with four racial/ethnic groups: the MASALA and MESA studies. Diabetes care. 2014;37(6):1621–8. doi: 10.2337/dc13-2656. doi: 10.2337/dc13-2656. PubMed PMID: 24705613; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC4030091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kandula NR, Patel Y, Dave S, Seguil P, Kumar S, Baker DW, et al. The South Asian Heart Lifestyle Intervention (SAHELI) study to improve cardiovascular risk factors in a community setting: design and methods. Contemporary clinical trials. 2013;36(2):479–87. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2013.09.007. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2013.09.007. PubMed PMID: 24060673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klein S, Allison DB, Heymsfield SB, Kelley DE, Leibel RL, Nonas C, et al. Waist circumference and cardiometabolic risk: a consensus statement from Shaping America's Health: Association for Weight Management and Obesity Prevention; NAASO, The Obesity Society; the American Society for Nutrition; and the American Diabetes Association. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;85(5):1197–202. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/85.5.1197. Epub 2007/05/11. doi: 85/5/1197 [pii]. PubMed PMID: 17490953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kriska AM, Edelstein SL, Hamman RF, Otto A, Bray GA, Mayer-Davis EJ, et al. Physical activity in individuals at risk for diabetes: Diabetes Prevention Program. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2006;38(5):826–32. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000218138.91812.f9. Epub 2006/05/05. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000218138.91812.f9 00005768-200605000-00004 [pii]. PubMed PMID: 16672833; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC1570396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Little RR, Rohlfing CL, Sacks DB. Status of hemoglobin A1c measurement and goals for improvement: from chaos to order for improving diabetes care. Clinical chemistry. 2011;57(2):205–14. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2010.148841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marcus BH, Rakowski W, Rossi JS. Assessing motivational readiness and decision making for exercise. Health Psychol. 1992;11(4):257–61. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.11.4.257. Epub 1992/01/01. PubMed PMID: 1396494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Misra A, Alappan NK, Vikram NK, Goel K, Gupta N, Mittal K, et al. Effect of supervised progressive resistance-exercise training protocol on insulin sensitivity, glycemia, lipids, and body composition in Asian Indians with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes care. 2008;31(7):1282–7. doi: 10.2337/dc07-2316. Epub 2008/03/05. doi: dc07-2316 [pii] 10.2337/dc07-2316. PubMed PMID: 18316394; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC2453659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Natesan A, Nimbal VC, Ivey SL, Wang EJ, Madsen KA, Palaniappan LP. Engaging South Asian women with type 2 diabetes in a culturally relevant exercise intervention: a randomized controlled trial. BMJ open diabetes research & care. 2015;3(1):e000126. doi: 10.1136/bmjdrc-2015-000126. doi: 10.1136/bmjdrc-2015-000126. PubMed PMID: 26566446; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC4636542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oza-Frank R, Ali MK, Vaccarino V, Narayan KM. Asian Americans: diabetes prevalence across U.S. and World Health Organization weight classifications. Diabetes care. 2009;32(9):1644–6. doi: 10.2337/dc09-0573. Epub 2009/06/11. doi: 10.2337/dc09-0573 dc09-0573 [pii]. PubMed PMID: 19509010; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC2732150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pickering TG, Hall JE, Appel LJ, Falkner BE, Graves JW, Hill MN, et al. Recommendations for blood pressure measurement in humans: an AHA scientific statement from the Council on High Blood Pressure Research Professional and Public Education Subcommittee. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2005;7(2):102–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-6175.2005.04377.x. Epub 2005/02/22. PubMed PMID: 15722655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rangaswamy P, Kalayil AL. South Asian American Policy and Research Institute (SAAPRI) 2005. Making Data Count: South Asian Americans in the 2000 Census with Focus on Illinois. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Resnick B, Ory MG, Hora K, Rogers ME, Page P, Bolin JN, et al. A proposal for a new screening paradigm and tool called Exercise Assessment and Screening for You (EASY) Journal of aging and physical activity. 2008;16(2):215–33. doi: 10.1123/japa.16.2.215. PubMed PMID: 18483443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rooney LK, Bhopal R, Halani L, Levy ML, Partridge MR, Netuveli G, et al. Promoting recruitment of minority ethnic groups into research: qualitative study exploring the views of South Asian people with asthma. Journal of public health. 2011;33(4):604–15. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdq100. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdq100. PubMed PMID: 21228023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sallis J, Pinski RB, Grossman RM, et al. The development of self-efficacy scales for healthrelated diet and exercise behaviors. Health Education Research. 1988;(3):283–92. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Samsudeen BS, Douglas A, Bhopal RS. Challenges in recruiting South Asians into prevention trials: health professional and community recruiters' perceptions on the PODOSA trial. Public health. 2011;125(4):201–9. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2011.01.013. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2011.01.013. PubMed PMID: 21450322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.South Asian Americans Leading Together. A Demographic Snapshot of South Asians in the United States 2012. Available from: http://saalt.org/resources/reports-and-publications/#factsheets.

- 31. [Accessed on June 2, 2015]; [Accessed on June 2 2014];South Asian Americans Leading Together. A Demographic Snapshot of South Asians in the United States. http://saalt.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/Demographic-Snapshot-Asian-American-Foundation-2012.pdf. http://saalt.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/Demographic-Snapshot-Asian-American-Foundation-2012.pdf. Available from: http://saalt.org/resources/reports-and-publications/#factsheets.

- 32.Tirodkar MA, Baker DW, Makoul GT, Khurana N, Paracha MW, Kandula NR. Explanatory models of health and disease among South Asian immigrants in Chicago. Journal of immigrant and minority health / Center for Minority Public Health. 2011;13(2):385–94. doi: 10.1007/s10903-009-9304-1. Epub 2010/02/05. doi: 10.1007/s10903-009-9304-1. PubMed PMID: 20131000; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC2905487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vahabi M, Damba C. A feasibility study of a culturally and gender-specific dance to promote physical activity for South Asian immigrant women in the greater Toronto area. Women's health issues : official publication of the Jacobs Institute of Women's Health. 2015;25(1):79–87. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2014.09.007. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2014.09.007. PubMed PMID: 25491397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vlaar EM, van Valkengoed IG, Nierkens V, Nicolaou M, Middelkoop BJ, Stronks K. Feasibility and effectiveness of a targeted diabetes prevention program for 18 to 60-year-old South Asian migrants: design and methods of the DH!AAN study. BMC public health. 2012;12:371. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-371. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-371. PubMed PMID: 22621376; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3504520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wing RR, Hamman RF, Bray GA, Delahanty L, Edelstein SL, Hill JO, et al. Achieving weight and activity goals among diabetes prevention program lifestyle participants. Obes Res. 2004;12(9):1426–34. doi: 10.1038/oby.2004.179. Epub 2004/10/16. doi: 12/9/1426 [pii] 10.1038/oby.2004.179. PubMed PMID: 15483207; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC2505058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ye J, Rust G, Baltrus P, Daniels E. Ann Epidemiol. 2009. Cardiovascular Risk Factors among Asian Americans: Results from a National Health Survey. Epub 2009/06/30. doi: S1047-2797(09)00117-3 [pii] 10.1016/j.annepidem.2009.03.022. PubMed PMID: 19560369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]