Survival after sorafenib initiation in newly diagnosed Medicare beneficiaries with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is exceptionally short, suggesting that trial results are not generalizable to all HCC patients. The downsides of sorafenib use—high drug-related symptom burden and high drug cost—must be considered in light of this minimal benefit.

Keywords: Carcinoma, hepatocellular; Liver neoplasms; Sorafenib; Drug costs; Medicare; Liver diseases; Aged

Abstract

Background.

Phase III trials show sorafenib improves survival in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Because of narrow trial eligibility, results may not be generalizable to a broader HCC population. We sought to evaluate the effectiveness of initial sorafenib versus no treatment among Medicare beneficiaries with advanced HCC.

Materials and Methods.

Patients with advanced HCC diagnosed from 2008 to 2011 were identified from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results–Medicare database. Eligible patients received initial sorafenib or no therapy and were covered by Medicare parts A, B, and D. Sorafenib use and outcomes were described in this population. Using a propensity score (PS)-matched sample, we compared the effectiveness of sorafenib versus no treatment by Cox proportional hazards and binomial regression, using a landmark requiring all patients to survive ≥60 days after diagnosis.

Results.

Of 1,532 patients, 27% received initial sorafenib. Median duration of sorafenib use was 60 days (interquartile range [IQR], 30–107 days), and median survival from first prescription was 3 months (IQR, 1–8 months). In the PS-matched cohort, median survival was 3 months from the 60-day landmark in sorafenib-treated (n = 223) and 2 months in untreated (n = 223) patients (adjusted hazard ratio, 0.95 [95% confidence interval (CI), 0.78–1.16]). Sorafenib was associated with a nonsignificant reduction in mortality at 3 months (44% versus 51%; adjusted risk ratio, 0.88 [95% CI, 0.72–1.07]), but no reduction thereafter.

Conclusion.

Survival after sorafenib initiation in newly diagnosed Medicare beneficiaries with HCC is exceptionally short, suggesting trial results are not generalizable to all HCC patients. The downsides of sorafenib use—high drug-related symptom burden and high drug cost—must be considered in light of this minimal benefit.

Implications for Practice:

The findings of a median survival of only 3 months in Medicare beneficiaries with HCC prescribed sorafenib as first-line therapy highlight the questionable value of sorafenib in this population. Patients should be cautioned that outside of the narrow confines of randomized trials, their life expectancy may be very short, and any benefit of sorafenib is likely to be quite small. Given that sorafenib causes considerable adverse effects and offers no symptom palliation, supportive care should be discussed as a reasonable alternative to sorafenib, particularly for patients who have a poor performance status or advanced cirrhosis.

Abstract

摘要

背景. III 期临床试验显示索拉非尼改善了晚期肝细胞癌 (HCC) 患者的生存。但由于临床试验的入选标准十分狭窄, 难以适用于较广泛的 HCC 人群。我们试图在享有医保的晚期 HCC 患者中, 对初始索拉非尼治疗和不治疗的效果进行评价。

材料与方法. 从监测、流行病学和最终结果 (SEER) -医保数据库中, 识别出 2008 年至 2011 年间诊断为晚期 HCC 的患者。符合条件的患者接受初始索拉非尼治疗或不治疗均为医保 A、B 和 D 部分所覆盖。对该人群中索拉非尼的使用和转归进行描述。我们在倾向性评分 (PS) 匹配样本中, 使用所有患者诊断后生存 ≥60天作为界标, 用 Cox 比例风险和二项回归分析对索拉非尼治疗与不治疗的效果进行比较。

结果. 1 532 例患者中 27%接受了初始索拉非尼治疗。索拉非尼中位治疗时间为 60 天[四分位间距 (IQR): 30∼107天], 首次处方后的中位生存时间为 3 个月 (IQR: 1∼8个月)。在 PS 匹配队列中, 索拉非尼治疗组 (n=223) 在 60 天界标后的中位生存时间为 3 个月, 而不治疗组 (n=223) 为 2 个月[校正后风险比: 0.95, 95%置信区间 (CI): 0.78∼1.16]。索拉非尼组 3 个月死亡率低于不治疗组, 但差异无统计学意义 (44% vs. 51%, 校正后危险度: 0.88, 95%CI: 0.72∼1.07), 且之后未出现进一步下降。

结论. 享有医保的新诊断HCC患者接受初始索拉非尼治疗后的生存获益异常的短, 提示临床试验结果并不适用于所有HCC患者。考虑到索拉非尼的获益非常有限, 同时药物相关性症状负担较高, 药物花费也高, 应减少索拉非尼的使用。The Oncologist 2016;21:1113–1120

对临床实践的提示: 在享有医保的 HCC 患者中, 处方索拉非尼进行一线治疗的中位生存时间仅为 3 个月, 这对索拉非尼在这一人群中的价值提出了质疑。对于不符合随机临床试验中的狭窄限制条件的患者, 应提醒他们预期生存时间可能会非常短, 从索拉非尼治疗中得到的获益也可能相当之小。鉴于索拉非尼可引起相当多的不良事件, 而且并不能缓解症状, 应考虑将支持治疗作为合理的替代疗法, 尤其是对于体能状态不佳或合并晚期肝硬化的患者。

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the second most common cause of cancer-related death worldwide [1]. Although less common in more developed nations, in 2015 liver cancer is anticipated to be the fifth leading cause of U.S. cancer death in men and the ninth leading cause in women [2]. With an increasing incidence rate, HCC will continue to be a major global health problem for the foreseeable future [3]. HCC arises almost exclusively in the background of cirrhosis, the extent of which directly influences the safety of treatment options and plays a major role in determining the prognosis of HCC [4]. Unfortunately, most patients with HCC present with extensive disease not amenable to curative-intent resection or transplantation; for these patients prognosis is uniformly poor.

Sorafenib, a multitargeted kinase inhibitor, is the only drug that has demonstrated a survival benefit over supportive care in advanced HCC. In the pivotal Sorafenib Hepatocellular Carcinoma Assessment Randomized Protocol (SHARP) trial, sorafenib-treated patients had a median time to progression of 5.5 months and survival of 10.7 months, a 2.8-month absolute improvement in survival over placebo [5]. This survival benefit was corroborated in the Asia-Pacific trial, the second placebo-controlled randomized trial [6]. However, participants in both trials had good performance status and early, compensated cirrhosis. Given that the extent of cirrhosis and performance status are critical features of HCC prognosis [4], the external validity of the SHARP and Asia-Pacific trial results might be limited.

To assess outcomes of sorafenib in a broader population, the international Global Investigation of therapeutic DEcisions in hepatocellular carcinoma and Of its treatment with sorafeNib (GIDEON) registry enrolled patients initiating sorafenib as part of routine care; its preliminary results suggest patients treated with sorafenib who have compensated, Child-Pugh (CP) class A (CPA) cirrhosis have outcomes similar to those of patients in the SHARP trial, whereas survival for patients with CP class B (CPB) and CP class C (CPC) cirrhosis is poor, 4.8 and 2 months, respectively [7, 8]. Because the GIDEON registry does not include a comparator arm, whether sorafenib-treated patients did receive some benefit from the drug despite the short survival duration is unknown. Thus, we sought to evaluate the effectiveness of initial sorafenib for advanced HCC in a population-based cohort of Medicare beneficiaries in the U.S.

Methods

The Office of Human Research Ethics at the University of North Carolina deemed this analysis exempt from review (#12-1828).

Study Population

The cohort was derived from the Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER)–Medicare linkage. SEER collects data on incident cancers from population-based registries covering 28% of the U.S. population. Linkage of SEER cases to Medicare claims allows investigation of cancer treatment and outcomes [9, 10]. The details of cohort selection are described in the supplemental online Appendix. In brief, we included patients diagnosed with HCC between 2008 and 2011. Because sorafenib is indicated for advanced HCC, we restricted our analysis to patients with multifocal tumors or extrahepatic spread. Patients with preceding invasive cancer within the past 5 years were excluded to avoid misclassification of liver metastases. To ensure availability of complete claims for analysis, we included only patients with continuous enrollment in Medicare parts A, B, and D and patients not enrolled in Medicare managed care plans in the 6 months before and after diagnosis or until death.

Covariates

Patient demographic characteristics and socioeconomic indicators were derived from SEER. The liver collaborative stage extension variables, which are reported to SEER by the cancer registrars program, were used to determine cancer extent, including maximum tumor size, tumor multiplicity, and presence or absence of invasion into major portal and/or hepatic vein branches. Diagnosis codes for underlying cause of liver disease and complications of cirrhosis were used to control for confounding liver disease [11]. HCC screening behavior was ascertained by prediagnosis α-fetoprotein (AFP) [12, 13] because screening is associated with decreased probability of frailty in older adults [14]. Noncirrhotic comorbidity was determined by using the Klabunde modification of the Charlson Comorbidity Index [15], omitting codes for liver disease.

Treatment

Sorafenib use was determined from national drug codes in Part D files. Because only 200-mg sorafenib pills are available, we were able to estimate the starting dose of drug by dividing the number of pills supplied by the prescription’s recorded days supply. Duration of sorafenib use was defined as the number of days between the date of the initial prescription and the date of the final prescription plus the days supply.

Statistical Analysis

Multivariable logistic regression was used to evaluate factors associated with sorafenib receipt. We conducted two survival analyses: (a) a descriptive analysis of survival from time of initial sorafenib prescription to death in all patients taking sorafenib as first-line therapy using Kaplan-Meier methods and (b) a comparative survival analysis between treated and untreated patients restricted to patients who survived at least 60 days from diagnosis (the landmark). In this restricted group, patients who initiated sorafenib within 60 days of diagnosis were categorized as sorafenib users and those who did not initiate before this landmark were categorized as nonusers. These restrictions were made to avoid immortal time bias, whereby patients dying during the exposure window (e.g., within the first 60 days after diagnosis) have a lower chance of receiving treatment (and higher chance of being classified as untreated), thereby artificially increasing the risk for the outcome in the untreated group [16].

In this restricted cohort, we used propensity score (PS) matching to evaluate the treatment effect among patients balanced on key confounders (supplemental online Appendix; supplemental online Tables 1, 2) [17–21]. Survival by treatment group was compared using Cox proportional hazards models, and mortality rates at 3, 6, and 12 months from the 60-day landmark were then compared by using risk ratios by binomial regression. To explore the possibility of heterogeneous treatment effect, we calculated risk ratios by strata of key covariates. To ensure patient confidentiality, all cells containing fewer than 11 patients are suppressed. Analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS, Cary, NC, http://www.sas.com).

Sensitivity Analyses

In the descriptive survival analysis, we explored survival among sorafenib-treated patients after requiring patients to fill two or more prescriptions. Because patients receiving sorafenib as first-line therapy might be expected to be frailer, with more extensive cancer than those who received sorafenib after prior locoregional therapy, we also described survival from the initial sorafenib prescription of patients who otherwise met cohort eligibility but received a different first-line therapy. In the comparative analysis, we examined the robustness of our results by changing the 60-day landmark to 30 and 90 days.

Results

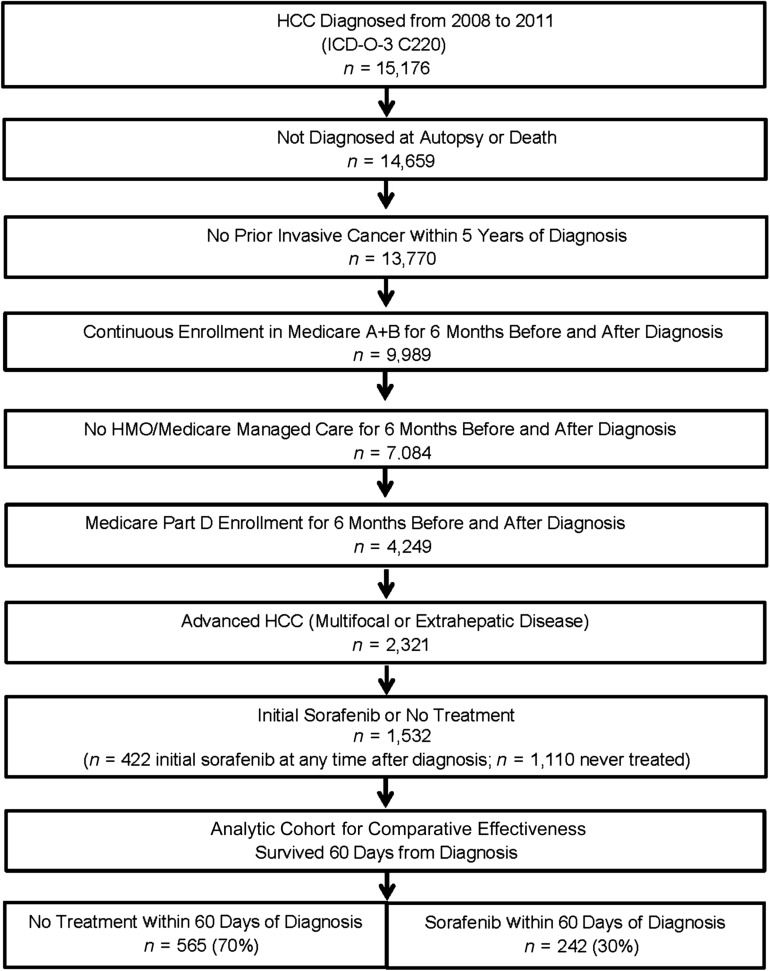

A total of 1,532 patients met cohort eligibility criteria (Fig. 1). Of these, 422 (27%) were treated with initial sorafenib after diagnosis: 314 (74%) initiated drug within 60 days, 56 (13%) between days 61 and 90, and 52 (12%) after 90 days. Of patients initiating before 60 days, 242 survived to that landmark and make up the sorafenib group in the effectiveness comparison. The untreated group includes 565 who survived 60 days from diagnosis and did not receive sorafenib before this landmark (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials diagram of cohort assembly.

Abbreviations: HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; HMO, health maintenance organization; ICD-O-3, International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, 3rd edition.

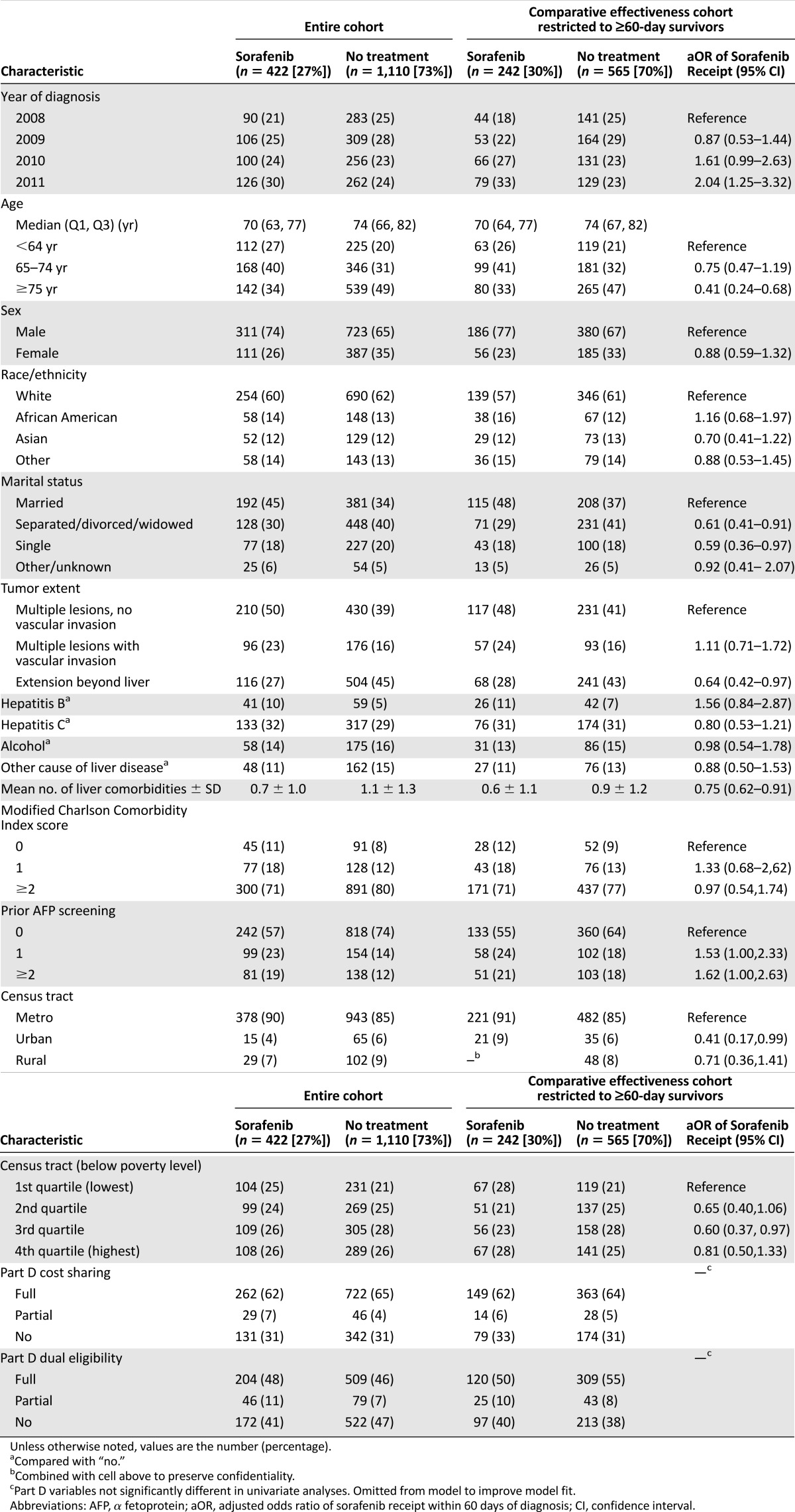

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma and factors associated with sorafenib receipt

Patterns of Sorafenib Use

The use of initial sorafenib increased during the time period under study, which began the first full year after U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval for HCC. In the restricted effectiveness cohort before PS matching (n = 242), this increase went from 24% of patients diagnosed in 2008 to 38% of patients diagnosed in 2011 (odds ratio, 2.04 [95% confidence interval (CI), 1.25–3.32]) (Table 1). Compared with patients who received no treatment for their HCC, patients receiving first-line sorafenib were younger, more likely to be married, and more likely to be from a metropolitan area. There was no evidence for differing sorafenib use by enrollment in the Part D cost-sharing program or with dual Medicaid eligibility.

Among all patients treated with sorafenib as initial therapy (n = 422), 141 (33%) saw both a gastroenterologist and a hematologist/oncologist between diagnosis and start of sorafenib treatment, 135 (32%) saw a hematologist/oncologist only, 58 (14%) saw a gastroenterologist only, and 88 (21%) did not have a record for a visit with either subspecialist during that time. Most patients, 322 (76%), received an initial prescription for 4 pills per day, corresponding to the FDA-approved dose of 400 mg b.i.d. Seventy-eight (18%) began at a half-dose of 2 pills per day. The median duration of sorafenib use was 60 days (interquartile range [IQR], 30–107 days). Because patients may be instructed by their physicians to take lower doses than is reflected by the prescribing information, this may underestimate the duration of sorafenib use. In the effectiveness cohort according to the 60-day landmark, median duration of sorafenib use was 74 days (IQR, 30–132 days). In both matched and unmatched cohorts, 29% of patients filled only one prescription.

Survival After Sorafenib Initiation

Among all 422 patients who received initial sorafenib, the median survival from the time of the initial prescription fill date was 3 months (IQR, 1–8 months). In sensitivity analysis restricted to patients who filled ≥2 prescriptions and are more likely to have been exposed to the drug (n = 234), survival from the initial prescription was 5 months (IQR, 2–12 months).

Patients who received sorafenib as a subsequent therapy (n = 232) had a better prognosis at the time of diagnosis than patients receiving initial sorafenib, with less advanced cancer and greater likelihood of prediagnosis AFP screening. In this group with better prognosis, median survival from first sorafenib prescription fill date was 9 months (IQR, 3–17 months).

Comparative Effectiveness of Sorafenib

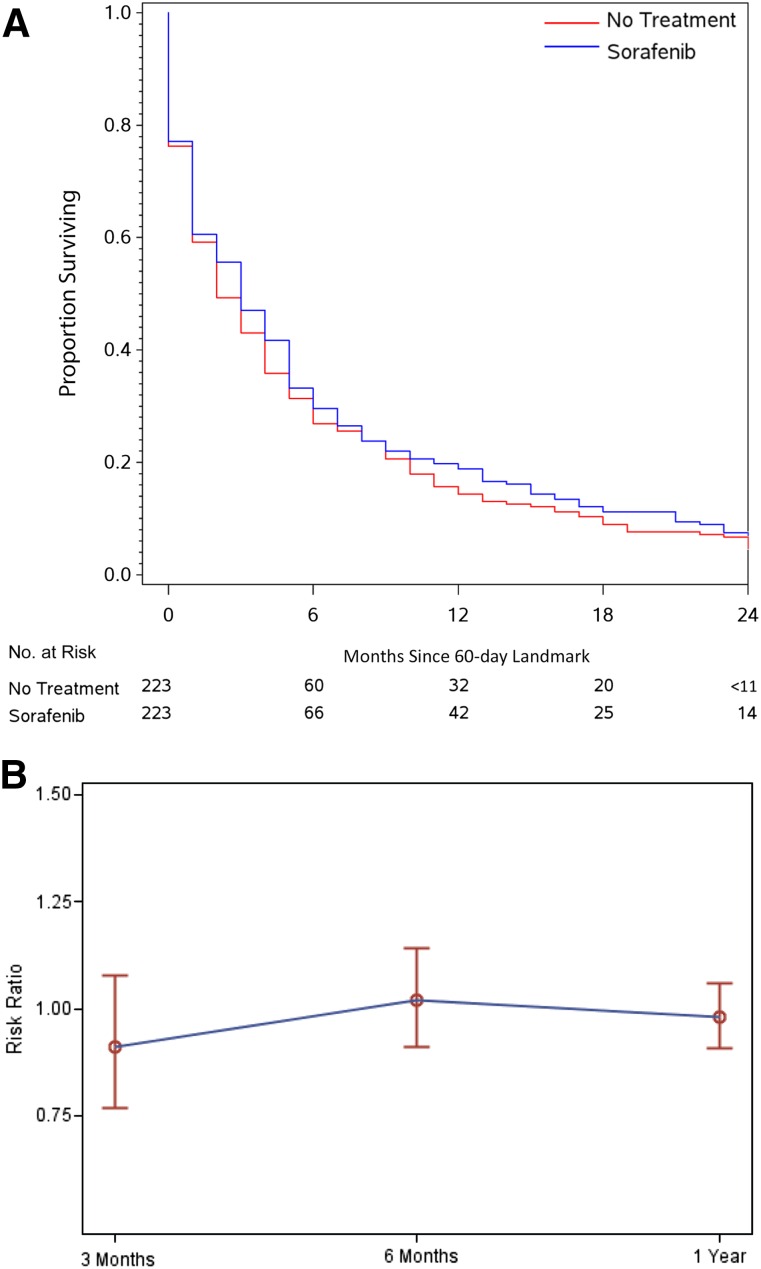

In the PS-matched effectiveness cohort, median survival from the 60-day landmark was 3 months for sorafenib-treated patients (IQR, 1–8 months) and 2 months for untreated patients (IQR, 1–8 months) patients (adjusted hazard ratio, 0.95 [95% CI, 0.78–1.16]) (Fig. 2A). Of note, because all sorafenib patients began therapy before the landmark, this median survival is not directly comparable to survival from the first prescription described for the entire initial sorafenib cohort (median survival from the initial prescription in this restricted sorafenib group was 4 months [IQR, 2–9 months]). By 3 months from the 60-day landmark, 51% of untreated patients and 44% of sorafenib patients had died (adjusted risk ratio [aRR], 0.88 [95% CI, 0.72–1.07]). No trend toward sorafenib benefit was apparent at 6 months (aRR, 0.97 [95% CI, 0.86–1.11]) or 12 months (aRR, 0.95 [95% CI, 0.87–1.04]) (Figure 2B, Table 2). In sensitivity analyses, varying the landmark between 30 and 90 days and changing the survival anchor from 60-day landmark to the date of diagnosis had no substantive effect on the findings (supplemental online Tables 3, 4).

Figure 2.

Effectiveness of initial sorafenib compared with no treatment. (A): Kaplan-Meier survival estimates from 60-day landmark of propensity score-matched patients. (B): Risk ratio for mortality shown with 95% confidence intervals at 3, 6, and 12 months from the 60-day landmark.

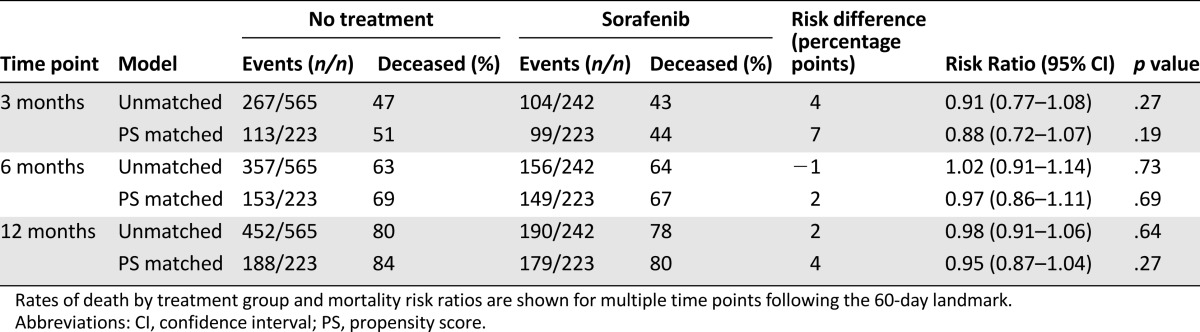

Table 2.

Effect of sorafenib compared with no treatment on the risk for death

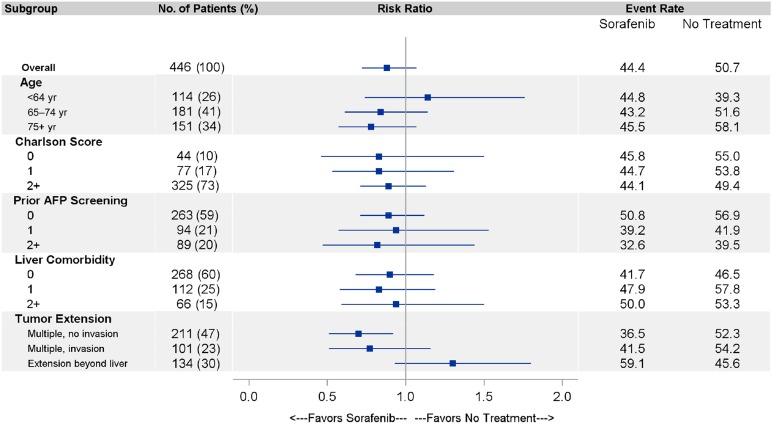

In an exploratory subgroup analysis limited by small sample size, the effectiveness of initial sorafenib appeared greatest in patients with the lowest burden of disease (multiple tumors without vascular invasion or extrahepatic spread; 3-month aRR, 0.70 [95% CI, 0.51–0.95]); it was least pronounced in patients age <65 years (e.g., disabled beneficiaries), and patients with more liver comorbidity (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Effectiveness of sorafenib in clinically relevant subgroups. The risk ratios for mortality shown with 95% confidence intervals at 3 months from the 60-day landmark (the time of maximal sorafenib benefit) are shown for the strata of age, Charlson Comorbidity Index, number of liver comorbidities, receipt of prior AFP screening, and tumor extent in the propensity score-matched cohort.

Abbreviation: AFP, α-fetoprotein.

Discussion

In this cohort of disabled and elderly Medicare beneficiaries, the use of sorafenib as initial therapy for advanced HCC resulted in a median survival of only 3 months, well below the 10.7-month benchmark set by the SHARP trial. Even with restriction to patients filling more than one prescription, which biases the analysis toward sorafenib benefit by excluding patients dying during that first month of therapy, the median survival was only 5 months. We further found that the survival of sorafenib-treated patients was not significantly better than that of patients not undergoing HCC treatment.

Although the median survival of sorafenib-treated patients was exceptionally short, this short duration is concordant with previously reported outcomes of patients with advanced HCC treated outside clinical trials [8, 22]. The limitations of the SEER-Medicare dataset preclude a formal assessment of survival by CP, performance status, or Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer stage, yet it is likely that the short survival in this population-based sample can be explained by having more advanced liver disease on average than patients treated in clinical trials. Notably, GIDEON registry participants with CPB and CPC cirrhosis lived only 4.8 and 2 months, respectively, whereas patients who participated in the SHARP trial or the CPA patients enrolled in GIDEON lived for 10.7 and 10.3 months, respectively [5, 8].

The inferior survival among these Medicare beneficiaries treated with initial sorafenib is also likely attributable to a higher cancer burden within our population than in SHARP or GIDEON. To estimate the effectiveness of sorafenib versus no therapy, we could include only patients for whom there is a reasonable no-treatment control group: patients with newly diagnosed disease. These patients treated with first-line sorafenib had more advanced disease at diagnosis than patients receiving other first-line treatment. Indeed, among patients with treated with sorafenib after other first-line therapy (65% transcatheter arterial chemoembolization, 19% surgery or ablation), the observed median survival of 9 months is more concordant with that of CPA patients in GIDEON and SHARP. The exploratory subgroup analysis also suggested that those with earlier-stage disease (e.g., without vascular invasion or extrahepatic metastases) were more likely to benefit. We believe that, taken together, the lack of survival benefit afforded to a population of newly diagnosed HCC patients with very advanced disease and the suggestion of benefit in those with better prognosis reinforce that sorafenib does benefit appropriately selected Medicare patients and that its use should be restricted to patients whose clinical characteristics better match those of patients in whom sorafenib has demonstrated benefit.

There are several key limitations of our estimate of sorafenib’s effectiveness based on the observational study design, the most crucial of which is that unmeasured confounding may be influencing the treatment effect estimate. In the case of HCC, the extent of cirrhosis and performance status are such important prognostic factors that they are included in the most widely applied staging system [4]. Frailty is also of major concern as a possible unmeasured confounder in this study in older cancer patients. However, as we would anticipate patients with more advanced liver disease and frailty would be less likely to receive sorafenib and to be more likely to experience early death, we would anticipate that much of the unmeasured confounding would have biased the results in favor of better outcomes in the sorafenib group. The data source also limits the generalizability of our estimate of sorafenib effectiveness. Although we did include patients eligible for Medicare on the basis of disability (22% of the cohort was age <65 years), our results may not be generalizable to a younger, privately insured population.

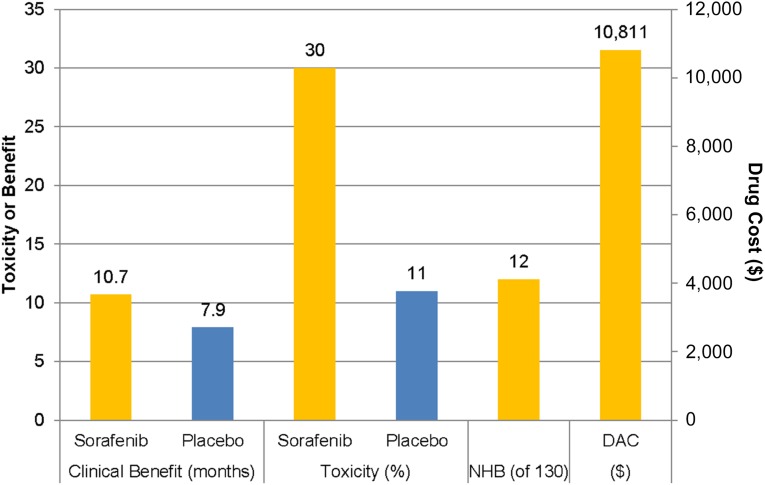

Yet, even if our results do not apply to all newly diagnosed patients with HCC, they demonstrate that the results of the SHARP and Asia-Pacific trials do not describe the experience of sorafenib in all patients with advanced HCC. The recently published American Society of Clinical Oncology Value Framework recommends evaluating the clinical benefit (a composite of clinical efficacy and toxicity) against the drug acquisition cost and patient copay [23]. When this exercise is performed with the data from the SHARP trial (Fig. 4), the net health benefit of sorafenib is only 12 of 130 possible points (32 for a 35% improvement in survival, −20 for a substantially less well-tolerated drug, 0 bonus points). The Value Framework recommends displaying these 12 net health benefit points alongside the drug acquisition cost, which was on average $10,811 for a 30-day supply across Medicare part D plans in 2014 [24]. So although these Value Framework worksheets are intended to be subject to individual interpretation regarding the value of even small net health benefit scores, it is clear that even in the best-case scenario some patients might reasonably question the value of sorafenib.

Figure 4.

Clinical benefit, toxicity, NHB, and DAC of sorafenib using the American Society of Clinical Oncology Value Framework [24]. The data for each parameter are shown above the bar. Clinical outcomes are taken from the Sorafenib Hepatocellular Carcinoma Assessment Randomized Protocol trial [5]. Drug costs are the average cost for Medicare part D plans in 2014.

Abbreviations: DAC, drug acquisition cost; NHB, net health benefit.

Conclusion

The lack of treatment alternatives and oral mode of administration may make it more attractive to prescribe sorafenib outside the narrow clinical characteristics in which it does in fact offer survival benefit, yet less fit patients and those with more advanced liver disease should be cautioned that sorafenib likely affords them no net health benefit.

See http://www.TheOncologist.com for supplemental material available online.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study used the linked Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER)-Medicare database. The interpretation and reporting of these data are the sole responsibility of the authors. The authors acknowledge the efforts of the Applied Research Program, National Cancer Institute; the Office of Research, Development and Information, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; Information Management Services, Inc.; and the SEER Program tumor registries in the creation of the SEER-Medicare database. This work was supported by National Cancer Institute, K07CA160722 (H.K.S.); National Institutes of Health Building Interdisciplinary Research Careers in Women’s Health (BIRCWH) K12 Program (S.B.D.); North Carolina Translational and Clinical Sciences Institute (UL1TR001111) (S.B.D.). Additional support was provided by the Integrated Cancer Information and Surveillance System, UNC Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center, with funding provided by the University Cancer Research Fund via the state of North Carolina.

Author Contributions

Conception/Design: Hanna K. Sanoff, YunKyung Chang, Jennifer L. Lund, Bert H. O’Neil, Stacie B. Dusetzina

Provision of study material or patients: Hanna K. Sanoff

Collection and/or assembly of data: Hanna K. Sanoff, YunKyung Chang

Data analysis and interpretation: Hanna K. Sanoff, YunKyung Chang, Jennifer L. Lund, Bert H. O’Neil, Stacie B. Dusetzina

Manuscript writing: Hanna K. Sanoff, YunKyung Chang, Jennifer L. Lund, Bert H. O’Neil, Stacie B. Dusetzina

Final approval of manuscript: Hanna K. Sanoff, YunKyung Chang, Jennifer L. Lund, Bert H. O’Neil, Stacie B. Dusetzina

Other (financial and adminstrative): Hanna K. Sanoff

Disclosures

Hanna K. Sanoff: Amgen (C/A), Bayer, Novartis (RF); Bert H. O’Neil: Bayer (C/A). The other authors indicated no financial relationships.

(C/A) Consulting/advisory relationship; (RF) Research funding; (E) Employment; (ET) Expert testimony; (H) Honoraria received; (OI) Ownership interests; (IP) Intellectual property rights/inventor/patent holder; (SAB) Scientific advisory board

References

- 1.Stewart BW, Wild C. eds. World cancer report 2014. International Agency for Research on Cancer . Geneva, Switzerland: WHO Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2015. Available at http://www.cancer.org/research/cancerfactsstatistics/cancerfactsfigures2015/index. Accessed July 20, 2015.

- 3.El-Serag HB. Hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1118–1127. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1001683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Llovet JM, Brú C, Bruix J. Prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma: The BCLC staging classification. Semin Liver Dis. 1999;19:329–338. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1007122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Llovet JM, Ricci S, Mazzaferro V, et al. Sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:378–390. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0708857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheng AL, Kang YK, Chen Z, et al. Efficacy and safety of sorafenib in patients in the Asia-Pacific region with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: A phase III randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:25–34. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70285-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lencioni R, Kudo M, Ye SL, et al. GIDEON (Global Investigation of therapeutic DEcisions in hepatocellular carcinoma and Of its treatment with sorafeNib): Second interim analysis. Int J Clin Pract. 2014;68:609–617. doi: 10.1111/ijcp.12352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marrero JA, Lencioni R, Kudo M, et al. Global investigation of therapeutic decisions in hepatocellular carcinoma and of its treatment with sorafenib second interim analysis in more than 1,500 patients: Clinical findings in patients with liver dysfunction. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:4001a. [Google Scholar]

- 9.SEER-Medicare linked database. Applied research, cancer control and population sciences. National Cancer Institute. 2014. Available at http://appliedresearch.cancer.gov/seermedicare/. Accessed April 9, 2014.

- 10.Warren JL, Klabunde CN, Schrag D, et al. Overview of the SEER-Medicare data: Content, research applications, and generalizability to the United States elderly population. Med Care. 2002;40(suppl 4):3–18. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000020942.47004.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ulahannan SV, Duffy AG, McNeel TS, et al. Earlier presentation and application of curative treatments in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2014;60:1637–1644. doi: 10.1002/hep.27288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davila JA, Morgan RO, Richardson PA, et al. Use of surveillance for hepatocellular carcinoma among patients with cirrhosis in the United States. Hepatology. 2010;52:132–141. doi: 10.1002/hep.23615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Richardson P, Henderson L, Davila JA, et al. Surveillance for hepatocellular carcinoma: Development and validation of an algorithm to classify tests in administrative and laboratory data. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:3241–3251. doi: 10.1007/s10620-010-1387-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Faurot KR, Jonsson Funk M, Pate V, et al. Using claims data to predict dependency in activities of daily living as a proxy for frailty. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2015;24:59–66. doi: 10.1002/pds.3719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Klabunde CN, Potosky AL, Legler JM, et al. Development of a comorbidity index using physician claims data. J Clin Epidemiol. 2000;53:1258–1267. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(00)00256-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Suissa S. Immortal time bias in pharmaco-epidemiology. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;167:492–499. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rubin DB. Estimating causal effects from large data sets using propensity scores. Ann Intern Med. 1997;127:757–763. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-127-8_part_2-199710151-00064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Parsons LS. Reducing bias in a propensity score matched-pair sample using greedy matching techniques. Available at http://www2.sas.com/proceedings/sugi26/p214-26.pdf. Accessed November 24, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB. Reducing bias in observational studies using subclassification on the propensity score. J Am Stat Assoc. 1984;79:516–524. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stürmer T, Rothman KJ, Glynn RJ. Insights into different results from different causal contrasts in the presence of effect-measure modification. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2006;15:698–709. doi: 10.1002/pds.1231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rosenbaum PR. Optimal matching for observational studies. J Am Stat Assoc. 1989;84:1024–1032. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Davila JA, Duan Z, McGlynn KA, et al. Utilization and outcomes of palliative therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma: A population-based study in the United States. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2012;46:71–77. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e318224d669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schnipper LE, Davidson NE, Wollins DS, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology statement: A conceptual framework to assess the value of cancer treatment options. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:2563–2577. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.61.6706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dusetzina SB, Keating NL. Mind the gap: Why closing the doughnut hole is insufficient for increasing Medicare beneficiary access to oral chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:375–380. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.63.7736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.