This work describes a novel breast cancer awareness and early diagnosis demonstration program in three different types of health facilities in Kenya. This pilot program has the potential of being replicated on a national scale to create awareness about breast cancer and downstage its presentation.

Keywords: Breast cancer awareness and early detection, Kenya, Low- and middle-income countries, Breast cancer camps, Breast cancer diagnosis

Abstract

Background.

Breast cancer is the most common cancer of women in Kenya. There are no national breast cancer early diagnosis programs in Kenya.

Objective.

The objective was to conduct a pilot breast cancer awareness and diagnosis program at three different types of facilities in Kenya.

Methods.

This program was conducted at a not-for-profit private hospital, a faith-based public hospital, and a government public referral hospital. Women aged 15 years and older were invited. Demographic, risk factor, knowledge, attitudes, and screening practice data were collected. Breast health information was delivered, and clinical breast examinations (CBEs) were performed. When appropriate, ultrasound imaging, fine-needle aspirate (FNA) diagnoses, core biopsies, and onward referrals were provided.

Results.

A total of 1,094 women were enrolled in the three breast camps. Of those, 56% knew the symptoms and signs of breast cancer, 44% knew how breast cancer was diagnosed, 37% performed regular breast self-exams, and 7% had a mammogram or breast ultrasound in the past year. Of the 1,094 women enrolled, 246 (23%) had previously noticed a lump in their breast. A total of 157 participants (14%) had abnormal CBEs, of whom 111 had ultrasound exams, 65 had FNAs, and 18 had core biopsies. A total of 14 invasive breast cancers and 1 malignant phyllodes tumor were diagnosed

Conclusion.

Conducting a multidisciplinary breast camp awareness and early diagnosis program is feasible in different types of health facilities within a low- and middle-income country setting. This can be a model for breast cancer awareness and point-of-care diagnosis in countries with limited resources like Kenya.

Implications for Practice:

This work describes a novel breast cancer awareness and early diagnosis demonstration program in a low- and middle-income country within a limited resource setting. The program includes breast self-awareness and breast cancer education, clinical exams, and point-of-care diagnostics for women in three different types of health facilities in Kenya. This pilot program has the potential of being replicated on a national scale to create awareness about breast cancer and downstage its presentation.

Introduction

Breast cancer is the most common cancer in women worldwide, with an estimated 1.7 million new cases in 2012 [1]. Data from the population-based Nairobi Cancer Registry show that, between 2004 and 2008, breast cancer was the most common cancer among women, accounting for 23% of all cases, with an age-standardized incidence of 52 per 100,000 women per year [2].

Women in Africa have a lower incidence of breast cancer than women in developed countries (age-standardized rates [ASRs] of 36 vs. 74), but a higher mortality rate (ASR of 17 vs. 15) [3]. One reason cited is the advanced stage at diagnosis. More than 60% of Kenyan women are diagnosed with stage III–IV disease [4].

Guidelines for the screening, diagnosis, and treatment of breast cancer exist in the developed world, but economic and health systems barriers preclude the implementation of many of these recommendations in resource-limited countries [5]. The most widely adopted method for breast cancer screening is mammography; however, in Kenya and most other developing countries, high-quality, population-based mammographic screening is currently too costly to implement and sustain.

Breast self-awareness (BSA) education and clinical breast examination (CBE) may be important techniques for early detection of breast cancer in the developing world, because the primary issue in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) is early detection of palpable masses, not finding subcentimeter tumors [6]. Pilot demonstration programs are needed to evaluate the costs and benefits of different population-based awareness and early diagnosis methods for breast cancer in LMICs [7]. This paper describes a pilot program to increase breast cancer awareness and early diagnosis that we conducted at three different types of health facilities in Kenya.

Methods

The project protocol; the informed consent form; and the knowledge, attitudes, and practices (KAP) survey tool were all approved by the Research Ethical Committee of Aga Khan University Hospital, Nairobi (AKUHN).

Study Sites

There are three main types of hospitals in Kenya—public, private, and faith-based; we wanted to pilot this breast camp intervention in all three types of facilities. The following three individual sites were selected because of the interest of the local clinicians in participating in this study.

The Aga Khan Hospital, Mombasa (AKHM) (http://www.agakhanhospitals.org/mombasa) is an 82-bed, private, not-for-profit hospital in Mombasa, the second largest city in Kenya. It primarily serves the urban population of this coastal city of 1.3 million people.

Tenwek Mission Hospital (TH) (http://www.wgm.org/tenwek-hospital; http://www.tenwekhospital.org) is a 300-bed faith-based hospital in Bomet County, in the Rift Valley region of Western Kenya. It primarily serves the rural population within 50 km of the hospital, an area with approximately 750,000 people.

Kisii Teaching and Referral Hospital (KTRH) (http://www.ktrh.or.ke) is a 500-bed government hospital in Kisii town, in Western Kenya. It is a regional referral hospital, serving a predominantly rural population of approximately 3 million people in the South Nyanza, South Rift Valley, and Gusii regions of Kenya.

Stakeholder Engagement

At each site, local support groups were included in this planning, including the Breast Cancer Awareness Support Group (BCASG) (https://www.facebook.com/Breast-Cancer-Awareness-Support-Group-BCASG-162915023800474) of Mombasa, the Breast Cancer Survivors of Coast (BRECASCO) in Mombasa, and the HealthCare Rescue Centre (HRC) nongovernmental organization in Kisii.

Study Population

Women of reproductive age (15 years and older) were invited to attend.

Publicity, Marketing, and Funding

The event publicity was the responsibility of the local teams. In Mombasa, publicity included 3 weeks of radio talk shows by doctors at AKHM, with live call-in questions from the public, and a public walk 3 weeks before the event organized by BCASG and BRECASCO. At Tenwek, the camp was announced in churches 1 week before the event. In Kisii, HRC distributed flyers and posters and scheduled talk shows with local radio stations. Depending on the site, funding for the camps was provided through a combination of institutional support, the local support groups, pharmaceutical companies, and/or women’s charities.

Personnel and Equipment

The camps were staffed by a multidisciplinary team of medical officers, surgeons, radiologists, pathologists, nurses, and volunteers, including 15 members from AKUHN and 20–35 members from the local hospitals. Local hospitals provided the physical space, with private cubicles for individual participant examinations, administrative and IT support, an ultrasound machine, volunteers to administer the online survey tool, and refreshments for the women attending the camp. The AKUHN team provided the clinical and laboratory consumables.

Training

A training session was conducted by senior doctors and nurses from AKUHN and the local hospitals for all nurses and junior medical staff. The training included educational talks on breast cancer screening, symptoms and signs, and diagnosis and treatment; demonstration of breast self-exam (BSE), using breast models; demonstration of clinical breast examination, using one of the male doctors as a model; and a discussion of the algorithm for onward referral of women found to have abnormalities (Fig. 1). Each doctor and nurse trainee was encouraged to demonstrate their skills in BSE and CBE to the trainers. Volunteers from the three sites were trained in the administration of the online survey tool.

Figure 1.

Algorithm of patient flow and results of the clinical, imaging, and pathology findings.

Abbreviations: BIRADS, Breast Imaging-Reporting and Data System; CBE, clinical breast examination; FNA, fine needle aspiration.

Registration, Consent, and the KAP Survey

On the day of the camp, the participants were registered and provided with a description of the camp procedures, and a written informed consent was obtained. They were then individually administered an online KAP survey, which was previously developed by the Aga Khan Health Board–USA team and the Aga Khan Development Network eHealth Resource Centre for South-Central Asia and East Africa. This e-questionnaire is password-protected and allows real-time online data entry of 64 questions that assess the participant’s knowledge, perceptions, and practices related to breast cancer. The data variables were based on validated prognostic factors and key clinical characteristics.

Educational Talks and Palpation of Breast Prostheses

In Mombasa, nurses from AKHM and AKUHN delivered educational talks on breast health care and awareness to the groups of attendees. The talks emphasized the importance of women taking charge of their own breast health care, by being aware of their own breasts and having the confidence to detect and report any abnormalities in good time. The forum allowed participants to freely exchange their opinions, fears, and challenges, and ask questions on breast health care and breast cancer. BSE technique was demonstrated, and participants could palpate breast prostheses stuffed with different size lumps.

At Tenwek, the local medical team had recorded educational videos in both English and the local language about breast cancer screening, correct techniques of BSE, and the process of diagnosis and treatment, and these were played on large TV monitors in the designated waiting areas. Breast prostheses were also made available to let the participants experience what breast lumps feel like.

At KTRH, local nurses delivered educational talks using pictorial brochures on breast health awareness and BSE that were developed by the breast health team at AKUHN and are currently in use at the Breast Clinic at AKUHN. Women were provided with the brochures to read as they waited to be examined and were encouraged to take them home to their neighbors, friends, and relatives.

Clinical Breast Exams, Ultrasound Exams, Fine-Needle Aspiration Procedures, Core Biopsy Procedures, and Follow-Up of Women With Suspicious Findings

Clinical breast exams were performed on all participants by the trained medical officers, surgeons, and nurses in private examination rooms. Ultrasound imaging, fine-needle aspiration (FNA) cytology, and core biopsy procedures were restricted to women with an abnormal CBE or concerning symptomatology. Women less than 30 years of age with a breast lump were referred directly for FNA, whereas those 30 years of age and older were referred first to the ultrasound suite, where, based on the image findings, a decision was made by the radiologist whether to proceed with a core biopsy or an image-guided FNA. Onsite interpretation was performed for both the ultrasound images and the FNA smears. In the case of an obviously suspicious lump on CBE, a Breast Imaging-Reporting and Data System (BI-RADS) score of 4 or 5 ultrasound image, or a suspicious or positive FNA smear, a core biopsy was performed, and the patient was given an appointment slip for the following week for a consultation with a surgeon. All patients with breast lumps or breast symptoms were also seen by an examining surgeon for consultation before leaving the camp. All women above the age of 40 years were provided slips for screening mammography at a markedly discounted rate.

Statistical Analysis

Pearson’s chi-square test and Fisher’s exact test were used to assess whether the distribution of the various study parameters differed significantly across the three study sites. A p value of < .05 was considered significant.

Results

A total of 1,194 individuals came to the three breast camps; 1,094 women 15 years and above (91.7%) agreed to participate in the KAP survey and CBE. Of this total, 704 subjects were enrolled at Aga Khan Hospital, Mombasa; 87 at Tenwek Hospital; and 303 at Kisii Teaching and Referral Hospital.

Table 1 shows selected age and reproductive characteristics and other risk factors of the participants. The participants’ age ranged from 15 to 80 years, with a mean age (±SD) of 36.5 (±13.1), a median age of 35, and an interquartile range of 26–45 years. The mean age at menarche was 14.4 years (±1.8), the median age at menarche was 14 years, and the interquartile range was 13–15 years. The mean age at menarche of the women in Mombasa (14.1 years) was younger than that of the women in Tenwek (14.6 years) or Kisii (14.9 years). The median reported age at menopause was 46 years, with a range of 30–56 years. The mean age at first pregnancy was 22.3 years (±4.6), with a median age of 22 years and an interquartile range of 19–25 years. The median number of children per respondent was 3, with an interquartile range of 1–4 children. A higher proportion of women in Mombasa had a family history of breast cancer (11.9% vs. 4.6% at Tenwek and 6.3% at Kisii), and a higher proportion of women at Tenwek used hormonal contraception (24.1% vs. 8.2% at Mombasa and 8.6% at Kisii).

Table 1.

Demographic and reproductive characteristics and risk factors

Table 2 shows the breast cancer knowledge and screening practices of the enrolled participants. The knowledge of breast cancer signs and symptoms was fair (approximately 55%) and similar in all three populations. More women in Mombasa had heard of BSE and mammography than women at Tenwek or Kisii, but there was little difference in screening practices in Mombasa and Tenwek; the women in Kisii, however, were less likely to have had a CBE, mammogram, or ultrasound in the past year.

Table 2.

Breast cancer knowledge and screening practices

Of the total 1,094 women who consented to be part of the study and underwent clinical breast exams, 937 (85.6%) had normal findings, and 157 (14.4%) had abnormal findings on CBE. All of the 253 women 40 years of age and above who had a normal CBE were referred for screening mammography, but only 35 (14.3%) actually went for this exam. The patient flow and additional test findings of the 157 women with abnormal CBE findings are shown in Figure 1.

All women less than 30 years of age with palpable lumps (n = 47) were referred directly for FNA, because these were expected to have benign lesions. Of these 47, however, 4 women were referred for image-guided core biopsy because of a suspicious/malignant FNA result, and 3 of these 4 turned out to be malignant (2 invasive ductal carcinomas and 1 malignant phyllodes tumor).

Women 30 years of age or older with abnormal CBE findings (n = 110) were referred for ultrasound imaging. Of these, 51 (46.4%) had abnormalities on imaging. A total of 13 women with a BI-RADS score of 4 or 5 on ultrasound were subjected to core biopsies, and 11 of these turned out to be malignant. A total of 18 women with breast lumps that were considered benign on ultrasound had image-guided FNA, and 1 of them was reported as suspicious for malignancy on FNA and subsequently confirmed as malignant on core biopsy. There were a total of 59 benign cases diagnosed on FNA: 46 were fibroadenomas, 11 were fibrocystic change, 1 was tuberculous mastitis, and 1 was a case of duct ectasia.

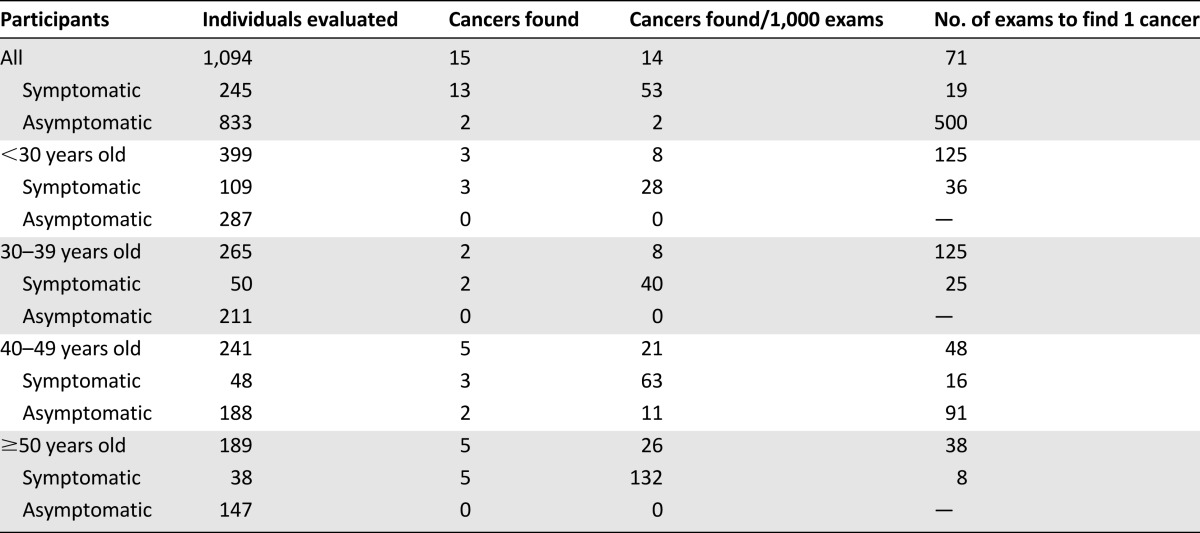

Table 3 shows that 245 of 1,094 (22.4%) of all participants, 88 of the 157 (56.1%) women with abnormal CBE findings, and 13 of the 15 (86.7%) women with malignant tumors were symptomatic (had previously noticed lumps in the breast). Table 4 shows that the cancer yield increased with increasing participant age and the presence of symptoms. No cancers were found in asymptomatic women <40 years old (498 of 1,094 = 45.5% of all participants).

Table 3.

CBE classification and diagnoses of participants with abnormal CBEs, stratified by participant symptoms

Table 4.

Cancer yield by participant age and symptoms

A total of 14 invasive ductal carcinomas were diagnosed in the three camps (7 in Mombasa, 2 at Tenwek, and 5 at Kisii), and a single case of malignant phyllodes tumor was diagnosed in Mombasa (Table 5). A total of 11 (78.6%) of the invasive ductal carcinomas were estrogen receptor-positive.

Table 5.

Age, risk factors, breast cancer screening practices, and clinicopathologic data of the malignant cases

Knowledge of the signs and symptoms of breast cancer was fair among the women with malignant tumors, with 13 of the 15 patients indicating the presence of a lump or swelling as a sign of breast cancer, and 6 women reported performing “regular” BSEs. Interestingly, 5 of these women with malignancies had been seen by a doctor for the breast problem within the past year.

Seven of the 10 malignancies diagnosed at Mombasa and Tenwek were treated and managed by local surgeons. All 5 of the cancers diagnosed at Kisii were fast-tracked through the system and scheduled for surgery within 1 month of the breast camp, but none returned for their surgery, despite several follow-up attempts.

Discussion

The aim of the current project was to pilot a novel breast cancer awareness and early diagnosis demonstration program at three different facilities in Kenya: a private not-for-profit hospital in Mombasa (an urban setting), a faith-based hospital in Bomet (a rural setting), and a public government referral hospital in Kisii (a mixed rural and urban setting). This multidisciplinary program included onsite capacity building through training local medical officers and nurses in CBE; documenting the participants’ demographic, reproductive, and risk factor data; collecting information on the participants’ breast cancer knowledge and current screening practices; educating participants on BSA; performing screening and diagnostic CBEs, breast imaging, and fine-needle aspirates, with onsite interpretation; performing core biopsies; and providing access to treatment and follow-up care.

The event publicity in each site was handled by the local teams, who used their contacts and knowledge of the local community to maximize turnout. The lower number of participants in the Tenwek camp could be explained by the shorter history of collaboration between AKUHN and Tenwek; the 1-week, predominantly church-based previsit publicity; the event being held close to a holiday period; and the 1-day duration of the camp. In a 2-day camp, such as the one in Mombasa, people have the opportunity to go home and describe their experience and encourage their female friends and relatives to show up on the second day. In Kisii, the local organizers provided widespread publicity and held the camp on a Market Day, when attendance could be encouraged by word of mouth. Our results suggest that more time should be allocated for publicity to maximize attendance.

The mean age at menarche of the women who enrolled in Mombasa (14.1 ± 1.8 years) was higher than that from published data from an urban setting in Kenya that studied primary-school girls and reported a mean age of menarche of 12.5 ± 2.8 years [8]. The mean age at menarche of the women from the rural sites (TH and KTRH) was slightly older (14.6 and 14.9 years, respectively), consistent with the findings of a Cameroonian study that reported differences in mean age at menarche between urban (13.2 years) and rural (14.3 years) areas. This urban-rural difference in the menarche age may be due to better nutritional status in the urban women [9].

The mean age at first pregnancy was older, and the number of children was fewer, in Mombasa (23.1 years old, median 2 children) than at Tenwek (21.6 years old, median 3 children) or Kisii (20.9 years old, median 3 children). These differences can possibly be attributed to better access to schools and colleges in Mombasa, resulting in a delay in the timing of fertility. Using Kenya as a case study, a World Bank working paper noted that for every year of post primary schooling completed, there is a 7.3% lower likelihood of having a child before the age of 20 years [10]. The median age at menopause for the enrolled women was 46 years, and it did not differ among our three sites, similar to the findings of a previous study from rural Western Kenya in which the median age of menopause was 48.3 years [11].

There is clearly a need for Kenyan women to be better educated about breast cancer and the possible screening tools for breast cancer. Although more than half of the 1,094 respondents were aware of the symptoms and signs of breast cancer, the proportion of women who were knowledgeable about how breast cancer was diagnosed was less than 50% in all three sites. The proportion of women who had heard of BSE was significantly higher in Mombasa (71.6%) than in Tenwek (44.8%) or Kisii (54.8%); however, fewer than half of the women in Mombasa actually practiced regular BSEs. We opted to teach the women BSE as a tool for breast cancer awareness.

Studies have shown that BSE has the potential of downsizing tumors, and, if correctly performed, women can actually detect 65% of small tumors by themselves [6, 12, 13]. However, controversy surrounds the utility of BSE and CBE for mass breast screening programs [14], and large randomized controlled trials in China and Russia showed no reduction in breast cancer mortality from using either BSE or CBE in isolation [15, 16].

Population-based screening programs are developed after considering well-documented screening test positive and negative predictive values and the risks/benefits and costs of screening in different age groups. These data are not currently known for Kenya, but our breast camp results provide some useful information in this regard. In our camps, the cancer yield increased with increasing age and the presence of symptoms. No cancers were found in asymptomatic women less than 40 years old, and only 2 of 15 malignancies (13.3%) were found in asymptomatic women of any age. Stated another way, it took 19 evaluations of symptomatic women, or 416 evaluations of asymptomatic women, to identify 1 cancer. Thus, our data suggest that it would be more cost-effective to target women older than 40 years and/or symptomatic women in a population-based screening or early detection program.

In Kenya, undergraduate medical schools, nursing schools, and clinical officer training colleges do not include education in BSA or CBE or appropriate triaging for breast cancer screening, early detection, and diagnostic investigations as part of their training curricula. Recent graduates of these training programs are usually the first contact for patients in a health facility, so this lack of training may contribute to misdiagnosis and inappropriate treatment or referral of women presenting with breast masses. It is noteworthy that 5 of the 15 women diagnosed with malignancies in the current study reported contact with a doctor for the problem in the past year. Anecdotal data suggest that many breast cancers in Kenya are misdiagnosed as infective/inflammatory lesions and are initially treated with antibiotics and anti-inflammatory drugs, thus compounding the problem of late stage at presentation.

Our data show that it is feasible to combine breast cancer awareness programs with CBE and simple diagnostic tests to provide point-of-care education and diagnosis of breast cancer in Kenya. The provision of ultrasound and fine-needle aspirates with onsite diagnosis in our camps is an example of one of the recommendations of the Diagnosis Panel of the Breast Health Global Initiative’s Global Summit in 2007, that “the simplicity of diagnostic processes is critical in a limited-resource setting, because patients may face numerous barriers that prevent repeated visits; diagnostic tests should be used in combinations that enable establishing the diagnosis in a single visit as best as possible” [7]. In our camps, a total of 165 abnormal CBEs were evaluated on site using these techniques, and 145 were found to be benign conditions, thus avoiding the need for repeated visits and allaying patient anxiety. In addition, 18 other cases had core biopsies performed, which diagnosed all 15 of the malignancies.

Other models of breast cancer screening and early detection have been tested in some LMICs. Interim results from a cluster randomized trial in India that used primary health care providers trained in CBE showed a significant downstaging of breast cancer in the screening arm when compared with the control arm [12]. Use of mobile mammographic screening units to reach remote communities and raising awareness of breast cancer screening through home visits by community health agents was an effective intervention in a rural district of Brazil [17]. Preliminary findings of a randomized controlled study from the Cairo Breast Screening trial demonstrated that a combined BSE and CBE approach for breast cancer screening resulted in downstaging of tumors in the intervention arm compared with the control arm [18].

Successful screening and diagnosis of breast cancer requires the capability to follow up and treat the patients found to have a malignancy. One of the most pressing concerns among many participants in our study was access to affordable treatment in the event that cancer was diagnosed. In many parts of East Africa, faith-based health facilities like Tenwek Hospital provide well-resourced quality care that can be readily accessed at a relatively affordable cost, but government and private facilities must also strive to provide these services.

Another barrier, fatalism, must also be recognized and confronted. After our breast camp in Kisii, the dedicated surgical and paramedical health team fast-tracked all five of the patients diagnosed with malignancies through the system and booked them for surgery within a month, but none of them returned for surgery despite several follow-up efforts. Anecdotal evidence suggests that the community in Kisii links any breast surgical procedures with certainty of a fatal outcome.

Evaluating the reasons for this lack of compliance with treatment recommendations was beyond the scope of this study, but this is an extremely important finding that must be addressed in future studies. Previous studies have shown that poverty and its associated ills, including undereducation and lack of health care access, force people to focus on day-to-day existence and ignore early cancer symptoms, leading to late diagnosis and poor outcomes. Poor outcomes, in turn, further reinforce a fatalistic outlook related to cancers [19, 20]. These observations underscore that local cultural context and sensitivities must be recognized when planning for any intervention and that there is need for a concerted effort to identify and overcome barriers to treatment in such populations.

Conclusion

Our breast cancer awareness and diagnosis camp model demonstrates that a multidisciplinary approach—which involves stakeholder engagement, judicious use of available resources, public education, local health worker training, and a collaboration of skilled private and public medical personnel—has the potential to provide an appropriate breast cancer awareness, early detection, diagnosis, and treatment program in Kenya. Additional research is needed to determine the costs and benefits of implementing such camps more broadly as an educational and early detection program.

For a cancer program to be effective in a LMIC setting, there is need for a paradigm shift in the way cancer screening, early detection, and treatment activities are conducted. A local context-sensitive one-stop shop incorporating education, screening, early detection, diagnosis, and management planning may be one key to downstaging disease presentation and reducing mortality.

This article is available for continuing medical education credit at CME.TheOncologist.com.

Acknowledgments

We thank the following individuals and institutions for administrative support: the senior leadership team of Aga Khan University Hospital, Nairobi (AKUHN); Mr. Noorali Momin, Dr. Paul Makau, and Dr. Sultana Sherman of Aga Khan Hospital, Mombasa (AKHM); Dr. Chupp and Dr. Spears of Tenwek Mission Hospital (TH); and Dr. Oigara of Kisii Teaching and Referral Hospital (KTRH). We thank the following individuals and institutions for participating in data collection: the nurses, doctors, and support staff of AKUHN, AKHM, TH, and KTRH; Beckie Smith and volunteers from the Breast Cancer Awareness Support Group of Mombasa and the Breast Cancer Survivors of Coast in Mombasa; Rose Oigara; and the HealthCare Rescue Centre nongovernmental organization (NGO) in Kisii. The following institutions provided funding and contributions: AKUHN, AKHM, TH, KTRH, BCASG of Mombasa, BRECASCO in Mombasa, and the HRC NGO in Kisii. The analysis of this study was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the National Cancer Institute. The survey tool was designed and developed by Aga Khan Health Board-USA team and the Aga Khan Development Network eHealth Resource Centre for South-Central Asia and East Africa. Data management was provided by Donstefano Muninzwa of AKUHN.

Footnotes

For Further Reading: Lydia E. Pace, Tharcisse Mpunga, Vedaste Hategekimana et al. Delays in Breast Cancer Presentation and Diagnosis at Two Rural Cancer Referral Centers in Rwanda. The Oncologist 2015;20:780–788.

Implications for Practice: Breast cancer rates are increasing in low- and middle-income countries, and case fatality rates are high, in part because of delayed diagnosis and treatment. This study examined the delays experienced by patients with breast cancer at two rural Rwandan cancer facilities. Both patient delays (the interval between symptom development and the patient’s first presentation to a healthcare provider) and system delays (the interval between the first presentation and diagnosis) were long. The total delays were the longest reported in published studies. Longer delays were associated with more advanced-stage disease. These findings suggest that an opportunity exists to reduce breast cancer mortality in Rwanda by addressing barriers in the community and healthcare system to promote earlier detection.

Author Contributions

Conception/Design: Shahin Sayed, Zahir Moloo

Provision of study material or patients: Rose Ndumia, Anderson Mutuiri, Ronald Wasike, Charles Wahome, Mohamed Abdihakin, Riaz Kasmani, Carol D. Spears, Raymond Oigara, Elizabeth B. Mwachiro, Satya V. P. Busarla, Kibet Kibor, Abdulaziz Ahmed, Jonathan Wawire, Omar Sherman

Collection and/or assembly of data: Shahin Sayed, Zahir Moloo, Amyn Allidina, Rose Ndumia, Anderson Mutuiri, Ronald Wasike, Charles Wahome, Mohamed Abdihakin, Riaz Kasmani, Carol D. Spears, Raymond Oigara, Elizabeth B. Mwachiro, Satya V. P. Busarla, Kibet Kibor, Abdulaziz Ahmed, Jonathan Wawire, Omar Sherman

Data analysis and interpretation: Shahin Sayed, Zahir Moloo, Anthony Ngugi, Jo Anne Zujewski, Sanford M. Dawsey

Manuscript writing: Shahin Sayed, Anthony Ngugi, Amyn Allidina, Mansoor Saleh, Jo Anne Zujewski, Sanford M. Dawsey

Final approval of manuscript: Shahin Sayed, Jo Anne Zujewski, Sanford M. Dawsey

Disclosures

The authors indicated no financial relationships.

References

- 1.Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, et al. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65:87–108. doi: 10.3322/caac.21262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Korir A, Okerosi N, Ronoh V, et al. Incidence of cancer in Nairobi, Kenya (2004-2008) Int J Cancer. 2015;137:2053–2059. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: Sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer. 2015;136:E359–E386. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sayed S, Moloo Z, Wasike R, et al. Is breast cancer from Sub Saharan Africa truly receptor poor? Prevalence of ER/PR/HER2 in breast cancer from Kenya. Breast. 2014;23:591–596. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2014.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anderson BO, Shyyan R, Eniu A, et al. Breast cancer in limited-resource countries: An overview of the Breast Health Global Initiative 2005 guidelines. Breast J. 2006;12(suppl 1):S3–S15. doi: 10.1111/j.1075-122X.2006.00199.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dey S. Preventing breast cancer in LMICs via screening and/or early detection: The real and the surreal. World J Clin Oncol. 2014;5:509–519. doi: 10.5306/wjco.v5.i3.509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shyyan R, Sener SF, Anderson BO, et al. Guideline implementation for breast healthcare in low- and middle-income countries: Diagnosis resource allocation. Cancer. 2008;113(suppl):2257–2268. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ogeng’o DN, Obimbo MM, Ogeng’o JA. Menarcheal age among urban Kenyan primary school girls. Acta Paediatr. 2011;100:758–761. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2011.02152.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pasquet P, Biyong AM, Rikong-Adie H, et al. Age at menarche and urbanization in Cameroon: Current status and secular trends. Ann Hum Biol. 1999;26:89–97. doi: 10.1080/030144699283001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferré C. Age at First Child Does Education Delay Fertility Timing? The Case of Kenya. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 4833. Washington, DC: World Bank South Asia Region Human Development Division, 2009.

- 11.Noreh J, Sekadde-Kigondu C, Karanja JG, et al. Median age at menopause in a rural population of western Kenya. East Afr Med J. 1997;74:634–638. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mittra I, Mishra GA, Singh S, et al. A cluster randomized, controlled trial of breast and cervix cancer screening in Mumbai, India: Methodology and interim results after three rounds of screening. Int J Cancer. 2010;126:976–984. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huguley CM, Jr, Brown RL, Greenberg RS, et al. Breast self-examination and survival from breast cancer. Cancer. 1988;62:1389–1396. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19881001)62:7<1389::aid-cncr2820620725>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Larkin M. Breast self examination does more harm than good, says task force. Lancet. 2001;357:2109. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)05238-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thomas DB, Gao DL, Self SG, et al. Randomized trial of breast self-examination in Shanghai: Methodology and preliminary results. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1997;89:355–365. doi: 10.1093/jnci/89.5.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kösters JP, Gotzsche PC. Cochrane review: Regular self-examination or clinical examination for early detection of breast cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;(2):CD003373. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mauad EC, Nicolau SM, Moreira LF, et al. Adherence to cervical and breast cancer programs is crucial to improving screening performance. Rural Remote Health. 2009;9:1241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miller AB. Practical applications for clinical breast examination (CBE) and breast self-examination (BSE) in screening and early detection of breast cancer. Breast Care (Basel) 2008;3:17–20. doi: 10.1159/000113934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Freeman HP. Cancer in the socioeconomically disadvantaged. CA Cancer J Clin. 1989;39:266–288. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.39.5.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Drew EM, Schoenberg NE. Deconstructing fatalism: Ethnographic perspectives on women’s decision making about cancer prevention and treatment. Med Anthropol Q. 2011;25:164–182. doi: 10.1111/j.1548-1387.2010.01136.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]