Abstract

Evolutionarily conserved structure-selective endonuclease MUS81 forms a complex with EME1 and further associates with another endonuclease SLX4-SLX1 to form a four-subunit complex of MUS81-EME1-SLX4-SLX1, coordinating distinctive biochemical activities of both endonucleases in DNA repair. Viral protein R (Vpr), a highly conserved accessory protein in primate lentiviruses, was previously reported to bind SLX4 to mediate down-regulation of MUS81. However, the detailed mechanism underlying MUS81 down-regulation is unclear. Here, we report that HIV-1 Vpr down-regulates both MUS81 and its cofactor EME1 by hijacking the host CRL4-DCAF1 E3 ubiquitin ligase. Multiple Vpr variants, from HIV-1 and SIV, down-regulate both MUS81 and EME1. Furthermore, a C-terminally truncated Vpr mutant and point mutants R80A and Q65R, all of which lack G2 arrest activity, are able to down-regulate MUS81-EME1, suggesting that Vpr-induced G2 arrest is not correlated with MUS81-EME1 down-regulation. We also show that neither the interaction of MUS81-EME1 with Vpr nor their down-regulation is dependent on SLX4-SLX1. Together, these data provide new insight on a conserved function of Vpr in a host endonuclease down-regulation.

Keywords: E3 ubiquitin ligase, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), proteasome, protein degradation, viral protein, Western blot

Introduction

Primate lentiviruses encode several common accessory proteins, including viral protein R (Vpr),2 viral protein X (Vpx), viral protein U, negative regulatory factor, and viral infectivity factor. These proteins were once thought to be non-essential but were later found to be critical for in vivo viral replication (1, 2). Among these proteins, Vpr and Vpx are closely related and similar in size, at about 100 amino acids (3). Vpr is present in all types of primate lentiviruses, including HIV-1, HIV-2, and SIV, although Vpx is only found in HIV-2 and some SIV strains (1, 4, 5).

Vpr, as a virion-associated protein, is implicated in many processes that promote HIV-1 infectivity. It is packaged into viral particles and has been suggested to be involved in nuclear import of the viral pre-integration complex, a key step for successful infection in non-dividing cells such as macrophages (6–9). Vpr has been implicated as a transcriptional activator and viral replication activator (10–12). Vpr was also reported to induce T-cell apoptosis and to induce differentiation in a rhabdomyosarcoma cell line (13–17).

Vpr expression in cycling cells results in G2/M cell cycle arrest by inducing the ataxia telangiectasia and Rad3-related (ATR)-mediated DNA-damage checkpoint, which may favor viral replication (18–21). However, the detailed mechanism of Vpr-induced G2/M arrest is not yet clear. Several lines of evidence suggest that G2 arrest requires interaction of Vpr with the CRL4 E3 ubiquitin ligase complex, comprising DDB1, CUL4, and RBX1, via its cellular partner DCAF1 (22–30). DCAF1 is a substrate receptor component of the CRL4 (31–33). One plausible hypothesis is that Vpr usurps the CRL4-DCAF1 complex to promote down-regulation of unknown cell cycle regulatory factors via the proteasome-dependent pathway (34–36). In this case, down-regulation of the unknown factor(s) would activate ATR-mediated checkpoint signaling and induce G2 arrest. In line with this hypothesis, mutagenesis studies have shown that a Vpr mutant with reduced DCAF1 binding, Q65R, lacks the ability to induce G2 arrest (22, 25, 28, 37). Furthermore, single mutation at Arg-80 (R80A) results in abrogation of Vpr-mediated G2 cell cycle arrest without affecting DCAF1 interaction (10, 22, 25, 38–40). These reports suggest that the unidentified cell cycle regulatory factor(s) is recruited to the CRL4-DCAF1 complex via the C terminus of Vpr.

The MUS81-EME1 and MUS81-EME2 complexes are conserved DNA structure-selective endonucleases and play essential roles in homologous recombination and replication fork processing and repair (41, 42). The C-terminal regions of EME1 (total of 570 residues) and EME2 (total of 379 residues) are highly homologous with more than 60% sequence similarity in human (43, 44). Multiple studies have suggested that these complexes are involved in maintenance of genomic stability and damaged DNA processing (43–47). Purified recombinant MUS81-EME1 recognizes and preferentially cleaves several DNA structures, including 3′-flap, aberrant replication forks, and nicked Holliday junctions (45, 48). Loss of MUS81 or EME1, or their disruption, results in genomic instability and hypersensitivity to DNA cross-linking agents such as mitomycin C and platinum compounds, due to DNA repair defects (49, 50).

Together with another structure-selective endonuclease, SLX4-SLX1, MUS81-EME1 defines one of two major Holliday junction resolution pathways in human cells (51, 52). SLX4 provides a scaffold for multiple factors, and its C terminus binds the catalytic SLX1 to form an SLX4-SLX1 complex. SLX4-SLX1 further associates with MUS81-EME1, forming a stable holoenzyme termed SLX4com (51). The role of MUS81-EME1 in Holliday junction resolution and DNA interstrand cross-link repair requires its interaction with SLX4 in human cells (51–53).

Recently, human SLX4com, comprising SLX4, SLX1, MUS81, and EME1, was reported to be a target of HIV-1 Vpr (54). In particular, Vpr was shown to directly bind SLX4 and was postulated to untimely activate the SLX4com via the CRL4-DCAF1 complex. These interactions were proposed to lead to aberrant DNA cleavage and cell cycle arrest (54). Additionally, MUS81 was reported to be down-regulated by Vpr, which was further confirmed by another two groups (55, 56). However, the detailed mechanisms of MUS81 down-regulation and its relation to Vpr-induced G2 arrest are not clear. In the work described here, we report Vpr-mediated down-regulation of both MUS81 and its partners EME1 and EME2. Vpr executes this task by hijacking host CUL4-DCAF1 E3 ubiquitin ligase and targeting MUS81-EME1 and MUS81-EME2 for degradation in a proteasome-dependent manner, which could be inhibited by MG132. Multiple Vpr proteins, from either HIV-1 or SIV isolated from chimpanzee, down-regulate MUS81 and EME1, suggesting that it is a conserved function of Vpr. Strikingly, we further show that MUS81-EME1 down-regulation does not require SLX4-SLX1. We also find that Vpr mutants defective for G2 arrest are still capable of down-regulating MUS81-EME1, suggesting that G2 arrest is not correlated with MUS81-EME1 down-regulation.

Results

HIV-1 Vpr but Not SIV Vpx Down-regulates MUS81

To confirm previous reports of Vpr-induced down-regulation of MUS81, we co-transfected MUS81 and HIV-1 NL4-3 Vpr plasmids into HEK293T cells. As shown in Fig. 1A, the level of MUS81 was dramatically decreased in a Vpr dose-dependent manner. Because MUS81 forms a complex with its cofactor EME1 (or EME2), we wondered whether EME1 influences the stability of MUS81. We therefore co-transfected EME1 with MUS81 (Fig. 1B). The level of MUS81 increased in accordance with the amount of EME1-expressing plasmid (Fig. 1B, lanes 1–4). When Vpr was present, the level of MUS81 also increased with EME1 (Fig. 1B, lanes 5–8); however, the level of MUS81 was always lower in the presence of Vpr. These results suggest that MUS81 is down-regulated by Vpr irrespective of its quaternary state. We also interrogated whether endogenous MUS81 could be down-regulated by Vpr. When Vpr alone was transfected into HEK293T cells, endogenous MUS81 indeed decreased with increasing amounts of Vpr (Fig. 1C).

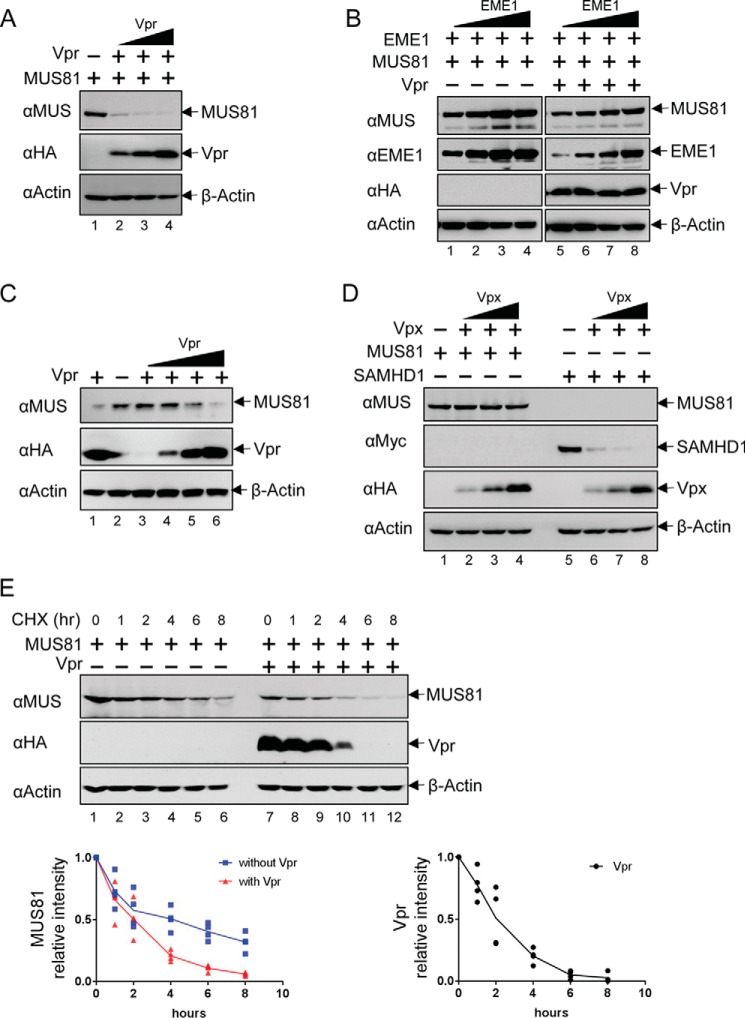

FIGURE 1.

Vpr but not Vpx down-regulates MUS81. A, MUS81 was transiently co-transfected with increasing amounts of VprHIV-1 NL4-3. At 48 h post-transfection, cells were harvested and analyzed by Western blotting. B, MUS81 was co-transfected with increasing amounts of EME1 and empty vector or Vpr HIV-1 NL4-3 plasmids. The same amounts of MUS81 and EME1 plasmids were used for lanes 1 and 5, lanes 2 and 6, lanes 3 and 7, and lanes 4 and 8. C, HEK293T cells were transfected with increasing amounts of VprHIV-1 NL4-3 plasmid. The endogenous level of MUS81 was analyzed by Western blotting. D, MUS81 or SAMHD1 was co-transfected with an increasing amount of VpxSIVmac. E, HEK293T cells were incubated with 20 μg/ml cycloheximide, 40 h after transfection with the indicated plasmids. The levels of MUS81 and Vpr were analyzed by Western blotting after the indicated times. The intensity of bands corresponding to MUS81 and Vpr were quantified from four independent experiments.

Because Vpr and Vpx are closely related and have evolved from a common ancestor, we investigated whether Vpx could also down-regulate MUS81 (Fig. 1D). The level of MUS81 was not affected by co-transfection of Vpx (VpxSIVmac) from SIV that infects the macaque monkey. The level of human SAMHD1, a known target of VpxSIVmac, however, was significantly lower with increasing amounts of VpxSIVmac. Together, these results suggest that MUS81 is down-regulated by VprHIV-1 NL4-3 but not by VpxSIVmac.

To further investigate Vpr-dependent down-regulation of MUS81, chase assays were carried out with an inhibitor of de novo protein synthesis, cycloheximide. In the presence of cycloheximide, the intensity of the band corresponding to MUS81 decreased significantly over an 8-h period (Fig. 1E). Importantly, the same band disappeared more rapidly in the presence of Vpr. Vpr also decreased after cycloheximide treatment. Together, these results suggest that Vpr enhances down-regulation of MUS81.

Both MUS81 and Its Co-factor EME1 or EME2 Are Down-regulated by HIV-1 Vpr

MUS81 associates with EME1 or EME2 and functions as a DNA structure-selective endonuclease in mammalian cells. Therefore, we asked whether EME1 and EME2 are also down-regulated in a Vpr-dependent manner, along with MUS81. HEK293T cells were transiently co-transfected with MUS81, EME1 (or EME2), and VprHIV-1 NL4-3-expressing plasmids, and protein levels were interrogated 48 h after transfection. In agreement with previous results, MUS81 decreased in a Vpr dose-dependent manner. As shown in Fig. 2, A and B, both EME1 and EME2 were down-regulated by VprHIV-1 NL4-3. Endogenous MUS81, EME1, and EME2 were also down-regulated by the Vpr (Fig. 2C). Because EME1 and EME2 behaved similarly in response to VprHIV-1 NL4-3 co-expression, the remainder of our studies focused on MUS81-EME1.

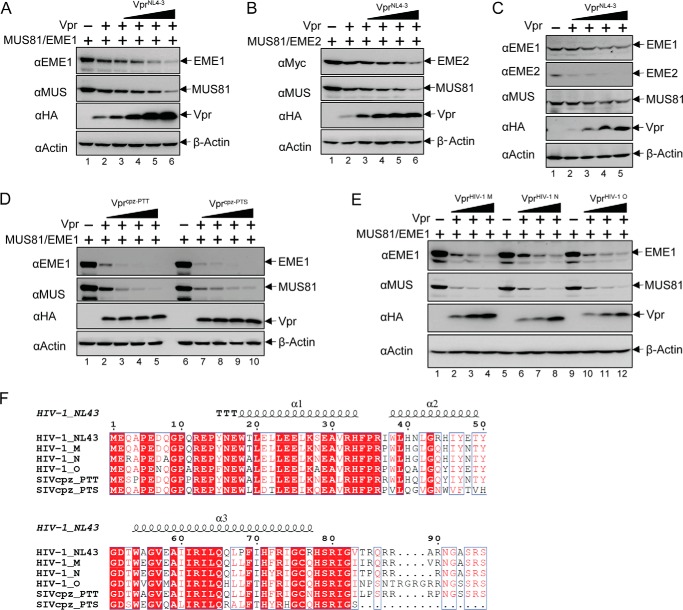

FIGURE 2.

Both MUS81 and its cofactors EME1 and EME2 are down-regulated by Vpr from multiple species. A and B, MUS81 and EME1 plasmids (A) or MUS81 and EME2 plasmids (B) were transiently co-transfected with increasing amounts of VprHIV-1 NL4-3 plasmid. At 48 h post-transfection, cells were harvested and analyzed by Western blotting. C, endogenous levels of MUS81, EME1, and EME2 were analyzed with increasing amounts of VprHIV-1 NL4-3. D and E, MUS81 and EME1 plasmids were co-transfected with increasing amounts of plasmid encoding Vpr isolated from SIV that infects chimpanzee, Vprcpz-PTT and Vprcpz-PTS (D), or encoding Vpr from HIV-1 group M, N, or O, VprHIV-1 M, VprHIV-1 N, and VprHIV-1 O (E). All experiments were repeated three times with equivalent results. F, sequence alignment of the Vpr proteins used in A–D was performed with Clustal Omega (68) and colored by ESPript 3.0 (69).

To explore whether Vpr proteins from other strains also function in both MUS81 and EME1 down-regulation, we examined the cellular levels of MUS81 and EME1 after co-transfection with Vpr from viruses isolated from diverse species, including chimpanzee SIV PTT and PTS (Fig. 2D), and HIV-1 group M, N, and O (Fig. 2E). Vpr from all these strains efficiently down-regulated both MUS81 and EME1. Sequence analysis of these Vpr proteins suggests a conserved N-terminal and central region (Fig. 2F). The C-terminal region of these Vpr proteins, however, is variable. This may imply that the C-terminal part is not important for MUS81-EME1 down-regulation.

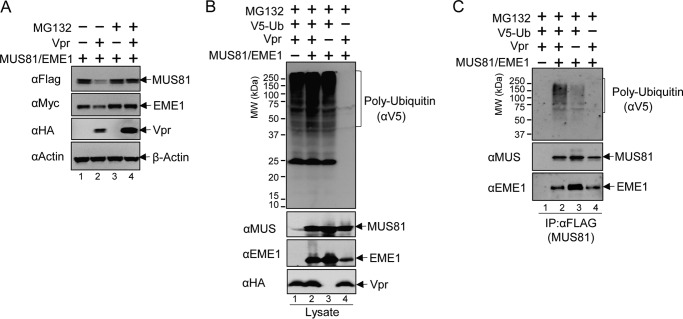

MUS81-EME1 Down-regulation Is Mediated via a Ubiquitin/Proteasome-related Pathway

To determine whether MUS81-EME1 down-regulation is mediated via a ubiquitin/proteasome-related pathway, we treated MUS81-EME1/Vpr co-transfected cell cultures with MG132, an inhibitor of the proteasome. We used VprHIV-1 NL4-3 for this experiment and the remainder of our studies. MG132 effectively restored MUS81 and EME1 levels (Fig. 3A). This suggests Vpr-dependent down-regulation of MUS81-EME1 requires the proteasome. The level of Vpr increased with MG132 treatment. This is consistent with the previous observation that Vpr is also degraded by the proteasome (28). To further examine the role of the proteasome-dependent pathway, we co-expressed ubiquitin with MUS81, EME1, and Vpr. As shown in Fig. 3B, ubiquitin expression resulted in a strong poly-ubiquitination signal in whole cell extracts. Immunoprecipitation with an anti-FLAG antibody (Fig. 3C), to pull down FLAG-tagged MUS81, revealed stronger poly-ubiquitination signals (lane 2) in the presence of Vpr. Taken together, these results suggest that Vpr induces down-regulation of MUS81-EME1 via ubiquitination and a proteasome-dependent pathway.

FIGURE 3.

Vpr mediates MUS81-EME1 down-regulation via the ubiquitin/proteasome pathway. A, MUS81 and EME1 plasmids were co-transfected with empty vector plasmid or Vpr plasmid. At 42 h post-transfection, DMSO or MG132 (10 μm final concentration) in DMSO were added to the cell culture. Six hours later, cells were harvested and analyzed by Western blotting. B, MUS81 and EME1 plasmids were co-transfected with empty vector or Vpr and/or ubiquitin plasmid as indicated. Cells were treated with MG132 (10 μm final concentration) at 42 h post-transfection for 6 h. C, cell lysates from B were subjected to co-immunoprecipitation (IP) with anti-FLAG antibody, and elution fractions from co-immunoprecipitation with FLAG peptides were analyzed by Western blotting. All experiments were repeated three times with similar results.

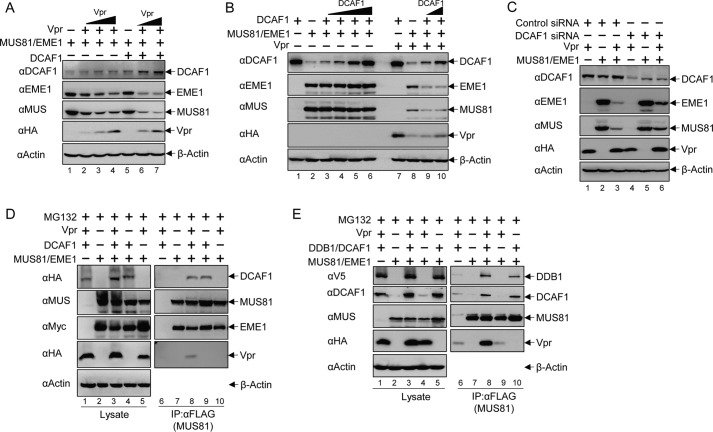

Vpr usurps the CRL4-DCAF1 E3 ubiquitin ligase to down-regulate its host cellular targets via the ubiquitination/proteasome pathway. Previous studies by Laguette et al. (54) suggested that Vpr uses the CRL4-DCAF1 E3 ubiquitin ligase to down-regulate MUS81. Thus, we investigated the role of CRL4-DCAF1 in Vpr-induced MUS81 down-regulation. Transient co-expression of DCAF1 resulted in significant enhancement of Vpr-induced MUS81 down-regulation (Fig. 4A). To further confirm the role of DCAF1 in MUS81-EME1 down-regulation, we performed titration of DCAF1 plasmid with a stable amount of control plasmid or Vpr plasmid (Fig. 4B). In the absence of Vpr, the levels of MUS81 and EME1 were similar, despite the increasing level of DCAF1; however, when Vpr was present, DCAF1 indeed dramatically promoted down-regulation of both MUS81 and EME1. Therefore, DCAF1 and Vpr cooperate in MUS81-EME1 down-regulation. Of note, consistent with a previous report (28), overexpression of DCAF1 resulted in stabilization of Vpr. Furthermore, knockdown of endogenous DCAF1 by siRNA reduced Vpr-dependent down-regulation of MUS81 (Fig. 4C).

FIGURE 4.

CRL4-DCAF1 E3 ubiquitin ligase is involved in Vpr-mediated MUS81-EME1 down-regulation. A, MUS81 and EME1 plasmids were co-transfected with increasing amounts of Vpr or balanced empty vector plasmid and empty vector or DCAF1 plasmids as indicated. 48 h later, cells were harvested, and some lysates were analyzed by Western blotting with appropriate antibodies. B, MUS81 and EME1 plasmids were co-transfected with increasing amounts of DCAF1 or balanced empty vector plasmids and empty vector or Vpr plasmids. C, DCAF1 siRNA or control siRNA was transfected 24 h prior to co-transfection of Vpr, MUS81, EME1, or balanced empty vector plasmids as indicated. D, MUS81 and EME1 plasmids were co-transfected with Vpr and/or DCAF1 plasmids, which were balanced by empty vector plasmids. 42 h later, MG132 (10 μm final concentration) in DMSO or DMSO only was added to the cell culture. After 6 h, cells were harvested, and some lysates were analyzed by Western blotting. Co-immunoprecipitation (IP) with anti-FLAG antibody was performed and analyzed by immunoblotting. E, plasmids expressing MUS81, Vpr, DCAF1, and DDB1 were co-transfected into cells as indicated. Protein levels in cell lysates and co-immunoprecipitation were analyzed as described above. All experiments were repeated three times with similar results.

To further confirm the role of DCAF1 in MUS81-EME1 down-regulation, we performed co-immunoprecipitation experiments with FLAG-tagged MUS81 (Fig. 4D). Interestingly, DCAF1 associated with the MUS81-EME1 complex even in the absence of Vpr (Fig. 4D, right-panel, lane 9). Vpr, however, required DCAF1 to associate with MUS81-EME1 (Fig. 4D, right panel, compare lanes 8 and 10). These results suggest that DCAF1 is a natural partner of MUS81-EME1 and bridges the interaction between MUS81-EME1 and Vpr. To further examine the association of components of the CRL4 E3 ubiquitin ligase in this complex, we co-expressed DDB1, DCAF1, Vpr, and MUS81-EME1. As shown in Fig. 4E, DDB1, the substrate adaptor of the CRL4, could also be detected in the MUS81-EME1 co-immunoprecipitation fractions, regardless of whether Vpr was present. Taken together, the MUS81-EME1 complex interacts with the CRL4-DCAF1 E3 ubiquitin ligase and is down-regulated by the same ligase subverted by Vpr.

G2 Arrest and MUS81-EME1 Down-regulation Are Separate Functions of HIV-1 Vpr

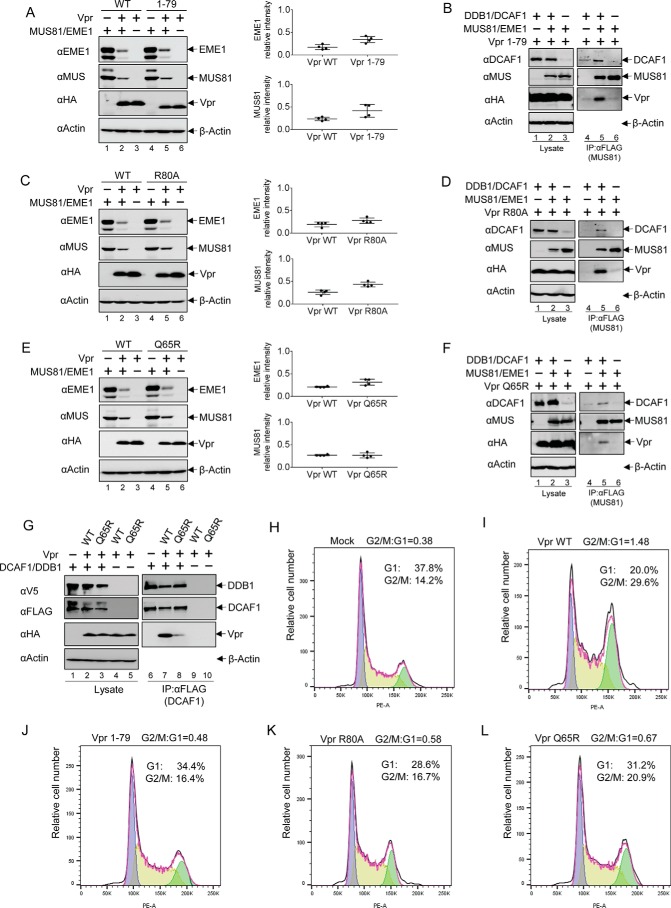

Vpr proteins from different viral strains, with diverse C termini, all retained their ability to down-regulate MUS81-EME1 (Fig. 2). We thus wondered whether the Vpr C-terminal domain is required for MUS81-EME1 down-regulation. We first tested MUS81-EME1 down-regulation with a C-terminally truncated mutant Vpr (residues 1–79). As shown in Fig. 5A, the MUS81-EME1 complex was efficiently down-regulated by Vpr(1–79). To further explore the interaction between Vpr(1–79) and MUS81-EME1, we performed a MUS81 co-immunoprecipitation experiment (Fig. 5B). Vpr(1–79) was observed to co-immunoprecipitate with MUS81 (Fig. 5B, lane 5). Thus, residues 80–96 of Vpr are not required for MUS81-EME1 interaction and down-regulation.

FIGURE 5.

Vpr mutants that lack G2 arrest activity down-regulate MUS81-EME1. A, MUS81 and EME1 plasmids were co-transfected with WT Vpr or a C-terminally truncated Vpr mutant 1–79 plasmid, and empty vector plasmid was added to balance total plasmid in HEK293T cells. After 48 h of transfection, cells were harvested, and lysates were analyzed by immunoblotting. Intensity of bands corresponding to MUS81 and EME1 was quantified from four independent experiments. B, DDB1, DCAF1, MUS81, EME1, and Vpr(1–79)-encoding plasmids, along with empty vector plasmids, were transfected as indicated. FLAG-tagged MUS81 proteins were immunoprecipitated (IP) with anti-FLAG antibody from cell lysates and analyzed with immunoblotting. C, MUS81 and EME1 plasmids were co-transfected with Vpr R80A or Vpr WT plasmids. D, combinations of MUS81, EME1, DDB1, DCAF1, and Vpr R80A were transfected as indicated. Proteins associated with MUS81 were analyzed as described above. E, MUS81 and EME1 plasmids were co-transfected with Vpr Q65R plasmid or Vpr WT plasmid, which were balanced by empty vector plasmid. F, Vpr Q65R plasmids were transiently expressed in cells along with combinations of MUS81, EME1, DDB1, and DCAF1 plasmids. MUS81-associated proteins were analyzed as describe above. G, Vpr WT or Q65R mutant plasmids were co-transfected with DDB1 and DCAF1 plasmids. FLAG-tagged DCAF1 proteins were immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG antibody from cell lysates, and associated proteins were analyzed by Western blotting. H and J, cell cycle analysis of HEK293T cells transiently transfected with empty vector plasmid (H), Vpr WT (I), Vpr(1–79) (J), Vpr R80A (K), or Vpr Q65R (L) plasmid. The ratio of cells in G2/M relative to those in G1 is indicated.

Because Vpr residues in the C-terminal region are important for its G2 arrest activity, we asked whether Vpr-induced G2 arrest activity is independent of MUS81-EME1 down-regulation. We thus tested a Vpr mutant, R80A, that is deficient in inducing cell cycle arrest (10, 22, 38, 39). The R80A mutant still down-regulates MUS81-EME1 to levels comparable with the wild type protein (Fig. 5C). Furthermore, Vpr R80A associates with MUS81-EME1 as well as DDB1/DCAF1 (Fig. 5D). This suggests the function of MUS81-EME1 down-regulation by Vpr is independent of its activity in G2 arrest. An analysis of Vpr Q65R, another mutant defective in G2 arrest (22, 25, 28, 37), further supports this conclusion (Fig. 5, E and F). Vpr Q65R was previously shown to be impaired in DCAF1 binding (22, 25, 26). This was confirmed in our co-immunoprecipitation assay (Fig. 5G). Thus, interaction of Vpr with MUS81-EME1 and DCAF1 may overcome the negative effect of Q65R mutation in DCAF1 binding (Fig. 5F).

To ensure Vpr mutants are defective in cell cycle arrest activity, HEK293T cells were transiently transfected with empty vector plasmids, Vpr WT, residues 1–79, R80A, and Q65R (Fig. 5, H–L). Cells expressing Vpr WT showed significant accumulation at G2/M phase. In contrast, Vpr mutants had minimal to moderate effects on cell cycle arrest.

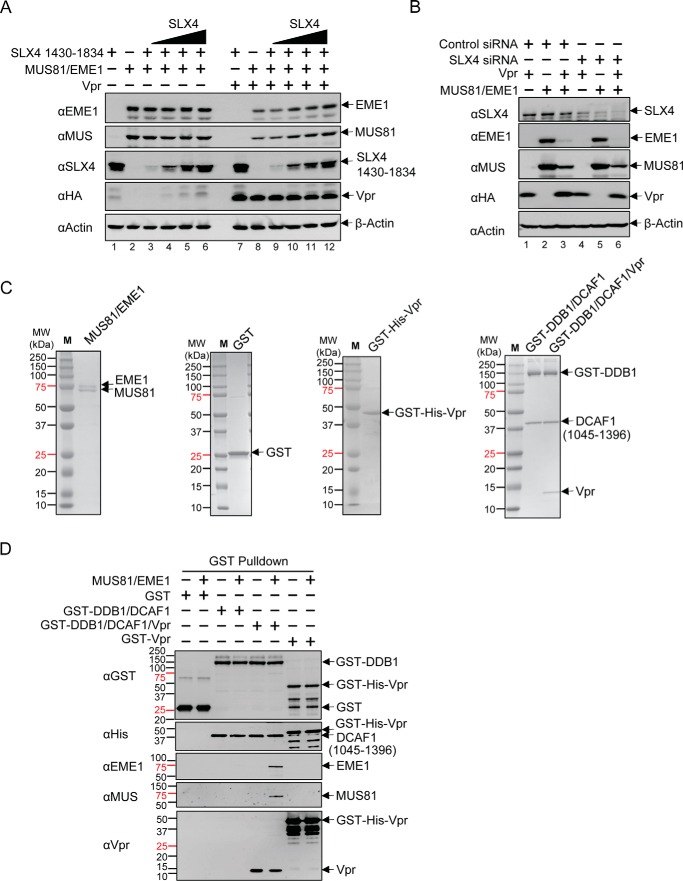

SLX4 Is Not Required for DDB1-DCAF1-Vpr-MUS81-EME1 Complex Formation

Previous studies by Laguette et al. (54) suggested that Vpr directly binds the C-terminal region of SLX4. Because MUS81-EME1 directly associates with SLX4-SLX1, SLX4 may mediate the interaction between MUS81-EME1 and CRL4-DCAF1-Vpr. In this case, Vpr may promote MUS81-EME1 and DDB1-DCAF1 complex formation via SLX4, and co-expression of SLX4 would result in facilitated Vpr-dependent down-regulation of MUS81-EME1. To address this possibility, a C-terminal domain of SLX4 (residues 1430–1834), competent for Vpr, SLX1, and MUS81-EME1 binding (54, 57), was co-transfected with MUS81-EME1 with or without Vpr (Fig. 6A). Surprisingly, co-expression of SLX4 did not promote MUS81-EME1 down-regulation. In fact, with increasing amounts of SLX4, the levels of MUS81 and EME1 were restored even when Vpr was present. This result does not support the model that Vpr down-regulates MUS81-EME1 through SLX4. On the contrary, SLX4 competes with CRL4-DCAF1-Vpr for MUS81-EME1. In other words, MUS81-EME1 down-regulation by Vpr in our system is likely independent of the SLX4/Vpr interaction. However, the truncated SLX4 may sequester Vpr or CRL4-DCAF1-Vpr and interfere with MUS81-EME1 down-regulation. Nevertheless, siRNA-mediated knockdown of SLX4 did not affect down-regulation of MUS81 and EME1 in the presence of Vpr (Fig. 6B).

FIGURE 6.

Vpr-dependent down-regulation of MUS81-EME1 is independent of SLX4. A, HEK293T cells were transfected with MUS81 and EME1 plasmids, with increasing amounts of SLX4 plasmid along with Vpr or empty vector plasmid as indicated. Cells were harvested, and proteins levels were analyzed by immunoblotting with appropriate antibodies. B, SLX4 siRNA or control siRNA was transfected 24 h prior co-transfection with the indicated combinations of Vpr, MUS81, EME1, or balanced empty plasmid. C, purified MUS81·EME1, GST, GST-His6-Vpr, GST-DDB1·DCAF1, and GST-DDB1·DCAF1·Vpr complexes were separated by SDS-PAGE and stained with Coomassie Blue. D, GST, GST-His6-Vpr, GST-DDB1·DCAF1, or GST-DDB1·DCAF1·Vpr complex was incubated with recombinant MUS81-EME1. Bound fractions were analyzed by Western blotting. All experiments were repeated three times with similar results.

To further test this hypothesis and to minimize the influence of unknown factors present in cells, we performed an in vitro pulldown assay with purified recombinant proteins (Fig. 6C). GST fusion DDB1 in complex with DCAF1 was assayed for MUS81-EME1 binding with or without Vpr (Fig. 6D). We detected an interaction between DDB1/DCAF1 and MUS81-EME1 only in the presence of Vpr. Taken together, these results suggest Vpr-mediated down-regulation of MUS81-EME1 does not require SLX4-SLX1.

Discussion

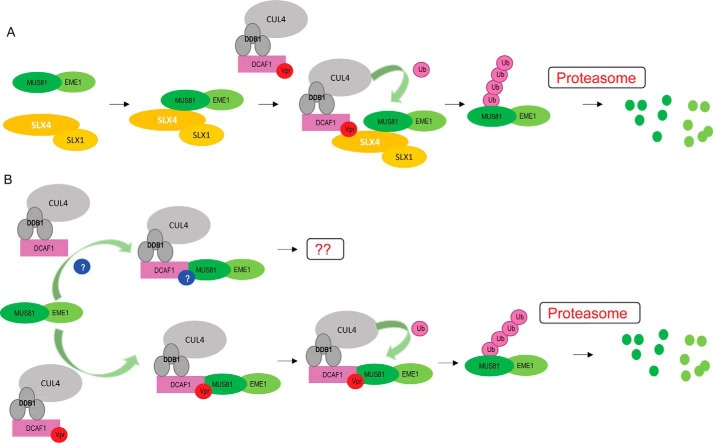

Despite being classified as an accessory factor, Vpr has multiple essential functions in the HIV-1 life cycle (4). Vpr primarily executes its biological activity by engaging DCAF1, a substrate receptor component of the CRL4 E3 ubiquitin ligase (58). Current and prevailing data support the hypothesis that Vpr recruits cellular targets to the CRL4-DCAF1 E3 ubiquitin ligase for proteasome-dependent degradation. Previous reports by Laguette et al. (54) suggested that SLX4com, comprising SLX4, SLX1, MUS81, and EME1, is a target of Vpr and is loaded onto the CRL4-DCAF1 E3 ubiquitin ligase. In particular, the recruitment of SLX4com to DCAF1 by Vpr was shown to enhance the structure-specific endonuclease activity of MUS81-EME1. Knockdown of any component of SLX4com abolished Vpr-induced G2 arrest. Furthermore, Vpr mutants, previously shown to be defective in G2 arrest, failed to form a stable complex with SLX4com and DCAF1 (54). These data implied that hyperactivity of MUS81-EME1, induced by Vpr, would produce an abnormal number of DNA breaks, turning on the DNA damage repair pathway, and ultimately leading to G2 arrest. A subsequent independent study further supported an interaction between SLX4com and CRL4-DCAF1 subverted by Vpr (55). Berger et al. (55) investigated the G2 arrest phenotypes of a panel of SIV Vpr proteins in human and simian grivet cells and established a correlation between G2 arrest and Vpr/SLX4com interaction. Interestingly, association of SLX4com with CRL4-DCAF1-Vpr was found to down-regulate MUS81. A possible model arising from these observations argues that Vpr interacts with SLX4com via the C-terminal region of SLX4 (Fig. 7A). Spatial arrangement of SLX4com allows poly-ubiquitination of MUS81, mediated by CRL4-DCAF1-Vpr, resulting in its proteasome-dependent degradation (54, 55). In this report, we provide evidence that MUS81-EME1 interacts with the CRL4-DCAF1 complex irrespective of Vpr and that the level of the endonuclease is regulated by Vpr binding to CRL4-DCAF1 and MUS81-EME1 (Fig. 7B). Co-immunoprecipitation experiments showed Vpr-independent interaction between DCAF1 and MUS81-EME1 (Fig. 4, D and E), whereas an in vitro pulldown experiment with purified recombinant proteins suggested a role for Vpr in mediating interaction between DCAF1 and MUS81-EME1 (Fig. 6, C and D). This suggests that an unknown cellular factor(s) may facilitate association of these proteins in cells. Surprisingly, Vpr-mediated down-regulation of MUS81/1EME1 does not require SLX4-SLX1.

FIGURE 7.

Two possible modes of Vpr-induced MUS81-EME1 down-regulation. A, SLX4-SLX1 mediates CRL4-DCAF1-Vpr and MUS81-EME1 interaction and promotes MUS81-EME1 down-regulation. B, MUS81-EME1 is a natural partner of CRL4-DCAF1, and Vpr promotes MUS81-EME1 poly-ubiquitination and down-regulation. An additional cellular factor(s) may bridge the interaction between MUS81-EME1 and CRL4-DCAF1 when Vpr is not present.

Down-regulation of MUS81-EME1 appears to be an evolutionarily conversed function of Vpr. We show that Vpr proteins isolated from multiple HIV-1 groups are capable of down-regulating MUS81-EME1. Furthermore, Vpr proteins from SIVcpz virus, isolated from two chimpanzee species, also induced MUS81-EME1 down-regulation. These SIV Vpr proteins are ancestors to those from the HIV-1 virus, generated by zoonosis (59, 60). These observations suggest that removal of the structure-selective endonuclease activity of MUS81-EME1 may be essential for the HIV-1 life cycle. However, our study suggests that this activity is not related to induction of cell cycle arrest at G2, one of the most well documented Vpr-dependent phenotypes. It is well established that the C terminus of Vpr is required for G2 arrest, arguing that the C terminus may bind and load cell cycle-related factors onto the CRL4-DCAF1 E3 ubiquitin ligase for proteasome-dependent degradation (10, 22, 25, 38–40). Several lines of evidence in this report argue that MUS81-EME1 is recruited to CRL4-DCAF1 by Vpr, but not via its C terminus. First, the Vpr variants that we tested for MUS81 down-regulation show significant diversity at the C terminus (Fig. 2F). Second, Vpr mutants, defective in G2 arrest still down-regulate MUS81-EME1 (Fig. 5). Consistent with our observation, another report showed that the same Vpr mutants, Q65R and R80A, caused MUS81 degradation (56). Further exploration is required to understand how Vpr mediates G2 arrest by interacting with SLX4com, and the independent biological pathway of MUS81 down-regulation, and the roles of these processes in the HIV-1 life cycle.

DCAF1 is an essential component in cell cycle progression and DNA replication, and its functions are mainly ascribed to its association with the CRL4 E3 ubiquitin ligase (58). Significantly, DCAF1 associates with chromatin during early S and G2 phases, and silencing of DCAF1 limits the cells progressing through the S phase (61). Therefore, it is not surprising to find that DCAF1 associates with several chromatin-bound factors including histone H2A, p53, HDAC1, and TET2/3, modulating transcriptional activation of specific genes (62–65). Therefore, it is tempting to speculate that DCAF1 regulates the cellular activity of MUS81-EME1 as well as SLX4com. It will be interesting to investigate how DCAF1 affects the biochemical activities of these structure-specific endonucleases, including resolution of Holliday junctions and repair of DNA interstrand cross-links. Understanding these processes may provide clues about the pathological advantage of MUS81 down-regulation by Vpr.

Experimental Procedures

Cloning and Plasmid Constructions

HIV-1 NL4-3 Vpr (VprHIV-1 NL4-3) was cloned into the pcDNA3.1 vector (Life Technologies, Inc.) with an HA tag. VprHIV-1 NL4-3 with R80A and Q65R mutants were prepared using the QuikChange mutagenesis kit (Agilent Technologies). Various Vpr clones from HIV-1 group (O, M, and N), SIVcpz PTT and PTS in pCG vector, were gifts from Dr. Jacek Skowronski at Case Western Reserve University. VprHIV-1 NL4-3 was cloned into pET41 vector (EMD Bioscience). FLAG-tagged SLX4 (residues 1430–1834), FLAG-tagged MUS81, and Myc-tagged EME1 or EME2 were cloned into pcDNA3.1 vector. HA-tagged DCAF1, FLAG-tagged DCAF1, and V5-tagged DDB1 were cloned into pcDNA3.1 vector. For Escherichia coli expression, MUS81 and EME1 were cloned into pET28 and pET21 vectors, respectively. All other clones were described previously (66).

Protein Purification and GST Pulldown

DCAF1 and GST fusion DDB1 were expressed in insect cell Sf21 (Life Technologies, Inc.). GST, GST-His6-Vpr, Vpr, and MUS81-EME1 were expressed in E. coli Rosetta 2 (DE3) or BL21, and proteins were purified as described previously (48, 66). Purified GST, GST-His6-Vpr, GST-DDB1/DCAF1, or GST-DDB1/DCAF1/Vpr were incubated with GST beads for 3 h with shaking in PBS buffer with 0.5% Nonidet P-40 (binding buffer). Excess unbound protein was washed by binding buffer. Purified MUS81-EME1 was incubated with these GST beads for 3 h with shaking in binding buffer. After washing three times, binding proteins were eluted by 20 mm glutathione in binding buffer.

Mammalian Cell Lines, Transfection, and Western Blotting

Human embryonic kidney cell lines (HEK293T from ATCC) were maintained in advanced DMEM, supplemented with 1% (v/v) 100× glutamine, and 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum at 37 °C, 5% CO2. Typically, 3 × 106 cells were plated on a 100-mm dish a day before transfection. Transfection was performed with a mixture of pCDNA plasmids encoding specific cDNAs using Lipofectamine 3000 (Life Technologies, Inc.), according to the manufacturer's protocol. Empty pcDNA vector plasmid was used as a balance. Cells were harvested 48 h post-transfection. After washing with PBS, cells were lysed with sonication in lysis buffer (50 mm Tris, 150 mm NaCl, 0.5% Nonidet P-40, pH 7.5) with Complete protease inhibitor mixture (Sigma). For protein analysis by Western blotting, some cell lysate was mixed with 1:5 (v/v) of 5× loading buffer. After centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 10 min, 20 μl of anti-FLAG M2 magnetic beads (Sigma) were added to the cell lysate supernatant for co-immunoprecipitation assay. The beads/cell lysate mixture were incubated with shaking at 4 °C for 5 h followed by washing with lysis buffer three times. Bound proteins were eluted with FLAG peptides at a concentration of 0.1 mg/ml and subjected to SDS-PAGE and Western blotting analysis with appropriate antibodies. The antibodies used in this study included anti-HA (Covance), anti-Myc (Covance), anti-FLAG (Abnova), anti-V5 (Sigma), anti-actin (Sigma), anti-DCAF1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-MUS81 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-EME1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-EME2 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-SLX4 (LSBio), anti-GST (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-Vpr (NIH AIDS Reagent), anti-goat IgG (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-rabbit IgG (Sigma), and anti-mouse IgG (Sigma).

Cycloheximide Chase Assay

Cells were transiently transfected with a mixture of pCDNA plasmids encoding MUS81 and empty vector or Vpr using Lipofectamine 3000. After 40 h post-transfection, cells were incubated with 20 μg/ml cycloheximide (Sigma) to block de novo protein synthesis. Cells were harvested after 1, 2, 4, 6, and 8 h of cycloheximide treatment (0 h for no cycloheximide). Cell lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by Western blotting with appropriate antibodies. Intensity of bands was quantified by ImageJ (67).

siRNA-mediated Protein Knockdown

siRNA targeting DCAF1 (5′-CCACAGAAUUUGUUGCGCA-3′, catalogue no. J-021119-10) and its non-targeting control siRNA (5′-UGGUUUACAUGUCGACUAA-3′, catalogue no. D-001810-01), On-TARGETplus human SLX4 siRNA SMARTpool (5′-UCAAACGGCACUCAGAUAA-3′, 5′-GCGGAGACUUUGUUGAAAU-3′, 5′-CAAGUGAGCCCGAGGAACA-3′, and 5′-UCAGAGCCGUCCCAAAUAA-3′, catalogue no. L-014895-00), and its Control On-TARGETplus non-targeting siRNA (5′-UAAGGCUAUGAAGAGAUAC-3′, 5′-AUGUAUUGGCCUGUAUUAG-3′, 5′-AUGAACGUGAAUUGCUCAA-3′, and 5′-UGGUUUACAUGUCGACUAA-3′, catalogue no. D-001206-14) were obtained from Dharmacon (GE Healthcare). HEK293T cells were transfected with siRNAs using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX according to the manufacturer's instructions. 24 h later, cells were transfected with pcDNA plasmids encoding specific cDNAs using Lipofectamine 3000 (Life Technologies, Inc.), according to the manufacturer's protocol. Total cell lysates were subjected to SDS-PAGE, and protein levels were analyzed by Western blotting with antibodies after 48 h.

Cell Cycle Assays

HEK293T cells seeded on 12-well plates were transfected with Vpr expressing pCDNA plasmids or empty vector. 48 h after transfection, the cells were treated with trypsin and washed twice with PBS. After fixation with 70% ethanol for 30 min, cells were washed twice with PBS and suspended in 1 ml of propidium iodide staining solution (0.1% Triton X-100, 10 μg/ml propidium iodide, and 100 μg/ml DNase-free RNase A in PBS). After 60 min of staining at room temperature, cells were sorted by flow cytometry (BD LSRII SORP). Data were analyzed using FlowJo software (Tree Star Inc., Ashland, OR).

Author Contributions

J. A. conceived the project. X. Z. and M. D. performed the experiment. X. Z. and J. A. analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Teresa Brosenitsch for editorial help and Dr. Jacek Skowronski for stimulating discussion and sharing reagents. We thank Jennifer Mehrens and Timothy J. Sturgeon for technical assistance. NIH AIDS reagent for anti-Vpr antibody from Dr. Jeffrey Kopp.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by the National Institutes of Health Grants P50 GM082251 and R01 GM116642 (to J. A.). The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

This article was selected as a Paper of the Week.

- Vpr

- viral protein R

- SIV

- simian immunodeficiency virus

- VprHIV-1 NL4-3

- Vpr isolated from HIV-1 NL4-3 clone

- VpxSIVmac

- Vpx isolated from SIV infecting macaque monkey

- Vpx

- viral protein X.

References

- 1. Kirchhoff F. (2010) Immune evasion and counteraction of restriction factors by HIV-1 and other primate lentiviruses. Cell Host Microbe 8, 55–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kogan M., and Rappaport J. (2011) HIV-1 accessory protein Vpr: relevance in the pathogenesis of HIV and potential for therapeutic intervention. Retrovirology 8, 25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tristem M., Marshall C., Karpas A., and Hill F. (1992) Evolution of the primate lentiviruses: evidence from vpx and vpr. EMBO J. 11, 3405–3412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ayinde D., Maudet C., Transy C., and Margottin-Goguet F. (2010) Limelight on two HIV/SIV accessory proteins in macrophage infection: is Vpx overshadowing Vpr? Retrovirology 7, 35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lim E. S., Fregoso O. I., McCoy C. O., Matsen F. A., Malik H. S., and Emerman M. (2012) The ability of primate lentiviruses to degrade the monocyte restriction factor SAMHD1 preceded the birth of the viral accessory protein Vpx. Cell Host Microbe 11, 194–204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Vodicka M. A., Koepp D. M., Silver P. A., and Emerman M. (1998) HIV-1 Vpr interacts with the nuclear transport pathway to promote macrophage infection. Genes Dev. 12, 175–185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Popov S., Rexach M., Ratner L., Blobel G., and Bukrinsky M. (1998) Viral protein R regulates docking of the HIV-1 preintegration complex to the nuclear pore complex. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 13347–13352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Popov S., Rexach M., Zybarth G., Reiling N., Lee M. A., Ratner L., Lane C. M., Moore M. S., Blobel G., and Bukrinsky M. (1998) Viral protein R regulates nuclear import of the HIV-1 pre-integration complex. EMBO J. 17, 909–917 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Le Rouzic E., Mousnier A., Rustum C., Stutz F., Hallberg E., Dargemont C., and Benichou S. (2002) Docking of HIV-1 Vpr to the nuclear envelope is mediated by the interaction with the nucleoporin hCG1. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 45091–45098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Felzien L. K., Woffendin C., Hottiger M. O., Subbramanian R. A., Cohen E. A., and Nabel G. J. (1998) HIV transcriptional activation by the accessory protein, VPR, is mediated by the p300 co-activator. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 5281–5286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sawaya B. E., Khalili K., Rappaport J., Serio D., Chen W., Srinivasan A., and Amini S. (1999) Suppression of HIV-1 transcription and replication by a Vpr mutant. Gene Ther. 6, 947–950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Varin A., Decrion A. Z., Sabbah E., Quivy V., Sire J., Van Lint C., Roques B. P., Aggarwal B. B., and Herbein G. (2005) Synthetic Vpr protein activates activator protein-1, c-Jun N-terminal kinase, and NF-κB and stimulates HIV-1 transcription in promonocytic cells and primary macrophages. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 42557–42567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Levy D. N., Fernandes L. S., Williams W. V., and Weiner D. B. (1993) Induction of cell differentiation by human immunodeficiency virus 1 vpr. Cell 72, 541–550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Muthumani K., Hwang D. S., Desai B. M., Zhang D., Dayes N., Green D. R., and Weiner D. B. (2002) HIV-1 Vpr induces apoptosis through caspase 9 in T cells and peripheral blood mononuclear cells. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 37820–37831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Muthumani K., Choo A. Y., Hwang D. S., Chattergoon M. A., Dayes N. N., Zhang D., Lee M. D., Duvvuri U., and Weiner D. B. (2003) Mechanism of HIV-1 viral protein R-induced apoptosis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 304, 583–592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bouzar A. B., Villet S., Morin T., Rea A., Genestier L., Guiguen F., Garnier C., Mornex J. F., Narayan O., and Chebloune Y. (2004) Simian immunodeficiency virus Vpr/Vpx proteins kill bystander noninfected CD4+ T-lymphocytes by induction of apoptosis. Virology 326, 47–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Arokium H., Kamata M., and Chen I. (2009) Virion-associated Vpr of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 triggers activation of apoptotic events and enhances fas-induced apoptosis in human T cells. J. Virol. 83, 11283–11297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Goh W. C., Rogel M. E., Kinsey C. M., Michael S. F., Fultz P. N., Nowak M. A., Hahn B. H., and Emerman M. (1998) HIV-1 Vpr increases viral expression by manipulation of the cell cycle: a mechanism for selection of Vpr in vivo. Nat. Med. 4, 65–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gummuluru S., and Emerman M. (1999) Cell cycle- and Vpr-mediated regulation of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 expression in primary and transformed T-cell lines. J. Virol. 73, 5422–5430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Roshal M., Kim B., Zhu Y., Nghiem P., and Planelles V. (2003) Activation of the ATR-mediated DNA damage response by the HIV-1 viral protein R. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 25879–25886 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lai M., Zimmerman E. S., Planelles V., and Chen J. (2005) Activation of the ATR pathway by human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vpr involves its direct binding to chromatin in vivo. J. Virol. 79, 15443–15451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Belzile J. P., Duisit G., Rougeau N., Mercier J., Finzi A., and Cohen E. A. (2007) HIV-1 Vpr-mediated G2 arrest involves the DDB1-CUL4AVPRBP E3 ubiquitin ligase. PLoS Pathog. 3, e85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tan L., Ehrlich E., and Yu X. F. (2007) DDB1 and Cul4A are required for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vpr-induced G2 arrest. J. Virol. 81, 10822–10830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hrecka K., Gierszewska M., Srivastava S., Kozaczkiewicz L., Swanson S. K., Florens L., Washburn M. P., and Skowronski J. (2007) Lentiviral Vpr usurps Cul4-DDB1[VprBP] E3 ubiquitin ligase to modulate cell cycle. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 11778–11783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. DeHart J. L., Zimmerman E. S., Ardon O., Monteiro-Filho C. M., Argañaraz E. R., and Planelles V. (2007) HIV-1 Vpr activates the G2 checkpoint through manipulation of the ubiquitin proteasome system. Virol. J. 4, 57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Le Rouzic E., Belaïdouni N., Estrabaud E., Morel M., Rain J. C., Transy C., and Margottin-Goguet F. (2007) HIV1 Vpr arrests the cell cycle by recruiting DCAF1/VprBP, a receptor of the Cul4-DDB1 ubiquitin ligase. Cell Cycle 6, 182–188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wen X., Duus K. M., Friedrich T. D., and de Noronha C. M. (2007) The HIV1 protein Vpr acts to promote G2 cell cycle arrest by engaging a DDB1 and Cullin4A-containing ubiquitin ligase complex using VprBP/DCAF1 as an adaptor. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 27046–27057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Le Rouzic E., Morel M., Ayinde D., Belaïdouni N., Letienne J., Transy C., and Margottin-Goguet F. (2008) Assembly with the Cul4A-DDB1DCAF1 ubiquitin ligase protects HIV-1 Vpr from proteasomal degradation. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 21686–21692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Transy C., and Margottin-Goguet F. (2009) HIV1 Vpr arrests the cell cycle by recruiting DCAF1/VprBP, a receptor of the Cul4-DDB1 ubiquitin ligase. Cell Cycle 8, 2489–2490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Belzile J. P., Richard J., Rougeau N., Xiao Y., and Cohen E. A. (2010) HIV-1 Vpr induces the K48-linked polyubiquitination and proteasomal degradation of target cellular proteins to activate ATR and promote G2 arrest. J. Virol. 84, 3320–3330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Jin J., Arias E. E., Chen J., Harper J. W., and Walter J. C. (2006) A family of diverse Cul4-Ddb1-interacting proteins includes Cdt2, which is required for S phase destruction of the replication factor Cdt1. Mol. Cell 23, 709–721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. He Y. J., McCall C. M., Hu J., Zeng Y., and Xiong Y. (2006) DDB1 functions as a linker to recruit receptor WD40 proteins to CUL4-ROC1 ubiquitin ligases. Genes Dev. 20, 2949–2954 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Higa L. A., Wu M., Ye T., Kobayashi R., Sun H., and Zhang H. (2006) CUL4-DDB1 ubiquitin ligase interacts with multiple WD40-repeat proteins and regulates histone methylation. Nat. Cell Biol. 8, 1277–1283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Romani B., and Cohen E. A. (2012) Lentivirus Vpr and Vpx accessory proteins usurp the cullin4-DDB1 (DCAF1) E3 ubiquitin ligase. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2, 755–763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Blondot M. L., Dragin L., Lahouassa H., and Margottin-Goguet F. (2014) How SLX4 cuts through the mystery of HIV-1 Vpr-mediated cell cycle arrest. Retrovirology 11, 117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Cassiday P. A., DePaula-Silva A. B., Chumley J., Ward J., Barker E., and Planelles V. (2015) Understanding the molecular manipulation of DCAF1 by the lentiviral accessory proteins Vpr and Vpx. Virology 476, 19–25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Jacquot G., Le Rouzic E., Maidou-Peindara P., Maizy M., Lefrère J. J., Daneluzzi V., Monteiro-Filho C. M., Hong D., Planelles V., Morand-Joubert L., and Benichou S. (2009) Characterization of the molecular determinants of primary HIV-1 Vpr proteins: impact of the Q65R and R77Q substitutions on Vpr functions. PLoS ONE 4, e7514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Di Marzio P., Choe S., Ebright M., Knoblauch R., and Landau N. R. (1995) Mutational analysis of cell cycle arrest, nuclear localization and virion packaging of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vpr. J. Virol. 69, 7909–7916 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Yao X. J., Mouland A. J., Subbramanian R. A., Forget J., Rougeau N., Bergeron D., and Cohen E. A. (1998) Vpr stimulates viral expression and induces cell killing in human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected dividing Jurkat T cells. J. Virol. 72, 4686–4693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Zhou Y., Lu Y., and Ratner L. (1998) Arginine residues in the C terminus of HIV-1 Vpr are important for nuclear localization and cell cycle arrest. Virology 242, 414–424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ciccia A., McDonald N., and West S. C. (2008) Structural and functional relationships of the XPF/MUS81 family of proteins. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 77, 259–287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Matos J., and West S. C. (2014) Holliday junction resolution: regulation in space and time. DNA Repair 19, 176–181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Amangyeld T., Shin Y. K., Lee M., Kwon B., and Seo Y. S. (2014) Human MUS81-EME2 can cleave a variety of DNA structures including intact Holliday junction and nicked duplex. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, 5846–5862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Pepe A., and West S. C. (2014) MUS81-EME2 promotes replication fork restart. Cell Rep. 7, 1048–1055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Gaillard P. H., Noguchi E., Shanahan P., and Russell P. (2003) The endogenous Mus81-Eme1 complex resolves Holliday junctions by a nick and counternick mechanism. Mol. Cell 12, 747–759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Hanada K., Budzowska M., Modesti M., Maas A., Wyman C., Essers J., and Kanaar R. (2006) The structure-specific endonuclease Mus81-Eme1 promotes conversion of interstrand DNA cross-links into double-strands breaks. EMBO J. 25, 4921–4932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Pepe A., and West S. C. (2014) Substrate specificity of the MUS81-EME2 structure selective endonuclease. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, 3833–3845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Ciccia A., Constantinou A., and West S. C. (2003) Identification and characterization of the human mus81-eme1 endonuclease. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 25172–25178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Dendouga N., Gao H., Moechars D., Janicot M., Vialard J., and McGowan C. H. (2005) Disruption of murine Mus81 increases genomic instability and DNA damage sensitivity but does not promote tumorigenesis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25, 7569–7579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Hiyama T., Katsura M., Yoshihara T., Ishida M., Kinomura A., Tonda T., Asahara T., and Miyagawa K. (2006) Haploinsufficiency of the Mus81-Eme1 endonuclease activates the intra-S-phase and G2/M checkpoints and promotes rereplication in human cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 34, 880–892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Wyatt H. D., Sarbajna S., Matos J., and West S. C. (2013) Coordinated actions of SLX1-SLX4 and MUS81-EME1 for Holliday junction resolution in human cells. Mol. Cell 52, 234–247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Castor D., Nair N., Déclais A. C., Lachaud C., Toth R., Macartney T. J., Lilley D. M., Arthur J. S., and Rouse J. (2013) Cooperative control of holliday junction resolution and DNA repair by the SLX1 and MUS81-EME1 nucleases. Mol. Cell 52, 221–233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Nair N., Castor D., Macartney T., and Rouse J. (2014) Identification and characterization of MUS81 point mutations that abolish interaction with the SLX4 scaffold protein. DNA Repair 24, 131–137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Laguette N., Brégnard C., Hue P., Basbous J., Yatim A., Larroque M., Kirchhoff F., Constantinou A., Sobhian B., and Benkirane M. (2014) Premature activation of the SLX4 complex by Vpr promotes G2/M arrest and escape from innate immune sensing. Cell 156, 134–145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Berger G., Lawrence M., Hué S., and Neil S. J. (2015) G2/M cell cycle arrest correlates with primate lentiviral Vpr interaction with the SLX4 complex. J. Virol. 89, 230–240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. DePaula-Silva A. B., Cassiday P. A., Chumley J., Bosque A., Monteiro-Filho C. M., Mahon C. S., Cone K. R., Krogan N., Elde N. C., and Planelles V. (2015) Determinants for degradation of SAMHD1, Mus81 and induction of G2 arrest in HIV-1 Vpr and SIVagm Vpr. Virology 477, 10–17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Fekairi S., Scaglione S., Chahwan C., Taylor E. R., Tissier A., Coulon S., Dong M. Q., Ruse C., Yates J. R. 3rd, Russell P., Fuchs R. P., McGowan C. H., and Gaillard P. H. (2009) Human SLX4 is a Holliday junction resolvase subunit that binds multiple DNA repair/recombination endonucleases. Cell 138, 78–89 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Nakagawa T., Mondal K., and Swanson P. C. (2013) VprBP (DCAF1): a promiscuous substrate recognition subunit that incorporates into both RING-family CRL4 and HECT-family EDD/UBR5 E3 ubiquitin ligases. BMC Mol. Biol. 14, 22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Bailes E., Gao F., Bibollet-Ruche F., Courgnaud V., Peeters M., Marx P. A., Hahn B. H., and Sharp P. M. (2003) Hybrid origin of SIV in chimpanzees. Science 300, 1713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Gao F., Bailes E., Robertson D. L., Chen Y., Rodenburg C. M., Michael S. F., Cummins L. B., Arthur L. O., Peeters M., Shaw G. M., Sharp P. M., and Hahn B. H. (1999) Origin of HIV-1 in the chimpanzee Pan troglodytes. Nature 397, 436–441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. McCall C. M., Miliani de Marval P. L., Chastain P. D. 2nd, Jackson S. C., He Y. J., Kotake Y., Cook J. G., and Xiong Y. (2008) Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vpr-binding protein VprBP, a WD40 protein associated with the DDB1-CUL4 E3 ubiquitin ligase, is essential for DNA replication and embryonic development. Mol. Cell. Biol. 28, 5621–5633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Belzile J. P., Abrahamyan L. G., Gérard F. C., Rougeau N., and Cohen E. A. (2010) Formation of mobile chromatin-associated nuclear foci containing HIV-1 Vpr and VPRBP is critical for the induction of G2 cell cycle arrest. PLoS Pathog. 6, e1001080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Kim K., Heo K., Choi J., Jackson S., Kim H., Xiong Y., and An W. (2012) Vpr-binding protein antagonizes p53-mediated transcription via direct interaction with H3 tail. Mol. Cell. Biol. 32, 783–796 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Kim K., Kim J. M., Kim J. S., Choi J., Lee Y. S., Neamati N., Song J. S., Heo K., and An W. (2013) VprBP has intrinsic kinase activity targeting histone H2A and represses gene transcription. Mol. Cell 52, 459–467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Nakagawa T., Lv L., Nakagawa M., Yu Y., Yu C., D'Alessio A. C., Nakayama K., Fan H. Y., Chen X., and Xiong Y. (2015) CRL4(VprBP) E3 ligase promotes monoubiquitylation and chromatin binding of TET dioxygenases. Mol. Cell 57, 247–260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. DeLucia M., Mehrens J., Wu Y., and Ahn J. (2013) HIV-2 and SIVmac accessory virulence factor Vpx down-regulates SAMHD1 enzyme catalysis prior to proteasome-dependent degradation. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 19116–19126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Rueden C. T., and Eliceiri K. W. (2007) Visualization approaches for multidimensional biological image data. BioTechniques 43, 31, 33–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. McWilliam H., Li W., Uludag M., Squizzato S., Park Y. M., Buso N., Cowley A. P., and Lopez R. (2013) Analysis Tool Web Services from the EMBL-EBI. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, W597–W600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Robert X., and Gouet P. (2014) Deciphering key features in protein structures with the new ENDscript server. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, W320–W324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]