Abstract

The protein kinase casein kinase 2 (CK2) is a pleiotropic and constitutively active kinase that plays crucial roles in cellular proliferation and survival. Overexpression of CK2, particularly the α catalytic subunit (CK2α, CSNK2A1), has been implicated in a wide variety of cancers and is associated with poorer survival and resistance to both conventional and targeted anticancer therapies. Here, we found that CK2α protein is elevated in melanoma cell lines compared with normal human melanocytes. We then tested the involvement of CK2α in drug resistance to Food and Drug Administration-approved single agent targeted therapies for melanoma. In BRAF mutant melanoma cells, ectopic CK2α decreased sensitivity to vemurafenib (BRAF inhibitor), dabrafenib (BRAF inhibitor), and trametinib (MEK inhibitor) by a mechanism distinct from that of mutant NRAS. Conversely, knockdown of CK2α sensitized cells to inhibitor treatment. CK2α-mediated RAF-MEK kinase inhibitor resistance was tightly linked to its maintenance of ERK phosphorylation. We found that CK2α post-translationally regulates the ERK-specific phosphatase dual specificity phosphatase 6 (DUSP6) in a kinase dependent-manner, decreasing its abundance. However, we unexpectedly showed, by using a kinase-inactive mutant of CK2α, that RAF-MEK inhibitor resistance did not rely on CK2α kinase catalytic function, and both wild-type and kinase-inactive CK2α maintained ERK phosphorylation upon inhibition of BRAF or MEK. That both wild-type and kinase-inactive CK2α bound equally well to the RAF-MEK-ERK scaffold kinase suppressor of Ras 1 (KSR1) suggested that CK2α increases KSR facilitation of ERK phosphorylation. Accordingly, CK2α did not cause resistance to direct inhibition of ERK by the ERK1/2-selective inhibitor SCH772984. Our findings support a kinase-independent scaffolding function of CK2α that promotes resistance to RAF- and MEK-targeted therapies.

Keywords: drug resistance, dual specificity phosphoprotein phosphatase, extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK), melanoma, Ras protein, CK2, kinase suppressor of RAS 1 (KSR1)

Introduction

The protein kinase casein kinase 2 or II (CK2)2 is a highly conserved, ubiquitously expressed, pleiotropic, and constitutively active serine/threonine kinase that has crucial roles in cell survival, proliferation, and differentiation (2–4). The CK2 holoenzyme consists of two regulatory (β) and two catalytic (α or α′) subunits, the latter of which can also function independently of the tetramer (5). Although CK2 itself does not appear to be a proto-oncogene, its up-regulation has been shown to promote growth and prevent apoptosis, both of which promote cancer (4). Indeed, overexpression of CK2 at the transcript and/or protein level has been observed in many cancers (6), including multiple myeloma (7), chronic lymphocytic leukemia (8), breast cancer (9), colorectal cancer (10), liver cancer (11), etc. and is correlated with poorer patient survival (6, 10, 12). Similarly, CK2 exhibited 2.5-fold higher catalytic activity in metastatic melanoma than in dermal nevi (13).

In addition to its roles in tumor growth and progression, CK2 also promotes drug resistance to both conventional and targeted therapeutics. For example, pharmacological inhibition of CK2 kinase activity reverted multidrug resistance of a human T lymphoblastoid cell line (14) at least in part by down-regulating P-glycoprotein activity. In addition, siRNA-mediated knockdown of CK2 catalytic subunits enhanced chemosensitivity to gemcitabine in human pancreatic cancer cells (15). In cells depleted of CK2α, gemcitabine induced MKK4/JNK signaling, resulting in cell death (15). Furthermore, CK2 displayed elevated protein expression and activity in chronic myeloid leukemia cells that are resistant to the small molecule kinase inhibitor imatinib (16). Either reduction of CK2α expression or pharmacological inhibition of CK2α kinase activity restored imatinib sensitivity, possibly through suppressing Akt activity (16). However, the role of CK2α in drug resistance, particularly to targeted therapeutics, has remained underexplored.

Inhibitors of BRAF and MEK, members of the RAF-MEK-ERK kinase cascade, have achieved remarkable overall response rates in advanced melanomas harboring BRAF Val-600 mutations, but a significant proportion of patients is intrinsically resistant to such therapies, and those who respond almost inevitably develop resistance over a matter of months (17). Considerable efforts have been invested in identifying resistance mechanisms of BRAF mutant melanomas to BRAF inhibition, and some have demonstrated clinical relevance (18–21). In a recent whole-kinome siRNA screen for kinases that could induce resistance to ERK kinase inhibitors in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma cells, we identified CK2α as a synthetic lethal partner of ERK inhibition (22). We postulated that kinase inhibitor resistance mechanisms can be shared by diseases that show hyperactivity of the same pathway. Given that the RAF-MEK-ERK pathway is strongly activated in both pancreatic cancer and melanoma, we sought to determine whether CK2 also plays a role in resistance to inhibition of this pathway in melanoma.

In the present study, we found that CK2α overexpression was sufficient to drive resistance to both BRAF and MEK inhibitors in BRAF mutant melanoma cells. Conversely, depletion of CK2α increased sensitivity to the BRAF inhibitor vemurafenib. Consistent with these results, CK2α sustained ERK phosphorylation under conditions of pathway inhibition. Although we found that CK2 negatively regulated expression of the ERK-specific phosphatase dual specificity phosphatase 6 (DUSP6) in a kinase-dependent manner, the maintenance of ERK phosphorylation was not due to these decreased levels of DUSP6. Instead, we found that CK2α-mediated maintenance of ERK phosphorylation and drug resistance were kinase-independent. The ability of both wild-type and kinase-inactive CK2α to bind to the key RAF-MEK-ERK pathway scaffold protein kinase suppressor of Ras 1 (KSR1), which is required for optimal ERK phosphorylation and activation, supports a kinase-independent scaffolding role for CK2α in facilitating optimal ERK signaling under conditions of pathway inhibition. That CK2α overexpression did not cause resistance to a direct ERK inhibitor is further evidence that ERK inhibition may overcome resistance mechanisms that shorten the effectiveness of blocking upstream kinases in the RAF-MEK-ERK pathway.

Results

CK2α Expression Is Up-regulated in a Subset of Melanomas

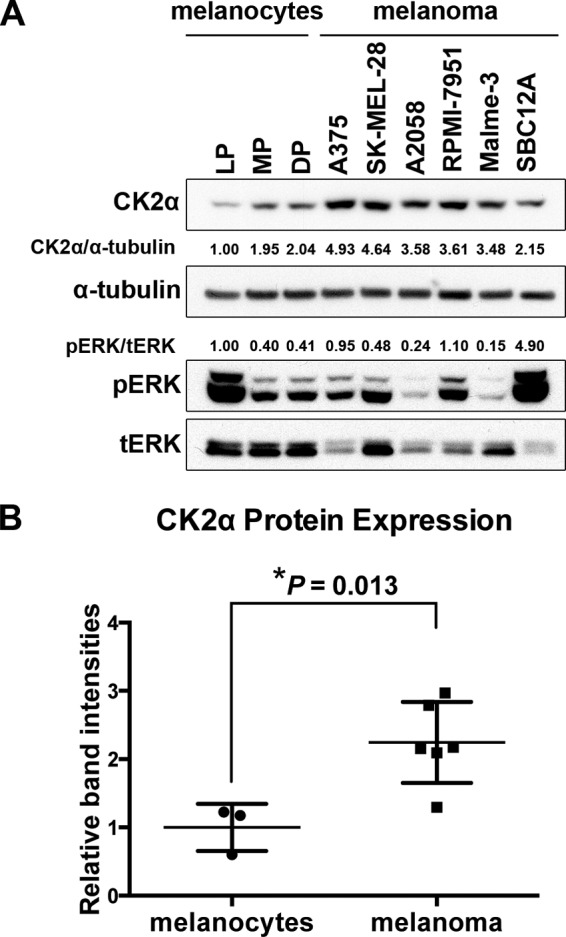

To examine the expression of CK2α in melanoma, we first surveyed the Cancer Genome Atlas skin cutaneous melanoma data set for CK2α mRNA expression through cBioPortal (40). We found that the CK2α transcript is up-regulated in a subset of those tumors (15% of 278 samples) and that 90% of that subset also harbor mutations in BRAF, NRAS, and/or NF1 that lead to hyperactivation of ERK. Next, we measured CK2α protein expression in a panel of neonatal human epidermal melanocytes, lightly pigmented, moderately pigmented, and darkly pigmented donors and melanoma cell lines (five BRAF mutants (A375, SK-MEL-28, A2058, RPMI-7951, and Malme-3) and one NRAS mutant (SBC12A)) (Fig. 1A). Melanoma cell lines had higher levels of CK2α protein expression compared with melanocytes (Fig. 1B; p = 0.013). In contrast, basal phosphorylated ERK (pERK) levels were quite variable among the lines and were not predicted either by malignancy state (p = 0.5384) or by CK2α levels (R2 = 0.06130) (Fig. 1A), consistent with our previous findings (see Fig. 1 in Shields et al. (23)).

FIGURE 1.

CK2α protein expression is elevated in melanoma cell lines compared with melanocytes. A, cell lysates from a panel consisting of three types of neonatal epidermal melanocytes from lightly pigmented (LP), moderately pigmented (MP), and darkly pigmented (DP) donors and five BRAF and one NRAS mutant melanoma cell lines were probed for CK2α protein by Western blotting with anti-CK2α antibody. α-Tubulin was used as a loading control. Normalized expression of CK2α/α-tubulin is shown. Phosphorylation of ERK was measured and normalized to total ERK (tERK). B, statistical analysis of normalized CK2α expression (*, p = 0.013). Error bars represent S.E.

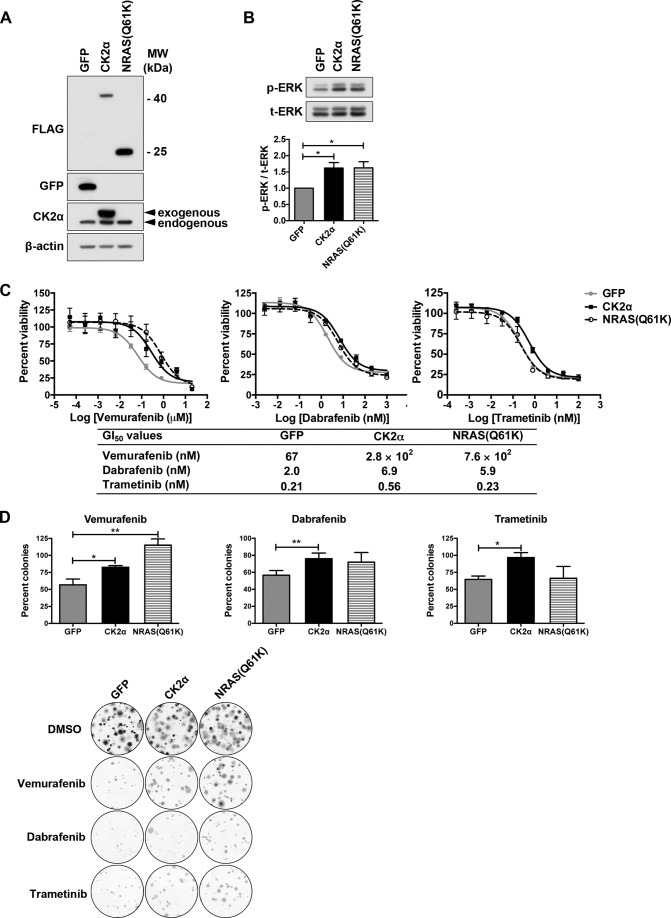

CK2α Promotes Resistance to Inhibitors of BRAF and MEK in BRAF Mutant Melanoma Cells

We recently used a whole-kinome siRNA screen to search for mechanisms of resistance to ERK inhibition in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma cell, and found that CK2α was one of the hits identified (22). To test whether CK2α promotes resistance to approved single agent therapies targeting the RAF-MEK-ERK pathway in melanoma cells with hyperactivation of this pathway, we first stably expressed FLAG-tagged wild-type CK2α in A375 melanoma cells (Fig. 2A). These cells possess a homozygous BRAF(V600E) mutation and are sensitive to both BRAFi and MEKi. We then assessed sensitivity to growth inhibition by multiple inhibitors of the pathway, including mutant BRAF-selective inhibitors vemurafenib and dabrafenib and MEK1/2-selective inhibitor trametinib. Oncogenically activated (mutant) NRAS has been identified in patients with BRAF mutant melanomas as one mechanism of resistance to BRAF but not MEK inhibition (24). Therefore, we stably expressed FLAG-tagged mutant NRAS(Q61K) (Fig. 2A) as a positive control. Expression of CK2α or NRAS(Q61K) led to an ∼1.62-fold increase in basal ERK phosphorylation (Fig. 2B). But, as expected, mutant NRAS promoted resistance to both BRAF inhibitors vemurafenib and dabrafenib as evidenced by increased values for 50% growth inhibition (GI50) of 11.4- and 2.97-fold, respectively, compared with the GFP negative control (Fig. 2D). In contrast, mutant NRAS did not increase the GI50 (1.1-fold change) for the MEKi trametinib, consistent with findings that BRAF mutant melanomas with secondary NRAS mutations still remain sensitive to MEK inhibition (24). Notably, expression of CK2α increased the GI50 for vemurafenib, dabrafenib, and trametinib by 4.13-, 3.52-, and 2.63-fold, respectively, indicating reduced sensitivity to all three inhibitors (Fig. 2C). A summary of all GI50 values are provided in a table in Fig. 2C, lower panel. Expression of CK2α also produced resistance to vemurafenib in another BRAF mutant melanoma cell line, SK-MEL-28 (data not shown). To further evaluate the effect of CK2α expression on responses to the above mentioned inhibitors, we performed clonogenic cell survival assays, which assess the ability of individual cells to form colonies, a property that differs between tumor cells and their normal counterparts and that is distinct from the proliferation of an overall cell population as measured by 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide assay. Consistent with the increased GI50 values, CK2α enhanced the clonogenic survival of A375 cells as measured by percent colony numbers in the presence of each inhibitor compared with DMSO vehicle control (Fig. 2D). In contrast to CK2α, NRAS(Q61K) significantly enhanced clonogenic survival only in response to vemurafenib. The modest enhancement in clonogenic survival in response to dabrafenib did not reach statistical significance. Together, these results indicate that CK2α overexpression but not NRAS mutation is sufficient to induce resistance to both BRAF and MEK inhibition, which implies a CK2α-mediated resistance mechanism distinct from that mediated by mutant NRAS.

FIGURE 2.

Ectopic CK2α promotes resistance to inhibitors of BRAF and MEK. A, A375 cells were stably infected with lentiviral vectors to ectopically express GFP negative control or FLAG-tagged CK2α or NRAS(Q61K), and cell lysates were subjected to Western blotting using anti-FLAG, anti-GFP, and anti-CK2α antibodies. β-Actin served as a loading control. B, expression of CK2α or NRAS(Q61K) increases the basal level of ERK phosphorylation in A375 cells by 1.62-fold as determined by Western blotting using anti-phospho-ERK(Thr-202/Tyr-204) antibody and normalized to total ERK (t-ERK) (n = 5). C, CK2α increases GI50 for BRAFi vemurafenib, BRAFi dabrafenib, and MEKi trametinib. 3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide assays were performed after 72 h of treatment with nine different doses of inhibitors, and dose-response curves were generated by GraphPad Prism v5.0c. Results are presented as means ± S.E. (n = 6). A summary of all GI50 values is shown in the table below. D, CK2α enhances clonogenic survival of inhibitor-treated A375 cells. Cells as in the previous panels were grown for 2 weeks on plastic as single colonies in the presence of vemurafenib (1 μm), dabrafenib (100 nm), trametinib (1 nm), or DMSO vehicle control. Shown are the percentage of colonies formed in the presence of each inhibitor relative to the vehicle control. Results are presented as means ± S.E. **, p < 0.01; *, p < 0.05 (n = 3). Crystal violet-stained images of colonies are shown in the lower panel. Error bars represent S.E.

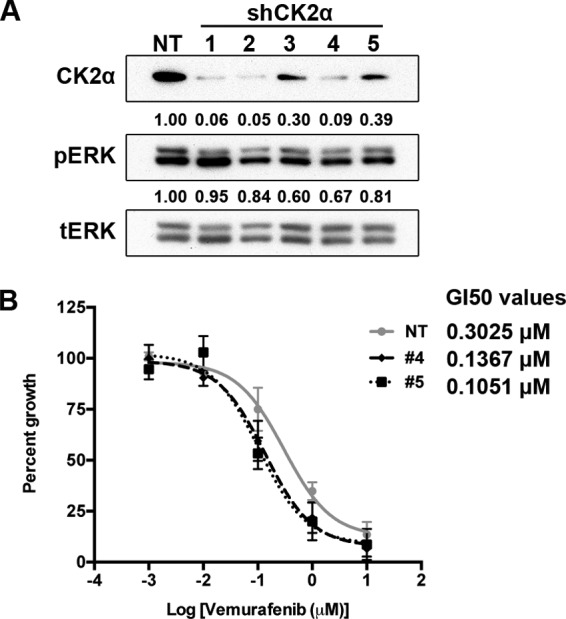

CK2α Depletion Sensitizes Melanoma Cells to BRAF Inhibition

Given that CK2α overexpression was sufficient to drive resistance, we asked whether, conversely, depletion of CK2α would enhance sensitivity to pathway inhibition. We used a set of five shRNAs (1–5) to knock down CK2α in A375 cells. Consistent with the mild increase in basal ERK phosphorylation when CK2α was overexpressed (Fig. 2B), we found that ERK phosphorylation was mildly impaired upon CK2α knockdown (data not shown). Complete knockdown of CK2α was incompatible with cell survival (data not shown). Therefore, to obtain cells for subsequent experimentation, we utilized shRNAs 4 and 5, which yielded ∼60% knockdown and sufficient viability (Fig. 3A). Even this incomplete depletion of CK2α expression resulted in decreased GI50 for vemurafenib (55 and 65% decrease for shRNAs 4 and 5, respectively; Fig. 3B). This result indicates that CK2α is necessary for resistance to BRAF inhibition.

FIGURE 3.

Suppression of endogenous CK2α increases sensitivity to the BRAF inhibitor vemurafenib. A, endogenous CK2α was suppressed in A375 cells by using five different shRNA sequences, and the degree of knockdown was assessed by Western blotting using anti-CK2 antibody. β-Actin served as a loading control. The percentage of knockdown achieved by each shRNA directed against CK2α, normalized to the non-targeting (NT) shRNA, is indicated below each lane. tERK, total ERK. B, knockdown of ∼60% of endogenous CK2α (A) is sufficient to decrease the GI50 for vemurafenib. GI50 curves for A375 cells infected with either non-targeting shRNA or shRNA 4 (black dashed line) or shRNA 5 (black dotted line) are shown. Results are presented as means ± S.E. (n = 3). Error bars represent S.E.

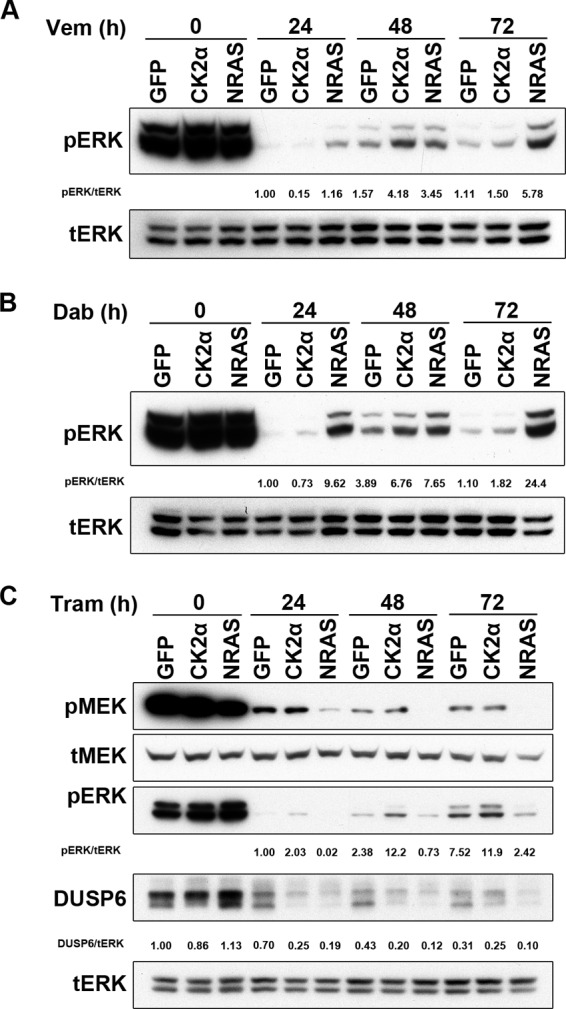

CK2α Sustains ERK Phosphorylation under Conditions of RAF-MEK-ERK Pathway Inhibition

Previous studies have identified multiple mechanisms of resistance to BRAF inhibition, the majority of which are characterized by ERK reactivation (25). Given that CK2α and mutant NRAS both promote BRAFi resistance, we hypothesized that they are both capable of facilitating ERK reactivation following inhibition of BRAF and/or MEK. As anticipated, mutant NRAS induced strong ERK reactivation upon inhibition of BRAF with either vemurafenib or dabrafenib (Fig. 4, A and B). CK2α also facilitated ERK rebound although not as strongly as NRAS(Q61K). Consistent with their trametinib resistance profiles, NRAS(Q61K) failed to reactivate ERK in the presence of trametinib, whereas CK2α did sustain ERK phosphorylation (Fig. 4C). The maintenance of ERK phosphorylation by CK2α suggested either maintained upstream activation or suppressed deactivation mechanisms. MEK is the only known direct activator of ERK (26), and phosphorylation of MEK at Ser-217 and Ser-221 is indicative of MEK activation. DUSP6/mitogen-activated kinase kinase phosphatase 3 is a key ERK-specific phosphatase that reverses MEK phosphorylation at the TEY motif of ERK (27). Therefore, we assessed the status of both MEK activation and DUSP6 expression by Western blotting. We found that MEK phosphorylation did not change in parallel with ERK phosphorylation, indicating that it is not the basis for maintained ERK activity (Fig. 4C). Intriguingly, DUSP6 expression was also strongly reduced in CK2α-overexpressing cells even without inhibitor treatment (Fig. 4C). Based on this finding, we initially hypothesized that down-regulation of DUSP6 contributed to the sustained ERK phosphorylation. However, we first needed to confirm whether CK2α truly regulates DUSP6 expression.

FIGURE 4.

Overexpressed CK2α accelerates ERK rebound or sustains ERK phosphorylation in response to RAF-MEK-ERK pathway inhibition. pERK was evaluated by Western blotting analysis of lysates from A375 cells ectopically expressing GFP, CK2α, or NRAS(Q61K) treated for 24, 48, or 72h with vemurafenib (Vem) (BRAFi; 1 μm) (A), dabrafenib (Dab) (BRAFi; 100 nm) (B), or trametinib (Tram) (MEKi; 1 nm) (C). Total ERK1/2 (tERK) served as a loading control. MEKi (trametinib)-treated cell lysates were additionally immunoblotted for phospho-MEK1/2 (pMEK) and for the ERK-specific phosphatase DUSP6. Densitometry values for pERK/total ERK are shown for each panel.

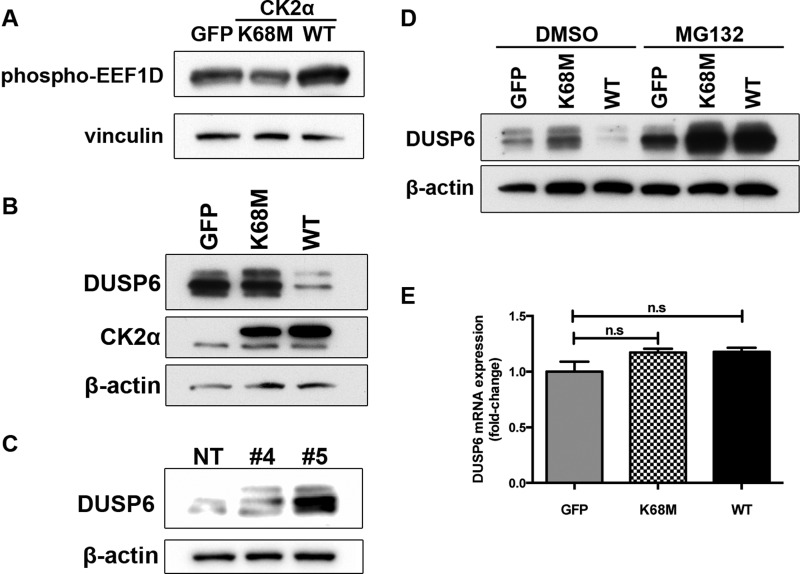

CK2α Regulates DUSP6 Protein Levels in a Kinase-dependent Manner

CK2α has been reported to directly phosphorylate DUSP6 at multiple sites in vitro, the consequences of which are largely unknown (28). To control for CK2α kinase activity, we generated a kinase-inactive mutant of CK2α (29) and measured DUSP6 protein levels upon ectopic expression of either kinase-inactive (K68M) or wild-type (WT) CK2α. As expected, CK2α(WT) was constitutively active, and cells overexpressing this form of CK2α exhibited elevated basal phosphorylation of EEF1D (Fig. 5A), a validated marker of CK2 activity (30). In contrast, cells expressing kinase-inactive CK2α(K68M) exhibited mildly reduced levels of EEF1D phosphorylation (Fig. 5A), suggesting a weak dominant-negative effect. Interestingly, CK2α(WT) drastically reduced DUSP6 abundance, whereas K68M did not have an effect (Fig. 5B), indicating that the decrease in DUSP6 protein is likely due to CK2α-mediated phosphorylation. Conversely, shRNA-mediated knockdown of endogenous CK2α enhanced DUSP6 protein levels (Fig. 5C). To determine whether the reduction in DUSP6 was the result of accelerated degradation or suppressed transcription, we first used MG132 to block proteasome-mediated protein degradation. Six hours after MG132 treatment, DUSP6 abundance was fully rescued (Fig. 5D). We also examined DUSP6 mRNA levels by quantitative PCR and found that they did not change upon CK2α expression (Fig. 5E). These results indicate that CK2α kinase activity regulates DUSP6 abundance by facilitating its proteasomal degradation.

FIGURE 5.

CK2α decreases protein stability of the ERK phosphatase DUSP6 in a kinase-dependent manner. A, phosphorylation of the CK2α substrate EEF1D upon expression of WT or kinase-inactive (K68M) CK2α was detected by Western blotting with a phospho-EEF1D antibody. Levels of endogenous DUSP6 protein were determined by Western blotting of lysates from A375 cells ectopically expressing CK2α(WT) or CK2α(K68M) (B) or from A375 cells depleted of endogenous CK2α by two different shRNAs (same lysates as shown in Fig. 3A) (C). D, to determine whether CK2α regulates DUSP6 protein stability, the same cells as in B were immunoblotted for DUSP6 protein after treatment for 6 h with either the proteasome inhibitor MG132 (10 μm) or DMSO vehicle control. E, to determine whether CK2α also regulates DUSP6 at the transcriptional level, quantitative RT-PCR analysis of DUSP6 mRNA levels was done on cells expressing CK2α(WT) or kinase-inactive CK2α(K68M). Results are presented as means ± S.E. (n = 3). Error bars represent S.E. n.s., not significant.

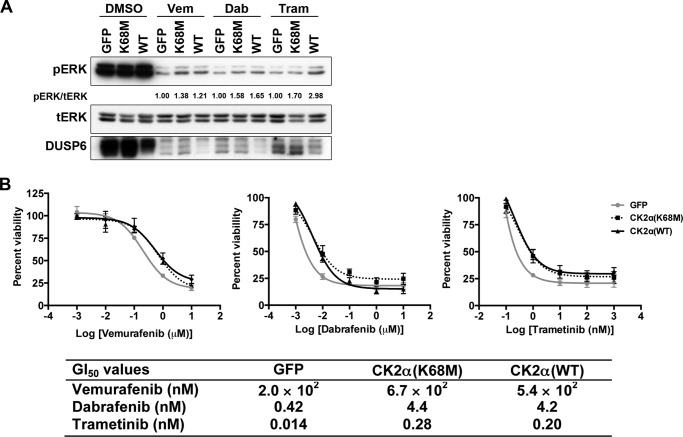

CK2α-mediated Maintenance of ERK Phosphorylation and Pathway Inhibitor Resistance Does Not Require Its Kinase Function

Given that CK2α kinase activity was essential to the decrease in DUSP6 expression (Fig. 5B), we hypothesized that kinase-inactive CK2α would not be able to maintain ERK phosphorylation when the pathway was inhibited. Unexpectedly, in the presence of both BRAFis, ERK phosphorylation was sustained to a similar degree in the presence of either CK2α(K68M) or CK2α(WT) (Fig. 6A), suggesting a kinase-independent contribution of CK2α to pERK. However, in the presence of MEKi, CK2α(K68M) exhibited a lower level of pERK compared with CK2α(WT). This potentially indicates a differential contribution of the kinase activity of CK2α to maintaining pERK, depending on which node of the pathway is inhibited (Fig. 6A). We therefore anticipated that kinase-inactive CK2α would also promote resistance in a similar fashion. Consistent with this, we found that CK2α(K68M) promoted resistance to vemurafenib, dabrafenib, and trametinib to the same extent as CK2α wild type as indicated by their respective GI50 values (Fig. 6B), indicating that CK2α-mediated BRAFi and MEKi resistance does not depend on its catalytic kinase activity. Instead, our findings indicate that the ability of CK2α to maintain ERK phosphorylation when the pathway is inhibited and to promote resistance to BRAF and MEK inhibitors is more likely due to a protein binding or scaffolding function of CK2α. Clearly, CK2α(K68M), although catalytically inactive and incapable of degrading DUSP6, maintained ERK phosphorylation and inhibitor resistance. Therefore, DUSP6 regulation by CK2α does not contribute to CK2α-mediated resistance and maintenance of pERK or cell viability upon inhibitor treatment.

FIGURE 6.

CK2α-mediated maintenance of ERK phosphorylation upon pathway inhibition and resistance to BRAFi/MEKi are both kinase-independent. A, A375 cells ectopically expressing GFP, CK2α(K68M), or CK2α(WT) were treated with BRAFi and MEKi as in Fig. 4, then lysed, and immunoblotted for pERK and total DUSP6. Total ERK (tERK) served as loading control. B, cells were treated as in A, and GI50 curves were generated after 72 h. A summary of GI50 values is shown in a table below. Results are presented as means ± S.E. (n = 4). Error bars represent S.E. Vem, vemurafenib; Dab, dabrafenib; Tram, trametinib.

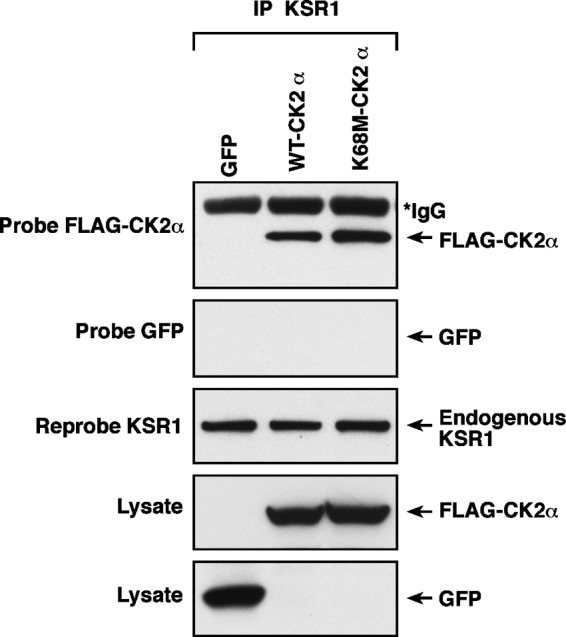

CK2α(WT) and CK2α(K68M) Bind Equally Well to the RAF-MEK-ERK Scaffold Protein KSR1

Our previous work (31) uncovered an essential role of CK2α in maximally facilitating RAF-MEK-ERK pathway activation through its direct binding to KSR1 within the KSR1 scaffolding complex that also includes RAF, MEK, and ERK. CK2α association with KSR enhances RAF phosphorylation of MEK. Given our finding here that kinase-inactive CK2α maintains ERK phosphorylation and resistance to pathway inhibitors to the same extent as its wild-type counterpart, we speculated that it too retains binding to KSR1. Accordingly, when we immunoprecipitated endogenous KSR1 from A375 cells, we detected considerable levels of ectopically expressed CK2α(WT) and CK2α(K68M) but not the GFP control (Fig. 7). This result supports our hypothesis that CK2α binding to KSR1 is kinase-independent, offering a potential mechanism by which both CK2α(WT) and CK2α(K68M) maintain ERK phosphorylation and resistance to BRAF and MEK inhibitors. Specifically, our findings are consistent with a model whereby CK2α binding enhances the efficiency of KSR1 scaffolding to facilitate ERK activation. Testing of this model would require identification of the KSR1 binding site on CK2α, which is currently unknown, to enable assessment of whether a KSR1 binding-deficient mutant of CK2α is now impaired in conferring resistance to BRAFi and/or MEKi.

FIGURE 7.

Both wild-type and kinase-inactive CK2α interact with the RAF-MEK-ERK scaffold protein KSR1. Endogenous KSR1 was immunoprecipitated (IP) from A375 cells expressing the GFP control or FLAG-tagged CK2α(WT) or kinase-inactive CK2α(K68M). Whole cell lysates and immunoprecipitates were then blotted for the presence of FLAG-CK2α and reprobed for KSR1 to ensure that equal amounts of KSR1 were immunoprecipitated. *IgG bands are from immunoprecipitation step. GFP served as a negative control to rule out nonspecific co-immunoprecipitation of the ectopic CK2α proteins (n = 2).

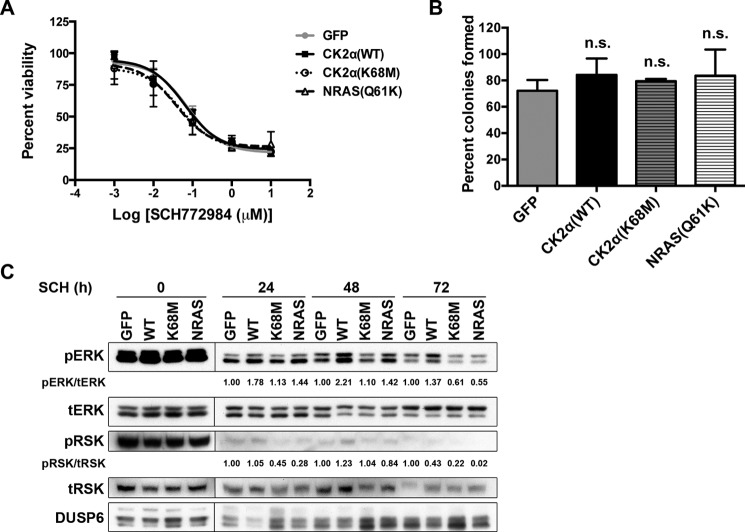

ERK Inhibition Avoids CK2α-mediated Resistance to RAF-MEK-ERK Pathway Blockade

Our model predicts that CK2α should not be able to cause resistance in melanoma cells to an inhibitor downstream of RAF and MEK that acts directly at the level of ERK. To test this model, we evaluated whether CK2α(WT) or CK2α(K68M) could cause resistance to the ERK inhibitor SCH772984 (1). Consistent with our model, overexpression of CK2α(WT), CK2α(K68M), or NRAS(Q61K) did not confer resistance to the ERKi as evidenced by the absence of either increased GI50 (Fig. 8A) or enhanced clonogenic survival (Fig. 8B). For evidence that the inhibitor correctly hit its ERK target, we examined the phosphorylation status of the ERK substrate p90 RSK (Fig. 8C). We (22) and others (1) have shown recently that decreased phospho-RSK (pRSK) is a more reliable marker of decreased flux through ERK than is ERK phosphorylation itself, not least because ERK phosphorylation rebounds quickly, whereas pRSK does not. Examination of pRSK in ERKi-treated cells at the same time point (72 h) as the GI50 analysis revealed that neither overexpressed CK2α nor mutant NRAS was able to restore ERK pathway activation in the presence of ERKi. Thus, although CK2α induces resistance to BRAFi and MEKi in a kinase-independent manner, even kinase-intact CK2α does not induce resistance to ERKi, which is an effective means of impairing the RAF-MEK-ERK pathway in these BRAF mutant melanoma cells. This finding is similar to other mechanisms that cause resistance to RAFi or MEKi in BRAF mutant melanomas where ERKi sensitivity is retained (1).

FIGURE 8.

ERK inhibitor SCH772984 is insensitive to overexpression of either CK2α(WT) or CK2α(K68M). A, the GI50 for ERKi SCH772984 is unchanged by overexpression of CK2α or by mutant NRAS. GI50 curves were generated after 72 h of ERKi treatment. Results are presented as means ± S.E. (n = 3). B, clonogenic survival in the presence of ERKi is not enhanced by overexpressed CK2α or mutant NRAS. Shown are the percentages of colonies formed by A375 cells expressing GFP, CK2α, or NRAS(Q61K) and treated with ERKi (100 nm) normalized to DMSO vehicle control. Results are presented as means ± S.E. (n = 3). n.s., non-significant compared with GFP. C, ERKi treatment shuts down ERK pathway signaling as indicated by loss of phosphorylated ERK substrate pRSK. A375 cells as in A and B were treated for 24, 48, or 72 h with 100 nm SCH772984. Error bars represent S.E. tERK, total ERK; tRSK, total RSK.

Discussion

Although targeted therapies in melanoma have substantially improved patient outcomes immediately following treatment in a subset of patients, even responsive patients are confronted with the inevitable development of resistance months later (18–21). Understanding the underlying mechanisms of innate or acquired resistance is key to developing new combination therapies to overcome tumor unresponsiveness or recurrence. In the present study, we demonstrate that abnormally elevated expression of CK2α (CSNK2A1) is sufficient to cause resistance to each of three small molecule kinase inhibitors of the RAF-MEK-ERK pathway approved for treatment of melanoma: vemurafenib, dabrafenib, and trametinib. Furthermore, we show that this resistance correlates with the rebound/maintenance of ERK activity following pathway inhibition.

Protein kinase CK2 has been previously shown to affect RAF-MEK-ERK pathway signaling by various means whose complexity has yet to be fully elucidated. Aside from fine-tuning the signaling amplitude of the RAF-MEK-ERK pathway, CK2 has been reported to regulate ERK nuclear translocation and translation of nuclear targets of ERK, which can also affect the signaling efficiency of the pathway (32). Mechanistically, CK2 kinase activity is needed to phosphorylate Ser-244 and Ser-246 in the nuclear translocation signal of ERK, allowing ERK binding to Importin7. Although nuclear ERK activation has not been directly linked to melanoma progression, lack of cytoplasmic ERK was associated with poor prognosis in primary cutaneous melanomas (33). Conversely, another study showed that the proliferation of A375 melanoma cells in vitro and in vivo was highly sensitive to an inhibitor of ERK dimerization (34) that is thought to act by decreasing ERK interactions specifically with its cytoplasmic but not nuclear substrates (35). The role of CK2α kinase in this process has not been investigated.

The distinct resistance profiles of CK2α and NRAS(Q61K) imply different mechanisms of promoting resistance. Specifically, it is known that secondary NRAS mutations that increase flux through the RAS-MEK-ERK pathway via CRAF activation can overcome inhibitor potency (24). Such a route of reactivation could easily be blocked by MEK inhibition. Consistent with this idea, NRAS(Q61K) did not confer resistance to MEK inhibitor trametinib. However, the fact that CK2α-mediated resistance is MEK inhibitor-inert suggests two possible mechanisms. The first entails some unknown bypass that leads to sustained ERK phosphorylation. This is somewhat unlikely because MEK is still the only known direct activator of ERK. The second involves steric hindrance provided by CK2α that prevents an MEK inhibitor from binding to its target effectively. Such a mechanism can be provided by a scaffolding function of CK2α as discussed below.

Intriguingly, we found that wild-type CK2α drastically reduced expression of the DUSP6, whereas CK2α silencing elevated endogenous DUSP6 protein levels. DUSP6 is a key ERK-specific phosphatase that negatively regulates the RAF-MEK-ERK pathway (27). Indeed, DUSP6 has been previously reported to interact with and be phosphorylated by CK2α (28). We further show here that CK2α-facilitated proteasomal degradation accounts for the decreased abundance of DUSP6 protein. In light of our results, it would be interesting to know whether DUSP6 expression could serve as a biomarker of CK2 inhibition.

Much to our initial surprise, we determined, using a kinase-inactive mutant of CK2α, that CK2α kinase activity is not required for either CK2α-mediated inhibitor resistance or sustained ERK phosphorylation in the context of these BRAF mutant melanoma cells. This was unexpected because CK2 is well known as a constitutively active kinase that has hundreds of endogenous substrates, and its kinase activity has largely been assumed to be responsible for its pleiotropic effects (2–4). However, the whole-kinome screen by which we identified CK2α as a potential resistance mechanism capable of inducing at least a 5-fold increase in resistance to ERK inhibitor was not performed by inhibition of the catalytic activity of the CK2α kinase but rather by siRNA-mediated depletion of expression of the entire protein (22). Therefore, this screen would capture effects induced by loss of protein binding or scaffolding functions as well as by loss of catalytic activities of the depleted kinases.

Our data suggest that the above resistance phenotypes are the result of CK2α-mediated protein-protein interactions rather than CK2α kinase activity. Consistent with this notion, we reported previously that all subunits of CK2 bind to the RAF-MEK-ERK pathway scaffolding protein KSR1 (31) and that binding of the CK2α subunit in particular to KSR1 is critical for maximal activation of the pathway (31). However, we had not tested whether the kinase activity of CK2α was required. Because we have now found that kinase deficiency does not impair CK2α binding to KSR1, we speculate that the catalytic activity-independent binding of CK2α to KSR1 helps to promote formation of the KSR1 scaffold complex and to maintain the integrity and function of the RAF-MEK-ERK pathway, enabling the sustained ERK phosphorylation observed in the presence of overexpressed CK2α even when the pathway is inhibited at the level of RAF or MEK. This hypothesis could be tested in the future once the region of CK2α that mediates KSR1 binding has been identified as that would allow interrogation of the ability of KSR1 binding-deficient mutants of CK2α to confer resistance to pathway inhibitors. Of note, overexpressed CK2α exists pretreatment. It is also possible that the trametinib binding site on efficiently scaffolded MEK may be sterically hindered compared with that of free MEK, thereby reducing the effectiveness of MEK inhibitors. It would also be of great interest to determine whether the onset of BRAFi/MEKi resistance in melanoma patients is associated with increased levels of CK2α.

The importance of CK2α protein-protein interactions versus catalytic kinase activity may differ greatly depending on context. A recent study examined the effects of a CK2α-selective kinase inhibitor, CX-4945, on the viability of BRAF mutant thyroid cancer cell lines and found synergism of CX-4945 with both the BRAFi vemurafenib and the MEKi selumetinib (36), suggesting that the kinase activity of CK2α was important for the response to BRAFi/MEKi in this tumor type. Surprisingly, when they compared the combination of vemurafenib with CX-4945 or with siRNA directed against CK2α in a patient-derived BRAF mutant melanoma cell line, they found an additive effect of each on cell death (36). The equivalent effects on vemurafenib responses of kinase-intact and kinase-inactive CK2α that we observed argue that the kinase activity is not important in the vemurafenib response of BRAF mutant melanoma, but it is certainly possible that other genetic differences may also affect the relative roles of catalytic activity versus protein-protein interactions. Our study differs from work by Borgo et al. (16), who found a kinase-dependent role of CK2 in imatinib-resistant chronic myeloid leukemia. These differences may reflect the divergent genetic and epigenetic contexts of BCR-ABL mutant chronic myeloid leukemia versus BRAF mutant melanomas. For example, in our model system, BRAF(V600E) is the driver mutation, and CK2α is an integral part of the KSR1 scaffolding complex that maximizes signaling efficiency through the RAF-MEK-ERK pathway. In contrast, in chronic myeloid leukemia, BCR-ABL is the driver mutation, and CK2α activity has been shown to be directly regulated by BCR-ABL (37). Therefore, CK2α can play distinct roles in different tumor contexts. It is also interesting that, although our original siRNA screen identified CK2α as a mediator of resistance to ERKi in KRAS mutant pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma cells (22), CK2α did not mediate resistance to ERKi in BRAF mutant melanoma cells. We believe that this is also due to tumor heterogeneity. Indeed, when we performed our siRNA screen in two different pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma cell lines, we found that there was little overlap of the hits; CK2α was identified as a hit in CFPAC-1 but not in SW1990 cells. We were unable to determine the specific basis for such disparate results, but they certainly highlight the tremendous heterogeneity among tumor cell lines, even among those derived from the same cancer type (e.g. pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma), let alone different cancer types (e.g. pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma versus melanoma). Clearly, much remains to be elucidated about the role of CK2α in responses to inhibitors of the RAF-MEK-ERK pathway, a role that is likely to be as complex as its hundreds of substrates and numerous biological activities portend.

In summary, our results identify a role for CK2α in promoting resistance to BRAF and MEK but not ERK inhibitors in BRAF mutant melanoma. We also demonstrate, for the first time to our knowledge, a kinase-independent function of CK2α in modulating cellular signaling. These findings represent a novel mode of innate resistance to RAF-MEK-targeted therapy in BRAF mutant melanoma, which may not be easily addressed by inhibition of the dysregulated CK2α kinase. Perhaps ongoing efforts to develop KSR inhibitors may achieve success in part via interference with CK2α.

Experimental Procedures

Cell Culture and Reagents

A375, A2058, Sbc12A, Malme-3, and 293T cell lines were grown in DMEM-H supplemented with 10% FBS (HyCloneTM, Thermo Scientific) and 1% gentamycin/kanamycin (Tissue Culture Facility, Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill). SK-MEL-28 and RPMI-7951 were grown in minimum Eagle's medium α (Gibco) supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% gentamycin/kanamycin. Primary neonatal human epidermal melanocytes from lightly pigmented, moderately pigmented, and darkly pigmented donors were generously provided by Dr. Guang Hu (National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, Research Triangle Park) and were grown in Medium 245 supplemented with human melanocyte growth supplement (a kind gift from Dr. Guang Hu). The BRAFi vemurafenib (PLX4032) was a generous gift from Gideon Bollag (Plexxikon). The BRAFi dabrafenib (GSK2118436) and MEKi trametinib (GSK1120212) were purchased from Selleckchem. The ERKi SCH772984 was a generous gift from Ahmed Samatar (Merck). MG132 was purchased from Calbiochem (474790).

Plasmid Constructs and Gateway Cloning

The CK2α expression construct, pDONR223-CSNK2A1 (Human ORFeome v5.1), was purchased from University of North Carolina's Tissue Culture Facility. pHAGE-FLAG (N-terminal tag) empty vector was a generous gift from Ben Major, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Both CK2α and NRAS(Q61K) were cloned into the pHAGE-FLAG vector by Gateway cloning using LR Enzyme Clonase Mix (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's protocol. A set of five shRNAs targeting CK2α (CSNK2A1) in pLKO.1 vector was purchased from the Lenti-shRNA Core Facility at University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Target sequences are indicated in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Target sequences

TRC, The RNAi Consortium.

| shRNA | TRC clone ID | Target sequence |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | TRCN0000000606 | 5′-GCTGCATTTAGGTGGAGACTT-3′ |

| 2 | TRCN0000000607 | 5′-CGTAAACAACACAGACTTCAA-3′ |

| 3 | TRCN0000000608 | 5′-CAAGAATATAATGTCCGAGTT-3′ |

| 4 | TRCN0000000609 | 5′-AGAATTTGAGAGGAGGTCCCA-3′ |

| 5 | TRCN0000000610 | 5′-CCAAGAATATAATGTCCGAGT-3′ |

Lentivirus Production and Infection

To produce lentivirus, 293T cells were transfected with pHAGE vector-based GFP, CK2α, or NRAS(Q61K) in combination with psPAX2 and pMD2.G at a ratio of 4:3:1. After overnight transfection, the culture medium was changed to DMEM-H supplemented with 20% FBS. Thirty-six hours later, viral supernatants were harvested and filtered through a sterile 0.45-μm filter to remove cell debris. Cleared supernatants were aliquoted and frozen at −80 °C until use. Cells were infected with 500 μl of virus in 5 μg/ml Polybrene (Millipore) overnight. Selection of transduced cells in puromycin (1 or 2 μg/ml for A375 or SK-MEL-28 cells, respectively) was complete at 48 h after infection.

Western Blotting

Cells were washed twice with ice-cold PBS and lysed in radioimmune precipitation assay buffer (150 mm NaCl, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 50 mm Tris, pH 8.0) containing 1× protease inhibitors (BaculoGoldTM protease inhibitor mixture, BD Biosciences, 51-21426Z) and 1× phosphatase inhibitors (HaltTM phosphatase inhibitor mixture, Thermo Scientific, 78420). Lysates were depleted of cell debris by centrifugation at maximum speed (4 °C, 10 min), and then proteins were quantified by Bradford assay (DCTM Protein Assay, Bio-Rad), normalized, reduced, denatured at 95 °C for 5 min, and resolved by SDS gel electrophoresis. Proteins were transferred to PDVF membranes (Millipore, IPFL00010) and probed with primary antibodies recognizing pERK1/2(Thr-202/Tyr-204) (Cell Signaling Technology, 4370), ERK1/2 (Cell Signaling Technology, 9102), phospho-MEK1/2(Ser-217/221) (Cell Signaling Technology, 9154), pRSK(Thr-259/Ser-263) (Cell Signaling Technology, 9344), DUSP6 (Abcam, ab54940), β-actin (Sigma, A5316), CK2α (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-373894), FLAG tag (Sigma, F3165; Novus, NBP1-06712SS), or GFP (Roche Applied Science, 11814460001). A rabbit antibody to the phosphorylated CK2α substrate EEF1D was a generous gift from David W. Litchfield (Western University). A rabbit-anti KSR1 antibody (home-made, Morrison laboratory) was used to detect KSR1 following immunoprecipitation. After incubation with the appropriate secondary anti-mouse (GE Healthcare, NA931V) or anti-rabbit (GE Healthcare, NA934V) antibody, proteins were detected by chemiluminescence (Thermo Scientific, 34075). Blots were developed by exposure to x-ray film or by the ChemiDocTM MP Imaging System (Bio-Rad) for quantification. Film was scanned, and densitometry analysis was performed with ImageJ 1.45s.

Pharmacologic GI50 Assay

Growth inhibition assays were performed as described previously (24, 38) with minor modifications. Cultured cells were seeded into 96-well plates (2,000 cells/well). Sixteen hours after seeding (baseline), serial dilutions of inhibitors were prepared in DMSO and added to cells, yielding final drug concentrations ranging from 1 nm to 10 μm for vemurafenib, dabrafenib, and SCH772984 and 0.1 nm to 1 μm for trametinib with the final volume of DMSO not exceeding 1%. Cells were incubated for 72 h following addition of drug. To measure cell proliferation, 5 mg/ml 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (Sigma-Aldrich, M5655) was added 1:10 into wells and incubated at 37 °C for 4 h. Formazan products were solubilized using acidified isopropanol (0.04 n HCl in isopropanol), and absorbance was measured at 562 nm with a background subtraction at 650 nm. Percent cell growth under each condition was calculated as follows: Cell growth (%) = 100 × (T − T0)/(C − T0) where T0 is absorbance at baseline, T is absorbance of drug-treated wells at 72 h, and C is absorbance of DMSO-treated wells at 72 h. A minimum of three replicates was performed for each cell line and drug combination. Data from growth inhibition assays were modeled using a non-linear regression curve fit with a sigmoidal dose response (GraphPad Prism, v5.0c). The resulting curves were displayed and GI50 values were also generated using GraphPad Prism.

Clonogenic Assay

Clonogenic assays were performed as described previously (39) with slight modifications. Briefly, cells were plated in duplicate wells at 100 cells/well in 6-well plates and allowed to adhere for 3 h at 37 °C after which culture medium was carefully removed and replaced with medium containing either DMSO vehicle control or inhibitor. Two weeks following drug treatment, cells were washed once with PBS and then fixed and stained with crystal violet/paraformaldehyde for 30 min at room temperature. The stain was decanted, and plates were carefully rinsed with distilled water until background staining of the wells was minimized. Finally, plates were air-dried, and colonies were counted manually using a cell counter.

Site-directed Mutagenesis

Site-directed mutagenesis of CK2α was performed using a QuikChange II XL site-directed mutagenesis kit (Agilent). Forward primer 5′-GCCATCAACATCACAAATAATGAAAAAGTTGTTGTTATGATTCTCAAGCCAG-3′ and reverse primer 5′-CTGGCTTGAGAATCATAACAACAACTTTTTCATTATTTGTGATGTTGATGGC-3′ were used to introduce a catalytic site mutation (K68M) into pDONR223-CSNK2A1 with bold nucleotides showing the site of mutagenesis. Reaction conditions strictly followed the manufacturer's protocol.

RNA Isolation, Reverse Transcription, and Real Time PCR

Total RNA was isolated from cells using the Thermo RNA kit (Thermo Scientific), and then 0.5 μg of total RNA was reverse transcribed to generate cDNA using the iScriptTM cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Real time PCR was performed using the SsoFastTM EvaGreen® Supermix (Bio-Rad) on the Bio-Rad CFX-96 Real-Time PCR System. β-Actin was used for normalization. DUSP6 was amplified using forward primer 5′-CGACTGGAACGAGAATACGG-3′ and reverse primer 5′-TTGGAACTTACTGAAGCCACCT-3′.

Co-immunoprecipitation

Co-immunoprecipitation assays were performed as described previously (31). In brief, two 10-cm dishes of A375 cells were washed twice with cold PBS and lysed in 1% Nonidet P-40 buffer (20 mm Tris, pH 8.0, 137 mm NaCl, 10% glycerol, 1% Nonidet P-40 alternative, 0.15 unit/ml aprotinin, 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 0.5 mm sodium vanadate, 20 μm leupeptin) using 600 μl of lysis buffer/10-cm dish. The lysates were clarified by centrifugation, and equivalent amounts of protein lysate were incubated with a mouse anti-human KSR1 antibody (Sigma-Aldrich, WH0008844M1) and protein G-Sepharose beads for 3 h at 4 °C. Immunoprecipitated complexes were collected by centrifugation, washed extensively with 1% Nonidet P-40 buffer, and then examined by immunoblotting analysis.

Author Contributions

B. Z., C. J. D., and A. D. C. conceived the study, designed the study, and wrote the paper. B. Z. designed, performed, and analyzed the experiments except Fig. 7, which was conceived by D. K. M. and designed and performed by D. A. R. All authors analyzed the results, contributed to editing, and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We thank Lee M. Graves (University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill) for helpful discussions, M. Ben Major (University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill) for the pHAGE-FLAG-puro Gateway vector, William Kaufmann (University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill) for normal human melanocyte pellets, Guang Hu (National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences) for normal human melanocytes, David W. Litchfield (Western University, Ontario, Canada) for antibodies to CK2 substrates, Gideon Bollag (Plexxikon) for vemurafenib, and Ahmed Samatar (Merck) for SCH772984.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants CA042978, CA179193, and CA199235 (to A. D. C. and C. J. D.) and ZIA BC 010329 from the NCI (to D. K. M. and D. A. R.) and by the Pancreatic Cancer Action Network-American Association for Cancer Research (to A. D. C. and C. J. D.). The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

- CK2

- casein kinase 2

- BRAFi

- BRAF inhibitor

- MEKi

- MEK inhibitor

- KSR

- kinase suppressor of Ras

- pERK

- phosphorylated ERK

- GI50

- 50% growth inhibition

- DUSP6

- dual specificity phosphatase 6

- ERKi

- ERK inhibitor

- RSK

- ribosomal s6 kinase

- pRSK

- phospho-RSK.

References

- 1. Morris E. J., Jha S., Restaino C. R., Dayananth P., Zhu H., Cooper A., Carr D., Deng Y., Jin W., Black S., Long B., Liu J., Dinunzio E., Windsor W., Zhang R., et al. (2013) Discovery of a novel ERK inhibitor with activity in models of acquired resistance to BRAF and MEK inhibitors. Cancer Discov. 3, 742–750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Pinna L. A. (2002) Protein kinase CK2: a challenge to canons. J. Cell Sci. 115, 3873–3878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Pinna L. A., and Allende J. E. (2009) Protein kinase CK2 in health and disease: protein kinase CK2: an ugly duckling in the kinome pond. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 66, 1795–1799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Trembley J. H., Wang G., Unger G., Slaton J., and Ahmed K. (2009) Protein kinase CK2 in health and disease: CK2: a key player in cancer biology. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 66, 1858–1867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hanif I. M., Hanif I. M., Shazib M. A., Ahmad K. A., and Pervaiz S. (2010) Casein kinase II: an attractive target for anti-cancer drug design. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 42, 1602–1605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ortega C. E., Seidner Y., and Dominguez I. (2014) Mining CK2 in cancer. PLoS One 9, e115609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Piazza F. A., Ruzzene M., Gurrieri C., Montini B., Bonanni L., Chioetto G., Di Maira G., Barbon F., Cabrelle A., Zambello R., Adami F., Trentin L., Pinna L. A., and Semenzato G. (2006) Multiple myeloma cell survival relies on high activity of protein kinase CK2. Blood 108, 1698–1707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Martins L. R., Lúcio P., Silva M. C., Anderes K. L., Gameiro P., Silva M. G., and Barata J. T. (2010) Targeting CK2 overexpression and hyperactivation as a novel therapeutic tool in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood 116, 2724–2731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Giusiano S., Cochet C., Filhol O., Duchemin-Pelletier E., Secq V., Bonnier P., Carcopino X., Boubli L., Birnbaum D., Garcia S., Iovanna J., and Charpin C. (2011) Protein kinase CK2α subunit over-expression correlates with metastatic risk in breast carcinomas: quantitative immunohistochemistry in tissue microarrays. Eur. J. Cancer 47, 792–801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lin K. Y., Tai C., Hsu J. C., Li C. F., Fang C. L., Lai H. C., Hseu Y. C., Lin Y. F., and Uen Y. H. (2011) Overexpression of nuclear protein kinase CK2α catalytic subunit (CK2α) as a poor prognosticator in human colorectal cancer. PLoS One 6, e17193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zhang H. X., Jiang S. S., Zhang X. F., Zhou Z. Q., Pan Q. Z., Chen C. L., Zhao J. J., Tang Y., Xia J. C., and Weng D. S. (2015) Protein kinase CK2α catalytic subunit is overexpressed and serves as an unfavorable prognostic marker in primary hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncotarget 6, 34800–34817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bae J. S., Park S. H., Kim K. M., Kwon K. S., Kim C. Y., Lee H. K., Park B. H., Park H. S., Lee H., Moon W. S., Chung M. J., Sylvester K. G., and Jang K. Y. (2015) CK2α phosphorylates DBC1 and is involved in the progression of gastric carcinoma and predicts poor survival of gastric carcinoma patients. Int. J. Cancer 136, 797–809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mitev V., Miteva L., Botev I., and Houdebine L. M. (1994) Enhanced casein kinase II activity in metastatic melanoma. J. Dermatol. Sci. 8, 45–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Di Maira G., Brustolon F., Bertacchini J., Tosoni K., Marmiroli S., Pinna L. A., and Ruzzene M. (2007) Pharmacological inhibition of protein kinase CK2 reverts the multidrug resistance phenotype of a CEM cell line characterized by high CK2 level. Oncogene 26, 6915–6926 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kreutzer J. N., Ruzzene M., and Guerra B. (2010) Enhancing chemosensitivity to gemcitabine via RNA interference targeting the catalytic subunits of protein kinase CK2 in human pancreatic cancer cells. BMC Cancer 10, 440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Borgo C., Cesaro L., Salizzato V., Ruzzene M., Massimino M. L., Pinna L. A., and Donella-Deana A. (2013) Aberrant signalling by protein kinase CK2 in imatinib-resistant chronic myeloid leukaemia cells: biochemical evidence and therapeutic perspectives. Mol. Oncol. 7, 1103–1115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Menzies A. M., and Long G. V. (2014) Systemic treatment for BRAF-mutant melanoma: where do we go next? Lancet Oncol. 15, e371–e381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lito P., Rosen N., and Solit D. B. (2013) Tumor adaptation and resistance to RAF inhibitors. Nat. Med. 19, 1401–1409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Spagnolo F., Ghiorzo P., and Queirolo P. (2014) Overcoming resistance to BRAF inhibition in BRAF-mutated metastatic melanoma. Oncotarget 5, 10206–10221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zhang W. (2015) BRAF inhibitors: the current and the future. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 23, 68–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sullivan R. J., and Flaherty K. T. (2013) Resistance to BRAF-targeted therapy in melanoma. Eur. J. Cancer 49, 1297–1304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hayes T. K., Neel N. F., Hu C., Gautam P., Chenard M., Long B., Aziz M., Kassner M., Bryant K. L., Pierobon M., Marayati R., Kher S., George S. D., Xu M., Wang-Gillam A., Samatar A. A., Maitra A., Wennerberg K., Petricoin E. F. 3rd, Yin H. H., Nelkin B., Cox A. D., Yeh J. J., and Der C. J. (2016) Long-term ERK inhibition in KRAS-mutant pancreatic cancer is associated with MYC degradation and senescence-like growth suppression. Cancer Cell 29, 75–89 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Shields J. M., Thomas N. E., Cregger M., Berger A. J., Leslie M., Torrice C., Hao H., Penland S., Arbiser J., Scott G., Zhou T., Bar-Eli M., Bear J. E., Der C. J., Kaufmann W. K., Rimm D. L., and Sharpless N. E. (2007) Lack of extracellular signal-regulated kinase mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling shows a new type of melanoma. Cancer Res. 67, 1502–1512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Nazarian R., Shi H., Wang Q., Kong X., Koya R. C., Lee H., Chen Z., Lee M. K., Attar N., Sazegar H., Chodon T., Nelson S. F., McArthur G., Sosman J. A., Ribas A., and Lo R. S. (2010) Melanomas acquire resistance to B-RAF(V600E) inhibition by RTK or N-RAS upregulation. Nature 468, 973–977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Solit D. B., and Rosen N. (2014) Towards a unified model of RAF inhibitor resistance. Cancer Discov. 4, 27–30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Crews C. M., Alessandrini A., and Erikson R. L. (1992) The primary structure of MEK, a protein kinase that phosphorylates the ERK gene product. Science 258, 478–480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Muda M., Boschert U., Dickinson R., Martinou J. C., Martinou I., Camps M., Schlegel W., and Arkinstall S. (1996) MKP-3, a novel cytosolic protein-tyrosine phosphatase that exemplifies a new class of mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatase. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 4319–4326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Castelli M., Camps M., Gillieron C., Leroy D., Arkinstall S., Rommel C., and Nichols A. (2004) MAP kinase phosphatase 3 (MKP3) interacts with and is phosphorylated by protein kinase CK2α. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 44731–44739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ji H., Wang J., Nika H., Hawke D., Keezer S., Ge Q., Fang B., Fang X., Fang D., Litchfield D. W., Aldape K., and Lu Z. (2009) EGF-induced ERK activation promotes CK2-mediated disassociation of α-catenin from β-catenin and transactivation of β-catenin. Mol. Cell 36, 547–559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gyenis L., Duncan J. S., Turowec J. P., Bretner M., and Litchfield D. W. (2011) Unbiased functional proteomics strategy for protein kinase inhibitor validation and identification of bona fide protein kinase substrates: application to identification of EEF1D as a substrate for CK2. J. Proteome Res. 10, 4887–4901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ritt D. A., Zhou M., Conrads T. P., Veenstra T. D., Copeland T. D., and Morrison D. K. (2007) CK2 is a component of the KSR1 scaffold complex that contributes to Raf kinase activation. Curr. Biol. 17, 179–184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Plotnikov A., Chuderland D., Karamansha Y., Livnah O., and Seger R. (2011) Nuclear extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1 and 2 translocation is mediated by casein kinase 2 and accelerated by autophosphorylation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 31, 3515–3530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 33. Jovanovic B., Kröckel D., Linden D., Nilsson B., Egyhazi S., and Hansson J. (2008) Lack of cytoplasmic ERK activation is an independent adverse prognostic factor in primary cutaneous melanoma. J. Invest. Dermatol. 128, 2696–2704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Herrero A., Pinto A., Colón-Bolea P., Casar B., Jones M., Agudo-Ibáñez L., Vidal R., Tenbaum S. P., Nuciforo P., Valdizán E. M., Horvath Z., Orfi L., Pineda-Lucena A., Bony E., Keri G., Rivas G., Pazos A., Gozalbes R., Palmer H. G., Hurlstone A., and Crespo P. (2015) Small molecule inhibition of ERK dimerization prevents tumorigenesis by RAS-ERK pathway oncogenes. Cancer Cell 28, 170–182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Casar B., Pinto A., and Crespo P. (2008) Essential role of ERK dimers in the activation of cytoplasmic but not nuclear substrates by ERK-scaffold complexes. Mol. Cell 31, 708–721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Parker R., Clifton-Bligh R., and Molloy M. P. (2014) Phosphoproteomics of MAPK inhibition in BRAF-mutated cells and a role for the lethal synergism of dual BRAF and CK2 inhibition. Mol. Cancer Ther. 13, 1894–1906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hériché J. K., and Chambaz E. M. (1998) Protein kinase CK2α is a target for the Abl and Bcr-Abl tyrosine kinases. Oncogene 17, 13–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Johannessen C. M., Johnson L. A., Piccioni F., Townes A., Frederick D. T., Donahue M. K., Narayan R., Flaherty K. T., Wargo J. A., Root D. E., and Garraway L. A. (2013) A melanocyte lineage program confers resistance to MAP kinase pathway inhibition. Nature 504, 138–142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Franken N. A., Rodermond H. M., Stap J., Haveman J., and van Bree C. (2006) Clonogenic assay of cells in vitro. Nat. Protoc. 1, 2315–2319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Gao J., Aksoy B. A., Dogrusoz U., Dresdner G., Gross B., Sumer S. O., Sun Y., Jacobsen A., Sinha R., Larsson E., Cerami E., Sander C., and Schultz N. (2013) Integrative analysis of complex cancer genomics and clinical profiles using the cBioPortal. Sci. Signal 6, pl1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]