Abstract

Objective

Deposition of Aβ-containing plaques as evidenced by amyloid imaging and CSF Aβ42 is an early indicator of preclinical Alzheimer disease (AD). To better understand their relationship during the earliest preclinical stages, we investigated baseline CSF markers in cognitively normal individuals at different stages of amyloid deposition defined by longitudinal amyloid imaging with Pittsburgh Compound B (PIB): 1) PIB-negative at baseline and follow-up (PIB−, normal); 2) PIB− at baseline but PIB-positive at follow-up (PIB converters, early preclinical AD); and 3) PIB-positive at baseline and follow-up (PIB+, preclinical AD).

Methods

Cognitively normal individuals (n=164) who had undergone baseline PIB scan and CSF collection within one year of each other and at least one additional PIB follow-up were included. Amyloid status was defined dichotomously using an a priori mean cortical cut-off.

Results

PIB converters (n=20) at baseline exhibited significantly lower CSF Aβ42 compared to those who remained PIB− (n=123), but higher compared to PIB+ group (n=21). A robust negative correlation (r=−0.879, p=0.0001) between CSF Aβ42 and absolute (but sub-threshold) PIB binding was observed during this early preclinical stage. The negative correlation was not as strong once individuals were PIB+ (r=−0.456, p=0.038), and there was no correlation in the stable PIB− group (p=0.905) or in the group (n=10) with early symptomatic AD (p=0.537).

Interpretation

CSF Ab42 levels are tightly coupled with cortical amyloid load in the earliest stages of preclinical AD, and began to decrease dramatically prior to the point when an abnormal threshold of cortical accumulation is detected with amyloid imaging.

INTRODUCTION

Alzheimer disease (AD), the most common cause of dementia in the elderly and the third leading cause of death in the US1, is characterized by a long (~10 to 20 years) preclinical period during which pathology accumulates in the absence of overt clinical symptoms2. The deposition of β-amyloid (amyloid) plaques in the brain is one of the earliest measurable pathological changes in AD3, 4 and can be successfully monitored during this preclinical period using positron emission tomography (PET) with amyloid tracers such as Pittsburgh Compound B (PIB)5–7. Studies of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) in similar cohorts have reported low levels of amyloid-β1–42 (Aβ42) in individuals who are considered amyloid-positive by global PET thresholds8–11, thus supporting the use of CSF Aβ42 levels as a proxy for underlying amyloid. What remains to be determined is the relationship between CSF Aβ42 (and CSF biomarkers of tau-related neuronal injury) and amyloid burden in cognitively normal (CN) individuals prior to, during, and after the transition from amyloid-negative to amyloid-positive defined by global thresholds for cortical amyloid PET positivity. Elucidating these relationships will aid in our understanding of the temporal dynamics of amyloid accumulation during the earliest pathologic stage(s) of AD, as well as inform the design and interpretation of clinical trials aimed at preventing the development of cognitive symptoms in individuals who are in this early preclinical stage.

As a first step in achieving this goal, we used data from longitudinal PIB scans from research participants in studies of aging and dementia at the Knight Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (ADRC) to select CN individuals (who had associated baseline CSF) considered to be: 1) PIB− at baseline and remained PIB− at follow-up (PIB−, normal); 2) PIB− at baseline but several years later became PIB-positive (PIB converters, early preclinical AD); and 3) PIB+ at baseline and remained PIB+ at follow-up (PIB+, preclinical AD). All individuals remained CN through follow-up. We then evaluated the relationship between concentrations of CSF biomarkers and amount of cortical PIB retention at baseline in these three groups and compared them to those in PIB+ individuals who were diagnosed with very mild to moderate AD (symptomatic AD).

Materials and Methods

Participants

Participants were community dwelling volunteers enrolled in studies of normal aging and dementia at the Knight Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (ADRC) at Washington University in St. Louis. Participants were 45–84 years of age at baseline and had no neurological, psychiatric or systemic medical illness that might compromise longitudinal study participation, nor medical contraindication to lumbar puncture (LP) for CSF collection or PIB PET. All participants underwent cognitive assessments, neurological evaluations and clinical assessments at each visit that included the Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR)12. A CDR score of 0 indicates cognitive normality, whereas a CDR of 0.5, 1 or 2 indicates very mild, mild or moderate dementia, respectively.

Cognitive Measures

All participants completed a battery of standard cognitive measures typically within 2 weeks of the clinical evaluation. Knight ADRC cognitive batteries have been described in detail in prior publications13, 14. Two cognitive outcomes with good psychometric characteristics and sensitivity to preclinical AD and that were available for all participants in the study were included in this study: the free recall score from the Free and Cued Selective Reminding Test (FCSRT15), a measure of episodic memory, and the total correct score from the Animal Naming test16, a verbal fluency measure associated with semantic memory.

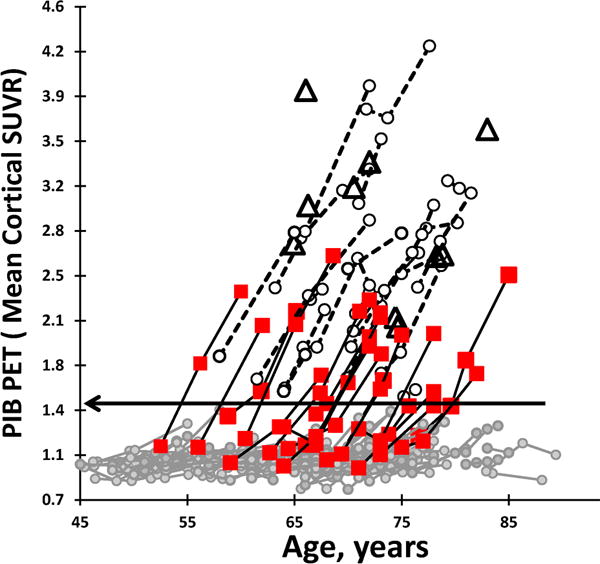

To be included in the present analysis, participants had to have baseline clinical assessment, LP and PIB PET within 12 months of each other and at least one subsequent follow-up PIB PET. The mean interval between baseline CSF and PIB measurements in this cohort was 0.2 ± 0.7 years (n=174). The scan could be before or after the LP. Three groups of CN individuals were selected based on their longitudinal pattern of PIB positivity defined by a previously determined mean cortical threshold17 (Fig. 1). One hundred twenty-three individuals were CN (CDR 0) and PIB− at both baseline and follow-up (PIB−); 20 individuals were CDR 0 and PIB− at baseline but PIB+ at follow-up (PIB converters); and 21 individuals were CDR 0 and PIB+ at both baseline and follow-up (PIB+). All of these participants remained CN (CDR 0) throughout the follow-up period. For comparison purposes, a fourth group was included comprised of 10 PIB+ CDR+ participants diagnosed with mild to moderate AD dementia (symptomatic AD, sAD)18. All procedures were approved by the Washington University Human Research Protection Office, and written informed consent was obtained from each participant.

Figure 1.

Brain amyloid deposition as measured by mean cortical standardized uptake value ratio (SUVR) using repeated PIB PET scans in cognitively normal individuals, plotted by the age of the participants at the time of their scan. One hundred twenty-three individuals were PIB negative on the baseline and follow-up scans (PIB−, gray circles); 20 were PIB-negative on the baseline scan and PIB-positive on the follow-up scan (PIB converter, square); 21 were PIB-positive on baseline and follow-up scans (PIB−, open circles); 10 were diagnosed with very mild to moderate AD dementia (symptomatic AD) (open triangles). Horizontal line indicates dichotomous cortical threshold for PIB positivity (SUVR>1.42).

CSF collection, processing and analysis

CSF (20–30ml) was collected at ~8:00am after overnight fasting as previously described8. Samples were gently inverted to avoid possible gradient effects, briefly centrifuged at low speed to pellet any cellular debris and aliquoted into polypropylene tubes prior to freezing at −84°C. CSF samples were analyzed for Aβ42, total tau (tau), and phospho-tau181 (ptau181) by enzyme-linked immunosorbant assay (ELISA) (INNOTEST, Fujirebio, Ghent, Belgium). For all biomarker measures, samples were continuously kept on ice, and assays were performed on sample aliquots after a single thaw following initial freezing.

Imaging Assessment

High resolution T1-weighted structural MRI was performed at 1.5 Tesla (n=63, Siemens Vision, Erlangen, Germany) or 3T (n=111, Siemens TIM Trio) using a magnetization-prepared rapid gradient echo (MPRAGE) sequence as previously described19, 20. Pittsburgh compound B (PIB) PET21 was used as the imaging biomarker for β-amyloid. Participants underwent a 60-minute dynamic PET scan following injection of ~10 mCi PIB22. The PIB PET imaging has been described in detail17, 22 and was conducted with a Siemens 962 HR+ ECAT PET scanner (Siemens/CTI, Knoxville KY) or on a Siemens Biograph 40 scanner. Structural MRIs were parcellated using FreeSurfer23 (Martinos Center, Boston, MA) and, within each region, partial volume correction was applied24. Standard uptake value ratios (SUVR) were calculated from regions of interest (ROI), with PIB-positivity defined as the mean cortical SUVR (from prefrontal, parietal and temporal ROIs) >1.42, a value commensurate with a mean cortical binding potential of 0.18 defined previously for a similar cohort17, 22. Cerebellar cortex, a region negative for amyloid in AD, was used as the reference region. Since the difference in spatial resolution between the two scanners used in this study is small (~0.01 SUVR unit), the same PIB cut-off was used for the entire dataset.

Statistical analysis

Baseline demographics were summarized as mean ± SD or percent and compared with ANOVA for continuous variables or logistic regression for dichotomous variables. Specific group differences were evaluated post hoc with Student’s t-tests. Group differences in CSF biomarkers and PIB deposition were assessed with ANOVA or ANCOVA adjusting for baseline age, gender, education, time of PIB follow up and presence of at least one APOE ɛ4 allele (APOE4). Post-hoc comparisons using Student’s t-tests were conducted only after an omnibus test indicated joint significance in the participant groups. The assumption of homogeneity of variance in these models was evaluated with a likelihood ratio test and, where appropriate, the variance was estimated separately for different groups. Akaike information criterion25 was used to decide if fewer variables could be used to fit the data. Pearson’s correlation coefficient was used to assess the association between CSF biomarkers and PIB deposition, both unadjusted and adjusted for age, gender, education, time of PIB follow-up and APOE4. In order to assess differences in these associations among the participant groups, we used linear regression models to regress PIB deposition on each CSF biomarker, participant group, as well as their interaction, both unadjusted and adjusted for covariates. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc, Cary, NC). P-values <0.05 indicated statistical significance.

Results

Participant demographics and baseline PIB and CSF biomarker results are shown in Table 1. Roughly two-thirds of individuals in all groups were female. Those in the sAD and PIB+ groups were significantly older at baseline compared to the PIB− and PIB converter groups (p<0.0001). There was a main effect of group on the prevalence of a family history of AD (p=0.002) and APOE4-positivity (p<0.0001) with the PIB− having the lowest prevalence and the sAD having the highest, with PIB converters and PIB+ groups falling intermediately. As expected, the sAD group exhibited significantly lower scores on the MMSE (p<0.02), FCSRT (p<0.0001) and Animal Naming (p<0.04) than the PIB−, PIB converter and PIB+ groups. Performance on FCSRT trended lower in the stable PIB+ compared to the PIB− group (p=0.0519).

Table 1.

Demographics and biomarker data.

| Characteristic | PIB− | PIB converter | PIB+ | sAD | P-valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | 123 | 20 | 21 | 10 | |

| Baseline age, yrs | 63.1 ± 9.43,4 | 65.9 ± 6.54 | 69.5 ± 5.61 | 72.9 ± 6.11,2 | <0.0001 |

| Gender, M, % | 35.0 | 30.0 | 38.1 | 30.0 | 0.9404 |

| Education, yrs | 16.0 ± 2.44 | 15.6 ± 2.44 | 16.1 ± 2.34 | 13.5 ± 2.71,2,3 | 0.0451 |

| Family history of AD, % | 50.83,4 | 79.01 | 52.44 | 1001,3 | 0.0020 |

| APOE ɛ4, positive, % | 22.03,4 | 55.01 | 52.41 | 90.01 | <0.0001 |

| PIB scan interval, yrs | 5.6 ± 1.93 | 5.2 ± 1.13 | 2.07 ± 2.01 | NA | <0.0001 |

| MMSE | 29.3 ± 1.04 | 29.3 ± 0.94 | 28.8 ± 1.54 | 23.2 ± 5.91,2,3 | <0.0001 |

| FCSRT-Free Recall | 32.2 ± 5.8b, 4 | 31.3 ± 5.34 | 29.4 ± 5.84 | 17.3 ± 5.2c, 1,2,3 | <0.0001 |

| Animal Namingd | 22.2 ± 5.2b, 4 | 22.5 ± 4.84 | 21.1 ± 5.84 | 12.9 ± 7.61,2,3 | <0.0001 |

| CSF | |||||

| Aβ42, pg/ml | 718 ± 1942,3,4 | 570 ± 1941,3,4 | 373 ± 1171,2 | 338 ± 841,2 | <0.0001 |

| tau, pg/ml | 227 ± 1032,3,4 | 281 ± 1001,3,4 | 424 ± 1691,2,4 | 600 ± 1941,2,3 | <0.0001 |

| p-tau181, pg/ml | 46 ± 193,4 | 52 ± 163,4 | 71 ± 271,2 | 84 ± 271,2 | <0.0001 |

| tau/Aβ42 | 0.32 ± 0.132,3,4 | 0.56 ± 0.281,3,4 | 1.24 ± 0.601,2,4 | 1.82 ± 0.571,2,3 | <0.0001 |

| p-tau181/Aβ42 | 0.07 ± 0.032,3,4 | 0.10 ± 0.051,3,4 | 0.20 ± 0.101,2 | 0.25 ± 0.071,2 | <0.0001 |

| PIB, baseline SUVR | |||||

| Mean Cortical | 0.97 ± 0.072,3,4 | 1.13 ± 0.121,3,4 | 2.24 ± 0.601,2,4 | 2.96 ± 0.661,2,3 | <0.0001 |

| Prefrontal | 0.95 ± 0.082,3,4 | 1.13 ± 0.171,3,4 | 2.36 ± 0.691,2,4 | 2.96 ± 0.291,2,3 | <0.0001 |

| Parietal | 1.0 ± 0.092,3,4 | 1.10 ± 0.161,3,4 | 2.21 ± 0.571,2,4 | 2.82 ± 0.611,2,3 | <0.0001 |

| Temporal | 0.97 ± 0.082,3,4 | 1.06 ± 0.091,3,4 | 1.80 ± 0.571,2,4 | 2.44 ± 0.451,2,3 | <0.0001 |

| Occipital | 1.16 ± 0.123,4 | 1.22 ± 0.173,4 | 1.41 ± 0.341,2 | 1.63 ± 0.361,2 | 0.0001 |

Abbreviations: Aβ, β-amyloid; APOE, apolipoprotein E; PIB converter, CDR 0 PIB-negative at baseline but PIB-positive at follow-up; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination (scores can range from 0–30, with 30 a perfect score); PIB−, CDR 0 PIB-negative at baseline and follow-up; PIB+, CDR 0 PIB-positive at baseline and follow-up; sAD, CDR>0 symptomatic AD; FCSRT-Free Recall, Free and Cued Selective Reminding Test (scores can range from 0–48, with 48 a perfect score); SUVR, standard uptake value ratio.

Omnibus test of overall group differences based on ANOVA for continuous characteristics and logistic/exact logistic regression for dichotomous characteristics.

post-hoc p<0.05 compared to PIB−;

post-hoc p<0.05 compared to PIB converter;

post-hoc p<0.05 compared to PIB+;

post-hoc p<0.05 compared to sAD.

n=121

n=8

Higher scores on Animal Naming are indicative of better performance.

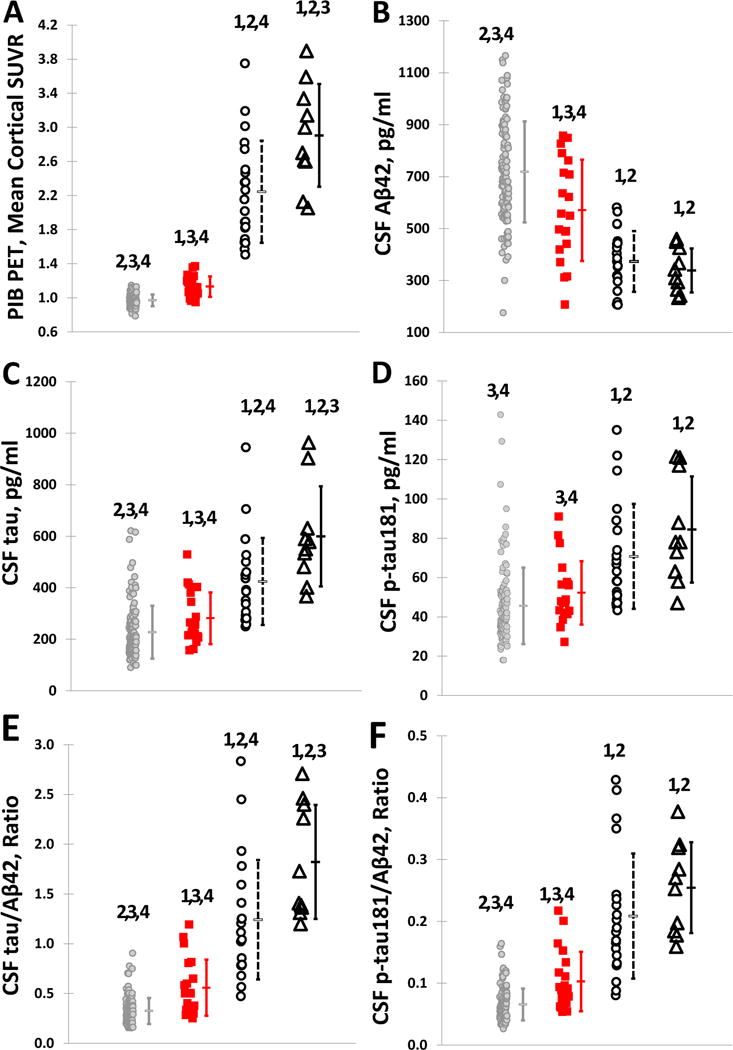

Baseline amyloid imaging and CSF biomarkers

Highly significant overall group differences (p<0.0001) were observed in mean cortical and regional Aβ deposition by PIB PET and CSF Aβ42, tau, p-tau181 (and the ratios of tau(s)/Aβ42) at the time of the baseline scan (Table 1, Fig. 2). As expected based on the study design, baseline mean cortical PIB binding was significantly higher in the sAD and CN PIB+ groups compared to the PIB− and PIB converter groups (all p<0.0001) (Fig. 2A). Levels of cortical PIB deposition in CN individuals who converted from PIB− to PIB+ at follow-up (early preclinical AD) was also higher at baseline than in those who remained PIB− (p=0.0001) (Fig. 2B), and they were higher in sAD than in preclinical (CN PIB+) individuals (p=0.0104). Overall statistical results were highly similar when analyses were adjusted for covariates including age, gender, APOE4, time of PIB follow-up and education (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Individual baseline values of (A) mean cortical PIB SUVR, CSF (B) Aβ42, (C) tau, (D) p-tau181, (E) tau/Aβ42 and (F) ptau181/Aβ42 in PIB− (gray circles), PIB converter (square), PIB+ (open circles), and symptomatic AD (open triangles) groups.1statistically different from PIB−; 2statistically different from PIB converter; 3statistically different from PIB+; 4statistically different from sAD.

Group differences were also observed in levels of CSF biomarkers at the time of baseline PIB scans (Table 1, Fig. 2). Although post-hoc analyses demonstrated no differences between CN stable PIB+ and sAD groups in levels of CSF Aβ42 (p=0.3562), the differences were observed in tau in unadjusted analyses (p=0.0266), but not when adjusted for covariates (p=0.147), and ptau181in adjusted (p=0.0213) but not unadjusted (p=0.2021) analyses. The differences observed among the CN groups were a function of where they fell in the amyloid trajectory as defined by their longitudinal PIB patterns. Individuals who converted from PIB− to PIB+ (PIB converters) exhibited significantly lower levels of CSF Aβ42 at the time of their initial negative baseline scan compared to CN PIB− individuals who remained PIB− (p=0.0041) (Fig. 2B), but significantly higher Aβ42 levels compared to those who were already PIB+ at baseline (p=0.0005). Even when controlling for baseline PIB, converters exhibited lower levels of CSF Aβ42 at the time of their baseline scan compared to PIB− individuals (p=0.0056 when adjusting only for baseline PIB and p=0.0225 when adjusting for all covariates including baseline PIB). As expected, the PIB+ group had lower Aβ42 levels than those who started and remained PIB− (p<0.0001). Also, differences were observed between PIB converters and stable PIB− individuals in levels of tau (p=0.0336) (Fig. 2C) but not p-tau181 (p=0.1087) (Fig. 2D). However, concentrations of CSF tau and ptau181 were higher in CN individuals who were stably PIB+ compared to those who were stably PIB− (p<0.0001 and p=0.0004, respectively), as well as in those who converted from PIB− to PIB+ (p=0.0022 and p=0.0109, respectively). CSF tau/Aβ42 (Figure 2E) and p-tau181/Aβ42 (Figure 2F) were significantly higher in CN stable PIB+ and sAD groups compared to stable PIB− and PIB converters (p<0.001, Table 1). Results were virtually identical after adjusting for covariates. No difference was observed in CSF ptau181/Aβ42 between CN stable PIB+ and sAD groups (p=0.1652), while tau/Aβ42 was higher in sAD (p=0.0179), although this difference was not significant after adjusting for covariates (p=0.8786). Converters demonstrated higher ptau181/Aβ42 (p=0.00114) and similar trend for tau/Aβ42 (p=0.0016) compared to CN stable PIB− individuals. These differences remained significant after adjusting for covariates.

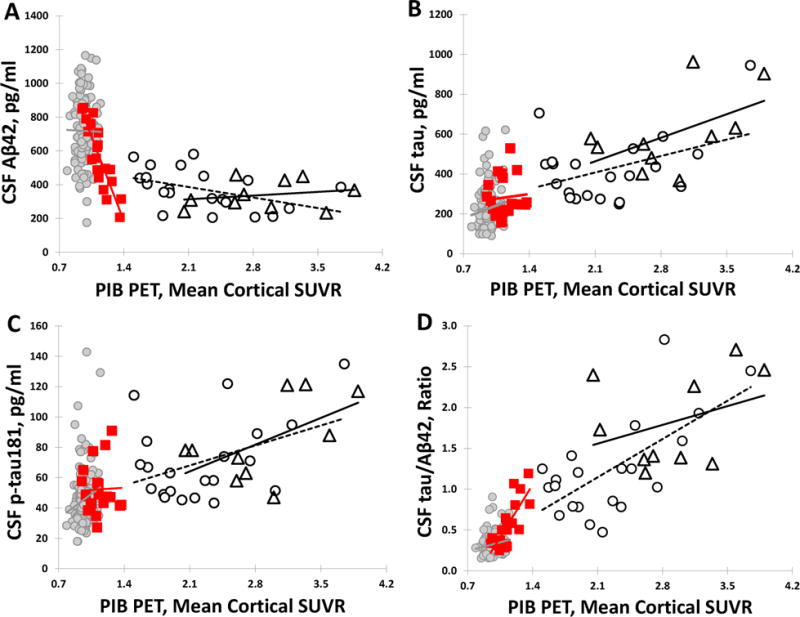

Correlation between CSF biomarkers and PIB deposition at the baseline scan

In order to elucidate the patterns of CSF biomarkers during the early stages of amyloid deposition, associations between individual markers and PIB binding in the different groups were evaluated. No significant correlations were observed between baseline levels of CSF Aβ42 and mean cortical PIB binding in individuals with sAD (p=0.5373) or in CN individuals who started and remained PIB− (p=0.905) (Fig. 3A). A negative correlation was observed in the stable PIB+ group (r=−0.456, p=0.038), but was no longer statistically significant after adjusting for covariates (p=0.060). In contrast to the other groups, a highly significant negative correlation was observed between baseline CSF Aβ42 and cortical PIB SUVR in PIB-negative individuals who then went on to become PIB-positive (as defined by the cortical threshold) (PIB converter) (r=−0.879, p<0.0001). Although CSF Aβ42 levels in the PIB converter group are more strongly correlated with PIB SUVR relative to the PIB+ group (r=−0.879 vs. −0.456, respectively), the slope estimate in the converter group (PIB SUVR regressed on CSF Aβ42 levels) is much smaller (by ~77%) than that of the PIB+ group (r=−0.00054 vs −0.00234). In other words, equivalent changes in CSF Aβ42 levels were associated with substantially smaller changes in mean cortical PIB in the PIB converter group relative to the PIB+ group.

Figure 3.

Cross-sectional associations between mean cortical PIB SUVR and CSF (A) Aβ42, (B) tau, (C) ptau181 and (D) tau/Aβ42 in PIB− (gray circles), PIB converter (square), PIB+ (open circles), and symptomatic AD (open triangles) groups. Regression lines are shown for illustration purposes.

Despite apparent positive relationships between CSF tau and ptau181 and the amount of cortical PIB binding in individuals who were PIB+ at baseline (sAD and CN PIB+ groups), these correlations did not reach statistical significance (all p>0.05) (Fig. 3B and C). Relationships between amyloid imaging and the CSF tau/Aβ42 ratio (Fig. 3D) were virtually identical to those of Aβ42 alone (no significant correlation with PIB SUVR in the stable PIB− and sAD groups, p>0.05; positive correlations in the PIB+ [r=0.667, p=0.0009] and PIB converter [r=0.780, p<0.0001] groups). Similar results were observed for the ptau181/Aβ42 ratio (data not shown), and all results were virtually identical after adjusting for covariates.

Discussion

Evaluation of CSF in CN individuals who have undergone longitudinal amyloid imaging allowed us to characterize the CSF biomarker patterns during the earliest stages of preclinical amyloidosis defined by categorical PIB cut-offs: stable PIB− (normal), stable PIB+ (preclinical AD) and during the conversion from PIB− to PIB+ (early preclinical AD). Consistent with previous studies in similar cohorts in early disease stages8, 11, the low CSF Aβ42 levels observed in the preclinical (PIB+) cases were not different from symptomatic individuals who had already received a diagnosis of very mild or mild AD dementia. The observation that PIB-negative individuals in the converter group already exhibited significantly lower levels of CSF Aβ42 at baseline compared to those who remained PIB− suggests that CSF Aβ42 levels begin to drop prior to cortical amyloid reaching the categorical cut-off defined by PIB PET, a conclusion consistent with a recent study using data from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI)26. The robust correlation (r=−0.879) observed between concentrations of CSF Aβ42 and absolute (but still sub-threshold) levels of PIB binding in the converter group indicates that these biomarker measures are tightly associated during this earliest process of Aβ aggregation and deposition; however, this association is less strong at later stages (preclinical and sAD, respectively). This suggests that the progressive lowering of CSF Aβ42 during this timeframe reflects active deposition into Aβ aggregates such as oligomers and fibrils present in amyloid plaques, a finding that is supported by both in vitro and in vivo data9, 27–30. Together these data not only support the use of CSF Aβ42 and amyloid imaging measures as indicators of amyloidosis in early AD, but suggests their potential utility when used as continuous variables (as opposed to historically higher dichotomous variables defined by specific cut-offs) for defining the very earliest pathologic changes.

We observed a robust negative correlation between CSF Aβ42 and the amount of cortical PIB retention in CN individuals several years before they met the criteria for PIB-positivity (PIB converters in the early preclinical stage), a less strong but still negative correlation in individuals who were already PIB–positive for several years (PIB+, preclinical AD), and no correlation in individuals PIB-negative on both baseline and follow-up scans (PIB−, normal), or in symptomatic (CDR >0) participants diagnosed with AD. Interestingly, not only were the strengths of the associations between CSF Aβ42 and mean cortical PIB SUVR different among the early stage groups as a function of where they fell along the trajectory of progressive amyloid aggregation and deposition, but the groups demonstrated different patterns of association as evidenced by the slopes. Notably, there was a substantially larger reduction in the CSF Aβ42 level per unit change in PIB retention in the early preclinical (PIB converter) group compared to those in the later stage preclinical (PIB+). These findings support a scenario in which CSF Aβ42 levels drop progressively in the very earliest stage of early preclinical AD pathology, likely reflecting its sequestration into oligomeric forms or amyloid plaques that initially remain below the level of detection with PIB PET imaging. This timing is consistent with within-person decreases in CSF Aβ42 levels starting in early middle-age (45–54 years) that were recently reported in a larger cohort of CN participants, with PIB-positivity only observed in older individuals (55–74 years)31. Our data further suggest that in later stages of preclinical AD, levels of CSF Aβ42 continue to decrease, but to a smaller degree and eventually leveling out, while fibrillar amyloid plaques progressively form and continue to accumulate. Interestingly, in a few cases, low levels of CSF Aβ42 were not associated with appreciable PIB retention during similar follow-up, suggesting that this process of conversion to PIB positivity may take longer in some people, perhaps related to more efficient clearance of amyloid or additional mechanisms influencing plaque formation. Low CSF Aβ42 levels in these stable PIB− individuals may also reflect lower overall production of Aβ species. Longer amyloid imaging and clinical follow-up of these individuals will be informative.

In addition, a subset of individuals who were amyloid-positive by PIB at both baseline and follow-up (PIB+) exhibited higher baseline CSF Aβ42 levels than those who were initially amyloid-negative but then converted to PIB-positive (PIB converters). However, perhaps these apparently higher baseline levels observed in these individuals actually represent a decrease from earlier levels. Direct comparison of longitudinal changes in CSF and amyloid imaging within individuals will be required to better understand the temporal dynamics of these Aβ-related changes during the early preclinical period. Such dynamics could conceivably have an impact on clinical trial design, notably those that use CSF and/or amyloid imaging as enrollment and/or outcome measures in secondary prevention and/or early stage symptomatic trials (http://www.nia.nih.gov/alzheimers/clinical-trials/). The current data suggest it may be possible to even better refine trial design in terms of patient enrollment and biomarker outcomes (to confirm target engagement and assess pathologic disease progression and response to treatment) by utilizing appropriate CSF and/or amyloid imaging variables. It is conceivable that the presence of cortical fibrillar amyloid defined by conservative PET imaging cut-offs may still be considered too late in the disease process to exact a meaningful response to therapy. A better understanding of the temporal relationship between changes in soluble Aβ species (as measured in the CSF) and its aggregation into insoluble amyloid in the brain (as measured by amyloid PET) may also impact the selection of biomarker outcomes for therapies targeting the different forms of Aβ (soluble vs oligomeric vs aggregated/fibrillar).

In conclusion, we observed coupled changes in CSF Aβ42 and cortical PIB retention throughout the earliest stages of AD pathology, prior to reaching the global cortical threshold defining preclinical AD. Further investigation is needed to determine exactly when these changes develop in middle-aged individuals destined to develop AD pathology, the relationship of these pathologic markers within individuals over time, and what factors influence their progression. Limitations of our study include the cross-sectional nature of the CSF analyses, use of different PET scanners as well as the relatively modest imaging follow-up (~5 years in the PIB− and PIB converter groups). In this study, we used a cutoff for PIB-positivity (SUVR of 1.42) that can be considered conservative compared to what is currently used by some other groups32–36. However, it should be noted that our PIB SUVR measurement is obtained with partial volume correction and, therefore, is greater than what would be obtained by groups that do not employ this correction. Also, ROIs used to calculate an average mean cortical SUVR across lab groups in the field partially, but not completely, overlap. In future studies it will also be important to evaluate the specific topography of fibrillar amyloid accumulation in the very initial stages of preclinical AD and their associations with CSF biomarkers and eventual cognitive decline.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH: P50 AG05681 (JCM), P01 AG026276 (JCM), P01 AG03991 (JCM), the Dana Foundation, and the Charles and Joanne Knight Alzheimer’s Disease (ADRC) Initiative. We acknowledge the contributions of Jason Hassenstab, PhD for guidance regarding the psychometric data, and the Administration, Clinical, Biomarker, Imaging and Biostatistics Cores of the Knight ADRC. We gratefully acknowledge the altruism of our research participants and their families.

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

AGV and AMF were responsible for study concept and design.

AGV, LM, MSJ, YS, BG, CX, DMH, TLCB, JCM, and AMF were responsible for data acquisition and analysis.

AGV, BG, TLCB, and AMF were responsible for drafting the manuscript and figures.

Potential conflicts of interests

AGV, LM, MSJ, BG, YS, CX, DMH, TLSB, JCM, and AMF have no conflict to report.

References

- 1.James BD, Leurgans SE, Hebert LE, Scherr PA, Yaffe K, Bennett DA. Contribution of Alzheimer disease to mortality in the United States. Neurology. 2014 Mar 25;82(12):1045–50. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Price JL, McKeel DW, Jr, Buckles VD, et al. Neuropathology of nondemented aging: presumptive evidence for preclinical Alzheimer disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2009 Jul;30(7):1026–36. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2009.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Braak H, Del Tredici K. Where, when, and in what form does sporadic Alzheimer’s disease begin? Current opinion in neurology. 2012 Dec;25(6):708–14. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0b013e32835a3432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jack CR, Knopman DS, Jagust WJ, et al. Tracking pathophysiological processes in Alzheimer’s disease: an updated hypothetical model of dynamic biomarkers. The Lancet Neurology. 2013;12(2):207–16. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70291-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sojkova J, Zhou Y, An Y, et al. Longitudinal patterns of beta-amyloid deposition in nondemented older adults. Arch Neurol. 2011 May;68(5):644–9. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2011.77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Villemagne VL, Pike KE, Chetelat G, et al. Longitudinal assessment of Abeta and cognition in aging and Alzheimer disease. Ann Neurol. 2011 Jan;69(1):181–92. doi: 10.1002/ana.22248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vlassenko AG, Mintun MA, Xiong C, et al. Amyloid-beta plaque growth in cognitively normal adults: Longitudinal [(11) C]Pittsburgh compound B data. Ann Neurol. 2011 Nov;70(5):857–61. doi: 10.1002/ana.22608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fagan AM, Mintun MA, Mach RH, et al. Inverse relation between in vivo amyloid imaging load and cerebrospinal fluid Abeta42 in humans. Ann Neurol. 2006 Mar;59(3):512–9. doi: 10.1002/ana.20730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fagan AM, Mintun MA, Shah AR, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid tau and ptau(181) increase with cortical amyloid deposition in cognitively normal individuals: implications for future clinical trials of Alzheimer’s disease. EMBO Mol Med. 2009 Nov;1(8–9):371–80. doi: 10.1002/emmm.200900048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grimmer T, Riemenschneider M, Forstl H, et al. Beta amyloid in Alzheimer’s disease: increased deposition in brain is reflected in reduced concentration in cerebrospinal fluid. Biol Psychiatry. 2009 Jun 1;65(11):927–34. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.01.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jagust WJ, Landau SM, Shaw LM, et al. Relationships between biomarkers in aging and dementia. Neurology. 2009 Oct 13;73(15):1193–9. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181bc010c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morris JC. The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): current version and scoring rules. Neurology. 1993;43(11):2412–4. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.11.2412-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johnson DK, Storandt M, Morris JC, Langford ZD, Galvin JE. Cognitive profiles in dementia: Alzheimer disease vs healthy brain aging. Neurology. 2008 Nov 25;71(22):1783–9. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000335972.35970.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pizzie R, Hindman H, Roe CM, et al. Physical activity and cognitive trajectories in cognitively normal adults: the adult children study. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2014 Jan-Mar;28(1):50–7. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e31829628d4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grober E, Lipton RB, Katz M, Sliwinski M. Demographic influences on free and cued selective reminding performance in older persons. Journal of clinical and experimental neuropsychology. 1998 Apr;20(2):221–6. doi: 10.1076/jcen.20.2.221.1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goodglass H, Kaplan E. Boston diagnostic aphasia examination booklet. 2nd. Malvern, PA: Lea & Febiger; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Su Y, D’Angelo GM, Vlassenko AG, et al. Quantitative analysis of PiB-PET with FreeSurfer ROIs. PLoS One. 2013;8(11):e73377. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0073377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morris JC, Blennow K, Froelich L, et al. Harmonized diagnostic criteria for Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations. Journal of internal medicine. 2014 Mar;275(3):204–13. doi: 10.1111/joim.12199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Buckner RL, Head D, Parker J, et al. A unified approach for morphometric and functional data analysis in young, old, and demented adults using automated atlas-based head size normalization: reliability and validation against manual measurement of total intracranial volume. Neuroimage. 2004 Oct;23(2):724–38. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gordon BA, Blazey T, Benzinger TL, Head D. Effects of aging and Alzheimer’s disease along the longitudinal axis of the hippocampus. J Alzheimers Dis. 2013;37(1):41–50. doi: 10.3233/JAD-130011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Klunk WE, Engler H, Nordberg A, et al. Imaging brain amyloid in Alzheimer’s disease with Pittsburgh Compound-B. Ann Neurol. 2004 Mar;55(3):306–19. doi: 10.1002/ana.20009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mintun MA, Larossa GN, Sheline YI, et al. [11C]PIB in a nondemented population: potential antecedent marker of Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2006 Aug 8;67(3):446–52. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000228230.26044.a4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fischl B, van der Kouwe A, Destrieux C, et al. Automatically parcellating the human cerebral cortex. Cereb Cortex. 2004 Jan;14(1):11–22. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhg087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Su Y, Blazey TM, Snyder AZ, et al. Partial volume correction in quantitative amyloid imaging. Neuroimage. 2015 Feb 15;107:55–64. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.11.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Akaike H. A new look at the statistical model identification. IEEE Trans Autom Control. 1974;19:716–23. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Palmqvist S, Mattsson N, Hansson O, Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging I Cerebrospinal fluid analysis detects cerebral amyloid-beta accumulation earlier than positron emission tomography. Brain. 2016 Apr;139(Pt 4):1226–36. doi: 10.1093/brain/aww015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maggio JE, Stimson ER, Ghilardi JR, et al. Reversible in vitro growth of Alzheimer disease beta-amyloid plaques by deposition of labeled amyloid peptide. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992 Jun 15;89(12):5462–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.12.5462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hong S, Quintero-Monzon O, Ostaszewski BL, et al. Dynamic analysis of amyloid beta-protein in behaving mice reveals opposing changes in ISF versus parenchymal Abeta during age-related plaque formation. J Neurosci. 2011 Nov 2;31(44):15861–9. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3272-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roh JH, Huang Y, Bero AW, et al. Disruption of the sleep-wake cycle and diurnal fluctuation of beta-amyloid in mice with Alzheimer’s disease pathology. Sci Transl Med. 2012 Sep 5;4(150):150ra22. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3004291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Potter R, Patterson BW, Elbert DL, et al. Increased in vivo amyloid-beta42 production, exchange, and loss in presenilin mutation carriers. Sci Transl Med. 2013 Jun 12;5(189):189ra77. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3005615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sutphen CL, Jasielec MS, Shah AR, et al. Longitudinal Cerebrospinal Fluid Biomarker Changes in Preclinical Alzheimer Disease During Middle Age. JAMA neurology. 2015 Sep;72(9):1029–42. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2015.1285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ng S, Villemagne VL, Berlangieri S, et al. Visual assessment versus quantitative assessment of 11C-PIB PET and 18F-FDG PET for detection of Alzheimer’s disease. J Nucl Med. 2007 Apr;48(4):547–52. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.106.037762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jack CR, Jr, Knopman DS, Weigand SD, et al. An operational approach to National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association criteria for preclinical Alzheimer disease. Ann Neurol. 2012 Jun;71(6):765–75. doi: 10.1002/ana.22628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mormino EC, Brandel MG, Madison CM, et al. Not quite PIB-positive, not quite PIB-negative: slight PIB elevations in elderly normal control subjects are biologically relevant. Neuroimage. 2012 Jan 16;59(2):1152–60. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.07.098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cohen AD, Mowrey W, Weissfeld LA, et al. Classification of amyloid-positivity in controls: comparison of visual read and quantitative approaches. Neuroimage. 2013 May 1;71:207–15. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Villeneuve S, Rabinovici GD, Cohn-Sheehy BI, et al. Existing Pittsburgh Compound-B positron emission tomography thresholds are too high: statistical and pathological evaluation. Brain. 2015 Jul;138(Pt 7):2020–33. doi: 10.1093/brain/awv112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]