Abstract

Objective

To systematically compare transthyretin with primary amyloid neuropathy to define their natural history and the underlying mechanisms for differences in phenotype and natural history.

Methods

All patients with defined amyloid subtype and peripheral neuropathy who completed autonomic testing and EMG at Mayo Clinic Rochester between 1993 and 2013 were included. Medical records were reviewed for time of onset of defined clinical features. The degree of autonomic impairment was quantified using the composite autonomic severity scale. Comparisons were made between acquired and inherited forms of amyloidosis.

Results

101 cases of amyloidosis with peripheral neuropathy were identified, 60 primary and 41 transthyretin. 20 transthyretin cases were found to have Val30Met mutations, 21 had other mutations. Compared to primary cases, transthyretin cases had longer survival, longer time to diagnosis, higher composite autonomic severity scale scores, greater reduction of upper limb nerve conduction study amplitudes, more frequent occurrence of weakness, and later nonneuronal systemic involvement. Four systemic markers (cardiac involvement by echocardiogram; weight loss over 10 pounds; orthostatic intolerance; fatigue) in combination were highly predictive of poor survival in both groups.

Interpretation

These findings suggest that transthyretin has earlier and greater predilection for neural involvement and more delayed systemic involvement. The degree and rate of systemic involvement is most closely related to prognosis.

Introduction

Amyloidosis is a rare condition, caused by extracellular deposition of misfolded, insoluble proteins in organs and tissues and is largely fatal when left untreated. Classification of amyloidosis is accorded by the altered protein comprising amyloid fibrils.1, 2 In almost all cases of amyloidosis involving peripheral nerve, amyloid fibrils are either formed by immunoglobulin light chains or mutant transthyretin (TTR).3 Light chain amyloid stems from systemic plasma cell dyscrasia (primary or AL amyloidosis), the most common cause of amyloidosis. Peripheral neural involvement has been reported to occur in 17–35% of AL amyloidosis cases,4–7 and in a majority of cases of TTR amyloidosis.2 Other than AL and TTR amyloidosis, only rare kindreds with amyloidogenic mutations of gelsolin8, 9 and apolipoprotein A110 are known to develop amyloid neuropathy.

The progressive clinical syndromes seen in both AL and TTR amyloidosis correlate with the spread of amyloid deposition to affected tissues, including peripheral nerves.11–13 Amyloid neuropathy is characterized by prominent, early involvement of somatic and autonomic “c” fibers, leading to a length dependent, symmetric syndrome of thermanesthesia, autonomic symptoms, and burning neuropathic pain.14, 15 However, it is recognized that all nerve segments and fiber types can be involved to greater or lesser degrees, with all patterns of peripheral neural involvement reported,16–21 according amyloid its status as one of the hallmark mimics among peripheral nerve diseases. Neuropathy accompanied by prominent autonomic failure and end-organ involvement manifesting in gastrointestinal dysmotility, erectile dysfunction, orthostatic hypotension, and heart failure is highly suspicious for amyloidosis.5, 22 Constitutional symptoms such as weight loss and fatigue are common and can further help distinguish amyloidosis from other causes of peripheral neuropathy.7, 22

Age of onset of TTR amyloidosis, as well as penetrance and specific clinical features of the disease, vary widely between the amyloidogenic mutations present, or indeed between the countries of origin among those sharing the same mutation.2 Since over 100 amyloidogenic TTR mutations have been described, many existing only sporadically or within single families, wide variation in phenotype and natural history is expected.12, 23 However, it has generally been thought that TTR amyloidosis follows a more gradually progressive clinical course than does AL, with longer survival in the absence of treatment, though no less inevitably terminal.12 Peripheral neural involvement is frequent and prominent, and most commonly presents as a length dependent, small fiber predominant peripheral neuropathy with autonomic involvement.24, 25 Cardiac involvement occurs in a majority, though the time from onset to cardiac involvement varies. A detailed prognostic staging system has not been formulated for TTR amyloidosis, though poor survival after diagnosis is thought to be most closely related to the severity of cardiac and gastrointestinal involvement.2 Liver transplant to discontinue hepatic production of mutant TTR improves survival overall,26–28 though in a minority of cases cardiac amyloidosis and peripheral neuropathy may continue to progress.29–32 Medications such as diflunisal and tafamidis prevent TTR amyloidosis by stabilization of the less amyloidogenic tetrameric form of the TTR molecule.

Detailed retrospective cohort studies have described the natural history of AL amyloidosis.5–7, 15 As in TTR amyloidosis, peripheral neuropathy commonly presents as a length-dependent, symmetric, and small-fiber predominant neuropathy with autonomic involvement, though all patterns of peripheral neural involvement can occur. The clinical decline in AL amyloid is often precipitous, with a mean survival of 24 months after diagnosis, most significantly determined by the extent of cardiac or renal involvement.33, 34 Cardiac indicators have been integrated into a formal staging system,35 and specific echocardiographic features have been determined to have prognostic value.33 Congestive heart failure and nephrotic syndrome are the most common causes of death, including among those patients who presented with neuropathic symptoms exclusively.7

Not uncommonly, diagnosis of amyloidosis is difficult. Because of uneven distribution of amyloid deposits in different organ systems, less invasive diagnostic tests such as fat pad biopsy can have low sensitivity. We here provide a systematic linking of natural history of TTR vs AL amyloid neuropathy to the underlying pathophysiology, based on a detailed analysis of clinical features, electrophysiologic findings, clinical autonomic biomarkers and detailed autonomic function tests. The goal was to identify clinical and laboratory predictors of favorable and poor outcome, and to better understand the differences in pathophysiology of TTR vs AL amyloid neuropathy.

Materials and Methods

We included all patients with amyloidosis with a defined amyloid subtype and peripheral neuropathy who completed standardized autonomic testing at Mayo Clinic between January 1993 and December 2013. Medical records were reviewed for amyloid subtype and clinical features, including date of first onset of amyloid-related symptoms, date of diagnosis, date of death, time followed clinically, and time from diagnosis to death if applicable. This study was approved by the institutional review board of Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN.

Neurophysiologic test results and dates (electromyography and nerve conduction studies (EMG), autonomic reflex screen (ARS), and thermoregulatory sweat test (TST)), and the pattern of neurologic symptoms and deficits were recorded. EMG results were noted in terms of the pattern of neuropathic findings, and the amplitude (mV or μV) of ulnar motor, median sensory, peroneal motor, and sural sensory nerve conduction studies. Amplitudes were each converted to a percentile value, a standardized value calculated from the Mayo Clinic nerve conduction normative database according to age and gender of each patient at the time of the study.36 Laboratory studies done within 2 months of diagnosis were recorded, including lambda and kappa free light chains, brain NTpro-BNP, and troponins.

ARS results were analyzed for QSART volumes at four standard sites, Valsalva ratio and heart rate variability (to deep breathing), orthostatic hypotension with head up tilt, and blood pressure responses to the Valsalva maneuver. ARS testing is completed in approximately 60 minutes. TST results were recorded noting the pattern and percentage of body surface anhidrosis. Composite autonomic severity scale (CASS) scores were calculated according to published criteria (table 1).37 Briefly, the CASS score is comprised of sudomotor (3 points maximum), adrenergic (4 points maximum) and vagal (3 points maximum) components. For each component, a score of 1, 2, or 3 connotes mild, moderate or severe involvement. Sudomotor scoring is primarily based on QSART but additional information can be gathered from TST result when available. A 30mmHg drop in blood pressure is used rather than 20mmHg in calculating CASS score, as this was shown previously to reduce false positives from 5% to 1%.38

Table 1.

Clinical Autonomic Severity Scale (CASS). Severity of autonomic dysfunction is based on performance on the Autonomic Reflex Screen, consisting of deep breathing, Valsalva maneuver, head up tilt and Q-Sweat. Maximum severity gives a total of 10 points, with 3 points for sudomotor dysfunction, 3 points for cardiovascular dysfunction, and 4 points for adrenergic dysfunction. Thermoregulatory sweat testing (TST) may add to the sudomotor index, but is not required (in brackets). BP = blood pressure; HRDB = heart rate response to deep breathing; VR = Valsalva ratio. Phases refer to components of the Valsalva maneuver: IIE and IIL are the early and late portions of phase II.

| Sudomotor index | |

| 1= | Single site abnormal on Q-Sweat or Length-dependent pattern (distal sweat volume <1/3 of proximal value) or [<25% body anhidrosis on TST] |

| 2= | Single site <50% of lower limit on Q-Sweat [25–50% anhidrosis on TST] |

| 3= | Two or more sites <50% of lower limit on Q-Sweat |

| Cardiovascular heart rate index | |

| 1= | HRDB or VR mildly decreased (>50% of lower limit) |

| 2= | HRDB or VR decreased to <50% of lower limit |

| 3= | Both HRDB and VR decreased to <50% of lower limit |

| Adrenergic index | |

| 1= | Phase IIE decrease of <40 but >20mmHg mean BP or Phase IIL does not return to baseline or Decrease in pulse pressure to <50% of baseline |

| 2= | Phase IIE decrease of <40 but >20mmHg mean BP and Phase IIL or IV absent |

| 3= | Phase IIE decrease of >40 mmHg and Absent phase IIL and IV |

| 4= | Criteria for 3 and Orthostatic hypotension (systolic BP decrease >30mmHg or mean BP decrease >20mmHg) |

The clinical history was reviewed for the presence and date of first onset of paresthesias, numbness, weakness, orthostatic lightheadedness, diarrhea/constipation, orthopnea, oliguria, weight loss, sicca syndrome, sexual dysfunction, and fatigue. Cardiac involvement was dated to the first echocardiogram diagnostic of amyloid infiltration. Fatigue was identified based on its description in the review of systems as severe and persistent, significantly impairing normal daily activities. Orthostatic intolerance was identified based on a description of upright lightheadedness or syncope. Weight loss was defined as an unintended loss of 10 pounds or more, as reported by the patient. A measured weight loss using two in-house data points was rarely available, in part since weight loss frequently preceded the initial Mayo visit.

The date of onset of the first symptom attributable to amyloidosis was considered the index date (time=0) for each patient. The time of onset of all subsequent clinical features are recorded in months relative to this index date. If a clinical feature is described but a precise time of onset not noted, the date of the encounter when a clinical feature is first noted is marked as the date of onset. Each clinical feature was also noted categorically to have or have not occurred in the first 12 months after disease onset.

Pattern of neuropathic involvement was determined algorithmically according to the following series of binary definitions: 1) the presence of generalized autonomic failure (GAF) based on a CASS score of 5 or greater, or 4 or greater plus orthostatic hypotension seen on head up tilt; 2) the presence of peripheral neuropathy based on physical examination and EMG; 3) somatic small fiber neuropathy based on physical examination and/or quantitative sensory testing (QST); 4) the presence of neuropathic pain based on history. The patterns found based on these categorizations were: 1) GAF plus polyneuropathy with pain, 2) GAF plus polyneuropathy without pain, 3) GAF only, 4) polyneuropathy without GAF, and 5) GAF and somatic small fiber neuropathy. The polyneuropathy, if present, was further categorized as 1) sensory predominant, 2) motor predominant, or 3) sensory-motor according to the presence of numbness and/or weakness based on history and physical examination, or sensory and/or motor involvement on EMG.

Statistical analysis

Univariate comparisons of the above features were done between AL and TTR cases, and also between Val30Met and other TTR cases, using two-sided t-tests or Fisher’s exact tests as appropriate. P-values are based on comparisons of 95% confidence intervals of the means. Kaplan-Meier curves were created for each of the chronologic features listed above, including time to death, with separate curves for AL and TTR cases. Subjects were excluded from the survival analyses if their date of death was not known, and in the case of the clinical feature accrual analyses, if the occurrence or time of onset of the clinical feature could not be determined. Multivariate analyses were constructed using a step-down method taking into consideration covariance and statistical significance.

Results

107 cases of amyloid neuropathy were identified, comprising 75 males and 32 females, with average age of 62.2 years at diagnosis (+/− SD 11.5 years). 75 subjects were known to be deceased at the time of the review, and 32 known to be alive. 60 AL and 47 TTR cases were identified.

Among TTR cases, gene sequencing was completed in 41 patients – 20 were found to have Val30Met mutations, 21 had other mutations, with the next most common being Thr60Ala (n=7) and Ser77Tyr (n=3). The 6 clinically defined TTR cases without genetic testing were excluded. Among AL cases, monoclonal heavy chains were found in 44 cases - 7 IgA, 1 IgD, 18 IgG, and 17 IgM. Serum monoclonal light chains were found in all 60 AL cases – 16 kappa and 44 lambda. Urine monoclonal light chains were obtained in 8 patients and corroborated serum studies in all cases.

Of the 60 AL cases, 28 (47%) had biopsies showing amyloid deposits in nerve, 15 (25%) in fat, 10 (17%) in marrow, 2 (3%) in rectum and 5 (8%) in kidney. Of the 41 TTR cases, 29 (71%) demonstrated amyloid in nerve, 11 (27%) in fat, and 1 (2%) in rectum. Autonomic reflex screen (ARS) and CASS scoring were completed in all 101 subjects. Including both TTR and AL subjects, a median CASS total of 7 (mean 6.5), median CASS sudomotor of 2 (mean 1.9), median CASS vagal of 3 (mean 2.1), and median CASS adrenergic of 3 (mean 2.5) were found, indicative of severe sudomotor, cardiovagal, and adrenergic autonomic failure.

80% of patients had abnormal QSART testing of one or more body sites, most commonly at the foot. Of the 32 patients who had TST, all had abnormal QSART testing except 5, only one of which had abnormal TST results. 88% of patients had CASS vagal or CASS adrenergic scores of 2 or greater. 72% had summed CASS vagal and adrenergic of 4 or greater.

At the time of diagnosis, generalized autonomic failure (GAF) based on ARS and CASS score was seen in 88%, somatic c-fiber involvement based on history, physical exam, or QST was found in 86%, large fiber involvement based on EMG was seen in 88%, weakness based on physical exam was seen in 74%, decreased sensation based on physical exam was seen in 89%, orthostatic hypotension based on tilt table testing was found in 40%, and pain based on history was described in 67%. AL patients more often lacked clinical or neurophysiologic evidence of motor involvement than TTR cases (35% versus 15%, p=0.04). Otherwise, no distinctions based on neuropathic pattern were seen between subtypes. The analysis below is for the combined groups. The electromyographic pattern of involvement was that of length dependent peripheral neuropathy in 52%, polyradiculoneuropathy in 39%, and normal in 9%, which was not different between the AL and TTR groups.

The pattern of neuropathic involvement was as follows:

| 1. GAF plus polyneuropathy with pain | 58% |

| 2. GAF with painless polyneuropathy | 20% |

| 3. Polyneuropathy without GAF | 15% |

| 4. GAF alone | 5% |

| 5. GAF with small fiber neuropathy | 2% |

GAF characterized amyloid neuropathy, occurring in 85% of patients. GAF with generalized polyneuropathy was the most common pattern occurring in 78% of patients, most commonly with pain (58%). One in six patients (15%) had polyneuropathy without GAF.

AL versus TTR amyloidosis

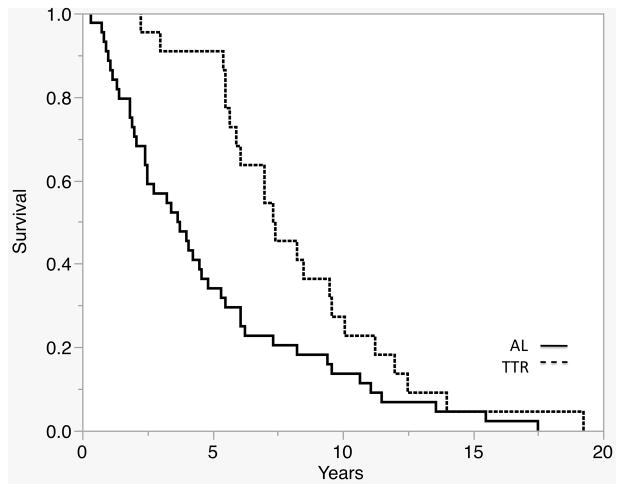

AL cases had lower rates of survival throughout the disease course than TTR cases (p=0.0006) (Fig 1). Median survival of AL cases was 44.5 months (IQR 22.5–74.0), while median survival of TTR cases was 88.5 months (IQR 65.5–114.5). Median time to diagnosis was also shorter in AL compared to TTR cases (19mos, IQR 8–30 versus 36mos, IQR 23–48, p<0.0001).

Figure 1.

TTR cases had greater survival time based on Kaplan-Meier analysis (p=0.0009).

A large majority of both AL and TTR cases had extraneural organ involvement at some point in their disease course (91% of AL cases versus 96% of TTR cases, p=0.7). However, extraneural organ involvement was more prevalent in AL cases until late stages of the disease, with median onset 5 months after AL cases (IQR 0–16) versus 24 months in TTR cases (IQR 12–34, p=0.0085). AL cases developed non-neuronal organ involvement before 12 months in 59% and before 8 months in 58% of cases, compared to 37% (p=0.03) and 27% (p=0.002), respectively, in TTR cases.

Similarly, most clinical features occurred in a similar proportion of AL and TTR cases when considering the entire disease course. However, the AL group developed several symptoms attributable to nonneuronal systemic involvement in the first year after disease onset, while the TTR group generally developed these in the second year after onset (Table 2). Specifically, fatigue (48% vs 24%, p=0.02) and weight loss (62% vs 37%, p=0.01) occurred more often in the first year after symptom onset among AL cases compared to TTR cases. Orthostatic intolerance (OI) also held to this pattern (47% vs 24%, p=0.04). OI cannot be attributed exclusively to neurologic versus nonneurologic disease – possibly resulting from involvement of autonomic nerves, heart, vasculature, or constitutional decline. However, in this study OI was found in all cases to be associated with some specific extraneural involvement.

Table 2.

Time to onset of clinical features after inaugural symptoms (months) was compared between the AL and TTR groups, as well as the proportion affected by each clinical feature at some point in the disease course.

| Time to onset (months) | Proportion affected | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AL Mean 95%CI |

TTR mean 95%CI |

p value | AL n/N % |

TTR n/N % |

p value | |

| Numbness | 5.5 2.6–8.3 |

4.90 1.6–8.1 |

0.8 | 49/60 82% |

39/41 95% |

0.07 |

| Paresthesias | 4.4 1.6–7.1 |

3.7 .4–6.9 |

0.7 | 48/60 80% |

36/41 88% |

0.4 |

| Weakness | 11.8 6.2–17.3 |

19.9 13.7–26.0 |

0.06 | 40/60 67% |

33/41 80% |

0.09 |

| Orthopnea | 7.3 −19.4–33.8 |

53.0 14.0–91.9 |

.06 | 8/60 13% |

4/41 10% |

0.8 |

| Weight loss | 8.3 3.7–12.9 |

15.5 9.1–22.0 |

.07 | 44/60 73% |

29/41 59% |

0.1 |

| Diarrhea | 9.6 3.6–15.5 |

18.9 12.0–25.7 |

0.05 | 26/60 43% |

20/40 49% |

0.7 |

| Cardiac involvement | 10.3 5.1–15.5 |

19.8 14.7–24.9 |

0.01 | 29/60 48% |

30/41 73% |

0.01 |

| Erectile dysfunction | 10.6 2.8–18.4 |

14.3 6.3–22.3 |

0.5 | 20/37 54% |

21/33 64% |

0.5 |

| Orthostatic intolerance | 11.1 5.8–16.3 |

21.6 14.4–28.8 |

0.02 | 40/60 67% |

22/41 54% |

0.2 |

| Oliguria | 16.7 3.4–29.9 |

23.7 7.6–39.7 |

0.5 | 12/60 20% |

9/41 22% |

0.8 |

| Sicca | 17.3 7.1–27.6 |

17.9 4.5–31.2 |

0.9 | 13/60 22% |

8/41 20% |

1.0 |

| Fatigue | 17.2 8.2–26.2 |

21.3 8.4–34.2 |

0.6 | 38/60 63% |

19/41 46% |

0.1 |

| Exercise intolerance | 18.0 9.1–26.9 |

19.2 7.1–31.4 |

0.9 | 38/60 63% |

25/41 51% |

0.3 |

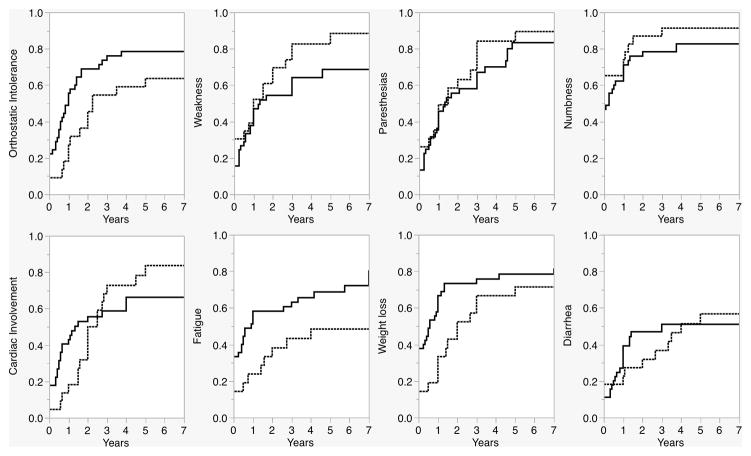

This was further illustrated by detailed chronologic analyses comparing accrual of clinical features according to their time of onset relative to inaugural features in TTR cases versus AL cases (Fig 2). The difference in prevalence of clinical features between the two groups often varied with the duration of the disease. Some clinical features did not differ significantly taken across the full arc of the disease, but the analyses suggested differences during specific time segments. For example, while cardiac involvement occurred more frequently overall in TTR (73% in TTR vs 48% in AL, p=0.01), among those who developed cardiac involvement, it occurred earlier than 8 months in 62.1% of AL cases vs 20.0% of TTR cases (p=0.001). Weight loss occurred more often among AL cases early on in the disease course (55% before one year in AL versus 34% in TTR, p=0.02), but had similar prevalence in the two groups later on and overall. Weakness occurred at a similar rate early in the disease course in the two groups, but was more prevalent later on and overall in TTR (85% in TTR versus 67% in AL, p=0.03). Paresthesias (p=0.7) and numbness (p=0.8) had similar prevalence in both AL and TTR cases at all time-points and were inaugural symptoms in a majority of patients in both groups.

Figure 2.

Accrual of clinical features, AL versus TTR. Orthostatic intolerance, fatigue, and weight loss occurred earlier in AL cases. Paresthesias and numbness occurred with equal frequency throughout the disease course in both groups. The difference in frequency of cardiac involvement, weakness, and diarrhea varied depending on the duration of disease. Generally, extraneural involvement occurs earlier in AL than TTR amyloidosis.

All inaugural clinical features occurred at similar rates in AL cases compared to TTR cases except for weight loss (35% of AL cases and 17% of TTR cases, p=0.05) and fatigue (28% of AL cases and 12% of TTR cases, p=0.05). All other features occurred as inaugural features in a similar minority of both groups, including cardiac involvement (13% of AL cases and 12% of TTR cases, p=0.9), orthostatic intolerance (20% of AL case and 10% of TTR cases, p=0.2), diarrhea (12% of AL cases and 15% of TTR cases, p=0.7), and weakness (17% of AL cases and 20% of TTR cases, p=0.7).

Compared to AL cases, electrophysiologic studies revealed more severe neuropathic changes among TTR patients in the upper limb. TTR had lower amplitude and percentile for ulnar CMAPs (p=0.003 for amplitude; p=0.008 for percentile) and median SNAPs (p=0.03 for amplitude; p=0.01 for percentile). Sural sensory and peroneal motor nerve conduction studies were not different between the two groups, largely because they were often absent (52% of peroneal CMAPs and 70% of sural SNAPs).

TTR cases had higher CASS sudomotor (2.2 versus 1.7, p=0.02) and CASS total (7.0 versus 6.2, p=0.1), though the latter difference did not attain statistical significance (Table 3). TTR cases also showed reduced distal sweat responses compared to AL (p=0.01). In contrast, AL developed symptoms or findings of orthostatic hypotension earlier than TTR (11.0 mos versus 21.6 mos, p=0.02) (Fig 2). Of note, upper limb NCS findings and CASS scores did not vary significantly with time since onset.

Table 3.

The composite autonomic severity scale (CASS) score was completed. TTR cases had higher CASS sudomotor score, which was then reflected in a slightly higher mean CASS total score. No difference was seen between the groups in CASS vagal and adrenergic scores.

| AL | TTR | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CASS vagal (max 3) | 2.1 (1.8–2.4) | 2.1 (1.8–2.4) | 0.846 |

| CASS adrenergic (max 4) | 2.5 (2.1–2.8) | 2.6 (2.2–3.0) | 0.643 |

| CASS sudo (max 3) | 1.7 (1.4–2.0) | 2.2 (1.9–2.6) | 0.024 |

| CASS total (max 10) | 6.0 (5.5–6.8) | 7.0 (6.2–7.8) | 0.110 |

Among TTR cases, all patients with Val30Met mutations reported distal paresthesias at onset, compared to only 6 of the 21 non-met30 TTR cases. Non-met30 TTR cases reported onset of paresthesias a median of 7 months after the onset of amyloid-related symptoms, (p=0.0001). Val30Met cases also had lower QSART volumes at the foot (p=0.05). Other clinical features, including survival time after symptom onset, did not differ between Val30Met and other TTR cases.

Of the 41 TTR cases, 14 reported confirmed diagnoses of amyloidosis in family members. Another 15 raised suspicion of a family history of TTR amyloidosis during their evaluations because of reported diagnoses of neuropathy, autonomic dysfunction, or early onset heart failure in family members. 11 denied any specific knowledge of family history of amyloidosis. 1 had no knowledge of family history of amyloidosis, having been adopted as an infant. Among those with confirmed, previous diagnoses of amyloidosis in family members, time to diagnosis after inaugural symptom onset was 1.0 years, compared to 3.5 years in those with suspected family history and 4.0 years in those with no suspected family history.

Markers of prognosis

Bivariate models showed the strongest relationship between survival time and time to onset of orthostatic intolerance (p≤0.0001), fatigue (p<0.0001), erectile dysfunction (p<0.0001), weight loss (p=0.003), diarrhea (p=0.006), weakness (p=0.006), and cardiac involvement (p=0.003). The weakest relationships were to time of onset of paresthesias (p=0.9) and numbness (p=0.8). Development of systemic involvement in the first year of symptoms was associated with reduced median survival time: orthostasis (2.2 years versus 7.3 years; p<0.0001), fatigue (2.5 years versus 6.6 years; p=0.0005), weight loss (2.6 years versus 7.8 years; p<0.0001), and cardiac involvement (2.4 years versus 6.2 years; p=0.007). Those developing any extraneural involvement in the first year had markedly reduced median survival time compared to those who did not (3.3 years versus 7.3 years; p<0.0001).

Those with TTR who developed weakness in the first year had shorter survival time than those who did not (82 mos versus 114 mos, p=0.05), a difference not seen among the AL patients (56 mos versus 61 mos, p=0.2). Also among TTR patients, those with onset of ED, weight loss, and/or cardiac involvement in the first year had shorter survival time. Few patients in either the TTR or AL group never developed weight loss during their clinical course, and those who did not had greatly increased survival time compared to those who did - 10.5 versus 3.6 years in the AL group (p<0.0001), and 10.0 versus 7.0 years in the TTR group (p=0.05).

Bivariate analyses revealed no relationship between serum levels of BNP, troponins, or free light chains and measures of disease severity including neurophysiologic findings and survival time. However, BNP and troponin levels were rarely measured in earlier cases, which notably make up much of the survival analyses. Furthermore, serum studies were performed at widely varying clinical time-points between patients. Weight loss was calculated using two in-house data points in 22 patients, with intervals of 12 to 72 months between measurements. Median weight loss over time did not differ between TTR (2.3 kgs/month) and AL (2.0 kgs/month) groups. More often, weight loss was reported by patients with respect to a previous baseline body weight. By definition, this was at least 10 pounds (4.5 kg) and was as much as 27.2 kg with a median of 6.8 kg. The reported degree of weight loss did not differ between AL (median 7.0 kg, range 4.5–27.2) and TTR (6.6 kg, range 4.5–22.7).

Among measures of autonomic function, CASS vagal had the strongest association with survival time – for each additional point of CASS vagal, average survival time decreased by 16 months. Patients with normal heart rate responses (CASS vagal of 0) lived an average of 10.7 years compared to 5.6 years in those with reduced heart rate responses (p=0.009). Those with absent blood pressure overshoot (phase IV) during the Valsalva maneuver survived 5.2 years compared to 7.5 years in those demonstrating a blood pressure overshoot (p=0.05). No difference in survival time was seen with increasing body percent anhidrosis as seen on TST, worsening sudomotor function as seen on QSART, or worsening findings on nerve conduction studies.

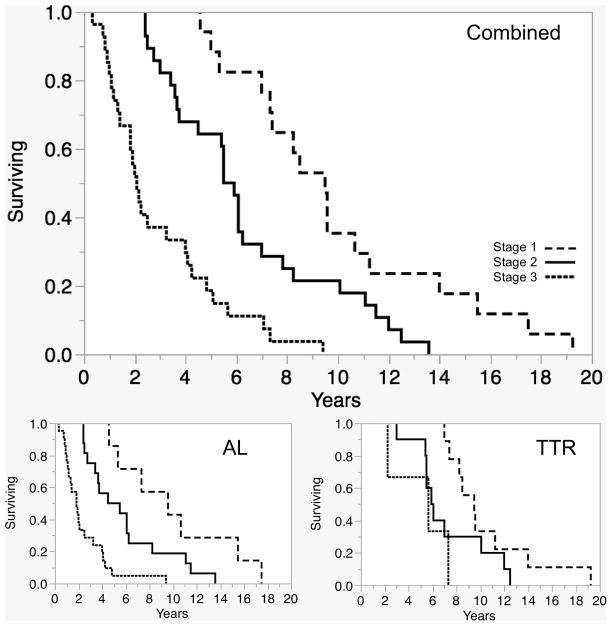

We combined the best markers of prognosis into a scoring system as follows: 1 point is awarded for occurrence within one year of onset of symptoms of 1) cardiac involvement, 2) weight loss, 3) orthostatic intolerance, and 4) fatigue. Median survival of patients found to have none of these (Stage I) was 9.5 years; of those with 1 or 2 of these clinical features (Stage II) was 5.7 years; and of patients with 3 or 4 (Stage III) features median survival was 2.0 years (p<0.0001) (Table 4). Of note, none of those with Stage I died within 4 years of onset, none of those with Stage II died within 2 years of onset, and 70% of patients with Stage III died within 4 years of onset. Higher stages were associated with poorer prognosis in both AL (p<0.0001) and TTR cases (p=0.05). Median survival time of patients with 0 points was similar in the AL and TTR groups (9.6 vs 9.5 years).

Table 4.

Survival time was compared between those developing key prognostic clinical features less than 1 year and greater than 1 year after onset of inaugural amyloid-related symptoms. A staging system assigned 1 point for each of feature developing in the first year, and categorized patients as Stage I for zero points, Stage II for 1–2 points, and Stage III for 3–4 points. The staging predicted reduced survival for Stage II compared to Stage I, and in turn Stage II compared to Stage II. This relationship held true for the AL and TTR groups when analyzed together and separately (Fig 3).

| Survival time in years – Median (IQR) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AL | TTR | |||||

| 1 point each if onset <1yr: | Onset <1yr | Onset >1yr | p-value | Onset <1yr | Onset >1yr | p-value |

| Cardiac involvement | 2.0 (1.3–4.1) n=18 |

4.5 (2.5–8.3) n=26 |

0.03 | 5.8 (3.0–7.9) n=7 |

7.8 (5.9–10.3) n=21 |

0.3 |

| Weight loss | 2.4 (1.3–4.3) n=30 |

6.7 (4.6–10.7) n=14 |

0.0005 | 5.6 (4.6–8.0) n=6 |

8.3 (6.3–11.8) n=16 |

0.09 |

| Orthostatic intolerance | 2.0 (1.1–3.8) n=24 |

6.2 (4.1–10.9) n=20 |

<0.0001 | 5.9 (4.0–9.7) n=5 |

8.3 (5.8–10.7) n=17 |

0.3 |

| Fatigue | 2.1 (1.3–4.0) n=25 |

6.1 (3.8–9.6) n=19 |

0.0004 | 7.0 (4.3–9.9) n=5 |

8.3 (5.7–10.7) n=17 |

0.4 |

| Stage I (0 points) | 9.6 (5.3–15.5) | <0.0001 | 9.5 (7.8–12.6) | 0.05 | ||

| Stage II (1–2 points) | 5 (3.1–7.3) | 6.0 (5.5–10.6) | ||||

| Stage III (3–4 points) | 1.8 (1.1–3.3) | 5.7 (2.3–7.3) | ||||

Limitations

The weaknesses of this study largely stem from its intrinsic limitations as a retrospective analyses. Identification of clinical features was dependent on the documentation of different clinicians over time. The study by necessity used an approximation of the time of onset of clinical features based on patients’ and physicians’ recollection as represented in the medical record. Bias may have been introduced by the lack of a fixed protocol for the clinical history documented. The Mayo neurologic examination is standardized and semi-quantitative (0–4 from normal to maximal deficit). However, the criteria for identifying clinical features and their time of onset in the medical record were well defined for this review, and were applied evenly in all cases. Furthermore, evaluations may have been performed at varying disease stages. However, the differences noted remain significant when controlling for time since inaugural symptom onset. Similarly, follow up of patients could not be standardized. Patients were excluded from the study if follow up did not continue to within at least the last year of life, possibly introducing inclusion bias.

This study aimed to examine the natural history of amyloid neuropathy. Therefore, patients having received definitive treatments such as bone marrow or liver transplant were not included, possibly introducing selection bias. As a retrospective study, it was not possible to control for the details of oral treatment regimens – their doses and durations of use. For example, some patients received oral corticosteroids, but the dosage, the time taken and compliance varied widely and were often not certain from the medical record. For this reason, a meaningful analysis of treatment effect could not be included.

Discussion

In this paper, we use a retrospective cohort model to contrast the phenotype and clinical history of AL and TTR amyloid neuropathy, and demonstrate several key differences. The key findings are that TTR amyloid neuropathy is associated with longer survival, earlier autonomic and somatic nerve involvement but later extraneural amyloid burden. The worse prognosis in AL amyloid neuropathy seems to be related to the earlier onset and progression of extraneural involvement of organs such as gastrointestinal tract, heart, liver and kidneys. We identify a clinical phenotype that segregates amyloid neuropathy from other neuropathies and features with prognostic value in both amyloid subtypes. Finally, we identify how the clinical features associated with each subtype might contribute to subtype-specific prognosis.

Existing literature has stated that amyloid neuropathy subtypes cannot be distinguished based on clinical phenotype alone, and that laboratory analysis of in situ amyloid deposits is necessary for diagnosis.4, 39–44 However, absent from prior studies have been systematic subtype comparisons which include chronologic sequencing of clinical features. From such a detailed historical evaluation in this study, distinctions between the subtypes emerged. Most notably, compared with AL cases, TTR cases had longer survival after onset, longer time to diagnosis and delayed non-neuronal systemic involvement; they paradoxically had more severe autonomic failure and pan-neuronal involvement. As has been reported in past retrospective studies, we found the prevailing pattern of neuropathic involvement to be similar for AL and TTR amyloid - most commonly distal, symmetric, sensory predominant neuropathy with paresthesias and/or numbness and autonomic involvement, followed by progression and development of motor neuronal and systemic non-neuronal involvement.5, 12, 15, 21, 45–47 However, through evaluating chronologic time of onset of clinical features, we find that pan-neuronal involvement occurs earlier and more often in TTR cases than in AL cases, in particular motor nerve involvement. Conversely, non-neuronal organ involvement in the first year after onset was more often seen in AL cases than TTR cases.

One striking feature discovered was the significant increase in time to diagnosis in TTR cases. Other results of the review might offer some explanation of this. Early in the disease course, symptoms in TTR cases were often limited to those of common length dependent sensory motor polyneuropathy – numbness, paresthesias, and mild distal weakness. In the absence of the systemic hallmark features of amyloidosis – diarrhea, weight loss, generalized autonomic failure, cardiomyopathy and vasculopathy – the clinical presentation is commonly mistaken for more common conditions such as diabetic neuropathy or chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy (CIDP).

While autonomic failure does little to distinguish TTR from AL amyloid neuropathy, both this study and our early study21 highlight the importance of generalized autonomic failure in the neuropathy phenotype. In both TTR and AL amyloid neuropathy GAF is present on evaluation in almost 90% of patients with amyloid neuropathy, and some degree of autonomic dysfunction is nearly universal. Absence of significant autonomic failure predicts that there is >90% chance that this neuropathy is not due to amyloid.

We identified 4 markers (cardiac involvement; weight loss; orthostatic intolerance; fatigue) that in combination were highly predictive of survival. Using these 4 markers, we generated a scale for use in predicting survival time. The scale can serve as a useful bedside tool to gauge prognosis at the time of a patient’s first presentation in the clinic. The four clinical features used can all be gathered through an appropriate clinical history together with an echocardiogram. Of note, since each feature has prognostic value for both AL and TTR subtypes, the scale remains useful both with and without a known amyloid subtype. Since diagnosis of amyloid subtypes remains challenging even with optimal use of current diagnostic strategies, the scale can be uniquely versatile as a prognostic tool which can be used to inform clinical outlook both at the time of initial presentation and after a definitive diagnosis has been made. The scale offers the greatest prognostic certainty when either none or 3 to 4 of the clinical features are present – a wider range of survival times are seen in patients with only 1 or 2 of the clinical features.

While the mechanism of poorer prognosis in subjects with earlier organ involvement is unproven, there is some support for the notion that this dire prognosis is related to more aggressive amyloid infiltration, and subsequently greater amyloid burden in the organs. For example, TTR patients who progressed to develop motor nerve involvement earlier were found to have poorer prognosis. This is not likely due to a greater risk of mortality intrinsic to motor deficits, but rather suggests that TTR cases with earlier panneuronal spread of amyloid are also more likely to have early end organ involvement. Indeed, earlier onset of weakness was associated with earlier onset of non-neuronal involvement and shorter survival time in TTR cases, a relationship not seen in AL cases.

The increased survival time seen in TTR cases may relate to the predilection of TTR amyloidosis for neuronal rather than systemic involvement early in the disease course. Similarly, the greater abnormalities seen on nerve conduction studies and QSART in TTR cases suggest a more diffuse intraneural distribution of the pathologic effects of TTR amyloidosis than in AL amyloidosis. This might also be reflected by AL amyloid more commonly showing isolated sensory and autonomic abnormalities, suggesting pathology more often limited to the dorsal root ganglia. Conversely, the greater prominence of constitutional symptoms in AL amyloid likely relates to more widespread amyloid deposition, as well as systemic or paraneoplastic effects of the underlying plasma cell dyscrasia.

Figure 3.

Survival in years (KM analysis) was reduced with higher stages (see Table 4), both in the group as a whole and when considering AL and TTR groups separately.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health (NS 44233 Pathogenesis and Diagnosis of Multiple System Atrophy, U54 NS065736 Autonomic Rare Disease Clinical Consortium, K23NS075141 Differential Approach to the Postural Tachycardia Syndrome (Singer), Mayo CTSA (UL1 TR000135), and Mayo Funds.

The Autonomic Diseases Consortium is a part of the NIH Rare Diseases Clinical Research Network (RDCRN). Funding and/or programmatic support for this project has been provided by U54 NS065736 from the National Institute of Neurological Diseases and Stroke (NINDS) and the NIH Office of Rare Diseases Research (ORDR).

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Author Contributions

AJL, PAL, and WS contributed to concept and design.

AJL, PAL, WS, MLM, PS, and MG contributed to data acquisition and analysis.

AJL and WS contributed to drafting of manuscript and figures.

Potential Conflicts of Interest

The authors have nothing to report.

References

- 1.Kyle A, Kelly JJ, Dyck PJ. Amyloidosis and neuropathy. In: Dyck PJ, editor. Peripheral Neuropathies. Vol. 2. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2005. pp. 2427–2451. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benson MD, Kincaid JC. The molecular biology and clinical features of amyloid neuropathy. Muscle Nerve. 2007;36:411–423. doi: 10.1002/mus.20821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andrade C. A peculiar form of peripheral neuropathy: familial atypical generalized amyloidosis with special involvement of peripheral nerves. Brain. 1952;75:408–427. doi: 10.1093/brain/75.3.408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adams D. Hereditary and acquired amyloid neuropathies. J Neurol. 2001;248:647–657. doi: 10.1007/s004150170109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kyle RA, Gertz MA. Primary systemic amyloidosis: clinical and laboratory features in 474 cases. Semin Hematol. 1995;32:45–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kyle RA, Greipp PR. Amyloidosis: clinical and laboratory features in 229 cases. Mayo Clin Proc. 1983;58:665–683. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kyle RA, Greipp PR, O’Fallon WM. Primary systemic amyloidosis: multivariate analysis for prognostic factors in 168 cases. Blood. 1986;68:220–224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carrwik C, Stenevi U. Lattice corneal dystrophy, gelsolin type (Meretoja’s syndrome) Acta Ophthalmol. 2009;87:813–819. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.2009.01686.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Luttmann RJ, Teismann I, Husstedt IW, Ringelstein EBKG. Hereditary amyloidosis of the Finnish type in a German family: clinical and electrophysiological presentation. Muscle Nerve. 2010;41:679–684. doi: 10.1002/mus.21534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Joy T, Wang J, Hahn A, Hegele RA. APOA1 related amyloidosis: a case report and literature review. Clin Biochem. 2003;36:641–645. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9120(03)00110-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bellotti V, Mangione P, Merlini G. Review: immunoglobulin light chain amyloidosis--the archetype of structural and pathogenic variability. J Struct Biol. 2000;130:280–289. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.2000.4248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koike H, Tanaka F, Hashimoto R, et al. Natural history of transthyretin Val30Met familial amyloid polyneuropathy: analysis of late-onset cases from non-endemic areas. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2012;83:152–158. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2011-301299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Said G, Plante-Bordeneuve V. Familial amyloid polyneuropathy: a clinico-pathologic study. J Neurol Sci. 2009;284:149–154. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2009.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dyck PJ, Lambert EH. Dissociated sensation in amylidosis. Compound action potential, quantitative histologic and teased-fiber, and electron microscopic studies of sural nerve biopsies. Arch Neurol. 1969;20:490–507. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1969.00480110054005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kelly JJ, Jr, Kyle RA, OBrien PC, Dyck PJ. The natural history of peripheral neuropathy in primary systemic amyloidosis. Ann Neurol. 1979;6:1–7. doi: 10.1002/ana.410060102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ladha SS, Dyck PJ, Spinner RJ, et al. Isolated amyloidosis presenting with lumbosacral radiculoplexopathy: description of two cases and pathogenic review. J Peripher Nerv Syst. 2006;11:346–352. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8027.2006.00107.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Laeng RH, Altermatt HJ, Scheithauer BW, Zimmermann DR. Amyloidomas of the nervous system: a monoclonal B-cell disorder with monotypic amyloid light chain lambda amyloid production. Cancer. 1998;82:362–374. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19980115)82:2<375::aid-cncr18>3.0.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pizov G, Soffer D. Amyloid tumor (amyloidoma) of a peripheral nerve. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1986;110:969–970. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Porchet F, Sonntag VK, Vrodos N. Cervical amyloidoma of C2. Case report and review of the literature. Spine. 1998;23:133–138. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199801010-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tracy JA, Dyck PJ, Dyck PJ. Primary amyloidosis presenting as upper limb multiple mononeuropathies. Muscle Nerve. 2010;41:710–715. doi: 10.1002/mus.21561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang AK, Fealey RD, Gehrking TL, Low PA. Patterns of neuropathy and autonomic failure in patients with amyloidosis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2008;83:1226–1230. doi: 10.4065/83.11.1226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Plante-Bordeneuve V, Said G. Familial amyloid polyneuropathy. Lancet Neurol. 2011;10:1086–1097. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(11)70246-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang NC, Lee MJ, Chao CC, et al. Clinical presentations and skin denervation in amyloid neuropathy due to transthyretin Ala97Ser. Neurology. 2010;75:532–538. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181ec7fda. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Benson MD, Cohen AS. Generalized amyloid in a family of Swedish origin. A study of 426 family members in seven generations of a new kinship with neuropathy, nephropathy, and central nervous system involvement. Ann Intern Med. 1977;86:419–424. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-86-4-419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Plante-Bordeneuve V, Ferreira A, Lalu T, et al. Diagnostic pitfalls in sporadic transthyretin familial amyloid polyneuropathy (TTR-FAP) Neurology. 2007;69:693–698. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000267338.45673.f4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tincani G, Hoti E, Andreani P, et al. Operative risks of domino liver transplantation for the familial amyloid polyneuropathy liver donor and recipient: a double analysis. Am J Transplant. 2011;11:759–766. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03477.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Takei Y, Ikeda S, Ikegami T, et al. Ten years of experience with liver transplantation for familial amyloid polyneuropathy in Japan: outcomes of living donor liver transplantations. Intern Med. 2005;44:1151–1156. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.44.1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Herlenius G, Wilczek HE, Larsson M, et al. Ten years of international experience with liver transplantation for familial amyloidotic polyneuropathy: results from the Familial Amyloidotic Polyneuropathy World Transplant Registry. Transplantation. 2004;77:64–71. doi: 10.1097/01.TP.0000092307.98347.CB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stangou AJ, Hawkins PN, Heaton ND, et al. Progressive cardiac amyloidosis following liver transplantation for familial amyloid polyneuropathy: implications for amyloid fibrillogenesis. Transplantation. 1998;66:229–233. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199807270-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Olofsson BO, Backman C, Karp K, Suhr OB. Progression of cardiomyopathy after liver transplantation in patients with familial amyloidotic polyneuropathy, Portuguese type. Transplantation. 2002;73:745–751. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200203150-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yazaki M, Mitsuhashi S, Tokuda T, et al. Progressive wild-type transthyretin deposition after liver transplantation preferentially occurs onto myocardium in FAP patients. Am J Transplant. 2007;7:235–242. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01585.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Suanprasert N, Berk JL, Benson MD, et al. Retrospective study of a TTR FAP cohort to modify NIS+7 for therapeutic trials. J Neurol Sci. 2014;344:121–128. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2014.06.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Desai HV, Aronow WS, Peterson SJ, Frishman WH. Cardiac amyloidosis: approaches to diagnosis and management. Cardiol Rev. 2010;18:1–11. doi: 10.1097/CRD.0b013e3181bdba8f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Esplin BL, Gertz MA. Current trends in diagnosis and management of cardiac amyloidosis. Curr Probl Cardiol. 2013;38:53–96. doi: 10.1016/j.cpcardiol.2012.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gertz MA. Immunoglobulin light chain amyloidosis: 2013 update on diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment. Am J Hematol. 2014;88:416–425. doi: 10.1002/ajh.23400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dyck PJ, O’Brien PC, Litchy WJ, et al. Use of percentiles and normal deviates to express nerve conduction and other test abnormalities. Muscle Nerve. 2001;24:307–310. doi: 10.1002/1097-4598(200103)24:3<307::aid-mus1000>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Low PA. Composite autonomic scoring scale for laboratory quantification of generalized autonomic failure. Mayo Clin Proc. 1993;68:748–752. doi: 10.1016/s0025-6196(12)60631-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Low PA, Denq JC, Opfer-Gehrking TL, et al. Effect of age and gender on sudomotor and cardiovagal function and blood pressure response to tilt in normal subjects. Muscle Nerve. 1997;20:1561–1568. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4598(199712)20:12<1561::aid-mus11>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Klein CJ, Vrana JA, Theis JD, et al. Mass spectrometric-based proteomic analysis of amyloid neuropathy type in nerve tissue. Arch Neurol. 2011;68:195–199. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2010.261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lachmann HJB, DR, Booth SE, Bybee A, et al. Misdiagnosis of hereditary amyloidosis as AL (primary) amyloidosis. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1786–1791. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa013354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kisilevsky R. Amyloids: tombstones or triggers? Nat Med. 2000;6:633–634. doi: 10.1038/76203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Thomas PK, King RH. Peripheral nerve changes in amyloid neuropathy. Brain. 1974;97:395–406. doi: 10.1093/brain/97.1.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vrana JA, Gamez JD, Madden BJ, et al. Classification of amyloidosis by laser microdissection and mass spectrometry-based proteomic analysis in clinical biopsy specimens. Blood. 2009;114:4957–4959. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-07-230722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang AK. Amyloid neuropathy: a peculiar form of peripheral neuropathy. Arch Neurol. 2001;58:822–823. doi: 10.1001/archneur.58.5.822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Adams D, Lozeron P, Theaudin M, et al. Varied patterns of inaugural light-chain (AL) amyloid polyneuropathy: a monocentric study of 24 patients. Amyloid. 2011;18:98–100. doi: 10.3109/13506129.2011.574354036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Adams D, Coelho T, Obici L, et al. Rapid progression of familial amyloidotic polyneuropathy: a multinational natural history study. Neurology. 2015;85:675–682. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mariani LL, Lozeron P, Théaudin M, et al. Genotype-phenotype correlation and course of transthyretin familial amyloid polyneuropathies in France. Ann Neurol. 2015;78:901–916. doi: 10.1002/ana.24519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]