Abstract

There is a rising incidence of early cervical cancer in young patients as a result of screening and early detection. Treatment of cervical cancer by surgery or radiotherapy results in permanent infertility which affects the quality of life of cancer survivors. Now with improved survival rates among early cervical cancer patients, conservative surgery aiming at fertility preservation in those desiring future pregnancy is an accepted treatment. Conservative surgery is possible in early cervical cancer including micro invasive cancer and stage IB cancers less than 2 cm. Stage IA1 cervical cancer is treated effectively by cervical conisation. In stage IA2 cancers and stage IB1 cancers less than 2 cm the fertility preservation surgery is radical trachelectomy. Radical trachelectomy removes the cervix with medial parametrium and upper 2 cm vaginal cuff retaining the uterus and adnexa to allow future pregnancy. Radical trachelectomy is a safe procedure in selected patients with cancer cervix with acceptable oncologic risks and promising obstetric outcome. It should be avoided in tumours larger than 2 cm and aggressive histologic types. This article focuses on the current options of conservative surgery in early cervical cancer.

Keywords: Conservative surgery, Cancer cervix, Radical trachelectomy, Fertility preservation

Introduction

Cervical cancer still continues to be the major tumour burden in developing countries including India. Developed countries have conquered the menace of cervical cancer by proper screening and vaccination but this has not happened in India. In India it is the second common female cancer and is the second common female cancer in women aged 20–44 years [1]. Many of these young patients are nulliparous when they are diagnosed with cancer, may be due to falling fertility rates in India combined with the recent trend of delaying pregnancy compared to older times [2]. Early stage cervical cancer is defined by FIGO as stage IA to IB1 disease [3]. The standard treatment of early cervical cancer is radical hysterectomy or radiotherapy both of which result in permanent infertility. Early cervical cancer whatever be the treatment modality, has cure rates ranging from 90 to 100 %. So these patients go on to live a long life of infertility with associated grief, depression, psychosocial dysfunctions which affect their quality of life [4]. This made people question the rationale of doing extensive surgery for all cases of cancer cervix and look into the possibility of performing conservative surgeries in nulliparous patients without compromising her cure.

The logic of reducing radicality of surgery without compromising its oncological outcome has been applied in many cancers including breast cancer. Breast cancer surgery which started as radical mastectomy has now changed to breast conservative surgery combined with radiotherapy. Same trend has occurred in vulval cancer. Surgical incision for vulval cancer used to be the large butterfly shaped incision combining radical vulvectomy and groin node dissection. Now vulval cancers are treated by wide excision combined with sentinel node dissections. Similarly cervical cancers can also be managed conservatively by radical local excision combined with pelvic lymphadenectomy. The uterine corpus can be preserved to allow future child bearing.

Cervical Conisation

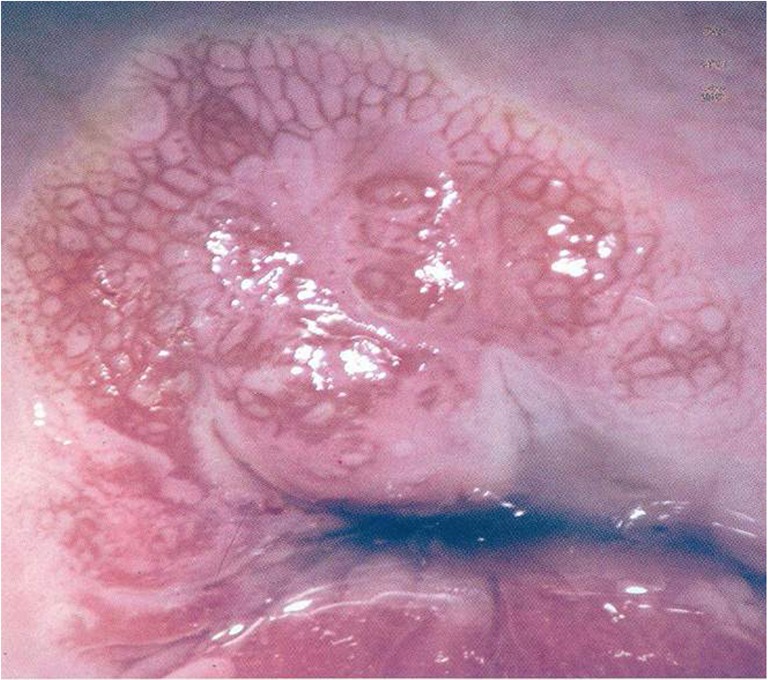

The conservative surgery possible depends on the stage of the disease which can be determined by proper clinical examination and if needed colposcopy and guided biopsies. When there is no gross tumour in the cervix colposcopy helps in identifying microinvasive cancers (Fig.1). Stage IA1 is tumour involving less than 3 mm of cervical stroma and is managed by cervical conisation in the absence of lymphvascular space invasion in the biopsy specimen. Lymphvascular invasion predisposes to lymphnode metastasis and needs conisation combined with bilateral pelvic lymph node dissection. Conisation removes a cone shaped portion of cervix with the base of the cone in the ectocervix and apex 1 cm from internal os in the endocervical canal. The procedure when done with scalpel is called cold knife conisation. Conisation can also be done using LASER or with electrosurgical loops. The electro surgical excision is called Loop Electro surgical Excision Procedure (LEEP) which is the most popular method of conisation. Cold knife conisation requires general anaesthesia and is associated with increased bleeding. LASER conisation can be done with exact precision but the laser machines being costly and unavailable makes the procedure less popular in developing countries including India.

Fig. 1.

Colposcopic magnified view (X15) of microinvasive cancer showing abnormal vasculature

LEEP conisation is done using loop electrodes made of stainless steel or tungsten wires activated by electric current from an electrosurgical generator (Fig.2). This is done under local anaesthesia and can be used for conisation upto 1.5 cm into endocervical canal. Equipments needed for LEEP include an electro surgical unit, colposcope and a smoke evacuator. Patient in placed in modified lithotomy position, cervix is exposed with insulated speculum. Colposcopy is done to delineate the lesion (Fig.3).Local anaesthesia is given intracervically with xylocaine. Using the activated loop a cone shaped portion of cervix is excised. Figure 4 shows LEEP excision specimen. Hemostasis is attained using ball electrodes by fulgeration, which sprays current to the crater.

Fig. 2.

LEEP electrodes – Loop electrodes for cutting, ball and needle electrodes for coagulation

Fig. 3.

Colposcopic view of cervix with microinvasive cancer

Fig. 4.

LEEP excision specimen

LEEP is a simple and safe procedure with good social acceptance. This is done as an out patient procedure and patients are sent home after 1–2 hr of observation. Complications of LEEP include bleeding, vaginal burns and infection. Bleeding is usually controlled by dessication and fulgeration and for uncontrolled bleeding figure of eight sutures are put on the cervix. Bleeding can also occur 4–6 days after treatment which is usually due to infective etiology and are treated by antibiotics.

Cure rates of conisation for early cancer cervix are very good and comparable with hysterectomy [5].Longterm complications include infertility due to cervical stenosis and deficient cervical mucous. Due to shortened cervix cervical incompetence can also occur leading on to preterm labour and premature rupture of membranes [6].

Radical Trachelectomy

The conservative surgery possible from Stage IA2 onwards is radical trachelectomy which can be done for cervical cancers upto stage IB1 tumours less than 2 cm. Radical trachelectomy means removing the cervix with parametrium and upper vagina retaining uterus to allow future child bearing. Radical trachelectomy was first performed in 1986 by Daniel Dargent and hence is also known as Dargent’s operation. Radical trachelectomy is traditionally performed by vaginal route but can also be performed by abdominal route and now laparoscopic and robotic.

Eligibility Criteria

Indications for radical trachelectomy have not changed since Roy and Plante published their case series in 1988 [7]. The patient selected for radical trachelectomy should have a keen desire for pregnancy. She should ideally be less than 40 years with no infertility issues. Preoperative MRI is done to assess the tumour location and extent. The tumour size should be less than 2 cm with limited endocervical extension and there should be no pelvic lymphnode metastasis [8]. Lymph vascular space invasion is also an adverse prognostic factor in early cancer cervix and hence a relative contraindication for radical trachelectomy [9].

Procedure

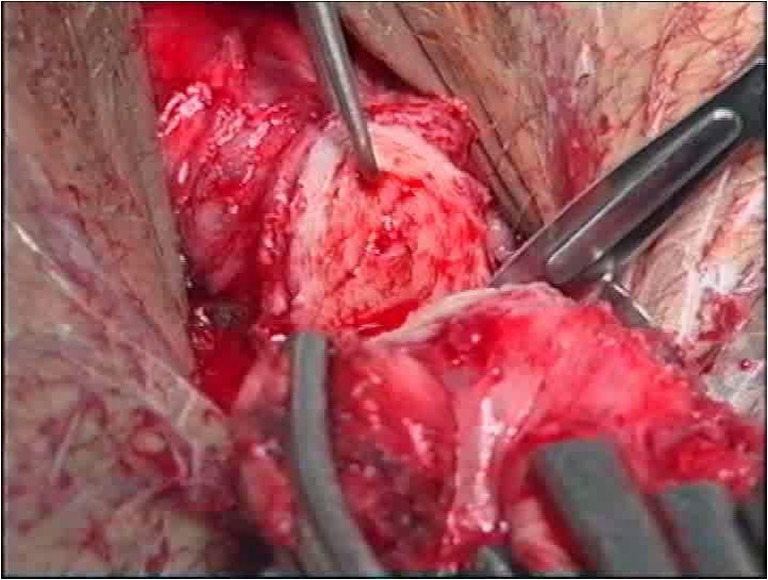

Radical trachelectomy removes the cervix with the parametrium and upper vaginal cuff similar to radical hysterectomy at the same time retaining the uterus and adnexa. The surgery starts with pelvic lymph node dissection. The lymph nodes are sent for frozen section study and if nodes do not show metastatic tumour, surgeon proceeds with radical trachelectomy. Circumferential vaginal incision is made in the upper vagina 2–3 cm from cervico vaginal junction. Bladder is separated anteriorly, para vesical spaces are developed on either side of bladder, ureters are palpated in the bladder pillar. Posteriorly rectum is dissected free and para rectal spaces are developed on either side of rectum. Vaginal branch of uterine artery is identified and ligated. Cervix is transected 1 cm below the internal os keeping at least 1 cm margin from the upper limit of the tumour(Fig.5). The specimen is sent for frozen section study to confirm adequate clearance. Figure 6 shows radical trachelectomy specimen with vaginal cuff and parametrium. Cerclage sutures are put on the cervical stump with non absorbable suture material to ensure cervical competence in future pregnancy. The vaginal cut ends are sutured to the cervical stump and foleys catheter is inserted in the uterine cavity to prevent cervical stenosis.

Fig. 5.

Radical trachelectomy - cervix with parametrium is excised from uterus

Fig. 6.

Radical trachelectomy specimen showing cervix with tumour, vaginal cuff and parametrium

Abdominal Radical Trachelectomy

In pediatric patients and when the cervical anatomy is distorted due to various reasons abdominal approach is preferred for radical trachelectomy [10]. Radical trachelectomy can also be performed by laparoscopic or robotic surgery.

Obstetric Considerations After Radical Trachelectomy

Radical trachelectomy shortens the cervix hence there is risk of cervical incompetence and premature delivery. Patient is advised contraception for 6–12 months to allow healing of neo cervix. Prophylactic antibiotics are advisable during third trimester to prevent ascending infections. Delivery is always through classical caesarian section [11].

Surgical Morbidity

Literature reports surgical morbidity after radical trachelectomy to be in par with radical hysterectomy in terms of blood loss, hospital stay and peri operative complications [12, 13]. Long term complications include cervical stenosis resulting in infertility, increased vaginal discharge and pregnancy complications like cervical incompetence, preterm labour and premature rupture of membranes. Infertility rates following radical trachelectomy range from 15 to 30% [14, 15].

Oncologic Outcome

The reported recurrence rates following radical trachelectomy is less than 5 % which is comparable with that of radical hysterectomy. The risk factors for recurrence includes tumour size more than 2 cm, presence of lymphvascular space invasion and unfavorable histology like small cell carcinoma cervix [16–19].

Pregnancy Outcome

Pregnancy outcome of patients who attempted conception after radical trachelectomy was 80 % and the possibility of having a live birth is 65 %. Cubal et al. reported 436 pregnancies after radical trachelectomy with 205 full term live births with preterm labour rate of 28% [20]. The causes of late abortions are cervical incompetence, subclinical infections and reduced mucous secretion. These can be prevented to some extent by cervical cerclage and antibiotics. Despite the high rate of pregnancy related complications the live birth rate is promising [21].

Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy

Cervical tumours more than 2 cm carry a recurrence rate 15–20 % after radical trachelectomy and hence may benefit from neoadjuvant chemotherapy to reduce the tumour volume [22, 23]. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by fertility preservation surgery looks promising but carries the risk of gonadal toxicity and resultant ovarian failure Hence this approach needs further investigation regarding its safety and oncological outcomes.

Ovarian Preservation

Ovary is a rare site of metastasis for cervical cancer. The incidence of ovarian metastasis is 0.5 % for squamous cell carcinoma and 1.7 % for adeno carcinoma cervix [24]. Hence ovarian preservation is a viable option in young patients with cancer cervix. Ovaries are transposed to paracolic gutters to protect from radiation. This will help to preserve fertility as well as the hormonal function [25–27].

Conclusion

Fertility sparing surgery may be an option for early-stage cervical cancer in patients desiring future pregnancy. Fertility preserving surgeries are deviations from the standard of care and hence patients should be carefully selected and extensively counseled regarding the oncologic risks and the subsequent pregnancy related problems.

References

- 1.Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Ervik M, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C, Rebelo M, Parkin DM, Forman D, Bray F. GLOBOCAN 2012 v1.0, Cancer Incidence and Mortality Worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBACON 2012: Int J Cancer 2015;136:(5) E359–86 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Dhillon PK, Yeole BB, Dikshit R, Kurkure AP, Bray F. Trends in Breast, Ovarian and Cervical Cancer Incidence in Mumbai, India over a 30-Year Period, 1976–2005: An age–Period–Cohort Analysis. Br J Cancer. 2011;105:723–730. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pecorelli S. Revised FIGO Staging for Carcinoma of the Vulva, Cervix, and Endometrium. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2009;105:103. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2009.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carter J, Rowland K, Chi D, et al. Gynecologic Cancer Treatment and the Impact of Cancer-Related Infertility. Gynecol Oncol. 2005;97:90. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2004.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wright JD, NathavithArana R, Lewin SN, et al. Fertility-Conserving Surgery for Young Women with Stage IA1 Cervical Cancer: Safety and Access. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115:585. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181d06b68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gay C., Grisey A. Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN2+) management: post treatment complications. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics. 2009;107(2):S31. doi: 10.1016/S0020-7292(09)60124-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roy M, Plante M. Pregnancies After Radical Vaginal Trachelectomy for Early-Stage Cervical Cancer. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;179:1491. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9378(98)70014-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sonoda Y, Abu-Rustum NR, Gemignani ML, et al. A Fertility-Sparing Alternative to Radical Hysterectomy: How Many Patients may be Eligible? Gynecol Oncol. 2004;95:534. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2004.07.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morice P, Piovesan P, Rey A, et al. Prognostic Value of Lymphvascular Invasion Determined in Hematoxilin – Eosin Staining in Early Stage Cervical Carcinoma: Resultsof a Multivariate Analysis. Ann Oncol. 2003;14:1511–1517. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdg412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boss EA, van Golde RJ, Beerendonk CC, Massuger LF. Pregnancy After Radical Trachelectomy: A Real Option? Gynecol Oncol. 2005;99:S152. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2005.07.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pareja R, Rendón GJ, Sanz-Lomana CM, et al. Surgical, Oncological, and Obstetrical Outcomes After Abdominal Radical Trachelectomy - a Systematic Literature Review. Gynecol Oncol. 2013;131:77. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2013.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dursun P., LeBlanc E., Nogueira M. C. Radical vag Inal Trachelec Tomy (Dargent’s op Eration): a Critical Review of the Literature. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2007;33:933. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2006.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alexander-Sefre F., Chee N., Spencer C., et al. Surgical morbidity associated with radical trachelectomy and radical hysterectomy. Gynecol Oncol. 2006;101:450. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2005.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Selo-Ojeme DO, Ind T, Shepherd JH. Isthmic Stenosis Following Radical Trachelectomy. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2002;22:327. doi: 10.1080/01443610252971302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shepherd JH, Spencer C, Herod J, et al. Radical Vaginal Trachelectomy as a Fertility Sparing Procedure in Women with Early Stage Cervical Cancer – Cumulative Pregnancy Rate in a Series of 123 Women. Bjog. 2006;113:719. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2006.00936.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shepherd JH, Mould T, Oram DH. Radical Trachelectomy in Early Stage Carcinoma of the Cervix: Outcome as Judged by Recurrence and Fertility Rates. Bjog. 2001;108:882. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2001.00212.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marchiole P, Benchaib M, Buenerd A, et al. Oncological Safety of Laparoscopic-Assisted Vaginal Radical Trachelectomy (LARVT or Dargent's Operation): a Comparative Study with Laparoscopic-Assisted Vaginal Radical Hysterectomy (LARVH) Gynecol Oncol. 2007;106:132. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2007.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Plante M. Evolution in Fertility-Preserving Options for Early-Stage Cervical Cancer: Radical Trachelectomy, Simple Trachelectomy, Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2013;23:982. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0b013e318295906b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Plante M, Gregoire J, Renaud MC, Roy M. The Vaginal Radical Trachelectomy: An Update of a Series of 125 Cases and 106 Pregnancies. Gynecol Oncol. 2011;121:290. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2010.12.345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ribeiro Cubal AF, Ferreira Carvalho JI, Costa MF, et al. Fertility Sparing Surgery for Early-Stage Cervical Cancer. Int J Surg Oncol. 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Pareja R, Rendon GJ, Sanz-Lomana CM, Monzon O, Ramirez PT. Surgical, Oncological, and Obstetrical Outcomes After Abdominal Radical Trachelectomy: A Systematic Literature Review. Gynecol Oncol. 2013;131:77–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2013.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Plante M, Lau S, Brydon L, et al. Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy Followed by Vaginal Radical Trachelectomy in Bulky Stage IB1 Cervical Cancer: Case Report. Gynecol Oncol. 2006;101:367. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2006.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marchiole P, Tigaud JD, Costantini S, et al. Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy and Vaginal Radical Trachelectomy for Fertility-Sparing Treatment in Women Affected by Cervical Cancer (FIGO Stage IB-IIA1) Gynecol Oncol. 2011;122:484. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sutton GP, Bundy BN, Delgado G, Sevin BU, Greasman WT, Major FJ, et al. Ovarian Metastases in Stage IB Carcinoma of the Cervix: A Gynecologic Oncology Group Study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1992;166:50–53. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(92)91828-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McCall ML, Keaty EC, Thompson JD. Conservation of Ovarian Tissue in the Treatment of Carcinoma of the Cervix with Radical Surgery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1958;75:590–605. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(58)90614-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mann WJ, Chumas J, Amalfitano T, et al. Ovarian metastases from stage IB adenocarcinoma of the cervix. Cancer. 1987;60:1123. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19870901)60:5<1123::AID-CNCR2820600534>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tabata M, Ichinoe K, Sakuragi N, et al. (1986) Incidence of Ovarian Metastasis in Patients with Cancer of the Uterine Cervix. Gynecol Oncol 1987;28(3):255–61 [DOI] [PubMed]