Abstract

It is currently known that colorectal cancers (CRC) arise from 3 different pathways: the adenoma to carcinoma chromosomal instability pathway (50%-70%); the mutator “Lynch syndrome” route (3%-5%); and the serrated pathway (30%-35%). The World Health Organization has classified serrated polyps into three types of lesions: hyperplastic polyps (HP), sessile serrated adenomas/polyps (SSA/P) and traditional serrated adenomas (TSA), the latter two strongly associated with development of CRCs. HPs do not cause cancer and TSAs are rare. SSA/P appear to be the responsible precursor lesion for the development of cancers through the serrated pathway. Both HPs and SSA/Ps appear morphologically similar. SSA/P are difficult to detect. The margins are normally inconspicuous. En bloc resection of these polyps can hence be troublesome. A careful examination of borders, submucosal injection of a dye solution (for larger lesions) and resection of a rim of normal tissue around the lesion may ensure total eradication of these lesions.

Keywords: Colonoscopy; Sessile serrated adenoma/polyp; Serrated lesion; Colorectal polyps; Colorectal cancer; Polypectomy; Image enhancing endoscopy; Narrow band imaging, Endocytoscopy

Core tip: Colorectal cancers (CRC) arise from 3 pathways: adenoma to carcinoma; “Lynch syndrome”; and serrated. There are 3 types of serrated lesions namely: Hyperplastic Polyps, Sessile Serrated Adenomas/Polyps and Traditional Serrated Adenomas, the latter two are associated with CRC. A careful examination of borders, submucosal injection with dye and ensuring that a rim of normal tissue is removed is paramount.

INTRODUCTION

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is a major health concern, especially in western countries. According to the American Cancer Society’s estimates, CRC accounts for almost 50000 deaths in the United States with almost 130000 new cases diagnosed in 2016. It is the third commonest type of cancer. Effective screening programs for identification of malignant and premalignant colorectal lesions are thus of utmost importance. In the last few decades the adenoma to adenocarcinoma pathway has been well recognized. For some time it was believed to be the only pathway apart from the “Lynch syndrome” route that results in the development of CRC. The effort to detect and eradicate adenoma have been the main goal in preventive colorectal programs, leading to improved outcomes. Zauber et al[1] showed that colonoscopic removal of adenomatous polyps led to a 53% reduction in mortality from CRC during the first 10 years after polypectomy.

It is currently believed that CRC arises from 3 different pathways: the adenoma to carcinoma pathway which accounts for about 50%-70% of cancers; through the mutator “Lynch syndrome” route (3%-5%); and more recently the serrated pathway (30%-35%). The latter have become increasingly recognized as a separate route which could lead to the development of CRC[2].

This triplet division is based on the combined clinical-molecular characteristics of the lesions. A deeper understanding of the molecular pathways in CRC have been described by Jass in 2007[3] and updated by Phipps et al[4] in 2015. They described 5 molecular subtypes and associated genetic distortions to describe each one. Subtypes 1, 2 and 3 are related to the serrated pathway. Subtypes 1 and 2 are either microsatellite instable (MSI)-high or microsatellite stable (MSS)/MSI-low cancers which have the CpG island methylator phenotype (CIMP) and BRAF-mutation but are KRAS negative. The third subtype represents an alternative pathway which originates in KRAS mutation with no CIMP, BRAF or MSI association. Subtypes 2 and 3 have a higher association with mortality[4]. Subtype 4 reflects CRC arising from the traditional adenoma-carcinoma sequence, and are MSS/MSI-low, CIMP, BRAF and KRAS negative. Subtype 5 indicates lynch syndrome and is associated with high prevalence of a family history of CRC. They are MSI-high but CIMP, BRAF and KRAS negative.

The serrated pathway is much less well understood. Systematic resection of premalignant serrated lesions could further improve the outcomes of CRC screening programs. One of the main problems with this protocol is the difficulty in identifying these lesions. Unlike adenomas, not all serrated lesions are linked to colorectal cancer. According to the World Health Organization, there are three types of serrated lesions: Hyperplastic polyps (HP), sessile serrated adenomas/polyps (SSA/P) and traditional serrated adenomas (TSA). TSA is usually easy to identify due to its protuberant pine cone-shape. While SSA/P is also associated with cancer, HP is not and their discrimination is troublesome as they look morphologically similar at colonoscopy, even with image enhancing endoscopy (IEE) techniques. Despite the adoption of numerous different classifications, the ability to predict HP from SSA/P has unfortunately been overlooked[5,6]. More recently, a newly proposed approach known as Workgroup Serrated polypS and Polyposis WASP classification has allowed the distinction between HP and SSA/P with reasonable accuracy[7]. It consists of cloud-like surface, indistinctive borders, irregular margins and open pit patterns, features described as being associated with SSA/P in another previous study[8]. The need to adequately identify SSA/P from HP arises from evidence supporting SSA/P as the major malignant source amongst serrated lesions[2,9-12].

IEE

Detecting and characterizing colorectal lesions by IEE has been reported in several articles[13-17] and has been found to have 92.7% sensitivity and 87.3% specificity in differentiating adenomas/adenocarcinomas from “non-neoplastic” lesions[18]. Differentiating serrated lesions, specifically SSA/P from HP is more challenging. The incidence of serrated lesions in the overall population is 5%-8% (contrasting with 30%-40% for adenomas), and they are more difficult to see due to their colour and shape[8,19,20]. Their rarity and discreet morphology could be why there is a longer learning curve compared to that for adenomas[21-24].

The evaluation of dysplasia within the SSA/Ps could also be of value. It has been described by Chino et al[25] 2016 that the evaluation of crypts and submucosal vessels with narrow band imaging (NBI) and magnification might be useful in evaluating dysplasia in SSA/P, which leads to poorer outcomes.

Although there is certainly enthusiasm for IEE techniques, histopathology remains the gold standard for evaluating colorectal lesions. Nonetheless, improving technology that could be used by the endoscopist in real time would definitely be beneficial for serrated lesions as it has been for adenomas[26]. This technology will need to provide immediate feedback and accurately predict the final histopathology (Figure 1).

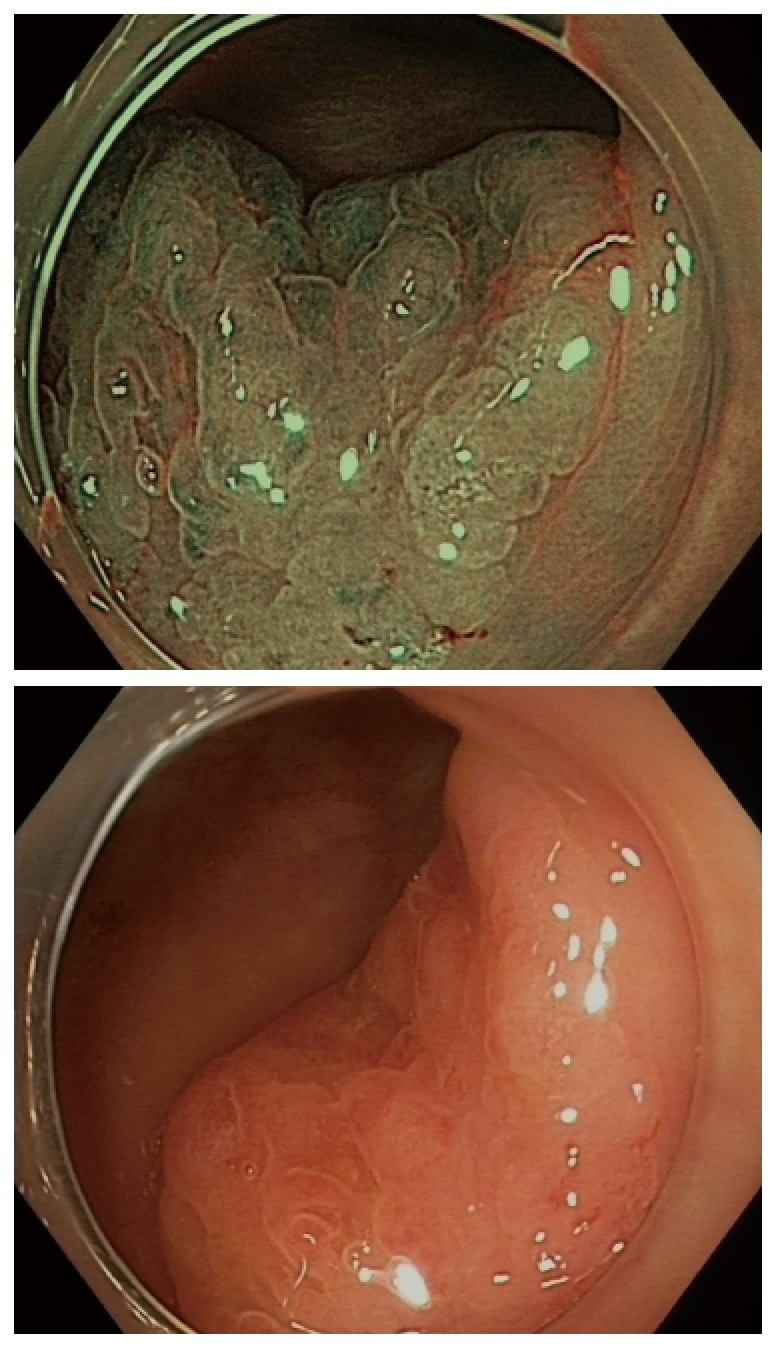

Figure 1.

Inconspicuous margins of a sessile serrated adenomas/polyps with and without narrow-band imaging.

SSA/P AND HP DIFFERENTIATION

A conceptual way to define each serrated lesion is based on differences in the proliferation zones within the serrated crypts in each group[27]. In HP, the expanded proliferation zone is located at the base of the crypts and cells mature towards the surface symmetrically. In SSA/P, the proliferation zone is to the side of the crypts instead of the base, resulting in maturation of epithelial cells laterally, towards the surface and the base, leading to crypt base dilatation (pattern II-open). Within SSA/P, the presence of dysplasia is usually evident and must be accompanied by SSA/P component adjacent to it once its histopathology is similar to adenomas. Unfortunately, this theoretical classification may be misleading. Confounded even by expert pathologists, the poor agreement for the diagnosis of villous features or high grade dysplasia has a 10-fold variability[28-30].

New techniques for real-time in vivo optical diagnosis using IEE have been developed to potentially predict histology and perhaps permit a more practical and economical approach for low-risk polyps; for example the “resect and discard” approach[31-34]. There is evidence from several original articles and meta-analyses that in vivo optical diagnosis using either NBI or Fujinon intelligent chromoendoscopy would be more cost-effective compared to histology without significant changes in follow-up decision, especially for diminutive polyps[34-37]. The American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy statement of 2011 (Preservation and Incorporation of Valuable endoscopic Innovations) describes the standards that new technologies have to achieve in order to be implemented. For the “resect and discard” strategy, it asks for ≥ 90% agreement in the assignment of post-polypectomy surveillance intervals when compared with decisions based on histopathology. With regards to the policy of leaving suspected rectosigmoid hyperplastic polyps measuring ≤ 5 mm in place, a ≥ 90% negative predictive value for adenomatous histology is mandated[31]. Abu Dayyeh et al[38] on behalf of the American Societies for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) Technology Committee in 2015 reported in a meta-analysis that the diagnostic value of IEE for diminutive colorectal polyps achieved a pooled NPV 91% and pooled follow-up agreement of 89%. Despite the pooled analysis for agreement in the assignment of surveillance intervals which did not reach the 90% threshold for NBI; experienced endoscopists were able to exceed this (93%) when the diagnosis was made with high confidence.

PREDICTORS OF MALIGNANCY AMONG SSA/P

The most common group of lesions are the diminutive polyps (≤ 5 mm in size), which represent approximately 60% of all polyps detected at primary screening colonoscopy. Their overall association with advanced pathology is low but not negligible[39,40]. On the contrary, Burgess et al[41] have demonstrated that size matters in terms of SSA/P. For every 10 mm increase in lesion size, the OR is 1.90 for cytological dysplasia. SSA/P with cytological dysplasia (SSA/P-D) is also associated with presence of 0-Is component of the Paris’ Classification (OR = 3.1), Kudo’s pit pattern III, IV or V (OR = 3.98) and increasing age (OR = 1.69 per decade).

Yamada et al[32] recently described the presence of dilated branch vessels as an aspect of SSA/Ps with dysplasia. Apart from their characteristics at chromoendoscopy and magnification[42,43], there are some aspects that we can use to distinguish SSA/Ps with and without malignancy potential.

Endocytoscopy is an emerging modality with diagnostic potential for SSA/P. It allows in vivo visualization of cells and nuclei facilitating precise real-time pathological prediction. Oval gland lumens with small round nuclei has a sensitivity of 83.3% and specificity of 97.8% for the diagnosis of SSA/P. It is also a promising tool for diagnosing SSA/P-D due to its ability to detect morphological changes in the nuclei as described by Mori et al[44] and Kutsukawa et al[45].

OPTIMAL RESECTION OF AN SSA/P

Numerous studies have grim numbers in regards to SSA/P complete resection rates[46-48]. Against these odds, a more recent study from our group[49] studied the resection of 2000 lateral spreading tumors and attributed the high recurrence to the inconspicuous margins of the SSA/P, which was overcome with IEE techniques. Submucosal instillation of a dye based solution (for larger lesions), a careful examination of borders and a rim of normal tissue resected together with the lesion may have affected the high rate of complete removal of the SSA/P. It is evident the contribution that advanced endoscopy apparel and endoscopist’s expertise is essential[50] in order to keep the recurrence of resection as low as 7%, as described by Pellise et al[49] (Figure 2).

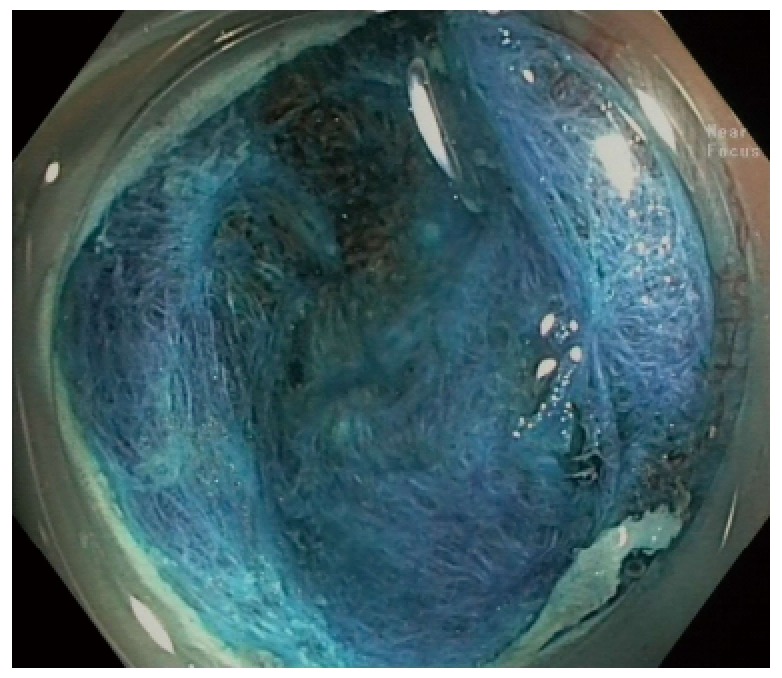

Figure 2.

Resection of a sessile serrated adenomas/polyps with dye of submucosal layer with indigo carmine - no residual lesion.

FOLLOW-UP

The current guidelines from the ASGE and European Societies for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy advocates the standard 5-10 years surveillance period for low risk lesions (SSA/P < 10 mm and without dysplasia), in patients without serrated polyposis syndrome. Patients with larger SSA/Ps or with dysplasia should have their colonoscopy repeated in 3 years-time[51,52]. The serrated polyposis syndrome is defined if any number of serrated polyps occurring proximal to the sigmoid colon in an individual who has a first-degree relative with serrated polyposis; if at least five serrated polyps are found proximal to the sigmoid colon (at least 2 with ≥ 10 mm); and if more than 20 serrated polyps of any size distributed throughout the colon. In these cases, the follow-up should be at 1 year[51]. The major problem is that these guidelines rely upon the assumption that the serrated lesions are detected and resected adequately, which is not always the case.

CONCLUSION

SSA/P is an important pre-malignant lesion that can easily be missed. Efforts must be made in order to alter the nomenclature of “non-neoplastic lesions” to non-adenomatous lesions as the role of serrated lesions in the development of colorectal cancer is now well established. A longer training must be pursued and cutting-edge IEE technologies developed and studied in order to diminish the miss rate for serrated lesions. The implementation of a “serrated polyps detection rate” could be implemented alongside the “adenoma detection rate” as a quality indicator for colonoscopy.

Footnotes

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Australia

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Conflict-of-interest statement: No potential conflicts of interest. No financial support.

Peer-review started: May 8, 2016

First decision: June 20, 2016

Article in press: August 1, 2016

P- Reviewer: Albuquerque A, Vynios D, Naito Y S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wang CH

References

- 1.Zauber AG, Winawer SJ, O’Brien MJ, Lansdorp-Vogelaar I, van Ballegooijen M, Hankey BF, Shi W, Bond JH, Schapiro M, Panish JF, et al. Colonoscopic polypectomy and long-term prevention of colorectal-cancer deaths. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:687–696. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1100370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Erichsen R, Baron JA, Hamilton-Dutoit SJ, Snover DC, Torlakovic EE, Pedersen L, Frøslev T, Vyberg M, Hamilton SR, Sørensen HT. Increased Risk of Colorectal Cancer Development Among Patients With Serrated Polyps. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:895–902.e5. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.11.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jass JR. Classification of colorectal cancer based on correlation of clinical, morphological and molecular features. Histopathology. 2007;50:113–130. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2006.02549.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Phipps AI, Limburg PJ, Baron JA, Burnett-Hartman AN, Weisenberger DJ, Laird PW, Sinicrope FA, Rosty C, Buchanan DD, Potter JD, et al. Association between molecular subtypes of colorectal cancer and patient survival. Gastroenterology. 2015;148:77–87.e2. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.09.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hewett DG, Kaltenbach T, Sano Y, Tanaka S, Saunders BP, Ponchon T, Soetikno R, Rex DK. Validation of a simple classification system for endoscopic diagnosis of small colorectal polyps using narrow-band imaging. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:599–607.e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kumar S, Fioritto A, Mitani A, Desai M, Gunaratnam N, Ladabaum U. Optical biopsy of sessile serrated adenomas: do these lesions resemble hyperplastic polyps under narrow-band imaging? Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;78:902–909. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2013.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.IJspeert JE, Bastiaansen BA, van Leerdam ME, Meijer GA, van Eeden S, Sanduleanu S, Schoon EJ, Bisseling TM, Spaander MC, van Lelyveld N, et al. Development and validation of the WASP classification system for optical diagnosis of adenomas, hyperplastic polyps and sessile serrated adenomas/polyps. Gut. 2016;65:963–970. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2014-308411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hazewinkel Y, López-Cerón M, East JE, Rastogi A, Pellisé M, Nakajima T, van Eeden S, Tytgat KM, Fockens P, Dekker E. Endoscopic features of sessile serrated adenomas: validation by international experts using high-resolution white-light endoscopy and narrow-band imaging. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;77:916–924. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2012.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang CS, O’brien MJ, Yang S, Farraye FA. Hyperplastic polyps, serrated adenomas, and the serrated polyp neoplasia pathway. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:2242–2255. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.40131.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kawasaki K, Kurahara K, Yanai S, Oshiro Y, Yao T, Kobayashi H, Nakamura S, Fuchigami T, Sugai T, Matsumoto T. Colonoscopic features and malignant potential of sessile serrated adenomas: comparison with other serrated lesions and conventional adenomas. Colorectal Dis. 2016;18:795–802. doi: 10.1111/codi.13276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chino A, Yamamoto N, Kato Y, Morishige K, Ishikawa H, Kishihara T, Fujisaki J, Ishikawa Y, Tamegai Y, Igarashi M. The frequency of early colorectal cancer derived from sessile serrated adenoma/polyps among 1858 serrated polyps from a single institution. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2016;31:343–349. doi: 10.1007/s00384-015-2416-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Teriaky A, Driman DK, Chande N. Outcomes of a 5-year follow-up of patients with sessile serrated adenomas. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2012;47:178–183. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2011.645499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kanao H, Tanaka S, Oka S, Hirata M, Yoshida S, Chayama K. Narrow-band imaging magnification predicts the histology and invasion depth of colorectal tumors. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:631–636. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tanaka S, Sano Y. Aim to unify the narrow band imaging (NBI) magnifying classification for colorectal tumors: current status in Japan from a summary of the consensus symposium in the 79th Annual Meeting of the Japan Gastroenterological Endoscopy Society. Dig Endosc. 2011;23 Suppl 1:131–139. doi: 10.1111/j.1443-1661.2011.01106.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Inoue H, Yokoyama A, Kudo SE. [Ultrahigh magnifying endoscopy: development of CM double staining for endocytoscopy and its safety] Nihon Rinsho. 2010;68:1247–1252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Singh R, Chen Yi Mei SL, Tam W, Raju D, Ruszkiewicz A. Real-time histology with the endocytoscope. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:5016–5019. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i40.5016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kudo S, Hirota S, Nakajima T, Hosobe S, Kusaka H, Kobayashi T, Himori M, Yagyuu A. Colorectal tumours and pit pattern. J Clin Pathol. 1994;47:880–885. doi: 10.1136/jcp.47.10.880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li M, Ali SM, Umm-a-OmarahGilani S, Liu J, Li YQ, Zuo XL. Kudo’s pit pattern classification for colorectal neoplasms: a meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:12649–12656. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i35.12649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abdeljawad K, Vemulapalli KC, Kahi CJ, Cummings OW, Snover DC, Rex DK. Sessile serrated polyp prevalence determined by a colonoscopist with a high lesion detection rate and an experienced pathologist. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81:517–524. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2014.04.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sano W, Sano Y, Iwatate M, Hasuike N, Hattori S, Kosaka H, Ikumoto T, Kotaka M, Fujimori T. Prospective evaluation of the proportion of sessile serrated adenoma/polyps in endoscopically diagnosed colorectal polyps with hyperplastic features. Endosc Int Open. 2015;3:E354–E358. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1391948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ignjatovic A, Thomas-Gibson S, East JE, Haycock A, Bassett P, Bhandari P, Man R, Suzuki N, Saunders BP. Development and validation of a training module on the use of narrow-band imaging in differentiation of small adenomas from hyperplastic colorectal polyps. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;73:128–133. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2010.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Raghavendra M, Hewett DG, Rex DK. Differentiating adenomas from hyperplastic colorectal polyps: narrow-band imaging can be learned in 20 minutes. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;72:572–576. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2010.03.1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rastogi A, Rao DS, Gupta N, Grisolano SW, Buckles DC, Sidorenko E, Bonino J, Matsuda T, Dekker E, Kaltenbach T, et al. Impact of a computer-based teaching module on characterization of diminutive colon polyps by using narrow-band imaging by non-experts in academic and community practice: a video-based study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;79:390–398. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2013.07.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Higashi R, Uraoka T, Kato J, Kuwaki K, Ishikawa S, Saito Y, Matsuda T, Ikematsu H, Sano Y, Suzuki S, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of narrow-band imaging and pit pattern analysis significantly improved for less-experienced endoscopists after an expanded training program. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;72:127–135. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2010.01.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chino A, Osumi H, Kishihara T, Morishige K, Ishikawa H, Tamegai Y, Igarashi M. Advantages of magnifying narrow-band imaging for diagnosing colorectal cancer coexisting with sessile serrated adenoma/polyp. Dig Endosc. 2016;28 Suppl 1:53–59. doi: 10.1111/den.12631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dacosta RS, Wilson BC, Marcon NE. New optical technologies for earlier endoscopic diagnosis of premalignant gastrointestinal lesions. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;17 Suppl:S85–S104. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.17.s1.8.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Torlakovic EE, Gomez JD, Driman DK, Parfitt JR, Wang C, Benerjee T, Snover DC. Sessile serrated adenoma (SSA) vs. traditional serrated adenoma (TSA) Am J Surg Pathol. 2008;32:21–29. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e318157f002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Terry MB, Neugut AI, Bostick RM, Potter JD, Haile RW, Fenoglio-Preiser CM. Reliability in the classification of advanced colorectal adenomas. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2002;11:660–663. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Costantini M, Sciallero S, Giannini A, Gatteschi B, Rinaldi P, Lanzanova G, Bonelli L, Casetti T, Bertinelli E, Giuliani O, et al. Interobserver agreement in the histologic diagnosis of colorectal polyps. the experience of the multicenter adenoma colorectal study (SMAC) J Clin Epidemiol. 2003;56:209–214. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(02)00587-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lasisi F, Mouchli A, Riddell R, Goldblum JR, Cummings OW, Ulbright TM, Rex DK. Agreement in interpreting villous elements and dysplasia in adenomas less than one centimetre in size. Dig Liver Dis. 2013;45:1049–1055. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2013.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rex DK, Kahi C, O’Brien M, Levin TR, Pohl H, Rastogi A, Burgart L, Imperiale T, Ladabaum U, Cohen J, et al. The American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy PIVI (Preservation and Incorporation of Valuable Endoscopic Innovations) on real-time endoscopic assessment of the histology of diminutive colorectal polyps. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;73:419–422. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yamada M, Sakamoto T, Otake Y, Nakajima T, Kuchiba A, Taniguchi H, Sekine S, Kushima R, Ramberan H, Parra-Blanco A, et al. Investigating endoscopic features of sessile serrated adenomas/polyps by using narrow-band imaging with optical magnification. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;82:108–117. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2014.12.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Iwatate M, Sano Y, Hattori S, Sano W, Hasuike N, Ikumoto T, Kotaka M, Murakami Y, Hewett DG, Soetikno R, et al. The addition of high magnifying endoscopy improves rates of high confidence optical diagnosis of colorectal polyps. Endosc Int Open. 2015;3:E140–E145. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1391362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ignjatovic A, East JE, Suzuki N, Vance M, Guenther T, Saunders BP. Optical diagnosis of small colorectal polyps at routine colonoscopy (Detect InSpect ChAracterise Resect and Discard; DISCARD trial): a prospective cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:1171–1178. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70329-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gupta N, Bansal A, Rao D, Early DS, Jonnalagadda S, Edmundowicz SA, Sharma P, Rastogi A. Accuracy of in vivo optical diagnosis of colon polyp histology by narrow-band imaging in predicting colonoscopy surveillance intervals. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;75:494–502. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Longcroft-Wheaton GR, Higgins B, Bhandari P. Flexible spectral imaging color enhancement and indigo carmine in neoplasia diagnosis during colonoscopy: a large prospective UK series. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;23:903–911. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e328349e276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hassan C, Pickhardt PJ, Rex DK. A resect and discard strategy would improve cost-effectiveness of colorectal cancer screening. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:865–869, 869.e1-3. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2010.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Abu Dayyeh BK, Thosani N, Konda V, Wallace MB, Rex DK, Chauhan SS, Hwang JH, Komanduri S, Manfredi M, Maple JT, et al. ASGE Technology Committee systematic review and meta-analysis assessing the ASGE PIVI thresholds for adopting real-time endoscopic assessment of the histology of diminutive colorectal polyps. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81:502.e1–502.e16. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2014.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Regula J, Rupinski M, Kraszewska E, Polkowski M, Pachlewski J, Orlowska J, Nowacki MP, Butruk E. Colonoscopy in colorectal-cancer screening for detection of advanced neoplasia. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1863–1872. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa054967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gschwantler M, Kriwanek S, Langner E, Göritzer B, Schrutka-Kölbl C, Brownstone E, Feichtinger H, Weiss W. High-grade dysplasia and invasive carcinoma in colorectal adenomas: a multivariate analysis of the impact of adenoma and patient characteristics. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;14:183–188. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200202000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Burgess NG, Pellise M, Nanda KS, Hourigan LF, Zanati SA, Brown GJ, Singh R, Williams SJ, Raftopoulos SC, Ormonde D, et al. Clinical and endoscopic predictors of cytological dysplasia or cancer in a prospective multicentre study of large sessile serrated adenomas/polyps. Gut. 2016;65:437–446. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2014-308603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ignjatovic A, East JE, Guenther T, Hoare J, Morris J, Ragunath K, Shonde A, Simmons J, Suzuki N, Thomas-Gibson S, et al. What is the most reliable imaging modality for small colonic polyp characterization? Study of white-light, autofluorescence, and narrow-band imaging. Endoscopy. 2011;43:94–99. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1256074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rex DK, Clodfelter R, Rahmani F, Fatima H, James-Stevenson TN, Tang JC, Kim HN, McHenry L, Kahi CJ, Rogers NA, et al. Narrow-band imaging versus white light for the detection of proximal colon serrated lesions: a randomized, controlled trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;83:166–171. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2015.03.1915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mori Y, Kudo SE, Ogawa Y, Wakamura K, Kudo T, Misawa M, Hayashi T, Katagiri A, Miyachi H, Inoue H, et al. Diagnosis of sessile serrated adenomas/polyps using endocytoscopy (with videos) Dig Endosc. 2016;28 Suppl 1:43–48. doi: 10.1111/den.12601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kutsukawa M, Kudo SE, Ikehara N, Ogawa Y, Wakamura K, Mori Y, Ichimasa K, Misawa M, Kudo T, Wada Y, et al. Efficiency of endocytoscopy in differentiating types of serrated polyps. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;79:648–656. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2013.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Khashab M, Eid E, Rusche M, Rex DK. Incidence and predictors of “late” recurrences after endoscopic piecemeal resection of large sessile adenomas. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;70:344–349. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.10.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kahi CJ, Hewett DG, Norton DL, Eckert GJ, Rex DK. Prevalence and variable detection of proximal colon serrated polyps during screening colonoscopy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:42–46. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2010.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pohl H, Srivastava A, Bensen SP, Anderson P, Rothstein RI, Gordon SR, Levy LC, Toor A, Mackenzie TA, Rosch T, et al. Incomplete polyp resection during colonoscopy-results of the complete adenoma resection (CARE) study. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:74–80.e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.09.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pellise M, Burgess NG, Tutticci N, Hourigan LF, Zanati SA, Brown GJ, Singh R, Williams SJ, Raftopoulos SC, Ormonde D, et al. Endoscopic mucosal resection for large serrated lesions in comparison with adenomas: a prospective multicentre study of 2000 lesions. Gut. 2016 doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-310249. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Valori R, Rey JF, Atkin WS, Bretthauer M, Senore C, Hoff G, Kuipers EJ, Altenhofen L, Lambert R, Minoli G. European guidelines for quality assurance in colorectal cancer screening and diagnosis. First Edition--Quality assurance in endoscopy in colorectal cancer screening and diagnosis. Endoscopy. 2012;44 Suppl 3:SE88–SE105. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1309795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lieberman DA, Rex DK, Winawer SJ, Giardiello FM, Johnson DA, Levin TR. Guidelines for colonoscopy surveillance after screening and polypectomy: a consensus update by the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:844–857. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hassan C, Quintero E, Dumonceau JM, Regula J, Brandão C, Chaussade S, Dekker E, Dinis-Ribeiro M, Ferlitsch M, Gimeno-García A, et al. Post-polypectomy colonoscopy surveillance: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline. Endoscopy. 2013;45:842–851. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1344548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]