Abstract

Objective

To investigate the role of “mifepristone” for induction of labor (IOL) in pregnant women with prior cesarean section (CS).

Methods

In this retrospective study, all pregnant women with prior CS who received oral mifepristone (400 mg) for IOL (as per clear obstetric indications) [group 1] were compared with pregnant women with prior CS who had spontaneous onset of labor (SOL) [group 2], with respect to incidence of vaginal delivery, CS, duration of labor, and various maternal and fetal outcomes.

Results

During the study period, 72 women received mifepristone (group 1) for IOL and 346 had SOL (group 2). In group 1 after mifepristone administration, 40 (55.6 %) women had labor onset, and 24 (33.3 %) women had cervical ripening (Bishop Score ≥ 8) within 48 h. There were no statistically significant differences with respect to duration of labor (p value: 0.681), mode of delivery (i.e., normal delivery or CS—p value: 0.076 or 0.120, respectively), or maternal (blood loss or scar dehiscence/rupture uterus), or fetal outcomes (NICU admission) compared to women with previous CS with SOL (group 2). However, the need of oxytocin (p value 0.020) and dose of oxytocin requirement (p value 0.008) were more statistically significant in group 1.

Conclusion

Mifepristone may be considered as an agent for IOL in women with prior CS.

Keywords: Pregnancy, Mifepristone, Induction of labor, Prior cesarean delivery

Introduction

Cesarean section (CS) rates are increasing worldwide [1]. Consequently, the number of pregnant women with previous CS is also increasing dramatically [1, 2]. This is not only leading to a massive escalation in the cost of the obstetric services but also increasing the incidence of previously rare but catastrophic complications of pregnancy (e.g., cesarean scar pregnancy, morbid adherent placenta, uterine rupture, and feto-maternal morbidity) [2]. In addition, the increase in the number of pregnant women with previous CS is posing severe constraint on the already scarce resources in the developing countries [3].

As women with previous CS are increasing, more and more women (with previous CS) are presenting to obstetricians for induction of labor (IOL) due to various obstetrical indications. Even though trial of labor after CS (TOLAC) is a reasonable option in majority of these women [4], still a significant proportion of these women undergo elective repeat CS (ERCS) due to limited options available for IOL in these women, thereby further compounding the dangerous trend of rising rates of CS [1–3].

In addition, IOL is not only associated with decreased rates of successful vaginal delivery (compared to spontaneous labor) but also with the increased rates of catastrophic complications, e.g., scar dehiscence/rupture uterus, and subsequent fetal death and severe maternal morbidity and mortality [4]. Cochrane systematic review on IOL in women with prior CS states that there is lack of information to decide optimal method for IOL in women with previous CS [5]. Another systematic review on IOL in women with prior CS opined that meta-analysis is not possible due to paucity of evidence and advises caution for IOL in women with scarred uterus [6]. There is an ongoing search for an ideal agent for IOL in women with previous CS so as to increase the chances of vaginal delivery and minimize (if not completely eliminate) the chances of scar dehiscence/rupture uterus. This will go a long way in reducing the rates of ERCS, thereby ultimately reducing the overall rising rates of CS.

One such agent under investigation is “mifepristone.” Cochrane systematic review on mifepristone for IOL in pregnant women (without CS) states that there is limited evidence in support of mifepristone for IOL [7]. However, it was further stated that it was better than placebo in reducing the rates of CS performed for failure of IOL. Also they had presumed theoretically that mifepristone may be advantageous in women with previous CS as it is not an uterotonic and hence may not be associated with over stimulation or rupture uterus, and further research could be initiated in this direction [7].

Hence, we conducted this study for evaluating the role of mifepristone in women with prior CS for IOL with a goal of reducing the rates of ERCS and ultimately, reducing overall CS rates.

Materials and methods

This study is a retrospective analysis of all women with previous one CS who received mifepristone for labor induction, after approval from institutional review board was taken (registration No. ECR/490/Inst/HP/2013) vide letter No. HFW-H-DRPGMC/Ethics/2014.

All the pregnant women (with prior CS) who had received oral mifepristone for IOL from July 1, 2013 to September 30, 2014 were compared with pregnant women with prior CS who had spontaneous onset of labor (SOL) in this pregnancy retrospectively, in the Department of Obstetrics & Gynaecology of Dr. Rajendra Prasad Government Medical College and Hospital, Tanda, Kangra, India. It is a tertiary care teaching hospital catering to the needs of adjoining rural and tribal population, with an average of 8000 deliveries and 2000 CS annually.

All the pregnant women with previous one CS were encouraged and evaluated for TOLAC. Inclusion criteria were singleton pregnancy, previous one low-segment CS (no other uterine scar or previous rupture), and cephalic presentation. Exclusion criteria were interconceptional period less than 18 months, estimated fetal birth weight > 4 kg, premature rupture of membranes/chorio-amniotis, any evidence of fetal distress at admission, any contraindication for vaginal delivery (cephalo-pelvic disproportion ruled out), and type of uterine incision in prior CS not known.

Pregnant women with prior CS after satisfying the inclusion and exclusion criteria were counseled in detail for IOL, advantages of successful TOLAC, risks associated with failed TOLAC, various agents for IOL, advantages, and concerns regarding the use of mifepristone for IOL. After taking written informed consent, these women received 400 milligrams (mg) of mifepristone orally [two tablets of mifepristone 200 mg each] for IOL for clear obstetric indications (group 1). Subsequently, they were compared with pregnant women with prior one CS willing for TOLAC and presenting with spontaneous onset of labor (SOL) (group 2), retrospectively.

Labor onset (defined as regular uterine contractions with progressive cervical dilatation and effacement) after mifepristone, was recorded in women in group 1 up to 48 h. Bishop score was assessed after 24 and 48 h of mifepristone administration. If at any time bishop score was ≥8, amniotomy followed by oxytocin infusion was done. If, even after 48 h, neither there was labor onset nor bishop score ≥8, women were again counseled, and as per consent of women, ERCS or IOL with oxytocin, was done.

All the women in labor (group 1 and group 2) were managed as per labor-room protocols. The decisions regarding need for augmentation of labor (with oxytocin), emergency CS, or operative vaginal delivery were taken by the managing team of obstetricians. Women who required oxytocin (Bishop Score ≥ 8 or for augmentation of labor), received low-dose oxytocin infusion (starting at 3 mU/min and every 20 min increments of 3 mU/min, till adequate uterine contractions were established [3–5 uterine contractions every 10 min with each contraction lasting 30–45 s]). The intraoperative findings (indication of CS, scar dehiscence/scar rupture, blood loss, need for blood transfusion, or peri-partum hysterectomy), and subsequent hospital stay were recorded in all the women who underwent CS for whatsoever indication. Neonatal assessment was done by the attending neonatologist, and admission to NICU was recorded in all the neonates.

Statistical analysis was performed by SPSS 17 software using parametric and nonparametric tests when appropriate. The normality of the distribution was assessed by the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Continuous data were analyzed with the t test, and categorical variables were analyzed with the Fisher’s exact test. p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Kaplan–Meier survival analysis was done to estimate the proportion of women who delivered vaginally in either group at any point of time. All women who had CS in this pregnancy were excluded from the Kaplan–Meier Survival analysis (as duration of labor could not be calculated in these women due to CS at different cervical dilatations).

Results

As shown in Fig. 1, during the study period, there were a total of 8342 deliveries. A total of 2486 pregnant women had previous CS (29.8 %). Out of these, 1626 had ERCS (896 had either extension of uterine incision or had no record of previous uterine incision; 488 women had previous two or more CS; and 242 had repeat CS for obstetrical indication). Of the remaining 860 eligible women, 312 refused for TOLAC (and had ERCS), 72 women consented for IOL with mifepristone (group 1) for clear obstetrical indications, and 346 had SOL (group 2). and 130 women opted for other methods for IOL (intracervical catheter, synthetic cervical dilators, or oxytocin infusion).

Fig. 1.

Total pregnant women during the study period

Women in groups 1 and 2 were compared with respect to baseline characteristics, as shown in Table 1. Age, body mass index, abortions (one, two, or three), indication of previous CS, interdelivery interval, Bishop score at first assessment, sex, and birth weight of the neonate, were not statistically significantly different in these groups. However, period of gestation was statistically significantly different in two groups as shown in Table 1 (280.1 ± 4.2 days vs. 273.6 ± 6.5 days,, respectively, in groups 1 and 2, p value 0.000).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of women

| Group 1 (n = 72) | Group 2 (n = 346) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| AGE (in years)a | 27 (3) | 27 (4) | 0.285 |

| BMI (in kg/m2)a | 21.1 (1.7) | 21.1 (1.7) | 0.930 |

| Abortion | |||

| One (n) | 15 | 71 | 0.870 |

| Two (n) | 3 | 5 | 0.289 |

| Three(n) | 0 | 4 | 0.979 |

| Previous vaginal delivery (n) | 15 | 72 | 0.996 |

| Previous successful TOLAC (n) | 3 | 5 | 0.289 |

| Indication of previous CS (n) | |||

| Acute fetal distress | 38 | 161 | 0.403 |

| Mal-presentation | 15 | 88 | 0.504 |

| Failure of induction | 10 | 32 | 0.329 |

| Non progress of labor | 9 | 65 | 0.271 |

| POG (in days)b | 280.1 ± 4.2 | 273.6 ± 6.5 | 0.000 |

| Inter delivery interval (n) | |||

| 18–24 months | 6 | 39 | 0.601 |

| 24–36 months | 19 | 108 | 0.503 |

| >36 months | 47 | 199 | 0.277 |

| Bishop scorea | 7 (3) | 7 (2) | 0.130 |

| Sex of neonate (n) | |||

| Boy | 38 | 193 | 0.737 |

| Girl | 34 | 153 | 0.739 |

| Birth weight (in kgs.)a | 3.0 (0.25) | 2.9 (0.50) | 0.148 |

aNonnormal distribution [median {interquartile range}]

bNormal distribution [mean ± standard deviation]

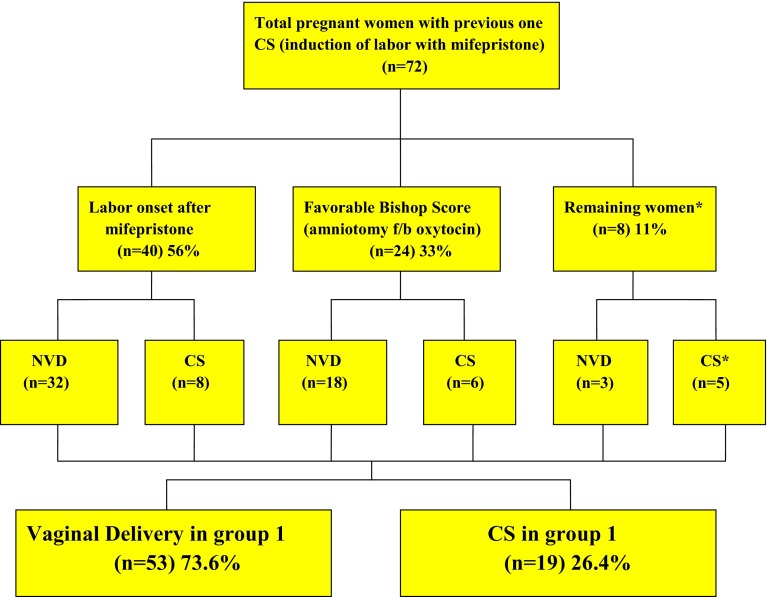

In group 1 after the initial dose of mifepristone (orally given two tablets each of 200 mg mifepristone; total 400 mg) within 48 h, 40 women had labor onset, and 24 women had Bishop score ≥ 8 (as per study protocol amniotomy followed by oxytocin infusion for IOL was done). Even after 48 h, eight women neither had labor onset nor favorable bishop score (≥8); of these, all but one woman (in whom ERCS was done) opted for oxytocin infusion for IOL, as shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Pregnancy outcome in group 1 (mifepristone group). Asterisks one woman who opted out of study protocol and requested for CS after 48 h of mifepristone

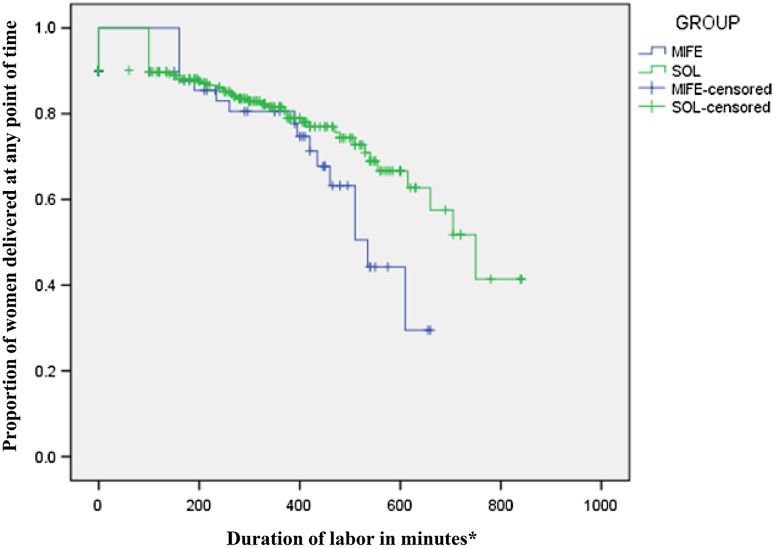

There was no statistically significant difference with respect to duration of labor in either group (first stage {median [interquartile range]}; 350[353] min in group 1 vs. 292.5 [295] min in group 2, p value 0.681; and second stage {median [interquartile range]}; 21.5 [28] min in group 1 vs. 23 [13] min in group 2, p value 0.319). Figure 3, shows the Kaplan–Meier Survival Analysis depicting proportion of women delivered in two groups at any point of time (after exclusion of women undergoing emergency CS).

Fig. 3.

Kaplan–Meier Survival Analysis showing proportion of women delivered in two groups at any point of time. Asterisks women with CS excluded from analysis of duration of labor

Mode of delivery (i.e., normal vaginal delivery (NVD), operative vaginal delivery (OVD), and CS) were not statistically significantly different in the two study groups [group 1 (number of women with NVD, OVD, and CS); 40, 13, and 19 vs. group 2 (number of women with NVD, OVD, and CS); 233, 52, and 61; p value 0.076, 0.641 and 0.120, respectively], as shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Maternal and fetal outcomes

| Group 1 (n = 72) | Group 2 (n = 346) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mode of delivery (n) | |||

| Normal vaginal delivery | 40 | 233 | 0.076 |

| Operative vaginal delivery | 13 | 52 | 0.641 |

| Cesarean section | 19 | 61 | 0.120 |

| Indication of cesarean section (n) | |||

| Acute fetal distress | 11 | 39 | 0.095 |

| Non progress of labor | 8 | 22 | 0.069 |

| Duration of first stage of labor (in minutes)a | 350 (353) | 292.5 (295) | 0.681 |

| Duration of second stage of labor (in minutes)a | 21.5 (28) | 23 (13) | 0.319 |

| Oxytocin requirement (n) | 24 | 35 | 0.020 |

| Dose of oxytocin required (mIU/min) | 760 (260) | 540 (130) | 0.008 |

| Blood loss (in ml)a | 200 (455) | 180 (130) | 0.202 |

| Blood loss (n) | |||

| 500–1000 ml | 17 | 58 | 0.227 |

| >1000 ml | 1 | 6 | 0.835 |

| Hospital stay (in days)a | 4 (4) | 2 (3) | 0.078 |

| Apgar score | |||

| 1 min | 7 (6–8) | 7 (6–8) | 0.891 |

| 5 min | 7 (6–8) | 7 (6–8) | 0.684 |

| NICU admission (n) | 2 | 8 | 0.814 |

| Maternal morbidity (n) | |||

| Scar dehiscence | 0 | 2 | 0.801 |

| Rupture uterus | 0 | 1 | 0.648 |

| Peri-partum hysterectomy | 0 | 1 | 0.648 |

| Blood transfusion required | 1 | 6 | 0.835 |

aNonnormal distribution [median {interquartile range]

No statically significant differences were observed in maternal or fetal outcomes in group 1 versus group 2, in terms of average blood loss ({median [interquartile range]}; 200 [455] ml vs. 180 [130] ml, p value 0.202), maternal morbidity {scar dehiscence [number of women]; nil out of 72 vs. two out of 346, p value 0.801}, (scar rupture [number of women]; nil out of 72 vs. one out of 346, p value 0.648), {peri-partum hysterectomy [number of women]; nil out of 72 vs. one out of 346, p value 0.648} and (need for blood transfusion [number of women]; {one out of 72 vs. six out of 346, p value 0.835}); and admission to NICU (number of neonates; two out of 72 vs. eight out of 346, p value 0.814). There was no case of maternal or fetal death.

However, statistically significantly more women in group 1 required oxytocin for induction/augmentation of labor compared to group 2 (24 women out of 72 vs. 35 women out of 346, respectively, p value 0.020). In addition, the dose of oxytocin requirement was also significantly more in group 1 compared to group 2 ({mean ± SD}; 760 ± 260 mIU/min vs. 540 ± 130 mIU/ml, respectively, p value 0.008).

Discussion

The rates of IOL in women with previous CS are decreasing drastically worldwide, and the trend is shifting toward ERCS especially whenever any obstetrical indication necessitates termination of pregnancy [1, 2].

In our study, we observed that mifepristone is associated with favorable outcome in 89 % of women (labor onset in 56 % and cervical ripening 33 %) within 48 h of administration of oral mifepristone. These observations are in accordance with the existing literature where a variable success rate of labor onset at 66–93 % has been observed in pregnant women [8–15]. Also, the effect of cervical ripening after use of mifepristone has been variable ranging from no statistically difference to statistically significant improvement (60–80 % of all cases) [16–20]. However, all these studies except one [11] were conducted in women without previous CS.

There was no observed fetal or maternal side effect of mifepristone. The incidence of intrapartum fetal distress and CS for this indication was not statistically different in two groups. These observations are in accordance with the recent Cochrane meta-analysis which stated that abnormal fetal heart rate patterns are more common after mifepristone compared to placebo but there are no statistically significant differences in terms of Apgar score less than seven at five minutes of birth or increased incidence of CS for fetal distress [7].

However, the need of oxytocin and its dose requirement was statistically significantly more in group 1. This is predominantly because we are comparing pregnant women requiring IOL with women in SOL. This differential requirement of oxytocin (both more in number of women as well as higher dose of oxytocin in those who require it at all) was not found to be associated either with the increased rate of CS or scar dehiscence/rupture uterus.

One of the major apprehensions of using any agent for IOL in women with previous CS is “scar dehiscence/rupture uterus.” A hypothesis was generated by Cochrane systematic review regarding use of mifepristone in women with previous CS for IOL that, as mifepristone is not an uterotonic, chances of scar dehiscence or rupture uterus might not be increased in these women. Our observations are in accordance with their hypothesis, as the indications for emergency CS in both the groups were not statistically significantly different (Table 2). One important point to highlight here is that IOL “per se” is done in women who did not have SOL and hence chances of unsuccessful TOLAC and incidence of CS should be expected to be much higher (than SOL), with whatsoever method is used for IOL in these women [4].

Mifepristone stimulates labor as naturally as possible, which can be very beneficial especially in women with prior CS. Mifepristone leads to cervical ripening [21, 22] (by stimulating the release of nitric oxide); promotes uterine contractions [23] (by increasing myometrial cell excitability, establishing gap junctions between cells and influx of calcium); and increases the release of prostaglandins by decidual cells [24, 25], without acting as a direct uterotonic. As clearly shown in Fig. 3, Kaplan–Meier analysis shows that after women have labor onset (IOL with mifepristone), the labor closely mimics as that in case of SOL, which could be one of the major reason for preferring mifepristone as an agent for IOL in women with prior CS.

One of the major limitations of our study is that it is a retrospective case–control study. However, in our opinion, this study can provide a platform to plan further randomized controlled trials on this subject. Nonetheless, a well-designed randomized controlled trial is required before mifepristone can be established as an agent for IOL in women with previous CS.

Conclusion

Pregnant women with previous CS requiring IOL for clear obstetrical indications pose a significant challenge to the managing obstetrician due to paucity of available options as well as limited evidence in favor of any method for IOL. Mifepristone may be considered as an alternative agent for the same; however, definite evidence on this issue can only be generated from a randomized controlled trial.

Dr. Chanderdeep Sharma

has been working as Assistant Professor in the Department of OBG, Dr. Rajendra Prasad Government Medical College, Kangra (H.P.), India, since 2014 [after completion of senior residency (OBG)]. He completed his MD from the Post Graduate Institute of Medical Education and Research Chandigarh in 2011 [silver medal (first order)]. He is also a Diplomat of National Board (DNB). He has completed MRCOG (Part-1). He has received ‘‘Harold A. Kaminetzsky Prize’’ for the best non-US research paper from the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology (ACOG) in the year 2013. He has authored 23 published papers in international indexed journals in a short span of 3 years of research. He has also received the National Talent Search Examination (NTSE) award. His special interest is focused on high-risk obstetrics.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

There is no conflict of interest with any individual or organization.

Ethical Statement

Compliance with ethical requirements and Conflict of interest Ethical clearance has been taken from ethical committee of Dr. RPGMC Kangra at Tanda (HFW-H-DRPGMC/Ethics/2014) keeping in view the ICMR guidelines (1994) and Helinski declaration (modified 2000). Written informed consent was taken from all the women. Identity of every women is kept as secret. All the women were adequately informed of the aims, methods, and any discomfort it may entail to her and the remedies thereof. Every precaution was taken to respect the privacy of the patient, the confidentiality of the patient’s information, and to minimize the impact of the study on her physical and mental integrity and her personality. The patient was given the right to abstain from the study or to withdraw consent to participate at any time of study without reappraisal.

Footnotes

Dr. Chanderdeep Sharma is an Assistant Professor, Dr. Anjali Soni is an Associate Professor, Dr. Pawan K. Soni is an Assistant Professor (Radio-diagnosis), Dr. Suresh Verma is a Professor and the Head, Dr. Ashok Verma is an Associate Professor, Dr. Amit Gupta is an Associate Professor at the Department of OBG, Dr. Rajendra Prasad Government Medical College (Dr. RPGMC) Kangra at Tanda (HP), Kangra, HP, India.

References

- 1.Arulkumaran S. Caesarean section rates are increasing worldwide. Preface. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2013;27(2):151–152. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2013.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Timor-Tritsch IE, Monteagudo A, Santos R, et al. The diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up of cesarean scar pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;207:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2012.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Niino Y. The increasing cesarean rate globally and what we can do about it. Biosci Trends. 2011;5(4):139–150. doi: 10.5582/bst.2011.v5.4.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.ACOG Practice bulletin no. 115 Vaginal birth after previous cesarean delivery. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116(4):450–463. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181eeb251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jozwiak M, Dodd JM. Methods of term labour induction for women with a previous caesarean section. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009792.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dodd J, Crowther C. Induction of labour for women with a previous Caesarean birth: a systematic review of the literature. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2004;44(5):392–395. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-828X.2004.00258.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hapangama D, Neilson JP. Mifepristone for induction of labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002865.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McGill J, Shetty A. Mifepristone and misoprostol in the induction of labor at term. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2007;96(2):80–84. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2006.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stenlund PM, Ekman G, Aedo AR, et al. Induction of labor with mifepristone–a randomized, double-blind study versus placebo. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1999;78(9):793–798. doi: 10.1080/j.1600-0412.1999.780910.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li L, Gao W, Chen S. Labour induction in women at term with mifepristone and misoprostol. Zhonghua Fu Chan Ke Za Zhi. 1996;31(11):681–684. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lelaidier C, Baton C, Benifla JL, et al. Mifepristone for labour induction after previous caesarean section. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1994;101(6):501–503. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1994.tb13150.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang N, Hu Y. Labor induction in women at term with mifepristone and it’s safety. Zhonghua Fu Chan Ke Za Zhi. 1999;34(12):751–753. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Su H, Li E, Weng L. Mifepristone for induction of labor. Zhonghua Fu Chan Ke Za Zhi. 1996;31(11):676–680. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Edwards MS. Mifepristone: cervical ripening and induction of labor. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1996;39(2):469–473. doi: 10.1097/00003081-199606000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lelaidier C, Benifla JL, Fernandez H, et al. [The value of RU-486 (mifepristone) in medical indications of the induction of labor at term. Results of a double-blind randomized prospective study (RU-486 versus placebo)] J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod. 1993;22(1):91–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Berkane N, Verstraete L, Uzan S, et al. Use of mifepristone to ripen the cervix and induce labor in term pregnancies. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192(1):114–120. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.05.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Elliott CL, Brennand JE, Calder AA. The effects of mifepristone on cervical ripening and labor induction in primigravidae. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;92(5):804–809. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(98)00284-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wing DA, Fassett MJ, Mishell DR. Mifepristone for preinduction cervical ripening beyond 41 weeks’ gestation: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;96(4):543–548. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(00)00947-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Giacalone PL, Targosz V, Laffargue F, et al. Cervical ripening with mifepristone before labor induction: a randomized study. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;92(4 Pt 1):487–492. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(98)00225-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Berkane N, Verstraete L, Uzan S, et al. Use of mifepristone to ripen the cervix and induce labor in term pregnancies. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192(1):114–120. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.05.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brogden RN, Goa KL, Faulds D. Mifepristone. A review of its pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties, and therapeutic potential. Drugs. 1993;45:384–409. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199345030-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chwalisz K, Garfield RE. New molecular challenges in the induction on cervical ripening. Hum Reprod. 1998;13:245–252. doi: 10.1093/humrep/13.2.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garfield RE, Blennerhassett MG, Miller SM. Control of myometrial contractility: role and regulation of gap junctions. Oxf Rev Reprod Biol. 1988;10:436–490. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cheng L, Kelly RW, Thong KJ, et al. The effects of mifepristone (RU486) on prostaglandin dehydrogenase in decidual and chorionic tissue in early pregnancy. Hum Reprod. 1993;8:705–709. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a138124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cheng L, Kelly RW, Thong KJ, et al. The effect of mifepristone (RU486) on the immunohistochemical distribution of prostaglandin E and its metabolite in decidual and chorionic tissue in early pregnancy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1993;77:873–877. doi: 10.1210/jcem.77.3.8370712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]