Abstract

Introduction

Though high dose rate (HDR) intracavitary brachytherapy (ICBT) is now an integral part in the treatment of cervical cancer, the quest for optimum dose and fractionation schedule is still ongoing. While the American Brachytherapy Society recommends individual fraction size of <7.5 Gy, there are few studies where the authors obtained similar results with higher dose per fraction.

Objective

To compare and analyse two high-dose-rate intracavitary brachytherapy schedules—7 Gy per fraction for three fractions with 9 Gy per fraction for two fractions.

Materials and Methods

This is a prospective institutional study in Southern India carried on from 1 June 2012 to 31 March 2013. In this period, 124 patients of cervical cancer satisfying our inclusion criteria were treated with concurrent chemo-radiation, following which patients were randomized to one of the treatment arms, with 62 patients in each arm. The ICBT dose in Control Arm A was 7 Gy per fraction in three fractions, 1 week apart. While in Study Arm B, the ICBT dose was 9 Gy per fraction in two fractions, again 1 week apart. One patient in Arm A and three patients in Arm B discontinued the treatment even after repeated counselling and hence were excluded from the study analysis.

Results

The median follow-up period in the study was 25.2 months. In the Control Arm A, the 2-year actuarial local control rate, disease-free survival and overall survival were 88.5, 86.9 and 92.6 %, respectively, while in the Study Arm B, the 2-year actuarial local control rate, disease-free survival and overall survival were 91.5, 88.1 and 86.4 %, respectively.

Conclusion

In our experience, HDR brachytherapy with 9 Gy per fraction in two fractions is an effective dose fractionation when compared to 7 Gy per fraction in three fractions.

Keywords: ICBT, 9 Gy per fraction, 7 Gy per fraction

Introduction

Cervical cancer is the fourth most common malignancy in females worldwide [1] and the second most common malignancy in India [2].Cervical cancer in locally advanced stages are treated by external beam radiotherapy (EBRT) along with concurrent chemotherapy, followed by high-dose-rate (HDR) intracavitary brachytherapy (ICBT). Although, image-based brachytherapy is now the standard of treatment in most of the advanced centres of the world, orthogonal brachytherapy is still being rampantly done in the centres of the developing countries due to its affordability.

Even though there are more than four decades of published literature on the optimum dose fractionation schedules in HDR ICBT for the treatment of cervical cancer, there is still no uniform consensus on it [3, 4]. The American Brachytherapy Society (ABS) has recommended an individual fraction size of <7.5 Gy in four to eight fractions, depending on the dose per fraction. But they have also issued a caution along with these guidelines stating that the recommendation has not been thoroughly tested [5].

There have been few studies where the authors have demonstrated that HDR ICBT is also quite safe and equally effective if the dose per fraction is higher than 7.5 Gy, as opposed to the ABS [3, 6, 7]. Even before the ABS recommendations, in 1994, Patel et al. [8] demonstrated the efficacy of HDR ICBT with 9 Gy per fraction for two fractions when compared to the then standard of continuous low-dose-rate (LDR) ICBT with 35 Gy. The 9 Gy per fraction regime did not show any difference in terms of local control, distant failures, survival or toxicity.

Hence, the current study was undertaken to compare the two regimes of brachytherapy in cervical cancer in terms of local control, disease-free survival, overall survival and toxicity—7 Gy per fraction in three fractions(Control Arm A) and 9 Gy per fraction in two fractions (Study Arm B).

Materials and Methods

This is a prospective randomized controlled trial undertaken in a South Indian institution from 1 June 2012 to 31 March 2013 with 124 patients of locally advanced cervical cancer. Patients included in the study were of the age group between 35 and 70 years with International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) Stage IIB to IIIB with squamous cell histology. All the patients underwent EBRT with 50.4 Gy to the whole pelvis in two parallel-opposed anteroposterior fields (1.8 Gy per fraction, 5 fractions/week, with 6 MV photons via Linear Accelerator, in 28 fractions). In all the patients, central shielding was done after 25 fractions (45 Gy) to spare the rectum and bladder while maximizing dose to the parametrium and pelvic nodes. Along with EBRT, all the study patients were treated with at least four cycles of concurrent weekly cisplatin 40 mg/m2 as radiosensitizer. Patients were included in the study after written consent. Institutional ethical committee approval was taken.

Following EBRT, all patients were randomized to one of the HDR ICBT treatment schedules using computer-generated random numbers table. Patients in Control Arm A were treated with 7 Gy per fraction HDR ICBT in three fractions, each 1 week apart. Patients in Study Arm B were treated with 9 Gy per fraction in two fractions, each fraction being 1 week apart. One patient in Arm A and three patients in Arm B discontinued treatment even after repeated counselling and hence were excluded from the study analysis. The basic characteristics of the patients in the two arms are depicted in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics in both arms of the study

| Patient characteristics | Arm A (7 Gy/session; 61 patients), n (%) | Arm B (9 Gy/session; 59 patients), n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age group | ||

| <50 years | 16 (26.2) | 14 (23.7) |

| ≥50 years | 45 (73.8) | 44 (76.3) |

| FIGO stage | ||

| IIB | 19 (31.1) | 19 (32.2) |

| IIIA | 2 (3.3) | 3 (5.1) |

| IIIB | 40 (65.6) | 37 (62.7) |

| Number of cycles of concurrent weekly cisplatin | ||

| 4 cycles | 15 (24.6) | 19 (32.2) |

| 5 cycles | 42 (68.8) | 34 (57.6) |

| 6 cycles | 4 (6.6) | 6 (10.2) |

| Pretreatment haemoglobin levels | ||

| <10 gm/dl | 20 (32.8) | 25 (42.4) |

| ≥10 gm/dl | 41 (67.2) | 34 (57.6) |

FIGO International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics

So, the total biological effective dose (BED) delivered to Point A in Control Arm A = BEDEBRT + BEDICBT = [25 × 1.8 (1 + 1.8/10)] + [3 × 7 (1 + 7/10)] = 53.1 + 35.7 = 88.8 Gy. Equivalent dose in 2 Gy fraction (EQD2) to Point A in Control Arm A = BED/(1 + 2/10) = 74 Gy.

Similarly, the total BED delivered to Point A in Study Arm B = BEDEBRT + BEDICBT = [25 × 1.8 (1 + 1.8/10)] + [2 × 9 (1 + 9/10)] = 53.1 + 34.2 = 87.3 Gy. EQD2 to Point A in Study Arm B = BED/(1 + 2/10) = 72.75 Gy.

EBRT

EBRT was delivered with 6 MV photons via linear accelerator at 1.8 Gy per fraction, 5 fractions per week in two parallel-opposed anteroposterior fields up to a total dose of 50.4 Gy with central shielding done after 45 Gy. The radiation field was designed with superior border at the L4–L5 junction. The inferior border was kept at the lower border of the obturator foramen or still lower depending on the inferior extent of the disease. The lateral borders were planned 1.5–2 cm away from the lateral pelvic brim so as to include the pelvic nodes.

Chemotherapy

Along with EBRT, at least four cycles of concurrent weekly cisplatin at 40 mg/m2 were delivered.

ICBT

ICBT were performed in the minor operation theatre under proper analgesic coverage, without anaesthesia. The time gap between completion of EBRT and the starting of ICBT was kept between 4 days and 1 week. Adequate vaginal packing was done to minimize dose to the rectum and bladder. Orthogonal anteroposterior and lateral simulation X-ray films were taken after each ICBT application. Dose was prescribed to Point A and dose to bladder and rectum were calculated as per the International Commission on Radiation Units and Measurements (ICRU) Report 38 recommendations [9]. The dose to the rectum and bladder were kept below 80 % of the dose to the Point A, without compromising the Point A dose. Treatment was delivered using HDR MicroSelectron machine using Ir192 source.

All patients completed the planned treatment. The mean duration of overall treatment time was 61 days. The mean duration of overall treatment time in Control Arm A and Study Arm B were 63 and 58.9 days, respectively. Nine patients in Control Arm A and 17 patients in Study Arm B completed their overall treatment in 56 days.

Follow-Up

All the study patients were followed up after every 3 months in the first 2 years and after every 6 months thereafter. The patients were evaluated for local or distant failures and any treatment-related toxicities. Apart from a thorough clinical evaluation, proctoscopy and cystoscopy, other investigations like X-rays, CT scans, MRI scans and rectosigmoidoscopy were performed whenever indicated. Rectal and bladder toxicity were documented according to the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG)/European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) criteria [10].

Statistical Analysis

The two arms were compared in terms of local failure, distant failure, overall failure, disease-free survival, overall survival and treatment-related late toxicities. Local disease control, disease-free survival and overall survival were calculated from the date of treatment initiation. Treatment failures were classified as local pelvic failures or distant failures (extra-pelvic lymph nodal metastases, bones, viscera). All data were tabulated in MS Excel 2013. Statistical analysis was done using SPSS version 20. Statistical significance of difference in proportions was calculated by the Chi-square test. Local control, disease-free survival, overall survival and late complication rates were calculated by Kaplan–Meier method, and the differences between the two arms were analysed by log-rank test. p value <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

The median follow-up for the whole group of study patients was 25.2 months (range, 10.6–32.4 months). The median follow-up time for Control Arm A was 25.8 months (range, 17.5–32.4 months) and that of Study Arm B was 24.6 months (range, 10.6–31.2 months).

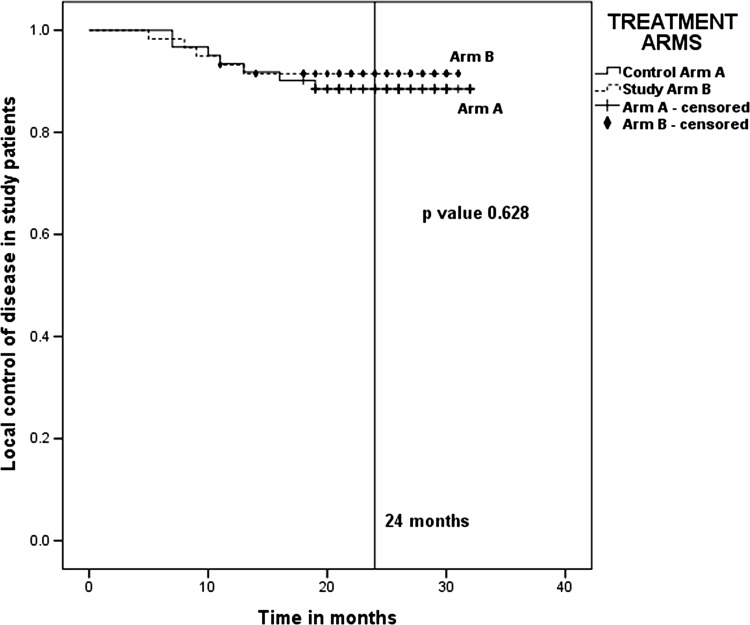

Local Control

The 2-year actuarial local control rates in Control Arm A and Study Arm B were 88.5 and 91.5 %, respectively (Fig. 1). Even though the local control rates were higher in Study Arm B as compared to Control Arm A, the difference between the two arms was not statistically significant (p value 0.628).

Fig. 1.

Actuarial local control in 2 years—88.5 % for Arm A (7 Gy × 3) and 91.5 % for Arm B (9 Gy × 2). p value 0.628

Patterns of Failure

There were 11.5 % (7 out of 61) and 8.5 % (5 out of 59) local failures in Arm A and Arm B, respectively. In all the patients with local failure, the site of failure was cervix alone. Distant metastasis was seen in 4.9 % (3 out of 61) and 5.1 % (3 out of 59) in Arm A and Arm B, respectively. Distant metastases were seen mostly in the para-aortic lymph nodes and supraclavicular lymph nodes. Overall failure was seen in 13.1 and 11.9 % patients in Arm A and Arm B, respectively (Table 2).

Table 2.

Patterns of failure in the two brachytherapy treatment arms

| Patterns of failure | Arm A (7 Gy/session; 61 patients), n (%) | Arm B (9 Gy/session; 59 patients), n (%) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Local failure alone | 5 (8.2) | 4 (6.8) | 0.768 |

| Distant failure alone | 1 (1.6) | 2 (3.4) | 0.539 |

| Local along with distant failure | 2 (3.3) | 1 (1.7) | 0.579 |

| Overall failure | 8 (13.1) | 7 (11.9) | 0.836 |

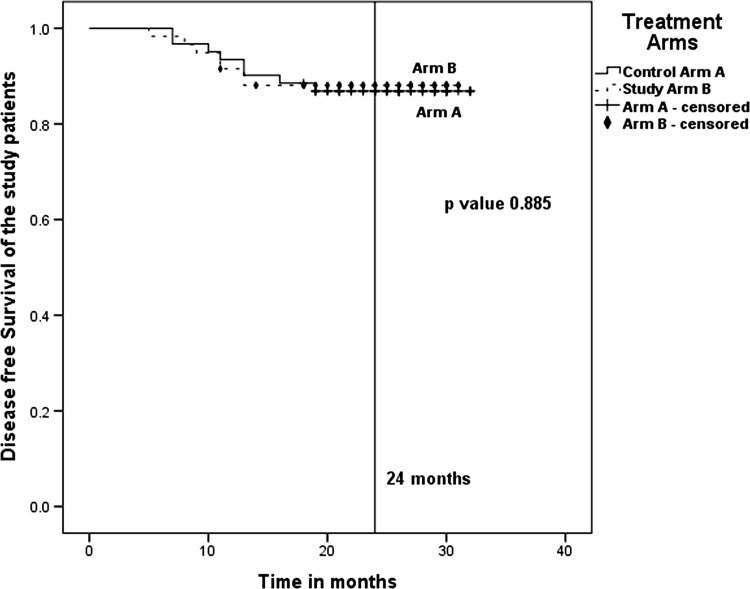

Disease-Free Survival

The actuarial 2-year disease-free survival in Arm A and Arm B were 86.9 and 88.1 %, respectively (Fig. 2). Although, the disease-free survival was higher in the Study Arm B, there was no statistically significant difference (p value 0.885) when compared to that of Control Arm A.

Fig. 2.

Actuarial 2-year disease-free survival—86.9 % for Arm A (7 Gy × 3) and 88.1 % for Arm B (9 Gy × 2). p value 0.885

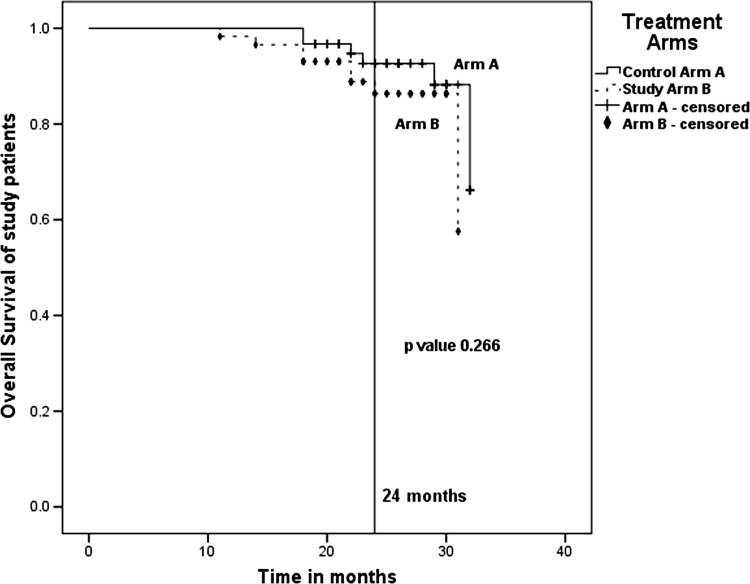

Overall Survival

The 2-year overall survival in Arm A and Arm B were 92.6 and 86.4 %, respectively (Fig. 3), although the difference did not reach any statistical significance (p value 0.266).

Fig. 3.

Actuarial 2-year overall survival—92.6 % for Arm A (7 Gy × 3) and 86.4 % for Arm B (9 Gy × 2). p value 0.266

Late Toxicities

Late toxicities were graded according to the RTOG/EORTC criteria (Table 3). Late toxicities were seen in 24 patients in Arm A and in 33 patients in Arm B. Grade III or more severe late toxicity was seen in only one patient in Arm B, where there was heavy rectal bleeding requiring surgical exploration. The 2-year actuarial risk of developing any late rectal toxicity in Arm A and Arm B were 27.9 and 39 %, respectively. The 2-year actuarial risk of developing late bladder toxicity in Arm A and Arm B were 13.1 and 22 %, respectively. Although there was increased overall late toxicity in Arm B when compared to Arm A, the difference was not statistically significant (p value 0.69).

Table 3.

Late toxicities

| Late toxicity | Arm A (7 Gy × 3) (n = 24) | Median time to toxicity (months) | Arm B (9 Gy × 2) (n = 33) | Median time to toxicity (months) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rectal | |||||

| Grade I | 14 | 17 | |||

| Grade II | 3 | 9.2 | 5 | 8.3 | 0.197 |

| Grade III | 1 | ||||

| Bladder | |||||

| Grade I | 7 | 25.3 | 11 | 24.4 | 0.199 |

| Grade II | 1 | 2 | |||

Discussion

ICBT plays a pivotal role in the treatment of cervical cancer. Previously, patients were treated successfully with low-dose-rate (LDR) brachytherapy. But LDR ICBT had few problems like need for hospitalization of the patient, prolonged applicator insertion period, radiation exposure to the medical personnel [5]. Gradually in the last three to four decades, there has been a shift in the practice pattern. Now, in most of the places, HDR ICBT is the standard of care following EBRT in a patient of carcinoma of the uterine cervix. HDR ICBT has the advantages of shorter treatment time and better geometric placement. So, in spite of its radiobiologic disadvantages of greater probability of late effects, HDR ICBT gained popularity [7].

The probability of late effects has been lowered by fractionation and adjustment of the total dose in HDR ICBT [6]. To determine the optimum fractionation in HDR ICBT, radiation oncologists have used bioeffect dose models, which convert HDR doses to LDR equivalent doses. The LQ model is the most commonly used dose model. But clinical experiences did not always match with this model. Petereit et al. [11] disagreed on this note stating that the HDR brachytherapy literature had inadequate details on dose fractionation schedules, thereby questioning the validity of the LQ model.

Orton et al. [12] in one of their study on HDR ICBT demonstrated that late complication rates were much high when individual fraction size of >7 Gy was used, even though the effect on tumour control was same when compared to HDR brachytherapy with ≤7 Gy per fraction [13]. But in a later study by Orton, the author concluded that individual fraction size in HDR brachytherapy may be between 4 and 9 Gy, but it is important to minimize the dose to the rectum and bladder by means of proper vaginal packing or retraction.

The ABS recommended that the individual fraction size in HDR brachytherapy should be <7.5 Gy with four to eight fractions. But they also added that these recommendations were not adequately tested and were not superior to clinical experience [5].

Patel et al. [6–8], Sood et al. [3] and Souhami et al. [14] have described their experiences with >7.5 Gy per fraction HDR ICBT dose and reported their fractionation schedules to be safe and effective in the treatment of cervical cancer. In the current study, it was found that 9 Gy per fraction in two fractions had better efficacy (though not statistically significant) than that of 7 Gy per fraction in three fractions in terms of local tumour control. This may be because more number of patients in Arm B (17 patients) completed their treatment within 56 days as compared to Arm A (9 patients) due to the lesser number of fractions used in Arm B. Some may argue the initiation of ICBT in the Arm A during the last week of EBRT, but the treatment-related toxicities and the non-compliance of patients in our set-up often limit this possibility.

Earlier studies on HDR ICBT with 9 Gy per fraction in two fractions [3, 6–8] have failed to find any significantly increased toxicity with the regime. Similarly, in the current study, there was no significantly increased toxicity with HDR ICBT using 9 Gy per fraction in two fractions. There was only one Grade III toxicity seen in the study period, in the Arm B.

Conclusion

In the treatment of cervical carcinomas, HDR ICBT with 9 Gy per fraction in two fractions is as effective as that of 7 Gy per fraction in three fractions in terms of tumour control and survival. Although the late toxicities are significantly higher with the 9 Gy per fraction HDR ICBT schedule when compared to that of 7 Gy per fraction, most of them are of early grade and thereby easily manageable. In Indian setting, it results in better patient compliance and cost-effectiveness by reducing the number of fractions. A similar multi-institutional study with larger sample size and longer period of follow-up is strongly recommended.

Dr. Saptarshi Ghosh

is currently working as a Senior Resident in the Department of Radiation Oncology, GSL Medical College, Rajahmundry, Andhra Pradesh. He stood university first in the Dr. NTR University of Health Sciences in M.D. Radiotherapy in 2015. He was awarded with the Neil Joseph Fellowship by Association of Radiation Oncologists of India (AROI) in 2014 after completing his training in Tata Memorial Hospital, Mumbai. He was also awarded with the Young Radiation Oncology Fellowship in 2014. He has published a few papers in international PubMed indexed journals and has been a reviewer for few journals like BMJ Case Reports, Gynecologic Oncology. He is also the Editorial Board Member of few journals.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

None.

Ethical Standards

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Research involving human participants—Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Footnotes

Dr. Saptarshi Ghosh M.B.B.S, M.D. is Radiation Oncologist at GSL Cancer Hospital, GSL Medical College & General Hospital, Rajahmundry, Andhra Pradesh, India.

References

- 1.GLOBOCAN 2012: Estimated cancer incidence, mortality and prevalence worldwide in 2012, World Health Organization. http://www.globocan.iarc.fr/old/FactSheets/cancers/cervix-new.aspx. Last Accessed on 4 Nov 2014.

- 2.Burden of HPV related cancers. Human Papillomavirus and Related Diseases Report India. http://www.hpvcentre.net. Last Accessed on 15 Oct 2014.

- 3.Sood BM, Gorla G, Gupta S, et al. Two fractions of high-dose-rate brachytherapy in the management of cervix cancer: clinical experience with and without chemotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2002;53:702–706. doi: 10.1016/S0360-3016(02)02745-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nakano T, Kato S, Ohno T, et al. Long-term results of high-dose rate intracavitary brachytherapy for squamous cell carcinoma of the uterine cervix. Cancer. 2005;103:92–101. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nag S, Erickson B, Thomadsen B, et al. The American Brachytherapy Society recommendations for high-dose-rate brachytherapy for carcinoma of the cervix. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2000;48(1):201–211. doi: 10.1016/S0360-3016(00)00497-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Patel FD, Kumar P, Karunanidhi G, et al. Optimization of high-dose-rate intracavitary brachytherapy schedule in the treatment of carcinoma of the cervix. Brachytherapy. 2011;02(10):147–153. doi: 10.1016/j.brachy.2010.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Patel FD, Rai B, Mallick I, et al. High-dose-rate brachytherapy in uterine cervical carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;62:125–130. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2004.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patel FD, Sharma SC, Negi PS, et al. Low dose rate versus high dose rate brachytherapy in the treatment of carcinoma of the uterine cervix: a clinical trial. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1994;28(2):335–341. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(94)90055-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.ICRU Report #38. Dose and volume specification for reporting intracavitary therapy in oncology. International Commission on Radiation Units and Measurements. Bethesda. March 1985:1.

- 10.Cox JD, Stetz J, Pajak TF. Toxicity criteria of the radiation therapy oncology group (RTOG) and the European organization for research and treatment of cancer (EORTC) Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1995;31:1341–1346. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(95)00060-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Petereit DG, Pearcey R. Literature analysis of high dose rate brachytherapy fractionation schedules in the treatment of cervical cancer: is there an optimal fractionation schedule? Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1999;43:359–366. doi: 10.1016/S0360-3016(98)00387-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Orton GC, Seyedsadr M, Somnay A. Comparison of high and low dose rate remote after loading for cervix cancer and the importance of fractionation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1991;21:1425–1434. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(91)90316-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Orton GC. Width of the therapeutic window: what is the optimal dose-per-fraction for high dose rate cervix cancer brachytherapy? Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1995;31:1011–1013. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(94)00664-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Souhami L, Corns R, Duclos M, et al. Long-term results of high-dose rate brachytherapy in cervix cancer using a small number of fractions. Gynecol Oncol. 2005;97:508–513. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2005.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]