Abstract

Background

The main documented indication of intrapartum caesarean section is foetal distress (MacKenzie and Cooke in BMJ 323(7318):930, 2001). Foetal distress indicates foetal hypoxia and acidosis during intrauterine life.

Purpose

To correlate the diagnosis of foetal distress and perinatal outcome.

Methods

This was a prospective observational study of women who underwent caesarean section for foetal distress as detected by cardiotocography and not responding to intrauterine resuscitation. The foetal Apgar score at 1 and 5 min was recorded and cord blood pH was measured in all cases. The neonatal outcome was studied with regard to the need for supportive ventilation and admission to NICU/nursery.

Results

In our study, 14.38 % cases diagnosed with foetal distress subsequently had poor outcome. Twenty-one babies had a 5-min Apgar score <7, required immediate resuscitation and were admitted in NICU. Twelve foetuses had a 1-min Apgar score <4, while there were three cases of severe birth asphyxia (Apgar score <4 at 5 min); of these, two babies died. The neonatal outcome was poorer in cases with associated complicating factors.

Conclusion

The diagnosis of foetal distress is imprecise and a poor predictor of foetal outcome—the result is a tendency for unnecessary caesarean sections. On the contrary, lack of adverse outcome could reflect that our unit makes decisions at a time before clinically significant foetal compromise occurs.

Keywords: Caesarean section, Foetal distress, Cardiotocography, Perinatal outcome

Introduction

The most common indication of intrapartum caesarean section is foetal distress for the past few decades [1, 2]. The diagnosis of foetal distress made on the basis of foetal heart rate abnormalities as detected by electronic foetal monitoring has led to a high rate of caesarean deliveries without the foetuses being adversely affected [3–5]. This high rate of caesarean section for foetal distress is attributed to the widespread use of electronic foetal monitoring for diagnosing abnormal foetal heart rate patterns [6]. However, not all foetuses with the abnormal foetal heart rate pattern detected on cardiotocography have adverse outcomes at birth.

Hence, there is a need to assess the efficacy of electronic foetal monitoring. Keeping this issue into consideration, this study was undertaken to analyse the correlation between caesarean section for foetal distress and perinatal outcome and to see what foetal heart rate patterns are associated with adverse perinatal outcome.

Materials and Methods

It was a prospective observational study done in our hospital which is a referral centre. A total of 146 women were included in the study who underwent emergency caesarean section for foetal distress during labour as detected by cardiotocography and not responding to intrauterine resuscitation. Intrauterine resuscitation included change in maternal position, oxygen administration and intravenous hydration. Exclusion criteria were congenital anomalies, abnormal presentation, multiple gestation and gestational age <36 weeks.

Maternal age, parity, associated high-risk factors and abnormal foetal heart rate patterns which led to the diagnosis of caesarean section were recorded. Birth weight, foetal Apgar score at 1 and 5 min and umbilical artery pH at birth were recorded. Neonatal outcome was studied with regard to the need for supportive ventilation and admission to NICU/nursery.

Results

From May to August 2010, a total number of 6039 patients were delivered in our hospital at ≥36-week gestation. Out of these, 146 (18.024 %) patients underwent emergency caesarean section primarily for non-reassuring foetal heart rate patterns, while the total number of caesarean sections for various indications was 810.

The mean age of the patients in the study group was 24.5 years. Seventy-four (50.68 %) women were primigravida, 43 (29.45 %) were gravida 2, while 29 (19.87 %) were gravida 3 or more.

The various foetal heart abnormalities picked up by CTG for which caesarean section was done and associated neonatal outcome are given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Various foetal heart abnormality and related adverse neonatal outcomes

| Foetal heart abnormality | Number of patients | Adverse neonatal outcome | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AS <7 at 5 min | Cord pH <7.20 | NICU admission | ||

| Persistent bradycardia | 104 (71.23 %) | 12 | 7 | 12 |

| Variable decelerations | 17 (11.64 %) | 3 | 2 | 3 |

| Late decelerations | 22 (15.07 %) | 5 | 2 | 5 |

| Tachycardia | 3 (2.06 %) | 1 | 1 | 1 |

The most common foetal heart abnormality of suspected foetal distress found was persistent bradycardia in 104 cases followed by late deceleration in 22 cases and variable deceleration in 17 cases. There were 16 (10.9 %) patients who had more than one foetal heart abnormality.

In our study, 14.38 % (21/146) of cases diagnosed with foetal distress subsequently had a poor outcome. Out of 146 patients of caesarean section for suspected foetal distress, the 1-min Apgar score was <4 in 12 women, while the 5-min Apgar score was <7 in 21 women. Twenty-one babies required immediate resuscitation and were admitted in NICU. There were three cases of severe birth asphyxia (Apgar score <4 at 5 min); of these, two babies died, one after 15 min of birth and the second one on day five. The indication of caesarean section was severe preeclampsia and antepartum haemorrhage with placenta praevia, respectively. The foetal heart abnormality was persistent bradycardia in both the cases, while the cord pH was 6.12 and 6.95, respectively. There were 125 (85.6 %) neonates who did not show any adverse outcome.

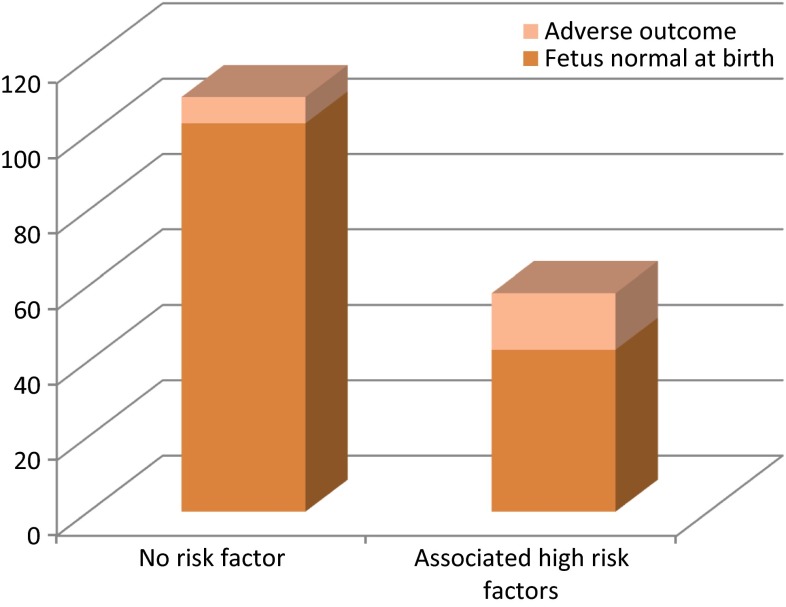

We also analysed the intraoperative findings, foetal birth weight and associated complications in these women and compared the neonatal outcome in cases with associated complicating factors with those who had no risk factor. Associated complicating factors included antepartum haemorrhage, IUGR, oligohydramnios, hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, cord prolapse, cord loop around neck, meconium staining of amniotic fluid and second stage arrest. In 103 (70.56 %) cases, there was no associated risk factor, while the remaining 43 (29.45 %) had one or more associated complicating factors. Fifteen foetuses were admitted in NICU or needed supportive ventilation in women with associated risk factors, while only seven foetuses in those with no associated risk factors.

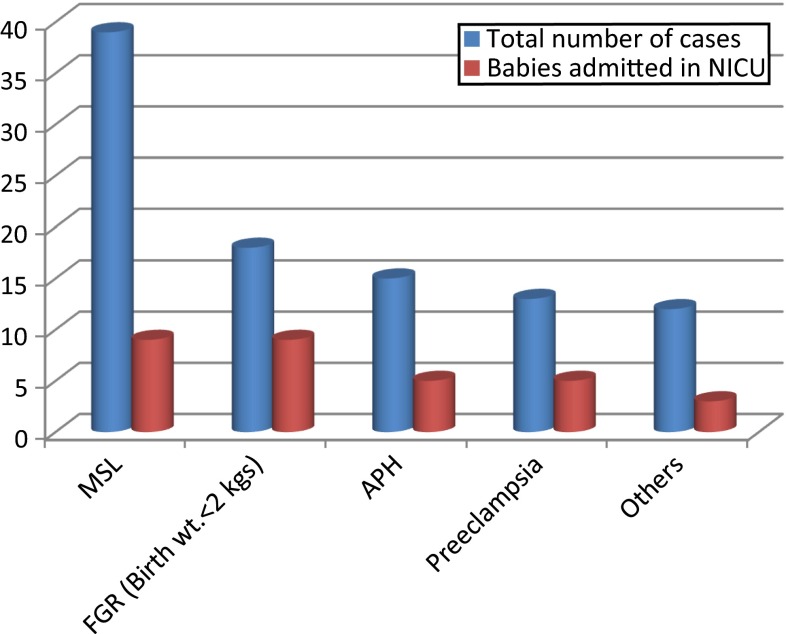

Hence, the neonatal outcome was poorer if there were associated complicating factors (Fig. 1), and this was found to be statistically significant using χ2 test. (p < 0.001). The outcome was worst in growth-restricted babies with maximum number of babies (50 %) in this group requiring resuscitation and admission in NICU (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Neonatal outcome in cases with and without associated complicating factors

Fig. 2.

Relation of neonatal outcome with associated high-risk factors

Discussion

Continuous electronic foetal monitoring is probably the most common form of intrapartum foetal assessment used currently [7]. It is a widely accepted method of foetal monitoring during labour with the goal of identifying foetuses with hypoxia during labour. However, the main risk of widespread application of continuous monitoring has been the observed risk of caesarean delivery noted in retrospective and prospective studies [8, 9].

As observed in our study, the rate of caesarean section for foetal distress was 18.02 %, and out of this, only 14.38 % foetuses were actually distressed implying the limitation of cardiotocography in predicting early neonatal outcomes on the basis of non-reassuring foetal heart rate patterns.

Hence, the prediction of foetal hypoxia and acidosis on the basis of non-reassuring foetal heart rate patterns is sufficiently low to have led to the observation that many caesarean deliveries are retrospectively found to have been unnecessary.

It has also been observed in various studies that CTG interpretation is inconsistent and may fail to predict early neonatal outcome [10].

The role of the more invasive foetal scalp blood sampling to determine pH values has been challenged, and it is not used as commonly as in the past [11].

The increased citation of foetal distress as an indication of caesarean section during the last two decades raises the suspicion that electronic foetal monitoring interpretation has become more reflective of the legal climate than of the foetal condition [10].

This limitation of CTG in predicting adverse neonatal outcomes has led to the development of newer technologies like ECG to improve the predictive value of foetal monitoring. Currently, the use of ST analysis of the foetal ECG in conjunction with conventional CTG has been shown to reduce both the rates of operative deliveries for foetal distress and metabolic acidosis during birth [12].

It has been observed in various randomized controlled trials that the use of foetal ECG in conjunction with CTG has improved the specificity of intrapartum foetal monitoring leading to reduction in rates of operative deliveries for foetal distress [13, 14]. Hence, the use of such ancillary methods in addition to CTG is the way forward.

Conclusion

We observed in our study that the abnormal foetal heart rate patterns detected by CTG do not correlate well with early neonatal outcome resulting in a high rate of unnecessary caesarean deliveries. The correlation was, however, better in women with associated complicating factors as there was significantly higher NICU admission rate in babies born to them.

Our study therefore implies three things. Firstly, increasing numbers of caesarean sections are being performed for foetal distress. Secondly, the diagnosis of foetal distress is imprecise and a poor predictor of foetal outcome. Finally, the result is an increased number of unnecessary caesarean deliveries.

On the contrary, lack of adverse outcome could reflect that our unit makes decisions at a time before clinically significant foetal compromise occurs.

The use of other modalities like foetal ECG as an adjunct to CTG may help in improving the predictive value of foetal monitoring. In addition an overall assessment of the patient’s details may help to differentiate between foetuses that require prompt delivery and the foetus not actually in acute distress.

Dr. Richa Gangwar (MS, DNB)

has graduated from King George Medical University, Lucknow, in 2005. She passed MS OBGYN in 2008. She worked as a Senior Resident in Lady Hardinge Medical College, New Delhi, from June 2008 to September 2010. She has one paper published on “Gall bladder disease in pregnancy” in the Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology of India, and several articles are under review. She has keen interest in high-risk pregnancy and foetal medicine.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

Richa Gangwar and Sarita Chaudhary declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008(5).

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all patients for being included in the study.

Footnotes

Dr. Richa Gangwar is a Senior Resident in Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology at Lady Hardinge Medical College. Dr. Sarita Chaudhary is an Assistant Professor in Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology at Lady Hardinge Medical College.

Contributor Information

Richa Gangwar, Phone: +91 9621632872, Email: richagangwar24@gmail.com.

Sarita Chaudhary, Phone: +91 9999349494, Email: sarita72@gmail.com.

References

- 1.MacKenzie IZ, Cooke I. Prospective 12 month study of 30 minute decision to delivery intervals for “emergency” caesarean section. BMJ. 2001;322:1334–1335. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7298.1334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tufnell DJ, Wilkinson K, Beresford N. Interval between decision and delivery by caesarean section—Are current standards achievable? Observational case series. BMJ. 2001;322:1330–1333. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7298.1330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hornbuckle J, Vail A, Abrans KR, et al. Bayesian interpretation of trials: the example of intrapartum electronic fetal heart rate monitoring. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 2000;107:3–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2000.tb11571.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oloffson P. Current status of intrapartum fetal monitoring: cardiotocography versus cardiotocography + ST analysis of the fetal ECG. Eur J Obstet Gynaecol Rep Biol. 2003;110:S113–S118. doi: 10.1016/S0301-2115(03)00181-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nielson JP, Grant AM. The randomized trials of intrapartum electronic fetal monitoring. In: Spencer JA, Ward RH, editors. Intrapartum fetal surveillance. London: RCOG Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 6.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 106: Intrapartum fetal heart rate monitoring: nomenclature, interpretation, and general management principles. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114(1):192–202. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181aef106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.American college of obstetrics and gynaecology Fetal heart rate patterns: monitoring, interpretation and management. American College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Technical Bulletin. 1995;207:182–189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thacker SB, Strout D, Chang M. Continuous electronic heart rate monitoring for assessment during labor. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001;2:CD000063. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Neilson JP. Fetal electrocardiogram (ECG) for fetal monitoring in labor. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;2:CD000116. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dellinger EH, Boehm FH, Crane MM. Electronic fetal heart rate monitoring: early neonatal outcomes associated with normal rate, fetal stress and fetal distress. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;182:214–220. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9378(00)70515-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goodwin TM, Milner Masterson L, Paul R. Elimination of fetal scalp blood sampling on a large clinical service. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;83:971–974. doi: 10.1097/00006250-199406000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Amer-Wahlin I, Hellsten C, Noren H, et al. Cardiotocography only versus cardiotocography plus ST analysis of fetal electrocardiogram for intrapartum fetal monitoring: a Swedish randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2001;358(9281):534–538. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)05703-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reed NN, Mohajer MP, Sahota DS, et al. The potential impact of PR interval analysis of the fetal electrocardiogram (FECG) on intrapartum fetal monitoring. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Rep Biol. 1996;86:87–92. doi: 10.1016/0301-2115(96)02496-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wijngarden WJV, Strachan BK, Sahota DS, et al. Improving intrapartum surveillance: An individualized T/QRS ratio? Eur J Obstet Gynecol Rep Biol. 2000;88:43–48. doi: 10.1016/S0301-2115(99)00119-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]