Abstract

Background

MMR has always been recognized as an important indicator of quality of health services. The MMR in India has so far not reached up to the required MDG 2015. If we look into this matter with the eagle’s eye view, then there are certain gray areas which need attention. For this, it is not the maternal mortality but the maternal near miss which has to be focused.

Objectives

To audit the maternal near miss in our institution and to review the pathways that lead to severe maternal morbidity and death.

Methods

Prospective observational study from September 2013 to August 2015 in Dr. Bhim Rao Ambedkar Memorial Hospital, Raipur. Maternal near miss cases were identified based on WHO criteria 2009, recorded, and studied.

Results

There were 13,895 live births, 211 maternal near miss, and 102 maternal deaths. Maternal near miss to mortality ratio was 2:1. Maternal near miss incidence ratio was 15.18/1000 live births. Mortality index was 32.58 %. Hemorrhage and hypertensive disorders of pregnancy toped the list of the leading causes of near miss morbidity. The near miss events were more common in the primipara (39 %), with age group 21–30 years and in the third trimester at the time of admission.

Conclusion

Auditing maternal near miss can help in reducing their morbidity and mortality in our institution. Similar audit between other institute, state, and countries may help to hasten the slow progress of reducing maternal mortality.

Keywords: Maternal near miss, Maternal death, Maternal near miss audit

Introduction

Death of a mother during childbirth hits the backbone of the family. Family as a unit is shattered with maternal death. Every day worldwide 1600 women die of the complications of pregnancy [1]. The depressing fact behind this figure is that most of the maternal deaths are preventable. India and Nigeria contribute to one-third of global maternal mortality [2]. Behind each maternal death, there are many more women with similar pathophysiological conditions who escape death somehow. In developed countries the maternal deaths have reached a plateau, and the limited number of deaths makes it impossible to scrutinize and form an opinion. Thus, the interest shifted to maternal near miss (MNM), which is more in number as compared to maternal deaths (MD). Maternal near miss is defined as “a woman who nearly died but survived a complication that occurred during pregnancy, childbirth, or within 42 days of termination of pregnancy.” The present study is done to recognize these women and review the common pathways leading to severe morbidity and death.

Objectives

To audit the maternal near miss in our institution and to review the pathways that lead to severe maternal morbidity and deaths.

Materials and Methods

This was a prospective observational study carried out among women admitted in obstetrical ward/obstetrical ICU, fulfilling WHO maternal near miss criteria (2009), in Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Dr. Bhim Rao Ambedkar Hospital, Raipur, from September 2013 to August 2015. Relevant sociodemographic and clinical profile were noted. Clinical examination and investigations were carried out. Women were categorized as per laboratory, clinical, and management-based criteria laid down by WHO 2009. The collected data were recorded and analyzed.

The following indices were calculated: (1) Maternal near miss incidence ratio (MNMIR) refers to the number of near miss cases per 1000 live births. MNMIR = MNM/LB.

(2) Maternal near miss to mortality ratio—near miss to maternal deaths ratio. MNM–MD.

Above study was carried out after approval from ethical committee of our institution.

Results

During the study period, there were a total of 211 near miss and 102 maternal deaths, thus giving a ratio of maternal near miss to maternal mortality as 2:1, reflecting a good maternal care in the institution. This ratio would have been better and higher if the number of referrals were not included which were about 52.6 %.

There were 13,895 live births during study period giving maternal near miss incidence ratio (MNMIR) of 15.18/1000 live births.

There was no significant difference between maternal near miss due to clinical (31 %) and laboratory-based criteria (30 %). The management-based criteria, however, had a higher incidence of maternal near miss (39 %).

Table 1 shows the relevant sociodemogarphic and clinical profile of patients. Delay was present in 68.88 % cases. Type 1 (delay in decision to seek care) and Type 2 delay (delay in reaching healthcare center) were more common (44 and 36 %).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and clinical profile (n = 211)

| Age | Number of patients |

| <20 years | 29 (13.74 %) |

| 21–30 years | 149 (70.61 %) |

| >31 years | 33 (15.63 %) |

| Gravidity | |

| Primi | 82 (38.86 %) |

| Multi | 129 (61.13 %) |

| Delays | |

| Type 1 | 65 (44.07 %) |

| Type 2 | 53 (36.01 %) |

| Type 3 | 28 (19.90 %) |

| Underlying condition | |

| Hypertensive disorder | 70 (33.17 %) |

| Obstetric hemorrhage | 58 (27.48 %) |

| Rupture uterus | 14 (06.63 %) |

| Septic abortion | 09 (04.26 %) |

| Education status | |

| Illiterate | 56 (26.54 %) |

| Primary education | 116 (54.97 %) |

| Secondary education | 28 (13.27 %) |

| Higher secondary | 04 (01.89 %) |

| Graduate | 07 (03.31 %) |

Among the direct causes of maternal near miss, hypertensive disorders of pregnancy was the most common cause (38.8 %) followed by hemorrhage (22.2 %). Severe anemia was the most common indirect cause(57 %). Hematological system was the most system to be involved (36.49 %), (Table 2).

Table 2.

Most common organ system involved (n = 211)

| Organ dysfunction | Number of patients |

|---|---|

| Coagulation/hematological | 77 (36.49 %) |

| Respiratory | 39 (18.48 %) |

| Hepatic | 37 (18.00 %) |

| Cardiovascular | 33 (15.63 %) |

| Renal | 11 (05.21 %) |

| Uterine (hysterectomy) | 08 (03.79 %) |

| Neurological | 07 (03.31 %) |

Eight women out of 211 maternal near miss cases were conservatively managed, discharged, and continued their pregnancy. Nearly 29.8 % (n = 63) women needed surgical interventions. Most commonly performed procedures were B/L uterine artery ligation (16), B/L internal iliac artery ligation (12), B-lynch suture application (5), repair of rupture uterus (8), obstetric hysterectomy (8), MY suture application (3), salpingectomy (2), and uterine horn removal (1). There were eight women who had more than one intervention.

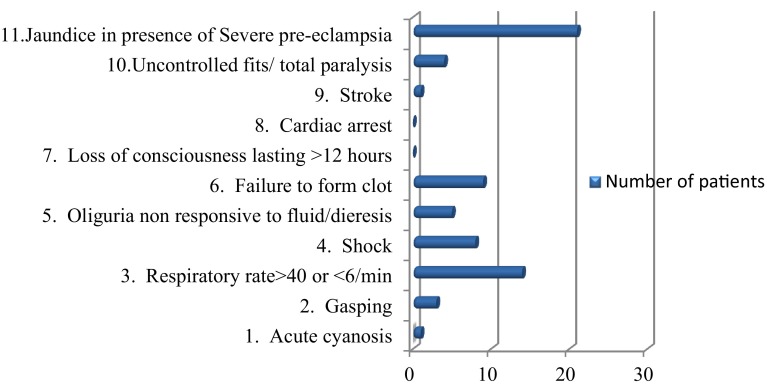

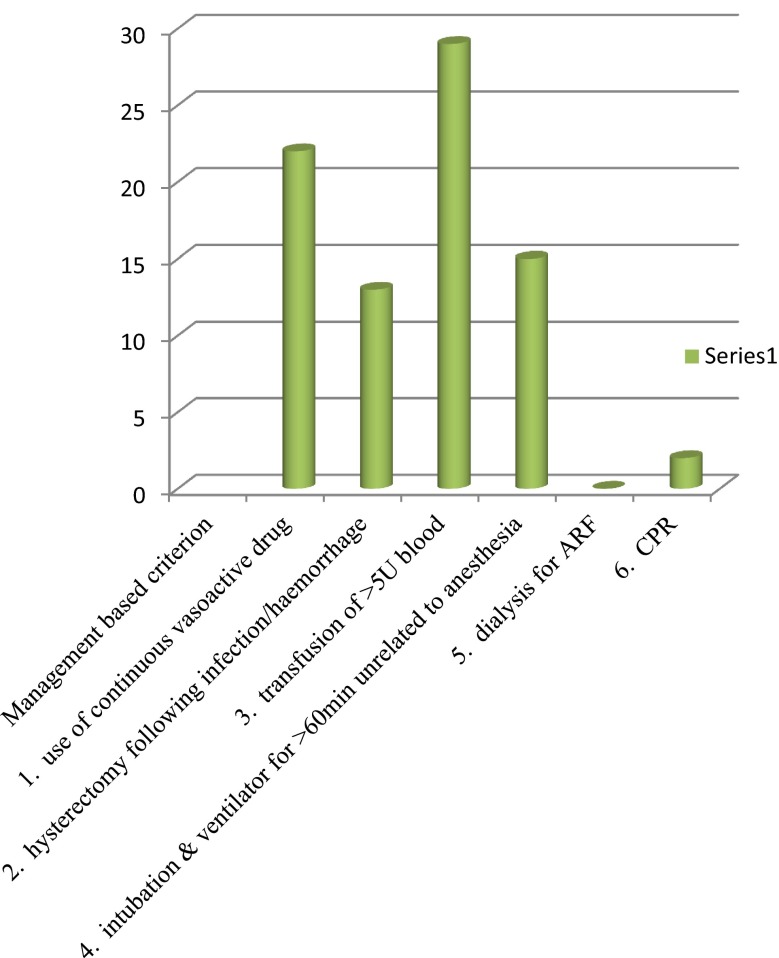

The most common clinical criteria were jaundice in presence of pre-eclampsia (Fig. 1), and accordingly the laboratory-based criteria was acute thrombocytopenia in (Fig. 2). Blood transfusion of more than five units was required in 35 % women (Fig. 3).

Fig. 1.

Distribution as per clinical criteria

Fig. 2.

Distribution as per laboratory criteria

Fig. 3.

Distribution as per management-based criteria

Discussion

Every problem has a solution and the solution lies in understanding the roots of the problem. Reducing maternal mortality effectively needs more insight not only on maternal deaths but also the maternal near miss in a given region, as most of the time they have common pathways. Prevalence of maternal near miss was found to be 1.5 %. Various other Indian studies have shown a huge variation in the prevalence ranging from 0.4 to 4.4 % (Table 3). Higher numbers imply that there are more sick mothers who survived the disaster. Prevalence in the neighborhood countries like Nepal and Sri Lanka was found to be 2.3 % [3] and 1.11 % [4], respectively.

Table 3.

Indian studies on maternal near miss

| Indian Studies | MNMR (per 1000 live birth) | Prevalence (%) | Near miss: death ratio | Mortality index (%) | Most common direct causes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Khosla et al. 2000 | – | 4.4 | 7:1 | – | Hemorrhage (30 %), hypertension (23 %), S. anemia (16 %) |

| Taly et al. 2001 | – | 4.4 | 6.2:1 | 13.79 | Hemorrhage (60 %), hypertension (34 %), sepsis (4 %) |

| Chhabra 2008 | – | 3.3 | 31.5:1 | – | Hemorrhage (34 %), eclampsia (34 %), sepsis (34 %) |

| Sharma et al. Assam 2014 [9] | 42.10 | 3.8 | 3.9:1 | 20.4 | Hemorrhage (42 %), eclampsia (39 %), severe anemia (18 %) |

| Roopa et al. Karnataka 2013 [14] | 17.80 | 1.7 | 5.6:1 | 14.9 | Hemorrhage (44 %), hypertensive disorders (23 %), sepsis (16 %) |

| Das et al. Kolkata 2013 [15] | 16.20 | – | 5.6:1 | 9.17 | Pregnancy-induced hypertension, hemorrhage |

| Kalra et al. Rajasthan 2015 [16] | 4.18 | 0.4 | 2.07:1 | 32.53 | Hemorrhage (28 %), hypertension (17 %), sepsis (5 %) |

| Madhavi et al. Telangana 2014 [13] | 9.20 | 0.9 | 11:1 | 8.3 | Abruption, rupture uterus |

| Bakshi et al. Uttarakhand 2015 [17] | 7.41 | – | 5.4:1 | 16.39 | Postpartum hemorrhage (42 %), severe pre-eclampsia (23 %), sepsis |

| Singh et al. 2015 (present study) | 15.18 | 1.5 | 2:1 | 32.58 | Hypertensive disorder of pregnancy, hemorrhage |

MNMR maternal near miss ratio

An overall delay was present in 68.88 %. In spite of this being a tertiary center, there was 20 % delay in receiving adequate treatment. Most of this delay was due to very busy OT due to overcrowding and proportionately less staff. Despite a well-equipped blood bank, at times there is unavoidable delay in issue due to cross-matching and other testing. Also, sometimes there is less than required units of blood and its products available for women needing urgent blood transfusion. Retrospective database study which included studies from Asia, Africa, and Latin America conducted at Oxford University, UK, found lack of blood products and insufficient infrastructure among top five causes for Type 3 delay [5]. Study at Myanmar also showed that the Type 1 delay continues to be the major cause of delay [6], but this was in contrast to study conducted by Rodolfo et al. [7] in Brazil found Type 2 delay to be more common.

Since the year 2007, the institutional deliveries are being promoted through JSY aided by transportation system (in our state Ambulance 102 called as “Mahatari express” and Ambulance 108 as “Sanjeevani”). This has led to an enormous workload on the department. It has increased by 58.16 % without any additional facilities over the past. Recent coverage evaluation survey also showed an increase of 72.9 % in institutional delivery [8]. What is deficit in current scenario is lack of adequate resources to efficiently cater this increased health demand.

Hemorrhage, hypertensive disorder, and sepsis continue to be the killer trio in our country. Indian studies (Table 3) have also shown that hemorrhage and eclampsia are the most common causes of maternal deaths.

A timely surgical intervention in our hospital, in about 29 % of maternal near miss has proved to be life saving in these women. Presence of facilities, availability of skilled surgeons and appropriate intervention under the time line has improved our morbidity rates. B-lynch operations and step-wise devascularization have helped us achieve good results when done promptly within few minutes of failed medical management.

As we look to the problem as a whole we often miss the artist playing its role behind the curtains. Similarly a key factor behind maternal near miss is the-“indirect causes.” In this study it was seen that nearly 30 % women had indirect causes associated with them, and anemia was the most common indirect cause. This is in agreement with various other studies [9]. Recent study indicated that indirect causes were responsible for about a quarter of all maternal deaths [10]. In developed countries, co-morbidities in the form of pulmonary hypertension, malignancy, and systemic lupus erythematosus are more common [11], but in developing countries anemia and infections are the major co-morbidities.

Hematological system was involved in maximum near miss (36 %) followed by renal and hepatic, 18 % each, in this study. A study at Nepal also found hematological system to be most commonly involved [4]. Kallur et al. [12] at Hyderabad also showed it to be one of the most commonly involved systems.

In our study we have two maternal near miss for one maternal death. Though it is appreciable with so much overload, still we need to improve our statistics [13].

Conclusion

A sincere audit all over the country will allow the exposure of the quality of maternal health care. It will help tremendously in “Resource Allocation” in a particular place. Also, the required interventions may be variable. This underlines the need for ongoing training and drills, thus ultimately helping to reduce the maternal morbidity and mortality. All maternal near miss cases are living lessons who in spite of their misery show us our deficiencies.

Singh Abha

is the Director, Professor and Head of the Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology, Pt. Jawahar Lal Nehru Memorial Medical College, Raipur. She is also the founder and President of Chhattisgarh Association of Obstetricians & Gynecologists and President of Raipur Obstetrics and Gynaecology society. She is a peer-reviewer of Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology of India. She has been an executive member of Adolescent Committee, Fetal & Genetic Medicine & Endometriosis Committee. She has been awarded with Chief Minister's Trophy, Dr. S. K. Mukherji Award, Bharatiya Gaurav Award, and FOGSI GSK Best Paper Award in Preventive Oncology. She has more than 80 publications in national and international journals and has contributed to many chapters in various books.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

Dr. Abha Singh, Dr. Chandrashekhar Shrivastava, and Dr. Sonal Dube declared that they have no conflicts of interests.

Ethical Statement

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

As this is an observational study informed consent was not required.

Footnotes

Dr. Abha Singh is the Director professor and Head in Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at Pt. JNM Medical college Raipur; Dr. Chandrashekhar Shrivastava is the Associate Professor in Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at Pt. JNM Medical college Raipur; Dr. Sonal Dube is a third-year PG student of MD in Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at Pt. JNM Medical College Raipur.

References

- 1. Tajik P, Nedjat S, Afshar NE, et al. Inequality in maternal mortality in Iran: an ecologic study. Int J Prevent Med. 2012;3(2):116–21. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2. Trends in maternal mortality: 1990 to 2015 Estimate by WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, World bank group and the united nations population division. WHO Ref. no. WHO/RHR/15.23. 2015

- 3.Shreshta NS, Karki C, Saha R. Near miss maternal morbidity and maternal mortality at Kathmandu Medical College Teaching Hospital. Kathmandu Univ Med J. 2010;8(30):222–226. doi: 10.3126/kumj.v8i2.3563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ranatunga GA, Akbar JF, Samarathunga S, et al. Severe acute maternal morbidity in a tertiary care institution. Sri Lanka J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;34:135–143. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Knight HE, Self A, Kennedy SH. Why are women dying when they reach hospital on time? A systematic review of the ‘third delay’. PLoS one. 2013;8(5):e63846. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0063846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Win T, Vapattanawong P, Vong-ek P. Three delay related to maternal mortality in Myanmar: a case study from maternal death review, 2013. J Health Res. 2015;29(3):179–187. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pacagnella RC, Cecatti1 JG, Parpinelli MA, et al. Delays in receiving obstetric care and poor maternal outcomes: results from a national multicentre cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014;14:159. http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2393/14/159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Coverage Evaluation Survey 2009-Chhattisgarh fact sheet.ghdx.healthdata.org/record/india-coverage-evaluation-survey-2009-1010.

- 9.Sarma HKD, Sarma HK, Kalita AK. A prospective study of maternal near-miss and maternal mortality cases in FAAMCH, Barpeta; with special reference to its aetiology and management: first 4 months report. J Obstet Gynaecol Barpeta. 1(2).

- 10.Murthy BK, Murthy MB, Prabhu PM. Maternal mortality in a tertiary care hospital: a 10-year review. Int J Prev Med. 2013;4:105–109. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mhyre JM, Bateman BT, Leffert LR. Influence of patient comorbidities on the risk of near-miss maternal morbidity or mortality. The American Society of Anesthesiologists, Inc., Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Anesthesiology. 2011;115:963–972. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e318233042d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kallur SD, Vada BP, Reddy P, et al. Organ dysfunction and organ failure as predictors of outcomes of severe maternal morbidity in an Obstetric Intensive Care Unit. J Clin Diagn Res. 2014;8(4):OC06–OC08. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2014/8068.4213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nacharaju M, Sudhir P, Kaul R, et al. Maternal near miss: an experience in rural medical college. J Evol Med Dent Sci. 2014;3(56):12761–12767. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Roopa PS, Verma S, Rai L, et al. “Near miss’’ obstetric events and maternal deaths in a Tertiary Care Hospital: an audit. Hindawi Publishing Corporation. J Pregnancy. 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Das I, Datta M, Samanta S, et al. A cross-sectional study on post-partum severe acute maternal morbidity and maternal deaths in a Tertiary Level Teaching Hospital of Eastern India. Int J Women’s Health Reprod Sci. 2014;2(3). ISSN 2330-4456.

- 16.Kalra P, Kachhwaha CP. Obstetric near miss morbidity and maternal mortality in a Tertiary Care Centre in Western Rajasthan. Indian J Publ Health. 2014;58(3). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Bakshi RK, Roy D, Aggarwal P, et al. Demographic determinants of maternal “near-miss” cases in rural Uttarakhand. Natl J Community Med. 2014;5(3).