Abstract

Objective

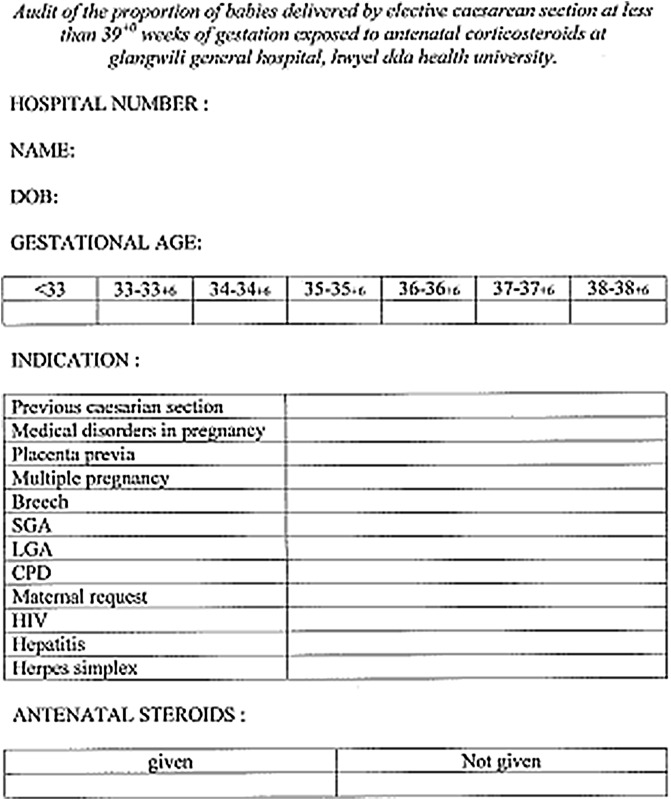

Aim of this audit is to analyse indication and proportion of babies delivered by elective caesarean section at less than 39+0 weeks of gestation exposed to antenatal corticosteroids performed in a Premier Hospital, Hywel Dda Health University. The second aim was to learn how an audit can be done and used for improving clinical practice.

Methods

Present study involved all patients who underwent elective caesarean delivery before 39 weeks completed period of gestation in August and September 2014. Data collected from medical record tracking using ICD-9 codes and analysed by clinical audit department.

Exclusion

Patients who underwent elective caesarean section after 39 weeks completed period of gestation.

Discussion

The audit showed 66.6 % of patients were given antenatal corticosteroids. The observation was discussed in consultant meetings, labour forum, and was send as e-mail to every one working in Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. The goal was 100 %. Reaudit is to be performed in year time to know the effect of change in practice. All successful audits are structured programmes with realistic aims and objectives, leadership and attitude of senior management, nondirective, hands-on approach, support of staff, strategy groups and regular discussions, emphasis on team working and support, environment conducive to conducting audit.

Keywords: Audit, Antenatal steroids, Data collection, Data analysis

Introduction

The study was based on the green top guideline on antenatal corticosteroids to reduce neonatal morbidity and mortality. Guideline recommends that antenatal corticosteroids should be given to all women for whom an elective caesarean section is planned prior to 38+6 weeks of gestation.

The study was an audit of the proportion of babies delivered by elective caesarean section at less than 39+0 weeks of gestation exposed to antenatal corticosteroids at Glangwili General Hospital, Hywel Dda Health University, Wales, UK.

The incidence of caesarean section is 20 % in the Obstetrics Unit of Glangwili General Hospital.

There is a widespread public and professional concern about the increasing proportion of births by caesarean section [1]. Increasing rates of primary caesarean section have led to an increased proportion of the obstetric population who have a history of prior caesarean delivery. Pregnant women with a previous section may be offered either planned VBAC or ERCS. The proportion of women who decline VBAC is, in turn, a significant determinant of overall rates of caesarean birth [2–5]. New evidence is emerging to indicate that VBAC may not be as safe as originally thought [6, 7]. These factors, together with medico-legal fears, have led to a recent decline in clinicians offering and women accepting planned VBAC in the UK and North America [2–5].

Studies have shown that delivery by elective caesarean section at less than 39+0 weeks of gestation can lead to respiratory morbidity in neonates, requiring admission to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) [8–11]. A recent retrospective cohort study showed that, compared with elective caesarean section births at 39+0 weeks of gestation, births at 37+0 weeks of gestation and at 38+0 weeks of gestation were associated with an increased risk of a composite outcome of neonatal death and/or respiratory complications, treated hypoglycaemia, newborn sepsis and admission to the NICU (adjusted OR for births at 37 weeks of gestation 2.1, 95 % CI 1.7–2.5; adjusted OR for births at 38 weeks of gestation 1.5; 95 % CI 1.3–1.7; P for trend <0.001) [11]. The rates of adverse respiratory outcomes, mechanical ventilation, newborn sepsis, hypoglycaemia, admission to the NICU and hospitalization for 5 days or more were increased by a factor of 1.8–4.2 for births at 37 weeks of gestation and 1.3–2.1 for births at 38 weeks of gestation.

A further study in Denmark [10] showed the risk of respiratory morbidity for infants delivered by elective caesarean section decreased by gestation compared with vaginal birth (37 weeks of gestation OR 3.9, 95 % CI 2.4–6.5; 38 weeks of gestation OR 3.0, 95 % CI 2.1–4.3; and 39 weeks of gestation OR 1.9, 95 % CI 1.2–3.0).

Treatment with antenatal corticosteroids prior to delivery by elective caesarean section has been shown to reduce the need for admission to the NICU up to 38+6 weeks of gestation compared with controls. A randomized controlled trial showed that the relative risk of admission with RDS in babies treated with antenatal corticosteroids prior to elective caesarean section at term was 0.46 (95 % CI 0.23–0.93, P = 0.02). The relative risk of transient tachypnoea of the newborn was 0.040 in the control group and 0.021 in the treatment group (RR 0.54, 95 % CI 0.26–1.12). The relative risk of RDS was 0.011 in the control group and 0.002 in the treatment group (RR 0.21, 95 % CI 0.03–1.32). The predicted probability of admission to NICU at 37 weeks of gestation was 11.4 % in the control group and 5.2 % in the treatment group, at 38 weeks, it was 6.2 and 2.8 %, respectively, and at 39 weeks, it was 1.5 and 0.6 %, respectively [12]. There is an absence of evidence available for the safety of antenatal corticosteroids in babies born after 36+0 weeks of gestation. Elective lower segment caesarean section should not normally be performed until 39+0 weeks of gestation, rather than the administration of antenatal corticosteroids.

Discussion

The audit showed 66.6 % of patients were given antenatal corticosteroids. The observation was discussed in consultant meetings, labour forum, and was send as e-mail to every one working in Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. The goal was 100 %. Reaudit is to be performed in year time to know the effect of change in practice.

Audit

Background

Clinical governance provides a framework for accountability and quality improvement. While research is concerned with discovering the right thing to do, audit is concerned with ensuring that the right thing is done [13]. Clinical audit is a quality improvement process that seeks to improve patient care and outcomes through systematic review of care against explicit criteria and the implementation of change. Aspects of the structure, processes and outcomes of care are selected and systematically evaluated against explicit criteria. Where indicated, changes are implemented at an individual, team or service level, and further monitoring is used to confirm improvement in healthcare delivery.

As good medical practice, individual doctors are required to undertake clinical audit. Obstetricians and gynaecologists therefore need to understand the principles of clinical audit.

The Audit Cycle

Audit can be considered to have five principal steps, commonly referred to as the audit cycle (Fig. 1):

selection of a topic

identification of an appropriate standard

data collection to assess performance against the pre-specified standard

implementation of changes to improve care if necessary

data collection for a second, or subsequent, time to determine whether care has improved.

Fig. 1.

The audit cycle

Audit projects require a multidisciplinary approach with the involvement of stakeholders (including consumers or users of the service provided) and the local audit department at the planning stage. Good planning and resources are also necessary to ensure its success.

Selection of a Topic

It is essential to establish clear aims and objectives at this stage so that the audit is focused and addresses specific issues within the selected topic. In selecting a topic for audit, priority should be given to common health concerns, areas associated with high rates of mortality, morbidity or disability, and those where good research evidence is available to inform practice or aspects of care that use considerable resources by involving those who will be implementing change.

Identification of an Appropriate Standard

Review Criteria

These are defined as ‘systematically developed statements that can be used to assess specific healthcare decisions, services and outcomes’. The criterion is the reference point against which current practice is measured. High-quality evidence-based guidelines can be used as the starting point for developing criteria. Where this is not possible, criteria should be agreed by a multidisciplinary group including those involved in providing care and those who use the service. Where criteria are based on the views of professionals or other groups, formal consensus methods are preferable. Review criteria should be explicit rather than implicit and need to [14] lead to valid judgements about the quality of care, and therefore should be based on research evidence about the importance of those aspects of care that are important either to patients or in terms of clinical outcome be measurable.

Standard and Target Level of Performance

This is defined as ‘the percentage of events that should comply with the criterion’.

Information about the levels of performance that can be achieved may be helpful when making plans for improvement. Target levels of performance should be examined periodically.

Benchmarking

This is the ‘process of defining a level of care set as a goal to be attained’. Benchmarking techniques could help participants in audit to avoid setting unnecessarily low or unrealistically high target levels of performance. Reference to the levels achieved in audits undertaken by other professionals is useful. National audits may provide data for benchmarking [15].

Data collection to assess performance against the pre-specified standard data collection in criterion-based audit is generally undertaken to determine the proportion of cases where care is in accordance with the criteria.

Consideration needs to be given to which data items are needed in order to answer the audit question. Definitions need to be clear so that there is no confusion about what is being collected.

Data collectors should always be aware of their responsibilities to the personnel Data Protection Bill 2013.

How to Collect the Data

Sources of data include:

routinely collected data if available. This enables repeated data collections with the minimum of extra effort

clinical records

data collection through direct observation or from questionnaire surveys of staff or patients.

Routinely collected data can be used if all the data items required are available.

Where the data source is clinical records, training of data abstractors and use of a standard proforma can improve accuracy and reliability of data collection. The use of multiple sources of data may also be helpful. Questionnaire surveys of staff or patients are often used for data collection.

Who Will Collect the Data?

Thought needs to be given to who will collect the data, as well as the time and resources that will be involved. In small audit projects, it may be feasible for the principal investigators to go through clinical notes for data abstraction. Where available, audit support staff should be involved.

Data Management

Data that are collected on paper forms are usually entered on to electronic databases or spreadsheets such as Microsoft Access®, Epi Info® or Microsoft Excel® for cleaning and analysis [16].

Data Analysis

Simple statistics are often all that are required. Statistical methods are used to summarize data for presentation in the form of summary statistics (means, medians or percentages) and graphs [17]. Statistical tests are used to find out the likelihood that the data obtained have arisen by chance and how likely it is that a real difference exists between two groups. Data items that have categorical responses can be expressed as percentages. These summary statistics (percentages and means) are useful for describing the process, outcome or service provision that was measured.

Implementation of Changes to Improve Care if Necessary

Data analysis and interpretation will lead to the identification of clinical areas that should be addressed. There are many methods by which this can be done. The feedback of audit findings at regular audit meetings will stimulate discussions, and solutions may be agreed.

The significance of teamwork, culture and resistance to change has led several authors to propose frameworks for planning implementation. These usually include analysis of the barriers to change and use of theories of individual, team or organizational behaviour to select strategies to address the barriers.

Organization of Audit

The features associated with successful audit are structured programmes with realistic aims and objectives, leadership and attitude of senior management, nondirective, hands-on approach, support of staff, strategy groups and regular discussions, emphasis on team working and support, environment conducive to conducting audit.

Dr. Georgy Joy Eralil

Currently working as Associate Professor in Sreenarayana Institute of Medical Sciences, had training in obstetrics and gynaecology as Medical Trainee International (RCOG London) and attained membership. He got training in Medical Genetics and Genetic Counseling (SGPGI Lucknow), molecular diagnostic techniques of STD (NIRRH Mumbai), Gynaecological Endoscopy (PGIMER Chandigarh), Medical Education Technologies (Medical Council India), Gynae Ultrasound (2D, 3D, 4D), Colposcopy and WHO training for managing diabetes mellitus. Areas of interest are infertility and high-risk obstetrics.

Appendix

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The author declares that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by author.

Footnotes

Dr. Georgy Joy Eralil, MBBS, MS, DGO, MRCOG, is the Associate Professor in Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology at Sreenarayana Institute of Medical Sciences.

References

- 1.Parliamentary Office of Science and Technology Caesarean sections. Postnote. 2002;184:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Menacker F. Trends in cesarean rates for first births and repeat cesarean rates for low-risk women: United States, 1990–2003. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2005;54:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu S, Rusen ID, Joseph KS, et al. Recent trends in caesarean delivery rates and indications for caesarean delivery in Canada. J Obstet Gynecol Can. 2004;26:735–742. doi: 10.1016/s1701-2163(16)30645-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Black C, Kaye JA, Jick H. Cesarean delivery in the United Kingdom: time trends in the general practice research database. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106:151–155. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000160429.22836.c0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yeh J, Wactawski-Wende J, Shelton JA, et al. Temporal trends in the rates of trial of labor in low-risk pregnancies and their impact on the rates and success of vaginal birth after cesarean delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194:144. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.06.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Landon MB, Hauth JC, Leveno KJ, et al. Maternal and perinatal outcomes associated with a trial of labor after prior cesarean delivery. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2581–2589. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith GC, Pell JP, Cameron AD, et al. Risk of perinatal death associated with labor after previous cesarean delivery in uncomplicated term pregnancies. JAMA. 2002;287:2684–2690. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.20.2684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tita AT, Landon MB, Spong CY, et al. Eunice Kennedy Shriver NICHD maternal-fetal medicine units network. Timing of elective repeat cesarean delivery at term and neonatal outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:111–120. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0803267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yee W, Amin H, Wood S. Elective cesarean delivery, neonatal intensive care unit admission, and neonatal respiratory distress. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111:823–828. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31816736e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hansen AK, Wisborg K, Uldbjerg N, et al. Risk of respiratory morbidity in term infants delivered by elective caesarean section: Cohort study. BMJ. 2008;336:85–87. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39405.539282.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morrison JJ, Rennie JM, Milton PJ. Neonatal respiratory morbidity and mode of delivery at term: influence of timing of elective caesarean section. Br J Obstet Gynecol. 1995;102:101–106. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1995.tb09060.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stutchfield P, Whitaker R. Russell I; Antenatal Steroids for Term Elective Caesarean Section (ASTECS) Research Team. Antenatal betamethasone and incidence of neonatal respiratory distress after elective caesarean section: pragmatic randomised trial. BMJ. 2005;331:662. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38547.416493.06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smith R. Audit and research. BMJ. 1992;305:905–906. doi: 10.1136/bmj.305.6859.905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.NHS, National Institute for Clinical Excellence, Commission for Health Improvement, Royal College of Nursing, University of Leicester . Principles for best practice in clinical audit. Oxford: Radcliffe Medical Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists Clinical effectiveness support unit team matters. Br J Cancer. 1994;70:363–370. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1994.307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. McKenzie-McHarg K, Ayres S. Data management. In: O’Brien PMS, Broughton Pipkin F, editors. Introduction to research methodology for specialists and trainees. London: RCOG Press; 1999. p. 140–6.

- 17.Brocklehurst P, Gates S. Statistics. In: O’Brien PMS, Broughton Pipkin F, editors. Introduction to research methodology for specialists and trainees. London: RCOG Press; 1999. p. 147–60.