Abstract

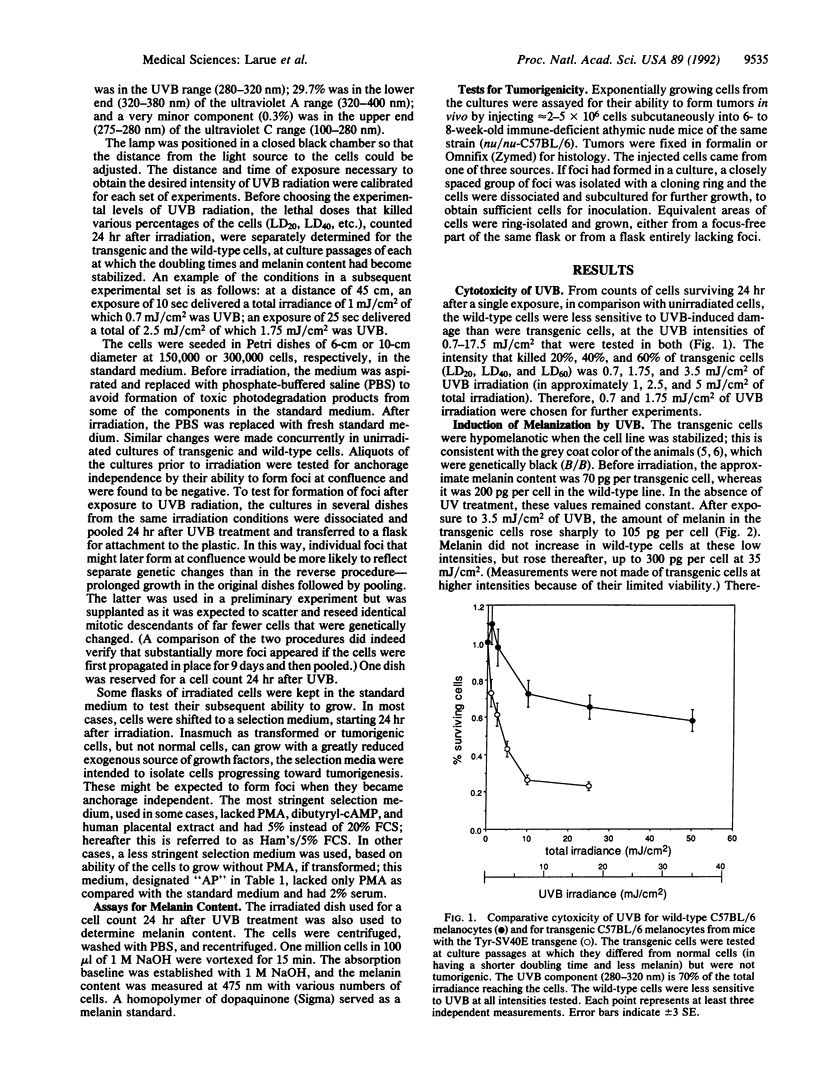

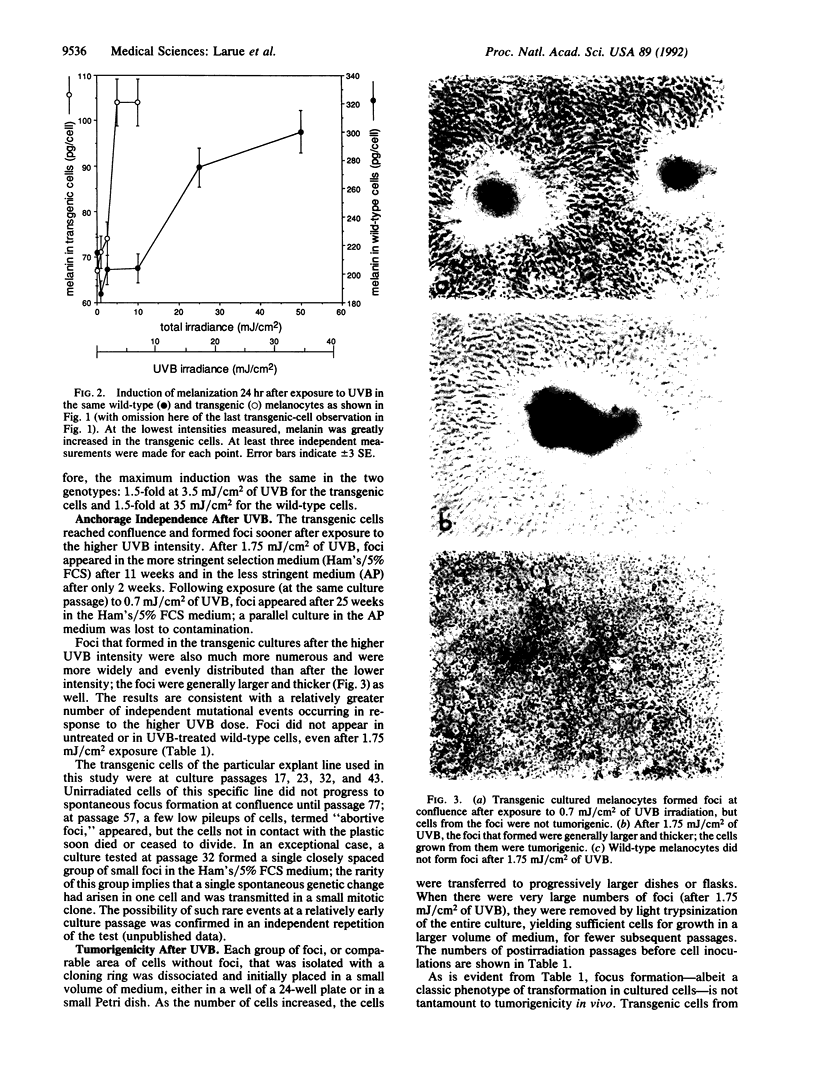

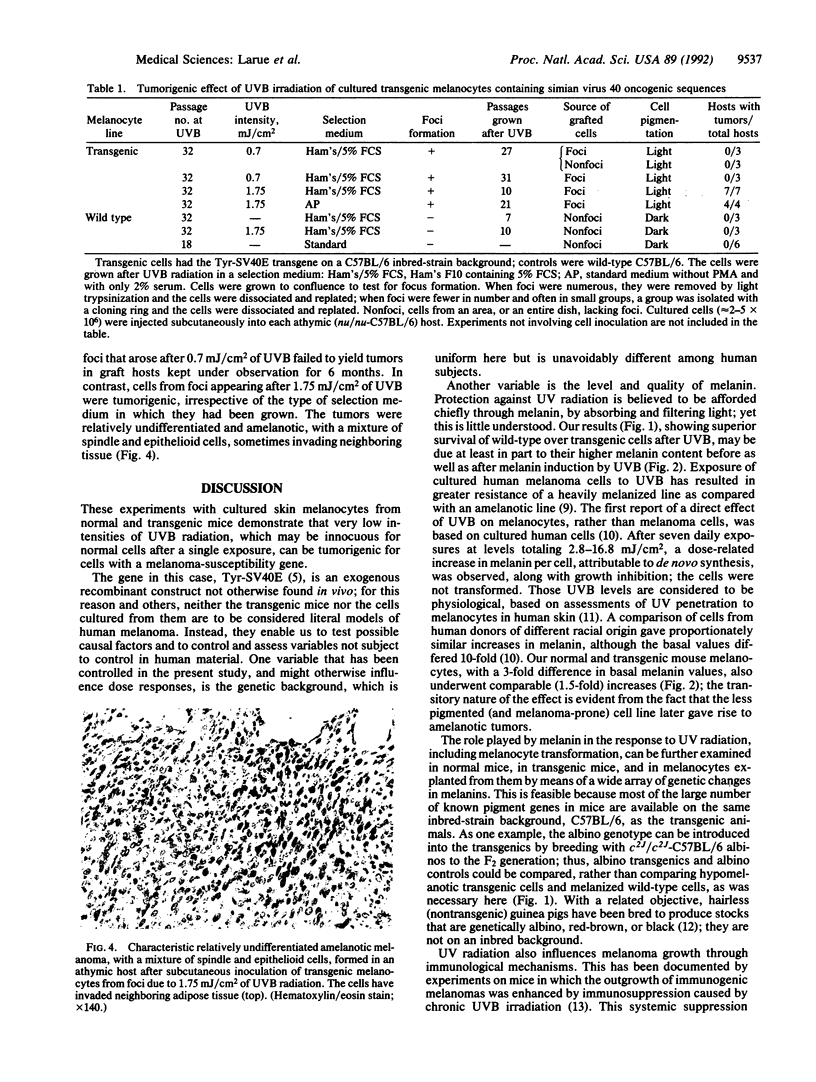

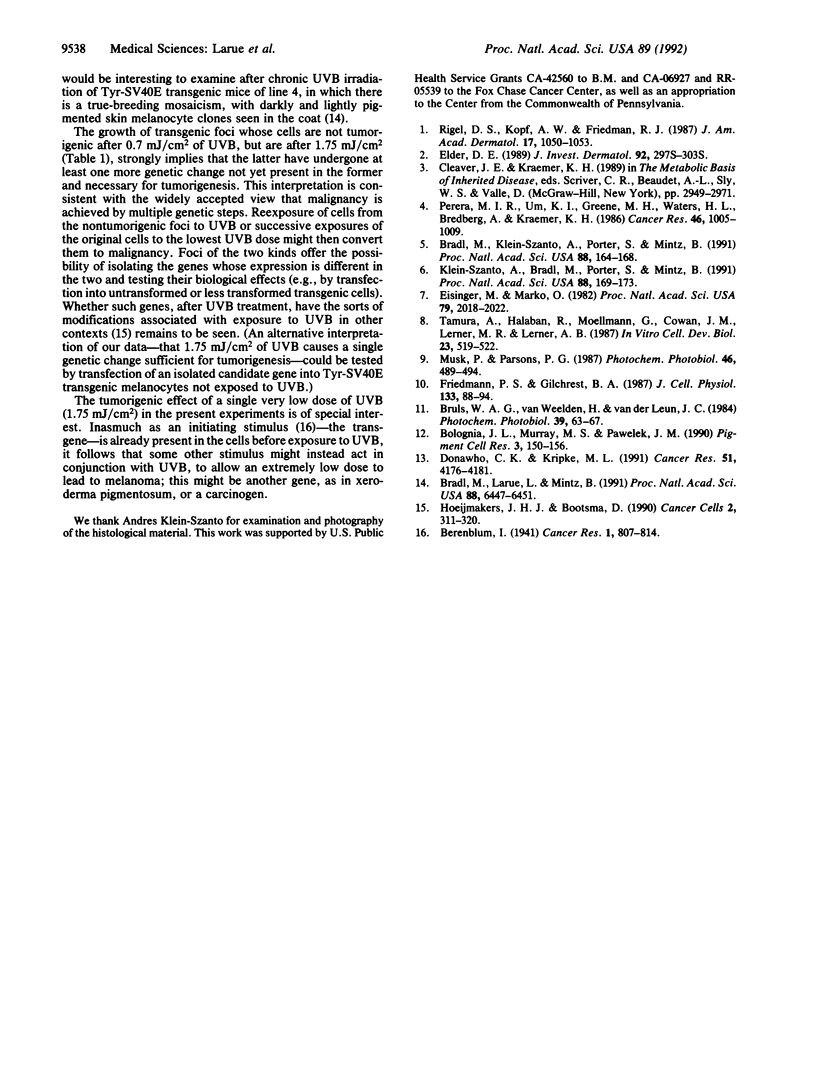

Tyr-SV40E transgenic mice are susceptible to melanoma due to simian virus 40 oncogenic sequences specifically expressed in pigment cells. Skin melanomas form relatively late. Therefore, melanocyte cell lines have been established from very young transgenic animals, when they showed no skin lesions, so that the spontaneous and gradual progress of the cells toward tumorigenesis could be characterized under culture conditions in which wild-type cells of the same inbred strain remain untransformed. Melanocytes of an in vitro transgenic line were irradiated with very low intensities of ultraviolet B (UVB) (280- to 320-nm wavelength) light at culture passages when the cells had not achieved anchorage independence. After a single exposure to 0.7 mJ/cm2 of UVB radiation, the cells became anchorage independent and formed foci at confluence; however, cells propagated from the foci were not tumorigenic. After one exposure to 1.75 mJ/cm2, more numerous and larger foci resulted, and the cells grown from them yielded malignant melanomas in graft hosts. Wild-type melanocytes were not transformed at these UVB doses. At least two genetic changes contributing to malignant conversion--in addition to the initiating effect of the transgene--are likely to have occurred, one change leading to anchorage independence and another to further progress toward malignancy. Cells at these stages provide an opportunity to isolate the relevant genes and identify any molecular defects attributable to UVB. Tumorigenesis after a very low UVB dose in cells where an initiating stimulus is already present suggests that some other stimulus, such as a gene or a carcinogen, might lead to melanoma in conjunction with exposure to relatively little UVB.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Bolognia J. L., Murray M. S., Pawelek J. M. Hairless pigmented guinea pigs: a new model for the study of mammalian pigmentation. Pigment Cell Res. 1990 Sep;3(3):150–156. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0749.1990.tb00280.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradl M., Klein-Szanto A., Porter S., Mintz B. Malignant melanoma in transgenic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991 Jan 1;88(1):164–168. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.1.164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradl M., Larue L., Mintz B. Clonal coat color variation due to a transforming gene expressed in melanocytes of transgenic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991 Aug 1;88(15):6447–6451. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.15.6447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruls W. A., van Weelden H., van der Leun J. C. Transmission of UV-radiation through human epidermal layers as a factor influencing the minimal erythema dose. Photochem Photobiol. 1984 Jan;39(1):63–67. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1984.tb03405.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donawho C. K., Kripke M. L. Evidence that the local effect of ultraviolet radiation on the growth of murine melanomas is immunologically mediated. Cancer Res. 1991 Aug 15;51(16):4176–4181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisinger M., Marko O. Selective proliferation of normal human melanocytes in vitro in the presence of phorbol ester and cholera toxin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1982 Mar;79(6):2018–2022. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.6.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elder D. E. Human melanocytic neoplasms and their etiologic relationship with sunlight. J Invest Dermatol. 1989 May;92(5 Suppl):297S–303S. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep13076732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedmann P. S., Gilchrest B. A. Ultraviolet radiation directly induces pigment production by cultured human melanocytes. J Cell Physiol. 1987 Oct;133(1):88–94. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041330111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoeijmakers J. H., Bootsma D. Molecular genetics of eukaryotic DNA excision repair. Cancer Cells. 1990 Oct;2(10):311–320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein-Szanto A., Bradl M., Porter S., Mintz B. Melanosis and associated tumors in transgenic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991 Jan 1;88(1):169–173. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.1.169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musk P., Parsons P. G. Resistance of pigmented human cells to killing by sunlight and oxygen radicals. Photochem Photobiol. 1987 Oct;46(4):489–494. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1987.tb04800.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perera M. I., Um K. I., Greene M. H., Waters H. L., Bredberg A., Kraemer K. H. Hereditary dysplastic nevus syndrome: lymphoid cell ultraviolet hypermutability in association with increased melanoma susceptibility. Cancer Res. 1986 Feb;46(2):1005–1009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigel D. S., Kopf A. W., Friedman R. J. The rate of malignant melanoma in the United States: are we making an impact? J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987 Dec;17(6):1050–1053. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(87)80487-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura A., Halaban R., Moellmann G., Cowan J. M., Lerner M. R., Lerner A. B. Normal murine melanocytes in culture. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol. 1987 Jul;23(7):519–522. doi: 10.1007/BF02628423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]