Abstract

Wellens’ syndrome is characterized by T-wave changes in electrocardiogram (EKG) during pain-free period in a patient with intermittent angina chest pain. It carries significant diagnostic and prognostic value because this syndrome represents a pre-infarction stage of coronary artery disease involving proximal left anterior descending (LAD) artery, which can subsequently lead to extensive anterior myocardial infarctions (MIs) and even death without coronary angioplasty. Therefore, it is crucial for every physician to recognize EKG features of Wellens’ syndrome in order to take appropriate immediate intervention to reduce mortality and morbidity for MI. Here, we report a case of an overweight man with 35 pack-year of smoking history who presented to Easton Hospital with intermittent pressing chest pain of 5/6 times within 10 day-period and was found to have type A Wellens’ sign, which was biphasic T-waves in precordial leads V2 and V3 during pain-free period with no cardiac enzymes elevation. He was given therapeutic lovenox and subsequently underwent coronary angioplasty and had 95–99% occlusion in proximal LAD artery. The unique feature of our case was that Wellens’ type B EKG changes were seen after reduction of stenosis with LAD artery stent, which was likely explained by the reperfusion of the ischemic myocardium. Therefore, it is important for physicians to recognize EKG features of Wellens’ syndrome in order to take appropriate therapy to reducing mortality and morbidity form impending MI.

Keywords: T-inversion, Wellens' syndrome, myocardial infarction, left anterior descending artery obstruction, electrocardiographic changes, revascularization

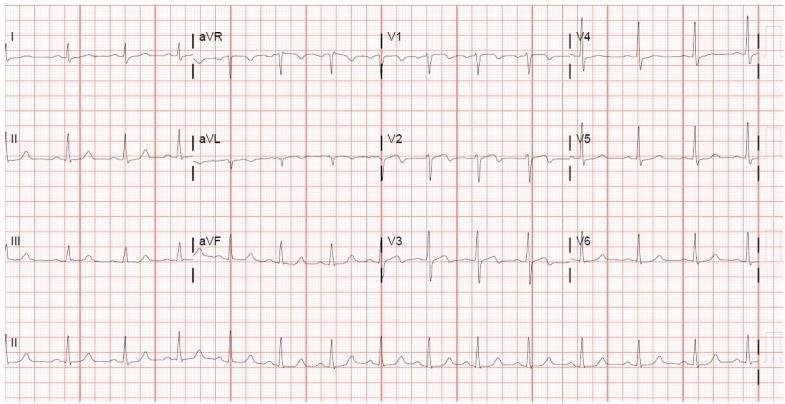

A52-year-old Caucasian male, with a past medical history significant only for a 35 pack-year current smoking history, presented with severe intermittent sub-sternal chest pain for 2 weeks’ duration. The chest pain occurred with exertion and relieved with rest. Upon arrival to the emergency department (ED), he had continued pain and vital signs were within normal limits. Physical examination was unremarkable. Electrocardiogram (EKG) was performed and demonstrated sinus tachycardia with biphasic T-waves in V2 and V3 without pathologic Q-waves (Fig. 1), typical of the Wellens’ sign.

Fig. 1.

EKG before stent placement, showing biphasic T-waves in leads V2 and V3.

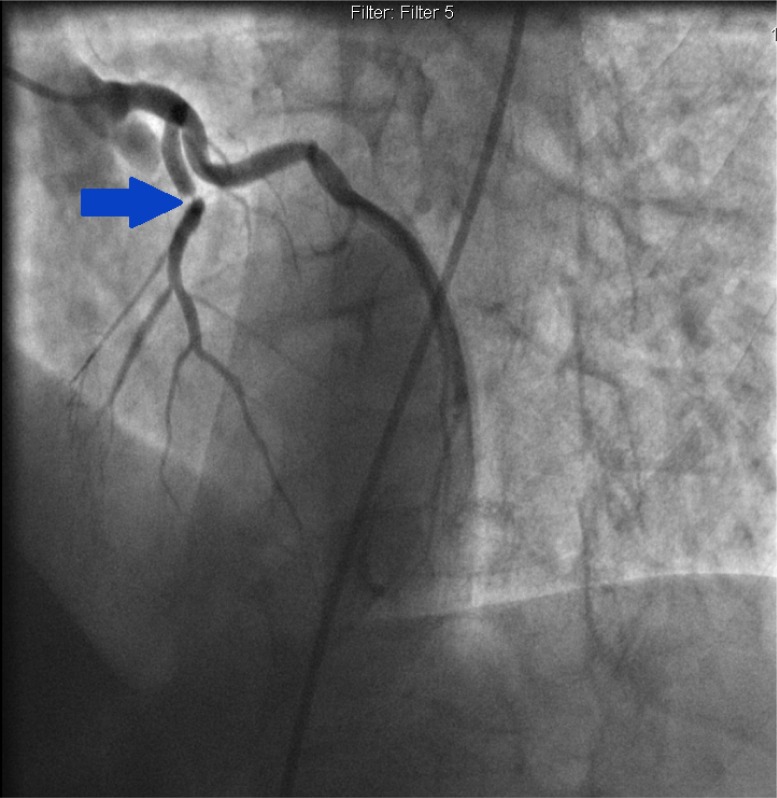

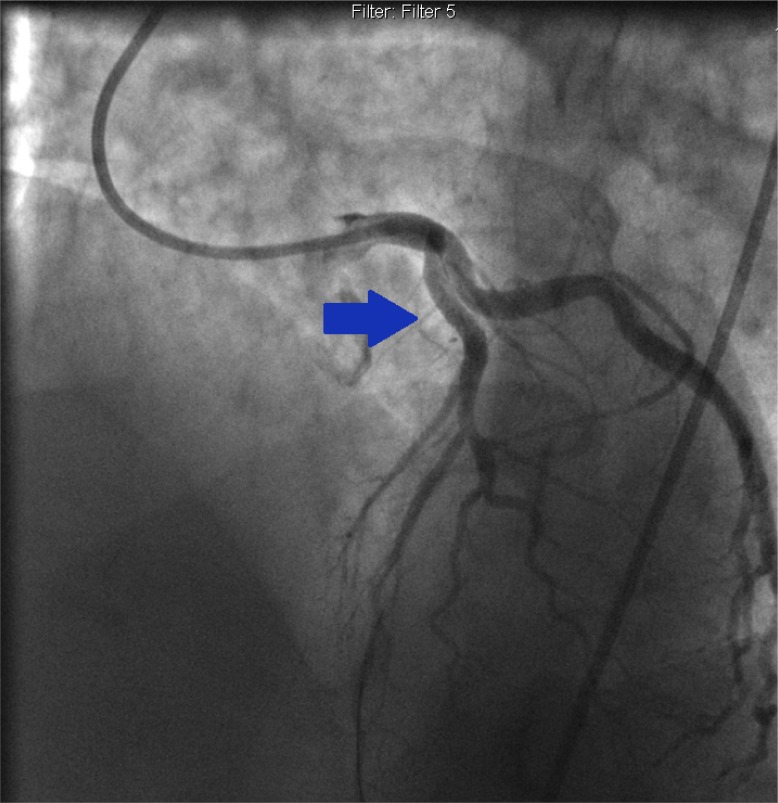

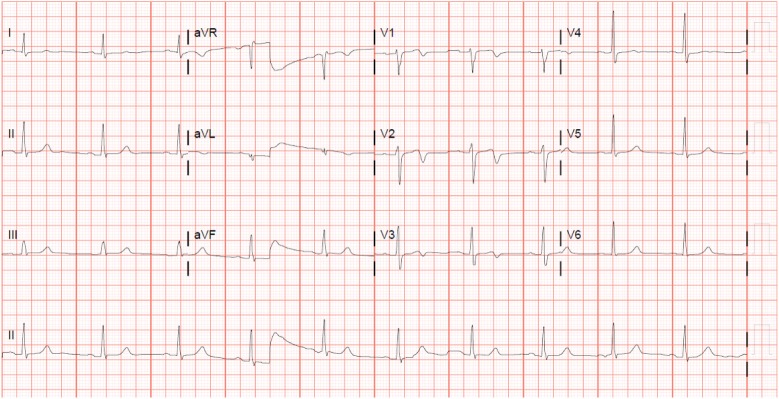

He was urgently taken for cardiac catheterization, which revealed 95–99% stenosis of proximal left anterior descending (LAD) artery (Fig. 2), and a drug eluting stent was successfully placed (Fig. 3), without any complications. Left ventricular angiogram revealed mild hypokinesis of the anterolateral wall with a visually estimated ejection fraction (EF) of 45–50%. A repeat EKG immediately after percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) revealed the resolution of type A Wellens’ sign; however, he had persistent deep T-wave inversions in leads V1–V3 (Fig. 4) representing type B Wellens’ sign.

Fig. 2.

Coronary angiogram revealing 99% stenosis of proximal left anterior descending artery pre-intervention.

Fig. 3.

Coronary angiogram showing lesion was reduced to zero percent after drug eluting stent placement.

Fig. 4.

EKG 1 day after stent placement, showing deep T-wave inversion in leads V1–V3.

Dual antiplatelet therapy with aspirin and prasugrel was maintained in addition to metoprolol and daily atorvastatin. In addition, he was counselled extensively about nicotine cessation. He currently follows up with the cardiac rehabilitation program and continues to do well.

Background

Wellens’ sign, or the LAD coronary artery T-wave inversion pattern (1), is seen in a subset of patients who often present with chest pain and are found to have specific precordial T-wave changes on EKG. Its incidence is estimated to be about 10–15% of acute coronary syndrome (ACS). With unstable angina patients, however (excluding bundle branch blocks and old anterior myocardial infarctions [MIs]) in the United States, this syndrome is often under-recognized. The natural course of this pattern is unfavorable, with a high incidence of recurrent symptoms. It can rapidly progress to an anterior myocardial wall infarction if left untreated, causing catastrophic outcomes due to lesions in the proximal LAD artery. It is vital that physicians are aware of this important prognostic sign and proceed with aggressive management. This can include cardiac catheterization with percutaneous intervention and/or surgical revascularization.

Discussion

Wellens’ sign was first reported in 1982 by De Zwaan and Wellens, when they noticed the characteristic T-wave changes in a subset of patients with stenosis in the proximal LAD artery (2). They observed that this sign was found in about 18% of the 145 patients in their original study published in 1982 (3). They subsequently published a much larger analysis in 1989, where approximately 87% of the patient population with isolated precordial T-wave inversions in cardiac care units have LAD artery stenosis (of greater than 50% with a mean value of 85% stenosis) reported during angiography.

Criteria for diagnosing Wellens’ syndrome include all of the following:

Type A – Biphasic T-waves in V2 and V3

Type B – Deep and symmetrical T-wave inversions in V2 and V3

EKG without Q-waves and no significant ST segment elevation, with normal precordial R-wave progression

History of anginal chest pain

Normal or minimally elevated cardiac enzyme levels (1, 3, 4).

Based on these criteria, it is estimated that the positive predictive value of Wellens’ sign is approximately 86%. Cardiac serum markers were often normal or minimally elevated. In a prospective study of patients with Wellens’ syndrome, only 21 of 180 patients (12%) with EKG changes had elevated cardiac enzymes. These elevations were always less than twice the upper limit of normal. Therefore, the EKG may be the only indication of an impending extensive anterior wall myocardial infarction in an otherwise asymptomatic patient.

It is important to remember that the majority of the time, these characteristic EKG findings can be present only during pain-free intervals of patients presenting with intermittent anginal chest pain with critical LAD artery stenosis. This can be easily overlooked. (2, 4)

The T-wave changes are usually present in leads V2 and V3. However, in certain cases, leads V1 and V4 can also be involved. In the study by De Zwaan and Wellens, they noted that approximately two-thirds of the patients also had these changes in lead V1 and three-fourths of them in lead V4.

Mechanism

The mechanism of Wellens’ syndrome remains unclear. It is considered a pre-infarction stage of coronary artery disease as the T-wave changes in the syndrome usually occur during a pain-free interval. However, it is postulated that the changes in the EKG account for reperfusion of the ischemic myocardium due to alleviation of spasm of proximal LAD artery (5).

Risk factors

The risk factors for Wellens’ syndrome include the traditional risk factors for coronary artery disease such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, obesity, smoking, and family history of premature coronary disease (6). It can be seen in any age group, with the youngest case reported in a 22-year-old man. (7)

Wellens’ syndrome is characterized by a state of impending myocardial infarction even with optimal medical treatment. Acute myocardial infarction, left ventricular dysfunction, and death can ensue if appropriate and prompt interventional catheterization is not performed in a timely fashion (8).

Treatment

All patients with this syndrome should receive the standard care for ACS, including aspirin, nitroglycerin for pain, and beta-blockers if appropriate. Serum EKGs and serum cardiac markers need to be followed. Given these patients’ acuity, inpatient hospital admission is warranted. It is important to remember that these patients may manifest the signs during pain-free intervals, so repeating serial EKGs is crucial to confirming the diagnosis

The primary issue here is recognizing this sign in a timely fashion as patients with Wellens’ syndrome should undergo coronary intervention. Performing a stress test with provocative agents is absolutely contraindicated, as it can increase myocardial demand with highly stenotic lesions and induce myocardial infarction and subsequent sudden death (6, 8).

Prognosis

Most patients, when identified early and taken for cardiac catheterization, do well after appropriate intervention. T-wave changes should resolve after appropriate revascularization. In our patient, however, type A Wellens’ sign was appreciated before cardiac intervention, and type B persisted after appropriate percutaneous intervention. Weaver et al. published that persistent ST elevation after PCI is related to microvascular occlusion and ongoing myocardial damage (9). Sakata et al. studied persistent negative T-wave after transmural infarct associated with Q-waves. They demonstrated that patients with persistent T-wave inversion after 12 months have reduced left ventricular function (10). However, we could not find any prognostic significance of persistent T-wave inversion after non-transmural infarction.

Conclusion

Wellens’ syndrome is characterized by T-wave changes in EKG, most often seen during pain-free period in a patient with intermittent angina chest pain. It carries significant diagnostic and prognostic value because this syndrome represents a pre-infarction stage of coronary artery disease involving proximal LAD artery, which can subsequently lead to extensive anterior MI and even death without coronary artery revascularization. It is important to remember that stress testing is absolutely contraindicated in these patients. Although these patients may initially respond well to medical management, they ultimately fare poorly with a conservative therapy and require revascularization strategies. Therefore, it is crucial for clinicians to recognize EKG features of Wellens’ syndrome in order to take appropriate therapy to reducing mortality and morbidity form impending MI.

Conflict of interest and funding

The authors have not received any funding or benefits from industry or elsewhere to conduct this study.

References

- 1.Rhinehardt J, Brady WJ, Perron AD, Mattu A. Electrocardiographic manifestations of Wellens’ syndrome. Am J Emerg Med. 2002;20(7):638–43. doi: 10.1053/ajem.2002.34800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.de Zwaan C, Bär FW, Janssen JH, Cheriex EC, Dassen WR, Brugada P, et al. Angiographic and clinical characteristics of patients with unstable angina showing an ECG pattern indicating critical narrowing of the proximal LAD coronary artery. Am Heart J. 1989;117(3):657–65. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(89)90742-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Zwaan C, Bär FW, Wellens HJ. Characteristic electrocardiographic pattern indicating a critical stenosis high in left anterior descending coronary artery in patients admitted because of impending myocardial infarction. Am Heart J. 1982;103(4 Pt 2):730–6. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(82)90480-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Balasubramanian K, Balasubramanian R, Subramanian A. A dangerous twist of the ‘T’ wave: A case of Wellens’ Syndrome. Australas Med J. 2013;6(3):122–5. doi: 10.4066/AMJ.2013.1636. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.4066/AMJ.2013.1636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sheng FQ, He MR, Zhang ML, Shen GY. Wellens’ syndrome caused by spasm of the proximal left anterior descending coronary artery. J Electrocardiol. 2015;48(3):423–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2015.03.009. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2015.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khan B, Alexander J, Rathod KS, Farooqi F. Wellens’ syndrome in a 24-year-old woman. BMJ Case Rep 2013. 2013:bcr2013009323. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2013-009323. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2013-009323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang JY, Chen H, Su X, Zhang ZP. Wellens’ syndrome in a 22-year-old man. Am J Emerg Med. 2016;34:937.e3–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2015.09.043. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2015.09.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hollar L, Hartness O, Doering T. Recognizing Wellens’ syndrome, a warning sign of critical proximal LAD artery stenosis and impending anterior myocardial infarction. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect. 2015;5(5):29384. doi: 10.3402/jchimp.v5.29384. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.3402/jchimp.v5.29384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weaver JC, Ramsay DD, Rees D, Binnekamp MF, Prasan AM, McCrohon JA. Dynamic changes in ST segment resolution after myocardial infarction and the association with microvascular injury on cardiac magnetic resonance imaging. Heart Lung Circ. 2011;20(2):111–8. doi: 10.1016/j.hlc.2010.09.006. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.hlc.2010.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sakata K, Yoshino H, Houshaku H, Koide Y, Yotsukura M, Ishikawa K. Myocardial damage and left ventricular dysfunction in patients with and without persistent negative T waves after Q-wave anterior myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 2001;87(5):510–15. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(00)01422-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]