Abstract

Graves’ disease is the most common cause of hyperthyroidism. If left untreated, patients may have multiple systemic complications such as cardiac, reproductive, and skeletal disease. Thionamides, such as methimazole and propylthiouracil, and I131 iodine ablation are the most commonly prescribed treatment for Graves’ disease. Total thyroidectomy is often overlooked for treatment and is usually only offered if the other options have failed. In our case, we discuss a patient who was admitted to our medical center with symptomatic hyperthyroidism secondary to long-standing Graves’ disease. She had a history of non-compliance with medications and medical clinic follow-up. The risks and benefits of total thyroidectomy were explained and she consented to surgery. A few months after the procedure, she was biochemically and clinically euthyroid on levothyroxine. She had no further emergency room visits or admissions for uncontrolled thyroid disease. Here we review the advantages and disadvantages of the more typically prescribed treatments, thionamides and I131iodine ablation. We also review the importance of shared decision making and the benefits of total thyroidectomy for the management of Graves' disease. Given the improvement in surgical techniques over the past decade and a significant reduction of complications, we suggest total thyroidectomy be recommended more often for patients with Graves’ disease.

Keywords: hyperthyroidism, thionamides, methimazole, propylthiuracil, iodine ablation, thyroid surgery

Graves’ disease, the most common cause of hyperthyroidism, is an autoimmune disease resulting in overproduction of thyroid hormone. If left untreated, patients with Graves’ disease may experience multiple systemic complications including cardiovascular, respiratory, metabolic, reproductive, and skeletal dysfunction (1). Patients may also have neuropsychiatric manifestations of the disease such as emotional lability, anxiety, restlessness, and insomnia. It is not uncommon for these symptoms to increase gradually over time even before the patient is diagnosed with the disease, negatively impacting their quality of life (2). Therefore, diagnosis and symptom relief are the priority in management, followed by definite treatment with thionamides, iodine ablation, or total thyroidectomy. The most common treatment of choice for patients with Graves’ disease varies based on location; long-term use of thionamides is favored in Europe. In the United States, thionamides (methimazole and propylthiouracil) are initiated short term and then patients are frequently offered iodine ablation (3). Total thyroidectomy is usually only considered if patients have contraindications or failure with other treatments (4). Here we present a patient who was offered thyroidectomy after long-term methimazole therapy. We review the advantages and disadvantages of the most commonly prescribed treatments and when to consider total thyroidectomy.

Case presentation

A 30-year-old Hispanic female with a history of Graves’ disease presented to our medical center with chief complaints of increased tremors, palpitations, heat intolerance, abdominal pains, diarrhea, and shortness of breath for approximately 2 weeks. Her symptoms were associated with unintentional weight loss of approximately 5 kg and dysphagia. On presentation, her vital signs were remarkable for a blood pressure of 135/83 mm Hg and a pulse of 115 beats per minute. Her electrocardiogram was consistent with sinus tachycardia. Her physical exam was remarkable for mild bilateral exophthalmos, tremor, and a diffusely enlarged goiter without any distinct nodules or bruits.

The patient was already well known to our institution. She had been diagnosed with Graves’ disease approximately 12 years ago in Puerto Rico and now resided in the United States. She was started on methimazole in Puerto Rico and the same treatment was continued after she established care in our outpatient medical clinic. She often forgot to take methimazole two to three times a day as prescribed and was non-compliant with follow-up visits. As a result, she was frequently admitted to our hospital as well as to other local hospitals for complaints due to uncontrolled hyperthyroidism.

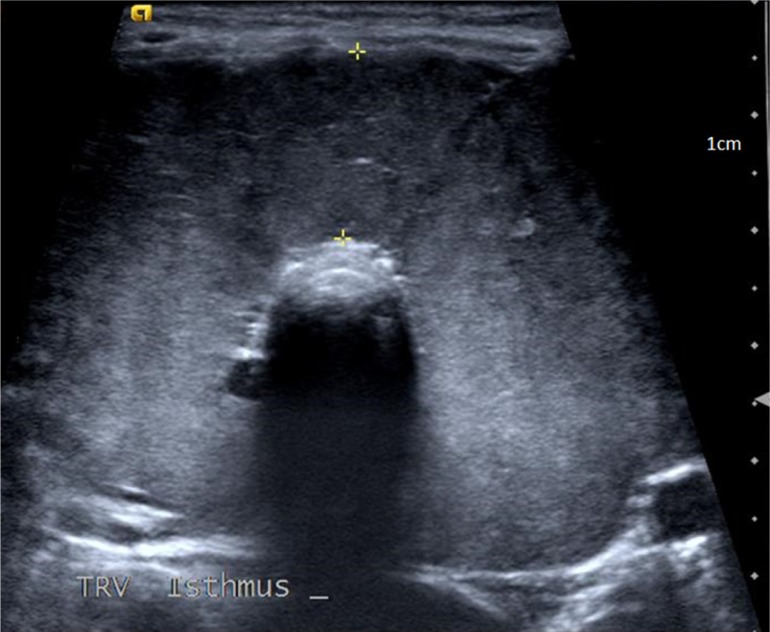

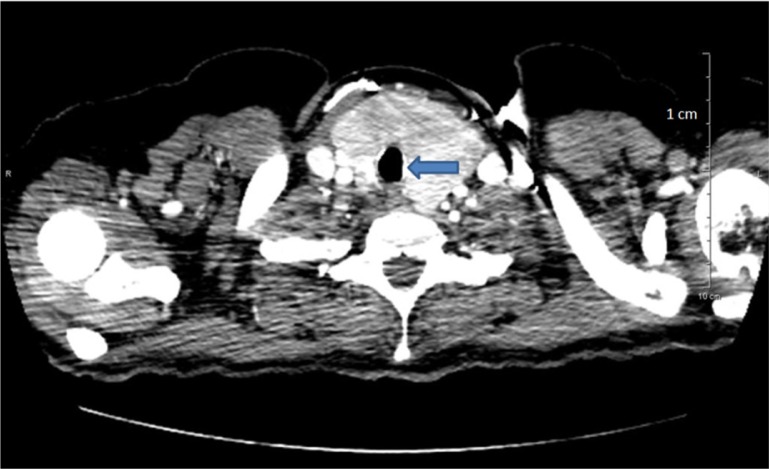

Her thyroid function tests revealed thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) <0.01 mIU/L (reference range 0.27–4.2 mIU/L) and free T4 >7.7 ng/dl (reference range 0.93–1.7 ng/dl). Serum B-hCG was negative. She was treated with hydration, methimazole, and propranolol and her symptoms improved significantly. Ultrasound of the neck was consistent with a diffusely enlarged thyroid gland, each lobe approximately 7 cm in its longest dimension (Fig. 1). Non-contrast computerized tomography (CT) scan revealed subglottic tracheal compression (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Thyroid ultrasound significant for bilateral lobe enlargement.

Fig. 2.

CT scan of neck significant for tracheal compression and narrowing due to thyroid enlargement.

After consultation with the endocrinologist, total thyroidectomy was discussed and she agreed. To minimize risks for thyroid storm, she remained inpatient while awaiting surgery and was maintained on methimazole 10 mg three times daily and propranolol 20 mg three times daily for approximately 1 week. Prior to surgery, repeat free T4 was 1.46 ng/dl and her vital signs were stable with a blood pressure of 117/53 and a pulse of 64 beats per minute. She had an uncomplicated post-operative course and was discharged on levothyroxine. Her thyroid pathology was consistent with follicular hyperplasia and the gland was markedly enlarged at approximately 90 g. She was extensively counseled on the importance of compliance with levothyroxine and precautions for pregnancy were emphasized. Within 3 months after surgery, TSH was 2.3 mIU/L on levothyroxine 125 mcg daily. She had no further emergency room visits or hospital admissions for symptomatic thyroid disease and her exophthalmos remained stable.

Discussion

Graves’ disease is the most common cause of hyperthyroidism. The diagnosis can often easily be made based on eye findings, a goiter, and the typical signs and symptoms of hyperthyroidism such as palpitations, tremors, unintentional weight loss, heat intolerance, and increased irritability. In the presence of typical signs and symptoms, a suppressed TSH, elevated free T4 and increased radioiodine uptake confirm the diagnosis. Thyroid ultrasound consistent with increased vascularity of the gland and positive thyroid receptor antibodies also provide strong supporting evidence for Graves’ disease (5).

Once diagnosis is made, treatment must be initiated to stabilize symptoms. The thionamides available in the United States are methimazole and propylthiouracil. These medications inhibit thyroid hormone synthesis and release. Thionamides are an attractive option because they offer the opportunity to achieve euthyroid state without any exposure to radioactivity or surgery. But this treatment course can be quite time-consuming. Patients typically start thionamides, achieve euthyroid state, and remain on thionamides for at least 12 to 18 months to maintain euthyroidism. During this time, patients will need frequent thyroid function testing and visits to their provider to adjust thionamide doses as needed. Thionamides are then gradually tapered and hopefully patients will be in remission. But chances for remission are low, only occurring in 20 to 30% of patients, and are especially unlikely in patients with large goiters or severe hyperthyroidism (6).

Thionamides are generally well tolerated, although rash, musculoskeletal pains, and gastrointestinal upset may occur. Significant complications reported with these drugs are liver toxicity (more common with propylthiouracil) and agranulocytosis. The risks for these complications usually occur within the first few months of treatment, although they can occur at any time. Propylthiouracil-related liver toxicity has been reported to occur in 1% of treated patients and the incidence of agranulocytosis is less than 1%. So although these complications are rare, they can be life-threatening (7, 8).

Iodine ablation with I131 is another treatment often used for Graves’ disease. I131 is given orally as an outpatient in a single dose, which makes it an attractive treatment option. However, patients must be compliant with numerous precautions such as avoiding contact with children and pregnant women for up to 1 week after treatment and limiting close contact with non-pregnant adults. Radiation is in the patients’ secretions so they must be careful about eating, cleaning, and toileting. After treatment, frequent thyroid function testing is required to monitor for changes in thyroid function as it may take up to 6 months to see the full effects of treatment. Approximately 10% of patients will have I131 treatment failure and will have to undergo iodine precautions and treatment again. After treatment with I131, patients may feel worse before they feel better; they may have transient worsening of disease and require treatment with beta-adrenergic blocking agents or treatment with thionamides. Patients may also develop painful radiation thyroiditis and require glucocorticoid therapy (9).

Thyroidectomy is another option for the treatment of Graves’ disease but is often overlooked. According to United States data published by the American Thyroid Association, only 2% of patients with Graves’ disease and only 7% of patients with Graves’ and thyromegaly are treated with surgery. Surgery is usually only considered if patients develop significant side effects from thionamides or have contraindications to radioactive iodine (4). A 2011 survey investigating clinical practice patterns of providers who care for patients with uncomplicated Graves’ disease found less than 1% of respondents prefer surgery for their patients with uncomplicated Graves’ disease (10). But there are many situations in which thyroidectomy is reasonable to consider.

Graves’ opthalmopathy is one of the most frequently observed extra-thyroidal manifestation of Graves’ disease, ranging from mild to severe. Even patients who do not have obvious eye findings may in fact have some degree of opthalmopathy on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the orbits. The primary goal for Graves’ opthalmopathy is long-term euthyroidism, but this can be difficult to achieve. Thionamide failure and hyperthyroidism recurrence lead to reactivation of autoimmunity and therefore possible worsening of eye disease. Iodine ablation has been associated with exacerbation and progression of Graves’ opthalmopathy, particularly in patients that smoke. Thyroidectomy is the only option that offers rapid resolution of hyperthyroidism, and studies show that Graves’ opthalmopathy stabilizes or even improves after surgery. So for patients with moderate to severe Graves’ opthalmopathy, thyroidectomy is an appropriate management (11).

Females with Graves’ disease who are pregnant may also benefit from surgical management. If hyperthyroidism is uncontrolled during pregnancy, there is an increased risk for premature labor and fetal demise (12). If thionamides are unable to control the hyperthyroidism, or the patient is unable to tolerate thionamide therapy, thyroidectomy is recommended. It is usually performed in the second trimester when the pregnancy is more stable with little risk to the fetus. Propylthiouracil has been preferred over methimazole in the first trimester of pregnancy because of decreased risk for teratogenicity. However, recent studies have demonstrated almost 10% risk for birth defects with both propylthiouracil and methimazole (13). Given these data, female patients may consider thyroidectomy prior to attempting pregnancy so they can avoid exposure to any thionamide during pregnancy.

There are other concerns for female patients with Graves’ disease who are planning pregnancy in the near future. Treatment with both thionamides and iodine ablation may take many months or even years to establish euthyroid state. Initiating treatment with thionamides or iodine ablation may significantly delay female patients’ plans for pregnancy. Furthermore, I131 crosses the placenta and can result in fetal hypothyroidism or cretinism as well as cause other teratogenic effects. So it is critical that patients avoid pregnancy for at least 6 to 12 months after I131 (5). Delaying plans for pregnancy can be frustrating, especially for patients of advanced maternal age. For such patients, thyroidectomy is preferred.

Thyromegaly is another indication for thyroid surgery, especially thyromegaly causing mechanical obstruction and dysphagia. Evidence for obstruction can be obtained clinically and confirmed by non-contrast CT scan of the neck focusing on tracheal abnormalities. Although iodine ablation can decrease gland size, it improves compressive symptoms in less than 50% of patients (9). Therefore, thyroidectomy is often the best treatment for these patients because it will provide the quickest relief for patients’ compressive symptoms and hyperthyroidism with virtually no risk of hyperthyroid recurrence.

The management of thyroid nodules in the setting of Graves’ disease, especially those above 1 cm, can be challenging and is another instance in which thyroidectomy may be preferred. The incidence of thyroid cancer in nodules in the setting of Graves’ disease has been reported to be as high as 15 to 20% (14). When fine needle aspiration of thyroid nodule is suspicious or confirmed for malignancy, thyroidectomy is the only treatment option that allows for simultaneous treatment of both the thyroid cancer and hyperthyroidism. So thyroidectomy is an attractive treatment option for patients with Graves’ disease and thyroid nodules.

The extent of surgery, sub-total thyroidectomy versus total thyroidectomy, was once a topic for debate in the surgical management of Graves’ disease. Permanent hypocalcemia and recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy are all well-known complications from both procedures. Sub-total thyroidectomy was at one time the preferred approach because complications were less frequent, but was associated with approximately 6 to 28% risk for hyperthyroidism relapse (15). Multiple studies including a long-term, 15-year study evaluating more than 1,400 patients who underwent surgery for Graves’ disease found the frequency of permanent hypocalcemia and permanent recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy to be quite low, from 1 to 3%, and not statistically different in patients who underwent total thyroidectomy versus sub-total thyroidectomy. Therefore, total thyroidectomy has become the surgery of choice for Graves’ disease. The most common complication is transient symptomatic hypocalcemia, occurring in 6 to 20% of patients, and is easily managed with calcium and vitamin D supplementation (4, 14–17).

Thyroid storm is also a possible complication from thyroidectomy but the risks for this can be greatly reduced with proper planning. Prior to surgery, patients should be biochemically and clinically optimized and euthyroid prior to surgery using thionamides and β-blockade. Inorganic iodine may also be started preoperatively and continued postoperatively in high-risk patients. When adequate preparations are made, thyroid storm is rarely seen (12).

In conclusion, total thyroidectomy is a safe and effective treatment option for patients with Graves’ disease and is recommended for patients such as ours who are young females of child-bearing age, have thyromegaly, or have Graves’ opthalmopathy. Of course, not all patients are good operative candidates due to comorbid conditions, advanced age, or other factors. Therefore, a candid discussion with patients reviewing the risks and benefits of all treatment options is very important. There is no one perfect treatment, so patients should decide which option is best for them given their personal circumstances and lifestyle. Although it is invasive, patients seeking the fastest results and most rapid resolution to their disease may prefer thyroidectomy over thionamides and iodine ablation. To achieve best possible outcomes and lowest risks for complications, patients desiring surgery should be referred to a high-volume thyroid surgeon whenever possible (17).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr. Sara Wallach, Chief and Chairperson of the Department of Medicine at Saint Francis Medical Center, for her assistance with journal selection as well as her support for the department of endocrinology at our institution. They also thank Dr. Praneet Iyer for his technical support and assistance in preparing this manuscript for submission.

Conflict of interest and funding

We have not received any funding from any sources for this project, nor do we have any conflict of interest. This manuscript is not being considered for publication elsewhere.

References

- 1.Trzepacz PT, Klein I, Roberts M, Greenhouse J, Levey GS. Graves’ disease: An analysis of thyroid hormone levels and hyperthyroid signs and symptoms. Am J Med. 1989;87(5):558. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(89)80614-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Elberling TV, Rasmussen AK, Feldt-Rasmussen U, Hording M, Perrild H, Waldemar G. Impaired health-related quality of life in Graves’ disease. A prospective study. Eur J Endocrinol. 2004;151:549–55. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.1510549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Elfenbein DM, Schneider DF, Havlena J, Chen H, Sippel RS. Clinical and socioeconomic factors influence treatment decisions in Graves’ disease. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22(4):1196–9. doi: 10.1245/s10434-014-4095-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bojic T, Paunovic I, Diklic A, Zivaljevic V, Zoric G, Kalezic N, et al. Total thyroidectomy as a method of choice in the treatment of Graves’ disease-analysis of 1432 patients. BMC Surg. 2015;15(1):39. doi: 10.1186/s12893-015-0023-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gittoes N, Franklyn J. Hyperthyroidism current treatment guidelines. Drugs. 1998;55(4):543–53. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199855040-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gurgul E, Sowinski J. Primary hyperthyroidism-diagnosis and treatment. Indications and contraindications for radioiodine therapy. Nucl Med Rev Cent East Eur. 2011;14(1):29–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huang CH, Li KL, Wu JH, Wang PN, Juang JH. Antithyroid drug-induced Agranulocytosis: Report of 13 cases. Chang Gung Med J. 2007;30(3):242–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Benyounes M, Sempoux C, Daumerie C, Rahier J, Geubel AP. Propylthiouracil-induced severe liver toxicity: An indication for alanine aminotransferase monitoring? World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12(38):6232–4. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i38.6232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ross D. Radioiodine therapy for hyperthyroidism. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:542–50. doi: 10.1056/NEJMct1007101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burch HB, Burman KD, Cooper DS. A 2011 survey of clinical practice patterns in the management of Graves’ disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97(12):4549–58. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-2802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lowery AJ, Kerin MJ. Graves’ opthalmopathy: The case for thyroid surgery. Surgeon. 2009;7(5):290–6. doi: 10.1016/s1479-666x(09)80007-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thompson GB. Surgical management in Graves’ disease. Panminerva Med. 2002;44:287–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anderson SL, Olsen J, Wu CS, Laurberg P. Birth defects after early pregnancy use of antithyroid drugs: A Danish nationwide study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98(11):4373–81. doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-2831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu J, Bargren A, Schaefer S, Chen H, Sippel R. Total thyroidectomy: A safe and effective treatment for Graves’ disease. J Surg Res. 2011;168(1):1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2010.12.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koyuncu A, Aydin C, Topcu O, Gokce ON, Elagoz S, Dokmetas HS. Could total Thyroidectomy become the standard treatment for Graves’ disease? Surg Today. 2010;40:22–5. doi: 10.1007/s00595-008-4026-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sung TY, Lee YM, Yoon JH, Chung KW, Hong SJ. Long term effect of surgery in Graves’ disease: 20 years experience in a single institution. Int J Endocrinol. 2015;2015:1–6. doi: 10.1155/2015/542641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bah RS, Burch HB, Cooper DS, Garber JR, Greenlee MC, Klein I, et al. Hyperthyroidism and other causes of thyrotoxicosis: Management guidelines of the American Thyroid Association and American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists. Thyroid. 2011;21(6):593–645. doi: 10.1089/thy.2010.0417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]