Abstract

Background

Hand hygiene is one of the essential means to prevent the spread of infections. The aim of this study was to assess the knowledge, attitudes, and practice (KAP) of hand hygiene in primary care settings.

Methods

A cross-sectional study using a self-reported questionnaire was conducted in primary care settings located in Riyadh, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, under the service of King Abdulaziz Medical City (KAMC). The Institutional Review Board of KAMC Research Centre approved the study. Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS software.

Results

A total of 237 participants were included in the analysis. Participants who received hand hygiene training within the last 3 years (2012–2014) scored higher on a knowledge scale. Generally, there was an overall positive attitude from participants toward hand hygiene practice. In total, 87.54% acknowledged that they routinely used alcohol-based hand rub, 87.4% had sufficiently decontaminated hands even under high work pressure, and 78.6% addressed that this practice was not affected by less compliant colleagues.

Conclusion

Practicing hand hygiene was suggested to be influenced by variables related to the environmental context, social pressure, and individual attitudes toward hand hygiene. We believe that addressing beliefs, attitudes, capacity, and supportive infrastructures to sustain hand-hygiene routine behaviors are important components of an implementation strategy in enhancing health care workers’ KAP of hand hygiene.

Keywords: hand hygiene, KAP, primary health care

Health care-associated infections are one of the most important public health problems in many countries, resulting in an increase in the morbidity, mortality, and additional costs in health care settings (1–3). Hand hygiene is one of the essential means to prevent the spread of such infections. In 1983, Semmelweis highlighted that cleansing contaminated hands with antiseptic products before and after contact with patients may reduce health care-associated infections (4). Thereafter, CDC published the first formal guidelines on handwashing practices in hospitals (5), followed by guidelines from the Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology (APIC) (6).

Understanding the knowledge, attitudes, and practice (KAP) of handwashing among health care professionals is essential to bring forth a sustained change in behaviors of individuals and institutions and to improve such practices when designing interventions. Several factors are involved in hand hygiene behavior such as attitude, perceived social norm, perceived behavioral control, perceived risk for infection, hand hygiene practices, perceived role model, perceived knowledge, and motivation (7). Despite the number of published studies on hand hygiene, many questions concerning attitudes and knowledge of health care workers (HCWs) remain unanswered. This is particularly true in primary care settings where the volume of patients and complexities of cultural, institutional, and health policy factors can influence the practice of handwashing. Various studies have confirmed an inverse relation between intensity of patient care and adherence to hand hygiene practice (8–10). Additionally, the current burden of the spreading Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) implied an action to review our basic strategies in hand hygiene practice. In a descriptive study (47 cases), MERS-CoV was found to be associated with substantial mortality in admitted patients who have medical comorbidities (11). This calls for effective infection control measures in health care settings, in particular hand hygiene. Hence, KAP of hand hygiene will continue to be a concern and are essential to explore to bridge the theory–practice gap. Thus, the aim of this study was to assess the KAP of hand hygiene among primary care health workers.

Methods

This was a cross-sectional study using a self-reported questionnaire conducted between February and June 2014. The questionnaire was composed of two instruments that were adapted to be consistent with the context of primary care settings. This was done because all the instruments in the literature were designed and worded according to a hospital setting. The first instrument was developed by expert groups from the World Health Organization as a knowledge and perception questionnaire (12). The second one was adapted because of its wider contextual factors compared with the WHO instrument, such as the social support and norms that could influence the attitudes of HCWs toward hand hygiene practice (13). Questions related to hospital settings, such as questions about hospital bed contact and peripheral catheter insertion, were excluded. Additional questions were included to gather participants characteristics (Table 1).

Table 1.

Socio-demographic characteristics

| Item | |

|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 40.1 (9.25) |

| Years of experience, mean (SD) | 12.85 (8.6) |

| Gender, n (%) | |

| Male | 45 (19) |

| Female | 192 (81) |

| Total | 237 |

| Received hand hygiene training, n (%) | 159 (67.1) |

| Occupation, n (%) | |

| Nurses | 189 (79.7) |

| Physicians | 48 (20.3) |

| Total | 237 |

The questionnaire was accompanied by an information sheet explaining the objectives of the study. It was administered in English, without any translation. Two experts in the field of infection control assessed content and face validity of the modified questionnaire. The tool was pilot tested through 30 interviews (not including the sample) to ensure clarity of questions and to eliminate ambiguity.

In the knowledge section, the total score was calculated by adding up 28 questions assessing the participant's knowledge, and each correct answer was awarded with 1 point and unanswered questions and wrong answers were awarded 0 points. The maximum achievable score was 28. In the attitude section, all items (nine questions) were scored on a 5-point scale: 1 (fully agree) to 5 (fully disagree), with a maximum score of 45. In the practice section, answers were reported on either “Yes” or “No” options (two questions) or a 5-point numeric scale (four questions), ranging from 0 to 100%.

The study was conducted in primary care settings located in the central region of Riyadh, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, under the service of King Abdulaziz Medical City (KAMC). Participants were included if they were physicians or nurses working in the targeted primary care centers.

Based on the published literature we used a precision estimate of 10% and anticipated hand hygiene knowledge of 50% (the most conservative value). Using a 95% confidence interval, 277 completed survey forms would be sufficient to accurately assess knowledge, attitude and practice about hand hygiene. Assuming a response rate of 70% and a completion rate of 80%, 400 questionnaires were distributed. 100 participants from each of the four primary care centers were randomly selected using electronic random number generator. The questionnaires were sent in sealed envelopes and placed in pigeonholes of the randomly selected participants in each practice.

Data were entered into SPSS v.20 by a professional data entry clerk and revised and cleaned by another clerk. The data were then analyzed using IBM SPSS software (v.20). Categorical variables were described using frequency and percentages. Continuous variables were summarized using mean±standard deviation. Chi-square test was used for comparing proportions. Student t-test/ANOVA was used for comparing means. Statistical significance was set to 0.05 or less and a confidence interval of 95%.

Ethical considerations

Verbal consent was obtained from all subjects before they participated in the study. To keep their confidentiality, the returned questionnaires were kept anonymous and an identification code was assigned to each questionnaire in order to send a reminder to those who did not return the questionnaire. Participant details were kept in a password-protected computer that was accessible only to the researchers. Additionally, Institutional Review Board of King Abdullah International Medical Research Centre (KAIMRC) approved the project and ensured proper ethical conduct throughout the study.

Results

A total of 237 participants from five primary health care centers were included in the study (response rate = 59%). Female participants represented 81% (191) of the sample. The majority of respondents were nurses: 79.7% (189). The remaining 20.3% (48) were physicians. The age of participants ranged from 24 to 66 years, with a mean age of 40 years (SD±9.25). Participants’ experiences as HCWs ranged from 1 to 38 years, with a mean of 12.85 years (SD±8.59). In total, 67.1% (159) of participants acknowledged that they received training in hand hygiene within the last 3 years (2012–2014).

Participants’ knowledge

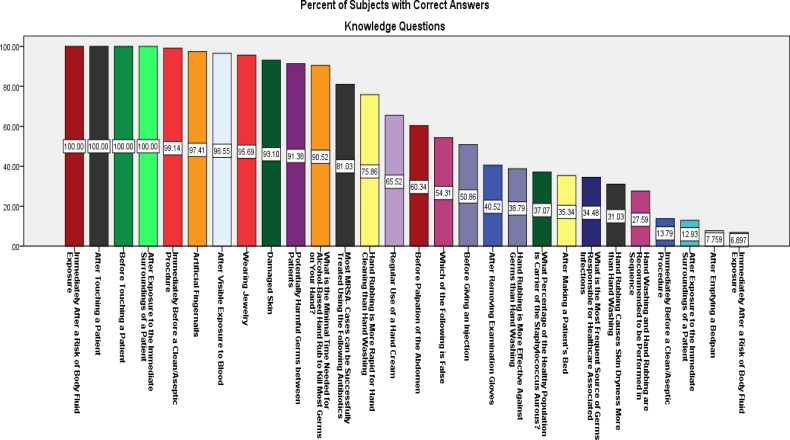

In the knowledge section of the questionnaire, the minimum knowledge score achieved was 5 and the maximum was 21 (Fig. 1), with a mean of 14 (SD±2.85). Nurses scored higher (14.1) than physicians (13.8) on knowledge scale; however, this was not statistically significant (p = 0.58). Moreover, the participants who received hand hygiene training within the last 3 years generally scored higher on knowledge scale (14.2) than those who did not have such a training (13.5); nevertheless, the difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.09). Knowledge score was not affected by the years of the participants’ work experience (p = 0.4). Those who reported using the alcohol-based hand rub routinely had significantly higher knowledge score (14.3) than those who did not use the hand rub routinely (12.5) (p=0.01)

Fig. 1.

Percent of correct answers of knowledge questions.

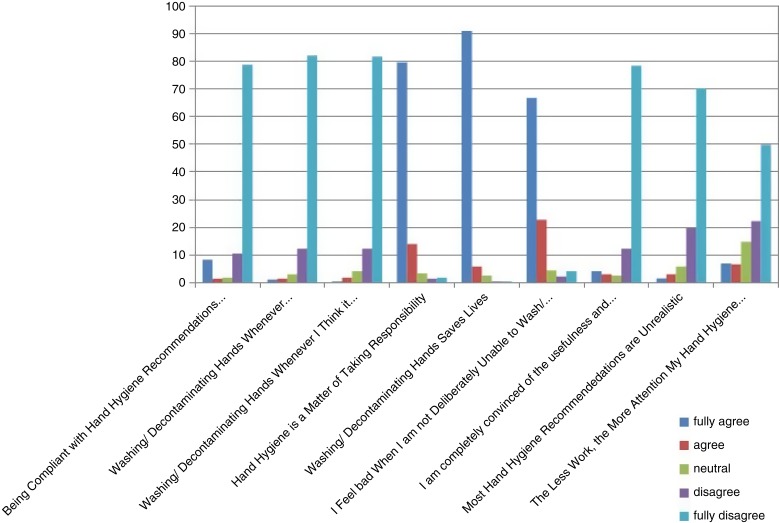

Participants’ attitude

In the attitude section of the questionnaire, only 218 (92%) participants completed the questions. Generally, there was an overall positive attitude from participants toward hand hygiene practice (Fig. 2). Participants agreed fully that hand hygiene is important, possible, and not time consuming; believed it saves lives; and would feel bad if they were not able to wash their hands. However, half the participants believed that their attention to proper hand hygiene practices is negatively affected by their workload.

Fig. 2.

Answers to attitude questions.

Attitude toward hand hygiene was not correlated with the participants’ gender, years of experience, or training. However, nurses were found to exhibit a better attitude toward hand hygiene than physicians (p=0.02). Also, age was positively correlated with a positive attitude toward hand hygiene (Spearman's rho = 0.14, p=0.04)

Participants’ practice of hand hygiene

In the practice section of the questionnaire, 81.9% (194) acknowledged that they routinely make use of alcohol-based hand rub, 86.5% (205) had sufficiently decontaminated hands even under high work pressure, and 77.6% (184) addressed that their hand hygiene practice was not affected by less compliant colleagues. Also, 55.3% (131) confirmed that their hand hygiene practice would improve if skin moisturizers were made available to them.

There was no correlation between the frequency of practicing hand hygiene and the participants’ gender, age, and years of experience. However, there was a significant correlation between such practices and participants’ training in hand hygiene in the last 3 years (p=0.02). Also, nurses were found to be more compliant with using alcohol-based hand rub than physicians (p=0.03).

There was a significant correlation between the level of practicing hand rubbing with alcohol and higher score of knowledge (p≤0.01). Also those who stated that their practice was not affected by workload were found to have a significantly higher knowledge score (p≤0.01). Participants who stated they were able to resist peer pressure had slightly higher mean knowledge score, but the difference was not statistically significant (p=0.7). Moreover, those whose practice was affected by the availability of skin moisturizers scored significantly lower on attitude score (p≤0.01).

Discussion

This study highlighted very important aspects of KAP of hand hygiene among various health workers in primary care settings. Most of the studies of hand hygiene have measured knowledge (cognitive domain) and general practices (behavioral domain) rather than affective factors (values, beliefs, perceptions, motivation). Our study measured all of these domains. This is essential, in particular, with the current epidemics of MERS in the Arab countries, when all HCWs need to be vigilant to prevent and control such infections in the community. In addition to the fact that hand hygiene has been considered the leading measure to prevent health care-associated infections (14), we found a statistically significant correlation between participants’ practice of hand hygiene and their previous training and their profession, in particular being a nurse. This finding is in line with other studies, which showed that training and campaign exposure increased the likelihood of a positive attitude and increased compliance with hand hygiene (15).

In our survey, those whose practice was affected by the availability of skin moisturizers scored significantly lower on attitude score (p≤0.01). The implemented method of hand hygiene also influences practice, and the use of an alcohol-based hand rub preparation for hand hygiene, recently defined as the standard of care, has been associated with striking enhancement of compliance (16). Studies have shown that adherence to hand hygiene recommendations is influenced by knowledge; awareness of personal and group performance; workload; and type, tolerance, and accessibility of hand hygiene products (16, 17).

Practicing hand hygiene among HCWs was suggested to be influenced by variables related to the environmental context, social pressure, and the actual and perceived risk for cross-transmission and to a positive individual attitude toward hand hygiene (8). This is particularly true in the current surge of MERS-CoV in Saudi Arabia at the national level and Middle East at large, where HCWs have to be vigilant to strict infection control procedures such as hand hygiene practice. In Saudi Arabia, it has been found that some of the nurses did not follow infection control procedures fully and therefore had maximal exposure to MERS-CoV (18).

Social cognitive and psychological determinants (i.e., knowledge, intention, beliefs and perceptions) might provide some insight into hand hygiene behavior. This has been explained by the social cognitive theory, which is widely used to explain behaviors and behavioral intentions in different social situations. Social Cognitive theory has also been used to explain adherence to hand hygiene practice among nurses (19–21). This theory postulated that behavior (practice) could be anticipated from intention, which, in turn, is molded by personal attitudes, perceived behavioral control, and subjective norms (22). Hence, intention is assumed to be the most instant factor to determine behavior.

Our participants’ intentions were positive in terms of willingness, perceived importance, realistic insight, and belief that hand hygiene will save lives.

This intention might explain the participants’ high level performance of hand hygiene practice. They acknowledged that they routinely make use of alcohol-based hand rub (87.54%), had sufficiently decontaminate hands even under high work pressure (87.4%), and addressed that their hand hygiene practice was not affected by less compliant colleagues (78.6%). Ajzen proposed that past experiences shape social cognitive factors, which, in turn, determine behavior (23). Therefore, it can be assumed that once good working conditions are guaranteed, the real and perceived individual control over hand hygiene might improve, with a positive succeeding effect on hand hygiene behavior.

Barriers to appropriate hand hygiene practice have been studied and reported extensively, but even in settings with optimal environmental conditions, compliance appears to range from 50 to 60% at most (24). However, our participants showed a higher level of hand hygiene practice (>78%). This could be explained by the high level of awareness program, policy, and procedures that are in place in our institution (KAMC). The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia is one of the 42 countries actively participating in a WHO-sponsored hygiene promotion campaign targeting HCWs (16). Following the ministerial pledge to the First Global Patient Safety Challenge and the launch of a national campaign, a hand hygiene campaign was undertaken in 2005.

Our findings highlighted an alarming challenge in identifying unique opportunities for targeted quality improvement programs on hand hygiene at the primary care settings, where an excess of patients has been a particular characteristic compared to hospital settings. Hence, use of theory and evidence from implementation science can assist evidence-based implementation. Furthermore, adoption of previously tested models could be suggested, such as the stepwise approach model for effective implementation that takes the user through a series of rational and deliberate steps to accomplish practice improvement (25).

Implementation project leaders tend to prefer voluntary, intrinsic motivation-focused strategies (26). For example, supportive strategies such as reminders, decision support, and rewards were mostly effective. Moreover, combined strategies were recognized as more effective than were single strategies (27).

Study limitations

Although the English language is the official language of communication in the work environment in KAMC, English is a second language to most HCWs, and this might affect how participants responded to the survey tool. We did not identify any language barriers during the pilot testing of the data collection tool.

Conclusion

We conclude with a suggestion for innovation by instructing patients to remind HCWs to perform hand hygiene, which proved to have a positive effect on HCWs’ compliance with hand hygiene practice (28). However, a disadvantage of this strategy was that a substantial number of patients reported reluctance or uneasiness in reminding health care professionals. Such approaches should be tested and evidence of their effectiveness in various health care settings must be also explored in further research in order to be implemented to enhance the KAP of hand hygiene among HCWs.

Acknowledgment

We thank Ms Hind AL Shatry, as well as all the health care workers who made time in their busy schedules to complete the questionnaire, and Ms Cora Passive for her practical contributions to this study. We also thank KAIMRC for funding this project.

Conflict of interest and funding

Authors declare no conflicting interests.

References

- 1.Mauldin PD, Salgado CD, Hansen IS, Durup DT, Bosso JA. Attributable hospital cost and length of stay associated with health care-associated infections caused by antibiotic-resistant gram-negative bacteria. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54(1):109–15. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01041-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Defez C, Fabbro-Peray P, Cazaban M, Boudemaghe T, Sotto A, Daurès J. Additional direct medical costs of nosocomial infections: An estimation from a cohort of patients in a French university hospital. J Hosp Infect. 2008;68(2):130–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2007.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Llata E, Gaynes RP, Fridkin S, Weinstein RA. Measuring the scope and magnitude of hospital-associated infection in the United States: The value of prevalence surveys. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48(10):1434–40. doi: 10.1086/598328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Semmelweis I. The etiology, concept and prophylaxis of childbed fever [excerpts] In: Buck C, Llopis A, Najera E, Terris M, editors. The challenge of epidemiology—issues and selected readings. Washington: PAHO Scientific Publication; 1988. pp. 46–59. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garner JS, Favero MS. CDC Guideline for Handwashing and Hospital Environmental Control, 1985. Infection Control. 1986;7(4):231–43. doi: 10.1017/s0195941700084022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Larson EL. APIC guidelines for handwashing and hand antisepsis in health care settings. Am J Infect Contr. 1995;23(4):251–69. doi: 10.1016/0196-6553(95)90070-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Larson EL, Early E, Cloonan P, Sugrue S, Parides M. An organizational climate intervention associated with increased handwashing and decreased nosocomial infections. Behav Med. 2000;26(1):14–22. doi: 10.1080/08964280009595749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pittet D, Simon A, Hugonnet S, Pessoa-Silva CL, Sauvan V, Perneger TV. Hand hygiene among physicians: Performance, beliefs, and perceptions. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141(1):1–8. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-141-1-200407060-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harbarth S, Pittet D, Grady L, Goldmann DA. Compliance with hand hygiene practice in pediatric intensive care. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2001;2(4):311–4. doi: 10.1097/00130478-200110000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arenas MD, Sánchez-Payá J, Barril G, García-Valdecasas J, Gorriz JL, Soriano A, et al. A multicentric survey of the practice of hand hygiene in haemodialysis units: Factors affecting compliance. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2005;20(6):1164–71. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfh759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Assiri A, Al-Tawfiq JA, Al-Rabeeah AA, Al-Rabiah FA, Al-Hajjar S, Al-Barrak A, et al. Epidemiological, demographic, and clinical characteristics of 47 cases of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus disease from Saudi Arabia: A descriptive study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13(9):752–61. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70204-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.WHO. Hand hygiene knowledge questionnaire for health-care workers. 2009. Available from: http://www.who.int/gpsc/5may/tools/evaluation_feedback/en/ [cited 21 October 2012]

- 13.De Wandel D, Maes L, Labeau S, Vereecken C, Blot S. Behavioral determinants of hand hygiene compliance in intensive care units. Am J Crit Care. 2010;19(3):230–9. doi: 10.4037/ajcc2010892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Borghesi A, Stronati M. Strategies for the prevention of hospital-acquired infections in the neonatal intensive care unit. J Hosp Infect. 2008;68(4):293–300. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2008.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sax H, Uçkay I, Richet H, Allegranzi B, Pittet D. Determinants of good adherence to hand hygiene among healthcare workers who have extensive exposure to hand hygiene campaigns. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2007;28(11):1267–74. doi: 10.1086/521663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boyce JM, Pittet D. Guideline for hand hygiene in health-care settings: Recommendations of the Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee and the HICPAC/SHEA/APIC/IDSA Hand Hygiene Task Force. Am J Infect Control. 2002;30(8):S1–46. doi: 10.1067/mic.2002.130391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pittet D, Boyce JM. Hand hygiene and patient care: Pursuing the Semmelweis legacy. Lancet Infect Dis. 2001;1:9–20. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Memish ZA, Zumla AI, Assiri A. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infections in health care workers. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(9):884–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1308698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grube JW, Morgan M, McGree ST. Attitudes and normative beliefs as predictors of smoking intentions and behaviours: A test of three models. Br J Soc Psychol. 1986;25(2):81–93. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8309.1986.tb00707.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Godin G, Bélanger-Gravel A, Eccles M, Grimshaw J. Healthcare professionals’ intentions and behaviours: A systematic review of studies based on social cognitive theories. Implement Sci. 2008;3(36):1–12. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-3-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.O'Boyle CA, Henly SJ, Larson E. Understanding adherence to hand hygiene recommendations: The theory of planned behavior. Am J Infect Contr. 2001;29(6):352–60. doi: 10.1067/mic.2001.18405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Conner M, Armitage CJ. Extending the theory of planned behavior: A review and avenues for further research. J Appl Soc Psychol. 1998;28(15):1429–64. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ajzen I, Driver BL. Prediction of leisure participation from behavioral, normative, and control beliefs: An application of the theory of planned behavior. Leisure Sci. 1991;13(3):185–204. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pittet D, Hugonnet S, Harbarth S, Mourouga P, Sauvan V, Touveneau S, et al. Effectiveness of a hospital-wide programme to improve compliance with hand hygiene. Lancet. 2000;356(9238):1307–12. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)02814-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grol R, Grimshaw J. From best evidence to best practice: Effective implementation of change in patients’ care. Lancet. 2003;362(9391):1225–30. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14546-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Van Achterberg T, Schoonhoven L, Grol R. Nursing implementation science: How evidence-based nursing requires evidence-based implementation. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2008;40(4):302–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2008.00243.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grimshaw JM, Eccles MP. Is evidence-based implementation of evidence-based care possible? Med J Aust. 2004;180(6 Suppl):S50–1. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2004.tb05945.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McGuckin M, Taylor A, Martin V, Porten L, Salcido R. Evaluation of a patient education model for increasing hand hygiene compliance in an inpatient rehabilitation unit. Am J Infect Control. 2004;32(4):235–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2003.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]