Abstract

An 81-year-old woman with a history of malignant melanoma who presented with dyspnea and fatigue was found to have metastases to the stomach detected on endoscopy. Primary cutaneous malignant melanoma with gastric metastases is a rare occurrence, and it is often not detected until autopsy because of its non-specific manifestations.

Keywords: melanoma, gastric, metastases, malignant, HMB-45, S-100, prognosis

Melanoma can spread to any organ, and it is the most common metastatic tumor of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract; the most commonly involved sites include the small and large bowels and rectum. However, gastric metastases are a rare phenomenon. Because it is uncommon and its clinical manifestations are non-specific, it is often not detected until autopsy (1). Studies show that 60% of patients who die of melanoma are found to have metastases to the GI tract on autopsy, with gastric involvement in approximately 20% of these cases (1–3). We are reporting a case of melanoma with gastric metastases. We will examine common clinical findings and review both pathological and endoscopic findings as well as discuss treatment options.

Case report

An 81-year-old woman with history of melanoma presented to the emergency department with a chief complaint of dyspnea and fatigue. Initial laboratory work-up revealed anemia, with hemoglobin of 7.6 gm/dL and hematocrit of 23.8%. She denied any history of melena. Liver function tests revealed alkaline phosphatase 819 unit/L, AST 131 unit/L, ALT 129 unit/L, albumin 2.0 gm/dL, and total bilirubin 0.6 mg/dL. Hepatitis panel was negative. Coagulation profile and basic metabolic panel were unremarkable. Abdominal and rectal exams were unremarkable.

One month earlier, a computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen with contrast revealed small liver masses, but no gastric lesions were noted. The patient had a history of recurrent acral lentiginous melanoma of the foot 1 year earlier, which was treated with amputation of the fifth toe and oral chemotherapy. She had recurrence of the melanoma on her left leg 6 months earlier, which was treated with radiation and chemotherapy (temozolomide).

Given her anemia and history of melanoma, an upper endoscopy was performed. In the stomach, there were multiple hyperpigmented lesions involving the cardia, fundus, and body, all varying in size, shape, and morphology (Figs. 1–2). Some were macular, and some appeared to be ulcerative and umbilicated. In the duodenum, a solitary hyperpigmented lesion was noted. Multiple cold biopsies were obtained. A digital rectal examination showed non-bleeding internal hemorrhoids. A colonoscopy was also performed which revealed only scattered diverticuli. Pathology revealed that the lamina propria of both the duodenum and stomach was infiltrated by a population of single, atypical, and pigmented discohesive cells (Figs. 3–4). The cells expressed the melanoma marker HMB-45 on immunohistochemical stains, which were weakly positive for S-100 protein (Fig. 5).

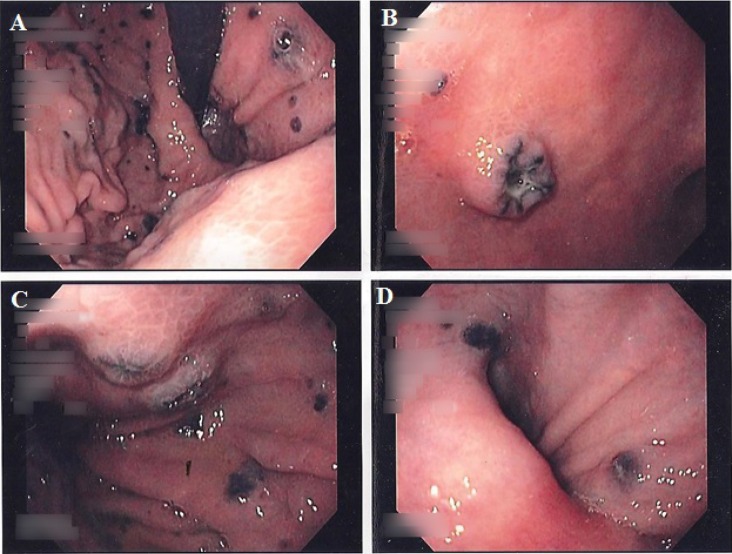

Fig. 1.

Endoscopic images demonstrating multiple hyperpigmented lesions involving the cardia (A), umbilicated lesions in the body (B–C), and hyperpigmented lesions in the pylorus (D).

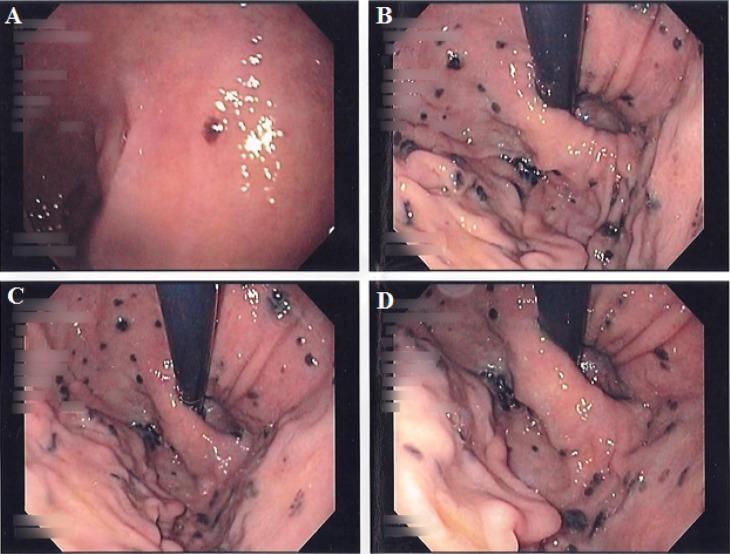

Fig. 2.

Endoscopic images demonstrating a solitary hyperpigmented lesion in the duodenum (A) and multiple hyperpigmented lesions involving the cardia and fundus (B–D).

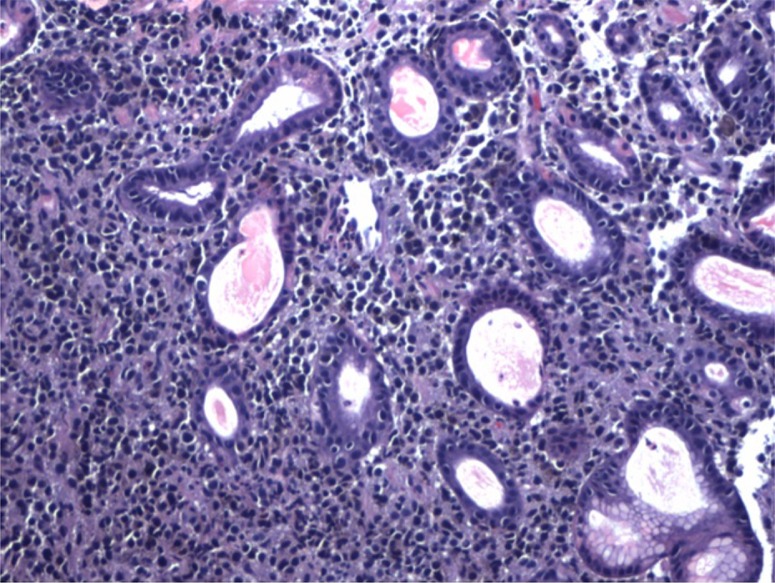

Fig. 3.

H&E stained slide at 10× magnification demonstrating malignant cells with hyperchromatic nuclei and pink-to-purple cytoplasm infiltrating around benign gastric glands. Some pigment deposition can be seen within the cells of the malignant melanoma.

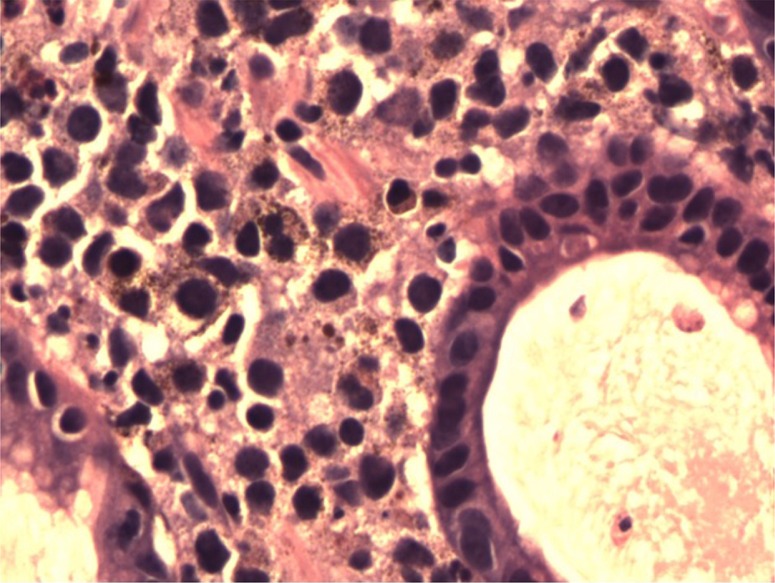

Fig. 4.

H&E stained slide at 40× magnification demonstrating the cells of the malignant melanoma infiltrating benign gastric glands. The nuclei of the melanoma are large, irregular, and hyperchromatic. Brown to black granular melanin pigment is seen associated with the cells of the melanoma.

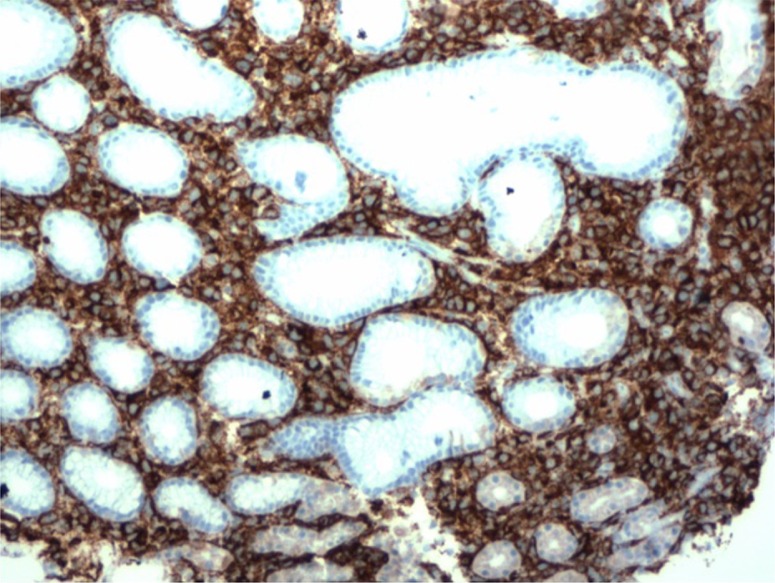

Fig. 5.

Slide stained with an antibody to melanoma marker HMB45 at 10× magnification. The cells of the melanoma strongly express HMB45 as evidenced by brown cytoplasmic staining in the melanoma cells. The benign gastric glands are negative for HMB45.

Considering these findings in the setting of her recurrent melanoma, we concluded that the patient had malignant melanoma with metastases to the stomach and duodenal bulb. Because of the recurrence of her cancer and failure of chemotherapy, the patient did not wish to have any further treatment.

Discussion

The average time from diagnosis of a primary cutaneous malignant melanoma to metastasis to the GI tract is 52 months (4). Diagnosis is rarely made before surgery or endoscopy, because associated symptoms are non-specific and only manifest in 1–4% of patients with metastases; such symptoms include fatigue, nausea, vomiting, abdominal cramping or pain, weight loss, melena, and anemia (1, 4). Diagnosis is made by radiographic studies and endoscopic evaluation. The sensitivity of CT, however, is only 60–70% in detecting metastases. Therefore, if a CT is negative in a patient with a melanoma with GI signs and symptoms, metastasis cannot be ruled out and further studies should be done (2).

Endoscopic tumor appearance may be classified into three types: ulcerated melanotic nodules arising on normal rugae, submucosal masses with ulcerations, and mass lesions with necrosis and melanosis (1). The classic appearance is multiple, small nodules that may be pigmented at endoscopy or may ulcerate to produce a bull's-eye or ‘target-like’ appearance (3, 5). The majority of gastric metastases occur in the body and fundus, most often at the greater curvature (6). Confirmation of melanoma is made if the biopsies immunostain positively with S-100 protein and the premelanosome glycoprotein monoclonal antibody HMB-45 (7).

It is also important to distinguish between a primary GI mucosal melanoma and metastatic melanoma. The criteria for a diagnosis of primary intestinal melanoma include 1) no evidence of concurrent melanoma or atypical melanocytic lesion of the skin, 2) absence of extraintestinal metastatic spread of melanoma, and 3) presence of intramucosal lesions in the overlying or adjacent intestinal epithelium (1).

In patients with GI tract metastases, systemic chemotherapy has been used as a treatment modality. However, patients may experience severe complications as a consequence of the immunocompromised state, and no overall mortality benefit has been found (7, 8). Historically, melanoma is believed to be a radioresistant tumor. Radiation therapy has been used as an adjuvant therapy after resection with promising results, but there is need for further investigation (9).

Because metastases to the stomach are rare, the data supporting gastric surgery are limited beyond case reports. There are no set criteria for surgical intervention, but treatment for gastric metastases should include surgical resection whenever possible (9). Even if the resection is incomplete, surgical intervention offers symptomatic and mortality benefit (10). In a retrospective review of 124 patients who had melanoma with GI metastases, median survival for those who underwent resection of the GI tract was 48.9 months compared with 5.7 months in those who underwent palliative and non-surgical interventions (11).

Conclusion

Clinical manifestations of GI metastatic melanoma are usually non-specific, and because of this, most cases are not detected until autopsy. Therefore, it is important to have a high index of suspicion for metastasis in patients with a history of malignant melanoma who present with GI symptoms and anemia. Patients should undergo endoscopy with thorough inspection of the mucosa. If the diagnosis is confirmed via immunohistochemical staining, treatment with surgical resection should be considered as it may prolong survival.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Lyn Camire, MA, ELS, of their department for editorial assistance.

Authors' contributions

KW completed background research, drafted, and edited the manuscript, and she is the article guarantor.

Conflict of interest and funding

The authors have not received any funding or benefits from industry or elsewhere to conduct this study.

References

- 1.Blecker D, Abraham S, Furth EE, Kochman ML. Melanoma in the gastrointestinal tract. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:3427–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.01604.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liang KV, Sanderson SO, Nowakowski GS, Arora AS. Metastatic malignant melanoma of the gastrointestinal tract. Mayo Clin Proc. 2006;81:511–16. doi: 10.4065/81.4.511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McDermott VG, Low VH, Keogan MT, Lawrence JA, Paulson EK. Malignant melanoma metastatic to the gastrointestinal tract. Am J Roentgenol. 1996;166:809–13. doi: 10.2214/ajr.166.4.8610555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patel K, Ward ST, Packer T, Brown S, Marsden J, Thomson M, et al. Malignant melanoma of the gastro-intestinal tract: A case series. Int J Surg. 2014;12:523–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2014.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bresalier RS, Lance MP, Yamada T, Alpers DH, Laine L, Kaplowitz N, Owyang C, Powell DW, editors. Atlas of gastroenterology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2003. Tumors of the small intestine; pp. 362–78. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goral V, Ucmak F, Yildirim S, Barutcu S, Ileri S, Aslan I, et al. Malignant melanoma of the stomach presenting in a woman: A case report. J Med Case Rep. 2011;5:94. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-5-94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schuchter LM, Green R, Fraker D. Primary and metastatic diseases in malignant melanoma of the gastrointestinal tract. Curr Opin Oncol. 2000;12:181–5. doi: 10.1097/00001622-200003000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Verma S, Petrella T, Hamm C, Bak K, Charette M. Biochemotherapy for the treatment of metastatic malignant melanoma: A clinical practice guideline. Curr Oncol. 2008;15:85–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Markovic SN, Erickson LA, Rao RD, Weenig RH, Pockaj BA, Bardia A, et al. Malignant melanoma in the 21st century, part 2: Staging, prognosis, and treatment. Mayo Clin Proc. 2007;82:490–513. doi: 10.4065/82.4.490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berger AC, Buell JF, Venzon D, Baker AR, Libutti SK. Management of symptomatic malignant melanoma of the gastrointestinal tract. Ann Surg Oncol. 1999;6:155–60. doi: 10.1007/s10434-999-0155-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ollila DW, Essner R, Wanek LA, Morton DL. Surgical resection for melanoma metastatic to the gastrointestinal tract. Arch Surg. 1996;131:975–9. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1996.01430210073013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]