Abstract

Background and purpose

Total hip replacement (THR) is not recommended for children and very young teenagers because early and repetitive revisions are likely. We investigated the clinical and radiographic outcomes of THR performed in children and teenage patients.

Patients and methods

We included 111 patients (132 hips) who underwent THR before 20 years of age. They were identified in the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register, together with information on the primary diagnosis, types of implants, and any revisions that required implant change. Radiographs and Harris hip score (HHS) were also evaluated.

Results

The mean age at primary THR was 17 (11–19) years and the mean follow-up time was 14 (3–26) years. The 10-year survival rate after primary THR (with the endpoint being any revision) was 70%. 39 patients had at least 1 revision and 16 patients had 2 or more revisions. In the latest radiographs, osteolysis and atrophy were observed in 19% and 27% of the acetabulae and 21% and 62% of the femurs, respectively. The mean HHS at the final follow-up was 83 (15–100).

Interpretation

The clinical score after THR in these young patients was acceptable, but many revisions had been performed. However, young patients with developmental dysplasia of the hip had lower implant survival. Moreover, the bone stock in these patients was poor, which could complicate future revisions.

Total hip replacement (THR) is rarely recommended for children and young adults because several revisions can be expected. Young age and high activity levels are well-known risk factors for revision (Münger et al. 2006, Flugsrud et al. 2007). After revision, implant survival is poor and recovery of hip function is worse than after primary THR (Lie et al. 2004, Bischel et al. 2012, Adelani et al. 2014). Besides, reduction in bone stock makes multiple revisions complicated (Bischel et al. 2012).

Assessment of the balance between risks and benefits of THR is therefore important in young patients. However, to date there have only been a few long-term reports on THR in young patients, especially those less than 20 years old (Cage et al. 1992, Torchia et al. 1996, Bessette et al. 2003, Wroblewski et al. 2010). We therefore analyzed the long-term outcome from a large series of THRs in very young patients.

Patients and methods

Patients

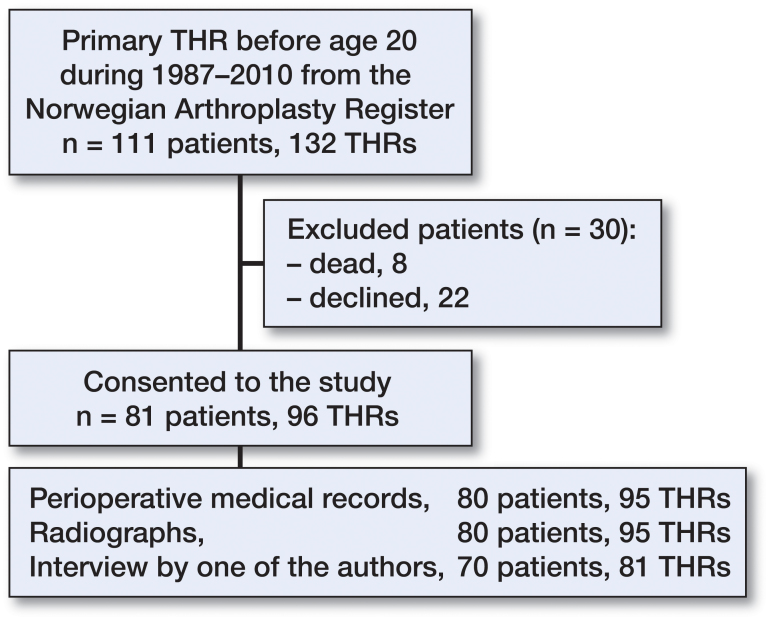

Using the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register (NAR) (Havelin et al. 2000), we identified patients who had undergone a primary THR before the age of 20 years in the period 1987–2010. We included 111 patients with 132 hips, reported from 15 hospitals in Norway. 49 of the patients were male (56 hips). Information on their revisions was obtained up to December 31, 2013. We obtained written informed consent from 81 patients to obtain their medical records and radiographs (96 hips) (Figure 1). Perioperative medical records from 80 patients (95 hips) were available, and there were postoperative radiographs from 80 patients (94 hips).

Figure 1.

Flow of patient inclusion and data collection.

The Norwegian Arthroplasty Register (NAR)

The NAR data include primary THRs and the following reoperations: changes of acetabular or femoral components, and of femoral head or liner, and removal of implants. From the NAR, we also obtained information on the date of surgery, previous surgeries, type of surgery, type of implant, diagnosis at the primary THR, and indications for reoperations. We defined revision as removal or exchange of 1 or more components, including liner.

Diagnosis

In addition to data from the NAR, we obtained details of the diagnosis from the medical records, if available. Before 2011, Perthes’ disease and slipped capital femoral epiphysis (SCFE) were registered as one common item. When the diagnosis was unclear in the medical records, SCFE was assumed if the patient had a history of fixation for SCFE. If not, we kept the diagnosis as Perthes’ disease/SCFE.

Causes of revision

The NAR has 10 categories for the cause of revision (Table 1), and accepts multiple selections and free descriptions. To highlight the main cause, we gave each patient 1 major diagnosis. If “Deep infection,” “Dislocation,” or “Fracture” was selected, we prioritized these diagnoses. “Loosening” without “Deep infection,” was categorized as “Aseptic loosening.” If “Osteolysis without loosening” was selected and the implant had been changed, we categorized it as “Osteolysis.” If the procedure was liner exchange only, we categorized it as “Wear.” If “Pain” alone was selected, we categorized it as “Pain only.” An implantation of a new implant following previous removal was categorized as “2-stage revision.”

Table 1.

Category of indications for revision

| Register | Current study |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Loosening of acetabular component | Priority diagnosis | 1 | Infection |

| 2 | Dislocation | |||

| 2 | Loosening of femoral component | 3 | Fracture | |

| 3 | Dislocation | Other specified | 4 | Aseptic loosening |

| 4 | Deep infection | 5 | Osteolysis | |

| 5 | Fracture in acetabulum | 6 | Wear | |

| 6 | Fracture in femur | 7 | Pain only | |

| 7 | Pain | 8 | 2-stage revision | |

| 8 | Osteolysis in acetabulum without loosening | 9 | Other | |

| 9 | Osteolysis in femur without loosening | |||

| 10 | Other (in text) | |||

Radiographic analysis

We obtained radiographs of 94 hips in 80 patients. 1 patient with informed consent was excluded because the patient had emigrated and the radiographs had not been stored. We evaluated the latest radiographs for loosening, osteolysis, bone defects, atrophy, and ectopic calcification. For assessment of migration or loosening of implants, we examined the first postoperative radiographs of the implants, if available. All radiographs were analyzed by one of the authors (MT).

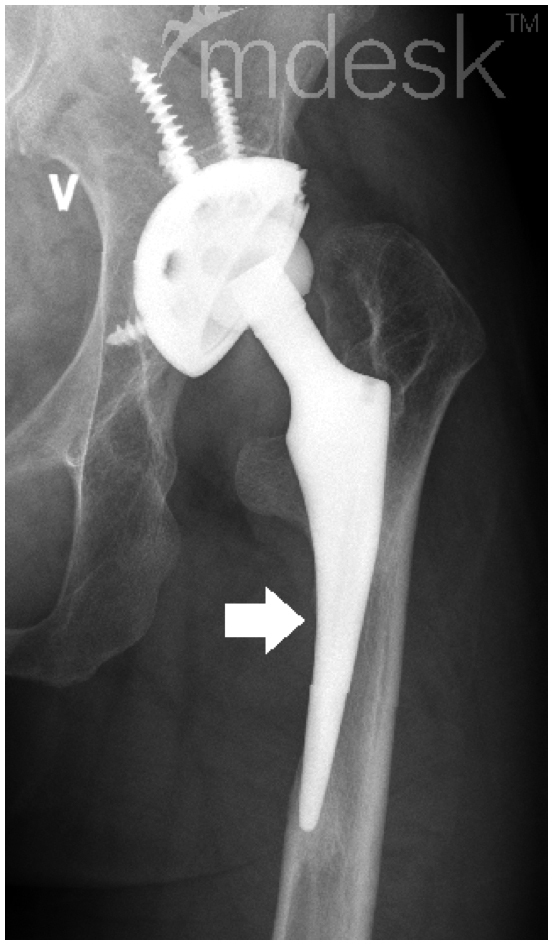

The locations of radiographic findings were recorded according to the 3 acetabular zones described by Charnley and to the 7 femoral zones described by Gruen. Osteolysis was defined as a non-linear lucency of 3 mm or more around the prosthesis (Claus et al. 2003). Loosening of an acetabular component was determined from evidence of migration and a radiolucent line (Hodgkinson et al. 1988, Johnston et al. 1990). An acetabular component was diagnosed as “loose” when it had migrated more than 4 mm in either the horizontal or the vertical direction, or if it had tilted by more than 5°. Cemented acetabular components that had continuous radiolucent lines with any thickness in all 3 zones were categorized as being loose. Uncemented acetabular components that had radiolucent lines wider than 2 mm in all 3 zones were categorized as being loose. Loosening of an uncemented stem was defined by whether the stem was considered to be unstable according to the criteria of Engh et al. (1990). Loosening of a cemented stem was defined by whether we found a continuous radiolucent line around the stem, or stem subsidence of >5 mm. Bone defects were assessed using Paprosky’s classifications (Paprosky et al. 1994, Della Valle and Paprosky 2004). Bone areas with reduced density in the acetabulum and proximal femur were recorded as “atrophy” (Wangen et al. 2008). Thinning of the femoral cortex adjacent to a well-fixed stem was recorded as “cortical atrophy” (Figure 2). Heterotopic ossification was defined using the classification of Brooker et al. (1973). In 3 hips, the proximal femur was replaced with a tumor prosthesis, so we evaluated the acetabular component only. In 1 hip, all the implants had been removed, so we assessed bone defects only. Leg-length discrepancy (LLD) was assessed by comparing the heights of greater or lesser trochanters relative to the line connecting the teardrops of the acetabulum. If the deformity was severe or if the proximal femur was replaced with a tumor prosthesis, we did not evaluate the patient’s LLD. For analysis radiographs, we used Mdesk Orthopaedics software (RSA Biomedical, Umeå, Sweden).

Figure 2.

Example of cortical atrophy of fixed stem (white arrow).

Clinical score

The 81 patients who consented to be part of this study were invited to an outpatient clinic of 1 author (VH) after 2011. 70 patients (81 hips) came to the clinic, and Harris hip score (HHS) was obtained.

Statistics

Kaplan–Meier survival analysis was used to determine the survival after the primary THR and the first revision surgery. We performed time-trend analyses to assess changes in the revision rate between the periods 1987–1995 and 1996–2010. All calculations were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics.

Ethics

The Regional Ethics Committee for Medical and Health Research deemed that approval was not necessary (2011/1125/REK Vest).

Results

The mean patient age at primary THR was 17 (11–19) years. 8 patients with 9 THRs died after mean 5.3 (0.8–11) years. Among these, 2 patients with 3 hips had juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) and one hip was operated on for acetabular tumor. For the surviving 103 patients (123 hips), the mean follow-up period was 14 (3–26) years.

Pediatric hip diseases accounted for underlying diseases in 54 hips, followed by systemic inflammatory diseases (SIDs) (45 hips), sequelae of trauma (11 hips), and sequelae of infection (7 hips) (Table 3, see Supplementary data).

Primary THRs

We identified 24 different types of acetabular components and 17 different types of femoral stems (Table 4, see Supplementary data). 89% of the acetabular components and 95% of the femoral stems were uncemented implants. Ceramic or metal-on-polyethylene bearings were chosen for 89% of the THRs, and the most common head diameter (69%) was 28 mm (Table 5, see Supplementary data).

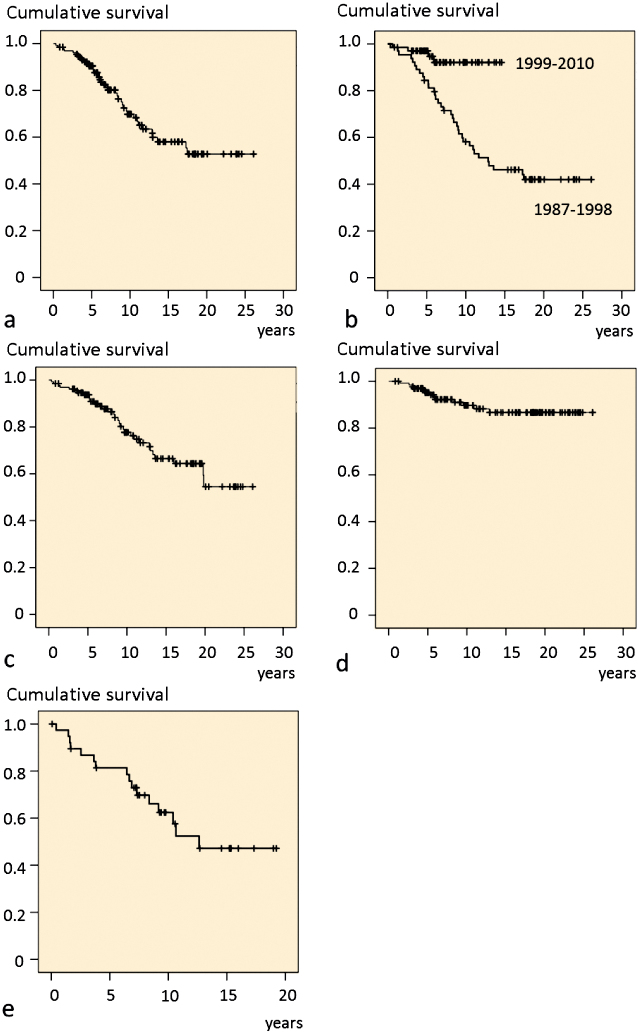

39 hips (30%) had undergone at least 1 revision. 32 acetabular components and 23 stems had been revised. The 10-year survival of the primary implant with the endpoint being any revision was 70%. It was 78% with the endpoint being a change of acetabular component and it was 90% with the endpoint being a change of stem. According to underlying disease, the 10-year survival with the endpoint being any revision was 77% for 45 hips with SID, 52% for 25 hips with developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH), and 73% for 31 hips diagnosed as SCFE, Perthes’ disease, or trauma. The 5-year survival of the THRs carried out in 1987–1998 was 84%, as compared to 97% in 1999–2010 (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Survival curves.

a. Primary THR with revision as endpoint.

b. Primary THR operated during the periods 1987–1998 and 1999–2010.

c. Primary THR with cup change as endpoint.

d. Primary THR with stem change as endpoint.

e. First revision with second revision as endpoint.

Revisions

69 revisions had been reported to the NAR. The greatest number of revisions performed on the same THR was 7. The mean interval between the primary THR and the first revision (n = 39) was 7.2 (0.3–17) years, it was 5.8 (0.4–13) years between the first revision and the second (n = 16), 5.3 (0.1–14) years between the second and the third (n = 7), and 2.2 (0.3–6.1) years between the third and the fourth (n = 3). The survival rate of the 39 first revision at 10 years with a second revision being the endpoint was 62% (Figure 3e). Aseptic loosening and infection accounted for 45% and 12% of the indications for all revisions (Table 2).

Table 2.

Indications for revision

| 1st | 2nd | 3rd | 4th | 5th | 6th | 7th | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infection | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 | ||

| Dislocation | 2 | 1 | 1 | 4 | ||||

| Fracture | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Aseptic loosening | 18 | 9 | 3 | 1 | 31 | |||

| Osteolysis | 3 | 3 | 6 | |||||

| Wear | 11 | 2 | 1 | 14 | ||||

| Pain only | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| 2-stage revision | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Other | 1a | 1b | 1c | 3 | ||||

| Total number | 39 | 16 | 7 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 69 |

Malposition of acetabular component.

Massive ectopic bone formation.

Loose locking ring.

Radiographic results

The last postoperative radiographs were taken at a mean of 12 (2–27) years after the primary THR. 75 (80%) of the primary acetabular components and 86 (91%) of the primary femoral components survived. 1 patient had no implants.

3 acetabular components and 1 femoral stem were found to be loose. Osteolysis and atrophy were observed in 19% and 27% of the acetabulae and 21% and 62% of the femora, respectively. Cortical atrophy was observed in 11 femora (12%) (Table 6, see Supplementary data). The status of bone defects in 2 acetabula and 9 femora was categorized as Paprosky class 3A (Table 7, see Supplementary data). Structural bone grafts or augmentations in the acetabulum were identified in 7 hips. The ectopic ossification was categorized as Brooker grade 0 in 53 hips, as grade 1 in 26, as grade 2 in 9, and as grade 3 in 6. The LLD was measurable in 80 hips and was more than 10 mm in 23 hips (29%) (Table 8, see Supplementary data). 15 hips received at least 1 change of acetabular or femoral component. LLD of more than 10 mm was observed in 9 of these 15 hips, while in 14 of the other 65 hips. The opposite hip of the included 80 THRs was subjected to THR in 36 cases, had no deformity in 41 and had a deformity in 3.

Clinical results

The HHS was evaluated at mean 12 (2–26) years after the primary THR. The mean pain score was 35 (10–44) and the mean total score was 83 (15–100). The mean total score for the 60 hips without any revision was 85, while it was 77 for the 10 hips with one revision and also for the 11 hips with 2 or more revisions. 17 hips had a total score of less than 70.

Discussion

The 10-year survival of primary THR in our patients was 70%, which was worse than the rate of 89% for THRs in patients of all ages reported by the NAR (Lie et al. 2004). Patients with DDH had especially poor survival. These results confirm that THR is still a challenging treatment for children and teenage patients. There have been few reports on THRs in such patients with a mean follow-up period of more than 10 years. Regarding cemented THRs in the 1970s, Cage et al. (1992) observed gross implant loosening in 7 of the 22 cases at a mean follow-up of 11 years and Torchia et al. (1996) reported revision in 27 of 63 THRs and failure (revision or symptomatic loosening) in 29 hips at a mean follow-up of 13 years. Little is known about the long-term outcome of modern THR in very young patients. Bessette et al. (2003) reported the outcome of 15 THRs performed between 1975 and 1990 with a mean follow-up of 14 years; 11 of the 15 were uncemented; 5 hips were revised, and the mean HHS was 65. The THRs in our study were performed after 1987. The overall survival rate was similar to those in previous reports, but it is encouraging that survival had improved in the later period of 11 years. Although our study cohort was too small for us to perform statistical evaluation, we assume that improvements in surgical techniques and implants contributed to this improvement—as well as the introduction of highly cross-linked polyethylene (Digas et al. 2007) and better control of juvenile idiopathic arthritis with biological agents (Gartlehner et al. 2008).

Many different types of implants were used in our patients. We assume that surgeons chose new implants or tried them with good intention rather than using well-documented, representative implants with which they had substantial experience in older patients. New implants are always released with the intention of achieving better outcome; however, not all can succeed, as has been the case with metal-on-metal bearings (Dunbar et al. 2014). In our series, the second (Tropic) and the third (Atoll) most frequently used acetabular components were later shown to have a 3–6 times higher risk of revision when compared with cemented Charnley cups (Havelin et al. 2002). They were used until 2000, and accounted for one-third of the primary components. They may have contributed to the poor survival during the earlier period of 11 years. We recommend that surgeons should not use poorly documented new implants in young patients, for whom long-time outcome matters most.

We observed many revisions in our series. The 10-year survival rate for the first revision was 62%, which was worse than the 10-year survival figure of 77% for the first revision in all ages in the NAR (Lie et al. 2004). Complications led to the need for multiple revisions at short intervals. Our finding is consistent with the report by Bischel et al. (2012) that the number of previous revisions influenced the survival of acetabular cups. Repetitive hospitalization could confer a disadvantage on patients undergoing competitive education and developing their careers. It is therefore important to inform patients about the possibility of needing multiple revisions over a short period.

Reduction of bone stock is a major concern in revision (Deirmengian et al. 2011, Sakellariou and Babis 2014). We observed reduced bone stock around both non-revised and revised implants. The reduction might arise from preoperative deformities. However, regardless of the cause, poor bone stock implies many difficulties in future revisions.

The rate of osteolysis in our study was similar to previously reported rates (8–30%) in young adults (Wangen et al. 2008, Kim et al. 2012). So far, patient age has not been reported as a risk factor in adults aged ≤50 years (Sandgren et al. 2014). We confirmed that being a child or a teenager was not in itself an additional risk regarding osteolysis.

Bone atrophy around components (Mueller et al. 2006, Adolphson et al. 2009) is also a concern for future revisions. We observed a high incidence of atrophy in the proximal femur (62%). Cortical atrophy at the femoral diaphysis was observed in 11 hips (12%). 10 of the cortical atrophy cases occurred around stable and unrevised stems. As far as we understand, cortical atrophy is not common in elderly patients. We speculate that children and teenage patients are more vulnerable to stress shielding than older patients, presumably because of active bone remodeling. We suggest that implants with a high risk of stress shielding (Khanuja et al. 2011) should be avoided in young patients.

LLD was common—especially after revision—and a large leg-length discrepancy was observed irrespective of the status of the opposite hip. LLD can have various causes, such as high positioning of the acetabular component and deep stem insertion. We could not determine the specific cause because most of the radiographs did not cover the whole pelvis, and we could not reasonably assess the height of the center of the acetabulum in patients with various statures. However, we assume that high positioning of the hip center had a substantial effect on LLD because structural bone grafts or acetabular augmentations were identified radiographically in only 7 hips, although the acetabular bone defect was graded Paprosky 2B or more in 15 patients and the diagnosis was DDH in 25 hips (14 of which had complete dislocation). More attention should be paid to restoring the original hip center in children and teenage patients (Schmitz et al. 2013). Centralization of these patients to limited specialized institutions would help to maintain the level of treatment of such rare patients.

The final HHS was favorable despite many revisions and radiographic changes. However, the mean HHS of revised hips was lower than that of non-revised hips. Our patients will definitely require additional revisions in the future. Even the oldest patient was still less than 50 at the end of this study. Deterioration of hip function may occur in middle age.

Continuous observation will be needed.

One limitation of the present study was the small number of patients relative to the degree of heterogeneity. Nevertheless, to date this has been the largest study on modern THR to focus on children and teenage patients (Cage et al. 1992, Torchia et al. 1996, Bessette et al. 2003). Although statistical analysis may be inappropriate, we believe that this study will give surgeons and patients a clinical overview of THR in children and teenagers and help in decision making. Another limitation was the low coverage of patients with bone tumors. THRs performed for tumors are often only reported to another registry: that of the Scandinavian Sarcoma Group (Aksnes et al. 2008). However, such patients do not usually have alternatives to THR. We therefore believe that the main purpose of our study—to help surgeons and patients in decision making for THR—could be accomplished without including tumors.

In summary, we observed many revisions and reduced bone quality, but the clinical score has been favorable so far. We suggest that very young patients should be reminded about the possibility of frequent revisions at short intervals—and that future revisions will be challenging because of their reduced bone stock.

Supplementary data

Tables 3–8, are available on the website of Acta Orthopaedica (www.actaorthop.org), identification number 9820.

MT, SMR, and VH were responsible for the study design. VH measured HHS. MT, SMR, and AMF performed the analysis. MT drafted the manuscript. All the authors participated in interpretation of the results and in preparation of the manuscript.

This study was funded by Sophies Mindre Ortopedi A.S., Norway. The authors declare that there are no competing interests associated with this study.

References

- Adelani M A, Crook K, Barrack R L, Maloney W J, Clohisy J C. What is the prognosis of revision total hip arthroplasty in patients 55 years and younger? Clin Orthop Relat Res 2014; 472(5): 1518–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adolphson P Y, Salemyr M O, Skoldenberg O G, Boden H S. Large femoral bone loss after hip revision using the uncemented proximally porous-coated Bi-Metric prosthesis: 22 hips followed for a mean of 6 years. Acta Orthop 2009; 80(1): 14–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aksnes L H, Bauer H C, Jebsen N L, Folleras G, Allert C, Haugen G S, et al. Limb-sparing surgery preserves more function than amputation: a Scandinavian sarcoma group study of 118 patients. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2008; 90(6): 786–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bessette B J, Fassier F, Tanzer M, Brooks C E. Total hip arthroplasty in patients younger than 21 years: a minimum, 10-year follow-up. Can J Surg 2003; 46(4): 257–62. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bischel O, Seeger J B, Kruger M, Bitsch R G. Multiple acetabular revisions in THA - poor outcome despite maximum effort. Open Orthop J 2012; 6: 488–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooker A F, Bowerman J W, Robinson R A, Riley L H Jr.. Ectopic ossification following total hip replacement. Incidence and a method of classification. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1973; 55(8): 1629–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cage D J, Granberry W M, Tullos H S. Long-term results of total arthroplasty in adolescents with debilitating polyarthropathy. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1992; (283): 156–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claus A M, Engh C A Jr, Sychterz C J, Xenos JS, Orishimo K F, Engh C A Sr.. Radiographic definition of pelvic osteolysis following total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2003; 85-A(8): 1519–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deirmengian G K, Zmistowski B, O’Neil J T, Hozack W J. Management of acetabular bone loss in revision total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2011; 93(19): 1842–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Della Valle C J, Paprosky W G. The femur in revision total hip arthroplasty evaluation and classification. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2004; (420): 55–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Digas G, Karrholm J, Thanner J, Herberts P. 5-year experience of highly cross-linked polyethylene in cemented and uncemented sockets: two randomized studies using radiostereometric analysis. Acta Orthop 2007; 78(6): 746–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunbar M J, Prasad V, Weerts B, Richardson G. Metal-on-metal hip surface replacement: the routine use is not justified. Bone Joint J 2014; 96-B (11 Supple A): 17–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engh C A, Glassman A H, Suthers K E. The case for porous-coated hip implants. The femoral side. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1990; (261): 63–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flugsrud G B, Nordsletten L, Espehaug B, Havelin L I, Meyer H E. The effect of middle-age body weight and physical activity on the risk of early revision hip arthroplasty: a cohort study of 1,535 individuals. Acta Orthop 2007; 78(1): 99–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gartlehner G, Hansen R A, Jonas B L, Thieda P, Lohr K N. Biologics for the treatment of juvenile idiopathic arthritis: a systematic review and critical analysis of the evidence. Clin Rheumatol 2008; 27(1): 67–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havelin L I, Engesaeter L B, Espehaug B, Furnes O, Lie S A, Vollset S E. The Norwegian Arthroplasty Register: 11 years and 73,000 arthroplasties. Acta Orthop Scand 2000; 71(4): 337–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havelin L I, Espehaug B, Engesaeter L B. The performance of two hydroxyapatite-coated acetabular cups compared with Charnley cups. From the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2002; 84(6): 839–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgkinson J P, Shelley P, Wroblewski B M. The correlation between the roentgenographic appearance and operative findings at the bone-cement junction of the socket in Charnley low friction arthroplasties. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1988; (228): 105–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston R C, Fitzgerald R H Jr, Harris W H, Poss R, Muller M E, Sledge C B. Clinical and radiographic evaluation of total hip replacement. A standard system of terminology for reporting results. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1990; 72(2): 161–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khanuja H S, Vakil J J, Goddard M S, Mont M A. Cementless femoral fixation in total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2011; 93(5): 500–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y H, Kim J S, Park J W, Joo J H. Periacetabular osteolysis is the problem in contemporary total hip arthroplasty in young patients. J Arthroplasty 2012; 27(1): 74–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lie S A, Havelin L I, Furnes O N, Engesaeter L B, Vollset S E. Failure rates for 4762 revision total hip arthroplasties in the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2004; 86(4): 504–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller L A, Kress A, Nowak T, Pfander D, Pitto R P, Forst R, et al. Periacetabular bone changes after uncemented total hip arthroplasty evaluated by quantitative computed tomography. Acta Orthop 2006; 77(3): 380–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Münger P, Roder C, Ackermann-Liebrich U, Busato A. Patient-related risk factors leading to aseptic stem loosening in total hip arthroplasty: a case-control study of 5,035 patients. Acta Orthop 2006; 77(4): 567–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paprosky W G, Perona P G, Lawrence J M. Acetabular defect classification and surgical reconstruction in revision arthroplasty. A 6-year follow-up evaluation. J Arthroplasty 1994; 9(1): 33–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakellariou V I, Babis G C. Management bone loss of the proximal femur in revision hip arthroplasty: Update on reconstructive options. World J Orthop 2014; 5(5): 614–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandgren B, Crafoord J, Olivecrona H, Garellick G, Weidenhielm L. Risk factors for periacetabular osteolysis and wear in asymptomatic patients with uncemented total hip arthroplasties. ScientificWorldJournal 2014; 2014: 905818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz M W, Busch V J, Gardeniers J W, Hendriks J C, Veth R P, Schreurs B W. Long-term results of cemented total hip arthroplasty in patients younger than 30 years and the outcome of subsequent revisions. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2013; 14: 37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torchia M E, Klassen R A, Bianco A J. Total hip arthroplasty with cement in patients less than twenty years old. Long-term results. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1996; 78(7): 995–1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wangen H, Lereim P, Holm I, Gunderson R, Reikeras O. Hip arthroplasty in patients younger than 30 years: excellent ten to 16-year follow-up results with a HA-coated stem. Int Orthop 2008; 32(2): 203–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wroblewski B M, Purbach B, Siney P D, Fleming P A. Charnley low-friction arthroplasty in teenage patients: the ultimate challenge. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2010; 92(4): 486–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]