Abstract

Background and purpose

Blood metal ion levels can be an indicator for detecting implant failure in metal-on-metal (MoM) hip arthroplasties. Little is known about the effect of bilateral MoM implants on metal ion levels and patient-reported outcomes. We compared unilateral patients and bilateral patients with either an ASR hip resurfacing (HR) or an ASR XL total hip replacement (THR) and investigated whether cobalt or chromium was associated with a broad spectrum of patient outcomes.

Patients and methods

From a registry of 1,328 patients enrolled in a multicenter prospective follow-up of the ASR Hip System, which was recalled in 2010, we analyzed data from 659 patients (311 HR, 348 THR) who met our inclusion criteria. Cobalt and chromium blood metal ion levels were measured and a 21-item patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) questionnaire was used mean 6 years after index surgery.

Results

Using a minimal threshold of ≥7 ppb, elevated chromium ion levels were found to be associated with worse health-related quality of life (HRQoL) (p < 0.05) and hip function (p < 0.05) in women. These associations were not observed in men. Patients with a unilateral ASR HR had lower levels of cobalt ions than bilateral ASR HR patients (p < 0.001) but similar levels of chromium ions (p = 0.09). Unilateral ASR XL THR patients had lower chromium and cobalt ion levels (p < 0.005) than bilateral ASR XL THR patients.

Interpretation

Chromium ion levels of ≥7 ppb were associated with reduced functional outcomes in female MoM patients.

Since the late 1990s, the popularity of metal-on-metal (MoM) hip implants has risen due to the potential for low volumetric wear and high performance in young and active patients (Bozic et al. 2009). By 2010, however, the use of MoM declined over concerns of adverse local tissue reactions (ALTRs) (Porter et al. 2010). The Articular Surface Replacement (ASR) Hip System, comprised of the ASR hip resurfacing (HR) and the ASR XL total hip replacement (THR), was a MoM system implanted in over 90,000 patients worldwide prior to its recall in 2010 due to higher than expected 5-year revision rates (DePuy Orthopaedics, Warsaw, IN) (Cohen 2011, Bernthal et al. 2012). Recommended protocol for patients with MoM implants includes regular clinical follow-up with physician assessment, blood metal ion testing, plain radiographs, and soft-tissue imaging when necessary (MHRA 2012, Kwon et al. 2014). Metal ion levels may be useful as a method for detection of increased wear and poor hip function in MoM patients (Haddad et al. 2011, Van Der Straeten et al. 2013). Currently, guidelines for metal ion levels only apply to unilateral MoM implants due to the confounding nature of interpreting blood metal ion levels in patients with bilateral MoM hip arthroplasty (Kwon et al. 2014).

The connection between chromium or cobalt and ALTRs is not fully understood. There is neither an established metal ion “safe zone” nor a maximum threshold that can reliably predict implant failure (Langton et al. 2011, Hart et al. 2014). Little has been published on how cobalt and chromium metal ion levels differ between patients with unilateral and bilateral ASR hip systems. Although many studies have investigated the blood metal ion levels in MoM arthroplasty patients, they have been limited by several factors: use of a mixed cohort of different THR and/or HR systems, focusing solely on unilateral implants, or grouping unilateral and bilateral patients together (Maezawa et al. 2010, Hug et al. 2013, Jantzen et al. 2013, Penny et al. 2013, Savarino et al. 2013, Hart et al. 2014, Bisseling et al. 2015). Furthermore, the few studies that have assessed the effect of bilateral implants on blood metal ion levels used relatively small patient cohorts or a variety of HR prostheses (Pelt et al. 2011, Van Der Straeten et al. 2013).

The first purpose of this prospective observational cohort study was to evaluate blood metal ion levels and patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) in patients with ASR HR or ASR XL THR. The second purpose was to assess the effect of bilateral ASR HR or ASR XL THR on blood metal ion levels and PROMs. Finally, we determined whether previously established blood metal ion threshold levels were associated with different PROMs.

Patients and methods

The study population consisted of 1,328 arthroplasty patients enrolled in a multicenter follow-up study of the ASR Hip System (DePuy Orthopaedics, Warsaw, IN). Enrollment of unrevised, primary ASR patients willing to participate in a 6-year follow-up study took place from May 2012 through December 2014. Data abstractors reported anonymized medical record data and PROMs to Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston from 15 centers in 5 countries through a secure, web-based data entry and monitoring system. All the patients enrolled signed the informed consent document and met the following inclusion criteria: any unrevised patient (1) with on-label use of the ASR XL THR or ASR HR system; (2) willing to return for annual follow-up for 5 years; and (3) able to complete a 21-item PROMs questionnaire. The following exclusion criteria were used: any patient (1) who received the ASR XL THR implant as a result of a hip resurfacing conversion or a revision THR; or (2) who had difficulty in comprehending the informed consent form for any reason.

For our analysis, we included all patients with complete data at enrollment using the following criteria: (1) available femoral and acetabular component catalog numbers; (2) valid AP pelvis X-ray to measure cup inclination angle; (3) completed PROMs including the Harris hip score (HHS) (Harris 1969), EQ-5D (EuroQolGroup 1990), UCLA activity score (Amstutz et al. 1984), and VAS pain score (0–10) (Hawker et al. 2011); (4) whole blood cobalt and chromium ion levels. We excluded patients from our analysis if they had: (1) a non-ASR contralateral implant system; or (2) an ASR HR on 1 side and a contralateral ASR XL THR.

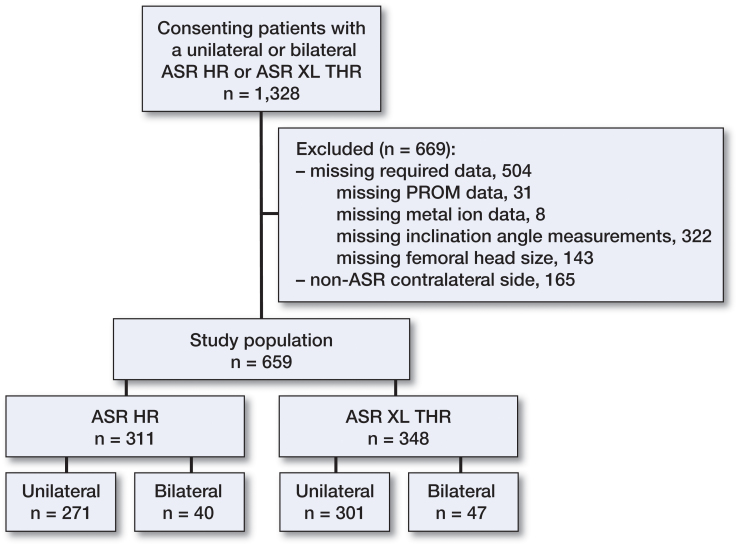

The metal ion concentrations and PROMs were obtained at a mean of 6 (2–11) years from index surgery. Whole blood samples were assessed by certified laboratories using standardized collection methods. The study cohort was divided into 2 groups, ASR HR and ASR XL THR. Each of these groups was further divided into 2 subgroups: patients with unilateral implants and those with bilateral implants (Figure 1). We used 7 ppb and 10 ppb as the metal ion threshold levels described for high-risk patients based on recent MoM follow-up algorithms (MHRA 2012, Kwon et al. 2014).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of patients included in the study population.

Demographics of the patient population

The inclusion criteria gave 659 patients (311 ASR HR, 348 ASR XL THR). The mean age at index surgery was 59 (18–95) years and 246 patients (37%) were female (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic and surgery-related characteristics of the 659 patients who received the MoM ASR Hip System

| ASR HR | ASR XL THR | |

|---|---|---|

| n = 311 | n = 348 | |

| Female, n (%) | 92 (30) | 153 (44) |

| Age at index surgerya | 55 (18–80) | 63 (24–95) |

| Years from index surgery to follow-upa | 6.4 (2.8–10.1) | 5.8 (2.4–8.8) |

| Diagnosis, n (%) | ||

| Idiopathic OA | 276 (89) | 302 (87) |

| Secondary OA | 14 (4.5) | 21 (6.0) |

| Unspecified OA | 20 (6.4) | 24 (6.9) |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) |

| Femoral head size (IQR), mmb | 51 (49–55) | 49 (46–51) |

| Cup inclination angle (IQR), degreesb | 45 (41–49) | 43 (39–48) |

| MARS MRI available, n (%) | 116 (37) | 131 (38) |

Mean (range)

Median (interquartile range).

Statistics

The study questions were analyzed as follows. Differences in blood metal ion levels and PROMs between unilateral and bilateral ASR HR or ASR XL THR patients were assessed using the Mann-Whitney U-test for variables that did not follow a normal distribution and Student’s t-test for normally distributed data. The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to determine the normality of each variable and Levene’s test was used to ensure that the assumption of equal variances was met. The HHS was recorded for each hip. For bilateral patients, we randomly selected a score from 1 hip for statistical analysis. We stratified our cohort into 2 groups (ASR patients and ASR XL patients) and then conducted a series of linear regression analyses. First, we performed analyses to identify which covariates were associated with blood metal ion levels. For this purpose, 2 models were built that assessed cobalt and chromium separately as outcome variables with all available covariates that had previously been associated with metal ion levels: age, gender, time from surgery, bilateral status, femoral head size, and cup inclination angle (< 55° or ≥55°) as exposure variables (Brodner et al. 2004, De Haan et al. 2008). Then, in an effort to determine which covariates were associated with various PROMs, we separately assessed EQ-5D index, HHS, VAS pain score, and UCLA activity score as outcome variables. The same set of exposure variables was used for all of these analyses and included age, sex, bilateral status, and chromium and cobalt with ≥7 ppb and ≥10 ppb binary thresholds.

In order to assess possible non-linearity of age, we set up 4 competing models: a linear model, a model with 1 knot spline, one with 2 knots, and one with 3 knots. The fit of the models was then compared with the help of information criteria. Our data did not indicate a non-linear relationship between age and PROMs, so age was used as a linear term in our analyses.

The p-values, standardized coefficient (expected change in outcome that accompanies 1 unit change in exposure), and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated for all linear regression analyses. Any p-value <0.05 was considered significant. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 19 and R version 3.0.2 (Team 2015).

Ethics and registration

Informed consent was obtained from all patients and the study was approved by the Institutional Review Board or Ethics Committee at all participating centers and Massachusetts General Hospital. The study is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (registration number: NCT01611233).

Results

Patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs)

Patients with a unilateral ASR XL THR reported lower HHS, EQ-5D index, and UCLA scores than unilateral ASR HR patients (p < 0.05) (Table 2). Patients with bilateral ASR XL THR reported lower UCLA activity scores than patients with bilateral ASR HR (p < 0.01) (Table 2). Patients with bilateral ASR XL THR had lower HHS and UCLA activity scores than patients with unilateral ASR XL THR (p < 0.05) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Median (interquartile range) patient-reported outcome measures and blood metal ion levels in patients with an ASR HR or an ASR XL THR prosthesis

| ASR HR |

ASR XL THR |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unilateral | Bilateral | Unilateral | Bilateral | |

| No. of patients | 272 | 40 | 302 | 48 |

| Cobalt ions, ppb | 1.1 (0.6–2.2) | 1.75 (1.1–3.0) | 2.5 (1.2–6.7) | 5.3 (2.5–13) |

| Chromium ions, ppb | 1.2 (0.7–2.0) | 1.85 (1.1–2.5) | 1.4 (0.9–2.6) | 2.4 (1.3–4.1) |

| Ratio Co/Cr | 1.0 (0.7–1.3) | 1.1 (0.9–1.4) | 1.7 (1.2–3.5) | 2.1 (1.2–3.8) |

| Harris hip score | 94 (87–97) | 92 (74–97) | 91 (81–97) | 86 (77–94) |

| EQ-5D | 1.0 (0.8–1.0) | 0.95 (0.7–1.0) | 0.8 (0.7–1.0) | 0.8 (0.6–1.0) |

| UCLA | 7 (6–8) | 6 (6–8) | 6 (5–8) | 5 (4–7) |

| VAS pain | 0.5 (0.0–1.5) | 0.5 (0.0–3.0) | 0.5 (0.0–1.5) | 0.5 (0.0–2.0) |

Linear regression analyses of PROMs using thresholds of 7 ppb for chromium and cobalt

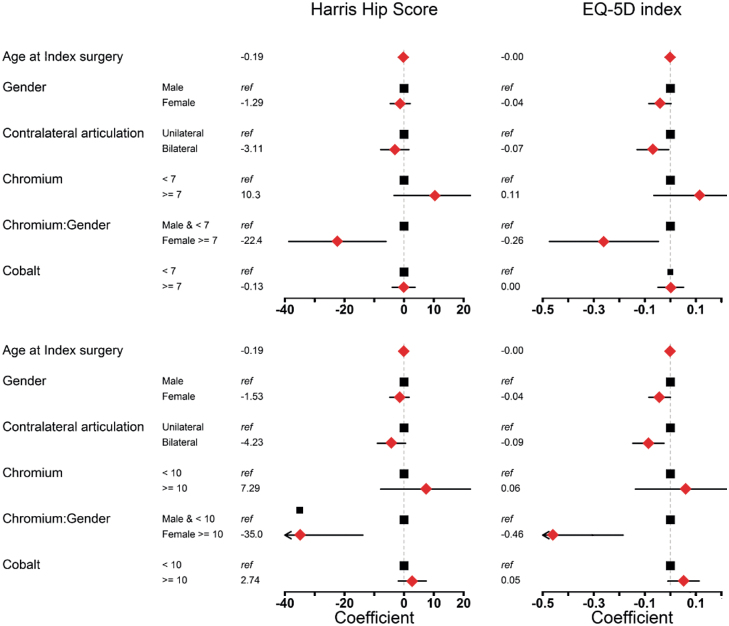

In ASR XL patients, elevated chromium levels of ≥7 ppb in women were associated with lower hip function as measured by the HHS (p < 0.05). Bilateral hip replacements and chromium levels ≥7 ppb in female patients were associated with worse health-related quality of life (HRQoL) as measured by the EQ-5D index (p < 0.05) (Figure 2). Female sex, increasing age, and chromium levels ≥7 ppb in women were associated with lower activity as measured by the UCLA activity score (p < 0.05) (Table 5, see Supplementary data). In ASR patients, no significant associations were observed between cobalt or chromium levels ≥7 ppb and the HHS, UCLA, EQ5D, or VAS pain scores (Tables 7–14, see Supplementary data).

Figure 2.

The effect of ion levels on Harris hip score (HHS) and EQ-5D index adjusted for age, sex, and contralateral articulation. Any variable with a CI that did not include 0 represents a statistically significant influence. Panels A and B correspond to HHS and EQ-5D outcomes with a chromium ion threshold of 7 ppb and panels C and D show the results of the same analysis using a threshold of 10 ppb in ASR XL patients.

Linear regression analyses of PROMs using thresholds of 10 ppb for chromium and cobalt

In ASR XL patients, female patients with chromium levels ≥10 ppb had lower hip function as measured by the HHS (p < 0.05) (Figure 2). Female sex, increasing age, bilateral hip replacement, and chromium levels ≥10 ppb were associated with lower activity as measured by the UCLA activity score (p < 0.05) (Table 6, see Supplementary data). Bilateral hip replacements and chromium levels ≥10 ppb in female patients were associated with worse HRQoL as measured by the EQ-5D index (p < 0.05) (Figure 2). In ASR patients, no statistically significant associations were found between cobalt or chromium levels ≥10 ppb and the HHS, UCLA, EQ5D, or VAS pain scores (Tables 7–14, see Supplementary data).

Differences in metal ion levels between ASR HR and ASR XL THR

Non-parametric univariate analysis showed that the blood metal ion levels of cobalt were higher in patients with unilateral ASR XL THR than in patients with unilateral ASR (p < 0.001), although blood metal ion levels of chromium were similar (p = 0.1) (Table 2). The cobalt to chromium (Co/Cr) ratio was also higher in patients with unilateral ASR XL THR than in patients with unilateral ASR HR (p < 0.001).

The cobalt ion levels were higher in patients with bilateral ASR XL THR than in patients with bilateral ASR HR (p < 0.001), although chromium ion levels were similar (p = 0.1) (Table 2). The Co/Cr ratio was higher for patients with bilateral ASR XL THR than for those with bilateral ASR HR (p < 0.001).

Effect of bilateral ASR HR or ASR XL THR on blood metal ion levels

The cobalt ion levels in blood were higher in patients with bilateral ASR HR implants than in those with a unilateral ASR HR implant (p < 0.05), but chromium ion levels were similar between the groups (p = 0.09) (Table 2). The Co/Cr ratio was higher in patients with bilateral implants than in those with a unilateral implant (p < 0.05).

Cobalt and chromium ion levels in patients with bilateral ASR XL THR implants were higher than in those with a unilateral ASR XL THR implant (p < 0.005), although the groups had similar Co/Cr ratios (p = 0.2) (Table 2).

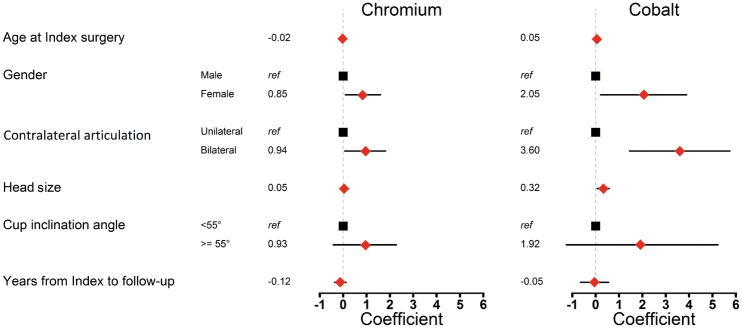

Linear regression analysis of metal ions

In ASR XL patients, female sex and having bilateral hip replacements were associated with higher chromium ion levels (p < 0.01). Both female sex and bilateral hip replacements were also associated with higher cobalt levels (p < 0.01) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

The effect of patient- and implant-related characteristics on the chromium and cobalt levels measured in ASR XL patients. Any variable with a CI that did not include 0 represents a statistically significant influence.

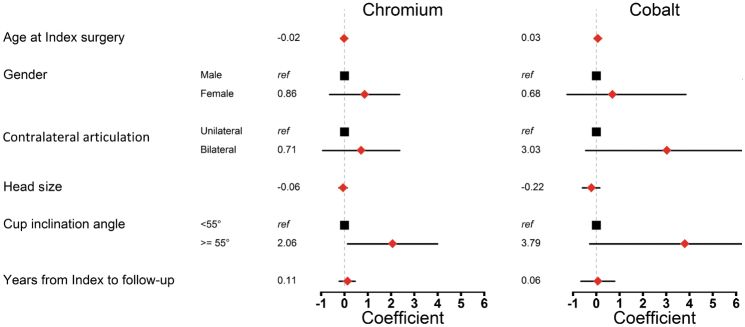

In patients with the ASR hip resurfacing prosthesis, having 1 or 2 (a potential case for patients with bilateral ASR) acetabular cup inclination angle ≥55° was associated with higher chromium metal ion levels (p < 0.01). No variables assessed were found to be associated with higher cobalt metal ion levels (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

The effect of patient- and implant-related characteristics on the chromium and cobalt levels measured in ASR hip resurfacing patients. Any variable with a CI that did not include 0 represents a statistically significant influence.

Discussion

In this multicenter study, we found an association between chromium ion levels and a reduction in both hip function and HRQoL in female patients with unilateral or bilateral ASR XL THR. Interestingly, this association was not observed in male patients. Cobalt ion levels, using both 7 and 10 ppb thresholds, were not associated with hip function or HRQoL. In addition, we found similar chromium ion levels in ASR HR and ASR XL THR patients when comparing unilateral or bilateral groups. Furthermore, we found that patients with unilateral ASR HR had chromium ion levels that were comparable to those in patients with bilateral ASR HR. However, bilateral ASR XL THR implants were associated with higher chromium ion levels than unilateral ASR XL THR implants. Although blood cobalt ion levels were statistically significantly higher in patients with ASR XL THR than in those with ASR HR, and also higher in bilateral groups than in unilateral groups, cobalt ion levels ≥7 ppb or ≥10 ppb were not found to be associated with any negative patient symptoms that were assessed. The lack of association between time from index surgery and blood metal ion levels may in part be explained by a previous study, which demonstrated a lack of temporal variation in blood metal ion levels for patients with ASR HR (Langton et al. 2013). Finally, our study highlights the importance of optimal acetabular cup orientation in order to minimize edge loading and blood metal ion levels.

Cobalt ion levels appeared to deviate more strongly between patients, whereas chromium ion levels showed greater consistency in our study cohort. This observation may have been due to smaller fluctuations in chromium ion levels in whole blood caused by its higher affinity for proteins such as albumin and transferrin, to which it can bind (Newton et al. 2012). Thus, chromium has lower renal excretion than cobalt, which has a high renal clearance (Daniel et al. 2010). High chromium ion levels in blood may be a more consistent indicator of a poorly functioning MoM prosthesis, which would explain its strong association with poor hip function and health-related QoL in our study. Although we found no association between health outcomes and blood cobalt ion levels, cobalt levels >4.5 ppb have been identified as being highly sensitive and specific for abnormal wear in MoM hip arthroplasty, and cobalt blood ion levels as low as 2 ppb may be considered abnormal (Sidaginamale et al. 2013).

In 2014, the American Association of Hip and Knee Surgeons, the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, and the US Hip Society published a consensus statement that outlined criteria for stratifying MoM patients into groups with low, medium, and high risk of failure (Kwon et al. 2014). The algorithm proposed a 10 ppb threshold for identification of patients with a high risk of failure. However, that recommendation acknowledged that metal ion levels were confounded by having more than one cobalt and chromium implant, and that lack of evidence was a limitation for assessment of the risk of metal ion levels in bilateral patients. Our findings support a 7 ppb threshold for blood chromium ions for high-risk female patients in both unilateral MoM and bilateral MoM THR. Our results partially support a previous study which found that bilateral MoM HR patients have elevated blood metal ion levels (Van Der Straeten et al. 2013). However, we found that bilateral MoM HR patients only had elevated blood cobalt ion levels. The HR cohort did not have statistically significantly higher blood levels of chromium ions in bilateral patients. This difference may have been due to the inclusion of multiple HR systems by Van Der Straeten et al., as compared to our concentrating on the ASR HR in this study.

We acknowledge that the present study had some limitations. As a multicenter registry study, we could not evaluate whether patients had additional sources of Cr or Co such as occupational exposure, spinal hardware, or metal dental implants. As we did not have blood metal ion data from patients with staged procedures before and after arthroplasty of the second hip, we were unable to compare the effects of staged and simultaneous arthroplasty procedures on blood metal ion levels over time. Some ASR patients may have been revised before the study; thus, patients with early failures may have been excluded, giving selection bias. The main focus of this study, however, was on understanding the relationship between PROMs and ions in patients currently undergoing follow-up. Furthermore, because not all of the patients in our study cohort underwent a metal artifact reduction sequence (MARS) MRI, we were unable to correlate differences in metal ion levels to severity of ALTRs. In addition, without preoperative PROMs, we could not assess hip function, activity, hip pain, and HRQoL before the index hip arthroplasty, and thus cannot eliminate the possibility of selection bias contributing to some of the associations that were observed. Height and weight were not collected on all patients, so we were unable to assess associations between BMI and metal ion levels and PROMs. It is possible that an overweight patient would have worse HRQoL and higher chromium levels due to implant load. Lastly, we tried to analyze the relationship between current established metal ion thresholds and functional outcomes. Future efforts should be directed at establishing new thresholds.

The study had a number of strengths. First, we focused on a single hip replacement system and compared the HR and THR variants. The multicenter and multinational nature of the study prevented bias that might be introduced from any individual surgeon’s experience. Strict inclusion criteria enabled robust statistical analysis on a broad set of data. The study made use of several PROMs to assess a diverse set of patient symptoms. Finally, this was the first multicenter study to analyze a large cohort of ASR patients that differentiated HR from THR and unilateral from bilateral.

In summary, we found that time from index surgery and patient age were not associated with high blood metal ion levels, which highlights the necessity to have continuous annual follow-up of MoM patients. Blood metal ion testing should be evaluated as part of frequent and comprehensive follow-up that includes a physical examination, plain radiographs, and soft-tissue imaging, if available. Regarding assessment of blood metal ion levels in female patients with MoM hip replacement, chromium ion levels ≥7 ppb appear to be associated with reduced functional outcomes in both unilateral and bilateral patients.

Supplementary data

Tables 4–14 and Appendix are available on the website of Acta Orthopaedica (www.actaorthop.org), identification number 8884.

DKH, RM, GSD, OR, OKM, and HM devised the study and were all responsible for data collection. DKH, RM, GSD, and OR interpreted the data. DKH drafted the paper. DKH, GSD, and OR performed statistical analysis. RM, GSD, OR, OKM, and HM critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. OKM and HM supervised the study. DKH had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analyses.

We thank Szilard Nemes for his critical input as a biostatistical consultant during revision of this manuscript. We also thank clinical research project manager Slav Lerner for his help with the study and Marc Bragdon for technical assistance.

This study was supported by DePuy Orthopaedics, Warsaw, Indiana. The publication of these results was not contingent on the sponsor’s approval. RM received research support from the Orion-Farmos Research Foundation. The authors have no relevant competing interests to disclose.

References

- Amstutz H C, Thomas B J, Jinnah R, Kim W, Grogan T, Yale C. Treatment of primary osteoarthritis of the hip. A comparison of total joint and surface replacement arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1984; 66 (2): 228–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernthal N M, Celestre P C, Stavrakis A I, Ludington J C, Oakes D A. Disappointing short-term results with the DePuy ASR XL metal-on-metal total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2012; 27 (4): 539–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisseling P, Smolders J M, Hol A, van Susante J L. Metal ion levels and functional results following resurfacing hip arthroplasty versus conventional small-diameter metal-on-metal total hip arthroplasty; a 3 to 5year follow-up of a randomized controlled trial. J Arthroplasty 2015; 30 (1): 61–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bozic K J, Kurtz S, Lau E, Ong K, Chiu V, Vail T P, Rubash H E, Berry D J. The epidemiology of bearing surface usage in total hip arthroplasty in the United States. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2009; 91 (7): 1614–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodner W, Grubl A, Jankovsky R, Meisinger V, Lehr S, Gottsauner-Wolf F. Cup inclination and serum concentration of cobalt and chromium after metal-on-metal total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2004; 19 (8 Suppl 3): 66–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen D. Out of joint: the story of the ASR. BMJ 2011; 342: d2905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniel J, Ziaee H, Pradhan C, Pynsent P B, McMinn D J. Renal clearance of cobalt in relation to the use of metal-on-metal bearings in hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2010; 92 (4): 840–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Haan R, Pattyn C, Gill H S, Murray D W, Campbell P A, De Smet K. Correlation between inclination of the acetabular component and metal ion levels in metal-on-metal hip resurfacing replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2008; 90 (10): 1291–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EuroQolGroup. EuroQol–a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy 1990; 16 (3): 199–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haddad F S, Thakrar R R, Hart A J, Skinner J A, Nargol A V, Nolan J F, Gill H S, Murray D W, Blom A W, Case C P. Metal-on-metal bearings: the evidence so far. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2011; 93 (5): 572–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris W H. Traumatic arthritis of the hip after dislocation and acetabular fractures: treatment by mold arthroplasty. An end-result study using a new method of result evaluation. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1969; 51 (4): 737–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart A J, Sabah S A, Sampson B, Skinner J A, Powell J J, Palla L, Pajamaki K J, Puolakka T, Reito A, Eskelinen A. Surveillance of patients with metal-on-metal hip resurfacing and total hip prostheses: a prospective cohort study to investigate the relationship between blood metal ion levels and implant failure. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2014; 96 (13): 1091–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawker G A, Mian S, Kendzerska T, French M. Measures of adult pain: Visual Analog Scale for Pain (VAS Pain), Numeric Rating Scale for Pain (NRS Pain), McGill Pain Questionnaire (MPQ), Short-Form McGill Pain Questionnaire (SF-MPQ), Chronic Pain Grade Scale (CPGS), Short Form-36 Bodily Pain Scale (SF-36 BPS), and Measure of Intermittent and Constant Osteoarthritis Pain (ICOAP). Arthritis Care Res 2011; 63Suppl11: S240–S52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hug K T, Watters T S, Vail T P, Bolognesi M P. The withdrawn ASR THA and hip resurfacing systems: how have our patients fared over 1 to 6 years? Clin Orthop Relat Res 2013; 471 (2): 430–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jantzen C, Jorgensen H L, Duus B R, Sporring S L, Lauritzen J B. Chromium and cobalt ion concentrations in blood and serum following various types of metal-on-metal hip arthroplasties: a literature overview. Acta Orthop 2013; 84 (3): 229–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon Y M, Lombardi A V, Jacobs J J, Fehring T K, Lewis C G, Cabanela M E. Risk stratification algorithm for management of patients with metal-on-metal hip arthroplasty: consensus statement of the American Association of Hip and Knee Surgeons, the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, and the Hip Society. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2014; 96 (1): e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langton D J, Jameson S S, Joyce T J, Gandhi J N, Sidaginamale R, Mereddy P, Lord J, Nargol A V. Accelerating failure rate of the ASR total hip replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2011; 93 (8): 1011–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langton D J, Sidaginamale R P, Joyce T J, Natu S, Blain P, Jefferson R D, Rushton S, Nargol AV. The clinical implications of elevated blood metal ion concentrations in asymptomatic patients with MoM hip resurfacings: a cohort study. BMJ open 2013; 3 (3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maezawa K, Nozawa M, Yuasa T, Aritomi K, Matsuda K, Shitoto K. Seven years of chronological changes of serum chromium levels after Metasul metal-on-metal total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2010; 25 (8): 1196–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MHRA. MHRA Medical Device Alert MDA/2012/036: All metal-on-metal (MoM) hip replacements. MHRA Medical Device Alert MDA/2012/036: All metal-on-metal (MoM) hip replacements. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Pelt C E, Bergeson A G, Anderson L A, Stoddard G J, Peters C L. Serum metal ion concentrations after unilateral vs bilateral large-head metal-on-metal primary total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2011; 26 (8): 1494–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penny J O, Varmarken J E, Ovesen O, Nielsen C, Overgaard S. Metal ion levels and lymphocyte counts: ASR hip resurfacing prosthesis vs. standard THA: 2-year results from a randomized study. Acta Orthop 2013; 84 (2): 130–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter M, Borroff M, Gregg P, Howard P, MacGregor A, Tucker K. National Joint Registry for England and Wales. 7th annual report 2010. Surgical data to December 2009. 2010; 7. [Google Scholar]

- Savarino L, Cadossi M, Chiarello E, Baldini N, Giannini S. Do ion levels in metal-on-metal hip resurfacing differ from those in metal-on-metal THA at long-term followup? Clin Orthop Relat Res 2013; 471 (9): 2964–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidaginamale R P, Joyce T J, Lord J K, Jefferson R, Blain P G, Nargol A V, Langton D J. Blood metal ion testing is an effectivescreening tool to identify poorly performing metal-on-metal bearingsurfaces. Bone Joint Res 2013; 2 (5): 84–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Team R C. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Van Der Straeten C, Grammatopoulos G, Gill H S, Calistri A, Campbell P, De Smet K A. The 2012 Otto Aufranc Award: The interpretation of metal ion levels in unilateral and bilateral hip resurfacing. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2013; 471 (2): 377–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]