Abstract

Background and purpose

The outcome of surgical treatment of lumbar disc herniation (LDH) has been thoroughly evaluated in middle-aged patients, but less so in elderly patients.

Patients and methods

With validated patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) and using SweSpine (the national Swedish Spine Surgery Register), we analyzed the preoperative clinical status of LDH patients and the 1-year postoperative outcome of LDH surgery performed over the period 2000–2012. We included 1,250 elderly patients (≥ 65 years of age) and 12,840 young and middle-aged patients (aged 20–64).

Results

Generally speaking, elderly patients were referred for LDH surgery with worse PROM scores than young and middle-aged patients, they improved less by surgery, they experienced more complications, they had inferior 1-year postoperative PROM scores, and they were less satisfied with the outcome (with all differences being statistically significant).

Interpretation

Elderly patients appear to have a worse postoperative outcome after LDH surgery than young and middle-aged patients, they are referred to surgery with inferior clinical status, and they improve less after the surgery.

Studies of surgical treatment of lumbar disc herniation (LDH) are predominantly reported using cohorts with a median age of 40–45 years, which is not surprising since LDH most often affects individuals in their early 40s (Frymoyer 1992). After this age, the incidence diminishes (Ma et al. 2013). The few studies that have been conducted in old patients have generally found a satisfactory outcome (Matuda et al. 1962, Barr and Riseborough 1963, An et al. 1990, Buckwalter 1995, Jonsson and Stromqvist 1995, Di Silvestre et al. 2001, Dammers and Koehler 2002, Werndle et al. 2012, Perez-Prieto et al. 2014).

The proportion of elderly patients, defined according to the WHO as individuals aged 65 years or more, is increasing (Vaupel and v. Kistowski 2005). In the nationwide Swedish surgical spine register (SweSpine), the proportion of surgical procedures due to LDH in the elderly has increased from 6% in 2000 to 9% in 2010 (unpublished data). The same trend has been reported in Japan, where LDH surgery in the elderly has increased from 0.7% in 1962 (Matuda et al. 1962) to 11% in 1999 (Gembun et al. 2001), and also in Italy (Di Silvestre et al. 2001).

Does LDH surgery in the elderly achieve the same favorable outcome as in younger adults? There have been very few comparative studies, and most of these have suggested a worse outcome in elderly patients than in younger ones (Matuda et al. 1962, Barr and Riseborough 1963, An et al. 1990, Jonsson and Stromqvist 1994, Di Silvestre et al. 2001, Werndle et al. 2012, Perez-Prieto et al. 2014). These inferences are based on retrospective or small prospective studies, and the idea is the subject of debate. There have been no prospective studies comparing the outcome in a large cohort of elderly patients with that in younger adults using validated patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs). We retrospectively analyzed data that had been collected prospectively, hypothesizing that the surgical outcome would be worse in elderly patients than in young and middle-aged patients.

Patients and methods

The national Swedish Spine Surgery Register (SweSpine) is validated and covers approximately 90% of all departments that conduct spine surgery in Sweden (Stromqvist et al. 2001, Stromqvist 2002, Stromqvist et al. 2009). Participation is voluntary, and patients who are included in the register must first have accepted that their data can be used for research. The patients report the demographics, the preoperative clinical status, and the postoperative 1-, 2-, 5-, and 10-year clinical status through PROMs. The surgeon reports the peroperative data.

The SweSpine protocol includes data on age, sex, smoking habits, duration of back and leg pain, consumption of analgesics, estimated walking distance, level of pain in the back and legs according to a visual analog scale (VAS), quality of life by SF-36 and EuroQol 5 dimensions (EQ5D), disability by Oswestry disability index (ODI), diagnosis, type of operation, level operated, side operated, and complications. At the 1-year postoperative follow-up, the subjective satisfaction with the surgical outcome is rated on a 3-dimensional Likert scale (dissatisfied, indeterminate, satisfied). For this study, we analyzed satisfaction rate as a dichotomous variable (satisfied/indeterminate vs. dissatisfied). We defined major complications as accidental nerve root injury, cauda equina syndrome, pulmonary embolism, or perioperative mortality and minor complications as incidental durotomy, urinary tract infection, postoperative urinary retention, and wound hematoma or infection.

In the register, we identified 1,668 patients aged ≥65 years (defined as “elderly”) who between 2000–2012 had undergone open discectomy with or without microscopic assistance due to LDH. 418 patients with incomplete 1-year postoperative data were excluded, leaving 1,250 elderly patients for this study. In order to compare the outcome in these patients with the outcome in young and middle-aged adults, we also identified 18,113 patients aged 20–64 years (defined as “young and middle-aged”) who had the same treatment for LDH during the same time period. 5,273 patients with incomplete 1-year postoperative data were excluded, leaving 12,840 young and middle-aged patients in the control cohort. Dropout analysis is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Dropout analysis comparing elderly and younger patients with complete and missing postoperative data in SweSpine regarding age, gender, level operated, VAS as an estimation of back and leg pain, SF-36 as an estimation of quality of life, and ODI as an estimation of disability. Elderly is defined as those aged ≥65 years, and younger refers to the sex-matched comparison group aged 20–64

| Elderly |

Younger |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Included | Lost to 1 year | p-value | Included | Lost to 1 year | p-value | |

| n = 1,250 | n = 418 | n = 12,840 | n = 5,273 | |||

| Age, mean (SD) | 71 (5.2) | 73 (6.7) | < 0.001 | 43 (10) | 41 (10) | < 0.001 |

| Men/women, % | 53/47 | 42/58 | < 0.001 | 55/45 | 60/40 | < 0.001 |

| Operated level | ||||||

| L4–L5, % | 53 | 53 | 0.2 | 41 | 41 | 0.2 |

| L5–S1, % | 20 | 22 | 53 | 53 | ||

| VAS back paina | 53 (51–55) | 55 (52–59) | 0.2 | 46 (46–47) | 48 (47–49) | 0.02 |

| VAS leg paina | 69 (67–70) | 65 (62–68) | 0.03 | 66 (66–67) | 66 (65–66) | 0.4 |

| SF-36 PCSa | 37 (36–38) | 35 (33–36) | 0.008 | 37 (36–37) | 35 (35–36) | < 0.001 |

| SF-36 MCSa | 28 (28–29) | 28 (27–29) | 0.4 | 31 (31–32) | 31 (30–31) | < 0.001 |

| ODI-indexa | 50 (49–51) | 51 (49–53) | 0.5 | 48 (48–49) | 49 (48–49) | 0.2 |

mean (95% CI)

Statistics

IBM SPSS Statistics version 22 was used for the statistical calculations. Descriptive data are presented as numbers, means (with SD), or proportions (i.e. percentages). Pain by VAS, quality of life by SF-36 and EuroQol, and also disability by ODI are presented as means with 95% confidence interval (CI). Group comparisons were done with chi-squared test, and Student’s t-test was used for comparisons between means. Any p-values <0.05 were regarded as being statistically significant.

Results

Preoperative data

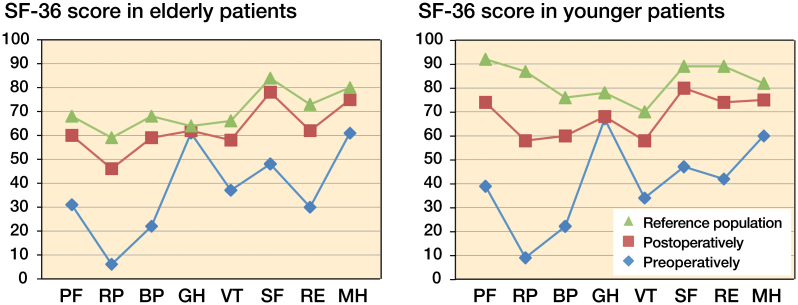

53% of the elderly patients were males, with a mean age of 71 (SD 5.3) years, and the 47% who were women had a mean age of 72 (SD 5.5) years. 55% of the the young and middle-aged patients were males, with a mean age of 43 (SD 10.3) years, and the 45% who were women had a mean age of 43 (SD 10.2) years. Further background data are presented in Tables 2 and 3. In addition to discectomy, 19% of the elderly cohort and 12% of the younger cohort also had decompressive surgery. Elderly patients had more pronounced back and leg pain, shorter walking distance, inferior quality of life (SF-36) (Figure 1), and a higher degree of disability (ODI) (Tables 2 and 3) than young and middle-aged patients, and—in all age groups—with severe impairment in all PROMs compared to normative age-matched data (Fairbank et al. 1980, Sullivan et al. 1994, Fairbank and Pynsent 2000) (Tables 2 and 3, and Figure 1).

Table 2.

Preoperative and 1-year postoperative data regarding age, smoking, duration of back and leg pain, consumption of analgesics, and estimated walking distances. Elderly is defined as those aged ≥65 years, and younger refers to the sex-matched comparison group aged 20–64

| Preoperatively |

Postoperatively |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Elderly | Younger | p-value | Elderly | Younger | p-value | |

| Age, mean (SD) | 71 (5) | 43 (10) | ||||

| Sex (M/F), % | 53/47 | 55/45 | 0.2 | |||

| Smoking, % | 11 | 21 | < 0.001 | NA | NA | NA |

| Months of back pain, % | 0.1 | NA | NA | NA | ||

| Had no back pain | 6 | 6 | ||||

| > 3–12 | 43 | 46 | ||||

| > 12–24 | 16 | 16 | ||||

| > 24 | 22 | 19 | ||||

| Months of leg pain, % | 0.004 | NA | NA | NA | ||

| Had no leg pain | 1 | 1 | ||||

| ≤ 3 | 16 | 18 | ||||

| > 3–12 | 49 | 53 | ||||

| > 12–24 | 18 | 15 | ||||

| > 24 | 16 | 13 | ||||

| Analgesics, % | 0.4 | < 0.001 | ||||

| None | 11 | 12 | 45 | 51 | ||

| Intermittent | 28 | 29 | 33 | 32 | ||

| Regular | 62 | 60 | 22 | 17 | ||

| Walking distance, % | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||||

| ≤ 100 m | 48 | 32 | 13 | 4 | ||

| > 100–500 m | 25 | 21 | 18 | 8 | ||

| > 500–1,000 m | 12 | 16 | 16 | 11 | ||

| > 1,000 m | 15 | 31 | 53 | 77 | ||

NA: not applicable.

Table 3.

Preoperative and 1-year postoperative data regarding VAS as an estimation of back and leg pain, EuroQol and SF-36 as estimations of quality of life, and ODI as an estimation of disability. Data are mean (95% CI). Elderly is defined as those aged ≥65 years, and younger refers to the sex-matched comparison group aged 20–64

| Preoperatively |

Postoperatively |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Elderly | Younger | p-value | Elderly | Younger | p-value | |

| VAS back pain | 53 (51–55) | 46 (45–47) | < 0.001 | 27 (26–29) | 25 (25–26) | 0.03 |

| VAS leg pain | 69 (67–70) | 66 (66–67) | 0.003 | 30 (28–32) | 22 (21–22) | < 0.001 |

| EuroQol-index | 0.29 (0.27–0.31) | 0.26 (0.25–0.27) | 0.02 | 0.69 (0.68–0.71) | 0.70 (0.70–0.71) | 0.4 |

| EuroQol-VAS | 47 (46–49) | 45 (44–45) | 0.006 | 68 (67–69) | 71 (70–71) | < 0.001 |

| SF-36 | ||||||

| PF | 31 (30–33) | 39 (38–39) | < 0.001 | 60 (58–61) | 74 (74–74) | < 0.001 |

| RP | 6 (5–7) | 9 (8–9) | < 0.001 | 46 (43–48) | 58 (58–59) | < 0.001 |

| BP | 22 (21–23) | 22 (22–22) | 0.5 | 58 (57–60) | 60 (60–61) | 0.02 |

| GH | 61 (60–62) | 67 (67–67) | < 0.001 | 62 (61–64) | 68 (68–68) | < 0.001 |

| VT | 37 (36–38) | 34 (33–34) | < 0.001 | 59 (57–60) | 57 (57–58) | 0.2 |

| SF | 48 (46–49) | 47 (46–48) | 0.6 | 78 (76–79) | 80 (79–80) | 0.02 |

| RE | 30 (27–32) | 42 (41–43) | < 0.001 | 62 (60–65) | 74 (73–75) | < 0.001 |

| MH | 61 (59–62) | 60 (59–60) | 0.1 | 75 (74–76) | 75 (74–75) | 0.6 |

| PCS | 37 (36–38) | 36 (36–37) | 0.3 | 46 (45–46) | 46 (46–46) | 0.2 |

| MCS | 28 (28–29) | 31 (31–32) | < 0.001 | 40 (39–40) | 44 (44–44) | < 0.001 |

| ODI | 50 (49–51) | 49 (48–49) | 0.005 | 24 (22–25) | 20 (20–20) | < 0.001 |

SF-36 scales: PF – physical functioning, RP – physical role functioning, BP – bodily pain, GH – general health perceptions, VT – vitality, SF – social role functioning, EM – emotional role functioning, MH – mental health, PCS – physical component summary, and MCS – mental component summary.

ODI: Oswestry disability index

Figure 1.

Quality of life estimated by SF-36, pre- and postoperatively, in elderly and younger patients operated for LDH compared to a published age-matched reference data population* (Sullivan et al. 1994). Elderly is defi ned as those aged ≥65 years, and younger refers to the sex-matched comparison group aged 20–64. For Abbreviations, see Table 3.

Peroperative data

Elderly patients were operated at the L5–S1 level in 20% of the cases, at the L4–L5 level in 53%, at the L3–L4 level in 20%, at the L2–L3 level in 6%, and at the L1-L2 level in 1% whereas the corresponding proportions in young and middle-aged patients were 53%, 41%, 4%, 1%, and 0.1% (p < 0.001). Elderly patients developed complications in 7.5% of cases and young and middle-aged patients developed complications in 5% of cases (p < 0.001). Elderly patients had serious complications in 0.7% of the cases and young and middle-aged patients in 0.4% of cases (p = 0.005). When we analyzed each of the serious complications separately, no statistically significant group differences were found. Elderly patients had minor complications in 6.4% of the cases and young and middle-aged patients had minor complications in 3.1% of cases (p < 0.001), with elderly patients more often developing incidental durotomies (p < 0.001) and urinary tract infections (p = 0.009). The single most common complication was incidental durotomy. In the elderly, it was found in 5.2% of the operations and in the younger and middle-aged patients it was found in 2.6% of the operations (p < 0.001). Unusual complications in elderly patients included aspiration pneumonia (n = 1), raccoon eyes and temporary sight disturbance (n = 1), ischemic stroke (n = 1), renal failure (n = 1), and postoperative sepsis (n = 3). Unusual complications in young and middle-aged patients included pneumonia (n = 1) and postoperative sepsis (n = 1).

Postoperative data

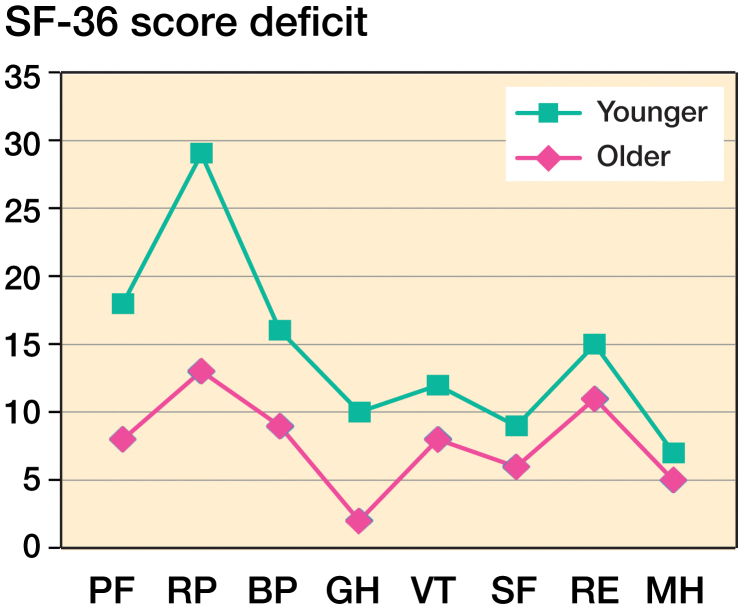

1 year after surgery, the elderly patients generally had more pronounced leg pain, higher consumption of analgesics, shorter walking distance, inferior quality of life (SF-36) (Figure 1), and a higher degree of disability (ODI) than young and middle-aged patients (Tables 2 and 3). The PROM values improved markedly in all patient groups (Figure 1), but in general with less improvement in the elderly patients than in the young and middle-aged patients (Table 4). The exceptions were for the SF-36 subdomains RE (Role emotional), MH (Mental health) and GH (General health), where there were no statistically significant group differences, and for back pain, where elderly patients improved more (Table 4). However, in spite of the improvement both groups still reported impaired clinical status compared to normative age-matched data (Figure 1), with a more pronounced deficit in the elderly (Figure 2). Also, 1 year postoperatively, elderly patients were subjectively less satisfied with the surgical outcome than young and middle-aged patients (p = 0.04) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Improvements from preoperatively to 1-year postoperatively in VAS as an estimation of back and leg pain, EuroQol and SF-36 as estimations of quality of life, and ODI as an estimation of disability. Data are mean (95% CI) or percentages. Elderly is defined as those aged ≥65 years, and younger refers to the sex-matched comparison group aged 20–64

| Improvement by surgery |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Elderly | Younger | p-value | |

| VAS back pain | 27 (25–29) | 22 (21–23) | 0.003 |

| VAS leg pain | 40 (38–42) | 45 (44–46) | < 0.001 |

| EuroQol-index | 0.42 (0.40–0.45) | 0.45 (0.44–0.46) | < 0.05 |

| EuroQol-VAS | 22 (20–24) | 26 (26–27) | < 0.001 |

| SF-36 | |||

| PF | 29 (27–31) | 36 (36–37) | < 0.001 |

| RP | 42 (39–45) | 51 (50–52) | < 0.001 |

| BP | 37 (35–39) | 39 (38–40) | 0.03 |

| GH | 2 (0–3) | 2 (1–2) | 0.8 |

| VT | 22 (20–24) | 25 (24–25) | 0.008 |

| SF | 31 (29–33) | 34 (33–34) | 0.02 |

| RE | 33 (30–37) | 33 (32–34) | 0.7 |

| MH | 15 (14–16) | 16 (15–16) | 0.3 |

| PCS | 9 (8–10) | 10 (10–10) | 0.03 |

| MCS | 12 (11–12) | 13 (13–13) | 0.004 |

| ODI | 28 (26–29) | 29 (29–29) | 0.1 |

| Satisfaction, % | 0.04 | ||

| Satisfied/indeterminate | 91 | 92 | |

| Dissatisfied | 9.3 | 7.6 | |

For Abbreviations, see Table 3.

Figure 2.

1-year postoperative estimated point defi cit in quality of life estimated by SF-36, in elderly and younger patients operated for LDH compared to a published age-matched reference data population (Sullivan et al. 1994). Elderly is defi ned as patients aged ≥65 years of age, and younger refers to the sex-matched comparison group aged 20–64. For Abbreviations, see Table 3.

Discussion

We found that elderly patients with LDH are referred for surgery with a markedly worse quality of life and with worse clinical status than young and middle-aged patients. Surgery also led to less improvement in the elderly patients than in the young and middle-aged patients. It must, however, be emphasized that both groups met the criteria for a successful outcome after LDH surgery (Solberg et al. 2013) even though neither group reached normative age- and sex-matched values for quality of life. Our study also supports the notion that the elderly are more often operated for cranially located lumbar segments than young and middle-aged adults (Dammers and Koehler 2002, Werndle et al. 2012), and that elderly patients have more complications than young and middle-aged patients. However, even if differences at the group level are found, indicating inferior outcome in elderly patients than in younger ones, these differences and the clinical impact of them on any particular individual could be debated.

We found that elderly patients were referred for LDH surgery with worse clinical status than age- and sex-matched healthy individuals, and also with worse clinical status than young and middle-aged adult patients who were referred for LDH surgery. The reasons are unclear, but one can speculate that both the surgeon and the patient would be more restricted in choosing a surgical procedure due to the generally higher risk of complications in elderly patients.

Our results also support the notion that complications are more common in elderly patients than in young and middle-aged patients. This is a general finding in lumbar surgery (Deyo et al. 1992, Carreon et al. 2003, Daubs et al. 2007), but also in LDH surgery (An et al. 1990) where elderly patients have been reported to have a higher risk of urinary tract infections and cardiovascular complications—but not surgically related complications (Sobottke et al. 2012). Our data contradict this view, since we found complications including durotomy to be more frequent in elderly patients than in young and middle-aged patients, which is similar to what has been reported in other studies (Di Silvestre et al. 2001, Stromqvist et al. 2010, 2012). Incidental durotomy, however, does not appear to affect the outcome of LDH surgery (Stromqvist et al. 2010), as supported by the high rate of patient satisfaction in the present study. It is also of interest to note that the complication rate in our cohort, where less experienced surgeons and clinics performing few spine operations were also included, was not particularly higher than in reports from spine-specialized units (Maistrelli et al. 1987, Di Silvestre et al. 2001). That is, our data indicate that LDH surgery could also be performed in unspecialized spine units and in elderly patients with few complications.

The outcome data from LDH surgery in elderly patients are conflicting. The largest published study found good outcome in 78 elderly patients (Di Silvestre et al. 2001), but this study used a retrospective design without validated PROMs. A retrospective evaluation found similar improvement in 12 individuals above the age of 65 and in 25 individuals below this age, using the Japanese Orthopedic Association (JOA) score (Fujii et al. 2003). In contrast, other studies have found that 20–30% of elderly patients with LDH surgery experience persistent back pain after surgery (Maistrelli et al. 1987, Di Silvestre et al. 2001). Our study shows that elderly patients have a worse clinical outcome than young and middle-aged patients, since elderly patients are referred for surgery with more severe clinical problems and they have less improvement than young and middle-aged adult patients. But even so, we must emphasize that in the literature, the criteria reported for successful outcome of LDH surgery were also met in the elderly (Solberg et al. 2013). We therefore speculate that the PROM outcome value and the subjective satisfaction rate may be influenced by the fact that elderly patients accept a worse health status than young and middle-aged patients, as supported by results showing that normative data also show inferior scores in the elderly (Sullivan et al. 1994, Solberg et al. 2013). The finding that the absolute postoperative PROM scores were higher in younger patients than in elderly patients (Figure 1)—but that the relative deficit compared to age- and sex-matched individuals is higher in young patients than in elderly patients (Figure 2)—indicate that both the absolute difference and the relative difference in PROM scores may be of importance for the subjective estimation.

Why elderly patients have less improvement postoperatively than children, adolescents ((Sullivan et al. 1994, Stromqvist et al. 2013), and young adults (Peul et al. 2007) is unknown. Animal models have shown that the inflammatory response in LDH and the potential for neurological recovery decreases with increasing age (Hasegawa et al. 2000). The anatomic location could possibly also influence the outcome, in that the herniation in young patients is most often localized to the 2 inferior lumbar segments whereas we and others (An et al. 1990, Dammers and Koehler 2002) have shown that the herniation in elderly patients affects more cranially located segments to a greater degree. Another reason might be that in 80% of patients aged 70 or more, the herniated tissue is composed of annulus fibrosus with or without part of the end plate (Harada and Nakahara 1989, Tanaka et al. 1993) as a result of more advanced degenerative disease (Gembun et al. 2001), while the herniated tissue in young patients includes the gelatinous and hydrated nucleus pulposus (Shillito 1996, Kumar et al. 2007). Finally, age-related factors other than these specific biological factors might also influence the outcome.

The strengths of this registry-based study include the prospective design, the large study population, the inclusion of nationwide data without exclusion criteria, and a design that reflects the actual situation in the healthcare system and not only in highly specialized units. The use of validated PROMs makes comparison of different studies and comparison with other treatments possible. The limitations include the incomplete postoperative data collection (with the risk of selection bias, as addressed in our dropout analysis). It would also have been advantageous to be able to specifically compare the outcome in general departments and in specialized spine units; when surgery was performed by surgeons under training, by general orthopedic surgeons, and by specialized spine surgeons; in LDH surgery using different surgical techniques; in groups with different radiographic appearance; and in non-operatively treated patients. We speculate, for example, that elderly LDH patients could have an additional spinal stenosis to a greater degree than younger patients. However, any major influence of spinal stenosis on the patients in our cohort is argued against by the fact that patients with LDH have more leg pain and a higher degree of disability (ODI) than patients with lumbar spinal stenosis, with preoperative data almost identical to our data (Rainville and Lopez 2013). It would have been advantageous to analyze existing comorbidities, as these are probably more commonly found in elderly patients and are a possible reason for elderly patients having inferior PROM scores. It would also have been advantageous to have clinical examination data available, since leg and back pain in elderly patients may even—with disc herniation—also be associated with other diagnoses such as spinal stenosis and insufficient arterial circulation, which might explain the inferior PROM outcome in elderly patients.

In summary, in comparison to young and middle-aged adults, elderly patients are to a larger degree referred for LDH surgery with more severe preoperative symptoms, they improve less after surgery, and they have an inferior postoperative outcome. However, since LDH surgery in elderly patients in general fulfills defined criteria for a successful outcome of the procedure, surgery should continue to be one treatment option for LDH in the elderly.

FS: design of the study, analysis and interpretation of data, and writing of the manuscript. BS and BJ: design of the study, interpretation of data, and revision of the manuscript. MK: design of the study, analysis and interpretation of data, and preparation of the manuscript.

References

- An H S, Vaccaro A, Simeone F A, Balderston R A, O’Neill D. Herniated lumbar disc in patients over the age of fifty. J Spinal Disord 1990; 3 (2): 143–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barr J S, Riseborough E J. Treatment of low back and sciatic pain in patients over 60 years of age. A study of 100 patients. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1963; 26: 12–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckwalter J A. Aging and degeneration of the human intervertebral disc. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1995; 20 (11): 1307–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carreon L Y, Puno R M, Dimar J R 2nd, Glassman S D, Johnson J R. Perioperative complications of posterior lumbar decompression and arthrodesis in older adults. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2003; 85-A (11): 2089–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dammers R, Koehler P J. Lumbar disc herniation: level increases with age. Surg Neurol 2002; 58 (3-4): 209–12; discussion 12-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daubs M D, Lenke L G, Cheh G, Stobbs G, Bridwell K H. Adult spinal deformity surgery: complications and outcomes in patients over age 60. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2007; 32 (20): 2238–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deyo R A, Cherkin D C, Loeser J D, Bigos S J, Ciol M A. Morbidity and mortality in association with operations on the lumbar spine. The influence of age, diagnosis, and procedure. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1992; 74 (4): 536–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Silvestre M, Greggi T, Rulli E, Paderni S, Palumbi P, Parisini P. Lumbar disc herniation in the elderly patient. Chir Organi Mov 2001; 86 (3): 223–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairbank J C, Pynsent P B. The Oswestry Disability Index. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2000; 25 (22): 2940–52; discussion 52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairbank J C, Couper J, Davies J B, O’Brien J P. The Oswestry low back pain disability questionnaire. Physiotherapy 1980; 66 (8): 271–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frymoyer J W. Lumbar disk disease: epidemiology. Instr Course Lect 1992; 41: 217–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujii K, Henmi T, Kanematsu Y, Mishiro T, Sakai T. Surgical treatment of lumbar disc herniation in elderly patients. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2003; 85 (8): 1146–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gembun Y, Nakayama Y, Shirai Y, Miyamoto M, Kitagawa Y, Yamada T. Surgical results of lumbar disc herniation in the elderly. J Nippon Med Sch 2001; 68 (1): 50–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harada Y, Nakahara S. A pathologic study of lumbar disc herniation in the elderly. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1989; 14 (9): 1020–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasegawa T, An H S, Inufusa A, Mikawa Y, Watanabe R. The effect of age on inflammatory responses and nerve root injuries after lumbar disc herniation: an experimental study in a canine model. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2000; 25 (8): 937–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonsson B, Stromqvist B. Lumbar spine surgery in the elderly. Complications and surgical results. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1994; 19 (13): 1431–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonsson B, Stromqvist B. Influence of age on symptoms and signs in lumbar disc herniation. Eur Spine J 1995; 4 (4): 202–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar R, Kumar V, Das N K, Behari S, Mahapatra A K. Adolescent lumbar disc disease: findings and outcome. Childs Nerv Syst 2007; 23 (11): 1295–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma D, Liang Y, Wang D, Liu Z, Zhang W, Ma T, et al. Trend of the incidence of lumbar disc herniation: decreasing with aging in the elderly. Clin Interv Aging 2013; 8: 1047–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maistrelli G L, Vaughan P A, Evans D C, Barrington T W. Lumbar disc herniation in the elderly. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1987; 12 (1): 63–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matuda K Y S, Suezawa N, Yonezawa H, Shubata T. Clinical results of lumbar disc herniation. Seikeigeka 1962; 13: 589–95. [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Prieto D, Lozano-Alvarez C, Salo G, Molina A, Llado A, Puig-Verdie L, et al. Should age be a contraindication for degenerative lumbar surgery? Eur Spine J 2014; 23 (5): 1007–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peul W C, van Houwelingen H C, van den Hout W B, Brand R, Eekhof J A, Tans J T, et al. Surgery versus prolonged conservative treatment for sciatica. N Engl J Med 2007; 356 (22): 2245–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rainville J, Lopez E. Comparison of radicular symptoms caused by lumbar disc herniation and lumbar spinal stenosis in the elderly. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2013; 38 (15): 1282–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shillito J., Jr. Pediatric lumbar disc surgery: 20 patients under 15 years of age. Surg Neurol 1996; 46 (1): 14–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobottke R, Aghayev E, Roder C, Eysel P, Delank S K, Zweig T. Predictors of surgical, general and follow-up complications in lumbar spinal stenosis relative to patient age as emerged from the Spine Tango Registry. Eur Spine J 2012; 21 (3): 411–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solberg T, Johnsen L G, Nygaard O P, Grotle M. Can we define success criteria for lumbar disc surgery?: estimates for a substantial amount of improvement in core outcome measures. Acta Orthop 2013; 84 (2): 196–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stromqvist B. Evidence-based lumbar spine surgery. The role of national registration. Acta Orthop Scand Suppl 2002; 73 (305): 34–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stromqvist B, Jonsson B, Fritzell P, Hagg O, Larsson B E, Lind B. The Swedish National Register for lumbar spine surgery: Swedish Society for Spinal Surgery. Acta Orthop Scand 2001; 72 (2): 99–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stromqvist B, Fritzell P, Hagg O, Jonsson B, Swedish Society of Spinal S. The Swedish Spine Register: development, design and utility. Eur Spine J 2009; 18Suppl3: 294–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stromqvist F, Jonsson B, Stromqvist B, Swedish Society of Spinal S. . Dural lesions in lumbar disc herniation surgery: incidence, risk factors, and outcome. Eur Spine J 2010; 19 (3): 439–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stromqvist F, Jonsson B, Stromqvist B, Swedish Society of Spinal S. . Dural lesions in decompression for lumbar spinal stenosis: incidence, risk factors and effect on outcome. Eur Spine J 2012; 21 (5): 825–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stromqvist B, Fritzell P, Hagg O, Jonsson B, Sanden B, Swedish Society of Spinal S. Swespine: the Swedish spine register : the 2012 report. Eur Spine J 2013; 22 (4): 953–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan M, Karlsson J, Ware J E Jr.. SF-36 hälsoenkät : svensk manual och tolkningsguide. Book 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka M, Nakahara S, Inoue H. A pathologic study of discs in the elderly. Separation between the cartilaginous endplate and the vertebral body. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1993; 18 (11): 1456–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaupel J W, v., Kistowski K G. Broken limits to life expectancy. Ageing Horizons 2005; (3): 6–13. [Google Scholar]

- Werndle M C, Reza A, Wong K, Papadopoulos M C. Acute disc herniation in the elderly. Br J Neurosurg 2012; 26 (2): 255–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]