Abstract

Pregnane X receptor (PXR) is an adopted orphan nuclear receptor that is activated by a wide-range of endobiotics and xenobiotics, including chemotherapy drugs. PXR plays a major role in the metabolism and clearance of xenobiotics and endobiotics in liver and intestine via induction of drug-metabolizing enzymes and drug-transporting proteins. However, PXR is expressed in several cancer tissues and the accumulating evidence strongly points to the differential role of PXR in cancer growth and progression as well as in chemotherapy outcome. In cancer cells, besides regulating the gene expression of enzymes and proteins involved in drug metabolism and transport, PXR also regulates other genes involved in proliferation, metastasis, apoptosis, anti-apoptosis, inflammation, and oxidative stress. In this review, we focus on the differential role of PXR in a variety of cancers, including prostate, breast, ovarian, endometrial, and colon. We also discuss the future directions to further understand the differential role of PXR in cancer, and conclude with the need to identify novel selective PXR modulators to target PXR in PXR-expressing cancers.

Keywords: Pregnane X Receptor, cancer, MDR, inflammation, nuclear receptor

I. Introduction

The Pregnane X Receptor (PXR), a member of the nuclear receptor subfamily 1, group I (NR1l2), is an orphan nuclear receptor that in humans is encoded by NR1l2 gene. PXR is activated by binding to distinct endobiotics and xenobiotics that are both chemically and structurally diverse (Kliewer et al., 1998; Lehmann et al., 1998). Importantly, as pertinent to this review, these include chemotherapeutic drugs (Desai et al., 2002; Harmsen et al., 2010; Harmsen et al., 2013; Mani et al., 2005; Pondugula et al., 2015a). In its apo-form in cells (absence of an agonist), PXR is conventionally associated with transcriptional co-repressors such as nuclear receptor co-repressor 1 (NCoR1) and NCoR2 (Ding and Staudinger, 2005a, b; Johnson et al., 2006; Kliewer et al., 1998), which mediate repression of PXR basal transcription activity through the recruitment of histone deacetylases (Johnson et al., 2006). These concepts are contextual, as PXR protein in solution might associate with both co-repressors and co-activators in the presence or absence of ligands, thus challenging the current paradigm (Navaratnarajah et al., 2012). Furthermore, several modifications, particularly post-translational, are not ligand dependent and can modify receptor function in vitro and in tissues (Biswas et al., 2009; Biswas et al., 2011; Ma et al., 2015; Pondugula et al., 2015b; Smutny et al., 2013; Staudinger et al., 2011). Nonetheless, agonists such as rifampicin, SR12813, and chemotherapeutic drugs such as paclitaxel (Kliewer et al., 1998; Lehmann et al., 1998; Pondugula et al., 2015a; Pondugula et al., 2015c) bind to PXR. The consequence of direct binding to the ligand-binding pocket is thought to result in induced conformational changes that lead to dissociation (or a change in functional association with PXR) of co-repressors. There is either concomitant recruitment (or a change in functional association with PXR) of co-activators such as steroid receptor co-activator 1 (SRC-1) and SRC-3 with intrinsic histone acetyl-transferase activity (Ding and Staudinger, 2005a, b; Johnson et al., 2006; Kliewer et al., 1998). This complex, together, results in chromatin remodeling and subsequent transcriptional activation.

PXR regulates the proliferation of cells; however, again this might be context specific. PXR is important for liver regeneration (Dai et al., 2008). PXR activation induces hepatic proliferation and/or inhibits apoptosis through several mechanisms (Elcombe et al., 2012a; Elcombe et al., 2012b; Elcombe et al., 2010; Luisier et al., 2014; Xie et al., 2000). However, PXR activation also induces differentiation of osteoblasts and apoptosis of osteoclasts and certain leukemia cells (Austin et al., 2015; Hassen et al., 2014; Igarashi et al., 2007; Kameda et al., 1996; Tabb et al., 2003), suggesting that control of cell proliferation by PXR is likely tissue and cell-specific. A similar theme plays out in cancer cells, in which, PXR differentially regulates cell growth through multiple mechanisms in a variety of cancers, including liver, prostate, breast, ovarian, endometrial, cervical, and colon (Braeuning et al., 2014; Kakehashi et al., 2013; Koutsounas et al., 2013; Luisier et al., 2014; Ma et al., 2015; Niu et al., 2014; Pondugula and Mani, 2013; Qiao et al., 2013; Ross et al., 2010; Rouquie et al., 2014; Shizu et al., 2013; Tinwell et al., 2014). Additionally, PXR is involved in regulating metastasis of cancer cells (Gupta et al., 2008; Masuyama et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2011).

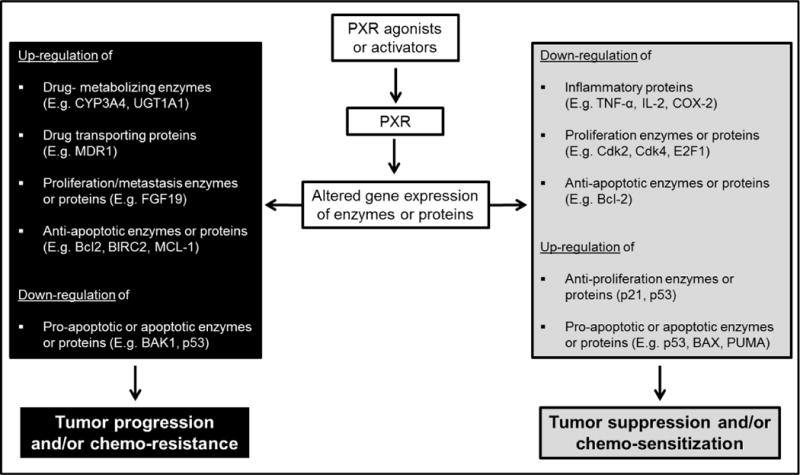

PXR also alters the outcome of chemotherapy in cancers, including breast, prostate, endometrial, ovarian, and colon (Gong et al., 2006; Koutsounas et al., 2013; Kwatra et al., 2013; MacLeod et al., 2015; Pondugula and Mani, 2013; Qiao et al., 2013; Verma et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2011; Zhou et al., 2008; Zhuo et al., 2014; Zucchini et al., 2005). PXR does so by regulating the expression/activity of enzymes and proteins involved in drug metabolism, drug transport, proliferation, apoptosis, anti-apoptosis, inflammation, and oxidative stress. In this review, we will update our prior review (Pondugula and Mani, 2013) with recent developments in PXR as a regulator of tumor development and progression, as well as in chemo-resistance, of major cancer types.

II. Differential role of PXR in cancer

Prostate cancer

In human prostate cancer, PXR is differentially expressed, with higher PXR expression in cancerous versus normal tissues (Chen et al., 2007; Fujimura et al., 2012). Human prostate cancer cell lines such as PC-3, LNCaP and DU145 also express PXR (Chen et al., 2007). While activation of PXR in PC3 cells with SR12813, increased mRNA expression of CYP3A4 and MDR1, and resistance of PC-3 cells to paclitaxel and vinblastine, genetic knockdown of PXR increased the sensitivity of PC3 cells to paclitaxel and vinblastine. These results suggested that while activation of PXR confers chemo-resistance, down-regulation of PXR chemo-sensitizes the prostate cancer cells. However, it was also reported that higher PXR expression correlated with good prognosis and increased survival in patients with prostate cancer (Fujimura et al., 2012).

Recently, a novel connection between TERE1 tumor suppressor protein and PXR has been identified in Castrate-Resistant Prostate Cancer (CRPC) (Fredericks et al., 2013). TERE1 is a prenyl-transferase that synthesizes vitamin K-2, which is a known potent endogenous ligand for the PXR. This study reported that 50% of primary and metastatic prostate cancer specimens exhibited a loss of TERE1 expression. Loss of TERE1 during tumor progression reduces K-2 levels resulting in reduced transcription of PXR target genes involved in cholesterol efflux and steroid catabolism. Thus, a combination of increased synthesis, along with decreased efflux and catabolism likely underlies the CRPC phenotype. LNCaP-C81 cells, which represent a cell model of CPRC, lack TERE1 protein, and displayed decreased expression of the PXR and PXR target genes that control cholesterol efflux and steroid catabolism. However, reconstitution of TERE1 expression in LNCaP-C81 cells reactivated PXR and turned on PXR target genes that coordinately promote both cholesterol efflux and androgen catabolism. These observations led to the proposition that TERE1 controls the CPRC phenotype by regulating the endogenous levels of Vitamin K-2 and hence the transcriptional control of a set of steroid catabolism genes via the PXR. Other studies corroborate PXR in a similar role in prostate cancer (Kumar et al., 2010; Reyes-Hernandez et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2010).

Breast cancer

The PXR is differentially expressed in human normal or cancerous breast tissue (Chen et al., 2009; Conde et al., 2008; Dotzlaw et al., 1999; Meyer zu Schwabedissen et al., 2008; Miki et al., 2006; Verma et al., 2009). While some studies presented evidence for selective PXR expression in the cancer tissue (Conde et al., 2008; Miki et al., 2006), others have reported PXR expression in both cancerous and adjacent normal tissues (Dotzlaw et al., 1999; Qiao and Yang, 2014). A higher expression of PXR is observed in tumors when compared to adjacent normal tissue (Meyer zu Schwabedissen et al., 2008). It was also reported that PXR expression was found to be higher in invasive stage than in early phase of breast cancer patients (Miki et al., 2006). Along the same lines, PXR expression positively correlated with breast cancer progression (Conde et al., 2008). These observations suggest that PXR expression may be context-specific and may play a role in development and progression of breast cancer.

PXR can also induce the proliferation of human breast cancer cells (Chen et al., 2009; Conde et al., 2008; Dotzlaw et al., 1999; Meyer zu Schwabedissen et al., 2008; Miki et al., 2006). Organic anion-transporting polypeptides (OATPs) is exclusively expressed or overexpressed in breast cancer tissue (Meyer zu Schwabedissen et al., 2008; Miki et al., 2006). In T47-D breast cancer cells, activation of PXR resulted in up-regulation of the expression of OATP1A2 and OATP1A2-mediated estrogen uptake as well as enhanced estrogen-dependent cell proliferation (Meyer zu Schwabedissen et al., 2008). On the other hand, inhibition or knockdown of PXR resulted in down-regulation of OATP1A2 expression and OATP1A2-regulated estrogen uptake. These observations support a possible role for PXR in breast tumor growth by enhancing the uptake of estrogens via OATPs, consequently increasing levels of intracellular estrogens that activate the estrogen receptor (ER) (Meyer zu Schwabedissen et al., 2008). It is important to note a significant correlation between PXR expression and ER status in breast cancer. While one study reported higher PXR expression in ER-positive cases (Miki et al., 2006), other studies reported an inverse relationship between PXR expression and ER status (Conde et al., 2008; Dotzlaw et al., 1999). Even in the context of this inverse relationship, PXR could contribute to growth in breast cancer cells because of the fact that estrogen binds and activates PXR. While these studies support the role for PXR in inducing breast tumors and show a significant trend supporting the anti-apoptotic role for PXR in breast cancer, a report by Verma et al provided contrary evidence showing that PXR induces apoptosis in breast cancer cells (Verma et al., 2009).

Besides its role in breast cancer growth and progression, PXR has implications in breast cancer chemo-resistance (Chen et al., 2009; Conde et al., 2008; Dotzlaw et al., 1999; Meyer zu Schwabedissen et al., 2008; Miki et al., 2006; Qiao and Yang, 2014; Xu et al., 2014). In MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 human breast cancer cells, while pharmacologic activation of PXR led to an increased resistance to Taxol as well as an increased expression of CYP3A4 and MDR1 (Chen et al., 2009), genetic knockdown of PXR sensitized the cells to Taxol, vinblastine or tamoxifen (Chen et al., 2009). In MCF-7 cells, it was also shown that paclitaxel induced drug resistance by enhancing the protein expression of PXR and MDR1 (Xu et al., 2014). Paclitaxel induction of MDR1 expression and function was significantly diminished in response to knockdown of PXR, suggesting that paclitaxel induces MDR1-mediated drug resistance by activating PXR (Xu et al., 2014). Similarly, in MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cells, SR12813 treatment not only led to an increased expression of PXR protein as well as drug-resistant genes such as MDR1 and BCRP (Qiao and Yang, 2014), but also resulted in increased resistance of MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 cells to docetaxel and 4-hydroxytamoxifen, respectively. Additionally, pretreatment with SR12813 led to reduced apoptosis of MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 cells induced by docetaxel and 4-hydroxytamoxifen, respectively. Finally, it is interesting to note that higher nuclear PXR expression was positively correlated with the cases that presented resistance to conventional treatments and that metastasized later, suggesting that overexpression of nuclear PXR may be considered as a potential poor prognostic indicator in breast cancer (Conde et al., 2008). Although PXR has a differential role in breast cancer, the overall implications of these data support that PXR confers resistance toward chemotherapy in PXR-positive breast cancer.

Ovarian cancer

PXR is expressed in human ovarian cancer tissues as well as in SKOV-3 and OVCAR-8 human ovarian cancer cell lines (Gupta et al., 2008). Activation of PXR with rifampicin in SKOV-3 cells not only resulted in induction of CYP3A4 and UGT1A1 expression, but also led to increased proliferation of SKOV-3 cells in vitro and SKOV-3 mouse xenografts in vivo. Furthermore, PXR activation in SKOV-3 cells also conferred resistance to paclitaxel, ixabepilone, and SN-38, indicating that activation of PXR induces both tumor growth and chemo-resistance in ovarian cancer cells. A significant negative relationship between PXR protein status and clinical outcome was also observed in patients with ovarian cancer (Yue et al., 2010). Together, these studies support the role of PXR in ovarian tumor progression and chemotherapeutic outcome.

Endometrial cancer

While PXR expression was not detected in normal tissues, variable levels of PXR expression has been noticed in human endometrial cancer tissues, (Masuyama et al., 2003), suggesting that PXR may play a role in endometrial tumor growth and chemo-resistance. Indeed, knockdown of PXR in HEC-1 human endometrial cancer cells decreased the expression of PXR target genes; CYP3A4 and MDR1 as well as enhanced growth inhibition and apoptosis in the presence of paclitaxel and cisplatin (Masuyama et al., 2007). By contrast, overexpression of PXR led to a significant decrease in cell growth inhibition and apoptosis in the presence of paclitaxel and cisplatin (Masuyama et al., 2007). These observations indicate that PXR has implications in endometrial cancer growth and drug response.

Cervical cancer

PXR is expressed in cervical cancer cell lines such as CaSki and HeLa as well as in cervical cancer tissue samples, although PXR levels were lower in the cancer tissues compared to normal control tissues (Niu et al., 2014). Activation of PXR not only resulted in inhibition of proliferation and colony formation of CaSki and HeLa cells by inducing G2/M cell-cycle arrest, but also led to attenuation of CaSki and HeLa xenograft tumor growth in nude mice (Niu et al., 2014). PXR-mediated G2/M cell-cycle arrest was accompanied by up-regulation of Cullin1–3 and MAD2L1, and down-regulation of ANAPC2 and CDKN1A. These data support a tumor suppressor role for PXR in cervical cancer as PXR signaling inhibits cervical cancer cell proliferation in vitro and cervical carcinoma growth in vivo.

Colon/colorectal cancer

There is evidence to support the role of PXR in colon cancer growth and metastasis as well as chemo-resistance. While activation of PXR induced growth, invasion, and migration of LS174T human colon cancer cells and mouse xenografts, knockdown of PXR inhibited proliferation and metastasis to liver from spleen (Wang et al., 2011). PXR regulates apoptotic and anti-apoptotic proteins in colon cancer cells similar to the findings observed in hepatocytes (Zucchini et al., 2005). Activation of PXR has been shown to protect HCT116 human colorectal cancer cells and LS180 human colon adenocarcinoma cells from the specific apoptotic insults (Zhou et al., 2008). The anti-apoptotic effect of PXR associated not only with up-regulation of several anti-apoptotic genes such as BAG3, BIRC2, and MCL-1 but also with down-regulation of pro-apoptotic genes such as BAK1 and P53.

However, it was also reported that PXR expression was lost or reduced in colon tumors, and that PXR overexpression decreased the proliferation of HT29 human colon cancer cells (Ouyang et al., 2010). PXR also inhibited HT29 xenograft tumor growth in mice as a result of cell cycle arrest at G0/G1 phase along with elevated p21 expression and inhibited E2F1 expression. A similar tumor suppressor role for PXR was observed in a very recent study of colon cancer (Cheng et al., 2014). Treatment with rifaximin, which selectively activates intestinal PXR, significantly decreased the number of colon tumors induced by azoxymethane (AOM)/dextran sulfate sodium (DSS) in PXR-humanized mice, but not in wild-type or PXR-null mice (Cheng et al., 2014). Additionally, rifaximin treatment increased the survival rate of PXR-humanized mice compared to wild-type or PXR-null mice. This was accompanied by rifaximin inhibition of up-regulated NF-kB-mediated inflammatory signaling in AOM/DSS-treated PXR-humanized mice. Moreover, rifaximin decreased cell proliferation and increased apoptosis. These results suggest that PXR exhibits a chemo-preventive role toward the xenobiotics-induced colon cancer by mediating anti-inflammation, anti-proliferation, and pro-apoptotic events.

Chemotherapy drugs, including PXR activator doxorubicin, induced MDR1 expression in LS180 human colon cancer cells (Harmsen et al., 2010). Activation of PXR with rifampicin decreased intracellular accumulation of doxorubicin and reduced the sensitivity of LS180 cells to the cytotoxic effect of doxorubicin, suggesting that chemotherapy drugs induce chemo-resistance by activation of PXR (Harmsen et al., 2010). Along the same lines, tyrosine kinase inhibitors such as Nilotinib and Gefitinib induced MDR1 protein expression and function in LS180 cells (Harmsen et al., 2013). Knockdown of endogenous PXR led to reduced MDR1 induction by Nilotinib and Gefitinib, suggesting that these tyrosine kinase inhibitors induce MDR1 by activating PXR.

Similarly, while activation of overexpressed PXR in LS174T cells induced CYP3A4 expression and increased resistance to irinotecan (CPT-11) and SN38 (Raynal et al., 2010), knockdown of overexpressed PXR reduced CYP3A4 induction and reversed resistance to SN38, suggesting that PXR could alter the outcome of chemotherapy drugs used in the treatment of colorectal cancer. It was also shown in LS180 cells that activation of PXR by SN-38, the active metabolite of irinotecan, resulted in induction of PXR target genes, including CYP3A4, CYP3A5, and MRP2 (Basseville et al., 2011). Consequently, LS180 cells overexpressing PXR were found to be less sensitive to irinotecan treatment, suggesting that the PXR pathway is involved in colon cancer irinotecan resistance (Basseville et al., 2011). These studies together suggest that PXR inhibition in colon cancer cells can enhance the efficacy of chemotherapy. It was indeed recently shown in HT-29 colon cancer cells that inhibition of PXR with bitter melon extracts resulted in enhanced doxorubicin effect on the cell proliferation, and sensitized the cells to doxorubicin by reducing the expression of PXR target proteins; MDR1, MRP-2, and BCRP (Kwatra et al., 2013). In keeping with colon cancer progression, PXR can activate plasminogen activator inhibitor type I gene expression (Stanley et al., 2015). More recent data, however, indicates PXR polymorphisms that reduce PXR levels, in colon cancer etiology in the Chinese population (Ni et al., 2015).

Hematologic cancers

Recent studies provide a tumor suppressor role for PXR in hematologic cancers. Initially, it was demonstrated that PXR-null mice developed B cell lymphoma in an age-dependent manner, suggesting a tumor suppressor role for PXR in B-1 cells (Casey et al., 2011). In chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) patients, it is known that the expression and activity of the uptake transporter human organic cation transporter 1 (hOCT1) positively determines the favorable outcome to Imatinib treatment (Austin et al., 2015). Pharmacologic activation of PXR with rifampicin or SR12813 in KCL22 CML cell line and CML primary cells resulted in up-regulation of hOCT1 expression, suggesting that PXR agonists may be potentially used to improve the efficacy of Imatinib in patients with CML (Austin et al., 2015). In another study of multiple myeloma, gene expression of uptake carriers, xenobiotic receptors, phase I and II drug metabolizing enzymes, and efflux transporters was examined in multiple myeloma cells of newly-diagnosed patients (Hassen et al., 2014). The patients with a favorable outcome exhibited an increased expression of xenobiotic receptors and their target genes, influx transporters and phase I/II drug metabolizing enzymes. In contrast, the patients with unfavorable outcome displayed a global down-regulation of xenobiotic receptors and the downstream detoxification genes.

Other cancers

PXR also has implications in the growth and/or chemo-resistance of several other cancers (Braeuning et al., 2014; Kodama and Negishi, 2011; Rigalli et al., 2015; Rigalli et al., 2013; Rioja et al., 2011; Rioja Zuazu et al., 2007). For example, in osteosarcoma cells, PXR activation is associated with chemo-resistance (Mensah-Osman et al., 2007). In this context, human PXR transfected normal osteoblast cells (hFOB) show increased proliferation in culture when exposed to Bisphenol A, a human PXR ligand (Miki et al., 2016). In Barrett’s esophagus patients, PXR expression is higher in high-grade versus low-grade dysplasia, suggesting that PXR may be involved in tumor progression in Barrett’s esophagus (van de Winkel et al., 2011b). PXR was suspected to contribute to chemo-resistance in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (Rigalli et al., 2013) but not to survival (Reuter et al., 2015). Very recently, PXR has been shown to contribute to chemo-resistance in BGC-823 human gastric cancer cells (Zhao et al., 2016) and in the pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma cells (Noll et al., 2016). Finally, PXR has also been shown to play a role in promoting the growth and chemo-resistance of liver tumors (Braeuning et al., 2014; Rigalli et al., 2015). However, PXR over-expression portends a favorable prognosis in pancreatic adenocarcinoma (Koutsounas et al., 2015) but might aggravate liver tumors (Kodama and Negishi, 2011; Kodama et al., 2015; Shizu et al., 2015). PXR is also more recently implicated as a driver of DNA damage in cutaneous carcinogenesis (Elentner et al., 2015). Like colon carcinogenesis, a PXR polymorphism in the 3′ UTR predicts for low PXR levels and increased lung cancer risk in smokers from China (Zhang et al., 2014a). Very recently, PXR was proposed to be a novel biomarker for predicting drug resistance in non-small cell lung cancer patients (Kong et al., 2016).

III. Future directions

The differential role of PXR in cancer suggests that several mechanisms may be involved in PXR-mediated tumor growth or chemotherapeutic response. Indeed, these may also contrast with cancer risk alleles, in that, PXR expression would contextually give rise to tumors. Identifying all the mechanisms will be critical to thoroughly understand the role of PXR in tumor progression or suppression as well as in chemo-resistance or chemo-sensitivity. For example, PXR activation induces steatosis (Bitter et al., 2014; Cheng et al., 2012; Hoekstra et al., 2009; Lee et al., 2008; Li et al., 2015) and many induced lipogenic pathway targets like CD36 are indeed implicated in malignancy (Kuriki et al., 2005; Moya et al., 2010; Zhan et al., 2008). Along the same lines, PXR activation promotes diet-induced obesity and type 2 diabetes (Gao and Xie, 2010) by deregulating glucose and lipid homeostasis (He et al., 2013; Spruiell et al., 2014a; Spruiell et al., 2014b). It is now well known that obesity and type 2 diabetes predispose the human patients to cancer. Thus, it is important to understand whether PXR dependent pathways play a role in mediating cancer in obese and type 2 diabetic patients.

Future studies also need to be focused on comprehensively identifying the PXR target genes, including noncoding RNAs, with their oncogenic or tumor suppressor nature in a cell/context-specific manner (Azuma et al., 2011; Ma et al., 2015; Noll et al., 2016; Vachirayonsti and Yan, 2016). It is known that PXR undergoes post-translational modifications such as phosphorylation and acetylation (Biswas et al., 2011; Elias et al., 2014; Elias et al., 2013; Pondugula et al., 2015c; Smutny et al., 2013; Staudinger et al., 2011; Sugatani et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2015). In keeping with the same theme, PXR is also regulated at transcriptional and post-transcriptional level (Habano et al., 2011; Kumari et al., 2012; Kumari et al., 2015; Li et al., 2016; Ma et al., 2015; Misawa et al., 2005; Smutny et al., 2013; Takagi et al., 2008; Tian, 2013; Xie et al., 2009). It is possible that some of these modifications may contribute to tissue/context specific PXR activity in tumors. A comprehensive investigation of such mechanisms in normal and tumor tissues will be useful to therapeutically target PXR in PXR-expressing cancers.

Several nuclear receptors induce tissue/context-specific phenotype in an isoform/alternative splice variant-dependent manner (Pondugula and Mani, 2013). The differential effects of PXR in different cancer tissues might be contributed by different isoforms/alternative splice variants of PXR as three PXR isoforms (i.e. PXR.1, PXR.2 and PXR.3) exhibit differential expression, ligand binding affinity, and transcriptional activity (Conde et al., 2008; Dotzlaw et al., 1999; Elias et al., 2013; Gardner-Stephen et al., 2004; Kliewer et al., 1998; Lamba et al., 2004; Lin et al., 2009; Tompkins et al., 2008). Indeed, PXR isoforms, PXR.1 and PXR.2, were found to be differentially expressed in human breast cancer (Conde et al., 2008; Dotzlaw et al., 1999). While low metastatic potential MCF cells expressed PXR.1 but not PXR.2 mRNA (Dotzlaw et al., 1999), high metastatic potential MDA-MB-231 cells expressed higher levels of both PXR.1 and PXR.2 mRNA (Dotzlaw et al., 1999). Very recently, a novel PXR isoform displaying a dominant negative activity has been identified in human hepatocellular carcinoma patients (Breuker et al., 2014). This isoform was found to be regulated by DNA methylation, and associated with outcomes of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma treated by resection. Tumor-specific regulation of isoforms or splice variants of some proteins has been reported to have very significant functional consequences (Naor et al., 2002). Indeed, the spliced murine PXR, mPXRΔ171–211, exhibits repressive action rather than activation (Matic et al., 2010). Identifying isoforms and spliced variants in human tumors and non-tumor tissues would be critical to defining the importance of the isoforms and variants of PXR in human cancer. Isoforms or spliced variants of PXR might favor selective PXR-protein interactions (Elias et al., 2013; Robbins et al., 2016), including PXR-co-regulator interactions. Thus a complete definition of PXR-protein interactions in specific tumor tissues would also be needed to comprehensively understand the effects of PXR activation. For example, in breast cancer, while it has been noted that nuclear localization of PXR portends a poor prognosis (Conde et al., 2008), another report suggests that PXR expression portends a favorable prognosis (Verma et al., 2009).

It is also possible that PXR polymorphisms contribute to the differential role of PXR in human cancers. Recent studies showed the interaction of PXR polymorphisms with human diseases, including cancer (Kotta-Loizou et al., 2013). While some PXR polymorphisms did not seem to interact with cancer growth, progression, or drug response (Justenhoven et al., 2011; Martino et al., 2013; Tham et al., 2007), several others were found to be significantly associated with cancer risk, growth, progression, or therapeutic outcome. For instance, the PXR polymorphisms have been shown to be associated with increased lung cancer risk in smokers (Zhang et al., 2014a) (Zhang et al., 2014b), higher prostate-specific antigen levels in prostate cancer patients (Reyes-Hernandez et al., 2014), lymphoma risk (Campa et al., 2012), pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of docetaxel and doxorubicin in breast cancer patients, pharmacokinetics and toxicity of irinotecan in colorectal cancer patients (Mbatchi et al., 2016), risk of colorectal cancer (Andersen et al., 2010), Barrett’s esophagus and esophageal adenocarcinoma (van de Winkel et al., 2011a), and docetaxel disposition in nasopharyngeal cancer patients (Chew et al., 2014). Hence, a complete mapping of PXR polymorphisms is required to fully understand the PXR activation in a variety of tumors.

IV. Conclusion

There are tissue/context specific consequences for PXR expression in cancer and normal tissues (Pondugula and Mani, 2013; Robbins and Chen, 2014). Several mechanisms have been proposed for PXR-mediated effects in cancer and include regulation of the genes involved in drug metabolism, drug transport, cell proliferation, metastasis, apoptosis, anti-apoptosis, inflammation, and anti-inflammation. Indeed, there is a complex interaction between PXR and p53 such that p53 can suppress PXR and drug metabolism and eventually enhance effects of chemotherapy; yet, PXR, when activated inhibits p53 and thus, decreases apoptosis. Therefore, a contextual relevance of these interactions remains at play in any given tumor type (Robbins et al., 2016). PXR has been proposed as a therapeutic target in treating several human diseases including cancer (Banerjee et al., 2014; Cecchin et al., 2016; Chai et al., 2016; Chen, 2008, 2010; Gao and Xie, 2012; Mani et al., 2013; Pondugula and Mani, 2013). Depending on the cancer tissue or cellular context, PXR activation or inhibition has been shown to exert anticancer phenotypes. Currently, there are several small molecules (Chen, 2008, 2010; Mani et al., 2013; Vadlapatla et al., 2013; Venkatesh et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2007) available to either activate or inhibit PXR function in cancer cells. However, there are no selective PXR modulators and identification of such novel selective small molecule modulators of PXR will be beneficial to improve the therapeutic outcomes in PXR- expressing cancers.

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of consequences of PXR activation in cancer cells

Table 1.

Role of PXR activation in specific cancer types

| Type of cancer | Characteristics of PXR activation (References) |

|---|---|

| Prostate cancer | Increases tumor progression and resistance to the chemotherapy drugs (Chen et al., 2007; Fredericks et al., 2013) |

| Breast cancer | Increases cell proliferation (Meyer zu Schwabedissen et al., 2008) and resistance to the chemotherapeutics (Chen et al., 2009; Qiao and Yang, 2014; Xu et al., 2014) |

| Inhibits cell proliferation and induces apoptosis (Verma et al., 2009) | |

| Ovarian cancer | Induces cell proliferation, tumor growth and resistance to the chemotherapeutics (Gupta et al., 2008) |

| Endometrial cancer | Decreases cell growth inhibition and apoptosis induced by the chemotherapy drugs (Masuyama et al., 2007) |

| Cervical cancer | Inhibits cell proliferation and tumor growth (Niu et al., 2014) |

| Colon cancer | Increases cell growth, invasion and metastasis (Wang et al., 2011). PXR activation also increases oxidative stress and anti-apoptotic activity, and decreases pro-apoptotic activity (Gong et al., 2006; Zhou et al., 2008). Moreover, PXR activation enhances resistance to the chemotherapy drugs (Basseville et al., 2011; Harmsen et al., 2010; Harmsen et al., 2013; Kwatra et al., 2013; Raynal et al., 2010) |

| Decreases inflammation, cell proliferation and tumor growth (Cheng et al., 2014; Ouyang et al., 2010). | |

| Liver cancer | Promotes tumor growth and chemo-resistance (Braeuning et al., 2014; Rigalli et al., 2015) |

| Gastric cancer | Contributes to chemo-resistance (Zhao et al., 2016) |

| Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma | Promotes chemo-resistance (Noll et al., 2016) |

| Hematologic cancers | Inhibits development of B cell lymphoma (Casey et al., 2011) and sensitizes chronic myeloid leukemia cells to the chemotherapeutics (Austin et al., 2015) |

Acknowledgments

This work is supported in part by an NIH grant (CA 127231; CA161879) to S.M. This work is also supported by the Auburn University Research Initiative in Cancer Grant and Animal Health and Disease Research Grant to S.P.

References

- Andersen V, Christensen J, Overvad K, Tjonneland A, Vogel U. Polymorphisms in NFkB, PXR, LXR and risk of colorectal cancer in a prospective study of Danes. BMC Cancer. 2010;10:484. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austin G, Holcroft A, Rinne N, Wang L, Clark RE. Evidence that the pregnane X and retinoid receptors PXR, RAR and RXR may regulate transcription of the transporter hOCT1 in chronic myeloid leukaemia cells. European journal of haematology. 2015;94:74–78. doi: 10.1111/ejh.12409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azuma K, Urano T, Watabe T, Ouchi Y, Inoue S. PROX1 suppresses vitamin K-induced transcriptional activity of Steroid and Xenobiotic Receptor. Genes to cells: devoted to molecular & cellular mechanisms. 2011;16:1063–1070. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2011.01551.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee M, Robbins D, Chen T. Targeting xenobiotic receptors PXR and CAR in human diseases. Drug discovery today. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2014.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basseville A, Preisser L, de Carne Trecesson S, Boisdron-Celle M, Gamelin E, Coqueret O, Morel A. Irinotecan induces steroid and xenobiotic receptor (SXR) signaling to detoxification pathway in colon cancer cells. Mol Cancer. 2011;10:80. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-10-80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biswas A, Mani S, Redinbo MR, Krasowski MD, Li H, Ekins S. Elucidating the ‘Jekyll and Hyde’ nature of PXR: the case for discovering antagonists or allosteric antagonists. Pharm Res. 2009;26:1807–1815. doi: 10.1007/s11095-009-9901-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biswas A, Pasquel D, Tyagi RK, Mani S. Acetylation of pregnane X receptor protein determines selective function independent of ligand activation. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2011;406:371–376. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.02.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bitter A, Rummele P, Klein K, Kandel BA, Rieger JK, Nussler AK, Zanger UM, Trauner M, Schwab M, Burk O. Pregnane X receptor activation and silencing promote steatosis of human hepatic cells by distinct lipogenic mechanisms. Archives of toxicology. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s00204-014-1348-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braeuning A, Gavrilov A, Brown S, Wolf CR, Henderson CJ, Schwarz M. Phenobarbital-mediated tumor promotion in transgenic mice with humanized CAR and PXR. Toxicol Sci. 2014;140:259–270. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfu099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breuker C, Planque C, Rajabi F, Nault JC, Couchy G, Zucman-Rossi J, Evrard A, Kantar J, Chevet E, Bioulac-Sage P, et al. Characterization of a novel PXR isoform with potential dominant-negative properties. Journal of hepatology. 2014;61:609–616. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campa D, Butterbach K, Slager SL, Skibola CF, de Sanjose S, Benavente Y, Becker N, Foretova L, Maynadie M, Cocco P, et al. A comprehensive study of polymorphisms in the ABCB1, ABCC2, ABCG2, NR1I2 genes and lymphoma risk. International journal of cancer Journal international du cancer. 2012;131:803–812. doi: 10.1002/ijc.26436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casey SC, Nelson EL, Turco GM, Janes MR, Fruman DA, Blumberg B. B-1 cell lymphoma in mice lacking the steroid and xenobiotic receptor, SXR. Mol Endocrinol. 2011;25:933–943. doi: 10.1210/me.2010-0486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cecchin E, De Mattia E, Toffoli G. Nuclear receptors and drug metabolism for the personalization of cancer therapy. Expert opinion on drug metabolism & toxicology. 2016;12:291–306. doi: 10.1517/17425255.2016.1141196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chai SC, Cherian MT, Wang YM, Chen T. Small-molecule modulators of PXR and CAR. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2016.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen T. Nuclear receptor drug discovery. Current opinion in chemical biology. 2008;12:418–426. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2008.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen T. Overcoming drug resistance by regulating nuclear receptors. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2010;62:1257–1264. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2010.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Tang Y, Chen S, Nie D. Regulation of drug resistance by human pregnane X receptor in breast cancer. Cancer biology & therapy. 2009;8:1265–1272. doi: 10.4161/cbt.8.13.8696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Tang Y, Wang MT, Zeng S, Nie D. Human pregnane X receptor and resistance to chemotherapy in prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2007;67:10361–10367. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng J, Fang ZZ, Nagaoka K, Okamoto M, Qu A, Tanaka N, Kimura S, Gonzalez FJ. Activation of intestinal human pregnane X receptor protects against azoxymethane/dextran sulfate sodium-induced colon cancer. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2014;351:559–567. doi: 10.1124/jpet.114.215913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng J, Krausz KW, Tanaka N, Gonzalez FJ. Chronic exposure to rifaximin causes hepatic steatosis in pregnane X receptor-humanized mice. Toxicol Sci. 2012;129:456–468. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfs211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chew SC, Lim J, Singh O, Chen X, Tan EH, Lee EJ, Chowbay B. Pharmacogenetic effects of regulatory nuclear receptors (PXR, CAR, RXRalpha and HNF4alpha) on docetaxel disposition in Chinese nasopharyngeal cancer patients. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2014;70:155–166. doi: 10.1007/s00228-013-1596-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conde I, Lobo MV, Zamora J, Perez J, Gonzalez FJ, Alba E, Fraile B, Paniagua R, Arenas MI. Human pregnane X receptor is expressed in breast carcinomas, potential heterodimers formation between hPXR and RXR-alpha. BMC Cancer. 2008;8:174. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-8-174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai G, He L, Bu P, Wan YJ. Pregnane X receptor is essential for normal progression of liver regeneration. Hepatology. 2008;47:1277–1287. doi: 10.1002/hep.22129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai PB, Nallani SC, Sane RS, Moore LB, Goodwin BJ, Buckley DJ, Buckley AR. Induction of cytochrome P450 3A4 in primary human hepatocytes and activation of the human pregnane X receptor by tamoxifen and 4-hydroxytamoxifen. Drug Metab Dispos. 2002;30:608–612. doi: 10.1124/dmd.30.5.608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding X, Staudinger JL. Induction of drug metabolism by forskolin: the role of the pregnane X receptor and the protein kinase a signal transduction pathway. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005a;312:849–856. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.076331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding X, Staudinger JL. Repression of PXR-mediated induction of hepatic CYP3A gene expression by protein kinase C. Biochem Pharmacol. 2005b;69:867–873. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2004.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dotzlaw H, Leygue E, Watson P, Murphy LC. The human orphan receptor PXR messenger RNA is expressed in both normal and neoplastic breast tissue. Clin Cancer Res. 1999;5:2103–2107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elcombe CR, Elcombe BM, Foster JR, Chang SC, Ehresman DJ, Butenhoff JL. Hepatocellular hypertrophy and cell proliferation in Sprague-Dawley rats from dietary exposure to potassium perfluorooctanesulfonate results from increased expression of xenosensor nuclear receptors PPARalpha and CAR/PXR. Toxicology. 2012a;293:16–29. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2011.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elcombe CR, Elcombe BM, Foster JR, Chang SC, Ehresman DJ, Noker PE, Butenhoff JL. Evaluation of hepatic and thyroid responses in male Sprague Dawley rats for up to eighty-four days following seven days of dietary exposure to potassium perfluorooctanesulfonate. Toxicology. 2012b;293:30–40. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2011.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elcombe CR, Elcombe BM, Foster JR, Farrar DG, Jung R, Chang SC, Kennedy GL, Butenhoff JL. Hepatocellular hypertrophy and cell proliferation in Sprague-Dawley rats following dietary exposure to ammonium perfluorooctanoate occurs through increased activation of the xenosensor nuclear receptors PPARalpha and CAR/PXR. Archives of toxicology. 2010;84:787–798. doi: 10.1007/s00204-010-0572-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elentner A, Ortner D, Clausen B, Gonzalez FJ, Fernandez-Salguero PM, Schmuth M, Dubrac S. Skin response to a carcinogen involves the xenobiotic receptor pregnane X receptor. Experimental dermatology. 2015 doi: 10.1111/exd.12766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elias A, High AA, Mishra A, Ong SS, Wu J, Peng J, Chen T. Identification and characterization of phosphorylation sites within the pregnane X receptor protein. Biochem Pharmacol. 2014;87:360–370. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2013.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elias A, Wu J, Chen T. Tumor Suppressor Protein p53 Negatively Regulates Human Pregnane X Receptor Activity. Mol Pharmacol. 2013;83:1229–1236. doi: 10.1124/mol.113.085092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredericks WJ, Sepulveda J, Lai P, Tomaszewski JE, Lin MF, McGarvey T, Rauscher FJ, 3rd, Malkowicz SB. The tumor suppressor TERE1 (UBIAD1) prenyltransferase regulates the elevated cholesterol phenotype in castration resistant prostate cancer by controlling a program of ligand dependent SXR target genes. Oncotarget. 2013;4:1075–1092. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.1103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujimura T, Takahashi S, Urano T, Tanaka T, Zhang W, Azuma K, Takayama K, Obinata D, Murata T, Horie-Inoue K, et al. Clinical significance of steroid and xenobiotic receptor and its targeted gene CYP3A4 in human prostate cancer. Cancer Sci. 2012;103:176–180. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2011.02143.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao J, Xie W. Pregnane X receptor and constitutive androstane receptor at the crossroads of drug metabolism and energy metabolism. Drug Metab Dispos. 2010;38:2091–2095. doi: 10.1124/dmd.110.035568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao J, Xie W. Targeting xenobiotic receptors PXR and CAR for metabolic diseases. Trends in pharmacological sciences. 2012;33:552–558. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2012.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner-Stephen D, Heydel JM, Goyal A, Lu Y, Xie W, Lindblom T, Mackenzie P, Radominska-Pandya A. Human PXR variants and their differential effects on the regulation of human UDP-glucuronosyltransferase gene expression. Drug Metab Dispos. 2004;32:340–347. doi: 10.1124/dmd.32.3.340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong H, Singh SV, Singh SP, Mu Y, Lee JH, Saini SP, Toma D, Ren S, Kagan VE, Day BW, et al. Orphan nuclear receptor pregnane X receptor sensitizes oxidative stress responses in transgenic mice and cancerous cells. Mol Endocrinol. 2006;20:279–290. doi: 10.1210/me.2005-0205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta D, Venkatesh M, Wang H, Kim S, Sinz M, Goldberg GL, Whitney K, Longley C, Mani S. Expanding the roles for pregnane X receptor in cancer: proliferation and drug resistance in ovarian cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:5332–5340. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habano W, Gamo T, Terashima J, Sugai T, Otsuka K, Wakabayashi G, Ozawa S. Involvement of promoter methylation in the regulation of Pregnane X receptor in colon cancer cells. BMC Cancer. 2011;11:81. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-11-81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harmsen S, Meijerman I, Febus CL, Maas-Bakker RF, Beijnen JH, Schellens JH. PXR-mediated induction of P-glycoprotein by anticancer drugs in a human colon adenocarcinoma-derived cell line. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2010;66:765–771. doi: 10.1007/s00280-009-1221-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harmsen S, Meijerman I, Maas-Bakker RF, Beijnen JH, Schellens JH. PXR-mediated P-glycoprotein induction by small molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitors. European journal of pharmaceutical sciences: official journal of the European Federation for Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2013;48:644–649. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2012.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassen W, Kassambara A, Reme T, Sahota S, Seckinger A, Vincent L, Cartron G, Moreaux J, Hose D, Klein B. Drug metabolism and clearance system in tumor cells of patients with multiple myeloma. Oncotarget. 2014 doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He J, Gao J, Xu M, Ren S, Stefanovic-Racic M, O’Doherty RM, Xie W. PXR ablation alleviates diet-induced and genetic obesity and insulin resistance in mice. Diabetes. 2013;62:1876–1887. doi: 10.2337/db12-1039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoekstra M, Lammers B, Out R, Li Z, Van Eck M, Van Berkel TJ. Activation of the nuclear receptor PXR decreases plasma LDL-cholesterol levels and induces hepatic steatosis in LDL receptor knockout mice. Mol Pharm. 2009;6:182–189. doi: 10.1021/mp800131d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Igarashi M, Yogiashi Y, Mihara M, Takada I, Kitagawa H, Kato S. Vitamin K induces osteoblast differentiation through pregnane X receptor-mediated transcriptional control of the Msx2 gene. Molecular and cellular biology. 2007;27:7947–7954. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00813-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Johnson DR, Li CW, Chen LY, Ghosh JC, Chen JD. Regulation and binding of pregnane X receptor by nuclear receptor corepressor silencing mediator of retinoid and thyroid hormone receptors (SMRT) Mol Pharmacol. 2006;69:99–108. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.013375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Justenhoven C, Schaeffeler E, Winter S, Baisch C, Hamann U, Harth V, Rabstein S, Spickenheuer A, Pesch B, Bruning T, et al. Polymorphisms of the nuclear receptor pregnane X receptor and organic anion transporter polypeptides 1A2, 1B1, 1B3, and 2B1 are not associated with breast cancer risk. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;125:563–569. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-1046-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakehashi A, Hagiwara A, Imai N, Nagano K, Nishimaki F, Banton M, Wei M, Fukushima S, Wanibuchi H. Mode of action of ethyl tertiary-butyl ether hepatotumorigenicity in the rat: evidence for a role of oxidative stress via activation of CAR, PXR and PPAR signaling pathways. Toxicology and applied pharmacology. 2013;273:390–400. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2013.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kameda T, Miyazawa K, Mori Y, Yuasa T, Shiokawa M, Nakamaru Y, Mano H, Hakeda Y, Kameda A, Kumegawa M. Vitamin K2 inhibits osteoclastic bone resorption by inducing osteoclast apoptosis. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 1996;220:515–519. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.0436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kliewer SA, Moore JT, Wade L, Staudinger JL, Watson MA, Jones SA, McKee DD, Oliver BB, Willson TM, Zetterstrom RH, et al. An orphan nuclear receptor activated by pregnanes defines a novel steroid signaling pathway. Cell. 1998;92:73–82. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80900-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kodama S, Negishi M. Pregnane X receptor PXR activates the GADD45beta gene, eliciting the p38 MAPK signal and cell migration. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:3570–3578. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.179812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kodama S, Yamazaki Y, Negishi M. Pregnane X Receptor Represses HNF4alpha Gene to Induce Insulin-Like Growth Factor-Binding Protein IGFBP1 that Alters Morphology of and Migrates HepG2 Cells. Molecular pharmacology. 2015;88:746–757. doi: 10.1124/mol.115.099341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong Q, Han Z, Zuo X, Wei H, Huang W. Co-expression of pregnane X receptor and ATP-binding cassette sub-family B member 1 in peripheral blood: A prospective indicator for drug resistance prediction in non-small cell lung cancer. Oncology letters. 2016;11:3033–3039. doi: 10.3892/ol.2016.4369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotta-Loizou I, Patsouris E, Theocharis S. Pregnane X receptor polymorphisms associated with human diseases. Expert opinion on therapeutic targets. 2013;17:1167–1177. doi: 10.1517/14728222.2013.823403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koutsounas I, Giaginis C, Alexandrou P, Zizi-Serbetzoglou A, Patsouris E, Kouraklis G, Theocharis S. Pregnane X Receptor Expression in Human Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma: Associations With Clinicopathologic Parameters, Tumor Proliferative Capacity, Patients’ Survival, and Retinoid X Receptor Expression. Pancreas. 2015;44:1134–1140. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0000000000000405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koutsounas I, Patsouris E, Theocharis S. Pregnane X receptor and human malignancy. Histology and histopathology. 2013;28:405–420. doi: 10.14670/HH-28.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Jaiswal B, Kumar S, Negi S, Tyagi RK. Cross-talk between androgen receptor and pregnane and xenobiotic receptor reveals existence of a novel modulatory action of anti-androgenic drugs. Biochem Pharmacol. 2010;80:964–976. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2010.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumari S, Mukhopadhyay G, Tyagi RK. Transcriptional regulation of mouse PXR gene: an interplay of transregulatory factors. PloS one. 2012;7:e44126. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0044126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumari S, Saradhi M, Rana M, Chatterjee S, Aumercier M, Mukhopadhyay G, Tyagi RK. Pregnane and Xenobiotic Receptor gene expression in liver cells is modulated by Ets-1 in synchrony with transcription factors Pax5, LEF-1 and c-Jun. Experimental cell research. 2015;330:398–411. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2014.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuriki K, Hamajima N, Chiba H, Kanemitsu Y, Hirai T, Kato T, Saito T, Matsuo K, Koike K, Tokudome S, et al. Increased risk of colorectal cancer due to interactions between meat consumption and the CD36 gene A52C polymorphism among Japanese. Nutrition and cancer. 2005;51:170–177. doi: 10.1207/s15327914nc5102_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwatra D, Venugopal A, Standing D, Ponnurangam S, Dhar A, Mitra A, Anant S. Bitter melon extracts enhance the activity of chemotherapeutic agents through the modulation of multiple drug resistance. Journal of pharmaceutical sciences. 2013;102:4444–4454. doi: 10.1002/jps.23753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamba V, Yasuda K, Lamba JK, Assem M, Davila J, Strom S, Schuetz EG. PXR (NR1I2): splice variants in human tissues, including brain, and identification of neurosteroids and nicotine as PXR activators. Toxicology and applied pharmacology. 2004;199:251–265. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2003.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JH, Zhou J, Xie W. PXR and LXR in hepatic steatosis: a new dog and an old dog with new tricks. Mol Pharm. 2008;5:60–66. doi: 10.1021/mp700121u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann JM, McKee DD, Watson MA, Willson TM, Moore JT, Kliewer SA. The human orphan nuclear receptor PXR is activated by compounds that regulate CYP3A4 gene expression and cause drug interactions. J Clin Invest. 1998;102:1016–1023. doi: 10.1172/JCI3703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Li H, Garzel B, Yang H, Sueyoshi T, Li Q, Shu Y, Zhang J, Hu B, Heyward S, et al. SLC13A5 is A Novel Transcriptional Target of the Pregnane X Receptor and Sensitizes Drug-Induced Steatosis in Human Liver. Mol Pharmacol. 2015 doi: 10.1124/mol.114.097287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li T, Kong AT, Ma Z, Liu H, Liu P, Xiao Y, Jiang X, Wang L. Protein arginine methyltransferase 1 may be involved in pregnane x receptor-activated overexpression of multidrug resistance 1 gene during acquired multidrug resistant. Oncotarget. 2016 doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.7752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin YS, Yasuda K, Assem M, Cline C, Barber J, Li CW, Kholodovych V, Ai N, Chen JD, Welsh WJ, et al. The major human pregnane X receptor (PXR) splice variant, PXR.2, exhibits significantly diminished ligand-activated transcriptional regulation. Drug Metab Dispos. 2009;37:1295–1304. doi: 10.1124/dmd.108.025213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luisier R, Lempiainen H, Scherbichler N, Braeuning A, Geissler M, Dubost V, Muller A, Scheer N, Chibout SD, Hara H, et al. Phenobarbital induces cell cycle transcriptional responses in mouse liver humanized for constitutive androstane and pregnane x receptors. Toxicol Sci. 2014;139:501–511. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfu038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma X, Chen J, Tian Y. Pregnane X receptor as the “sensor and effector” in regulating epigenome. Journal of cellular physiology. 2015;230:752–757. doi: 10.1002/jcp.24838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLeod AK, McLaughlin LA, Henderson CJ, Wolf CR. Activation Status of the Pregnane X Receptor Influences Vemurafenib Availability in Humanized Mouse Models. Cancer Res. 2015;75:4573–4581. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-1454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mani S, Dou W, Redinbo MR. PXR antagonists and implication in drug metabolism. Drug metabolism reviews. 2013;45:60–72. doi: 10.3109/03602532.2012.746363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mani S, Huang H, Sundarababu S, Liu W, Kalpana G, Smith AB, Horwitz SB. Activation of the steroid and xenobiotic receptor (human pregnane X receptor) by nontaxane microtubule-stabilizing agents. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:6359–6369. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martino A, Sainz J, Manuel Reis R, Moreno V, Buda G, Lesueur F, Marques H, Garcia-Sanz R, Rios R, Stein A, et al. Polymorphisms in regulators of xenobiotic transport and metabolism genes PXR and CAR do not affect multiple myeloma risk: a case-control study in the context of the IMMEnSE consortium. Journal of human genetics. 2013;58:155–159. doi: 10.1038/jhg.2012.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masuyama H, Hiramatsu Y, Kodama J, Kudo T. Expression and potential roles of pregnane X receptor in endometrial cancer. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:4446–4454. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-030203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masuyama H, Nakatsukasa H, Takamoto N, Hiramatsu Y. Down-regulation of pregnane X receptor contributes to cell growth inhibition and apoptosis by anticancer agents in endometrial cancer cells. Mol Pharmacol. 2007;72:1045–1053. doi: 10.1124/mol.107.037937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matic M, Corradin AP, Tsoli M, Clarke SJ, Polly P, Robertson GR. The alternatively spliced murine pregnane X receptor isoform, mPXR (delta171–211) exhibits a repressive action. The international journal of biochemistry & cell biology. 2010;42:672–682. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2010.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mbatchi LC, Robert J, Ychou M, Boyer JC, Del Rio M, Gassiot M, Thomas F, Tubiana N, Evrard A. Effect of Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms in the Xenobiotic-sensing Receptors NR1I2 and NR1I3 on the Pharmacokinetics and Toxicity of Irinotecan in Colorectal Cancer Patients. Clinical pharmacokinetics. 2016 doi: 10.1007/s40262-016-0392-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mensah-Osman EJ, Thomas DG, Tabb MM, Larios JM, Hughes DP, Giordano TJ, Lizyness ML, Rae JM, Blumberg B, Hollenberg PF, et al. Expression levels and activation of a PXR variant are directly related to drug resistance in osteosarcoma cell lines. Cancer. 2007;109:957–965. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer zu Schwabedissen HE, Tirona RG, Yip CS, Ho RH, Kim RB. Interplay between the nuclear receptor pregnane X receptor and the uptake transporter organic anion transporter polypeptide 1A2 selectively enhances estrogen effects in breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2008;68:9338–9347. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miki Y, Hata S, Nagasaki S, Suzuki T, Ito K, Kumamoto H, Sasano H. Steroid and xenobiotic receptor-mediated effects of bisphenol a on human osteoblasts. Life sciences. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2016.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miki Y, Suzuki T, Kitada K, Yabuki N, Shibuya R, Moriya T, Ishida T, Ohuchi N, Blumberg B, Sasano H. Expression of the steroid and xenobiotic receptor and its possible target gene, organic anion transporting polypeptide-A, in human breast carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2006;66:535–542. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misawa A, Inoue J, Sugino Y, Hosoi H, Sugimoto T, Hosoda F, Ohki M, Imoto I, Inazawa J. Methylation-associated silencing of the nuclear receptor 1I2 gene in advanced-type neuroblastomas, identified by bacterial artificial chromosome array-based methylated CpG island amplification. Cancer Res. 2005;65:10233–10242. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moya M, Gomez-Lechon MJ, Castell JV, Jover R. Enhanced steatosis by nuclear receptor ligands: a study in cultured human hepatocytes and hepatoma cells with a characterized nuclear receptor expression profile. Chemico-biological interactions. 2010;184:376–387. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2010.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naor D, Nedvetzki S, Golan I, Melnik L, Faitelson Y. CD44 in cancer. Critical reviews in clinical laboratory sciences. 2002;39:527–579. doi: 10.1080/10408360290795574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navaratnarajah P, Steele BL, Redinbo MR, Thompson NL. Rifampicin-independent interactions between the pregnane X receptor ligand binding domain and peptide fragments of coactivator and corepressor proteins. Biochemistry. 2012;51:19–31. doi: 10.1021/bi2011674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni H, Su B, Pan L, Li X, Zhu X, Chen X. Functional variants inPXRare associated with colorectal cancer susceptibility in Chinese populations. Cancer epidemiology. 2015;39:972–977. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2015.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niu Y, Wang Z, Huang H, Zhong S, Cai W, Xie Y, Shi G. Activated pregnane X receptor inhibits cervical cancer cell proliferation and tumorigenicity by inducing G2/M cell-cycle arrest. Cancer letters. 2014;347:88–97. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2014.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noll EM, Eisen C, Stenzinger A, Espinet E, Muckenhuber A, Klein C, Vogel V, Klaus B, Nadler W, Rosli C, et al. CYP3A5 mediates basal and acquired therapy resistance in different subtypes of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Nature medicine. 2016;22:278–287. doi: 10.1038/nm.4038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouyang N, Ke S, Eagleton N, Xie Y, Chen G, Laffins B, Yao H, Zhou B, Tian Y. Pregnane X receptor suppresses proliferation and tumourigenicity of colon cancer cells. Br J Cancer. 2010;102:1753–1761. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pondugula SR, Flannery PC, Abbott KL, Coleman ES, Mani S, Temesgen S, Xie W. Diindolylmethane, a naturally occurring compound, induces CYP3A4 and MDR1 gene expression by activating human PXR. Toxicology letters. 2015a;232:580–589. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2014.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pondugula SR, Flannery PC, Apte U, Babu JR, Geetha T, Rege SD, Chen T, Abbott KL. Mg2+/Mn2+-Dependent Phosphatase 1A Is Involved in Regulating Pregnane X Receptor-Mediated Cytochrome p450 3A4 Gene Expression. Drug metabolism and disposition: the biological fate of chemicals. 2015b;43:385–391. doi: 10.1124/dmd.114.062083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pondugula SR, Flannery PC, Apte U, Babu JR, Geetha T, Rege SD, Chen T, Abbott KL. Mg2+/Mn2+-Dependent Phosphatase 1A Is Involved in Regulating Pregnane X Receptor-Mediated Cytochrome p450 3A4 Gene Expression. Drug Metab Dispos. 2015c;43:385–391. doi: 10.1124/dmd.114.062083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pondugula SR, Mani S. Pregnane xenobiotic receptor in cancer pathogenesis and therapeutic response. Cancer letters. 2013;328:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2012.08.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiao E, Ji M, Wu J, Ma R, Zhang X, He Y, Zha Q, Song X, Zhu LW, Tang J. Expression of the PXR gene in various types of cancer and drug resistance. Oncology letters. 2013;5:1093–1100. doi: 10.3892/ol.2013.1149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiao EQ, Yang HJ. Effect of pregnane X receptor expression on drug resistance in breast cancer. Oncology letters. 2014;7:1191–1196. doi: 10.3892/ol.2014.1817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raynal C, Pascussi JM, Leguelinel G, Breuker C, Kantar J, Lallemant B, Poujol S, Bonnans C, Joubert D, Hollande F, et al. Pregnane X Receptor (PXR) expression in colorectal cancer cells restricts irinotecan chemosensitivity through enhanced SN-38 glucuronidation. Mol Cancer. 2010;9:46. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-9-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reuter T, Warta R, Theile D, Meid AD, Rigalli JP, Mogler C, Herpel E, Grabe N, Lahrmann B, Plinkert PK, et al. Role of NR1I2 (pregnane X receptor) polymorphisms in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s archives of pharmacology. 2015;388:1141–1150. doi: 10.1007/s00210-015-1150-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes-Hernandez OD, Vega L, Jimenez-Rios MA, Martinez-Cervera PF, Lugo-Garcia JA, Hernandez-Cadena L, Ostrosky-Wegman P, Orozco L, Elizondo G. The PXR rs7643645 polymorphism is associated with the risk of higher prostate-specific antigen levels in prostate cancer patients. PloS one. 2014;9:e99974. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0099974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigalli JP, Ciriaci N, Arias A, Ceballos MP, Villanueva SS, Luquita MG, Mottino AD, Ghanem CI, Catania VA, Ruiz ML. Regulation of multidrug resistance proteins by genistein in a hepatocarcinoma cell line: impact on sorafenib cytotoxicity. PloS one. 2015;10:e0119502. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0119502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigalli JP, Reuter T, Herold-Mende C, Dyckhoff G, Haefeli WE, Weiss J, Theile D. Minor role of pregnane-x-receptor for acquired multidrug resistance in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma in vitro. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2013;71:1335–1343. doi: 10.1007/s00280-013-2133-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rioja J, Bandres E, Rosell Costa D, Rincon A, Lopez I, Zudaire Bergera JJ, Garcia Foncillas J, Gil MJ, Panizo A, Plaza L, et al. Association of steroid and xenobiotic receptor (SXR) and multidrug resistance 1 (MDR1) gene expression with survival among patients with invasive bladder carcinoma. BJU international. 2011;107:1833–1838. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2010.09653.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rioja Zuazu J, Bandres Elizalde E, Rosell Costa D, Rincon Mayans A, Zudaire Bergera J, Gil Sanz MJ, Rioja Sanz LA, Garcia Foncillas J, Berian Polo JM. Steroid and xenobiotic receptor (SXR), multidrug resistance gene (MDR1) and GSTs, SULTs and CYP polymorphism expression in invasive bladder cancer, analysis of their expression and correlation with other prognostic factors. Actas urologicas espanolas. 2007;31:1107–1116. doi: 10.1016/s0210-4806(07)73772-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robbins D, Bakke J, Cherian MT, Wu J, Chen T. PXR interaction with p53: a meeting of two masters. Cell death & disease. 2016;7:e2218. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2016.122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robbins D, Chen T. Tissue-specific regulation of pregnane X receptor in cancer development and therapy. Cell & bioscience. 2014;4:17. doi: 10.1186/2045-3701-4-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross J, Plummer SM, Rode A, Scheer N, Bower CC, Vogel O, Henderson CJ, Wolf CR, Elcombe CR. Human constitutive androstane receptor (CAR) and pregnane X receptor (PXR) support the hypertrophic but not the hyperplastic response to the murine nongenotoxic hepatocarcinogens phenobarbital and chlordane in vivo. Toxicol Sci. 2010;116:452–466. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfq118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouquie D, Tinwell H, Blanck O, Schorsch F, Geter D, Wason S, Bars R. Thyroid tumor formation in the male mouse induced by fluopyram is mediated by activation of hepatic CAR/PXR nuclear receptors. Regulatory toxicology and pharmacology: RTP. 2014;70:673–680. doi: 10.1016/j.yrtph.2014.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shizu R, Abe T, Benoki S, Takahashi M, Kodama S, Miayata M, Matsuzawa A, Yoshinari K. PXR stimulates growth factor-mediated hepatocyte proliferation by crosstalk with FOXO transcription factor. The Biochemical journal. 2015 doi: 10.1042/BJ20150734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shizu R, Benoki S, Numakura Y, Kodama S, Miyata M, Yamazoe Y, Yoshinari K. Xenobiotic-induced hepatocyte proliferation associated with constitutive active/androstane receptor (CAR) or peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha (PPARalpha) is enhanced by pregnane X receptor (PXR) activation in mice. PloS one. 2013;8:e61802. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smutny T, Mani S, Pavek P. Post-translational and post-transcriptional modifications of pregnane X receptor (PXR) in regulation of the cytochrome P450 superfamily. Curr Drug Metab. 2013;14:1059–1069. doi: 10.2174/1389200214666131211153307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spruiell K, Jones DZ, Cullen JM, Awumey EM, Gonzalez FJ, Gyamfi MA. Role of human pregnane X receptor in high fat diet-induced obesity in pre-menopausal female mice. Biochem Pharmacol. 2014a;89:399–412. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2014.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spruiell K, Richardson RM, Cullen JM, Awumey EM, Gonzalez FJ, Gyamfi MA. Role of pregnane X receptor in obesity and glucose homeostasis in male mice. J Biol Chem. 2014b;289:3244–3261. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.494575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley FM, Linder KM, Cardozo TJ. Statins Increase Plasminogen Activator Inhibitor Type 1 Gene Transcription through a Pregnane X Receptor Regulated Element. PloS one. 2015;10:e0138097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0138097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staudinger JL, Xu C, Biswas A, Mani S. Post-translational modification of pregnane x receptor. Pharmacological research: the official journal of the Italian Pharmacological Society. 2011;64:4–10. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2011.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugatani J, Noguchi Y, Hattori Y, Yamaguchi M, Yamazaki Y, Ikari A. Threonine-408 Regulates the Stability of the Human Pregnane X Receptor Through its Phosphorylation and the CHIP/Chaperone-Autophagy Pathway. Drug Metab Dispos. 2015 doi: 10.1124/dmd.115.066308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabb MM, Sun A, Zhou C, Grun F, Errandi J, Romero K, Pham H, Inoue S, Mallick S, Lin M, et al. Vitamin K2 regulation of bone homeostasis is mediated by the steroid and xenobiotic receptor SXR. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:43919–43927. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303136200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takagi S, Nakajima M, Mohri T, Yokoi T. Post-transcriptional regulation of human pregnane X receptor by micro-RNA affects the expression of cytochrome P450 3A4. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:9674–9680. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M709382200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tham LS, Holford NH, Hor SY, Tan T, Wang L, Lim RC, Lee HS, Lee SC, Goh BC. Lack of association of single-nucleotide polymorphisms in pregnane X receptor, hepatic nuclear factor 4alpha, and constitutive androstane receptor with docetaxel pharmacokinetics. Clinical cancer research: an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2007;13:7126–7132. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian Y. Epigenetic regulation of pregnane X receptor activity. Drug metabolism reviews. 2013;45:166–172. doi: 10.3109/03602532.2012.756012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tinwell H, Rouquie D, Schorsch F, Geter D, Wason S, Bars R. Liver tumor formation in female rat induced by fluopyram is mediated by CAR/PXR nuclear receptor activation. Regulatory toxicology and pharmacology: RTP. 2014;70:648–658. doi: 10.1016/j.yrtph.2014.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tompkins LM, Sit TL, Wallace AD. Unique transcription start sites and distinct promoter regions differentiate the pregnane X receptor (PXR) isoforms PXR 1 and PXR 2. Drug Metab Dispos. 2008;36:923–929. doi: 10.1124/dmd.107.018317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vachirayonsti T, Yan B. MicroRNA-30c-1-3p is a silencer of the pregnane X receptor by targeting the 3′-untranslated region and alters the expression of its target gene cytochrome P450 3A4. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2016.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vadlapatla RK, Vadlapudi AD, Pal D, Mitra AK. Mechanisms of drug resistance in cancer chemotherapy: coordinated role and regulation of efflux transporters and metabolizing enzymes. Current pharmaceutical design. 2013;19:7126–7140. doi: 10.2174/13816128113199990493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van de Winkel A, Menke V, Capello A, Moons LM, Pot RG, van Dekken H, Siersema PD, Kusters JG, van der Laan LJ, Kuipers EJ. Expression, localization and polymorphisms of the nuclear receptor PXR in Barrett’s esophagus and esophageal adenocarcinoma. BMC gastroenterology. 2011a;11:108. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-11-108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van de Winkel A, van Zoest KP, van Dekken H, Moons LM, Kuipers EJ, van der Laan LJ. Differential expression of the nuclear receptors farnesoid X receptor (FXR) and pregnane X receptor (PXR) for grading dysplasia in patients with Barrett’s oesophagus. Histopathology. 2011b;58:246–253. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2011.03743.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkatesh M, Wang H, Cayer J, Leroux M, Salvail D, Das B, Wrobel JE, Mani S. In vivo and in vitro characterization of a first-in-class novel azole analog that targets pregnane X receptor activation. Mol Pharmacol. 2011;80:124–135. doi: 10.1124/mol.111.071787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verma S, Tabb MM, Blumberg B. Activation of the steroid and xenobiotic receptor, SXR, induces apoptosis in breast cancer cells. BMC Cancer. 2009;9:3. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-9-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Huang H, Li H, Teotico DG, Sinz M, Baker SD, Staudinger J, Kalpana G, Redinbo MR, Mani S. Activated pregnenolone X-receptor is a target for ketoconazole and its analogs. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:2488–2495. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Venkatesh M, Li H, Goetz R, Mukherjee S, Biswas A, Zhu L, Kaubisch A, Wang L, Pullman J, et al. Pregnane X receptor activation induces FGF19-dependent tumor aggressiveness in humans and mice. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:3220–3232. doi: 10.1172/JCI41514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang YM, Chai SC, Lin W, Chai X, Elias A, Wu J, Ong SS, Pondugula SR, Beard JA, Schuetz EG, et al. Serine 350 of human pregnane X receptor is crucial for its heterodimerization with retinoid X receptor alpha and transactivation of target genes in vitro and in vivo. Biochem Pharmacol. 2015;96:357–368. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2015.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie W, Barwick JL, Downes M, Blumberg B, Simon CM, Nelson MC, Neuschwander-Tetri BA, Brunt EM, Guzelian PS, Evans RM. Humanized xenobiotic response in mice expressing nuclear receptor SXR. Nature. 2000;406:435–439. doi: 10.1038/35019116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Y, Ke S, Ouyang N, He J, Xie W, Bedford MT, Tian Y. Epigenetic regulation of transcriptional activity of pregnane X receptor by protein arginine methyltransferase 1. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:9199–9205. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806193200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu F, Wang F, Yang T, Sheng Y, Zhong T, Chen Y. Differential drug resistance acquisition to doxorubicin and paclitaxel in breast cancer cells. Cancer cell international. 2014;14:538. doi: 10.1186/s12935-014-0142-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yue X, Akahira J, Utsunomiya H, Miki Y, Takahashi N, Niikura H, Ito K, Sasano H, Okamura K, Yaegashi N. Steroid and Xenobiotic Receptor (SXR) as a possible prognostic marker in epithelial ovarian cancer. Pathol Int. 2010;60:400–406. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.2010.02546.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhan Y, Ginanni N, Tota MR, Wu M, Bays NW, Richon VM, Kohl NE, Bachman ES, Strack PR, Krauss S. Control of cell growth and survival by enzymes of the fatty acid synthesis pathway in HCT-116 colon cancer cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:5735–5742. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-5074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang B, Cheng Q, Ou Z, Lee JH, Xu M, Kochhar U, Ren S, Huang M, Pflug BR, Xie W. Pregnane X receptor as a therapeutic target to inhibit androgen activity. Endocrinology. 2010;151:5721–5729. doi: 10.1210/en.2010-0708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Qiu F, Lu X, Li Y, Fang W, Zhang L, Zhou Y, Yang L, Lu J. A functional polymorphism in the 3′-UTR of PXR interacts with smoking to increase lung cancer risk in southern and eastern Chinese smoker. International journal of molecular sciences. 2014a;15:17457–17468. doi: 10.3390/ijms151017457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Qiu F, Lu X, Li Y, Fang W, Zhou Y, Yang L, Lu J. A functional polymorphism in the 3′-UTR of PXR interacts with smoking to increase lung cancer risk in southern and eastern Chinese smoker. International journal of molecular sciences. 2014b;15:17457–17468. doi: 10.3390/ijms151017457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J, Bai Z, Feng F, Song E, Du F, Shen G, Ji F, Li G, Ma X, Hang X, et al. Cross-talk between EPAS-1/HIF-2alpha and PXR signaling pathway regulates multi-drug resistance of stomach cancer cell. The international journal of biochemistry & cell biology. 2016;72:73–88. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2016.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J, Liu M, Zhai Y, Xie W. The antiapoptotic role of pregnane X receptor in human colon cancer cells. Mol Endocrinol. 2008;22:868–880. doi: 10.1210/me.2007-0197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhuo W, Hu L, Lv J, Wang H, Zhou H, Fan L. Role of pregnane X receptor in chemotherapeutic treatment. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2014;74:217–227. doi: 10.1007/s00280-014-2494-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zucchini N, de Sousa G, Bailly-Maitre B, Gugenheim J, Bars R, Lemaire G, Rahmani R. Regulation of Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL anti-apoptotic protein expression by nuclear receptor PXR in primary cultures of human and rat hepatocytes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005;1745:48–58. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2005.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]