Abstract

The innate immune system provides the first line of defense against pathogens. To recognize pathogens, this system detects a number of molecular features that discriminate pathogens from host cells, including terminal sialylation of cell surface glycans. Mammalian cell surfaces, but generally not microbial cell surfaces, have sialylated glycans. Prions or PrPSc are proteinaceous pathogens that lack coding nucleic acids but do possess sialylated glycans. We proposed that sialylation of PrPSc is essential for evading innate immunity and infecting a host. In this study, the sialylation status of PrPSc was reduced by replicating PrPSc in serial Protein Misfolding Cyclic Amplification using sialidase-treated PrPC substrate and then restored to original levels by replication using non-treated substrate. Upon intracerebral administration, all animals that received PrPSc with original or restored sialylation levels were infected, whereas none of the animals that received PrPSc with reduced sialylation were infected. Moreover, brains and spleens of animals from the latter group were completely cleared of prions. The current work established that the ability of prions to infect the host via intracerebral administration depends on PrPSc sialylation status. Remarkably, PrPSc infectivity could be switched off and on in a reversible manner by first removing and then restoring PrPSc sialylation.

Prion diseases are a family of transmissible neurodegenerative maladies caused by misfolding and aggregation of a cellular sialoglycoprotein called the prion protein or PrPC into a conformationally altered, self-replicating, disease-associated state referred to as PrPSc 1. While prions or PrPSc are not conventional pathogens and lack coding nucleic acids, they can be transmitted effectively via natural routes and characterized by high infectivity titers akin to conventional pathogens2,3,4.

The first line of defense against microbial pathogens in mammals is provided by the innate immune system. To recognize potential pathogens, the innate immune system senses a number of molecular features that discriminate pathogens from host cells. Among them is sialylation, a terminal modification of glycans that is found on all types of mammalian cells, but is absent on most microbial pathogens5,6. To the cells of the innate immune system, sialylated glycans act as part of a “self-associated molecular pattern”, whereas asialoglycans with exposed galactose residues act as part of a “pathogen-associated molecular pattern”5,6. Exposed galactose on carbohydrates is believed to serve as “eat me” signal for professional and non-professional microphages including microglia7,8. PrPC is posttranslationally modified with one or two N-linked glycans, in which terminal sialic acid residues are attached to galactose residues via α2–3 or α2–6 linkages9,10,11. Upon conversion into PrPSc, the N-linked glycans of PrPC are carried over giving rise to sialylated PrPSc 12,13. Previously, we proposed that due to sialylation, PrPSc is not recognized by the innate immune system as a potential pathogen14,15. The current study was designed to test the hypothesis that sialylation represents a key molecular feature that controls infectivity of PrPSc, even when it is administered directly into brain, avoiding any encounter with the innate immune system in the periphery. In particular, we asked whether the infectivity of PrPSc could be switched off and on in a reversible manner by removing and reinstalling sialic acid residues.

In the CNS microglia, astrocytes, endothelial cells and pericytes perform the functions that are fulfilled by the innate immune system in the periphery (reviewed in ref. 16). In the periphery, commensal bacteria that colonize surfaces early in life act in sync with the host innate immune system, helping to prevent invasion of pathogens17,18. In fact, commensal bacteria are believed to calibrate the activation threshold of the innate immune system, ensuring a balanced immune response against pathogens but not against self17,18. Because the CNS lacks direct exposure to commensal bacteria, it is not clear whether the defense mechanisms of the innate immune system that evolved to rely on sialylation or its lack thereof are also applicable to the CNS.

To test the above hypothesis, the current study used SSLOW, a prion strain of synthetic origin19. Just like other prion strains, SSLOW is transmissible, displays a high infectivity titer and causes neuronal loss, gliosis and spongiform vacuolation4,20,21. It is deposited in the form of large plaques and small synaptic and perineuronal deposits19,20,21. Previously, SSLOW deposits were found in association with neuronal and glial cells19,20,21. However, in contrast to the vast majority of rodent strains, including 263 K or Hyper, SSLOW exhibits a long incubation time to disease and slow progression of the clinical disease20, which is more typical of human and large animal Transmissible Spongiform Encephalopathies than those of rodents. In addition, SSLOW-infected animals showed substantial cerebral amyloid angiopathy19,21, a pathogenic feature often observed in a subset of individuals with Alzheimer’s disease. SSLOW replicates very efficiently in Protein Misfolding Cyclic Amplification with beads (PMCAb)22,23, making the production of SSLOW with modified sialylation status in vitro or detection of miniscule amounts of SSLOW PrPSc in animal tissues feasible.

To modify the sialylation status of SSLOW PrPSc, the current work employed serial PMCAb conducted with normal brain homogenate (NBH) in which the sialylation status of PrPC was first reduced using sialidase treatment and then restored to the original level by propagating using non-treated NBH. We found that the ability of PrPSc to infect animals via intracerebral (IC) administration depended on the PrPSc sialylation status. Remarkably, we showed that the infectivity of SSLOW PrPSc could be switched off and on in a reversible manner by removing and then restoring PrPSc sialylation, respectively. This study suggests that controlling sialylation status of PrPSc might open new opportunities for therapeutic intervention against prion diseases.

Results

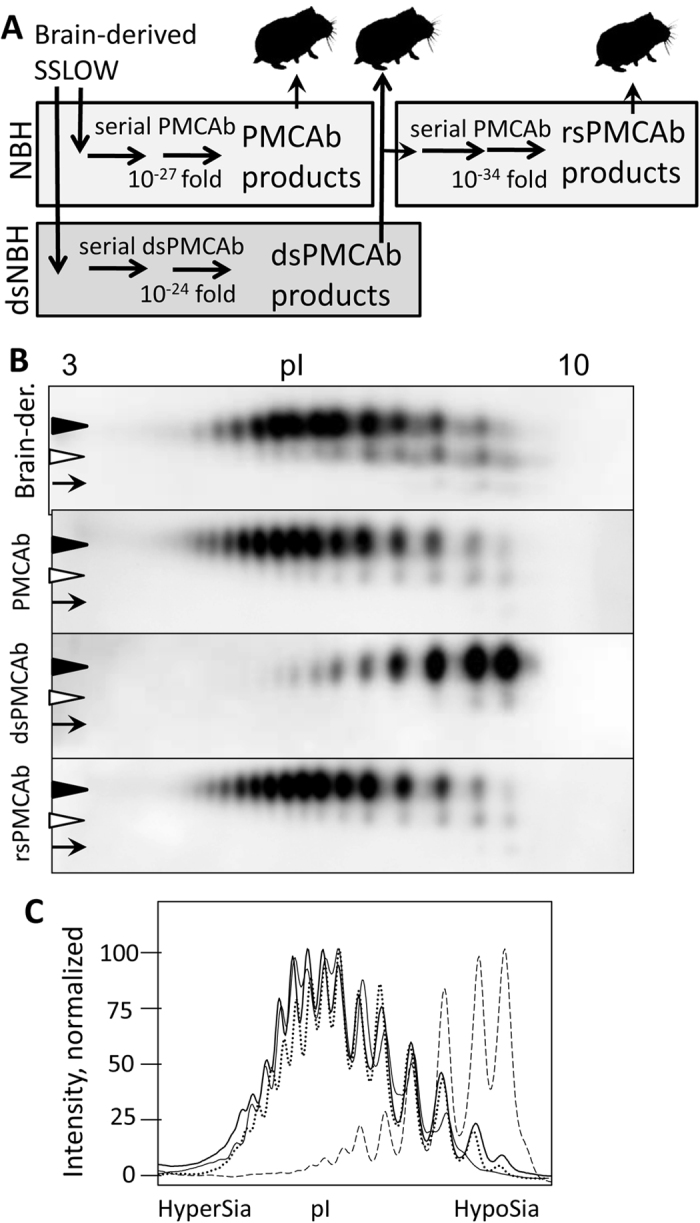

Previous studies established that within brain-derived PrPSc, PrP molecules are highly heterogeneous with respect to sialylation status of their N-linked glycans ranging from hyposialylated to hypersialylated14,24,25. To produce PrPSc with reduced sialylation status, serial PMCAb reactions were seeded with brain-derived SSLOW PrPSc, and sialidase-treated normal brain homogenate (dsNBH) was used as a source of PrPC (Fig. 1A). The resulting material produced in dsNBH will be referred to as dsPMCAb-derived SSLOW. Direct treatment of brain-derived PrPSc with sialidase was not effective, presumably due to the highly aggregated nature of PrPSc and limited access of sialic acid residues to sialidases. To produce a reference PMCAb-derived SSLOW, serial PMCAb reactions were seeded with brain-derived SSLOW PrPSc, and the reactions were conducted using NBH as a substrate in the absence of sialidase treatment. Multiple serial rounds were conducted for both dsPMCAb and PMCAb reactions to make sure that the final dilutions of the original SSLOW seeds in dsPMCAb or PMCAb products were well beyond the limiting dilution (Fig. 1A). To restore the sialylation status of dsPMCAb-derived SSLOW, serial PMCAb reactions were seeded with dsPMCAb-derived SSLOW and subjected to replication in NBH (Fig. 1A). The resulting material will be referred to as resialylated or rsPMCAb-derived SSLOW.

Figure 1. Experimental design and 2D analysis of sialylation status.

(A) Experimental design illustrating generation of desialylated and re-sialylated SSLOW material. To produce desialylated SSLOW, serial dsPMCAb reactions were seeded with brain-derived SSLOW and conducted using sialidase-treated NBH to a final dilution of SSLOW brain material of 10−24-fold. To produce re-sialylated SSLOW, serial rsPMCAb was seeded with dsPMCAb products and conducted using non-treated NBH to a final dilution of original SSLOW brain material 10−34-fold. To produce reference PMCAb-derived material, serial PMCAb reaction was seeded with brain-derived SSLOW and conducted using non-treated NBH to a final dilution of SSLOW brain material 10−27-fold. Animals were inoculated IC with 10-fold diluted PMCAb, dsPMCAb- or rsPMCAb-derived material. (B) 2D Western blot analysis of SSLOW brain-, PMCAb-, dsPMCAb- and rsPMCAb-derived material. Black and white triangles mark diglycosylated and monoglycosylated glycoforms, respectively, whereas arrows mark the unglycosylated form. All blots were stained with 3F4 antibody. (C) Sialylation profiles of diglycosylated isoforms of SSLOW brain- (solid thin line), PMCAb- (solid bold line), dsPMCAb- (dashed line) and rsPMCAb-derived material (dotted line). Profiles were built as described in Materials and Methods using results of 2D Western blots.

The sialylation status of the original brain-derived SSLOW, as well as PMCAb-, dsPMCA- and rsPMCA-derived SSLOW, was assessed using two-dimensional Western blot (2D). Prior to 2D, all samples were treated with PK, and then the PrPSc aggregates were denatured into PrP monomers. The sialylation status of individual PrP molecules is reflected by their positions on the horizontal dimension of 2D, where heavily sialylated PrPs run toward acidic pHs, whereas weakly sialylated ones run toward basic pHs. Brain-, PMCAb- and rsPMCA-derived SSLOW showed a very similar distribution of charge isoforms, confirming the very similar sialylation status of PrPSc in these three materials (Fig. 1B,C). All three samples showed a broad sialylation pattern with considerable predominance of highly sialylated isoforms. Notably, the sialylation of rsPMCA-derived SSLOW was restored to the levels characteristic of brain- or PMCAb-derived SSLOW. As expected, the sialylation level of dsPMCA-derived SSLOW was substantially lower in comparison to those of brain-, PMCAb- or rsPMCA-derived SSLOW (Fig. 1B,C).

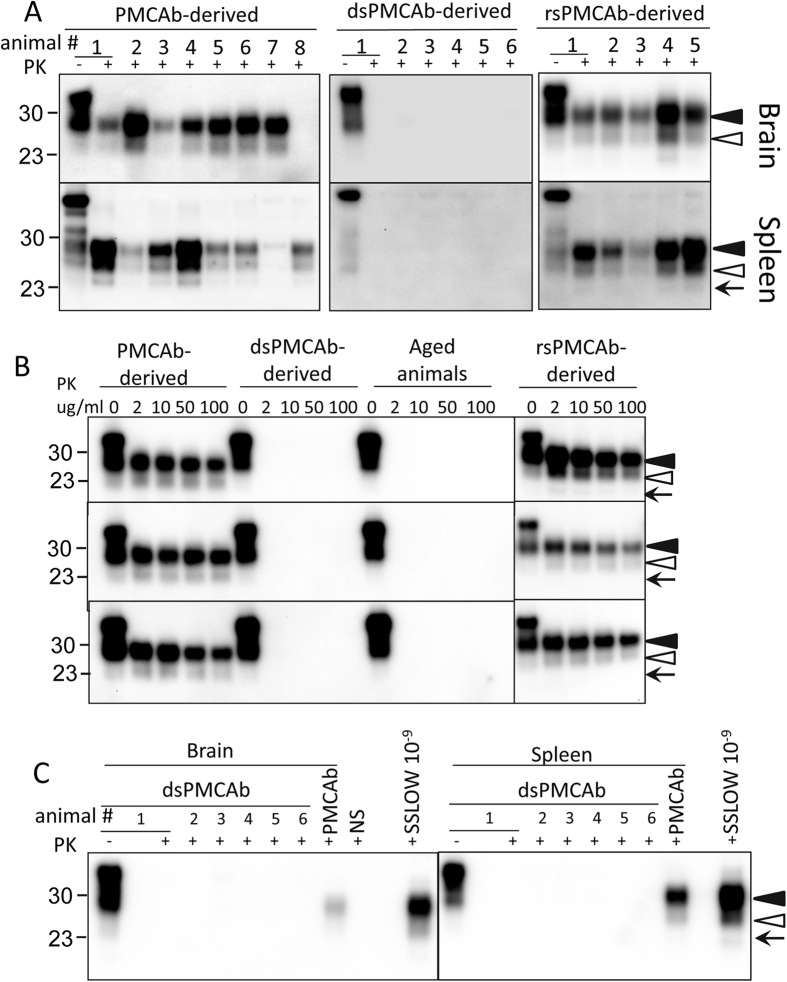

Syrian hamsters were inoculated IC with brain-, PMCAb-, dsPMCAb- or rsPMCA-derived SSLOW. The amounts of PK-resistant material in the 10-fold diluted PMCAb-, dsPMCAb- or rsPMCAb-derived samples used for inoculation was higher than the amounts of PrPSc in 104-fold diluted but lower than that in 103-fold diluted SSLOW brain material (Supplementary Figure 1). Both 103-fold and 104-fold diluted SSLOW brain material was used as references. All animals inoculated with brain-derived SSLOW developed clinical signs of disease typical for SSLOW (listed in Materials and Methods) and progressed to the terminal stage by 503–609 days post inoculation, at which time they were euthanized (Table 1). All animals showed slow progression of clinical disease typical for the SSLOW strain. None of the animals inoculated with PMCAb-, dsPMCAb- or rsPMCA-derived SSLOW showed obvious clinical signs and were euthanized at 614 or 621 days post inoculation (Table 1). Nevertheless, analysis of brain and spleen materials revealed that animals inoculated with PMCAb- or rsPMCAb-derived SSLOW were PrPSc-positive as judged by the presence of a PK-resistant signal on Western blot. In the group inoculated with PMCAb-derived SSLOW, seven out of eight animals showed PrPSc in their brain and all eight animals had PrPSc in their spleen (Fig. 2A, Table 1). Brains and spleens from all five animals inoculated with rsPMCAb-derived SSLOW were positive for PrPSc (Fig. 2A, Table 1). In contrast, none of the six animals inoculated with dsPMCA-derived SSLOW showed PrPSc signal in their brains or spleens.

Table 1. Bioassay of SSLOW samples in golden Syrian hamsters.

| SSLOW inocula | ns/nt* | nPrPSc/nt** brain | nPrPSc/nt** spleen | Euthanized at days post-inoculation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 103 fold diluted brain-derived | 7/7 | 7/7 | N/A | 503, 503, 503, 503, 503, 591, 609 |

| 104 fold diluted brain-derived | 7/7 | 7/7 | N/A | 504, 540, 551, 552, 556, 560, 577 |

| PMCAb-derived | 0/8 | 7/8 | 8/8 | 621 |

| dsPMCAb-derived | 0/6 | 0/6 | 0/6 | 614 |

| rsPMCAb-derived | 0/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | 614 |

*Number of animals with clinical signs (ns) over the total number of animals (nt) that survived to the end of the experiment.

**Number of animals with PrPSc in brain homogenates or spleen homogenates (nPrPSc) over the total number of animals survived to the end of the experiment (nt).

Figure 2. Analysis of brains and spleens from animals inoculated with SSLOW PMCAb-, dsPMCAb- or rsPMCAb-derived materials.

Syrian hamsters were inoculated IC with 10-fold diluted PMCAb-, dsPMCAb- or rsPMCAb-derived material. (A) Brain or spleen homogenates were treated with PK and analyzed by Western blot. (B) Western blots of brain homogenates from animals inoculated with PMCAb-, dsPMCAb- or rsPMCAb-derived material or non-inoculated animals 600–670 days old. Brain homogenates were treated with increasing concentrations of PK as indicated. PK-digestion profiles for three independent animals are shown. (C) Serial PMCAb reactions were seeded with 10% brain or spleen homogenates from hamsters inoculated with dsPMCAb- or PMCAb-derived material, subjected to four serial rounds and reaction products were analyzed by Western blot. As positive controls, serial PMCAb reactions were seeded with 109-fold diluted SSLOW brain material. As a negative control for cross-contamination, non-seeded serial PMCAb reactions were conducted in parallel (NS). Lane “PMCAb” refers to PMCAb reactions seeded with brain and spleen tissue from animal #8 in panel A “PMCAb-derived”. Independent serial PMCAb reactions were repeated twice for each samples and produced identical results. Black and white triangles mark diglycosylated and monoglycosylated glycoforms, respectively, whereas arrows mark the unglycosylated form. All blots were stained with 3F4 antibody.

Lack of a signal in the group inoculated with dsPMCAb-derived SSLOW could be due to changes in strain properties and accumulation of predominantly PK-sensitive PrPSc. To test this possibility, brain materials from PMCAb, dsPMCAb and rsPMCA animal groups, as well as normal animals 600–670 days of age, were treated with increasing concentrations of PK starting at 2 μg/ml. As expected, animals from PMCAb and rsPMCA groups showed a consistent signal in the whole range of PK concentrations tested, from 2 μg/ml to 100 μg/ml (Fig. 2B). In contrast, no signal was detected in brains from the dsPMCAb group or brains of aged animals even at the lowest concentration of PK (Fig. 2B). In fact, the PK-resistance profile was indistinguishable between dsPMCAb-inoculated animals and the normal aged group.

To test whether miniscule amounts of PrPSc undetectable by Western blot were present in the animals inoculated with dsPMCA-derived SSLOW, brain and spleen materials from this group were subjected to serial PMCAb. Previously, serial PMCAb or PMCA was shown to be capable of detecting single PrPSc particles in several strains, including SSLOW4,26,27. In parallel, brain and spleen material from animal #8 in the group inoculated with PMCAb-derived SSLOW was also subjected to serial PMCAb. Serial PMCAb reactions seeded with 109-fold diluted SSLOW brain material were used as a positive control, whereas non-seeded reactions were conducted as negative controls. Four serial rounds of PMCAb were performed according to the protocol that we previously determined to be sufficient for detecting limiting dilutions of SSLOW4. As expected, 109-fold diluted SSLOW brain material, as well as the brain and spleen materials from the animal #8 inoculated with PMCAb-derived SSLOW, all showed positive signals after serial PMCAb (Fig. 2C). These results confirmed that animal #8 was infected and that limiting dilutions of SSLOW could be detected. In contrast, brains and spleens from all six animals inoculated with dsPMCA-derived SSLOW were negative on Western blot after serial PMCAb (Fig. 2C). This result established that in the animals inoculated with dsPMCA-derived SSLOW, any detectible prion infection was cleared. Taken together, these data suggest the ability to infect a host strongly depends on the sialylation status of PrPSc.

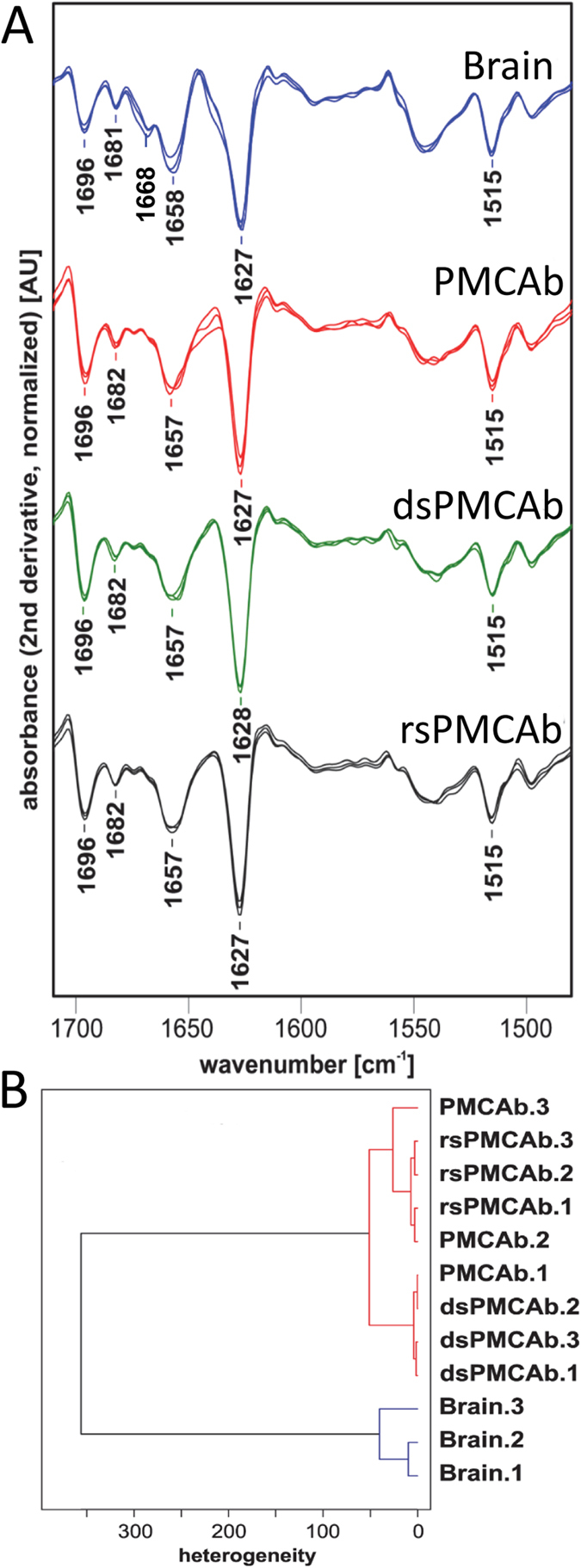

Theoretically, reversible changes of the PrPSc secondary or tertiary structure during dsPMCAb and rsPMCAb could account for the loss and restoration of infectivity, respectively. In fact, previous studies that employed infrared microscopy revealed conformational differences between 263K scrapie brain material and 263K-seeded PMCA-derived products28. To test whether this is the case, PrPSc was purified from SSLOW brain-, PMCAb-, dsPMCAb- and rsPMCAb-derived materials and analyzed by infrared microspectroscopy (IR-MSP). Brain-derived SSLOW showed a peak at 1627 cm−1 that corresponds to a β-sheet rich conformation, a small peak at 1696 cm−1 that also reports on β-sheet structures and a peak at 1658 cm−1 which is conventionally assigned to an α-helical conformation (Fig. 3A). The association between specific IR absorption bands at 1658 cm−1 and α-helical structure elements in PrPSc is currently under discussion29. Analysis of PMCAb-derived materials confirmed that subtle structural changes occurred in PrPSc during serial amplification. Specifically, the minor peak visible in brain-derived SSLOW at 1668 cm−1 disappeared in PMCAb-, dsPMCAb- and rsPMCAb SSLOW. (Figure 3A). Remarkably, the spectra of PMCAb-, dsPMCAb- and rsPMCAb-derived SSLOW were undistinguishable between each other illustrating that PrPSc structure is not altered by the changes in sialylation status. Nevertheless, to determine whether very minor structural differences between PMCAb, dsPMCAb and rsPMCAb groups exist, hierarchical cluster analysis was performed (Fig. 3B). Previously, the hierarchical cluster analysis was found to be very helpful in detecting similarities or dissimilarities in the conformation sensitive amide I region of IR spectra of prion strains, isolates or their PMCA derivatives that were not obvious by visual inspection of spectra28,30. The analysis revealed two main clusters: spectra of three SSLOW brains belong to one cluster, whereas all spectra of PMCAb-, dsPMCAb- and rsPMCAb-derived materials formed another cluster. While the structural differences between the two clusters were clearly noticeable, the structural heterogeneity between PMCAb-, dsPMCAb- and rsPMCAb-derive products were of the same degree as heterogeneity between three SSLOW brains. In summary, IR-MSP and cluster analysis demonstrated that minor conformational changes in PrPSc structure did, indeed, occur during PMCAb and might account for some loss of infectivity in PMCAb-derived SSLOW when compared to the brain-derived SSLOW. However, the lack of notable structural differences between PMCAb-, dsPMCAb- and rsPMCAb-derived SSLOW PrPSc argues that the conformation of amplification products was not affected by sialylation status.

Figure 3. Assessing secondary structure by infrared microspectroscopy.

(A) IR spectra obtained from PrPSc material purified from brains of three Syrian Hamster infected with SSLOW (blue), or PMCAb- (red), dsPMCAb- (green) or rsPMCAb-derived SSLOW (black). IR spectra were collected for products of three independent reactions for each format, PMCAb, dsPMCAb or rsPMCAb. Each spectrum represents a min/max normalized (tyrosine band at 1515 cm−1) second derivative spectrum obtained by averaging ten individual point spectra. (B) Dendrogram analysis of conformational heterogeneity of SSLOW PrPSc material purified from brains of animals infected with SSLOW or PMCAb, dsPMCAb, or rsPMCAb reactions (n = 3 independent brains or reactions). Dendrogram obtained by hierarchical cluster analysis of the mean microspectra using the information content in the amide I region (1620–1690 cm−1), using the D value as the interspectral distance measure, and Ward’s algorithm as the clustering method.

Discussion

The current study supports the hypothesis that the ability of prions to infect a host is controlled by the sialylation status of PrPSc 14,15. According to this hypothesis removal of terminal sialic acid residues exposes galactose that serves as an “eat me” signal for macrophages and microglia15. Both PMCAb and rsPMCAb-derived materials infected the host as judged by presence of PrPSc in brain and spleen, whereas animals inoculated with dsPMCAb-derived material showed no signs of prion infection. The possibility exists that dsPMAb material produced a new prion strain characterized by deposition of predominantly PK-sensitive PrPSc and lacked clinical symptoms. However, this hypothesis was not supported by the experiment that employed low concentrations of PK. In fact, the PK resistance profiles of brain material from the dsPMCAb group and aged animals were identical. Moreover, considering that PMCAb, dsPMAb and rsPMCAb material all showed indistinguishable PrPSc conformations, the notion that dsPMCAb material results in a new strain different from that of PMCAb and rsPMCAb would challenge the current paradigm regarding the relationship between PrPSc structure and strain identity. Because the SSLOW materials produced in PMCAb, dsPMAb or rsPMCAb all showed indistinguishable conformations, regardless of their sialylation status, the loss of infectivity of dsPMCAb-derived SSLOW can be attributed to its reduced sialylation status. Remarkably, the loss of infectivity could be restored to the level observed for PMCAb-derived SSLOW, when the sialylation of dsPMCAb-derived SSLOW was restored in rsPMCAb reactions to the level typical for PMCAb-derived products. This result established a cause-and-effect relationship between sialylation status of PrPSc and its infectivity. These findings open new opportunities for therapeutic intervention via manipulating metabolic pathways that regulate the sialylation status of PrPSc.

Previous studies produced highly infectious PrPSc in vitro using recombinant PrP31,32,33. Because entire N-linked glycans were missing in PrPSc produced from recombinant PrP, the “eat me” signal in the form of exposed galactose was also missing. For this reason, it is unlikely that the innate immune system and/or microglia could identify PrPSc of synthetic origin as potential pathogens in the same manner as it might deal with asialo-PrPSc with displays an “eat me” signal. Notably, lack of PrPSc in spleens from the dsPMCAb group observed in the current study suggests that PrPSc with reduced sialylation status did not spread to SLOs or that it spread there but was effectively neutralized by the immune system.

The infectivity of PMCAb-derived SSLOW was lower in comparison to the brain-derived SSLOW. The decline in prion infectivity during serial PMCAb or PMCA reactions was observed in previous studies14,34. As documented by IR-MSP, this loss could be attributed to the changes in PrPSc conformation, even though these were found to be very subtle (Fig. 3A). Nevertheless, even modest differences were sufficient to prolong the incubation time to disease beyond the animal’s normal life span (Table 1). Similar trends in structure and infectivity were previously observed for 263 K subjected to serial PMCA or PMCAb14,28. Shifting the conformation of PrPSc via PMCAb might offer a valuable approach for defining elements of PrPSc structure essential for prion infectivity in future studies.

The long incubation time associated with SSLOW strain, together with a decline in infectivity attributed to PMCAb procedure, poses a couple of questions regarding the extent to which sialylation controls prion infectivity. Would desialylation work to the same extent for a strain with a short incubation time? Would desialylation completely destroy the infectivity of scrapie material with a high infectivity titer? Our previous studies conducted with 263K, for which the incubation time ranges from 60 to ~170 days depending on the dose35, displayed similar effects. No clinical diseases or PrPSc were found in animals inoculated IC with dsPMCAb-derived 263K for at least 342 days post infection, when animals were euthanized14. The second question would be difficult to address until a novel approach for generating desialylated PrPSc is developed. We found that treatment of non-denatured PrPSc with commercially available sialidases was not effective with respect to desialylation presumably due to the aggregated nature of the scrapie material.

Sialylation of glycoproteins in a cell is controlled by two groups of enzymes sialyltransferases and sialidases36,37. Because PrPSc arises from PrPC via changes in its conformation, manipulating the sialylation status of PrPC offers the primary mechanism by which sialylation of PrPSc could be controlled. Our previous work demonstrated that knocking out sialidases that are expressed in CNS (Neu1, Neu3 or Neu4) or application of general sialidase inhibitors did not change the steady-state sialylation levels of PrPC in brain or cultured cells, respectively38. These data suggest that desialylated PrPC molecules are degraded very fast and do not contribute to the steady-state pool of PrPC. In contrast, a general inhibitor of sialyltransferases was found to reduce the sialylation levels of PrPC in N2a cells, suggesting that manipulating the activity of sialyltransferases offers a more effective strategy than that of sialidases for controlling sialylation status of PrPC 38. The second mechanism that defines the sialylation status of PrPSc is strain-specific and involves selective recruitment of sialoglycoforms of PrPC by PrPSc 24. Our recent studies revealed that heavily sialylated PrPC was preferentially excluded from conversion, and the degree of exclusion was strain-specific24,39. The structure of PrPSc appears to define the maximum density of sialic acid residues that can be accommodated within given strain-specific structures. The third mechanism is related to the tissue-specific differences in sialylation levels of PrPSc 25. Regardless of prion strain, PrPSc deposited in secondary lymphoid organs was found to be more sialylated than brain-derived PrPSc 25. Enhanced sialylation of spleen-derived PrPSc was attributed to post-conversion sialylation, i.e. direct sialylation of PrPSc by sialyltransferases25.

Sialylation along with other molecular cues is used by the mammalian innate immune system for discriminating “self” from “non-self” or “altered self”5,6. The surfaces of all mammalian cell types are covered with sialic acid residues40, which act as a part of “self-associated molecular pattern”. In contrast, the majority of microbial pathogens lack sialic acid residues on their glycans, which instead leave galactose exposed5,6. Terminal galactoses serve as part of a “pathogen-associated molecular pattern” generating “eat me” signals for professional and non-professional macrophages5. Moreover, a decline in the density of sialic residues on cell surfaces represents one of the molecular signatures of “apoptotic-cell-associated molecular patterns” observed in apoptotic or aging cells41,42. Erythrocytes and platelets that lose sialic acid residues due to aging are phagocytosed by Kupffer cells43,44. The functions fulfilled by the cells of innate immune system in the periphery are performed in CNS by microglia, astrocytes, endothelial cells and other cell types16. Recent studies showed that neurites with reduced surface sialylation are opsonized by the complement component C1q and cleared by microglia, whereas sialylation of neurites inhibited complement-mediated clearance7,8.

To fulfill its function, the innate immune system involves diverse mechanisms and relies on several classes of molecules, which recognize sialo- or asialoglycanson cell surfaces. Asialoglycoprotein receptors are expressed by Kupffer cells and microglia and bind glycans with exposed terminal galactoses, helping to clear aged cells or asialoglycoprotein complexes45. Galectins, a family of secreted protein receptors, are expressed in the periphery and CNS and recognize complex patterns composed of sialo- or asialo-glycans46. An alternative mechanism that relies on glycan recognition involves the lectin pathway of the complement system that include factors C1q and C347. Both C1q and C3 are expressed in a brain by glial and neuronal cells48,49. While the complement system is supposed to defend against pathogens, C1q and C3 were found to assist in the trafficking and accumulation of prions in secondary lymphoid organs at early stages of infection upon administration of prions via peripheral routes50,51. Genetic or pharmacological depletions of C3 or its receptor CD21/35 were found to prolong incubation time to disease50,51,52,53. Nevertheless, the role of C1q and C3 in sporadic prion disease or diseases transmitted via the IC route is not clear. Upon administration of prions IC, C1q and C3 were found to be expressed at high levels in brain during disease progression and were shown to be associated with neurons, astrocytes and microglia48. However, factor H balances overstimulation of the complement system by binding to terminal sialic acids and conferring protection to healthy mammalian cells by preventing over activation of C1q47,54. It would be important to determine if any of these known mechanisms are involved in the lack of infectivity of PrPSc with low sialylation levels in future studies.

Conclusions

The current work established that the ability of prions to infect a host via IC administration crucially depends on the PrPSc sialylation status. Remarkably, PrPSc infectivity could be switched off and on in a reversible manner by removing and reinstalling PrPSc sialylation, respectively. In the periphery, sialylation acts as a part of a “self-associated molecular pattern” helping the immune system to recognize cells of mammalian organism and set them apart from pathogens. The current work suggests that cells that perform the functions of the innate immune system in the CNS utilize a similar sialylation-based strategy for discriminating between “self” and “non-self”.

Methods

Ethics statement

This study was carried out in strict accordance with the recommendations in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the National Institutes of Health. The animal protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Maryland, Baltimore (Assurance Number A32000-01; Permit Number: 0215002).

Protein misfolding cyclic amplification with beads (PMCAb)

10% normal brain homogenate (NBH) from healthy hamsters was prepared as described previously55. To produce desialylated substrates, 10% NBH was treated with Arthrobacter ureafaciens (cat #P0722L, New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA) sialidase that has broad substrate specificity, as follows. After preclearance of NBH at 500 × g for 2 min, the enzyme buffer supplied by the manufacturer was added to the supernatant using manufacturer’s instructions, followed by 200 units/mL of sialidase, and incubated on a rotator at 37 °C for 5 h. The resulting material is referred to as dsNBH substrate used in dsPMCAb, a PMCAb format conducted using dsNBH.

PMCAb and dsPMCAb reactions were conducted as previously described14,22, using a Misonix S-4000 microplate horn (Qsonica LLC, Newtown, CT) in the presence of two 2/32″ Teflon beads in each tube (McMaster-Carr, Elmhurst, IL). Both types of reactions were seeded with 103-fold diluted SSLOW scrapie brain homogenates. To produce PMCAb-derived material, 24 serial rounds with 10-fold dilution between rounds were conducted using NBH as a substrate. To produce dsPMCAb material, 7 serial rounds with 1,000-fold dilution between rounds were conducted with dsNBH substrate. To produce resialylated SSLOW PrPSc, 10 serial rounds with 10-fold dilution between rounds were conducted using NBH as a substrate and dsPMCAb-derived SSLOW as seeds (this reaction format will be referred to as resialylated or rsPMCAb). Prior to inoculation, PMCAb-, dsPMCAb- and rsPMCAb-derived products were diluted an additional 10-fold.

To test for the presence of PrPSc in the brains or spleens of hamsters inoculated with PMCAb- and dsPMCAb-derived materials, 90 μl of substrate was supplied with two 2/32″ Teflon beads and seeded with 10 μl of 10% brain or spleen homogenates. Four serial rounds were conducted with 10-fold dilution of the reaction products into fresh substrate between rounds. 109-fold diluted 10% brain homogenate from a hamster terminally ill with SSLOW was used as a positive control and non-seeded serial PMCAb reactions as negative controls. In all PMCAb, dsPMCAb or rsPMCAb reactions, one round consisted of 20 sec sonication pulses delivered at 170 W energy output applied every 20 min during a 24 hour period.

Animal bioassay

Weanling Golden Syrian hamsters were inoculated IC with 50 μl 103- and 104-fold diluted SSLOW scrapie brain homogenates, 10-fold diluted PMCAb, dsPMCAb or rsPMCAb-derived materials under 2% O2/4 minimum alveolar concentration (MAC) isoflurane anesthesia. After inoculation, animals were observed daily for disease using a ‘blind’ scoring protocol and euthanized at the terminal stage of disease. The following symptoms typical for SSLOW were observed in animals inoculated with SSLOW brain material: a non-habituating startle response to sound and touch; an agitated, fidgeting behavior; pear shaped body; increasingly squat, paddling gait; and dry, patchy and shedding hair. After the first symptoms were observed, it took 80–120 days for the diseases to progress to a terminal stage. Animals that did not develop clinical signs of disease were euthanized at 614 or 621 days post inoculation (Table 1).

2D Western blotting

Samples of 25 μL prepared in loading buffer as described in “Western blot” section below were solubilized for 1 h at room temperature in 200 μL solubilization buffer (8 M Urea, 2% (wt/vol) CHAPS, 5 mM TBP, 20 mM Tris pH 8.0), alkylated by adding 7 μL of 0.5 M iodoacetamide and incubated for 1 h at room temperature. Then, 1150 μL of ice-cold methanol was added, and samples were incubated for 2 h at −20 °C. After centrifugation at 16,000 g at 4 °C, supernatant was discarded, and the pellet was re-solubilized in 160 μL rehydration buffer (7 M urea, 2 M thiourea, 1% (wt/vol) DTT, 1% (wt/vol) CHAPS, 1% (wt/vol) Triton X-100, 0.4% (vol/vol) ampholyte, trace amount of Bromophenol Blue). Fixed pre-cast IPG (immobilized pH gradient) strips (cat. #ZM0018, Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) with a linear pH gradient 3–10 were rehydrated in 155 μL of the resulting mixture overnight at room temperature inside IPG Runner cassettes (cat. #ZM0003, Life Technologies). Isoelectrofocusing (first dimension separation) was performed at room temperature with rising voltage (175 V for 15 minutes, then 175–2,000 V linear gradient for 45 minutes, then 2,000 V for 30 minutes) with a Life Technologies Zoom Dual Power Supply, using the XCell SureLock Mini-Cell Electrophoresis System (cat. #EI0001, Life Technologies). The IPG strips were then equilibrated for 15 minutes consecutively in (i) 6 M Urea, 20% (vol/vol) glycerol, 2% SDS, 375 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.8, 130 mM DTT and (ii) 6 M Urea, 20% (vol/vol) glycerol, 2% SDS, 37 5 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.8, 135 mM iodoacetamide and loaded on 4–12% Bis-Tris ZOOM SDS-PAGE pre-cast gels (cat. #NP0330BOX, Life Technologies). For the second dimension, SDS-PAGE in MES-SDS buffer (cat. # B0002, Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) was performed for 1 h at 170 V. Immunoblotting was performed as described elsewhere and stained using 3F4 antibody (cat. #SIG-39600, Covance).

2D Western blot signal intensity was digitized for densitometry analysis using AlphaView software (ProteinSimple, San Jose, CA). For generating sialylation profiles for diglycosylated isoforms, densitometry analysis of 2D blots was performed using the “Lane profile” function in the AlphaView program, the highest curve signal value was taken as 100%.

Procedure for purification of scrapie material

Extraction of PrPSc from brain tissue, PMCAb, dsPMCAb and rsPMCAb reactions for FTIR microspectroscopic analysis were performed as described by Daus et al.28 with the following modifications for brain tissue: hemispheres of mid-sagitally split hamster brains (approximately 0.5 g) were each homogenizedin 10 ml of homogenization buffer. Brain tissue homogenates were subjected to the extraction procedure, and five final pellets of highly purified PrPSc were obtained from one hemisphere. For infrared spectroscopic analysis final PrPSc pellets were washed as described28 and resuspended in 10 μl of double-distilled H2O. 1 μl aliquots of these PrPSc suspensions were transferred for drying onto a CaF2 window of 1 mm thickness (Korth Kristalle GmbH, Altenförde, Germany).

Infrared microspectroscopy

For brain-, PMCAb-, dsPMCAb- and rsPMCAb-derived scrapie material, three independent preparations each were obtained and characterized by infrared microspectroscopy (IR-MSP). IR-MSP measurements were carried out as previously described28. Briefly, mid-IR spectra were acquired in transmission mode using an IFS 28/B FT-IR spectrometer from Bruker (Bruker Optics GmbH, Ettlingen Germany) that was linked to an IRscope II infrared microscope (Bruker). IR microspectra were recorded with a spatial resolution of approximately 80 μm. Nominal spectral resolution was 4 cm−1, and the zero filling factor was 4. For each background and for each sample spectrum, 512 individual interferograms were averaged and apodized using a Blackman-Harris 3-term apodization function. To attain an improved signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) and to address the aspect of within-sample heterogeneity, 10 point spectra were acquired and averaged per purified PrPSc sample. Data acquisition and spectral preprocessing was carried out by utilizing Bruker’s instrument software OPUS v. 5.5. Second derivative spectra were obtained by means of a 9-smoothing point Savitzki-Golay derivative filter. All derivative spectra were min/max normalized to the tyrosine band at 1515 cm−1.

Cluster analysis

Unsupervised hierarchical cluster analysis was used to reveal groupings in the IR microspectra. The analysis was performed using the cluster analysis function of the OPUS data acquisition software with mean spectra from three independent preparations for each group as inputs. Pre-processing of the mean spectra involved application of a Savitzky-Golay second derivative filter with 13 smoothing points56. Inter-spectral distances were calculated using the information from the secondary structure-sensitive amide I region (1620 and 1690 cm−1) as so-called D-values - scaled Pearson’s correlation coefficients57 - while Ward’s algorithm58 was used for hierarchical clustering.

Proteinase K digestion and Western blot

10 μL of 10% spleen homogenates or 1% brain homogenates were mixed with an equal volume of 4% sarcosyl in PBS, supplemented with 50 mM Tris, pH 7.5, and digested with 25 μg/ml PK (cat. #P8107S, New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA) for 30 min at 37 °C. 10 μL aliquots of PMCAb-, dsPMCAb- or rsPMCAb-derived materials were supplemented with 5 μL 1% SDS and 5 μL PK to final concentrations of 0.25% SDS and 25 μg/mL PK, and incubated at 37 °C for 1 hour. Then, SDS sample buffer was added, samples were boiled for 10 minutes and loaded onto NuPage 12% BisTris gel (cat. #NP0341BOX, Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA), then transferred to PVDF membrane, and probed with 3F4 (cat. #SIG-39600, Covance).

To analyze sensitivity to PK, 10% brain homogenates were diluted 10-fold with 2% sarcosyl in PBS and supplied with increasing concentrations of PK to final concentrations of 0, 2, 10, 50 or 100 μg/ml. After incubation with shaking at 37 °C for 30 min, the reactions were stopped by addition of 4x SDS-sample buffer and boiling the samples for 10 min. Samples were loaded onto NuPAGE 12% BisTris gels, transferred to PVDF membrane, and detected with 3F4 antibody.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Katorcha, E. et al. Reversible off and on switching of prion infectivity via removing and reinstalling prion sialylation. Sci. Rep. 6, 33119; doi: 10.1038/srep33119 (2016).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Pamela Wright for editing the manuscript. Financial support for this study was provided by National Institute of Health Grants R01 NS045585 and R01 NS074998.

Footnotes

Author Contributions I.V.B. and E.K. conceived the idea and designed the experiments; E.K., M.L.D., N.G.-M., N.M., P.L. and M.B. performed experiments; E.K., M.L.D., P.L., M.B. and I.V.B. analyzed the data; I.B.V. wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

References

- Prusiner S. B. Novel proteinaceous infectious particles cause scrapie. Science 216, 136–144 (1982). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller M. W. & Williams E. S. Chronic wasting disease of cervids. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 284, 193–214 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown P. & Gajdusek D. C. The human spongiform encephalopathies: kuru, Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, and the Gerstmann-Sträussler-Scheinker syndrome. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 172, 1–20 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makarava N., Savtchenko R., Alexeeva I., Rohwer R. G. & Baskakov I. V. Fast and ultrasensitive method for quantitating prion infectivity titer. Nature Commun. 3, 741 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varki A. Sialic acids in human health and disease. Trends in Molecular Medicine 14, 351–360 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varki A. Since there are PAMPs and DAMPs, there must be SAMPs? Glycan “self-associated molecular patterns” dampen innate immunity, but pathogens can mimic them. Glycobiology 21, 1121–1124 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linnartz B., Kopatz J., Tenner A. J. & Neumann H. Sialic acid on the neuronal glycocalyx prevents complement C1 binding and complement receptor-3-mediated removal by microglia. J. Neurosci 32, 946–952 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linnartz-Gerlach B., Schuy C., Shahraz A., Tenner A. J. & Neumann H. Sialylation of neurites inhibits complement-mediated macrophage removal in a human macrophage-neuron Co-Culture System. Glia 64, 35–47 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turk E., Teplow D. B., Hood L. E. & Prusiner S. B. Purification and properties of the cellular and scrapie hamster prion proteins. Eur J Biochem 176, 21–30 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endo T., Groth D., Prusiner S. B. & Kobata A. Diversity of oligosaccharide structures linked to asparagines of the scrapie prion protein. Biochemistry 28, 8380–8388 (1989). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stimson E., Hope J., Chong A. & Burlingame A. L. Site-specific characterization of the N-linked glycans of murine prion protein by high-performance liquid chromatography/electrospray mass spectrometry and exoglycosidase digestions. Biochemistry 38, 4885–4895 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stahl N. et al. Structural studies of the scrapie prion protein using mass spectrometry and amino acid sequencing. Biochemistry 32, 1991–2002 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudd P. M. et al. Glycosylation differences between the normal and pathogenic prion protein isoforms. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96, 13044–13049 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katorcha E., Makarava N., Savtchenko R., D’Azzo A. & Baskakov I. V. Sialylation of prion protein controls the rate of prion amplification, the cross-species barrier, the ratio of PrPSc glycoform and prion infectivity. PLOS Pathog. 10, e1004366, 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004366 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baskakov I. V. & Katorcha E. Multifaceted role of sialylation in prion diseases. Front. Neurosci. 10, 358, 10.3389 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lampron A., Elali A. & Rivest S. Innate Immunity in the CNS: Redefining the Relatiionship between the CNS and Its Environment. Neuron 78, 214–232 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abt M. C. & Pamer E. G. Commensal bacteria mediated defences against pathogens. Current Opinion in Immunology 29, 16–22 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abt M. C. et al. Commensal Bacteria Calibrate the Activation Threshold of Innate Antiviral Imuunity. Immunity 37, 158–170 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makarava N. et al. Recombinant prion protein induces a new transmissible prion disease in wild type animals. Acta Neuropathol. 119, 177–187 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makarava N. et al. Stabilization of a prion strain of synthetic origin requires multiple serial passages. J Biol Chem 287, 30205–30214 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeffrey M. et al. Pathology of SSLOW, a transmissible and fatal synthetic prion protein disorder, and comparison with naturally occurring classical transmissible spongoform encephalopathies. Neuropath.Appl.Neurobiol. 40, 296–310 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Montalban N. et al. Highly Efficient Protein Misfolding Cyclic Amplification. PLoS Pathogen 7, e1001277 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Montalban N., Makarava N., Savtchenko R. & Baskakov I. V. Relationship between Conformational Stability and Amplification Efficiency of Prions. Biochemistry 50, 7933–7940 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katorcha E., Makarava N., Savtchenko R. & Baskakov I. V. Sialylation of the prion protein glycans controls prion replication rate and glycoform ratio. Sci Rep 5, 16912, 10.1038/srep16912 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava S. et al. Post-conversion sialylation of prions in lymphoid tissues. Proc Acad Natl Sci USA 112, E6654–6662, 10.1073/pnas.1517993112 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saa P., Castilla J. & Soto C. Ultra-efficient Replication of Infectious Prions by Automated Protein Misfolding Cyclic Amplification. J.Biol.Chem. 281, 35245–35252 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pritzkow S. et al. Quantitative detection and biological propagation of scrapie seeding activity in vitro facilitate use of prions as model pathogens for disinfection. Plos ONE 6, e20384 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daus M. L. et al. Infrared Microspectroscopy Detects Protein Misfolding Cyclic Amplification (PMCA)-Induced Conformational Alterations in Hamster Scrapie Progeny Seeds. J Biol Chem 288, 35068–35080 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smirnovas V. et al. Structural organization of brain-derived mammalian prions examined by hydrogen-deuterium exchange. Nat Struct Mol Biol 18, 504–506 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spassov S., Beekes M. & Naumann D. Structural differences between TSEs strains investigated by FT-IR spectroscopy. Biochim Biophys Acta 1760, 1138–1149 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang F., Wang X., Yuan C. G. & Ma J. Generating a Prion Bacterially Expressed Recombinant Prion Protein. Science 327, 1132–1135 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deleault N. R. et al. Isolation of phosphatidylethanolamine as a solitary cofactor for prion formation in the absence of nucleic acids. Proc Acad Natl Sci USA 109, 8546–8551 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deleault N. R. et al. Cofactor molecules maintain infectious conformation and restrict strain properties in purified prions. Proc.Acad.Natl.Sci.USA 109, E1938–E1946 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klingeborn M., Race B., Meade-White K. D. & Chesebro B. Lower specific infectivity of protease-resistant prion protein generated in cell-free reactions. Proc Acad Natl Sci USA 108, E1244–1253 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimberlin R. H. & Walker C. A. Pathogenesis of scrapie (strain 263K) in hamsters infected intracerebrally, intraperitoneally or intraocularly. J.Gen.Virol. 67, 255–263 (1986). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyagi T. & Yamaguchi K. Mammalian sialidases: physiological and pathological roles in cellular functions. Glycobiology 22, 880–896 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Audry M. et al. Current trend in the structure-activity relationships of sialylatransferases. Glycobiology 21, 716–726 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katorcha E. et al. Knocking out of cellular neuraminidases Neu1, Neu3 or Neu4 does not affect sialylation status of the prion protein. PLoS One 10, e0143218, 10.1371/journal.pone.0143218 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makarava N., Savtchenko R. & I.V. B. Two alternative pathways for generating transmissible prion disease de novo. Acta Neuropathologica Communications 3, 69, 10.1186/s40478-015-0248-5 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins B. E. et al. Masking of CD22 by cis ligands does not prevent redistribution of CD22 to sites of cell contact. Proc Acad Natl Sci USA 101, 6104–6109 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown G. C. & Neher J. J. Microglial phagocytosis of live neurons. Nat Rev Neuroscience 15, 209–216 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savill J., Dransfield I., Gregory C. & Haslett C. A blast from the past: clearance of apoptotic cells regulates immune responses. Nat Rev Immunology 2, 965–975 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aminoff D., Bruegge W. F., Bell W. C., Sarpolis K. & Williams R. Role of sialic acid in survival of erythrocytes in the circulation: interaction of neuraminidase-treated and untreated erythrocytes with spleen and liver at the cellular level. Proc Acad Natl Sci USA 74, 1521–1524 (1977). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansen A. J. G. et al. Desialylation accelerates platelet clearance after refrigeration and initiates GPIba metalloproteinase-mediated cleavage in mice. Blood 119, 1263–1273 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samlowski W. W., Spangrude G. J. & Daynes R. A. Studies on the liver sequestration of lymphocytes bearing membrane-associated galactose-terminal glycoconjugates: reversal with agents that effectively compete for the asialoglycoprotein receptor. Cell.Immunol. 88, 309–322 (1984). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasta G. R. Roles of galectins in infection. Nat Rev Microbiol 7, 424–438 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pangburn M. K., Pangburn K. L., Koistinen V., Meri S. & Sharma A. K. Molecular mechanisms of target recognition in an innate immune system: interactions among factor H, C3b, and target in the alternative pathway of human complement. J.Immunol. 164, 4742–4751 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lv Y. et al. Remarkable Activation of the Complement System and Aberrant Neuronal Localization of the Membrane Attack Complex in the Brain Tissues of Scrapie-Infected Rodents. Mol Neurobiol 52, 1165–1179 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens B. et al. The classical complement cascade mediates CNS synapse elimination. Cell 131, 1164–1178 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein M. A. et al. Complement facilitates early prion pathogenesis. Nat.Med. 7, 488–492 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michel B. et al. Complement protein C3 exacerbates prion disease in a mouse model of chronic wasting disease. Int Immunol 25, 697–702 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zabel M. D. et al. Stromal complement receptor CD21/35 facilitates lymphoid prion colonization and pathogenesis. J Immunol 179, 6144–6152 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mabbott N. A., Bruce M. E., Botto M., Walport M. J. & Pepys M. B. Temporary depletion of complement component C3 or genetic deficiency of C1q significantly delays onset of scrapie. Nat.Med. 7, 485–487 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kajander T. et al. Dual interaction of factor H with C3d and glycosaminoglycans in host-nonhost discrimination by complement. Proc Acad Natl Sci USA 108, 2897–2902 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makarava N. et al. Genesis of mammalian prions: from non-infectious amyloid fibrils to a transmissible prion disease. PLoS Pathogen 7, e1002419 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savitzky A. & Golay M. J. E. Smoothing and Differentiation of Data by Simplified Least Squares Procedures. Analytical chemistry 36, 1627–1639 (1964). [Google Scholar]

- Lasch P. & Naumann D. Infrared Spectroscopy in Microbiology. Encyclopedia of Analytical Chemistry, 10.1002/9780470027318.a0117.pub2 (2015). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ward J. H. Hierarchical Grouping to optimize an objective function. Journal of American Statistical Association 58, 236–244 (1963). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.