Abstract

The objective of this study was to investigate how the relationships between bacterial communities and organic C (SOC) in topsoil (0–5 cm) are affected by tillage practices [conventional intensive tillage (CT) or no-tillage (NT)] and straw-returning methods [crop straw returning (S) or removal (NS)] under a rice-wheat rotation in central China. Soil bacterial communities were determined by high-throughput sequencing technology. After two cycles of annual rice-wheat rotation, compared with CT treatments, NT treatments generally had significantly more bacterial genera and monounsaturated fatty acids/saturated fatty acids (MUFA/STFA), but a decreased gram-positive bacteria/gram-negative bacteria ratio (G+/G−). S treatments had significantly more bacterial genera and MUFA/STFA, but had decreased G+/G− compared with NS treatments. Multivariate analysis revealed that Gemmatimonas, Rudaea, Spingomonas, Pseudomonas, Dyella, Burkholderia, Clostridium, Pseudolabrys, Arcicella and Bacillus were correlated with SOC, and cellulolytic bacteria (Burkholderia, Pseudomonas, Clostridium, Rudaea and Bacillus) and Gemmationas explained 55.3% and 12.4% of the variance in SOC, respectively. Structural equation modeling further indicated that tillage and residue managements affected SOC directly and indirectly through these cellulolytic bacteria and Gemmationas. Our results suggest that Burkholderia, Pseudomonas, Clostridium, Rudaea, Bacillus and Gemmationas help to regulate SOC sequestration in topsoil under tillage and residue systems.

Soil organic C (SOC) is the main source of energy for soil microorganisms1,2 and SOC content profoundly affects soil properties, including aggregate stability, soil moisture and nutrient cycling3. Thus, SOC plays an important role in maintaining long-term sustainability of agro-ecosystems and global biogeochemical cycles4. SOC is regulated by many factors, such as tillage practices1, residue management5, soil aggregate sizes6, and microbial functional diversity2. Optimizing agricultural management can reduce SOC loss, or even increase the content of SOC7. Intensive and continuous soil tilling has been practiced for thousands of years in China5. Frequent soil disturbance by intensive conventional tillage (CT) reduces soil aggregate sizes, thereby accelerating SOC oxidation8 and decreasing SOC content. Moreover, crop residue burning or removing, a common farming practice, reduces the amount of organic substances retained in the soil and the water storage capacity of the entire soil9, and decreases soil microbial biomass and functional diversity2. In contrast, no-tillage (NT) and straw returning (S) may enhance SOC content in agricultural ecosystems and facilitate sustainable agricultural production5,7.

The abundance, diversity and composition of soil microbial communities and their interactions with environment factors have great impacts on SOC dynamics6,10,11,12. In agricultural ecosystems, bacteria and fungi are the main drivers of soil processes including nutrient cycling and the decomposition of soil organic matter, such as crop residues13,14,15. Tillage practices and straw-returning methods affect the activity and community structure of soil microorganisms by changing the habitat characteristics for soil microorganisms such as soil porosity, soil moisture and the substrates for soil microorganisms16, thus affecting SOC dynamics in soil ecosystem. Although many studies have shown that soil fungi are a major factor influencing soil carbon content, these studies were focused on upland ecosystems, such as forest ecosystems17,18. In rice-wheat system, the field is long-term flooded and is mostly under anaerobic conditions during rice growing period19, which thus inhibits the growth of fungi and reduces the contributions of fungi to SOC. Some studies reported that bacteria are dominant in rice-wheat system7, which may be due to their ability to break down labile carbon sources more efficiently than other microorganisms, such as fungi20, thus contributing to the increase of SOC concentration through the binding of fresh and labile pools of organic matter with microaggregates to form macroaggregates21. Therefore, bacteria may have greater contributions to SOC concentration than fungi in the rice-wheat system.

Most of previous studies focused on the effects of tillage practices and straw-returning methods on soil bacterial abundance, and consistently showed that both NT and S practices can increase soil bacterial abundance7,22. For example, Guo et al.7 reported higher soil bacterial abundance under NT and S treatments than under CT and NS treatments, respectively, possibly because both NT and S practices provide more favorable environmental conditions for soil microorganisms23. Zhang et al.22 also reported that NT significantly increased bacterial biomass compared with CT. However, these studies ignored the relationships between soil bacterial communities and SOC. Zhang et al.6 investigated the contribution of soil biota (including bacteria) to C sequestration under different tillage practices, and showed that microbial communities controlled C storage both directly and indirectly through MBC and soil bacteria contributed to C sequestration both in <1 mm and >1 mm soil aggregates. Guo et al.1 reported the relationships between microbial metabolic characteristics and SOC within aggregates under different tillage practices and straw-returning methods, and indicated that the increased SOC in aggregates in the topsoil under NT and S practices was possibly due to the improvement of microbial metabolic activities. Nevertheless, the mechanism by which different functional genera of soil bacteria are linked to SOC sequestration under different tillage practices and their relative contributions remain unknown. Therefore, further investigation is needed to understand the relative contributions of soil bacterial communities to SOC and how these relationships may vary under different tillage practices.

Rice-wheat cropping system, which occupies a total area of 4.5 million ha in China, possesses important functions in food security in the world24. However, the sustainability of rice-wheat cropping system is negatively affected by issues such as soil degradation, air pollution25 and the long-term use of conventional management practices, such as crop residue removing or burning, or intensive soil tilling7. Rice-wheat cropping system is the most important cropping system in central China26, occupying about 20% of the total sown area in central China and accounting for about 22% of the national grain yield for these two crops in 201127. The effects of tillage practices and straw-returning methods on soil physical-chemical properties, soil nutrient and crop yield under rice-wheat cropping system in this region have been well elucidated23,26. However, little attention has been paid to the relationships between bacterial communities and SOC under different tillage practices and straw-returning methods in this region. The objective of this study was to assess the effects of tillage practices (i.e. NT and CT) and straw returning methods (i.e. crop residue removal (S) and returning (NS)) on topsoil bacterial communities and their relationships with SOC under rice-wheat cropping system in central China. We hypothesized that (1) NT and S practices can improve soil bacterial abundance mainly due to the improvement of soil nutrition condition in the topsoil layer, and (2) the bacterial communities can have positive effects on SOC under NT and S practices. Structural equation modeling (SEM) was used to detect the potential associations among tillage systems/straw systems, bacterial communities and SOC.

Results

Phospholipid fatty acid (PLFA) analysis

After a 2-year cropping cycle, NT and S practices significantly affected the composition of soil microbial communities in the 0–5 cm soil layer. Compared with CT and NS treatments, NT and S treatments had significantly higher total PLFAs, bacterial PLFA, gram-positive bacterial PLFA, gram-negative bacterial PLFA and MUFA/STFA, and significantly lower G+/G− (Table 1 and Supplementary information).

Table 1. Characteristics of soil microbial communities under different treatments.

| Microbial community | CTNS | CTS | NTNS | NTS | T | S | T × S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total PLFAs (nmol g−1) | 10.93 ± 0.05 d | 24.74 ± 0.05 b | 15.89 ± 0.06 c | 36.14 ± 0.07 a | ** | ** | ** |

| Bacterial PLFA (nmol g−1) | 2.79 ± 0.05 d | 8.40 ± 0.09 b | 5.12 ± 0.05 c | 14.40 ± 0.07 a | ** | ** | ** |

| Gram-positive bacterial PLFA (nmol g−1) | 2.00 ± 0.04 d | 5.14 ± 0.09 b | 3.37 ± 0.04 c | 8.06 ± 0.03 a | ** | ** | ** |

| Gram-negative bacterial PLFA (nmol g−1) | 0.78 ± 0.02 d | 3.26 ± 0.00 b | 1.75 ± 0.01 c | 6.33 ± 0.05 a | ** | ** | ** |

| G+/G− | 2.56 ± 0.04 d | 1.58 ± 0.03 b | 1.92 ± 0.01 c | 1.27 ± 0.01 a | ** | ** | ** |

| MUFA/STFA | 0.04 ± 0.00 d | 0.07 ± 0.00 b | 0.05 ± 0.00 c | 0.09 ± 0.00 a | * | ** | * |

Different letters denote significant differences among treatments. **P < 0.01; *P < 0.05; ns, not significant. CTNS, conventional intensive tillage with straw removal; CTS, conventional intensive tillage with straw returning; NTNS, no-tillage with straw removal; NTS, no-tillage with straw returning. T, tillage; S, straw; G+/G−, gram-positive bacteria/gram negative bacteria; MUFA/STFA, monounsaturated fatty acids/saturated fatty acids. Values are mean ± standard errors.

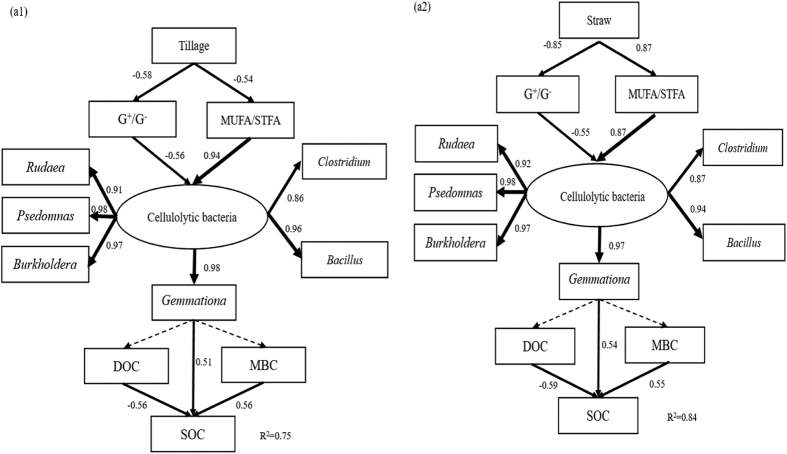

Relationships between PLFA and SOC fractions

Redundancy analysis showed that the coordinates from the first two ordination axes explained 89.4% (the first axis 89.3% and the second 0.1%) of the variances (Fig. 1). A Monte Carlo permutation test showed that SOC fractions (including SOC) were significantly correlated with the differences in the composition of the soil microbial community (P < 0.05). Moreover, SOC was the most closely related to G+/G− and MUFA/STFA. Overall, a clear separation was found between treatments (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Redundancy analysis of soil microbial communities and SOC fractions under different treatments.

SOC, soil organic C; MBC, microbial biomass C; DOC, dissolved organic C; MUFA/STFA, monounsaturated fatty acids/saturated fatty acids; CTNS (▵), conventional intensive tillage with straw removal, CTS (▴), conventional intensive tillage with straw returning; NTNS (□), no-tillage with straw removal; NTS (■), no-tillage with straw returning.

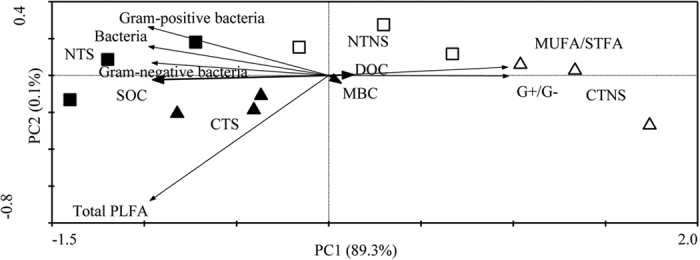

Soil bacterial community structure

In general, NT treatments had significantly greater bacterial abundance compared with CT treatments, and S treatments had significantly higher bacterial abundance of 11 main soil genera compared with NS treatments (Fig. 2, Table 2 and Supplementary information). Compared with CT treatments, NT treatments had significantly greater abundance of Gemmatimonas, Rudaea, Sphingomonas, Caulobacter, Dokdonella, Telmatospirillum, Pseudomonas, Burkholderia, Pseudolabrys, Blastochloris, and Bacillus. Compared with NS treatments, S treatments had significantly higher abundance of Gemmatimonas, Rudaea, Sphingomonas, Dokdonella, Rhodanobacter, Mycobacterium, Nitrospira, Gemmata, Schlesneria, Pseudomonas, Pirellula, Burkholderia, Clostridium, Pseudolabrys, Blastochloris, Arcicella and Bacillus.

Figure 2. Relative abundance (n = 3) of top 23 OTUs of bacteria genera under different treatments revealed by pyrosequencing.

CTNS, conventional intensive tillage with straw removal; CTS, conventional intensive tillage with straw returning; NTNS, no-tillage with straw removal; tillage; NTS, no-tillage with straw returning.

Table 2. Taxonomy of soil bacterial communities determined in the present study.

| Phylum | Class | Order | Family | Genus | T | S | T*S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Actinobacteria | Actinobacteria | Actinomycetales | Mycobacteriaceae | Mycobacterium | ns | ** | ns |

| Bacteroidetes | Sphingobacteria | Sphingobacteriales | Cytophagaceae | Arcicella | ns | ** | ns |

| Firmicutes | Bacilli | Bacillales | Bacillaceae | Bacillus | ** | ** | ns |

| Clostridia | Clostridiales | Clostridiaceae | Clostridium | ns | * | ns | |

| Gemmatimonadetes | Gemmatimonadetes | Gemmatimonadales | Gemmatimonadaceae | Gemmatimonas | ** | ** | ** |

| Nitrospira | Nitrospira | Nitrospirales | Nitrospiraceae | Nitrospira | ns | ** | ns |

| Planctomycetes | Planctomycetacia | Planctomycetales | Planctomycetaceae | Gemmata | ns | ** | ** |

| Planctomycetales | Planctomycetaceae | Pirellula | ns | ** | ** | ||

| Planctomycetales | Planctomycetaceae | Schlesneria | ns | * | * | ||

| Planctomycetales | Planctomycetaceae | Zavarzinella | ns | ns | ns | ||

| Proteobacteria | Alphaproteobacteria | Caulobacterales | Caulobacteraceae | Caulobacter | * | ns | * |

| Caulobacterales | Caulobacteraceae | Phenylobacterium | ns | ns | ns | ||

| Rhizobiales | Hyphomicrobiaceae | Blastochloris | * | ** | * | ||

| Rhizobiales | Xanthobacteraceae | Pseudolabrys | * | ** | * | ||

| Rhodospirillales | Rhodospirillaceae | Telmatospirillum | * | ns | ns | ||

| Sphingomonadales | Sphingomonadaceae | Sphingomonas | * | * | ns | ||

| Betaproteobacteria | Burkholderiales | Burkholderiaceae | Burkholderia | ** | ** | ** | |

| Gammaproteobacteria | Methylococcales | Methylococcaceae | Methylococcus | ns | ns | ns | |

| Pseudomonadales | Pseudomonadaceae | Pseudomonas | ** | ** | ** | ||

| Xanthomonadales | Xanthomonadaceae | Dokdonella | ** | ** | ** | ||

| Xanthomonadales | Xanthomonadaceae | Dyella | ns | ns | ns | ||

| Xanthomonadales | Xanthomonadaceae | Rhodanobacter | ns | ** | ns | ||

| Xanthomonadales | Xanthomonadaceae | Rudaea | * | ** | * |

Different letters denote significant differences among treatments. **P < 0.01; *P < 0.05; ns, not significant. T, tillage; S, straw; Values are mean ± standard errors.

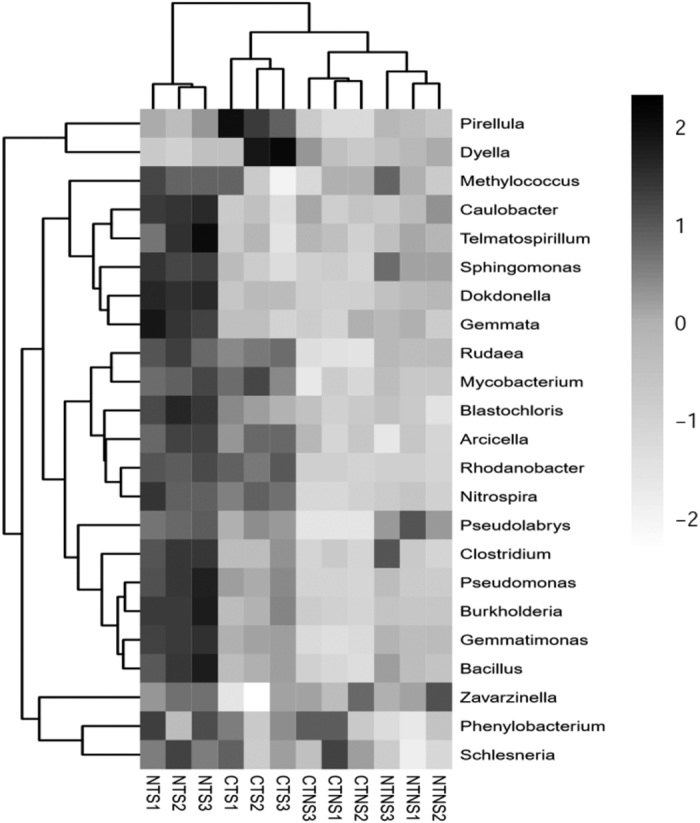

Relationship between soil bacterial communities and SOC fractions

Redundancy analysis showed that the coordinates from the first two ordination axes explained 82.9% (the first axis 69.6% and the second 13.3%) of the variances (Fig. 3). A Monte Carlo permutation test showed that all SOC fractions (including SOC) were significantly correlated with the differences in the abundance of bacterial communities (P < 0.05). Moreover, SOC was positively correlated with the abundance of Burkholderia, Pseudomonas, Clostridium, Rudaea, Gemmatimonas and Bacillus. Clear separations could be seen between treatments in the redundancy analysis (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. Redundancy analysis of soil bacterial communities and SOC fractions under different treatments.

CTNS (▵), conventional intensive tillage with straw removal; CTS (▴), conventional intensive tillage with straw return; NTNS (◽), no-tillage with straw removal; NTS (◾), no-tillage with straw returning; SOC, soil organic C; MBC, microbial biomass C; DOC, dissolved organic C.

Stepwise regression analysis

Gemmatimonas, Rudaea, Spingomonas, Pseudomonas, Dyella, Burkholderia, Clostridium, Pseudolabrys, Arcicella and Bacillus were significantly related to SOC (Table 3).

Table 3. Relationships between SOC and bacterial genera based on stepwise regression analysis.

| Constant and dependent variables | Coefficient of regression estimate | P value | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 15.284 | ** | R2 = 0.99 |

| Gemmatimonas | 0.001 | * | |

| Rudaea | 0.004 | ** | |

| Sphingomonas | 0.009 | * | |

| Pseudomonas | 0.089 | ** | |

| Dyella | 0.069 | ** | |

| Burkholderia | −0.093 | ** | |

| Clostridium | 0.009 | * | |

| Pseudolabrys | −0.018 | ** | |

| Arcicella | −0.015 | * | |

| Bacillus | 0.111 | ** |

*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

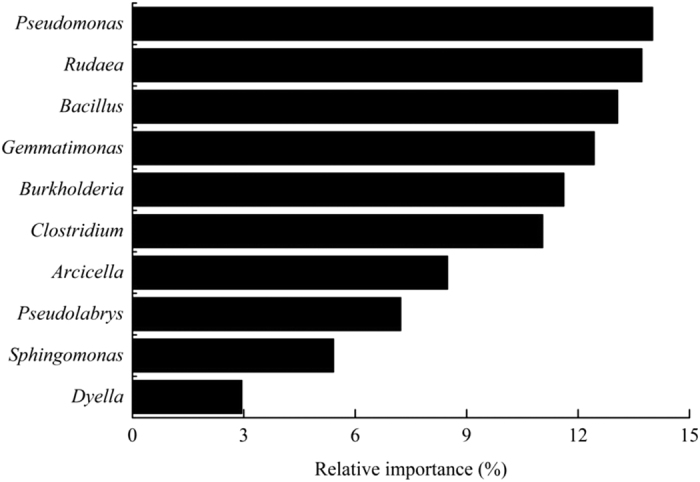

Relative importance analysis

All bacterial genera could explain 86.6% of the variances in SOC (Fig. 4). Pseudomonas, Rudaea, Bacillus, Gemmatimonas, Burkholderia and Clostridium were the main influencing factors to SOC, which together explained 75.6% of the variances.

Figure 4. Relative importance analysis of the soil bacterial genera to SOC by R (relative importance package) based on the results of stepwise regression analysis.

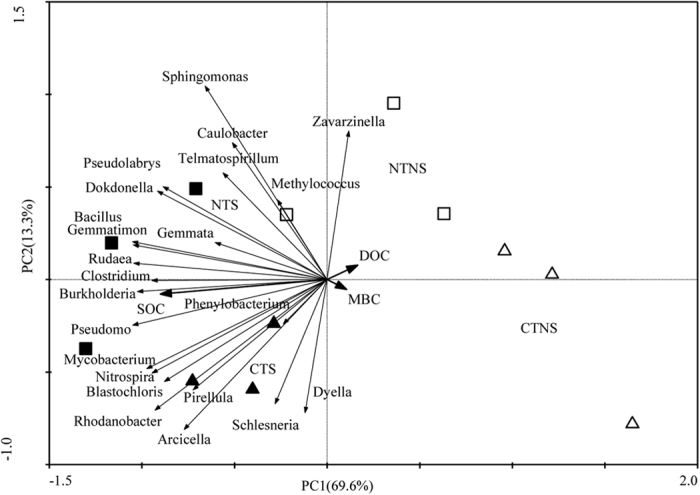

Links between soil bacterial communities and SOC

SEM revealed that the predictors explained 75.0–84.0% of the variances in SOC (Fig. 5). In Fig. 5a1,a2, tillage and straw systems had different levels of MUFA/STFA and G+/G−, and thus likely affected SOC directly and indirectly through the presence of 5 kinds of cellulolytic bacteria (Pseudomonas, Rudaea, Bacillus, Burkholderia and Clostridium) and Gemmatimonas.

Figure 5. Structural equation model relating tillage systems, straw systems and bacteria communities to SOC (a1, χ2 = 124.867, df = 51, p = 0.525, CFI = 0.952, GFI = 0.923, RMSEA = 0.010; a2, χ2 = 114.847, df = 51, p = 0.565, CFI = 0.962, GFI = 0.915, RMSEA = 0.001).

Rectangles represent observed variables. Arrow thickness represents the magnitude of the path coefficient. Values associated with solid arrows represent the path coefficients. Solid and dashed arrows indicate significance (P < 0.05) and non-significance (P > 0.05), respectively. Straw, straw systems; DOC, dissolved organic C; MBC, microbial biomass C; SOC, soil organic C.

Discussion

This study investigated the effects of tillage practices and straw-returning methods on soil bacterial communities and their relation to SOC after a 2-year rice-wheat cropping cycle in central China. The results supported our hypotheses that NT and S practices increase the abundance of bacterial genera in the topsoil bacterial communities, and that the composition of the bacterial community is correlated with SOC.

Effects of tillage practices and straw returning methods on soil bacterial community

NT and S practices generally increased the abundance, activity and diversity of soil microbial communities in the topsoil layer2,28,29, probably because NT minimizes soil disturbance and S contributes to greater accumulation of crop residues on the soil surface8, thus improving soil nutrition condition for soil microbial communities7. Soil nutrition condition can be indicated by G+/G− ratio30. Lower G+/G− ratio under NT treatments compared with under CT treatments (Table 1) suggests that nutrients are rich in the topsoil layer under NT treatments, which demonstrates the improvement of soil environment for microorganisms under NT7. Guo et al.7 and Wang et al.31 also reported that NT could significantly increase soil N, organic C and SOC fractions compared with CT, whereas CT could negatively affect soil microbial biomass and SOC. Moreover, a greater MUFA/STFA ratio in NT treatments compared with in CT treatments (Table 1) suggests that NT treatments may improve soil gas permeability as suggested by Bossio et al.32, because of the accumulation of crop residues on the soil surface under NT8.

Straw returning, as an input of organic residues to improve soil nutrition condition, can increase soil surface residue C and SOC7 and provide energy sources for soil microbes, thus enhancing soil microbial biomass2,7. Residue amendment improves soil moisture and temperature and promotes soil aggregation, thus boosting microbial growth20, which is supported by the result of lower G+/G− under S treatments than under NS treatments (Table 1). However, in the study of the impacts of residue management on soil properties and soil microbial community structure, Wang et al.33 did not find significant differences in bacterial abundance between S and NS treatments. In addition, S treatments had a higher MUFA/STFA ratio compared with NS treatments (Table 1). This result indicates that soils under S treatments may have greater gas permeability32, possibly because straw returning decreases the sensitivity to surface sealing34 and increases the porosity of the top soil layer35. Good soil gas permeability and enrichment of organic matter in soil surface under NT and S practices7,8 also promote the decomposition of exogenous crop straw, thus improving soil nutrition condition. Therefore, NT and S practices improve soil nutrition, leading to the increase of soil bacterial abundance in the topsoil layer.

Relationships between soil bacterial communities and SOC

Our results showed that there were seven predominant bacterial genera (Gemmatimonas, Rudaea, Caulobacter, Sphingomonas, Dokdonella, Rhodanobacter and Mycobacterium) in the 0–5 cm soil layer, which accounted for 67.7% of total bacterial abundance (Fig. 2). Multiple analysis results showed that soil bacterial communities were closely related to SOC, and Pseudomonas, Rudaea, Bacillus, Gemmatimonas, Burkholderia and Clostridium greatly contributed to SOC, together explaining 75.6% of the variances in SOC. Pseudomonas, Rudaea, Bacillus, Clostridium, Burkholderia and Dyella belong to cellulolytic bacteria32, and together explained 66.3% of the variances in SOC, suggesting that SOC is mainly regulated by these six cellulolytic bacteria. Cellulose is unavailable to most soil microorganisms because the crystallinity of cellulose is extremely recalcitrant for enzymatic degradation36. Some studies have suggested that cellulolytic bacteria help to regulate the C cycle37 because they play an important role in the decomposition of plant residues in the soil ecosystem36.

In this study, most of the cellulolytic bacteria screened by stepwise regression analysis are aerobic microorganisms (Table 3), which can be attributed to the high permeability in the 0–5 cm soil layer35. Generally, cellulose is mainly degraded in aerobic environments, while up to 5–10% of cellulose is degraded by physiologically diverse bacteria under anaerobic conditions37. Many studies have indicated that Clostridium, one of important cellulolytic anaerobic bacterial genera38, is highly efficient in degrading cellulose36,39 because it excretes several kinds of enzymes including cellulase and hemicellulase40. In the present study, NT and S treatments had significantly greater Clostridium abundance (Fig. 2). Multiple analyses suggested that Clostridium may play important roles in SOC (Figs 1, 2, 3 and 4). Clostridium is negatively affected by greater oxygen availability in the soil and soil disturbance8. Hence, its high abundance under NT and S treatments was not unexpected as it is likely that the higher residue mulching under S practice and/or less soil disturbance under NT1,7 create anaerobic zones in the surface soil.

Gemmatimonas (22.6%, 245 OTUs) is the most abundant bacterial genera in this study (Fig. 2), and explained 12.4% of the variances in SOC (Fig. 4). The SEM also showed the key function of Gemmatimonas to SOC sequestration under NT and S practices in this study (Fig. 5). The reason may be that Gemmatimonas can use the metabolic products as sole C sources41, such as acetate and propionate42,43,44, but most of other bacterial genera, such as Bellilinea45 and Sphingomonas46 (Fig. 2), cannot or can only weakly use the metabolic products of cellulose. Thus, it is likely that Gemmatimonas has greater ability to use available C sources compared with other soil microorganisms. The SEM further showed that Gemmatimonas plays an important role in SOC dynamics (Fig. 5), which can be attributed to the fact that Gemmatimonas can reduce the metabolic products of cellulose41 and thus indirectly promotes the degrading process of cellulose.

Tillage practices and straw returning methods affect the activity and structure of soil microorganisms by changing the habitat characteristics for soil microorganisms such as soil gas permeability and the substrates for soil microorganisms16,33, thus affecting SOC. Both NT and S practices promote the accumulation of straw on the soil surface, in which the major component is cellulose47, thus improving soil physical conditions21 and also providing C sources (specifically cellulose) for cellulolytic bacteria36. Therefore, NT and S practices promoted the growth of cellulolytic bacteria (Fig. 2), thus increasing the decomposition of cellulose and subsequently the SOC (Figs 2, 3, 4 and 5 and Table 3). Decomposition of exogenous crop straw provides C sources for other soil microorganisms, and therefore increases soil microbial biomass48, which contributes to the developing and increasing of soil organic matter2,6. However, exogenous organic matter from broken down cellulose promotes C sequestration in soil aggregates, especially in >250 μm aggregates because the broken down exogenous organic matter could be bound to the walls of the mineral particles that surround them2,21. Yin et al.49 also reported that bacteria play critical roles in the production of soil aggregates and the conversion of plant residue to soil organic matter. The results of this study suggest that tillage changes the habitats for Pseudomonas, Rudaea, Bacillus, Burkholderia, Della and Clostridium, and then changes the decomposition process of residue, thus affecting SOC in the 0–5 cm soil layer.

This study indicates that after two cycles of rice-wheat rotation, NT and S practices promote SOC in the 0–5 cm soil layer presumably by increasing the abundance of bacterial genera. Redundancy analysis showed a close relationship between SOC levels and the abundance of specific bacterial genera in the soil community. Stepwise regression analysis and relative influence analysis indicated that Gemmatimonas, Rudaea, Spingomonas, Pseudomonas, Dyella, Burkholderia, Clostridium, Pseudolabrys, Arcicella and Bacillus are positively correlated with SOC. SEM results further suggested that NT and S practices specifically increase the abundance of 5 kinds of cellulolytic bacteria (Burkholderia, Pseudomonas, Clostridium, Rudaea, and Bacillus) and Gemmatimonas in the upper soil layer, likely promoting SOC levels. However, the mediation of bacterial communities on SOC under long-term NT and S practices in the rice-wheat cropping system should be further discussed. Long-term (5+ years) NT and S practices may change SOC in the whole plough layer (0–20 cm); however, the ability of bacterial communities to regulate these effects remains unclear. Therefore, further studies should be conducted to reveal the mechanism of the effects of long-term NT and S practices on soil bacterial communities and their contributions to SOC in the whole plow layer.

Methods

Experimental site

The study site was located at an experimental farm of Huazhong Agricultural University Research (29°51′N, 115°33′E) in the town of Huaqiao Town, Wuxue City, Hubei Province, China, which has been described by Guo et al.2. The soil is a silty clay loam classified by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) as a Gleysol2. The experimental soil (0–20 cm depth) has a pH of 4.79, an organic C content of 16.89 g kg−1, a total nitrogen (N) content of 2.20 g kg−1, a total phosphorus (P) content of 0.45 g kg−1, and a bulk density of 1.21 g cm−3. The cropping regime was dominated by two crops: summer rice (HHZ, Oryza sativa L.) and winter wheat (ZM9023, Triticum aestivum L.).

Experimental design

The detailed experimental design was described by Guo et al.2. In brief, field treatments followed a split-plot design of a randomized complete block with tillage practices (conventional intensive tillage, CT; no tillage, NT) as the main plots and straw returning methods [crop straw removal (NS) and crop straw return (S)] as the subplots. The experiment involved four treatments: CTNS, CTS, NTNS and NTS, with each replicated for three times. For CTNS and NTNS treatments, crop residues were removed and not returned to the field. For CTS and NTS treatments, residues were chopped into pieces 5–7 cm in length and returned to the field. The chopped straw was mulched in NT soil and tilled into CT soil. For CT treatments, the soil was moldboard ploughed twice to a 20 cm depth before throwing of rice seedlings and once before sowing of wheat. The soil was not disturbed for NT treatments. Commercial compound fertilizer (15% N, 15% P2O5, and 15% K2O), urea (46% N), single superphosphate (12% P2O5), and potassium chloride (60% K2O) were used to provide 180 kg N ha−1, 90 kg P2O5 ha−1, and 180 kg K2O ha−1 during the rice-growing seasons, and 144 kg N ha−1, 72 kg P2O5 ha−1, and 144 kg K2O ha−1 during the wheat-growing season. P and K fertilizers were only applied as basal fertilizers, and N fertilizers were used with 50%, 20%, 12%, and 18% at the seedling, tillering, jointing, and earring stages of rice-growing seasons, and with 50%, 30%, and 20% at the seedling, tillering, and boosting stages of wheat-growing seasons, respectively. The plots were irrigated to a depth of 8 cm whenever the water depth above soil surface decreased for 1–2 cm during the rice growing season, and were drained in the tillering and maturing stages. We did not irrigate during the wheat-growing season.

Soil sampling

Soil samples were collected from the topsoil (0–5 cm depth) using a soil sampler (7 cm diameter) immediately after wheat harvest in June 2013 at eight random points in each plot. After sampling, visible plant residues and stones were removed, and large soil clods were gently broken by hand. Soils were sieved through a 5 mm screen for uniformity, and stored at −20 °C, and all determinations were finished within two weeks.

The SOC and its fractions (microbial biomass C (MBC) and dissolved organic C (DOC)) in the 0–5 cm soil layer were reported previously by Guo et al.2.

Phospholipid fatty acid (PLFA) analysis

PLFA analysis was conducted to measure the composition of soil microbial communities according to the methods of Blair et al.50 and Bossio et al.32 and detailed measurements were performed as described by Guo et al.7. Briefly, lipids were extracted in a single-phase chloroform-methanol-citrate (1:2:0.8) buffer system. Polar lipids were separated from neutral lipids and glycolipids on solid phase extraction columns (Supelco Inc, Bellefonte, PA, USA) by eluting with CHCl3, acetone, and methanol. The phosholipid fractions were saponified and methylated to fatty acid methyl esters (FAME). Nonadecanoic acid methyl ester was used as internal standard and was added to calculate the absolute amounts of FAMEs before measurements. PLFAs were analyzed as FAMEs on a gas chromatograph/mass spectrometry system (6890–5973N series GC/MS Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA, USA).

DNA extraction, PCR amplification, 16S rDNA gene amplification and 454 pyrosequencing

High-throughput sequencing technology, a common method for identifying bacterial communities in various habitats and environmental samples, was used to identify bacteria in the soil samples51. Total soil DNA was extracted using a FastDNA® Kit for soil (MP Biomedicals, Santa Ana, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The concentration and quality (A260/A280) of the soil DNA were measured by a NanoDrop ND-2000 spectrophotometer (NanoDrop, Wilmington, DE, USA). The DNA of each sample was diluted 50-fold and stored at −20 °C, and all determinations were completed within two weeks.

An aliquot (10 ng) of purified DNA from each sample (one biological replicate) was used as template for amplification. The primer 357F (5′-CCTACGGGAGGCAGCAG-3′), which was modified with the addition of the 454 FLX-titanium adaptor “B” sequence (5′-CCTATCCCCTGTGTGCCTTGGCAGTCTCAG-3′), was used to amplify the V3, V4 and V5 hypervariable regions of the bacterial 16S rDNA52, and 926R: 5′-CCGTCAATTCMTTTRAGT-3′ was modified with the addition of unique 6–8 nucleotide barcode sequences and the 454 FLX-titanium adaptor “A” sequence (5′-CCATCTCATCCCTGCGTGTCTCCGACTCAG-3′)52. Each sample was amplified in triplicate in a 25 μl reaction and the program was as follows: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 4 min, followed by 25 cycles of denaturation (94 °C for 30 s), annealing (55 °C for 45 s), extension (72 °C for 1 min), and a final elongation step for 8 min at 72 °C. PCR Purification Kit (Axygen, Union City, CA, USA) was used to purify the PCR products. The amplicons of each sample were then pooled in equimolar concentrations into a single tube prior to 454 pyrosequencing. Pyrosequencing was performed on a 454 GS-FLX Titanium System (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) by Shanghai Personal Biotechnology Co., Ltd. Quality filtering of data was conducted following Fierer et al.53 using the Quantitative Insights into Microbial Ecology (QIIME) pipeline (http://qiime.sourceforge.net)54. In brief, sequences with an average quality score of less than 25, sequences with lengths less than 200 nt or greater than 1,000 nt, with ambiguous bases greater than 1, with homopolymer lengths greater than 6, or with maximum primer mismatches greater than 0 were removed from the dataset. And chimeric sequences were removed using the uchime algorithm in mothur (Version 1.21.2, http://www/mothur.org/)55. Sequences were clustered into operational taxonomic units (OTUs) using the QIIME implementation of cd-hit with a threshold of 97% pairwise identity. The longest sequences were extracted and taken as representatives for taxonomic identification by BLAST searches against the non-redundant GenBank sequence database. In order to study the function of soil bacterial communities in the SOC dynamics, the relative abundance of soil bacterial genera (OTUs) was used for multiple analysis in this study.

Statistical analyses

General linear model analysis of variance with SAS 9.0 designed for split plot with tillage practice and straw returning methods as fixed factors and replicates as random factors was conducted to test the main effects and interactions of tillage and straw returning. The least significant difference (LSD) test was used determine the significance of the effects of tillage, straw returning or their interactions. Only the means statistically different at P ≤ 0.05 were considered. Detrended correspondence analysis performed by CANOCO software showed that the data of characteristics of soil microbial communities and bacterial abundance were fitted with the linear model. Thus, redundancy analysis was performed using CANOCO software to explain the relationships between SOC fractions and bacterial communities. Monte Carlo permutation test performed by Cannoco 4.5 was used to assess the statistical significance of explanatory variables. Stepwise regression analysis (SAS 9.0) was performed to determine the relationships between SOC and bacterial genera. The contributions of bacterial genera to SOC were estimated by the relative importance analysis, using the “relaimpo” package in R56. Structural equation modeling (SEM), a multivariate statistical method that enables hypothesis testing of complex path-relation networks57, was used to evaluate whether bacterial communities mediate the change of SOC in response to the conversion of CT to NT, or NS to S. We constructed an a priori model according to a literature review and our knowledge of how these predicators are related. The initial model comprised eight predictors: tillage systems (Tillage), straw systems (Straw), monounsaturated fatty acids/saturated fatty acids (MUFA/STFA), gram-positive bacteria/gram-negative bacteria (G+/G−), dissolved organic carbon (DOC), microbial biomass carbon (MBC), soil organic carbon (SOC), and key genera of the soil bacterial communities (Pseudomonas, Rudaea, Bacillus, Burkholderia, Clostridium, and Gemmatimonas picked by stepwise regression analyses), which greatly contributed to the SOC. A ‘robust’ maximum likelihood estimation procedure of AMOS 7.0 software was conducted for the analysis. χ2-test, comparative fit index (CFI), goodness-of-fit (GFI) and root square mean error of approximation (RMSEA) were performed to evaluate model fit.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Guo, L. et al. Tillage practices and straw-returning methods affect topsoil bacterial community and organic C under a rice-wheat cropping system in central China. Sci. Rep. 6, 33155; doi: 10.1038/srep33155 (2016).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work is funded by the State Key Special Program of Soil Fertility Improvement and Cropping Innovation for High Yield with High Efficiency in Rice Cropping Areas (2016YFD0300907), National Natural Science Foundation of China (31471454), National Technology Project for High Food Yield of China (2011BAD16B02), and Huazhong Agricultural University Independent Scientific & Technological Innovation Foundation (2014bs02).

Footnotes

Author Contributions C.L. conceived and designed the experiments; L.J. conducted the experiments; L.G. and S.Z. did the analysis; C.L., C.C. and L.G. wrote and edited the manuscript. All authors contributed to discussion about the results and the manuscript.

References

- Mathew R. P., Feng Y., Githinji L., Ankumah R. & Balkcom K. S. Impact of No-tillage and conventional tillage on soil microbial communities. Appl. Environ Soil Sci. 10.1155/2012/548620 (2012). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guo L. J., Lin S., Liu T. Q., Cao C. G. & Li C. F. Effects of conservation tillage on topsoil microbial metabolic characteristics and organic carbon within aggregates under a rice (Oryza sativa L.) –wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) cropping system in central China. Plos One 11, e0146145 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varvel G. E. & Wilhelm W. W. Long-term soil organic carbon as affected by tillage and cropping systems. Soil. Sci. Soc. Am. J. 74, 915–921 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Larkin R. P. Soil health paradigms and implications for disease management. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 53, 199–221 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun R., Zhang X. X., Guo X., Wang D. & Chu H. Bacterial diversity in soils subjected to long-term chemical fertilization can be more stably maintained with the addition of livestock manure than wheat straw. Soil. Biol. Biochem. 88, 9–18 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S., Li Q., Lü Y., Zhang X. & Liang W. Contributions of soil biota to C sequestration varied with aggregate fractions under different tillage systems. Soil. Biol. Biochem. 62, 147–156 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Guo L. J., Zhang Z. S., Wang D. D., Li C. F. & Cao C. G. Effects of short-term conservation management practices on soil organic carbon fractions and microbial community composition under a rice-wheat rotation system. Biol. Fert. Soils 51, 65–75 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Murugan R., Koch H. J. & Joergensen R. G. Long-term influence of different tillage intensities on soil microbial biomass, residues and community structure at different depths. Biol. Fert. Soils 50, 487–498 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Wuest S. B., Caesar-TonThat T., Wright S. F. & Williams J. D. Organic matter addition, N, and residue burning effects on infiltration, biological, and physical properties of an intensively tilled silt-loam soil. Soil. Till. Res. 84, 154–167 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- Goyal S. & Sindhu S. S. Composting of rice straw using different inocula and analysis of compost quality. Microbiol. J. 1, 126–138 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Mau R. L. et al. Linking soil bacterial biodiverstity and soil carbon stability. ISME J. 9, 1477–1480 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yue H. W. et al. The microbe-mediated mechanisms affecting topsoil carbon stock in Tibetan grasslands. Int. Soc. Microb. Ecol. 9, 2012–2020 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acosta-Martínez V. et al. Microbial community composition as affected by dryland cropping systems and tillage in a Semiarid Sandy soil. Diversity 2, 910–931 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Figuerola E. L. et al. Bacterial indicator of agricultural management for soil under no-till crop production. Plos One 7, e51075 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann D., Heuer A., Hemkemeyer M., Martens R. & Tebbe C. C. Importance of soil organic matter for the diversity of microorganisms involved in the degradation of organic pollutants. ISME J. 8, 1289–1300 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J., Wang B. Z. & Jia Z. J. U. Phylogenetically distinct phylotypes modulate nitrification in a paddy soil. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 81, 3218–3227 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekblad A. et al. The production and turnover of extramatrical mycelium of ectomycorrhizal fungi in forest soils: role in carbon cycling. Plant Soil 366, 1–27 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Clemmensen K. E. et al. Roots and associated fungi drive long-term carbon sequestration in boreal forest. Science 339, 1615–8 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witt. C. et al. Crop rotation and residue management effects on carbon sequestration, nitrogen cycling and productivity of irrigated rice systems. Plant Soil. 225, 263–278 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Govaerts B. et al. Infiltration, soil moisture, root rot and nematode populations after 12 years of different tillage, residue and crop rotation managements. Soil. Till. Res. 94, 209–219 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Grosbellet C., Vidal-Beaudet L., Caubel V. & Chapentier S. Improvement of soil structure formation by degradation of coarse organic matter. Geoderma 162, 27–38 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Zhang B., Li Y., Ren T. & Tian C. J. Short-term effect of tillage and crop rotation on microbial community structure and enzyme activities of a clay loam soil. Biol. Fert. Soils 50, 1077–1085 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Zhu L., Hu N., Yang M. F., Zhan X. & Zhang Z. Effects of different tillage and straw return on soil organic carbon in a rice-wheat rotation system. Plos One 9, e88900 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumari M. et al. Soil aggregation and associated organic carbon fractions as affected by tillage in a rice-wheat rotation in North India. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 75, 560–567 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Guo J. H. et al. Significant acidification in major Chinese croplands. Science 327, 1008–1010 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding L. L., Cheng H., Liu Z. F. & Ren W. W. Experimental warming on the rice-wheat rotation agro-ecosystem. Plant. Sci. J. 31, 49–56 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Editorial Board of China Agriculture Yearbook China. Agriculture Yearbook 2009, Electronic Edition. China Agriculture Press, Beijing, China (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Wolfarth F., Schrader S., Oldenburg E. & Weinet J. Nematode-collembolan-interaction promotes the degradation of Fusarium biomass and deoxynivalenol according to soil texture. Soil. Biol. Biochem. 57, 903–910 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Swedrzyńska D., Małecka I., Blecharczyk A., Swedrzyński A. & Starzyk J. Effects of various long-term tillage systems on some chemical and biological properties of soil. Pol. J. Environ. Studies 22, 1835–1844 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y. et al. Long-term impact of farming practices on soil organic carbon and nitrogen pools and microbial biomass and activity. Soil. Till. Res. 117, 8–16 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Hammesfahr U., Heuer H., Manzke B., Smalla K. & Thiele-Bruhn S. Impact of the antibiotic sulfadiazine and pig manure on the microbial community structure in agricultural soils. Soil. Biol. Biochem. 40, 1583–1591 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Bossio D. A. & Scow K. M. Impacts of carbon and flooding on soil microbial communities: phospholipid fatty acid profiles and substrate utilization patterns. Microb. Ecol. 35, 265–278 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J. J. et al. Effects of tillage and residue management on soil microbial communities in north china. Plant. Soil. Environ. 58, 28–33 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Eynard A., Schumacher M. J., Lindstrom M. J., Malo D. D. & Kohl R. A. Effects of aggregate structure and organic C on wettability of Ustolls. Soil. Till. Res. 88, 205–216 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- Zeytin S. & Baran A. Influences of composted hazelnut husk on some physical properties of soils. Bioresource Technol. 88, 241–244 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koeck D. E., Pechtl A., Zverlov V. V. & Schwarz W. H. Genomics of cellulolytic bacteria. Curr. Opin. Biotech. 29, 171–183 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monserrate E., Leschine S. B. & Canale-Parola E. Clostridium hungatei sp. nov., a mesophilic, N2-fixing cellulolytic bacterium isolated from soil. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 51, 123–132 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suresh K., Prakash D., Rastogi N. & Jain R. K. Clostridium nitrophenolicum sp. Nov., a novel anaerobic p-nitrophenol-degrading bacterium, isolated from a subsurface soil sample. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 57, 1886–1890 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desvaux M., Guedon E. & Petitdemange H. Cellulose catabolism by Clostridium cellulolyticum growing in batch culture on defined medium. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66, 2461–2470 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koukiekolo R. et al. Degradation of corn fiber by Clostridium cellulovorans cellulases and hemicellulases and contribution of scaffolding protein CbpA. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71, 3504–3511 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takaichi S., Maoka M., Takasaki K. & Hanada S. Carotenoids of Gemmatimonas aurantiaca (Gemmatimonadetes): identification of a novel carotenoid, deoxyoscillol 2-rhamnoside, and proposed biosynthetic pathway of oscillol 2, 29-dirhamnoside. Microbiology 156, 757–763 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glissmann K. & Conrad R. Fermentation pattern of methanogenic degradation of rice straw in anoxic paddy soil. FEMS Microb. Ecol. 31, 117–126 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glissmann K. & Conrad R. Saccharolytic activity and its role as a limiting step in methane formation during the anaerobic degradation of rice straw in rice paddy soil. Biol. Fert. Soils 35, 62–67 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- Glissmann K., Weber S. & Conrad R. Localization of processes involved in methanogenic in degradation of rice straw in anoxic paddy soil. Environ. Microbiol. 3, 502–511 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada T. et al. Bellilinea caldifistulae gen. nov., sp. nov. and Longilinea arvoryzae gen. nov., sp. nov., strictly anaerobic, filamentous bacteria of the phylum Chloroflexi isolated from methanogenic propionate-degrading consortia. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 57, 2299–2306 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi M., Hamana K. & Hiraishi A. Proposal of the genus Sphingomonas sensu stricto and three new genera, Sphingobium, Novosphingobium and Sphingopyxis, on the basis of phylogenetic and chemotaxonomic analyses. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 51, 1405–1417 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng J., Lü Z., Rui J. & Lu Y. Dynamics of the methanogenic archaeal community during plant residue decomposition in an anoxic rice field soil. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74, 2894–2901 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayres E., Steltzer H., Berg S. & Wall D. H. Soil biota accelerate decomposition in high-elevation forests by specializing in the breakdown of litter produced by the plant species above them. J. Ecol. 97, 901–912 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Yin C., Jones K. L., Peterson D. E., Garrett K. A. & Hulbert S. H. Members of soil bacterial communities sensitive to tillage and crop rotation. Soil. Biol. Biochem. 42, 2111–2118 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Blair G. J., Lefory R. D. B. & Lise L. Soil carbon fractions based on their degree of oxidation and the development of a carbon management index for agricultural system. Aust. J. Agric. Res. 46, 1459–1466 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- Peiffer J. A. et al. Diversity and heritability of the maize rhizosphere microbiome under field conditions. PNAS 110, 6548–6553 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J. C. et al. Impact of enhanced staphylococcus DNA extraction on microbial community measures in cystic fibrosis sputum. Plos One 7, e33127 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fierer N., Hamady M., Lauber C. L. & Jackson R. B. The influence of sex, handedness, and washing on the diversity of hand surface bacteria. PNAS 105, 17994–17999 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caporaso J. G. et al. QIIME allows integration and analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat. Methods 7, 335–336 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar R. C., Haas B. J., Clemente J. C., Quince C. & Knight R. Uchime improves sensitivity and speed of chimera detection. Bioinformatics 27, 2194–2200 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groemping U. Relaimpo: relative importance of regressors in linear models. R package version 2.2-2 http://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/relaimpo/index.html (2013).

- Grace J. B., Anderson T. M., Smith M. D., Seabloom E. & Andelman S. J. Does species diversity limit productivity in natural grassland communities? Ecol. Letters 10, 680–689 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.