Abstract

Mycobacteriosis, a chronic bacterial infection, has been associated with severe losses in some zebrafish facilities and low-level mortalities and unknown impacts in others. The occurrence of at least six different described species (Mycobacterium abscessus, M. chelonae, M. fortuitum, M. haemophilum, M. marinum, M. peregrinum) from zebrafish complicates diagnosis and control because each species is unique. As a generalization, mycobacteria are often considered opportunists, but M. haemophilum and M. marinum appear to be more virulent. Background genetics of zebrafish and environmental conditions influence the susceptibility of fish and progression of disease, emphasizing the importance of regular monitoring and good husbandry practices. A combined approach to diagnostics is ultimately the most informative, with histology as a first-level screen, polymerase chain reaction for rapid detection and species identification, and culture for strain differentiation. Occurrence of identical strains of Mycobacterium in both fish and biofilms in zebrafish systems suggests transmission can occur when fish feed on infected tissues or tank detritus containing mycobacteria. Within a facility, good husbandry practices and sentinel programs are essential for minimizing the impacts of mycobacteria. In addition, quarantine and screening of animals coming into a facility is important for eliminating the introduction of the more severe pathogens. Elimination of mycobacteria from an aquatic system is likely not feasible because these species readily establish biofilms on surfaces even in extremely low nutrient conditions. Risks associated with each commonly encountered species need to be identified and informed management plans developed. Basic research on the growth characteristics, disinfection, and pathogenesis of zebrafish mycobacteria is critical moving forward.

Keywords: biofilms, disinfection, mycobacteriosis, Mycobacterium chelonae, Mycobacterium haemophilum, Mycobacterium marinum, surveillance, zebrafish

Introduction

The use of zebrafish (Danio rerio) as a model in biomedical research has expanded greatly in the last 15 years. Studies range from human disease research (Lieschke and Currie 2007) to infectious disease including mycobacteriosis (Lesley and Ramakrishnan 2008; van der Sar et al. 2004), cell function (Ellett and Lieschke 2010), toxicology (Stanley et al. 2009), and behavior (Norton and Bally-Cuif 2010). These are only a few examples and, as research expands, so does the need for development of a comprehensive approach to managing zebrafish health.

With a focus on infectious disease as a primary component of zebrafish health, the most commonly encountered diseases are microsporidiosis, caused by Pseudoloma neurophilia (Kent and Bishop-Stewart 2003), and mycobacteriosis, caused by several species of the genus Mycobacterium (Kent et al. 2004). Such infectious diseases have the potential to impact research and should be eliminated or at least controlled to the point where the impact is minimal (Baker 2003). Mycobacterium-related nonprotocol variation is poorly quantified in zebrafish (Kent et al. 2012, in this issue), but the common occurrence of these infections warrants investigation. Whereas control of the obligate parasite P. neurophilia appears feasible through strict biosecurity policies (Kent et al. 2011; Sanders et al. 2012, in this issue), Mycobacterium species present numerous additional challenges for control.

Mycobacteria are facultative pathogens that can survive outside the host in surface biofilms (Falkinham 2009; Falkinham et al. 2001). Thus, screening of animals and eggs alone may be ineffective for eliminating mycobacteria that may colonize a facility by water, food, or personnel (clothing, hands, equipment), and may grow and spread in the absence of a host animal. This is exemplified in the aforementioned efforts of Kent and colleagues (2011) to establish a P. neurophilia–free colony of fish; the obligate parasite was eliminated but mycobacteriosis was still reported in a small proportion of fish. There is no single etiological agent of mycobacteriosis; instead, several species and strains have been identified (Kent et al. 2004; Whipps et al. 2008). As such, manifestation of disease varies by species and strain, complicating diagnosis and management. In addition to bacterial strain variation, host genetic variation plays a role in susceptibility (Murray et al. 2011; Whipps et al. 2008); suggesting management strategies need to be tailored to balance biosecurity efforts with value and susceptibility of zebrafish lines.

The challenges inherent in the control of mycobacteriosis highlight the need for continued epidemiological studies connecting Mycobacterium species and strains to their potential sources, empirical data on the impact of subclinical infections, development of rapid and specific diagnostic tests, and realistic management plans with proven efficacy determined through controlled experimentation.

Mycobacteriosis in Zebrafish

Piscine mycobacteriosis is well recognized in marine and freshwater fishes, with several reviews written on the topic (Decostere et al. 2004; Frerichs 1993; Gauthier and Rhodes 2009; Parisot 1958). Reviews indicate the common occurrence in many fish species, involvement of more than one species of Mycobacterium in fish infections, ranging manifestation of disease (although typically including granuloma formation), potential for zoonotic transmission, and challenges for treatment and control. These same themes can be applied to zebrafish.

Historically, mycobacteriosis in fishes was attributable primarily to M. chelonae, M. fortuitum, and M. marinum (Frerichs 1993). However, increased study and more refined diagnostic methods (i.e., DNA sequencing) have identified at least 16 described Mycobacterium species from fish (Gauthier and Rhodes 2009; Whipps et al. 2007b). In zebrafish, at least 6 described species of mycobacteria have been reported (Table 1). These infections were first documented by Astrofsky and colleagues (2000) when M. abscessus, M. chelonae, and M. fortuitum were isolated from zebrafish exhibiting decreased survival and reproductive output. Subsequently, Kent and colleagues (2004) identified several other species from facilities experiencing different degrees of mortality. Mycobacterium peregrinum and M. haemophilum were associated with severe disease. In facilities experiencing moderate to minimal mortalities, M. chelonae and an M. chelonae–like bacterium were isolated. Watral and Kent (2007) added M. marinum to this growing list, isolating the bacterium from zebrafish from a facility supplying fish to the research community and experiencing low to moderate levels of mortality.

Table 1.

Mycobacterium species known to infect zebrafish in research facilities

| Species | Source |

|---|---|

| Mycobacterium abscessus | Astrofsky et al. (2000); Watral and Kent (2007) |

| Mycobacterium chelonae | Astrofsky et al. (2000); Kent et al. (2004); Whipps et al. (2008) |

| Mycobacterium chelonae–like | Kent et al. (2004); Whipps et al. (2007a) |

| Mycobacterium fortuitum | Astrofsky et al. (2000) |

| Mycobacterium haemophilum | Whipps et al. (2007b) |

| Mycobacterium marinum | Watral and Kent (2007) |

| Mycobacterium peregrinum | Kent et al. (2004) |

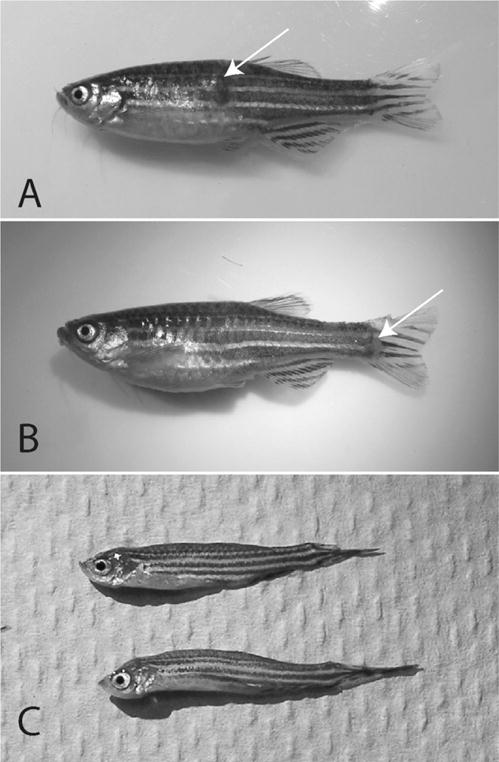

Manifestation of mycobacterial disease in zebrafish is broad ranging (Astrofsky et al. 2000; Kent et al. 2008). Externally, fish may present with nonspecific dermal lesions (Figure 1), have raised scales, or have swollen abdomens. Emaciation may occur (Figure 1) and is, in our experience, very often associated with M. haemophilum infection (Whipps et al. 2007a). Behaviorally, fish may swim erratically or be lethargic. Often, animals will show no signs of disease (Kent et al. 2004; Whipps et al. 2007a). Internally, granulomas may be visible throughout all tissues but primarily in the spleen, kidney, and liver. Diffuse systemic infections without prominent granulomas have been reported for M. haemophilum (Whipps et al. 2007a) and M. marinum (Ramsay et al. 2009b). Bacteria have been observed in the ovaries, suggesting the potential for contamination of offspring, if not vertical transmission (Kent et al. 2004). Involvement of the swim bladder (aerocystitis) is not uncommon (Whipps et al. 2008). Zebrafish are physostomus, and thus the swim bladder is directly connected to the gastrointestinal tract by a pneumatic duct. This connection provides a possible route of infection to the swim bladder. Bacteria may be observed in the intestinal epithelium and within the lumen (Whipps et al. 2007a), indicative of shedding across this surface and excretion in the feces.

Figure 1.

(A, B) External lesions (arrows) associated with Mycobacterium marinum infection in zebrafish. (C) Severe emaciation associated with Mycobacterium haemophilum infection.

Transmission of mycobacteria through ingestion has been demonstrated in other fishes (Ross 1970) and is consistent with the intestine likely being the primary route of invasion (Harriff et al. 2007). Bacteria from infected animals may be shed from skin lesions or the intestine (Noga 2010), providing a continuous source of mycobacteria in affected tanks. This highlights the importance of rapid removal of dead fish to minimize transmission through cannibalization, as well as removal of any moribund animals, which might act as reservoirs of infection. The oral route of transmission suggests food presents a risk for exposure. Testing for mycobacteria in feed at one facility (Whipps et al. 2008) yielded negative results; however, Beran and colleagues (2006) reported mycobacteria from brine shrimp eggs, one of the most commonly used feeds for zebrafish. The use of live feed may present some risk, but comprehensive screening is required to evaluate this risk. Recognition of the role of surface biofilms in persistence of mycobacteria in a system and as a potential source of infection is increasing.

It is important to note the zoonotic potential of Mycobacterium species. Transmission between fish species has been demonstrated by feeding infected tissues to other species (Ross 1970), and the same genetic strains of M. marinum have been reported from zebrafish and hybrid striped bass (Ostland et al. 2008). Mycobacterium marinum is of particular concern because it is known to infect humans. Such infections are associated with aquarium maintenance or handling food fishes (Ang et al. 2000; Aubry et al. 2002). Swimming or other direct contact with sea water (Jernigan and Farr 2000) is also associated with cases of M. marinum infection in humans. Approximately 84% of infections in humans have been associated with contact with home aquaria (Aubry et al. 2002). Other species (Table 1) are potential opportunistic human pathogens (Brown-Elliott and Wallace 2002; Whipps et al. 2007a). Whereas direct transmission from fish to humans has not been confirmed, Ostland and colleagues (2008) examined M. marinum isolates from fish and humans from the same location and found identical pulsed field gel electrophoresis cutting patterns from both hosts. These data do not rule out a common source of infection, as opposed to direct transmission, but illustrate that the same strains can infect fish and humans. Human core body temperature (37°C) is thought to limit the establishment and spread of fish-associated Mycobacterium species infections to the extremities, and, although isolates from zebrafish tend not to grow at 37°C by plate culture, replication may be observed at 37°C in macrophage culture or mouse footpad assays (Harriff et al. 2008; Kent et al. 2006). To the best of our knowledge, there are no documented cases of human mycobacteriosis associated with zebrafish handling.

Diagnostic Methods

The reported nonspecific signs of disease or complete absence of clinical signs of disease dictates that mycobacteriosis in zebrafish be confirmed by an established diagnostic method. Several tools are available, with relative benefits and limitations. Traditionally, diagnosis has relied on histological examination of zebrafish sections stained with Ziehl-Neelsen or Fite’s acid fast stain and this is the primary technique recommended by the Zebrafish International Resource Center for routine surveillance. Observation of acid-fast bacilli in tissue sections correlates well to results from culture for M. chelonae (Whipps et al. 2008) and may have improved detection for difficult to grow species such as M. haemophilum (Whipps et al. 2007a) and M. marinum (Ramsay et al. 2009b). Histology also has the advantage that most of the major internal organs of a zebrafish can be examined in a single section. The most important disadvantage of diagnosis using acid-fast stained sections is that the species of bacterium cannot be readily identified. Touch imprints of spleen, kidney, or liver stained with Kinyoun’s acid-fast stain have this same limitation with regard to identification but can be carried out quickly and are standard procedure in our diagnostic screening. For severe diffuse infections, imprint results correlate well to histology and culture (Whipps et al. 2007a), but in less severe cases tissue imprints are less consistent (C. Whipps, unpublished data). Both tissue sectioning and touch imprints are important for diagnosis when the Mycobacterium species present is difficult to grow.

Diagnosis of mycobacteria of fish in general is reviewed well by Gauthier and Rhodes (2009); the following techniques relate to implementation in zebrafish. Culture of mycobacteria from zebrafish is typically accomplished on Middlebrook 7H10 agar supplemented with oleic acid, albumin, dextrose, and catalase or Lowenstein-Jensen slants (Kent and Kubica 1985). Pretreatment with 1% cetyl pyridinium chloride prior to plating is suggested for cultures from fish tissues and strongly recommended for environmental samples to minimize background growth. Cultures are typically incubated at 28–30°C and monitored for growth for 6 to 8 weeks. Rapid growers such as M. chelonae or M. abscessus form visible colonies within 5 days. Mycobacterium marinum grows more slowly on Middlebrook 7H10 agar, forming colonies in 10 to 14 days. Alternatives to Middlebrook 7H10 agar may be more appropriate for M. marinum; for example, Ostland and colleagues (2008) used Columbia with colistin and nalidixic acid agar supplemented with 5% sheep blood. Mycobacterium haemophilum is the epitome of a slow-growing species, forming visible colonies in 6 to 8 weeks on Middlebrook 7H10 agar supplemented with oleic acid, albumin, dextrose, and catalase and 60 μM hemin (Whipps et al. 2007a). The lengthy incubation time and specialized medium may contribute to the underdiagnosis of this important zebrafish pathogen. In all cases, any suspect colonies are tested with an acid-fast stain to verify their presumptive identity as mycobacteria.

A limitation of culture is the sometimes prolonged incubation time required to identify the species. Although culture remains a gold standard for a thorough investigation and subsequent storage and cataloguing of species and strains, more rapid methods of diagnosis and identification are required. Thus, DNA-based methods have risen to the forefront as diagnostic tools in zebrafish. For routine polymerase chain reaction (PCR1) testing, the hsp65 primers of Selvaraju and colleagues (2005) are effective and have the secondary benefit of providing amplified fragments of adequate length for sequencing and identification. The sensitivity of these primers has not been determined in zebrafish. Species-specific tests are desirable for high-impact species such as M. haemophilum and have been implemented in outbreak investigations (Whipps et al. 2007a). PCR and restriction enzyme analysis (Talaat et al. 1997; Telenti et al. 1993) remains a rapid and useful technique for detection and identification of species. Quantitative PCR methods for detection of members of the genus Mycobacterium in general have been developed (Jacobs et al. 2009c; Zerihun et al. 2011) and are currently under investigation for broad-scale use in zebrafish. A desirable diagnostic test should be highly sensitive and provide at least a species-level identification simultaneously. High-resolution melting curve analysis of PCR products has promise to quickly differentiate species and has been applied to M. tuberculosis (Choi et al. 2010) and the M. avium complex (Castellanos et al. 2010). The continued challenge is an adaptable diagnostic method that can readily accommodate new strains and species as they become known.

Fresh tissues are preferred for culture, direct DNA extractions, and PCR testing, but frozen and ethanol-fixed tissues are also appropriate if culture is not absolutely necessary. PCR confirmation and species identification of mycobacteria from histological sections are less optimal but can be done (Jacobs et al. 2009a; Loeschke et al. 2005; Pourahmad et al. 2009; Zerihun et al. 2011). In fixed specimens, the duration of fixation, method of decalcification, and thickness of sections all influence the successful detection of mycobacteria by PCR. We first identified M. haemophilum as an important cause of disease in zebrafish using PCR directly on tissues (Kent et al. 2004). A common target is the small subunit (SSU) rDNA sequence, a highly conserved gene that is useful for higher taxonomic comparisons. However, there are a few species that have identical SSU rDNA sequences (Tortoli 2003) and researchers have turned to other genes, such as the ITS region of the rDNA, to better elucidate relationships of closely related Mycobacterium spp. (Roth et al. 2000). Taking this approach, we were able to identify differences in ITS sequence from two M. chelonae isolates from zebrafish that had identical SSU rDNA sequences (Kent et al. 2004). The heat shock protein 65 (hsp65) gene is also used for reliable mycobacterial species identifications (Kim et al. 2005; McNabb et al. 2006) and may differentiate between species that SSU rDNA sequence analysis cannot (Ringuet et al. 1999). We have found hsp65 to be the most rapid and reliable gene for preliminary identification of fish mycobacteria, even able to subdivide strains of M. chelonae by the variation in hsp65 (Whipps et al. 2008). Other potentially useful genes that have been used less extensively for zebrafish mycobacteria are erp (Jacobs et al. 2009a), rpoB, and sod (Devulder et al. 2005).

Subdivisions within species can be accomplished to some extent from DNA sequence data, but strain differentiation requires greater resolution and a pure culture (Whipps et al. 2008). Pulsed field gel electrophoresis effectively resolved strains of M. marinum (Ostland et al. 2008) and M. chelonae (Vanitha et al. 2003), but in our experience was less useful for M. salmoniphilum, M. peregrinum, and M. abscessus (C. Whipps, unpublished data). Furthermore, pulsed field gel electrophoresis is excessively time consuming, and more rapid methods of strain differentiation have been adopted, specifically enterobacterial repetitive intergenic consensus PCR (Sampaio et al. 2006). To supplement enterobacterial repetitive intergenic consensus PCR, other randomly amplified polymorphic DNA methods can also be used (Zhang et al. 1997). Results are rapid, can be performed in any lab with a thermocycler, and are straightforward to interpret. This method has been applied to M. chelonae from zebrafish in a single facility, distinguishing multiple strains (Whipps et al. 2008), and we continue to use this method as a routine part of our diagnostic screening of cultures from both fish and environmental sources.

Variation in Mycobacterium Species from Zebrafish

Six described Mycobacterium species have been reported from zebrafish (Table 1). As much as mycobacteriosis is caused by several different species, these species entities can be further subdivided into strains, with their own unique properties and challenges. Strain delineation is accomplished through biochemical analysis, DNA sequencing, and DNA fingerprinting methods, and multiple strains of piscine M. chelonae and M. marinum have been described (Ostland et al. 2008; Whipps et al. 2008). Other entities that we cannot ascribe to species are not listed here, with the exception of an M. chelonae–like species we had originally identified as M. chelonae (Kent et al. 2004), but subsequent phylogenetic analyses demonstrated that it was a distinct entity and should be described as a new species (Whipps et al. 2007b).

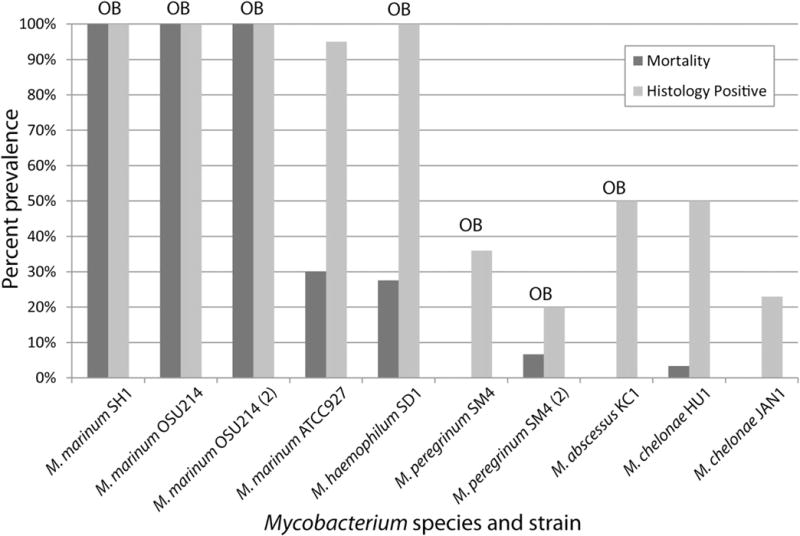

The manifestation of disease varies with species, and each can be broadly categorized as either pathogen or opportunist. The reality, however, is a continuum between these extremes, with M. chelonae, M. abscessus, M. fortuitum, and M. peregrinum tending to be associated with low-level, chronic disease, whereas M. marinum and M. haemophilum are much more virulent, causing disseminated infections and higher levels of mortality (Kent et al. 2004; Ostland et al. 2008; Watral and Kent 2007; Whipps et al. 2007a). The differences may be attributable to genetic elements associated with virulence that are present in some species and strains but not others (Harriff et al. 2008). Although not included in the study by Harriff and colleagues (2008), this is likely the case with M. haemophilum and M. marinum, as these species tend to cause mortality in experimental exposure studies (Figure 2) (Watral and Kent 2007; Whipps et al. 2007a). Mycobacterium chelonae appears to be largely an opportunistic pathogen, recognizing that multiple strains exist and may vary in their ability to cause disease (Whipps et al. 2008). Other species (M. abscessus, M. peregrinum) have been associated with increased disease, but when fish are challenged experimentally (Watral and Kent 2007) with these same strains, they may produce largely subclinical infections (Figure 2). This suggests that species and strains vary in their pathogenicity, and when less pathogenic species are associated with an outbreak, the increased mortalities may be not only related to the infection but also due to suboptimal environmental conditions.

Figure 2.

Relative pathogenicity of Mycobacterium species isolated from zebrafish in colonies experiencing minimal mortalities or Mycobacterium-associated outbreaks with significant mortality (OB). Mortality and histology were used as endpoints for all experiments. Data are summarized from studies carried out by Watral and Kent (2007) and Whipps et al. (2007b).

Environmental conditions and the nutritional and immunological state of zebrafish are probably the most important variables affecting the pathogenesis of mycobacteriosis when the cause is an opportunistic species. These conditions likely play a less significant role with overt pathogens such as M. haemophilum and M. marinum, but suboptimal environmental parameters will exacerbate these infections to a greater degree. Ramsay and colleagues (2009a, 2009b) evaluated the role of stress on cortisol level in zebrafish and the progression of disease with fish exposed to either M. chelonae or M. marinum. In the stressed zebrafish, Ramsay and colleagues (2009b) observed increased prevalence of infection for M. chelonae, greater mortality in M. marinum–exposed fish, and an increased number of disseminated infections for both pathogens when compared with unstressed controls. In striped bass, suboptimal diet influenced the progression of disease associated with M. marinum infections, with a greater likelihood of diffuse systemic disease in treatments versus controls (Jacobs et al. 2009b). Different lines of zebrafish appear to be more or less susceptible to infection based on the cross-sectional study at a single facility (Murray et al. 2011; Whipps et al. 2008). Tobin and colleagues (2010) have identified at least one locus in zebrafish important for M. marinum susceptibility, and Hegedus and colleagues (2009) and van der Sar (2009) characterized the transcriptome of infected zebrafish, suggesting that tools for comparison are available. A streamlined approach where multiple lines can be evaluated with multiple species of mycobacteria will be necessary to identify the common and unique genetic drivers of susceptibility and disease.

Mycobacteria in Biofilms

The ability for at least some, if not all, piscine mycobacteria species to persist in surface biofilms in aquatic systems (Beran et al. 2006; Whipps et al. 2008) presents additional challenges for interrupting the cycle of infection once it is established. This highlights the role of a quarantine program to minimize potential introductions of the more pathogenic mycobacteria, regular monitoring of populations to remove infected fish, and the routine cleaning and disinfection of impacted tanks and equipment. Mycobacteria are hydrophobic and oligotrophic, requiring low levels of dissolved organic carbon (Falkinham 2009). As such, they readily adhere to surfaces and are adapted to survival in “clean” water systems such as aquaria. The community of mycobacteria in biofilms can be diverse (Schulze-Röbbecke et al. 1992), with a variety of species having been isolated from aquaria (Beran et al. 2006; Whipps et al. 2007a, 2008). Although many of these species have never been reported from fish, those that are found in zebrafish have also been reported from biofilms. Furthermore, genetic comparisons of Mycobacterium isolates have revealed identical strains of M. chelonae in zebrafish (Whipps et al. 2008) and M. marinum in pompano Trachinotus carolinus (Yanong et al. 2010), as are found in associated biofilms. The finding of the same strains in fish and biofilms presents a question of which is the source and which is the sink. The feeding habits of zebrafish and the descriptive studies below suggest biofilms are indeed a source of infection, although fish shedding bacteria are also contributing to the biofilms.

In the aquatic environment, biofilms are found on all surfaces, and this biofilm and the detritus at the bottom of the tank are thought to be the source of mycobacterial infection in zebrafish. Zebrafish are thought to be generalist consumers (Lawrence 2007), primarily feeding in the water column but also on the surface and substrate (Spence et al. 2008). In our observations of fish in a sump at a large facility, zebrafish hunt for benthic organisms and slow zooplankton along the biofilm scaffolding. They are probably also eating bacteria, slime molds, and protozoa. The larvae are especially active grazers and hunters once they get to be about 8 to 10 mm. These fish and larvae are probably selecting specific organisms but are likely consuming mycobacteria incidentally. Given the suggested oral transmission route (Harriff et al. 2007), zebrafish may be infected by the oral route by grazing on the microflora of the biofilm and detritus. The following are our observations on mycobacteria in biofilms relating to infections at two facilities.

Sump Fish Case Study: Facility A

Dense mature biofilms in the dirty sump yielded the highest concentrations of mycobacteria by acid-fast staining and PCR testing, as compared with frequently cleaned, minimal density sump tank biofilms. Sentinel fish (raised from larvae stage) from tanks that were frequently cleaned with minimal density biofilms have been mycobacteria negative for 3 years. The sentinel fish from the dense mature biofilm tanks yielded at least 1% fish positive for mycobacteria on histology each year for the past 3 years. It was determined that the species of mycobacteria causing disease in the fish and the species of mycobacteria found in the biofilm and detritus were the same, M. fortuitum. Frequent elimination of detritus and minimization of the biofilm by cleaning or tank changes should decrease fish exposure to mycobacterial pathogens; this seems to be especially true when raising larval stages of fish. Mycobacterium fortuitum infection appears to be a manageable disease but is not usually entirely eliminated from a large recirculation zebrafish system.

Biofilm Monitoring: Facility B

An initial evaluation and continued monitoring of biofilms was conducted in a facility that experienced morbidity and mortality in zebrafish as a result of M. haemophilum infection. Mycobacteriosis was initially diagnosed by histologic methods and later confirmed with PCR. Following the diagnosis of several cases of M. haemophilum infection, surface biofilm sampling was conducted to determine the identity of existing mycobacterial florae and to monitor this community following disinfection and repopulation of the system (Table 2). Initially, M. chelonae and M. abscessus were the only species isolated from the biofilms. Unlike our earlier studies of M. haemophilum (Whipps et al. 2007a), we were unable to detect this bacterium in the biofilms.

Table 2.

Ongoing biofilm sampling of a zebrafish system over 21 months

| Date | System status | Location | Culture result | Species identificationa |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| September 9, 2009 | System with fish | Gutters | Positive | Mycobacterium chelonae |

| Tank with fish | Positive | M. chelonae | ||

| March 22, 2010 | System with fish | Gutters | Positive | M. chelonae |

| Tank with fish | Positive | Mycobacterium abscessus | ||

| Sump | Positive | M. chelonae | ||

| July 19, 2010 | System bleached, no fish | Gutters, tank, sump | All negative | |

| August 10, 2010 | System bleached and scrubbed, no fish | Gutters, tank, sump | All negative | |

| October 8, 2010 | System reassembled, no fish | Gutters, tank, sump | All negative | |

| November 15, 2010 | Fish placed on system | |||

| November 29, 2010 | System with fish | Gutters, tank, sump | All negative | |

| December 13, 2010 | System with fish | Gutters, tank, sump | All negative | |

| December 27, 2010 | System with fish | Gutter | Negative | |

| Populated tank | Positive (multiple) | M. abscessus, Mycobacterium phocaicum, Mycobacterium gordonae | ||

| Sump | Positive (multiple) | M. phocaicum, M. chelonae | ||

| January 10, 2011 | System with fish | Gutter | Positive | M. gordonae |

| Populated tank | Negative | |||

| Sump | Positive | M. phocaicum | ||

| January 24, 2011 | System with fish | Gutters, tank, sump | All negative | |

| February 7, 2011 | System with fish | Gutter | Positive (multiple) | M. phocaicum, Mycobacterium fortuitum |

| Populated tank | Positive (multiple) | M. phocaicum, M. chelonae | ||

| Sump | Positive | M. phocaicum | ||

| February 22, 2011 | System with fish | Gutter | Positive (multiple) | M. chelonae, M. phocaicum |

| Populated tank | Positive | M. chelonae | ||

| Sump | Positive (multiple) | Mycobacterium mucogenicum | ||

| March 7, 2011 | System with fish | Gutter | Positive | M. phocaicum |

| Populated tank | Positive (multiple) | M. chelonae, M. phocaicum | ||

| Sump | Positive (multiple) | M. chelonae | ||

| March 21, 2011 | System with fish | Gutter | Positive | M. chelonae |

| Populated tank | Positive | M. phocaicum | ||

| Sump | Positive | M. phocaicum |

Swabs were used to collect surface biofilms from three locations within the system on a repeated basis. Biofilms were processed as described by Whipps et al. (2008) and grown on MB7H10 medium supplemented with hemin at 28°C for 8 wk. Where “multiple” is noted, several colony types were observed on the culture medium.

Species identification based solely on BLAST searching of hsp65 DNA sequences. In some cases an equally likely match was obtained (e.g., M. phocaicum and M. mucogenicum).

The aquatic housing system was depopulated and all nonreplaceable system components were thoroughly disinfected with 1000 ppm bleach buffered to a pH of 7. Following disinfection, biofilm samples were evaluated from all locations on the system and proven to be negative by both culture and PCR (Table 2) before introducing larvae from bleached disinfected embryos (25–50 ppm for 10 min). Less than 3 weeks after the introduction of larvae, a biofilm sample from a populated tank was again PCR positive for mycobacteria. By culture methods, mycobacteria remained below detectable levels after fish were placed on the system for approximately 6 weeks, at which time mycobacteria were isolated from the populated tank and system sump. Continued biweekly sampling in subsequent months demonstrated colonization of the system by at least five species: M. abscessus, M. chelonae, M. fortuitum, M. gordonae, and M. phocaicum/mucogenicum. These species continued to be found throughout the biweekly biofilm sampling until June 2011 when monitoring of biofilms stopped. Mycobacteriosis was identified in an occasional fish following the clean-up (M. chelonae), but M. haemophilum was not detected again. Furthermore, there have been no indications of M. haemophilum outbreaks in this facility to date (September 2012). This demonstrates several key points. First, the decontamination was effective in killing the mycobacteria present in the system. Second, by culture, mycobacteria did not reach detectable levels until well after fish were stocked into the system, suggesting that although mycobacteria are oligotrophic, the organic load contribution of fish likely enhances growth and establishment of biofilms. Finally, the Mycobacterium community was different before and after disinfection, with an M. phocaicum–like organism dominating in more recent biofilm samples. This may represent an early colonizer and transitional community, but M. phocaicum is not a bacterium that has been identified from zebrafish and may occupy substrate that prevents colonization of other species. These data also suggest that, although biofilms may indeed be a source of infection for fish, the initial colonization by the fish-specific pathogens likely requires an animal source.

Control and Treatment

Recommendation for control of zebrafish diseases were recently reviewed (Kent et al. 2009), and the importance of quarantine, disinfection, a functioning ultraviolet system, and sentinel programs to monitor for disease were highlighted. These are broadly applicable to mycobacteria, and aspects of these have been discussed (Astrofsky et al. 2000; Kent et al. 2004; Whipps et al. 2008). Elimination of mycobacteria from a facility once it has been established is challenging, and depopulation is often recommended (Francis-Floyd and Yanong 1999). This may not be feasible in all cases, and thus management of the endemic disease is often the appropriate choice. Minimizing any potential source of infection by cleaning tanks to reduce biofilms or cleaning and upgrading ultraviolet sterilization for water likely helps drive down free bacteria in the system. Removal of sick animals and affected tanks rapidly will minimize spread. The standard practice of bleaching eggs for 10 minutes at 50 ppm (Westerfield 2000) has unknown efficacy for killing the many different strains of mycobacteria found in zebrafish laboratories. Further complicating this matter is that mycobacteria are known to be differentially susceptible to disinfection, whether planktonic or in biofilms (Bardouniotis et al. 2003; Steed and Falkinham 2006). Ferguson and colleagues (2007) highlighted the importance of adjustment to pH 7 of the bleach solution as well as validation of concentration using a chlorine meter. Mainous and Smith (2005) reported that 50 ppm bleach was ineffective at killing M. marinum in culture after a 10-minute exposure, requiring 60 minutes for complete germicidal activity. Studies under way in the Whipps laboratory using pH-adjusted bleach at 50 ppm for 10 minutes show complete germicidal effect for M. chelonae cultures at 103, 104, and 105 colony-forming units per milliliter. The efficacy of bleach on biofilms of these same bacteria, such as those that may be present on zebrafish eggs, is not known. Bacteria harbored within eggs are protected from disinfection and present a risk for contamination of other eggs. Vaccination with extracellular mycobacterial products (Chen et al. 1996) and DNA vaccines (Pasnik and Smith 2005) have demonstrated the efficacy of these techniques in stimulating specific antibody production and eliciting an immune response. Similarly, vaccination with attenuated mycobacteria shows some promise for protective immunity in zebrafish (Cui et al. 2010) and other aquaculture species (Kato et al. 2011).

Little is known about the efficacy of antibiotic treatment for mycobacteriosis in fish because treatment in food fish aquaculture is impractical due to high costs of antibiotics, long treatment regimens, and concerns about use of these powerful human drugs in fish destined for human consumption. Nevertheless, treatment of infected zebrafish may be appropriate when extremely valuable strains or populations are involved. Subclinical infections in valuable lines of zebrafish may need to be treated to remove this confounding factor from experiments planned for these animals or minimize the chances of vertical transmission when breeding new fish for research. Mycobacteria are known to be susceptible to rifampicin and Kawakami and Kusuda (1990) reported that rifampicin, streptomycin, and erythromycin were effective for reducing mortalities associated with a Mycobacterium sp. in cultured yellowtail (Seriola quinqueradiata). In this study, however, only an initial dose at the time of exposure and a dose at 24 hours postexposure were given to the fish. Although infection was not completely eliminated in fish after 7 weeks, more regular treatments may have been effective. In contrast, Hedrick and colleagues (1987) found rifampicin treatment of M. marinum–infected striped bass ineffective after 60 days of feeding the bass antibiotic-supplemented feed. These differences across host species suggest that results obtained from one fish species may not be applicable to all species, and that treatment must be tested specifically in zebrafish to determine if it is an effective option.

Summary and Future Directions

The impacts of mycobacteria are clear when associated with mortalities and decreased reproductive output in zebrafish. What is less well understood is the impact of subclinical infections and the influence of these infections in specific areas of research. Such nonexperimental variation magnifies the importance of evaluating the influences these infections may have when zebrafish are used as models for studies on disease, immunology, ecotoxicology, and so on. The more serious pathogens, M. haemophilum and M. marinum, are those of greatest concern for disease outbreaks, but the opportunists still present a significant concern because they often go unnoticed and their impacts are less well known. Complete elimination of mycobacteria from a large facility supplied with recirculating water is probably not feasible given the ease with which mycobacteria can colonize such systems. Through strict biosecurity protocols, it is worthwhile to attempt to exclude the more virulent pathogens that may colonize a facility initially through the introduction of infected fish from another facility where the pathogen is endemic. Elimination of all mycobacteria in small-scale operations with flowthrough water may be possible when it is called for in quarantine or when using highly susceptible fish. Monitoring and management of the disease are sure to be the focus of continued research that emphasizes mycobacterial ecology, biology, and pathogenesis in zebrafish so that management actions can be better informed.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the three anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments and suggestions. CM Whipps thanks Hadi L. Jabbar (State University of New York College of Environmental Science and Forestry) for bacterial isolation and PCR on fish and biofilm samples. C Lieggi acknowledges the assistance of Yuri Igarashi for sample collection and Aziz Toma for culturing and shipping all of the samples originating at Weill Cornell Medical College.

Footnotes

Abbreviation that appears ≥3x throughout this article: PCR, polymerase chain reaction

Contributor Information

Christopher M. Whipps, Assistant professor in the Department of Environmental and Forest Biology, State University of New York College of Environmental Science and Forestry in Syracuse, New York.

Christine Lieggi, Associate director and head of veterinary services at the Research Animal Resource Center, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center and Weill Cornell Medical College in New York, New York.

Robert Wagner, Chief of surgical veterinary services and associate professor in the Division of Laboratory Animal Medicine, University of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

References

- Ang P, Rattana-Apiromyakij N, Goh CL. Retrospective study of Mycobacterium marinum skin infections. Int J Dermatol. 2000;39:343–347. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.2000.00916.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Astrofsky KM, Schrenzel MD, Bullis RA, Smolowitz RM, Fox JG. Diagnosis and management of atypical Mycobacterium spp. infections in established laboratory zebrafish (Brachydanio rerio) facilities. Comp Med. 2000;50:666–672. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aubry A, Chosidow O, Caumes E, Robert J, Cambau E. Sixty-three cases of Mycobacterium marinum infection: Clinical features, treatment, and antibiotic susceptibility of causative isolates. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:1746–1752. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.15.1746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker D. Natural Pathogens of Laboratory Animals: Their Effects on Research. Herndon VA: ASM Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Bardouniotis E, Ceri H, Olson ME. Biofilm formation and biocide susceptibility testing of Mycobacterium fortuitum and Mycobacterium marinum. Curr Microbiol. 2003;46:28–32. doi: 10.1007/s00284-002-3796-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beran V, Matlova I, Dvorska L, Svastova P, Palik I. Distribution of mycobacteria in clinically healthy ornamental fish and their aquarium environment. J Fish Dis. 2006;29:383–393. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2761.2006.00729.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown-Elliott BA, Wallace RJ., Jr Clinical and taxonomic status of pathogenic nonpigmented or late-pigmenting rapidly growing mycobacteria. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2002;15:716–746. doi: 10.1128/CMR.15.4.716-746.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castellanos E, Aranaz A, De Buck J. PCR amplification and high-resolution melting curve analysis as a rapid diagnostic method for genotyping members of the Mycobacterium avium–intracellulare complex. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2010;16:1658–1662. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2010.03198.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen SC, Yoshida T, Adams A, Thompson KD, Richards RH. Immune response of rainbow trout to extracellular products of Mycobacterium spp. J Aquat Anim Health. 1996;8:216–222. [Google Scholar]

- Choi GE, Lee SM, Yi J, Hwang SH, Kim HH, Lee EY, Cho EH, Kim JH, Kim HJ, Chang CL. High-resolution melting curve analysis for rapid detection of rifampin and isoniazid resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis clinical isolates. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48:3893–3898. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00396-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui Z, Samuel-Shaker D, Watral V, Kent ML. Attenuated Mycobacterium marinum protects zebrafish against mycobacteriosis. J Fish Dis. 2010;33:371–375. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2761.2009.01115.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decostere A, Hermans K, Haesebrouck F. Piscine mycobacteriosis: A literature review covering the agent and the disease it causes in fish and humans. Vet Microbiol. 2004;99:159–166. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2003.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devulder G, Pérouse de Montclos M, Flandrois JP. A multigene approach to phylogenetic analysis using the genus Mycobacterium as a model. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2005;55:293–302. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.63222-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellett F, Lieschke GJ. Zebrafish as a model for vertebrate hematopoiesis. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2010;10:563–570. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2010.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falkinham JO. Surrounded by mycobacteria: Nontuberculous mycobacteria in the human environment. J Appl Microbiol. 2009;107:356–367. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2009.04161.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falkinham JO, Norton CD, LeChevallier MW. Factors influencing numbers of Mycobacterium avium, Mycobacterium intracellulare, and other mycobacteria in drinking water distribution systems. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2001;67:1225–1231. doi: 10.1128/AEM.67.3.1225-1231.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson J, Watral V, Schwindt A, Kent ML. Spores of two fish microsporidia (Pseudoloma neurophilia and Glugea anomola) are highly resistant to chlorine. Dis Aquat Org. 2007;76:205–214. doi: 10.3354/dao076205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis-Floyd R, Yanong RPE. Mycobacteriosis in fish. Gainesville: University of Florida, Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences; 1999. (Fact Sheet VM-96). [Google Scholar]

- Frerichs GN. Mycobacteriosis: Nocardiosis. In: Inglis V, Roberts RJ, Bromage NR, editors. Bacterial Diseases of Fish. Oxford: Blackwell; 1993. pp. 219–233. [Google Scholar]

- Gauthier DT, Rhodes MW. Mycobacteriosis in fishes: A review. Vet J. 2009;180:33–47. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2008.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harriff MJ, Bermudez LE, Kent ML. Experimental exposure of zebrafish (Danio rerio Hamilton) to Mycobacterium marinum and Mycobacterium peregrinum reveals the gastrointestinal tract as the primary route of infection: A potential model for environmental mycobacterial infection. J Fish Dis. 2007;30:587–600. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2761.2007.00839.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harriff MJ, Wu M, Kent ML, Bermudez LE. Species of environmental mycobacteria vary in their ability to grow in human, mouse, and carp macrophages, associated with the absence of mycobacterial virulence genes observed by DNA microarray hybridization. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2008;74:275–285. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01480-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedrick RP, McDowell T, Groff J. Mycobacteriosis in cultured striped bass from California. J Wildl Dis. 1987;23:391–395. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-23.3.391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegedus Z, Zakrzewska A, Agoston VC, Ordas A, Rácz P, Mink M, Spaink HP, Meijer AH. Deep sequencing of the zebrafish transcriptome response to mycobacterium infection. Mol Immunol. 2009;46:2918–2930. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2009.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs JM, Howard DW, Rhodes MR, Newman MW, May EB, Harrell RM. Historical presence (1975–1985) of mycobacteriosis in Chesapeake Bay striped bass Morone saxatilis. Dis Aquat Organ. 2009a;85:181–186. doi: 10.3354/dao02081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs JM, Rhodes MR, Baya A, Reimschuessel R, Townsend H, Harrell RM. Influence of nutritional state on the progression and severity of mycobacteriosis in striped bass Morone saxatilis. Dis Aquat Organ. 2009b;87:183–197. doi: 10.3354/dao02114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs J, Rhodes M, Sturgis B, Wood B. Influence of environmental gradients on the abundance and distribution of Mycobacterium spp. in a coastal lagoon estuary. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2009c;75:7378–7384. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01900-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jernigan JA, Farr BM. Incubation period and sources of exposure for cutaneous Mycobacterium marinum infection: Case report and review of the literature. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;31:439–443. doi: 10.1086/313972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato G, Kato K, Saito K, Pe Y, Kondo H, Aoki T, Hirono I. Vaccine efficacy of Mycobacterium bovis BCG against Mycobacterium sp. infection in amberjack Seriola dumerili. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2011;30:467–472. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2010.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawakami K, Kusuda R. Efficacy of rifampicin, streptomycin and erythromycin against experimental Mycobacterium infection in cultured yellowtail. B Jpn Soc Sci Fish. 1990;56:51–53. [Google Scholar]

- Kent PT, Kubica GP. Public health mycobacteriology: A guide for the level III laboratory. Atlanta: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Kent ML, Bishop-Stewart JK. Transmission and tissue distribution of Pseudoloma neurophilia (Microsporidia) of zebrafish, Danio rerio (Hamilton) J Fish Dis. 2003;26:423–426. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2761.2003.00467.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kent ML, Matthews JL, Bishop-Stewart JK, Whipps CM, Watral V, Poort M, Bermudez L. Mycobacteriosis in zebrafish (Danio rerio) research facilities. Comp Biochem Physiol C Toxicol Pharmacol. 2004;138:383–390. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2004.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kent ML, Watral V, Wu M, Bermudez L. In vivo and in vitro growth of Mycobacterium marinum at homoeothermic temperatures. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2006;257:69–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2006.00173.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kent ML, Spitsbergen JM, Matthews JM, Fournie JW, Westerfield M. Diseases of zebrafish in research facilities. 2008 Available online at http://zebrafish.org/zirc/health/diseaseManual.php (accessed October 8, 2012)

- Kent ML, Feist SW, Harper C, Hoogstraten-Miller S, Law JM, Sánchez-Morgado JM, Tanguay RL, Sanders GE, Spitsbergen JM, Whipps CM. Recommendations for control of pathogens and infectious diseases in fish research facilities. Comp Biochem Physiol C Toxicol Pharmacol. 2009;149:240–248. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpc.2008.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kent ML, Buchner C, Watral VG, Sanders JL, LaDu J, Peterson TS, Tanguay RL. Development and maintenance of a specific pathogen free (SPF) zebrafish research facility for Pseudoloma neurophilia. Dis Aquat Org. 2011;95:73–79. doi: 10.3354/dao02333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kent ML, Harper C, Wolf JC. Documented and potential research impacts of subclinical diseases in zebrafish. ILAR J. 2012;53:126–134. doi: 10.1093/ilar.53.2.126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H, Kim SH, Shim TS, Kim MN, Bai GH, Park YG, Lee SH, Chae GT, Cha CY, Kook YH, Kim BJ. Differentiation of Mycobacterium species by analysis of the heat-shock protein 65 gene (hsp65) Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2005;55:1649–1656. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.63553-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence C. The husbandry of zebrafish (Danio rerio): A review. Aqaculture. 2007;269:1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Lesley R, Ramakrishnan L. Insights into early mycobacterial pathogenesis from the zebrafish. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2008;11:277–83. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2008.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieschke GJ, Currie PD. Animal models of human disease: Zebrafish swim into view. Nat Rev Genet. 2007;8:353–367. doi: 10.1038/nrg2091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loeschke S, Goldmann T, Vollmer E. Improved detection of mycobacterial DNA by PCR in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues using thin sections. Pathol Res Pract. 2005;201:37–40. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2004.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mainous ME, Smith SA. Efficacy of common disinfectants against Mycobacterium marinum. J Aquat Anim Health. 2005;17:284–288. [Google Scholar]

- McNabb A, Adie K, Rodrigues M, Black WA, Isaac-Renton J. Direct identification of mycobacteria in primary liquid detection media by partial sequencing of the 65-kilodalton heat shock protein gene. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44:60–66. doi: 10.1128/JCM.44.1.60-66.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray KN, Bauer J, Tallen A, Matthews JL, Westerfield M, Varga ZM. Characterization and management of asymptomatic Mycobacterium infections at the Zebrafish International Resource Center. JAALAS. 2011;50:675–679. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noga E. Fish Disease: Diagnosis and Treatment. Malden MA: Blackwell Publishing; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Norton W, Bally-Cuif L. Adult zebrafish as a model organism for behavioural genetics. BMC Neurosci. 2010;11:90. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-11-90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostland VE, Watral V, Whipps CM, Austin FW, St-Hilaire S, Westerman ME, Kent ML. Biochemical, molecular, and virulence studies of select Mycobacterium marinum strains in hybrid striped bass (Morone chrysops × M. saxatilis) and zebrafish (Danio rerio) Dis Aquat Org. 2008;79:107–118. doi: 10.3354/dao01891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parisot TJ. Tuberculosis in fish: A review of the literature with a description of the disease in salmonid fish. Bacteriol Rev. 1958;22:240–245. doi: 10.1128/br.22.4.240-245.1958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasnik DJ, Smith SA. Immunogenic and protective effects of a DNA vaccine for Mycobacterium marinum in fish. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 2005;103:195–206. doi: 10.1016/j.vetimm.2004.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pourahmad F, Thompson KD, Adams A, Richards RH. Detection and identification of aquatic mycobacteria in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded fish tissues. J Fish Dis. 2009;32:409–419. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2761.2009.01030.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsay JM, Feist GW, Varga ZM, Westerfield M, Kent ML, Schreck CB. Whole-body cortisol response of zebrafish to acute net handling stress. Aquaculture. 2009a;297:157–162. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2009.08.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsay JM, Watral V, Schreck CB, Kent ML. Husbandry stress exacerbates mycobacterial infections in adult zebrafish, Danio rerio (Hamilton) J Fish Dis. 2009b;32:931–941. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2761.2009.01074.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ringuet H, Akoua-Koffi C, Honore S, Varnerot A, Vincent V, Berche P, Gaillard JL, Pierre-Audigier C. hsp65 Sequencing for identification of rapidly growing mycobacteria. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:852–857. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.3.852-857.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross AJ. Mycobacteriosis among Pacific salmonid fishes. In: Sniesko SF, editor. A symposium on diseases of fishes and shellfishes. Washington: American Fisheries Society; 1970. pp. 279–283. [Google Scholar]

- Roth A, Reischl U, Streubel A, Naumann L, Kroppenstedt RM, Habicht M, Fischer M, Mauch H. Novel diagnostic algorithm for identification of mycobacteria using genus-specific amplification of the 16S–23S rRNA gene spacer and restriction endonucleases. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:1094–1104. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.3.1094-1104.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampaio JL, Viana-Niero C, de Freitas D, Hofling-Lima AL, Leao SC. Enterobacterial repetitive intergenic consensus PCR is a useful tool for typing Mycobacterium chelonae and Mycobacterium abscessus isolates. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2006;55:107–118. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2006.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders J, Watral V, Kent M. Microsporidiosis in zebrafish research facilities. ILAR J. 2012;53:106–113. doi: 10.1093/ilar.53.2.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulze-Röbbecke R, Janning B, Fischer R. Occurrence of mycobacteria in biofilm samples. Tubercle Lung Dis. 1992;73:141–144. doi: 10.1016/0962-8479(92)90147-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selvaraju SB, Khan IU, Yadav JS. A new method for species identification and differentiation of Mycobacterium chelonae complex based on amplified hsp65 restriction analysis (AHSPRA) Mol Cell Probes. 2005;19:93–99. doi: 10.1016/j.mcp.2004.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spence R, Gerlach G, Lawrence C, Smith C. The behaviour and ecology of the zebrafish, Danio rerio. Biol Rev Camb Philos Soc. 2008;83:13–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-185X.2007.00030.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley KA, Curtis LR, Simonich SL, Tanguay RL. Endosulfan I and endosulfan sulfate disrupts zebrafish embryonic development. Aquat Toxicol. 2009;95:355–361. doi: 10.1016/j.aquatox.2009.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steed KA, Falkinham JO., 3rd Effect of growth in biofilms on chlorine susceptibility of Mycobacterium avium and Mycobacterium intracellulare. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2006;72:4007–4011. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02573-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talaat AM, Reimschuessel R, Trucksis M. Identification of mycobacteria infecting fish to the species level using polymerase chain reaction and restriction enzyme analysis. Vet Microbiol. 1997;58:229–237. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1135(97)00120-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Telenti A, Marchesi F, Balz M, Bally F, Böttger EC, Bodmer T. Rapid identification of mycobacteria to the species level by polymerase chain reaction and restriction enzyme analysis. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:175–178. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.2.175-178.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobin DM, Vary JC, Jr, Ray JP, Walsh GS, Dunstan SJ, Bang ND, Hagge DA, Khadge S, King MC, Hawn TR, Moens CB, Ramakrishnan L. The lta4h locus modulates susceptibility to mycobacterial infection in zebrafish and humans. Cell. 2010;140:717–730. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tortoli E. Impact of genotypic studies on mycobacterial taxonomy: The new mycobacteria of the 1990s. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2003;16:319–354. doi: 10.1128/CMR.16.2.319-354.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Sar AM, Appelmelk BJ, Vandenbroucke-Grauls CM, Bitter W. A star with stripes: Zebrafish as an infection model. Trends Microbiol. 2004;12:451–457. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2004.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Sar AM, Spaink HP, Zakrzewska A, Bitter W, Meijer AH. Specificity of the zebrafish host transcriptome response to acute and chronic mycobacterial infection and the role of innate and adaptive immune components. Mol Immunol. 2009;46:2317–2332. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2009.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanitha JD, Venkatasubramani R, Dharmalingam K, Paramasivan CN. Large-restriction-fragment polymorphism analysis of Mycobacterium chelonae and Mycobacterium terrae isolates. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2003;69:4337–4341. doi: 10.1128/AEM.69.7.4337-4341.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watral V, Kent ML. Pathogenesis of Mycobacterium spp. in zebrafish (Danio rerio) from research facilities. Comp Biochem Physiol C Toxicol Pharmacol. 2007;145:55–60. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpc.2006.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westerfield M. The Zebrafish Book A Guide for the Laboratory Use of Zebrafish (Danio rerio) 4th. Eugene: University of Oregon Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Whipps CM, Butler WR, Pourahmad F, Watral VG, Kent ML. Molecular systematics support the revival of Mycobacterium salmoniphilum (ex Ross 1960) sp. nov., nom. rev., a species closely related to Mycobacterium chelonae. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2007a;57:2525–2531. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.64841-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whipps CM, Dougan ST, Kent ML. Mycobacterium haemophilum infections of zebrafish (Danio rerio) in research facilities. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2007b;270:21–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2007.00671.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whipps CM, Matthews JL, Kent ML. Distribution and genetic characterization of Mycobacterium chelonae in laboratory zebrafish (Danio rerio) Dis Aquat Organ. 2008;82:45–54. doi: 10.3354/dao01967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanong RP, Pouder DB, Falkinham JO., 3rd Association of mycobacteria in recirculating aquaculture systems and mycobacterial disease in fish. J Aquat Anim Health. 2010;22:219–223. doi: 10.1577/H10-009.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zerihun MA, Hjortaas MJ, Falk K, Colquhoun DJ. Immunohistochemical and Taqman real-time PCR detection of mycobacterial infections in fish. J Fish Dis. 2011;34:235–246. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2761.2010.01231.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Rajagopalan M, Brown BA, Wallace RJ., Jr Randomly amplified polymorphic DNA PCR for comparison of Mycobacterium abscessus strains from nosocomial outbreaks. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:3132–3139. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.12.3132-3139.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]