Abstract

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) and the common commensal and opportunistic pathogen, non-typeable Haemophilus influenzae (NTHi) both serve as a frequent cause of respiratory infection in children. Although it is well established that some respiratory viruses can increase host susceptibility to secondary bacterial infections, few studies have examined how commensal bacteria could influence a secondary viral response. Here, we examined the impact of NTHi exposure on a subsequent RSV infection of human bronchial epithelial cells (16HBE14o-). Co-culture of 16HBE14o- cells with NTHi 2019 resulted in inhibition of viral gene expression following RSV infection. 16HBE14o- cells co-cultured with heat-killed NTHi 2019 failed to protect against an RSV infection, indicating that protection requires live bacteria. However, NTHi did not inhibit influenza A virus replication, indicating that NTHi-mediated protection was RSV-specific. Our data demonstrates that prior exposure to a commensal bacterium such as NTHi can elicit protection against a subsequent RSV infection.

Keywords: Haemophilus influenzae, respiratory syncytial virus, human bronchial epithelial cells

Introduction

Viral and bacterial co-infections are increasingly detected in patients with respiratory infections. Several studies have examined the impact respiratory viruses have on secondary bacterial infections, showing that respiratory viruses such as influenza A virus (IAV) can increase susceptibility to a secondary bacterial infection (1-3). However, it is currently unclear how the presence of commensal bacteria may impact a subsequent viral infection.

Non-typeable Haemophilus influenza (NTHi) is frequent commensal bacteria found in the upper respiratory tract (4-6). Studies have shown that viral infections of respiratory epithelial cells due to respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) can increase the adherence of NTHi to these cells (7, 8). While NTHi colonization of the upper airways is generally benign, under the proper conditions, it can allow for opportunistic infections to develop, resulting in bacterial conjunctivitis, otitis media, sinusitis, bronchitis or pneumonia (9). RSV is the most common viral respiratory pathogen found in conjunction with NTHi and can often lead to the development of bronchitis, pneumonia or otitis media (10, 11).

In this study we sought to determine the impact of prior exposure of NTHi on human bronchial epithelial (16HBE14o-) cells. 16HBE14o- cells co-cultured with NTHi as few as 6 hr prior to an RSV infection exhibited a significant reduction in viral gene expression. Live bacteria were required to elicit this protection, as exposure to heat-killed bacteria failed to protect 16HBE14o- cells from an RSV infection. NTHi 2019ΔlicD, which lacks expression of phosphorylcholine, thus inhibiting its ability to enter the 16HBE14o- cells, exhibited reduced protection indicating that bacteria must successfully invade the epithelial cell to induce optimal protection. Importantly, this inhibition appears to be specific to RSV, as NTHi did not mediate protection of 16HBE14o- cells from an IAV infection.

Material and Methods

Virus growth and purification

The A2 strain of RSV was propagated in HEp-2 cells (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA). Infected cells were removed with a cell scraper and both cells and supernatant were centrifuged at 2000 × g for 15 min at 4°C. Pooled supernatants and 50% Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) 8000 were combined at a 1:5 ratio (vol:vol) and slowly mixed for 2 hr at 4°C. The mixture was centrifuged at 9,481 × g for 30 min at 4°C. The supernatant was discarded and the pellet was resuspended in 9 ml of 20% sucrose. A sucrose gradient consisting of 60% and 35% sucrose was prepared and 9 ml of RSV-sucrose was carefully added onto the gradient and centrifuged at 243,050 × g for 1 hr at 4°C. The virus band between the 35% and 60% sucrose layers was removed from each tube, pooled, and aliquoted prior to being flash frozen in liquid nitrogen. RSV was stored at −80°C. A recombinant RSV engineered to express green fluorescent protein (GFP) was obtained from Mark Peeples (Columbus Children's Research Hospital, Columbus, OH) (12). Mouse-adapted influenza A virus A/PR/8/34 was grown in the allantoic fluid of 10 day-old embryonated chicken eggs as previously described (13).

Bacteria preparation

NTHi 2019/S10/V6 (NTHi 2019) is a clinical isolate that has been described previously (14, 15). NTHi 2019 was recently recovered during an NIH sponsored human experimental colonization study, and it has been shown that the majority of the population of organisms in this strain express phosphorylcholine (15). NTHi 2019ΔlicD is a chromosomal mutant in phosphorylcholine transferase (16). Due to this mutation, the organism lacks phosphorylcholine on the surface lipooligosaccharide (LOS) (15). All NTHi strains were grown from frozen stocks onto brain heart infusion agar plates supplemented with 10 μg hemin/ml and 10 μg of NAD/ml at 37°C in 5% CO2. A piliated clinical isolate of Neisseria cinerea, which is a commensal bacteria of the human nasopharnx, was grown as previously described (17). Heat-inactivated bacteria were obtained by incubation of the cultures for 30 mins at 65°C.

Human bronchial epithelial (16HBE14o-) cell line infections

16HBE14o- cells, which are SV40 transformed human airway epithelial cells, were a gift from Dr. D. C. Gruenert (University of California, San Francisco, CA) (18). 16HBE14o- cells were maintained in Minimum Essential Media (MEM) (Gibco, Grand Island, NY) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FCS; Atlanta Biologicals, Lawrenceville, GA), 2 mM l-glutamine, 0.1 mM nonessential amino acids, and 1 mM sodium pyruvate (all from Gibco). 16HBE14o- cells were seeded in either 6 or 24 well tissue culture plates and co-cultured with NTHi at an initial bacterium:cell ratio of 1:1 for either 6 or 24 hr. Following bacteria exposure, the 16HBE14o- cultures were infected with unlabeled purified RSV or purified RSV-GFP (12) at an MOI of either 1 or 10. When indicated, NTHi and RSV were co-incubated together on ice for 30 mins prior to 16HBE14o- infection for 48 hr. In selected experiments the NTHi-exposed 16HBE14o- cells were infected with IAV at an MOI of either 0.1 or 1 for 48 hr.

Real-time PCR

Total cellular RNA was isolated from 16HBE14o- cells following RSV infections at the indicated time points. 16HBE14o- cells were washed in 1 ml of Trizol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and supernatants collected. RNA was purified by chloroform and isopropyl alcohol extractions. cDNA was made using SuperScript VILO cDNA synthesis kit for RT-PCR (Invitrogen). Real-time PCR was performed to detect either the nucleocapsid (N) gene of RSV or the nucleoprotein (NP) gene of IAV. Real-time PCR was performed using a Taqman Universal PCR master mix on an Applied Biosystems 7300 real-time PCR machine (Foster City, CA) under standard thermal cycling parameters. RSV N gene and IAV NP gene primers and probes have been previously described (19, 20). All probes were synthesized to contain a 5’ 6-carboxy-fluorescein reporter dye and 3’ carboxytetramethylrhodamince quencher dye (Integrated DNA Technologies, Coralville, IA). Samples were compared to known standard dilutions of plasmids containing each individual gene. Total copy numbers for each gene were calculated based on the calculated copy numbers in each sample and the total amount of RNA from each well.

Microscopy

16HBE14o- cells were grown on collagen-coated coverslips and infected with NTHi and RSV as described above. At 48 hr following RSV infection, the 16HBE14o- cells were fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde. Samples were washed with PBS and then permeabilized in 100% methanol at −20°C for 10 mins. Samples were blocked with 5% normal goat serum for 1 hr at room temperature and labeled with a murine monoclonal antibody that binds to the stable 2-keto-3-deoxyoctulosonic acid epitope on the LOS of Haemophilus influenzae (21, 22) for 2 hr at room temperature. 16HBE14o- cells were washed three times for 2 mins with PBS and incubated with goat anti-mouse IgG conjugated to AlexaFluor594 (Jackson ImmunoResearch) for 2 hr at room temperature. DAPI was included in the ProLong “Diamond” mounting media (Life Technologies) to label cell nuclei. All specimens were viewed on a Zeiss LSM710 microscope located within the Central Microscopy Research Facility at the University of Iowa (Iowa City).

Plaque assay

16HBE14o- cells were cultured as described above. 16HBE14o- cell lysates and supernatants were collected at given time points by scrapping the monolayer with the plunger of a 1 ml syringe, pooled with the supernatant and flash frozen in liquid nitrogen. RSV viral titers were assessed by plaque assay as previously described (23).

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using Prism software (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA). Statistical significance was determined by a oneway ANOVA, with a Holm-Sidak's multiple comparisons post-test; or a nonparametric t-test, with a Mann-Whitney post-test. A value of p<0.05 was considered significant. Asterisks indicating significance were defined as follows: *, p<0.05; **, p<0.01; ***, p<0.001.

Results

NTHi exposure inhibits a subsequent RSV infection

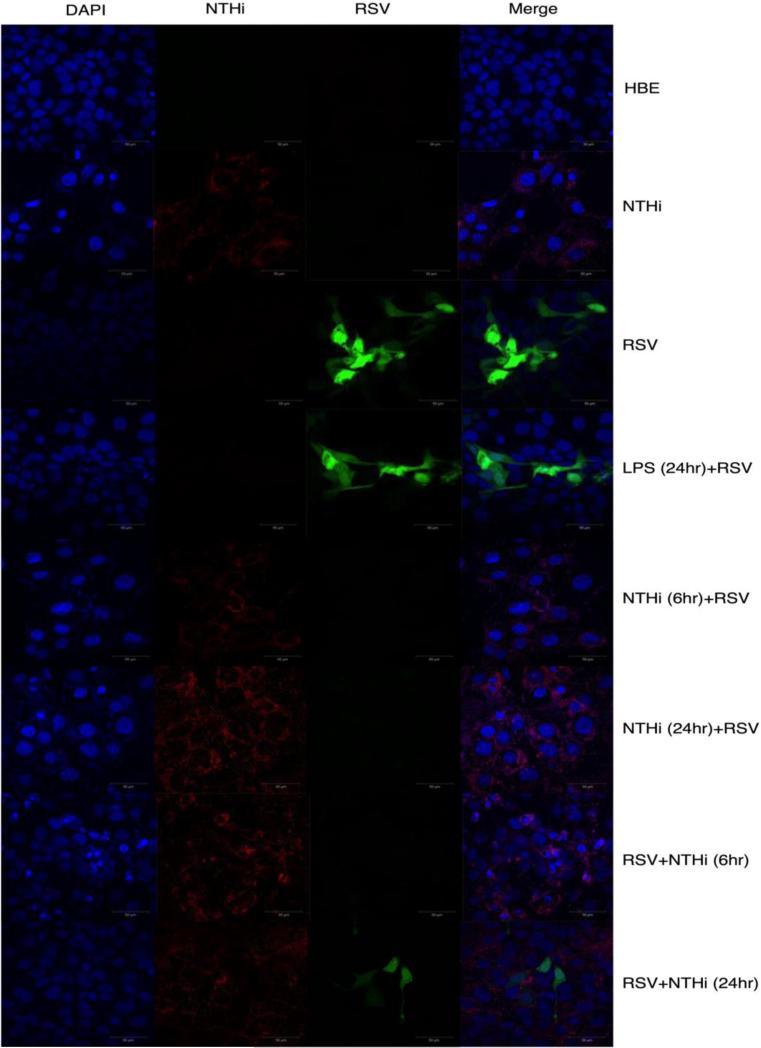

NTHi is a common commensal organism found in the human upper respiratory tract (4-6). It is currently unclear how commensal bacteria in the respiratory tract may impact the host response to a viral infection. Here we sought to determine the impact of initial exposure with NTHi on a subsequent RSV infection using 16HBE14o- cells. 16HBE14o- cells were co-cultured with NTHi at an initial bacterium:cell ratio of 1:1. At either 6 or 24 hr following initial exposure to bacteria, the cultures were infected with RSV. At 48 hr post RSV infection, cells were collected for RNA isolation and RSV N gene expression was quantified by RT-PCR. RSV N gene expression was significantly (p<0.05) reduced in 16HBE14o- cells pre-cultured with NTHi for either 6 or 24 hr as compared to 16HBE14o- cells infected with RSV alone (Figure 1A). A similar reduction in RSV N gene expression was also observed at 72 hr post RSV infection (data not shown). These data indicate that prior NTHi exposure alters the replication of a subsequent RSV infection. We next asked if viral gene expression would be similarly inhibited if NTHi exposure occurred following RSV infection. To address this question, we infected 16HBE14o- cells with RSV followed by exposure to NTHi either 6 or 24 hr later. We observed no difference in the RSV N gene expression as compared to an RSV alone control (Figure 1B). These data demonstrate that gene expression was unaltered when 16HBE14o- cells were cultured with NTHi after RSV infection. We observed similar results when virus titers were assessed by plaque assay (Figure 1C). In addition, pre-treatment of 16HBE14o- cells with LPS 24hr prior to RSV infection did not alter the amount of RSV that could be recovered at 48 hr post-infection. We also carried out cultures under the same conditions as described above for confocal imaging utilizing a recombinant RSV expressing GFP (12). RSV replication was greatly reduced when 16HBE14o- cells were cultured with NTHi prior to an RSV infection, but not when cells were infected with RSV prior to culture with NTHi (Figure 2). Our results demonstrate that culturing 16HBE14o- cells with NTHi prior to RSV infection significantly inhibits viral gene expression and replication.

Fig 1. Reduced RSV gene expression and replication in 16HBE14o- cells exposed to NTHi.

16HBE14o- cells were co-cultured with NTHi at a bacterium:cell ratio of 1:1 for 6 and 24 hours both prior to and after RSV infection at an MOI 1. Cellular RNA was isolated at 48 hours following RSV infection. RSV N gene copy numbers were determined by RT-PCR either (A) before RSV infection or (B) after RSV infection. 16HBE14o- cells were co-cultured with NTHi at a bacterium:cell ratio of 1:1 for 6 and 24 hours prior to and after RSV-GFP infection. Separate cultures were used to assess RSV titers by (C) plaque assay. Statistics were performed using a one-way Anova, with a Holm-Sidak's multiple comparisons post-test.

Fig 2. Reduced RSV-GFP expression in 16HBE14o- cells exposed to NTHi.

Cells were isolated at 48 hours following RSV infection for confocal imaging. DAPI was used to stain the nuclei of the 16HBE14o- cells; secondary mAb goat anti-mouse IgG AlexaFluor594 to stain NTHi and green represents the RSV-GFP reporter virus. Data are representative of two individual experiments performed in duplicate. Statistics were performed using a one-way Anova, with a Holm-Sidak's multiple comparisons post-test.

Altering either the initial NTHi dose or the RSV challenge dose does not impact NTHi protection from an RSV infection

We observed a significant reduction in the RSV N gene expression when NTHi was administered to the 16HBE14o- cells prior to RSV infection. We next sought to determine if the number of initial bacteria would impact protection against a subsequent RSV infection. 16HBE14o- cells were co-cultured with serial 10-fold dilutions of NTHi for 24 hours prior to RSV infection. RSV N gene expression was significantly (p<0.001) reduced at all NTHi dilutions (Figure 3A). Since all RSV infections were carried out at an MOI of 1, we next asked if NTHi exposure could similarly protect against a higher RSV inoculum. 16HBE14o- cells were co-cultured with NTHi for 24 hr prior to infection with RSV at an MOI of 10. Despite the higher RSV inoculum, 16HBE14o- cells exposed to NTHi were still able to significantly (p<0.05) inhibit the expression of the RSV N gene (Figure 3B). Our results demonstrate that 16HBE14o- cells co-cultured with NTHi prior to RSV infection results in a significant reduction in viral gene expression independent of either the starting number of bacteria or the amount of virus in the inoculum.

Fig 3. NTHi-mediated inhibition of RSV is independent of the initial bacteria load or RSV infectious dose.

16HBE14o- cells were co-cultured with varying initial NTHi bacterium:cell ratios for 24 hours prior to RSV infection. Cellular RNA was isolated at 48 hours following RSV infection. (A) RSV N gene copy numbers were determined by RT-PCR. (B) RSV N gene copy numbers were also determined by RT-PCR after an MOI of 10 was used to infect 16HBE14o- cells cultured with NTHi at a bacterium:cell ratio of 1:1. Data are representative of two individual experiments performed in duplicate. Statistics on (A) were performed using a one-way Anova, with a Holm-Sidak's multiple comparisons post-test and (B) were performed using an unpaired t-test, with a Mann-Whitney post-test.

Live NTHi is required to mediate protection against RSV

We next asked if NTHi-mediated protection against RSV infection in 16HBE14o- cells requires live replication-competent bacteria. 16HBE14o- cells were co-cultured with either live NTHi or heat-killed NTHi (HK-NTHi) 24 hours prior to RSV infection. As expected, 16HBE14o- cells co-cultured with live NTHi prior to RSV infection exhibited reduced RSV N gene expression. In contrast, 16HBE14o- cells co-cultured with HK-NTHi failed to protect against a subsequent RSV challenge (Figure 4A). This result was also confirmed via microscopy. 16HBE14o- cells were co-cultured with live NTHi and subsequently infected with RSV-GFP. As expected NTHi exposure resulted in a significant reduction in the number of GFP+ cells infected with RSV. In contrast, exposure to HK-NTHi followed by a subsequent RSV-GFP infection, resulted in an increased frequency of RSV-infected cells, (Figure 4B) similar to an RSV only control (data not shown). These data indicate that live bacteria are required to protect 16HBE14o- cells against a subsequent RSV infection.

Fig 4. Inhibition of RSV by NTHi requires live bacteria.

16HBE14o- cells were co-cultured with either live or heat-killed NTHi at a 1:1 ratio for 24 hours. Cells were infected with RSV at an MOI of either 1 or 10. Cells were collected for (A) copy number of RSV N gene or (B) confocal imaging after 72 hours. Data are representative of two individual experiments performed in duplicate. Statistics were performed using a one-way Anova, with a Holm-Sidak's multiple comparisons post-test.

We next determined whether NTHi was directly interacting with RSV to cause the inhibition of viral infection or if NTHi was inhibiting receptors on the 16HBE14o- cells that the virus would normally use to enter a cell. We co-incubated RSV with live NTHi or HK-NTHi on ice for 30 minutes prior to infecting the cells. Live NTHi co-incubated with RSV showed a significant reduction (p<0.05) in N gene expression while HK-NTHi co-incubated with RSV showed similar levels to the RSV control (Figure 5A). We observed similar results when viral titers were assessed by plaque assay (Figure 5B). While these data suggest that NTHi may directly interact with RSV prior to entry, the reduction we observe following co-incubation is not to the same magnitude as when 16HBE14o- cells are pre-cultured with NTHi prior to RSV infection.

Fig 5. Inhibition of RSV by NTHi requires live bacteria.

Either live or heat-killed NTHi, at a 1:1 ratio, was co-incubated with RSV with an MOI of 1, on ice for 30 mins prior to infection of 16HBE14o- cells. Cell lysates and supernatants were collected for (A) copy number of RSV N gene or (B) plaque assay after 48 hrs. Data are representative of two individual experiments performed in duplicate. Statistics were performed using a one-way Anova, with a Holm-Sidak's multiple comparisons post-test.

Cellular entry facilitates protection mediated by NTHi against an RSV infection

We have shown that 16HBE14o- cells exposed to live but not heat-killed NTHi are protected against a subsequent RSV infection. NTHi invades host epithelial cells via LOS-bound phosphorylcholine (24) by engaging the platelet activating factor receptor (16). Therefore, we next asked if NTHi entry into 16HBE14o- cells was required to mediate protection against an RSV infection. 16HBE14o- cells were co-cultured with NTHi; NTHi 2019ΔlicD, an NTHi 2019 mutant lacking phosphorylcholine on the surface; (24) or Neisseria cinerea (N. cinerea) (25) for 24 hours prior to RSV infection. N. cinerea is a non-pathogenic organism, known to colonize the human nasopharynx (17). RSV N gene expression was significantly (p<0.001) reduced within 16HBE14o- cells exposed to either NTHi or N. cinerea as compared to NTHi 2019ΔlicD (Figure 6). These data demonstrate that NTHi entry into airway epithelial cells may be necessary for the protection of 16HBE14o- cells against a subsequent RSV infection. Our results also indicate that in addition to NTHi, other commensal bacteria such as N. cinerea that are capable of infecting epithelial cells can also mediate protection against a subsequent RSV infection.

Fig 6. Inhibition of RSV infection by NTHi requires bacteria capable of invading epithelial cells.

16HBE14o- cells were co-cultured with NTHi, NTHi 2019ΔlicD, or Neisseria cinerea at bacterium:cell ratio of 1:1 for 24 hours. Cellular RNA was isolated at 48 hours following RSV infection. Data are representative of two individual experiments performed in duplicate. Statistics were performed using a one-way Anova, with a Holm-Sidak's multiple comparisons post-test.

Protection is virus specific

We next asked if bacteria-mediated protection of epithelial cells was specific to RSV or if this would also apply to other respiratory viruses. To address this question, 16HBE14o- cells were co-cultured with NTHi 2019 prior to infection with influenza A virus (IAV). In contrast to RSV, NTHi 2019 exposure did not significantly impact IAV NP gene expression (Figure 7). These data suggest that protection of epithelial cells by bacteria exposure is specific to RSV.

Fig 7. NTHi protection is virus specific.

16HBE14o- cells were co-cultured with NTHi at a bacterium:cell ratio of 1:1 for 24 hours. Cellular RNA was isolated at 48 hours following IAV infection at an MOI of either 0.1 or 1.0. IAV NP gene copy numbers were determined by RT-PCR. Data are representative of two individual experiments performed in duplicate. Statistics were performed using a one-way Anova, with a Holm-Sidak's multiple comparisons post-test.

Discussion

NTHi is a common commensal bacteria found in both the upper and lower respiratory tract (4-6). RSV infections are often associated with the enhanced colonization of NTHi on host cells. RSV infection of either A549 (8) or HEp-2 cells (26) has been shown to increase NTHi attachment to epithelial cells. NTHi and Streptococcus pneumoniae are isolated more frequently from patients with respiratory infections as compared to those who do not have respiratory infections (27, 28). Disease models, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) have been studied extensively examining the interaction of respiratory infections and secondary bacterial infections. NTHi is believed to induce increased inflammation in the airways in patients with COPD (29). Further studies in animals have shown that mice are more susceptible to Streptococcus pneumoniae following an RSV infection (30). However, none of these studies have examined how NTHi can impact a secondary viral infection.

In this study we show that 16HBE14o- cells cultured with NTHi prior to RSV challenge exhibit a significant reduction in viral replication. In contrast, 16HBE14o- cells infected with RSV prior to being co-cultured with NTHi exhibited similar viral replication as 16HBE14o- cells infected with RSV alone. Gulraiz et al previously reported an increase in RSV replication in BEAS-2B cells co-cultured with heat-inactivated NTHi prior to an RSV infection with an MOI of 10 (31). In agreement with the observations of Gulraiz et al, we did observe a modest increase in RSV gene expression when using an MOI of 10. However, when using an MOI of 1, we did not observe an increase in RSV gene expression following co-culture with heat-inactivated NTHi as compared to the RSV control.

Phosphorylcholine is known to be important for the colonization and persistence of bacterial adherence to the host cell (16, 24). Work by Hong et al has demonstrated that NTHi 2019ΔlicD, an NTHi mutant lacking phosphorylcholine, fails to establish stable biofilm communities in vivo (24). We show that 16HBE14o- cells co-cultured with NTHi 2019ΔlicD exhibit decreased protection against RSV infection as compared to wild-type NTHi. Thus, our data indicate that NTHi must enter the epithelial cell in order to provide optimal protection against a subsequent RSV infection.

It is interesting that prior infection with N. cinerea, another commensal bacterial resident of the human nasopharynx, can also protect 16HBE14o- cells against RSV infection. This suggests that components of the human microbiome might influence disease susceptibility or severity. The mechanisms of survival of this species on the human upper airway have not been well-studied and it is unknown if cell entry is a component of the process. Genomic sequencing of N. cinerea strain 14685 (NCBI Ref Seq: NZ_ACDY00000000.2) indicates that N. cinerea lacks the phosphorylcholine synthesis and transfer locus for decoration of the LOS with ChoP and also lacks the genes found in N. meningitidis and in N. gonorrhoeae which allows ChoP decoration of the respective pili of these organisms (32). This observation raises the possibility that specific members of the nasopharyngeal microbiome might play an important role in determining the susceptibility of the host to viruses such as RSV. NTHi colonization of the infant nasopharynx has been studied temporally, and by the end of the first year of life only 20% of children have been colonized by this organism (33, 34). Most children experience RSV infections during the first two years of life, it is interesting to speculate if children who are spared RSV infection during this period have been colonized by NTHi or N. cinerea at a young age.

We have shown that NTHi protects 16HBE14o- cells from a subsequent RSV infection. However, when 16HBE14o- cells are co-cultured with NTHi, the bacteria fail to provide protection against a subsequent IAV infection. Similar to our findings, Ouyang et al showed that pre-treatment of MDCK cells with live S. pneumoniae strains also did not alter the replication of IAV (35). Thus, our results suggest that NTHi-mediated protection of 16HBE14o- cells may be specific to RSV.

The mechanism by which NTHi inhibits a subsequent RSV infection is currently unclear. It is known that NTHi can induce a host inflammatory response via TLR4 stimulation (36). However, our data demonstrating that LPS stimulation of the 16HBE14o- cells prior to RSV exposure did not inhibit RSV replication suggests that that primary mechanism of NTHi-mediated inhibition of RSV replication is not due to TLR4 stimulation alone. We observed that co-incubation of NTHi and RSV prior to infection did result in a decrease in RSV replication that was not as substantial as when NTHi exposure preceded the RSV infection. This result suggests that NTHi may either directly bind to RSV preventing its ability to enter host cells or that NTHi may inhibit the ability of RSV to bind to host cells via its receptor, which has been putatively identified as nucleolin (37).

In summary, we have shown that co-culture of 16HBE14o- cells with NTHi provides protection against a subsequent RSV infection. NTHi-mediated protection required co-culture with live bacteria. In addition, we also demonstrate that optimal protection requires bacterial entry into the host epithelial cells. Taken together, our data indicate that NTHi colonization may provide enhanced protection against an RSV infection. Thus early NTHi colonization of respiratory tract may play a critical role in providing protection against a subsequent viral infection.

Highlights.

Exposure of human epithelial cells to non-typeable Haemophilus influenzae (NTHi) inhibits a subsequent infection with respiratory syncytial virus

NTHi-mediated protection requires live bacteria capable of invading the epithelia cell

NTHi-mediated inhibition was specific to RSV and failed to inhibit the replication of a subsequent influenza virus infection

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge use of the University of Iowa Central Microscopy Research Facility, a core resource supported by the Vice President for Research & Economic Development, the Holden Comprehensive Cancer Center and the Carver College of Medicine [Zeiss LSM710 confocal grant 1 S10 RR025439-01].

Funding

This work was supported by National Institute of Health [grant number AI024616] [to MAA].

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Potential conflicts of interest

All authors: No conflicts.

References

- 1.Bosch AA, Biesbroek G, Trzcinski K, Sanders EA, Bogaert D. Viral and bacterial interactions in the upper respiratory tract. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9:e1003057. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McCullers JA. The co-pathogenesis of influenza viruses with bacteria in the lung. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2014;12:252–262. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Metzger DW, Sun K. Immune dysfunction and bacterial coinfections following influenza. J Immunol. 2013;191:2047–2052. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1301152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harabuchi Y, Faden H, Yamanaka N, Duffy L, Wolf J, Krystofik D. Nasopharyngeal colonization with nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae and recurrent otitis media. Tonawanda/Williamsville Pediatrics. J Infect Dis. 1994;170:862–866. doi: 10.1093/infdis/170.4.862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ingvarsson L, Lundgren K, Olofsson B, Wall S. Epidemiology of acute otitis media in children. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl. 1982;388:1–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murphy TF, Apicella MA. Nontypable Haemophilus influenzae: a review of clinical aspects, surface antigens, and the human immune response to infection. Rev Infect Dis. 1987;9:1–15. doi: 10.1093/clinids/9.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Avadhanula V, Rodriguez CA, Devincenzo JP, Wang Y, Webby RJ, Ulett GC, Adderson EE. Respiratory viruses augment the adhesion of bacterial pathogens to respiratory epithelium in a viral species- and cell type-dependent manner. J Virol. 2006;80:1629–1636. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.4.1629-1636.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jiang Z, Nagata N, Molina E, Bakaletz LO, Hawkins H, Patel JA. Fimbria-mediated enhanced attachment of nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae to respiratory syncytial virus-infected respiratory epithelial cells. Infect Immun. 1999;67:187–192. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.1.187-192.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pang B, Winn D, Johnson R, Hong W, West-Barnette S, Kock N, Swords WE. Lipooligosaccharides containing phosphorylcholine delay pulmonary clearance of nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae. Infect Immun. 2008;76:2037–2043. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01716-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chonmaitree T, Owen MJ, Patel JA, Hedgpeth D, Horlick D, Howie VM. Effect of viral respiratory tract infection on outcome of acute otitis media. J Pediatr. 1992;120:856–862. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)81950-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hietala J, Uhari M, Tuokko H, Leinonen M. Mixed bacterial and viral infections are common in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1989;8:683–686. doi: 10.1097/00006454-198910000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hallak LK, Spillmann D, Collins PL, Peeples ME. Glycosaminoglycan sulfation requirements for respiratory syncytial virus infection. J Virol. 2000;74:10508–10513. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.22.10508-10513.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Legge KL, Braciale TJ. Lymph node dendritic cells control CD8+ T cell responses through regulated FasL expression. Immunity. 2005;23:649–659. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Campagnari AA, Gupta MR, Dudas KC, Murphy TF, Apicella MA. Antigenic diversity of lipooligosaccharides of nontypable Haemophilus influenzae. Infect Immun. 1987;55:882–887. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.4.882-887.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Poole J, Foster E, Chaloner K, Hunt J, Jennings MP, Bair T, Knudtson K, Christensen E, Munson RS, Jr., Winokur PL, Apicella MA. Analysis of nontypeable haemophilus influenzae phase-variable genes during experimental human nasopharyngeal colonization. J Infect Dis. 2013;208:720–727. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Swords WE, Buscher BA, Ver Steeg Ii K, Preston A, Nichols WA, Weiser JN, Gibson BW, Apicella MA. Non-typeable Haemophilus influenzae adhere to and invade human bronchial epithelial cells via an interaction of lipooligosaccharide with the PAF receptor. Mol Microbiol. 2000;37:13–27. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01952.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Muzzi A, Mora M, Pizza M, Rappuoli R, Donati C. Conservation of meningococcal antigens in the genus Neisseria. MBio. 2013;4:e00163–00113. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00163-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gruenert DC, Basbaum CB, Welsh MJ, Li M, Finkbeiner WE, Nadel JA. Characterization of human tracheal epithelial cells transformed by an origin-defective simian virus 40. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988;85:5951–5955. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.16.5951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hu A, Colella M, Tam JS, Rappaport R, Cheng SM. Simultaneous detection, subgrouping, and quantitation of respiratory syncytial virus A and B by real-time PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:149–154. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.1.149-154.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Regan JF, Liang Y, Parslow TG. Defective assembly of influenza A virus due to a mutation in the polymerase subunit PA. J Virol. 2006;80:252–261. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.1.252-261.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spinola SM, Kwaik YA, Lesse AJ, Campagnari AA, Apicella MA. Cloning and expression in Escherichia coli of a Haemophilus influenzae type b lipooligosaccharide synthesis gene(s) that encodes a 2-keto-3-deoxyoctulosonic acid epitope. Infect Immun. 1990;58:1558–1564. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.6.1558-1564.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McLaughlin R, Spinola SM, Apicella MA. Generation of lipooligosaccharide mutants of Haemophilus influenzae type b. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:6455–6459. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.20.6455-6459.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Olson MR, Hartwig SM, Varga SM. The number of respiratory syncytial virus (RSV)-specific memory CD8 T cells in the lung is critical for their ability to inhibit RSV vaccine-enhanced pulmonary eosinophilia. J Immunol. 2008;181:7958–7968. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.11.7958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hong W, Pang B, West-Barnette S, Swords WE. Phosphorylcholine expression by nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae correlates with maturation of biofilm communities in vitro and in vivo. J Bacteriol. 2007;189:8300–8307. doi: 10.1128/JB.00532-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Knapp JS, Totten PA, Mulks MH, Minshew BH. Characterization of Neisseria cinerea, a nonpathogenic species isolated on Martin-Lewis medium selective for pathogenic Neisseria spp. J Clin Microbiol. 1984;19:63–67. doi: 10.1128/jcm.19.1.63-67.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Raza MW, Ogilvie MM, Blackwell CC, Stewart J, Elton RA, Weir DM. Effect of respiratory syncytial virus infection on binding of Neisseria meningitidis and Haemophilus influenzae type b to a human epithelial cell line (HEp-2). Epidemiol Infect. 1993;110:339–347. doi: 10.1017/s095026880006828x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smith CB, Golden C, Klauber MR, Kanner R, Renzetti A. Interactions between viruses and bacteria in patients with chronic bronchitis. J Infect Dis. 1976;134:552–561. doi: 10.1093/infdis/134.6.552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.White AJ, Gompertz S, Stockley RA. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease . 6: The aetiology of exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax. 2003;58:73–80. doi: 10.1136/thorax.58.1.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chin CL, Manzel LJ, Lehman EE, Humlicek AL, Shi L, Starner TD, Denning GM, Murphy TF, Sethi S, Look DC. Haemophilus influenzae from patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbation induce more inflammation than colonizers. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;172:85–91. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200412-1687OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stark JM, Stark MA, Colasurdo GN, LeVine AM. Decreased bacterial clearance from the lungs of mice following primary respiratory syncytial virus infection. J Med Virol. 2006;78:829–838. doi: 10.1002/jmv.20631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gulraiz F, Bellinghausen C, Bruggeman CA, Stassen FR. Haemophilus influenzae increases the susceptibility and inflammatory response of airway epithelial cells to viral infections. FASEB J. 2015;29:849–858. doi: 10.1096/fj.14-254359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Faden H, Duffy L, Wasielewski R, Wolf J, Krystofik D, Tung Y. Relationship between nasopharyngeal colonization and the development of otitis media in children. Tonawanda/Williamsville Pediatrics. J Infect Dis. 1997;175:1440–1445. doi: 10.1086/516477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Aniansson G, Alm B, Andersson B, Larsson P, Nylen O, Peterson H, Rigner P, Svanborg M, Svanborg C. Nasopharyngeal colonization during the first year of life. J Infect Dis 165 Suppl. 1992;1:S38–42. doi: 10.1093/infdis/165-supplement_1-s38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jen FE, Warren MJ, Schulz BL, Power PM, Swords WE, Weiser JN, Apicella MA, Edwards JL, Jennings MP. Dual pili post-translational modifications synergize to mediate meningococcal adherence to platelet activating factor receptor on human airway cells. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9:e1003377. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ouyang K, Woodiga SA, Dwivedi V, Buckwalter CM, Singh AK, Binjawadagi B, Hiremath J, Manickam C, Schleappi R, Khatri M, Wu J, King SJ, Renukaradhya GJ. Pretreatment of epithelial cells with live Streptococcus pneumoniae has no detectable effect on influenza A virus replication in vitro. PLoS One. 2014;9:e90066. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0090066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lazou Ahren I, Bjartell A, Egesten A, Riesbeck K. Lipopolysaccharide-binding protein increases toll-like receptor 4-dependent activation by nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae. J Infect Dis. 2001;184:926–930. doi: 10.1086/323398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tayyari F, Marchant D, Moraes TJ, Duan W, Mastrangelo P, Hegele RG. Identification of nucleolin as a cellular receptor for human respiratory syncytial virus. Nat Med. 2011;17:1132–1135. doi: 10.1038/nm.2444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]