Abstract

Our ability to understand speech requires neural tuning with high frequency resolution, but the peripheral mechanisms underlying sharp tuning in humans remain unclear. Sharp tuning in genetically modified mice has been attributed to decreases in spread of excitation of tectorial membrane traveling waves. Here we show that the spread of excitation of tectorial membrane waves is similar in humans and mice, although the mechanical excitation spans fewer frequencies in humans—suggesting a possible mechanism for sharper tuning.

Main Text

The mammalian cochlea separates sounds by their frequency content, and this separation is critical to our ability to perceive speech, especially in acoustically challenging environments. While the cross-sectional structure of the mammalian organ of Corti is highly conserved across species, several studies have suggested that frequency selectivity has higher resolution (i.e., is more sharply tuned) in humans than in other mammals (1, 2, 3). Although sharper neural tuning in humans has been attributed to peripheral mechanisms (4, 5, 6), the origin of the difference in neural tuning remains unclear.

Recent in vitro and in vivo studies have revealed that the tectorial membrane (TM) contributes to spread of mechanical excitation via longitudinally propagating traveling waves (7, 8, 9, 10). In particular, Tectb−/− mutant mice, which lack the β-tectorin glycoproteins, exhibit significantly sharper tuning (11). Furthermore, the spatial decay constant of TM waves in Tectb−/− mice is smaller by a factor of two (8), suggesting that differences in TM waves may underlie differences in neural frequency tuning observed in Tectb−/− mice. This result raises the possibility that neural frequency tuning in humans (4) may be sharper due in part to differences in TM longitudinal coupling and wave phenomena. Here we test this intriguing possibility by making, to our knowledge, the first direct measurements of fresh human TMs.

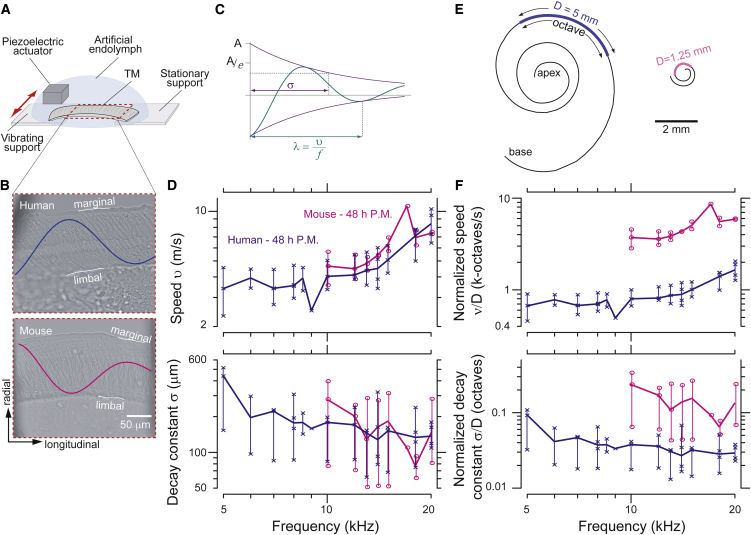

Temporal bones were harvested from human cadavers and mice, and midbasal TM segments were extracted and mounted in a wave chamber (Fig. 1 a) within 48 h postmortem. TM segments were stimulated mechanically to launch traveling waves (Movies S1 and S2 in the Supporting Material). Motion waveforms were captured using stroboscopic illumination with a custom computer vision technique (Materials and Methods). Measurements were performed in TM samples from mice for basal frequencies (>10 kHz) and from humans for basal frequencies (>5 kHz) subject to equipment limitations (<20 kHz), and representative displacement waveforms are superimposed on optical images of human and mouse TM segments in Fig. 1 b. TM wave decay constant, wavelength, and speed (Fig. 1 c) were computed from the magnitude and phase of TM radial displacements for both species (Fig. 1 d).

Figure 1.

(A) Wave chamber used to deliver sinusoidal mechanical stimulation in the radial direction to launch traveling waves along excised TM segments. (B) Light microscope images of human and mouse TMs in a wave chamber. Waveforms superimposed on the image show radial motion exaggerated to help visualize the motion in response to 8 kHz (human) and 15 kHz (mouse) stimuli. Marginal and limbal boundaries of the TM are indicated. (C) TM wave properties analyzed from the motion waveforms include wavelength (λ), speed (v), and wave decay constant (σ). (D) Frequency dependence of traveling wave speeds (top) and TM wave decay constants (bottom) for human and mouse basal segments. (E) Schematic drawings of cochlear spirals in human and mouse. The spatial extents of octave intervals (as calculated from the cochlear maps of Greenwood (12) and Müller et al. (13)) are indicated with colored lines along the spiral. (F) TM wave speeds and decay constants divided by D, the distance over which frequency changes by an octave for each species. Symbols indicate all data points. (Thick horizontal lines) Medians; (vertical lines) range of data measured at a single frequency across preparations (human, n = 4; mouse, n = 4).

Our measured wave decay constants (σ) and speeds (v) are similar in humans and mice. The speed of TM traveling waves in human samples increases by roughly a factor of two from 5 to 20 kHz. Mouse TM speeds also increase with frequency, nearly overlapping human speeds for the physiologically relevant range of frequencies (10–20 kHz). The median decay constants of human TMs range from 150 and 450 μm from 5 to 20 kHz and are relatively constant with frequency. Similarly, the range of median σ-values for mouse TMs is 80–300 μm from 10 to 20 kHz. We see significant overlap of the median and ranges between the two species over their common frequency range of basal hearing (10–20 kHz; Fig. 1 d).

Wave properties of viscoelastic solids depend on the solid’s material properties, including density ρ, shear storage modulus G′, and shear viscosity η (7). To account for boundary conditions in the wave chamber, we used a lumped parameter model consisting of a distributed series of masses coupled by viscous and elastic elements (7). We computed the material properties for each TM wave measurement and found no significant difference between human (G′ = 14.5 ± 8.2 kPa and η = 0.16 ± 0.1 Pa·s) and mouse (G′ = 16.3 ± 6.6 kPa and η = 0.21 ± 0.1 Pa·s) material properties.

The spatial decay constants for both mice and humans are on the order of 150 μm at 20 kHz (Fig. 1 e). This distance is a measure of longitudinal spread of excitation and correlates with spectral spread of excitation (7). Each cochlear location is mechanically excited not only by its best frequency, but also by frequencies that best excite adjacent regions with different best frequencies. For mice, the spatial spread of 150 μm corresponds to a frequency spread of 1.6 kHz and therefore a quality of tuning Q10dB of approximately 10 at 20 kHz (8). In TectB knockout mice, the decay constant of TM waves is approximately halved, leading to a Q10dB value that is doubled (8). This sharpened tuning, predicted from the mechanical spread of excitation measured in an isolated TM, correlates well with sharpened tuning in auditory nerve measurements of these mutant mice (11).

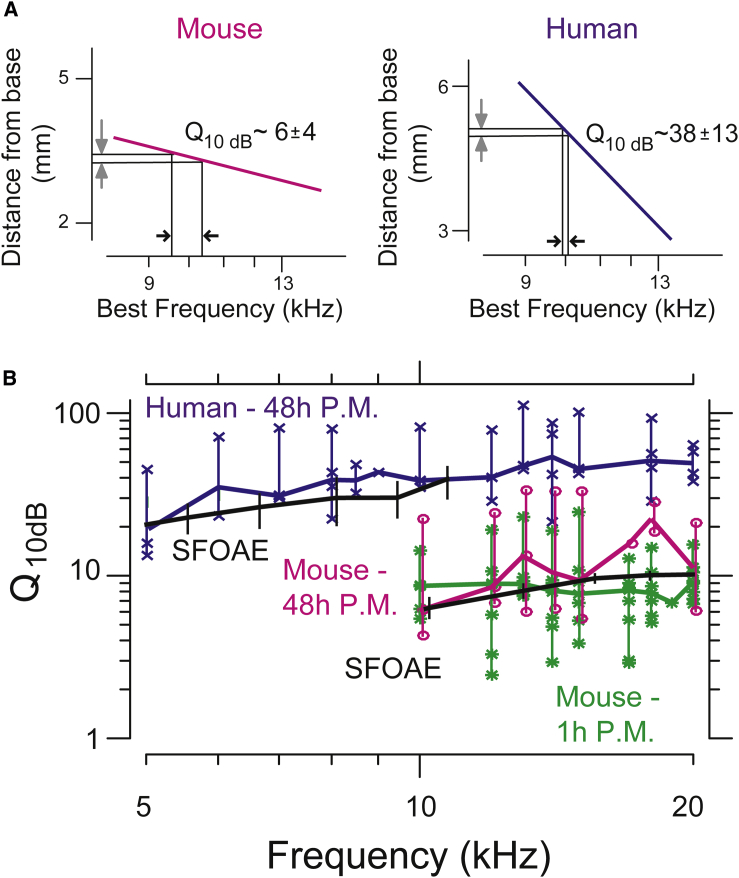

While TM waves spread excitations over similar distances in mice and humans, these distances span significantly different ranges of frequencies (Fig. 1 e). For the mouse, the 150-μm decay constant represents a frequency range of >1.4 kHz, while the same distance corresponds to <300 Hz in humans (Fig. 1 f). This difference has important implications for our ability to separate sounds by their frequency content—suggesting that the spread of excitation via TM traveling waves is broader in mice than in humans. It is therefore important to characterize spread of excitation in terms of the range of frequencies over which the excitation is spread. Because the relation between cochlear location and best frequency is approximately logarithmic (Fig. 2 a) (12, 13), constant distances map to logarithmic frequency ranges, such as octaves. We therefore converted TM wave decay constants from distances (in meters) to frequency ranges (in octaves) by dividing σ by the distance D over which frequency changes by one octave. The resulting normalized decay constants for mice and humans differ significantly (Fig. 2 a), with those for humans being ∼4 times smaller than those for mice. Thus, normalizing the wave decay constant to reflect the physiologically important range of frequencies reveals striking differences between humans and mice.

Figure 2.

(A) Place-frequency maps for mouse (left) and human (right) showing how TM wave decay constants relate to frequency bandwidth of tuning. (B) Estimates of Q10dB for human (blue, n = 4) and mouse (magenta, n = 4) from TM waves compared to published stimulus frequency otoacoustic emission data (SFOAE, black lines; mouse (14), human (15)). Also plotted in green are estimates of Q10dB from mouse TM wave measurements performed within 1 h postmortem. Symbols indicate all data points. (Thick horizontal lines) Medians; (vertical lines) range of data measured at a single frequency for all samples (human, n = 4; mouse 48 h postmortem, n = 4; mouse 1 h postmortem, n = 10).

The ratio of the center frequency to the range of frequencies coupled by the TM wave decay constant defines a quality of tuning (Q10dB). Fig. 2 b shows significantly larger quality of tuning in humans compared to mice (larger by a factor of five), consistent with a smaller spatial extent of TM waves relative to the cochlear map. These Q10dB predictions based on TM wave decay constants are comparable to cochlear tuning predictions based on otoacoustic emissions (4). Previous studies have shown these emission-based estimates of tuning to be comparable to neural estimates for a range of mammalian species (4, 5, 6). For mice, the quality of tuning estimated from TM wave decay constants closely matches predictions of Q10dB from otoacoustic emissions (14). For humans, the Q10dB estimates are comparable to emissions-based estimates (15) from 5 to 10 kHz. Taken together, these findings suggest that the spatial extent of TM waves strongly correlates with cochlear tuning in humans, mice, and likely other mammals. This correlation suggests that spread of excitation through TM traveling waves contributes to differences in tuning in humans and other mammals.

Author Contributions

S.F., R.G., and D.M.F. designed the research; S.F. and H.H.N. conducted the work on human temporal bones; S.F. and J.B.S. conducted the experiments on mice and analyzed the data; and S.F., R.G., and D.M.F. wrote the article.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Diane Jones for dissecting the human temporal bones from donors. We also thank Christopher A. Shera, John J. Guinan Jr., and Scott L. Page for their helpful comments and suggestions on this work.

This research was supported by National Institutes of Health grant No. R01-DC00238. S.F. and J.B.S. were supported in part by a training grant from the National Institutes of Health to the Speech and Hearing Biosciences and Technology Program in the Harvard-MIT Program in Health Sciences and Technology.

Editor: James Keener.

Footnotes

Supporting Materials and Methods, two figures, and two movies are available at http://www.biophysj.org/biophysj/supplemental/S0006-3495(16)30618-X.

Supporting Material

Motion of a representative mouse TM segment in response to 20 kHz stimulation. Motion magnification algorithms (2) were applied to help with visualization of TM motions in the wave chamber.

Motion of a representative human TM segment in response to 20 kHz stimulation. Motion magnification algorithms (2) were applied to help with visualization of TM motions in the wave chamber.

References

- 1.Bitterman Y., Mukamel R., Nelken I. Ultra-fine frequency tuning revealed in single neurons of human auditory cortex. Nature. 2008;451:197–201. doi: 10.1038/nature06476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harrison R.V., Aran J.-M., Erre J.-P. AP tuning curves from normal and pathological human and guinea pig cochleas. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1981;69:1374–1385. doi: 10.1121/1.385819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sinnott J.M., Beecher M.D., Stebbins W.C. Speech sound discrimination by monkeys and humans. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1976;60:687–695. doi: 10.1121/1.381140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shera C.A., Guinan J.J., Jr., Oxenham A.J. Revised estimates of human cochlear tuning from otoacoustic and behavioral measurements. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:3318–3323. doi: 10.1073/pnas.032675099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shera C., Guinan J., Jr., Oxenham A. Otoacoustic estimation of cochlear tuning: validation in the chinchilla. J. Assoc. Res. Otol. 2010;11:343–365. doi: 10.1007/s10162-010-0217-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Joris P.X., Bergevin C., Shera C.A. Frequency selectivity in Old-World monkeys corroborates sharp cochlear tuning in humans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:17516–17520. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1105867108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ghaffari R., Aranyosi A.J., Freeman D.M. Longitudinally propagating traveling waves of the mammalian tectorial membrane. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:16510–16515. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703665104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ghaffari R., Aranyosi A.J., Freeman D.M. Tectorial membrane travelling waves underlie abnormal hearing in Tectb mutant mice. Nat. Commun. 2010;1:96. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sellon J.B., Farrahi S., Freeman D.M. Longitudinal spread of mechanical excitation through tectorial membrane traveling waves. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2015;112:12968–12973. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1511620112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee H.Y., Raphael P.D., Oghalai J.S. Noninvasive in vivo imaging reveals differences between tectorial membrane and basilar membrane traveling waves in the mouse cochlea. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2015;112:3128–3133. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1500038112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Russell I.J., Legan P.K., Richardson G.P. Sharpened cochlear tuning in a mouse with a genetically modified tectorial membrane. Nat. Neurosci. 2007;10:215–223. doi: 10.1038/nn1828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Greenwood D.D. A cochlear frequency-position function for several species—29 years later. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1990;87:2592–2605. doi: 10.1121/1.399052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Müller M., von Hünerbein K., Smolders J.W. A physiological place-frequency map of the cochlea in the CBA/J mouse. Hear. Res. 2005;202:63–73. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2004.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cheatham M.A., Goodyear R.J., Siegel J.H. Mechanics of Hearing: Protein to Perception. In: Karavitaki K.D., Corey D.P., editors. Proceedings of the 12th International Workshop on the Mechanics of Hearing. American Institute of Physics; Melville, NY: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dreisbach L.E., Siegel J.H., Chen W. Vector decomposition of distortion product otoacoustic emission sources in humans. J. Assoc. Res. Otolaryngol. Abstr. 1998;21:347. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Motion of a representative mouse TM segment in response to 20 kHz stimulation. Motion magnification algorithms (2) were applied to help with visualization of TM motions in the wave chamber.

Motion of a representative human TM segment in response to 20 kHz stimulation. Motion magnification algorithms (2) were applied to help with visualization of TM motions in the wave chamber.