Protein aggregates and damaged organelles are tagged with ubiquitin chains to trigger selective autophagy. To initiate mitophagy, PINK1 phosphorylates ubiquitin to activate Parkin, which builds ubiquitin chains on mitochondrial outer membrane proteins where they act to recruit autophagy receptors. Using genome editing to knock out five autophagy receptors, we find that two previously linked to xenophagy, NDP52 and Optineurin, are the primary receptors for PINK1/Parkin-mediated mitophagy. The ubiquitin kinase PINK1 recruits NDP52 and Optineurin, but not p62, to mitochondria to directly activate mitophagy independent of Parkin. Once recruited to mitochondria, NDP52 and Optineurin recruit ULK1, DFCP1 and WIPI1 to focal spots proximal to mitochondria revealing a function for these autophagy receptors upstream of LC3. This supports a new model that PINK1 generated phospho-ubiquitin serves as the autophagy signal on mitochondria and that Parkin amplifies it. This work also suggests direct and broader roles for ubiquitin phosphorylation in other autophagy pathways.

Selective autophagy clears intracellular pathogens and mediates cellular quality control by engulfing cargo into autophagosomes and delivering it to lysosomes for degradation. Autophagy receptors bind ubiquitinated cargo and LC3-coated phagophores to mediate autophagy1,2. Damaged mitochondria are removed by autophagy following activation of the kinase PINK1 and the E3 ubiquitin ligase Parkin3,4. Upon loss of mitochondrial membrane potential or accumulation of misfolded proteins, PINK1 is stabilized on the outer mitochondrial membrane3, where it phosphorylates ubiquitin at Ser65 to activate Parkin ubiquitin ligase activity5–7. Although the autophagy receptors p62 and Optineurin (OPTN) have been shown to bind ubiquitin chains on damaged mitochondria, their roles, and the roles of the other autophagy receptors in mediating mitophagy is unclear8–11.

Autophagy receptors in mitophagy

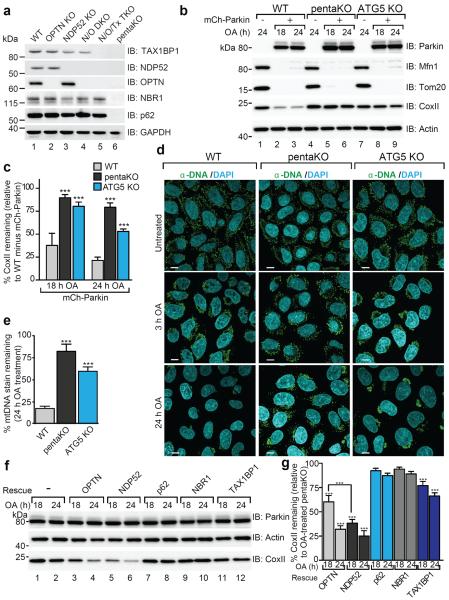

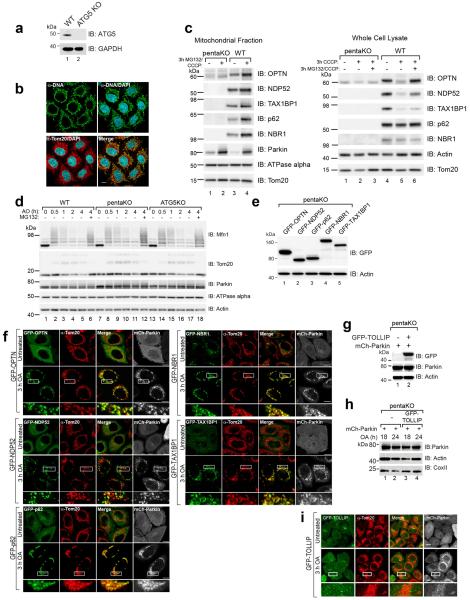

To clarify autophagy receptor function during mitophagy, genome editing was used to knock out five autophagy receptors in HeLa cells (pentaKO), which do not express endogenous Parkin. DNA sequencing (Supplementary Table 1) and immunoblotting of TAX1BP1, NDP52, NBR1, p62 and OPTN (Fig. 1a, lane 6) confirmed their knockout. We analyzed mitophagy in pentaKOs by measuring the degradation of cytochrome C oxidase subunit II (CoxII), a mtDNA encoded inner membrane protein, following mitochondrial damage with oligomycin and antimycin A (OA). After OA treatment, CoxII was degraded in WT cells expressing Parkin, but not in pentaKOs or ATG5 KO HeLa cells, indicating a block in mitophagy (Fig. 1b, c, Supplementary Table 1 and Extended Data Fig. 1a). As a second indicator of mitophagy, mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) nucleoids were quantified by immunofluorescence (Extended Data Fig. 1b). After 24 h OA treatment, WT cells were nearly devoid of mtDNA, whereas pentaKOs and ATG5 KOs retained mtDNA (Fig. 1d, e). Parkin translocated to mitochondria (Extended Data Fig. 1c) and Mfn1 and Tom20 were degraded via the proteasome comparably in WT and pentaKOs (Fig. 1b, Extended Data Fig. 1d). mtDNA nucleoids clump following OA treatment in ATG5 KO cells but not in pentaKOs, consistent with a reported role of p6210,11.

Figure 1. Identifying autophagy receptors required for PINK1/Parkin mitophagy.

a, WT, OPTN KO, NDP52 KO, N/O (NDP52/OPTN) DKO, N/O/Tx (NDP52/OPTN/TAX1BP1) TKO, and pentaKO (NDP52/OPTN/TAX1BP1/NBR1/p62) HeLa cells were confirmed by immunoblotting. b, Cells as indicated with or without mCherry-Parkin (mCh-Parkin) were analyzed by immunoblotting and c, CoxII levels quantified. d, Representative images of mCh-Parkin expressing WT, pentaKO and ATG5 KO cells immunostained to label mitochondrial DNA (green) and e, quantified for mitophagy (24 h OA). >75 cells were counted per sample. f, Lysates from pentaKOs expressing mCh-Parkin and GFP-tagged autophagy receptors were immunoblotted and g, CoxII levels were quantified. Quantification in c, e and g are mean ± s.d. from 3 independent experiments and use one-way ANOVA (***P<0.001). OA, Oligomycin and Antimycin A. Scale bars, 10 μm.

The five endogenous receptors in WT cells (Extended Data Fig. 1c) and each receptor re-expressed in pentaKOs (Extended Data Fig. 1e, f) translocated to mitochondria after OA treatment. However, in pentaKOs only GFP-NDP52, GFP-OPTN and to a lesser extent, GFP-TAX1BP1, rescued mitophagy (Fig. 1f, g). Another recently reported autophagy receptor, Tollip12, neither recruited to mitochondria nor rescued mitophagy following OA treatment (Extended Data Fig. 1g–i).

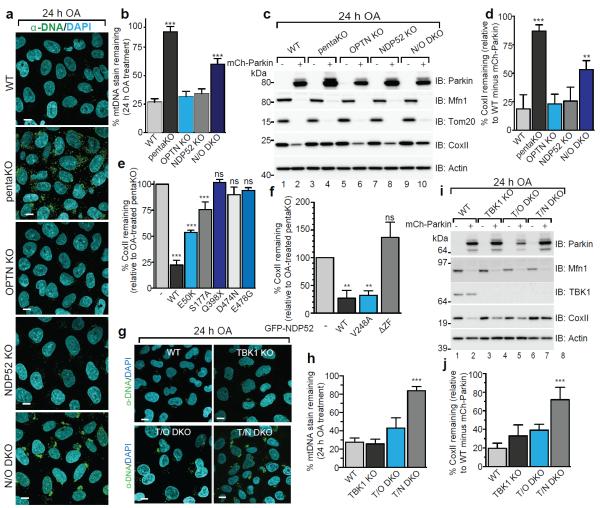

We generated single OPTN, NDP52 KO and NDP52/OPTN double KO (N/O DKO) and NDP52/OPTN/TAX1BP1 triple KO (N/O/Tx TKO) cell lines (Supplementary Table 1, Fig. 1a) and found no compensatory change in the expression of the remaining receptors. NDP52 or OPTN KO alone caused no defect in mitophagy, whereas NDP52/OPTN DKO and to a greater extent, NDP52/OPTN/TAX1BP1 TKO inhibited mitophagy (Fig. 2a–d, Extended Data Fig. 2a, b). The robust mitophagy observed in OPTN KOs contrasts with a report indicating loss of mitophagy using RNAi-mediated knockdown of OPTN in HeLa cells9. Although NDP52 and OPTN redundantly mediate mitophagy, they function non-redundantly in xenophagy13. Their expression levels in human tissues indicate that OPTN or NDP52 may function more prominently in different tissues (Extended Data Fig. 2c).

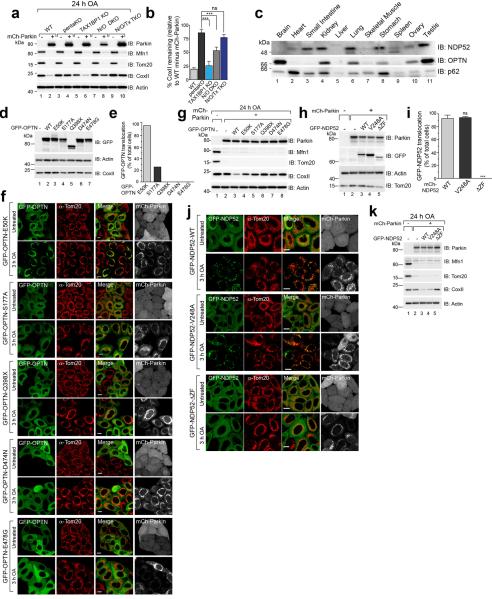

Figure 2. OPTN and NDP52 are redundant in PINK1/Parkin mitophagy.

a, Representative images of WT, pentaKO, OPTN KO, NDP52 KO and N/O (NDP52/OPTN) DKO cells expressing mCherry-Parkin immunostained with anti-DNA and b, quantified for mitophagy. c, Cell lines from a, were analyzed by immunoblotting and d, CoxII levels quantified. e, CoxII levels quantified from pentaKOs expressing mCherry-Parkin (mCh-Parkin) and rescued with WT or mutant GFP-OPTN (See Extended Data Fig. 2g for blots). f, CoxII levels quantified from pentaKOs expressing mCh-Parkin rescued with WT or mutant GFP-NDP52 (See Extended Data Fig. 2k for blots). g, Representative images of WT, TBK1 KO, T/O (TBK1/OPTN) DKO and T/N (TBK1/NDP52) DKO HeLa cells expressing mCherry-Parkin and immunostained with anti-DNA and h, mitophagy was quantified. i, Cells from g were immunoblotted and j, CoxII levels quantified. Quantification in b, d, e, f, h and i are mean ± s.d. from 3 independent experiments and use one-way ANOVA (***P<0.001, **P<0.005, ns, not significant). >75 cells were measured per confocal sample. OA, Oligomycin and Antimycin A. Scale bars, 10 μm. For untreated and mCherry-Parkin images of a and g, see Extended Data Fig. 3a and f, respectively.

Mutations in autophagy receptors can lead to diseases such as primary open angle glaucoma (POAG, OPTN; E50K)14, ALS (OPTN; E478G and Q398X)15 and Crohn's disease (NDP52; V248A)16. Defects in xenophagy occur when OPTN is mutated to block its phosphorylation by TANK-binding kinase 1 (TBK1; S177A) or ubiquitin binding (D474N)13,17. In pentaKOs, the UBAN-domain disrupting mutants OPTN-Q398X, OPTN-D474N and OPTN-E478G (Extended Data Fig. 2d) failed to translocate to mitochondria (Extended Data Fig. 2e, f) or rescue mitophagy (Fig. 2e, Extended Data 2g). OPTN-S177A weakly rescued mitophagy and minimally translocated to mitochondria, whereas OPTN-E50K robustly translocated and substantially rescued mitophagy (Fig. 2e, Extended Data Fig. 2e–g). NDP52-V248A fully recruited to mitochondria and rescued mitophagy, but a mutant lacking the ZF ubiquitin-binding domains (NDP52-ΔZF)18 did not (Extended Data Fig. 2h–k, Fig. 2f). Thus, ubiquitin binding by OPTN and NDP52 is necessary for mitophagy and some disease-causing mutations prevent mitophagy.

TBK1 and OPTN cooperate in mitophagy

TBK1 phosphorylation of OPTN at S177 increases its association with LC3 during xenophagy13, and the OPTN E50K mutation increases TBK1/OPTN binding19. TBK1 auto-phosphorylation at Ser172 is indicative of TBK1 activation20 and occurs in a Parkin-dependent manner following 3 h OA treatment, but only in cells expressing OPTN (Extended Data Fig. 3b, lanes 4 and 10). Prolonged OA treatment induces moderate TBK1 phosphorylation in the absence of Parkin but still requires PINK1 (Extended Data Fig. 3c). To investigate TBK1 function during mitophagy, we generated TBK1 KO, TBK1/NDP52 (T/N) DKO and TBK1/OPTN (T/O) DKO HeLa cells (Extended Data Fig. 3d, Supplementary Table 1). Parkin translocated to mitochondria in all lines, however, only TBK1/NDP52 DKOs displayed defective mitophagy (Extended Data Fig. 3e, Fig. 2g–j). Mitophagy in TBK1/NDP52 DKOs was rescued by WT-TBK1 or phospho-mimetic OPTN (OPTN-S177D), but not by kinase-dead TBK1 (TBK1-K38M) (Extended Data Fig. 3g–i). Thus, in the absence of NDP52, TBK1 is critical for effective mitophagy via OPTN.

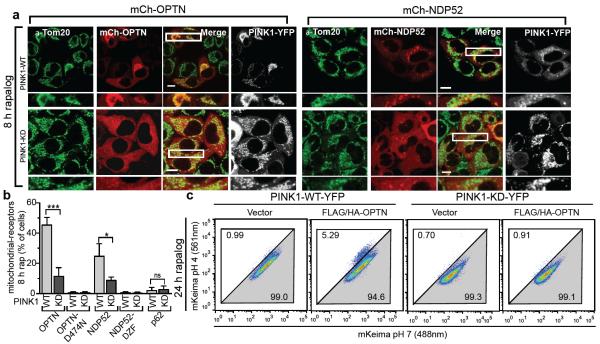

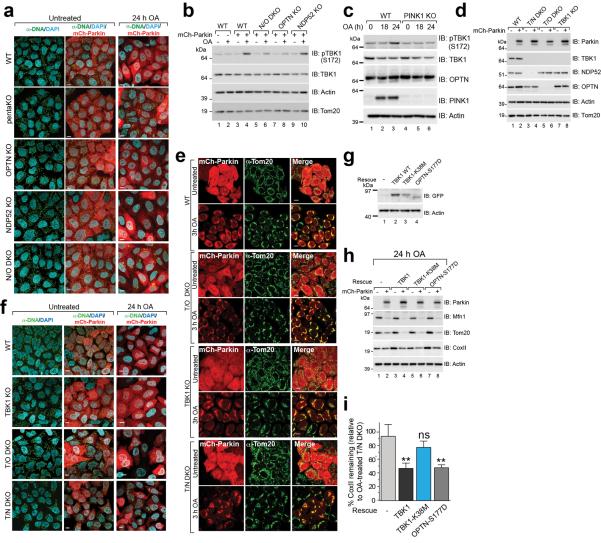

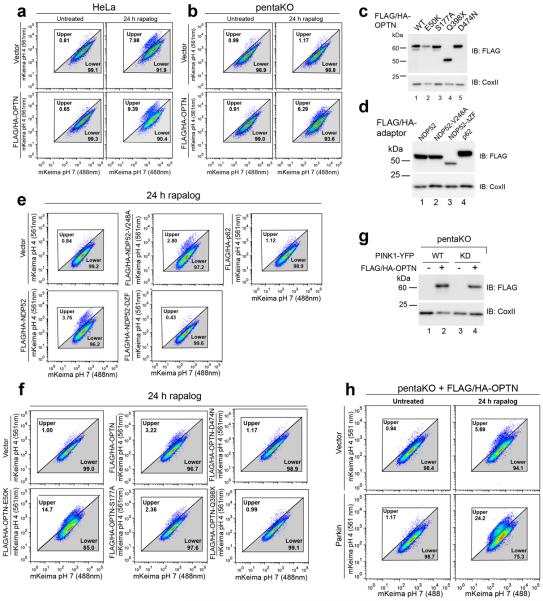

Ubiquitin phosphorylation in mitophagy

Since many autophagy receptors recruit to mitochondria following Parkin activation, why do only some function in mitophagy? Parkin-mediated mitophagy is driven by PINK1's phosphorylation of Ser65 of both ubiquitin5–7,21,22 and the UBL domain of Parkin23. Since Ser65 phospho-ubiquitin is structurally unique, it may differentially interact with ubiquitin binding proteins22. To determine whether OPTN is directly recruited to phospho-ubiquitin on mitochondria, we conditionally expressed PINK1 on undamaged mitochondria10 in HeLa cells lacking Parkin (Fig. 3a, Extended Data Fig. 4a). When PINK1Δ110-YFP-2xFKBP is cytosolic, mCherry-OPTN, mCherry-NDP52 and mCherry-p62 are also cytosolic (Extended Data Fig. 4b, c). When PINK1Δ110-YFP-2xFKBP is localized to FRB-Fis1 expressing mitochondria with rapalog, where ubiquitin on surface proteins24 (Extended Data Fig. 4a) can be phosphorylated5,21,25,26, OPTN and NDP52 are recruited (Fig. 3a, b), but p62 remains cytosolic (Fig. 3b, Extended Data Fig. 4c). OPTN/NDP52 recruitment requires PINK1 kinase activity (Fig. 3a, b) and receptor-ubiquitin binding, as OPTN-D474N and NDP52-ΔZF fail to recruit following rapalog treatment (Fig. 3b, Extended Data Fig. 4d, e). Therefore, PINK1 ubiquitin kinase activity recruits OPTN/NDP52 via ubiquitin binding domains to mitochondria in the absence of Parkin.

Figure 3. PINK1 recruits Optineurin and NDP52 independent of Parkin to promote mitophagy.

a, Representative images of HeLa cells expressing FRB-Fis1, WT (PINK1-WT) or kinase-dead (PINK1-KD) PINK1Δ110-YFP-2xFKBP and mCherry-OPTN (mCh-OPTN) or mCherry-NDP52 (mCh-NDP52) treated with rapalog. b, Quantification of receptor translocation in cells from a and Extended Data Fig. 4c–e. >100 cells were counted per sample. c, Cells were treated with rapalog and analyzed by FACS for lysosomal positive mt-mKeima. Representative data for WT or KD PINK1Δ110-YFP-2xFKBP in pentaKOs without or with FLAG/HA-OPTN expression. Quantification in b is displayed as mean ± s.d. from 3 independent experiments and uses one-way ANOVA tests (***P<0.001, *P<0.05, ns, not significant). For images of untreated cells from a, see Extended Data Fig. 4b. Scale bars, 10 μm.

To determine whether the observed autophagy receptor recruitment to mitochondria in the absence of Parkin can induce mitophagy, we developed a sensitive FACS based mitophagy assay. We expressed mitochondrial-targeted mKeima (mt-mKeima, see Online Methods) in WT and pentaKOs also expressing mitochondrial FRB-Fis1 and PINK1Δ110-YFP-2xFKBP. mt-mKeima engulfment into lysosomes results in a spectral shift due to low pH. Only 1% (range 0.89–1.15) of WT or pentaKO cells display mitophagy when PINK1 is cytosolic. However, when PINK1 is recruited to mitochondria with rapalog, mitophagy increases ~7-fold in WT cells and ~8-fold with overexpressed OPTN (Table 1, Extended Data Fig. 5a). PentaKOs showed no increase in mitophagy after targeting PINK1 to mitochondria (Table 1, Extended Data Fig. 5b). When rescued with FLAG/HA-OPTN or FLAG/HA-NDP52, pentaKOs displayed an increase in mitophagy of more than 5-fold and 4-fold, respectively (Table 1, Extended Data Fig. 5b–e). Rescue with FLAG/HA-p62 or ubiquitin-binding mutants (OPTN-Q398X, OPTN-D474N and NDP52ΔZF) failed to increase mitophagy above baseline, but other mutants (OPTN-E50K, OPTN-S177A and NDP52-V248A) rescued mitophagy (Table 1, Extended Data Fig. 5c–f). OPTN-E50K and S177A restored mitophagy as well as or better than WT OPTN (Table 1), differing from their response in the presence of Parkin (Fig. 2e) likely due to the lack of robust TBK1 activation in the absence of Parkin (Extended Data Fig 3b). Here, enhanced OPTN-E50K binding to TBK119 may become advantageous by allowing OPTN phosphorylation by TBK1 in the absence of Parkin thus improving mitophagy. In the absence of TBK1 activation, WT OPTN is likely not phosphorylated at S177 and thus is functionally similar to S177A OPTN. Importantly, ubiquitin kinase activity of PINK1 is required, as kinase-dead (KD) PINK1 did not induce mitophagy (Table 1, Fig. 3c, Extended Data 5g). Parkin expression dramatically increased mitophagy in FLAG/HA-OPTN expressing pentaKOs (Table 1, Extended Data Fig. 5h), supporting the model that PINK1-phosphorylated ubiquitin recruits receptors for mitophagy and Parkin ubiquitination of mitochondrial substrates amplifies this ubiquitin signal.

Table 1.

Rapalog-induced mitophagy

| Cell Type | rap | Avg. % | Fold Change | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | Vector | − | 1.15 | − | |

| + | 8.37 | 7.28 | |||

| OPTN | − | 1.08 | − | ||

| + | 8.59 | 7.95 | |||

| pentaKO | Vector | − | 0.93 | − | |

| + | 0.99 | 1.06 | |||

| OPTN | − | 0.89 | − | ||

| + | 4.83 | 5.43 | |||

| pentaKO | PINK1-WT | Vector | + | 1.13 | − |

| OPTN | + | 5.27 | 4.66 | ||

| PINK1-KD | Vector | + | 0.88 | 0.78 | |

| OPTN | + | 0.76 | 0.67 | ||

| pentaKO+NDP52 | − | + | 0.87 | − | |

| WT | + | 3.50 | 3.98 | ||

| V248A | + | 2.80 | 3.18 | ||

| ΔZF | + | 0.47 | 0.53 | ||

| pentaKO | p62 | + | 1.23 | 1.36 | |

| pentaKO+OPTN | − | + | 0.93 | − | |

| WT | + | 2.97 | 3.19 | ||

| E50K | + | 15.8 | 17.0 | ||

| S177A | + | 2.57 | 2.76 | ||

| Q398X | + | 0.87 | 0.78 | ||

| D474N | + | 0.76 | 0.67 | ||

| pentaKO+OPTN | − | − | 1.10 | − | |

| − | + | 5.30 | 4.81 | ||

| Parkin | − | 1.43 | − | ||

| Parkin | + | 23.60 | 16.50 | ||

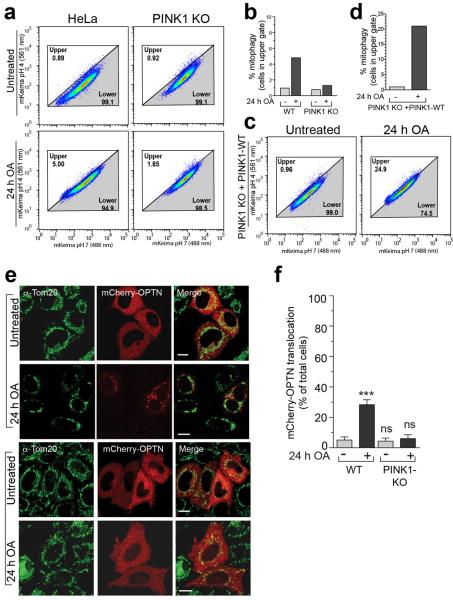

Comparing mitophagy induced by OA treatment in WT relative to PINK1KO cells confirmed that endogenous PINK1 mediates mitophagy in the absence of Parkin (Extended Data Fig. 6a, b). Re-expressing PINK1 in PINK1 KO cells rescued OA-induced mitophagy (Extended Data Fig. 6c, d). Furthermore, mCherry-OPTN is recruited to mitochondria in the absence of Parkin in a PINK1-dependent manner following prolonged exposure to OA (Extended Data Fig. 6e, f).

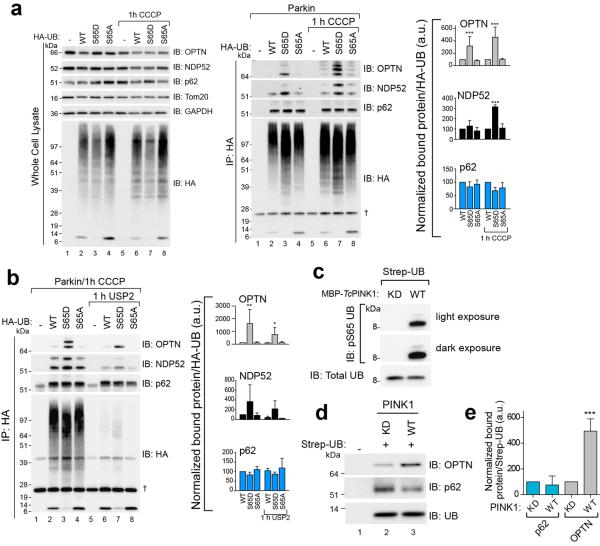

Given that PINK1 ubiquitin kinase activity can recruit OPTN and NDP52, we investigated autophagy receptor binding to phospho-mimetic (S65D) HA-ubiquitin in HeLa cells. Endogenous OPTN and NDP52 preferentially co-immunoprecipitate (co-IP) with HA-ubiquitinS65D (Extended Data Fig. 7a). Conversely, p62 was present at equal levels in all co-IPs (Extended Data Fig. 7a). Ubiquitin-modified and unmodified forms of OPTN and NDP52 were present in co-IPs, and HA-ubiquitinS65D induced or preserved this modification (Extended Data Fig. 7a). Co-IP samples treated with the deubiquitinase USP2 removed the ubiquitin-modified bands on OPTN and NDP52, yet OPTN and NDP52 retained HA-ubiquitinS65D binding (Extended Data Fig. 7b). Binding of endogenous receptors in HeLa cell cytosol to in vitro phosphorylated strep-tagged ubiquitin (Extended Data Fig. 7c) showed that OPTN, but not p62, bound better to phospho-ubiquitin (Extended Data Fig. 7d, e). However, recombinant GST-OPTN did not bind better to in vitro phosphorylated K63 linked ubiquitin chains27 indicating that OPTN may need additional factors or modification in vivo to preferentially bind Ser65 phosphorylated ubiquitin.

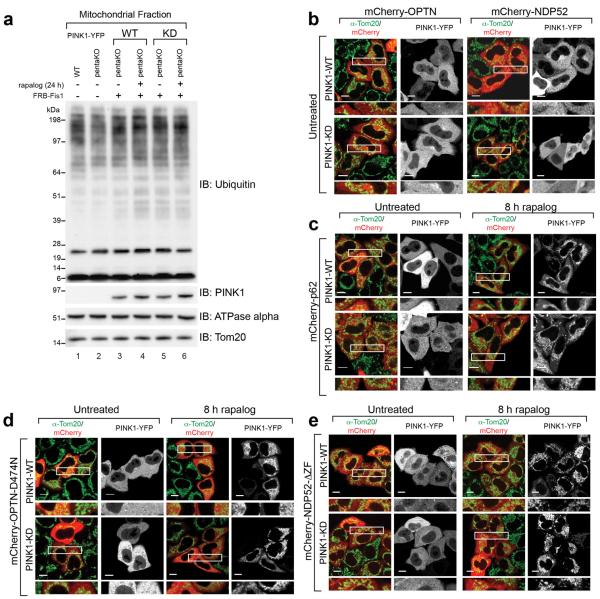

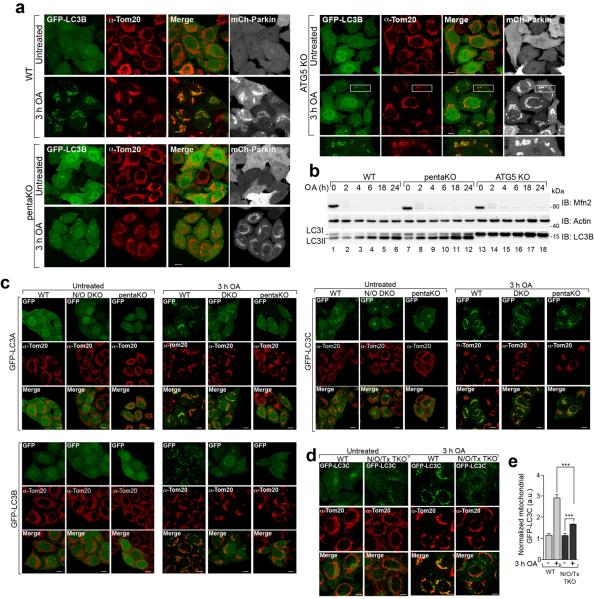

OPTN/NDP52 recruit upstream machinery

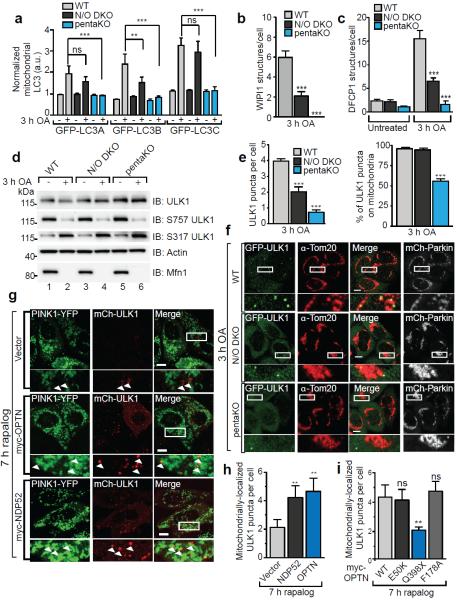

Autophagy receptors are thought to primarily function by bridging LC3 and ubiquitinated cargo1,2. In mCherry-Parkin WT cells, GFP-LC3B accumulated in distinct puncta adjacent to mitochondria after OA treatment (Extended Data Fig. 8a). Although OA also induced GFP-LC3B puncta in pentaKOs, they were fewer and not near mitochondria (Extended Data Fig. 8a). Conversely, GFP-LC3B in ATG5 KOs was near mitochondria, but not in puncta (Extended Data Fig. 8a). LC3B lipidation is retained in pentaKOs, but lost in ATG5 KOs (Extended Data Fig. 8b). This indicates that ATG5 is activated downstream of PINK1, but independently of autophagy receptors, and that LC3 lipidation and mitochondrial localization are independent steps of mitophagy.

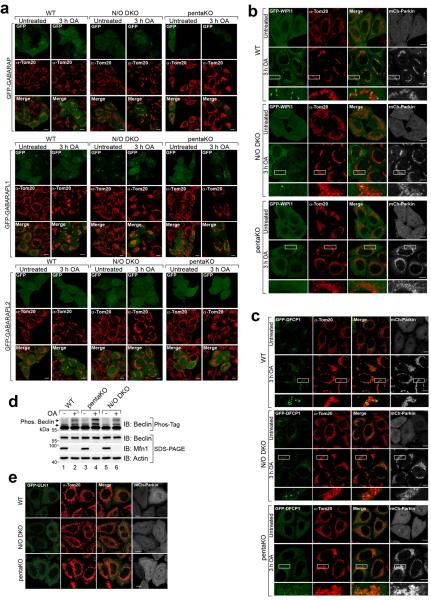

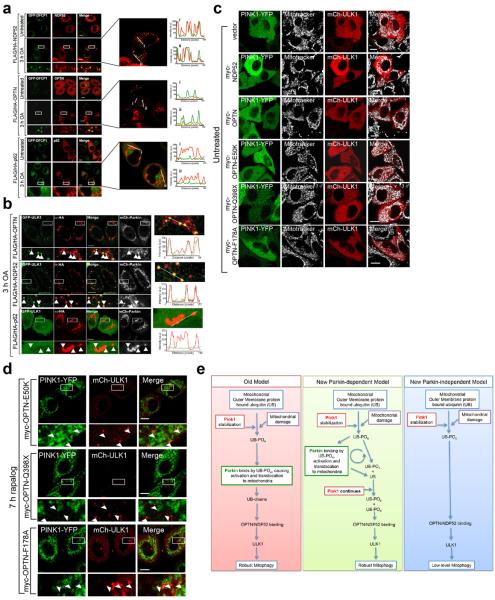

OPTN and NDP52 interact with LC3B and LC3C, respectively, for Salmonella clearance13,28. Beyond that, little is known about the specificity of LC3 family members toward autophagy receptors29 or their involvement in mitophagy. We examined the recruitment of all LC3/GABARAP family members to mitochondria in WT, pentaKO and NDP52/OPTN DKO cells. The OA-induced mitochondrial localization of GFP-LC3s in WT cells was absent in pentaKOs, while only GFP-LC3B recruitment was inhibited in NDP52/OPTN DKOs (Fig. 4a, Extended Data Fig. 8c). GFP-LC3C recruitment was inhibited in NDP52/OPTN/TAX1BP1 TKOs (Extended Data Fig. 8d, e), indicating that TAX1BP1 can recruit LC3C during mitophagy. GABARAPs did not recruit to mitochondria, indicating they likely play no substantial role in mitophagy (Extended Data Fig. 9a).

Figure 4. Characterization of autophagy receptor function during mitophagy.

mCherry-Parkin (mCh-Parkin) expressing WT, N/O (NDP52/OPTN) DKO and pentaKOs were quantified for a, GFP-LC3A, LC3B and LC3C translocation to mitochondria, b, GFP-WIPI1 or c, GFP-DFCP1 structures per cell (>100 cells counted for each sample) or d, were immunoblotted using phospho-specific anti-S757 and S317 ULK1 antibodies. e, mCherry-Parkin WT, N/O DKO and pentaKOs stably expressing GFP-ULK1 were quantified for GFP-ULK1 puncta per cell (left graph) and the percentage of those puncta on mitochondria (right graph). f, Representative data of e, cells were immunostained for Tom20 and GFP. g, pentaKOs expressing FRB-Fis1, PINK1Δ110-YFP-2xFKBP, mCherry-ULK1 (mCh-ULK1) and myc-tagged receptors, were treated with rapalog then imaged live. h, Quantification of mitochondrial ULK1 puncta in g. i, Quantification of mitochondrial ULK1 puncta in pentaKOs expressing FRB-Fis1, PINK1Δ110-YFP-2xFKBP, mCh-ULK1 and myc-OPTN mutants, treated with rapalog then imaged live. Quantification in a, b, c, e, h and i are mean ± s.d. from 3 independent experiments and use one-way ANOVA. (***P<0.001, **P<0.005, *P<0.05, ns, not significant). For live cell quantification >75 cells counted in a blinded manner. Quantification in h and i were performed after removal of outliers, see Online Methods for details. OA, Oligomycin and Antimycin A. Scale bars, 10 μm. a.u., arbitrary units. See Extended Data Figs. 8c, 9b, c and 10d for representative images of a, b, c, and i respectively. See Extended Data Fig. 9e untreated samples of f and Extended Data Fig. 10c for untreated images of h and i.

We also examined the involvement of WIPI1 and DFCP1, two proteins that mediate phagophore biogenesis upstream of LC330, in mitophagy. In WT cells, OA induced foci of both GFP-WIPI1 and GFP-DFCP1, mostly localized on or near mitochondria (Fig. 4b, c, Extended Data Fig. 9b, c). In NDP52/OPTN DKOs, GFP-WIPI1 and GFP-DFCP1 foci were reduced and were almost undetectable in pentaKOs (Fig. 4b, c, Extended Data Fig. 9b, c). Despite this, phosphorylation of Beclin131 was normal in both pentaKOs and NDP52/OPTN DKOs (Extended Data Fig. 9d), indicating that failure to recruit WIPI1/DFPC1 was not due to defective Vps34 complex. GFP-DFCP1 recruitment in pentaKOs was rescued by expression of FLAG/HA-OPTN or FLAG/HA-NDP52, but not by FLAG/HA-p62 (Extended Data Fig. 10a).

Though autophagy receptors are thought to function late in autophagy with LC332, the deficit in WIPI1 and DFCP1 recruitment to mitochondria indicates a defect upstream in autophagosome biogenesis. ULK1 phosphorylation by AMPK at S317 and dephosphorylation at S75733, required for activation, occurs comparably in WT, NDP52/OPTN DKO and pentaKO cells (Fig. 4d). Despite this, ULK1 localization to mitochondria34 following OA is diminished by half in the NDP52/OPTN DKOs and more than 80% in pentaKOs (Fig. 4e, f). FLAG/HA-OPTN or FLAG/HA-NDP52, but not FLAG/HA-p62, rescued GFP-ULK1 localization in pentaKOs (Extended Data Fig. 10b). Overall, these data indicate that NDP52 and OPTN recruit ULK1 to initiate mitophagy.

We next assessed if ubiquitin phosphorylation, independent of Parkin, is also sufficient to recruit ULK1 to mitochondria. Rescue of pentaKOs expressing FRB-Fis1 and PINK1Δ110-YFP-FKBP with myc-OPTN or myc-NDP52 resulted in mitochondrial ULK1 puncta following rapalog treatment (Fig. 4g, h). Myc-OPTN-E50K also rescued ULK1 recruitment to mitochondria, but ALS-associated mutant myc-OPTN-Q398X did not (Fig. 4i, Extended Data Fig. 10d). ULK1 recruitment was restored by myc-OPTN-F178A (Fig. 4i, Extended Data Fig. 10d), a mutation that disrupts OPTN association with LC312, indicating that ULK1 recruitment is not through LC3 interaction and occurs upstream of LC3. Taken together, our data show that PINK1 ubiquitin-kinase activity is sufficient to recruit the autophagy receptors and upstream autophagy machinery to mitochondria to induce mitophagy.

Conclusions

Through genetic knockout of five autophagy receptors we have defined their relative roles in mitophagy and identified their unanticipated upstream involvement in autophagy machinery recruitment. p62 and NBR1 are dispensable for Parkin-mediated mitophagy; OPTN and NDP52 are the primary, yet redundant, receptors. We also uncovered a new and more fundamental role for PINK1 in mitophagy: to directly induce mitophagy through phospho-ubiquitin-mediated recruitment of autophagy receptors. We posit that PINK1 generates the novel and essential signature (phospho-ubiquitin) on mitochondria to induce OPTN and NDP52 recruitment and mitophagy; Parkin acts to increase this signal by generating more ubiquitin chains on mitochondria, which are subsequently phosphorylated by PINK1. Our findings clarify the role of Parkin as an amplifier of the PINK1-generated mitophagy signal, phospho-ubiquitin, which can engage the autophagy receptors to recruit ULK1, DFCP1, WIPI1 and LC3 (see model in Extended Data Fig. 10e).

Online Content

Methods, along with any additional Extended Data display items, are available in the online version of the paper; references unique to these sections appear only in the online paper.

METHODS

Cell Culture, Antibodies and Reagents

HEK293T, HeLa and PINK1 KO35 cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified eagle medium (Life Technologies) supplemented with 10% (v/v) Fetal Bovine Serum (Gemini Bio Products), 10 mM HEPES (Life Technologies), 1 mM Sodium Pyruvate (Life Technologies), nonessential amino acids (Life Technologies) and GlutaMAX (Life Technologies). HeLa cells were acquired from the ATCC and authenticated by the Johns Hopkins GRCF Fragment Analysis Facility using STR profiling. All cells were tested for mycoplasma contamination bimonthly using the PlasmoTest kit (InvivoGen). Transfection reagents used were: Effectene (Qiagen), Lipofectamine LTX (Life Technologies), Avalanche-OMNI (EZ Bio-systems), X-tremeGENE HP (Roche) and X-tremeGENE 9 (Roche).

Rabbit monoclonal and polyclonal antibodies used: Beclin, pULK1-S317, pULK1-S757, TBK1, pTBK1-S172, NDP52, TAX1BP1, ATG5, Actin, and HA (Cell Signaling Technologies); GAPDH and LC3B (Sigma); ULK1 and Tom20 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology); Optineurin (OPTN) (Proteintech); GFP (Life Technologies); pSer65 ubiquitin (Millipore) and Mfn1 was generated previously36. Mouse monoclonal antibodies used: NBR1 and p62 (Abnova), Cytochrome C oxidase subunit II (CoxII, Abcam), Parkin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), DNA (Progen Biotechnik), ubiquitin (Cell Signaling). Chicken anti-GFP (Life Technologies) was also used. For catalog numbers see Supplementary Table 1. Human tissue panel blots were purchased (NOVUS Biologicals).

Generation of knockout lines using TALEN and CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing

To generate knockout cell lines, TALENs and CRISPR gRNAs were chosen that targeted an exon common to all splicing variants of the gene of interest (listed in Supplementary Table 1). Transcription activator-like effector nuclease (TALEN) was used to generate the OPTN KO HeLa cell line. The TALEN constructs were generated by sequential ligation of coding repeats into pcDNA3.1/Zeo-Talen(+63), as previously described37–39. The CRISPR/Cas9 system generated by the Church lab40, was used to knockout ATG5, NDP52, TAX1BP1, NBR1, p62 and TBK1. Oligonucleotides (Operon) containing CRISPR target sequences were annealed and ligated into AlfII-linearized gRNA vector (Addgene)40. For CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing, HeLa cells were transfected with gRNA constructs, hCas9 (Addgene) and pEGFP-C1 (Clontech), or for TALEN gene editing HeLa cells were transfected with OPTN TALEN constructs and pEGFP-C1. Two days after transfection, GFP-positive cells were sorted by fluorescence activated cell sorting and plated in 96-well plates. Single colonies were expanded into 24-well plates before screening for depletion of the targeted gene product by immunoblotting. As a secondary screen of some knockout lines, genomic DNA was isolated from cells and the genomic regions of interest were amplified using PCR followed restriction enzyme digestion analysis (primers listed in Supplementary Table 1). Sequencing of targeted genomic regions of knockout lines was also conducted to confirm the presence of frameshifting indels in the genes of interest (Supplementary Table 1). To generate multiple gene knockout cell lines, parental cell lines were transfected sequentially with one or multiple gRNA constructs to generate desired knockout lines. Parental cell lines are outlined in Supplementary Table 1.

Cloning and generation of stable cell lines

pMXs-puro-GFP-WIPI1 and pMXs-puro-GFP-DFCP1 were a kind gift from Dr. N. Mizushima (University of Toyko, Japan) and pMXs-IP-GFP-ULK1 was purchased from Addgene (#38193). To generate pBMN-mEGFP-C1, mEGFP-C1 (Addgene #36412) was PCR amplified (together with the multiple cloning site) and cloned into pBMN-Z at BamHI/SalI sites using the Gibson Cloning kit (New England BioLabs) according to manufacturer's instructions. The BamHI and SalI sites used to insert mEGFP-C1 were not regenerated. The following GFP-tagged plasmids were generated by PCR amplification of open reading frames followed by ligation into pBMN-mEGFP-C1: OPTN, NDP52, p62, TAX1BP1, NBR1, LC3A, LC3B, LC3C, GABARAP, GABARAPL1, GABARAPL2. The Gateway Cloning (Invitrogen) system was used to generate GFP-, mCherry-, myc- and FLAG/HA-constructs. Briefly, TBK1, TBK1-K38M, NDP52, OPTN, p62, DFCP1, WIPI1 and ULK1 were cloned into pDONR2333. Mutations in cDNA sequences were introduced using PCR site directed mutagenesis in the pDONR2333 vector, (sequences of mutagenesis primers used are available upon request) then recombined into pHAGE-N-FLAG/HA, pHAGE-N-GFP, pHAGE-N-mCherry and/or pDEST-N-myc using LR Clonase (Invitrogen) as per the manufacturer's protocol. All constructs generated in this study were verified by sequencing.

To generate stably transfected cell lines, retroviruses (for pBMN-mEGFP-C1 constructs, pBMN-mCherry-Parkin, pBMN-puro-P2A-FRB-Fis1, pCHAC-mt-mKeima-IRES-MCS2) and lentiviruses (for pHAGE- and pDEST- constructs) were packaged in HEK293T cells. HeLa cells were transduced with virus for 24 h with 8 μg/ml polybrene (Sigma) then optimized for protein expression via selection (puromycin or blasticidin) or fluorescence sorting.

Translocation and mitophagy treatments

Cells were either left untreated or treated with 10 μM Oligomycin (Calbiochem), □ μM Antimycin A (Sigma) (referred to as OA) in fresh growth medium for different periods of time as indicated in the figures. Some experiments were performed with 10 μM Carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenyl hydrazine (CCCP) as indicated (Sigma-Aldrich). We chose to use OA to depolarize mitochondria in most of our experiments, as they are specific mitochondrial respiratory complex inhibitors and less toxic. Long treatment time points of both OA and CCCP were also supplemented with the apoptosis inhibitor 20 μM QVD (ApexBio) to prevent cell death.

Immunoblotting and Phos-Tag gels

HeLa cells seeded into 6-well plates were either untreated or treated with 10 μM Oligomycin (Calbiochem), □ μM Antimycin A (Sigma) and 20 μM QVD (ApexBio) in fresh growth medium for different periods of time as indicated in figure legends. Cells were lysed in 1X LDS sample buffer (Life Technologies) supplemented with 100 mM dithiothreitol (DTT, Sigma) and heated to 99 °C with shaking for 7–10 minutes. 25–50 μg of protein per sample was separated on 4–12% Bis-Tris gels (Life Technologies) according to manufacturer's instructions and then transferred to polyvinyl difluoride membranes and immunoblotted using antibodies as indicated in figure legends. To assess mitophagy, CoxII quantification was conducted using ImageLab software (BioRad). For uncropped images of all immunoblots, see Supplementary Information.

To dephosphorylate samples, cells were collected as above and lysed in 1X NEB Buffer 3 (New England BioLabs) supplemented with 1% Triton X-100 and passed through a 26.5 gauge needle. Calf intestinal phosphatase (CIP, New England BioLabs) was added to half the cell lysate and the other half was used as an untreated control. Both samples were incubated for 1 h at 37 °C and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting.

To analyze Beclin phosphorylation, lysates were prepared in sample buffer lacking EDTA and run on 8% Tris-Glycine gels containing 20 μM Phos-Tag (Wako) and 40 μM MnCl2 as described previously31. Gels lacking Phos-Tag were run simultaneously as a negative control. Electrophoresis and western transfer were carried out using standard protocols with the exception that Phos-Tag gels were incubated in 10 mM EDTA for 10 min to remove excess Mn2+ prior to transfer.

Immunoprecipitation

WT or PINK1 KO HeLa cells were transiently transfected with HA-tagged ubiquitin WT, S65A or S65D with or without mCherry-Parkin for 24 h. Cells were harvested, lysed and the HA-ubiquitin was immunoprecipitated as reported previously5, using anti-HA conjugated beads (Pierce). To deubiquitinate the bound proteins, after binding the HA-ubiquitin, beads were washed three times and incubated in 50 mM Tris-Cl (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM DTT and 1.47μg USP2 (Boston Biochem) at 37 °C for 1 h. The reaction was stopped and the remaining bound were proteins were washed 5 times with 1 mL of buffer (50 mM Tris-Cl (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl), then eluted by boiling with 1X LDS sample buffer.

In vitro phosphorylation

Strep-tagged ubiquitin was incubated with either TcPINK1 WT or kinase-dead as previously reported5. This ubiquitin was then incubated with cytosol from WT HeLa cells in 20 mM HEPES-KOH, pH 7.6, 220 mM mannitol and 70 mM sucrose at 4°C for 1 h. Strep-Tactin beads (Qiagen) were then added to bind the strep-ubiquitin for an additional 1 h at 4°C. The ubiquitin and bound proteins were then eluted with 50 mM biotin in 50 mM Tris for 15 min at room temperature (RT). Samples were then diluted in LDS sample buffer prior to SDS-PAGE and immunoblot analysis.

Immunofluorescence microscopy

HeLa cells, seeded in 2-well chamber slides (Lab-Tek), were treated as indicated in the figures legends. Following treatment, cells were rinsed in PBS and fixed for 15 min at RT with 4% paraformaldehyde. Cells were then permeabilized and blocked with 0.1% Triton X-100, 3% goat serum in PBS for 40 minutes at RT. For immunostaining, cells were incubated with antibodies (as indicated in figure legends) diluted in 3% goat blocking serum overnight at 4 °C, then rinsed with PBS and incubated with either anti- rabbit or mouse Alexa Fluor- 488 and 633 conjugated secondary antibodies (Life Technologies), or anti-chicken Alexa Fluor 488 conjugated antibody (Life Technologies) for 1 h at RT. Cells were washed 3 times for 5 min each with 1% Triton X-100, PBS. During the final wash step, cells were incubated with DAPI (10 μg/mL DAPI, Sigma) in PBS for 5 min. To measure mitophagy by mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) immunostaining; images were collected from samples stained with DAPI and immunostained for DNA using a plan-Apochromat 63×/1.4 oil DIC objective on an LSM 510 microscope (Zeiss). Four image slices were collected through the Z plane encompassing the top and bottom of the cells. Image analysis was performed on all images collected in the Z plane using Volocity software (Perkin Elmer v6.0.1). The percent mtDNA stain remaining was calculated using the following formula: (cDNAv-nDNAv)/n, where cDNAv= the total cellular DNA volume determined by staining using anti-DNA antibodies and, nDNAv = the total nuclear DNA stain volume determined using DAPI, and n= the number of cells. The mtDNA stain volume in untreated cells was normalized to 100% and the amount of mtDNA stain remaining after drug treatment was subsequently determined. Final values represent data acquired from 50–200 cells from three independent experiments.

To analyze LC3/mitochondria protein colocalization; cells were treated, fixed and immunostained as above. Between 5–8 slices were imaged through the Z plane using either a plan-Apochromat 63× or 100×/1.4 oil DIC objective on a CW STED confocal microscope (Leica). Volocity software (Perkin Elmer, v6.0.1) was used to measure intensity of the GFP signal representing LC3 in the volume occupied by mitochondria (as defined by Tom20 positive region) and the cytosol (as defined by Tom20 negative region). “Normalized mitochondrial LC3” was calculated using the following formula: Normalized mitochondrial LC3 = (mi/mv)/(ci/cv), where mi = mitochondrial GFP intensity, mv = mitochondrial volume, ci = cytosolic GFP intensity and cv= cytosolic volume. The resulting Normalized mitochondrial LC3 is equal to 1 if the intensity of GFP is equal per volume in the cytosolic and mitochondrial volumes (no translocation) and is above one if the mitochondrial intensity is higher per volume (translocation). Final values for Normalized mitochondrial LC3 represents data acquired from 50–105 cells from three independent experiments.

For GFP-DFCP1, GFP-WIPI1 and GFP-ULK1 puncta analysis; cells were treated, prepared and imaged on the CW STED as above with the addition of immunofluorescence using either rabbit or chicken GFP antibodies to enhance the signal in the green channel. For GFP-DFCP1, puncta were quantified using Volocity software (Perkin Elmer v6.0.1) and for GFP-WIPI1 and GFP-ULK1 puncta were quantified manually. Colocalization of autophagy receptors with GFP-DFCP1 or GFP-ULK1 was assessed with line scans using LAS AF software (Leica, v.2.6.0.7266).

Heterodimerization

The C-terminal Fis1 tail of human Fis1 (amino acids 92–152) was cloned into pC4-RhE vector (ARIAD) at SpeI/BamHI sites to make FRB-Fis1 construct, the insert of which was then PCR amplified and cloned into pBMN-Z vector together with Puro-P2A sequence at HindIII, XhoI and NotI sites by In-Fusion kit from Clontech to make pBMN-puro-P2A-FRB-Fis1. For receptor translocation assays, WT HeLa cells stably expressing FRB-Fis1 were generated using retroviral transduction as described above. Previously generated PINK1Δ110-YFP-2xFKBP41 WT and KD and individually each mCherry-tagged autophagy receptor were transfected into FRB-Fis1 stable HeLa cells for 24 h. Cells were then treated with 0.5 μM rapalog (Clontech) for 8 h as previously described41. Cells were then fixed and stained as described above. Cells were manually counted for translocation of mCherry-tagged autophagy receptors to mitochondria. Final values represent data collected from 100–150 cells for three independent experiments.

For ULK1 and DFCP1 rescue analysis, pentaKO HeLa cells stably expressing FRB-Fis1 were transiently transfected with PINK-1Δ110-YFP-2xFKBP, mCherry-ULK1 and one of the autophagy receptors: myc-OPTN, myc-NDP52, myc-OPTN-F178A, myc-OPTN-E50K or myc-OPTN-Q398X for 18–24 h. Cells were treated with 0.5 μM Rapalog or 100% ethanol (vehicle) for 7 h and imaged live on a Zeiss 780 in a humidified 37°C/5% CO2 chamber. To visualize mitochondria in vehicle -treated controls, cells were pre-incubated for 10 minutes in 75 nM Mitotracker Deep Red (Invitrogen) prior to imaging. Fields of PINK1-YFP positive cells were imaged blindly to the mCherry-containing channel. The images were then blinded and counted manually for translocation of mCherry-tagged ULK1 to mitochondria. Final values represent >75 cells counted over at least two independent experiments.

Mito-Keima mitophagy assay

mt-mKeima42 (a gift from A. Miyawaki, Brain Science Institute, RIKEN, Japan) was cloned into pCHAC-MCS-1-IRES-MCS2 vector (Allele Biotechnology). PINK1(Δ110)-YFP-2xFKBP WT and KD were PCR amplified from the original pC4 and cloned into pRetroQ-AcGFP-C1 at NheI/XhoI sites by Gibson assembly kit. HA-tag was removed and stop codon is introduced. WT and 5KO pentaKO HeLa cells stably expressing FRB-Fis1, mt-mKeima and either WT or KD PINK1Δ110-YFP-2xFKBP were generated using retroviral transduction as described above. FLAG/HA-receptors were stably-expressed in these cells by lentivirus transduction as described above then treated with 0.5 μM rapalog for 24 h. Cells were then resuspended in sorting buffer (145 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 1.8 mM CaCl2, 0.8 mM MgCl2, 10 mM HEPES, 10 mM glucose, 0.1% BSA) containing 10 μg/mL DAPI. Analysis was performed using Summit software (v6.2.6.16198) on a Beckman Coulter MoFlo Astrios cell sorter. Measurements of lysosomal mt-mKeima were made using dual-excitation ratiometric pH measurements at 488 (pH 7) and 561 (pH 4) nm lasers with 620/29 nm and 614/20 nm emission filters, respectively. For each sample, 50,000 events were collected and subsequently gated for YFP/mt-mKeima double-positive cells that were DAPI-negative. Data were analyzed using FlowJo (v10, Tree Star).

Statistical calculations

All statistical data were calculated and graphed using GraphPad Prism 6. To assess statistical significance, data from three or more independent experiments were analyzed using one-way ANOVA and Tukey's post-test with a confidence interval of 95%. All error bars are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (s.d.). In Fig.4h, i outliers were removed using ROUT in GraphPad Prism 6 with a Q=1%, 1–2 values from each condition were removed.

Extended Data

Extended Data Figure 1. Analysis of knockout cell lines and characterization of autophagy receptor translocation to damaged mitochondria.

a, ATG5 KO cell line confirmed by immunoblotting. b, Representative images of mitochondrial DNA nucleoids in HeLa cells immunostained with an α-DNA antibody (green) confirming colocalization with the mitochondrial marker Tom20 (red) (n=3). c, Mitochondrial fractions from mCherry-Parkin (mCh-Parkin) expressing pentaKO and WT cells were assessed by immunoblotting. d, mCh-Parkin expressing WT, pentaKO and ATG5 KOs were treated with OA or OA and MG132. Cell lysates were assessed by immunoblotting. e, Expression levels of GFP-tagged OPTN, NDP52, p62, NBR1 and TAX1BP1 re-expressed in pentaKOs by immunoblotting. f, Representative images of mCh-Parkin expressing pentaKOs from e immunostained for Tom20 (n=3). g, Expression of GFP-Tollip in mCh-Parkin pentaKOs. h, pentaKOs mCh-Parkin and with or without GFP-Tollip expression were immunoblotted. i, Representative images of mCh-Parkin pentaKOs expressing GFP-Tollip immunostained for Tom20 (n=3). Scale bars, 10 μm.

Extended Data Figure 2. OPTN, NDP52 and TAX1BP1 triple knockout analysis and disease-associated mutations.

a, KO cell lines with or without mCherry-Parkin (mCh-Parkin) expression were immunoblotted and b, CoxII levels were quantified. c, A panel of human tissue lysates was immunoblotted. d, Expression of WT or mutant GFP-OPTN in mCh-Parkin pentaKOs. e, Quantification of cells in f. >100 cells per condition. f, Representative images of mCh-Parkin pentaKOs expressing GFP-OPTN mutants immunostained for Tom20 (n=3). g, pentaKOs expressing mCh-Parkin were rescued with WT or mutant GFP-OPTN, analyzed by immunoblotting. See Fig. 2e for quantification of CoxII. h, Expression of WT or mutant GFP-NDP52 in mCh-Parkin pentaKOs. i, Quantification of cells in j. >100 cells per condition. j, Representative images of mCh-Parkin pentaKOs expressing WT or mutant GFP-NDP52 were immunostained for Tom20 (n=3). k, pentaKOs expressing mCh-Parkin rescued with WT or mutant GFP-NDP52 were analyzed by immunoblotting. See Fig. 2f for quantification of CoxII. Quantification in b and i are displayed as mean ± s.d. from 3 independent experiments using one-way ANOVA tests (***P<0.001, ns, not significant) and in e as mean from 2 independent experiments. Scale bars, 10 μm.

Extended Data Figure 3. TBK1 in activates OPTN in PINK1/Parkin mitophagy.

a, Representative images of untreated mCherry-Parkin (mCh-Parkin) cells and merged images of treated cells as indicated immunostained for DNA. See Fig. 2a for anti-DNA/DAPI images of treated samples (n=3). b, Cell lysates from WT, N/O (NDP52/OPTN) DKO, OPTN KO and NDP52 KO cells with or without mCh-Parkin expression were immunoblotted for TBK1 activation. c, Cell lysates from WT and PINK1 KO cells without Parkin expression were immunoblotted for TBK1 activation (S172 phosphorylation). d, Confirmation of T/N (TBK1/NDP52) DKO, T/O (TBK1/OPTN) DKO and TBK1 KO by immunoblotting. e, KO cell lines from d were immunostained for Tom20 (n=3). f, Representative images of untreated mCh-Parkin WT and KO cells, and merged images of treated cells as indicated were immunostained for DNA. See Figure 2g for anti-DNA/DAPI images treated samples (n=3). g, T/N DKO cells rescued with GFP-TBK1 WT or K38M, or GFP-OPTN S177D and were assessed by immunoblotting. h, Cells in g were assessed by immunoblotting. i, Quantification of CoxII levels in h displayed as mean ± s.d. from 3 independent experiments and use one-way ANOVA tests (**P<0.005, ns, not significant). OA, Oligomycin and Antimycin A. Scale bars, 10 μm.

Extended Data Figure 4. Parkin-independent recruitment of receptors to mitochondria through PINK1 activity.

a, Isolated mitochondria from WT and pentaKOs with or without FRB-Fis1 and with WT or kinase-dead (KD) PINK1Δ110-YFP-2xFKBP were immunoblotted. b–e, Representative images of pentaKOs expressing FRB-Fis1, WT (PINK1-WT) or kinase-dead (PINK1-KD) PINK1Δ110-YFP-2xFKBP and either (b) mCherry-OPTN or mCherry-NDP52, (c) mCherry-p62, (d) mCherry-OPTN-D474N or (e) mCherry-NDP52-ΔZF. Cells were (b) untreated or (c–e) treated with rapalog then immunostained for Tom20. All images are representative of three independent experiments. See Figure 3b for quantification. Scale bars, 10 μm.

Extended Data Figure 5. PINK1 directly stimulates mitophagy in the absence of mitochondrial damage.

a, b, Cells were treated with rapalog and analyzed by FACS for lysosomal positive mt-mKeima. Representative data for WT HeLa (a) and pentaKO (b) without or with FLAG/HA-OPTN. c, d, Cell lysates from pentaKOs expressing FRB-Fis1, PINK1Δ110-YFP-2xFKBP, mt-mKeima and (c) WT FLAG/HA-OPTN or mutants, (d) FLAG/HA-p62, WT FLAG/HA-NDP52 or NDP52 mutants as indicated were assessed for receptor expression by immunoblotting. e, f, Cells from c and d were rapalog treated analyzed by FACS for lysosomal positive mt-mKeima. Representative data of two experiments is presented. g, Cell lysates from pentaKOs expressing FRB-Fis1, with or without FLAG/HA-OPTN and WT or kinase-dead (KD) PINK1Δ110-YFP-2xFKBP were assessed for OPTN by immunoblotting. h, FLAG/HA-OPTN pentaKOs expressing FRB-Fis1, PINK1Δ110-YFP-2xFKBP, mt-mKeima transfected and either vector or untagged Parkin were analyzed by FACS. Representative data of two experiments is presented.

Extended Data Figure 6. PINK1 directly stimulates mitophagy upon mitochondrial damage.

Representative data of mt-mKeima-expressing a, WT, PINK1 KO or c, PINK1 KO rescued with PINK1-WT cells treated with OA then analyzed by FACS. b, d, Average percent mitophagy for two replicates of a and c, respectively. e, Representative images of WT HeLa cells expressing mCherry-OPTN and treated with OA as indicated were immunostained for Tom20 (n=3). f, Quantification of mCherry-OPTN translocation from cells in e. Data displayed as mean ± s.d. from 3 independent experiments and using one-way ANOVA tests (***P<0.001, ns, not significant).

Extended Data Figure 7. OPTN and NDP52 preferentially bind phospho-mimetic ubiquitin.

a, HeLa cells expressing mCherry-Parkin (Parkin) and HA-ubiquitin (HA-UB) WT, S65D or S65A were treated with CCCP. HA-UB was co-immunoprecipitated and the bound fraction was analyzed by immunoblotting. Quantification of the total bound fraction of OPTN, NDP52 and p62 are shown. b, HA-ubiquitin transfected into HeLa cells with mCherry-Parkin were treated with CCCP. HA-ubiquitin was immunoprecipitated. The bound fraction was treated with the deubiquitinase USP2 and washed to remove all unbound protein following deubiquitination. Quantification of the total bound fraction of OPTN, NDP52 and p62 are shown in the right panel. c,d, Strep-tagged ubiquitin (Strep-UB) was incubated with either WT or kinase-dead (KD) PINK1 in an in vitro phosphorylation reaction, immunoblotted with an anti-phosphoS65 ubiquitin antibody (c) and was then incubated with cytosol harvested from untreated, WT HeLa cells. The ubiquitin was then pulled down using Strep-Tactin beads and (d) analyzed by immunoblotting. e, Quantification of bound OPTN and p62 normalized to total ubiquitin. Data displayed in a, b and e as mean ± s.d. from 3 independent experiments and use one-way ANOVA tests. (***P<0.001, **P<0.005, *P<0.05). †, non-specific band. a.u., arbitrary units.

Extended Data Figure 8. Analysis of LC3 family members and their translocation to damaged mitochondria in autophagy receptor KO cell lines.

a, Representative images of WT, pentaKO and ATG5 KO HeLa cells expressing mCherry-Parkin (mCh-Parkin) and GFP-LC3B were immunostained for Tom20 (n=3). b, Cell lysates from mCh-Parkin expressing WT, pentaKO and ATG5 KO cells were immunoblotted. c, Representative images of WT, N/O (NDP52/OPTN) DKO and pentaKOs expressing mCh-Parkin and either GFP-tagged LC3A, LC3B or LC3C were immunostained for Tom20 (n=3, see Figure 4a for quantification). d, Representative images of WT and N/O/Tx (NDP52/OPTN/TAX1BP1) TKO cells expressing mCh-Parkin and GFP-LC3C were immunostained for Tom20 (n=3) and e, quantified for GFP-LC3C translocation to mitochondria. Quantification in e is displayed as mean ± s.d. from 3 independent experiments and use one-way ANOVA tests (***P<0.001). OA, Oligomycin and Antimycin A. Scale bars, 10 μm.

Extended Data Figure 9. GABARAPs do not translocate to damaged mitochondria and early stages of autophagosome biogenesis mediated by WIPI1 and DFCP1 are inhibited in autophagy receptor deficient cell lines.

Representative images of WT, N/O (NDP52/OPTN) DKO and pentaKOs expressing mCherry-Parkin (mCh-Parkin) and either (a) GFP-tagged GABARAP, GABARAPL1 or GABARAPL2, (b) GFP-WIPI1 or (c) GFP-DFCP1 immunostained for Tom20 (n=3 for each condition, see Figure 4b, c for quantification of b and c). d, mCh-Parkin cell lines as indicated were subjected to either Phos-Tag SDS-PAGE or standard SDS-PAGE followed by immunoblotting. Arrows indicate the position of phosphorylated Beclin species. e, Representative images of untreated WT, N/O (NDP52/OPTN) DKO and pentaKO cell lines expressing mCh-Parkin and GFP-ULK1 were immunostained for Tom20 and GFP (n=3). OA, Oligomycin and Antimycin A. Scale bars, 10 μm.

Extended Data Figure 10. OPTN and NDP52 rescue DFCP1 and ULK1 recruitment deficit in pentaKOs.

a, Representative images of pentaKOs expressing mCherry-Parkin (mCh-Parkin), GFP-DFCP1 and the indicated FLAG/HA-tagged autophagy receptors immunostained for HA (n=2). Right-hand panels display co-localization of FLAG/HA-tagged constructs and GFP-DFCP1 by fluorescence intensity line measurement. b, Representative images of pentaKOs expressing mCherry-Parkin and GFP-ULK1 were rescued with FLAG/HA-OPTN, FLAG/HA-NDP52, and FLAG/HA-p62, and immunostained for HA and GFP. Arrows indicate HA-tagged receptor puncta (n=2). Right panels display colocalization of HA and GFP by fluorescence intensity line measurement. c, d, Representative images of pentaKOs stably expressing FRB-Fis1 and transiently expressing PINK1Δ110-YFP-2xFKBP and vector or myc-tagged receptors, were (c) untreated or (d) treated with rapalog and imaged live (n=3, see Figure 4h, i for quantification of c, d). OA, Oligomycin and Antimycin A. Scale bars, 10 μm. e, Old and new models of PINK1/Parkin mitophagy. The old model is dominated by Parkin ubiquitination of mitochondrial proteins. Here PINK1 plays a small initiator role whose main function is to bring Parkin to the mitochondria. The new model depicts Parkin-dependent and independent pathways leading to robust and low-level mitophagy, respectively. Based on our data, PINK1 is central to mitophagy both before and after Parkin recruitment by phosphorylating UB to recruit both Parkin and autophagy receptors mitochondria, to induce clearance. In the absence of Parkin (right panel), this occurs at a low level due to the relatively low basal UB on mitochondria. When Parkin is present it serves to amplify the PINK1 generated UB-PO4 signal, allowing for robust and rapid mitophagy induction.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank C. Nezich and Soojay Banerjee in the Youle lab, C. Smith at the NINDS Light Imaging Facility, and the NINDS and NHLBI Flow Cytometry Core Facilities. This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, NINDS and the National Health and Medical Research Council (GNT1063781).

Footnotes

Supplementary Information is available in the online version of the paper.

Author Contributions M.L., D.A.S, L.A.K. and R.J.Y conceived the projects; M.L., D.A.S, L.A.K. S.A.S., C.W., D.P.S., A.I.F. and R.J.Y. designed experiments; M.L., D.A.S, L.A.K. S.A.S., C.W., J.L.B., D.P.S and A.I.F. performed experiments; M.L., D.A.S, L.A.K. and R.J.Y wrote the manuscript and all authors contributed to editing the manuscript.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Svenning S, Johansen T. Selective autophagy. Essays in Biochem. 2013;55:79–92. doi: 10.1042/bse0550079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stolz A, Ernst A, Dikic I. Cargo recognition and trafficking in selective autophagy. Nat. Cell. Biol. 2014;16:495–501. doi: 10.1038/ncb2979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Narendra DP, et al. PINK1 Is Selectively Stabilized on Impaired Mitochondria to Activate Parkin. PLoS Biol. 2010;8:e1000298. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Narendra D, Tanaka A, Suen DF, Youle RJ. Parkin is recruited selectively to impaired mitochondria and promotes their autophagy. J. Cell Biol. 2008;183:795–803. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200809125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kane LA, et al. PINK1 phosphorylates ubiquitin to activate Parkin E3 ubiquitin ligase activity. J. Cell Biol. 2014;205:143–153. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201402104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kazlauskaite A, et al. Parkin is activated by PINK1-dependent phosphorylation of ubiquitin at Ser65. Biochem. J. 2014;460:127–139. doi: 10.1042/BJ20140334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Koyano F, et al. Ubiquitin is phosphorylated by PINK1 to activate parkin. Nature. 2014;510:162–166. doi: 10.1038/nature13392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Geisler S, et al. PINK1/Parkin-mediated mitophagy is dependent on VDAC1 and p62/SQSTM1. Nat. Cell. Biol. 2010;12:119–131. doi: 10.1038/ncb2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wong YC, Holzbaur ELF. Optineurin is an autophagy receptor for damaged mitochondria in parkin-mediated mitophagy that is disrupted by an ALS-linked mutation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2014;111:E4439–E4448. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1405752111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Narendra D, Kane LA, Hauser DN, Fearnley IM, Youle RJ. p62/SQSTM1 is required for Parkin-induced mitochondrial clustering but not mitophagy; VDAC1 is dispensable for both. Autophagy. 2010;6:1090–1106. doi: 10.4161/auto.6.8.13426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Okatsu K, et al. p62/SQSTM1 cooperates with Parkin for perinuclear clustering of depolarized mitochondria. Genes to Cells. 2010;15:887–900. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2010.01426.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lu K, Psakhye I, Jentsch S. Autophagic clearance of polyQ proteins mediated by ubiquitin-Atg8 adaptors of the conserved CUET protein family. Cell. 2014;158:549–563. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.05.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wild P, et al. Phosphorylation of the autophagy receptor optineurin restricts Salmonella growth. Science. 2011;333:228–233. doi: 10.1126/science.1205405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rezaie T, et al. Adult-onset primary open-angle glaucoma caused by mutations in optineurin. Science. 2002;295:1077–1079. doi: 10.1126/science.1066901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maruyama H, et al. Mutations of optineurin in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nature. 2010;465:223–226. doi: 10.1038/nature08971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ellinghaus D, et al. Association between variants of PRDM1 and NDP52 and Crohn's disease, based on exome sequencing and functional studies. Gastroenterology. 2013;145:339–347. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.04.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mankouri J, et al. Optineurin negatively regulates the induction of IFNbeta in response to RNA virus infection. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1000778. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thurston TL, Ryzhakov G, Bloor S, von Muhlinen N, Randow F. The TBK1 adaptor and autophagy receptor NDP52 restricts the proliferation of ubiquitin-coated bacteria. Nat. Immunol. 2009;10:1215–1221. doi: 10.1038/ni.1800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morton S, Hesson L, Peggie M, Cohen P. Enhanced binding of TBK1 by an optineurin mutant that causes a familial form of primary open angle glaucoma. FEBS Lett. 2008;582:997–1002. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.02.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Larabi A, et al. Crystal structure and mechanism of activation of TANK-binding kinase 1. Cell Rep. 2013;3:734–746. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.01.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ordureau A, et al. Quantitative proteomics reveal a feedforward mechanism for mitochondrial PARKIN translocation and ubiquitin chain synthesis. Mol. Cell. 2014;56:360–375. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wauer T, et al. Ubiquitin Ser65 phosphorylation affects ubiquitin structure, chain assembly and hydrolysis. EMBO J. 2015;34:307–325. doi: 10.15252/embj.201489847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kondapalli C, et al. PINK1 is activated by mitochondrial membrane potential depolarization and stimulates Parkin E3 ligase activity by phosphorylating Serine 65. Open Biol. 2012;2:120080. doi: 10.1098/rsob.120080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sarraf SA, et al. Landscape of the PARKIN-dependent ubiquitylome in response to mitochondrial depolarization. Nature. 2013;496:372–376. doi: 10.1038/nature12043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shiba-Fukushima K, et al. Phosphorylation of Mitochondrial Polyubiquitin by PINK1 Promotes Parkin Mitochondrial Tethering. PLoS Genet. 2014;10:e1004861. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Okatsu K, et al. Phosphorylated ubiquitin chain is the genuine Parkin receptor. J. Cell Biol. 2015;209:111–128. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201410050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ordureau A, et al. Defining roles of PARKIN and ubiquitin phosphorylation by PINK1 in mitochondrial quality control using a ubiquitin replacement strategy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2015;112:6637–6642. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1506593112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.von Muhlinen N, et al. LC3C, Bound Selectively by a Noncanonical LIR Motif in NDP52, Is Required for Antibacterial Autophagy. Mol. Cell. 2012;48:329–342. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.08.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wild P, McEwan DG, Dikic I. The LC3 interactome at a glance. J. Cell Sci. 2014;127:3–9. doi: 10.1242/jcs.140426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lamb CA, Yoshimori T, Tooze SA. The autophagosome: origins unknown, biogenesis complex. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2013;14:759–774. doi: 10.1038/nrm3696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fogel AI, et al. Role of membrane association and Atg14-dependent phosphorylation in beclin-1-mediated autophagy. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2013;33:3675–3688. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00079-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Koyama-Honda I, Itakura E, Fujiwara TK, Mizushima N. Temporal analysis of recruitment of mammalian ATG proteins to the autophagosome formation site. Autophagy. 2013;9:1491–1499. doi: 10.4161/auto.25529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim J, Kundu M, Viollet B, Guan KL. AMPK and mTOR regulate autophagy through direct phosphorylation of Ulk1. Nat. Cell Biol. 2011;13:132–141. doi: 10.1038/ncb2152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Itakura E, Kishi-Itakura C, Koyama-Honda I, Mizushima N. Structures containing Atg9A and the ULK1 complex independently target depolarized mitochondria at initial stages of Parkin-mediated mitophagy. J. Cell Sci. 2012;125:1488–1499. doi: 10.1242/jcs.094110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nezich CL, Wang C, Fogel AI, Youle Richard J. MiT/TFE transcription factors are activated during mitophagy downstream of Parkin and Atg5. J. Cell Biol. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201501002. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Santel A, et al. Mitofusin-1 protein is a generally expressed mediator of mitochondrial fusion in mammalian cells. J. Cell Sci. 2003;116:2763–2774. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huang P, et al. Heritable gene targeting in zebrafish using customized TALENs. Nat. Biotech. 2011;29:699–700. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hasson SA, et al. High-content genome-wide RNAi screens identify regulators of parkin upstream of mitophagy. Nature. 2013;504:291–295. doi: 10.1038/nature12748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Miller JC, et al. A TALE nuclease architecture for efficient genome editing. Nat. Biotech. 2011;29:143–148. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mali P, et al. RNA-guided human genome engineering via Cas9. Science. 2013;339:823–826. doi: 10.1126/science.1232033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lazarou M, Jin SM, Kane LA, Youle RJ. Role of PINK1 binding to the TOM complex and alternate intracellular membranes in recruitment and activation of the E3 ligase Parkin. Dev. Cell. 2012;22:320–333. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Katayama H, Kogure T, Mizushima N, Yoshimori T, Miyawaki A. A sensitive and quantitative technique for detecting autophagic events based on lysosomal delivery. Chem. & Biol. 2011;18:1042–1052. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2011.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.