Abstract

Empathy is a basic psychological process that involves the development of synchrony in dyads. It is also a foundational ingredient in specific, evidence-based behavioral treatments like motivational interviewing (MI). Ratings of therapist empathy typically rely on a gestalt, “felt sense” of therapist understanding and the presence of specific verbal behaviors like reflective listening. These ratings do not provide a direct test of psychological processes like behavioral synchrony that are theorized to be an important component of empathy in psychotherapy. To explore a new objective indicator of empathy, we hypothesized that synchrony in language style (i.e., matching how statements are phrased) between client and therapists would predict gestalt ratings of empathy over and above the contribution of reflections. We analyzed 122 MI transcripts with high and low empathy ratings based on the Motivational Interviewing Treatment Integrity (MITI) global rating scale. Linguistic inquiry and word count was used to estimate language style synchrony (LSS) of adjacent client and therapist talk turns. High empathy sessions showed greater LSS across 11 language style categories compared to low empathy sessions (p < .01), and overall, average LSS was notably higher in high empathy vs. low empathy sessions (d = 0.62). Regression analyses showed that LSS was predictive of empathy ratings over and above reflection counts; a 1 SD increase in LSS is associated with 2.4 times increase in the odds of a high empathy rating, controlling for therapist reflections (odds ratio = 2.4, 95% CI: 1.36, 4.24, p < .01). These findings suggest empathy ratings are related to synchrony in language style, over and above synchrony of content as measured by therapist reflections. Novel indicators of therapist empathy may have implications for the study of MI process as well as the training of therapists.

Keywords: empathy, motivational interviewing, synchrony, linguistic inquiry word count, language style, motivational interviewing treatment integrity

Introduction

Empathy, the ability to understand and experience the feelings of another person, is a key interpersonal process in psychotherapy broadly and significantly correlated with treatment outcomes (r = .31; Elliot, Bohart, Watson & Greenberg, 2011; Flückiger, Del Re, Wampold, Symonds, & Horvath, 2012; Valle, 1981) and specifically within Motivational Interviewing (MI; Moyers & Miller, 2013; Miller & Rollnick, 2013). MI is a client-centered, empathic and collaborative counseling style that attends to the language of change and is designed to strengthen personal motivation for, and commitment to, a specific goal (Miller & Rollnick, 2013). MI was developed to help clients prepare for changing addictive behaviors like drug and alcohol abuse (Miller & Rollnick, 1991, 2002) and has been shown to be effective to reduce other harmful behaviors including tobacco, drugs, alcohol, gambling, treatment engagement, and for promoting health behaviors such as exercise, diet, and safe sex (Lundahl, Kunz, Brownell, Tollefson, & Burke, 2010).

As the basic efficacy and effectiveness of MI has been established, research has increasingly focused on how MI works (Magill, Gaume, Apodaca, Walthers, Mastroleo, Borsai, Longabaugh, 2014). The first principle of MI is to express empathy and understanding through reflective listening (Miller & Rollnick, 1991, 2002, 2013). In MI, empathy is defined as “a specifiable and learnable skill for understanding another’s meaning through the use of reflective listening. It requires sharp attention to each new client statement and continual generation of hypotheses as to the underlying meaning” (Miller & Rollnick, 1991, p. 20). High ratings of therapist empathy are independently related to improved client outcomes such as reduced drinking (Gaume, Gmel, Faouzi, & Daeppen, 2008), drug use (McCambridge, Day, Thomas, & Strang, 2011), and other risk-behaviors (Pollak et al., 2011; Schwartz et al., 2007), as well as increased treatment engagement (Boardman, Catley, Grobe, Little, & Ahluwalia, 2006) and change talk preceding behavior change (Miller, Benefield, & Tonigan, 1993; Miller & Rose, 2009; Moyers & Miller, 2013).

Empathy in Motivational Interviewing

Given the emphasis on reflective listening in MI, fidelity measures include two types of therapist reflections: simple reflections (when the therapist repeats more or less verbatim what the client said) and complex reflections (when the therapist reflects deep understanding by going beyond what is explicitly stated; Moyers, Martin, Manuel, Miller & Ernst, 2007, 2010). The clinical theory underlying reflections has also been supported in the empirical literature. Therapists who use more reflections than questions are more likely to be rated as exhibiting high MI spirit and empathy (McCambridge et al., 2011). One study found that utilization of reflective statements, more than all other MI skills, resulted in patients feeling high autonomy support, and independent observers rated those clinicians as more empathic (Pollak et al., 2011).

Though reflections capture one aspect of therapist empathy, MI theorists agree that empathy is more than reflective techniques focused on the content of the client’s words. To capture the gestalt or felt-sense of empathy, MI fidelity measures like the Motivational Treatment Integrity Scale (MITI; Moyers et al., 2007, 2010) include a global rating of empathy encompassing the therapist’s behavior across the entire session. Global therapist empathy on the MITI incorporates an interest and attention to the client’s worldview, active and accurate understanding of the client’s perspective, and evidence of deep understanding of the client beyond what has been explicitly stated (Moyers et al., 2007, 2010). Reflective listening is an important part of this characteristic, but the global rating of empathy is intended to capture all efforts that the clinician makes to understand the client’s perspective and convey that understanding to the client.

Both MI theory and fidelity systems like the MITI are clear that empathy is a core therapeutic process that is comprised in part of reflective listening but also more than reflections; however, the specific linguistic aspects of empathy in MI over and above the contribution of reflections are presently unclear. Are there additional linguistic indicators of empathy beyond reflections or is global empathy more of a gestalt felt-sense that requires human judgment?

Empathy and Synchrony in General Psychotherapy

In basic psychological science, empathy is commonly conceptualized as a form of behavioral synchrony (see the Perception-Action Model; Preston & De Waal, 2002). Behavioral synchrony has been defined as “degree to which the behaviors in an interaction are nonrandom, patterned, or synchronized in both timing and form” (Bernieri & Rosenthal, 1991, p. 403). Theories like the Perception Action Model suggest that empathy is the process by which perception of a state in a person activates a representation of that state in the perceiver. There is consistent evidence that behavioral synchrony develops as two individuals interact over time. In addition, synchrony is related to ratings of empathy and other measures of the quality of the relationship between members of a dyad (Chartrand & Bargh, 1999; Chartrand & van Baaren, 2009; see also communication accommodation theory; Giles & Ogay, 2007).

There is also evidence for the development of synchrony between patients and therapists in psychotherapy. Specific findings include synchrony in body movement (Ramseyer & Tschacher, 2011), vocal prosody (e.g., pitch, intonation, accent, rhythm and loudness, use of pauses; Couper-Kuhlen, 2012; Weiste & Peräkylä, 2013, 2014), as well as physiological synchrony such as changes in skin-conductance (Marci et al., 2007; see also early studies on heart-rate, Di Mascio, 1955; and emotional reactivity, Lacey, 1959). In general, these studies have shown that greater synchrony is correlated with better ratings of therapist empathy and other measures of the therapeutic relationship, and treatment outcome (see Reich et al., 2014 for an exception). Specific to MI, the correlation of vocal tone synchrony between standardized patients and therapists was twice as high in session with high empathy ratings (r = .80) as compared to low (r = .36; Imel et al., 2014).

Measuring Empathy and Synchrony in Relation to the Words Said in Therapy

Examples of synchrony that involve vocal tone, skin conductance, and non-verbal behavior, do not capture what clients and therapists actually say to each other (i.e., the words). There is evidence that language defined as sets of words that affect how things are said (e.g., prepositions, pronouns) rather than what is said (e.g., nouns, adjectives) reflects relational information that may be important for understanding empathy in the client-therapist dyad. For example, the use of language style words such as pronouns has been found to be related to measures of relationship satisfaction and distress in couples (Williams-Baucom, Atkins, Sevier, Eldridge, & Christensen, 2010).

In studies of social interactions in laboratory and naturalistic settings, there is evidence for language style synchrony occurring to a greater degree in closer relationships (Ireland & Pennebaker, 2010; Niederhoffer & Pennebaker, 2002). In these studies, using the Linguistic Inquiry Word Count (LIWC; Pennebaker, Booth, & Francis, 2007) software, Ireland and Pennebaker (2010) identified nine language style categories (e.g., personal pronouns, articles, negations, conjunctions) and developed a synchrony index that they called language style matching. They found that persons who were more socially attuned, less neurotic, and who identified as colleagues, friends or as part of the same social group, were more likely to synchronize in language style. To date, there have been no clinical studies of language style synchrony.

Current Study

In the present research, we examined if synchrony in language style predicts observer ratings of empathy above and beyond what is captured by counts of therapist reflections. Whereas reflections in MI should primarily capture therapist attempts to understand the content of what is said or meant, synchrony in stylistic dimensions of language (i.e., how content is expressed or phrased) may also provide important information about empathy. Accordingly, it may be that synchrony in language style between client and therapist is an objective indicator of empathy in MI, in addition to use of reflections. We hypothesized that high empathy sessions would demonstrate greater language style synchrony with clients relative to low empathy sessions. Moreover, to assess whether this may simply be a proxy for reflections, we hypothesized that synchrony in language style would be predictive of empathy over and above counts of simple and complex reflections.

Method

Data Source

Data came from an 8-site MI training study, using therapists from National Institute of Drug Abuse (NIDA) affiliated community substance abuse treatment facilities in the state of Washington. Two methods of therapist training were compared. The therapist’s MI fidelity was examined using both real and standardized patients (for details of original trial see (Baer et al., 2009; Imel et al., 2014). Present analyses focused on sessions with standardized patients (SPs) to control for patient variability (i.e., with real patients, therapist differences may reflect patient case-load heterogeneity).

Selected Sessions

The data included digital audio and observer ratings of empathy from 122 selected MI sessions using SPs; this was 25% of the total SP sessions. Sessions were purposefully selected for high (n = 77) and low (n = 45) empathy ratings (see details provided below). The 122 sessions represented 122 therapists, 65% of the therapists in the original study. Therapists were 81% female, and 83% Caucasian, 12% African American, 6% Native American, 4% Hispanic/Latino, 3% Asian, and 2% Pacific Islander. Mean age was 46.9 years (Standard deviation (SD) = 10.7), and mean length of experience in clinical service provision was 9.4 years (SD = 8.2).

Standardized Patients

Therapists conducted MI interviews with one of three SPs who portrayed a recently referred client with a substance use problem and characteristics common for agency clientele. SPs were trained to provide realistic clinical vignettes and to respond flexibly to therapists during sessions. SP training was directed by study investigators and involved considerable role-play practice in which SPs were provided feedback on authenticity of their performances. Therapists were aware that SPs were confederates, but therapists were unaware of study hypotheses (e.g., that there were two types of training being compared). The SPs were similarly represented across the high and low empathy rating sessions (SPs 1–3 were in 29.9, 20.7, and 49.4% of high empathy sessions and 35.6, 15.6, and 48.9% of low empathy sessions, respectively). Note that this variability in empathy by SP was a natural result of their interactions with different therapists. SPs had no specific instructions relative to empathy (or other dimensions of MI fidelity), and empathy ratings were not different across the three SPs (F(2,119)=0.087, p=0.91).

Measures

Motivational Interviewing Treatment Integrity 3.0 (MITI 3.0; Moyers, Martin, Manuel, Miller & Ernst, 2007)

High and low empathy sessions were classified based on the gestalt global empathy rating from the MITI. The MITI rating system is the most widely used measure of therapist fidelity to MI (e.g., a recent meta-analysis of MI training studies found that 85.7% of studies used the MITI or a more in-depth version of the scale; Schwalbe, Oh, & Zweben, 2014). Raters were trained and supervised in the MITI and blind to assessment timing and practitioner identifiers. The inter-rater reliability of empathy was acceptable (Intraclass correlation = 0.60) according to widely-used standards (Cicchetti, 1994). The large group of community-based therapists received a broad range of empathy scores, spanning the full range of the scale (1 to 7). In the current set of 122 sessions, we defined high empathy sessions with an empathy score of at least 4.5 and low empathy sessions with a score of at most 3.5.1 Scores for high empathy sessions ranged 4.5 to 7 (mean (M) = 5.9, SD = 0.62) while scores for low empathy sessions ranged 1 to 3.5 (M = 2.2, SD = 0.54).2 Complex and simple reflections were measured as behavior counts, which correspond roughly to the number of utterances (i.e., complete thought units) identified as either complex or simple reflections. Sessions were 20 minutes in length and were coded in their entirety.

LIWC (Pennebaker et al., 2007)

LIWC software was used to quantify the semantic content of MI transcripts. LIWC was initially developed to identify words along basic emotional and cognitive dimensions common in social, health, and personality psychology (Pennebaker, 1993). For all words in a given text, the program reports proportions of words in 64 nonexclusive categories organized under four main themes: linguistic processes, psychological processes, personal concerns, and spoken categories. Current analyses applied LIWC to each MI session (separately by speaker) as well as individual talk turns. Present analyses used 11 language style categories studied previously (Ireland & Pennebaker, 2010; Ireland et al., 2011). 3

Language Style Synchrony

We adopted a language style synchrony (LSS) measure, the cohesion statistic, developed by Danescu-Niculescu, Gamon, and Dumais (2011) to measure LSS between therapist and client. For a given LIWC category and MI session, LSS was defined as the occurrence of both therapist and patient use of the LIWC category in adjacent talk turn pairs, averaged over all talk turns. Each pair of talk turns includes a single talk turn from a therapist and a single talk turn from a patient. This measure takes values between zero and one, where larger values indicate greater co-occurrence of an LIWC category across adjacent client and therapist talk turns and hence reflects greater LSS. More generally, it is the proportion of total talk-turns sharing a given indicator of language style. As a result, LSS is fundamentally a dyadic index; it measures the similarity of particular types of word usage in a dialogue, but cannot assign the matching to a particular source (in this case the therapist or client).

Ireland and Pennebaker (2010) proposed another measure of LSS, the language style matching index, based on entire documents (e.g., letters); however in MI sessions, there are many conversational turns within a single session, so treating sessions as documents ignores the temporal sequence in conversation. Because Danescu-Niculescu-Mizil et al. (2011) developed their measure for conversational data we chose to apply their methods in our analyses.

Statistical Analyses

Hypothesis 1

Sessions with a high empathy rating were hypothesized to have greater language style synchrony in the 11 language style categories compared to sessions with a low empathy rating. To examine this we performed a multivariate test of all 11 language style categories by empathy status (high versus low) via a 2-sample Hotelling T2 test. To further investigate which dimensions, or LIWC categories, of language style differed between the high and low empathy sessions, the omnibus comparison was followed by individual comparisons of LSS by empathy status using two-sample t-tests for each of the 11 categories.

Hypothesis 2

In addition, LSS was hypothesized to predict empathy over and above measures of reflections. This hypothesis was tested via two, nested logistic regression models with empathy category as the outcome. The first model included simple and complex reflection counts from the MITI as two covariates, and the second model included standardized average synchrony over the 11 language style categories as an additional covariate.3 We report model estimates of the odds ratios (ORs) comparing high to low empathy groups, with robust 95% confidence intervals.

Results

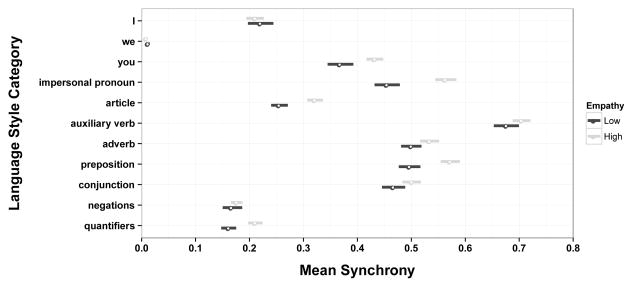

Across all 122 MI sessions there were 362,289 words, and 95.4% of the words were recognized and categorized by LIWC. The mean estimated LSS for the 11 categories of interest among all sessions ranged .01 to .69 (i.e., 1% to 69% of talk turns exhibited synchrony across the various categories). Average synchrony for each language style category by empathy group is shown in Figure 1. Across categories the difference in estimated synchrony within the high and low empathy therapists ranged −.01 to .11 (M = .04, SD = .04). Overall, average LSS was notably higher in high empathy vs. low empathy sessions (d = 0.62).

Figure 1.

Average language style synchrony between low and high empathy sessions (N = 122) across 11 language style categories. Synchrony is the sum of consecutive, pairs of talk turns sharing the given LIWC category, divided by the total number of talk turns. It is the proportion of total talk turns demonstrating synchrony.

Our first hypothesis focused on LSS in relationship to observer-rated empathy. An initial multivariate test showed that the joint distribution of synchrony for all 11 language style categories was significantly higher for sessions with high empathy ratings based on Hotelling T2 (F(10, 111) = 4.9, p < .01). Pairwise comparisons via 2-sample t-tests suggested that, on average, sessions with a high empathy rating have higher language style synchrony compared to sessions with a low empathy rating in second-person pronouns, impersonal pronouns, articles, prepositions and quantifiers (p < .002). As seen in Figure 1, in the remaining categories (first person pronouns—singular and plural, auxiliary verbs, adverbs, conjunctions, and negations) there was higher synchrony among high empathy sessions, but the mean differences were not statistically significant. Table 1 summarizes the pairwise comparison results.

Table 1.

Means and Differences in Means for LIWC Categories by Session Empathy (High vs. Low)

| category | Mhigh | Mlow | d | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | 0.21 | 0.22 | −0.01 | −0.05 | 0.03 |

| we | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.00 | −0.01 | 0.00 |

| you | 0.43 | 0.37 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.11 |

| impersonal pronoun | 0.56 | 0.46 | 0.11 | 0.07 | 0.15 |

| article | 0.32 | 0.26 | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.10 |

| auxiliary verb | 0.71 | 0.68 | 0.03 | −0.01 | 0.07 |

| adverb | 0.53 | 0.50 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.07 |

| preposition | 0.57 | 0.50 | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.11 |

| conjunction | 0.50 | 0.47 | 0.03 | −0.01 | 0.07 |

| negations | 0.18 | 0.17 | 0.01 | −0.02 | 0.04 |

| quantifiers | 0.21 | 0.16 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.08 |

Note. Mhigh and Mlow = means for high and low empathy, respectively. d = standardized mean difference, and 95% bootstrapped confidence intervals.

Our second hypothesis considered whether LSS is simply capturing therapist use of simple and complex reflections, or a separate linguistic component of the gestalt rating of empathy. Simple reflection counts ranged 0 to 19 (M = 7.5/4.6 for high/low empathy, respectively) and complex reflection counts ranged 0 to 31 (M = 10.0/2.6 for high/low empathy, respectively). Including average LSS significantly improved the fit of the model to the data, relative to the model containing simple and complex reflection counts (χ2 (1) = 9.054, p = .002). Interpreting the association of LSS with empathy, a 1 SD increase in LSS is associated with 2.4 times increase in the odds of a high empathy rating, controlling for therapist reflections (odds ratio = 2.4, 95% CI: 1.36, 4.24, p < .01). Among otherwise similar sessions, an additional simple reflection increases the odds of a high empathy rating by 25% (95% CI [0.98,1.60], p = .072), and an additional complex reflection increases the odds by 89% (95% CI [1.41,1.53], p = .000). Table 2 summarizes the nested logistic regression model results.

Table 2.

Logistic Regression Results Predicting Empathy with and without LSS

| OR (95% CI)

|

||

|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |

|

| ||

| simple reflections | 1.15 (0.94, 1.42) | 1.25 (0.98, 1.60) |

| complex reflections | 1.82 (1.42, 2.35) | 1.89 (1.41, 2.53) |

| (standardized) average LSS | 2.40 (1.36, 4.24) | |

Note. Model 1 is the model of empathy (high vs. low) on simple and complex reflections; Model 2 additionally regresses on standardized mean LSS (LSS averaged over the 11 LS categories).

Finally, two sensitivity analyses were conducted. First, a sensitivity check was conducted for potential differences in therapist speech rate, which could in turn influence the total number of reflections in a given session. The total number of therapist words (from LIWC) was included as a covariate in our final model; it was not a significant covariate of empathy (p > .25), nor did it affect the association of LSS with empathy. Second, given that there were three SPs, we examined whether there were mean differences in LSS by SP. There were no mean differences between SPs in LSS (F[2, 119] = 1.8, p = .17), suggesting that the observed LSS associations are functions of unique therapist and therapist by SP interactions, not SPs.

Discussion

What exactly are we rating on the global gestalt of therapist empathy on rating systems like the MITI? Prior research has shown that reflective listening is highly related to, and an important component of, therapist empathy. Our study examined hypotheses about how language style synchrony (i.e., how the client and therapist match the stylistic words they use to talk about the topic at hand) was a component of measures of gestalt empathy. In the present analyses, high empathy sessions had greater language style synchrony than sessions with low empathy ratings, and language style synchrony was not just a proxy measure of reflections but was predictive of empathy ratings over and above the presence of reflections. Both reflections and language style appear to measure a different, but not necessarily competing, aspect of the MITI gestalt ratings of empathy.

Following the literature from social psychology on mirroring (Chartrand & Bargh, 1999; Chartrand & van Baaren, 2009), our study seems to indicate that when the therapist is objectively perceived as empathic, there is more likely to be matching in the language style of therapists and clients. Interpersonal synchrony has been found to be an integral important component of human relations broadly (Strogatz, 2003) and recently has been objectively measured as related to empathy and connectedness in clinical and non-clinical interactions (Ireland & Pennebaker, 2010; Imel et al., 2014; Weiste & Peräkylä, 2014).

Unlike psychotherapy empathy rating systems that have historically rated only the therapist’s ability to express understanding (e.g., Moyers et al., 2010; Truax, 1972), our study revealed that one objective indicator of empathy in MI may be obtained from the synchronization of clients and therapists with each other. This understanding of empathy aligns with Rogers’s (1959) original discussions of empathy that focused on mutual identification and congruence; in fact, Rogers (1975) stated he was “appalled” by the reduction of empathic listening to measurements of therapist’s activities (e.g., counts of micro-skills like reflections) and that he “preferred to discuss the qualities of positive regard and therapeutic congruence, which together with empathy I hypothesized as promoting the therapeutic process” (p. 2). While measurements of matching pronouns and articles may seem even more micro-focused or abstract from clinical practice, language style synchrony may be tapping into a form of human inter-personal congruence that is not conscious but that naturally occurs when people feel aligned and understood in conversation.

The current study may also inform future directions aimed at developing objective ratings of therapist fidelity in MI for real world settings. First, the sample was pulled from community-based therapists working in outpatient substance abuse treatment facilities. All therapists were trained in MI but had a representative variable range of MI abilities and skills (e.g., from high to low empathy ratings). This is in contrast to many clinical trials with research-trained interventionists that have only high empathy and fidelity to MI. Thus, the conclusions of this study can be generalized to community-based therapist populations. Secondly, we have found an objective indicator of empathy that is predictive over and above reflections, but unlike reflections, measurements of language style synchrony can be conducted with computer software rather than with human raters. When applied to MI, objective indicators of empathy can assist increases in coding efficiency, which in turn can ease the use of coding for training and supervision of MI.

There were some limitations to the current study. The study from which the data was drawn was focused on methods of training therapists to do MI, and subsequently did not measure patient outcomes. We could not assess the impact of language style synchrony on patient outcomes. Another limitation is that the original measure of empathy had relatively low inter-rater reliability (ICC = .60), which is not uncommon among MITI studies. This is somewhat offset by the binning of empathy into high and low groups. The use of only SPs in this study could also be seen as a limitation, though as noted earlier, our focus is on studying therapist behavior, and SPs limit the variability in empathy ratings due to patients. In addition, the current study focused solely on lexical (i.e., words) synchrony, whereas other research has shown acoustic (Imel et al., 2014) and physiological (Marci et al., 2007) synchrony. Future research could examine the combination of multiple indicators of synchrony. Finally, the current data have a single session per therapist, but future research could explore how synchrony is clustered within therapists using data with multiple patients per therapist.

This study adds to the growing literature focused on specifying the component parts of empathy. Given its central role in clinical and counseling psychology, our study of empathy must move beyond the felt-sense and gestalt measurement that has heretofore been common. We hope that future research will build off the current findings to explore behavioral synchrony and its relationship to empathy across multiple domains of interpersonal functioning.

Highlights.

Therapist empathy ratings often rely on a gestalt felt-sense of understanding

Could a more objective indicator- synchrony in language style in therapy- predict ratings of empathy?

We analyzed motivational interviewing transcripts with high and low MITI empathy

High empathy therapists showed significantly greater language style synchrony

Language style synchrony was predictive of empathy ratings above therapist reflection counts

Acknowledgments

Funding for the preparation of this manuscript was provided by a University of Utah Seed Grant and was also supported by National Institute of Drug Abuse (NIDA) of the National Institutes of Health under award number R34/DA034860 and the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) under award number R01/AA018673. The original trial was supported by a grant from NIDA (R01/DA016360). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

There were three independent raters that made up the coding team for the study. Almost half of the included sessions were coded twice (n = 43, 48%) using the MITI. The remainder was coded once. For sessions that were coded twice, we used the mean of the ratings to classify high or low empathy.

The present study purposefully sampled the ends of empathy rating scale. Sessions with empathy scores of 1 or 7 were transcribed first, and then 2 and 6, and so on. Extreme groups sampling has tradeoffs (Preacher, Rucker, MacCallum, & Nicewander, 2005). It was used in the present study for cost and efficiency: Given the available budget, it was not possible to transcribe every session. However, the present approach would not be able to detect nonlinear associations between language style synchrony and empathy (should it exist), nor certain types of interactions.

Note that previous reports on language style matching used 9 LIWC categories, including the omnibus category of personal pronouns; for present analyses, we used the three individual personal pronoun categories, which yields 11 total categories.

Previously, language style similarity has been measured by averaging similarity scores over 9 language style categories (Pennebaker, Booth, & Francis, 2007). We adopted a similar approach when considering LSS jointly in a multivariate model of empathy.

There are no declarations of interest.

Disclosure Statement

None.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Baer JS, Wells EA, Rosengren DB, Hartzler B, Beadnell B, Dunn C. Agency context and tailored training in technology transfer: A pilot evaluation of motivational interviewing training for community counselors. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2009;37(2):191–202. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2009.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin SA, Wampold BE, Imel ZE. Untangling the alliance-outcome correlation: Exploring the relative importance of therapist and patient variability in the alliance. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75(6):842–852. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.6.842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernieri FJ, Rosenthal R. Interpersonal coordination: Behavior matching and interactional synchrony. In: Feldman RS, Rime B, editors. Fundamentals of nonverbal behavior. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press; 1991. pp. 401–432. [Google Scholar]

- Boardman T, Catley D, Grobe JE, Little TD, Ahluwalia JS. Using motivational interviewing with smokers: Do therapist behaviors relate to engagement and therapeutic alliance? Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2006;31(4):329–339. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chartrand TL, Bargh JA. The chameleon effect: The perception–behavior link and social interaction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1999;76(6):893–910. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.76.6.893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chartrand TL, van Baaren R. Human mimicry. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. 2009;41:219–274. [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti DV. Guidelines, criteria, and rules of thumb for evaluating normed and standardized assessment instruments in psychology. Psychological Assessment. 1994;6(4):284–290. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.6.4.284. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Couper-Kuhlen E. Exploring affiliation in the reception of conversational complaint stories. In: Peräkylä A, Sorjonen M-L, editors. Emotions in Interaction. New York: Oxford University Press; 2012. pp. 113–146. [Google Scholar]

- Danescu-Niculescu-Mizil C, Gamon M, Dumais S. Mark my words!: Linguistic style accommodation in social media. Paper presented at the 20th International Conference on World wide web; Hyderabad, India. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Di Mascio A, Boyd RW, Greenblatt M, Solomon HC. The psychiatric interview: A sociophysiologic study. Dis Nerv Syst. 1955;16:4–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Eggum ND. Empathic responding: Sympathy and personal distress. In: Decety J, Ickes W, editors. The social neuroscience of empathy. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 2009. pp. 71–83. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott R, Bohart AC, Watson JC, Greenberg LS. Empathy. Psychotherapy. 2011;48(1):43. doi: 10.1037/a0022187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flückiger C, Del Re AC, Wampold BE, Symonds D, Horvath AO. How central is the alliance in psychotherapy? A multilevel longitudinal meta-analysis. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2012;59(1):10. doi: 10.1037/a0025749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaume J, Gmel G, Faouzi M, Daeppen JB. Counsellor behaviours and patient language during brief motivational interventions: A sequential analysis of speech. Addiction. 2008;103(11):1793–1800. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02337.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giles H, Ogay T. Communication accommodation theory. In: Whaley BB, Samter W, editors. Explaining communication: Contemporary theories and exemplars. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2007. pp. 293–310. [Google Scholar]

- Iacoboni M. Imitation, empathy, and mirror neurons. Annual review of psychology. 2009;60:653–670. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imel ZE, Baldwin SA, Baer JS, Hartzler B, Dunn C, Rosengren DB, Atkins DC. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2014. Evaluating therapist adherence in motivational interviewing by comparing performance with standardized and real patients. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imel ZE, Barco JR, Brown HJ, Baucom BR, Baer JS, Kircher JC, Atkins DC. The association of therapist empathy and synchrony in vocally encoded arousal. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2013;61(1) doi: 10.1037/a0034943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ireland ME, Pennebaker JW. Language style matching in writing: synchrony in essays, correspondence, and poetry. Journal of personality and social psychology. 2010;99(3):549. doi: 10.1037/a0020386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ireland ME, Slatcher RB, Eastwick PW, Scissors LE, Finkel EJ, Pennebaker JW. Language style matching predicts relationship initiation and stability. Psychological Science. 2011;22(1):39–44. doi: 10.1177/0956797610392928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacey JI. Psychophysiological approaches to the evaluation of psychotherapeutic process and outcome. In: Parloff MB, editor. Research in Psychotherapy. Washington (DC): National Publishing Co; 1959. pp. 160–208. [Google Scholar]

- Marci CD, Ham J, Moran E, Orr SP. Physiologic correlates of perceived therapist empathy and social-emotional process during psychotherapy. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2007;195(2):103–111. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000253731.71025.fc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCambridge J, Day M, Thomas BA, Strang J. Fidelity to motivational interviewing and subsequent cannabis cessation among adolescents. Addictive Behaviors. 2011;36(7):749–754. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Benefield RG, Tonigan JS. Enhancing motivation for change in problem drinking: A controlled comparison of two therapist styles. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1993;61(3):455. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.61.3.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: Preparing people to change addictive behavior. New York, NY US: Guilford Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: Preparing people for change. 2. New York, NY US: Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: Helping people change. 3. New York, NY US: Guilford Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Rose GS. Toward a theory of motivational interviewing. American Psychologist. 2009;64(6):527. doi: 10.1037/a0016830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moyers TB, Martin T, Manuel JK, Miller WR, Ernst D. Revised Global Scales: Motivaitonal Interviewing Treatment Integrity 3.0 (MITI 3.0) 2007 http://casaa.unm.edu/download/miti3.pdf.

- Moyers TB, Martin T, Manuel JK, Miller WR, Ernst D. Revised global scales: Motivational interviewing treatment integrity 3.1.1 (MITI 3.1. 1) Albuquerque: Center on Alcoholism, Substance Abuse and Addictions, University of New Mexico; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Moyers TB, Martin T, Manuel JK, Miller WR, Ernst DB. Revised Global Scales: Motivational Interviewing Treatment Integrity 3.1.1 (MITI 3.1.1) 2010 Retrieved from http://casaa.unm.edu/download/MITI3_1.pdf.

- Moyers TB, Miller WR. Is low therapist empathy toxic? Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2013;27(3):878–884. doi: 10.1037/a0030274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niederhoffer KG, Pennebaker JW. Linguistic style matching in social interaction. Journal of Language and Social Psychology. 2002;21(4):337–360. [Google Scholar]

- Pennebaker JW. Putting stress into words: Health, linguistic, and therapeutic implications. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1993;31(6):539–548. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(93)90105-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennebaker JW, Booth RJ, Francis ME. Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count (LIWC): A computerized text analysis program. 2007 Retrieved from http://www.liwc.net/index.php.

- Pollak KI, Alexander SC, Tulsky JA, Lyna P, Coffman CJ, Dolor RJ, … Østbye T. Physician empathy and listening: Associations with patient satisfaction and autonomy. The Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine. 2011;24(6):665–672. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2011.06.110025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Rucker DD, MacCallum RC, Nicewander WA. Use of the extreme groups approach: A critical reexamination and new recommendations. Psychological Methods. 2005;10:178–192. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.10.2.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preston SD, De Waal F. Empathy: Its ultimate and proximate bases. Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 2002;25(01):1–20. doi: 10.1017/s0140525x02000018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramseyer F, Tschacher W. Nonverbal synchrony in psychotherapy: coordinated body movement reflects relationship quality and outcome. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2011;79(3):284–295. doi: 10.1037/a0023419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reich CM, Berman JS, Dale R, Levitt HM. Vocal synchrony in psychotherapy. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2014;33(5):481–494. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers CR. Empathic: An unappreciated way of being. The Counseling Psychologist. 1975;5(2):2–10. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers CR, Koch S. A theory of therapy, personality, and interpersonal relationships: As developed in the client-centered framework. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill New York; 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Schwalbe CS, Oh HY, Zweben A. Sustaining motivational interviewing: a meta-analysis of training studies. Addiction. 2014;109(8):1287–94. doi: 10.1111/add.12558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz RP, Hamre R, Dietz WH, Wasserman RC, Slora EJ, Myers EF, … Dumitru G. Office-based motivational interviewing to prevent childhood obesity: a feasibility study. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 2007;161(5):495–501. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.161.5.495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strogatz S. Sync: The emerging science of spontaneous order. New York, NY: Hyperion; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Truax CB. The meaning and reliability of accurate empathy ratings: A rejoinder. Psychological Bulletin. 1972;77(6):397–399. doi: 10.1037/h0032718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valle SK. Interpersonal functioning of alcoholism counselors and treatment outcome. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 1981;42(09):783–790. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1981.42.783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiste E, Peräkylä A. Prosody and empathic communication in psychotherapy interaction. Psychotherapy Research. 2014:1–15. doi: 10.1080/10503307.2013.879619. ahead-of-print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams-Baucom KJ, Atkins DC, Sevier M, Eldridge KA, Christensen A. “You” and “I” need to talk about “us”: Linguistic patterns in marital interactions. Personal Relationships. 2010;17(1):41–56. [Google Scholar]