Abstract

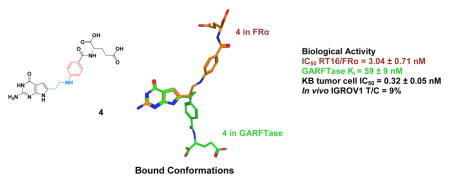

Targeted antifolates with heteroatom replacements of the carbon vicinal to the phenyl ring in 1 by N (4), O (8), or S (9), or with N-substituted formyl (5), acetyl (6), or trifluoroacetyl (7) moieties, were synthesized and tested for selective cellular uptake by folate receptor (FR) α and β or the proton-coupled folate transporter. Results show increased in vitro anti-proliferative activity toward engineered Chinese hamster ovary cells expressing FRs by 4–9 over the CH2 analog 1. Compounds 4–9 inhibited de novo purine biosynthesis and glycinamide ribonucleotide formyltransferase (GARFTase). X-ray crystal structures for 4 with FRα and GARFTase showed that the bound conformations of 4 required flexibility for attachment to both FRα and GARFTase. In mice bearing IGROV1 ovarian tumor xenografts, 4 was highly efficacious. Our results establish that heteroatom substitutions in the 3-atom bridge region of 6-substituted pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidines related to 1 provide targeted antifolates that warrant further evaluation as anticancer agents.

Graphical abstract

INTRODUCTION

Reduced folates are essential cofactors for biosynthesis of purines and pyrimidines.1 Since humans do not synthesize folate, it is necessary to obtain these cofactors from dietary sources. In mammals, three specialized systems exist that mediate membrane transport of folates and antifolates across biological membranes. These include the reduced folate carrier (RFC),2 folate receptor (FRs) α and β,3 and the proton-coupled folate transporter (PCFT).4, 5 RFC and PCFT are facilitative folate transporters, whereas FRs are glycosylphosphatidylinositol-linked proteins that mediate uptake of folates into cells by receptor-mediated endocytosis. RFC is ubiquitously expressed and is the major tissue transporter for folate cofactors.2 FRα and FRβ, as well as PCFT, exhibit narrower patterns of tissue expression and likely serve more specialized physiologic roles.3, 5 For instance, in the proximal tubules of the kidney, FRα contributes to reabsorption of folate from the urine.3 Notably, FRs in normal tissues are either inaccessible to circulating folates (e.g., FRα in renal tubules) or are non-functional (FRβ in thymus).3 PCFT is expressed in the upper gastrointestinal tract where it functions at acidic pH as the major intestinal transporter for absorption of dietary folates.6–8 Although appreciable PCFT can be detected in a number of other normal tissues (e.g., liver, kidney),5 given the requirement for an acidic pH (pH < 7, optimum at pH 5–5.5) for activity,4, 8 PCFT transport should be limited in most normal tissues.

Classical antifolates continue to serve a key role in the therapy of cancer, as well as for other diseases.9–13 Clinically important antifolates include methotrexate (MTX), pemetrexed (PMX), pralatrexate (PDX) and raltitrexed (RTX) (Figure 1). MTX and PDX are both inhibitors of dihydrofolate reductase.10 PMX and RTX inhibit thymidylate synthase as their primary intracellular target, although for PMX, secondary targets have been described, including 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide (AICA) ribonucleotide formyltransferase (AICARFTase) and glycinamide ribonucleotide (GAR) formyltransferase (GARFTase) in de novo purine nucleotide biosynthesis, and dihydrofolate reductase.14–16 Notably, all these compounds are excellent substrates for the RFC and, to varying degrees, are also substrates for FRs α and β and for PCFT.2, 5, 10 Transport by RFC confers limited tumor selectivity, as both tumors and normal tissues express this transporter.2 Interestingly, a substantial cohort of solid tumors (e.g., ovarian, non-small cell lung cancer) also expresses PCFT, often in concert with FRα.17, 18,19 In tumors (unlike normal tissues), FRα is accessible to the circulation, thus facilitating tumor targeting via this mechanism.20, 21 FRβ is expressed in hematologic malignancies such as acute myeloid leukemia3 and in white blood cells of the myeloid lineage,3 including tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs).22 PCFT is active at the acidic pHs typically associated with the tumor microenvironment which confers an additional element of tumor selectivity.5

Figure 1.

Structures of classic antifolate drugs, including methotrexate (MTX), pemetrexed (PMX), pralatrexate (PDX), and raltitrexed (RTX).

In response to the patterns of expression and function of FRs and PCFT in tumors and normal tissues, new cytotoxic agents are being developed for selective tumor targeting by virtue of their specificities for FRs and/or PCFT. FRβ-positive TAMs may play an important role in the tumor microenvironment in relation to tumor metastasis and angiogenesis by releasing proangiogenic factors (e.g., vascular endothelial growth factor, matrix metalloproteinase),23 suggesting that TAMs may constitute an additional potential therapeutic target in cancer for FRβ-targeted agents.22

Folate and pteroate conjugates have been used to deliver cytotoxic agents to FR-expressing tumors including ovarian cancer and non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC).21, 24, 25 For example, a folic acid-vindesine conjugate (vintafolide) was developed which is internalized by FRs, then cleaved in endosomes to release the cytotoxic vinca alkaloid.24, 25 Based on its success in a randomized Phase II clinical trial with platinum resistant ovarian cancer,26 vintafolide was advanced to a Phase III clinical trial. More recently, a folic acid-tubulysin conjugate,25, 27 was introduced into Phase I clinical trials. N-[4-[2-propyn-1-yl[(6S)-4,6,7,8-tetrahydro-2-(hydroxymethyl)-4-oxo-3H-cyclopenta[g]quinazolin-6-yl]amino]benzoyl]-L-γ-glutamyl-D-glutamic acid (ONX0801) is a small molecule antifolate with selective substrate activity toward FRs over RFC that is an inhibitor of thymidylate synthase.28 This compound is currently being tested in a Phase I clinical trial.

We previously described novel 6-substituted pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine benzoyl antifolates with selective cellular uptake by FRs and/or PCFT over RFC, resulting in potent inhibitory activity toward human tumor cells.18, 29–35 The most active analog of this series, 1, included a 3 carbon bridge (Figure 2) and showed high level activity toward KB human tumors (IC50 = 1.7 nM)29 expressing FRα and PCFT. Compound 2 has a 4-carbon bridge and showed a better selectivity than 1 for both FRα and PCFT over RFC. An analog of compound 1 with a side-chain thienoyl-for-benzoyl replacement (compound 3) (Figure 2) showed even greater FR- and PCFT-targeted activity.31 Although 1 and 3 were not effective substrates for RFC, an apparent non-mediated uptake process, as reflected in growth inhibition of both RFC and transport-null cells, was detected.29, 31 Compounds 1, 2 and 3 were identified as potent inhibitors of cellular GARFTase and de novo purine nucleotide biosynthesis.29, 31 Notably, these compounds were entirely unique from previously reported GARFTase inhibitors including lometrexol [(6R)5,10-dideazatetrahydrofolate; LMTX],36 (2S)-2-((5-(2-((6R)-2-amino-4-oxo-5,6,7,8-tetrahydro-1H-pyrido[ 2,3-d]pyrimidin-6-yl)ethyl)thiophene-2-carbonyl)amino) pentanedioic acid (LY309887),36 and (2S)-2-((5-(2-((6S)-2-amino-4-oxo-1,6,7,8-tetrahydropyrimido[5,4-b][1,4]thiazin-6-yl)ethyl) thiophene-2-carbonyl)amino) pentanedioic acid (AG2034),37 as all these latter antifolates are excellent substrates for RFC. In Phase I clinical trials with these earlier antifolates, toxicities were dose-limiting,38–40 likely due at least in part to their cellular uptake by RFC and their metabolism to polyglutamates in normal tissues.

Figure 2.

Structures of 6-pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine antifolates, 1, 2 and 3.

The natural substrate for GARFTase, N10-formyl tetrahydrofolate (10-CHOTHF, Figure 3), is a 6-substituted pteridine with a –CH2-N-two-atom bridge. The N10 is substituted with a formyl moiety which forms a hydroxylated, tetrahedral intermediate prior to transfer of the one-carbon group.41 Thus, replacement of the C10-benzylic CH2 of the 6-substituted pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine 1 with a NH, N-COCH3, N-CHO, and N-COCF3 [4, 5, 6, and 7, respectively; Figure 4] would afford “mimics” of the natural substrate with a three-atom rather than two-atom bridge. We hypothesized that these 6-substituted three-atom bridged NH and N-substituted analogs would function as potent inhibitors of human GARFTase rather than as substrates. It was further anticipated that these N10-H (4) and N10-substituted compounds (5–7) would provide additional hydrogen bonding with the target enzyme GARFTase that would be absent with the threecarbon bridge analog 1.

Figure 3.

Structure of N10-formyl tetrahydrofolate.

Figure 4.

Structures of 6-substituted pyrrolo[2,-3-d]pyrimidine antifolates with heteroatom bridge substitutions.

We previously reported that in the carbon-bridged analogs the length of the side-chain plays an important role in determining potency and transport selectivity18, 29 such that the most transport selective analogs have a four-carbon bridge (e.g., 2) and the most potent GARFTase and tumor inhibitors have a three carbon bridge (e.g., 1). Thus, it was of interest to compare the effects of replacing the benzylic CH2 of 1 with NH (compound 4), O (compound 8) and S (compound 9) (Figures 4 and 5). The C-S bond length is 1.81 Å, compared to the C-C bond length of 1.54 Å.42 Replacing the benzylic CH2 of the three-atom chain of 1 with larger sulfur would afford a chain length between those for the 3-carbon and 4-carbon bridges of 1 and 2, respectively. In addition to the increased bond length, the C-S-C bond angle is 99° compared to a C-C-C bond angle of 109° (Figure 5).42 This provides a slightly different conformational orientation of the benzene ring, and hence L-glutamate orientation. Similarly, replacement of the benzylic CH2 with NH or an O would afford subtle variations in bond length (C-O = 1.43 Å) and bond angle (C-O-C = 111°, Figure 5). Collectively, these structural alterations could impact transport selectivity, as well as GARFTase inhibition and antitumor efficacy.

Figure 5. Distances and bond angle variations predicted by the nature of the bridge at the benzylic position (X).

Bond angles for X = CH2, O and S obtained from literature.42 Distances and angles for X = NH were measured using energy-minimized conformations of compounds with MOE 2014.09.43

In this study, we report the synthesis and biological activities of analogs of 1 with isosteric heteroatom replacements, including S (9), O (8) and N (4) vicinal to the side chain phenyl ring, along with additional N-substituted analogs including formyl (5), acetyl (6) and trifluoroacetyl (7) moieties.

MOLECULAR MODELING

To provide a rationale for our proposed analogs, molecular modeling studies were initially carried out using our X-ray crystal structure of human GARFTase bound to 3 (PDB: 4ZYW).18 Figure 6A shows the docked pose of the lead compound 1 (green) in the GARFTase active site as a representative example of docking the target molecules. Compound 4 (orange) is also docked in Figure 6A. The pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine scaffold of 1 binds in the region occupied by the bicyclic scaffold of 3 in the GARFTase crystal structure (PDB: 4ZYW18, 3 not shown for clarity). Hydrogen bonds between the N1 nitrogen of 1 and the backbone of Leu899, 2-NH2 of 1 and the carbonyls of Glu948 and Leu899, N3 of 1 and the amide of Ala947, and 4-oxo of 1 and the amide of Asp951 stabilize the scaffold. Additionally, the N7-nitrogen of 1 forms a hydrogen bond with the carbonyl of Arg897. The pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine scaffold of 1 forms hydrophobic interactions with Leu892, Ile898, Leu899, and Val904, and the folate binding loop residues 948–951. The amide NH of the L-glutamate of 1 forms a hydrogen bond with the carbonyl of Met896. The L-glutamyl moiety of 1 is oriented similar to 3, with the α-carboxylate interacting with Arg897.

Figure 6. Molecular modeling studies with human GARFTase (PDB: 4ZYW).18.

(Panel A) Superimposition of docked poses of 1 (green) and 4 (orange) (Panel B) Docked pose of 7 (purple). In both panels, GAR is shown in pink.

The docked poses of 4 (Figure 6A, orange) and 7 (Figure 6B) retain the hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic interactions seen in the docked pose of the lead compound 1. In addition, the docked pose of 4 at the N10-H forms hydrogen bonds with the substrate GAR and with Asn913, His915 and Asp951 via a bridging water molecule (Figure 6A). Similar water molecules are seen in other reported X-ray crystal structures of GARFTase.18, 44 This suggests that 4 with the N10-H hydrogen bond would possibly bind better than 1 and 2 with C10-H. Docking scores of 4 (−56.31 kJ/mol) were better than those of 1 (−51.26 kJ/mol) and 2 (−52.57 kJ/mol). Similar interactions are predicted to occur between the heteroatom bridges of 8 (oxygen) and 9 (sulfur) and the conserved water molecule, with the heteroatoms functioning as hydrogen bond acceptors (not shown).

The N10-COCF3 moiety in 7 (Figure 6B) is oriented similar to the N10-H of 4, but binds deeper into the formyl transfer region that is occupied by the formyl group of the natural GARFTase substrate, 10-CHOTHF. The increased bulk at the N10-position of 7 displaces the water molecule involved in H-bonding with the N10-H of 4, and affords direct interaction between the trifluoromethyl of the NCOCF3 moiety of 7 and the terminal amine of substrate GAR. The docking score of 7 in GARFTase was −53.31 kJ/mol. Similar interactions involving the terminal amine of GAR are also observed with the carbonyl of the formyl group of 5 and the carbonyl group of the acetyl of 6 (not shown).

Figure 7 shows the results of molecular modeling studies in the folate binding cleft of FRα(PDB: 4LRH)45 for lead compounds 1 (panel A), 2 (panel B) and 4 (panel C). All three compounds display similar interactions in the pocket, maintaining important protein contacts between the bicyclic scaffolds and benzoyl glutamate tail, as also seen in the crystal structure ligand folic acid.45 In the docked pose of 4 (Figure 7C), the 2-NH2 of 4 interacts with Asp103 (81) (for FR, numbering is that of the full-length gene product with mature protein numbering in parentheses). The 4-oxo moiety forms hydrogen bonds with the side chain hydroxyl of Ser196 (174) and the side chain nitrogens of Arg125 (103) and His157 (135). The pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine scaffold is stacked between the side chains of Tyr82 (60) and Trp193 (171), similar to that seen with the pteroyl ring of folic acid in its bound conformation.45 The L-glutamate moiety of 4 is oriented similar to the corresponding L-glutamate in folic acid.45 The α-carboxylic acid of 4 forms a network of hydrogen bonds involving the backbone NH of Gly159 (137) and Trp160 (138), while the γ-carboxylic acid of 4 interacts with the amine of Lys158 (136) and the side chain NH of Trp124 (102). The bridge of 4 forms hydrophobic interactions with Tyr82 (60), Phe84 (62), Trp124 (102) and His157 (135).

Figure 7. Molecular modeling studies using the human FR.

αcrystal structure (PDB: 4LRH).45

Panel A, superimposition of the docked pose of 1 (green) with the crystal structure of folic acid (black). Panel B, superimposition of the docked pose of 2 (pink) with crystal structure of folic acid (black) (C) Docked pose of 4 (orange).

Comparing the docked poses of 1 (Figure 7A)and 2 (Figure 7B) with the crystal structure of folic acid in FRα45 indicates that the 3- and 4-atom bridges of 1 and 2 are accommodated within a similar space as the 2-atom bridge in folic acid. Since the bridge NH in folic acid does not form hydrogen bonds with the binding pocket, its replacement with an all-carbon bridge (1 and 2) could, perhaps, better utilize the hydrophobic nature of the pocket for binding interactions. Introduction of heteroatom bridges in the target compounds was not expected to affect FRαtransport capabilities of these compounds, reflected by their highly similar docked pose (e.g., compound 4, Figure 7C) compared to lead 1 and folic acid. The docking score of 4 was −43.87 kJ/mol, similar to the docked scores of 1 (−44.29 kJ/mol) and 2 (−46.99 kJ/mol).

CHEMISTRY

Compounds 10 and 11 (Scheme I) were subjected to Michael addition to afford the β-keto amine 12. Compound 12 was then selectively brominated at the α carbon under acidic conditions using 33% HBr in acetic acid/Br2 to give 13. Protection of the amine in 13 using trifluoroacetic anhydride and subsequent condensation with 2,6-diamino-3H-pyrimidin-4-one in DMF at room temperature for 3 days afforded the 2-amino-4-oxo-6-substituted-pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine 14. Hydrolysis of 14 afforded the corresponding free acid 15. Subsequent coupling with L-glutamate di-tert-butyl ester using 2-chloro-4,6-dimethoxy-1,3,5-triazine as the activating agent afforded the diester 16. Deprotection of the di-tert-butyl ester afforded the corresponding acid 4. Compound 4 was then reacted with formic acid and acetic anhydride, acetic anhydride or trifluoroacetic anhydride to afford target compounds 5, 6 and 7, respectively.

Scheme I. Reagents and conditions.

(a) Ethanol, reflux, 5 h, 59% ;(b) 33% HBr in CH3COOH, Br2, rt, 2.5 h, 33%; (c) (CF3CO)2O, rt, overnight, 76%; (d) 2,6-diaminopyrimidin-4(3H)-one, DMF, rt, 3 d, 25%; (e) 1N NaOH, rt, 10 h, 88%; (f) N-methylmorpholine, 2-chloro-4,6-methoxy-1,3,5-triazine, L-Glutamate di-tert-butyl, DMF, 12 h, 60%; (g) CF3COOH, CH2Cl2, rt, 2 h, 74%; (h) (CH3CO)2O, rt, 12 h, 47% or (CF3CO)2O, rt, 4 h, 76% or (CH3CO)2O, HCOOH, 1 h, reflux, 35%.

Carboxylic acid 19 (Scheme II) was obtained from β-propiolactone 17 and methyl 4-hydroxybenzoate 18 using NaOH at 50 °C for 30 min. The carboxylic acid 19 was then converted to the acid chloride and immediately reacted with diazomethane, followed by 48% HBr in water, to give the α-bromomethylketone 20. Condensation of 2,6-diamino-3H-pyrimidin-4-one with 20 in DMF at room temperature for 3 days afforded the 2-amino-4-oxo-6-substituted-pyrrolo[ 2,3-d]pyrimidine 21. Hydrolysis of 21 afforded the corresponding free acid 22. Subsequent coupling with the L-glutamate dimethyl ester using 2-chloro-4,6-dimethoxy-1,3,5-triazine as the activating agent afforded the diester 23. Saponification of the diester gave the target compound 8.

Scheme II. Reagents and conditions.

(a) NaOH, H2O, 30 min, 80 °C, 52%; (b) Oxalyl chloride, CH2Cl2, reflux, 1 h, 79%; (c) Diazomethane, (CH3CH2)2O, rt, 1h; (d) 48% HBr in water, 80 °C, 2 h, 94%; (e) 2,6-diaminopyrimidin-4(3H)-one, DMF, rt, 3 d, 31%; (f) 1N NaOH, rt, 12 h, 74%; (g) N-methylmorpholine 2-chloro-4, 6-methoxy-1,3,5-triarzine, L-glutamate dimethyl, DMF, 12 h, 42%; (h) 1N NaOH, rt, 4 h, 88%.

The 6-substituted pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine 27 (Scheme III) was synthesized by condensation of 2,6-diamino-4-oxopyrimidine 25 with ethyl 4-chloro-3-oxobutanoate 26. Reduction of the ester group of 27 to the alcohol 28 and subsequent mesylation of the alcohol gave 29. Nucleophilic displacement with 4-mercapto-benzoic acid methyl ester under basic conditions gave the thiophene-linked ester 30. Hydrolysis of the ester moiety of 30 to acid 31 and coupling with L-glutamate diethyl ester using 2-chloro-4,6-dimethoxy-1,3,5-triazine as the activating agent afforded the diester 32. Saponication of the diester moieties gave target 9.

Scheme III. Reagents and conditions.

(a) NaOAc, H2O, reflux, 18 h, 54%; (b) LiEt3BH, THF, 0 °C, 30 min, 75%; (c) CH3SO2Cl, DMF, Et3N, 0 °C, 2 h, 80%; (d) 4-mercapto-benzoic acid methyl ester, K2CO3, DMF, rt, 12 h, 37%; (e) 1N NaOH, MeOH, rt, 95–99%; (f) L-glutamic acid diethyl ester hydrochloride, N-methyl morpholine, 2-chloro-4,6-dimethoxy-1,3,5-triazine, DMF, rt, 6 h, 60%.

BIOLOGICAL EVALUATION AND DISCUSSION

Anti-proliferative effects of 6-substituted pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine benozyl analogs with heteroatom bridge substitutions in relation to mechanisms of folate transport

The goal of this study was to explore the impact of various isosteric heteroatom substitutions including N, O, and S (designated compounds 4, 8, and 9, respectively) at position 10 in the bridge region connecting the bicyclic scaffold and the phenyl ring of 6-pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine antifolates (Figure 4). Additional N-substituted analogs related to 4 with formyl (5), acetyl (6), and trifluoroacetyl (7) substitutions were also synthesized and tested.

As a primary screen of antiproliferative activities for these novel agents, we initially used a panel of isogenic Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) sublines individually expressing FRα (RT16 cells),29 FRβ (D4),29 RFC (PC43-10),46 or PCFT (R2/PCFT4)47. These engineered CHO cell lines were developed from RFC-, FR- and PCFT-null MTXRIIOuaR2-4 CHO cells48 (hereafter, referred to as R2) by stably transfecting the human transporters and have been documented for their transport characteristics.29, 46, 47, 49 To assess the inhibitory potentials of the 6-substituted pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine analogs (or classical antifolate inhibitors such as PMX, for comparison), the CHO sublines were cultured in the presence of a range of drug concentrations for up to 96 hours and cell viabilities were measured as a fluorescence read-out. IC50 values, corresponding to the drug concentrations that inhibit growth by 50%, were calculated. Results for the engineered CHO sublines were compared to those for R2 CHO cells.

The 6-substituted pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine analogs with heteroatom bridge replacements, 4 (N), 8 (O), and 9 (S), all showed potent growth inhibition toward FRα-expressing RT16 cells and toward FRβ-expressing D4 cells with IC50 values equal or less than those previously reported for 129, 49 (Table 1). The impacts of N-substitutions including formyl (5), acetyl (6) or trifluoroacetyl (7) on FR-targeted activity compared to N-unsubstituted 4 were modest. Notably, the N-heteroatom analogs including unsubstituted (4) and N-substituted (5 and 6) forms were significantly more potent toward D4 than toward RT16 cells (<0.003) (Table 1). While 7 was also more active toward D4 cells, the difference from RT16 was not statistically significant. These results suggest an increased FRβ selectivity over FRα for the N heteroatom series of 6- substituted pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine analogs.

Table 1. IC50s (in nM) for 6-substituted pyrrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine benzoyl antifolates with heteroatom replacements, and classical antifolates in RFC-, PCFT- and FR-expressing cell lines.

Proliferation assays were performed for CHO sublines engineered to express human RFC (PC43-10), FRa (RT16), FRβ (D4) or PCFT (R2/PCFT4), and transporter-null (R2) CHO cells,29, 46–48 and KB human tumor cells (express RFC, FRa, and PCFT). For the experiments measuring FR-mediated effects, assays were performed in the presence or absence of 200 nM folic acid (results are shown only for KB cells). Results are presented as IC50 values, corresponding to the concentrations that inhibit growth by 50% relative to cells incubated without drug. The data are mean values from 5–16 experiments (+/− standard errors in parentheses). Some of the data for 1, 2, 3, MTX, PDX, PMX and LMTX have been previously published.29–31, 34, 47, 49 Results are also summarized for KB cells for the protective effects of adenosine (60 μM), thymidine (10 μM), or 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide (320 μM). For compounds 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, and 9, folic acid and nucleoside/AICA protection results are shown in Figure 10. Methods are summarized in the Experimental Section. Undefined abbreviations: Ade, adenosine; AICA, 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide; FA, folic acid; ND, not determined; Thd, thymidine. *Significantly different from compound 4 with RT16 or KB cells, as appropriate (p<0.05); ϕθ¥, significantly different from RT16 with 4 (p=0.0006), 6 (p=0.0026), and 5 (p=0.0001)

| Antifolate | RFC | FRa | FRβ | PCFT | RFC/FRa/PCFT | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| PC43-10 | R2 | RT16 | D4 | R2/PCFT4 | R2 | KB | KB (+FA) | KB + Ade/Thd/AICA | |

|

| |||||||||

| 1 | 649(38) | >1000 | 4.1(1.6) | 5.6(1.2) | 23.0(3.3) | >1000 | 1.7(0.4) | >1000 | Ade/AICA |

| 2 | >1000 | >1000 | 6.3(1.6) | 10(2) | 213(28) | >1000 | 1.7(0.4) | >1000 | Ade/AICA |

| 3 | 101.0 (16.6) | 273.5 (49.1) | 0.31 (0.14) | 0.17 (0.03) | 3.34(0.26) | 288(12) | 0.26(0.03) | 101(7) | Ade/AICA |

| 4 | 510(90) | >1000 | 3.04 (0.71) | 0.62 (0.20)ϕ | 87.4(9.9) | >1000 | 0.32(0.05) | 666(46) | Ade/AICA |

| 5 | 642(239) | >1000 | 3.01 (0.57) | 0.53 (0.11)¥ | 88.5(13.4) | >1000 | 2.09(0.72)* | >1000 | Ade/AICA |

| 6 | 808(124) | >1000 | 4.87 (0.81) | 1.57 (0.53)θ | 81.7(91) | >1000 | 2.57(0.60)* | >1000 | Ade/AICA |

| 7 | 783(109) | >1000 | 1.08 (0.69) | 0.45 (0.11) | 109 (26) | >1000 | 0.56(0.05)* | 924(40) | Ade/AICA |

| 8 | 641(140) | 940(60) | 1.89 (0.85) | 2.59 (1.17) | 57.5(5.8) | >1000 | 0.34(0.05) | 704(73) | Ade/AICA |

| 9 | >1000 | >1000 | 0.51 (0.10)* | 0.34 (0.02) | 267(19) | >1000 | 1.66(0.26)* | >1000 | Ade/AICA |

| MTX | 12(1.1) | 114(31) | 114 (31) | 106 (11) | 121 (17) | >1000 | 6.00(0.60) | 20(2.4) | Thd/Ade |

| PMX | 138(13) | 42(9) | 42 (9) | 60 (8) | 13.2(2.4) | 974 (18) | 68(12) | 327(103) | Thd/Ade |

| RTX | 6.3(1.3) | 15(5) | 15 (5) | 22 (10) | 99.5(11.4) | >1000 | 5.90(2.20) | 22(5) | Thd |

| LMTX | 12(2.3) | 12(8) | 12 (8) | 2.6 (1.0) | 38.0(5.3) | >1000 | 1.20(0.60) | 31(7) | Ade/AICA |

With PCFT-expressing R2/PCFT4 CHO cells, anti-proliferative activities were reduced for 4 (N), 8 (O) and 9 (S), compared to that for compound 1 (Table 1). N-substitution of 4 (i.e., 5, 6, and 7) resulted in no significant increase in growth inhibition of R2/PCFT4 cells compared to the non-substituted compound (4).

Toward RFC-expressing PC43-10 cells, very minor inhibitory effects were detected for all the heteroatom compounds, with IC50s which were far in excess of the inhibition recorded for FRα-, FRβ- or PCFT-expressing CHO cells (Table 1). The modest inhibitions of the heteroatom analogs were likewise less than those previously reported toward PC43-10 cells for 129 or 331. Thus, the selectivity for this series (as reflected in the relative IC50s for FRα or FRβ versus RFC-expressing CHO cells) is greater than previously reported for compounds 1, 2 or 3.29, 31

The results with the engineered CHO sublines were generally recapitulated in KB human nasopharengeal carcinoma cells, which express FRα and PCFT along with RFC18, although there were some differences, with 4 and 8 showing potencies essentially equivalent to 3 in this tumor model (Table 1). In KB tumor cells, 4 was significantly more active than 5, 6, 7, and 9 (p<0.05), with the antiproliferative effects for the entire series substantially reversed in the presence of 200 nM folic acid. This is consistent with a FR-mediated cellular uptake process, although non-FR uptake (i.e., PCFT) manifested (as reflected by a lack of folic acid protection18) at higher concentrations of 4, 6, 7 and 8 (Figure 10 shows results for KB cells).

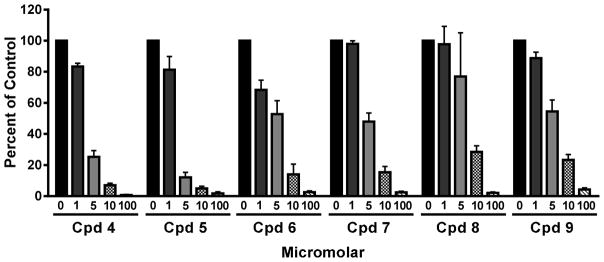

Figure 10. Growth inhibition of KB human tumor cells by 6-substituted pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine antifolates 1, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 and 9, and protective effects of excess folic acid, nucleosides, or 5- aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide (AICA).

KB cells were plated (4000 cells/well) in folate-free RPMI 1640 medium with 10% dialyzed FBS, antibiotics, L-glutamine, and 2 nM LCV with a range of drug concentrations, in presence of folic acid (200 nM), adenosine (60 μM), thymidine (10 μM), or AICA (320 μM). Cell proliferation was assayed with a fluorescence-based assay. Data are representative of at least triplicate experiments. These results are summarized in Table 1. The methods are described in the Experimental Section. Abbreviation: Cpd, compound.

The inhibitory potencies measured for the 6-substituted pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine heteroatom compounds 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, and 9 toward the engineered CHO and human tumor cell lines exceeded those for standard antifolates including MTX, PMX, RTX and LMTX (Table 1). Further, there was limited selectivity for FR and PCFT over RFC for the standard agents.

Transport characteristics of 6-substituted pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine benozyl analogs with heteroatom bridge substitutions

The growth inhibition data with the engineered CHO cell lines in Table 1 strongly imply that the heteroatom analogs 4–9 are internalized by FRα and FRβ, as well as by PCFT.

The binding affinity for folic acid, as reflected in the dissociation constant (Kd) value measured by isothermal calorimetry, was greater for FRα (Kd=0.01 nM) than for FRβ (Kd=2.7 nM).50 To determine relative binding affinities individually for FRα and FRβ compared to folic acid for this series, we incubated RT16 and D4 cells with [3H]folic acid at 4 °C in the presence of a range of concentrations of the unlabeled pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine antifolates 1 and 4–9 (0–1000 nM).

Controls for these experiments included a comparable concentration range of non-radioactive folic acid (positive control) and MTX (negative control). Relative binding affinities are reflected in the extents to which the analogs compete with [3H]folic acid for binding to FR, with FR-bound [3H]folic acid normalized to total cell proteins. Relative FR binding affinities were expressed as inverse molar ratios of the unlabeled compounds required to reduce the level of FR-bound [3H]folic acid by 50%, with the folic acid affinity assigned a value of 1.

In this assay, with both FRα- and FRβ-expressing cells, relative binding profiles for 4, 8, and 9 were similar and ~60–110% of the affinity for folic acid (Figure 8). These results indicate that heteroatom substitution for the benzylic CH2 in 1 preserves binding affinity for both FRα (RT16) and FRβ (D4). For FRα, the N-formyl-substituted 5 and the N-acetyl- and N-trifluoroacetyl-substituted 6 and 7, respectively, all showed binding that was substantially reduced (<15% of that for folic acid and for 4). A similar pattern was detected with FRβ-expressing D4 cells and 4, 5, 6, and 7, in spite of increased in vitro drug efficacies toward D4 over RT16 cells (Table 1). Thus, relative FR binding affinities were only partly reflected in the differences in in vitro drug efficacies toward RT16 or D4 cells (Table 1), suggesting that factors unrelated to FR binding are necessary to explain the differential drug sensitivities at low nanomolar or subnanomolar concentrations of these novel antifolates.

Figure 8. FRα and FRβ binding affinities for compounds 4.

–9, compared to folic acid, MTX and compound 1.

Results are shown for the relative binding affinities of the (anti)folates with FRα-expressing RT16 and FRβ-expressing D4 CHO cells. Relative binding affinities were determined over a range of (anti)folate concentrations and were calculated as the inverse molar ratios of the unlabeled ligands required to inhibit [3H]folic acid binding by 50%. By this definition, the relative affinity of folic acid is 1. Results are shown as mean values plus/minus standard errors from 3–4 experiments. Detailed experimental methods are provided in the Experimental Section. Abbreviation: FA, folic acid.

Since the 6-substituted pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine heteroatom compounds were transported by PCFT in R2/PCFT4 CHO cells (based on patterns of growth inhibition; Table 1), we determined relative binding affinities for this series compared to PMX in order to assess a possible basis for differences in relative PCFT-targeted activities. We compared the effects of the heteroatom compounds (at 1 or 10 μM) on PCFT-mediated transport of [3H]MTX (0.5 μM) over 5 min at pH 5.5 (the pH optimum of PCFT) and at pH 6.8 (approximating the pH of tumor microenvironment) 5 (Figure 9). Results were compared to those for PMX, among the best PCFT substrates,4, 5 and for PT523 (N(alpha)-(4-amino-4-deoxypteroyl)-N(delta)-hemiphthaloyl-L-ornithine), 30 an antifolate substrate for RFC with no significant transport by PCFT. At pH 5.5, PMX potently inhibited [3H]MTX uptake (≥90% at both 1 and 10 μM), whereas 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, and 9, like 1 were somewhat less inhibitory (80–90% inhibition at 10 μM and 30–60% inhibition at 1 μM). At pH 6.8, inhibitions for all compounds were decreased, although appreciable transport inhibitions (~40–60%) compared to controls were detected at 10 μM for compounds 1, 4, 7 and 8. Ki values were calculated from the extent of [3H]MTX transport inhibition at pH 5.5 over a range of drug concentrations by Dixon analysis (Table, Figure 9). Ki values ranged from ~7-fold (for 8) to ~18-fold (for 6) higher than for PMX. Thus, the patterns of growth inhibition toward PCFT-expressing R2/PCFT4 cells are only partially reflected in analog binding to PCFT.

Figure 9. Transport competition by 6-substituted pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine analogs for PCFT in R2/PCFT4.

Panels A and B: Data are shown for the inhibitory effects of the unlabeled ligands (1 or 10 nM) on [3H]MTX uptake (5 min) with human PCFT-expressing R2/PCFT4 CHO cells at pH 5.5 and pH 6.8. The extent of inhibition in this assay is a reflection of relative PCFT binding affinities for assorted antifolate substrates. Results are presented as average values plus/minus ranges for 2–4 experiments. Results are compared to those for normalized rates in the absence of any additions (“No additions”) and to PCFT-null R2 cells without additions. Panel C: In the table are shown Ki values for inhibition of [3H]MTX uptake at pH 5.5, as measured by Dixon analysis for 3–8 separate experiments. Experimental details are provided in the Experimental Section. Cpd, compound.

Identification of GARFTase as the intracellular enzyme target of 6-substituted pyrrolo [2,3-d]pyrimidine antifolates with heteroatom bridge substitutions

To identify the targeted pathway, we determined the effects of nucleoside additions on the growth inhibitory effects of compounds 4–9 toward KB tumor cells. The results are shown in Figure 10 and are summarized in Table 1. The antiproliferative effects of all compounds were abolished by adenosine (60 μM) but not by thymidine (10 μM), identifying de novo purine nucleotide rather than thymidylate biosynthesis as the targeted pathway, analogous to 1.29 Since AICA (320 μM), a precursor of AICA ribonucleotide (ZMP) which circumvents the step catalyzed by GARFTase (by providing downstream substrate for AICARFTase, the 2nd folate-dependent reaction) also protected (Figure 10), the likely enzyme target is GARFTase.

We used both in situ cell-based (in KB tumor cells) and in vitro GARFTase assays with recombinant GARFTase to confirm GARFTase as the enzyme target for our analogs. The former measures the generation of [14C]formyl GAR from [14C]glycine (and GAR) by GARFTase in KB cells treated with azaserine. In these experiments, we incubated KB cells with a range of concentrations of compounds 4–9 and [14C]glycine for 16 h, under conditions approximating those in our proliferation experiments (Table 1). Our results demonstrated dramatically decreased [14C]formyl GAR in cells in drug-treated cells, with nanomolar IC50 values approximating or slightly exceeding those for inhibition of cell proliferation (Figure 11).

Figure 11. In situ GARFTase assay in KB tumor cells treated with 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, and 9.

Inhibition of cellular GARFTase activity by the pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine antifolates was assayed in KB tumor cells. KB cells were treated with drug and [14C]glycine for 16 h, then [14C]formyl GAR was extracted and isolated by anion-exchange chromatography for quantitation. Relative [14C]formy GAR was expressed as percent of the untreated control as a function of drug concentrations. IC50s were as follows: 2.64+/−0.24 nM, 4; 2.11+/−0.37 nM, 5; 5.58+/−0.40 nM, 6; 4.95+/−0.44 nM, 7; 6.62+/−1.63 nM, 8; and 5.25+/−0.60 nM, 9. For comparison, the IC50 for GARFTase inhibitions in KB cells by compound 1, PMX and LMTX were 1.92 (+/−0.40) nM (not shown), 30 nM47 and 14 nM,47 respectively. The methods are described in the Experimental Section. Abbreviation: Cpd, compound.

We used an in vitro spectrophotometric enzyme assay with recombinant formyltransferase domain of human GARFTase to measure inhibition by monoglutamyl 6-pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine antifolates, 1, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, and 9, along with 3 and PMX from our previous study.18 Absorbance was measured at 295 nm accompanying one-carbon transfer from 10-formyl-5,8-dideazafolic acid to GAR to form 5,8-dideazafolic acid and formyl GAR. Assays were performed in the presence and absence of the inhibitors, and the initial rates were plotted versus inhibitor concentrations and fit to a hyperbola (Figure 1S, Supporting Information) for calculating Ki values (Table 2). Nanomolar Ki values were calculated that varied over a ~3–4-fold range, with the most potent GARFTase inhibition by compounds 4, 6, and 8.

Table 2. Ki values for inhibition of human GARFTase by 6-pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine heteroatom analogs.

GARFTase activity was determined by measuring formation of 5,8-dideazafolate from 10-formyl-5,8-dideazafolic acid using a spectrophotometric assay (295 nm) in the presence of the indicated antifolate. Detailed methods are described in the Experimental Section. Results are shown as mean values +/− standard errors from three replicate assays. The results for compound 3 and PMX were previously reported.18 Abbreviation; Cpd, compound

| Antifolate | Ki (nM) |

|---|---|

| PMX | 1000 +/− 160 |

| Cpd 1 | 160 ± 17 |

| Cpd 3 | 68 +/− 11 |

| Cpd 4 | 59 ± 9 |

| Cpd 5 | 99 ± 15 |

| Cpd 6 | 62 ± 7 |

| Cpd 7 | 122 ± 14 |

| Cpd 8 | 61 ± 4 |

| Cpd 9 | 201 ± 36 |

Collectively, our results identify GARFTase, the first folate-dependent step in de novo purine biosynthesis, as the principal intracellular target for the heteroatom series. The data in Table 2 suggest that as the monoglutamate forms, heteroatom substitution with N (4) or O (8) affords an approximately 3-fold improvement in GARFTase inhibitory potency over C (1). In addition, N-acetyl substitution (6) maintains this inhibitory potency. The formyl (5) and trifluoroacetyl (7) N-substitutions decrease potency somewhat against isolated GARFTase. Further, all of the heteroatom analogs, 4–9, as well as the carbon analogs 1 and 3, are 5- to 17-fold better GARFTase inhibitors than PMX.

X-Ray crystal structure of 6-pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine heteroatom antifolates with FRα and human GARFTase

Since compound 4 is selectively transported via FRα over RFC, we determined the x-ray crystal structure of FRα bound to 4 using our published methods.45 We expressed human FRα in HEK293 cells and purified FRα by affinity and size-exclusion chromatography. To confirm functionality of the purified soluble FRα, we measured competition for binding to purified FRα by folic acid or 4 with [3H]folic acid. Compound 4 showed an IC50 only slightly higher than that of folic acid in this assay (not shown), consistent with the results of our FRα binding experiments in RT16 CHO cells (Figure 8). For structural determinations, FRα was deglycosylated, stripped of bound folate, then incubated overnight with a molar excess of 4. The complex was purified and used to set up crystallization screens. The FRα/compound 4 complex formed crystals that permitted the determination of its structure at a resolution of 3.6 Å.

Compound 4 assumes a position in the pocket very similar to that of folic acid (Figures 12A and 12B) with interactions with the same 12 key residues [Tyr82 (60), Asp103 (81), Tyr107 (85), Trp124 (102), Arg125 (103), Arg128 (106), His157 (135), Lys158 (136), Trp160 (138), Trp162 (140), Ser196 (174), and Tyr197 (175); again, numbering for FRα is that of the full-length gene product with mature protein numbering in parentheses]. When compound 4 was computationally docked into the FRα pocket (Figure 7C), the position of the docked 4 was very close (RMSD 0.37 Å) to that of 4 in the experimentally determined FRα/4 co-crystal (Figure 12).

Figure 12. Crystal structures of FRα/folic acid (Panel A) andFRα/compound 4 (Panel B).

Superimposition of the crystal structure of folic acid with FRα onto the crystal structure of 4 indicates that the truncated 5-membered pyrrolo ring of 4 is compensated via the 3-atom bridge, compared to the 2- atom bridge of folic acid. Thus, the overall dimensions of both folic acid and 4 are comparable, permitting all important interactions with FRα to remain unaltered. The heteroatom in the bridge does not play an important role in binding to FRα for folic acid or 4. Figure 2S (A, B) shows electron density maps for 4 in complex with FRα.

As 4 was shown to exhibit nanomolar to sub-nanomolar potencies at GARFTase in our in situ and in vitro assays, we also determined the structure of a ternary complex of human GARFTase, 4 and substrate GAR (Figure 13; Table 1S, Supporting Information) to further understand the molecular determinants of inhibitor binding. Based on computational modeling (Figure 6A), we hypothesized that 4 would bind in a mode similar to that of 3, with the only difference being in the positions of the glutamyl α- and γ-carboxylates. Indeed, the pyrrolo[2,3- d]pyrimidine portion of 4 makes the predicted polar contacts with backbone atoms from GARFTase residues Ile898, Leu899, Ala947, Glu948 and Val950, whereas the L-glutamate of 4 (via the α-carboxylate) is positioned to make a bidentate interaction with Arg897 (Figure 13A). The heteroatom position, N10 in 4, also makes the predicted intermolecular interaction with GARFTase, mediated by an ordered water molecule that is coordinated by residues Asn913, His915 and Asp951, and the terminal NH2 of GAR. Based on the crystal structure of the ternary complex of GARFTase with 4 and GAR, and our molecular modeling studies, we predict that other heteroatoms at the 10-position, as seen in 8 (O) and 9 (S) will form hydrogen bonds to the ordered water, as well. N10-substituted compounds, on the other hand (i.e., 5, 6 and 7), would likely displace the ordered water and perhaps GAR, as well, while making direct polar contacts with residues Asn913, His915 and Asp951.

Figure 13. Crystal structures of human GARFTase.

Panel A, crystal structure of 4 (orange); panel B, 318 (green) with GAR (pink) in the folate binding pocket of GARFTase. GARFTase is shown in ribbon except for interacting side chains and backbone atoms, which are represented as sticks. For clarity, an alternate side-chain conformation of Arg871 has been removed in panel B. Figure 2S (C,D) (Supporting Information) shows electron density maps for 4 with GARFTase.

We previously reported that the computationally docked structures of our potent targeted molecules had different conformational requirements for attachment to FRα and GARFTase (or AICARFTase).35, 51 Superimposition of the crystallographic bound structures of 4 in FRα and GARFTase also shows that diametrically opposite conformations of the side chain of 4 are required for FRα (up) and GARFTase (down) binding. Thus, flexibility in the side chain of 4 is required for attachment to FRα and GARFTase to afford targeted transport and selective tumor inhibition.

In vivo antitumor efficacy with 4 with IGROV1 cells

Based on the in vitro efficacies of 4 versus 3 toward KB human tumor cells, we extended this analysis to IGROV1 human ovarian tumor cells. IGROV1 cells express ~40% of FRα levels and exhibit ~30% of PCFT activity of KB cells.18 We initially compared in vitro efficacies of 4 to 3 toward IGROV1 cells as a prelude to an in vivo efficacy trial with IGROV1 xenografts (Figure 14, panel A). Compound 3 was selected for comparison, reflecting its highly potent activity toward a broad spectrum of tumors including IGROV1.31 Results are also shown for compound 1 with a benzylic CH2 at position 10. With 3, an IC50 of 0.95 [+/−0.35 (SE)] nM was measured that shifted to 213 (+/−8) nM in the presence of 200 nM folic acid18, likely in part due to a non-mediated uptake component and to PCFT. Compound 4 was somewhat less potent (likely reflecting decreased non-mediated and PCFT-mediated uptake), with an IC50 of 2.70 (+/−1.15) nM, and protection by folic acid was substantially increased (IC50=872 +/− 106 nM). Similar results were seen with compound 1 toward IGROV1 cells (IC50 of 4.1 (+/−1.7) nM), although the inhibition was further reversed (IC50 >1000 nM) in the presence of excess folic acid.

Figure 14. In vitro and in vivo efficacies of compounds 4 and 3 toward the IGROV1 ovarian tumor.

Upper panel: Representative growth inhibition experiments for IGROV1 tumor cells treated with a range of concentrations of 3 or 4 in the absence (solid symbols and unbroken lines) or the presence (open symbols and broken lines) of 200 nM folic acid are shown. Results for compound 1 are included for comparison. The methods are described in the Experimental Section. Lower panel: Female NCR SCID mice (11 weeks old; 20 g average body weight) were maintained on a folate-deficient diet ad libitum for 14 days, prior to bilateral subcutaneous tumor engraftment. The mice were non-selectively randomized into 5 mice/group, then compounds 3 (28 mg/kg/inj; Q3dx5) or 4 (96 or 150 mg/kg/inj; Q3dx4) [dissolved in 5% ethanol (v/v), 1% Tween-80 (v/v), 0.5% NaHCO3 and deionized H2O; pH 6.5] were administered beginning on day 2. Mice were weighed daily and tumor measurements were recorded twice per week. Results are shown as mean values +/− standard errors. Abbreviation: cpd, compound; Rx, treatment.

For the in vivo drug efficacy trial, female NCR severe-combined immunodeficient (SCID) mice implanted bilaterally with subcutaneous IGROV1 ovarian tumors. Mice were provided a folate-deficient diet ad libitum to reduce serum folate concentrations to levels similar to those reported in humans.52 A parallel control cohort included mice fed standard (folate-replete) chow. For the trial, both the control and low-folate groups were implanted subcutaneously with IGROV1 tumor fragments. Compound 3 (Q3dx5; 28 mg/kg/inj) or compound 4 (Q3dx4; 96 and 150 mg/kg/inj) was administered intravenously beginning on day 2 post-implantation. The highest doses of 3 and 4 administered approximated the maximally tolerated doses for these compounds. The tumors were measured (twice weekly) and the overall health and body weights of the mice were recorded daily.

For the mice maintained on the folate-deficient diet, 3 (140 mg/kg total dose) was efficacious, with a 35% T/C on day 20, T-C of 9 days, and 1.4 log10 kill, as previously described.31 Compound 4 was tested at two dose levels. The highest non-toxic total dose of 600 mg/kg produced significant antitumor activity (12% T/C; T-C=15 days; 2.3 log10 kill), whereas the lower dose (384 mg/kg total dose) showed an efficacy similar to compound 3 (29% T/C; T-C=9 days, 1.4 log10 kill). These results demonstrate not only a dose-response but an efficacious depth-of-activity (favorable therapeutic index) for compound 4. For all treatments, the regimens were well tolerated, and the only dose-limiting symptom (weight loss) was completely reversible. Body weight loss (nadir of 15% for compound 3 and 17.0–17.3% for compound 4) occurred while the mice were undergoing treatment. However, following treatment, full weight recovery occurred within 48 hours. For the matched control group maintained on a standard diet, antitumor activity was ablated; i.e., compound 3 (140 mg/kg total dose) and compound 4 (600 mg/kg total dose) produced T/C values of 68% and 94% respectively. No weight loss or other adverse symptoms were observed.

The results from the in vivo efficacy trial with FRα- and PCFT-expressing IGROV1 human ovarian tumors substantiate our in vitro drug efficacy results and demonstrate that at equitoxic dose levels, 4 is more efficacious than 3, albeit with a higher dose requirement. Compound 4 showed a good depth-of-activity and there were no acute or long term toxicities other than completely reversible weight loss.

Conclusions

This study describes an in-depth analysis of the structure-activity determinants of 6-substituted pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine benzoyl antifolates as tumor-targeted therapeutics. The focus is on structural determinants involving heteroatom replacements of the carbon vicinal to the side chain phenyl ring in compound 1 by S, O, or N, and for the N-replacement, the impact of N-formyl, N-acetyl, or N-trifluoroacetyl moieties on cell proliferation and anti-tumor efficacy. The emphasis is on determinants of transport specificity by FRα and FRβ, and by PCFT, over RFC, and on inhibition of de novo purine nucleotide biosynthesis at GARFTase, the first folate-dependent step in this pathway.

Our results document several salient findings including (i) dramatically increased in vitro anti-proliferative activity resulting from heteroatom bridge substitutions toward CHO cell lines engineered to express human FRα or FRβ and FRα-expressing human tumor cells, over the corresponding C analog 1. (ii) For the N-heteroatom unsubstituted and substituted forms (compounds 4–7), in vitro drug efficacies were significantly greater toward FRβ-expressing CHO cells than toward CHO cells expressing a comparable amount of FRα. This likely reflects differences in rates of FR-mediated internalization and/or dissociation of bound ligands for FRβ versus FRα, as FR-targeted activities for these analogs were only modestly reflected in relative binding affinities to FRα and FRβ. FRα binding of 4 was confirmed by x-ray crystallography which validated the molecular modeling predictions for this series. Compared to compound 1, PCFT targeting was reduced by the heteroatom insertions, as reflected in decreased growth inhibition and decreased competition for [3H]MTX uptake with human PCFT-expressing R2/PCFT4 CHO cells.

We established de novo purine nucleotide biosynthesis as the targeted pathway and GARFTase as the enzyme target for the heteroatom-substituted antifolates, as measured by nucleoside/AICA protection from growth inhibition, and by in situ metabolic assays with [14C]glycine. Inhibition of cellular GARFTase in KB cells occurred at concentrations similar to those that inhibit cell proliferation. Results of the metabolic assays were corroborated by in vitro assays with purified GARFTase that showed greater enzyme inhibition by analogs with N (4, 5, 6, and 7) and O (8) insertions than that with a C-10 (1). For compound 4, a crystal structure was determined with GARFTase, providing further validation of this enzyme target and demonstrating clear contacts with the N10 heteroatom analogous to that in 10-CHOTHF. The disparity in drug concentrations for in vitro enzyme inhibition versus GARFTase inhibition in the cell-based metabolic assay likely reflects the importance of membrane transport and polyglutamate synthesis, as determinants of drug efficacy in intact cells. The potent in vitro inhibition of GARFTase by compounds 3, 4, 6 and 8 in their monoglutamate forms suggests that these antifolates would be effective against tumor cells resistant to PMX and other clinically used antifolates due to loss of polyglutamate synthesis, reflecting down regulation and/or deficiency of folylpolyglutamate synthetase.53

We extended our studies with engineered CHO and KB human tumor cells to IGROV1 human tumor cells, a model of serous ovarian cancer with significantly lower levels of FRα and PCFT.18 In a head-to-head comparison with 3, a thieonyl 6-substituted pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine and among the most potent FR- and PCFT-targeted agents we have identified,31 4 was more efficacious at an equitoxic dose, albeit with a higher dose requirement.

In conclusion, we established that heteroatom substitutions, including S, O and N, in the bridge region of 6-substituted 3-atom bridge pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine analogs related to 1 and 3 exert pronounced effects on the activity of this series, associated with increased targeting via FRs. Compared to clinically used antifolates such as PMX, analogs 4–9 are selectively transported into tumor cells, resulting in potent inhibition of GARFTase and cell proliferation, and would be expected to possess significantly lower toxicity toward normal tissues. In an in vivo study with IGROV1 human tumor cells, compound 4 was significantly more efficacious than 3, the most efficacious analog we have reported previously. Reflecting these characteristics, these novel tumor-targeted antifolates warrant further evaluation as anticancer agents.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

A rotary evaporator was used to carry out evaporation in vacuo. Final compounds and intermediates were dried in a CHEM-DRY drying apparatus over P2O5 at 80 °C. A MEL-TEMP II melting point with a FLUKE 51 K/J electronic thermometer apparatus was used and uncorrected to record melting points. A Bruker WH-400 (400 MHz) spectrometer or a Bruker WH-500 (500 MHz) spectrometer was used to record proton nuclear magnetic resonance spectra (1H NMR). Tetramethylsilane was used as an internal standard to express the chemical shift in ppm (parts per million): s, singlet; d, doublet; t, triplet; q, quartet; quin, quintet m, multiplet; and bs, broad singlet. Chemical names follow IUPAC nomenclature. Whatman Sil G/UV254 silica gel plates with a fluorescent indicator were used for performing thin-layer chromatography (TLC), and the spots were visualized under 254 nm and 365 nm illumination. All analytical samples were homogeneous on TLC in three different solvent systems. Solvents used for TLC were measured in volume. Columns of silica gel (230–400 mesh) (Fisher, Somerville, NJ) were used for chromatography. In spite of 24–48 h of drying in vacuo, fractional moles of water found in the analytical samples of antifolates could not be prevented and were confirmed by their presence in the 1H NMR spectra. Chemicals and solvents were purchased from Aldrich Chemical Co. or Fisher Scientific Co. and were used as received. Elemental analysis (C, H, N, F, S) was performed by Atlantic Microlab, Inc. (Norcross, GA). Element compositions were within 0.4% of the calculated values and confirmed >95% purity for all the compounds submitted for biological evaluation (Supporting Information is in Table 1S)

(4-{[2-(2-Amino-4-oxo-4,7-dihydro-3H-pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidin-6-yl)ethyl]amino}benzoyl)-L-glutamic acid (4)

To a 100 mL rbf compound 15 (100 mg, 0.32 mmol), N-methylmorpholine (0.64 mmol), 2-chloro-4,6-dimethoxy-1,3,5-triazine (0.64 mmol) and anhydrous DMF (7 mL) were added. The resulting mixture was stirred at room temperature under anhydrous condition for 1.5 hours. N-mehtylmorpholine (0.64 mmol) and L-glutamate di-tert-butyl hydrochloride (0.47 mmol) were added in reaction mixture. The resulting mixture was then stirred at room temperature under anhydrous condition for 12 hours. After evaporation of solvent under reduced pressure, MeOH (20 mL) was added followed by silica gel (1 gm). The resulting plug was loaded on to a silica gel column (3.5 cm × 2 cm) and eluted with CHCl3 followed by 3% MeOH in CHCl3. Fractions with Rf = 0.45 (MeOH/CHCl3 5:1) were pooled and evaporated to afford 16 (106 mg, 0.19 mmol, yield 60%) as solid. Compound 16 (106 mg, 0.19 mmol) was dissolved in dichloromethane (10 mL) and trifluoroacetic acid (2 mL) was added. The mixture was stirred at room temperature for 2 hours. TLC showed the disappearance of the starting material (Rf = 0.45) and one major spot at the origin (MeOH/CHCl3 5:1). The solvent was remove under reduced pressure and the residue was dissolved in 1 N NaOH. The suspension was filtered and filtrate was acidified to pH 4 with 1 N HCl. The resulting suspension was frozen in dry iceacetone bath, thawed to 4–5 °C in the refrigerator, and filtered. The residue was washed with a small amount of cold water and dried in vacuum using P2O5 to afford the target compound 4 (63 mg, yield 74%) as yellow powder; m.p. 163 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 1.93–2.07 (m, 2H, β-CH2), 2.32–2.33 (m, 2H, γ-CH2), 2.74–2.77 (t, 1H, CH2CH2NH, J = 6.0 Hz), 3.29–3.32 (t, 2H, CH2CH2NH, J = 6.0 Hz), 4.32–4.38 (m, 1H, α-CH), 5.99 (d, 1H, C5-CH, J = 2.0 Hz), 6.03 (d, 2H, 2-NH2, exch.), 6.27 (s, 1H, CH2CH2NHAr, exch.), 6.60–6.62 (d, 2H, Ar-CH, J = 8 Hz), 7.66–7.68 (d, 2H, Ar-CH, J = 8 Hz), 8.13–8.15 (d, 1H, Ar-CONH, J = 8 Hz, exch.), 10.18 (bs, H, 3-NH, exch.), 10.93 (s, H, 7-NH, exch.). Anal. Calcd for (C20H22N6O6·1.75 H2O) C, H, N.

(4-{N-[2-(2-amino-4-oxo-4,7-dihydro-3H-pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidin-6- yl)ethyl]formamido}benzoyl)-L-glutamic acid (5)

To a solution of 4 (110 mg, 0.25 mmol) in 97% formic acid (5 mL) was added acetic anhydride (0.07 mL, 15.75 mmol), and the reaction mixture was stirred at 25 °C for 3 hours. The solvent was removed under reduced pressure and the residue dissolved in 1 N NaOH at 0 °C. The filtrate was acidified to pH 4 with 0.5 N HCI and stored at 0 °C for 2 hours. The yellow solid was collected by filtration and dried over P2O5 to give 40 mg (35%) of 5; m.p. 163 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 1.95–2.13 (m, 2H, β-CH2), 2.34–2.37 (t, 2H, γ-CH2, J = 7.2 Hz), 2.68–2.72 (t, 2H, CH2CH2NCOH, J = 7.2 Hz), 4.06–4.09 (t, 2H, CH2CH2NCOH, J = 7.2 Hz), 4.38–4.44 (m, 1H, α-CH), 5.91 (s, 1 H, C5-CH), 6.08 (bs, 2H, 2-NH2, exch.), 7.41–7.43 (d, 2H, Ar-CH, J = 8.4 Hz), 7.93–7.95 (d, 2H, Ar-CH, J = 8.4 Hz), 8.57 (s, CH2CH2NCOH, 1H), 8.64–8.66 (d, 1H, Ar-CONH, J = 7.6 Hz), 10.23 (bs, H, 3-NH, exch.), 10.93 (s, H, 7-NH, exch.). Anal. Calcd for (C21H22N6O7·2H2O·0.4CF3COOH) C, H, N.

(4-{N-[2-(2-amino-4-oxo-4,7-dihydro-3H-pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidin-6- yl)ethyl]acetamido}benzoyl)-L-glutamic acid (6)

4 (110 mg, 0.25 mmol) was added in 5 mL acetic anhydride, and the reaction mixture was stirred under anhydrous condition at 25 °C for 3 hours. The excess of acetic anhydride was removed under reduced pressure. The residue was suspended in cold water and basified using 1N NaOH. The suspension was then filtered and acidified to pH 4 with 0.5 N HCI and stored at 0 °C for 2 hours. The white solid was collected by filtration and dried over P2O5 to give 57 mg (47%) of 6; m.p. 163 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 1.93– 2.14 (m, 5H, β-CH2 & CH2CH2NCOCH3), 2.35–2.39 (m, 2H, γ-CH2), 2.64–2.67 (t, 2H, CH2CH2NCOCH3, J = 8 Hz), 3.89–3.92 (t, 2H, CH2CH2NCOCH3, J = 8 Hz), 4.38–4.44 (m, 1H, α- CH), 5.91 (s, 1 H, ArH), 5.99 (s, 2H, 2-NH2, exch.), 7.34–7.36 (d, 2H, Ar-CH, J = 8 Hz), 7.93– 7.95 (d, 2H, Ar-CH, J = 8 Hz), 8.68–8.70 (d, 1H, Ar-CONH, J = 8 Hz, exch.), 10.16 (bs, H, 3-NH, exch.), 10.83 (s, H, 7-NH, exch.). Anal. Calcd for (C22H24N6O7·2H2O) C, H, N.

(4-{N-[2-(2-amino-4-oxo-4,7-dihydro-3H-pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidin-6-yl)ethyl]-2,2,2- trifluoroacetamido}benzoyl)-L-glutamic acid (7)

5 mL trifluoroacetic anhydride was add to a solution of 4 (110 mg, 0.25 mmol) in 10 mL dichloromethane, and the reaction mixture was stirred at 25 °C for 3 hours. The solvent was removed under reduced pressure and the residue was suspended in water. 1N NaOH was added dropwise to the suspension and pH was adjusted to 4. The suspension was stored at 0 °C for 2 hours. The yellow solid was collected by filtration and dried over P2O5 to give 83 mg (76%) of 7; m.p. 163 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 1.96– 2.12 (m, 2H, β-CH2), 2.36–2.39 (t, 2H, γ-CH2, J = 7.2 Hz), 2.73–2.77 (t, 2H, CH2CH2NCOCF3, J = 7.6 Hz), 3.95–3.99 (t, 2H, CH2CH2NCOCF3, J = 7.6 Hz), 4.38–4.44 (m, 1H, α-CH), 6.00 (s, 1 H, C5-CH), 6.10 (bs, 2H, 2-NH2, exch.), 7.40–7.42 (d, 2 H, Ar-CH, J = 8 Hz), 7.94–7.96 (d, 2H, Ar- CH, J = 8 Hz), 8.77–8.79 (d, 1H, Ar-CONH, J = 7.4 Hz, exch.), 10.25 (bs, H, 3-NH, exch.), 10.91 (s, H, 7-NH, exch.), 12.33 (bs, 2H, 2COOH, exch.). Anal. Calcd for (C22H21N6O7F3·1H2O·0.06CF3COOH) C, H, N, F.

{4-[2-(2-amino-4-oxo-4,7-dihydro-3H-pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidin-6-yl)ethoxy]benzoyl}-L-glutamic acid (8)

To a 250 mL rbf, was added a mixture of 22 (100 mg, 0.32 mmol), Nmethylmorpholine (0.64 mmol), 2-chloro-4,6-dimethoxy-1,3,5-triazine (0.64 mmol) and anhydrous DMF (7 mL). After 1.5 hour N-mehtylmorpholine (0.64 mmol) and L-glutamic acid dimethylester hydrochloride (0.5 mmol). The reaction mixture was then stirred at room temperature for 12 hours. After evaporation of solvent under reduced pressure, MeOH (20 mL) was added followed by silica gel (1 gm). The resulting plug was loaded on to a silica gel column (3.5 × 2 cm2) and eluted with CHCl3 followed by 3 % MeOH in CHCl3. Fractions with Rf = 0.42 (CHCl3/CH3OH, 5:1) were pooled and evaporated to afford 23 (63 mg, yield 42%). Compound 20 (0.13 mmol) was dissolved in MeOH (10 mL) added 1N NaOH (10 mL) and the mixture was stirred under anhydrous condition at room temperature for 10 h. TLC showed the disappearance of the starting material (Rf = 0.42) and one major spot at the origin (MeOH/CHCl3 5:1). The reaction mixture was dissolved in water (10 mL), the resulting solution was cooled in an ice bath, and the pH was adjusted to 3–4 with dropwise addition of 1N HCl. The resulting suspension was frozen in dry ice-acetone bath, thawed to 4–5 °C in the refrigerator, and filtered. The residue was washed with a small amount of cold water and dried in vacuum using P2O5 to afford the target compound 8 (8) (55 mg, 0.12 mmol) as white powder; m.p. 162 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 1.95–2.11 (m, 2H, β-CH2), 2.34–2.37 (t, 2H, γ-CH2, J = 6.0 Hz), 2.97–3.00 (t, 2H, CH2CH2O, J = 6.0 Hz), 4.24–4.27 (t, 2H, CH2CH2O, J = 6.0 Hz), 4.36–4.41 (m, H, α-CH), 6.00 (s, H, C5-CH), 6.01 (bs, 2H, 2-NH2, exch.), 7.03–7.05 (d, 2H, Ar-CH, J = 8.0 Hz), 7.86–7.88 (d, 2H, Ar-CH, J = 8.0 Hz), 8.45–8.47 (d, 1H, Ar-CONH, J = 8.0 Hz), 10.23 (s, H, 3-NH, exch.), 10.97 (s, H, 7-NH, exch.), 12.39 (bs, 2H, 2COOH, exch.). Anal. Calcd for (C20H21N5O7·2 H2O) C, H, N.

(4-{[2-(2-amino-4-oxo-4,7-dihydro-3H-pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidin-6-yl)ethyl]thio}benzoyl)-L-glutamic acid (9)

To a solution of the 3 (309 mg, 0.6 mmol) in MeOH (10 mL) was added 1N NaOH (10 mL) and the mixture was stirred at room temperature for 10 h. The reaction mixture was evaporated to dryness under reduced pressure. The residue was dissolved in distilled water (5 mL), and the pH was adjusted to 3–4 by dropwise addition of 1N HCl. The precipitate was filtered, washed with water and dried under vacuum with P2O5 to afford 260 mg (95%) of 9 as a light yellow powder. mp 184–185 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 1.92–2.12 (m, 2H, β-CH2), 2.34– 2.37 (t, 2H, γ-CH2, J = 7.5 Hz), 2.82–2.85 (t, 2H, CH2CH2S, J = 7.5 Hz,), 3.29–3.32 (t, CH2CH2S J = 7.5 Hz, 2H, CH2), 4.37–4.42 (m, 1H, α-CH), 6.00 (s, 1H, C5-CH), 6.02 (s, 2H, 2-NH2, exch), 7.41–7.43 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, Ar-CH), 7.83–7.85 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, Ar-CH), 8.56–8.58 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H, Ar-CONH, exch), 10.17 (s, 1H, 3-NH, exch), 10.91 (s, 1H, 7-NH, exch), 12.46 (bs, 2H, COOH, exch). Anal. Calcd for (C20H21N5O6S·1.0 H2O) C, H, N, S.

Ethyl 4-[(3-oxobutyl)amino]benzoate (12)

To a vigorously stirred solution of compound 11 (5 gm, 30 mmol) in anhydrous absolute ethanol (10 mL), methyl vinyl ketone 10 (2.5 mL) was added. The reaction mixture was heated under reflux for 4.5 hours and resultant mixture was cooled to 0 °C. The precipitated crystalline product was collected and washed with precooled ethanol and dried to afford 12 (4.2 gm, yield 59%) as white powder; m.p. 98 °C; Rf 0.57 (1:1 hexane:EtOAc); 1H NMR (CHCl3) δ 1.36–1.39 (t, 3H, OCH2CH3, J = 7.2 Hz), 2.19 (s, 3H, CH2COCH3), 2.79–2.82 (t, 2H, CH2CH2O, J = 6.0 Hz), 3.48–3.51 (t, 2H, CH2CH2O, J = 6.0 Hz), 4.31–4.36 (q, 2H, OCH2CH3, J = 7.2 Hz), 5.54 (bs, Ar-NH, exch.), 6.61–6.64 (d, 2H, Ar-CH, J = 8.4 Hz), 7.88–7.91 (d, 2H, Ar-CH, J = 8.4 Hz).

Ethyl 4-[(4-bromo-3-oxobutyl)amino]benzoate (13)

A suspension of 12 (3 gm, 12.77 mmol) in 8 mL of 33% hydrogen bromide-glacial acetic acid solution was treated with 1 mL of bromine in 2 mL of glacial acetic acid and stirred for 2.5 hours at 25 °C. Ether (100 mL) was added to the reaction mixture with swirling until separation of the syrupy hydrobromide was complete. The ether was decanted, and any ether remaining was evaporated from the syrup along with excess hydrogen bromide. After further drying by evaporation (bath 35 °C) of a solution in an equal volume of dichloromethane, the syrup weighed 3.3 gm. The syrup was then stirred with cold water and filtered to afford yellow solid. Yellow solid obtained was then washed with water (3 × 20 mL) and dissolved in dichloromethane. The solution was dried over sodium sulfate. Removal of solvent under reduced pressure at room temperature gave a beige colored semisolid. The crude product was thoroughly triturated with pre-cooled ether and the solid product was collected by filtration to afford 13 (1.75 gm, yield 33%); m.p. 142 °C; Rf 0.81 (1:1 hexane:EtOAc); 1H NMR (CHCl3) δ 1.37–1.41 (t, 3H, OCH2CH3, J = 7.2 Hz), 2.79–2.82 (t, 2H, CH2CH2O, J = 6.0 Hz), 3.48–3.51 (t, 2H, CH2CH2O, J = 6.0 Hz), 3.91 (s, 2H, CH2COCH2Br), 4.33–4.38 (q, 2H, OCH2CH3, J = 7.2 Hz), 6.82–6.84 (d, 2H, Ar-CH, J = 8.4 Hz ), 7.94–7.96 (d, 2H, Ar-CH, J = 8.4 Hz).

4-{[2-(2-Amino-4-oxo-4,7-dihydro-3H-pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidin-6-yl)ethyl]amino}benzoic acid (15)

A suspension of α-bromoketone 13 (11.89 gm, 38 mmol) in trifluoroacetic anhydride (100 mL) was stirred under anhydrous condition at room temperature to give a clear solution within 30 minutes. The stirring continued for an additional 2 hours and the solution was allowed to stand at room temperature overnight. After removal of excess trifluoroacetic anhydride under reduced pressure at 40–45 °C, the brownish oily residue was dissolved in dichloromethane (150 mL). The solution was washed with cold 2% HCI (100 mL), cold 5% NaHCO3 (100 mL), and finally with cold water (2 × 100 mL). The organic layer was then treated with a mixture of Florisil-charcoal- sodium sulfate (59 gm: 2.4 gm: 20 gm) and stirred for 0.5 hour at room temperature. The mixture was filtered and excess of solvent was evaporated under reduced pressure at 25– 30 °C to afford amine protected α-bromoketone (11.31 gm, yield 76%). Amine protected α- bromoketone (3.84 gm, 9.4 mmol) was then added to a suspension of 2,6-diaminopyrimidin-4- one (1.26 gm, 10 mmol) in anhydrous dimethylformamide (25 mL). The resulting mixture was stirred under anhydrous condition at room temperature for 3 days. After evaporation of solvent under reduced pressure, Methanol (20 mL) was added followed by silica gel (5 gm). The resulting plug was loaded on to a silica gel column (3.5 cm × 12 cm) and eluted with CHCl3 followed by 3% MeOH in CHCl3 and then 5% MeOH in CHCl3. Fractions with and Rf = 0.58 (TLC) (CHCl3/CH3OH, 5:1) were pooled and evaporated to afford 14 (1.03 gm, 2.36 mmol, yield; 25%). Compound 14 (306 mg, 0.7 mmol) was dissolved in MeOH (10 mL) and 1N NaOH (10 mL) was added. The mixture was stirred under anhydrous condition at room temperature for 10 hours. TLC showed disappearance of the starting material (Rf = 0.45) and one major spot at the origin (MeOH/CHCl3 5:1). The reaction mixture was dissolved in water (10 mL), the resulting solution was cooled in an ice bath, and the pH was adjusted to 3–4 with drop wise addition of 1N HCl. The resulting suspension was frozen in dry ice-acetone bath, thawed to 4–5 °C in the refrigerator, and filtered. The residue was washed with a small amount of cold water and dried in vacuum using P2O5 to afford compound 15 (157 mg, yield 88%) as yellow powder.

Compound 14; m.p. 157 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 1.25–1.29 (t, 3H, OCH2CH3, J = 7.2 Hz), 2.75– 2.78 (t, 2H, CH2CH2NCOCF3, J = 6.0 Hz), 3.31–3.35 (t, 2H, CH2CH2NCOCF3, J = 6.0 Hz), 4.18– 4.23 (q, 2H, OCH2CH3, J = 7.2 Hz), 6.00 (s, 1H, C5-CH), 6.01 (bs, 2H, 2-NH2), 6.62–6.64 (d, 2H, Ar-CH, J = 8 Hz), 7.68–7.70 (d, 2H, Ar-CH, J = 8 Hz), 10.25 (s, H, 3-NH), 10.97 (s, H, 7-NH).

Compound 15; m.p. 177 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 2.74–2.77 (t, 1H, CH2CH2NH, J = 6.0 Hz), 3.29–3.32 (t, 2H, CH2CH2NH, J = 6.0 Hz), 5.98 (s, 1H, C5-CH), 6.11 (bs, 2H, 2-NH2, exch.), 6.54 (t, 1H, CH2CH2NH, exch.), 6.60–6.62 (d, 2H, Ar-CH, J = 8 Hz), 7.65–7.68 (d, 2H, Ar-CH, J = 8 Hz), 10.25 (s, H, 3-NH, exch.), 10.94 (s, H, 7-NH, exch.). Anal. Calcd for (C15H15N5O3· 0.2CHCl3·2.5CH3COOH) C, H, N.

3-[4-(ethoxycarbonyl)phenoxy]propanoic acid (19)

To 100 mL of distilled water in an Erlenmeyer flask was added 4.15 gm (25 mmol) of 18 and the mixture was slowly heated to 80 °C under stirring with the dropwise addition of 25 mL of 1 N NaOH. The clear solution thus obtained was treated with 2 mL of β-propiolactone 17, and the mixture was allowed to stir at this temperature for 0.5 hours. The solution was then cooled to room temperature and acidified with 6N HCl to pH 3. The precipitated material was extracted with three 25 mL portions of ether, and the ether extract was washed twice with distilled water and extracted several times with 20 mL portions of saturated sodium bicarbonate until all the effervescence ceased on further addition of NaHCO3. The bicarbonate extracts were combined and acidified to pH 3 with 6 N HCl. The white precipitate thus obtained was washed with water and dried to afford compound 19 (3.18 gm, 52%); m.p. 146–147 °C; Rf 0.51 (Hexane/EtOAc 1:1); 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 2.89–2.92 (t, 2 H, CH2CH2O, J = 6.0 Hz), 3.91 (s, 3H, OCH3), 4.31–4.34 (t, 2 H, CH2CH2O, J = 6.0 Hz), 6.94–6.95 (d, 2 H, Ar-CH, J = 7.5 Hz), 8.00–8.02 (d, 2 H, Ar-CH, J = 7.5 Hz).

4-[2-(2-amino-4-oxo-4,7-dihydro-3H-pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidin-6-yl)ethoxy]benzoic acid (22)

To 19 (2.24 gm,10 mmol) in a 250 mL flask was added oxalyl chloride (7.61 gm, 60 mmol) and anhydrous CH2Cl2 (20 mL). The resulting solution was refluxed for 1 hour and then cooled to room temperature. After the solvent was evaporated under reduced pressure, the residue was dissolved in 20 mL of Et2O. The resulting solution was added dropwise to an ice cooled diazomethane (generated in situ from 15 gm of diazald by using Aldrich Mini Diazald apparatus) in an ice bath over 10 min. The resulting mixture was allowed to stand for 30 min and then stirred for an additional 1 hour. To this solution was added 48% HBr (20 mL). The resulting mixture was refluxed for 1.5 hours. After the mixture was cooled to room temperature, the organic layer was separated, and the aqueous layer was extracted with Et2O (2 × 200 mL). The combined organic layer and Et2O extract was washed with two portions of 10% Na2CO3 solution and dried over Na2SO4. Evaporation of the solvent afforded 20 (2.82 gm, 9.4 mmol) in 94% yield. To a suspension of 2,6-diaminopyrimidin-4-one (1.26 gm, 10 mmol) in anhydrous DMF (25 mL) were added 20 (2.82 gm, 9.4 mmol). The resulting mixture was stirred under N2 at room temperature for 3 days. After evaporation of solvent under reduced pressure, MeOH (20 mL) was added followed by silica gel (5 gm). The resulting plug was loaded on to a silica gel column (3.5 cm × 12 cm) and eluted with CHCl3 followed by 3% MeOH in CHCl3 and then 5% MeOH in CHCl3 (CHCl3/CH3OH, 5:1). Fractions with Rf 0.58 (TLC) were pooled and evaporated to afford 21 (956 gm, yield 31%) as white powder. Compound 21 (0.7 mmol) was dissolved in MeOH (10 mL) added 1N NaOH (10 mL) and the mixture was stirred under anhydrous condition at room temperature for 10 hours. TLC showed the disappearance of the starting material (Rf = 0.58) and one major spot at the origin (MeOH/CHCl3 5:1). The reaction mixture was dissolved in water (10 mL), the resulting solution was cooled in an ice bath, and the pH was adjusted to 3–4 with dropwise addition of 1N HCl. The resulting suspension was frozen in dry ice-acetone bath, thawed to 4–5 °C in the refrigerator, and filtered. The residue was washed with a small amount of cold water and dried in vacuum using P2O5 to afford the target 22 (677 mg, yield 74%) as white powder; m.p.; 159 °C, 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 2.97–2.99 (t, 2H, CH2CH2O, J = 6.0 Hz), 4.25–4.28 (t, 2H, CH2CH2O, J = 6.0 Hz), 6.01 (s, H, C5-CH), 6.26 (bs, 2H, 2-NH2, exch.), 7.04– 7.06 (d, 2H, Ar-CH, J = 8.0 Hz), 7.88–7.90 (d, 2H, Ar-CH, J = 8.0 Hz), 10.35 (s, H, 3-NH, exch.), 11.04 (s, H, 7-NH, exch.). Anal. Calcd for (C15H14N4O4·0.75 H2O) C, H, N.

Ethyl 2-(2-amino-4-oxo-4,7-dihydro-3H-pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidin-6-yl)acetate (27)

To a solution of 2,4-diamino-6-hydroxypyrimidine 25, (7.20 gm, 50 mmol) and s odium acetate (4.10 gm, 50 mmol) in water (150 mL) at reflux was added, dropwise, ethyl-4-chloroacetoacetate, 26 (7.41 mL, 55 mmol). Within an hour, a thick white precipitate appeared. The mixture was heated at reflux for 18 hours. The suspension was cooled to room temperature, filtered, washed with water (2 × 50 mL), acetone (2 × 50 mL) and dried to afford 7.31 gm (54%) of 27 as a buff-colored solid: m.p. >250 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO- d 6 ) δ 1.16–1.21 (t, 3H, OCH2CH3, J = 7.2 Hz), 3.57 (s, 2H, Ar -CH2), 4.04–4.11 (q, 2H, OCH2CH3, J = 7.2 Hz), 6.00 (s, 1H, C5-CH), 6.04(bs, 2H, 2-NH2, exch), 10.20 (bs, 1H, 3-NH, exch), 10.90 (bs, 1H, 7- NH, exch).

2-Amino-6-(2-hydroxyethyl)-3,7-dihydro-4H-pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidin-4-one (28)

To a suspension of the ester 27 (1.0 gm, 4.24 mmol) in anhydrous tetrahydrofuran (25 mL) at 0 °C was added a 1 M solution of lithium triethylborohydride (Super-Hydride) in tetrahydrofuran (33 mL, 33.92 mmol). The solution was stirred for 30 minutes, after which water (30 mL) was added carefully, followed by acidification of the mixture to pH 5.0 with 5 N hydrochloric acid. Tetrahydrofuran was evaporated under vacuum, and the white precipitate obtained was refrigerated overnight, filtered and dried under vacuum over phosphorous pentoxide to afford 0.615 gm (75%) of 28 as a white solid: m.p. >275 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO- d 6 ) δ 2.60–2.64 (t, 2H, CH2CH2OH, J = 6.0 Hz), 3.55–3.61 (q, 2H, CH2CH2OH, J = 6.0 Hz), 4.61–4.64 (bs, 1H, CH2CH2OH), 5.88 (s, 1H, C5-CH), 5.96 (bs, 2H, 2-NH2, exch), 10.12 (bs, 1H, 3-NH, exch), 10.76 (bs, 1H, 7-NH, exch).

2-(2-Amino-4-oxo-4,7-dihydro-3H-pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidin-6-yl)ethyl methanesulfonate (29)

To a solution of the alcohol 28 (0.25 gm, 1.29 mmol) in N,N-dimethylformamide (20 mL) at 0 °C was added triethylamine (0.27 mL, 1.93 mmol) and methanesulfonyl chloride (0.16 gm, 1.42 mmol) and the solution stirred under nitrogen for 2 hours. The reaction mixture was filtered and the filtrate was evaporated to dryness. The residue was suspended in acetone, silica gel (0.50 gm) was added to the suspension and the acetone evaporated to form a plug, which was loaded on top of a silica gel column (20 cm × 2 cm) and eluted using a 5:1 mixture of chloroform:methanol. Fractions containing the product (Rf = 0.41, chloroform:methanol, 3:1) were pooled and the solvent evaporated to afford 0.28 gm (80%) of 29 as a white solid: m.p. >250 °C (dec.); 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 2.89–2.93 (t, 2H, CH2CH2OSO2CH3, J = 6.0 Hz), 3.13 (s, 3H, CH2CH2OSO2CH3), 4.36–4.41 (t, 2H, CH2CH2OSO2CH3, J = 6.0 Hz), 6.01 (bs, 3H, 2-NH2 & CH), 10.17 (bs, 1H, 3-NH, exch), 10.91 (bs, 1H, 7-NH, exch).

Methyl 4-{[2-(2-amino-4-oxo-4,7-dihydro-3H-pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidin-6- yl)ethyl]thio}benzoate (30)

To a solution of 4-mercaptobenzoic acid methyl ester (907 mg, 5.4 mmol) in anhydrous DMF (20 mL) was added potassium carbonate (1.12 gm, 8.1 mmol), and the mixture was stirred at room temperature under nitrogen. After 1 h, methanesulfonic ester, 25, (730 mg, 2.7 mmol) was added all at once, and the resulting mixture was stirred for a further 6 h at room temperature. The solvent was evaporated under reduced pressure and the residue was dissolved in methanol. Silica gel (1 gm) was added, and the solvent was evaporated under reduced pressure. The resulting plug was loaded on the top of a silica gel column (2 cm × 15 cm) and eluted using a gradient of with 5–10% MeOH in CHCl3. Fractions that showed the desired product (TLC) were pooled and evaporated to dryness to afford 344 mg (37%) of 30 as a white powder. m.p. 179–180 °C; TLC Rf 0.58 (CHCl3/MeOH 5:1); 1H NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 2.84– 2.87 (t, 2H, CH2CH2S, J = 7.5 Hz), 3.31–3.34 (t, 2H, CH2CH2S, J = 7.5 Hz), 6.02 (s, 1H, C5-CH), 6.10 (s, 2H, 2-NH2, exch), 7.43–7.45 (d, Ar-CH, J = 8.5 Hz), 7.86–7.88 (d, Ar-CH, J = 8.5 Hz), 10.24 (s, 1H, 3-NH, exch), 10.96 (s, 1H, 7-NH, exch).

4-{[2-(2-Amino-4-oxo-4,7-dihydro-3H-pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidin-6-yl)ethyl]thio}benzoic acid (31)

To a solution of the 30 (344 mg, 1 mmol) in MeOH (10 mL) was added 1N NaOH (10 mL) and the mixture was stirred at 60 °C for 10 h. The reaction mixture was evaporated to dryness under reduced pressure. The residue was dissolved in distilled water (5 mL), and the pH was adjusted to 3–4 by dropwise addition of 1N HCl. The precipitate was filtered, washed with water and dried under vacuum with P2O5 to afford 330 mg (99%) of 31 as a light yellow powder. m.p. 189–190 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 2.84–2.87 (t, 2H, CH2CH2S, J = 7.5 Hz), 3.31–3.34 (t, 2H, CH2CH2S, J = 7.5 Hz), 6.04 (s, 1H, C5-CH), 6.25 (s, 2H, 2-NH2, exch), 7.41–7.42 (d, Ar-CH, J = 8.5 Hz,), 7.85–7.87 (d, Ar-CH, J = 8.5 Hz,), 10.39 (s, 1H, 3-NH, exch), 11.04 (s, 1H, 7-NH, exch), 12.79 (s, 1H, COOH, exch).

Diethyl (4-{[2-(2-amino-4-oxo-4,7-dihydro-3H-pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidin-6- yl)ethyl]thio}benzoyl)-L-glutamate (32)

To a solution of 31, (330 mg, 1 mmol) in anhydrous DMF (20 mL) was added N-methylmopholine (0.2 mL, 1.8 mmol) and 2-chloro-4,6-dimethoxy- 1,3,5-triazine (317 mg, 1.8 mmol). The resulting mixture was stirred at room temperature for 2 h. To this mixture was added N-methylmopholine (0.2 mL, 1.8 mmol) and L-glutamic acid diethyl ester hydrochloride (360 mg, 1.5 mmol). The reaction mixture was stirred for an additional 4 h at room temperature and then evaporated to dryness under reduced pressure. The residue was mixed with 1 g of silica gel to make a plug and chromatographed on a silica gel column (2 × 15 cm) with 10% MeOH in CHCl3 as the eluent. Fractions that showed the desired spot (TLC) were pooled and evaporated to dryness to afford 309 mg (60%) of 32 as a light yellow powder. m.p. 84–85 °C; TLC Rf 0.59 (CHCl3/MeOH 5:1); 1H NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 1.15–1.21 (m, 6H, OCH2CH3), 1.97–2.15 (m, 2H, β-CH2), 2.43–2.46 (t, 2H, γ-CH2, J = 7.5 Hz), 2.82–2.85 (t, 2H, CH2CH2S, J = 7.5 Hz), 3.29–3.33 (t, 2H, CH2CH2S, J = 7.5 Hz), 4.03–4.13 (m, 4H, 2OCH2CH3), 4.41–4.45 (m, 1H, C5-CH), 6.00 (s, 1H, C5-CH), 6.15 (s, 2H, 2-NH2, exch), 7.41–7.43 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, Ar-CH), 7.83–7.85 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, Ar-CH), 8.71–8.72 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H, CONH, exch), 10.29 (s, 1H, 3- NH, exch), 10.96 (s, 1H, 7-NH, exch).

Molecular Modeling and Computational Studies

The X-ray crystal structures of human FRα bound to folic acid (PDB: 4LRH, 2.80 Å)45 and human GARFTase bound to 3 (PDB: 4ZYW, 2.05 Å)18 were obtained from the protein database. Antifolate GARFTase docking studies were performed using LeadIT 2.1.6.54 Default settings were used to calculate the protonation state of the proteins and the ligands. Free rotation of water molecules in the ligand binding site (defined by amino acids within 6.5 Å from the crystal structure ligand) was permitted. Ligands for docking were sketched using MOE 2013.08,55 and energy was minimized using the MMF94X force field (limit of 0.05 kcal/mol). Molecules were docked using the triangle matching placement method and scored using default settings. The docked poses were visualized using CCP4MG.56